Gooseberry: Chapter Eight

Mr. Hook—esquire—’s diary was only helpful to a point. As he had started it on New Year’s Day, there were only twenty-two entries in total. Each of these was made in small, cramped writing, and most featured items of news copied from newspapers, such as ‘Royal Mail’s Amazon burns and sinks in the Bay of Biscay’ or ‘Transvaal receives its independence’—various goings-on from around the world, with all the place names underlined twice.

Mr. Hook—esquire—’s diary was only helpful to a point. As he had started it on New Year’s Day, there were only twenty-two entries in total. Each of these was made in small, cramped writing, and most featured items of news copied from newspapers, such as ‘Royal Mail’s Amazon burns and sinks in the Bay of Biscay’ or ‘Transvaal receives its independence’—various goings-on from around the world, with all the place names underlined twice.Every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday was marked with the letters ‘BOB’, followed by a set of figures that obviously referred to an amount of money. Some days the amount recorded was positive, some days negative. This stumped me at first—in fact to begin with I assumed ‘BOB’ was a name—but then I realized all the labeled days were Covent Garden market days, when the Bucket of Blood held its bare-knuckle fights. Mr. Hook, it seemed, liked a bet. Presumably this was how he’d met Johnny in the first place.

The parts that will be of greater interest to you (and the parts that were of greater interest to me) were even harder to make sense of, for all were written in abbreviated script, like this snippet from January 1st:

‘Our recs. show Thos. Shep. Broth. in service Port. Pl. res., name of Jas. Have J. F. M. set watch on ho. in case Thos. left port. w/ Jas.’

By working backwards from incidents I could identify, I was eventually able to expand it to this:

‘Our records show that Thomas Shep[herd?] has a brother in service at a Portland Place residence—Mrs. Merridew’s residence, on the face of it—who goes by the name of James. Have Johnny Full Moon set a watch on the house in case Thomas left the portrait with James.’

As far as I could tell, this whole affair had started with Thomas, an unknown entity, who’d given the daguerreotype to his brother, James, for safekeeping. I’d bet two pairs of boots that this James was the footman who, claiming the need to tend to his sick brother, gave Mrs. Merridew his notice.

Had Thomas stolen the portrait from Hook? Though this was unclear, there was one thing I was certain of. He’d gone to extraordinary lengths to make sure Mr. Hook did not get it back. The daguerreotype was obviously the key to this business.

But how had Miss Penelope come by it? Two identical entries on Sundays 4th and 11th provided a tantalizing hint:

‘Jas. S. meets girl Rgnt’s zool. gards. monk. ho. 2.30 pm.’

Translation:

On both dates, James Shep[herd?] met a girl—Miss Penelope, given the nature of later entries—in or by the monkey house at Regent’s Park zoological gardens at 2.30 pm.

She’d been seeing James on her afternoons off, and quite regularly it seemed. When Johnny’s lot was sent to deal with him, James gave her the portrait to look after before quitting Mrs. Merridew’s service.

There was one entry that especially worried me—the penultimate one, as Mr. Bruff would have me call it:

‘Freak escpd. Tell J. F. M.: need to be dealt w/ termin. Entry into Port. Pl. res. set for tonight.’

There wasn’t a chance in a million that the escaping freak could be anybody but Bertha. But why, exactly, was it necessary that he be dealt with terminally?

What was it Bertha had said? “I give him his message—and everything’s sweet—then all of a sudden he turns round and whacks me in the face!” What had caused this sudden fit of rage? What had Bertha seen or done to make Mr. Hook want him dead?

I was in two minds whether to tell Bertha about this. In the end I thought it best he be warned, so I broached the subject with him as soon as Julius left for work.

“Looks like I’ll need a disguise, then,” was his only response.

When I got to the office that morning, I barely had a chance to top up my per diem before Mr. Bruff was calling for me. Within minutes we were outside, climbing into a cab.

“This came this morning,” he said, handing me a letter as the cab rumbled south towards the Strand:

Cole Park Grange Asylum,

Twickenham.

January, 22nd inst.

Sir,

With reference to your recent inquiry, I regret to inform you that Dr. Login is currently abroad, and cannot be contacted for the foreseeable future. However, if you would care to visit, I am happy to place myself at your disposal if you think I can be of help to you in any regard.

Yours humble servant,

Mr. Cyrus Treech,

Director in Dr. Login’s absence.

“Sir, what do you hope to achieve by seeing the doctor’s second-in-command?” We were crossing Waterloo Bridge at this point, and the cab had just pulled up at the toll gate.

“Perhaps he will be able to throw some light on this,” he replied, pulling the daguerreotype from his pocket.

My heart sank. I knew that possessing the portrait was dangerous, and the fewer who knew that he had it, the better. But how was I going to warn him of this without telling him what I’d found out?

“Mr. Bruff,” I began, “after we parted yesterday, instead of returning to the office I went to follow up a lead I’d been given. It turns out you were right: there are two rival gangs at work here.”

“I knew it!” he cried, elated to find out he’d been right.

Well, it was true after a fashion. I slowly went through the whole story for him, substituting the word ‘gang’ for any involvement by Miss Penelope, the footman James, or Thomas, James’s shadowy brother. Mr. Bruff listened attentively as we boarded our train at Waterloo. He was still listening attentively as we sped our way westward towards Twickenham.

On arrival, we were told that Cole Park Grange Asylum lay within walking distance from the station. The air was as crisp as an autumn apple as we crunched our way along the gravel path. Soon we came to a pair of wrought-iron gates set into a high brick wall. Inside the gates there stood a tiny hut, where a guard was stationed on duty. Mr. Bruff stated our business and the man let us in.

Cole Park Grange Asylum was a sprawling two-storied building set in several acres of grounds. Some attempt had been made at landscaping, though there was nothing as formal as an actual garden. Rather, the sweeping lawn had been broken up in places with the occasional tree or a few lonely shrubs. To my mind, it made the estate look windswept. On the journey up to the house, I counted five of the doctor’s patients standing about on the lawn, looking for all the world like they too were part of the design.

On entering, we were shown to the doctor’s study, and told that Mr. Treech would join us presently. Before very long, the door opened and a gentleman in his late forties entered the room. His face was clean-shaven, his hair was brushed back, and his eyes gleamed warmly behind a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles. His skin was deeply tanned—not quite as dark as Mr. Murthwaite’s, but he’d certainly seen the sun quite recently—and he was dressed rather finely in a well-cut jacket. He came forward and gave Mr. Bruff’s hand a hearty shake.

“Welcome, sir, to Cole Park Grange.” He seated himself behind the large mahogany desk. “I am Mr. Treech, Dr. Login’s assistant. Perhaps you have come to see the good works we do here? As you’re no doubt aware, Dr. Login is a specialist in ailments of the mind—delusions, sir, feeble-mindedness, and despair.”

“Mr. Treech, my name is Bruff.”

“Ah, Mr. Bruff! Of course! You wrote requesting an audience with the good doctor. Unfortunately he’s away traveling—somewhere up near the Prussian border, I believe. But perhaps I can be of assistance?”

“The matter we are here on is a delicate one, I fear.”

“Indeed?” A look of inquisitive bemusement appeared on Mr. Treech’s face. He tilted his head to one side.

“I have been led to believe that Dr. Login acts as guardian to the Maharajah of Lahore.”

Mr. Treech smiled. “Yes, that is quite correct.”

“I wished to inquire about a certain daguerreotype that was made—a portrait of Dr. Login with the maharajah at his side. It recently came into the possession of a client of mine in a highly unsatisfactory manner.”

“Unsatisfactory?”

“Highly unsatisfactory,” repeated Mr. Bruff, refusing to go into detail.

“Do you have the portrait with you?”

I glanced at my employer, wondering if I’d managed to persuade him of the threat the daguerreotype posed.

“No,” he said, after a moment’s pause, “I have deposited it with my bank for safekeeping.”

Mr. Treech shrugged. “Then I’m afraid I cannot help you.” As Mr. Bruff and I rose from our chairs, he suddenly raised his hand. “But perhaps there is someone who can.”

“Who?”

“Why, His Highness himself, sir. The Maharajah of Lahore.”

“The maharajah is here?”

“Not in the house, no; this building is reserved for patients. The maharajah resides in the doctor’s private quarters, which are located elsewhere on the grounds. I can take you to him, though I can’t guarantee he will see you. His Highness is a very private person.”

“We would be indebted, sir.”

Mr. Treech led us down a passage and out through a door into the stable yard at the back.

“Before its conversion into a hospital,” he said, pointing to the delivery of vegetables we could see being made at the kitchen door, “this house used to have its own tenant farmers. Although no longer tied to us directly, they still keep us supplied with fresh produce. Dr. Login believes that the first requirement of a healthy mind is a healthy body. We serve only the best, nutritious food here.”

We rounded the stable and followed a rutted dirt track, which brought us to another set of gates. Beside it stood an old gatehouse, with small leaded windows, roses round the door, and a low trellis fence at the front.

“Dr. Login had the interior refitted before he moved in. It is truly most charming inside. If you will please follow me?”

He opened the gate, walked up to the door, and knocked. After a brief interval, a man who was somewhat younger than Mr. Treech appeared. When he saw Mr. Treech standing there, he held the door open and ushered us in.

“How is His Highness today?” Mr. Treech inquired, as we all removed our hats.

“Fair to middling, sir,” the young man replied, taking Mr. Treech’s and Mr. Bruff’s, but leaving me with mine. Oh, the joys of being socially inferior. “At the moment he’s practicing his letters.”

“Will he receive us, do you think?”

“I couldn’t rightly say, sir.”

“Well, we can but try.”

We followed Mr. Treech up the stairs, to a doorway halfway along the short corridor at the top. He tapped gently and waited. Upon receiving no reply, he gently pushed the door open. I edged my way in between him and Mr. Bruff, so I might see what they could see.

At the far end of the room, a brown-skinned boy my own age was seated at a table. Light from the window fell sideways across his face, casting one side of it into shadow. He had been in the process of writing something, for a dip-pen was poised in his right hand. He regarded the three of us thoughtfully, before at last settling on Mr. Treech.

“Why do you disturb me?” he asked, his warm, sultry voice almost singing out the words.

“Your Highness, this gentleman is Mr. Bruff. He wishes to beg an audience.”

The boy studied my employer for a moment. Then he smiled. “No, I will speak with him,” he said.

He was pointing at me.

I thought Mr. Bruff might have an apoplexy, but instead he put his hands on my shoulder and propelled me into the room.

“Your Highness,” Mr. Treech protested, “this is highly irregular!”

“I have made my decision,” the boy replied. “If you worry for my safety, you may, of course, leave the door open…as I am sure you will.”

He placed his pen on the table and rose, then came forward to greet me. “Welcome,” he said, putting his hand out to me. “What is your name?”

“Octavius,” I said, tucking my hat under my left arm, then grasping his hand and shaking it, “though most people call me Gooseberry.”

“Gooseberry? What an odd name. And yet it suits you. And where do you live, Gooseberry?”

“In London, sir. Just off the Caledonian Road—near where they’re building the new railway terminus.”

“A railway terminus? How very fascinating and modern. Come. Come see what I am doing.”

He led me to the table and offered me a chair. Resuming his seat, he turned the sheet of paper around so I could see it. Written repeatedly in flowing script was the phrase: ‘Duleep Singh, Maharajah of Lahore, former leader of the great Sikh Empire.’

“I am learning to write your English,” he explained.

“You write it very well, sir,” I said, and he smiled. I wanted to tell him that I was teaching my brother to write, but that would have involved talking about Julius in Mr. Bruff’s hearing. I settled instead for partial lie. “I teach my neighbor’s boy,” I said. “Each night I give him a different word, and he sits and practices it.”

“Oh? And how is that going?”

“Honestly? Very, very slowly, though he tries his best.” I could feel Mr. Bruff’s eyes on me, willing me to move on to the subject of our visit. “Your Highness, we have come to ask you about a portrait you had made, a daguerreotype that has recently come into our possession—”

“No! We will talk about writing English! Give me a word!”

“What?”

“Each night you give your neighbor’s boy a word. Give me a word and I shall write it.”

I scratched my head. “What word do you think will be useful?”

“‘Sovereignty’,” he said at last, “since I no longer have sovereignty over my own people.”

He offered me a fresh sheet of paper. I dipped his pen in the inkwell and began to write the word out. As I slid it back across the table, I wondered what Julius would make of this term, with its tricky vowels that could all too easily be transposed, and its ‘ign’ just begging to be written as ‘ing’.

I studied the lad’s face as he wrote. He was as handsome in real life as he was in the photograph, his flawless skin only marred by the short, angry-looking scar that ran from the far corner of his right eye down to the top of his cheek.

“There,” he said, dashing off the ‘y’ with a flourish, “how is that?”

I rose from my seat and went and peered over his shoulder.

“You’ve transposed the ‘i’ and ‘e’,” I said, and he looked up with a frown. “This letter here, and this one here…they should be the other way round.”

As I lowered my head to point to them, he unexpectedly whispered something in my ear:

“When you go, leave your hat behind. Trust me. I promise to return it.”

His eyes met mine, and for the briefest instant they burned intensely. Aloud he said, “This is a most difficult word. I will need to practice it. Sit.”

Aware that I was still being watched from the doorway, I casually propped my hat upon a chair, the back of which I judged would hide it neatly from view. That accomplished, I went and sat down again. For five minutes the boy worked in silence. Then he placed his pen on the table in front of him, and smiled at me.

“I have enjoyed your company, Gooseberry, and I thank you for teaching me a new word. But now I should like to rest.”

I rose and gave a little bow, then turned and walked towards the door. Just as I reached it, however, Mr. Treech cleared his throat.

“You’ve forgotten your hat,” he said.

“So I have,” I agreed unhappily, and went to retrieve it. As I picked it up, I noticed the boy. His features had frozen on his face. Then he rallied a little. He stood up and walked towards me.

“It was a pleasure to meet you,” he said, and reached out to shake my hand again. I could feel the tension in his body—his shoulders were perfectly rigid. And then he suddenly relaxed. As I turned to go, I even thought I saw a smile.

The man who had opened the door to us was waiting to show us out. He fetched the two hats he had taken and handed them back to their respective owners. We were just on the verge of leaving when the young maharajah came bolting down the stairs.

“Gooseberry,” he said breathlessly, “I believe that you dropped this.”

In the palm of his hand was my handkerchief, embroidered the letters ‘O. G.’. I got an overwhelming feeling that Mr. Treech would have snatched it from him then and there, had such an action not seemed wildly inappropriate.

“Isn’t that the one I gave you for Christmas?” asked Mr. Bruff, who was also peering at it with interest. He seemed pleased to see that I was actually using it, and hadn’t yet consigned it to the rag and bone.

“It is, sir,” I replied, as the boy pressed it into my hand. The question was, how on God’s good earth had he come by it? I’d certainly had no cause to take it out during the time I spent in his room. Which only left one possibility, as implausible as it might sound. The Maharajah of Lahore was a pickpocket. A pickpocket just like me.

I also had a good idea why he’d returned it, for through its folds I could feel the unmistakeable texture of paper. The thieving maharajah had used it to smuggle me a note.

Gooseberry continues next Friday, August 29th.

Copyright Michael Gallagher 2014.

You can follow Michael’s musings on the foolhardiness of this project. Just click on this link to his blog: Writing Gooseberry.

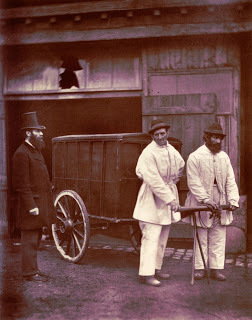

Photograph: Public Disinfectors by John Thomson, used courtesy of the London School of Economics’ Digital Library under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

So what did you think? Did you find any typos or continuity errors? Please let me know—use the comment box below.

Published on August 22, 2014 06:09

•

Tags:

gooseberry, michael-gallagher, moonstone, octavius-guy, sequel, serialization, wilkie-collins

No comments have been added yet.