Michael Gallagher's Blog - Posts Tagged "houdini"

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Caught on camera—the darker role that photography played in spiritualism

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.It probably started out as a happy accident: a glass plate that had previously been exposed but not yet developed was placed back into the camera and exposed for a second time. The resulting double-exposure, when printed, would have produced a somewhat ghostly effect. With a certain amount of pre-planning and a little tweaking here and there, the effect could be heightened and repeated time and time again. Such is undoubtedly the case with the American William H. Mumler (1832-1884), who started out as an amateur photographer in Boston. Realising that he could make his living by photographing New England’s many mediums in the company of assorted spirits, he quit his job as an engraver and moved to New York in the early 1860s to take up his particular brand of photography full time. His most famous photo appears to show Mary Todd Lincoln flanked by the spirit of her dead husband.

In the April of 1869 Mumler was brought to trial for fraud after it was alleged that he’d broken into houses to steal the portraits of his sitters’ dead relatives. One of the witnesses to testify against him was the showman and entrepreneur P. T. Barnum. Barnum had commissioned the photographer Abraham Borgadus to make a portrait of him accompanied by Abraham Lincoln’s spirit, just like Mary’s, to demonstrate how easily it was that such photos could be faked. The photograph was presented in evidence at the trial. Although Mumler was eventually acquitted, his career as a spirit photographer was over.

How could people be so gullible? To answer this question it's important to appreciate the naivety of the general public in their ability to read and understand photographs at the time. The following extract is from Statement of a Photographic Man, from Volume 3, Part IV (Street artists) of Henry Mayhew's 1861 work, London Labour and the London Poor. The speaker is a young working-class man from the slums of Lambeth, who, on tiring of busking for his living, borrows money for a camera and darkroom equipment and sets up as a photographer with his mate Jim, though both men lack the technical expertise required. Through trial and error his work gradually improves, but along the way he dreams up a number of hilarious tricks and dodges to mask his failures, one of which, the fobbing-off on impatient customers of hastily-wrapped specimen-photographs taken from his window display, he discusses here:

"…We have made some queer mistakes doing this. One day a young lady came in, and wouldn't wait, so Jim takes a specimen from the window, and, as luck would have it, it was the portrait of a widow in her cap. She insisted on opening, and then she said, 'This isn't me; it's got a widow's cap, and I was never married in all my life!' Jim answers, 'Oh, miss! why it's a beautiful picture, and a correct likeness,'—and so it was, and no lies, but it wasn't of her. Jim talked to her, and says he, 'Why this ain't a cap, it's the shadow of the hair'—for she had ringlets—and she positively took it away believing that such was the case; and even promised to send us customers, which she did.

"There was another lady that came in a hurry, and would stop if we were not more than a minute; so Jim ups with a specimen, without looking at it, and it was the picture of a woman and her child. We went through the business of focussing the camera, and then gave her the portrait and took the 6d [half a shilling]. When she saw it she cries out, 'Bless me! there's a child: I haven't ne'er a child!' Jim looked at her, and then at the picture, as if comparing, and says he, 'It is certainly a wonderful likeness, miss, and one of the best we ever took. It's the way you sat; and what has occasioned it was a child passing through the yard.' She said she supposed it must be so, and took the portrait away highly delighted.

"Once a sailor came in, and as he was in haste, I shoved on to him the picture of a carpenter, who was to call in the afternoon for his portrait. The jacket was dark, but there was a white waistcoat; still I persuaded him that it was his blue Guernsey which had come up very light, and he was so pleased that he gave us 9d [three-quarters of a shilling] instead of 6d. The fact is, people don't know their own faces. Half of 'em have never looked in a glass half a dozen times in their life, and directly they see a pair of eyes and a nose, they fancy they are their own.

"The only time we were done was with an old woman. We had only one specimen left, and that was a sailor man, very dark—one of our black pictures. But she put on her spectacles, and she looked at it up and down, and says, 'Eh?' I said, 'Did you speak, ma'am?' and she cries, 'Why, this is a man! here's the whiskers.' I left, and Jim tried to humbug her, for I was bursting with laughing. Jim said, 'It's you ma'am; and a very excellent likeness, I assure you.' But she kept on saying, 'Nonsense, I ain't a man,' and wouldn't have it. Jim wanted her to leave a deposit, and come next day, but she never called…"

The photographs of the spirit of Katie King, however, stretch credulity to a brand new level. The first set was taken in a hotel room at Florence Cook's request by the reporter W. H. Harrison with an eye to publication in The Daily Telegraph; the rest—the ones we're most familiar with today—were taken by the scientist William Crookes at two private but well-attended soirées in his own home. In both cases neither the negatives nor the prints were tampered with in any way, and, considering the circumstances, it seems unlikely that Crookes (if not Harrison too) set out to perpetrate any fraud. But, studying them, it's hard to imagine that anyone was fooled. The words of Edward William Cox when describing one of Katie's later appearances sum up the situation neatly, "They were solid flesh and blood and bone."

People see what they want to see. The photo you see below is another interesting case in point. It was taken by a sixteen-year-old in 1917 and features her nine-year-old cousin sitting in their garden surrounded by a number of posed, cut-out fairy figures.

Again, there is no double-exposure or tampering with the print. What you see is exactly what you get. Yet this image was passionately championed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series, who, despite his naivety, was a great believer in spiritualism. And he was not the only person to be taken in. Here is what Edward Gardner, a leading member of the Theosophical Society at the time, had to say: "…the fact that two young girls had not only been able to see fairies, which others had done, but had actually for the first time ever been able to materialise them at a density sufficient for their images to be recorded on a photographic plate, meant that it was possible that the next cycle of evolution was underway."

Frances, the young girl in the photo, finally admitted to the fraud in later life: "I never even thought of it as being a fraud—it was just Elsie and I having a bit of fun and I can't understand to this day why they were taken in—they wanted to be taken in."

Fifty years after Mumler, professional debunkers—often stage magicians who objected to their artistry being brought into disrepute by spiritualist hoaxers—were still at work trying to expose the tricks involved in the production of spirit photography. Here is one of the most recent examples I could find, showing Houdini, one of the greatest escapologists and debunkers of all time, with (yet again) the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, who must surely be the most photographed "spirit" on the planet.

Next time: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.Images:

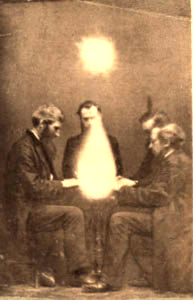

Seance conducted by John Beattie, in Bristol, England

Photograph by Eugene Rochas, 1872

Mary Todd Lincoln with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln

Photograph by William H. Mumler, date unknown but presumably prior to 1869

P. T. Barnum with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Barnum's request

Photograph by Abraham Bogardus, 1869

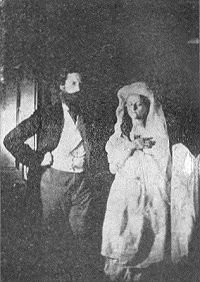

William Crookes with the spirit of Katie King

Photograph by William Crookes, circa 1873

Frances Griffiths surrounded by fairies

Photograph by Elsie Wright, 1917

Houdini with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Houdini's request

Photographer unknown, circa 1920-1930

Library of Congress

Published on February 01, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

barnum, crookes, florence-cook, houdini, lincoln, mayhew, mediums, mumler, pictures-of-ghosts, seances, spirit-photography, spiritualism, spiritualists, statement-of-a-photographic-man, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.So far in this history we've already encountered a number of ghost-grabbers: Noah Brooks, the American journalist with the Sacramento Daily Union, who literally grabbed the trance medium Lord Colchester's hand at a séance instigated by Mary Todd Lincoln, and the English lawyer, William Volckmann, who seized the spirit of Katie King by the waist and refused to let go—despite being tackled by two of Florence Cook's confederates who were stationed in the audience, one of whom she ended up marrying a mere four months later. Both instances were brutal and bloody. Brooks received a blow to his forehead with a drum that Colchester used in his performance; Volckmann, who was in league with the medium Agnes Guppy—one of Florence's rivals—had part of his beard torn away. Florence was ghost-grabbed again some years later, you may recall, this time by the twenty-year-old Sir George Sitwell at the assembly rooms of the National British Association of Spiritualists in 1880. It spelled the end of her career. She was forced to retire and move to Wales.

Another victim to be caught out several times was the medium Henry Slade (1835-1905), who was noted for his chalked spirit messages that would "miraculously" appear on a conveniently-held slate. Having been twice unmasked as a fraud in America (first by John W. Truesdell in 1872, then by Stanley LeFevre Krebs), he came to Britain to ply his trade. Here he was thwarted by Ray Lankester (1847-1929), a twenty-nine-year-old professor of zoology at University College London, who in 1876 snatched the pre-inscribed slate from the medium's grasp. Slade was brought to trial and found guilty of fraud, but successfully appealed his conviction on a technicality, that the original charge had omitted the words "by palmistry or otherwise". Before fresh charges could be brought he'd fled the country and returned to America.

Ghost-grabber Lankester was one of a growing group of scientific men, as was William Benjamin Carpenter (1813-1885), a colleague of his who had recently been appointed Registrar of the University of London, and Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow (1844-1913), an alienist (an early form of psychologist), all of whom were beginning to challenge the most basic precepts of spiritualism, possibly as a reaction to William Crookes's reviled report, Notes of an Enquiry into the Phenomena called Spiritual, published some two years before Slade's trial. Winslow (or Forbes-Winslow, as he eventually came to style himself) used red ink in pursuit of charlatans. He would squirt it in the faces of any spirits that happened to materialize in his presence. He's a fascinating character who I will return to in the next post.

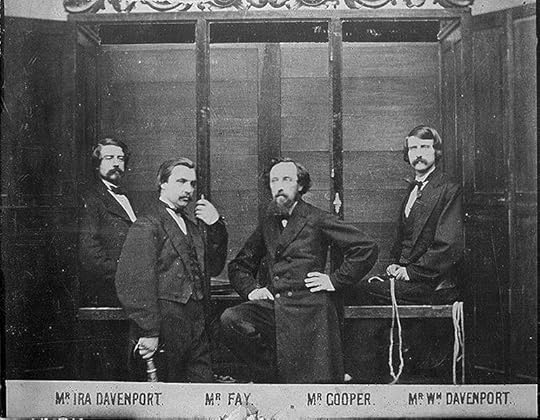

But it wasn't just scientists who worked to unmask frauds. It was often stage magicians who proved far more ruthless as opponents. Even by the mid-1860s a professional hatred had emerged that separated stage magicians, who claimed no spiritual intervention for their illusions, from spiritualist mediums, who did. Such was the case with the two Davenport brothers, Ira and William, who like Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home before them, came to Britain from America either at the end of 1864 or the beginning of 1865.

Ira Davenport was born in the September of 1839; his brother William was born less than two years later in 1841. They were the sons of a policeman and grew up in Buffalo, New York. They claimed to have discovered their mediumistic powers when Fox-style rappings broke out at their house in 1846, two years before those of the Fox sisters, when Ira was seven years old and William barely five. By 1854, when both boys were still teenagers, they had already come up with the basic building blocks of their act. Managed by their father, tutored by a local amateur conjurer, William Fay, and introduced on stage by Dr J. B. Ferguson, a former minister of religion who truly believed in the brothers' spiritualistic abilities, they started giving shows across America, from which they earned their living for the next ten years.

While the séances of Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home may have relied rather heavily on creating a specific eerie atmosphere where people's heightened senses would cause them to jump out of their skin at the slightest unexpected sound, the Davenports took the opposite view: they relied on overkill. Their act was designed as a public performance, where the people in the back stalls could see and hear everything that happened equally as well as those at the front—and see and hear it they did!

Bound hand and foot by ropes that were then sealed with sealing-wax, and subsequently shut inside their "spirit cabinet", the brothers would make a racket with an array of musical instruments that had been placed on the cabinet floor. The two cabinet doors would alternately burst open and slam shut, revealing one bound brother then the other, while instruments went flying through the air, often being hurled directly into the audience.

In England the Davenports initially found some support. Richard Burton, the translator of—for its time—the extremely racy Arabian Nights had this to say in their defence: "I have spent a great part of my life in Oriental lands, and have seen their many magicians. Lately I have been permitted to see and be present at the performances of Messrs. Anderson and Tolmaque. The latter showed, as they profess, clever conjuring, but they do not even attempt what the Messrs. Davenport and Fay succeed in doing…"

Unfortunately a number of amateur British magicians disagreed. Two of their ilk joined the tour in Liverpool in the February of 1865 and, upon "volunteering" from the audience, bound the brothers' hands so tight with knots that couldn't be undone that their wrists bled. The Davenport brothers were eventually cut free but refused to continue. The audience, unimpressed by what they'd witnessed, stormed the stage and smashed their cabinet to pieces. The perpetrators of the knot-tying struck again at their gig in Huddersfield—then later at Leeds—and each time they did, the violence escalated. Ira and William cancelled their remaining English dates and took their show to Europe.

But a twenty-five-year-old watchmaker named John Nevil Maskelyne, who had seen the brothers' act, had worked out how the trick was managed. He and his friend, George Alfred Cooke, built their own spirit cabinet and gave their own public demonstration—minus all spiritualist trappings—in June of 1865. Word of their performance was rapidly spread by the fascinated British press. Their success in unmasking the Davenports ignited their passion for stage magic, and the two went on to create many further illusions, some of which are still performed today.

As for the Davenports, the youngest brother, William, died in 1877 in Sydney, Australia, at the age of thirty-six. Ira moved back to America, where died in 1911. Before his death he wrote to Harry Houdini, famous escapologist and unmasker of psychics, claiming that he and William had never publicly stated their belief in spiritualism. But the truth is probably best represented by Ira's obituary in one American newspaper: "They made the mistake of appearing as sorcerers instead of as honest conjurers. If, like their conqueror, Maskelyne, they had thought of saying, 'It's so simple,' the brethren might have achieved not only fortune but respectability."

Next month: Mediumistic or mad?—the precarious position of women who dared to be spiritualists

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Carte-de-visite of John Nevil Maskelyne, illusionist and magician (1839-1917)

Photographer and date unknown

Henry Slade (1835-1905)

The Davenport brothers seated in their spirit cabinet, with their asscociates Mr Fay and Mr Cooper in the foreground

Photographer unknown; 1870

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit my website for details of a free download.

Published on March 01, 2014 06:20

•

Tags:

agnes-guppy, davenport-brothers, florence-cook, forbes-winslow, ghost-grabbers, henry-slade, houdini, katie-king, lankester, lord-colchester, mary-lincoln, maskelyne, mediums, noah-brooks, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, volckmann