Victoria Noe's Blog, page 2

April 1, 2020

My Second Pandemic

wired.com

wired.comI’m not sure what the first trigger was. It might have been a picture like this one, medical personnel dressed in ‘space suits’ to remain safe from their patients.

It might have been the word ‘pandemic’.

It might have been ‘only certain people will get this virus, not me’.

It might have been stories of meal deliveries left on porches, or recommendations that counters and doorknobs be wiped down with disinfectants.

It might have been a Republican president indifferent at best to the suffering of those whose lives he did not consider important.

It might have been the blame, the pointing fingers, the demonizing.

It might have been the insistence of many people to carry on their lives as usual, no matter what the consequences of their actions.

At the beginning of March, I thought I was the only person who felt a persistent, nagging sense of déjà vu. The beginning of the AIDS epidemic was almost 40 years ago. The coronavirus pandemic is not the same (a frequent topic of heated discussions on Facebook). But there are enough similarities that those of us who remember those dark days are now experiencing waves of grief and yes, anger.

“Do you think that your experiences in the AIDS community are affecting how you feel now?” my therapist asked last week. My first reaction was “Well, duh.” But since then, that question has been guiding me, for better or worse.

One of the lingering behaviors from that period of time is that if I don’t hear from a friend for a while, I assume something terrible has happened to them. Maybe not dead, but something really bad. It certainly comes from that time when people often disappeared, their names surfacing only when you saw their obituary in the weekly LGBT paper. People died quickly then. The speed at which they died was stunning, though they were lucky. Others lingered for months, in and out of hospitals where they were treated like lepers, sometimes dying alone.

Last week I started contacting all the friends I hadn’t heard from lately. A series of emails, texts, phone calls, Facebook messages assured me that all were alive and mostly well. Many of them have conditions that put them at risk if they contract the coronavirus. The friends in New York worried me the most, but I was relieved to hear back from all but one. That one I’m still worried about.

I told my therapist that I expect that someone I know will die from this virus, maybe more than one someone. It might be someone who’s already at risk. It might be someone who was otherwise healthy. That kind of surprise is what I fear the most.

It’s easy to be on edge these days. Our world is full of unknowns, even more so than usual. Our routines have been upended, our finances shaky at best. We all know people who have lost their jobs, maybe their businesses, too.

The whole world is grieving for the losses that mount each day along with the bodies. And as much as we try to pull together – and we have – it would be a mistake to ignore the sense of loss we feel.

My therapist asked what I do when I’m triggered, now an everyday occurrence. I told her that I stop what I’m doing when I have these moments, these flashbacks. For too many years, I pushed those thoughts aside, buried them deep inside me so that when they finally came out, I was overwhelmed. Now I acknowledge them and take a moment to remember that terrible time when my friends were dying and damn few people cared. And then I shift gears. I do something else, go for a walk, do the laundry, post links to resources that my friends can use: anything that feels productive. The moment passes, but it’s not ignored, because I learned the hard way that ignoring isn’t healthy.

I see a lot of my friends, long term survivors in the AIDS community, who are similarly triggered. They were the ones I reached out to first. I can’t tell them how to deal with this because we all face grief and trauma in our way. But I hope they know I understand, that I’m willing to listen and help in whatever way I can.

When this is all over – and it will be someday – we will gather again to hug and kiss and dance. We’ll marvel at how we survived not one but two pandemics. And then we’ll dance some more.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 19, 2020

Still Connected, Even if Not Physically

March 13, 2020, 7pm, 5th Ave & 86th St., NYC

March 13, 2020, 7pm, 5th Ave & 86th St., NYCLike most people, my life has turned upside down this month.

Last week I was in New York, for what would turn out to be a five-day visit instead of a three-week trip to four cities. I’d been there less than 48 hours when the emails started popping up: cancellations and rescheduling. The one event that wasn’t cancelled was drastically downsized. My hotel was emptying quickly, crowds were disappearing. Everyone was scared. What would have been a busy and lucrative month was now a financial disaster. Fear of the unknown – and so much is unknown about COVID-19 – overwhelmed every other consideration.

Still, I remained oddly calm. All of this – every bit – is out of my control. There’s nothing I can do to change or fix things. My daughter moved to Daegu the day the announcement went out that it was the epicenter of the epidemic in South Korea (she’s fine – more than fine). A number of my friends live in retirement communities and are on lockdown. I have to remind myself that I’m in a high-risk group by virtue of my age. That’s a sobering thought.

So, what to do? I lowered the price of the Fag Hags, Divas and Moms ebook on Amazon. I took an unusually empty Amtrak back to Chicago, unpacked and did some paperwork. Started spring cleaning. Booked an event for late April (fingers crossed). Almost everything cancelled in March can be rescheduled; that helps. Signed up for webinars and online events that I would not have been able to do if my trip had continued as planned. Then something sweet and unexpected happened.

Long ago, I set up Google Alerts for topics related to my books and for my name. A couple days ago I got an alert attached to my name: an article in the University of Sydney (Australia) student newspaper about my book. You can read it here. You never know how far your book reaches, so this was a delightful surprise. I emailed the editors, asking them to thank the writer. They responded and put us in touch. This is part of what he wrote to me:

Your book is an important contribution to the history of the pandemic. I always suspected that women played a forgotten role in the pandemic – it was your book that gave me the specific stories that confirmed this for me and I just knew I needed to get out my feelings on the matter.

As a gay man today, it is my women friends who are my biggest allies and I hope that I can be just as much of an ally to them.

So many of us are physically isolated right now, and that isolation has driven home just how necessary our connections are to our well-being. I suspect – and hope – that those are connections we are unlikely to take for granted ever again.

We can still make phone calls and even – GASP! – send cards or letters. And we have this little thing called ‘the internet’. That means we can FaceTime and Skype and Zoom. We can email and text and tweet. We can connect with others, even those half a world away, in seconds. Though Aiden’s email did not solve any of my problems, it made me forget about them.

So, instead of obsessing about the news, reach out to those who are isolated. Reach out if you’re isolated. Do it every day. Maintain those relationships and build a new community. They will be stronger and happier for it.

And so will you.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 1, 2020

Why Women’s History Month is Like A Treasure Hunt

I have a friend who posts the same thing on Facebook every morning: “Today is National X Day. Please celebrate responsibly.” He shares commemorations that are sometimes important, often obscure, frequently funny. I look forward to them because they start my day with a smile and a new bit of – sometimes useless – knowledge.

I have a friend who posts the same thing on Facebook every morning: “Today is National X Day. Please celebrate responsibly.” He shares commemorations that are sometimes important, often obscure, frequently funny. I look forward to them because they start my day with a smile and a new bit of – sometimes useless – knowledge.

Women’s History Month is like that, too. Just like February’s Black History Month, every day in March brings stories that are new to many and endlessly fascinating. Uncovering those jewels is critical to our understanding of the world.

This year marks the centennial of the 19th amendment, which finally gave women the right to vote. One hundred years ago, my grandparents were teenagers and young adults. It wasn’t really that long ago. And though that is an important landmark to celebrate, there are countless stories out there that were ignored or erased.

Because of that, we’re still honoring ‘firsts’: the first woman to do this, the first woman to do that. Sometimes the accomplishments are happening now. Sometimes they happened decades or centuries ago, but were not recognized until now. The success of books and films like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks or Hidden Figures proves that there are still remarkable stories to uncover.

One of the great joys of the past year for me has been telling the stories of the women in my book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community. A few women in the book, like Princess Diana and Elizabeth Taylor, were already well-known. Others, like Dr. Mathilde Krim, were familiar to those in the AIDS community. But many, if not most of the women in the book, were unknown. Their accomplishments were forgotten or pushed aside or devalued.

When I contacted women to be interviewed, the most common reaction was, “Why? Why would anyone care about what I did?” It took some convincing. In the interest of full disclosure, I didn’t want to include my story in the book for the same reason. But to ignore my own story would be wrong, too, because every story can be important to someone.

Uncovering these stories really did feel like a treasure hunt to me. Once I was in the research room at the New York Public Library and came upon a gem of a story. I had to bite my tongue to not shout “Yes!” It excites me when people – even long-time AIDS activists – tell me they learned a lot from the book.

You can go on a treasure hunt this month, too. Look for events at your library, museum or historical society. Check out your local PBS station, your favorite podcasts and Facebook pages. I promise you you’ll be surprised and enlightened and deeply appreciative of the women whose stories you’ll hear.

Go on that treasure hunt and see what you can find about amazing women who were trailblazers. Their stories will stick with you, and maybe inspire you to be a trailblazer, too.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

January 2, 2020

Why New Year’s Resolutions Are Made to be Broken

insurancejournal.com

insurancejournal.comI have never been a big fan of New Year’s resolutions. They’ve always felt to me like a setup for failure. But something popped into my head this morning that has changed my mind.

I thought about what others have said to me when I was trying to do something that seemed impossible. Their words of encouragement – “You can do it!” – sometimes rang hollow. But their encouragement wasn’t time-limited. They didn’t stop encouraging me if my first attempt fell short.

Whether it was trying to improve my grades, or applying for a grant, that ‘failure’ wasn’t permanent. Maybe my grades fell short that semester. There’s another semester starting soon. Maybe I didn’t get that grant. But I could reapply or submit that proposal to a different funder. If a freelance article was turned down, I could submit it someplace else. Maybe I didn’t meditate today, so I’ll be sure to meditate tomorrow.

But with New Year’s resolutions, it’s one-and-done. You start on January 1 and if you break that resolution once, that’s it. You never try again. Your failure is final.

I don’t know how or why that became the norm. It’s January 2 and I’ve already heard from people lamenting that they’d broken one or more of the resolutions they made yesterday. “That’s it,” they shrug. There’s no indication that they will try again.

There are very few things I’ve accomplished on my first try. I suspect that’s pretty normal. And I think at the beginning of a year, when we are intent on being hopeful and positive, that’s important to remember.

It’s forty days until pitchers and catchers report (not that I’m counting), so I’m going to use a baseball example here. Really good professional, millionaire baseball players can hope to hit .300. That means they fail to get a hit 70% of the time they come up to bat. Even with batting practice before each game, during spring training and off season, they fail more than they succeed. I doubt if most people would willingly choose a profession where their chances of success were that low.

So I’m going to keep those players in mind as I go through this year, a year full of uncertainty and possibilities. I’m going to be more comfortable with failure because failure is inevitable. It just doesn’t have to be a reason to stop us from achieving our dreams.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

November 26, 2019

Recommended Reading for World AIDS Day

Sunday, December 1 is World AIDS Day. This year’s theme is “Ending the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic: Community to Community”. I don’t remember a theme to the first observance in 1988. But this year I thought I’d recommend a few books from a community that isn’t always included in discussions about the epidemic: women.

Sunday, December 1 is World AIDS Day. This year’s theme is “Ending the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic: Community to Community”. I don’t remember a theme to the first observance in 1988. But this year I thought I’d recommend a few books from a community that isn’t always included in discussions about the epidemic: women.

All of these women have written about the epidemic, fiction and nonfiction. Luckily, more women are writing, like Rae Lewis-Thornton, whose memoir, Unprotected, is coming in 2020. In an odd bit of serendipity or karma or fate or timing, five of the seven women mentioned on this page wrote their books from the Chicago area. You’ll be hearing more about that coincidence soon.

For too long, the literature of the epidemic has focused on gay men. But we were/are there, too. And our experiences are very different. I’ve shared the author’s websites rather than any particular sales link. Buy them from your favorite indie bookstore or online. Check them out from your local library and if need be, ask them to order any or all for you.

You’ll be glad you did.

Taking Turns: Stories from HIV Care Unit 371 by MK Czierwiec. A graphic novel about AIDS? Yes, one that incorporates oral histories with MK’s experiences in the AIDS ward at Chicago’s Illinois Masonic Hospital at the height of the epidemic. A unique and important book.

Taking Turns: Stories from HIV Care Unit 371 by MK Czierwiec. A graphic novel about AIDS? Yes, one that incorporates oral histories with MK’s experiences in the AIDS ward at Chicago’s Illinois Masonic Hospital at the height of the epidemic. A unique and important book.

The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai has won or been a finalist for every major literary award in the past year for good reason. Her epic novel moves seamlessly from the north side of Chicago in 1985 to Paris in 2015, painting a beautiful and painful portrait of the epidemic that is all too familiar to many of us.

The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai has won or been a finalist for every major literary award in the past year for good reason. Her epic novel moves seamlessly from the north side of Chicago in 1985 to Paris in 2015, painting a beautiful and painful portrait of the epidemic that is all too familiar to many of us.

Nowhere Else I Want to Be by Carol D. Marsh is a memoir that focuses on her work founding and running a housing program for women with HIV in Washington, DC. It shines a light on important issues of race and class that are often ignored.

Nowhere Else I Want to Be by Carol D. Marsh is a memoir that focuses on her work founding and running a housing program for women with HIV in Washington, DC. It shines a light on important issues of race and class that are often ignored.

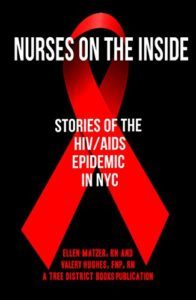

Nurses on the Inside: Stories of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in NYC by Ellen Matzer and Valery Hughes is another first-person account of nurses on the front lines in a city ravaged by HIV/AIDS. Their stories are emotional and riveting.

Nurses on the Inside: Stories of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in NYC by Ellen Matzer and Valery Hughes is another first-person account of nurses on the front lines in a city ravaged by HIV/AIDS. Their stories are emotional and riveting.

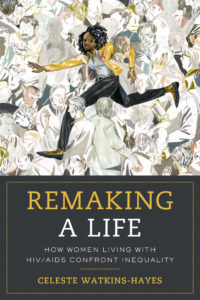

Remaking A Life: How Women with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality by Celeste Watkins-Hayes shares the stories of women of color thriving with HIV. Yes, thriving. But the journey each took to that point is one few of us can imagine. Exhaustively researched, it’s a critically important book on the issues confronting women of color.

Remaking A Life: How Women with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality by Celeste Watkins-Hayes shares the stories of women of color thriving with HIV. Yes, thriving. But the journey each took to that point is one few of us can imagine. Exhaustively researched, it’s a critically important book on the issues confronting women of color.

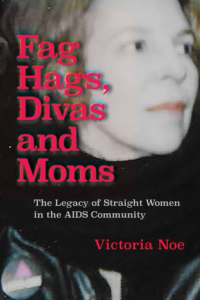

And don’t forget about mine – Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community – which honors the women who changed the course of the epidemic and still make a difference every day.

And don’t forget about mine – Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community – which honors the women who changed the course of the epidemic and still make a difference every day.

So spend some money on Black Friday – or better yet, Small Business Saturday – and learn something new about an epidemic that has raged for almost forty years.

(Full disclosure: Rae and Carol are both in my book, as well as a character from Rebecca’s.)

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

November 1, 2019

Remembering Absent Friends

It’s that time of year. The time of year when death and grief seem to be everywhere.

It’s that time of year. The time of year when death and grief seem to be everywhere.

Yesterday was Halloween, when children and adults dress in costume, many as ghosts and skeletons. We sit in cemeteries at night, waiting for ghostly apparitions, or maybe just the Great Pumpkin.

Today is All Saints’ Day, when we remember the saints and their importance in church tradition.

Tomorrow is All Souls’ Day, when we reflect on the lives of those we loved.

Day of the Dead.

Guy Fawkes Day.

Lots of loss for one week, isn’t it?

Once again, I’m sharing information on a unique festival taking place the first week of November in Scotland: To Absent Friends.

Scotland has a tradition of storytelling, especially at this time of the year. And though it had become somewhat out of fashion, a group of people decided it was time to revive both storytelling and remembrance. To Absent Friends runs from Nov. 1-7 around Scotland, and the festival includes an impressive array of events, including:

A primary school in Bathgate is dedicating a storytelling chair, where children can sit and talk about a loved one who has died.

Wigtown is hosting a variety of creative writing events.

In Glasgow, they are continuing the tradition of ‘tell it to the bees’, as well as a powerful remembrance of the 47 homeless people who died there in 2018.

There are brunches and afternoon teas, memorial walks and art projects, receptions and concerts – all being held in Scotland the first week of November.

Grief, of course, does not respect the calendar. Losses happen every day. But maybe it’s a good thing for people to come together at a specific time of year to remember those absent friends. For me, this year, it’s a longer list:

My dearest friend since we met in college in 1973, David Beckwith, who died in September.

Another college classmate, David Aurand, whose panel from the AIDS Quilt I saw for the first time, just a few days before our friend David died.

The irreplaceable Delle Chatman, who died in November, 2006, whose belief in me pushed me to a writing career.

There are others, many others, I could list. Your list is long, too, as the Chicago Tribune’s Mary Schmich acknowledged today.

And it sucks. Sorry, but it does. The list gets longer as you age, but again, grief does not respect the calendar. You can lose many friends when you’re young, as military veterans and HIV long-term survivors can confirm.

But if I learned anything in writing the Friend Grief books, it’s that those friends stay with you. Their spirit, their memory, their influence all continue to guide you long after they’re gone.

Because though those friends may be absent physically, they are always with you. Always.

And that’s something to celebrate.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

October 10, 2019

When Friend Grief Hits Home

There have been a lot of important stories in the news lately. So it was easy to miss a small story in late July.

There have been a lot of important stories in the news lately. So it was easy to miss a small story in late July.

Betsy Ebeling was a suburban Chicago woman whose death was noted because of who her best friend was: Hillary Rodham Clinton. Though the obituary made clear that she was loved and admired by everyone who met her, the friendship that began in 6th grade was the one that defined her in the public eye.

A few hours after this story broke, while I was making dinner, my phone chimed with an incoming text message. It was from one of my oldest and dearest friends. The text was about his health and was not good news.

The details are not ones that I would share publicly, and though I assured him with a rational response that he had no need to panic, inside I was crying. He was not my best friend, but one of a small group of very close friends.

I was in high school the first time a friend died, killed a week after he landed in Vietnam. There have been many more since then: classmates, my parents’ friends, people I worked with, neighbors, parents of my daughter’s friends. It doesn’t get easier. It shouldn’t.

Some of my closest friends – at my insistence – keep me up to date on their health. That insistence was rooted in my experiences in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Those were the days when every issue of the weekly LGBT newspaper contained the shocking announcement of someone’s death. It was often someone you didn’t know was sick, only that you hadn’t seen them for a while. Even now, if I lose touch with a friend I assume they’re dead or dying. Paranoia strikes deep, as Stephen Stills sang so long ago.

The friend whose text interrupted my dinner preparations died three weeks ago. During those intervening weeks, we spoke and texted even more often than usual. The news he’d shared was serious, but not life-threatening. He was preparing for a surgical procedure that would dramatically improve his quality of life, but it never happened. David died rather suddenly and I was not prepared.

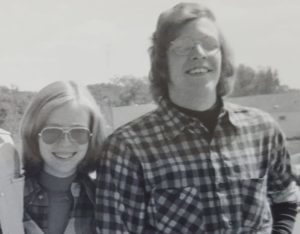

My grief has gutted me in a way that I haven’t experienced since the death of my parents. A 46-year friendship – a complicated, sometimes infuriating, but often fun friendship – cannot be easily forgotten. The photo is us in 1974, the year after we met, when we were both dancing in a U of Iowa production of Fiddler on the Roof. As I sometimes joked, we’d been friends since Nixon was president. A long time. Just not long enough.

I’m bracing myself for his memorial service in two weeks. And though there are questions that will probably never be answered, I am grateful for one thing: there was nothing important left unsaid. We told each other “I love you” at the end of every phone call and most text conversations. We acknowledged how important we were to each other, though he was more vocal than I was. At least I don’t feel guilty about not telling him.

If you too are blessed with friends who make your life meaningful, the thought of losing them is probably something you avoid. That kind of loss can change your life, as so many of the people I interviewed for my Friend Grief books proved.

So, what to do? Maybe you should just do what James Taylor sang: “shower the people you love with love”.

Tell them.

Show them.

Treasure them.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

October 4, 2019

Finding Grace on a Metro Platform

It’s been quite a while since I blogged. The absence was not intentional. Two weeks of travel, the death of one of my dearest friends, and severe bronchitis have brought my daily life to a screeching halt. But in the midst of so much stress, there have been some wonderful moments. None as wonderful as this:

It’s been quite a while since I blogged. The absence was not intentional. Two weeks of travel, the death of one of my dearest friends, and severe bronchitis have brought my daily life to a screeching halt. But in the midst of so much stress, there have been some wonderful moments. None as wonderful as this:

I spent the weekend after Labor Day in Washington, DC at the US Conference on AIDS. There was a lot of focus on long-term survivors, as well as how to serve the unique needs of those aging with HIV. As usual, it was an intense 3-½ days, which this year included a book signing in the A&U Magazine booth for the book I’d first started working on at that conference in 2015 (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community).

My mind was a little – more than a little – foggy as I waited for my Metro train to Union Station so I could go up to NYC for a few days. I set my backpack on the platform next to my suitcase. It wasn’t until I made that connection and was about to get off at Union Station that I realized I’d left the backpack behind.

Panic does not fully describe how I felt. The backpack contained my netbook, financial records, my spare Epipen, medication and all my charging cords. As the sympathetic station master called around to find out if anyone had turned it in, I mentally calculated what it would cost me to replace it all (trust me, you don’t want to know). In all the excitement and noise in the station, I didn’t realize I’d gotten a phone call. There was a voicemail: a woman had found my backpack. I called her immediately. She was no longer where I’d left it. She’d traveled on and didn’t have enough money on her card to come all the way to Union Station. Could I meet her?

Of course the answer was yes, but I admit to being more than a little wary. I let my husband know what I was doing, and sent a message to myself to document my destination.

It took a bit to get there, the second to last station on the green line. But when I came down the escalator, I saw her waving my backpack to get my attention. She could not have been more gracious. I opened up the bag to do a cursory check: not that I assumed she’d taken anything, but it was possible she wasn’t the first person to open it.

“There was a time,” she admitted, as I handed her $40, “that I would’ve tried to sell everything in there. But I’m not that person anymore. And I wanted to meet you.” I was confused. I knew my business cards were in the bag; that was how she’d found my phone number. “I’m HIV-positive.”

I gasped: my nametag from the conference was in the backpack.

“Are you getting services? Are you okay?” I asked when I found my voice.

“One pill a day,” she smiled. “I feel good.”

We parted with a hug, and I got to Union Station in time to make my connection. I’d been more than annoyed when I made my reservation for the Northeast Regional: earlier trains were booked up, so I was taking a later train than was my habit. Had I left the conference earlier I may not have left my backpack on the platform. I certainly would never have met Chris.

At that 2015 conference, on the last day at the closing gospel brunch, one of the ministers said something that I’ve never forgotten:

“Sometimes you choose your calling and sometimes your calling chooses you.”

The unexpected meeting at the Metro station reminded me once again that he was right. And that you can find grace in unexpected places.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

July 12, 2019

Book Review – Nurses on the Inside

“Not everyone knows what you know.”

“Not everyone knows what you know.”

That has been a mantra of mine for many years. It has served me well in public speaking, in interviews and in my writing. Nurses on the Inside: Stories of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in NYC by Ellen Matzer and Valery Hughes is a great example of why it’s so important to share what we know with those who don’t.

Things we take for granted today like case management and universal precautions were unheard of before the AIDS epidemic became publicly known in 1981. One of the great strengths of this book is documenting how treatment changed, so that the reader can fully understand the evolution of critical care nursing when confronting this frightening new virus.

They pull no punches, describing the condition of their patients in cringe-worthy detail. Nursing is a dirty business in some ways, so the horrors Valery and Ellen’s patients endured will shock many readers. That’s okay. You should be shocked. But you can’t help but admire the dedication and love those patients received, often at great emotional cost to the nurses.

There were patients who begged for anything that might prolong their lives, and those who were desperate to end their suffering. Patients who’d been disowned by their families and evicted from their homes. Patients who sometimes had doctors who were indifferent, at best. Patients whose only physical contact with someone who didn’t hate or fear them was from the nurses in the AIDS ward.

It’s obvious that those patients – and the people who rejected them, both inside and outside of the medical community – have stayed with Valery and Ellen all this time: David, the young British man who Ellen and her husband welcomed into their home for a time until he could get back on his feet; Joyce, the woman whose husband didn’t want her to come home again because she was ‘tainted’; Linda, the 19 year old girl who had never been kissed and the orderly who granted her wish before she died.

These are first-person accounts, a memoir about compassionate nursing, that will be familiar to those who remember the early days of the epidemic. For those who know little, it will be a shocking, haunting eye-opener. Don’t let the medical jargon throw you: though it can be overwhelming at times, it’s explained clearly.

I had the pleasure of meeting with Ellen and Valery (and her wife, Mary) recently. And I can confirm that the passion they share for the important work they did is clear on every page of this book. You may be surprised, you may be saddened by what you read. But you will come away with a newfound respect for the nurses who were – and continue to be – such a critical part of the AIDS community.

Order your copy of Nurses on the Inside from Amazon.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

July 5, 2019

Friend Grief and Pride

This year was a special one: the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Some call it a riot, though there’s some debate about whether the resistance to yet another police raid at the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969 fit that definition. But it was momentous.

This year was a special one: the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Some call it a riot, though there’s some debate about whether the resistance to yet another police raid at the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969 fit that definition. But it was momentous.

It was a time when being arrested in a raid at a gay bar meant not only legal hassles, but the likely prospect of your name being reported in the local paper the following day. And since you were most certainly closeted at the time, that publicity could get you fired, evicted or worse.

The LGBT community has come a long way, so there was a lot to celebrate at Pride parades around the world last month. But there was a persistent and vocal group of activists who insisted that Pride – particularly this year – return to its activist roots. That’s why there were two parades in NYC on Sunday: the very corporate, unwieldy, 12-hour long Heritage of Pride parade, and the Reclaim Pride parade that drew 45,000 people, focusing on activism.

Nothing gained by the LGBT community – in fact, by any community – was passively acquired. Advances in civil liberties were hard-fought over years, if not decades, by groups like Queer Liberation Front that demanded equality and ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), that continue to fight for an end to the epidemic.

Pride was bittersweet this year for those of us in ACT UP/NY who worked with Andy Velez. Andy’s death this spring hit hard, and his absence was deeply felt. But so were the other absences: the men and women, LGBT and straight, killed by a frightening virus that was first reported on in the NY Times on July 3, 1981.

Gays Against Guns, founded in response to the 2016 massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, marched with photos of members of the LGBT community around the US who were targets of hate crimes.

So the celebrations were tempered with resolve, anger and grief. Sometimes we lose sight of how much we are affected by grief. Many of those who remember the dark early days of the epidemic are only now coming to grips with the effects of losing dozens or even hundreds of friends.

That kind of grief can cause you to self-isolate or self-medicate. It can plunge you into a deep depression that feels all too normal. And it can sap your desire to keep fighting.

So it was with great relief that I learned of activist/author Larry Kramer’s speech at Reclaim Pride. Larry has always been a controversial figure in the AIDS activism community, but he has never wavered in his call to others to get off their asses to end the epidemic and fight for their rights. He knows the unbearable grief that many carry with them. He knows that complacency is dangerous, that silence equals death.

Maybe it’s inevitable that grief and Pride are connected. Maybe it will always be that way. But for Larry, there’s a way to make it a true celebration again:

As much as I love being gay and I love gay people, I’m not proud of us right now. I desperately want to feel full of pride again.

Please give me something to be proud of again. Please — all of you — do your duty of opposition in these dark and dangerous days.

Do your duty, so that one day Pride will no longer be about grief.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post