Michael Gallagher's Blog - Posts Tagged "serialization"

Gooseberry: Chapter One

London. Monday, January 19th, 1852

London. Monday, January 19th, 1852George and George, the other two office boys at Mr. Bruff’s law firm, sat snoring beside me on the bench, the victims of over-indulging on a plate of chops for their lunch. I gave the closer George a hefty nudge with my hip to try to claim back my fair share of the space. He came to for just a moment, blinked his eyes wearily, and then adjusted his hulking frame so that I had even less room than before.

Mr. Bruff’s office door swung open. Mr. Bruff came out and stood there contemplating the three of us. The look on his face suggested that he didn’t much care for what he saw.

“Gooseberry, with me,” he said, and, closing the door behind him, made directly for the stairs. I leaped up and padded along after him.

“The local chophouse again?” he inquired, as we exited the building together into a cold and foggy Gray’s Inn Square.

I nodded.

“Gooseberry, kindly inform George and George that from now on their favorite chophouse is officially off-limits.”

I don’t object to Mr. Bruff calling me Gooseberry, though I would have you know that it is not my real name. It’s a name that’s been given to me by one of Mr. Bruff’s clerks on account of my eyes. They bulge. At least, that’s what this clerk delights in telling me almost every single day. Naturally I can’t help them bulging any more than I can help being blessed with brains, and blessed with brains I am—to a far greater degree than either of the Georges, or that fool of a clerk, come to that.

I hasten to add, lest I later appear anything but entirely truthful on the subject, that having brains is not the only talent of which I am possessed, nor is Gooseberry my only nickname, which I’m sure will become clear in good time.

Mr. Bruff spotted a passing cab and put his hand out to hail it. As it pulled to a halt beside us, he directed the driver to an address in Montagu Square. I recognized the address as that of his close friend and client, Mr. Franklin Blake—Member of Parliament—a man to whom I have had the privilege of being useful in the past. I gripped the handrail to haul myself up to my usual seat beside the driver, but Mr. Bruff clasped me by the wrist and informed me that today he required my presence in the carriage. “There is a matter,” he said, “that I wish to discuss.”

Despite the ominous words, Mr. Bruff remained silent as the cab pulled away from the curb. It wasn’t until after we’d traded High Holborn for that long stretch of road that is Oxford Street that he finally opened his mouth to speak.

“Octavius,” he said, using my proper name for a change—a name which translates from Latin as ‘the eighth child’; not that I am the eighth, you understand, I’m actually the first—“do you recall how we met?”

“I do, sir, I do,” I replied, “although it’s a good six years ago now.”

“It was a day not unlike today,” he reminisced, “thoroughly miserable and wet. I was in Regent Street attending to a small matter of business when I observed a young lad loitering on a corner—a barefoot urchin trembling in the rain, his toes turning blue from the cold.”

Mr. Bruff does like to over-sentimentalize our meeting. I imagine it helps him justify the choice he made that day. But don’t be fooled by his sweeping sentimentality. This image he was painting hadn’t prevented him from grabbing me by the scruff of the neck, just as I was about to remove my hand from a gentleman’s pocket—with the gentleman’s wallet attached. When I tactfully pointed this out to him in the cab, he immediately began to bluster:

“I had every right to march you straight in front of a magistrate, Gooseberry! Instead I chose to take pity on a young, shivering ragamuffin and offer him a position as my office boy! Can’t you be grateful for that?”

I was grateful to him for getting me out of the Life, and I told him so—before he decided to clip me round the ear. But there was more to this story than he was aware, for I’d never got around to sharing it with him. He had always assumed I was barefoot because I was poor, but that just wasn’t so. I was barefoot because one of my trusty colleagues had stolen the boots off my feet while I slept. They say there’s no honor amongst thieves, and they’re right. It was only because of this temporary state of bootlessness that the old man had been able to nab me that day, for I guarantee you, at the age of eight—with my boots on—there was no swifter, slipperier pickpocket in all of London than yours truly, Octavius Guy.

It’s what Mr. Bruff might term ‘an irony’ (a word which he assures me has everything to do with the jesting of Fate and nothing to do with scrap metal), for my lack of boots was not just my downfall. When the lawyer took pity on my poor freezing feet, it also became my salvation.

“Gooseberry, over the years you have proved yourself trustworthy, resourceful and loyal,” Mr. Bruff went on, his wistful smile returning, “and in return I have kept your former profession a secret from employees and clients alike. But today, Octavius, for the greater good, it may become necessary to divulge its nature.”

“To Mr. Blake?”

Mr. Bruff grunted.

“Sir, have I done something wrong?”

“No, not at all. It’s quite the opposite, in fact. Mr. Blake’s summons was uncharacteristically vague, but the few details it gave made me think that your specialist knowledge might come in handy.”

“How so?” I asked, but Mr. Bruff would say no more, preferring not to speculate until he had all the facts at his disposal. I gazed out the window. We were passing by Hyde Park and the rain was billowing about us in sheets. I tried peering into the distance to see if anything remained of the Crystal Palace, where the Great Exhibition had been held the previous year. I couldn’t make out so much as a dickey-bird. Perhaps they’d already dismantled it. It set me thinking: what had they done with all those millions of panes of glass?

It was Samuel, the footman, who answered the door to us at Montagu Square. I’d met Samuel before on several occasions, just as I’d met most of Mr. Blake’s household. He took charge of Mr. Bruff’s cane and hat (though he pointedly ignored mine, obliging me to keep hold of it myself), and ushered us into the library where the family had gathered.

What a mournful sight! In the middle of the room sat a small, elderly lady, unknown to me, who was working on a piece of embroidery—or rather not working on it, for each time she inserted the needle, her fingers would shake and she’d burst into tears. Young Mrs. Blake was on her knees at her side, her arms around her, trying in vain to comfort her as best she could.

Mrs. Blake’s maid, Miss Penelope, stood in the background, miserably wringing her hands in distress. It shocked me to see the complete disarray that both her locks and her clothing were in, for she was a young woman who normally took such pride in her appearance. Wisps of red hair hung loose about her face, as if she’d just been in a cat fight, and her blouse, which had been wrenched loose from her skirts, was ripped in at least three separate places.

Miss Penelope’s father, the ancient Mr. Betteredge—the family’s faithful steward—lay slumped in a chair by the flickering fire with a tattered old book clutched to his chest. I couldn’t be certain whether he was awake or asleep, for, ranked as I was as being little better than a tradesman, I was obliged to keep my distance when Mr. Bruff stepped forward to greet the family.

Mr. Blake, who’d been pacing listlessly about the room, grasped my employer’s hand and shook it. But it was his wife—and not he—who quickly took charge of the interview.

“Mr. Bruff, thank you for coming on such short notice,” she said, as she rose to her feet. “You will remember my aunt, Mrs. Merridew?”

“A pleasure as always, madam.” My employer smiled and gave a stately little bow.

The woman acknowledged it with a nod of her head. “I had hoped to quieten my mind by occupying myself with something trivial and mundane,” she said, staring down at the embroidery in her hand, “but it doesn’t seem to be working.”

With this she broke into a fit of sobs.

“My aunt has had a rather nasty shock,” Mrs. Blake explained. “Actually, apart from my husband—who did not accompany us this morning—we all have.” She glanced meaningfully over her shoulder at Miss Penelope, who blinked, bit her lip, and wrung her hands again.

“My dear, as your trusted friend and your lawyer, I suggest that you start at the beginning and tell me everything that’s happened.”

“Then perhaps we should sit down.”

Mr. Blake drew up chairs for them both and then resumed his pacing.

“Mr. Bruff, do you consider me an imaginative woman?”

My employer gave the question some careful thought before he hazarded a reply. “Miss Rachel, I have known you your entire life. If you ask whether I believe you possess an active imagination, then I would say, yes, you display a healthy and inquisitive one; a match for any man’s. But if you ask whether I think you imagine things, then, no. Lawyer that I am, I would still take your word over others, were all the evidence on God’s good earth to speak against you.”

Mrs. Blake seemed pleased with this answer and rewarded him with a faint smile.

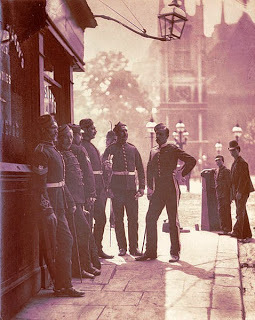

“Then I shall begin where I believe this mystery begins,” she said, “even though I have no proof that it does. Last week we happened to receive an unusual number of nuisance callers. When Samuel, our footman, answered the door he would find an old beggar woman on the doorstep, with sprigs of winter heather for sale—or one of those preposterous suppliers of religious tracts—or a man who grinds knives for a living. It became ridiculous, quite ridiculous, and really rather tiresome. Occasionally he would even respond to the bell to find nobody there at all!”

“Oh, my!” exclaimed Mrs. Merridew. “How very odd! We had the same trouble at Portland Place…just before my footman gave his notice. I wondered if the bothersome callers had anything to do with his leaving, for I have no doubt they played havoc as much on his nerves as they did mine, so I asked him straight out, but he said not; rather that he was obliged to attend to his sick brother.”

“You had nuisance callers too? But, Aunt Merridew, why didn’t you mention this earlier?”

“I didn’t think it important, dear.”

“Surely it cannot be a coincidence! Aunt, has anything else out of the ordinary happened to you recently? For instance, have any of your windows been broken?”

“Oh, my…not that I can think of. Why do you ask?”

“Because last Friday morning Penelope discovered a broken pane of glass in the servants’ quarters.”

Mr. Bruff sat forward with a look of concern. “You experienced a burglary?”

Mrs. Blake shook her head. “Apparently not, Mr. Bruff, for when I had Betteredge check the inventory nothing appeared to be missing.”

“An accident, then?”

“Perhaps.” She sounded doubtful. “Though if so, I’m surprised that no one has come forward to own up to it. It was never in my mother’s nature to dock the servants’ wages for breakages, nor is it in mine.”

“How very curious.”

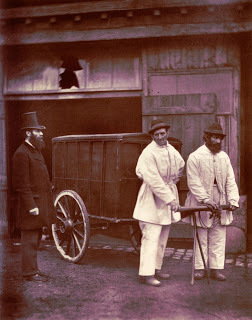

“Curious indeed. Which brings us to the events of today. I had plans to attend an early luncheon with my aunt at her house in Portland Place, and I decided to take Julia, my baby daughter, along with me. I asked Penelope to accompany us, to look after her on the way there. Then Betteredge insisted on coming, with umbrellas for us all in case it rained.”

On hearing his name, the old servant sat bolt upright in his chair.

“And rain it might have, Miss Rachel,” he spluttered, “and rain it finally did. But, in truth, that is not the reason I requested to come.”

“No?”

“No!” With trembling hands he held out the book he’d been clutching. His forehead was fevered with sweat. “Just this morning I opened my copy of Robinson Crusoe—the one your dear late mother presented me with on the occasion of what was to be her final birthday—and what should I find there?”

He riffled through its dog-eared pages, located the passage he was looking for, and then solemnly began to read aloud: “‘It was the howling and yelling of those hellish creatures; and, on a sudden, we perceived two or three troops of wolves on our left, one behind us, and one on our front, so that we seemed to be surrounded with them!’

“You see? You see?” he cried. “As I live by bread, miss, I knew in my heart that these self-same perils I had been directed to in this book were fated to befall you today! It was my sworn duty to come with you; no more, no less. My duty!”

An uncomfortable silence descended on the company, during which even Mr. Blake stopped his pacing.

“Robinson Crusoe? What has Robinson Crusoe to do with this?” my employer demanded.

A shorter silence ensued, broken this time by Mr. Blake. “The good Betteredge firmly places his trust in Dafoe to steer him safely through life,” he explained.

“I do, sir, I do!” Mr. Betteredge came back, and with such passion in his voice that I wondered whether he had been drinking. “And you would be wise to, too, Mr. Bruff, lawyer though you may be!”

Lawyer that he is, my employer is not easily lost for words, but in this case he was rendered speechless. He finally responded with a shake of his head and turned his attention back to Mrs. Blake.

“Mrs. Blake, will you please continue?”

She nodded and took a deep breath. “It was a perfectly pleasant meal, Mr. Bruff, but then I noticed that the weather was taking a turn for the worse. I rose to leave. My aunt had pledged to come with us, as she wished to consult my husband over the hiring of a replacement footman. I suggested that she, Julia, and I take a cab home, but Aunt Merridew refused to hear of it, saying she would prefer to walk while the rain held off. We strolled back along Wigmore Street, and were just passing Portman Square when my aunt spied a woman selling flowers at the side of the road.

“‘Let me stop and buy a nosegay,’ she begged, and opened up her handbag to retrieve her purse. Suddenly a shriek rent the air, and then another and another, as we found ourselves surrounded by a pack of howling children, lunging and pecking at us from every side.

“I don’t know what would have become of us were it not for Penelope’s quick thinking. She pushed me and Aunt Merridew back against the railings, thrust the baby into my arms, snatched one of her father’s umbrellas and began to beat those monsters off, even as she shielded us with her body. It was so frightening! Their hands went darting everywhere—everywhere, all over us—though it was Penelope who bore the brunt of their attack. Their wailing, animal screeches finally brought people running, but the children saw them coming and swiftly scattered. By the time our rescuers got there not one of them remained.

“We were all understandably shaken, though no one was actually hurt except Penelope here. The men who had come to our aid kindly saw us home. I had Cook clean and bathe Penelope’s wounds, and asked Betteredge to make us all a restorative drink.”

Everyone looked towards the fireplace. Exhausted by his earlier outburst, the steward had fallen fast asleep.

“It was only while we were recovering,” Mrs. Blake continued, “that I realized the attack might have been purposely staged, perhaps to try to rob us, so we all checked our capes and belongings to see if anything had been taken.”

“And?”

“Well, this is the most perplexing part of all, Mr. Bruff. Nothing had been taken.”

The lawyer’s eyes narrowed. “But Mr. Blake’s summons…I was led to believe—”

“I repeat, nothing had been taken. But something had most definitely been left.”

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 11th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Do let me know! I’d love your feedback. Please use the comment box below.

Published on July 04, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Two

“Left?”

“Left?”“Inserted into Aunt Merridew’s bag. Here, see for yourself.”

Mrs. Blake rose and walked over to the table. She retrieved a small palm-sized leather case, not unlike a notebook, and carried it back to my employer.

“Open it.”

Mr. Bruff turned the case over in his hands, found the tiny clasp at the side, and unlatched it. All I could see was the occasional glint from where I was standing, but even so I was ninety-nine percent certain that what he was holding was a daguerreotype—a photograph on a sheet of silvered copper, mounted behind glass in a plush-lined case. There was a time not so long ago when I would have hopped up on a chair to get a better look. I should like to be able to tell you that I have since learned the value of patience, but it wouldn’t be true. What I have learned is that the upper classes don’t appreciate your boots on their furniture, no matter how pressing your needs may be.

“So,” my employer summed up, having studied the photograph at some length, “both you and your aunt were subjected to nuisance callers; a pane of glass was found broken in the servants’ quarters; and then today a gang of hooligans attacked you in broad daylight—not to rob you of anything, but to place this about your aunt’s person?”

“It sounds incredible, Mr. Bruff, I grant you, but how else can that daguerreotype have found its way into my aunt’s handbag?”

“Mrs. Merridew, do you recognize either of the people in this photograph?”

“No, Mr. Bruff, they’re perfect strangers.”

“Mrs. Blake?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t.”

“Mr. Blake?”

“I’ve never seen either of them in my life. But observe, sir—the boy. The tone of his skin…his manner of dress. Though the man’s a Caucasian—and most probably English, judging by the cut of his suit—the boy is an Indian, is he not?”

Mr. Bruff nodded. “And an extremely wealthy one, by the look of it.” He peered at the daguerreotype again. “It’s a very formal portrait,” he remarked, “carefully composed and beautifully rendered. It’s not the work of an amateur. And yet, notice the boy’s scarred right eye; there’s been no attempt to disguise the lad’s disfigurement.”

“You don’t suppose that this could have anything to do with that accursed Moonstone diamond, do you? I had hoped I’d put that business behind me for good.”

“Because the lad’s Indian? No, Mr. Blake, your investigations were faultless. I’m sure the boy’s race is purely a coincidence.”

“Then perhaps someone’s trying to discredit me. The political party I serve may be in opposition at the moment, but, trust me, sir, things are about to change. This unholy coalition—which would take its grain from other countries instead of from our own worthy farmers—they’re on their way out, and they know it! I wouldn’t put it past them to pull some dastardly stunt to embarrass us first.”

“If they were trying to embarrass you, Franklin, why give the photograph to my aunt?” Mrs. Blake inquired of her husband. “Why not to you?”

“A very good question,” said Mr. Bruff. “But what I’d like to know is why a street gang would go to these extraordinary lengths to do such a thing? That is the crux of this matter. What we need is someone versed in their ways who might help us unravel this puzzle. Gooseberry, I think the time has come for you to tell us what you can.”

I stepped forward, expecting to be quizzed about my credentials. Instead I found myself being fussed over handsomely by Mr. Blake.

“Upon my word! Gooseberry!” he cried, shaking my hand and slapping me on the back. “I didn’t see you there!”

Mr. Bruff quickly intervened and directed me to business. “What is your opinion,” he asked, “of all that you’ve heard here today?”

“First, can I please see the daguerreotype?”

“‘May I see the daguerreotype’,” Mr. Bruff corrected me, as he handed over the picture.

If anything it was even grander than I had imagined it: a portrait of a man and a boy seated side by side in chairs that could almost pass for thrones, in what can only be described as an opulently—and quite exotically—furnished room.

“Gooseberry, your contribution, please.”

I passed the picture back and turned to address Mrs. Blake. “Gangs such as you describe, miss, work in two particular ways, both of which depend on creating as much chaos and confusion as possible.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Well, to dazzle people’s senses, miss. It makes them slow to react.”

“I see. Go on.”

“In the first, the gang runs in, causes a commotion, grabs what it is they’re after, then scatters as soon as they can. It requires a little planning, but hardly any skill, which is why the second way is infinitely more satisfying—”

“Satisfying?”

As I considered what my response should be to this, I placed my hat, which their footman Samuel had obliged me to keep hold of, down on the nearest chair, earning myself a look of reproach from Miss Penelope, Mrs. Blake’s maid.

“Well, intellectually satisfying, if you like, miss. While the gang is wreaking chaos and everyone’s attention is diverted, somebody else—someone on the spot who seems quite unconnected to any of the troublemakers—he stealthily slips the desired items inside his jacket—an overly-large jacket like the one I’m wearing now.” Or down his trousers. Or under his hat. “Once the gang has scarpered, that person calmly walks away, taking his booty with him.” While lifting wallet after wallet as he saunters through the crowd. Ah, my glory days, indeed. “Later the gang meets up at some predetermined location to share out their spoils—in accordance with each person’s rank, of course, and the amount of risk each person took.” Well, the spoils that they know about, that is.

Mrs. Blake looked at me thoughtfully and asked, “Gooseberry, how do you know all of this?”

The time had come to own up to my past. I’d been thinking about how best to present it, and it seemed to me that what was called for here was a judicious mixture of remorse, honesty, and diffidence.

“Though it shames me to say it,” remorse, “there was no swifter, slipperier pickpocket in all of London,” honesty, “than…well, me, miss—your humble servant—Octavius Guy.” Diffidence dispensed in a generous measure.

Mrs. Blake burst out laughing.

“Please, Mrs. Blake, it’s true.”

“Gooseberry, you really mustn’t joke.”

“I’m not joking, miss.”

“I don’t believe it for a moment!”

Mr. Bruff gave a cautious lawyer’s cough that managed to get everyone’s attention. “He’s telling the truth,” he said quietly, and shot Mrs. Blake a meaningful look.

“But this is Gooseberry we’re talking about! Our Gooseberry! He’s no thief!”

“If he’s telling us the truth, then I think he should be made to prove it,” said Mr. Blake, a mischievous grin breaking out on his face that even his thick, black beard couldn’t hide. “I propose a challenge. Gooseberry, come and try to pick my pocket!”

“Please, sir—I don’t want to pick your pocket.”

“But I insist,” he said, stepping closer and closer till there was barely a foot between us. With everyone watching (save for the good Mr. Bruff, whose features plainly registered his disapproval), Mr. Blake leaned forward so that our noses were practically touching. On reflex, I found myself stumbling backwards, a move that Mr. Blake took as a sign of defeat.

“So much for the swiftest, slipperiest pickpocket in all of London,” he laughed, and, like a performer taking his curtain call, turned and bowed deeply to his wife.

“Franklin, look,” she advised him, pointing her finger at me.

Mr. Blake looked. His mouth dropped open. He stared, blinking in amazement at the silver cigarette case in my hand.

He patted the vicinity of his jacket’s left inside-breast pocket, feeling for something that was no longer there. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Mrs. Blake’s aunt place her embroidery in her handbag and hug the handbag to her chest. My heart suddenly crumpled; I should have realized how people might not take too kindly to discovering a thief in their midst.

Mr. Blake regarded me solemnly for several long seconds. “How did you manage it?” he asked at last. “I didn’t feel a thing. Not a thing.”

“It’s just a skill I have,” I replied, preparing to duck his blows as I handed him back his case.

“During my travels in the East, five men attempted to pick my pocket—and five men ended up regretting it. But you! That wasn’t skill, young man; it was art! By all that’s wondrous, you’re going to have to teach me how you did that!”

“Teach you to steal things? No, Mr. Blake! It wouldn’t be right.”

Mrs. Blake arched her eyebrow at the both of us and said, “I’m glad to see that one of you is old enough and wise enough to appreciate right from wrong. So, tell me, Gooseberry, expert pickpocket and moral compass that your are, in your opinion, what do you think happened to us today?”

“It’s very hard to say, miss. I can’t begin to fathom why a gang would want to plant something on you, especially if it’s something that holds no apparent meaning for any of you. However, from what you’ve told me, I’m fairly sure that the method they employed was the second one I outlined. Your attackers were simply the distraction. Somebody else—someone on the spot, seemingly unconnected—was responsible for slipping that photograph into your aunt’s handbag.”

“But who?” she asked. “The only people present were my aunt, myself, Penelope and her father, and my baby daughter Julia. You surely don’t suggest that one of us did it?”

“I beg your pardon, miss, but you’re mistaken.”

“Gooseberry, I know who was there. There was nobody else, believe me.”

“But there was, miss. There was the flower girl; the one selling flowers by the side of the road. Did anyone see where she went to?”

Mrs. Blake stared. “She was with us, I think. I really can’t remember. Aunt Merridew, do you recall?”

“I was too terrified to notice, dear. I expect my nerves will be shattered for weeks.”

“Penelope, what about you?”

“I’m sorry, Miss Rachel,” the maid responded shakily, speaking for the first time since we’d entered the room. “I was too busy battling off those horrid beasts of children. I have no idea where the woman went.”

Mrs. Blake glanced across the room to where her faithful retainer lay dozing. Choosing not to wake the old man, she turned her attention back to me.

“So you think it was the woman selling flowers?” she said.

“I certainly think it’s possible, miss. I can’t see who else it might be. Do you think you can you describe her?”

Mrs. Blake frowned. “She was a big girl. I remember that.”

“Very big. And certainly no beauty,” added her aunt. “A poor, ungainly thing, crouching on her haunches beside her basket. I recall seeing her pock-marked face and taking pity on her, which is why I insisted that we stop to buy a posy.”

“I don’t remember pock-marks,” Miss Penelope cut in, apologizing for the interruption, “but I have to say she wasn’t all that big.” On finding herself the center of attention, she quickly looked away. A moment later she was wringing her hands again.

“Of course, I could be wrong,” Mrs. Merridew admitted, “but I honestly don’t think that I am. You see, although I couldn’t say why, I was truly fascinated by the creature. There was something utterly compelling about her state of wretchedness.”

Miss Penelope’s objection aside, a picture was already beginning to form in my mind. “What color was her hair?” I asked. “And how was she dressed?”

“Coarse, dark brown shoulder-length hair, parted in the middle and pulled back into a bun,” the aunt reeled off excitedly, her distrust of me temporarily forgotten. “Yellow cap and ribbons instead of the usual headscarf affair. A light gray blouse, which hung from her shoulders like a sack, and a tattered, dark gray skirt. A filthy red shawl, one end of which she held across her mouth, I imagine to try to hide her scars.”

“I remember the shawl,” Mrs. Blake agreed, her nose wrinkling up at the thought. “I wouldn’t put it anywhere near my lips.”

“Broad-shouldered? Arms like hams?”

“Why, yes.”

“And softly spoken?”

“So softly spoken I could hardly make out anything she said,” Mrs. Blake replied. “Aunt Merridew had to ask the price of the posy several times.”

The old lady nodded in agreement.

“Kept her eyes averted? Never once looked at you directly?”

“Gooseberry? Do you know her?”

I was almost positive that I did, back in the Life. Everyone knew her—Big Bertha, they called her. Bertha, whose real name was Bert.

I can’t rightly say whether it was out of a sense of propriety or a sense of embarrassment that I chose to keep the delicate nature of Bertha’s gender to myself. Not that it mattered either way; the important thing was that we now had a lead.

Mr. Bruff wound up the meeting by promising the Blakes that I would follow up on it the very next day. He also requested they entrust him with the daguerreotype, as he had an idea of his own he wished to pursue.

“May I please take another look at it,” I asked on the cab journey back, remembering just in time his strictures over the use of the verbs can and may. He pulled it out and handed it to me, but I was sorely disappointed. I had hoped to divine some link between the people in the photograph and Big Bertha. But study it as I might, nothing came to mind.

The streets were deserted and bracingly chilly as I made my way homeward up the Gray’s Inn Road, stopping only to collect a couple of eel pies and some macaroons from the eating-house on the way. Turning east, I set off along the New Road, past the site of the old smallpox hospital. They’re in the process of building a railway terminus there, which locals claim will bring train-loads of people from Scotland—though why any of them would want to visit my own little part of the world was a complete mystery to me. But, ah, the wonders of living in the Golden Age of Steam, eh? Board a train in the morning in Edinburgh and disembark in the evening at King’s Cross!

I have lodgings off the Caledonian Road, or the ‘Cally Road’ as it’s commonly called. There’s talk of them erecting a cattle market up by the prison, but till then the Cally remains the principal route into Smithfield for every drover herding their cattle from the north. The area’s much quieter at night, mind, without a single cow’s lowing to be heard; so quiet in fact that, with your window open, you can hear the lapping of the nearby canal and the gentle thud of the coal barges moored up together in pairs.

That night, as I rounded the corner, I saw that my window was closed, but a flicker of light in the glass warned me someone was already home. I ran up the stairs two at a time and silently pushed open the door.

“Octavius!” came the shout of pure joy from inside.

A small, lithe figure of a boy cannonballed into me from halfway across the room, gripping me so tightly that I nearly let go of the pies. My younger brother Julius.

“Did you have a good day today, Octavius? Did you get to do anything interesting? We sold all the fish on the stall by four o’clock, so I got to come home early. I came straight here, Octavius, just like you said to do; I didn’t hang round. Did you bring us anything for supper? It doesn’t matter if you didn’t because I had a hot potato for my lunch.”

I wriggled out of his grasp and, like a conjurer, made a show of presenting him with the pies. His eyes lit up like beacons.

“Eel pies?” he cried, dancing with excitement. “You know they’re my favorite!”

We set the table and ate, both of us savoring for as long as we could the rich jellied meat in its crust. Afterwards I scoured the plates with cold ashes from the stove while Julius collected his supply of scrap paper—scavenged from the waste bins at the office—and then proudly retrieved his treasured pencil from the shelf.

“What word will we do tonight?” he asked.

“I don’t know…what word do you think will be useful?” This was a routine we repeated every night.

“How about ‘sprats’?” he suggested, after a moment’s thought. “We had sprats on the stall today.”

I carefully wrote down the word for him and he began to copy it. I sat and watched him as he wrote, his face set hard with concentration and his small, pink tongue sticking out. I could have spent a lifetime watching him that way, but eventually the candle burned too low.

We were up the next day before dawn, for we both had early starts; Julius off to his fish stall in Old Street, and me on my hunt to find Bertha. Bertha was a creature of habit, so I knew where he’d probably be, the day in question being a Tuesday. The flower market at Covent Garden.

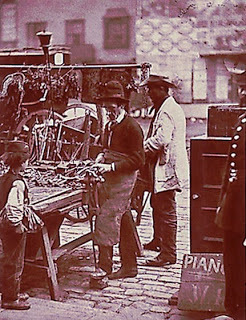

The sun was still struggling to rise as I made my way down Drury Lane and into Long Acre, dodging wagons loaded to the brim with fresh produce. Although it was early, the piazza was crowded and the streets leading into it jammed. I passed stalls stacked high with cauliflowers and cabbages, swerving to avoid the bustling porters. Did my fingers itch to perform as they once had? No. But I did wonder if Mr. Bruff had given any thought to what he was asking of me, requiring me, as it did, to rub shoulders again with my former partners from the Life.

If I remembered correctly, Bertha’s pitch was on the west side of the square, at the rear of the Actors’ Church. Six years may have passed since I’d last seen him, but if I knew Bertha, he’d rather kill than give up such a desirable site.

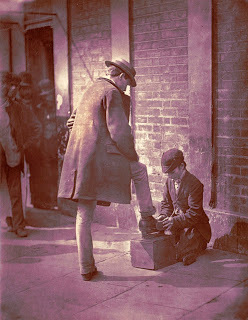

And I was right. As I turned the corner, there he was. Dressed in gray and draped in his dirty red cape, his head bowed low to show off the bright yellow cap and ribbons he wore, he was squatting on the pavement and looking quite ungainly as he sorted through his basket full of flowers.

He must have seen my boots as I approached, for all at once he pulled his shawl across his mouth, bowed his head a little lower, and quietly began to mumble in a deep, hoarse whisper: “Buy a nice posy from a poor, honest woman, sir? Or a bouquet for your sweet, faithful wife?”

“Hello, Bertha.”

Big Bertha’s face shot up. “Oh, my Gawd, as I live and breathe!” he squawked. “I’d recognize those bulging big ogles anywhere! It’s you. It’s young Octopus, back from the dead or Van Diemen’s Land!”

Octopus. My other nickname.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 18th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or still too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Do let me know! A big thank you to Lara and Alice who have sent me feedback, but I’d love your feedback, too. Please use the comment box below.

Published on July 11, 2014 06:10

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Three

I like to think that I am a man of the world—or, to be more accurate, having attained the grand age of fourteen, I am now two-thirds of a man of the world—and I would have you know that in my time I have seen both men dressed as women and women dressed as men. Of these, some have been most convincing. Many have been less so. Bertha, I’m afraid, didn’t even make it into this category. There was nothing feminine or effeminate about him whatsoever. In a sense he was simply a big, jowly bloke in a dress. No wonder Mrs. Blake’s aunt had been fascinated by him. I’m sure she’d never seen anything like him in her life.

I like to think that I am a man of the world—or, to be more accurate, having attained the grand age of fourteen, I am now two-thirds of a man of the world—and I would have you know that in my time I have seen both men dressed as women and women dressed as men. Of these, some have been most convincing. Many have been less so. Bertha, I’m afraid, didn’t even make it into this category. There was nothing feminine or effeminate about him whatsoever. In a sense he was simply a big, jowly bloke in a dress. No wonder Mrs. Blake’s aunt had been fascinated by him. I’m sure she’d never seen anything like him in her life.“Look at you!” he cried, rubbing his eyes as if he’d seen a ghost. “My, ain’t you grown! Why, you’re almost a fully-fledged omi,” he said, meaning ‘man’ in palari, the actors’ slang he liked to use. “So where the hell you been, then?”

“Well, I wasn’t sent to some Australian penal colony, if that’s what you imagined.”

He blinked. “Wot, then?”

“I simply needed a break from the Life, that’s all.”

“But where d’you take yourself off to? Ain’t no one just disappears like that.”

No? I’d managed it pretty well up until now.

“I went to live in Edinburgh,” I lied.

“Edinbra?” He considered this carefully. “Ain’t that somewhere up norf?”

By the time I agreed that it was, he’d already begun to lose interest. Instead he was employing his critical eye to give me a quick once-over.

“Well, well, well! You’ve grown to be quite a looker, ’aven’t ya? You seeing anyone, then? If not, I’d be more than happy to—”

“No, Bertha, I’m really flattered, truly I am, but…”

“No, no, no! I ain’t talking about me!” He wagged a fleshy finger in my face. “You got to learn to lower those sights of yours, lad. No, I was trying to tell you ’bout this matrimonial bureau wot I runs now—strictly a sideline, o’ course. A young omi such as yourself, I could get you fixed up in a jiffy.”

“But what if I don’t want to be fixed up?”

He wasn’t listening. Something or someone had caught his attention on the other side of the piazza.

“’Ere, Florrie, get those scrawny little hips over ’ere! Octopus, I want you to meet Florrie. Florrie, this here’s Octopus.”

“Octopus?” The girl Bertha had summoned was gawking shamelessly at my eyes. “That’s an unusual name,” she said. She was dressed, as most of the market girls were, in a blouse and skirt, with a shawl draped over her shoulders. Her blonde hair was pulled back from her face and tied up with a black velvet band.

“Forget those bona big ogles, girl,” chortled Bertha, referring to my eyes. “It’s his lills you ought to be worried about. ’E’s got eight of ’em.”

“Eight?” Florrie’s gaze dropped to my hands in a panic. She gave a sigh of relief when she saw I only had two.

“This young omi used to troll through the streets lifting wallets left, right, and center—just like an octopus would if it ’ad any real appreciation of money! You keep your eye on him, girl, or his lills will be all over you in no time.” The girl blushed as Bertha gave a deep throaty chuckle. “First assignation’s free,” he continued, now addressing me, “it’s the second that’ll cost ya; strictly no third unless it’s a wedding!” Bertha gave me a big, theatrical wink. “Got to make it look proper, see; I won’t have no one thinking I’m procuring. Me, I’m a respectable woman!”

Florrie and I regarded each other in a state of nervous embarrassment. She looked almost alarmed; I’m sure I did too.

“Young people these days!” griped Bertha. “No sense of romance! Go on, Florrie, if he ain’t going to kiss ya, you may as well give us a hand with these posies.”

The two of them knelt on the pavement and began binding stems with green twine.

“So how’s the flower business going?” I asked. “Everything in the garden blooming?”

“Mustn’t grumble, mustn’t grumble,” he replied. “’Ere, wot do you think of my new line of patter?” He bowed his head, pulled his shawl across his mouth, and started whispering the same catchphrase he’d whispered before: “Buy a nice posy from a poor, honest woman, sir? Or a bouquet for your sweet, faithful wife?”

“It’s good. Really good.” It was a definite improvement on the one I remembered: ‘Varder me dolly flowers, sir.’—meaning, look at my pretty flowers—‘Get ’em quick before they die.’

Bertha grinned.

“I hear you were over on Wigmore Street yesterday,” I said.

The grin faded. “Oh? And where d’you hear that?”

“Some friends of mine were accosted…by a gang. The odd thing is, when I asked them about it, they managed to describe you perfectly.”

“Friends of yours, eh?”

“People I care about, yes.”

He took a moment to digest this. “Shame,” he said. “Seems like a poor, decent woman can’t go nowhere no more wiffout being set on by ruffians.”

“Wigmore Street’s a bit outside your territory, Bertha. And that got me thinking. This job had to be special—planned to order by someone much higher up.”

“Well, I wouldn’t know, ’cos I wasn’t there!” he bawled.

We eyed each other warily, like a pair of fractious circus tigers, until Bertha finally cracked and looked away. It wasn’t stalemate yet, however, for I still had one move left to me.

“So you weren’t the one who slipped the daguerreotype in the old lady’s bag?” I said.

For the second time in twenty minutes, Bertha’s pock-marked face shot up. Florrie, who’d been watching our little exchange with increasing discomfort, rose to her feet and announced she was leaving.

“No, you stay right where you are,” Bertha growled at her, even though he was glaring at me. “It’s young Octopus here wot needs to leave. Go on, Octopus—” And here he bellowed a two-word Anglo-Saxon phrase at me, causing everyone in the square to look.

I beat a tactical retreat into the bustling piazza, and hid myself behind a barrow-load of celery. I’d purposely kicked the hornets’ nest, and I wanted to see what Bertha would do next. I didn’t have to wait long. Leaving his stall in Florrie’s care, he threw his shawl over his shoulders and set off at a cracking pace down King Street. Despite the considerable number of pedestrians, he made an easy target to follow. His yellow cap and ribbons bobbed a good six inches above most of the heads in the crowd.

At the corner he turned north, as if heading towards Long Acre, but then pulled up short outside a public house. I knew the pub, but only by reputation: they regularly staged bare-knuckled prize fights there. It was the Lamb and Flag, referred to hereabouts as the Bucket of Blood. After a moment’s hesitation, Bertha went inside.

I crept up to the windows and peered in. Though the hour was still early, business was brisk, as it tends to be for any pub on a market day. I scoured the room, but there was no sign of Bertha. I stepped back a little and gazed up at the windows above. Was one of the old crew up there, holding court in a private suite? Perhaps even Ned himself, if he still happened to be in charge. How would he react when he heard I was back, I wondered?

It seemed as if I had a choice. Burst in and confront him, or whoever it was who was running things now—a strategy that hadn’t played so well with Bertha—or wait and see what would happen. I took a coin from my pocket and flipped it. Tails. Better to wait.

I returned to the corner and stood by the railings, watching and biding my time. Ten minutes passed, and then twenty. At last the door opened, and Bertha emerged.

I held my ground for a moment as he marched away, curious to see if anyone else would appear. When no one did, I sped off after him, just in time to see him cross the road into Bedford Street. At the Strand he turned left and began to head east, past Temple Bar into Fleet Street. The pavement here was not so crowded, so I could afford to fall back a little.

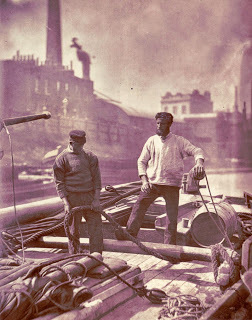

Still he trundled eastwards, past St. Paul’s, past London Bridge, then past the Tower. Now came the docks with their innumerable ships moored up in miniature cities. Gulls reeled and circled among the masts against the steel-gray, mid-morning sky. Surrounded by beer-bellied dockers, Bertha was in his element, lapping up the hoots and wolf whistles he’d started to attract.

Somewhere between the London Dock and the East London Dock, Bertha paused. He peered to his right, then took a road that led down towards the river. A few minutes later he made another quick turn, this time to his left. As I came round the corner, I saw that he’d reached his destination. He’d joined a small line of people queuing up outside an octagonal marble tower. As those in the queue were all dressed rather fashionably, Bertha stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. So did the tower, come to that. Being new, and built of pale gray marble, it seemed truly at odds with the neighboring warehouses, all of which had seen better days. Gradually the line grew shorter and Bertha vanished within.

I followed a minute or so later, in time to see him picking a fight with a man in a ticket booth. “But it’s only a penny!” I heard the chap saying, as I popped my head round the entrance.

“A penny’s a penny!” growled Bertha. “And I’m not some damned sightseer; I’m ’ere on business! Now bleedin’ well let me in!”

Grudgingly the fellow complied, operating the narrow brass turnstile to allow him to pass.

I made my way across the blue and white tiled floor and handed over my penny. The man still looked livid from his encounter with Bertha, so I was dreading asking for a receipt—a matter of some necessity for me, for Mr. Bruff’s clerk who handles the petty cash claims is a tyrant where receipts are concerned. But before I’d plucked up the courage to do so, the man pressed some kind of lever, and I was forcibly propelled through the turnstile gates and spat out on the other side. I suppose I could have knocked on the back door of the ticket booth, but even I have my pride. In front of me loomed a doorway. Without knowing quite what to expect, I squared my shoulders and stepped on through.

I found myself at the top a circular shaft, lit entirely by gaslight. A lengthy spiral staircase descended forty feet or so to a marble floor below. Here and there, there were landings to break the descent, hung with paintings of palaces and waterfalls. There was even the odd plaster statue or two. Ghostly organ music echoed up from the depths, Rule Britannia, The Marseillaise, and a number of other tunes that sounded stirring enough, though I couldn’t tell you what they were. Below me, I saw that Bertha had nearly reached the bottom of the stairs. I quickened up my pace; I didn’t want to lose him in the crowd.

He barely glanced at the sideshow attractions dotted about the room (‘Your Fortune Told’, ‘The Egyptian Rune Reader’, ‘The Monkey Answers All Your Questions’), and made directly for the pair of tunnel entrances that stood opposite the stairs. Choosing the right-hand one, he set off down it, with me still in hot pursuit.

The tunnel seemed to stretch for as far as the eye could see. Strategically positioned gas lamps lit the way, and every so often there was a gap in the wall that allowed access from one tunnel to the other. Stalls selling various lines of cheap goods were set up in each of these gaps, staffed in the main by pallid young women, with skin that was even paler than mine. Ahead of me, Bertha drew up in front of one such stall and began to examine the merchandise. As I huddled against the tunnel wall, I felt a drop of ice cold water hit the back of my neck and trickle its way down my collar. By now I had a very good idea where I was.

Bertha was on the move again. As I passed the stall where he’d stopped, I glanced down at the ribbons he’d been inspecting. Each had the words ‘Souvenir of the Thames Tunnel’ woven through it. I’d been right. Here I was in the world’s first sub-aquatic tunnel, well below the bed of the Thames, with ten thousand of tons of water pressing down on me!

My moment of reflection came at a cost. When I looked up, Bertha had vanished.

He couldn’t have gone far, I reasoned; my attention had wavered for a few seconds at most. I kept going in the direction he’d been heading. To my left was another gap, this time with a stall selling magic lantern slides. Twenty yards on, there was another, this one a coffee shop decked out with tables, nearly all of which were occupied. An eccentric-looking waiter in a costermonger’s jacket, stitched with rows of mother-of-pearl buttons, weaved his way between the tables delivering drinks and light refreshments. Bertha couldn’t have got any further than this.

I moved swiftly through the underwater coffee shop, searching amongst the faces, till I came out in the adjacent tunnel. I peered up and down. Bertha was nowhere to be seen. I retraced my steps back to the shaft, checking each of the stalls as I went. As impossible as it seemed, Bertha had given me the slip.

I loitered at the base of the stairs and watched the procession of people. I made a tour of the room, and examined the organ that was churning out music. Driven by steam, it somehow managed to play itself. I considered consulting the monkey, the one that ‘Answers All Your Questions’, for I had several that were puzzling me deeply. The problem was his method. Two nuts were placed on a board before him; one on a square that said ‘yes’, the other on a square that said ‘no’. The nut he chose first indicated his answer. Is Bertha still in the tunnel? Is Bertha still in the right-hand tunnel? At a penny a shot, and with only yes-or-no answers to guide me, it could cost a small fortune to locate Bertha this way. I took out a coin, but it wasn’t for the monkey. Should I stay or should I go? I flipped it.

Heads. Stay, then.

I wandered back to the coffee shop, took a seat, and ordered a piece of cake from the man in the button-clad jacket. Idly I wondered where he kept his supplies, for he was doing a roaring trade.

The afternoon wore on. I began to notice that nearly everything in the tunnel cost a penny. It was rather clever, really; for the price of a couple of nice, fat herrings anyone could buy a piece of tat to remind themselves of their time spent down here. I bought a candle at one stall and moved on to the next, which just happened to sell writing equipment. It was staffed by a young woman with bright auburn hair, whose mouth gaped open in an undisguised yawn. I couldn’t resist following her example, and gave a big yawn myself.

“Who buys these things?” I asked, as I browsed through the pencils and dip-pens laid out on the white marble counter-top, each stamped with the brand, ‘Souvenir of the Thames Tunnel’.

“Tourists,” she replied without enthusiasm.

“How much?” I asked, selecting a fine looking pencil for Julius. “No, don’t tell me. It’s a penny, right?” I saw her eyes roll towards the ceiling. “Oh, and may I have a receipt, please?” I added.

“A receipt for a penny?”

“If you would be so kind…?”

She threw me a look of pure hatred.

Before too long the music ground to a halt, and stewards began to herd everyone out. “Ladies and Gentlemen! The Tunnel is closing in fifteen minutes. Please make your way to the exits!”

I didn’t need to be told twice. I nipped up the stairs and was outside in a shot. Night had fallen, but it couldn’t have been late. I took shelter in a nearby doorway and watched as people emerged—first the patrons, who took their sweet time about it, and then the staff (including the monkey), who were champing at the bit to get home. The waiter from the coffee shop had changed out of his jacket. He looked positively run-of-the-mill without it. The last person to leave was the man from the ticket booth; it was he who was in charge of locking up. He took the task seriously—he checked the doors twice before tucking his keys in his pocket. I followed him as he set off towards the river, making, as it turned out, for the nearest public house.

Retrieving the receipt for my pencil, I crumpled it a little (to add an air of authenticity), then ran up and tapped him on the elbow.

“Yes?” he said, peering down at me, as his fingers closed round the handle of the pub’s glazed door.

“Sir,” I addressed him in my most earnest voice, “I believe that you might have dropped this.” I held out the receipt for inspection.

He looked at it, recognized the commercially-printed header, and dismissed my claim with a wave of his hand. Then he pulled the door open and stepped into the pub, shutting me out on the footpath.

Though I kept my face blank, on the inside I was beaming, for I now had his full set of keys.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 25th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or still too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on July 18, 2014 06:09

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, polari, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Five

“Where was you yesterday?” George hissed into my left ear, as he trudged beside me down the corridor in the direction of Mr. Crabbit’s office.

“Where was you yesterday?” George hissed into my left ear, as he trudged beside me down the corridor in the direction of Mr. Crabbit’s office.“Yes, where was you?” echoed his namesake in my right. “We was made to run errands!”

“That’s right. Errands. All of them!”

I thought about different ways to respond to this—including (but not limited to, as Mr. Bruff would have me add) the obvious, the fact that, as office boys, this was their job—but then it suddenly dawned on me. If I wanted to cause a reaction, why not tell them the truth?

“George, George, if you really want to know, yesterday Mr. Bruff paid me to sit in a coffee shop and eat cake.”

“You was eating cake while we was running us-selves ragged?”

“Uh-huh.”

“And Mr. Bruff was paying you?”

“Well, he will have paid me as soon as I claim back my expenses,” I said. And, with that, I pulled my receipts from my pocket and knocked briskly on Mr. Crabbit’s door.

A crotchety voice called out, “Enter!”

To rub salt into their wounds, I purposely left the door ajar as I strode into the petty cash clerk’s tiny sanctuary, so that George and George would be able to witness the transaction for themselves. As it turned out, this was a gross miscalculation on my part.

Mr. Crabbit inspected each of the three receipts I handed him as if he were a judge assessing the admissibility of evidence in a murder case.

“What’s this, boy?” he asked.

“It’s a receipt for a pencil, sir. I had to buy a pencil in order to make some notes.” The way I saw it, I had bought the pencil for my brother out of my own pocket; I was simply using the receipt in lieu of the one I had failed to get at the ticket booth.

“I can see it’s for a pencil, boy. No, look again. Look carefully. What’s this?”

“It’s crumpled?”

He smiled and lowered his spectacles on to the bridge of his nose. “Yes, it’s crumpled.”

“So?”

“Observe, boy.” Without turning to look himself, he raised a short, bony finger and pointed to the sign that hung behind him on the wall:

No illegible receipts

No indecipherable receipts

No torn receipts

No crumpled receipts

No defaced receipts

No stained or water-damaged receipts

No receipts with additions or alterations

No receipts that require further explanation

A burst of muffled sniggering wafted through the doorway. Mr. Crabbit rose from his desk like a whirlwind—not an easy task for a slight, balding man of his particular stature—and pulled the door open as if he were about to rip it off its hinges, unstoppable force of nature that he had become.

“George and George. Why am I not surprised? Well? What do you require?”

“N-nothing, sir.”

“N-no, sir, nothing.”

“Then be about your business, both of you, before I report your idleness to Mr. Bruff.”

Mr. Crabbit shut the door and calmly returned to his desk.

Having collected my money, but only for the cake and the candle, I made my way up the stairs to Mr. Bruff’s office. The Georges were perched on the bench outside. They scowled at me as I knocked and entered.

I was in two minds as to just how much of yesterday’s adventure I was prepared to share with Mr. Bruff. Without incriminating Miss Penelope directly—a thing that I wished to avoid until I’d had a chance to investigate her myself—it seemed prudent not to reveal too much. Too many facts were bound to lead to questions, and questions demanded answers—answers that I wasn’t yet ready to give. Mr. Bruff, bless him, was quite entranced by the dry and rather limited account of my movements, as I described how I had traced the flower girl in question, followed her to a nearby pub noted for hosting bare-knuckled fistfights, then trailed her as she made her way east as far as the Thames Tunnel, where, upon entering, she had managed to give me the slip. I summed up by saying that I was sure I could trace the girl again, and that I had devised a plan for making her talk.

“Excellent work, Gooseberry,” said Mr. Bruff. “I really don’t know how you manage it.”

It’s easy, I thought. I simply leave out all the important parts, such as the fact that the flower girl was actually a man, who was currently moping about in my lodgings, too scared to set foot outside my door. And he would happily whistle like a canary if he thought I might turf him out.

Aloud I said, “Sir, it occurs to me that the gang may attack again.”

It was almost certain they would, now that they thought Mrs. Blake’s aunt was in possession of the daguerreotype.

“You may be right. I’ll warn the Blakes to take extra precautions.”

“I think you should include Mrs. Merridew, too.”

Mr. Bruff grunted his assent. He took out a sheet of paper and began to scrawl a hasty note.

“George!” he called out at the top of his voice. I kept my eye on the door, curious to see which one of them would appear.

It was the younger of the two who answered the call. He glared at me mutinously as Mr. Bruff gave him his instructions. When it came time for him to leave, instead of going, he hovered like a lump in the doorway. He turned a bright beet-red when Mr. Bruff asked what the matter was.

“Sir, why can’t you send him?” he said, pointing his finger at me. “George and me, we ran all the errands yesterday. Why can’t he go this time?”

Mr. Bruff raised his eyebrows. “Gooseberry? No, it’s out of the question. I require Gooseberry for other duties.”

“Like bleedin’ eating cake,” George muttered.

“I beg your pardon?”

He scowled angrily at Mr. Bruff and then he scowled at me. “I didn’t say nothing,” he replied at last, before finally shutting the door.

For several seconds Mr. Bruff sat staring at the spot where George had been standing. “Would you believe that boy is only sixteen? The other one’s seventeen, yet they waddle about like a pair of middle-aged men. I only have myself to blame. I should never have allowed them to become so slothful or fat.”

Mr. Bruff rose, took a key from his desk drawer, and proceeded to open his office safe. He extracted the daguerreotype, dusted it down with his fingers, and placed it in his pocket.

“Come,” he said. “We have an appointment with a certain gentleman in Hanover Square. I am hopeful that he will be able to identify the people in this picture.”

Again he requested my presence in the cab. As he was in an amiable mood, it seemed like a perfect opportunity to bring up the matter of my expenses.

“Mr. Bruff, sir,” I began, “last night I was obliged to take a cab home from Wapping. As I didn’t have any money, I was forced to find an alternative method of payment.”

Mr. Bruff stared at me. “Octavius, please tell me that you didn’t resort to stealing?”

“I didn’t filch anyone’s wallet, sir.” Which was true as far as it went. Mr. Bruff looked touchingly relieved. “But if I am to investigate this case as you would have me do…” I left it up to my employer to finish the sentence.

“Then you will require sufficient funds to enable you move about the city at will. Yes, I can see that. I shall have a word with Mr. Crabbit when we return to the office. He will provide you with an allowance by the end of the day.”

The cab turned off Oxford Street into Hanover Square and pulled up outside an impressive-looking building, which, Mr. Bruff explained, was a rather exclusive gentleman’s club. He also warned me that there might be a problem about my accompanying him in. There was. The man at the desk was quite adamant that on no account were children to be admitted to the Oriental Club. We remained in that polite state of impasse until Mr. Murthwaite, the gent we had come to see, arrived and insisted that the three of us be shown to a private chamber, out of sight and out of sound of any member who might object to my obviously troublesome and distressing presence. The man at the desk regarded me sullenly, and called for one of his minions. I returned his look with a beaming smile as the underling led us away.

We were shown to a surprisingly nice room, the likes of which Mr. Bruff might call ‘well appointed’. It had a roaring fire down one end, and prints of Indian scenes on the walls. Upon entering, Mr. Murthwaite, a tall, lean man with skin the color of mahogany, turned to my employer and clasped his hand warmly.

“It’s been a long time,” he said.

“Too long, sir,” Mr. Bruff replied. “May I present Octavius Guy, one of my most trusted and valued employees, who, you might be interested to hear, was instrumental in unraveling the mystery of the Moonstone diamond?”

A pair of steady, attentive eyes studied me with interest. The gentleman whom they belonged to reached out and offered me his hand. “It’s nice to meet you, Octavius.”

“It’s very nice to meet you, sir.”

“Mr. Murthwaite is the celebrated Indian traveler, famed for his exploits in the East,” Mr. Bruff explained.

“If we have time, I do hope you will honor me by relating your contribution to the Moonstone affair, for I had some small part to play in it myself. However, I believe Mr. Bruff wishes to consult me on another matter first.”

“I do, sir.” My employer took the daguerreotype from his pocket. “I wonder if you can cast any light on this?”

Mr. Murthwaite opened the case and gazed at the photograph. For a minute he neither moved nor spoke.

“What is it you would like to know?” he asked presently.

“Can you identify either of these people?”

“Certainly. During my time in India I was privileged to meet them both. The man’s name is Login. Dr. John Login. Solid sort. Dependable. The boy seated next to him is Duleep Singh, the Maharajah of Lahore, leader of the deeply troubled Sikh Empire.”

“The boy’s a maharajah?” I burst out, unable to hold my tongue. Note to self: if you can keep your expression suitably blank when you’re pocketing things, surely you can learn to control your tongue?

Mr. Murthwaite smiled. “He most certainly is. He was five when he assumed the title. He would would be about your age now, Octavius. I imagine this photograph was taken two or three years ago.”

“This Dr. Login, is he some kind of adviser?” inquired Mr. Bruff.

“In one sense, yes. Though it may be fairer to say that he is boy’s warder. It’s a long story.”

“Sir, I would be grateful if you can tell me anything you can.”

Mr. Murthwaite nodded. “Then we should sit.”

He herded us towards the fireplace and we took our seats around the fire.

“Duleep’s father was the great Ranjit Singh, the Lion of the Punjab,” he began, “who conquered the rival Sikh nations and forged them into one great Sikh empire. During the course of his life he took several wives, who between them bore him a total of eight sons. Only two of these were ever recognized as his legitimate offspring, however: Kharak, the eldest, and Duleep, the youngest, who was born barely a year before Ranjit’s death in 1839.

“Naturally, it fell to Kharak to succeed him. But within three months Kharak found himself brought up on charges of sedition, the most damning of which alleged that he’d been colluding with the British. You can bet your last cheroot that these charges were pure trumpery, for they were based solely on the rumors spread by one man—Ranjit’s old adviser, the Wazir Dhian Dogra, a deceitful wretch who had designs on the throne himself. Nevertheless Kharak was deposed and imprisoned, and died within the year, the victim of slow and gradual poisoning.

“It was Kharak’s son, the nineteen-year-old Nau Nihal, who inherited the title on his father’s deposition—though he was not to hold it for long, as things turned out. He was struck by falling masonry when re-entering the Fort of Lahore, having just overseen his father’s cremation. While his companion was killed outright, Nau Nihal was merely wounded. Dhian had the unconscious ruler dragged inside, and then ordered the gates to be locked, so that none, not even his mother Chand Kaur, could enter the fort. By the time she was permitted to see him, a strange transformation had occurred. What was once a simple flesh wound had become a mortal injury. Somehow his skull was now cracked wide open, and Nau Nihal lay dead.”

Mr. Bruff threw me a nervous look. I think he was worried that the tone the story was beginning to take on was unsuitable for my young, delicate ears. Bless his naive, deluded soul!

“Chand Kaur now proclaimed herself regent,” Mr. Murthwaite continued, “ruling in the place of Nau Nihal’s as yet unborn son, for, as it happened, Nau Nihal’s young widow was with child. Chand’s brazenness so infuriated the wazir Dhian that he wrote at once to Sher Singh, son of Ranjit by his estranged first wife, urging him to muster his troops and march on Lahore. Sher Singh did as the wazir requested, and after the ensuing battle, Chand Kaur conceded defeat. She agreed to retire to her late son’s palace on one singularly ill-conceived condition: that she receive a pension of a million rupees. It was a fatal error of judgment on her part. When her daughter-in-law gave birth to a stillborn infant—signaling the end of Kharak’s bloodline and any further claim to power—Dhian replaced her servants with his own, and had them club her brutally to death.”

“I say,” Mr. Bruff interjected, “remember the boy is listening!”

“Do not trouble yourselves on my account, good sirs,” I tried to reassure them both. “There’s nothing I love more than a good story, and the bloodthirstier the better, as far as I’m concerned.”

Mr. Bruff nearly choked. Mr. Murthwaite, on the other hand, burst out laughing.

“Then I shall try to make the climax as gruesome as I can,” he promised. “Now, where was I? Ah, yes. Sher Singh. By all accounts the new leader was anxious to re-establish harmonious relations between all the feuding Sikh factions. He managed to broker approximately twenty months of relative peace, but then, one morning, when he was attending a friendly wrestling match on the outskirts of the city, he was lured outside by a pair of brothers who’d been supporters of the late Chand Kaur. Sher had always had a fascination with weapons, so when they offered to show him their latest rifle, he readily agreed to accompany them. As Sher took the barrel in his hand to examine it, the first brother pulled the trigger and shot the maharajah in the chest. The second brother then took his sword and hacked off the poor man’s head. That done, the pair rode away to Lahore, carrying the severed head with them. They tracked down the wazir and made him grovel at their feet, then placed the rifle at his temple and put a bullet through his brain. Which is how the five-year-old Duleep came to rule an empire, although, of course, it was his mother who acted as his regent.”

“Extraordinary!” I cried, clapping for all I was worth while Mr. Bruff sat fuming.

Mr. Murthwaite took out his cigarette case and extracted a cigarette, having offered Mr. Bruff one first. He lit it, drew the smoke into his lungs, then blew it out again towards the ceiling.

“In December of 1845,” he said, “Britain declared war on the Sikh nation, in what was to become known as the First Anglo-Sikh War. They—or should I say we?—won.” I sensed a touch of bitterness in his voice. “Although they kept Duleep as the nominal figurehead, they imprisoned his mother, and subsequently sent her into exile. After the Second Anglo-Sikh War four years later, Britain annexed the Punjab, deposed young Duleep, and placed him in the care of Dr. John Login. At first the two of them went to live in the fortress of Fatehgarh. I imagine they hoped that his followers would come to forget him. Out of sight and out of mind, and all that. In all likelihood, this photograph of yours dates from that period. 1849; 1850, at most. It can’t be any later.”

“Why not?” asked Mr. Bruff.

“Because although Fatehgarh was capable of holding a twelve-year-old boy captive with astonishing ease, it proved unequal to the task of containing his story. While Duleep remained on Indian soil, he would always inspire supporters. So last year they brought him here to England on the pretext of visiting the Great Exhibition. I know this because I saw him there.”

“So the maharajah’s here? Do you know by any chance where he is staying?”

“I may be on a nodding acquaintance with royalty, Mr. Bruff, but I can hardly claim a place in his social circle. Dr. Login, on the other hand, is quite another matter. I happen to know he’s a member of this club. The secretary is bound to have his address on record. If I remember rightly, the chap runs some kind of hospital, somewhere out Richmond way. If anybody can tell you where the maharajah is staying, it is he.”

Mr. Murthwaite smiled and stubbed out his cigarette. He closed the clasp of the daguerreotype and handed it back to my employer.

“Now, Octavius,” he said, as he turned to me, “it’s almost midday. Let us see how that damnable lackey, who refused you entry, likes it when I order us all a good, slap-up dinner.”

Gooseberry continues next Friday, August 8th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on August 01, 2014 06:05

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Six

Lunch started off with a carrot soup that tasted very strange indeed. I’m not sure I liked it. Then came the main event, a dish of rice, which Mr. Murthwaite called ‘kedgeree’. He said that, although it was actually a breakfast food, he enjoyed it so much that he happily ate it at any time of day. It took my mouth a little while to get used to all the competing flavors, but, once it did, I found it was really quite more-ish. I didn’t imagine it was something I could taunt George and George with, however. I had a shrewd suspicion they’d turn their noses up at rice.

Lunch started off with a carrot soup that tasted very strange indeed. I’m not sure I liked it. Then came the main event, a dish of rice, which Mr. Murthwaite called ‘kedgeree’. He said that, although it was actually a breakfast food, he enjoyed it so much that he happily ate it at any time of day. It took my mouth a little while to get used to all the competing flavors, but, once it did, I found it was really quite more-ish. I didn’t imagine it was something I could taunt George and George with, however. I had a shrewd suspicion they’d turn their noses up at rice.By the time we got back to the office there was a reply awaiting us from Mr. Blake. He expressed his thanks for Mr. Bruff’s concern, and assured him that he would put measures in place forthwith to increase security at both his own and Mrs. Merridew’s residences.

Mr. Bruff was true to his word, and arranged for Mr. Crabbit to provide me with a sum of money—a per diem, he called it—that I could use at my discretion, to be topped up each day as required. When I asked if I would need to provide receipts, Mr. Bruff assured me that I would not, but I wasn’t convinced that Mr. Crabbit would see things the same way. So when he called me to his office to give me my seven shillings and sixpence—an extremely generous amount on Mr. Bruff’s part—I made sure I put the question to him as well. I half expected to see his finger point to the sign on the wall.

No illegible receipts

No indecipherable receipts

Etc., etc.

Instead he shuddered a little, gritted his jaw, and said, “No receipts will be necessary.” I’m not sure there wasn’t a tear in his eye. “But,” he added quickly, in a tone that sounded like begging, “any receipts that you do provide will be gratefully received.” I almost felt sorry for him.

With the coins rattling happily around in my pocket, I set off homeward, stopping only to purchase three pork pies, a whole black pudding, and three bottles of ginger beer on the way. When I got to my lodgings, I was surprised to find the door locked. First I tried knocking. No response. Then I tried shouting.

“Bertha, it’s Octopus! Open up!”

When that didn’t work, I tried looking under the doormat for the key—for I’d given one to Bertha to lock up with, in the unlikely event that he needed to go out. There it was, damn the man! I still had a great many things that I needed to know, and he was the only person in a position to enlighten me. I picked it up off the floor and let myself in.

The room was exceedingly warm. Judging by the heat that was radiating from the stove, Bertha must have lit it before he left. When I looked, I saw a puzzling amount of firewood stacked neatly in the crate in the corner. There was twice, maybe three times as much as there had been that morning. I placed the victuals I’d bought for our supper on the table and went and stoked the fire, opening and closing the metal door with the handy makeshift tool we always use. I slipped off my jacket and sat down on a chair. I might have fallen asleep but for Julius’s arrival home.

“Octavius!” he shouted, as he ran to hug me. All at once he noticed the feast on the table. “Black pudding! Ginger beer! And are those eel pies?”

“No, pork.”

“Well,” he said philosophically, “you know I like pork pies, too, don’t you?”

“I know, Julius, I know.”

Our reunion was interrupted by a sharp knock at the door. When I answered it, there stood Bertha, looking extremely sheepish.

“I hoped to get back before you did,” he said, bustling past me into the room as Julius’s face fell, “but I got stuck on the wrong side of the road, and had to wait till all those damn cows had gone by. Look, I got us some potatoes,” he added. “We’ll cook ’em and ’ave ’em for supper.”

“Bertha, I already got us some supper.”

Ignoring the spread on the table, Bertha knelt by the stove, grasped the poker, and began to rake through the ashes in an unnecessarily elaborate fashion. He inserted the trivet, and, taking care not to burn himself, placed three large potatoes on top.

“I won’t have you thinking that I don’t contribute nothing,” he mumbled, as he manipulated the stove door’s catch back into place.

“What word will we do tonight?” piped up Julius, who’d been watching all this from his seat.

“I don’t know…what word do you think will be useful?” I asked, grateful for the sudden diversion.

“How about ‘welcome’? As in, ‘I know someone here who isn’t—’”

“Julius!” I barely managed to circumvent him in time. “Can we talk about the word later, please? After we have supper?”

“Potatoes should take an hour,” growled Bertha, as he sat on the floor with his back to the wall, for Julius had piled the two remaining chairs with stacks of scrap paper.

It was one of the most uncomfortable hours I have ever spent. By the end of it, I understood one thing: scared or not, this was not a flip-a-coin situation; Bertha was not staying here.

We ate in silence, with Julius nudging his potato further and further away from him till it was perched on the edge of his plate. Bertha took a bite out of his and suddenly burst into tears.

“How can I go back?” he wailed, the soft potato chunk still swilling round his mouth. “The Client’s bound to peach on me to Johnny ’bout how I done something wrong—though for the life of me I don’t know what it was. And Johnny being Johnny, he won’t hesitate to punish me. Like as not he’ll throttle me to death. Oh, wot am I to do? Wot am I to do?”

Julius had been in the throes of biting into his pork pie when Bertha burst out crying. He now sat frozen in that position, staring at the fully-grown man before him who was sobbing into his shawl.

“Johnny always had a temper—you know wot he was like—but when he took over from Ned, it just got worse and worse. He changed, Octopus. He changed, and not for the better. Set up his headquarters at the Lamb and Flag—started running bare-knuckle fistfights out of there. Now they call it the Bucket of Blood, and with good reason, too. Those fights are to the death; it’s no holds barred with Johnny.” Bertha clapped his hand over his mouth to try and silence the great, heaving sobs that were rising up out of his chest.

“Bertha, what happened to Ned?”

“Oh, Octopus, the Yard nabbed Ned a good five years back. Hauled him up before the magistrate on some trumped-up charge of burglary. Claimed some old geezer got himself hurt while the job was going down, so everyone thought he’d swing for it. He didn’t, but they transported ’im off to Tasmania. Ned, though, he never done it. You know wot he felt about violence. There are some as say Johnny was behind it all—not to his face, o’ course. Say it to his eek and he’d cut you up in bleedin’ ribbons.”

Bertha was still sobbing sporadically throughout this and Julius was still gawking at him. I wondered how much of this my brother understood. Very little, I hoped, though even very little was more than I was comfortable with.

“Bertha, what can you tell me about the Client?”

“’E’s just some bloke wot Johnny knows. A regular at the fights, I think. Came to Johnny not long before Christmas, offering to pay him a king’s ransom to get his bleedin’ duggairiotype back.”

“What was he doing in the tunnel?”

“The tunnel’s where he works.”

“Works?” My thoughts immediately turned towards the waiter.