Michael Gallagher's Blog, page 10

May 1, 2014

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: W. T. Stead—the man who forsaw his own death?

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eleventh in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eleventh in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.William Thomas Stead was born in 1849, the son of a Congregationalist minister and a campaigning reformist mother. At the unlikely age of twenty-two he was appointed as editor of the Northern Echo, a regional newspaper based in Darlington in the north of England. Seizing an opportunity afforded by the excellent railroad connections on offer at the local train station, he managed to expand the Echo's distribution to national levels. In 1880 he took a post in London as the assistant editor of the Pall Mall Gazette. Two years later he became its editor, and was responsible for many of the innovations—from simple things such as the use of maps to help illustrate a story's location, through to a number of rather questionable investigative techniques—that paved the way for the tabloids of today. He is probably best remembered now for the Eliza Armstrong case, the darkest scandal to hit London in 1885.

On Monday the 6th of July 1885 he published the first of four installments of The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, a series of articles with sensationalist headings such as "The Violation of Virgins", "The Confessions of a Brothel-Keeper", "How Girls Were Bought and Ruined", and most notably "A Child of Thirteen Bought for £5", which told the story of "Lily", a thirteen-year-old virgin who was sold into prostitution by her alcoholic mother.

His purpose was simple. Together with colleagues from the Social Purity movement and the Salvation Army, Stead wanted the government to pass a bill raising the age of consent from thirteen, as it was then, to sixteen, as it is now. His aim was to stir up a public outcry that would force the reluctant government into doing this quickly. But the articles were so lurid that W. H. Smith & Sons, who had a monopoly on news stands, refused to distribute the paper, so volunteers from the Salvation Army took to the streets to sell it instead. Copies were in such high demand that fighting broke out in front of the Gazette's offices, and a trade sprang up in second-hand copies, which went for many times more than their original price.

The public's response was all that Stead could have wished for. Protest meeting were organized, thousands marched on Hyde Park, and in fewer than four weeks the bill was passed, but not before rival newspapers started unearthing the true facts about "Lily".

It turned out that Lily was in fact a girl called Eliza Armstrong and the reason Stead was aware of the case was because it was he and his colleagues who had instigated her purchase in the first place. They had engineered the whole scandal, acquiring Eliza through a reformed procuress (with the sole intention of proving that it could be done) and she was now living safely with their Salvation Army friends in France. She was reunited with her parents, who claimed that they thought she had been sold into domestic service, on August 24th.

Ordinary people and politicians alike were justifiably furious at having been manipulated in such a manner. Stead and his co-conspirators were brought to trial, and on the 10th of November he and two others were found guilty of abduction and procurement. Stead received three months imprisonment in Holloway and by all accounts was a model prisoner.

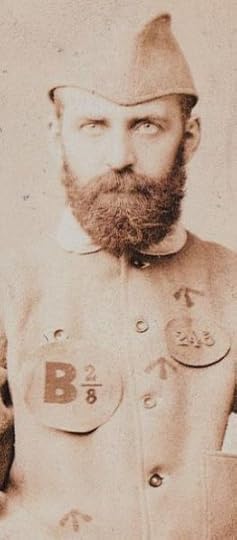

Taking his lead from Georgina Weldon (who for publicity purposes had done much the same thing), on his release Stead asked the prison governor if he could keep his prison uniform, and each year on November 10th he would put it on and wear it as a badge of honor to celebrate his great "victory".

According to Stead scholar Owen Mulpetre, Stead's interest in spiritualism was initially sparked by a colleague during his time at the Northern Echo, though he didn't attend a séance until his first year at the Gazette. It wasn't until after resigning from the paper in 1890 that he began experimenting with automatic writing (writing letters whilst in a trance state), claiming that in 1892 he'd achieved some success with a series of letters purporting to be from one Julia Ames, an American journalist of his acquaintance who had recently died. This was the beginning of an abiding and deeply-felt—though thoroughly commercial—interest in spiritualism. The following year he launched Borderland, a spiritualist quarterly magazine that ran for five years. In 1909 Stead set up the gloriously-conceived Julia's Bureau, an agency where the public could contact their loved ones through a group of resident mediums that assembled regularly each day.

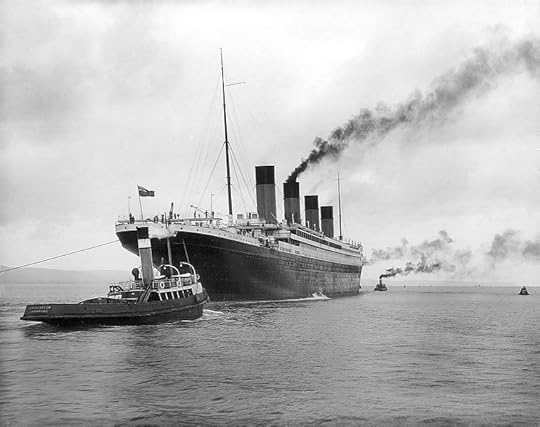

Stead often joked that he would die at the hands of a lynch-mob or by drowning. In 1892 he published a story entitled From the Old World to the New, in which the survivors from a ship that had collided with an iceberg are picked up mid-Atlantic by a conveniently passing vessel. Some people interpret this as Stead foretelling his own death. They may well be right. Twenty years later, on the 15th of April 1912, William Thomas Stead met his end on the ill-fated Titanic's maiden voyage. After helping the women and children into the lifeboats, he surrendered his life jacket to one of his fellow passengers. His body was never recovered.

I am indebted to the extraordinary The W.T. Stead Resource Site, lovingly curated by Stead scholar Owen Mulpetre (BA, Mphil), for my research in writing this post.

Next month: The end of an era—a new century dawns

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

W. T. Stead in prison uniform

Photographer unknown; 1885 or later

W. T. Stead and family

Photographer unknown, late 1880s(?)

The Titanic leaving Belfast

Photo by Robert John Welch (1859-1936), official photographer for Harland & Wolff, April 2nd 1912

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit my website for details of a free download.

Published on May 01, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

eliza-armstrong, julia-ames, maiden-tribute, mediums, pall-mall-gazette, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, w-t-stead

April 1, 2014

Which covers do you prefer?

My first novel, The Bridge of Dead Things, turns one year old on April 6th. It's been a very busy year. Through my books, my website and my blog, I've published a staggering 180,000 words online. I've had some fantastic reviews here at Goodreads, and also at Amazon, Smashwords, and LibraryThing—some from as far afield as Sardinia and Nepal—many of which left me quite choked up and more than a little misty eyed. I've also had a few stinkers too, but thankfully I can (quite literally) count those on one hand.

My first novel, The Bridge of Dead Things, turns one year old on April 6th. It's been a very busy year. Through my books, my website and my blog, I've published a staggering 180,000 words online. I've had some fantastic reviews here at Goodreads, and also at Amazon, Smashwords, and LibraryThing—some from as far afield as Sardinia and Nepal—many of which left me quite choked up and more than a little misty eyed. I've also had a few stinkers too, but thankfully I can (quite literally) count those on one hand.To mark the occasion I've rebranded the series. There are new book descriptions courtesy of Monica F—catya77—a member of the LibraryThing Early Reviewers Programme where she bid for and won an advance copy of The Scarab Heart. Monica, who is also a Goodreads librarian, always included a really catchy little summary in her reviews—which I totally fell in love with—and luckily for me she said "yes" when I begged her to let me use them!

I also have a new set of book covers which I adore. You'll see the entire range (even for titles yet to be written) below. Many of my readers expressed concerns about the original covers, and I think these new ones match the books perfectly. But what do you think? Do you you agree, or do you prefer the "marmite" (some love it/some hate it) originals? You can leave me a message or, better still, why not join in the debate that I set up at the bottom of The Bridge of Dead Things book page? I would love to hear your thoughts.

If you already purchased the books, simply download them again (either from your Kindle's library or from Smashwords, if you bought them there) and choose the latest version to get the new covers. As far as I'm aware, there's no extra charge for this. You bought the books, not the cover!

If you've yet to buy them, why not check out the My Shout page on my website, michaelgallagherwrites.com, which is also celebrating its first birthday, where throughout April you will find a truly extraordinary and never-to-be-repeated offer.

Michael Gallagher

The Bridge of Dead Things:

The Scarab Heart:

The Cat Who Fishes:

The Prodigal Daughter:

The Empress of Time:

Photographs by Captain Console, Neithsabes, Marc Ryckaert, Daniel Csörföly, Eugène Atget, El Fabricio de la Mancha, John Thomson, Harris & Ewing, Inc, and whatsthatpicture

Cover designs by Negative Negative

Published on April 01, 2014 03:41

•

Tags:

bridge-of-dead-things, michael-gallagher, scarab-heart

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Mediumistic or mad?—the precarious position of women who dared to be spiritualists

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the tenth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the tenth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.Mrs Georgina Weldon (neé Thomas, 1837-1914) was one of those extraordinary, larger-than-life characters, London-born to landed gentry but with a fair soprano voice and a sense of theatre fairly pumping through her veins. Though she married for love in 1860, she soon found her talents stifled by her husband, William, who forbade her the professional life she craved and demanded she only appear in amateur theatrics and at charity benefits. In the fourth year of their marriage, which had fast turned loveless, William took a mistress to whom he stayed faithful for the rest of his life.

By the end of the 1860s Georgina's amateur croonings had fallen somewhat out of favour and her marriage was in trouble. She conceived a plan to open a musical training school for poor orphaned children, which she did in 1870, based in her own home, Tavistock House in Bloomsbury. Tavistock House was the perfect venue for such a venture: Charles Dickens, one of its previous occupants, had added a small theatre with its own stage. Georgina had some progressive ideas regarding the education of her orphans. In addition to allowing them to run barefoot for a quarter of an hour each day, they were to be taught singing, dancing and recitation from the earliest age, raised on a vegetarian diet, encouraged to join her in her amateur séances, and taken to see opera.. In return they were to pay for their keep by performing at key society events—twee musical programmes that would include a recitation of the history of the orphanage—where the whole troop would arrive in a horse and wagon with the words "Mrs Weldon's Sociable Evenings" plastered along the side. Think of Rosalind Russell's stage-mother character in the 1965 film Gypsy and you'll get the idea.

You may have noticed the words "her amateur séances". Although Mrs Weldon was an ardent supporter of spiritualism, who was lauded in the spiritualist press for rushing to the defence of the ghost-grabbed slate-writing medium Henry Slade (see the previous post), she herself was incapable of remaining sufficiently passive to allow any mediumistic powers to come to the fore.

In 1875 she and her husband separated, and William moved out of Tavistock House. He gave her the lease plus an annual allowance of £1000 as a settlement. It's impossible to know exactly what happened next, but here are the facts. At the beginning of 1878 Mrs Weldon returned in haste from a trip to France, leaving her orphans behind in the care of some nuns at a convent. She then brought criminal charges against one of her servants, someone she was convinced had stolen several items from her house. While she was being cross-examined during the servant's trial, the lawyer for the defence suggested that she was suffering from delusions. Within days she had begun to receive visits from pairs of mysterious strangers, people claiming to be fellow spiritualists interested in her charity work and enquiring about her attempts to contact the spirit world. Recognizing that something was afoot, she refused entry to a third delegation, (who, unbeknownst to her, consisted of Dr. L. Forbes Winslow—the ink-squirting alienist from the previous post—plus another man from his staff and a female nurse), and quickly started penning desperate appeals for help to all of her friends.

One of these letters was addressed to Mr W. H. Harrison, the former reporter at The Daily Telegraph to whom Florence Cook had written, who was now the editor of The Spiritualist, the leading spiritualist paper at the time. In it she detailed her suspicions that her sanity was being brought into question. Harrison responded the very next day by sending a woman named Louisa Lowe to see her, with whom he had corresponded regarding the dangers of spiritualist wives being committed to lunatic asylums by disgruntled husbands. Mrs. Lowe had barely introduced herself when Winslow and his cronies arrived for a second time and burst into the house. Mrs. Lowe quickly took charge. She instructed Georgina to barricade herself in her room and then sent for the police. The first two constables on the scene were reluctant to act, but the third demanded to be shown the lunacy order, issued at the request of Mrs. Weldon's husband and signed by two separate doctors—the mysterious strangers who had come to interview Georgina. Aided by Mrs. Lowe and the third policeman, Mrs. Weldon was bundled into cab and made good her escape. She managed to stay in seclusion for the full seven days that the lunacy order remained in force.

When she was finally at liberty to do so, she went straight to Bow Street Magistrates' Court and tried to press charges of assault. She was told that, as she hadn't actually been confined, no criminal charges could be brought against Winslow, and that, as a married woman, she couldn't bring a civil case against her husband. But Georgina Weldon was not someone to be easily thwarted. She started a campaign of harassment. She gave interviews to journalists, from the daily papers as well as from the spiritualist press, hoping to bait Winslow and her husband into suing her for libel. She spoke publicly and often about law reforms regarding lunacy. She arranged for someone to stand outside Winslow's house strapped into a pair of sandwich-boards proclaiming that the doctor was a bodysnatcher. And of course she found a way to work readings from her new pamphlet "How I Escaped the Mad Doctors" into her musical evenings, which had regained much of their popularity.

But questions remain. Was Georgina Weldon mad? It seems unlikely. The Bow Street Magistrate she'd appealed to didn't think so, nor did a number of the medical men who bothered to comment on the case in the press. And what was her husband's role in all this? Was he in fact an agent provocateur? Did William Weldon stage the thefts from Tavistock House in order to manoeuvre his wife into court? Had he instigated a whispering campaign against her? And what of the good Dr Winslow?

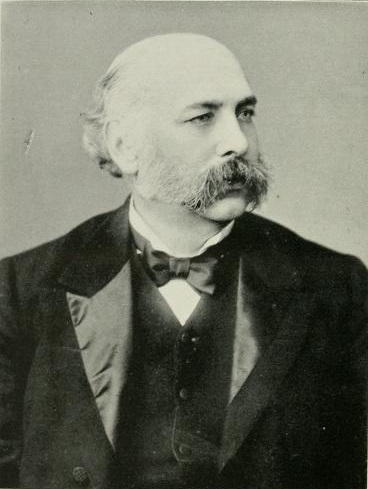

Dr Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow (1844-1913) was appointed to the Royal College of Surgeons in 1871. In 1874, on death of his father (who had helped establish the insanity plea in English law), he took over the running of his family's two private lunatic asylums. He also continued his father's work by appearing as an expert witness at every major murder trial where the defendant pleaded insanity. By 1877 he had joined the ranks of psychologists (Dr Henry Maudsley, Bedlam's director George Savage, and the University of London's Registrar William Carpenter) who had published articles warning how spiritualism was a major cause of insanity—and in Winslow's case, the major cause—amongst what they termed "weak-minded", "hysterical" women.

It's for this very reason that William Weldon approached him in 1878 with a view to getting his wife committed. As it was necessary for two doctors to examine Mrs Weldon before a lunacy order could be issued, the pair came up with the idea of having them pose as fellow spiritualists. As a result of the interviews, Winslow's first recommendation was that Georgina simply needed a companion, but when Weldon rejected this suggestion out of hand, he agreed to take her on as a patient—for an annual sum of £400, considerably less than the £1,000 (plus rent) that Weldon forked out for his wife's yearly settlement.

In the 1880s English law—as regards women—began to change. The Married Women's Property Act of 1882 gave Mrs Weldon an entirely new theatre in which to perform: the law courts. She started bringing civil suits against all those involved in the attempt to commit her, prosecuting each and every one of the cases herself, and between the years 1883 and 1888 she managed to win them all. She became the darling of the press, earned the nickname "Portia of the Law Courts", and found a staunch friend and admirer in W. T. Stead, editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, who is the subject of my next post.

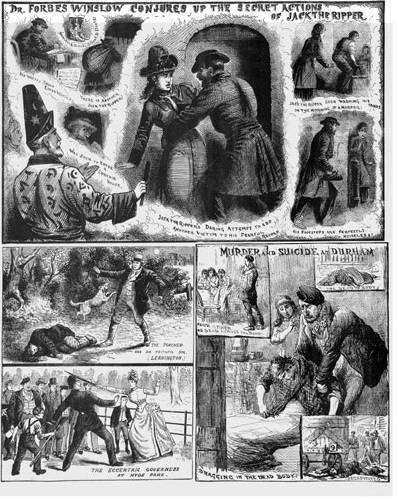

As for Winslow, it appears he suffered quite a reversal of opinion despite the suit she brought against him. It was he who organised the huge crowd of supporters to come and cheer Georgina upon her release from a six-month prison term in Holloway in 1885. Her misdemeanour? Libel. It was in fact her second stretch at Her Majesty's pleasure for such an offence. Three years later Winslow became embroiled in the Jack the Ripper case, proposing that the Ripper hailed from the upper classes. So passionately did he expound his theory that for a short time he became a police suspect himself.

Next month: W. T. Stead—the man who foresaw his own death?

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Carte-de-visite of Georgina Weldon (1837-1914)

Elliot & Fry Studios, circa 1884

Husband William Weldon (1837-1919) in later life, ceremonially dressed for the coronation of King Edward VII

Photographer unknown, 1902

Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow (1844-1913)

Photograph by Alexander Bassano (1829-1913), date unknown

Dr. Forbes Winslow conjures up the secret actions of Jack the Ripper (top panel)

From The Illustrated Police News, circa 1889

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit my website for details of a free download.

Published on April 01, 2014 03:38

•

Tags:

forbes-winslow, georgina-weldon, jack-the-ripper, louisa-lowe, mediums, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, tavistock-house, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, w-h-harrison

March 1, 2014

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.So far in this history we've already encountered a number of ghost-grabbers: Noah Brooks, the American journalist with the Sacramento Daily Union, who literally grabbed the trance medium Lord Colchester's hand at a séance instigated by Mary Todd Lincoln, and the English lawyer, William Volckmann, who seized the spirit of Katie King by the waist and refused to let go—despite being tackled by two of Florence Cook's confederates who were stationed in the audience, one of whom she ended up marrying a mere four months later. Both instances were brutal and bloody. Brooks received a blow to his forehead with a drum that Colchester used in his performance; Volckmann, who was in league with the medium Agnes Guppy—one of Florence's rivals—had part of his beard torn away. Florence was ghost-grabbed again some years later, you may recall, this time by the twenty-year-old Sir George Sitwell at the assembly rooms of the National British Association of Spiritualists in 1880. It spelled the end of her career. She was forced to retire and move to Wales.

Another victim to be caught out several times was the medium Henry Slade (1835-1905), who was noted for his chalked spirit messages that would "miraculously" appear on a conveniently-held slate. Having been twice unmasked as a fraud in America (first by John W. Truesdell in 1872, then by Stanley LeFevre Krebs), he came to Britain to ply his trade. Here he was thwarted by Ray Lankester (1847-1929), a twenty-nine-year-old professor of zoology at University College London, who in 1876 snatched the pre-inscribed slate from the medium's grasp. Slade was brought to trial and found guilty of fraud, but successfully appealed his conviction on a technicality, that the original charge had omitted the words "by palmistry or otherwise". Before fresh charges could be brought he'd fled the country and returned to America.

Ghost-grabber Lankester was one of a growing group of scientific men, as was William Benjamin Carpenter (1813-1885), a colleague of his who had recently been appointed Registrar of the University of London, and Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow (1844-1913), an alienist (an early form of psychologist), all of whom were beginning to challenge the most basic precepts of spiritualism, possibly as a reaction to William Crookes's reviled report, Notes of an Enquiry into the Phenomena called Spiritual, published some two years before Slade's trial. Winslow (or Forbes-Winslow, as he eventually came to style himself) used red ink in pursuit of charlatans. He would squirt it in the faces of any spirits that happened to materialize in his presence. He's a fascinating character who I will return to in the next post.

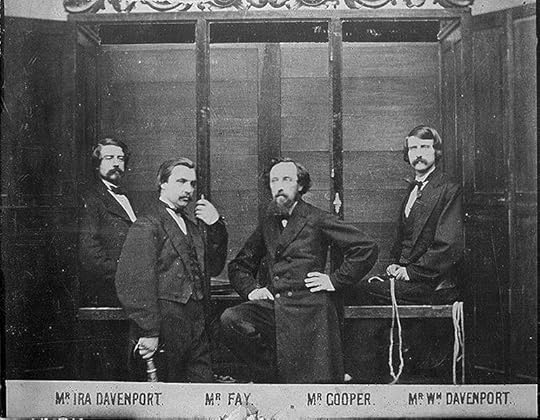

But it wasn't just scientists who worked to unmask frauds. It was often stage magicians who proved far more ruthless as opponents. Even by the mid-1860s a professional hatred had emerged that separated stage magicians, who claimed no spiritual intervention for their illusions, from spiritualist mediums, who did. Such was the case with the two Davenport brothers, Ira and William, who like Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home before them, came to Britain from America either at the end of 1864 or the beginning of 1865.

Ira Davenport was born in the September of 1839; his brother William was born less than two years later in 1841. They were the sons of a policeman and grew up in Buffalo, New York. They claimed to have discovered their mediumistic powers when Fox-style rappings broke out at their house in 1846, two years before those of the Fox sisters, when Ira was seven years old and William barely five. By 1854, when both boys were still teenagers, they had already come up with the basic building blocks of their act. Managed by their father, tutored by a local amateur conjurer, William Fay, and introduced on stage by Dr J. B. Ferguson, a former minister of religion who truly believed in the brothers' spiritualistic abilities, they started giving shows across America, from which they earned their living for the next ten years.

While the séances of Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home may have relied rather heavily on creating a specific eerie atmosphere where people's heightened senses would cause them to jump out of their skin at the slightest unexpected sound, the Davenports took the opposite view: they relied on overkill. Their act was designed as a public performance, where the people in the back stalls could see and hear everything that happened equally as well as those at the front—and see and hear it they did!

Bound hand and foot by ropes that were then sealed with sealing-wax, and subsequently shut inside their "spirit cabinet", the brothers would make a racket with an array of musical instruments that had been placed on the cabinet floor. The two cabinet doors would alternately burst open and slam shut, revealing one bound brother then the other, while instruments went flying through the air, often being hurled directly into the audience.

In England the Davenports initially found some support. Richard Burton, the translator of—for its time—the extremely racy Arabian Nights had this to say in their defence: "I have spent a great part of my life in Oriental lands, and have seen their many magicians. Lately I have been permitted to see and be present at the performances of Messrs. Anderson and Tolmaque. The latter showed, as they profess, clever conjuring, but they do not even attempt what the Messrs. Davenport and Fay succeed in doing…"

Unfortunately a number of amateur British magicians disagreed. Two of their ilk joined the tour in Liverpool in the February of 1865 and, upon "volunteering" from the audience, bound the brothers' hands so tight with knots that couldn't be undone that their wrists bled. The Davenport brothers were eventually cut free but refused to continue. The audience, unimpressed by what they'd witnessed, stormed the stage and smashed their cabinet to pieces. The perpetrators of the knot-tying struck again at their gig in Huddersfield—then later at Leeds—and each time they did, the violence escalated. Ira and William cancelled their remaining English dates and took their show to Europe.

But a twenty-five-year-old watchmaker named John Nevil Maskelyne, who had seen the brothers' act, had worked out how the trick was managed. He and his friend, George Alfred Cooke, built their own spirit cabinet and gave their own public demonstration—minus all spiritualist trappings—in June of 1865. Word of their performance was rapidly spread by the fascinated British press. Their success in unmasking the Davenports ignited their passion for stage magic, and the two went on to create many further illusions, some of which are still performed today.

As for the Davenports, the youngest brother, William, died in 1877 in Sydney, Australia, at the age of thirty-six. Ira moved back to America, where died in 1911. Before his death he wrote to Harry Houdini, famous escapologist and unmasker of psychics, claiming that he and William had never publicly stated their belief in spiritualism. But the truth is probably best represented by Ira's obituary in one American newspaper: "They made the mistake of appearing as sorcerers instead of as honest conjurers. If, like their conqueror, Maskelyne, they had thought of saying, 'It's so simple,' the brethren might have achieved not only fortune but respectability."

Next month: Mediumistic or mad?—the precarious position of women who dared to be spiritualists

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Carte-de-visite of John Nevil Maskelyne, illusionist and magician (1839-1917)

Photographer and date unknown

Henry Slade (1835-1905)

The Davenport brothers seated in their spirit cabinet, with their asscociates Mr Fay and Mr Cooper in the foreground

Photographer unknown; 1870

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit my website for details of a free download.

Published on March 01, 2014 06:20

•

Tags:

agnes-guppy, davenport-brothers, florence-cook, forbes-winslow, ghost-grabbers, henry-slade, houdini, katie-king, lankester, lord-colchester, mary-lincoln, maskelyne, mediums, noah-brooks, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, volckmann

February 1, 2014

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Caught on camera—the darker role that photography played in spiritualism

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.It probably started out as a happy accident: a glass plate that had previously been exposed but not yet developed was placed back into the camera and exposed for a second time. The resulting double-exposure, when printed, would have produced a somewhat ghostly effect. With a certain amount of pre-planning and a little tweaking here and there, the effect could be heightened and repeated time and time again. Such is undoubtedly the case with the American William H. Mumler (1832-1884), who started out as an amateur photographer in Boston. Realising that he could make his living by photographing New England’s many mediums in the company of assorted spirits, he quit his job as an engraver and moved to New York in the early 1860s to take up his particular brand of photography full time. His most famous photo appears to show Mary Todd Lincoln flanked by the spirit of her dead husband.

In the April of 1869 Mumler was brought to trial for fraud after it was alleged that he’d broken into houses to steal the portraits of his sitters’ dead relatives. One of the witnesses to testify against him was the showman and entrepreneur P. T. Barnum. Barnum had commissioned the photographer Abraham Borgadus to make a portrait of him accompanied by Abraham Lincoln’s spirit, just like Mary’s, to demonstrate how easily it was that such photos could be faked. The photograph was presented in evidence at the trial. Although Mumler was eventually acquitted, his career as a spirit photographer was over.

How could people be so gullible? To answer this question it's important to appreciate the naivety of the general public in their ability to read and understand photographs at the time. The following extract is from Statement of a Photographic Man, from Volume 3, Part IV (Street artists) of Henry Mayhew's 1861 work, London Labour and the London Poor. The speaker is a young working-class man from the slums of Lambeth, who, on tiring of busking for his living, borrows money for a camera and darkroom equipment and sets up as a photographer with his mate Jim, though both men lack the technical expertise required. Through trial and error his work gradually improves, but along the way he dreams up a number of hilarious tricks and dodges to mask his failures, one of which, the fobbing-off on impatient customers of hastily-wrapped specimen-photographs taken from his window display, he discusses here:

"…We have made some queer mistakes doing this. One day a young lady came in, and wouldn't wait, so Jim takes a specimen from the window, and, as luck would have it, it was the portrait of a widow in her cap. She insisted on opening, and then she said, 'This isn't me; it's got a widow's cap, and I was never married in all my life!' Jim answers, 'Oh, miss! why it's a beautiful picture, and a correct likeness,'—and so it was, and no lies, but it wasn't of her. Jim talked to her, and says he, 'Why this ain't a cap, it's the shadow of the hair'—for she had ringlets—and she positively took it away believing that such was the case; and even promised to send us customers, which she did.

"There was another lady that came in a hurry, and would stop if we were not more than a minute; so Jim ups with a specimen, without looking at it, and it was the picture of a woman and her child. We went through the business of focussing the camera, and then gave her the portrait and took the 6d [half a shilling]. When she saw it she cries out, 'Bless me! there's a child: I haven't ne'er a child!' Jim looked at her, and then at the picture, as if comparing, and says he, 'It is certainly a wonderful likeness, miss, and one of the best we ever took. It's the way you sat; and what has occasioned it was a child passing through the yard.' She said she supposed it must be so, and took the portrait away highly delighted.

"Once a sailor came in, and as he was in haste, I shoved on to him the picture of a carpenter, who was to call in the afternoon for his portrait. The jacket was dark, but there was a white waistcoat; still I persuaded him that it was his blue Guernsey which had come up very light, and he was so pleased that he gave us 9d [three-quarters of a shilling] instead of 6d. The fact is, people don't know their own faces. Half of 'em have never looked in a glass half a dozen times in their life, and directly they see a pair of eyes and a nose, they fancy they are their own.

"The only time we were done was with an old woman. We had only one specimen left, and that was a sailor man, very dark—one of our black pictures. But she put on her spectacles, and she looked at it up and down, and says, 'Eh?' I said, 'Did you speak, ma'am?' and she cries, 'Why, this is a man! here's the whiskers.' I left, and Jim tried to humbug her, for I was bursting with laughing. Jim said, 'It's you ma'am; and a very excellent likeness, I assure you.' But she kept on saying, 'Nonsense, I ain't a man,' and wouldn't have it. Jim wanted her to leave a deposit, and come next day, but she never called…"

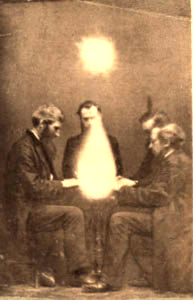

The photographs of the spirit of Katie King, however, stretch credulity to a brand new level. The first set was taken in a hotel room at Florence Cook's request by the reporter W. H. Harrison with an eye to publication in The Daily Telegraph; the rest—the ones we're most familiar with today—were taken by the scientist William Crookes at two private but well-attended soirées in his own home. In both cases neither the negatives nor the prints were tampered with in any way, and, considering the circumstances, it seems unlikely that Crookes (if not Harrison too) set out to perpetrate any fraud. But, studying them, it's hard to imagine that anyone was fooled. The words of Edward William Cox when describing one of Katie's later appearances sum up the situation neatly, "They were solid flesh and blood and bone."

People see what they want to see. The photo you see below is another interesting case in point. It was taken by a sixteen-year-old in 1917 and features her nine-year-old cousin sitting in their garden surrounded by a number of posed, cut-out fairy figures.

Again, there is no double-exposure or tampering with the print. What you see is exactly what you get. Yet this image was passionately championed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series, who, despite his naivety, was a great believer in spiritualism. And he was not the only person to be taken in. Here is what Edward Gardner, a leading member of the Theosophical Society at the time, had to say: "…the fact that two young girls had not only been able to see fairies, which others had done, but had actually for the first time ever been able to materialise them at a density sufficient for their images to be recorded on a photographic plate, meant that it was possible that the next cycle of evolution was underway."

Frances, the young girl in the photo, finally admitted to the fraud in later life: "I never even thought of it as being a fraud—it was just Elsie and I having a bit of fun and I can't understand to this day why they were taken in—they wanted to be taken in."

Fifty years after Mumler, professional debunkers—often stage magicians who objected to their artistry being brought into disrepute by spiritualist hoaxers—were still at work trying to expose the tricks involved in the production of spirit photography. Here is one of the most recent examples I could find, showing Houdini, one of the greatest escapologists and debunkers of all time, with (yet again) the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, who must surely be the most photographed "spirit" on the planet.

Next time: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.Images:

Seance conducted by John Beattie, in Bristol, England

Photograph by Eugene Rochas, 1872

Mary Todd Lincoln with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln

Photograph by William H. Mumler, date unknown but presumably prior to 1869

P. T. Barnum with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Barnum's request

Photograph by Abraham Bogardus, 1869

William Crookes with the spirit of Katie King

Photograph by William Crookes, circa 1873

Frances Griffiths surrounded by fairies

Photograph by Elsie Wright, 1917

Houdini with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Houdini's request

Photographer unknown, circa 1920-1930

Library of Congress

Published on February 01, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

barnum, crookes, florence-cook, houdini, lincoln, mayhew, mediums, mumler, pictures-of-ghosts, seances, spirit-photography, spiritualism, spiritualists, statement-of-a-photographic-man, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

January 1, 2014

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: the full-body materializations of Florence Cook

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the seventh in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism. **Please note that it is edited from articles that I have previously posted, but its inclusion here helps to make sense of the history.**

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the seventh in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism. **Please note that it is edited from articles that I have previously posted, but its inclusion here helps to make sense of the history.**Florence Eliza Cook was born on June 3rd 1856 in Cobham, Kent to parents Henry and Emma Cook, who moved to London when she was three and took up residence at 6 Bruce Villas, Eleanor Road, Dalston. She was the eldest of four children.

In 1870, at the age of fourteen, she began table-rapping experiments with her friends and family, surprising everyone when a violent burst of poltergeist activity ensued. A spirit responding to her questions through a system of yes-or-no raps informed her that she was indeed a medium and then directed her to the local Spiritualist Association. By the following year she'd started working for a pair of established mediums, Frank Herne and Charles Williams, and reports of her séances were beginning to crop up in the spiritualist press. Herne's spirit-guide was an entity named John King, who rather confusingly claimed to be the ghost of Sir Henry Morgan, the famous buccaneering pirate. Florence's guide was Katie King, John's daughter, who also claimed to be Annie Owens Morgan, the daughter of the pirate. At this point there was none of the bodily manifestations of Katie that came later; there were simply disembodied voices, messages written by unseen hands, and phenomena known as "apports"—objects that appeared to fall from the ceiling.

There is a truly fascinating story of one such occurrence: early in the June of 1871 Herne and Williams were conducting a séance together for eight sitters around a table at 69 Lamb's Conduit Street when the voices of Katie King and her father were heard in the darkness. Katie offered to produce a gift for the group and one of the sitters suggested—half jokingly—that she bring them Agnes Guppy, an extremely stout medium famed for her own apports who lived some miles away in Highbury. Katie laughed—everybody laughed—and though her father protested she agreed to go through with it. Suddenly there was a loud thump; somebody screamed. When one of the company had the presence of mind to light a lamp, there on the table in front of them, apparently in some kind of trance, was perched the stout Mrs Guppy in a state of semi-undress, account book and pen still in hand.

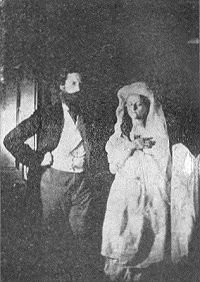

By the beginning of 1873 Florence was performing her own séances at the Cook family home in Dalston, but by now there were full materialisations. The audience, often comprised of highly respectable professional men and women, would sit in the dimly-lit parlour while Florence was bound by ropes before retiring to an adjoining room screened off from view by a thin damask curtain. Presently the spirit of Katie King would appear dressed in white, and walk about the room telling the story of her former life as Annie Morgan, the buccaneer's daughter. It was a charming tale. Annie had been twelve years old when Charles the First was beheaded; she'd married and had two little children; she'd committed more crimes than she cared to confess; she'd even murdered men with her own two hands; she'd died young. To questions concerning the reason of her reappearance back on earth, she claimed that it was part of the work she'd been entrusted with, to convince the world of the truth of Spiritualism.

In Spring of that year Florence Cook held a series of sittings designed to capture a photographic likeness of Katie. On the 7th of May, Mr W. H. Harrison, a reporter for the Daily Telegraph (who in later years went on to edit The Spiritualist, a London-based magazine dedicated to examining spiritualist phenomena from a scientific perspective), successfully managed to take the first four photographs of Katie. More sittings followed where the highly respected scientist William Crookes took a total of forty-four photos, all the while performing tests on Florence as part of his on-going investigation into spiritualist mediums. These sittings were held at Crookes's own house on Regent's Park, which was one of the conditions he imposed on all his test subjects.

Florence was fast becoming famous, but fame breeds jealousy. At a séance held on the 9th of December the lawyer William Volckmann seized Katie King by the waist and refused to let go. Some of those present claimed that the spirit "glided" out of Volckmann's grip; others suggest that she defended herself quite vigorously (Volckmann lost part of his beard). Edward Elgie Corner, a ship's captain from Dalston, who was a family friend of the Cooks as well as being their neighbour, together with another of her supporters rushed to Katie's aid. The gaslights were rapidly extinguished, there was a great deal of scuffling, and by the time peace was eventually restored and the room re-lit, Katie King had vanished and Florence was discovered still secured by her ropes. As Volckmann was most likely in league with Agnes Guppy (the formidable medium from Highbury who'd landed on the table in a state of semi-undress—whom he in fact married after her elderly husband passed away barely a year later), it would seem that Florence's relationship with her erstwhile colleague had soured considerably.

Volckmann's attack damaged her reputation. Unfortunately Crookes's report, Notes of an Enquiry into the Phenomena called Spiritual during the Years 1870-1873, published a month later in the Quarterly Journal of Science (January 1874) did little to restore it, despite his vehement assertion that Florence Cook, the American Kate Fox, and the Scotsman Daniel Dunglas Home, were all genuine mediums producing perfectly genuine results.

The séances continued. Florence teamed up with another girl, Mary Rosina Showers. The pair gave a séance at the Crookes home in March of 1874 which was attended by a number of witnesses, among them the barrister, Serjeant-at-law Edward William Cox. Cox took a deep—though not uncritical—interest in spiritualism; it was he who had first hosted and championed Daniel Dunglas Home on his return from America. He published his observations some weeks later in The Spiritualist, the leading newspaper in its field, which the reporter W. H. Harrison would go on to edit. Of the materialisations he wrote: "They were solid flesh and blood and bone. They breathed, and perspired, and ate…Not merely did they resemble their respective mediums, they were…alike in face, hair, complexion, teeth, eyes, hands, and movements of the body…"

As regards proof that they were not simply the two girls themselves, he wrote: "…no proof whatever was given or offered or permitted. The fact might have been established in a moment beyond all doubt by the simple process of opening the curtain and exhibiting the two ladies then and there upon the sofa, wearing their black gowns. But this only certain evidence was not proffered, nor, indeed, was it allowed us…"

On the 29th of April 1874 Florence Cook married Captain Edward Elgie Corner, the neighbour who had rushed to Katie's aid the previous December. Though their marriage was blessed with two daughters, Kate and Edith, it was not a happy one.

The final appearance of Katie King was a truly sad occasion. She had often stated that she could not appear on this earth beyond the month of May, 1874, and so, on the 21st, she assembled her friends together to bid them all goodbye. This eye-witness account was written by the stage actress and internationally successful author Florence Marryat:

"Katie had asked Miss Cook to provide her with a large basket of flowers and ribbons, and she sat on the floor and made up a bouquet for each of her friends to keep in remembrance of her. Mine, which consists of lilies of the valley and pink geranium, looks almost as fresh to-day, nearly seventeen years after, as it did when she gave it to me. It was accompanied by the following words, which Katie wrote on a sheet of paper in my presence: 'From Annie Owen de Morgan (alias "Katie") to her friend Florence Marryat Ross-Church. With love. Pensez à Moi. May 21st 1874.' The farewell scene was as pathetic as if we had been parting with a dear companion by death. Katie herself did not seem to know how to go. She returned again and again to have a last look, especially at Mr. Alfred [William] Crookes, who was as attached to her as she was to him."

Of that final parting, this is what William Crookes himself wrote: "Having concluded her directions, Katie invited me into the cabinet with her, and allowed me to remain there to the end. After closing the curtain she conversed with me for some time, and then walked across the room to where Miss Cook was lying senseless on the floor. Stooping over her, Katie touched her and said, 'Wake up, Florrie, wake up! I must leave you now.' Miss Cook then woke and tearfully entreated Katie to stay a little time longer. 'My dear, I can't; my work is done. God bless you!'…For several minutes the two were conversing with each other, till at last Miss Cook's tears prevented her speaking. Following Katie's instructions, I then came forward to support Miss Cook, who was falling on to the floor, sobbing hysterically. I looked around, but the white-robed Katie had gone…"

It would be impossible not to compare Cox's statement with that of Crookes's, or Florence's likeness with that of Katie's. But I will tell you this: I am absolutely convinced that William Crookes was not lying about what he saw.

Though Katie was never to appear again, Florence went on to host two further spirit-guides during her lifetime: firstly Leila in 1875 (the same year that Frank Herne, the medium who'd set Florence on her career-path was debunked as a fraud), and then later a French girl who called herself Marie, who was said to have "danced and sung in a truly professional style".

Five years on, Florence was ghost-grabbed for a second time, on this occasion by the young Sir George Sitwell, a 20-year-old Oxford University student, at a public séance being given at the rooms of the National British Association of Spiritualists in 1880. The débâcle ruined her, and she retired and moved to Wales. The incident brought Sir George some notoriety too and he soon left Oxford without taking a degree. He ended up fathering a daughter, the future Dame Edith Sitwell, truly England's most eccentric poet who became something of an entertainer herself. In 1923 she alienated her audience by standing out of sight behind a starkly-painted screen while shouting her poems at them through a megaphone, all in time to William Walton's carefully arranged score of Façade – An Entertainment.

In 1899 Florence tried to revive her career when she was invited to Berlin to undertake a series of séances under test conditions by the Sphinx Society. She died of pneumonia in relative poverty at 20 Battersea Rise, London, on the 22nd of April 1904 at the age of 48. Her husband outlived her by a quarter of a century and died in 1928.

William Crookes received his knighthood in 1897 and the Order of Merit in 1910. He died in 1919. Towards the end of his life he sought out mediums to help him communicate with his beloved wife, who had predeceased him by two years.

I'd like the last words to go to the fifteen-year-old Florence Cook herself. In a letter to Mr W. H. Harrison (the Telegraph reporter who would later take the first photographs of Katie), dated May, 1872, she writes: "From my childhood I could see spirits and hear voices, and was addicted to sitting by myself talking to what I declared to be living people. As no one else could see or hear anything, my parents tried to make me believe it was all imagination, but I would not alter my belief…"

Next month: Caught on camera—the darker role that photography played in spiritualism

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit the “My Shout” page on my website for details of a free download.

Images:

Florence Cook (1856-1904)

Photographer and date unknown

Katie King

Photograph by William Crookes (1832-1919), circa 1873/1874

Katie King

Photograph by William Crookes (1832-1919), circa 1873/1874

Mrs Edward Elgie Corner (1856-1904)

Photographer and date unknown

Published on January 01, 2014 06:32

•

Tags:

agnes-guppy, crookes, edward-william-cox, florence-cook, katie-king, marryat, materializing-medium, rosina-showers, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, volckmann

December 1, 2013

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Guess who's coming to dinner?—the extraordinary life of medium Daniel Dunglas Home

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the sixth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the sixth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.Daniel Dunglas Home (pronounced "Hume") was arguably the most extraordinary medium of the Victorian era, not least because he managed to live the majority of his life in sumptuous style—courtesy of an ever-lengthening list of wealthy patrons—and all the while claiming not to accept a penny for his services.

He was born plain Daniel Home on March 20th 1833 in Scotland, in the small village of Currie, six miles south of Edinburgh. His father, the illegitimate son of the 10th Earl of Home, was a bitter and morose man who worked at the local paper mill, and his mother, who was said to possess second-sight, was locally thought to be fey. He was their third child, and at an early age was given over to the care of his mother's childless sister, Mary Cook (no relation to Florence Cook, the subject of the next post), who lived with her husband in the rapidly developing coastal resort and manufacturing town of Portobello, a few miles to the east on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth.

In 1842 at the age of nine he emigrated with his adoptive family, traveling steerage class to New York before settling for a time in Greeneville, Connecticut, on the banks of the Shetucket River. Daniel attended school there, and though a shy and retiring boy, he managed to befriend another student, whose name was Edwin. By the time Daniel turned thirteen the two had became so inseparable that they made a pact, one which had been inspired by a short story they both enjoyed of a man who returned from the dead to make his presence felt by his lady-love: if either were to die, he would try to make contact with the other from beyond the grave. It came to pass. When Daniel's family moved one-hundred-and-fifty miles away to Troy, New York, Daniel had a vision of his friend standing at the foot of his bed. He later learned that Edwin had succumbed to dysentery.

The family returned to Greenville, where they were reunited with Daniel's natural family, who had in the meantime emigrated from Scotland to settle in the sheep-farming town of Waterford, some twelve miles away. One evening in 1850, while the seventeen-year-old Daniel was suffering a bout of fever (quite possibly a symptom of the tuberculosis he was later diagnosed as having), he had a vision of his mother telling him that she had died that day at twelve o'clock. This too turned out to be true. Soon loud rapping noises, similar to those produced by the Fox sisters two years earlier, could be heard throughout the house. Exorcisms were performed, but to no avail. His aunt, Mary Cook, became convinced that Daniel had the devil in him and ordered him to leave her house. He went to stay with friends, thus beginning his life-long career as a professional non-paying guest.

His mediumship followed next. In March of 1851, around the time of his eighteenth birthday, Home found himself performing at the residence of William and Maria Hayden of Hartford, Connecticut. As I mentioned last time, if this was not his first séance, it was certainly one of his very first. The evening was reported in the local press (most probably in a letter to the editor) by Mr Hayden, a family doctor, who described how Home had managed to move a table about the room without anybody touching it. His fame soon spread throughout New England, and then to New York and Massachusetts, while his talents became ever more diverse. For the next four years he would give as many as six séances a day offering a mixture of table turning, spiritual healing, communication with the dead, the partial manifestation of body parts (such as hands), and acts of levitation and of self-levitation in the homes of his patrons, who generally adored him. One particular couple, Mr. and Mrs. Elmer, who were rich and childless, offered to adopt him and make him their heir. Presumably he refused their offer, as it was conditional on his changing his surname to Elmer, which he never did. Towards the end of this period his health declined. In 1854 he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and advised (by Maria Hayden's husband William, I suspect, who had returned from England at the end of the previous year) to take a rest cure in Europe. He gave his final American séance in March 1855 in Hartford, then set sail for Liverpool, England, just days after his twenty-second birthday.

Having added the "Dunglas" part to his name, Home took up residence at a hotel in Jermyn Street, London, as a guest of the owner, the well-to-do property speculator, publishing magnate and barrister Edward William Cox. It is likely that he and Cox, who took a deep—though not uncritical—interest in spiritualism, shared a mutual friend: Maria B. Hayden. Though weakened by the tuberculosis, it was here that Home held sittings for many influential people from London society. As the list of his acquaintances grew, so did the number of offers of accommodation. He moved his base of operations to the home of the wealthy Rymer family of Ealing, and financed by them, set off on a tour of Europe in 1856 in the company of their eldest son. Whilst in Italy the two had a rather acrimonious falling-out and swiftly parted ways, but not before Home had established his reputation on the Continent as a first-rate medium.

Over the next few years he performed extensively throughout Europe, always for the royal, the rich and the famous (Queen Sophia of the Netherlands and Napoleon III among them), and always only at private sittings. In Paris in 1857 he was offered £2,000 for a single séance by the Union Club, but he declined their offer. In 1858, at the age of twenty-five, he married Alexandria de Kroll, the daughter of a Russian noble, whom he had met on a trip to St. Petersburg. The best man at the wedding was the novelist Alexandre Dumas; the union had the blessing of Alexander II, Emperor of Russia. But the marriage was not to last. Alexandria died of tuberculosis in 1862.

By this point Home had already resumed giving private sittings in Britain. In 1863 he published the first of two memoirs, both of which he entitled Incidents in my Life, detailing his various psychic successes amongst the titled and the rich, but referring to his clients in ciphers such as "Countess O" (Countess Orsini), "Count de K" (Count de Komar), and "Princess de B" (Princess de Beauveau). He was now thirty, and still relied on his charms and pallid good-looks, in addition to his friends, to make his way in the world. In 1866 he received, for the second time in his life, an offer of adoption, this time from a wealthy widow named Mrs. Jane Lyon. She settled £60,000 on Home on the condition that he change his surname to Home-Lyon. The offer must have been appealing, for this time he did change it. In addition to receiving letters of affection from her newly-appointed heir, Mrs. Lyon expected him to provide her with an entrée into polite society. Although he dutifully wrote her letters, when the anticipated introductions didn't materialize she demanded her money back. Home failed to comply and she brought charges against him, claiming he had extorted it from her by misrepresentation. The case was tried at the Court of Chancery. Home lost and was obliged to return the money.

The press had a field day, but his society friends stood by him throughout. In 1867 he made the acquaintance of the twenty-six-year-old Lord Adare, the future fourth Earl of Dunraven, who had recently been appointed as a war correspondent to the Daily Telegraph. The young Viscount, who, to put it tactfully, struggled with his sexuality, became infatuated with Home—clearly as others had done before him. He also started documenting the extraordinary feats he saw. On Sunday December 13th 1868 Home performed what was to become his most famous act of levitation when, in the presence of Adare and two other witnesses, he floated head-first out of a third-story bedroom window, returning feet-first through the windows of a sitting room on the other side of the house.

One person who bore witness to Home's levitations on many occasions was the noted scientist William Crookes. Between 1870 and 1873 under carefully controlled conditions he put a number of mediums to the test—Daniel Dunglas Home, Kate Fox of the Fox sisters (who travelled to Britain in 1871 under the patronage of a New York banker, then married the London barrister, Mr. H. D. Jencken, the following year), and the materializing medium Florence Cook, the subject of the next post—and found all three to be capable of producing perfectly genuine results.

By 1871, however, three years before the publication of Crookes's report, Home was exhausted. At the age of thirty-eight he retired as a medium due to ill-health. In the October of that year he married Julie de Gloumeline, yet another wealthy Russian, with whom he lived until his death in 1886. He was buried in the Russian cemetery in St Germain, Paris. After his death, his widow published an account of his career, but it failed to become as popular as Home's own self-penned testimonies.

Next month: the full-body materializations of Florence Cook

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

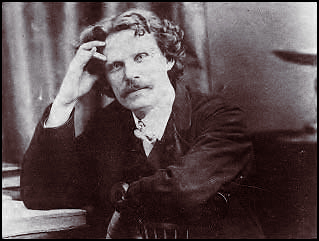

Images:

Daniel Dunglas Home (1833-1886)

Photographer and date unknown

Published on December 01, 2013 06:13

•

Tags:

d-d-home, daniel-dunglas-home, mediums, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

November 1, 2013

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: exports to Britain

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fifth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fifth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.It wasn't long before the rapping-type séances popularised by the Fox sisters in the late 1840s spread abroad—here to Britain. The first emissary to arrive at these shores was Mrs Maria B. Hayden (1826-1883). Born in Nova Scotia, she married one William R. Hayden in a ceremony in Boston in 1850. She was his second wife. Maria's mediumship began in the March or April of 1851, at the age of 25, after a séance held by the Haydens at their Hartford home in Connecticut, New England. The medium they invited to preside over the occasion was an 18-year-old youth, Daniel Home (pronounced "Hume", of whom we will learn more next month). If not his first séance, it was at least one of his very earliest. According to Home in his memoirs, Incidents in my Life (1863), the evening was reported in the local press by Maria's husband, William, who described how Home had managed to move a table about the room without anybody touching it.

As an important aside, William Hayden is usually depicted as a wealthy and influential newsman, congressional reporter, and eventual editor of the Boston Atlas, as well as being a dedicated abolitionist. This view, which has been the prevailing one since the late Victorian period, has recently been challenged by a direct descendant of Maria Hayden, who presents a compelling case that he was in fact a family physician. Based on the very limited evidence I could find of his published writings (one letter to the editor of an American newspaper concerning the couple's first few months in London, which, as you will see, reads exactly like an ordinary letter-to-the-editor), I would tend to agree. Equally, if he were a physician, it would go some way to explain why in later years Maria Hayden herself trained as a doctor, at a time when few women would have the opportunity or receive the encouragement to do so.

After achieving a certain degree of success at table rapping, Maria and her husband set sail for Britain in October 1852 with the sole aim of spreading the spiritualist message. Unfortunately the couple met with a rather hostile reception in London, as the letter written by her husband attests:

"22 QUEEN ANNE STREET, CAVENDISH SQUARE, LONDON, Feb. 4, 1853. Dear Sir– I think I promised, before leaving New York, in September last, to write to you and let you know how we succeeded in England…Thus far we have had much opposition to contend against, but have met with a remarkable few failures. The worst was that of two of Dickens' friends, who paid Mrs. H. a visit a few days after her arrival. They evidently came with the intention of having every thing [go] wrong, and they nearly succeeded to their mind." [excerpt of letter from William R. Hayden to Samuel Byron Brittan, editor of the American weekly periodical The Spiritual Telegraph]

George Henry Lewes, who was later to become the partner of the author George Eliot, played an especially mean trick on Mrs Hayden. Unseen by Maria, he wrote out a question on a sheet of paper: "Is Mrs Hayden an impostor?" The spirit controlling Maria rapped out: "Yes." Lewes went on to claim this as an admission of her guilt.

Though the literary world may not have been kind to her, Maria Hayden was not without her supporters. Both Sir Charles Isham, 10th Baronet of Isham, and Dr Ashburner, one of the Royal physicians, defended her very publicly in the press. Another convert to her cause was Professor Augustus de Morgan, philosopher and mathematician, whose work on logic, differential calculus, and probability is still remembered to this day. This is his recollection of one of the séances he attended:

"At a late period in the evening, after nearly three hours of experiment, Mrs. Hayden having risen, and talking at another table while taking refreshment, a child suddenly called out, "Will all the spirits who have been here this evening rap together?" The words were no sooner uttered than a hailstorm of knitting-needles was heard, crowded into certainly less than two seconds; the big needle sounds of the men, and the little ones of the women and children, being clearly distinguishable, but perfectly disorderly in their arrival." [from Professor de Morgan's preface to his wife's book, From Matter to Spirit, 1863]

It's been said that Maria had a limited mediumship consisting mainly of raps, but, as we've seen in the case of George Henry Lewes, she was also a "test" medium, in that she fielded questions where the answers were known only to the sitter. At least one person was greatly impressed by Mrs Hayden's talents in this regard—the tragedian actor Charles Young. Here is an account of their meeting—though be aware, confusingly it is in fact written by his son, the Rev. Julian Young, some years later:

"1853, APRIL 19TH. I went up to London this day for the purpose of consulting my lawyers on a subject of some importance to myself, and having heard much of a Mrs. Hayden, an American lady, as a spiritual medium, I resolved, as I was in town, to…judge of her gifts for myself…I was so astounded by the correctness of the answers I received to my inquiries that I told the gentleman who was with me that I wanted particularly to ask a question to the nature of which I did not wish him to be privy, and that I should be obliged to him if he would go into the adjoining room for a few minutes. On his doing so I resumed my dialogue with Mrs. Hayden.

Mr. Charles Young: I have induced my friend to withdraw because I did not wish him to know the question I want to put, but I am equally anxious that you should not know it either, and yet, if I understand rightly, no answer can be transmitted to me except through you. What is to be done under these circumstances?

Mrs. Hayden: Ask your question in such a form that the answer returned shall represent by one word the salient idea in your mind.

Mr. Charles Young: I will try. Will what I am threatened with take place?

Mrs. Hayden: No.

Mr. Charles Young: That is unsatisfactory. It is easy to say Yes or No, but the value of the affirmation or negation will depend on the conviction I have that you know what I am thinking of. Give me one word which shall show that you have the clue to my thoughts.

Mrs. Hayden: Will.

Now, a will by which I had benefited was threatened to be disputed. I wished to know whether the threat would be carried out. The answer I received was correct." [The Spiritualist, November 22nd, 1878]

Despite Maria Hayden's séances being essentially private, domestic affairs, by April she was charging a fee of one guinea (one pound and one shilling; i.e., twenty-one shillings in total) per person to attend them. Newsman or not, in May her husband William did set up a magazine, The Spirit World, the first spiritualist publication in Britain, though it only ran to one edition. The Haydens remained for a year in England, and returned to America at the end of 1853. Maria retained an active interest all things psychic even after becoming a doctor. She was noted for her clairvoyant abilities, as well as her aptitude for psychometry (diving insights by holding an object in her hands).

Although spiritualism may have failed to take root in London, it certainly found a home in Yorkshire when a Mr David Richmond, an American Shaker, brought the art of table-turning to the town of Keighley in the early 1850s. By 1854 "Tea and Table-Turning" had become an indispensable social pastime in the north of England, as the movement rapidly spread to neighbouring county of Lancashire. Funded by his Yorkshire contact, Mr David Weatherhead, at whose home he had first demonstrated table-turning, Richmond set up The Yorkshire Spiritual Telegraph in 1855. It proved far more successful than William Hayden's effort as the ground had been better prepared. Spiritualism had finally gained a foothold in Britain, but via the non-commercial domestic route.

Next month: Guess who's coming to dinner?—the extraordinary life of medium Daniel Dunglas Home

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Image:

Queen Victoria, 1887

Photograph by AlexanderBassano (1829-1913)

Published on November 01, 2013 07:14

•

Tags:

d-d-home, daniel-dunglas-home, david-richmond, maria-hayden, mediums, mrs-hayden, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

October 1, 2013

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: changing attitudes to death during the American Civil War

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fourth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fourth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.Approximately 700,000 soldiers and civilians lost their lives in the American Civil War (1861-1864) and some 300,000 others were injured. That's more than a million people in total. Although spiritualism was already popular prior to 1861, the fact that so many families were touched by death during this period is clearly the reason why the number of spiritualist followers grew. So this month I'll be looking at one of the lesser contributing factors instead: how the use of a new technology not only changed the way that everybody perceived war, but, for the first time in human history, offered those who'd lost relatives a way to remember their loved ones in perpetuity.

They say that history is written by the victors. They forget to add that, since the dawn of civilization, history has been drawn, painted, carved and cast in bronze by them too. For millennia artists have strived to immortalize great, heroic battles on paper, metal, stone and canvas. Above you will see such a painting, The Battle of Antietam by Thure de Thulstrup, typical of how war was depicted in the mid-nineteenth century. Take a good look at it, because from the mid-1850's on, prints made by using a photographic process called wet-plate collodion radically altered how we saw war.

The wet-plate collodion process, which was first introduced in 1851, was the brainchild of a man named Frederick Scott Archer. It had some distinct advantages over its two major competitors. Unlike daguerreotypes, which were one-off originals, collodion plates were negatives that could be printed countless times; unlike calotypes (also known as Talbotypes) whose negatives were made of paper, the glass plates of the collodion process gave sharp prints with an extraordinary tonal range that were rivalled only by daguerreotypes. But it also had one major disadvantage. The plates had to be coated in an emulsion and sensitized in a darkroom, exposed in a camera, then developed in the darkroom before the jellied emulsion dried—all in a matter of ten minutes. While this might seem to make it a strange choice for the documenting of wars, the truth is it was the only choice: daguerreotypes could not be printed, and calotypes were only capable of producing flat, sketch-like images.

Even so, it required a great deal of ingenuity, dedication and money to go and work on the battlefield, as each photographer needed a travelling darkroom in which to prepare and develop their plates. The one you see here dates from 1855. It belonged to the English photographer Roger Fenton, who used it in the Crimean War. The man seated in the driver's seat is Marcus Sparling, Fenton's assistant. Although from its inception the wet-plate process was used to record a number of wars, it wasn't until 1861 that it was used in a thoroughly planned and organised way. Mathew Brady, a New York photographer of some standing (it is his portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln in the previous post), came up with the idea of founding a company dedicated to documenting the American Civil War. He received Lincoln's blessing in 1861 on the proviso that he finance the project himself.

Brady employed 23 men, each of whom he equipped at enormous expense with a travelling darkroom. He spent approximately $100,000 on making some 10,000 plates, all of them bearing his name though few were actually taken by the man himself. His first collection of prints, entitled "The Dead of Antietam", was exhibited at his New York gallery in the October of 1862. The effect on the American public could not have been more startling. Where Roger Fenton had deliberately shied away from photographing dead bodies, Brady's employees did not. The dead, in fact, made excellent subjects, as exposure times for this period were upwards of several seconds, which ruled out the possibility of capturing live combat. The grim realities of death that were barely touched upon in painted scenes such as the one that heads this post could no longer be ignored.

While this caused a massive shift in the public's consciousness and understanding of war, it is probably the carte-de-visite photograph, the wet-plate's smaller, humbler cousin, that contributed more to the spurring on of spiritualism during this period. Cartes-de-visite were made on the same glass plates, but with a special camera that had eight separate lenses, each of which could be uncovered singly to give the sitter eight different poses, or uncovered collectively to give eight practically identical versions of the same pose. Once printed, the photos were cut up and pasted on to sturdy backing-cards, to be sent home to sweethearts, family and friends. As unimaginable as it may seem, this is the first war where ordinary enlisted soldiers were able do such a thing. Prior to this, having a likeness made before going off to die in battle (and remember, as photography was in its infancy, we're talking about drawings or paintings) was beyond the pocket of most.

When the war ended in 1864, the U.S. government declined to buy Brady's extensive collection of photographs, as he had hoped they would. The public, who had had their fill of death, had grown weary of his images. He was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy. Although Congress granted him $25,000 in 1875, for the rest of his life he remained in debt and died penniless in the charity ward of a New York hospital in 1896.