Victoria Noe's Blog, page 6

June 14, 2018

Why I Love Doing Research for My Books

I can’t say I’ve always liked doing research.

I can’t say I’ve always liked doing research.

The one universal requirement when I was in grad school at the University of Iowa was a truly painful class, “Intro to Graduate Research”. The fact that it was held at 8:00 am three days a week – while I was up late in rehearsal and production most of that semester – made it almost unbearable. I sat in the last row, my back to wall, with another theatre student, as we tried unsuccessfully to stay awake for every class. What I remember most were endless discussions of footnotes. That defined “research” for me that semester.

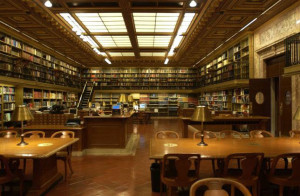

But things looked up the following semester. I was writing my comprehensive exams on the development of the director-choreographer in American musical theatre. In NYC for spring break, I went to as many Broadway shows as possible, interviewed Bob Fosse in his apartment near Carnegie Hall and made my first visit to the NY Public Library at Lincoln Center. When I walked in, I knew for sure that I was doomed.

Books were the least of the collection, then as now. There were scripts and scores, cast albums, programs, posters, photographs, filmed interviews and performances. There were artifacts, like the cigarette cases Cole Porter’s wife gave him on opening nights of his shows. It was an archive of theatre history that spoke to me louder than any class I ever took. “I could live here,” I remember thinking to myself. All these years later, I still feel that way when the elevator door opens on the third floor.

Writing nonfiction requires a special attention to research, an obligation to get the facts straight. When you’re researching a topic that is fascinating and complex, one that conveys deep emotions, it’s easy to fall down the rabbit hole. But, oh…the treasures you’ll find.

I’ve done a lot of research for my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community). I could probably continue for years and still not be finished. That’s okay: it means I will have even more material for freelance articles and presentations.

There have been times, often in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room at the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue where silence is strictly enforced, when I had to cover my mouth to keep from squealing in delight. I’ve found documents written by friends, some living, some dead. I’ve found oral history interviews that brought tears to my eyes. I’ve found programs from memorial services and flyers from long-forgotten meetings, fundraisers and protests.

It’s too soon to share many specifics. I’m a little too superstitious to do that right now. Even if I am able to include the stories of over 150 women, there are many more stories that need to be told. I’m sure there are other writers out there faced with this same embarrassment of riches, as I’ve come to refer to it. I was really stressed about this for a long time. But now I’m not.

I’m grateful to have identified a topic that is bursting at the seams to be shared. What I feared would be a difficult subject to research has been the exact opposite. Not only easy, but a joy.

Sharing stories. What could be better?

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

June 6, 2018

Grief and Depression

My late father used to say that there should be a psychiatrist on every corner and they should be free.

My late father used to say that there should be a psychiatrist on every corner and they should be free.

Wouldn’t that be nice?

To have easy access to mental health support and not have to worry about co-pays, referrals or limits on coverage?

Damn right it would be nice.

But would it be enough?

The death of handbag designer Kate Spade shocked her friends and fans. A privileged, talented, successful woman living on Park Avenue who suffered from depression and certainly was able to obtain quality mental health support died by suicide.

As with most of these deaths, we’ll never know what led her to that decision. While the family knew of her struggles, many friends are left recounting past conversations, searching for clues they missed. Even if they find them and forgive themselves, they will not feel much comfort.

Mental health is a frequent topic of conversation. It always comes up when there’s a mass shooting or other horrific attack. Today it’s about suicide and Kate Spade. But there’s a lot in between that goes unnoticed.

Does grief equal major depression? The symptoms of grief and major depression often overlap: sadness, sleep disturbance, loss of appetite, for example. They’re not the same thing, but they can be connected. Some professionals believe there should be a time limit on grief, and if it lasts too long, should be classified as depression.

I know people who insisted they were not depressed, though it was clear they were. Their grief – usually for a spouse – never abated, even years later. It was easier to consider themselves grieving, because to admit they were depressed brought baggage: therapy, medication, stigma.

Let’s face it: people are a lot nicer to you if you say you’re grieving than if you say you’re depressed. They probably won’t dismiss your grief out of hand as something to just get over. The same with anxiety or phobias: those who have never experienced them tend to minimize their power. But they can disrupt your life as surely as a broken bone or cancer.

That’s where stigma comes in, from others and ourselves. And it’s time to change that.

Imagine a world where going to your therapist was looked at the same way as going to your dentist: routine maintenance. If you need more work, you go more often, maybe see an orthodontist. But you don’t stop going. You go on a regular basis, to maintain your health, because you know if you don’t, you’ll pay the price. No one questions it or bullies you about it. It’s a non-issue.

That psychiatrist on the corner would be pretty busy, just like your dentist is busy. Friends wouldn’t feel guilty for not being able to save their friends from suicide or the emotional pain that sucked the joy from their lives. People who now suffer needlessly would get the help they deserve.

That’s not to say people wouldn’t be sad or angry, that they’d never grieve or feel despair. That’s not to say that they wouldn’t refuse to get help. But they’d know for sure that help was always there for them, no excuses. Unconditional help.

Something we all need.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

May 30, 2018

An Embarrassment of Riches

My color coded files last fall.

My color coded files last fall.You’d think I’d be used to this by now.

I write nonfiction and over the past eight years I’ve done research on a variety of topics related to my books: moral injury, the AIDS epidemic, 9/11, military procedures, men’s health and always, grief. There is no shortage of material available on the internet, in films and TV shows, in poetry and song lyrics, in clinical trials, books and magazine articles.

One of my guilty pleasures is finding a resource that is both appropriate and obscure. Sometimes they’re found in books that have been out of print for decades; I found one in London last month at Gay’s the Word bookstore. Sometimes they’re interviews in now-defunct publications. I have one of two reactions: either “I forgot about that” or “I didn’t know that”. To be honest, that’s the kind of reaction I hope for from my readers.

There’s a lot of that in the next book. A lot.

I knew when I started writing Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community that this would be the case. I knew a year ago I could write 50,000 words just on the straight white women in New York City who have had an impact on the AIDS epidemic. Tempting though that may be, my book is much more diverse.

There will be, as I originally assumed, well over 100 women in the book. Some will have brief mentions; others will have multiple pages devoted to them. They are from around the world, all ages, living and dead. My office is full of overflowing file drawers, jammed book shelves, stacks of article reprints.

So many women, so many terrific stories. And yet…

I’ve already started to brace myself for the inevitable outrage: “Why isn’t X in your book?” A lot of the stories in the book were suggested by people who have a personal connection to these women. They want to see those stories shared in the book. But some of them will be disappointed.

I feel awful about that.

I feel awful that even with the best of intentions, no book can include all of them. Well, awful and pleased, because that means there are a lot of stories that deserve to be told. So I’m giving some thought to addressing how to share the ones that don’t fit in the book.

What I hope the book will do, ultimately, is to encourage other straight women who have worked or volunteered in the AIDS community to tell their stories. My book is not the only way to do that, so I hope those women find their voices. Whether they write their own memoir, or make a StoryCorps recording, or sit down for an oral history project, I want them to know that there is power in their stories.

We’re well into the fourth decade of the epidemic. The recognition of what these women accomplished – and continue to this day – is way overdue. I can get the conversation started, but it won’t end with my book. At least I hope not.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

May 23, 2018

Memorial Day for the Friends Left Behind

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery

Jefferson Barracks National CemeteryThe first funeral I ever went to for someone close to my age was 50 years ago this summer (and no, I can’t believe it’s been that long).

I grew up with Marianne and Ernie. Marianne was my senior big sister when I was freshman in high school. Ernie, her older brother, was studying to be a priest. I don’t remember why he left the seminary but after a year of teaching high school, he was drafted. A week after he arrived in Vietnam, he was reported missing. I remember arguing at my 16th birthday sleepover that surely he would be found alive, but that didn’t happen. A month later, his body was found.

Ernie was the first guy in our parish to die in the war, though sadly, not the last. He was a good-looking Italian, who as I recall, was kind to everyone.

Our parish church was tiny, so if you sat in the back under the choir loft it felt positively claustrophobic. That’s where I sat, on the center aisle, for Ernie’s funeral. You have to remember that by late summer of 1968, we’d already endured the escalation of the war, the riots at the Democratic convention in Chicago and two assassinations. It felt like the world was spinning out of control. This funeral wasn’t a front page headline, but it added to the feeling that the world was coming to an end.

I remember what I wore, but I don’t remember my parents being with me at the funeral. It’s possible they were at work. It’s also possible that they were sitting next to me. Like I said, I was 16 and I’d never been to a funeral of anyone that close to my age.

What I remember most clearly is the procession up the aisle next to me: the devastation on the faces of the parents, my girlfriend’s tears, and the casket, which stopped next to me. Ernie was there in the casket, under the flag, right next to me. And I wanted to scream.

I think of Ernie now and then on Memorial Day, his life cut short like so many others. And I know I’m not alone. Many of you reading this also remember a friend who died in service to their country. So do those who served with them.

If you ask any veteran, any age, they will tell you about the friends they could not save. They will speak of them as young and energetic and very much alive, even if it’s been decades since they died. The photos of men and women in combat, and the formal portraits of them in their dress uniforms, are how we remember them.

I don’t think of Ernie in his uniform. I think of him in the choir loft playing the organ for a weekday funeral. I was still in grade school, among the lucky few girls excused from class to sing. He was kind and patient, and his absence is still felt.

That’s what Memorial Day is about: remembering. Honoring the memory of those who gave their lives for us. Maybe you have someone special to remember this Memorial Day. But even if you don’t, take a minute to pause during your holiday and remember the reason you have the day off. They deserve at least that much.

Friend Grief and the Military: Band of Friends is available in paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Kobo and iTunes. For Memorial Day and every day, 25% of the purchase price benefits Military Outreach USA.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

May 16, 2018

Rebooting Your Writing

I stepped back from most of my writing a few days before Christmas. That’s when my mother broke her hip and had surgery. In the weeks that followed, as she struggled through rehab, I, too struggled to write. I kept up my blog and my email newsletters (with varying degrees of success). But by the time she died March 16, I wasn’t writing at all. It’s been two months now, months where my only writing was limited to thank you notes, filling out legal and financial forms and paying bills.

I stepped back from most of my writing a few days before Christmas. That’s when my mother broke her hip and had surgery. In the weeks that followed, as she struggled through rehab, I, too struggled to write. I kept up my blog and my email newsletters (with varying degrees of success). But by the time she died March 16, I wasn’t writing at all. It’s been two months now, months where my only writing was limited to thank you notes, filling out legal and financial forms and paying bills.

Because I’d been suffering from a recurrence of symptoms related to post-concussive syndrome, I checked in with my neurologist the week after my mother’s funeral. He’s a big fan of my books. I told him that despite my issues, I wanted to start writing again. “You have to get back to it. But not yet. You’ll know when you’re ready.”

I’ve kept those words in my mind the last two months, as I navigated the PCS and grief. It hasn’t been easy. On an intellectual level I’m very familiar with what I’m going through. The emotional part of both those conditions is not something that’s easy or even predictable. While my mother was sick, I had to push a lot of those feelings aside. Now I can’t and it’s overwhelming at times. For those who have experienced PCS and/or grief, you know what I mean.

Last week I wrote my first blog post since March. Next week I’ll send out my first email newsletters in longer than that. Those are big steps, believe me. And though I’ve done more than a little marketing in the past month, tomorrow I go back to working on my next book.

If you’ve taken a break – enforced or voluntary – from your writing, you know it can be intimidating to return. Maybe you’ve kept up with your emails (I haven’t). Maybe you’ve participated in online discussions (I’ve dipped my toe in now and then). Or maybe you had to step away from all of it.

So when you decide it’s time to get back to writing, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by what you missed and discouraged by the thought of starting over. Here are a few tips that may help you as they’ve helped me:

Take a deep breath. Seriously. If you open your email account and instantly tense up in panic, you need to take a deep breath. Remember: most of those emails are irrelevant. They’re subscriptions you maintain to keep in touch. Start with the oldest in each category and work your way to the present. Take your time. Take breaks. What helps me is to scroll through and delete the ones that have expired offers or are not relevant to what I’m doing. Delete them. You’ll feel a disproportionate sense of accomplishment, trust me. And your inbox won’t look so intimidating.

Make a timeline. This is a little different than just making a to-do list. I guarantee that making a to-do list will stop you in your tracks. You will be overwhelmed again by what you need to do. That’s why I put my to-do lists in a timeline. I start with the things with hard deadlines, such as submissions or meetings. Then I add tasks that are not time sensitive, but shouldn’t be ignored (updates to web pages, filing, etc.). Hopefully you can avoid my weakness, which is to load up the first day, ensuring that I will fall short. But if you can spread out the tasks over a week or a month or even longer, the list will cease to be a barrier to your return.

Set a goal or two or three. This is connected to the timeline. I’m deep in the 2nd draft of my next book and I typically send my books to the editor when I’ve finished the 4th draft. I’ve set a deadline of the last week of July to finish that draft and hit ‘send’. In order to do that, I had to go back to my timeline to determine internal deadlines: finish 2nd, 3rd and 4th drafts; request all permissions for quotes and images; transcribe remaining interviews.

Reach out. I’m grateful to the friends who kept in touch with me during my mother’s final illness and afterwards. Some of them are writers who understood the challenges of caregiving and propped me up when I felt like I was sinking. When I started writing, I made a promise to myself to ask for help. When I stopped writing, I made the same promise. I will be forever grateful to them for saying, “It’s okay. You’ll be back better than ever. Just do what you need to do right now.”

Be good to yourself. Whatever your reason for not writing – caregiving, writer’s block, illness, family crisis – recognize that you have been through a lot and survived. Give yourself credit, even when it feels like credit is the last thing you deserve. Turn on the music in your car. Take yourself out to lunch. Go for a walk or a swim. Do whatever makes you feel good, even if it’s just for a few minutes. Then do it again. And again. Every damn day.

In many ways, I see rebooting my writing as a golden opportunity. I’m not starting from zero, but I have the chance to make some long-overdue changes. And that attitude is what will fuel you: not the desperation of “I need to make money”, although that’s not unimportant.

Because the truth is, no matter what you write, your life experiences shape your writing. And knowing that you’ve been through hell and back, that you are in fact a stronger person for it, will lift your writing in ways you can not yet imagine.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

May 9, 2018

The Disadvantage of Writing About Grief

thegiftofwriting.com

thegiftofwriting.com“Well, you write about grief, so this is…”

The woman at my mother’s wake didn’t finish her sentence. It just kind of faded with her shrug. She didn’t quite know how to get out of the hole she’d dug for herself. But I’m pretty sure the ending she was looking for was “easier for you”. I have to admit I didn’t offer her any help.

Many people who write about grief are trained, certified professionals. They’re psychologists, therapists, chaplains, counselors. For some of them, grief was what inspired their careers. The rest of us are not professionally trained. But we all have one thing in common: we experience grief. Everyone does, in their own way.

People have come to me over the past five years, asking for advice or referrals as they struggle with their own grief. I’m always happy to share resources, with the caveat that I’m no substitute for a professional grief counselor.

As a society, we run away from grief. Even as we insist that everyone grieves differently and at their own pace, we encourage grievers to move along. Grief – like death – makes people uncomfortable. Any kind of emotional pain is to be avoided. We try like hell to control it, to ignore it, to push it aside, but ultimately we can’t. Unresolved grief always bites us in the butt, sometimes years later.

When someone close to you dies, in the short term you’re consumed with details. You have to focus on decisions that are time-sensitive, so you probably don’t feel like you have the luxury of grieving. And while that’s typical, grief is not a luxury. It’s a necessity.

When I first started writing about grieving the death of a friend, the working title of what I assumed would be only one book was It’s Not Like They’re Family. That was the reaction of a lot of people when you told them your friend died. They’d brush it off as less important than the death of a family member. But I’ll bet as you read those words, you’re thinking of a friend of yours – from the neighborhood, from school, from work – whose death left you reeling. Compounding your grief was the realization that those around you didn’t respect your loss.

I like to think things have changed, though I’m not willing to believe that my books have had much of an impact. But my writing has made me more sensitive to the friends left behind.

There were far fewer friends left when my mother died at 89 than when my father died in 2005. But the grief I saw in her oldest and dearest friend (they met in high school during World War II) will stay with me forever. They both outlived their husbands, who’d been friends since kindergarten. They could speak in that shorthand common to long-time friendships. And the grief is just as profound. “They’re having a party without me,” she grumbled with a shaky smile. That’s how it felt.

Writing about grief doesn’t making grieving easier, except maybe on an intellectual level. But grief isn’t intellectual: it’s pure emotion. I can step back and identify what I’m going through, but it doesn’t make it any easier.

It’s taken me awhile to get back to my writing. Post-concussive symptoms flared up even before my mother died, so that lengthened my physical recovery. A week after my mother’s funeral, my neurologist told me, “You need to get back to writing. But not yet. You’ll know when you’re ready.”

Since you’re reading these words, it appears I’m ready. Next week I’ll go back to the second draft of the book I abandoned at Christmas, when my mother’s health took a turn for the worst. My email newsletters will be back within the next few days. Honestly, I’m looking forward to it.

That doesn’t mean I’m done grieving. It does mean I’m in a different place. Did my writing help? I don’t know yet. It’s possible. I do know that my mother is always with me, just like my father, my grandmother and too many friends to count. And I’ll continue to take them along on this ride, wherever it takes me.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 15, 2018

Not Everyone Knows What You Know

lifesuccess.com

lifesuccess.comWe all know things: some trivial, some important. We learned them in school, in the home, on the streets, at work. We know so many things, in fact, we may not realize that there are people out there who do not share our depth of knowledge.

In conversations with dozens of doctors and nurses these past few weeks, I’ve noticed that many, if not most, are good at explaining things. They tell me about a procedure or options in medical jargon. I know a fair amount, but not everything, so I ask them to explain. Most of them are not annoyed.

A few, though, are insulted. They don’t feel the need to explain themselves; after all, they’re the authorities on the subject. What could I possibly have to add to the conversation (which to that point has been one-sided)? As it turns out, I often have critical information that affects the decisions being considered. That’s a little different situation, though they’re also surprised when I understand what they’re talking about.

It’s the same with writing and publishing. I went into this determined to ask questions. I had to: I knew nothing. As time went on, I – thankfully – learned a lot. I pay it forward every chance I get. And when I do, I try to remember to explain things in a way that’s easy to understand.

I included that quote from Rachel Maddow because there are times when I’m watching her show and my eyes glaze over: ‘why is she explaining that again?’ She’s really good at it, but I get impatient. Then I remember that every viewer is coming from a different place, as far as information.

I write nonfiction. I deal with facts and real people in all my books. Some of it’s contemporary, some of it’s historical. But I’m responsible for telling those stories accurately. That’s where ‘not everyone knows what you know’ comes into play.

When I’m writing, I know the subject matter. I understand it. I’m immersed in it. But that’s not enough. I have to be able to explain something new to the reader, to make sure they understand what I take for granted.

Case in point: I was lucky to have an editor for the Friend Grief books who is considerably younger. She grew up in a world with HIV/AIDS. She doesn’t remember before the virus appeared, or what the response was to it in the 1980s.

When I sent her the manuscript for Friend Grief and AIDS: Thirty Years of Burying Our Friends, she sent it back with comments in the margins: “Seriously? This happened? Are you kidding me?”

I forget sometimes that not everyone remembers those dark early days. That’s why I tell the stories: so they learn and understand. She reminded me of that, with additional comments asking me to expand certain passages. Those edits made the stories not only more understandable, but more powerful.

At times I’ve been taken aback when I’m in the middle of a story or explanation and someone says, “I don’t know what that means.” Then I realize, much to my embarrassment, ‘of course’. It doesn’t annoy me, like it annoys surgeons and politicians and others not used to explaining themselves.

A couple years ago I was at Writers Digest Conference. I’ve gone every year since 2011 and I always learn a lot. But that year something changed. For the first time, other attendees asked me for advice. They weren’t asking for directions to the restrooms; they needed help. Their questions were basic, but not unimportant. And I realized that I was that person at my first conference: I was the one asking questions, the one who knew less than nothing, but wasn’t afraid to admit it. I answered a lot of questions for a lot of people that weekend and I was glad to do it. It was yet another valuable lesson for me.

Don’t hoard your knowledge like a priceless secret, doled out to only a deserving few you consider your peers. You weren’t always as knowledgeable as you are right now.

Not everyone knows what you know. It’s up to you if you’re willing to share.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 7, 2018

I Am Not A Sandwich

You see them at Nordstrom or neighborhood diners or in cafeterias: middle-aged women (occasionally men) and an older parent. The child is in charge without letting the parent know they’re in charge. They explain the menu to them, ask questions of the wait staff, smiling though the tension that’s alway there. Sometimes they help their parent walk, or cut their food. Their conversations are superficial: the food, the temperature in the room, the noise, maybe family news.

You see them at Nordstrom or neighborhood diners or in cafeterias: middle-aged women (occasionally men) and an older parent. The child is in charge without letting the parent know they’re in charge. They explain the menu to them, ask questions of the wait staff, smiling though the tension that’s alway there. Sometimes they help their parent walk, or cut their food. Their conversations are superficial: the food, the temperature in the room, the noise, maybe family news.

Occasionally their cell phone rings. They look down, annoyed, debating if they should answer, but when they do, it’s almost always work-related. You can see their bodies tense up more when they speak, juggling some new complication in their already jammed lives.

I’m one of those people. My mother is 89. She lives 300 miles away from me. So I drive down from Chicago whenever I can to help my sister help her.

For years now, I’ve been told that I’m part of the “Sandwich Generation”, the one that finds itself taking care of children and parents, often at the same time.

Bullshit.

I like sandwiches. I’m partial to the chicken club sandwich at Nordstrom and shrimp po’boys at Heaven on Seven, as well as the cute little sandwiches they serve at Bosie Tea Parlor. They’re yummy. I eat one and I feel good, maybe even happy. Nothing about my life is reminiscent of a sandwich.

I struggled for the proper metaphor twelve years ago, when my dad was going through chemo. I had a husband, a 10 year old daughter, a part-time job and a home-based business in Chicago on my mind whenever I drove to St. Louis. I had the realization of my father’s limited time on my mind when I drove back. Without the benefit of a TARDIS, I had to choose where to be, who to support, every day. Now I’m doing it again.

I don’t feel like the filling of a sandwich. I feel like I’m on the rack, the torture device favored by Torquemada during the Spanish Inquisition. I’m not being squished between two lightly toasted slices of marble rye: I’m being pulled in two opposite directions at the same time.

Every day you weigh the pros and cons. Every day you make a decision that is less than perfect, one that is guaranteed to leave you feeling guilty and inadequate. Those around you – friends, family, coworkers – will either have very vocal opinions or won’t understand why you have to do so much.

You are a slave to your to-do list, which never shrinks. You’re online or on the phone while sitting in doctors’ waiting rooms, filling out forms, making appointments, praying you wrote down everything correctly and won’t forget to share it all with siblings, spouses and children.

And in quiet moments that make you feel even more guilty, you ask yourself, “What about me? How long can I keep doing this? Will I ever catch up on my sleep?”

Most of my friends have been on the rack at least once. Many of them were lucky; their parents lived in the same area. Some of us are hundreds, even thousands of miles away.

Last week I wrote about the beginning of a health crisis for my mother. After that post, things got worse, though are now (hopefully) better.

Meanwhile, my book is on hold, travel anywhere else is on hold, book signings and speaking engagements are on hold. That’s okay. I’m able to do this for Mom and I would be devastated if I couldn’t.

I should’ve finished our taxes over a week ago. I should’ve completed certain tasks related to my next book. In fact, I should’ve finished the book and sent it to the editor. I should’ve sent my web designer the updates for my website. Personal things are starting to fall through the cracks. Someday everything will get done, but not today.

It’s almost impossible to concentrate at times without being distracted by those ‘shoulds’. And that’s when I most feel like I’m on the rack. I need to be here, but I need to be other places, too. I don’t have coworkers who can take up the slack. I don’t have accrued sick days or FMLA. My business is me and me alone. At the same time, I need to be physically present to make decisions that are too often a matter of life or death.

We struggle to ask for help, guilt-ridden that we can’t do everything. If we’re lucky, we have family and friends to share the load. Sometimes we have to pay for assistance, a financial model that is not sustainable, even if you are lucky enough to have long-term care insurance.

I don’t have a solution for this. I’ve heard blame assigned to my generation for failing to continue the model many of us grew up with: several generations in one household. But even living in the same house doesn’t eliminate the feeling of being on the rack. Will she be all right while I go to work or the grocery store? Can we afford in-home care? Should I take advantage of Family Medical Leave, or more likely, can I afford to take advantage of it? It’s not that we don’t want to help. It just that we can’t do it all, at least not all the time.

So for the time being, I will continue to feel like I’m one of Torquemada’s prisoners: stretched in two different directions. I will struggle to take care of myself so that I can continue to whittle down those to-do lists. And I will remind myself that I’m lucky to be able to help my mother when she needs it the most, and pay her back for all the times she took care of me.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 27, 2018

“You Could Write a Book About This”

My mother made that suggestion on Sunday, as I sat on the bed in her hospital room. A long-awaited doctor visit on Friday morning took an unexpected turn when a severe infection was discovered. We were sent to the ER across the street and she was admitted to the hospital for treatment.

My mother made that suggestion on Sunday, as I sat on the bed in her hospital room. A long-awaited doctor visit on Friday morning took an unexpected turn when a severe infection was discovered. We were sent to the ER across the street and she was admitted to the hospital for treatment.

Mom has read all my books. “You were always the smartest one in the family,” she insisted, though I did not agree. My parents always believed I could do anything, even when I didn’t believe it myself. She even knows some of the people in my books, including my friend, Delle Chatman, who inspired me to write in the first place.

It’s been almost 13 years since my father died from cancer and honestly, Mom’s been a little lost that whole time. As the oldest, the decisions about her health fall to me. A lifetime of life-threatening food allergies, along with the great example of my fellow ACT UP members, armed me with the knowledge and tools I need to advocate for her with the medical establishment.

On Monday I butted heads with a vascular surgeon. He expected me to agree to a complicated, potentially dangerous surgical intervention and I said no. The look on his face was, well, priceless. I’m the first to admit I have a hard time dealing with authority figures: politicians, priests, doctors. I wasn’t rude. I just said, “That’s not going to happen.” He was momentarily speechless, certainly not used to anyone – much less a woman of a certain age – disagreeing with him. So I repeated myself. That pretty much ended the conversation. Today, her 89th birthday, I get a second opinion; maybe a third.

The book I’ve been working on for over two years was delayed last year, after I broke my writing hand and lost almost five months to rehabilitation. My revised publication date was the end of March, this year. That’s not going to happen now. Mom comes first, so I will continue to drive up and down I-55 between Chicago and St. Louis as long as necessary to help her.

I have a lot of friends who are memoir writers. I admire them – Kathy Pooler, Madeline Sharples, and others – for the courage they embody by sharing the most painful and powerful aspects of their lives. They are some of the bravest people I know. But, back to my mom’s statement.

I’ve always assumed my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community) would be my last. I will be doing a lot of presentations, public speaking and freelance writing related to the book once it’s released. That will keep me busy for quite some time, along with continued presentations related to the Friend Grief series. I also believe I have one more career left in me, one that’s a hybrid of previous careers (more on that another time).

I may very well write more about this journey with my mother. I don’t know. I’m in the eye of the hurricane right now, so it’s hard to predict the direction. I will do it if – and only if – I believe there’s benefit in sharing any of this experience.

But for now, writing is not at the top of my priority list. As my mother always says, “every day is different”. I hope she’s right.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 21, 2018

“For They Shall Be Comforted”

Beverly Review

Beverly ReviewWhen Ron Howard filmed Backdraft in Chicago in 1991, a call went out for extras. The funeral procession at the end of the movie required a couple hundred firefighters in dress uniforms to march down Michigan Avenue. It’s a powerful scene made more powerful by the inclusion of firefighters from around the area who offered their services. In fact, 5,000 volunteered.

So it was no surprise that when Chicago Police Commander Paul Bauer was killed last week, his wake and funeral were full of men and women in uniform. The six-hour visitation, at Nativity of Our Lord Church, required a three-hour wait in line for those who came to pay their respects. Most of those people didn’t know Bauer personally. They came out of respect for a fellow officer, even if they came from another state. Civilians came out of respect for a neighbor, the parent of their child’s friend, a parishioner. Friends and strangers alike felt compelled to show their respect and grief.

I’ve always been fascinated with rituals. Growing up at a time when the Catholic Church changed drastically after Vatican II, I saw old rituals replaced with new ones. There’s comfort in rituals: you know what to expect and that familiarity can help heal in times of profound grief.

We saw plenty of rituals in Chicago last week: flags at half-staff, black and purple bunting over the police headquarters entrance, candles and flowers in front of the 18th District where he served, condolence books. But many people created their own rituals, their own way of showing support for the family, things Bauer’s widow noticed in the 1,000-vehicle procession to the cemetery that shut down the Dan Ryan Expressway.

“If I wasn’t out of tears, I would have cried the entire route to the cemetery. I want you to know that I saw each and every one of you who stopped on the side of the road to salute as the hearse went by. … I saw people of every color taking time out of their day, not only to pay respects to Paul, but to the entire Chicago Police Department.”

So often when a friend dies we don’t know what to do. We want to comfort the family and other friends, but we have to deal with our own grief, too. We don’t want to impose, but we want to do something tangible, something that helps.

I doubt if the people Erin Bauer mentioned thought they were doing something that would make a difference. They couldn’t go to the cemetery, couldn’t squeeze into the little church for the wake. Other than watch the funeral broadcast live on TV and online, not much was left.

So they stood on the curb on a cold Chicago day, the snow holding off until the procession arrived at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. They held homemade signs, wore blue (as requested of those standing on the route), made the sign of the cross as the vehicles passed.

Like you, I’ve sometimes had the feeling that what I did after a friend died was painfully lacking. I should have done more, though I had no idea what ‘more’ could be. But I think the actions of these people – friends, neighbors, strangers – prove that any gesture, no matter how small, can bring comfort to those who grieve. As one police captain told the Chicago Tribune:

“Whoever did what they can do, the fact that you did it…that is the fuel that is keeping us going.”

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post