Sarah Maddox's Blog, page 23

October 17, 2014

Embedded help at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

This is Dave Gash‘s second session at the conference! It’s called “Embedded help: nuts and bolts”. The aim was to show us how to do embedded help, rather than why embedded help is a good thing. Dave said there’ve been plenty of presentations in years gone by, explaining when embedded help is required and what it looks like.

The goals is to show us two ways to add embedded help to your web app:

Put the snippets into an HTML help page

Put the snippets into an XML file

Dave explained that his code samples are plain old JavaScript rather than using a library like jQuery, because it’s more accessible to everyone and because it will work locally.

First method: Adding embedded help via HTML

For the purposes of this demo, Dave has created a “phony” web app: GalaxyDVR (HTML). Notes:

Look at the embedded help panel at the bottom.

remember Dave’s warning that the aim is to show us how to create embedded help, not how to make it beautiful.

See how the content of the bottom panel changes when you click on different parts of the screen.

Click the link in the panel to see the full help system.

Note how the first sentences in each section of the full help system correspond to what appears in the panel on the app.

Dave said that this is the more difficult than using DITA, but still very feasible. It works by using a CSS class of “shortdesc”. The web app reads the entire content page and looks for the paragraph that has the class of “shortdesc” and sticks it into the that defines the help panel.

How to prepare the content: Create it with any tool that allows you to define a specific reachable HTML element. It doesn’t have to be a CSS style. It could be a with an id, for example. You could even style it so that it doesn’t appear in the full help system.

Dave was using DITA for content storage, which was then transformed to HTML that contained the necessary identifiers. But he emphasised that you don’t need to use DITA. You can have straight HTML instead.

The help files must be accessible to the web app.

How to retrieve the help content when the user clicks the relevant area of the page: A JavaScript function reads the entire HTML file as a string, finds the content identified as embedded help, extracts it to another string, and embeds it into the panel.

Now Dave walked us through the code that does the work. I haven’t tried to capture this in the notes. Some extra bits to note: The page loads some default help content via the HTML body’s onload event. Another piece of code tacked on the standard string that says “For more information, see the full help system“. And remember to add CSS to style the embedded help content.

Second method: Adding embedded help via XML

See the demo app: GalaxyDVR (XML). This one is based on XML. Note also that there’s a specific piece of embedded help for each control on the page, rather than for just the sections. There’s also help for each element of a dropdown.

Dave says this version is much simpler. You don’t need a web help system. Create the embedded help all in one file. You can use any XML text editor. The XML can be of a format of your own choice. The input and output is just a file. There’s no build or conversion process required.

Every embedded help snippet has an id, which is a unique identifier. You can use any naming convention you like. For example:

My help text

More help text

When the user selects a control, the JavaScript looks in the XML file, locates a specific piece of text that matches the control, and returns the help text into the box on the screen. How does it identify the relevant text? The element that the user clicks has an id that matches the id of the help text element. The XML file is read into an XML document object (rather than as a string). Then you identify the help text, extract it, and embed it into the help panel.

Note: Instead of using the onclick event to trap the user’s action, you’ll need to use onblur. Otherwise you’re overriding the core app functionality by usurping the onclick event. Also, people may want help before they actually click the button. Using onfocus will work when users tab through the fields too.

Comparing the two methods

Dave emphasised that neither method is better. Think about what you want to do:

The HTML method creates the entire web help system including the embedded help content. That’s single sourcing. Also, the HTML method less granular, and distributes the embedded help content amongst the other content. You need an entire separate help system, including some kind of build system to create the web help system.

The XML method is not single sourced. You may end up with a set of embedded help content and a separate set of web help content. But this may not really hurt you. You just need to ensure you maintain both. The XML method is more granular, and it keeps all the embedded help content together. You’re not required to have an entire web help system.

Dave also noted that his implementation is just an example. Take his code and change it to suit your requirements. The goals of Dave’s presentation are to show what’s possible and help us feel we can do it.

Conclusion

This was an excellent walkthrough of a couple of embedded help solutions. Thanks Dave for a couple of great demos!

Videos and screencasts in technical communication at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

Charles Cave presented a session titled, “Don’t tell me – show me!” It’s about videos and how they can be used in technical communication. We all know that in real life, if you can get an expert to show you, that’s the best way to find out how to do something. Note that a video can be very short, even 20 seconds. It doesn’t have to be long, to be effective.

Charles told us a story of how he needed to solve a plumbing problem at home. He looked around for instructions, but didn’t find any. Then he looked on YouTube, and found 2 videos. One was very short and simple, illustrating how to replace a filter in a toilet cistern. The other was longer, and presented a large amount of technical information effectively. This works well for something as simple and tactile as plumbing.

In technical communication, we can use a screencast with some sort of narration to show someone interacting with a computer. Charles told a story of how he tried to explain to a friend how to use a website:the Stanton Library website. He started explaining, but decided this wasn’t an effective method.

Our options for showing someone how to do something:

A textual description of the steps

Screenshots with annotations and callouts

Video with voice-over

Video with voice-over and callouts

Here Charles played a video he had created, showing the steps you need to take to search the library for new items on the Stanton Library website. This was a straight recording using Camtasia. He usually does a voice-over, using Audacity (open source and free of charge) to edit the audio track. You can remove background noise and do other editing to achieve a reasonably high quality. Before doing the recording, Charles creates a script and makes sure he has all the software ready to go.

With Camtasia, you can add callouts. Charles demonstrated callouts using arrows overlaid on top of the video, shape drawing, and spotlights which make part of the screen dark so that our eyes are directed to the important part of the screen. There’s a lot you can do in Camtasia, with zooming and panning and more.

Captions or subtitles are useful on videos, particularly for those situations where people can’t listen to the sound. For example, if they’re in a noisy place or with other people. Charles used the captions to point out the important steps in the procedure.

Let’s assume you do need screenshots as well as the video. With Camtasia, you can export the current frame as a PNG file. When using screenshots, it’s sometimes difficult to see what’s changed on each screen. And it takes time to write the words that accompany the screenshots. Charles says that producing the video can be quicker, and also more friendly to the user. Adding a friendly narrator adds to the friendliness.

To consider when considering creating a video as opposed to textual instructions:

How effective are the instructions?

How much time and effort will it take to produce the video?

Is the video usable without sound?

Where will the video be watched – PC, Android, iPhone, etc?

What about video format? Charles recommends MP4 as the most universally useful format.

Charles touched on live-action video, such as filming with a smart phone. Nowadays our smart phones have high definition cameras and are useful tools for creating videos. You can get some useful accessories for the phone, such as a tripod. Also consider light defusers, and setting up a little home studio.

With Fuse from Techsmith, you can transfer videos directly from the phone into Camtasia over a WiFi connection.

You can make videos from still images. Charles uses PowerPoint, and saves each title slide as a PNG file, then includes those into his video. Charles showed us a couple of attractive title slides he’d made. You can also take a number of very clear photos of hardware, for example, and use those in a video flow instead of a filmed video.

You can make screencasts from a mobile phone using Reflector from Squirrels. It runs over the WiFi network. When you’ve connected your iPhone, everything on the phone appears on the screen e.g. your Windows computer. Then you can record it using Camtasia.

What you need to product a video:

The producer/director: you

The script: a plan or list of steps

The camera: Camtasia or a smart phone

The sound recording: a microphone and Audacity

The voice: Charles says doing this yourself is a very good option. Getting someone else to be the talent is also an option, but they’ll need training.

Actors, if you need more than one person: You, and perhaps some colleagues

The audience!

Conclusion

Thanks Charles for a great introduction to using videos in technical communication. Charles has put more information in his blog post: Don’t tell me – show me!

Content strategy: getting it and testing it at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

Carol Barnum‘s keynote presentation was titled “Content Strategy: How to get it, how to test it?” Carol introduced content strategy, then shared some work she did with clients that focused on content, showing a success and a failure.

Content strategy

Carol started with the definition of content strategy (CS) from Wikipedia:

Content strategy refers to the planning, development, and management of content—written or in other media. The term is particularly common in web development since the late 1990s. It is recognized as a field in user experience design but also draws interest from adjacent communities such as content management, business analysis, and technical communication.

A definition from the Content Strategy Consortium:

CS is the practice of planning for the creation, delivery and governance of useful, usable content.

The two key points are planning and usability.

Carol gave us a short history of CS, and some reference material and the people involved, showing how new the field is. It’s a good time to get involved! Looking at the authors of the books, they’re mostly technical communicators. Yet somehow, we’re not deeply involved in the core discussions. It’s time for us to take the initiative here in Australia. Carol showed a map showing that the main interest was in the US, followed by Australia, then the UK, Canada and India.

What do content strategists do?

Audit the existing content, figuring out where it resides, when last updated/accessed, what is still relevant, and so on. This provides a high-level overview of the content.

Plan for the creation, publication and governance of useful, usable content. How you’re going to update, remove and create content.

Manage the content creation and revision.

Create content.

We may be currently engaged in the last activity. To move up the ladder, add the earlier steps to what you do. This will help to prove our worth and become more valuable to our organisation.

Ensuring your content is useful and usable

Be there to see where the users struggle. Especially when there’s no help or user assistance yet, this will help guide the content creation.

Top findings in usability testing: People can’t find what they’re looking for. They get stuck navigating around the site. They don’t understand the terminology, or there’s inconsistency in the use of words. The page design is confusing or not accessible. The design of the interface doesn’t match the users’ mental model. The users bring expectations based on previous experience, and a good user experience (UX) design will tie into these expectations.

What about the content specifically? Users need to be able to find the content. Next, they need to understand it and be motivated to take action. And they need to be able to complete the action satisfactorily. Were they happy or frustrated at the end of the process?

Carol talked through a list of techniques on making your content work for users.

Case study: Green Engage

Green Engage is a web app produced by Intercontinental Hotels Group for general managers of their hotels around the world. The app allows the managers to create plans and track progress of projects aiming to make the hotels green, that is, environmentally friendly.

The app is content based. Carol’s team did a round of usability testing with 14 users. Carol recommends a group size of 10-15 people (so, a small group) of people who are deeply engaged in the subject. The customer’s requirements were to test navigation and workflow, defects and system feedback issues, perceptions around content, and training requirements. Carol emphasised specifically the term “perceptions” in this list of requirements, which came from the customer. Carol thought there were problems with this list of requirements, but went with it.

The first round of testing showed that users liked the idea of the system, but found it hard to understand. There was no user assistance at this time. Of the 14 users, 4 people called for help – they called 11 times. In other words, they were good and stuck. The existing content was overwhelming and unhelpful.

Eight months later, round 2 of the usability testing happened after a complete redesign of the system. The system was redesigned, but the content was exactly the same. There were no technical communicators involved. The requirements for the testing were the same, but with a new goal: Measure the SUS (System Usability Scale) score improvements. Carol recommends this scale as an excellent measure. The average score is 68 – you can use this as a benchmark for measuring your own results. The next step is to measure your own benchmark, so that you can raise your own score over time.

The SUS score from round 1 was 54. This is bad, and not surprising. Round 2 had a SUS score of 73.

Five months later was round 3. There were only 4 users in this study, so we need to use caution when drawing conclusions. This study happened during a pre-launch of the system. Users loved the new system, in comparison with the old system. They found the homepage helpful and that the app supported their goals. The SUS score was 94! Don’t pay too much attention to that – it was only 4 users and they were comparing the new system to the bad old one.

Carol’s team suggested another round, using new users as well as existing ones, employ some tech writers to improve the content and add context sensitive help. so round 4 happened one year later, with 16 users including new and returning ones. The focus was on the content, with a goal to find out how well users understand and can act upon the content. The test gave users a specific set of tasks, based on their use of the content and a specific goal to achieve.

Feedback showed that users had a goal (get profit for their hotel) rather than wanting to read content. They wanted a solution, not an idea. On the negative side, users couldn’t find what they wanted. They were confused by the terminology, and there was a lot of content, but not useful and not well organised. The SUS score was 50. Carol says this was fantastic, because it shows they had work to do. It was the first time content creators were involved.

Case study: Footsmart

Footsmart is a website for people who have troubles with their feet. Carol did one usability study of a single template.The study compared the original content (A) with the new (B). Users would see one or the other, and did not know which they were seeing. The goals were to verity that the new content (A) was effectively communicating with users, to understand how users responded to the content (e.g. it’s voice and tone) and to see if they acted upon it.

Carol showed us examples of A and B. The new content was better laid out, and included graphics.

All 6 participants liked the newer content better and found the thing they were looking for more easily (heel cushions). An interesting conclusion from the detailed results is that people asked for more content in the redesigned site (B). In other words, perhaps you should show them a little at first and give the option to find more content for those who want it.

How to start as a content strategist

Plan the content you control. Create an overview of the types of content on the user interface (UI) such as labels, buttons, help text, etc. Think about the tone and treatment of that UI content. Create personas of your users, and collaborate to develop those personas. Create a style guide based on your conclusions from the above steps. And become involved in usability testing yourself, or even run one yourself.

Conclusion

Thanks Carol for a very good introduction to content strategy. The case studies were fun and interesting, and a good illustration of how usability testing fits into an overall content strategy.

October 16, 2014

Repco and DITA at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

Gareth Oakes walked us through a case study of an automotive content management system that he designed and implemented in collaboration with Repco. The content is stored and managed in DITA format, and published on a website.

Overview of the system: Autopedia

Repco supplies automotive parts in Australia and New Zealand, dealing with retailers as well as their workshop division. They were founded in Australia in 1922. The system is called Autopedia, a subscription product for mechanics and workshops. It provides automotive service and diagnostic information for the majority of vehicles on the road in Australia. For example, diagnostic codes, wiring diagrams, procedures for replacing timing belts, and so on.

Autopedia is a replacement for an “encyclopedia” in the form of a CD that was mailed out to the mechanics. The content was written by Repco technical writers. It was becoming more and more difficult to keep up with the number of vehicles, and variations of vehicle, on the road. It was expensive to maintain the content. And customers wanted online content, not CDs.

Designing a solution

Repco came up with a vision for a replacement system, and Gareth’s team worked with them on the technical solution.

A summary of what the solution comprised:

Content (Repco & third party) -> DITA -> DITA CCMS -> HTML -> Web server

(CCMS = Component Content Management System. The team uses the Arbortext Content Manager.)

The team wrote a multiple conversion pipeline, consisting of a set of Java tools, to convert the content into DITA format. A vehicle mapping table related the vehicle models in other countries to the Australian models. At first this required a lot of quality control, but now it’s up and running it doesn’t need so much attention.

Creating and storing the content

All content is stored as a simple DITA topic. The aim was to keep the system simple. Each topic is tagged to indicate which vehicle it applies to. Other semantics are added when required to support the needs of website display. This was done iteratively, as the need arose. For example, in a voltage table you may want certain values to stand out.

Repco content makes up only 1% of the content. Repco now authors all new content in DITA, using Arbortext Editor. Third-party content come from a vendor in the USA, in multiple formats: database, CSV, custom XML, images. The automatic process converts all this to DITA topics, grouping the topics by vehicle applicability. The system then does a diff process and sends only what’s changed to the web.

Delivering the content

All content is converted to HTML and sent to the web server (Umbraco). The vehicle mapping table is used to decide where the content belongs in the navigation structure. Images are hosted on a CDN (Content Delivery Network) hosted by Rackspace. Topics are marked as published or unpublished on the web service, so separating the publication process from the content storage and update process, and allowing the publishing process to respond quickly to customer feedback.

Project timeline

In all, the project took approximately 9 months. The team was reasonably small: approximately 9 people across the various teams at both GPSL (where Gareth works) and Repco.

(Members of the audience at Gareth’s session expressed surprise at and admiration for the short timeframe of this project.)

The initial design sessions with Repco took approximately a month. The other phases included planning sessions with the web team, development of the code and the vehicle mapping table (which took around 6 months), and migration of existing content to DITA. Then following integration of all the components, and testing. Documentation, training and knowledge transfer was important. Then the initial conversion and content upload took a while – more than 200GB. Then came the go live date, and ongoing support.

Results of the launch

The project launched late in 2012. The response from the market was very positive. They achieved their revenue goals and ROI well within the first year. Most existing customers migrated to the new system, and more than 1000 new customers signed up.

A few project notes

DITA was a good solution for this system, using basic topics and a very light layer of specialisation for vehicle tagging. The team may need to add more specialisation in future, based on customer demands for dynamic representations, such as decision tables. A next step may be a live link to parts, so that the parts are ready when you come in to work the next day. The single sourcing aspect is extremely useful. Store the content in one place and be able to output in many formats, such as PDF. The team found DITA easy to work with, as there are many tools available.

You need a level of skill with XML. DITA also very much steers you to author your content as topics, which may not suit every solution. You may also need new tools. And with a laugh, Gareth said that you risk turning into one of those DITA fans who runs around recommending DITA as a solution for everyone else. :)

The huge amount of content caused many delays, which were not entirely expected. The information structure required a number of design changes during development, due to the complexity of vehicle classification. The DITA CCMS required a lot of specific configuration and optimisation to ensure it was performing as required.

Conclusion

Thank you Gareth for an insight into a very interesting project and a cool system.

STE: quirks and limitations at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

Lyneve Rappell spoke about the quirks and limitations of STE (Simplified Technical English).

What is STE (Simplified Technical English)?

It’s a limited and standardised subset of English, used in technical manuals in an attempt to improve the clarity of and comprehensibility of technical writing. See the Wikipedia article. It’s aim is to help the users of the English language understand technical documentation, particularly in international programs which include people whose first language is not English.

The set of rules that you use to write Simplified Technical English is defined in the manual: ASD-STE100. The rules are not static. They are changing, but the aim is to produce a stable base.

One of the aims is to avoid the need for translations, although it also helps with doing translations. (The latter was not the original goal.)

What’s wrong with everyday English?

Lyneve ran through the aspects of English that make it difficult for people to understand in technical manuals. For example, different areas of the world use different variations of English. We use different language on different media. There are complex grammar structures, plentiful synonyms, and more.

Core skills and competencies

Most clients of TechWriter Placement and Services (where Lyneve works) ask for:

Strong collaboration skills, including communication, time management, positivity and adaptability.

The ability to write strong plain language.

Knowledge of tools, especially Microsoft Word.

What do need to know to be able to write in Plain English and in Simplified Technical English? Lyneve compared the principles and rules of the two.

The STE rules are based on a good knowledge of grammar. For example, you need to know what verbs, nouns, participles and adjectives are, and be able to identify the grammatical subject and object of a sentence. For example, “Convert nominalised actions into verbs”. Many Australians don’t know the language of grammar, although they know how to read and write very well. Whereas people coming from non-English-speaking countries have the opposite problem: they know the grammar very well, but can’t necessarily read and understand English.

Thus, using the STE specification requires a high standard of professionalism on the writer’s part. Organisations can choose to train existing staff, install automated an checking system that checks the language (as used by Boeing, for example), and perhaps employ contractors. STE is not in much demand in Australia.

Conclusion

Thanks Lyneve for an authoritative and interesting introduction to STE. I loved the contextual information Lyneve included in this session.

Practical HTML5 and CSS3 for real writers at ASTC (NSW) 2014

I’m attending the annual conference of the Australian Society for Technical Communication (NSW), ASTC (NSW) 2014. These are my session notes from the conference. All credit goes to the presenter, and any mistakes are mine. I’m sharing these notes on my blog, as they may be useful to other technical communicators. Also, I’d like to let others know of the skills and knowledge so generously shared by the presenter.

Dave Gash presented a session on “Practical HTML5 & CSS3 for real writers”. He promised us lots of code, “but nothing you can’t handle”. He also let us know that 11% of Americans think HTML is an STD. :)

HTML5

Dave walked us through the current state of HTML, and HTML5 in particular. HTML5 isn’t a single thing. It’s a set of related things, some of which are supported now and some of which will be supported in future. So, when assessing whether a particular browser supports HTML5, you should look on a feature-by-feature basis.

Many of the HTML5 features are not particularly applicable to technical writing: Audio and video, canvas, geolocation, web workers and web sockets, and more.

For us as technical writers, focusing on content, the semantic structural elements are particularly interesting, such as , , , and so on, that let us add meaningful HTML tags to our content. In HTML4, there were very few semantic tags. We end up using a large number of DIV tags, in series and nested. It’s very hard to discover the meaning in them. You can’t visualise how they’re used. HTML5 goes towards solving this problem.

To decide on the new tags, the W3C sent out bots that mined existing pages on the Web, analysed all the elements that people are using, and created the new tags based on the results.

Note that the HTML5 tags don’t actually do anything. They don’t have any styles attached. You need to add the styling yourself. Elements that describe their content but don’t add style are the essence of structured authoring.

CSS3

CSS3 also has a lot of stuff that’s not particularly useful to technical writers, as well as features that are.

Live demo

Dave walked us through a live demo, changing an existing web page from HTML4 to HTML5 and giving it structure and style. He showed us how to simplify the and elements, and walked us through the conversion of multiple tags to the new semantic HTML5 elements. The resulting code was much easier to understand. Nesting of elements allows for a lot of flexibility.

The CSS on the sample page was fairly non-specific. It had mostly independent classes, which can apply to any element, and there was no obvious relationship between the content and the structure. The CSS class names used mixed case, which is a disaster waiting to happen. Dave changed this so the code was all lower case, and added dependent classes and descendent (contextual) selectors. These two techniques are useful to restrict the style to elements that are within another element, and thus reduce the chance of mistakenly applying styles to the wrong parts of the page.

Dave also showed us the CSS features that allow you to add rounded corners, shadows, drop caps, and link nudging (moving a link slightly on hover) via CSS3 transitions. First, you define a CSS transition on a specific link. Then use a hover pseudo-class to cause the transition to happen when the cursor hovers over the link.

Conclusion

I love Dave’s style. He had us roaring with laughter, which is quite a feat given the technical nature of the content. Thanks Dave!

October 10, 2014

Out of print: “Confluence, Tech Comm Chocolate”

A few months ago, I asked my publisher to take my Confluence wiki book out of print. The book is titled “Confluence, Tech Comm, Chocolate: A wiki as platform extraordinaire for technical communication”. It takes a while for the going-out-of-print process to ripple across all the sources of the book, but by now it seems to have taken effect in most sellers.

Why did we decide to take the book out of print? I’m concerned that it no longer gives the best advice on how to use Confluence for technical documentation. The book appeared early in 2012, and applies to Confluence versions 3.5 to 4.1. While much of the content is still applicable, particularly in broad outline, it’s not up to date with the latest Confluence – now at version 5.6 and still moving fast. I thought about producing an updated edition of the book. But because I don’t use Confluence at the moment, I can’t craft creative solutions for using the wiki for technical documentation.

Why did we decide to take the book out of print? I’m concerned that it no longer gives the best advice on how to use Confluence for technical documentation. The book appeared early in 2012, and applies to Confluence versions 3.5 to 4.1. While much of the content is still applicable, particularly in broad outline, it’s not up to date with the latest Confluence – now at version 5.6 and still moving fast. I thought about producing an updated edition of the book. But because I don’t use Confluence at the moment, I can’t craft creative solutions for using the wiki for technical documentation.

Here are some sources of information, for people who’re looking for advice on using Confluence for technical communication:

If you have a specific question, try posting it on Atlassian Answers, a community forum where plenty of knowledgeable folks hang out.

Some of the Atlassian Experts specialise in using Confluence for technical documentation. The Experts are partner companies who offer services and consultation on the Atlassian products. The company I’ve worked with most closely on the documentation side, is K15t Software. I heartily recommend them for advice and for the add-ons they produce. For example, Scroll Versions adds sophisticated version control to a wiki-based documentation set.

AppFusions is another excellent company that provides Confluence add-ons of interest to technical communicators. For example, if you need to supply internationalised versions of your documentation, take a look at the AppFusions Translations Hub which integrates Confluence with the Lingotek TMS platform.

A big and affectionate thank you to Richard Hamilton at XML Press, the publisher of the book. It’s been a privilege working with him, and a pleasure getting to know him in person.

For more details about the book that was, see the page about my books. If you have any questions, please do add a comment to this post and I’ll answer to the best of my knowledge or point you to another source of information.

September 27, 2014

Want a REST API to play with?

Are you just starting out with REST APIs, or curious what they look like, and want one that’s easy to play with? Have a go at this tutorial I’ve just written for the Google Maps Engine API: Putting your data on a map.

A few things make it easy to play with the API via the tutorial:

You can get started immediately. All you need are a project on the Google APIs Console and a Google Maps Engine account, both of which are freely available. The instructions are in the tutorial.

The API accepts requests via an online interface called the Google APIs Explorer. So, instead of having to send HTTP requests and parse responses via the command line or within a program, you can just use an online form. The APIs Explorer prompts you for the fields and parameters that are required for each API request. I’ve integrated the APIs Explorer into the tutorial, so each step of the tutorial offers a link to the appropriate form in the APIs Explorer.

If you use the APIs Explorer, you can skip the bit about OAuth and client IDs. Yaayyy for a touch of simplicity when first getting to know an API!

The tutorial includes the full HTTP URL and request body for each API request. For those into Java, there are Java code snippets and a downloadable sample app.

After performing each step of the tutorial, you get visual confirmation of results. So, you’ll follow instructions to send a request via the API, then you’ll look at your account in Google Maps Engine online to see what’s changed.

More about Google Maps Engine, its web interface, and the API

Google Maps Engine provides a means to store geographic data in the Cloud, and to superimpose that data on top of the Google base map. Geographic data can be vector or raster. In the tutorial, you’ll use vector data consisting of a set of geographic points (latitudes and longitudes) with the associated information that you want to represent on a map (in this case, population growth statistics).

Google Maps Engine offers a web UI (user interface) where you can upload data and customise your map. It also offers an API (application programming interface), so that you can upload and manipulate your data programmatically. This particular API is a REST API, which means that it accepts requests and sends responses via HTTP. The requests and responses use JSON format to represent and transfer data.

When following the steps in the tutorial, you’ll use the API to do something, such as upload a set of vector data, and then you’ll look at the UI to see the results.

What you’ll have achieved by the end of the tutorial

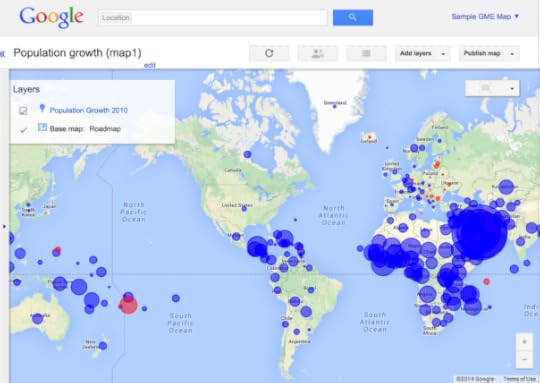

When you’ve finished the tutorial, you’ll have your very own interactive map in Google Maps Engine, looking like the screenshot below. The circles show population growth (blue circles) or decline (red circles) in countries around the world. The size of the circle represents the size of the change:

Let me know if you try it

I’d love to know how you get on with the tutorial, and what you think of the API. Here’s the link again: Tutorial 1: Putting your Data on a Map.

August 27, 2014

How to track textual input with Google Analytics

This week an analytics ninja showed me how to use Google Analytics to track the values entered into a text field. It comes down to sending a dummy page name to Google Analytics, containing the value entered into the field. Google Analytics faithfully records a “page view” for that value, which you can then see in the analytics reports in the same way that you can see any other page view. Magic.

For example, let’s say you have a search box on a documentation page, allowing readers to search a subset of the documentation. It would be nice to track the most popular search terms entered into that field, as an indication of what most readers are interested in. If people are searching for something that is already documented, you might consider restructuring the documentation to give more prominence to that topic. And how about the terms that people enter into the search box without finding a match? The unmatched terms might indicate a gap in the documentation, or even give a clue to functionality that would be a popular addition to the product itself.

It turns out that you can track input values via Google Analytics. The trick is to make a special call to Google Analytics, triggered when the input field loses focus (onblur).

The above ga call sends a customised page view to Google Analytics, passing a made-up page name that you can track separately from the page on which the input field occurs. The made-up page name is a concatenation of a string ('my-page-name?myParam=') plus the value typed into the input field (this.value).

The string my-page-name can contain any value you like. It’s handy to use the title of the page on which the input box occurs, because then you can see all the page views in the same area of Google Analytics.

Similarly, the part that contains the input text can have any structure you like. For example, if the page is called “Overview” and the input field is a search box, the Google Analytics call could look like this:

This blog post assumes you have already set up Google Analytics for your site. See the Google Analytics setup guide. The Google Analytics documentation on page tracking describes the syntax of the above “ga” call, part of “analytics.js”.

August 26, 2014

Follow-up on yesterday’s talk about API technical writing

Yesterday I was privileged and delighted to speak at a meeting of the STC Silicon Valley Chapter in Santa Clara. Thanks so much to Tom Johnson and David Hovey for organising the meeting, and thank you too to all the attendees. It was a lovely experience, with a warm, enthusiastic and inspiring audience. This post includes some links for people who’d like to continue playing with the APIs we saw last night and delving deeper into the world of API documentation.

The presentation is on SlideShare: API Technical Writing: What, Why and How. (Note that last night’s presentation didn’t include slide 51.) The slides include a number of links to further information.

The presentation is a technical writer’s introduction to APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) and to the world of API documentation. I hope it’s useful to writers who’ve had very little exposure to APIs, as well as to those who’ve played with APIs a bit and want to learn about the life of an API technical writer.

Overview

Here’s a summary of the presentation:

Introduction to the role of API technical writer.

Overview of the types of developer products we may be asked to document, including APIs (application programming interfaces), SDKs (software development kits), and other developer frameworks.

What an API is and who uses them.

Examples of APIs that are easy to play with: Flickr, Google Maps JavaScript API

Types of API (including Web APIs like REST or SOAP, and library-based APIs like JavaScript or Java classes).

A day in the life of an API technical writer—what we do, in detail.

Examples of good and popular API documentation.

The components of API documentation.

Useful tools.

How to become an API tech writer—tips on getting started.

Demo of the Flickr API

During the session, I did a live demo of the Flickr API. If you’d like to play with this API yourself, take a look at the Flickr Developer Guide (and later the Flickr API reference documentation). You’ll need a Flickr API key, which is quick and easy to get. Slide 23 in my presentation shows the URL for a simple request to the Flickr API.

Demo of the Google Maps JavaScript API

My second demo showed an interactive Google map, embedded into a web page with just a few lines of HTML, CSS and JavaScript. I used the Google Maps JavaScript API. If you’d like to try it yourself, follow the getting started guide in Google’s documentation. You’re welcome to start by copying my code. It’s on Bitbucket: HelloMaps.HTML. That code is what you’ll find on slide 28 in the presentation.

More links

There are more links to follow in the presentation itself: API Technical Writing: What, Why and How. I hope you enjoy playing with some APIs and learning about the life of an API technical writer!