Michael Gallagher's Blog - Posts Tagged "noah-brooks"

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: a séance in the White House

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the third in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the third in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.In the early 1860s, Washington, D.C. was not the place that we picture today. The Washington Canal, which flowed into the Potomac River a little to the south of the White House, was used as a cesspit and sewer, the stench of which permeated the presidential mansion every summer. One contemporary summed it up neatly: "The ghosts of twenty thousand drowned cats come in nights through the South Windows". Pestilence reigned, and not even the White House was exempt from its grip, as Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, discovered to their cost when their third son, Willie, contracted typhoid fever and died in the February of 1962.

By the start of June, as summer arrived, Mary Lincoln insisted that the family quit the city and relocate to their favourite retreat, a former plantation a few miles north of the capital that had been redeveloped by the banker George Riggs as an estate to house former military men: The Soldiers' Home. It was here that they stayed until mid-November, in the humbly-named but really rather grand Riggs Cottage. Although the cottage was light and airy, as the estate was set on a higher elevation than the neighbouring city, it was often far from peaceful. In addition to the braying of nearly two thousand mules stabled nearby, there was also the din of drums, rifles and band practice to contend with from Lincoln's hundred-strong presidential guard.

Despite the noise and the disruptions of war, the Lincolns entertained regularly. One particular guest that summer, at Mary's invitation, was a man calling himself Lord Colchester, a trance medium who claimed to be the illegitimate son of an English duke. In her desire for some form of contact from her beloved son, Willie, and her second-born, Eddie, who had died some years earlier, Mary was only too keen to avail herself of his services. And so she arranged for a séance to be held in the Riggs Cottage library.

As the participants seated themselves around the table, Colchester produced a number of musical instruments—a banjo, some bells and a drum—and laid them out on top. Everybody held hands and the lights were extinguished. At first nothing happened. Then came some loud raps, some scratching sounds, the twang of the banjo. Strands of hair were pulled; people's skin was pinched. Mary was delighted.

Lincoln was sufficiently concerned by this séance to ask Dr Joseph Henry, first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute, to investigate. Unable to determine exactly how Colchester managed to produce his phenomena, he turned to the journalist, Noah Brooks, for help. Brooks, who, after the death of his wife earlier that year, had been sent by the Sacramento Daily Union to cover the Lincoln administration, had been readily accepted into the Lincoln household as if he were a long-lost friend. And quite a friend he proved to be.

That evening in the dimly-lit library, with the medium's selection of musical instruments set out before them, the company once more joined hands and again the lights were extinguished. Suddenly the sound of a drum was heard, hovering high above their heads. This is Noah Brooks's own account of what happened next:

"Loosening my hands from my neighbors', who were unbelievers, I rose, and, grasping in the direction of the drumbeat, grabbed a very solid and fleshy hand in which was held a bell that was being thumped on a drum-head. I shouted, 'Strike a light!' My friend, after what appeared to be an unconscionable length of time, lighted a match; but meanwhile somebody had dealt me a severe blow with the drum, the edge of which cut a slight wound on my forehead. When the gas was finally lighted, the singular spectacle was presented of 'the son of the duke' firmly grasped by a man whose forehead was covered with blood, while the arrested scion of nobility was glowering at the drum and bells which he still held in his hands."

Undeterred by the events at the Soldiers' Home, on her return to the White House in November Mary sought solace at the two-storey Georgetown home of a Mr and Mrs Cranston Laurie and their daughter Belle, at what was then 21 First Street (3226 N Street today). Mr Laurie was chief clerk of the Post Office Service and many of his spiritualist acquaintances held equally high government posts; Mrs Laurie and her daughter were both trance mediums of some renown. On New Year's Day 1863, Mary Lincoln revealed to a friend that she had attended a number of séances there, and that Mrs Laurie had made wonderful revelations to her about her dead son, Willie, and had received communications that her husband's cabinet was full of enemies plotting against him for their own ends.

However, according to Nettie Colburn Maynard in her memoir "Was Abraham Lincoln a Spiritualist?", published many years later in 1891, it was Nettie herself who acted as medium, and not Mrs Laurie or Belle, on the evening of February 5th 1863 when President Lincoln accompanied his wife to one of the Lauries' popular séances. When Lincoln asked the spirit she had channelled about the current situation regarding the war, she writes that he received the following reply:

'…That a very precarious state of things existed at the front, where General Hooker had just taken command. The army was totally demoralized; regiments stacking arms, refusing to obey orders or to do duty; threatening a general retreat; declaring their purpose to return to Washington. A vivid picture was drawn of the terrible state of affairs, greatly to the surprise of all present, save the chief to whom the words were addressed. When the picture had been painted in vivid colors, Mr. Lincoln quietly remarked: "You seem to understand the situation. Can you point out the remedy?"'

The remedy suggested was that he go to the front in person, taking with him his wife and children, and, avoiding the high-grade officers, seek out the tents of private soldiers and enquire into their grievances. In other words, that he should show himself to be "the Father of the People".

Although Nettie Colburn Maynard may have been embroidering the truth somewhat (many if not most of her claims are rather doubtful, and there are reports—though these too are dubious—that it was the Lauries' daughter Belle who acted as medium on that night), in the simple matter of the president's attendance at this séance, I think this at least is true, for something certainly triggered the extraordinary event that came next. Barely seven weeks later, on the 23rd of April, 1863, President Lincoln—a lifelong skeptic—organised his own séance…in the White House.

The evening was attended by his wife, a reporter from the Boston Gazette, two of his Cabinet Secretaries, Stanton and Welles. His medium of choice was a man named Charles E. Shockle. The séance began with a few loud raps and a false start or two, but eventually Shockle came through with a message from Henry Knox, George Washington's Secretary of War: "Haste makes waste, but delays cause vexations". When Lincoln asked when the revolt would be put down, Knox replied that a lively discussion held between Washington, Franklin and Napoleon had produced a variety of answers, which he then went on to summarise for the president. This is reportedly Lincoln's rather wry response:

"Well, opinions differ among the saints as well as among the sinners. They don't seem to understand running the machines among the celestials much better than we do. Their talk and advice sound very much like the talk of my cabinet."

It was a tongue-in-cheek skeptic's comment. Quite why Lincoln held his séance is anyone's guess, but the inclusion of a reporter from the Boston Gazette among the party—and not his trusted friend Noah Brooks—suggests that he may have contrived it as a publicity stunt, and one in which he was unwilling to involve his friend. And yet the article that subsequently appeared in the Gazette was reprinted in Brooks's Sacramento Daily Union some two months later.

Mary Todd Lincoln was to remain in the thrall of spiritualism for the rest of her life, and we will be revisiting her occasionally, as she still has a part to play in its story.

Next month: The Civil War—how the war itself and an emerging technology both contributed to the rise of spiritualism

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Image:

Mary Todd Lincoln (1818-1882)

Photograph by Mathew Brady (1822-1896), 1861

Published on September 01, 2013 05:34

•

Tags:

lincoln, mary-todd-lincoln, mediums, noah-brooks, seances, soldiers-home, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, white-house

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the ninth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.So far in this history we've already encountered a number of ghost-grabbers: Noah Brooks, the American journalist with the Sacramento Daily Union, who literally grabbed the trance medium Lord Colchester's hand at a séance instigated by Mary Todd Lincoln, and the English lawyer, William Volckmann, who seized the spirit of Katie King by the waist and refused to let go—despite being tackled by two of Florence Cook's confederates who were stationed in the audience, one of whom she ended up marrying a mere four months later. Both instances were brutal and bloody. Brooks received a blow to his forehead with a drum that Colchester used in his performance; Volckmann, who was in league with the medium Agnes Guppy—one of Florence's rivals—had part of his beard torn away. Florence was ghost-grabbed again some years later, you may recall, this time by the twenty-year-old Sir George Sitwell at the assembly rooms of the National British Association of Spiritualists in 1880. It spelled the end of her career. She was forced to retire and move to Wales.

Another victim to be caught out several times was the medium Henry Slade (1835-1905), who was noted for his chalked spirit messages that would "miraculously" appear on a conveniently-held slate. Having been twice unmasked as a fraud in America (first by John W. Truesdell in 1872, then by Stanley LeFevre Krebs), he came to Britain to ply his trade. Here he was thwarted by Ray Lankester (1847-1929), a twenty-nine-year-old professor of zoology at University College London, who in 1876 snatched the pre-inscribed slate from the medium's grasp. Slade was brought to trial and found guilty of fraud, but successfully appealed his conviction on a technicality, that the original charge had omitted the words "by palmistry or otherwise". Before fresh charges could be brought he'd fled the country and returned to America.

Ghost-grabber Lankester was one of a growing group of scientific men, as was William Benjamin Carpenter (1813-1885), a colleague of his who had recently been appointed Registrar of the University of London, and Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow (1844-1913), an alienist (an early form of psychologist), all of whom were beginning to challenge the most basic precepts of spiritualism, possibly as a reaction to William Crookes's reviled report, Notes of an Enquiry into the Phenomena called Spiritual, published some two years before Slade's trial. Winslow (or Forbes-Winslow, as he eventually came to style himself) used red ink in pursuit of charlatans. He would squirt it in the faces of any spirits that happened to materialize in his presence. He's a fascinating character who I will return to in the next post.

But it wasn't just scientists who worked to unmask frauds. It was often stage magicians who proved far more ruthless as opponents. Even by the mid-1860s a professional hatred had emerged that separated stage magicians, who claimed no spiritual intervention for their illusions, from spiritualist mediums, who did. Such was the case with the two Davenport brothers, Ira and William, who like Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home before them, came to Britain from America either at the end of 1864 or the beginning of 1865.

Ira Davenport was born in the September of 1839; his brother William was born less than two years later in 1841. They were the sons of a policeman and grew up in Buffalo, New York. They claimed to have discovered their mediumistic powers when Fox-style rappings broke out at their house in 1846, two years before those of the Fox sisters, when Ira was seven years old and William barely five. By 1854, when both boys were still teenagers, they had already come up with the basic building blocks of their act. Managed by their father, tutored by a local amateur conjurer, William Fay, and introduced on stage by Dr J. B. Ferguson, a former minister of religion who truly believed in the brothers' spiritualistic abilities, they started giving shows across America, from which they earned their living for the next ten years.

While the séances of Maria B. Hayden and Daniel Dunglas Home may have relied rather heavily on creating a specific eerie atmosphere where people's heightened senses would cause them to jump out of their skin at the slightest unexpected sound, the Davenports took the opposite view: they relied on overkill. Their act was designed as a public performance, where the people in the back stalls could see and hear everything that happened equally as well as those at the front—and see and hear it they did!

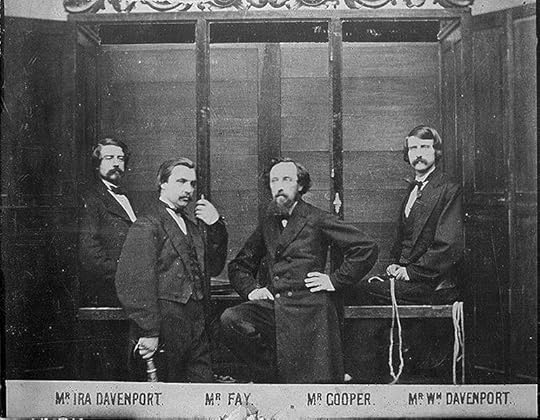

Bound hand and foot by ropes that were then sealed with sealing-wax, and subsequently shut inside their "spirit cabinet", the brothers would make a racket with an array of musical instruments that had been placed on the cabinet floor. The two cabinet doors would alternately burst open and slam shut, revealing one bound brother then the other, while instruments went flying through the air, often being hurled directly into the audience.

In England the Davenports initially found some support. Richard Burton, the translator of—for its time—the extremely racy Arabian Nights had this to say in their defence: "I have spent a great part of my life in Oriental lands, and have seen their many magicians. Lately I have been permitted to see and be present at the performances of Messrs. Anderson and Tolmaque. The latter showed, as they profess, clever conjuring, but they do not even attempt what the Messrs. Davenport and Fay succeed in doing…"

Unfortunately a number of amateur British magicians disagreed. Two of their ilk joined the tour in Liverpool in the February of 1865 and, upon "volunteering" from the audience, bound the brothers' hands so tight with knots that couldn't be undone that their wrists bled. The Davenport brothers were eventually cut free but refused to continue. The audience, unimpressed by what they'd witnessed, stormed the stage and smashed their cabinet to pieces. The perpetrators of the knot-tying struck again at their gig in Huddersfield—then later at Leeds—and each time they did, the violence escalated. Ira and William cancelled their remaining English dates and took their show to Europe.

But a twenty-five-year-old watchmaker named John Nevil Maskelyne, who had seen the brothers' act, had worked out how the trick was managed. He and his friend, George Alfred Cooke, built their own spirit cabinet and gave their own public demonstration—minus all spiritualist trappings—in June of 1865. Word of their performance was rapidly spread by the fascinated British press. Their success in unmasking the Davenports ignited their passion for stage magic, and the two went on to create many further illusions, some of which are still performed today.

As for the Davenports, the youngest brother, William, died in 1877 in Sydney, Australia, at the age of thirty-six. Ira moved back to America, where died in 1911. Before his death he wrote to Harry Houdini, famous escapologist and unmasker of psychics, claiming that he and William had never publicly stated their belief in spiritualism. But the truth is probably best represented by Ira's obituary in one American newspaper: "They made the mistake of appearing as sorcerers instead of as honest conjurers. If, like their conqueror, Maskelyne, they had thought of saying, 'It's so simple,' the brethren might have achieved not only fortune but respectability."

Next month: Mediumistic or mad?—the precarious position of women who dared to be spiritualists

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Carte-de-visite of John Nevil Maskelyne, illusionist and magician (1839-1917)

Photographer and date unknown

Henry Slade (1835-1905)

The Davenport brothers seated in their spirit cabinet, with their asscociates Mr Fay and Mr Cooper in the foreground

Photographer unknown; 1870

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. Visit my website for details of a free download.

Published on March 01, 2014 06:20

•

Tags:

agnes-guppy, davenport-brothers, florence-cook, forbes-winslow, ghost-grabbers, henry-slade, houdini, katie-king, lankester, lord-colchester, mary-lincoln, maskelyne, mediums, noah-brooks, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, volckmann