Michael Gallagher's Blog, page 4

October 1, 2017

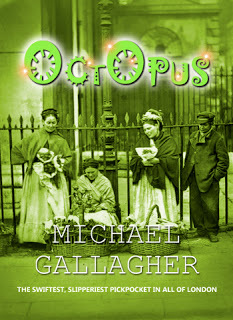

October 2017: Chapter the First

Having embraced your choice of narrative voice, you crank a pristine sheet of A4 into your old Remmington (or, if you’re like me, you open up a new Open Office or Word document), and you clack away at the keys until you have the heading “CHAPTER ONE” staring at you from the top of what is otherwise a blank sheet of paper or an empty screen. How many fledgling novels ended their lives here, I wonder, strangled at birth by that vast expanse of white? Where to start?—that is the question, and it’s a biggie.

Having embraced your choice of narrative voice, you crank a pristine sheet of A4 into your old Remmington (or, if you’re like me, you open up a new Open Office or Word document), and you clack away at the keys until you have the heading “CHAPTER ONE” staring at you from the top of what is otherwise a blank sheet of paper or an empty screen. How many fledgling novels ended their lives here, I wonder, strangled at birth by that vast expanse of white? Where to start?—that is the question, and it’s a biggie.First chapters are unique in that they have to do a number of jobs that subsequent chapters do not—so many in fact that, even if you do have some of your cast picked out and a rough idea for your story, the prospect can still be daunting. First chapters need to set the tone of the novel, introduce characters, and also get the ball rolling. My advice: before you even put pen to paper, get inside your characters’ heads and experience the world as they see it.

It may sound obvious, but whether you’re writing in the first-person or the third, your initial task is to establish who your narrator is or whose point of view you are writing from. The way they look, speak, and think is important—they are, after all, the person who is telling or witnessing the story for you. In addition to the narrator, it’s likely you’ll need to establish some of your other characters as well. Again, it may sound obvious, but it’s an idea to make them not just distinct from each other as possible but distinctive in themselves. Think of the number of times you’ve come across a character mentioned in a book and found yourself wondering who on earth they are. You needn’t go into great detail, but some basic information will be necessary. You can always develop various features as the book progresses, but bear in mind that you don’t want to mention at some later stage any key aspect that requires your readers to radically readjust the mental image they’ve already built up. The Crimes & Thrillers reading group I attend recently read a novel where on the second-to-last page we learned that the male protagonist had platinum blond hair. Bang went my image of him—and with it any further willingness to suspend my disbelief! So how much information is required? Let’s take a look at the start of the first chapter of Octopus. The narrator in this case is Octavius Guy, who is also known as Gooseberry:

THE DOOR TO MR Bruff’s office opened and out stepped the first of his two new clients: Mr Hector Willoughby, a tall, soberly-dressed gentleman of northern extraction in his early thirties. He’d recently returned from South America, where he’d managed to acquire certain “exclusive mineral rights”—whatever they were! Best not to ask, I always think…they might try to tell you! Mr Joseph Peacock, also in his thirties (but with a noticeably more flamboyant dress sense), stepped out next. He had just inherited his father’s estates in the south of England; all he was waiting on now was something they call “probate”—whatever that might be! Again, best not to ask.

To build his refinery in South America, Mr Willoughby needed Peacock’s money. To increase the already large fortune that was coming his way, Mr Peacock needed Willoughby’s minerals. Though the pair had only reached what one might call “the early wooing stage”, they required a presiding minister if this marriage was to work: a solicitor, to wit; a post that Mr Bruff was surely born to.

‘George!’ cried my employer, as he stuck his head round the door. It was the leaner, trimmer, older of the two Georges who sprang to his feet. Five months in, the reducing diet that Mr Bruff had put him on was working like a charm. So far he’d managed to shed nearly three stone. The same could not be said of the younger George, I might point out. Several pounds heavier and as round as a pudding, he was currently slumped on the bench beside me, snoring his head off for all to see.

Furtive dinnertime forays to his forbidden chophouse would have been my guess, not that my employer had ever asked me to look into it. Still, in the unlikely event that he did, as Mr Bruff’s newly-appointed chief investigator, it was always useful to have a working theory up my sleeve.

Chief investigator, eh? Or, to be more precise, chief and only investigator. But even so! It was definitely a step in the right direction. My one regret was that, although this promotion came with an increase in wages, it sadly didn’t come with an office. Hence here I sat beside the younger George, still relegated to the corridor bench.

Not a lot is going on yet, which is fine. It gives the reader space to take in their new surroundings, meet the narrator and (in this case) five of the characters, and to start to piece together how they all relate to each other. We learn of some of the events that have taken place since the close of the previous book, but we still don’t know Gooseberry’s age, or, apart from coveting a bit of office space, what his passions and inclinations might be. Some of these things, in a round about way, get fed into a later passage where Mr Bruff is quizzing him about his knowledge of Sadler’s Wells Theatre:

‘Well, they put on plays there, sir. I hear they’re currently reviving The Duchess of Malfi.’

I knew this because I’d read a review of said play that claimed it was one of the most bloodthirsty ever written. Apparently everybody’s dead by the curtain-fall. I’d been longing to see this alluring production for myself, but the question was how I might fund this; my per diem for daily expenses had been reduced to a measly shilling, of which I was obliged to account for every penny. Blast Mr Crabbit and his damnable receipts!

‘It stars a Miss Isabella Prynn in the role of the duchess,’ I continued, purposely skirting around the play’s rather bloodthirsty nature; it was bound to offend Mr Bruff’s quaint notions of what were and what were not suitable topics for discussion where a fourteen-year-old boy was concerned. ‘You may well have heard of her, sir. I believe she’s quite famous.’

Very, if the article I had read was anything to go by. As I was rapidly running out of things to say, I gave a discreet cough and came straight to the point.

‘Mr Bruff, wouldn’t it be easier if you just told me what it is you wish to know?’

Mr Bruff opened his eyes and blinked. I watched the tip of his tongue striving to moisten his lower lip as the seconds, if not minutes, ticked by.

‘Is it…safe?’ he enquired at last.

Gooseberry’s character has been plumped out a little, and two further characters have received a mention, readying us for their appearance later on. But we have yet to arrive at the inciting incident—that fateful decision or act that sets in train all future events—another thing that first chapters are apt include, often at the chapter’s climax. It can be something quite little, such as somebody writing someone a letter, or a detective agreeing to take on a new client, or, as in the case of Octopus, Gooseberry’s offer to accompany Mr Bruff to that evening’s performance. In the same passage we also find out about our protagonist’s physical stature and are brought fully up to date with what has been happening with him since the last book:

‘Oh, dash it all, I’ve read the reports in the papers! The thuggery that goes on outside its walls! The public displays of drunkenness when you venture inside the theatre! The building’s in such an awfully remote spot, I can’t help worrying that, if I attend, I shall end up being set upon by thieves!’

‘Are you to attend, sir?’

Mr Bruff nodded miserably. ‘Peacock’s been going on about it for days, and Willoughby needs the man’s money so badly, he’s not only reserved them a box, he’s jolly well gone and fixed it for him to meet the entire cast! So when they asked me to accompany them, I could hardly say no, now, could I? I had no wish to appear faint of heart.’

I should like to go on record as saying that Mr Bruff is not usually faint of heart, nor does he put much faith in what he reads in the papers. He’s far too level-headed for that. Clearly something had put the wind up him, but what?

‘When, sir?’ I asked.

My employer sighed. ‘Tonight.’

A truly inspired idea occurred to me. ‘What if I were to come with you, sir? I’d see to it that no harm befell you.’

Mr Bruff regarded me with a sceptical eye. ‘How?’ he asked, rather bluntly. ‘If a big, burly mugger came at us with a knife, how could a tiny lad like you hope to defend yourself?’

‘Before you were kind enough to employ me, sir, and rehabilitate me of my iniquitous ways, I was a well-respected and—dare I say it? revered—member of the criminal fraternity. No one would harm a former brother-at-arms, sir. You would be perfectly safe with me.’

Safer than he might imagine, for I was now in charge of these very same criminals. Having publicly fought their leader and won, the title of kingpin had fallen to me. By the rules of our time-honoured code, I was the person they now answered to.

This all works fine if you are introducing your characters gradually. But what happens when you have a large cast that needs to be introduced right from the get-go? In a future post I’ll be reflecting on writing crowd scenes, the spectre that haunts many an aspiring writer’s waking nightmare.

Happy reading!

Michael

Find me on my website, where you’ll discover regular special offers on all my novels

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on October 01, 2017 06:12

•

Tags:

first-chapters, starting-a-novel

September 1, 2017

September 2017: Hearing voices

After writing five novels all in the first person (or six if you include Gooseberry’s next outing which is coming on apace) I’m considering stepping out of my comfort zone to try a different narrative voice. I have a title; I have a tentative cover that needs a bit of tweaking. I have a time and place and setting: a small township on the shores of Lake Taupo in the North Island of New Zealand, one year after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. At this point the children of British immigrants still think of Britain as “Home”—whether or not they’ve ever seen it, or are ever likely to see it again. I have a cast of characters, some of the plot, and now all I need is narrative voice.

After writing five novels all in the first person (or six if you include Gooseberry’s next outing which is coming on apace) I’m considering stepping out of my comfort zone to try a different narrative voice. I have a title; I have a tentative cover that needs a bit of tweaking. I have a time and place and setting: a small township on the shores of Lake Taupo in the North Island of New Zealand, one year after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. At this point the children of British immigrants still think of Britain as “Home”—whether or not they’ve ever seen it, or are ever likely to see it again. I have a cast of characters, some of the plot, and now all I need is narrative voice.You may be wondering what a narrative voice is, and why it matters. At the simplest level, it’s about who’s telling the story. With the first-person, it’s your character who’s doing the narrating, and everything comes from her or his point of view, as in: “I was banging away at the keyboard, treating it like an old-fashioned typewriter, when suddenly there came a knock at the door. The woman who stood there eyed me sullenly, almost as if challenging me to read what was on her mind. ‘Change a twenty for two tens?’ she eventually asked, holding out a crisp, new note.”

If you’ve ever read a good first-person, you’ll know there’s no better way of getting to know the narrator’s character. You get to see the world as they see it. You are literally inside their mind. The challenge for the writer is that you have only one single voice carry an entire novel. The narrator cannot know what anyone else is thinking, and ways must be found for them to be present at every significant event—not always an easy task! A slight spin on this straight-out first-person is to have two narrators, each taking turns—great for thrillers where you get to see inside the mind of the detective and the killer alternately.

In the third-person, it’s you, the writer, who’s narrating—literally telling a story—so you’re no longer tied to just one person’s experiences or thoughts. You can have two or more points of view. For example: “Michael was banging away at his keyboard, treating it like an old-fashioned typewriter, when suddenly there came a knock at his door. The woman who stood there eyed him sullenly, making him feel nervous. So this is what a writer looks like, she thought to herself, disappointed by his shabby appearance and ungainly manner. ‘Change a twenty for two tens?’ she asked a trifle reluctantly, holding out a crisp, new note.” See? The world suddenly opens up to you!

There are still rules to abide by if you expect it to work. The fewer points of view there are, the more immersive the experience will be. Each different POV should be separated where it changes—at least by a sentence and preferably by a paragraph, if not by an entire section of a chapter. For example, “So this is what a writer looks like” would function better as a new paragraph. In addition to signalling who is speaking, you also need to signal whose point of view it has changed to. Consider: with “‘Change a twenty for two tens?’ she asked, though she was reluctant to,” we’re still seeing it from the woman’s POV. Were it to read, “‘Change a twenty for two tens?’ she asked, though it seemed to him she was reluctant to,” then we’ve reverted to Michael’s POV (and once again this deserves a new paragraph to demonstrate the change). Get this even a little bit wrong, and your readers will puzzle over your mistake, often sensing there’s something wrong without being able to pinpoint why.

I have seen the author Lionel Shriver argue the case for a second-person narrator, as in: “You were banging away at your keyboard, treating it like an old-fashioned typewriter, when suddenly there came a knock at your door.” I believe she used it in We Need to Talk About Kevin, but, as I haven’t read it, please don’t quote me on that. Myself, I’m not convinced. You are not the one telling the story. It’s being told (not exactly to you, but at you) by a third person, in what could easily turn into a very blaming sort of way.

Ruling that voice out, it leaves me with the choice of dividing the narration between two first-person narrators or branching out into the liberating (and, for me, somewhat terrifying) third-person narration. Perhaps I should never have let myself get so comfortable with the first-person narrative in the first place!

Happy reading!

Michael

Find me on my website, where you’ll discover regular special offers on all my novels

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on September 01, 2017 06:29

August 1, 2017

August 2017: Novels that feature recipes

At the back of

Big Bona Ogles, Boy!

, Gooseberry’s most recent case, you will find, of all things, a recipe for Funeral Biscuits. It reads: “Take twenty-four eggs, three pounds of flour, and three pounds of lump sugar grated, which will make forty-eight finger biscuits for a funeral.” If, like me, it surprises you that there are no instructions given as to what to do with these ingredients—let alone any guide as to how to go about cooking them—then let me quickly point out that, unlike the recipes presented in his previous adventures (which are my own), these are all genuine Victorian ones taken from Everybody’s Confectionary Book (and, no, I know that’s not the correct English spelling of the word confectionery). “This work,” its preface boldly claims, “will be found of beneficial advantage, not only to Confectioners, but also to Ladies, Housekeepers, &c, and particularly to such as have not a perfect knowledge of this useful art, and by which any person may, with ease and advantage, begin the practice of a Confectioners.” Quite. Though just how the recipe for Funeral Biscuits will aid them in the pursuit of this is anybody’s guess. For any cooks who may be reading, each so-called finger biscuit contains a quarter cup of flour, two tablespoons of sugar, and half an egg, so I’m guessing they’re some kind of (fairly large) shortcake.

At the back of

Big Bona Ogles, Boy!

, Gooseberry’s most recent case, you will find, of all things, a recipe for Funeral Biscuits. It reads: “Take twenty-four eggs, three pounds of flour, and three pounds of lump sugar grated, which will make forty-eight finger biscuits for a funeral.” If, like me, it surprises you that there are no instructions given as to what to do with these ingredients—let alone any guide as to how to go about cooking them—then let me quickly point out that, unlike the recipes presented in his previous adventures (which are my own), these are all genuine Victorian ones taken from Everybody’s Confectionary Book (and, no, I know that’s not the correct English spelling of the word confectionery). “This work,” its preface boldly claims, “will be found of beneficial advantage, not only to Confectioners, but also to Ladies, Housekeepers, &c, and particularly to such as have not a perfect knowledge of this useful art, and by which any person may, with ease and advantage, begin the practice of a Confectioners.” Quite. Though just how the recipe for Funeral Biscuits will aid them in the pursuit of this is anybody’s guess. For any cooks who may be reading, each so-called finger biscuit contains a quarter cup of flour, two tablespoons of sugar, and half an egg, so I’m guessing they’re some kind of (fairly large) shortcake.The first novel I ever came to that listed recipes at the back was Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistlestop Cafe. I loved the book when I first read it. Flagg really managed to nail the time and place, and the story she wove around those loveable characters had me begging to buy into it. As for the recipes, I was so delighted to see them there, I tried some. The fried chicken in milk gravy was a little rich for my liking, and my fried green tomatoes (made with my own home-grown tomatoes) disappointingly tasteless, but then I had no bacon grease in which to cook them. Never mind; it’s the thought that counts, and Fannie Flagg’s generosity of spirit certainly wins the day.

Rather than being relegated to the back of the book, the recipes in Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate are interspersed throughout, and as such become integral to the plot. They range from being totally impractical in this day and age (“100 cashew nuts; a quarter of a kilo of almonds; a quarter of a kilo of walnuts: begin shelling the nuts several days in advance, for this is a big job to which many hours must be devoted”) to the downright hilarious (the effect of Tita’s tears when added to the icing on Rosaura’s Wedding Cake). A good introduction to magic realism for those who have yet to experience the wondrous possibilities of the genre.

A kind of magic features too in Anthony Capella’s The Food of Love, a modern-day Cyrano de Bergerac-type story of a young Italian man named Bruno who loves to cook. The novel is structured after an Italian meal, with antipasto, primo, secondo, insalata, and dolci signalling the acts. The ricette—receipts or recipes—are to be found at the back, charmingly couched in a series of emails that provide the story’s denouement. As in Like Water for Chocolate, there’s a great take on oxtail, and a ragù bolognese that may make you laugh!

There are many, many books, such as Andrea Camilleri’s Inspector Montalbano mysteries, that will make your mouth water without divulging any culinary secrets, but there’s one that may deserve your serious attention. It’s Kiran Desai’s The Inheritance of Loss. All her characters (and their changes of circumstance) seem to be defined by what they eat, what they dream of eating, how they eat it, and what they actually cook—if in fact they cook at all. The judge dreams of cake and scones, macaroons and cheese straws but gets biscuits that look and taste like cardboard. The Afghan princesses only eat chicken. The cook claims he can make: “Bananafritterpineapplefritterapplefritter…” etc., but has none of the ingredients for these desserts. His (vegetarian) son Biju grills beefsteaks in America until he finds employment at the (Hindu) Ghandi Cafe. Be warned—it can be quite tough going!

Tough-going, but worth every minute of it, is Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance This is the book I cherish above all others. The scale of the story is enormous, detailing not just the lives of the four main characters who come from very different backgrounds and different parts of India, but their parents’ lives as well. In the whole epic tale you will find only one recipe: for wadas (or vadai, a kind of Indian falafel made from urad dahl, onion, chilli, cumin, coriander leaf, mint, and coconut). It’s Rajaram’s recipe, and, in making it, the four of them manage to cement their friendship. As dark and deeply depressing as it is funny, I reread A Fine Balance every couple of years to remind myself how amazing good writing can be.

Happy reading!

Michael

Find me on my website, where you’ll discover regular special offers

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

July 1, 2017

July 2017: Penny dreadfuls—really as dreadful as they were painted?

Cloven Hoof, the Demon Buffalo! or the Border Vultures: One of the ghostly personages approached and addressed him, “Follow me to the Council Chamber, and hear your doom!”

Last year (before I retired from teaching to write full time) a colleague of mine mentioned a newspaper article he’d come across which he thought might interest me, for it concerned penny dreadfuls—those cheaply-produced Victorian serials for the masses, with their blood-red titles singing out against a yellow background, promising action and adventure aplenty. The article, which appeared in the Guardian at the end of April 2016, was by Kate Summerscale, author of The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or The Murder at Road Hill House—about the murderess Constance Kent—and The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer, her new book which in fact fuelled the article. She points out that, in the case of Robert and Nattie Coombes, who murdered their mother in 1895, the coroner’s jury made particular note of the cache of penny dreadfuls found in the boys’ back parlour. “We consider the Legislature should take some steps,” she quotes them as saying, “to put a stop to the inflammable and shocking literature that is sold, which in our opinion leads to many a dreadful crime being carried out.” The coroner agreed. She goes on to cite, amongst other things, the verdict in the case of a 12-year-old servant boy who hanged himself in 1892: “suicide during temporary insanity, induced by reading trashy novels.”

Trashy novels! But what exactly were these trashy novels? Take a look about at some of the gorgeous covers I’ve assembled on my website—courtesy of the British Library—and you may begin to see a pattern emerging. Each has a lavish illustration depicting a dramatic moment in the plot, often coloured-in with swathes of red, echoing the lurid font of the title. Nearly all bear a quote in the footer to tease and stir the imagination. My undoubted favourite is Cloven Hoof, the Demon Buffalo. I myself am not above a little (properly acknowledged) plagiarism, and I’d bet my bottom dollar that some version of this snippet makes its way into one of Gooseberry’s next adventures. I’m also intrigued by the prudent if dithering nature of the man leaving clues in Dark Dashwood, the Desperate. I too have had to ponder the mystery of why anyone in their right minds would need to leave clues—especially cryptic ones—to a treasure they’ve taken their time and trouble to conceal. Consider the logic of this for even a minute and, trust me, your mind will implode. Be that as it may, these serials are first and foremost tales of high adventure set in dangerous out-of-the way places where fortunes may be won or lost on the single throw of a dice. They’re fiction as escapism. And the authors of these trashy, seditious works, who were they exactly…?

If you’re an aficionado of the Victorian, especially Victorian Britain, your eye might well have been drawn to The Young Duke, by a certain Benjamin Disraeli. Could Britain’s twice-serving Prime Minister, beloved of Queen Victoria herself, really be responsible for this trash? Well, in a nutshell, yes! He is! It’s a reprint of a novel he wrote in his twenties—when he needed quick ready cash—before he’d even considered entering into politics. Much is made of Millennials whose online history will dog them throughout their later lives, but this is not a new phenomenon by any means. The Young Duke is but an early example. Priced at a staggering sixpence and tellingly lacking any quote from the text, this is what would-be criminal types would have learned from within its pages. It is the duke of the title who is soliloquising. I only hope those proto-malfeasants didn’t waste their hard-earned money:

“Am I a Whig or a Tory? I forget. As for the Tories, I admire antiquity, particularly a ruin; even the relics of the Temple of Intolerance have a charm. I think I am a Tory. But then the Whigs give such good dinners, and are the most amusing. I think I am a Whig; but then the Tories are so moral, and morality is my forte; I must be a Tory.”

For those who can be bothered to care, a Whig is a liberal member of the House (of Lords, in this case) and a Tory is their conservative opposition. Showing more promise by far is Death Trailer the Chief of Scouts, purportedly by the Honourable W. F. Cody, better known to us perhaps as Buffalo Bill. Unfortunately, it’s not actually by him. Buffalo Bill’s adventures were ghost-written by a succession of writers, starting with Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men by Ned Buntline, which began its serialization two days before Christmas in 1869. Buntline was the nom de plume of a man named Judson, a serial bankrupt who killed a man in a duel and was brought to trial for his murder, during the proceedings of which he was shot at and wounded by his victim’s brother. He escaped in the ensuing fracas, only to be captured by a lynch mob, and saved from being hanged by his friends.

Take a closer look at the covers and you’ll see that the majority cost tuppence—2d. (tuppence; two pennies)—roughly equivalent today to about UK£1.50 (or US$1.35 now that we’re lumbered with Brexit). That’s approximately one-sixth of the cost of, say, All the Year Round, the magazine in which Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone was first serialized, which was aimed at a moneyed audience. Penny dreadfuls, by contrast, targeted the burgeoning newly-literate working-class youth market. What may not be so obvious these days (and hurrah for that!) is that they were actually meant for boys. In retrospect it is easy to see the establishment’s fear of penny dreadfuls as being something of a class issue. While it was perfectly acceptable for gentleman of standing to pay their shilling and weep openly over the death of Little Nell, it was scandalous for working- and middle-class boys to stump up tuppence to learn the fate of Cloven Hoof in the mysterious council chamber.

Yet, for some readers, their influence proved to be too great a pull. Kate Summersecale cites a number of instances where pairs of boys ran away from home, often with ambitious but totally naïve plans based on the tales they had read: “Steal the money; go to the station, and get to Glasgow. Get boat for America. On arrival there, go to the Black Hills and dig for gold, build huts, and kill buffalo; live there and make a fortune.” But suicide induced by reading trashy novels? As much as I pity the poor boy who felt his only option was to hang himself, I think not.

Such cases inevitably led to a backlash from within the publishing world itself. The Half-penny Marvel of 1893 had this to say of its fellow papers:

“It is almost a daily occurrence with magistrates to have before them boys who, having read a number of ‘dreadfuls’, followed the examples set forth in such publications, robbed their employers, bought revolvers with the proceeds, and finished by running away from home, and installing themselves in the back streets as ‘highwaymen’. This and many other evils the ‘penny dreadful’ is responsible for. It makes thieves of the coming generation, and so helps fill our gaols.”

Before long The Half-penny Marvel was printing its own penny dreadful stories (surprise, surprise), and its publisher, Alfred Harmsworth, cornered the market with a string of similar half-price publications.

These persisted as late as the 1960s when, as a boy growing up in New Zealand, I too was entranced by imported British magazines that serialized out-of-copyright tales of highwaymen written some 130 years before. I remember the anticipation I felt while waiting for the next week’s instalment. Summerscale quotes Robert Louis Stevenson as saying of such stories, “I do not know that I ever enjoyed reading more.” I heartily concur.

Happy reading!

Michael

Find me on my website, where you’ll also find regular special offers

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on July 01, 2017 06:28

•

Tags:

penny-dreadful, victorian

June 21, 2017

Fancy a great read to celebrate the summer solstice?

Buy any of my novels between Wednesday June 21st and Saturday June 24th 2017, and you will get them for free. Find the links and codes you will need on my website.

Happy solstice! Happy reading!

Published on June 21, 2017 06:31

•

Tags:

free-e-books, solstice

June 1, 2017

June 2017: What is it that defines a cosy mystery?

What image do you conjure up in your head when you hear the term “cosy mystery”? A tea tray set before a blazing log fire in a library where the occupant sits lifeless? An idyllic rural pastoral scene punctured only by the bullet hole through the forehead of the local country squire? If you’re anything like me the first name that pops to mind will be Miss Marple’s—a small backwater village in rural, genteel England, where the curtains swish with every passer-by and murder lurks just along the lane. Which brings me neatly to the first point that I feel most cosy mysteries share in common: they are invariably set in some version of the past, even those that are meant to be contemporary. Scratch the surface of Agatha Raisin’s Cotswold village of Carsely, Hamish Macbeth’s remote Lochdubh, or Mma Ramotswe’s bustling Gabarone, and you’ll find yourself not so very far from rustic 1930s St Mary Mead. Why should this be? Well, as Jane Marple remarks to her nephew Raymond in The Thirteen Problems:

What image do you conjure up in your head when you hear the term “cosy mystery”? A tea tray set before a blazing log fire in a library where the occupant sits lifeless? An idyllic rural pastoral scene punctured only by the bullet hole through the forehead of the local country squire? If you’re anything like me the first name that pops to mind will be Miss Marple’s—a small backwater village in rural, genteel England, where the curtains swish with every passer-by and murder lurks just along the lane. Which brings me neatly to the first point that I feel most cosy mysteries share in common: they are invariably set in some version of the past, even those that are meant to be contemporary. Scratch the surface of Agatha Raisin’s Cotswold village of Carsely, Hamish Macbeth’s remote Lochdubh, or Mma Ramotswe’s bustling Gabarone, and you’ll find yourself not so very far from rustic 1930s St Mary Mead. Why should this be? Well, as Jane Marple remarks to her nephew Raymond in The Thirteen Problems:‘You think that because I have lived in this out-of-the-way spot all my life I am not likely to have had any very interesting experiences.’

‘God forbid that I should ever regard village life as peaceful and uneventful,’ said Raymond with fervour. ‘Not after the horrible revelations we have heard from you! The cosmopolitan world seems a mild and peaceful place compared to St Mary Mead.’

‘Well, my dear,’ said Miss Marple, ‘human nature is much the same everywhere, and, of course, one has opportunities of observing it at close quarters in a village.’

Like the redoubtable Miss Marple, detectives in cosy mysteries are almost always amateur sleuths. Think of Elizabeth Peters’s Amelia Peabody and Alan Bradley’s 11-year-old master poisoner Flavia de Luce. Possibly less familiar, but of equally amateur status and just as enjoyable, we have Colin Cotterill’s 1970s Laotian coroner Dr Siri Paiboun freshly dragged out of retirement, Frances Brody’s 1920s Yorkshire lass Kate Shackleton, a young war widow who’s game for anything, and Lindsey Davis’s swords & sandals informer (read “private investigator in Ancient Rome”) Marcus Didius Falco. Even the great Hercule Poirot has no official standing, despite his lifetime service to the Belgian police force.

There are one or two exceptions to this rule: M. C. Beaton’s Scottish bobby Hamish Macbeth is on active duty (of a sort), as is Andrea Camilleri’s food-loving Sicilian, Inspector Montalbano. So too is Georges Simenon’s Maigret, if you include Maigret in this genre. But none of these series could be described as “police procedural”, and the officers in question are not beyond working outside official channels—indeed they often must. All share a further factor with practically every other cosy mystery—the sleuth, be they amateur or otherwise, has companions.

Companions. Whether it’s Amelia Peabody’s Emerson howling curses at her as he strides manfully off across the sands, or Precious’s be-spectacled assistant Mma Makutsi sitting at her typewriter and contemplating yet again the ninety-seven per cent score she received for her diploma, it seems to me the detective’s companions are key to distinguishing the cosy from every other type of mystery. A cosy is likely to be just as much about the companions as any murder that may (or may not) occur. Indeed, from The Kalahari Typing School for Men onwards Grace Makutsi nearly always steals the limelight, bringing a great deal of pathos to the proceedings as she does so. In Colin Cotterill’s Disco for the Departed, Siri’s young morgue assistant, Mr Geung—who happens to have Downs Syndrome—is abducted and whisked far from home, and in many ways (for me at least) the book is about his singular determination to make it back. Even animals can feature: Bastet the cat in The Curse of the Pharaohs, Saloop the dog who saves the doctor’s life in The Coroner’s Lunch, Nux the stray, who attaches herself to Falco in Time to Depart, Hamish Macbeth’s happy-go-lucky Lugs who gambols playfully with wildcat Sonsie in the heather. Human or furry, the role of the companion is not only to move the plot along (or to slow it down if need be), but also to bring humour to the story.

Humour: it may not be essential to the cosy mystery, but the majority have it in spades. Whether it’s 11-year-old Flavia rejecting method after method to arrive at the perfect way of poisoning her hosts, or Mma Ramotswe (slight spoiler here) insisting on still calling her husband Mr J. L. B. Matekoni after their marriage (as in, ‘Wake up Mr J. L. B. Matekoni! Wake up Mr J. L. B. Matekoni! There is a fire!’), a wry and comic insight into human nature is guaranteed to find fertile soil in this genre. Eagle-eyed readers will, I hope, forgive the fact that I made that last quote up myself; it is, however, entirely consistent with the series, as I’m sure other readers will attest.

So; have I managed to sum up the elements that make up a cosy mystery? Have I left anything out? I’d love to know your thoughts. Why not post a comment below? And if, like me, you are a fan of Crimes & Thrillers, do consider joining me at the Canada Water Crime & Thrillers Book Club on Facebook. We are a small but friendly and enthusiastic reading group who read widely—from classics by the likes of Wilkie Collins to more recent novels such as The Girl on the Train—but most of us have a soft spot for a good cosy mystery. We generally meet up at 2 pm at Canada Water Library (in Rotherhithe, London) on the fourth Thursday of every month, but if you live elsewhere in this big, wide world and fancy following what we read, you are most welcome to join us online. Maybe you’ve read and loved our current book? Then do share your thoughts by posting on the appropriate post; we’ll try to read through them at the meeting (though sadly the wifi can be a bit dodgy).

Happy reading!

Michael

Find me on my website

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on June 01, 2017 06:29

•

Tags:

cosy-mysteries, cozy-mysteries

May 5, 2017

The Quibbling Cleric: Prologue, part 5 #MysteryWeek

‘WE SHOULD CHECK THE church for more clues while we still have the chance,’ I suggested, eager to press on from my embarrassing little oversight. ‘You take that side; I’ll take this.’

For the next few minutes we inched our way through the interior, starting at the altar and working down the nave, and thence into the aisles along either wall. Though Gothic in style, it was a new church, and everything in it—bar the fresh pool of vomit made by the young Mr Badger—was spick and span and spotlessly clean, just as I expected it to be. From the bible on the lectern—open, I observed, at the Book of Isaiah—to the rows of hardwood pews, there was hardly a scuff mark or smear to be seen.

‘Anything, George?’ I asked, as we met back up by the cleric’s body.

‘Nah. You?’

‘An impression, George, and quite an interesting one, at that. The blood…or the lack of it, to be precise. His face was beaten to a pulp, yet there isn’t nearly as much blood as I would expect there to be.’

George glanced down at the floor and frowned. ‘You’re right. There should be more. A lot more. What can it mean, Octavius?’

The sound of rapidly approaching footsteps from outside the church put paid to any immediate speculation; the stalwart men of N-Division had arrived.

‘Don’t think I’ve forgotten that note to Annie,’ George warned me, as they blundered noisily in through the entrance. ‘She’s my little sister, see?’ He turned his head and fixed me with a stubborn, bovine stare.

Unfortunately for me, I saw only too well.

Here endeth the Prologue

Keep your eyes peeled for Oh, No, Octavius!: Send for Octavius Guy #4 and join Gooseberry and his ragtag bunch of friends when they investigate “The Case of the Quibbling Cleric”

Want more?

The Victorian boy detective’s other fiendishly puzzling cases are available now

Love mysteries? Love #MysteryWeek

I hope you’ve enjoyed this little peek at what’s coming next for Gooseberry and George. I’ve certainly enjoyed sharing it. A huge thank you to Goodreads for hosting #MysteryWeek; I do so hope it becomes an annual event. Remember, there are twenty free copies of Octopus: Send for Octavius Guy #2 (Octavius Guy and the Case of the Throttled Tragedienne) to be given away throughout May. You’ll find the coupon code and link you’ll need at the bottom of my monthly post on my website. If you miss out, you can still get 50% off the list price of Send for Octavius Guy #3. Just scroll down the page.

#MysteryWeek ends this Sunday, so there is still time to ask me questions on “Ask the Author”. Does Charley’s luck ever change? How did Gooseberry’s mother die? Does George come to terms with Annie and Octavius’s relationship? Hurry, though; the crystal ball grows dim. Happy reading to you all!

Michael

Find me on my website

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on May 05, 2017 06:12

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, mysteryweek, octavius, octopus, send-for-octavius-guy

May 4, 2017

The Quibbling Cleric: Prologue, part 4 #MysteryWeek

‘HAS THE CLERGYMAN ANYTHING more to tell us?’ I asked, making a mental note to have another crack at the cypher once the police had been and gone.

George scratched his head. ‘Well, his muscles are stiff.’

‘Fully stiff?’

‘They don’t come no stiffer.’

I tried to recall what I had read about this, which proved to be a great deal easier than actually applying it. ‘Rigidity starts to take hold approximately two hours after death, and reaches its peak some eight to twelve hours later. The muscles can remain fully stiff for a further eighteen. But…’

‘But?’

‘Well, it was a rather balmy night last night, which would speed up the process a little. The hour is now almost seven by my reckoning. Which means…’

‘What?’

‘Well, the odious Reverend Burr must have met his end during the thirty hours preceding five o’clock this morning.’

George did not look impressed. ‘We both saw him late yesterday afternoon,’ he pointed out, ‘going about his business as usual. It had to have happened sometime after that.’

Ho hum. Estimating time of death by observing the body’s rigours is an imprecise science at best.

‘We should check the church for more clues while we still have the chance,’ I suggested, eager to press on from my embarrassing little oversight. ‘You take that side; I’ll take this.’

Just one or two more clues (of a sort) to come when this sneak preview concludes tomorrow exclusively here on Goodreads!

Love mysteries? Love #MysteryWeek

Don’t forget, all this week you can ask me any question—past or future—about the series’ characters on the Goodreads’ “Ask the Author” feature. What becomes of Gooseberry’s younger brother Julius when he grows up? Does Prince Albert put in another appearance? Did Hector Willoughby ever make it to the gold fields? Act now, friend! The crystal ball is growing dimmer.

There are twenty free copies of Octopus: Send for Octavius Guy #2 to be given away throughout May. You’ll find the coupon code and link you’ll need at the bottom of my monthly post on my website. Just scroll down! Happy reading.

Michael

Find me on my website

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on May 04, 2017 06:13

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, mysteryweek, octavius, octopus, send-for-octavius-guy

May 3, 2017

The Quibbling Cleric: Prologue, part 3 #MysteryWeek

‘WHAT’S IT SAY?’ I asked.

‘Your guess is as good as mine.’ He shrugged and handed the fragment to me. There was writing of a sort on it—just one line—though it appeared to be some form of code:

etomnialignaregionisplaudentmanu

I scanned my eyes back and forth along the letters. The script indeed looked ancient, with any rounded parts not rendered as circular, but formed instead with a flat-cut nib employing short, oblique strokes of the pen. No matter how I tried to group them, the only words I could make from it were “to” or “Tom”, “I align”, “a region is”, and then either “laud”, “den” or “dent”. And “man”, of course, though, with its ensuing “u”, I presumed we were missing the -facture or -facturer that would most likely come next. A thousand pities that we had only this small portion of text, I reflected. Had we more, what grand truths might we have been able to discern?

George watched as I stowed the scrap inside my pocket.

‘Guy’s Seventh Rule of Detection?’ he queried, and I shot him a grin: Never allow good evidence to fall into the hands of the police.

Well, it’s not as if they would be needing it; if I couldn’t work out what the message meant, then they, poor souls, had no chance at all. Mr Peel’s finest are not exactly noted for their brains.

‘Has the clergyman anything more to tell us?’ I asked.

Any ideas or suggestions as to what it might mean? Feel free to share, especially if you know the answer! Trust me, it won’t be a spoiler

Continues tomorrow exclusively on Goodreads

Love mysteries? Love #MysteryWeek

Don’t forget, all this week you can ask me any question—past or future—about the series’ characters on Goodreads’ “Ask the Author”. Does Mr Smalley’s young assistant, the obsequious Perkins, ever make a return? Does Bertha discover the wonder of wigs—or should I say dolly, dolly riah? (Yes, she does, and she comes up with quite a unique way of wearing them, too!)

There are twenty free copies of Octopus: Send for Octavius Guy #2 (Octavius Guy and the Case of the Throttled Tragedienne) to be given away throughout May. You’ll find the coupon code and link you’ll need at the bottom of my monthly post on my website. Just scroll down! Happy reading.

Michael

Find me on my website

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on May 03, 2017 06:18

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, mysteryweek, octavius, octopus, send-for-octavius-guy

May 2, 2017

The Quibbling Cleric: Prologue, part 2 #MysteryWeek

‘I THINK HE’S DEAD,’ said George.

‘It would certainly seem it,’ I concurred. ‘See how the whole of his face is stove in? All that is left is a pulpy, bloody mess.’ It prompted in me a sudden memory.

When thou saidst, “Seek ye my face,” my heart said unto thee…

Thy face, Lord, will we seek.

Prophetic words indeed.

‘Hammer?’ enquired George, with a detached sense of professionalism I could only admire.

‘Yes, or some kind of mallet.’ I cocked my head to the side. ‘Such a frenzied attack! Someone was most determined that he should not survive it.’ Someone, presumably, who was frustrated with our efforts to date, and had resorted to a much quicker solution to their problem.

George sniffed. ‘Or maybe they didn’t want us to identify him,’ he posited.

It was certainly a suggestion, though not one that was borne out by the evidence. I scrutinized the man’s manner of dress: the fusty old frock-coat, the battered felt hat, the telltale gloves that encompassed his hands: white, inexpensive, and—most importantly—brand new. If anyone was trying to hide his identity, they’d made a deplorably bad job of it.

‘I was just saying,’ grumbled George when I pointed this out. ‘If the murderer didn’t want us to identify him, what better way than to bash in his face?’ He crouched down to take a closer look. ‘Poor bloke was trying to defend himself,’ he observed. ‘See how he’s cowering? Arms and knees drawn up in front of him to ward off the blows, and look at how he’s got his fingers clenched. Here, what’s this?’

George leaned forward and fiddled with the Reverend Burr’s gloved right hand. With a forceful tug he prised away a torn scrap of parchment.

‘From some kind of paper or document,’ he opined. ‘Whatever it was, the murderer must have grabbed it off him once he was done for. Looks old,’ he said, as he held it up to the light.

‘What’s it say?’ I asked.

Find out tomorrow exclusively on Goodreads

Love mysteries? Love #MysteryWeek

Don’t forget, all this week you can ask me any question—past or future—about the series’ characters on Goodreads’ “Ask the Author”. How are George and his new wife getting along? Is it true that Bertha murdered her own father? Whatever you wish to know about your favourite character, now is the time to ask!

There are twenty free copies of Octopus: Send for Octavius Guy #2 to be given away throughout May. You’ll find the coupon code and link you’ll need at the bottom of my monthly post on my website. Just scroll down! Happy reading.

Michael

Find me on my website

on Facebook

and @seventh7rainbow

Published on May 02, 2017 06:22

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, mysteryweek, octavius, octopus, send-for-octavius-guy