Michael Gallagher's Blog - Posts Tagged "mediums"

The rise and fall of Victorian medium Florence Cook: what Katie brought to the table

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the first of four posts relating her life story.

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the first of four posts relating her life story.Florence Eliza Cook was born on June 3rd 1856 in Cobham, Kent to parents Henry and Emma Cook, who moved to London when she was three and took up residence at 6 Bruce Villas, Eleanor Road, Dalston. She was the eldest of four children.

In 1870, at the age of fourteen, she began table-rapping experiments with her friends and family, surprising everyone when a violent burst of poltergeist activity ensued. A spirit responding to her questions through a system of yes-or-no raps informed her that she was indeed a medium and then directed her to the local Spiritualist Association. By the following year she’d started working for a pair of established mediums, Frank Herne and Charles Williams, and reports of her séances were beginning to crop up in the spiritualist press. Herne’s spirit-guide was an entity named John King, who rather confusingly claimed to be the ghost of Sir Henry Morgan, the famous buccaneering pirate. Florence Cook’s guide was Katie King, John’s daughter, who also claimed to be Annie Owens Morgan, the daughter of the pirate. At this point there was none of the bodily manifestations of Katie that came later; there were simply disembodied voices, messages written by unseen hands, and phenomena known as “apports”—objects that appeared to fall from the ceiling.

There is a truly fascinating story of one such occurrence: early in the June of 1871 Herne and Williams were conducting a séance together for eight sitters around a table at 69 Lamb’s Conduit Street when the voices of Katie King and her father were heard in the darkness. Katie offered to produce a gift for the group and one of the sitters suggested—half jokingly—that she bring them Agnes Guppy, an extremely stout medium famed for her own apports who lived some miles away in Highbury. Katie laughed—everybody laughed—and though her father protested she agreed to go through with it. Suddenly there was a loud thump; somebody screamed. When one of the company had the presence of mind to light a lamp, there on the table in front of them, apparently in some kind of trance, was perched the stout Mrs Guppy in a state of semi-undress, account book and pen still in hand. Now that’s what I call entertainment!

Next time: Katie finally makes an appearance but nearly falls victim to a ghost-grabber.

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Published on April 29, 2013 06:19

•

Tags:

florence-cook, katie-king, mediums, seances, spiritualism, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

The rise and fall of Victorian medium Florence Cook: Katie’s brush with a ghost-grabber

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the second of four posts relating her life story.

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the second of four posts relating her life story.By the beginning of 1873 Florence was performing her own séances at the Cook family home in Dalston, but by now there were full materialisations. The audience, often comprised of highly respectable professional men and women, would sit in the dimly-lit parlour while Florence was bound by ropes. She then retired to an adjoining room screened off from view by a thin damask curtain. Presently the spirit of Katie King would appear dressed in white, and walk about the room telling the story of her former life as Annie Morgan, the buccaneer’s daughter. It was a charming tale. Annie had been twelve years old when Charles the First was beheaded; she’d married and had two little children; she’d committed more crimes than she cared to confess; she’d even murdered men with her own two hands; she’d died young. To questions concerning the reason of her reappearance back on earth, she claimed that it was part of the work she’d been entrusted with, to convince the world of the truth of Spiritualism.

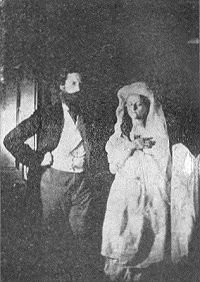

In Spring of that year Florence Cook held a series of sittings designed to capture a photographic likeness of Katie. On the 7th of May, Mr W. H. Harrison, a reporter for the Daily Telegraph (who in later years went on to edit The Spiritualist, a London-based magazine dedicated to examining spiritualist phenomena from a scientific perspective), successfully managed to take the first four photographs of Katie. Florence also sat for the highly respected scientist William Crookes, who took a total of forty-four photos of Katie at his home in Regent’s Park, all the while performing tests on Florence as part of his on-going investigation into spiritualist mediums.

Florence was fast becoming famous, but fame breeds jealousy. At a séance held on the 9th of December 1873 the lawyer William Volckmann seized Katie King by the waist and refused to let go. Some of those present claimed that the spirit “glided” out of Volckmann’s grip; others suggest that she defended herself quite vigorously (Volckmann lost part of his beard). Edward Elgie Corner, a ship’s captain from Dalston who was a neighbour of the Cooks as well as being a close family friend, together with another of her supporters rushed to Katie’s aid. The gaslights were rapidly extinguished, there was a great deal of scuffling and by the time peace was eventually restored and the room re-lit, Katie King had vanished and Florence Cook was discovered still secured by her ropes. As Volckmann was most likely in league with Agnes Guppy (the formidable medium from Highbury who’d landed on the table in a state of semi-undress—whom he in fact married after her elderly husband passed away barely a year later), it would seem that Florence’s relationship with her erstwhile colleague had soured considerably.

Volckmann’s attack damaged her reputation. Unfortunately Crookes’s report, Notes of an Enquiry into the Phenomena called Spiritual during the Years 1870-1873, published a month later in the Quarterly Journal of Science (January 1874) did little to restore it, despite his vehement assertion that Florence Cook, the American Kate Fox, and the Scotsman Daniel Dunglas Home, were all genuine mediums producing perfectly genuine results.

Next time: Katie King bids the world farewell (for the second time, presumably).

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Published on May 07, 2013 04:23

•

Tags:

mediums, seance, spiritualism, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

The rise and fall of Victorian medium Florence Cook: Katie’s final farewell

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the third of four posts relating her life story.

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the third of four posts relating her life story.The séances continued. Florence teamed up with another girl, Mary Rosina Showers. The pair gave a séance at the Crookes home in March of 1874 which was attended by a number of witnesses, among them the barrister, Sergeant-at-law Edward William Cox. Cox was a firm believer in spiritualism; it was he who had first hosted and championed the Scottish-born medium Daniel Dunglas Home on his return from America. He published his observations some weeks later in The Spiritualist, the leading newspaper in its field. Of the materialisations he wrote: “They were solid flesh and blood and bone. They breathed, and perspired, and ate…Not merely did they resemble their respective mediums, they were…alike in face, hair, complexion, teeth, eyes, hands, and movements of the body…”

As regards proof that they were not simply the two girls themselves, he wrote: “…no proof whatever was given or offered or permitted. The fact might have been established in a moment beyond all doubt by the simple process of opening the curtain and exhibiting the two ladies then and there upon the sofa, wearing their black gowns. But this only certain evidence was not proffered, nor, indeed, was it allowed us…”

On the 29th of April 1874 Florence Cook married Captain Edward Elgie Corner, the neighbour who had rushed to Katie’s aid the previous December. Though their marriage was blessed with two daughters, Kate and Edith, it was not a happy one.

The final appearance of Katie King was a truly sad occasion. She had often stated that she could not appear on this earth beyond the month of May, 1874, and so, on the 21st, she assembled her friends together to bid them all goodbye. This eye-witness account was written by the stage actress and internationally successful author Florence Marryat:

“Katie had asked Miss Cook to provide her with a large basket of flowers and ribbons, and she sat on the floor and made up a bouquet for each of her friends to keep in remembrance of her. Mine, which consists of lilies of the valley and pink geranium, looks almost as fresh to-day, nearly seventeen years after, as it did when she gave it to me. It was accompanied by the following words, which Katie wrote on a sheet of paper in my presence: ‘From Annie Owen de Morgan (alias “Katie”) to her friend Florence Marryat Ross-Church. With love. Pensez à Moi. May 21st 1874.’ The farewell scene was as pathetic as if we had been parting with a dear companion by death. Katie herself did not seem to know how to go. She returned again and again to have a last look, especially at Mr. Alfred [William] Crookes, who was as attached to her as she was to him.”

Of that final parting, this is what William Crookes himself wrote: “Having concluded her directions, Katie invited me into the cabinet with her, and allowed me to remain there to the end. After closing the curtain she conversed with me for some time, and then walked across the room to where Miss Cook was lying senseless on the floor. Stooping over her, Katie touched her and said, ‘Wake up, Florrie, wake up! I must leave you now.’ Miss Cook then woke and tearfully entreated Katie to stay a little time longer. ‘My dear, I can’t; my work is done. God bless you!’…For several minutes the two were conversing with each other, till at last Miss Cook’s tears prevented her speaking. Following Katie’s instructions, I then came forward to support Miss Cook, who was falling on to the floor, sobbing hysterically. I looked around, but the white-robed Katie had gone…”

It would be impossible not to compare Cox’s statement with that of Crookes’s, or Florence’s likeness with that of Katie’s. But I will tell you this: I am absolutely convinced that William Crookes was not lying about what he saw.

Next time: how Florence copes without Katie.

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Published on May 24, 2013 06:25

•

Tags:

mediums, seance, spiritualism, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

The rise and fall of Victorian medium Florence Cook: life after Katie

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the fourth and final post relating her story.

Although

The Bridge of Dead Things

is clearly a work of fiction, it was suggested in part by the true tale of the respected Victorian scientist Sir William Crookes and his spirit-materialising protégée Florence Cook. This is the fourth and final post relating her story.Though Katie was never to appear again, Florence went on to host two further spirit-guides during her lifetime: firstly Leila in 1875 (the same year that Frank Herne, the medium who’d set Florence on her career-path was debunked as a fraud), and then later a French girl who called herself Marie, who was said to have “danced and sung in a truly professional style”.

In 1880 Florence Cook was ghost-grabbed for a second time, on this occasion by the young Sir George Sitwell, a 20-year-old Oxford University student, at a public séance being given at the rooms of the National British Association of Spiritualists. The debacle ruined her, and she retired and moved to Wales. The incident brought Sir George some noteriety too and he soon left Oxford without taking a degree. He ended up fathering a daughter, the future Dame Edith Sitwell, truly England’s most eccentric poet who became something of an entertainer herself. In 1923 she alienated her audience by standing out of sight behind a starkly-painted screen while shouting her poems at them through a megaphone, all in time to William Walton’s carefully arranged score of Façade – An Entertainment.

In 1899 Florence tried to revive her career when she was invited to Berlin to undertake a series of séances under test conditions by the Sphinx Society. She died of pneumonia in relative poverty at 20 Battersea Rise, London, on the 22nd of April 1904 at the age of 48. Her husband outlived her by a quarter of a century and died in 1928.

William Crookes received his knighthood in 1897 and the Order of Merit in 1910. He died in 1919. Towards the end of his life he sought out mediums to help him communicate with his beloved wife, who had predeceased him by two years.

I’d like the last words to go to the fifteen-year-old Florence Cook herself. In a letter to Mr W. H. Harrison (the Telegraph reporter who would later take the first photographs of Katie), dated May, 1872, she writes: “From my childhood I could see spirits and hear voices, and was addicted to sitting by myself talking to what I declared to be living people. As no one else could see or hear anything, my parents tried to make me believe it was all imagination, but I would not alter my belief…”

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Published on June 08, 2013 06:17

•

Tags:

mediums, seance, spiritualism, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: an early April Fool?

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the first in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the first in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.The story of spiritualism starts with a house that had an uncanny reputation in Hydesville, New York, a hamlet which no longer exists but was then situated in Wayne County in New York State. John Fox, a farmer, took over the tenancy with his wife Margaret and two of his children, Margaret and Kate on December 11th, 1847. Three months of relative peace went by, then at the tail end of March, when his daughters were aged fourteen and eleven respectively, the knocking began. Noises were heard all through the house. John and his wife investigated, but could find no explanation for the sounds.

On Friday the 31st of March the family retired early for the night, with the girls sleeping in the same room as their parents, when the commotion began again. Kate, the youngest challenged the noise-maker, saying, "Mr. Splitfoot, do as I do," whilst clapping her hands. The sound instantly followed her with the same number of raps.

According to Mrs Fox’s own testimony, “…[Kate] said in her childish simplicity, "Oh, mother, I know what it is. To-morrow is April-fool day, and it's somebody trying to fool us." I then thought I could put a test that no one in the place could answer. I asked the noise to rap my different children's ages, successively. Instantly, each one of my children's ages was given correctly, pausing between them sufficiently long to individualize them until the seventh, at which a longer pause was made, and then three more emphatic raps were given, corresponding to the age of the little one that died, which was my youngest child. I then asked: "Is this a human being that answers my questions so correctly?" There was no rap. I asked: "Is it a spirit? If it is, make two raps." Two sounds were given as soon as the request was made. I then said "If it was an injured spirit, make two raps," which were instantly made, causing the house to tremble. I asked: "Were you injured in this house?" The answer was given as before. "Is the person living that injured you?" Answered by raps in the same manner. I ascertained by the same method that it was a man, aged thirty-one years, that he had been murdered in this house, and his remains were buried in the cellar; that his family consisted of a wife and five children, two sons and three daughters, all living at the time of his death, but that his wife had since died. I asked: "Will you continue to rap if I call my neighbours that they may hear it too?" The raps were loud in the affirmative.”

Mr Fox called in a neighbour, a no-nonsense woman named Mrs Redfield. After the spirit had answered her questions she called for her husband, who then called in all the other neighbours, one of whom, Mr Duesler, managed to ascertain that the man was murdered in the east bedroom about five years ago; that the murder was committed on a Tuesday night at twelve o'clock; that he was murdered by having his throat cut with a butcher knife; that he was murdered for money; that the body was taken down to the cellar; that it was not buried until the next night; that it was taken through the buttery, down the stairway, and that it was now buried ten feet below the surface of the ground.

By the next day (April 1st) the house was full to overflowing with people curious to experience the now celebrated phenomena for themselves. In the evening they dug up the cellar until they came to water, and then they gave up. The knocking continued intermittently over the next few days. Within a week Mrs Fox’s hair had turned white from the anxiety.

Fourteen-year-old Margaret was sent to stay with her older brother David in the nearby town of Rochester; Kate also went to Rochester to stay with her older sister Leah, a music teacher whose married name was Fish. Unfortunately the rapping knocks went too. Hundreds flocked to Mrs Fish’s house to witness and marvel.

The knocking became contagious. It was no longer confined to the Fox family. Similar sounds were heard in the homes of the Reverend A. H. Jervis, a Methodist minister from Rochester, and a Mrs Sarah A. Tamlin, a Mrs Benedict, and a certain Deacon Hale, who lived in surrounding towns. Now the knocks claimed that they came from the deceased friends of those who were gathered there. The amateur séance was born.

These early enthusiasts were often reformers who championed the abolition of slavery, equal rights for women, and the temperance movement. Their involvement with spiritualism reflects a link between spiritualists and radical reformers, especially those who advocated women's rights, that would last for more than half a century.

At this point séances were essentially domestic affairs held in private homes. Soon, however, they would become much, much more.

Next month: there’s no business like show business

Find out more at

michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

The Fox sisters; Kate and Margaret Fox with their married sister, Mrs Leah Fish

Photographer and date unknown

The Foxes’ House, Hydesville, New York

Photographer and date unknown

Published on June 30, 2013 06:30

•

Tags:

fox-sisters, kate-fox, margaret-fox, mediums, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: there’s no business like show business

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the second in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the second in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.Although spiritualism and séances were always to retain a strong domestic, amateur appeal, in that they remained essentially private affairs practised by middle-class enthusiasts dabbling in table-rapping and table-turning in their own homes, they were destined to became public, professional affairs as well.

The small band of pioneers from Rochester (dubbed by many as "the Rochester rappers") received spirit messages urging them to hold an open meeting where their powers could be investigated and tested. This was a risky move, for although the spirits obliged with their normal fare of raps and knocks, the men who were testing the mediums refused to believe that they were caused by any outside agency.

Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New York Tribune, published their report, but also appended a note suggesting that their tests were invalid because of the men’s obvious bias. Supporters rallied to the call, giving testimony about the Fox sisters’ abilities. Rather than stifling spiritualism, the report fed the public interest in the girls.

Under the watchful supervision of their mother, the three Fox sisters began giving public sittings at Barnum's Hotel in New York in the spring of 1850. There’s a contemporary description written by a Mrs Emma Hardinge, who was later to become a medium in her own right, which gives us some idea of the pressure the girls faced. She talks of "pausing on the first floor to hear poor patient Kate Fox, in the midst of a captious, grumbling crowd of investigators, repeating hour after hour the letters of the alphabet, while the no less poor, patient spirits rapped out names, ages and dates to suit all comers." Although most of the press reports denounced them as frauds, Horace Greeley published a supportive and sympathetic article in his paper. After a tour of the Western States, the Fox family paid a second visit to New York, which again attracted an intense public interest, both positive and negative.

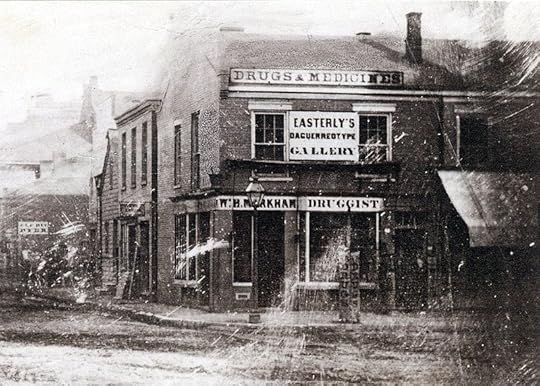

For some years the two younger sisters, Kate and Margaret, made their living by giving séances. An extraordinary daguerreotype of Kate and Margaret exists in the Missouri History Museum, made by the daguerreotypist Thomas M. Easterly at his studio in St. Louis, Missouri when the sisters stopped off there during their national tour of 1852. Do take the opportunity to click on this link and have a look. A daguerreotype is a photographic likeness made directly onto a sheet of polished silver-plated copper; no intermediary negative is used and no prints can be made, and consequently each daguerreotype is a one-off original. I wanted to use this image to head up this post, but although the copyright on the original expired long ago, the copyright on the reproduction that you see did not.

One of the early communications that the Fox sisters received had claimed that "these manifestations would not be confined to them, but would go all over the world." Their public demonstrations were proving to be so popular that now others began to copy and improve upon their format. In an incredibly short space of time the movement swept across the Northern and Eastern States of the Union, with mediums (or "trance lecturers" as they were known) competing to produce increasingly startling phenomena. A repertoire that had started as a simple series of loud raps and knocks now included the appearance of "spirit-lights" and disembodied hands and faces, automatic writing whilst the medium was apparently in a trance, channelled spirits who spoke to or through the medium, objects that moved by themselves, and even levitation. Spiritualism had become show business.

Prominent practitioners at this point included a certain Mrs Hayden, the two Davenport brothers, and Daniel Dunglas Home (all four of whom I will discuss in greater detail in a later post), the beautiful young Cora L. V. Hatch, Achsa W. Sprague, an abolitionist and advocate of equal rights for women, and Paschal Beverly Randolph, an intriguing man of mixed race who was one of the earliest abolitionists.

Paschal Beverly Randolph was one of this new breed of mediums to rise to prominence in the early 1850s. He was eloquent and good-looking, with a commanding stage presence and a compelling personality to match. From a young age he’d been obliged to make his living as an irregular crewman aboard a number of commercial vessels. His travels had taken him to England and France, and as far east as Persia, and had introduced him to a wealth of new ideas, religions and esoteric beliefs. It was during this time that he developed an deep and abiding interest for gnosticism, freemasonry, sexual magic and the occult.

On his return to America he started writing books (he wrote over fifty of them during his lifetime), many of which were vehicles for his masonic beliefs. Two of these have been lovingly recreated as e-books and are available as free downloads from the wonderful Gutenberg Project (though I warn you now, they are both written in the heavily veiled allegorical style that is typical of most masonic texts). As well as writing, Randolph set up his own publishing house and trained as a doctor. He also established the first Rosicrucian organisation in America, the Fraternitas Rosae Crucis (the Fraternity of the Rosy Cross). All through this period he worked as a trance lecturer, using his stage appearances to argue the case for the abolition of slavery.

As admirable as as all this may be (though it does go some way to demonstrate the strong bond between spiritualism and radical reform), the real reason for his inclusion here is that he provides an interesting link to next month’s post. It is claimed that in 1851, at the age of 25, Paschal Beverly Randolph made the acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln and struck up a friendship that lasted until Lincoln’s untimely death. Despite the fact that Lincoln’s second son, Eddie, had died the previous year from tuberculosis, it’s far more likely that the medium offered the great man his views on abolition, and not some form of spiritualist communion with his dead child. But, as we will see next time, Randolph was not the only medium to make Lincoln’s acquaintance.

Next month: a séance in the White House

Find out more at

michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825-1875)

Thomas M. Easterly’s Daguerreotype Gallery, St. Louis

Photographer unidentified, but presumably Thomas M. Easterly himself (1809-1882), 1851

Published on August 01, 2013 04:04

•

Tags:

fox-sisters, horace-greeley, kate-fox, margaret-fox, mediums, new-york-times, paschal-beverly-randolph, rochester, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: a séance in the White House

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the third in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the third in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.In the early 1860s, Washington, D.C. was not the place that we picture today. The Washington Canal, which flowed into the Potomac River a little to the south of the White House, was used as a cesspit and sewer, the stench of which permeated the presidential mansion every summer. One contemporary summed it up neatly: "The ghosts of twenty thousand drowned cats come in nights through the South Windows". Pestilence reigned, and not even the White House was exempt from its grip, as Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, discovered to their cost when their third son, Willie, contracted typhoid fever and died in the February of 1962.

By the start of June, as summer arrived, Mary Lincoln insisted that the family quit the city and relocate to their favourite retreat, a former plantation a few miles north of the capital that had been redeveloped by the banker George Riggs as an estate to house former military men: The Soldiers' Home. It was here that they stayed until mid-November, in the humbly-named but really rather grand Riggs Cottage. Although the cottage was light and airy, as the estate was set on a higher elevation than the neighbouring city, it was often far from peaceful. In addition to the braying of nearly two thousand mules stabled nearby, there was also the din of drums, rifles and band practice to contend with from Lincoln's hundred-strong presidential guard.

Despite the noise and the disruptions of war, the Lincolns entertained regularly. One particular guest that summer, at Mary's invitation, was a man calling himself Lord Colchester, a trance medium who claimed to be the illegitimate son of an English duke. In her desire for some form of contact from her beloved son, Willie, and her second-born, Eddie, who had died some years earlier, Mary was only too keen to avail herself of his services. And so she arranged for a séance to be held in the Riggs Cottage library.

As the participants seated themselves around the table, Colchester produced a number of musical instruments—a banjo, some bells and a drum—and laid them out on top. Everybody held hands and the lights were extinguished. At first nothing happened. Then came some loud raps, some scratching sounds, the twang of the banjo. Strands of hair were pulled; people's skin was pinched. Mary was delighted.

Lincoln was sufficiently concerned by this séance to ask Dr Joseph Henry, first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute, to investigate. Unable to determine exactly how Colchester managed to produce his phenomena, he turned to the journalist, Noah Brooks, for help. Brooks, who, after the death of his wife earlier that year, had been sent by the Sacramento Daily Union to cover the Lincoln administration, had been readily accepted into the Lincoln household as if he were a long-lost friend. And quite a friend he proved to be.

That evening in the dimly-lit library, with the medium's selection of musical instruments set out before them, the company once more joined hands and again the lights were extinguished. Suddenly the sound of a drum was heard, hovering high above their heads. This is Noah Brooks's own account of what happened next:

"Loosening my hands from my neighbors', who were unbelievers, I rose, and, grasping in the direction of the drumbeat, grabbed a very solid and fleshy hand in which was held a bell that was being thumped on a drum-head. I shouted, 'Strike a light!' My friend, after what appeared to be an unconscionable length of time, lighted a match; but meanwhile somebody had dealt me a severe blow with the drum, the edge of which cut a slight wound on my forehead. When the gas was finally lighted, the singular spectacle was presented of 'the son of the duke' firmly grasped by a man whose forehead was covered with blood, while the arrested scion of nobility was glowering at the drum and bells which he still held in his hands."

Undeterred by the events at the Soldiers' Home, on her return to the White House in November Mary sought solace at the two-storey Georgetown home of a Mr and Mrs Cranston Laurie and their daughter Belle, at what was then 21 First Street (3226 N Street today). Mr Laurie was chief clerk of the Post Office Service and many of his spiritualist acquaintances held equally high government posts; Mrs Laurie and her daughter were both trance mediums of some renown. On New Year's Day 1863, Mary Lincoln revealed to a friend that she had attended a number of séances there, and that Mrs Laurie had made wonderful revelations to her about her dead son, Willie, and had received communications that her husband's cabinet was full of enemies plotting against him for their own ends.

However, according to Nettie Colburn Maynard in her memoir "Was Abraham Lincoln a Spiritualist?", published many years later in 1891, it was Nettie herself who acted as medium, and not Mrs Laurie or Belle, on the evening of February 5th 1863 when President Lincoln accompanied his wife to one of the Lauries' popular séances. When Lincoln asked the spirit she had channelled about the current situation regarding the war, she writes that he received the following reply:

'…That a very precarious state of things existed at the front, where General Hooker had just taken command. The army was totally demoralized; regiments stacking arms, refusing to obey orders or to do duty; threatening a general retreat; declaring their purpose to return to Washington. A vivid picture was drawn of the terrible state of affairs, greatly to the surprise of all present, save the chief to whom the words were addressed. When the picture had been painted in vivid colors, Mr. Lincoln quietly remarked: "You seem to understand the situation. Can you point out the remedy?"'

The remedy suggested was that he go to the front in person, taking with him his wife and children, and, avoiding the high-grade officers, seek out the tents of private soldiers and enquire into their grievances. In other words, that he should show himself to be "the Father of the People".

Although Nettie Colburn Maynard may have been embroidering the truth somewhat (many if not most of her claims are rather doubtful, and there are reports—though these too are dubious—that it was the Lauries' daughter Belle who acted as medium on that night), in the simple matter of the president's attendance at this séance, I think this at least is true, for something certainly triggered the extraordinary event that came next. Barely seven weeks later, on the 23rd of April, 1863, President Lincoln—a lifelong skeptic—organised his own séance…in the White House.

The evening was attended by his wife, a reporter from the Boston Gazette, two of his Cabinet Secretaries, Stanton and Welles. His medium of choice was a man named Charles E. Shockle. The séance began with a few loud raps and a false start or two, but eventually Shockle came through with a message from Henry Knox, George Washington's Secretary of War: "Haste makes waste, but delays cause vexations". When Lincoln asked when the revolt would be put down, Knox replied that a lively discussion held between Washington, Franklin and Napoleon had produced a variety of answers, which he then went on to summarise for the president. This is reportedly Lincoln's rather wry response:

"Well, opinions differ among the saints as well as among the sinners. They don't seem to understand running the machines among the celestials much better than we do. Their talk and advice sound very much like the talk of my cabinet."

It was a tongue-in-cheek skeptic's comment. Quite why Lincoln held his séance is anyone's guess, but the inclusion of a reporter from the Boston Gazette among the party—and not his trusted friend Noah Brooks—suggests that he may have contrived it as a publicity stunt, and one in which he was unwilling to involve his friend. And yet the article that subsequently appeared in the Gazette was reprinted in Brooks's Sacramento Daily Union some two months later.

Mary Todd Lincoln was to remain in the thrall of spiritualism for the rest of her life, and we will be revisiting her occasionally, as she still has a part to play in its story.

Next month: The Civil War—how the war itself and an emerging technology both contributed to the rise of spiritualism

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Image:

Mary Todd Lincoln (1818-1882)

Photograph by Mathew Brady (1822-1896), 1861

Published on September 01, 2013 05:34

•

Tags:

lincoln, mary-todd-lincoln, mediums, noah-brooks, seances, soldiers-home, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances, white-house

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: exports to Britain

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fifth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the fifth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.It wasn't long before the rapping-type séances popularised by the Fox sisters in the late 1840s spread abroad—here to Britain. The first emissary to arrive at these shores was Mrs Maria B. Hayden (1826-1883). Born in Nova Scotia, she married one William R. Hayden in a ceremony in Boston in 1850. She was his second wife. Maria's mediumship began in the March or April of 1851, at the age of 25, after a séance held by the Haydens at their Hartford home in Connecticut, New England. The medium they invited to preside over the occasion was an 18-year-old youth, Daniel Home (pronounced "Hume", of whom we will learn more next month). If not his first séance, it was at least one of his very earliest. According to Home in his memoirs, Incidents in my Life (1863), the evening was reported in the local press by Maria's husband, William, who described how Home had managed to move a table about the room without anybody touching it.

As an important aside, William Hayden is usually depicted as a wealthy and influential newsman, congressional reporter, and eventual editor of the Boston Atlas, as well as being a dedicated abolitionist. This view, which has been the prevailing one since the late Victorian period, has recently been challenged by a direct descendant of Maria Hayden, who presents a compelling case that he was in fact a family physician. Based on the very limited evidence I could find of his published writings (one letter to the editor of an American newspaper concerning the couple's first few months in London, which, as you will see, reads exactly like an ordinary letter-to-the-editor), I would tend to agree. Equally, if he were a physician, it would go some way to explain why in later years Maria Hayden herself trained as a doctor, at a time when few women would have the opportunity or receive the encouragement to do so.

After achieving a certain degree of success at table rapping, Maria and her husband set sail for Britain in October 1852 with the sole aim of spreading the spiritualist message. Unfortunately the couple met with a rather hostile reception in London, as the letter written by her husband attests:

"22 QUEEN ANNE STREET, CAVENDISH SQUARE, LONDON, Feb. 4, 1853. Dear Sir– I think I promised, before leaving New York, in September last, to write to you and let you know how we succeeded in England…Thus far we have had much opposition to contend against, but have met with a remarkable few failures. The worst was that of two of Dickens' friends, who paid Mrs. H. a visit a few days after her arrival. They evidently came with the intention of having every thing [go] wrong, and they nearly succeeded to their mind." [excerpt of letter from William R. Hayden to Samuel Byron Brittan, editor of the American weekly periodical The Spiritual Telegraph]

George Henry Lewes, who was later to become the partner of the author George Eliot, played an especially mean trick on Mrs Hayden. Unseen by Maria, he wrote out a question on a sheet of paper: "Is Mrs Hayden an impostor?" The spirit controlling Maria rapped out: "Yes." Lewes went on to claim this as an admission of her guilt.

Though the literary world may not have been kind to her, Maria Hayden was not without her supporters. Both Sir Charles Isham, 10th Baronet of Isham, and Dr Ashburner, one of the Royal physicians, defended her very publicly in the press. Another convert to her cause was Professor Augustus de Morgan, philosopher and mathematician, whose work on logic, differential calculus, and probability is still remembered to this day. This is his recollection of one of the séances he attended:

"At a late period in the evening, after nearly three hours of experiment, Mrs. Hayden having risen, and talking at another table while taking refreshment, a child suddenly called out, "Will all the spirits who have been here this evening rap together?" The words were no sooner uttered than a hailstorm of knitting-needles was heard, crowded into certainly less than two seconds; the big needle sounds of the men, and the little ones of the women and children, being clearly distinguishable, but perfectly disorderly in their arrival." [from Professor de Morgan's preface to his wife's book, From Matter to Spirit, 1863]

It's been said that Maria had a limited mediumship consisting mainly of raps, but, as we've seen in the case of George Henry Lewes, she was also a "test" medium, in that she fielded questions where the answers were known only to the sitter. At least one person was greatly impressed by Mrs Hayden's talents in this regard—the tragedian actor Charles Young. Here is an account of their meeting—though be aware, confusingly it is in fact written by his son, the Rev. Julian Young, some years later:

"1853, APRIL 19TH. I went up to London this day for the purpose of consulting my lawyers on a subject of some importance to myself, and having heard much of a Mrs. Hayden, an American lady, as a spiritual medium, I resolved, as I was in town, to…judge of her gifts for myself…I was so astounded by the correctness of the answers I received to my inquiries that I told the gentleman who was with me that I wanted particularly to ask a question to the nature of which I did not wish him to be privy, and that I should be obliged to him if he would go into the adjoining room for a few minutes. On his doing so I resumed my dialogue with Mrs. Hayden.

Mr. Charles Young: I have induced my friend to withdraw because I did not wish him to know the question I want to put, but I am equally anxious that you should not know it either, and yet, if I understand rightly, no answer can be transmitted to me except through you. What is to be done under these circumstances?

Mrs. Hayden: Ask your question in such a form that the answer returned shall represent by one word the salient idea in your mind.

Mr. Charles Young: I will try. Will what I am threatened with take place?

Mrs. Hayden: No.

Mr. Charles Young: That is unsatisfactory. It is easy to say Yes or No, but the value of the affirmation or negation will depend on the conviction I have that you know what I am thinking of. Give me one word which shall show that you have the clue to my thoughts.

Mrs. Hayden: Will.

Now, a will by which I had benefited was threatened to be disputed. I wished to know whether the threat would be carried out. The answer I received was correct." [The Spiritualist, November 22nd, 1878]

Despite Maria Hayden's séances being essentially private, domestic affairs, by April she was charging a fee of one guinea (one pound and one shilling; i.e., twenty-one shillings in total) per person to attend them. Newsman or not, in May her husband William did set up a magazine, The Spirit World, the first spiritualist publication in Britain, though it only ran to one edition. The Haydens remained for a year in England, and returned to America at the end of 1853. Maria retained an active interest all things psychic even after becoming a doctor. She was noted for her clairvoyant abilities, as well as her aptitude for psychometry (diving insights by holding an object in her hands).

Although spiritualism may have failed to take root in London, it certainly found a home in Yorkshire when a Mr David Richmond, an American Shaker, brought the art of table-turning to the town of Keighley in the early 1850s. By 1854 "Tea and Table-Turning" had become an indispensable social pastime in the north of England, as the movement rapidly spread to neighbouring county of Lancashire. Funded by his Yorkshire contact, Mr David Weatherhead, at whose home he had first demonstrated table-turning, Richmond set up The Yorkshire Spiritual Telegraph in 1855. It proved far more successful than William Hayden's effort as the ground had been better prepared. Spiritualism had finally gained a foothold in Britain, but via the non-commercial domestic route.

Next month: Guess who's coming to dinner?—the extraordinary life of medium Daniel Dunglas Home

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Image:

Queen Victoria, 1887

Photograph by AlexanderBassano (1829-1913)

Published on November 01, 2013 07:14

•

Tags:

d-d-home, daniel-dunglas-home, david-richmond, maria-hayden, mediums, mrs-hayden, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Guess who's coming to dinner?—the extraordinary life of medium Daniel Dunglas Home

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the sixth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

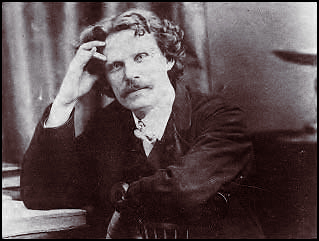

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the sixth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.Daniel Dunglas Home (pronounced "Hume") was arguably the most extraordinary medium of the Victorian era, not least because he managed to live the majority of his life in sumptuous style—courtesy of an ever-lengthening list of wealthy patrons—and all the while claiming not to accept a penny for his services.

He was born plain Daniel Home on March 20th 1833 in Scotland, in the small village of Currie, six miles south of Edinburgh. His father, the illegitimate son of the 10th Earl of Home, was a bitter and morose man who worked at the local paper mill, and his mother, who was said to possess second-sight, was locally thought to be fey. He was their third child, and at an early age was given over to the care of his mother's childless sister, Mary Cook (no relation to Florence Cook, the subject of the next post), who lived with her husband in the rapidly developing coastal resort and manufacturing town of Portobello, a few miles to the east on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth.

In 1842 at the age of nine he emigrated with his adoptive family, traveling steerage class to New York before settling for a time in Greeneville, Connecticut, on the banks of the Shetucket River. Daniel attended school there, and though a shy and retiring boy, he managed to befriend another student, whose name was Edwin. By the time Daniel turned thirteen the two had became so inseparable that they made a pact, one which had been inspired by a short story they both enjoyed of a man who returned from the dead to make his presence felt by his lady-love: if either were to die, he would try to make contact with the other from beyond the grave. It came to pass. When Daniel's family moved one-hundred-and-fifty miles away to Troy, New York, Daniel had a vision of his friend standing at the foot of his bed. He later learned that Edwin had succumbed to dysentery.

The family returned to Greenville, where they were reunited with Daniel's natural family, who had in the meantime emigrated from Scotland to settle in the sheep-farming town of Waterford, some twelve miles away. One evening in 1850, while the seventeen-year-old Daniel was suffering a bout of fever (quite possibly a symptom of the tuberculosis he was later diagnosed as having), he had a vision of his mother telling him that she had died that day at twelve o'clock. This too turned out to be true. Soon loud rapping noises, similar to those produced by the Fox sisters two years earlier, could be heard throughout the house. Exorcisms were performed, but to no avail. His aunt, Mary Cook, became convinced that Daniel had the devil in him and ordered him to leave her house. He went to stay with friends, thus beginning his life-long career as a professional non-paying guest.

His mediumship followed next. In March of 1851, around the time of his eighteenth birthday, Home found himself performing at the residence of William and Maria Hayden of Hartford, Connecticut. As I mentioned last time, if this was not his first séance, it was certainly one of his very first. The evening was reported in the local press (most probably in a letter to the editor) by Mr Hayden, a family doctor, who described how Home had managed to move a table about the room without anybody touching it. His fame soon spread throughout New England, and then to New York and Massachusetts, while his talents became ever more diverse. For the next four years he would give as many as six séances a day offering a mixture of table turning, spiritual healing, communication with the dead, the partial manifestation of body parts (such as hands), and acts of levitation and of self-levitation in the homes of his patrons, who generally adored him. One particular couple, Mr. and Mrs. Elmer, who were rich and childless, offered to adopt him and make him their heir. Presumably he refused their offer, as it was conditional on his changing his surname to Elmer, which he never did. Towards the end of this period his health declined. In 1854 he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and advised (by Maria Hayden's husband William, I suspect, who had returned from England at the end of the previous year) to take a rest cure in Europe. He gave his final American séance in March 1855 in Hartford, then set sail for Liverpool, England, just days after his twenty-second birthday.

Having added the "Dunglas" part to his name, Home took up residence at a hotel in Jermyn Street, London, as a guest of the owner, the well-to-do property speculator, publishing magnate and barrister Edward William Cox. It is likely that he and Cox, who took a deep—though not uncritical—interest in spiritualism, shared a mutual friend: Maria B. Hayden. Though weakened by the tuberculosis, it was here that Home held sittings for many influential people from London society. As the list of his acquaintances grew, so did the number of offers of accommodation. He moved his base of operations to the home of the wealthy Rymer family of Ealing, and financed by them, set off on a tour of Europe in 1856 in the company of their eldest son. Whilst in Italy the two had a rather acrimonious falling-out and swiftly parted ways, but not before Home had established his reputation on the Continent as a first-rate medium.

Over the next few years he performed extensively throughout Europe, always for the royal, the rich and the famous (Queen Sophia of the Netherlands and Napoleon III among them), and always only at private sittings. In Paris in 1857 he was offered £2,000 for a single séance by the Union Club, but he declined their offer. In 1858, at the age of twenty-five, he married Alexandria de Kroll, the daughter of a Russian noble, whom he had met on a trip to St. Petersburg. The best man at the wedding was the novelist Alexandre Dumas; the union had the blessing of Alexander II, Emperor of Russia. But the marriage was not to last. Alexandria died of tuberculosis in 1862.

By this point Home had already resumed giving private sittings in Britain. In 1863 he published the first of two memoirs, both of which he entitled Incidents in my Life, detailing his various psychic successes amongst the titled and the rich, but referring to his clients in ciphers such as "Countess O" (Countess Orsini), "Count de K" (Count de Komar), and "Princess de B" (Princess de Beauveau). He was now thirty, and still relied on his charms and pallid good-looks, in addition to his friends, to make his way in the world. In 1866 he received, for the second time in his life, an offer of adoption, this time from a wealthy widow named Mrs. Jane Lyon. She settled £60,000 on Home on the condition that he change his surname to Home-Lyon. The offer must have been appealing, for this time he did change it. In addition to receiving letters of affection from her newly-appointed heir, Mrs. Lyon expected him to provide her with an entrée into polite society. Although he dutifully wrote her letters, when the anticipated introductions didn't materialize she demanded her money back. Home failed to comply and she brought charges against him, claiming he had extorted it from her by misrepresentation. The case was tried at the Court of Chancery. Home lost and was obliged to return the money.

The press had a field day, but his society friends stood by him throughout. In 1867 he made the acquaintance of the twenty-six-year-old Lord Adare, the future fourth Earl of Dunraven, who had recently been appointed as a war correspondent to the Daily Telegraph. The young Viscount, who, to put it tactfully, struggled with his sexuality, became infatuated with Home—clearly as others had done before him. He also started documenting the extraordinary feats he saw. On Sunday December 13th 1868 Home performed what was to become his most famous act of levitation when, in the presence of Adare and two other witnesses, he floated head-first out of a third-story bedroom window, returning feet-first through the windows of a sitting room on the other side of the house.

One person who bore witness to Home's levitations on many occasions was the noted scientist William Crookes. Between 1870 and 1873 under carefully controlled conditions he put a number of mediums to the test—Daniel Dunglas Home, Kate Fox of the Fox sisters (who travelled to Britain in 1871 under the patronage of a New York banker, then married the London barrister, Mr. H. D. Jencken, the following year), and the materializing medium Florence Cook, the subject of the next post—and found all three to be capable of producing perfectly genuine results.

By 1871, however, three years before the publication of Crookes's report, Home was exhausted. At the age of thirty-eight he retired as a medium due to ill-health. In the October of that year he married Julie de Gloumeline, yet another wealthy Russian, with whom he lived until his death in 1886. He was buried in the Russian cemetery in St Germain, Paris. After his death, his widow published an account of his career, but it failed to become as popular as Home's own self-penned testimonies.

Next month: the full-body materializations of Florence Cook

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Images:

Daniel Dunglas Home (1833-1886)

Photographer and date unknown

Published on December 01, 2013 06:13

•

Tags:

d-d-home, daniel-dunglas-home, mediums, seances, spiritualism, spiritualists, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances

Why the Victorians saw ghosts: Caught on camera—the darker role that photography played in spiritualism

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.

While I was researching my novel,

The Bridge of Dead Things

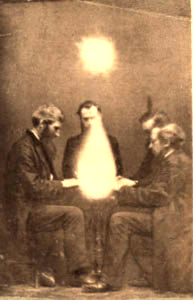

, I came to understand that the Victorian vogue for spiritualism did not happen in a vacuum. It grew out of a very specific culture, at a particular point in time, and it fulfilled a number of surprisingly different needs. This is the eighth in a series of posts that examines various influences on the development of spiritualism.It probably started out as a happy accident: a glass plate that had previously been exposed but not yet developed was placed back into the camera and exposed for a second time. The resulting double-exposure, when printed, would have produced a somewhat ghostly effect. With a certain amount of pre-planning and a little tweaking here and there, the effect could be heightened and repeated time and time again. Such is undoubtedly the case with the American William H. Mumler (1832-1884), who started out as an amateur photographer in Boston. Realising that he could make his living by photographing New England’s many mediums in the company of assorted spirits, he quit his job as an engraver and moved to New York in the early 1860s to take up his particular brand of photography full time. His most famous photo appears to show Mary Todd Lincoln flanked by the spirit of her dead husband.

In the April of 1869 Mumler was brought to trial for fraud after it was alleged that he’d broken into houses to steal the portraits of his sitters’ dead relatives. One of the witnesses to testify against him was the showman and entrepreneur P. T. Barnum. Barnum had commissioned the photographer Abraham Borgadus to make a portrait of him accompanied by Abraham Lincoln’s spirit, just like Mary’s, to demonstrate how easily it was that such photos could be faked. The photograph was presented in evidence at the trial. Although Mumler was eventually acquitted, his career as a spirit photographer was over.

How could people be so gullible? To answer this question it's important to appreciate the naivety of the general public in their ability to read and understand photographs at the time. The following extract is from Statement of a Photographic Man, from Volume 3, Part IV (Street artists) of Henry Mayhew's 1861 work, London Labour and the London Poor. The speaker is a young working-class man from the slums of Lambeth, who, on tiring of busking for his living, borrows money for a camera and darkroom equipment and sets up as a photographer with his mate Jim, though both men lack the technical expertise required. Through trial and error his work gradually improves, but along the way he dreams up a number of hilarious tricks and dodges to mask his failures, one of which, the fobbing-off on impatient customers of hastily-wrapped specimen-photographs taken from his window display, he discusses here:

"…We have made some queer mistakes doing this. One day a young lady came in, and wouldn't wait, so Jim takes a specimen from the window, and, as luck would have it, it was the portrait of a widow in her cap. She insisted on opening, and then she said, 'This isn't me; it's got a widow's cap, and I was never married in all my life!' Jim answers, 'Oh, miss! why it's a beautiful picture, and a correct likeness,'—and so it was, and no lies, but it wasn't of her. Jim talked to her, and says he, 'Why this ain't a cap, it's the shadow of the hair'—for she had ringlets—and she positively took it away believing that such was the case; and even promised to send us customers, which she did.

"There was another lady that came in a hurry, and would stop if we were not more than a minute; so Jim ups with a specimen, without looking at it, and it was the picture of a woman and her child. We went through the business of focussing the camera, and then gave her the portrait and took the 6d [half a shilling]. When she saw it she cries out, 'Bless me! there's a child: I haven't ne'er a child!' Jim looked at her, and then at the picture, as if comparing, and says he, 'It is certainly a wonderful likeness, miss, and one of the best we ever took. It's the way you sat; and what has occasioned it was a child passing through the yard.' She said she supposed it must be so, and took the portrait away highly delighted.

"Once a sailor came in, and as he was in haste, I shoved on to him the picture of a carpenter, who was to call in the afternoon for his portrait. The jacket was dark, but there was a white waistcoat; still I persuaded him that it was his blue Guernsey which had come up very light, and he was so pleased that he gave us 9d [three-quarters of a shilling] instead of 6d. The fact is, people don't know their own faces. Half of 'em have never looked in a glass half a dozen times in their life, and directly they see a pair of eyes and a nose, they fancy they are their own.

"The only time we were done was with an old woman. We had only one specimen left, and that was a sailor man, very dark—one of our black pictures. But she put on her spectacles, and she looked at it up and down, and says, 'Eh?' I said, 'Did you speak, ma'am?' and she cries, 'Why, this is a man! here's the whiskers.' I left, and Jim tried to humbug her, for I was bursting with laughing. Jim said, 'It's you ma'am; and a very excellent likeness, I assure you.' But she kept on saying, 'Nonsense, I ain't a man,' and wouldn't have it. Jim wanted her to leave a deposit, and come next day, but she never called…"

The photographs of the spirit of Katie King, however, stretch credulity to a brand new level. The first set was taken in a hotel room at Florence Cook's request by the reporter W. H. Harrison with an eye to publication in The Daily Telegraph; the rest—the ones we're most familiar with today—were taken by the scientist William Crookes at two private but well-attended soirées in his own home. In both cases neither the negatives nor the prints were tampered with in any way, and, considering the circumstances, it seems unlikely that Crookes (if not Harrison too) set out to perpetrate any fraud. But, studying them, it's hard to imagine that anyone was fooled. The words of Edward William Cox when describing one of Katie's later appearances sum up the situation neatly, "They were solid flesh and blood and bone."

People see what they want to see. The photo you see below is another interesting case in point. It was taken by a sixteen-year-old in 1917 and features her nine-year-old cousin sitting in their garden surrounded by a number of posed, cut-out fairy figures.

Again, there is no double-exposure or tampering with the print. What you see is exactly what you get. Yet this image was passionately championed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series, who, despite his naivety, was a great believer in spiritualism. And he was not the only person to be taken in. Here is what Edward Gardner, a leading member of the Theosophical Society at the time, had to say: "…the fact that two young girls had not only been able to see fairies, which others had done, but had actually for the first time ever been able to materialise them at a density sufficient for their images to be recorded on a photographic plate, meant that it was possible that the next cycle of evolution was underway."

Frances, the young girl in the photo, finally admitted to the fraud in later life: "I never even thought of it as being a fraud—it was just Elsie and I having a bit of fun and I can't understand to this day why they were taken in—they wanted to be taken in."

Fifty years after Mumler, professional debunkers—often stage magicians who objected to their artistry being brought into disrepute by spiritualist hoaxers—were still at work trying to expose the tricks involved in the production of spirit photography. Here is one of the most recent examples I could find, showing Houdini, one of the greatest escapologists and debunkers of all time, with (yet again) the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, who must surely be the most photographed "spirit" on the planet.

Next time: Ghost-grabbers—tackling the spirits head-on

Find out more at michaelgallagherwrites.com

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.

Why the Victorians Saw Ghosts – An Illustrated Guide to 19th Century Spiritualism is now available as an ebook. It retails for US$2.99 in most online stores, but you can download it for free. You’ll find details and links on the My Shout page of my website.Images:

Seance conducted by John Beattie, in Bristol, England

Photograph by Eugene Rochas, 1872

Mary Todd Lincoln with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln

Photograph by William H. Mumler, date unknown but presumably prior to 1869

P. T. Barnum with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Barnum's request

Photograph by Abraham Bogardus, 1869

William Crookes with the spirit of Katie King

Photograph by William Crookes, circa 1873

Frances Griffiths surrounded by fairies

Photograph by Elsie Wright, 1917

Houdini with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln, made at Houdini's request

Photographer unknown, circa 1920-1930

Library of Congress

Published on February 01, 2014 06:14

•

Tags:

barnum, crookes, florence-cook, houdini, lincoln, mayhew, mediums, mumler, pictures-of-ghosts, seances, spirit-photography, spiritualism, spiritualists, statement-of-a-photographic-man, victorian-mediums, victorian-seances