Michael Gallagher's Blog - Posts Tagged "michael-gallagher"

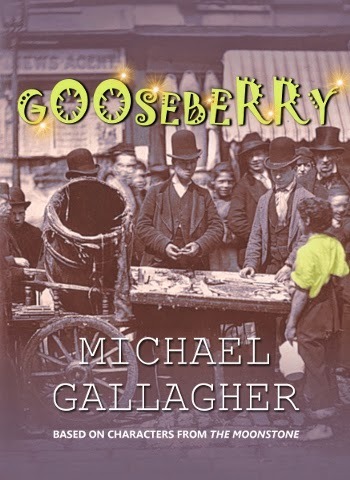

Which covers do you prefer?

My first novel, The Bridge of Dead Things, turns one year old on April 6th. It's been a very busy year. Through my books, my website and my blog, I've published a staggering 180,000 words online. I've had some fantastic reviews here at Goodreads, and also at Amazon, Smashwords, and LibraryThing—some from as far afield as Sardinia and Nepal—many of which left me quite choked up and more than a little misty eyed. I've also had a few stinkers too, but thankfully I can (quite literally) count those on one hand.

My first novel, The Bridge of Dead Things, turns one year old on April 6th. It's been a very busy year. Through my books, my website and my blog, I've published a staggering 180,000 words online. I've had some fantastic reviews here at Goodreads, and also at Amazon, Smashwords, and LibraryThing—some from as far afield as Sardinia and Nepal—many of which left me quite choked up and more than a little misty eyed. I've also had a few stinkers too, but thankfully I can (quite literally) count those on one hand.To mark the occasion I've rebranded the series. There are new book descriptions courtesy of Monica F—catya77—a member of the LibraryThing Early Reviewers Programme where she bid for and won an advance copy of The Scarab Heart. Monica, who is also a Goodreads librarian, always included a really catchy little summary in her reviews—which I totally fell in love with—and luckily for me she said "yes" when I begged her to let me use them!

I also have a new set of book covers which I adore. You'll see the entire range (even for titles yet to be written) below. Many of my readers expressed concerns about the original covers, and I think these new ones match the books perfectly. But what do you think? Do you you agree, or do you prefer the "marmite" (some love it/some hate it) originals? You can leave me a message or, better still, why not join in the debate that I set up at the bottom of The Bridge of Dead Things book page? I would love to hear your thoughts.

If you already purchased the books, simply download them again (either from your Kindle's library or from Smashwords, if you bought them there) and choose the latest version to get the new covers. As far as I'm aware, there's no extra charge for this. You bought the books, not the cover!

If you've yet to buy them, why not check out the My Shout page on my website, michaelgallagherwrites.com, which is also celebrating its first birthday, where throughout April you will find a truly extraordinary and never-to-be-repeated offer.

Michael Gallagher

The Bridge of Dead Things:

The Scarab Heart:

The Cat Who Fishes:

The Prodigal Daughter:

The Empress of Time:

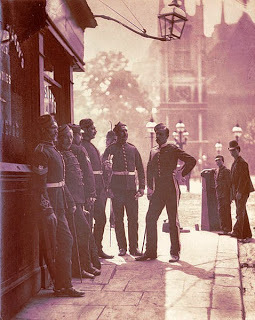

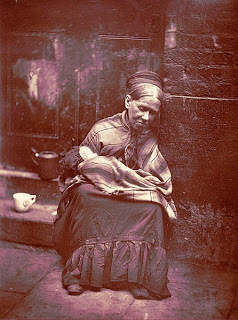

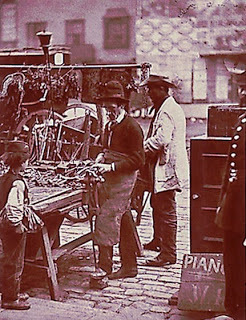

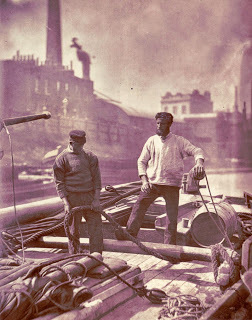

Photographs by Captain Console, Neithsabes, Marc Ryckaert, Daniel Csörföly, Eugène Atget, El Fabricio de la Mancha, John Thomson, Harris & Ewing, Inc, and whatsthatpicture

Cover designs by Negative Negative

Published on April 01, 2014 03:41

•

Tags:

bridge-of-dead-things, michael-gallagher, scarab-heart

Watch me crash and burn: writing a follow-up to "The Moonstone"

Crash and burn? Probably. Have a great time doing it? I already am.

Crash and burn? Probably. Have a great time doing it? I already am.I recently re-read Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone for a Crime & Thrillers reading group I attend. I was particularly struck by one of the minor characters who pops up towards the end, the lawyer Mr Bruff’s office boy, Octavius Guy—better known as Gooseberry.

As I read I began to realize that Gooseberry would make a fantastic protagonist for a novel and it occurred to me that here was the perfect project for my summer break—writing and publishing a serialized novel in weekly installments, just as Collins did a hundred and fifty years ago.

I immediately started researching the period, hoping to find some hidden little nugget of history that might begin to suggest a plot—but I discovered zilch! 1852 was a very uneventful year. I also started writing to try to find Gooseberry’s narrative voice—again, nada! So at this point, I’ve no plot and no narrative voice and only two weeks in which to find them.

On the bright side, I have got a title (Gooseberry), a prototype cover, a charming protagonist who now has a fleshed-out back story, and I’ve inherited a number of The Moonstone’s other wonderful characters to play with. Oh, and I’m still hugely excited by the prospect of trying to write a serialization on the hoof!

One thing I’m very clear about: Gooseberry will never be a sequel to The Moonstone. The novel I envisage writing will be a detective story with an historical setting—and quite a comedic one at that. Think Alexander McCall Smith’s No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, Alan Bradley’s Flavia de Luce novels, and Colin Cotterell’s Siri Paiboun mysteries.

I’ll be publishing it in weekly installments here on my Goodreads blog, so I do hope you’ll join me. Please wish me luck. I’ve a feeling I’ll need it.

Michael

Michael Gallagher’s Gooseberry (not exactly a sequel to Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone but more of a spin-off) is serialized here at Goodread in weekly installments every Friday from July 4th 2014. You can also follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

Published on June 20, 2014 06:11

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialzation, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry – the blurb

1852. With the business of the Moonstone diamond finally laid to rest, Mr. Franklin Blake and his wife Rachel are now happily married, living in London, and blessed with a healthy baby daughter named Julia. Mr. Blake has taken his late father’s seat in Parliament, and his party’s fortunes are on the rise—in fact they are about to overthrow the coalition government of the day.

1852. With the business of the Moonstone diamond finally laid to rest, Mr. Franklin Blake and his wife Rachel are now happily married, living in London, and blessed with a healthy baby daughter named Julia. Mr. Blake has taken his late father’s seat in Parliament, and his party’s fortunes are on the rise—in fact they are about to overthrow the coalition government of the day.But when Rachel and her aunt are attacked in the street by a group of feral children, they soon discover that something quite inexplicable has occurred.

Enter the Blakes’ lawyer’s office boy, Octavius Guy—better known as Gooseberry—who once helped the family bring the mystery of the Moonstone to a close. Join in the fun as young Gooseberry descends into London’s demi-monde and underworld to investigate this new affair, following up the clues wherever they may lead him.

Michael Gallagher’s Gooseberry (not exactly a sequel to Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone but more of a spin-off) is serialized here at Goodread in weekly installments every Friday from July 4th 2014.

You can also follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry. . Will Gooseberry be perfect or pear-shaped? You decide!

Published on June 27, 2014 06:08

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialzation, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter One

London. Monday, January 19th, 1852

London. Monday, January 19th, 1852George and George, the other two office boys at Mr. Bruff’s law firm, sat snoring beside me on the bench, the victims of over-indulging on a plate of chops for their lunch. I gave the closer George a hefty nudge with my hip to try to claim back my fair share of the space. He came to for just a moment, blinked his eyes wearily, and then adjusted his hulking frame so that I had even less room than before.

Mr. Bruff’s office door swung open. Mr. Bruff came out and stood there contemplating the three of us. The look on his face suggested that he didn’t much care for what he saw.

“Gooseberry, with me,” he said, and, closing the door behind him, made directly for the stairs. I leaped up and padded along after him.

“The local chophouse again?” he inquired, as we exited the building together into a cold and foggy Gray’s Inn Square.

I nodded.

“Gooseberry, kindly inform George and George that from now on their favorite chophouse is officially off-limits.”

I don’t object to Mr. Bruff calling me Gooseberry, though I would have you know that it is not my real name. It’s a name that’s been given to me by one of Mr. Bruff’s clerks on account of my eyes. They bulge. At least, that’s what this clerk delights in telling me almost every single day. Naturally I can’t help them bulging any more than I can help being blessed with brains, and blessed with brains I am—to a far greater degree than either of the Georges, or that fool of a clerk, come to that.

I hasten to add, lest I later appear anything but entirely truthful on the subject, that having brains is not the only talent of which I am possessed, nor is Gooseberry my only nickname, which I’m sure will become clear in good time.

Mr. Bruff spotted a passing cab and put his hand out to hail it. As it pulled to a halt beside us, he directed the driver to an address in Montagu Square. I recognized the address as that of his close friend and client, Mr. Franklin Blake—Member of Parliament—a man to whom I have had the privilege of being useful in the past. I gripped the handrail to haul myself up to my usual seat beside the driver, but Mr. Bruff clasped me by the wrist and informed me that today he required my presence in the carriage. “There is a matter,” he said, “that I wish to discuss.”

Despite the ominous words, Mr. Bruff remained silent as the cab pulled away from the curb. It wasn’t until after we’d traded High Holborn for that long stretch of road that is Oxford Street that he finally opened his mouth to speak.

“Octavius,” he said, using my proper name for a change—a name which translates from Latin as ‘the eighth child’; not that I am the eighth, you understand, I’m actually the first—“do you recall how we met?”

“I do, sir, I do,” I replied, “although it’s a good six years ago now.”

“It was a day not unlike today,” he reminisced, “thoroughly miserable and wet. I was in Regent Street attending to a small matter of business when I observed a young lad loitering on a corner—a barefoot urchin trembling in the rain, his toes turning blue from the cold.”

Mr. Bruff does like to over-sentimentalize our meeting. I imagine it helps him justify the choice he made that day. But don’t be fooled by his sweeping sentimentality. This image he was painting hadn’t prevented him from grabbing me by the scruff of the neck, just as I was about to remove my hand from a gentleman’s pocket—with the gentleman’s wallet attached. When I tactfully pointed this out to him in the cab, he immediately began to bluster:

“I had every right to march you straight in front of a magistrate, Gooseberry! Instead I chose to take pity on a young, shivering ragamuffin and offer him a position as my office boy! Can’t you be grateful for that?”

I was grateful to him for getting me out of the Life, and I told him so—before he decided to clip me round the ear. But there was more to this story than he was aware, for I’d never got around to sharing it with him. He had always assumed I was barefoot because I was poor, but that just wasn’t so. I was barefoot because one of my trusty colleagues had stolen the boots off my feet while I slept. They say there’s no honor amongst thieves, and they’re right. It was only because of this temporary state of bootlessness that the old man had been able to nab me that day, for I guarantee you, at the age of eight—with my boots on—there was no swifter, slipperier pickpocket in all of London than yours truly, Octavius Guy.

It’s what Mr. Bruff might term ‘an irony’ (a word which he assures me has everything to do with the jesting of Fate and nothing to do with scrap metal), for my lack of boots was not just my downfall. When the lawyer took pity on my poor freezing feet, it also became my salvation.

“Gooseberry, over the years you have proved yourself trustworthy, resourceful and loyal,” Mr. Bruff went on, his wistful smile returning, “and in return I have kept your former profession a secret from employees and clients alike. But today, Octavius, for the greater good, it may become necessary to divulge its nature.”

“To Mr. Blake?”

Mr. Bruff grunted.

“Sir, have I done something wrong?”

“No, not at all. It’s quite the opposite, in fact. Mr. Blake’s summons was uncharacteristically vague, but the few details it gave made me think that your specialist knowledge might come in handy.”

“How so?” I asked, but Mr. Bruff would say no more, preferring not to speculate until he had all the facts at his disposal. I gazed out the window. We were passing by Hyde Park and the rain was billowing about us in sheets. I tried peering into the distance to see if anything remained of the Crystal Palace, where the Great Exhibition had been held the previous year. I couldn’t make out so much as a dickey-bird. Perhaps they’d already dismantled it. It set me thinking: what had they done with all those millions of panes of glass?

It was Samuel, the footman, who answered the door to us at Montagu Square. I’d met Samuel before on several occasions, just as I’d met most of Mr. Blake’s household. He took charge of Mr. Bruff’s cane and hat (though he pointedly ignored mine, obliging me to keep hold of it myself), and ushered us into the library where the family had gathered.

What a mournful sight! In the middle of the room sat a small, elderly lady, unknown to me, who was working on a piece of embroidery—or rather not working on it, for each time she inserted the needle, her fingers would shake and she’d burst into tears. Young Mrs. Blake was on her knees at her side, her arms around her, trying in vain to comfort her as best she could.

Mrs. Blake’s maid, Miss Penelope, stood in the background, miserably wringing her hands in distress. It shocked me to see the complete disarray that both her locks and her clothing were in, for she was a young woman who normally took such pride in her appearance. Wisps of red hair hung loose about her face, as if she’d just been in a cat fight, and her blouse, which had been wrenched loose from her skirts, was ripped in at least three separate places.

Miss Penelope’s father, the ancient Mr. Betteredge—the family’s faithful steward—lay slumped in a chair by the flickering fire with a tattered old book clutched to his chest. I couldn’t be certain whether he was awake or asleep, for, ranked as I was as being little better than a tradesman, I was obliged to keep my distance when Mr. Bruff stepped forward to greet the family.

Mr. Blake, who’d been pacing listlessly about the room, grasped my employer’s hand and shook it. But it was his wife—and not he—who quickly took charge of the interview.

“Mr. Bruff, thank you for coming on such short notice,” she said, as she rose to her feet. “You will remember my aunt, Mrs. Merridew?”

“A pleasure as always, madam.” My employer smiled and gave a stately little bow.

The woman acknowledged it with a nod of her head. “I had hoped to quieten my mind by occupying myself with something trivial and mundane,” she said, staring down at the embroidery in her hand, “but it doesn’t seem to be working.”

With this she broke into a fit of sobs.

“My aunt has had a rather nasty shock,” Mrs. Blake explained. “Actually, apart from my husband—who did not accompany us this morning—we all have.” She glanced meaningfully over her shoulder at Miss Penelope, who blinked, bit her lip, and wrung her hands again.

“My dear, as your trusted friend and your lawyer, I suggest that you start at the beginning and tell me everything that’s happened.”

“Then perhaps we should sit down.”

Mr. Blake drew up chairs for them both and then resumed his pacing.

“Mr. Bruff, do you consider me an imaginative woman?”

My employer gave the question some careful thought before he hazarded a reply. “Miss Rachel, I have known you your entire life. If you ask whether I believe you possess an active imagination, then I would say, yes, you display a healthy and inquisitive one; a match for any man’s. But if you ask whether I think you imagine things, then, no. Lawyer that I am, I would still take your word over others, were all the evidence on God’s good earth to speak against you.”

Mrs. Blake seemed pleased with this answer and rewarded him with a faint smile.

“Then I shall begin where I believe this mystery begins,” she said, “even though I have no proof that it does. Last week we happened to receive an unusual number of nuisance callers. When Samuel, our footman, answered the door he would find an old beggar woman on the doorstep, with sprigs of winter heather for sale—or one of those preposterous suppliers of religious tracts—or a man who grinds knives for a living. It became ridiculous, quite ridiculous, and really rather tiresome. Occasionally he would even respond to the bell to find nobody there at all!”

“Oh, my!” exclaimed Mrs. Merridew. “How very odd! We had the same trouble at Portland Place…just before my footman gave his notice. I wondered if the bothersome callers had anything to do with his leaving, for I have no doubt they played havoc as much on his nerves as they did mine, so I asked him straight out, but he said not; rather that he was obliged to attend to his sick brother.”

“You had nuisance callers too? But, Aunt Merridew, why didn’t you mention this earlier?”

“I didn’t think it important, dear.”

“Surely it cannot be a coincidence! Aunt, has anything else out of the ordinary happened to you recently? For instance, have any of your windows been broken?”

“Oh, my…not that I can think of. Why do you ask?”

“Because last Friday morning Penelope discovered a broken pane of glass in the servants’ quarters.”

Mr. Bruff sat forward with a look of concern. “You experienced a burglary?”

Mrs. Blake shook her head. “Apparently not, Mr. Bruff, for when I had Betteredge check the inventory nothing appeared to be missing.”

“An accident, then?”

“Perhaps.” She sounded doubtful. “Though if so, I’m surprised that no one has come forward to own up to it. It was never in my mother’s nature to dock the servants’ wages for breakages, nor is it in mine.”

“How very curious.”

“Curious indeed. Which brings us to the events of today. I had plans to attend an early luncheon with my aunt at her house in Portland Place, and I decided to take Julia, my baby daughter, along with me. I asked Penelope to accompany us, to look after her on the way there. Then Betteredge insisted on coming, with umbrellas for us all in case it rained.”

On hearing his name, the old servant sat bolt upright in his chair.

“And rain it might have, Miss Rachel,” he spluttered, “and rain it finally did. But, in truth, that is not the reason I requested to come.”

“No?”

“No!” With trembling hands he held out the book he’d been clutching. His forehead was fevered with sweat. “Just this morning I opened my copy of Robinson Crusoe—the one your dear late mother presented me with on the occasion of what was to be her final birthday—and what should I find there?”

He riffled through its dog-eared pages, located the passage he was looking for, and then solemnly began to read aloud: “‘It was the howling and yelling of those hellish creatures; and, on a sudden, we perceived two or three troops of wolves on our left, one behind us, and one on our front, so that we seemed to be surrounded with them!’

“You see? You see?” he cried. “As I live by bread, miss, I knew in my heart that these self-same perils I had been directed to in this book were fated to befall you today! It was my sworn duty to come with you; no more, no less. My duty!”

An uncomfortable silence descended on the company, during which even Mr. Blake stopped his pacing.

“Robinson Crusoe? What has Robinson Crusoe to do with this?” my employer demanded.

A shorter silence ensued, broken this time by Mr. Blake. “The good Betteredge firmly places his trust in Dafoe to steer him safely through life,” he explained.

“I do, sir, I do!” Mr. Betteredge came back, and with such passion in his voice that I wondered whether he had been drinking. “And you would be wise to, too, Mr. Bruff, lawyer though you may be!”

Lawyer that he is, my employer is not easily lost for words, but in this case he was rendered speechless. He finally responded with a shake of his head and turned his attention back to Mrs. Blake.

“Mrs. Blake, will you please continue?”

She nodded and took a deep breath. “It was a perfectly pleasant meal, Mr. Bruff, but then I noticed that the weather was taking a turn for the worse. I rose to leave. My aunt had pledged to come with us, as she wished to consult my husband over the hiring of a replacement footman. I suggested that she, Julia, and I take a cab home, but Aunt Merridew refused to hear of it, saying she would prefer to walk while the rain held off. We strolled back along Wigmore Street, and were just passing Portman Square when my aunt spied a woman selling flowers at the side of the road.

“‘Let me stop and buy a nosegay,’ she begged, and opened up her handbag to retrieve her purse. Suddenly a shriek rent the air, and then another and another, as we found ourselves surrounded by a pack of howling children, lunging and pecking at us from every side.

“I don’t know what would have become of us were it not for Penelope’s quick thinking. She pushed me and Aunt Merridew back against the railings, thrust the baby into my arms, snatched one of her father’s umbrellas and began to beat those monsters off, even as she shielded us with her body. It was so frightening! Their hands went darting everywhere—everywhere, all over us—though it was Penelope who bore the brunt of their attack. Their wailing, animal screeches finally brought people running, but the children saw them coming and swiftly scattered. By the time our rescuers got there not one of them remained.

“We were all understandably shaken, though no one was actually hurt except Penelope here. The men who had come to our aid kindly saw us home. I had Cook clean and bathe Penelope’s wounds, and asked Betteredge to make us all a restorative drink.”

Everyone looked towards the fireplace. Exhausted by his earlier outburst, the steward had fallen fast asleep.

“It was only while we were recovering,” Mrs. Blake continued, “that I realized the attack might have been purposely staged, perhaps to try to rob us, so we all checked our capes and belongings to see if anything had been taken.”

“And?”

“Well, this is the most perplexing part of all, Mr. Bruff. Nothing had been taken.”

The lawyer’s eyes narrowed. “But Mr. Blake’s summons…I was led to believe—”

“I repeat, nothing had been taken. But something had most definitely been left.”

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 11th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Do let me know! I’d love your feedback. Please use the comment box below.

Published on July 04, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Two

“Left?”

“Left?”“Inserted into Aunt Merridew’s bag. Here, see for yourself.”

Mrs. Blake rose and walked over to the table. She retrieved a small palm-sized leather case, not unlike a notebook, and carried it back to my employer.

“Open it.”

Mr. Bruff turned the case over in his hands, found the tiny clasp at the side, and unlatched it. All I could see was the occasional glint from where I was standing, but even so I was ninety-nine percent certain that what he was holding was a daguerreotype—a photograph on a sheet of silvered copper, mounted behind glass in a plush-lined case. There was a time not so long ago when I would have hopped up on a chair to get a better look. I should like to be able to tell you that I have since learned the value of patience, but it wouldn’t be true. What I have learned is that the upper classes don’t appreciate your boots on their furniture, no matter how pressing your needs may be.

“So,” my employer summed up, having studied the photograph at some length, “both you and your aunt were subjected to nuisance callers; a pane of glass was found broken in the servants’ quarters; and then today a gang of hooligans attacked you in broad daylight—not to rob you of anything, but to place this about your aunt’s person?”

“It sounds incredible, Mr. Bruff, I grant you, but how else can that daguerreotype have found its way into my aunt’s handbag?”

“Mrs. Merridew, do you recognize either of the people in this photograph?”

“No, Mr. Bruff, they’re perfect strangers.”

“Mrs. Blake?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t.”

“Mr. Blake?”

“I’ve never seen either of them in my life. But observe, sir—the boy. The tone of his skin…his manner of dress. Though the man’s a Caucasian—and most probably English, judging by the cut of his suit—the boy is an Indian, is he not?”

Mr. Bruff nodded. “And an extremely wealthy one, by the look of it.” He peered at the daguerreotype again. “It’s a very formal portrait,” he remarked, “carefully composed and beautifully rendered. It’s not the work of an amateur. And yet, notice the boy’s scarred right eye; there’s been no attempt to disguise the lad’s disfigurement.”

“You don’t suppose that this could have anything to do with that accursed Moonstone diamond, do you? I had hoped I’d put that business behind me for good.”

“Because the lad’s Indian? No, Mr. Blake, your investigations were faultless. I’m sure the boy’s race is purely a coincidence.”

“Then perhaps someone’s trying to discredit me. The political party I serve may be in opposition at the moment, but, trust me, sir, things are about to change. This unholy coalition—which would take its grain from other countries instead of from our own worthy farmers—they’re on their way out, and they know it! I wouldn’t put it past them to pull some dastardly stunt to embarrass us first.”

“If they were trying to embarrass you, Franklin, why give the photograph to my aunt?” Mrs. Blake inquired of her husband. “Why not to you?”

“A very good question,” said Mr. Bruff. “But what I’d like to know is why a street gang would go to these extraordinary lengths to do such a thing? That is the crux of this matter. What we need is someone versed in their ways who might help us unravel this puzzle. Gooseberry, I think the time has come for you to tell us what you can.”

I stepped forward, expecting to be quizzed about my credentials. Instead I found myself being fussed over handsomely by Mr. Blake.

“Upon my word! Gooseberry!” he cried, shaking my hand and slapping me on the back. “I didn’t see you there!”

Mr. Bruff quickly intervened and directed me to business. “What is your opinion,” he asked, “of all that you’ve heard here today?”

“First, can I please see the daguerreotype?”

“‘May I see the daguerreotype’,” Mr. Bruff corrected me, as he handed over the picture.

If anything it was even grander than I had imagined it: a portrait of a man and a boy seated side by side in chairs that could almost pass for thrones, in what can only be described as an opulently—and quite exotically—furnished room.

“Gooseberry, your contribution, please.”

I passed the picture back and turned to address Mrs. Blake. “Gangs such as you describe, miss, work in two particular ways, both of which depend on creating as much chaos and confusion as possible.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Well, to dazzle people’s senses, miss. It makes them slow to react.”

“I see. Go on.”

“In the first, the gang runs in, causes a commotion, grabs what it is they’re after, then scatters as soon as they can. It requires a little planning, but hardly any skill, which is why the second way is infinitely more satisfying—”

“Satisfying?”

As I considered what my response should be to this, I placed my hat, which their footman Samuel had obliged me to keep hold of, down on the nearest chair, earning myself a look of reproach from Miss Penelope, Mrs. Blake’s maid.

“Well, intellectually satisfying, if you like, miss. While the gang is wreaking chaos and everyone’s attention is diverted, somebody else—someone on the spot who seems quite unconnected to any of the troublemakers—he stealthily slips the desired items inside his jacket—an overly-large jacket like the one I’m wearing now.” Or down his trousers. Or under his hat. “Once the gang has scarpered, that person calmly walks away, taking his booty with him.” While lifting wallet after wallet as he saunters through the crowd. Ah, my glory days, indeed. “Later the gang meets up at some predetermined location to share out their spoils—in accordance with each person’s rank, of course, and the amount of risk each person took.” Well, the spoils that they know about, that is.

Mrs. Blake looked at me thoughtfully and asked, “Gooseberry, how do you know all of this?”

The time had come to own up to my past. I’d been thinking about how best to present it, and it seemed to me that what was called for here was a judicious mixture of remorse, honesty, and diffidence.

“Though it shames me to say it,” remorse, “there was no swifter, slipperier pickpocket in all of London,” honesty, “than…well, me, miss—your humble servant—Octavius Guy.” Diffidence dispensed in a generous measure.

Mrs. Blake burst out laughing.

“Please, Mrs. Blake, it’s true.”

“Gooseberry, you really mustn’t joke.”

“I’m not joking, miss.”

“I don’t believe it for a moment!”

Mr. Bruff gave a cautious lawyer’s cough that managed to get everyone’s attention. “He’s telling the truth,” he said quietly, and shot Mrs. Blake a meaningful look.

“But this is Gooseberry we’re talking about! Our Gooseberry! He’s no thief!”

“If he’s telling us the truth, then I think he should be made to prove it,” said Mr. Blake, a mischievous grin breaking out on his face that even his thick, black beard couldn’t hide. “I propose a challenge. Gooseberry, come and try to pick my pocket!”

“Please, sir—I don’t want to pick your pocket.”

“But I insist,” he said, stepping closer and closer till there was barely a foot between us. With everyone watching (save for the good Mr. Bruff, whose features plainly registered his disapproval), Mr. Blake leaned forward so that our noses were practically touching. On reflex, I found myself stumbling backwards, a move that Mr. Blake took as a sign of defeat.

“So much for the swiftest, slipperiest pickpocket in all of London,” he laughed, and, like a performer taking his curtain call, turned and bowed deeply to his wife.

“Franklin, look,” she advised him, pointing her finger at me.

Mr. Blake looked. His mouth dropped open. He stared, blinking in amazement at the silver cigarette case in my hand.

He patted the vicinity of his jacket’s left inside-breast pocket, feeling for something that was no longer there. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Mrs. Blake’s aunt place her embroidery in her handbag and hug the handbag to her chest. My heart suddenly crumpled; I should have realized how people might not take too kindly to discovering a thief in their midst.

Mr. Blake regarded me solemnly for several long seconds. “How did you manage it?” he asked at last. “I didn’t feel a thing. Not a thing.”

“It’s just a skill I have,” I replied, preparing to duck his blows as I handed him back his case.

“During my travels in the East, five men attempted to pick my pocket—and five men ended up regretting it. But you! That wasn’t skill, young man; it was art! By all that’s wondrous, you’re going to have to teach me how you did that!”

“Teach you to steal things? No, Mr. Blake! It wouldn’t be right.”

Mrs. Blake arched her eyebrow at the both of us and said, “I’m glad to see that one of you is old enough and wise enough to appreciate right from wrong. So, tell me, Gooseberry, expert pickpocket and moral compass that your are, in your opinion, what do you think happened to us today?”

“It’s very hard to say, miss. I can’t begin to fathom why a gang would want to plant something on you, especially if it’s something that holds no apparent meaning for any of you. However, from what you’ve told me, I’m fairly sure that the method they employed was the second one I outlined. Your attackers were simply the distraction. Somebody else—someone on the spot, seemingly unconnected—was responsible for slipping that photograph into your aunt’s handbag.”

“But who?” she asked. “The only people present were my aunt, myself, Penelope and her father, and my baby daughter Julia. You surely don’t suggest that one of us did it?”

“I beg your pardon, miss, but you’re mistaken.”

“Gooseberry, I know who was there. There was nobody else, believe me.”

“But there was, miss. There was the flower girl; the one selling flowers by the side of the road. Did anyone see where she went to?”

Mrs. Blake stared. “She was with us, I think. I really can’t remember. Aunt Merridew, do you recall?”

“I was too terrified to notice, dear. I expect my nerves will be shattered for weeks.”

“Penelope, what about you?”

“I’m sorry, Miss Rachel,” the maid responded shakily, speaking for the first time since we’d entered the room. “I was too busy battling off those horrid beasts of children. I have no idea where the woman went.”

Mrs. Blake glanced across the room to where her faithful retainer lay dozing. Choosing not to wake the old man, she turned her attention back to me.

“So you think it was the woman selling flowers?” she said.

“I certainly think it’s possible, miss. I can’t see who else it might be. Do you think you can you describe her?”

Mrs. Blake frowned. “She was a big girl. I remember that.”

“Very big. And certainly no beauty,” added her aunt. “A poor, ungainly thing, crouching on her haunches beside her basket. I recall seeing her pock-marked face and taking pity on her, which is why I insisted that we stop to buy a posy.”

“I don’t remember pock-marks,” Miss Penelope cut in, apologizing for the interruption, “but I have to say she wasn’t all that big.” On finding herself the center of attention, she quickly looked away. A moment later she was wringing her hands again.

“Of course, I could be wrong,” Mrs. Merridew admitted, “but I honestly don’t think that I am. You see, although I couldn’t say why, I was truly fascinated by the creature. There was something utterly compelling about her state of wretchedness.”

Miss Penelope’s objection aside, a picture was already beginning to form in my mind. “What color was her hair?” I asked. “And how was she dressed?”

“Coarse, dark brown shoulder-length hair, parted in the middle and pulled back into a bun,” the aunt reeled off excitedly, her distrust of me temporarily forgotten. “Yellow cap and ribbons instead of the usual headscarf affair. A light gray blouse, which hung from her shoulders like a sack, and a tattered, dark gray skirt. A filthy red shawl, one end of which she held across her mouth, I imagine to try to hide her scars.”

“I remember the shawl,” Mrs. Blake agreed, her nose wrinkling up at the thought. “I wouldn’t put it anywhere near my lips.”

“Broad-shouldered? Arms like hams?”

“Why, yes.”

“And softly spoken?”

“So softly spoken I could hardly make out anything she said,” Mrs. Blake replied. “Aunt Merridew had to ask the price of the posy several times.”

The old lady nodded in agreement.

“Kept her eyes averted? Never once looked at you directly?”

“Gooseberry? Do you know her?”

I was almost positive that I did, back in the Life. Everyone knew her—Big Bertha, they called her. Bertha, whose real name was Bert.

I can’t rightly say whether it was out of a sense of propriety or a sense of embarrassment that I chose to keep the delicate nature of Bertha’s gender to myself. Not that it mattered either way; the important thing was that we now had a lead.

Mr. Bruff wound up the meeting by promising the Blakes that I would follow up on it the very next day. He also requested they entrust him with the daguerreotype, as he had an idea of his own he wished to pursue.

“May I please take another look at it,” I asked on the cab journey back, remembering just in time his strictures over the use of the verbs can and may. He pulled it out and handed it to me, but I was sorely disappointed. I had hoped to divine some link between the people in the photograph and Big Bertha. But study it as I might, nothing came to mind.

The streets were deserted and bracingly chilly as I made my way homeward up the Gray’s Inn Road, stopping only to collect a couple of eel pies and some macaroons from the eating-house on the way. Turning east, I set off along the New Road, past the site of the old smallpox hospital. They’re in the process of building a railway terminus there, which locals claim will bring train-loads of people from Scotland—though why any of them would want to visit my own little part of the world was a complete mystery to me. But, ah, the wonders of living in the Golden Age of Steam, eh? Board a train in the morning in Edinburgh and disembark in the evening at King’s Cross!

I have lodgings off the Caledonian Road, or the ‘Cally Road’ as it’s commonly called. There’s talk of them erecting a cattle market up by the prison, but till then the Cally remains the principal route into Smithfield for every drover herding their cattle from the north. The area’s much quieter at night, mind, without a single cow’s lowing to be heard; so quiet in fact that, with your window open, you can hear the lapping of the nearby canal and the gentle thud of the coal barges moored up together in pairs.

That night, as I rounded the corner, I saw that my window was closed, but a flicker of light in the glass warned me someone was already home. I ran up the stairs two at a time and silently pushed open the door.

“Octavius!” came the shout of pure joy from inside.

A small, lithe figure of a boy cannonballed into me from halfway across the room, gripping me so tightly that I nearly let go of the pies. My younger brother Julius.

“Did you have a good day today, Octavius? Did you get to do anything interesting? We sold all the fish on the stall by four o’clock, so I got to come home early. I came straight here, Octavius, just like you said to do; I didn’t hang round. Did you bring us anything for supper? It doesn’t matter if you didn’t because I had a hot potato for my lunch.”

I wriggled out of his grasp and, like a conjurer, made a show of presenting him with the pies. His eyes lit up like beacons.

“Eel pies?” he cried, dancing with excitement. “You know they’re my favorite!”

We set the table and ate, both of us savoring for as long as we could the rich jellied meat in its crust. Afterwards I scoured the plates with cold ashes from the stove while Julius collected his supply of scrap paper—scavenged from the waste bins at the office—and then proudly retrieved his treasured pencil from the shelf.

“What word will we do tonight?” he asked.

“I don’t know…what word do you think will be useful?” This was a routine we repeated every night.

“How about ‘sprats’?” he suggested, after a moment’s thought. “We had sprats on the stall today.”

I carefully wrote down the word for him and he began to copy it. I sat and watched him as he wrote, his face set hard with concentration and his small, pink tongue sticking out. I could have spent a lifetime watching him that way, but eventually the candle burned too low.

We were up the next day before dawn, for we both had early starts; Julius off to his fish stall in Old Street, and me on my hunt to find Bertha. Bertha was a creature of habit, so I knew where he’d probably be, the day in question being a Tuesday. The flower market at Covent Garden.

The sun was still struggling to rise as I made my way down Drury Lane and into Long Acre, dodging wagons loaded to the brim with fresh produce. Although it was early, the piazza was crowded and the streets leading into it jammed. I passed stalls stacked high with cauliflowers and cabbages, swerving to avoid the bustling porters. Did my fingers itch to perform as they once had? No. But I did wonder if Mr. Bruff had given any thought to what he was asking of me, requiring me, as it did, to rub shoulders again with my former partners from the Life.

If I remembered correctly, Bertha’s pitch was on the west side of the square, at the rear of the Actors’ Church. Six years may have passed since I’d last seen him, but if I knew Bertha, he’d rather kill than give up such a desirable site.

And I was right. As I turned the corner, there he was. Dressed in gray and draped in his dirty red cape, his head bowed low to show off the bright yellow cap and ribbons he wore, he was squatting on the pavement and looking quite ungainly as he sorted through his basket full of flowers.

He must have seen my boots as I approached, for all at once he pulled his shawl across his mouth, bowed his head a little lower, and quietly began to mumble in a deep, hoarse whisper: “Buy a nice posy from a poor, honest woman, sir? Or a bouquet for your sweet, faithful wife?”

“Hello, Bertha.”

Big Bertha’s face shot up. “Oh, my Gawd, as I live and breathe!” he squawked. “I’d recognize those bulging big ogles anywhere! It’s you. It’s young Octopus, back from the dead or Van Diemen’s Land!”

Octopus. My other nickname.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 18th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or still too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Do let me know! A big thank you to Lara and Alice who have sent me feedback, but I’d love your feedback, too. Please use the comment box below.

Published on July 11, 2014 06:10

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Three

I like to think that I am a man of the world—or, to be more accurate, having attained the grand age of fourteen, I am now two-thirds of a man of the world—and I would have you know that in my time I have seen both men dressed as women and women dressed as men. Of these, some have been most convincing. Many have been less so. Bertha, I’m afraid, didn’t even make it into this category. There was nothing feminine or effeminate about him whatsoever. In a sense he was simply a big, jowly bloke in a dress. No wonder Mrs. Blake’s aunt had been fascinated by him. I’m sure she’d never seen anything like him in her life.

I like to think that I am a man of the world—or, to be more accurate, having attained the grand age of fourteen, I am now two-thirds of a man of the world—and I would have you know that in my time I have seen both men dressed as women and women dressed as men. Of these, some have been most convincing. Many have been less so. Bertha, I’m afraid, didn’t even make it into this category. There was nothing feminine or effeminate about him whatsoever. In a sense he was simply a big, jowly bloke in a dress. No wonder Mrs. Blake’s aunt had been fascinated by him. I’m sure she’d never seen anything like him in her life.“Look at you!” he cried, rubbing his eyes as if he’d seen a ghost. “My, ain’t you grown! Why, you’re almost a fully-fledged omi,” he said, meaning ‘man’ in palari, the actors’ slang he liked to use. “So where the hell you been, then?”

“Well, I wasn’t sent to some Australian penal colony, if that’s what you imagined.”

He blinked. “Wot, then?”

“I simply needed a break from the Life, that’s all.”

“But where d’you take yourself off to? Ain’t no one just disappears like that.”

No? I’d managed it pretty well up until now.

“I went to live in Edinburgh,” I lied.

“Edinbra?” He considered this carefully. “Ain’t that somewhere up norf?”

By the time I agreed that it was, he’d already begun to lose interest. Instead he was employing his critical eye to give me a quick once-over.

“Well, well, well! You’ve grown to be quite a looker, ’aven’t ya? You seeing anyone, then? If not, I’d be more than happy to—”

“No, Bertha, I’m really flattered, truly I am, but…”

“No, no, no! I ain’t talking about me!” He wagged a fleshy finger in my face. “You got to learn to lower those sights of yours, lad. No, I was trying to tell you ’bout this matrimonial bureau wot I runs now—strictly a sideline, o’ course. A young omi such as yourself, I could get you fixed up in a jiffy.”

“But what if I don’t want to be fixed up?”

He wasn’t listening. Something or someone had caught his attention on the other side of the piazza.

“’Ere, Florrie, get those scrawny little hips over ’ere! Octopus, I want you to meet Florrie. Florrie, this here’s Octopus.”

“Octopus?” The girl Bertha had summoned was gawking shamelessly at my eyes. “That’s an unusual name,” she said. She was dressed, as most of the market girls were, in a blouse and skirt, with a shawl draped over her shoulders. Her blonde hair was pulled back from her face and tied up with a black velvet band.

“Forget those bona big ogles, girl,” chortled Bertha, referring to my eyes. “It’s his lills you ought to be worried about. ’E’s got eight of ’em.”

“Eight?” Florrie’s gaze dropped to my hands in a panic. She gave a sigh of relief when she saw I only had two.

“This young omi used to troll through the streets lifting wallets left, right, and center—just like an octopus would if it ’ad any real appreciation of money! You keep your eye on him, girl, or his lills will be all over you in no time.” The girl blushed as Bertha gave a deep throaty chuckle. “First assignation’s free,” he continued, now addressing me, “it’s the second that’ll cost ya; strictly no third unless it’s a wedding!” Bertha gave me a big, theatrical wink. “Got to make it look proper, see; I won’t have no one thinking I’m procuring. Me, I’m a respectable woman!”

Florrie and I regarded each other in a state of nervous embarrassment. She looked almost alarmed; I’m sure I did too.

“Young people these days!” griped Bertha. “No sense of romance! Go on, Florrie, if he ain’t going to kiss ya, you may as well give us a hand with these posies.”

The two of them knelt on the pavement and began binding stems with green twine.

“So how’s the flower business going?” I asked. “Everything in the garden blooming?”

“Mustn’t grumble, mustn’t grumble,” he replied. “’Ere, wot do you think of my new line of patter?” He bowed his head, pulled his shawl across his mouth, and started whispering the same catchphrase he’d whispered before: “Buy a nice posy from a poor, honest woman, sir? Or a bouquet for your sweet, faithful wife?”

“It’s good. Really good.” It was a definite improvement on the one I remembered: ‘Varder me dolly flowers, sir.’—meaning, look at my pretty flowers—‘Get ’em quick before they die.’

Bertha grinned.

“I hear you were over on Wigmore Street yesterday,” I said.

The grin faded. “Oh? And where d’you hear that?”

“Some friends of mine were accosted…by a gang. The odd thing is, when I asked them about it, they managed to describe you perfectly.”

“Friends of yours, eh?”

“People I care about, yes.”

He took a moment to digest this. “Shame,” he said. “Seems like a poor, decent woman can’t go nowhere no more wiffout being set on by ruffians.”

“Wigmore Street’s a bit outside your territory, Bertha. And that got me thinking. This job had to be special—planned to order by someone much higher up.”

“Well, I wouldn’t know, ’cos I wasn’t there!” he bawled.

We eyed each other warily, like a pair of fractious circus tigers, until Bertha finally cracked and looked away. It wasn’t stalemate yet, however, for I still had one move left to me.

“So you weren’t the one who slipped the daguerreotype in the old lady’s bag?” I said.

For the second time in twenty minutes, Bertha’s pock-marked face shot up. Florrie, who’d been watching our little exchange with increasing discomfort, rose to her feet and announced she was leaving.

“No, you stay right where you are,” Bertha growled at her, even though he was glaring at me. “It’s young Octopus here wot needs to leave. Go on, Octopus—” And here he bellowed a two-word Anglo-Saxon phrase at me, causing everyone in the square to look.

I beat a tactical retreat into the bustling piazza, and hid myself behind a barrow-load of celery. I’d purposely kicked the hornets’ nest, and I wanted to see what Bertha would do next. I didn’t have to wait long. Leaving his stall in Florrie’s care, he threw his shawl over his shoulders and set off at a cracking pace down King Street. Despite the considerable number of pedestrians, he made an easy target to follow. His yellow cap and ribbons bobbed a good six inches above most of the heads in the crowd.

At the corner he turned north, as if heading towards Long Acre, but then pulled up short outside a public house. I knew the pub, but only by reputation: they regularly staged bare-knuckled prize fights there. It was the Lamb and Flag, referred to hereabouts as the Bucket of Blood. After a moment’s hesitation, Bertha went inside.

I crept up to the windows and peered in. Though the hour was still early, business was brisk, as it tends to be for any pub on a market day. I scoured the room, but there was no sign of Bertha. I stepped back a little and gazed up at the windows above. Was one of the old crew up there, holding court in a private suite? Perhaps even Ned himself, if he still happened to be in charge. How would he react when he heard I was back, I wondered?

It seemed as if I had a choice. Burst in and confront him, or whoever it was who was running things now—a strategy that hadn’t played so well with Bertha—or wait and see what would happen. I took a coin from my pocket and flipped it. Tails. Better to wait.

I returned to the corner and stood by the railings, watching and biding my time. Ten minutes passed, and then twenty. At last the door opened, and Bertha emerged.

I held my ground for a moment as he marched away, curious to see if anyone else would appear. When no one did, I sped off after him, just in time to see him cross the road into Bedford Street. At the Strand he turned left and began to head east, past Temple Bar into Fleet Street. The pavement here was not so crowded, so I could afford to fall back a little.

Still he trundled eastwards, past St. Paul’s, past London Bridge, then past the Tower. Now came the docks with their innumerable ships moored up in miniature cities. Gulls reeled and circled among the masts against the steel-gray, mid-morning sky. Surrounded by beer-bellied dockers, Bertha was in his element, lapping up the hoots and wolf whistles he’d started to attract.

Somewhere between the London Dock and the East London Dock, Bertha paused. He peered to his right, then took a road that led down towards the river. A few minutes later he made another quick turn, this time to his left. As I came round the corner, I saw that he’d reached his destination. He’d joined a small line of people queuing up outside an octagonal marble tower. As those in the queue were all dressed rather fashionably, Bertha stuck out like the proverbial sore thumb. So did the tower, come to that. Being new, and built of pale gray marble, it seemed truly at odds with the neighboring warehouses, all of which had seen better days. Gradually the line grew shorter and Bertha vanished within.

I followed a minute or so later, in time to see him picking a fight with a man in a ticket booth. “But it’s only a penny!” I heard the chap saying, as I popped my head round the entrance.

“A penny’s a penny!” growled Bertha. “And I’m not some damned sightseer; I’m ’ere on business! Now bleedin’ well let me in!”

Grudgingly the fellow complied, operating the narrow brass turnstile to allow him to pass.

I made my way across the blue and white tiled floor and handed over my penny. The man still looked livid from his encounter with Bertha, so I was dreading asking for a receipt—a matter of some necessity for me, for Mr. Bruff’s clerk who handles the petty cash claims is a tyrant where receipts are concerned. But before I’d plucked up the courage to do so, the man pressed some kind of lever, and I was forcibly propelled through the turnstile gates and spat out on the other side. I suppose I could have knocked on the back door of the ticket booth, but even I have my pride. In front of me loomed a doorway. Without knowing quite what to expect, I squared my shoulders and stepped on through.

I found myself at the top a circular shaft, lit entirely by gaslight. A lengthy spiral staircase descended forty feet or so to a marble floor below. Here and there, there were landings to break the descent, hung with paintings of palaces and waterfalls. There was even the odd plaster statue or two. Ghostly organ music echoed up from the depths, Rule Britannia, The Marseillaise, and a number of other tunes that sounded stirring enough, though I couldn’t tell you what they were. Below me, I saw that Bertha had nearly reached the bottom of the stairs. I quickened up my pace; I didn’t want to lose him in the crowd.

He barely glanced at the sideshow attractions dotted about the room (‘Your Fortune Told’, ‘The Egyptian Rune Reader’, ‘The Monkey Answers All Your Questions’), and made directly for the pair of tunnel entrances that stood opposite the stairs. Choosing the right-hand one, he set off down it, with me still in hot pursuit.

The tunnel seemed to stretch for as far as the eye could see. Strategically positioned gas lamps lit the way, and every so often there was a gap in the wall that allowed access from one tunnel to the other. Stalls selling various lines of cheap goods were set up in each of these gaps, staffed in the main by pallid young women, with skin that was even paler than mine. Ahead of me, Bertha drew up in front of one such stall and began to examine the merchandise. As I huddled against the tunnel wall, I felt a drop of ice cold water hit the back of my neck and trickle its way down my collar. By now I had a very good idea where I was.

Bertha was on the move again. As I passed the stall where he’d stopped, I glanced down at the ribbons he’d been inspecting. Each had the words ‘Souvenir of the Thames Tunnel’ woven through it. I’d been right. Here I was in the world’s first sub-aquatic tunnel, well below the bed of the Thames, with ten thousand of tons of water pressing down on me!

My moment of reflection came at a cost. When I looked up, Bertha had vanished.

He couldn’t have gone far, I reasoned; my attention had wavered for a few seconds at most. I kept going in the direction he’d been heading. To my left was another gap, this time with a stall selling magic lantern slides. Twenty yards on, there was another, this one a coffee shop decked out with tables, nearly all of which were occupied. An eccentric-looking waiter in a costermonger’s jacket, stitched with rows of mother-of-pearl buttons, weaved his way between the tables delivering drinks and light refreshments. Bertha couldn’t have got any further than this.

I moved swiftly through the underwater coffee shop, searching amongst the faces, till I came out in the adjacent tunnel. I peered up and down. Bertha was nowhere to be seen. I retraced my steps back to the shaft, checking each of the stalls as I went. As impossible as it seemed, Bertha had given me the slip.

I loitered at the base of the stairs and watched the procession of people. I made a tour of the room, and examined the organ that was churning out music. Driven by steam, it somehow managed to play itself. I considered consulting the monkey, the one that ‘Answers All Your Questions’, for I had several that were puzzling me deeply. The problem was his method. Two nuts were placed on a board before him; one on a square that said ‘yes’, the other on a square that said ‘no’. The nut he chose first indicated his answer. Is Bertha still in the tunnel? Is Bertha still in the right-hand tunnel? At a penny a shot, and with only yes-or-no answers to guide me, it could cost a small fortune to locate Bertha this way. I took out a coin, but it wasn’t for the monkey. Should I stay or should I go? I flipped it.

Heads. Stay, then.

I wandered back to the coffee shop, took a seat, and ordered a piece of cake from the man in the button-clad jacket. Idly I wondered where he kept his supplies, for he was doing a roaring trade.

The afternoon wore on. I began to notice that nearly everything in the tunnel cost a penny. It was rather clever, really; for the price of a couple of nice, fat herrings anyone could buy a piece of tat to remind themselves of their time spent down here. I bought a candle at one stall and moved on to the next, which just happened to sell writing equipment. It was staffed by a young woman with bright auburn hair, whose mouth gaped open in an undisguised yawn. I couldn’t resist following her example, and gave a big yawn myself.

“Who buys these things?” I asked, as I browsed through the pencils and dip-pens laid out on the white marble counter-top, each stamped with the brand, ‘Souvenir of the Thames Tunnel’.

“Tourists,” she replied without enthusiasm.

“How much?” I asked, selecting a fine looking pencil for Julius. “No, don’t tell me. It’s a penny, right?” I saw her eyes roll towards the ceiling. “Oh, and may I have a receipt, please?” I added.

“A receipt for a penny?”

“If you would be so kind…?”

She threw me a look of pure hatred.

Before too long the music ground to a halt, and stewards began to herd everyone out. “Ladies and Gentlemen! The Tunnel is closing in fifteen minutes. Please make your way to the exits!”

I didn’t need to be told twice. I nipped up the stairs and was outside in a shot. Night had fallen, but it couldn’t have been late. I took shelter in a nearby doorway and watched as people emerged—first the patrons, who took their sweet time about it, and then the staff (including the monkey), who were champing at the bit to get home. The waiter from the coffee shop had changed out of his jacket. He looked positively run-of-the-mill without it. The last person to leave was the man from the ticket booth; it was he who was in charge of locking up. He took the task seriously—he checked the doors twice before tucking his keys in his pocket. I followed him as he set off towards the river, making, as it turned out, for the nearest public house.

Retrieving the receipt for my pencil, I crumpled it a little (to add an air of authenticity), then ran up and tapped him on the elbow.

“Yes?” he said, peering down at me, as his fingers closed round the handle of the pub’s glazed door.

“Sir,” I addressed him in my most earnest voice, “I believe that you might have dropped this.” I held out the receipt for inspection.

He looked at it, recognized the commercially-printed header, and dismissed my claim with a wave of his hand. Then he pulled the door open and stepped into the pub, shutting me out on the footpath.

Though I kept my face blank, on the inside I was beaming, for I now had his full set of keys.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, July 25th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

So what did you think? Love it, or hate it, or still too early to tell? Find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on July 18, 2014 06:09

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, polari, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Four

Getting in was easy. The biggest key opened the main door. Once I was in, I locked it behind me and lit the candle I’d bought. I thought the turnstile might prove problematic, but for some reason the mechanism had been disengaged, and now it turned freely. By simple trial and error I found the key to the shaft, unlocked the door, and made my way down the stairs.

Getting in was easy. The biggest key opened the main door. Once I was in, I locked it behind me and lit the candle I’d bought. I thought the turnstile might prove problematic, but for some reason the mechanism had been disengaged, and now it turned freely. By simple trial and error I found the key to the shaft, unlocked the door, and made my way down the stairs.It was extraordinary the transformation that had taken place in little under an hour. Before the Thames Tunnel had seemed like a fairground; now, minus the gaslights, the organ, and the ebb and flow of the patrons, it felt more like an empty crypt. The only sound to be heard was the occasional pitter-patter of the river raining down from above.

I retraced my steps down the right-hand passage, keeping my wary eyes peeled. The marble counters had been cleared of their merchandise, so it was hard to gauge the distance I’d come. Ahead of me lay the coffee shop, its tables now bare. Though I had no idea where the rest of the tat had gone, I knew exactly where the coffee shop’s provisions were stored, for I’d kept a careful eye on the waiter every time he went to fetch more cakes.

I sent up a quick prayer to St. Quentin, patron saint of locksmiths, that one of my new-found keys would fit the storeroom door, for though there may be no swifter, slipperier pickpocket in all of London, I have to admit to a certain ham-fistedness when it comes to picking locks. I knew the theory, of course, but had always had a tough time putting it into practice.

I found the key on the fifth try, and felt the bolt slide back as the teeth engaged. Cautiously I prized open the door and took a look inside.

Running parallel with the tunnel, the room was narrow and long. It smelled overwhelmingly of coffee, and as I shone my candle around I spied a large cast-iron coffee grinder in the corner. Most of the space was taken up with shelving on which dozens of cakes—mainly Dundee cakes and Bakewell tarts—were stored. Further down there were bottles; fortified wines, by the looks of things.

Suddenly I heard a moan—a low muffled keening that originated at the far end of the room. I made my way towards it, and found Bertha trussed up like a chicken, with both his hands shackled to the wall. One side of his face had been beaten, so it was a bloodied, swollen eye that stared up at me in surprise.

“Octopus?” he said, once I’d fished out the filthy tea towel that was crammed in his mouth. “Wot the hell are you doing ’ere?”

“It looks as if I’m saving your hide,” I replied, glancing over my shoulder at the array of bottles.

“’Ere, where you going?” he demanded, when I left him to collect a few bits and pieces. I returned a moment later with a bottle of port and a knife.

“Careful with that,” he kept squawking, as I sawed through his ropes. “Oi! That’s my arm, that is!”

“Stop complaining! Here, take a swig of this.” I opened the bottle and held it to his lips. He drank noisily, guzzling the plummy, sweet liquid with obvious relish.

“Ooh, that feels better,” he sighed. “Now, how’s about getting me out of these?” He raised his shackled wrists to show me his handcuffs. Grimly I stared at the lock.

“Prepare yourself, Bertha. This may take me some time.”

It did, even when I’d found a nail to use as a pick. Back in the day, I really should have paid more attention to Billy the Shim when he tried to instruct me in the mysterious ways of locks. No slower, sloppier lock-pick in all of London hasn’t quite the same ring to it as my regular sobriquet, as true as it undoubtedly is.

Between Bertha’s many calls for further refreshment and my own frequent breaks to prevent my fingers cramping, I have no real idea how long it took me—but by the time I’d finally managed to spring the catch, my hands were aching, Bertha was paralytic, and the candle had burned to a stump.

“Here, Bertha, put your arm around my shoulder.”

I slipped a few choice items from the shelves into my jacket, and then, supporting him as best I could, we staggered to the door. But as it swung open I instinctively drew back.

Something was clearly wrong. The gaslights were lit, and one quick glance was all it took to establish that Bertha and I were no longer alone. When I say that there were young women on the counters, I mean they were literally seated on the counters. And parading back and forth in front of them, eager to sample their wares, were seedy, drooling men of all shapes and sizes—and of all ages and manner of dress, come to that.

Bertha began to giggle. “Looks like the night shift’s begun.”

“Night shift?”

“The Fair Maids of Wapping. ’Ospitality offered to gentry and sailors alike, every night except Sundays.” The words came out in intoxicated fits and starts. “Nice touch, that, about the Sundays—makes it look real proper. All Johnny’s idea.”

“Johnny?”

“You remember Johnny!”

I shook my head.

“Nah, ’course you do, Octopus. Johnny Knight. Goes by the name Johnny Full Moon these days—Johnny Full-Moon-Every-Bleedin’ Knight.”

“Johnny Knight’s running things now?”

Bertha nodded.

Oh, I remembered Johnny, all right. We’d risen up through the ranks together—me because of my skills; Johnny because he took risks…lunatic risks—hence the reference to the full moon, I imagined. Even when I eventually came to outrank him, I was always wary of Johnny, for Johnny Knight wasn’t just some mad risk-taker, he also had a nasty vicious streak. What, I wondered, had become of Ned, the man who’d been in charge when I was around?

“Bertha, listen; this is important! Will Johnny be here tonight?”

“Might be. Wot day’s it?”

“It’s a Tuesday.”

“Then, nah, nah, he won’t be. Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, they’re market days, see. He’ll be at the Bucket of Blood, overseeing ’is fights.”

“But these girls…they all work for Johnny?” They’d be bound to notice a fourteen-year-old boy and a man in a dress in their midst. The question was, what would they do about it?

As if reading my thoughts, Bertha pulled his shawl across the lower half of his face and steered me rather drunkenly into the tunnel.

“Concentrate, Octopus!” he whispered in my ear. “You’re an omi and I’m a palone,” by which he meant that I was a man and he was a woman. “Wot’s more natural than a young omi like yourself desiring my company for the evening? We’re just taking little walk together, see, to find some place a bit more private? Who could object to that?”

His plan seemed to be working. We’d made it all the way to the shaft before anyone clocked that something was amiss. The girl I’d requested a receipt from, the one with the auburn tresses, spotted me and began raising all hell.

“What’s he doing down here?” she shrieked, pointing in my direction. But the client she was with wasn’t having it; he clearly had other things on his mind. He grabbed her wrists, forced himself on top of her, and started smothering her cries with his kisses. The more she protested the more passionate he became. As quickly as I could—which was not quickly at all—I bundled Bertha up the stairs.

I had no idea what I would find at the top, but I prayed that it wouldn’t be the chap whose keys I had lifted. It wasn’t. It was some oily-haired toad-of-a-man, who, according to Bertha’s overly-loud whisperings, ran the ticket booth in the Rotherhithe shaft.

Now I had the problem of what I was going to do with Bertha, who’d begun to nod in and out of consciousness. I needed him to answer my questions, so I needed him sober and awake. My only option, it seemed, was to take Bertha home with me. As foolish and risky as this proposition appeared, I felt I had no other choice.

Reeling under his weight, I propelled him back towards the main road. I had very little money left, and doubted that any cabbies in this neck of the woods would recognize me as Mr. Bruff’s office boy and offer to take my fare on account. But I had a plan. First I had to find a cab—easier said than done—then I had to convince the driver to take us back to the Cally Road, a distance of some few miles, in exchange for a bottle of port. In the end I had to throw in a Dundee cake as well, to sweeten what was already a very good deal.

“Oh, Octopus, Octopus!” moaned Bertha, as Julius helped me to lower him on to my bed-roll an hour or so later.

“Why is he calling you that?” asked Julius, his eyes fixed nervously on Bertha. “And why is he wearing a dress?”

“Perhaps he’s in disguise,” I suggested, hoping that this might satisfy his curiosity.

“It’s not a very good disguise, Octavius.”

Looking down at the large, clumsy figure with the battered face, I could only agree. “No, it isn’t, is it? The truth is, Julius, Bertha thinks he’s a woman.”

“But he’s not a woman.”

“No, I know he’s not. But just try to understand that he thinks he is.”

My brother took a moment to consider this. “I’ll try. I’m not sure it will work, though,” he added, as Bertha started to snore.

“Hungry?” I asked, as I produced a second Dundee cake from my jacket.

“Starved!”

I cut two massive wedges and his smile became animated once more. As we ate, I quizzed him about the ‘panic word’ I had drilled into him from a very early age. With Bertha in our midst, my former life was now too close for comfort.

“Do you mean ‘Unnecessary’?” he said, his smile fading fast. “I don’t have to write it again, do I?”

“No, no,” I reassured him, remembering every bungled attempt that had featured too many c’s, and not enough n’s or s’s. “I just want to be sure that you’re clear about what you’re to do if I ever use that word in your hearing.”

“I’m meant to run, Octavius. Run as fast as I possibly can.”

I smiled. “And what are you supposed to do then?”

“Hide myself until night falls, then make my way back here.”

“And then?”

“Well, if you’re not here, or it’s not safe, or you don’t return by morning, I’m meant to go to Gray’s Inn Square and present myself to your employer, Mr. Bruff.”

“And if anyone tries to stop you from entering the building?”

“I dash past them—whoever they are. I run up the stairs and find Mr. Bruff’s office, which is halfway along the corridor. I knock respectfully—unless I’m being chased, in which case I rush in.”

“And what do you tell Mr. Bruff?”

“I tell him that I am your brother Julius, and that something bad has happened to you. If he doesn’t believe I’m your brother, I tell him to look at my eyes, for they should be proof enough.”

I beamed at him. “Here, I have a present for you,” I said, and handed over the pencil.

“Oh, thank you, Octavius! I love it! What does it say?”

“It says ‘Souvenir of the Thames Tunnel’”

“Does that mean we have to do a word tonight?” He glanced uneasily at Bertha.

“No, it’s late. You should get some sleep.”

Julius collected his bed-roll and laid it out as far away from Bertha as he could manage. I briefly considered falling asleep in my chair, but then thought better of it. I fetched my winter coat off the peg, spread it out like a rug in front of the door, and stretched out on top of it. If Bertha woke before me, there was no way he was getting out of here without waking me first.

In the event, I needn’t have worried, for it was Julius who woke me when he was leaving for work. Bertha was also awake. He sat slumped over the table, cradling his head in his hands. He glanced up at me as I joined him, and let out a mournful groan.

“’E’s got your ogles” he said, gingerly tracing the cut on his cheek with the tip of his finger. “Is ’e your brother, then? If he ain’t, he ought to be. ’E’s like this tiny, little you. Oh, gawd, me head bleedin’ hurts!”

“Who did this to you, Bertha?”

“That omi…the one wot calls himself ‘The Client’.”

“What on earth did you do to make him beat you and chain you up?”

“I don’t know, do I? Johnny sent me to give him a message. I give him his message—and everything’s sweet—then all of a sudden he turns round and whacks me in the face!”

“What message, Bertha?”

“Well, you know, just what you told me…how it’s really the old lady wot’s got the duggairiotype now. And I says, ‘It must be a damned good likeness, to go to this much trouble getting it back.’ Next thing you know, he whacks me in the eek!” Bertha sniffed. “They’re not always bona likenesses, see, and I know that for a fact. You remember Pan-faced Dora? The palone with the mole, wot she claimed was a beauty spot?”

I was forced to admit that I did. There’d been a cruel, heartless saying about Dora’s beauty spot, how it was in fact the only spot of beauty that Dora possessed.

“Well, each week Dora would put a little something aside from her earnings, and, when she’d saved up enough, she and ’er girlfriend went and got their pictures took. When she showed it to me, I couldn’t believe me ogles. Dora’s mole had upped and moved itself over to the other cheek! Never told her, mind. It would have had her spitting nails.”

“Bertha, I need you to be honest with me…it really wasn’t you who put the daguerreotype in the old lady’s handbag?”

Bertha sighed and shook his head. “Of course it wasn’t, Octopus. I was the one wot was meant to lift it, see? But I never got the chance. The mark must’ve ditched it in the old girl’s bag, so, when it came down to it, she never had it on ’er.”

“The mark?”

“The girl—the one we was meant to follow. The feelie palone wot was carrying the duggairiotype round with her.”

“Girl? What girl?”

He tutted. “The one wot works as a lady’s maid. She was the one that the Client hired us to lift it from.”

Lady’s maid? Surely he couldn’t be talking about Miss Penelope? No, it was unthinkable. And yet, when I did think about it, it was the only way that this thing made sense.

Though I still couldn’t quite bring myself to believe it fully, I was sure of one thing. Bertha was telling me the truth.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, August 1st.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry, but be warned, as this week’s post reflects on the process of writing, it contains spoilers.

So what did you think? Did you love it, or hate it? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on July 25, 2014 06:11

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialzation, thames-tunnel, wilkie-collins

Gooseberry: Chapter Five

“Where was you yesterday?” George hissed into my left ear, as he trudged beside me down the corridor in the direction of Mr. Crabbit’s office.

“Where was you yesterday?” George hissed into my left ear, as he trudged beside me down the corridor in the direction of Mr. Crabbit’s office.“Yes, where was you?” echoed his namesake in my right. “We was made to run errands!”

“That’s right. Errands. All of them!”

I thought about different ways to respond to this—including (but not limited to, as Mr. Bruff would have me add) the obvious, the fact that, as office boys, this was their job—but then it suddenly dawned on me. If I wanted to cause a reaction, why not tell them the truth?

“George, George, if you really want to know, yesterday Mr. Bruff paid me to sit in a coffee shop and eat cake.”

“You was eating cake while we was running us-selves ragged?”

“Uh-huh.”

“And Mr. Bruff was paying you?”

“Well, he will have paid me as soon as I claim back my expenses,” I said. And, with that, I pulled my receipts from my pocket and knocked briskly on Mr. Crabbit’s door.

A crotchety voice called out, “Enter!”

To rub salt into their wounds, I purposely left the door ajar as I strode into the petty cash clerk’s tiny sanctuary, so that George and George would be able to witness the transaction for themselves. As it turned out, this was a gross miscalculation on my part.

Mr. Crabbit inspected each of the three receipts I handed him as if he were a judge assessing the admissibility of evidence in a murder case.

“What’s this, boy?” he asked.

“It’s a receipt for a pencil, sir. I had to buy a pencil in order to make some notes.” The way I saw it, I had bought the pencil for my brother out of my own pocket; I was simply using the receipt in lieu of the one I had failed to get at the ticket booth.

“I can see it’s for a pencil, boy. No, look again. Look carefully. What’s this?”

“It’s crumpled?”

He smiled and lowered his spectacles on to the bridge of his nose. “Yes, it’s crumpled.”

“So?”

“Observe, boy.” Without turning to look himself, he raised a short, bony finger and pointed to the sign that hung behind him on the wall:

No illegible receipts

No indecipherable receipts

No torn receipts

No crumpled receipts

No defaced receipts

No stained or water-damaged receipts

No receipts with additions or alterations

No receipts that require further explanation

A burst of muffled sniggering wafted through the doorway. Mr. Crabbit rose from his desk like a whirlwind—not an easy task for a slight, balding man of his particular stature—and pulled the door open as if he were about to rip it off its hinges, unstoppable force of nature that he had become.

“George and George. Why am I not surprised? Well? What do you require?”

“N-nothing, sir.”

“N-no, sir, nothing.”

“Then be about your business, both of you, before I report your idleness to Mr. Bruff.”

Mr. Crabbit shut the door and calmly returned to his desk.

Having collected my money, but only for the cake and the candle, I made my way up the stairs to Mr. Bruff’s office. The Georges were perched on the bench outside. They scowled at me as I knocked and entered.