Michael Gallagher's Blog, page 8

October 24, 2014

Gooseberry: Chapter Seventeen

Though we had Mallard in custody, Josiah Hook—his underling—managed to escape. We could only surmise that he’d seen Sergeant Cuff rallying his men, realized what was about to go down, and immediately took flight. We had more pressing matters to deal with, however, for word arrived from the Bucket of Blood: Johnny was holed up in one of the upstairs rooms, firing his pistol at anyone who tried to enter. So far two men had been wounded.

Though we had Mallard in custody, Josiah Hook—his underling—managed to escape. We could only surmise that he’d seen Sergeant Cuff rallying his men, realized what was about to go down, and immediately took flight. We had more pressing matters to deal with, however, for word arrived from the Bucket of Blood: Johnny was holed up in one of the upstairs rooms, firing his pistol at anyone who tried to enter. So far two men had been wounded.To my great annoyance, Sergeant Cuff forbade me to come when he and his officers set off for the scene in their police wagon. Believe me, hauling yourself up on to the driver’s box is a hard enough task for someone of my height even when the vehicle’s stationary; when the horses are being whipped into a frenzy, as they were when the wagon pulled away, it’s a feat of pure gymnastics. It felt exhilarating, though. You should have seen the driver’s face when I suddenly appeared at his side!

Cornhill, Cheapside, Ludgate, Fleet Street, the wind whipped through my hair, for I hadn’t had a chance to change back into my own clothes, let alone grab my hat. Up Drury Lane and down Long Acre we flew, till the driver pulled the horses up short just shy of St. Martin’s Lane. I ducked down out of sight as Sergeant Cuff and his men alighted from the covered wagon at the back, then I lowered myself to the ground and took chase. I could hear the muffled sound of gunfire echoing through the streets, punctuating a man’s bellowing screams. The screams turned out to be from the pub’s landlord; blood gushing from a wound to his jaw, the great bear of a fellow was staggering round in circles outside his own establishment in his apron. Ignoring his distress, Cuff’s men charged at the doors. Needless to say I was hot on their heels.

Inside, too terrified to move, a handful of late-night patrons sat staring at the body of a man who was lying on the sawdust-covered floor by the foot of the stairs. I glanced at it in passing and was pleased to see that it wasn’t anyone I knew.

So far my presence had gone unnoticed. Even in the corridor at the top of the stairs, I managed to evade the sergeant’s vigilant gaze by falling in behind the stout, trusty officer at the back of the line. Almost immediately there came a rapid succession of shots that blew away yet another section of the door’s paneling. Everybody ducked.

“As far as we can tell, he’s in there alone, but he has more than two pistols at his disposal,” explained one of the men who’d been sent there originally. “Four, possibly five, I believe.”

“Then it will take him time to reload them,” remarked the sergeant. “We’ll storm the room after his next volley. Men, charge your weapons.”

Everyone set to work with their powder and pellets. Sure enough, before very long Johnny started firing again. I counted the blasts, just as every other man in that corridor did. One. Two. Three. A pause. Four. Was there a fifth pistol or not? The seconds ticked by.

Holding his hand up to restrain his men, Sergeant Cuff cried, “Ready men? Go!” He kicked open what remained of the door but, like everyone else, he held his ground. A fifth shot rang out, followed closely by a sixth, taking away two solid chunks of the door frame.

“Charge!”

We piled through the doorway amid a flurry of gun-fire, all of it our own. After the initial confusion, I saw that the room was empty.

“He’s gone,” said the sergeant, making a quick but careful search of the room.

I ran to the open window and looked down.

Sergeant Cuff joined me a second later, too late to see what I’d seen: the look of fury in Johnny’s eyes as he clambered to his feet and quickly limped away; a look of fury that was directed entirely at me.

“Well, what are you waiting for?” cried the sergeant to his men. “Get down there and hunt for him!”

Though they searched the neighboring streets and buildings for close on an hour, they found no sign of him. Johnny was gone.

The surprises of that Wednesday evening were not over for me yet, however. Back into my own clothes at last, I arrived home late at my lodgings only to find Julius and Bertha entertaining company. Seated with them at the table, braving the heat to cram small amounts of steaming potato into his mouth with his fingers, was the boy I had last seen in Twickenham posing as the Maharajah of Lahore. He was thinner, his face unwashed, his clothes disheveled, yet still a spark of devilishness managed to burn in his eyes.

“Your Highness,” I greeted him with a nod of the head, “ for I confess I know not what else to call you…”

“My name is really Sandeep,” he replied, in his rich, sing-song voice. “Sandeep Singh—though I’m no relation to His Highness,” he added, when he saw the puzzled look on my face. “All Sikh boys are given the name Singh. It’s our tradition. But most people call me Mutari, which in my language means Magpie, for there is no fleeter-of-foot, less likely to be caged pickpocket in all of Lahore.”

I had to stop myself from gasping at the boy’s out-and-out cheek. The impudence of the fellow; the audacity; the sheer brass neck! Personal vanities aside, the lad’s skills were no match for mine.

“How did you find me, Sandeep?”

“Well,” he said, laying the potato aside and settling in as if to recount a lengthy story, “when I overheard Treech plotting to destroy the daguerreotype by burning down your employer’s bank, I knew it was my duty to escape. So I made my way to London on foot, keeping to the quieter lanes and byways. The days were cold and the nights even colder. When the sun went down, I sought refuge in farmers’ barns. But the words I remembered you saying spurred me on, how you lived on the Caledonian Road, near where they are building a new railway terminus. It should not be too hard to find this place, I imagined, but each time I ask for directions, people notice the color of my skin and remark upon it, and I realize I am putting myself in danger. Aieee! And when I do eventually find this place, it turns out to be such a godless spot! I see drovers herding cattle to the slaughter by their dozens. Dozens! In spite of this I force myself to sit by the side of the road, and I wait and watch. And when, after many hours, I spy this young man here trudging his weary way homeward, I approach him, for it cannot be a matter of coincidence that he shares the same eyes as you, Gooseberry—or should I say Octavius?”

Julius beamed.

“When I explained how I knew you,” Sandeep continued, “your brother was kind enough to take me in and, as you can see, he and your good friend Bertha have been entertaining me lavishly by showing me their wonderful new photographic portraits and providing me with much needed sustenance.”

“Lad’s as skinny as a rake,” grunted Bertha. “Needs feedin’ up. Been tellin’ us about the plan to steal some whopper of a diamond, ’e has.”

“Yes,” said Sandeep, “my one consolation in this whole business is that I—and I alone—have foiled Mr. Treech’s plot. Without me he cannot hope to make the planned substitution.”

Hmm. What did I tell you? Sheer brass neck. “Actually, Sandeep, Treech is dead,” I enjoyed telling him. “His superior shot him, either out of rage or simply to tie up loose ends.”

The boy stared at me in alarm. “But the maharajah, he is safe?”

“I believe so, yes. One of the gang took him into hiding quite some time ago. As for the substitution, they found another way to do it.” I went on to relate the evening’s events, much to everyone’s delight—even Sandeep’s, to give him his due—though Bertha looked somewhat down-in-the-mouth when I revealed that not only had Josiah Hook—the man that he knew as the Client—flown the coop, but Johnny Knight was in the wind, too. “The question is,” I concluded, “where do we go from here?”

“Nowhere,” muttered Bertha despondently. “I can’t go bleedin’ nowhere till Johnny’s caught.”

“I have been thinking,” said Sandeep, “this your friend of yours, this Sergeant Cuff. Perhaps I should meet him and explain my side of the story.”

“You can take it from me, it don’t do no good to go blabbing your screech off to no law,” advised Bertha, as he poked one final log into the stove. “That’s wot comes from ruminatin’ ’bout things so late at night.”

“It really depends,” I said, “on whether or not you were ever a willing accomplice.”

“ A willing accomplice?” Sandeep looked horrified at the very suggestion. “Do you imagine for one moment that I wanted my face to be cut? Or that I wished any harm to come to the maharajah? The hopes of the whole Sikh nation rest with him.”

“Then why did you do it? Why did you go along with them?”

“I was given a choice between that and prison,” he said simply.

So much for the legendary Magpie, the fleetest-of-foot, least likely to be caged pickpocket in all of Lahore, I thought. Aloud I said, “All right, I’ll see what I can do to arrange a meeting.”

I noticed Julius nodding off in his chair so, after resolving the increasingly-cramped sleeping arrangements, we all bedded down for the night.

Given the happenings of the past two days, Thursday felt rather flat by comparison—apart from one small event, that is. I needed to consult Mr. James, Miss Penelope’s beau, as to how best to communicate to his brother that it was now safe for him and his guests—the maharajah and his guardian—to make their return. When I arrived at the Montagu Square house, it was Mr. Betteredge who answered the door. Having explained my business to him, I expected to be shown up to Mr. James’s room. Instead he stood there waiting and looking down at me expectantly.

A whole minute must have ticked by before he eventually asked, “May I take your hat, son?”

“My…hat?” I wasn’t sure I’d heard him correctly.

“Your hat,” he said. I swear on my life that I didn’t shed a single tear, yet I was so overwhelmed by the gesture that he quickly added, “Would the young master care to be shown to a room where he can compose himself?”

By two in the afternoon, I was leaning against a tree close to Hyde Park’s Cumberland Gate. That particular position afforded me an unobstructed view of the park bench under which James and Thomas left notes for each other. There was a note for Thomas there now that James had penned at my request. Though it was a chilly day, there was still a steady stream of people keen to take a breath of fresh air. As I watched, a man detached himself from the group that had just entered and sat himself down on the bench. His face hidden beneath a swaddling of scarves, he slowly glanced left and right, then casually reached under the bench. Locating the note I’d placed there, he opened it, read it, and looked up in surprise. I smiled and waved. For a minute I thought he might bolt.

“Please do not make me run after you, sir,” I begged him, as I approached. “What your brother says is true. Sir Humphrey Mallard is in custody. The plot to steal the diamond has failed.”

“And the boy standing by the tree is someone I can trust with my life?” he added skeptically, referring to the final paragraph on the sheet of paper.

“Yes, Mr. Thomas, you can. My name is Octavius, though most people call me Gooseberry. I’m here to see that you and those you protect get safely home.”

He took some convincing, I must say, but in the end he agreed to accompany me back to the Blakes’ house for a meeting with his brother.

Next I paid a visit to the good Sergeant Cuff, in the hope of learning his intentions regarding Thomas and Sandeep, as there was a distinct possibility that both might be viewed as co-conspirators in Mallard’s scheme. Disappointed, though not entirely surprised by the result, I found I had one more journey to make before taking a cab back to my lodgings. I needed to deliver a letter, one that I’d had the foresight to compose during my brief time at the Blakes’. I was going to miss traveling like this, I reflected, as the cab wended its way through the London streets; I’d become very used to this most expedient form of transport.

I arrived at work on Friday at the normal time, only to be taunted again by Mr. Grayling as I went to collect my final per diem and—by comparison—my rather paltry wages for the week. This time I was ready for him. When he started on about my eyes, I took a crumpled ball of paper from my pocket and tossed it on his desk. Mr. Grayling—or Mr. Christopher, as I’d decided to call him, for it could be said with a larger measure of insolence—blanched and fell silent.

Sandeep, who I’d brought with me, turned to me and asked in Mr. Christopher’s hearing, “Is that the fool of a clerk who gave you your nickname?” When I agreed that it was, he added, “Well, well. You certainly seem to have the situation under control.” Perhaps I had misjudged the boy after all.

George and George couldn’t stop themselves gawking at Sandeep as I led him along to Mr. Bruff’s office.

“I wouldn’t do that, if I was you,” the older George warned me as I went to knock, which earned him a punch on the arm from his younger colleague. “Mr. Bruff’s got some bigwig from Scotland Yard with him,” he carried on, despite it. “He won’t like you barging in.”

“It’s all right,” I said. “It was me who invited the sergeant here. He’s keen to meet my friend, Sandeep.”

“Hello there, my name’s George,” said George, offering Sandeep his hand. The younger George took exception to this and dug his friend in the ribs with his elbow. As the pair shook hands, I explained that my companion had once been the Maharajah of Lahore—which wasn’t entirely untrue—much to the older George’s delight and the younger George’s huffy consternation.

When we finally entered the office, we found Sergeant Cuff and Mr. Bruff reminiscing about their parts in the Moonstone affair, with two of the sergeant’s men in attendance, respectfully looking on. That put the wind up me, I’m not ashamed to say. The fact that there were two of them seemed significant. Mr. Bruff’s mouth dropped open as I ushered Sandeep into his presence. Worryingly, Sergeant Cuff’s did not.

For quite some days now I’d been keeping Mr. Bruff in the dark about my various activities. Though once again he was brimming with questions, I managed to stave them off by promising to reveal everything as soon as we got to the Blakes’. So, without further ado, he retrieved the daguerreotype from his safe at my request and we all set off.

It was Samuel, the footman, who once more answered the door to us. He took Mr. Bruff’s hat quite willingly and then deigned to take the sergeant’s. The sergeant’s two men, however, he pointedly ignored. As Mr. Bruff led the way towards the library, he finally turned to me.

“You hat, sir?” he asked. If even the judgmental young Samuel was prepared to take my hat, I had clearly come up in the world. I smiled as I handed it to him, then followed my employer in.

With the addition of Mr. James, who I had finally forgiven for attempting to cut my throat, everyone in the household was present, just as they had been on that previous Monday, when we’d first been summoned to attend. Though they greeted Sergeant Cuff warmly enough—for it was some two or three years since they had last seen him—the warmest reception they reserved for me.

“Is this who I think it is?” Mrs. Blake whispered in my ear, as she stole up behind me. She’d been regarding Sandeep with an almost reverential stare ever since we’d entered. Unfortunately he overheard her.

“My name is Sandeep,” he said, introducing himself, “though most people call me Mutari, which in my language means Magpie, for there is no fleeter-of-foot—”

“No,” I hastily cut him short. “It’s not. But we’ll get to him presently, I promise. You see, we’re still waiting for people to arrive, miss.” Turning to my employer, I asked, “What time is it, sir?”

Mr. Bruff consulted his watch. “Nearly half-past ten,” he replied.

“Mr. Betteredge,” I said, “I see you have your copy of Robinson Crusoe with you. While we wait, may I ask, has that excellent tome any guidance for us today?”

Eyeing the sergeant and his men warily from his seat by the fire, the elderly servant nodded, cleared his throat, and read, “‘…if they were sent to England, they would all be hanged in chains, to be sure; but that if they would join in such an attempt as to recover the ship, he would have the governor’s engagement for their pardon.’ For their pardon, sir. For their pardon.”

It really was uncanny what the man could do with that book of his. He was better than a gypsy fortune teller in a tent. My thoughts were interrupted, however, as Samuel entered the room. He was looking decidedly shaken.

“A Mr. Thomas Shepherd and a Dr. John Login to see you, sir,” he announced. “And…and…and…”

“And what?” asked Mr. Blake.

My hopes rose, only to fall again as Samuel replied, “Well, some poor, thin wretch of a lad who claims to be the Maharajah of Lahore.”

Gooseberry continues next Friday, October 31st.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

If you’re prepared to write an honest review, click on this link to bid for an advance reviewer’s copy at LTER. You’ll find the listing approximately three-quarters of the way down the page.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

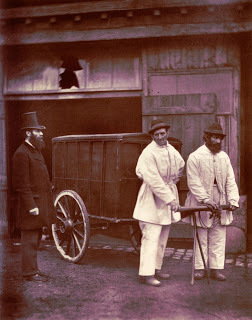

Photograph: Old Furniture by John Thomson, used courtesy of the London School of Economics’ Digital Library under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on October 24, 2014 06:07

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

October 17, 2014

Gooseberry: Chapter Sixteen

The orchestra, wielding their instruments loudly for once, struck up a fanfare—no easy task for a bunch of string players without a horn in sight, but they gave it their best—as the prince and his escort of three grave-looking gentlemen entered the banqueting hall. Prince Albert surveyed the room with a somewhat bewildered expression, as if he couldn’t quite understand why all the guests were bowing to him or—perhaps—why all the waiters were not. He was a pale-skinned gentleman with light blue eyes and a mop of dark hair that had all but receded from his forehead. He sported a fine pair of sideburns all the way to his jawline, which, together with the receding hair, created an almost perfectly oval frame for his face. It gave the impression that, instead of showing any actual flesh, he was wearing a porcelain mask.

The orchestra, wielding their instruments loudly for once, struck up a fanfare—no easy task for a bunch of string players without a horn in sight, but they gave it their best—as the prince and his escort of three grave-looking gentlemen entered the banqueting hall. Prince Albert surveyed the room with a somewhat bewildered expression, as if he couldn’t quite understand why all the guests were bowing to him or—perhaps—why all the waiters were not. He was a pale-skinned gentleman with light blue eyes and a mop of dark hair that had all but receded from his forehead. He sported a fine pair of sideburns all the way to his jawline, which, together with the receding hair, created an almost perfectly oval frame for his face. It gave the impression that, instead of showing any actual flesh, he was wearing a porcelain mask.Slowly the guests began to rise, only to replace their former bowing with a round of muted clapping. If anything, His Royal Highness looked even more uncomfortable with this. Turning to the most senior of the men accompanying him, he whispered something in his ear. The man raised his hand and gestured to the orchestra, who quickly struck up a waltz. It was barely audible.

People were starting to circulate again. I looked to see where Johnny and Eric had got to, but they’d both vanished. I did spot Josiah Hook, however, dressed to the nines and looking every bit the kind of young gentleman to add term esquire to his name. I began to make my way across the room to warn Sergeant Cuff, but was stopped in my tracks as Colin appeared before me, also kitted out as a wine waiter. He looked none too pleased to see me. Within seconds he was joined by two others, effectively hemming me in by the side of the stage. I would have tried catching the sergeant’s eye, but by now he too had disappeared.

“You got me into so much trouble,” snorted Colin, whose jaw was bruised and looked painfully swollen.

“I’m sorry about that,” I replied, then added, “Looks like you have more trouble coming your way,” as I noticed the prince’s party rapidly approaching.

Colin threw them a glance but stayed where he was regardless.

People were bowing and moving aside as Prince Albert headed towards the stage. He pulled up a pace or two away from me and regarded the orchestra thoughtfully. He opened his mouth and asked a question, which sounded like, “Ken the note ply lot earthen this?” The musicians glanced nervously at each other.

“You heard His Royal Highness,” said the senior dignitary at his side, who had been eyeing the enclave of stationary wine waiters. “Louder!”

The musicians played louder. “March bitter,” remarked the prince. “And water these find a liquor sea spray?” he asked, turning to me. I gaped up at him, blinking.

“Look, the boy’s clearly in awe of you, Your Highness,” the dignitary responded, and everybody laughed.

Though not in awe exactly, I was however speechless, having no idea of what was being asked of me. I wasn’t even sure if the prince was speaking English. Colin and his cronies took the opportunity to melt into the crowd, positioning themselves where they could pounce on me again, and in a hurry if need be.

“The look entry king,” mumbled the prince, reaching for the very pastry I’d had my finger in scarcely ten minutes before. I quickly spun the tray around so that he’d pick a different one. “Tell me,” he said, examining the pastry I was offering him, “water the cold?” His hand paused in mid-air.

“What are they called, boy?”

“ Oh! Pastries?” I suggested. “Savories? I think they’re made with chicken livers, sir, but it’s very hard to tell.”

“Your Royal Highness,” said the dignitary, addressing himself to me.

“What?”

“‘I think they’re made with chicken livers, Your Royal Highness’.”

I studied the man’s puffy, red face, wondering if by any chance he was related to Mr. Bruff. “Oh…sorry, yes, of course,” I said at last. “I think they’re made with chicken livers, Your Royal Highness, but it’s very hard to tell. They’re not as good as Mrs. Grogan’s, see.”

“Whose?” asked the prince, settling again on the one I’d had my finger in.

“Mrs. Grogan’s. She runs the best eating house on the Gray’s Inn Road, Your Royal Highness. You should think about going there sometime.” I gave my tray another spin, but to no avail, for this time he kept his eyes trained on the pastry in question. “Here, why not try this one?” I picked up choicest of the batch and held it in front of his face.

“I think the lad’s a little simple,” the senior dignitary whispered in the prince’s ear, just as the prince snatched the one he’d been after all along and stuffed it in his mouth.

He chewed on it appraisingly, nodding several times, and then gave his judgment: “You contest dash hairy.”

The dignitary selected one and took a bite. “You certainly can, Your Highness,” he said, seemingly agreeing with him.

“The sack white nice,” said the prince, taking another, though not the one in my hand. “Hmmm…note bed atoll. Half the let for low me.”

“Stay at His Highness’s side, boy; he may require more. And no more small talk, understand?”

“Understood, sir.”

The prince set off towards the middle of the room. I followed, platter in hand, walking with the stately, dignified gait that I now had down pat. All the guests bowed before him as we moved through the crowd, and I began to get a sense of what it was like being His Royal Highness. Whenever he moved, he was a ship plowing a sea of roiling bodies. When he stood still, they stared at him. Or talked and stared, which was even worse, for any fool could tell that he was the subject of their conversations. As he came to a halt under the broadest of the chandeliers, I noticed that everyone was now talking and staring. No wonder he seemed embarrassed by it all.

“Chin up, Your Royal Highness,” I whispered to him softly, so that the senior dignitary couldn’t hear. “They can’t all be talking about you.” The prince looked down at me and smiled. “Here, have another pastry,” I suggested. I held up my platter but, just as I did, a hand thrust a bottle under his nose.

“More wine, Your Imperious Majesty?” It was Colin, who was glowering at me even as he spoke. He was so intent on intimidating me in fact that he failed to notice the silence that was overtaking the room. It was only when the orchestra stopped playing that he finally looked about, and saw that everyone was staring at him rather than the prince.

“Imbecile!” snapped the dignitary. “That is not a proper form of address for His Royal Highness! Guards! Remove this oaf at once!”

“No!” begged Colin, looking at the man with pleading eyes. “I’m needed here—I’m really needed here!”

“You most definitely are not,” came the reply. Two guards from the door appeared and bundled the bewildered Colin from the hall. The dignitary mopped his brow, then turned to the prince and said, “Your Highness, I cannot apologize enough.”

The prince nodded and said, “Lettuce half music.”

The dignitary lifted his hand and signaled to the orchestra, who quickly struck up another waltz.

“What did he do wrong?” I whispered in the prince’s ear.

“Apart from implying that I’m overbearing? He addressed me as one would a king,” the prince whispered back, enunciating every word perfectly, “yet I can never be king. A minor embarrassment for me, but major embarrassment for everyone who heard him draw attention to the fact, no? Son, your eyes are bulging.”

“You speak English!”

“Naturally I do! Just promise not to tell anyone. People might come to expect conversation from me, heaven forbid, and what would I have to talk about?”

All through this hushed exchange, the dignitary—a florid, portly man who gave the prince a run for his money in the whiskers department—was getting redder and redder in the face. I think nothing would have pleased him more than to have me removed from the hall, too.

“Your Highness,” he said at last, interrupting us to stem his imminent apoplexy.

“Yes? Wet a sit?”

“It’s time to present the diamond, sir.”

“Egg salad!” Prince Albert turned to me and murmured, “And about time, too.”

The senior dignitary and the elder of the other two men walked slowly towards the back of the hall. The crowd parted before them, opening up a splendid view for myself and the prince of a small mahogany table set against the far wall. Just as they reached it, two stewards came shuffling in, bearing a velvet-draped, rectangular object between them. This they positioned on the table top with painstaking care, fussing over the folds of the cloth for what seemed like minutes. Finally they turned to the dignitary and nodded.

“Your Royal Highness, ladies and gentlemen,” he announced, “I present the Kohinoor diamond!”

The crowd gasped as the two stewards whipped away the cover, revealing a glass case containing a large, dark, amber-colored stone.

“Did you see it on display at the Crystal Palace?” whispered the prince.

“No, Your Royal Highness. I couldn’t afford the admission.”

“‘Sir’ will suffice, lad. You may address me as one gentleman to another. What is your name?”

“Octavius, sir, though most people call me Gooseberry.”

“Would you like to see the Kohinoor, Octavius? Yes? Then follow me.”

With both of us walking at a slow, stately pace, we set off down the broad walkway left by the retreating guests. Now the people on either side of us dipped rather than bowed, due to the cramped conditions they found themselves in. I scanned the crowd, but though I spied a number of waiters and wine waiters—Sergeant Cuff’s men among them—I saw no sign of Johnny and Eric.

The closer we got to the diamond, the more detail I could make out. The stone was enormous, the size and shape of a baby tortoise shell. It had been cut to resemble one, too. Its dark, murky appearance bore a suggestion of trapped smoke. It looked nothing like any of the diamonds I’d handled during my time in the Life—nor those that I’d seen after, for that matter, adorning the fingers, earlobes, and throats of Mr. Bruff’s clients.

The prince and I were barely ten paces away from the cabinet when it happened. From the left side of the hall, Eric came charging at the case like a raging bull. At precisely the same moment, Johnny’s wine waiters struck, pushing anyone and everyone near them to the ground. Knowing that glass was about to go flying, I ducked in front of the prince, threw myself at him, and screamed, “Down!”

As the prince toppled backwards, shards of glass rained down on top of us, missing his face, but catching me in the back of the neck. Amidst the screams and the sobbing, I heard Eric’s roar of triumph bellowing out behind me through the hall.

Suddenly I felt hands grab me, wrenching me off the prince and spinning me round. As I looked up into my captor’s eyes, I immediately stopped struggling for I recognized him at once as one of Sergeant Cuff’s men.

Whether or not he recognized me in turn, he didn’t relax his grip. “Attack His Royal Highness, would you?” he growled.

“No, you got it wrong! I was only trying to protect the prince! Don’t you recognize me? I’m with Sergeant Cuff, too!”

“I got him!” boomed a voice, drowning out my protests, so loud that everybody in the hall froze on the spot. Each and every last one of us gazed at the the shattered remains of the glass case where Johnny stood clutching a kneeling Eric by his long mousy hair. Eric looked shocked, betrayed, and every bit as baffled as I myself was. Johnny, who was clearly delighting in being the center of attention, bawled, “I got the thief!” again, then reached into Eric’s pocket and drew out the diamond, holding it up for everyone to see. Sergeant Cuff, who was only a few feet away from him, came forward and removed the stone from his hand. He examined it momentarily, turning it over and peering at its surface.

Order was rapidly being restored throughout the room. Two guards appeared and took charge of Eric. When I tried calling out that they should be taking Johnny too, the man who had me in his clutches put his hand over my mouth to gag me. Transformed once more into an amiable sheep, Eric allowed himself to be led away without protest. The same could not be said of Johnny’s other men, who were still wrestling with their captors as they were dragged from the hall. When my captor started prodding me towards the doors, I realized that I was to be counted among them.

“Sergeant Cuff!” I screamed at the top of my voice through his fingers while I wrestled like an eel in the man’s firm grip. “Sergeant Cuff! Help!”

Hearing my muffled pleas, the sergeant looked up. “You can give that one over into my charge, Evans,” he said, raising an eyebrow at me. “I doubt he’ll try to run away.”

“But, sir, he attacked His Royal Highness.”

The prince was looking shaken, but at least he was on his feet again. “Heated nose arch thing,” he told the man sternly, and then turning to me, as clear as a bell, he added, “Thank you, Octavius. You saved my skin, sir, and most probably my sight.”

The senior dignitary, who’d been stationed close enough to the exploding glass to have received a number of minor cuts to his forehead and cheek, approached the sergeant and spoke quietly to him for a few moments. In all the kerfuffle, Johnny had vanished. I spotted Eric’s brother Colin, though. Having managed to sneak back into the hall, he was standing by the doors with a look of utter shock on his face.

The sergeant summoned Evans, the man who’d dragged me off the prince, and handed the florid, portly dignitary the gem. I went and joined Sergeant Cuff as the two men moved away, taking the diamond with them.

“Sir, that man who apprehended the wine waiter was none other than Johnny Knight, the head of the gang I was telling you about.” The sergeant regarded me gravely. “He planned this, sir, so it makes no sense at all that he would actively participate in his own man’s capture…unless—” In my mind’s eye I could see Johnny murmuring a question in my ear: what do you call someone who’s second-in-command? When I’d suggested the term deuce, he’d laughed and told me, “Stooge.”

“Unless?” prompted the sergeant.

“Unless he substituted the diamond for a replica.” The words just fell out of my mouth. “Then, hero of the day, he’s free to disappear.” Just as I’d told Mrs. Blake at the start of this case, of the two ways of lifting things, the second is infinitely more satisfying. While the gang is wreaking chaos and everyone’s attention is diverted, somebody else—someone on the spot who seems quite unconnected with any of the troublemakers—he stealthily slips the desired items inside his jacket. Once the gang has scarpered, that person calmly walks away, taking his booty with him.

“But he didn’t make a substitution,” insisted the sergeant, breaking my train of thought completely.

“What?”

“I guarantee you he handed me the Kohinoor itself. The diamond was no replica.”

“How can you be sure?”

Sergeant Cuff blushed. “Fearing just such a situation, I took measures.”

“Measures?”

“I did something to it, if you must know.”

“Did something?”

“Gooseberry, does it really matter?”

I put on my hurt face and blinked a bit. “I suppose not,” I sniffed. Bertha would have been proud of my performance.

“Oh, very well,” the sergeant tutted. “I took a roll of brown paper tape and tore off a tiny piece of it. Then I licked the gummed edge and affixed it to the underside of the gemstone. You couldn’t really see it unless you looked for it. When this Johnny person handed me the diamond, it was the first thing I checked. It was exactly where I put it.”

“Genius!” I cried. I meant it, too. I really couldn’t have done better myself. Unfortunately it brought us back to square one, though, for Johnny’s actions no longer made the slightest bit of sense. Could it be that, in the heat of the moment, he’d forgotten to switch the diamond? Or was he just as mad and deluded as I’d originally thought? I pictured the look that I’d seen on his face, the look of someone who’s just succeeded in bringing off a major coup. No, I was missing something here. “Where is the diamond now, sir?”

“With Sir Humphrey Mallard.”

“What?”

“With Sir Humphrey Mallard,” repeated the sergeant.

“The man you gave it to? That florid, portly gent?” To my horror, I saw the sergeant nodding. “But he’s the one behind all this! Why did you give it to him?”

“I had no choice. As the man who negotiated the Kohinoor as part of Britain’s settlement after the Anglo-Sikh War, it’s his task to hand it over to the head of the firm charged with re-cutting the stone. Given this evening’s events, the transaction’s now to be held in private. Don’t worry…the diamond is safe. Evans will have his eye on it. Gooseberry, what’s the matter?”

I barely heard Sergeant Cuff, for I was deep in thought. Somebody else—someone on the spot who seems quite unconnected with any of the troublemakers—he stealthily slips the desired items inside his jacket. Not Johnny, but rather the senior dignitary in charge: Sir Humphrey Mallard.

“Johnny didn’t make the exchange, sir, because Mallard’s going to do it. If everything had gone strictly to plan tonight, would Mallard have had a chance to touch the gem?”

The sergeant frowned. “No, he wouldn’t. His role was purely ceremonial.”

“Then Johnny’s job was to make sure that he could…and to provide a plausible scapegoat in the form of Eric for when the replica is found to be fake.”

“If you’re right,” said the sergeant, “then we have no time to lose.”

“No…no, sir,” I warned him. “Timing is everything now. Until Mallard exchanges the diamond, there is nothing we can prove. You said this transaction was taking place in private?”

“Follow me,” said the sergeant, setting off at a rapid pace and summoning one after another of his trusty men along the way. Some he tasked with searching the building for Johnny. Others he sent off at my suggestion to investigate the Bucket of Blood. The rest of them trailed behind us to a room at the back of the building. The chamber’s four occupants looked up in surprise as the sergeant and I burst in on them.

Mallard, who was on the point of placing the diamond in a plush-lined a casket, froze. His counterpart, whom I recognized from earlier, frowned. Evans, the sole person standing, glanced over at the sergeant with a questioning look. Only the prince spoke.

“Octavius! Sergeant Cuff! Is there a problem here?”

“No, Your Highness,” replied the sergeant. “I’m sure everything’s perfectly in order. Sir Humphrey, won’t you continue?”

The portly man’s hand was trembling as he lowered the gem into the box. His face was flushed. Reluctantly, ever so reluctantly, he eventually closed the lid. A bead of sweat worked its way down the scratches of his wounded cheek as he held out the casket. But even then he seemed unwilling to relinquish it. The man sitting opposite him had to pull it out of his hands. Had he failed to switch the diamond and didn’t want to give the real thing away? Or did he know the game was up and was reluctant to hand the replica over while there was still a chance to switch it back?

“Sir Humphrey, I require you to stand,” said the sergeant.

Quaking, the man rose to his feet. I applied my pickpocket’s eye to his generously-cut attire.

“The inside left breast pocket of his waistcoat,” I whispered in the sergeant’s ear.

The sergeant deftly inserted his hand and pulled out a smoky-brown diamond. I held my breath as he turned it over. There, on the back, was glued a tiny strip of brown paper tape.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, October 24th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

If you’re prepared to write an honest review, click on this link to bid for an advance reviewer’s copy at LTER. You’ll find the listing approximately three-quarters of the way down the page.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

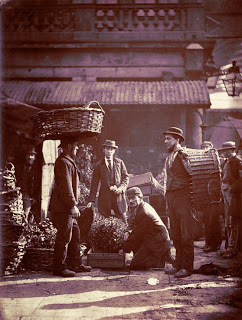

Photograph: Covent Garden Labourers by John Thomson, used courtesy of the London School of Economics’ Digital Library under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on October 17, 2014 06:09

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

October 10, 2014

Gooseberry: Chapter Fifteen

I cannot deny that I nearly jumped out of my skin as I felt the hand land on my shoulder. My first instinct was to bolt, but I was prevented from doing so by a second hand that seized me firmly by the collar. For the pickpocket, one reason you sport an overly-large jacket is so you have room to stow the things you filch; another is that it’s much easier to shrug it off if someone makes a grab for it. My assailant must have known this, for he went directly for my shirt.

I cannot deny that I nearly jumped out of my skin as I felt the hand land on my shoulder. My first instinct was to bolt, but I was prevented from doing so by a second hand that seized me firmly by the collar. For the pickpocket, one reason you sport an overly-large jacket is so you have room to stow the things you filch; another is that it’s much easier to shrug it off if someone makes a grab for it. My assailant must have known this, for he went directly for my shirt.“Calm down, boy,” hissed a voice in my ear. “You’re making a spectacle of yourself, and I dare say you wish to avoid making public displays…especially here, in front of East India House.”

The voice trembled with a deep melancholy undertone, suggesting perhaps that paradise had fallen and the vast majority of mankind had consequently gone to rack and ruin. It struck a chord in my memory. I turned my head and looked.

“Sergeant Cuff!”

“Gooseberry.” Steely light-gray eyes stared at me from a yellow, weather-beaten face. They twinkled as my old acquaintance slowly began to relax his grip. Before his retirement to the small town of Dorking, the good sergeant had been Scotland Yard’s most celebrated detective. Three years earlier, I’d had the privilege of working with him to uncover the truth behind the Moonstone diamond. The last time I’d seen him, he’d been dressed in whites and grays, and looked every bit the country gent. The man who stood before me now wore sombre black, with one small flourish: a white cravat at his throat. Being so lean and wiry, he now had the appearance of a seasoned undertaker, and one who’s done mighty well for himself from his long career.

“I thought you retired to grow your roses, Sergeant Cuff.”

“I did, lad, I did. It would seem that you haven’t, though…”

“I’m sorry?”

“Retired, boy. This is the third time I’ve seen you here this week.” When I put on my puzzled face, he tutted and proceeded to tell me, “You were here on Thursday, you were here on Saturday, and you’re here again today. I ask myself, could it be that you’ve found alternative employment to your post in a solicitor’s office, or do you happen to be working on a new case?” The sergeant smiled at me gravely, drat him.

It’s one thing to run rings around members of the upper classes, who can barely see past the tips of their own noses, so engrossed are they in their public and private affairs. Sergeant Cuff, on the other hand, was a very different wheel of cheese. Retirement aside, he was essentially a working-class man who had kept company with the most talented crooks and thieves in the land. He’d learned a trick or two in his time. He was not someone, like Mr. Bruff, who would be dazzled by the simplest smokescreen; he could read men’s hearts.

“It’s a long story,” I replied.

“Excellent. I love a good story, and I have a feeling I shall wish to hear it all.” He emphasized the word ‘all’. “There’s a public house down that alley there that serves a mighty fine porter,” he continued. “We shall retire its gloomy interior for refreshments and you can tell me everything.” You can guess for yourself which word he emphasized this time.

By common consent we chose a window seat, so that we could actually see what we were drinking. Sergeant Cuff had his glass of oily, brown bitter in front of him. I had my bottle of ginger beer. I started by explaining about the portrait: who it depicted, how it was found, and who put it there. At some point the sergeant pursed his lips and muttered, “The Maharajah of Lahore, you say? Hmmm. Significant. Undoubtedly significant.”

If he considered that significant, I don’t know what he’d call my next revelation, for beer sprayed from his mouth in all directions when I told him about our trip to Cole Park Grange Asylum.

“How did you know the boy you saw was an impostor?” he demanded.

“Besides his remarkable ability to pick pockets? Well, the note specifically said that the maharajah would be put to death; it didn’t say, ‘I’ll be put to death’.”

“Good point.” Sergeant Cuff was looking seriously worried. “But this can only mean…” His voice trailed off as he lifted his glass to his lips.

“That they were planning to use the boy to steal the Kohinoor diamond,” I said, finishing his sentence for him. Beer went spraying everywhere again. I discreetly took out my handkerchief and gave my face a wipe.

“Gooseberry, you really will have to explain yourself. How on earth do you arrive at that conclusion?”

I told the sergeant about how Mr. Bruff had claimed to have deposited the daguerreotype with his bank and how the bank was subsequently razed to the ground, how the Indian lad I’d met had absconded and how, as a consequence, Mr. Treech had been shot. I recounted the man’s dying words as fully and accurately as I could, though focusing mainly on the diamond.

“As soon as he mentioned the word ‘diamond’,” I explained, “I immediately thought of the Kohinoor. It stands to reason that the prize these people were after had to be worth all the expense and trouble they invested into getting it. What better fits the bill than the largest diamond in the world? Of course, now that the boy they had posing as the maharajah is on the run, whatever plans they were hatching have been put paid to.”

Sergeant Cuff nodded thoughtfully. “Hold on,” he said. “You say this chap Treech was shot on Monday. Yet I saw you coming out of the East India Company, looking rather pleased with yourself, last Saturday—two days before the man’s dying confession.”

I told you the sergeant was sharp. I began to explain Johnny Knight’s role in the matter and how he reported to a man named Josiah Hook. I was careful not to give away how I’d come by Hook’s name for, as far as I’m aware, the sergeant is still unaware of my skills and I should like to keep it that way. I described how I’d followed Hook back to Leadenhall Street, and my little ruse with the diaries to establish not just where he worked, but whom he worked for as well: Sir Humphrey Mallard.

“Mallard, eh?” The sergeant’s face looked grim as he pondered the name. “So what did they do with the real maharajah, I wonder?”

“He’s safe for now,” I told him, and went on to explain about James’s wayward brother Thomas, and how he’d had a change of heart and taken the maharajah and his guardian into hiding.

“Do you know,” said the sergeant, “I once made a prediction about you, lad, to Mr. Franklin Blake himself. I said that one day you would go on to do great things in my late profession. It seems you have proved me right.”

“Your late profession, sir?” Sergeant Cuff was not the only person at the table with brains enough to see through smokescreens.

His eyes narrowed. “You heard me, lad. My late profession.”

“So it’s just a coincidence that you happened to be standing outside the East India Company on the occasions of all my visits?” The great man’s face remained impassive. With control like that, he could have gone on to do great things in my late profession. “If I recall rightly, sir, you were all too keen to retire and grow your roses. The only reason you returned to investigate the later developments in the Moonstone case was the debt you felt to Mrs. Blake’s mother, who you considered had overpaid you for your time.”

The sergeant gave a guarded nod. “There were professional reasons, too,” he added. “I don’t like being wrong. I don’t like unsolved cases. I prefer my world to be orderly.”

“So I find myself wondering,” I pressed on, “what it would take to bring you out of retirement once again? Another unpaid debt, perhaps, but not necessarily of a financial nature? The threat to a loved one? A belief in a righteous cause? A sense of obligation or duty?” I was studying his eyes as I ran through my list. His eyelids had flickered ever so slightly at the suggestion of obligation and duty, yet the sergeant said nothing.

“A sense of obligation or duty, then,” I continued, no longer phrasing my thoughts as questions. “An appeal that cannot be denied. A request from the highest in the land. Her Majesty Queen Victoria herself, perhaps. No—not the Queen.” His eyelashes had wavered, but not in the way I was expecting them to. “The Prime Minister, Lord John Russell? No? Then there’s only one person it can be.”

“Really?”

“The Queen’s husband, Prince Albert.”

Sergeant Cuff puckered his lips and gave a long, low whistle. “I take my hat off to you, young detective. I couldn’t have done better myself. Yes, the prince himself requested my presence on a matter of security. You have become every bit my equal. No, that’s not quite true, for in the matter of the Kohinoor diamond, you have surpassed me.”

“Surpassed you, sir?”

“While I’ve been keeping my eye on the building, and getting gossip from the porters and the kitchen staff, you’ve been unearthing the plot that I should have had wind of from the start.”

“But I had the good fortune of being called for by the Blakes when Mrs. Blake’s aunt discovered the daguerreotype in her possession. It was just a stroke of luck, sir.”

“Tell me again about the boy, this impostor of Mallard’s. You’re certain he’s on the run?”

“As certain as I can be, sir. The boy didn’t seem to be a willing accomplice.”

“Good. All the same, it wouldn’t do to become complacent. I imagine they’re searching for him as we speak.” It was a possibility, of course, though after seeing Johnny and Eric’s performance of the previous night, it seemed unlikely. Johnny was too caught up in his own madness to organize anything like a search. “But what if they were able to find him in time?” the sergeant added, posing the question to himself.

“In time for what, sir?”

“The reception they’re holding tonight at East India House.”

“Reception?” Something stirred at the back of my mind. Something that James had told Miss Penelope when he met her at the zoo. Something about how Thomas believed they only needed the maharajah out of way until the day after the reception. “What’s this reception in aid of, sir?”

Sergeant Cuff laughed. “Do you mean to tell me that there’s something you don’t know?”

“Please, sir. I’ve a feeling it may be important.”

“Do you know the history of the Kohinoor diamond? Its recent history, I mean.” Sergeant Cuff gave me a reproving look as I shook my head, as if to say that I should have made it my business to find out. “Until a couple of years ago, it belonged to Duleep Singh.”

“So that’s how the young maharajah comes into it?”

The sergeant nodded. “Yes, lad. He inherited it from his father, Ranjit Singh, who obtained it from a man named Shujah Shah Durrani, the deposed ruler of Afghanistan, as the price for granting him asylum in Lahore. When East India Company troops won the Second Anglo-Sikh War and annexed the Punjab, the stone was counted among the spoils of war and, as such, it was presented to Queen Victoria. Last year it went on display at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Did you happen to catch it there?”

“No.” Not at a shilling a pop, I didn’t. Those were the days before my per diem.

“Being the largest diamond in the world, it naturally drew in the crowds, but it also caused quite a controversy.”

“In what respect, sir?”

“It didn’t catch the light, lad. No matter how they angled it in its glass display case, it simply didn’t sparkle the way that everyone imagined it should. The powers-that-be decided that something ought to be done about it. The stone is to be re-cut, and the Prince Albert himself is to oversee the operation personally. At tonight’s reception, he’ll be handing the gem over to the firm that has been tasked with doing the work.”

“And the Maharajah of Lahore was expected to attend?”

“Yes, as a guest of honor. Gooseberry, are you all right?”

No, I wasn’t all right. I had a bad feeling about this. Some phrase, some turn of words the sergeant just used had triggered it but, for the life of me, I couldn’t think what.

“Sir, there’ll be adequate security precautions taken tonight, won’t there?”

“I am in charge of all the arrangements,” Sergeant Cuff replied warily.

“And I take it Prince Albert isn’t bringing the diamond himself?”

“No that would be highly irregular.” The sergeant leaned across the table, tapped the side of his nose with his forefinger, and addressed me in a whisper. “Officially it will be transported by an armed escort, due to arrive at six this evening. Unofficially two of my best men will be bringing it by a different route. The reception, which starts at eight, is to be held in the banqueting hall and my men will stay with it throughout. It’s a large room, so I’ve arranged for twelve of my officers to pose as waiting staff. They’ll be able to circulate while keeping their eyes peeled for any sign of trouble.”

“Sir?”

“Yes, Gooseberry?”

“Can I…may I…please attend? I have a very bad feeling about tonight.”

The sergeant looked at me and smiled. “I thought you’d never ask,” he said. “Come on. Let’s see if we can’t get you kitted out. I expect they’ll have some livery in your size. You won’t be able to wear that bowler hat of yours, mind, and I imagine we’ll have to hide those bruises round your throat.”

By a quarter to eight I was garbed up like the rest of the waiters—Sergeant Cuff’s men included—in white shirt and breeches, and a tail coat of red and gold brocade. We were receiving our final orders from the steward, which included strict instructions of how we were to act—and not act—should we be lucky enough to encounter His Royal Highness. It all seemed like a great fuss about nothing, if you ask me. I mean, who amongst us would even consider trying to shake his hand?

“To your trays!” barked the steward. “Quickly now!”

I picked up a large silver platter of puff pastry cases filled with some gray-looking sludge and garnished with a bit of parsley. As I lined up in the queue for the banqueting hall, I tested one by dipping my finger in it. I think it was a concoction of chicken livers—it was hard to tell—perhaps with some sherry thrown in. The sherry saved it. It still wasn’t up to Mrs. Grogan’s standards and I began to feel sorry for the prince.

“And out you go!” the steward commanded us. “No jostling, now! Proceed in a stately, dignified manner!”

The banqueting hall was lit entirely by candles, their beams caught and reflected in the crystals that drooped like shimmering fruit from the chandeliers. A fire blazed in an ornate fireplace that was large enough to accommodate an ox roasting on a spit. There was even an orchestra of sorts, made up solely of string players, whose aim in life seemed to be to play as quietly and inoffensively as possible. Small groups of people stood chatting together, their glasses charged to the brim by the circling wine waiters. I myself began to circle, but nobody seemed to fancy the savories on my tray.

I spied Sergeant Cuff by one of the windows, keeping a wary eye out. Just as I was about to go over and greet him, some chap at the door announced the imminent arrival of the prince: “Ladies and gentlemen, I present His Royal Highness Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Saxony.”

The waiters had been warned to move to the sides of the hall, stand stock still, and pretend to be invisible. With a stately, dignified gait that the steward would have been proud of, I made my way over to the orchestra, whose stage was by the wall nearest me, and stood like a marble statue as the prince made his grand entrance. I decided to chance a sneaky glance at the doorway, but my eyes never quite made it that far.

As the guests started bowing and curtseying, the only people left standing upright were the waiting staff. In the opposite corner of the room, staring back at me with a furious, glowering expression, stood Johnny Knight, togged up in a wine waiter’s outfit. And next to him, in similar attire, stood Eric.

Suddenly I knew the phrase that had bothered me when Sergeant Cuff was talking about the diamond: ‘no matter how they angled it in its glass display case’. Its glass display case. Johnny Knight may not have been as mad as he appeared after all.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, October 17th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

If you’re prepared to write an honest review, click on this link to bid for an advance reviewer’s copy at LTER—you'll find the listing about three-quarters of the way down the page.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

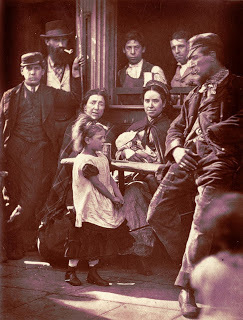

Photograph: Cast Iron Billy by John Thomson, used courtesy of the London School of Economics’ Digital Library under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on October 10, 2014 06:08

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

October 3, 2014

Gooseberry: Chapter Fourteen

How six years can change a person. The last time I’d seen him, Johnny Knight had been a tall, thin, spotty adolescent with a mop of hair the color of rat’s urine. He’d sprung up and out since then, but the main difference was in his face. His rotting teeth had caused his cheeks to collapse inwards, puckering his mouth and giving him the appearance of a bitter, old man. I noticed his dress sense hadn’t changed any, despite his elevated position—but then, I suppose, neither had mine.

How six years can change a person. The last time I’d seen him, Johnny Knight had been a tall, thin, spotty adolescent with a mop of hair the color of rat’s urine. He’d sprung up and out since then, but the main difference was in his face. His rotting teeth had caused his cheeks to collapse inwards, puckering his mouth and giving him the appearance of a bitter, old man. I noticed his dress sense hadn’t changed any, despite his elevated position—but then, I suppose, neither had mine.“Heard you was back,” he said, taking a swig from the whiskey bottle he was holding, as two young lads ran forward and began sweeping up the glass. “Edinburgh, was it?” That’s certainly where I told Bertha I’d been. “As you can see, there’s been a few changes round here, so don’t go getting any funny ideas. It wouldn’t be healthy.”

“It’s nice to see you, too, Johnny,” I said brightly.

Johnny frowned, unable to work out whether I was being sarcastic or not. Though ‘sarcastic’ may not have been in his vocabulary, he had a keenly honed sense of when someone was being disrespectful to him. Note to self: do not push your luck.

“Was that any better, Johnny?” Eric asked, giving me a nod of recognition, albeit a wary one. Like his brother, Colin, perhaps he thought I was here after his job.

“Me old mother could have made a better hash of it,” barked Johnny, “and she’s been dead nigh on ten years. Again! You’ll do it again!”

The two lads who’d been cleaning up placed another pane of glass across the bar stools. Eric glowered at me and began to pace the room again, attempting to work himself up into a frenzy.

“Remember when you and me were mudlarks together, Octopus?” Johnny turned to me and asked. “Picking through the stones on the riverbank at low tide? Me, I always got the bits of bone, the scraps of wood. You, you got the copper nails and the lumps of coal. And do you remember when winter came, and we was both stuck on the shore freezing our behinds off? It was me what found us that Ragged School to take shelter in, but even then you had to go one better. You couldn’t just accept their hot potatoes and their magic lantern shows, you had to go and suck up to them teachers with all their bleedin’ book learning. But don’t think for one minute that you had them fooled. They knew you was in with the local gang like the rest of us. They knew what you got up to when we all went out on a job. Why is it, do you think, that they never grassed us up to the magistrate?”

“Perhaps they were being kind,” I suggested carefully.

Johnny took another swig of whisky. “Kind? Kind? Nah. You got it all wrong. Remember that old coot, what had the whiskers down to here? He took a liking to me. Too much of a liking, if you catch my drift. Swore he’d do anything for me. That’s why we was never grassed up. That’s why you was never grassed up.” Behind me, Eric was raging like a bull. “Because of that—and only because of that—you got to rise up through the ranks. Now—fair’s fair—I know that I did too. But it was you what became Ned’s second-in-command, not me.”

Johnny paused. He glanced at Eric and, judging him to have reached a sufficiently fevered pitch, screamed the word, “Now!” at him at the top of his voice. Sweat pouring off him, Eric raised the cane above his head and launched himself at the fresh pane of glass.

“What do you call someone who’s second-in-command?” asked Johnny, breathing the question into my ear as needles of glass exploded in all directions.

“A deuce?” I whispered back.

“A stooge,” replied Johnny, and he began to howl with laughter. Meanwhile, Eric was swaying, as if on the brink of collapse. Johnny ran at him and struck him across the face. “Again!” he screamed. “And this time put more backbone in it!”

Bertha was right. Johnny had changed, and not for the better. From what I could see, he’d descended into the depths of madness and seemed intent on dragging all those around him with him.

“So why are you here?” he asked, as the two lads set about sweeping up the glass again. “Come to take Eric’s place?” On hearing this, Eric threw me a filthy look. The cane in his hand started twitching.

“I’ve come to see James Shepherd. I’ve come to make him talk.”

“You?” Johnny’s cold, colorless eyes narrowed.

“Our mutual friend sent me. He believes that I may be…well, more persuasive, shall we say, at getting his brother’s whereabouts out of him.”

“Oh? And what mutual friend would that be?”

“He wouldn’t appreciate either of us using his name, now, would he? Let’s just call him the Client.”

In the blink of an eye, the whisky bottle was on the floor and Johnny hands were around my throat. “Let’s not,” he hissed, as he began to squeeze. “Let’s respect him by giving him his proper name.”

“Hook,” I gasped, while I could still get the words out. “Josiah Hook. I work for him.” Johnny didn’t relax his grip.

“If that’s true you’ll know his guvnor’s name.”

“Sir Humphrey…Sir Humphrey Mallard.”

Reluctantly Johnny let go of me. I gently fingered the tender muscles of my throat. I’d be wearing the bruises for weeks.

“What makes Joe think you’ll get anything out of him? I can be very persuasive, yet I got nothing.”

Joe? Clearly Johnny and Hook were as thick as, well, thieves. “Mr. Hook is appreciative of that. But he believes that maybe violence isn’t the answer in this particular case.”

“So what you going to do? Ask him pretty please? Promise he’ll get to live if he gives his brother up?”

“Something along those lines, yes.”

“You’re wasting your time!”

“Mr. Hook doesn’t think so.” Johnny snarled and bared his sadly diminished set of teeth. He looked set to choke me again. “Where have you put him?” I asked, shying away from the stench of his mouth. Even the whisky on his breath failed to disguise the smell of decay.

“End of the corridor. Last room on the left. Go knock yourself out.” Then he seemed to have an afterthought. “Anything you learn,” he added, “you report it to me. I get the credit for it, see?”

“Fine by me.”

By this point the lads had replaced the sheet of glass, and Eric had worked himself up into another frenzy. What had happened to the amiable sheep, I wondered? Silly question. He’d come under Johnny’s influence. As I closed the door behind me I heard Johnny shouting, “Now!”

The room where I found James was icy. Someone had left the window open on purpose and his skin was blue from the cold. First I removed his blindfold. One eye was bloodied and swollen, so swollen that it refused to open; the other blinked in dispirited fear. A hank of shoulder-length hair was missing from above his right ear where someone had taken the shears to it. The stubble on his chin now had all the makings of a beard.

“I’m going to remove your gag,” I told him, “but I need you to stay quiet. Do you understand? Nod if you understand.”

He stared at me with his one good eye, still blinking, but otherwise motionless.

“Mr. James, my name is Gooseberry. I work for the Blakes, Miss Penelope’s employers, and I’m going to try to get you out of here, but you have to promise to do everything I say. Can you nod?” This time there was a slight movement, though I’d scarcely call it a nod. “Good. Now, no talking, if you please.”

I took Bertha’s knife and carefully cut through the kerchief. James spat the small rubber ball out of his mouth, the one that the kerchief had held in place.

“I…know you,” he said softly, the words barely making it through his chattering teeth. “You’re the boy…from the zoo. You…threatened to hurt Penelope.”

“Mr. James, Miss Penelope is my friend.” This was somewhat of an overstatement, but there was no time to explain further. “I apologize for the deception, but it was a test to see how you really felt about her.”

“I…love Penelope.”

“I know. But I had to know for certain, so I devised a little test. I’m going to cut you free now. Ready?” In response, James gave another twitch of his head.

I started by cutting through the ropes at his wrists. Whoever tied him up had made a first-rate job of it. There was no way James could have escaped these bonds on his own. When I eventually managed to free his hands, he began to flex and stretch his fingers as I set to work on the cords that kept him strapped to the chair.

“What did you say your name was?” James asked quietly. I could feel his body trembling as I hacked away with the knife.

“Gooseberry. At least, that’s what they call me in the Blakes’ household. I actually work for Mr. Mathew Bruff, the Blakes’ lawyer. A junior clerk at his offices gave me the name.”

“What’s your real name?”

“Octavius. Octavius Guy.”

“Why are you helping me, Octavius?”

“Because if I don’t, they’re going to kill you. You understand that, don’t you?”

“But aren’t you’re risking your life?”

“Yes, Mr. James, I am.” I tugged at the ropes and they came away in my hands. James shuddered and stretched his arms. Hugging himself to keep warm, he started rocking back and forth in his chair. “Sit still, sir. I’m going to tackle your ankles now.”

Though he still kept rubbing himself to get his circulation flowing, he managed to get his rocking under control. “Octavius, why are you risking your life for me?” he asked.

“Because Miss Penelope insists you are a good man.”

James nodded, a proper nod this time.

“There,” I said, as I finished. James attempted to stand, but his feet refused to bear his weight and he collapsed back into the chair. I put down the knife and went to help him up. “Put your arm around my shoulder, sir, and let me take your weight. We’ll get you walking again in no time.”

For a minute or so, we staggered around the room until James was able to support himself again. I bent down and opened the canvas bag, and fished out Bertha’s clothes.

“Mr. James, I need you to put these on. They may be a little loose, but they’re going to have to do.”

Suddenly James had his arm around me, pulling me to him. The blade of the knife was pressed against my throat.

“One final question, Octavius…or whatever your name is,” James hissed in my ear. “Just how would a young lad at a law office, and one who claims intimate acquaintance with the Blakes, come to know that I was being held here?”

“Mr. James, please put the knife down. You’re liable to hurt me with it.”

“Answer my question!”

“All right! All right! Six years ago I used to be part of this gang. But then Mr. Bruff found me and rehabilitated me. I do know the Blakes, sir, I swear it, and I’ve met Mrs. Merridew, in whose household you were once employed.”

“Then tell me something about her, something that the madmen holding me captive wouldn’t know.”

“Mrs. Merridew?” I had to rack my brains to remember anything about the old lady. Then it came to me. “She never realized that servants go courting on their afternoons off.”

The blade pressed harder. “That could be said of all the best families in London!”

“Wait! I have it. When you handed her your notice, she asked you if you were quitting because of the nuisance callers getting on your nerves.”

“And that, my friend, might be nothing more than a lucky guess on your part.”

I could feel the knife’s edge digging into the bruises Johnny had given me. “Explosions,” I said quickly. For a moment the pressure abated.

“What about explosions?” asked James.

“She doesn’t like them when they occur at night. Gunfire included.”

Slowly James released me. “I’m sorry about that,” he said. “I had to be certain that this wasn’t some intricate plan to get me to lead you to my brother.”

I held out my hand. “Knife,” I said bluntly.

“What?”

“Give me my knife back. Now. Then get into those clothes I brought you, and be quick about it.”

He handed back the knife, then went to examine the articles on the floor.

“Octavius?”

“What?”

“I really am sorry.”

“Then tell me, where is your brother Thomas?”

James’s one good eye blinked. “Honestly, I don’t know. If I need to contact him, I leave a message for him under a bench in Hyde Park. He does the same if he wants to contact me.” He stared at me imploringly. “That’s the truth, I promise. Now do you forgive me?”

“James, just put on the damned skirt.”

While James got changed, I went to deal with Colin, who was still on guard at the foot of the stairs.

“What’s up with you?” he asked. “You look angrier than a poke in the eye.”

Suffice it to say, no acting was required. “It’s Johnny,” I explained. “He wasn’t happy to see me. And he’s not happy with you for allowing me up there.” The smile on Colin’s face melted away, replaced rather rapidly by a look of alarm. “If I were you,” I continued, “I’d make myself scarce for a bit, at least till his temper dies down. Tell him you were dealing with some trouble out on the street.”

“Yeah…yeah, of course,” he mumbled, already backing away. “Trouble on the street…yeah…”

Once he’d turned and fled, I nipped back up the stairs. James had put on Bertha’s clothes, and was ready and waiting, the canvas bag they’d arrived in tucked under his arm.

“Keep your head down and keep the shawl pulled tight across your lower face,” I instructed him. “Move naturally and don’t run unless I tell you to, and try not to draw any attention to yourself. I’ll be at your side all the way; just follow my lead. I have a cab waiting for us in Long Acre that will take us to Montagu Square. I’ve asked the Blakes to set up an around-the-clock armed watch, so you’ll be safe there. Ready?”

“Tell me again,” said James, “why are you doing this for me?”

“At this point I really couldn’t say. Let’s just go before I change my mind.”

As we crept along the hallway and down the stairs, I heard one last pane of glass shattering behind the closed door.

It was going on midnight by the time we got to Montagu Square. Despite the lateness of the hour, the whole household rallied to receive Miss Penelope’s beau—even Mrs. Merridew, who seemed relieved to see her former footman safe, if not quite sound. James was soon divested of Bertha’s clothing, then put to bed so that Cook could treat his wounds, while Mrs. Blake and Miss Penelope sat on either side of him, pressing him for his story. Mr. Blake stood watching at the foot of the bed. I gathered up the clothes, returned them to the bag, and prepared to take my leave. As I reached the hall—where Samuel, armed with his pistol, sat guarding the entrance—I heard the sound of running footsteps following me. I turned and saw both Miss Penelope and Mrs. Blake standing there.

“You’re not very good at following orders, Gooseberry,” Mrs. Blake observed. “What happened to not putting yourself in any danger?”

“Miss, if you please, I’ve had a long night and I just want to go home.”

Mrs. Blake smiled. “We are in your debt, young man.”

Miss Penelope came forward and planted a kiss on my forehead. “I am in your debt,” she said. “Thank you for saving James.”

I nodded. Samuel opened the door for me and let me out, and I jogged down the steps to the waiting cab.

The room was in darkness when I got to my lodgings. I could hear Julius’s slumbering snufflings over by the stove.

“You all right, Octopus?” came a soft voice out of the dark.

“Yes, Bertha. I’m all right.”

“You done wot you was gunna do?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Are we safe?”

“It would be best if you kept wearing your disguise,” I replied.

“Wot about you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Will you need a disguise now?” When I didn’t answer, he said, “I put your bed-roll out for yeh, just in case. Come and get some shut-eye. You’ll be tired.”

I woke up late on Wednesday morning. Julius was long gone and even Bertha was already on his way out to pick up the daguerreotypes. I went and ate a leisurely breakfast at Mrs. Grogan’s fine establishment. Sated at last, and feeling the need to replenish my sadly diminished funds, I decided to tackle Mr. Crabbit. Needless to say, he was furious at my lack of receipts—so furious that he insisted on sending for Mr. Bruff. Thankfully, Mr. Bruff had already received a note from Mr. Blake, which praised my actions of the previous evening to the hilt. He politely but forcefully reminded Mr. Crabbit that he had given me his word that receipts would not be required for my per diems.

The slightly warmer, overcast afternoon saw me standing on Leadenhall Street, gazing up at East India House with its portico of towering Greek columns about the entrance. How was I ever going to get inside—not just through its doors, you understand—but inside the company, where I’d have access to Sir Humphrey Mallard and his cronies? And, just supposing that I somehow did, how was I ever going to bring them to book for what they’d done? My mind, I’m sorry to say, was a blank. Even as I let out an audible sigh, fate lent a hand—a hand that literally grabbed me by the shoulder.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, October 10th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

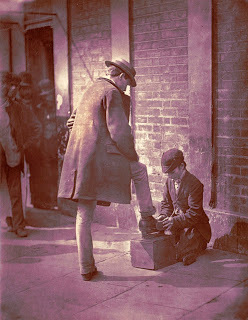

Photograph: “Hookey Alf” of Whitechapel by John Thomson, used courtesy of the London School of Economics’ Digital Library under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on October 03, 2014 06:09

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

September 26, 2014

Gooseberry: Chapter Thirteen

“Gooseberry, I have no idea how you can know the things you do, but since you seem to know everything, what can you tell me about this? Who has James? What will they do with him?”

“Gooseberry, I have no idea how you can know the things you do, but since you seem to know everything, what can you tell me about this? Who has James? What will they do with him?”I could hazard a guess on both counts and even speculate on his current whereabouts. Instead, all I said was, “Miss Penelope, these people are dangerous.”

“James is a good man. If you know anything, anything at all, I beg you to help me.”

I reached in my pocket for a coin. I took it out, looked at it, considered flipping it, then thought better of it. I stowed it away again.

“Miss Penelope, have you told Mrs. Blake about this?”

“Not yet.”

“Then I want you to go home and explain it to her. Tell her Gooseberry suggests that she closes Mrs. Merridew’s residence and has the servants transferred to Montagu Square. She should use them to set up an around-the-clock armed watch. As for yourself, miss, you must not set foot outside the house for the next few days, or at least until hear from me next. May I keep the note, please?”

“What do you plan to do with it?”

“I’m going to use it to try and get Mr. James back for you.”

“So you know where he is?”

“I have a fairly good idea.”

“Will you tell me your plan?”

“I’d rather not, miss.”

She blinked. “And when do you intend to act?”

“Tonight.”

Retaining the note, I replaced the lock of hair inside the envelope and handed it back to her.

“James is a good man,” she repeated, as she rose and took her leave.

I needed to think, but first I needed to prepare. I headed down to Mr. Crabbit’s office and handed in my receipt. He was not impressed that I’d managed to spend the entire sum he’d given me.

“Two daguerreotypes at a pound a piece? A pound! Would one have not sufficed?”

“I sneezed during the first attempt and spoiled it, sir.”

“Costly sneeze! Well, what are you standing there for, boy? I have your receipt; now be about your business.”

“Sir, may I have my per diem, please? I’ve a feeling I’ll be needing it tonight.” If I was lucky enough to survive.

Mr. Crabbit sighed and dug out his petty cash tin. “Don’t think it goes unnoticed what you’ve been spending this money on,” he warned me. “Expensive pocket diaries and luxury photographic portraits. And the number of pencils you get through! Here. Seven shillings and sixpence. Now, on no account forget the—”

“The receipts. Yes, sir. Sir?”

“Well?”

“Take a look at this paper, if you please, sir.” I showed him the back of Miss Penelope’s note. “Do we keep anything like this in stock? I just need one or two sheets, so it seems a waste to go out and buy a whole ream of it.” That got him.

“I sincerely doubt you could buy such a thing. This paper’s yellowed with age. But I may have something here that will serve,” he said, wrestling in the bottom drawer of his desk. God bless misers and hoarders.

“Perfect!” I said, as he handed me exactly two sheets. “Now, I wonder if I can impose upon you for an envelope, a pen, and a drop of blue-black ink?”

“Would you care to use my desk while you’re at it?”