Sarah Maddox's Blog, page 2

July 31, 2021

Card sorting for user journey analysis and information architecture design

Recently I’ve been using a card sorting tool, part of the Optimal Workshop toolbox, to analyse a set of user journeys. The card sorting tool is also useful for designing an information architecture for a website or documentation set. This post describes how I used the card sorting tool, because it may be useful to other tech writers and information designers. (I’m not affiliated with Optimal Workshop, nor have they asked me to write this post.)

I’m working with a team to design a tool for gathering and presenting documentation metrics. As a first step, we want to know what type of metrics people will find useful, and how they’d like to use those metrics. We decided to start by gathering user journeys. For us in this context, a user journey is a goal that someone wants to meet by following a set of tasks.

After gathering the user journeys, we needed a way to analyse and collate them. Optimal Workshop‘s card sorting tool came in useful here. This post describes how.

Note: The examples in this post come from Optimal Workshop’s demo application. (They’re not from the actual interviews and user journeys that my team is working with.)

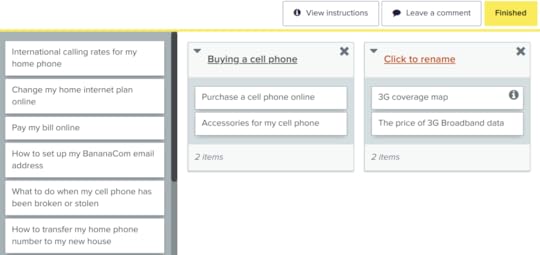

This screenshot shows an example of a card sort, from Optimal Workshop’s demo application:

In the above example, participants in the card sorting exercise can move the cards from the column on the left into the work area on the right. When moving a card, participants can choose to put a card into an existing group, such as “Buying a cell phone”. Or they can create a new group and give it a name.

Context around what I needed to doMy team’s goal was to understand a large set of user journeys that we had collected for a yet-to-be-designed system. Before using the card sorting tool, my team had done the following work:

Interviewed prospective users of the proposed system, asking them a set of open-ended questions about why and how they would use the system.Made notes during the user interviews, using a standard template to ensure that each interviewer captured the same sort of information from each interviewee.Distilled the notes from each interview into one or more user journeys. A user journey encapsulates a single goal expressed by the user. It may take one or more tasks to achieve that goal, but at this point the goal was the important thing.Collected all the user journeys into a single repository. In our case, we used a spreadsheet.After doing all that, we had a large collection of user journeys — too many to work with in the next phase of the project, which is to prioritize the use cases, define requirements for the use cases that we want to tackle first, and design a minimum viable product. Some of the user journeys were duplicates. Some user journeys represented subsets of others. Some user journeys expressed a similar goal, but from a different perspective.

We needed some way of analysing and collating our user journeys. Enter the card sorting exercise!

What is card sorting?Card sorting is an exercise that you can use to see how your customers think about a certain subject area or product. You give people a set of cards, each representing an activity, task, topic, or concept, and you ask them to group (sort) those cards into categories.

I’m using the word customers in a broad sense. The participants of a card sorting exercise can be customers, users of a product, readers of a website, members of a design team, and so on.

As the creator of a card sorting exercise, you can choose whether to give your customers preordained categories (a closed card sort) or to let the participants make up their own categories (an open card sort).

By examining the groupings made by the participants, you get useful insights into the way people think about your subject area or product.

In the past, I’ve participated in card sorting exercises where we used real cards made out of paper or cardboard. Sometimes the cards were Post-it notes. We’d write the topics, tasks, or concepts on the cards and place them on a table or stick them on a whiteboard. Then we’d shuffle the cards into groups, using the exercise as a way of exploring concepts and designs.

It’s quite common to use electronic cards instead of paper ones. That’s what we did for the user journey analysis that I’m describing in this post, using Optimal Workshop.

How we used card sorting to analyse our collected user journeysWe decided it’d be useful for each member of our team to analyse the user journeys individually as a first step. That’d give each of us the freedom to look for patterns and understand the users’ goals, without being influenced by other members of the team. After that, we wanted to analyse and collate our findings.

I loaded all the user journeys from the spreadsheet into Optimal Workshop’s card sorting tool. I created an open card sort, so that each person could make up their own groupings of user journeys. Then each team member spent a couple of hours sorting and grouping the user journeys. You can see what this looks like by trying Optimal Workshop’s demo app, using the participant view.

The next step was to examine what we came up with. Optimal Workshop offers some useful tools in the Analysis tab of the Results section. To try it out, see the results view of their demo app.

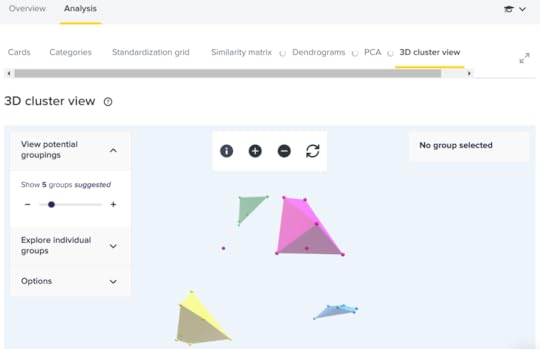

In particular, I found the 3D cluster view interesting and useful. Here’s a screenshot from the Optimal Workshop demo:

The tool analyses the categories created by the participants, and further groups the categories into clusters. This is particularly useful in an open card sort, where participants have created their own categories. It gives you a way of finding similar categories.

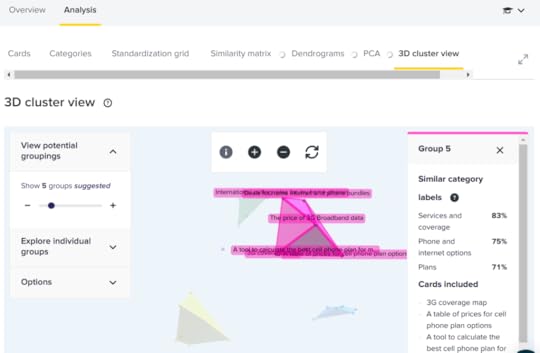

The next screenshot shows the details of one particular cluster, listing first the categories in the cluster, and then the cards in those categories:

We used the sets of “similar category labels” offered by the tool as a starting point to help us combine and reduce the number of user journeys in our collection.

Card sorting for information architecture designIn the situation that I described above, we used card sorting to analyse user journeys. Card sorting is useful in other situations, one of which is designing the information architecture (IA) of a website or a documentation set.

The IA usage is closer to what Optimal workshop’s demo application shows. In case you skipped past the section of this post about user journeys, here are the links again:

You can try out Optimal Workshop’s demo as a participant in the exercise, using the participant view. Or you can try it out as the analyst or designer viewing the results of the card sorting exercise, using the results view.Card sorting is also useful for the members of a team designing the website. Instead of having users do the card sorting exercise, you can have your team do it. This gives each person the freedom to draft designs in peace, play with concepts, and experiment with new groupings. Once everyone has finished, you can get together to see the differences and similarities in the way you’re thinking about the design.

Trying out Optimal WorkshopYou can use Optimal Workshop for free to try it out. See the various options on their pricing page, including “try for free”.

More tips about card sorting or other UX tools?If you’ve used a UX tool as part of your role as technical writer or information designer, I’d love to hear about it.

January 7, 2021

Writing a one-pager to pitch a doc idea

As a technical writer, I’ve sometimes found it useful to write a short document describing an idea or a proposal. The target length for such a document is one page. Hence the name, one-pager. In some situations, a one-pager is a good alternative to a doc plan.

This post is about one-pagers used in the context of technical writing. In other contexts, a one-pager may be a pitch for a company or a student’s summary of a lecture.

Quip: An engineer pointed out that one of my one-pagers was technically a two-pager. (It was actually about one and a third pages long.) I responded that I could fix that by reducing the font size.

January 6, 2021

How to conduct a walkthrough of a doc plan or design doc

In a recent post about writing a doc plan or a design doc, I mentioned that it’s useful to conduct one or more walkthroughs of the doc plan or design doc before sending it out for review. Here are some tips on conducting a walkthrough.

During an in-person walkthrough, you can iron out potential misunderstandings. People can ask you questions, and you can get immediate feedback from people who may not find the time to review the doc in detail.

In other words, a walkthrough can help clear away the cobwebs! I took this photo recently while walking on a bush path.

Inviting people to a walkthrough

The first step is to decide who should attend your walkthrough. If you have the luxury of working with other technical writers, it’s useful to walk through the doc plan with one or more of them first. They’ll point out inconsistencies, missing pieces, and unclear sections for you, and help you crystalise your own understanding of the problem that your design is solving and iron out any wrinkles in the design.

Give yourself time to incorporate feedback from the technical writers before holding the next meeting.

Next up, invite your key stakeholders to another walkthrough. These people should be the ones who can give you input on the problem and on your design. For example, your product manager and the engineers responsible for the area of the system that your documentation will cover.

Schedule at least a full hour for the walkthrough. The time will shoot past once everyone starts discussing the use cases and design.

In the invitation, provide the link to your doc plan, but don’t expect people to read the doc plan before the meeting. Some of them may look at it, but you should assume that no-one has seen it properly.

Running the walkthrough

Your goal for the walkthrough is to ensure that people understand what you mean to convey in the doc plan. Until you’ve run the walkthrough, you can’t be sure that what people will get from reading the doc plan matches what you intended to say.

I’ve found the following format useful for a walkthrough of a doc plan:

Start by explaining purpose of meeting: to give the attendees an overview of the doc plan and the design that it proposes, and to gather preliminary feedback. Let the attendees know that you’ll send the doc plan out for detailed review after the walkthrough.Describe the context of the doc plan: the problem that you’re looking to solve, and the customers who form your target audience.Show the outline (table of contents) of the doc plan, so that your attendees know the scope of the doc.If the doc plan is very long, decide beforehand which sections you’ll walk through in person. Often, the diagrams (user flow and information architecture) are most useful sections to cover in person. Also make sure you cover the timeline for delivery of the documentation.Actively solicit feedback at all stages of the meeting.Make copious notes, either as comments in the doc plan or in a separate document, during the meeting. Do this note taking yourself — don’t rely on others. Your attendees won’t mind your making notes, as it shows that you care about their feedback. Other note takers don’t have the depth of context that you have, and they may miss important items.After you’ve walked through the sections of the doc plan that you intend to cover, make sure you sit back, relax, and give everyone time to think about the bigger picture. Often the most useful feedback comes at this stage, when people know they’ve seen all that you want to show them, and they can think independently.

After the walkthrough

Update the doc plan to incorporate the feedback that you’ve received. If necessary, change your design to match your new understanding.

Finally, send the doc plan out for review, by email or using whatever channel your organisation uses for this type of review. Make sure you send it to all the people who attended your walkthroughs, as well as to other stakeholders and team members.

January 5, 2021

The power of a doc plan or design doc

For a while, I’ve been thinking about the joys and pains of writing documentation plans (doc plans). It takes a long time to write a doc plan and get it approved. It’s time that you could spend writing the real docs — that is, the user guides, developer guides, API guides, and so on, that constitute our bread and butter as technical writers. Are doc plans worth the time we spend on them?

After careful thought, my conclusion is this:

Doc plans are a technical writer’s power tool. We use them to craft a shared understanding between ourselves and our stakeholders. What’s more, as technical writers, we’re well qualified to write an excellent doc plan.

In many cases, a doc plan does more than define the docs that need to be produced. The doc plan fine-tunes the engineering team’s goals for and design of the product itself. Sometimes, indeed, the doc plan represents the first time anyone has attempted to present a coherent picture of the product’s customers and their needs.

Hint: If your reviewers and approvers are primarily engineers, think about referring to your doc plan as a design doc instead of a doc plan. Engineers know the design doc pattern. They know the purpose of a design doc, and how to review it. This familiarity will make them more comfortable when reviewing your doc plan, and could therefore result in more useful and appropriate feedback.

How do you write a doc plan?

The first steps for writing a doc plan are the same as those for any other document:

Define the purpose and audience of the doc.

Before you start, think carefully about your goals. What you want to get out of the doc plan? What do you want your stakeholders to understand and approve?

If you can’t answer these questions, then maybe you don’t need a doc plan at all. Instead, would it be enough to jump straight into the documentation update and rely on the review and approval process for the documentation itself?

Writing a doc plan should be a purposeful and therefore enjoyable part of your tech writing process. You should feel excited about getting a good, clear decision and about honing your understanding of the problem that your documentation will solve. You should also feel excited about explaining your proposed solution to your stakeholders. If the process of writing the doc plan feels like a nuisance, then the process probably needs changing.

Here’s a summary of how to go about writing a doc plan. The process will probably look familiar, because it’s similar to writing other types of documentation:

Define the purpose of and audience for your doc plan. I discussed this in detail in the paragraphs above, and it’s worth repeating here.Gather requirements by reading related docs and specifications.Talk to stakeholders, subject matter experts, and your own team.Scribble diagrams to cultivate your own understanding of the requirements. These diagrams will most likely be user flows that show how people will complete one or more tasks using the product that you’re documenting. Don’t throw these diagrams away! They may be useful in your doc plan.Scribble more diagrams to cultivate your proposed solution. These diagrams will most likely be conceptual illustrations of the information architecture in your documentation site, and user flows showing how people will find and read information in the documentation. Hang on to these diagrams too. They’ll almost certainly be a useful part of your doc plan.Plan the docs that you need, down to the page level, based on the above diagrams. Be aware that the detailed design is likely to change when you start building the docs. At this stage, the page-level detail is useful for estimating the amount of time required to complete the documentation update.Put it all together as a doc plan. The next section has some guidance on what’s in a doc plan.

What’s in a doc plan?

What you put in your doc plan depends on what you want to get out of it. As discussed in the previous section, think about your goals for writing the doc plan. Those goals determine what you’ll include and what you’ll leave out.

Your organization probably has a template or two for doc plans. The internet offers some templates too. I’ve linked to a few templates and examples at the bottom of this post. In my experience, templates are useful as a starting point, but I almost always remove some sections and add others of my own, based on what I need for each particular doc plan.

Here are some useful sections to include in a doc plan:

Title (for example: ProductFoo doc plan, or Doc plan for migration from Foo to Bar)AuthorSummary of the purpose of the doc plan (very short, just one or two sentences)Other metadata:Status (draft, under review, approved, etc)Date createdReviewers and approversOther items that are specific to your environment, such as a short link to the doc plan, your team name, etcIntroduction (context, including a reference to existing documentation if you’re proposing and update to an existing site, the project or product that the documentation applies to, and other background information)Goals and non-goals (a clear description of what you want the documentation updates to achieve, the scope of the documentation updates, and what’s out of scope)Use cases (also known as user flows; diagrams are useful here)Detailed design for each use caseStructure of the documentation site (information architecture; diagrams are useful here)Description of the content required, down to the level of a page (deliverables)Implementation phases and timeline (estimates of when the content will be ready for publication, based on an assumed level of staffing)Measuring the results (metrics, user studies, and other ways of determining the effect of the documentation delivered)Dependencies and related projects

I’ve highlighted in bold the sections where we as tech writers may feel most comfortable and most excited. These are the sections most closely related to the design and creation of the documentation. Yet the other parts of the doc plan are equally important. In fact, they’re key to getting buy-in from our stakeholders.

How comprehensive does the doc plan need to be?

There’s a lot of other information that could go into a doc plan. For example:

Risks, including assessment of potential impact and mitigationA detailed staffing plan (the writer(s) who’ll create the documentation)Alternative designs that you’ve considered and discardedA plan for translation/localisation of the contentA log of updates that you’ve made to the doc plan

My recommendation is:

Include only what you need. If you’re not sure, cut it out.

If you’re starting from a template, remove sections that are not relevant. Keep your doc plan lean and mean. This will make for a faster review and approval process. People will feel happier about giving feedback on and signing off something that they understand. If there’s too much content, much of it irrelevant, people will lose track of, and lose confidence in, the bits that are important.

The resulting design, after you’ve incorporated people’s feedback, will be stronger.

What happens after you’ve drafted your doc plan?

After creating the first draft of the doc plan, the goal is to get other people to look at it and give you feedback. This feedback is essential, as it ensures that your understanding of the requirements is correct, and that the documentation that you’ll build will in fact satisfy the requirements.

I’ve found the following strategies useful:

Walk through the doc plan with another tech writer, if possible.Walk through the doc plan with your stakeholders. I’ve found that an in-person walkthrough is very helpful, rather than immediately sending the doc plan out for review through email or other asynchronous means. During the walkthrough, you can iron out potential misunderstandings. People can ask you questions, and you can get immediate feedback from people who may not find the time to review the doc plan in detail.Incorporate any feedback from the walkthroughs.Send the doc plan out for review. Include the people who attended the in-person walkthroughs and all other relevant stakeholders. Set a deadline for review comments. A week is usually a good amount of time.Incorporate feedback from the review.Send the updated doc plan out again, and let people know you’re asking for approval. Give a deadline for the approval.Prod people until you have the approval you need.

Now you can start the most exciting phase of all: creating or updating the documentation!

Do you need to keep your doc plan up to date after the documentation is published?

After you’ve published the documentation, do you need to ensure that your doc plan stays in line with further updates? The answer depends on the processes in your specific business environment, but in general I’d say no. A doc plan does have value after the updates are done and dusted, as it shows the reason for the update and the overall design. In most situations, however, a doc plan is an artefact of the consultation, design, and review period of the documentation update. There’s no need to continue updating the plan after the documentation is published. The documentation site itself is the source of truth for current information about the documentation design.

Examples

Here are a few examples of doc plans provided by various people or groups:

Sample doc plan and template from TechWhirl.Doc plan from Tom Johnson at I’d Rather Be Writing.

Any more?

Do you have any examples of, or templates for, doc plans?

January 4, 2021

Online class on technical writing principles

Google has published a few technical writing classes, which are available for people to attend and/or teach. I’ll be running one of the classes next week, at a time that’s convenient for the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region. If you’re an engineer or software developer who wants to improve your technical writing skills, then this course is designed for you. The course is also useful for technical writers and others who want to brush up their tech writing skills and/or tech the class at a future date.

The dates and times of all upcoming classes are published on the Google Developers Technical Writing site. The classes are run by various people, including Googlers and others.

Here are the details of the class that I’m running:

Class title: Technical Writing One

Date: Tuesday, January 12, 2021

Time: 8:30am – 11:00am IST (India Standard Time: UTC +5.30)

11:00am – 13:30pm SGT (Singapore Time: UTC +8)

14:00pm – 16:30pm AEDT (Australian Eastern Daylight Time: UTC +11)

Meeting link: Click to join class

Class format: Instructor led, online, free of charge. Participants work with partners (online) on the class exercises.

Prework: Read the pre-class material.

The Tech Writing One course was developed by technical writers at Google to train engineers and others in the principles of effective technical writing. It’s fun and interactive. The combination of pre-class reading followed by in-class exercises and discussions works well to help the participants retain what they’ve learned.

To join the class, click the above link at the time of the class. I hope to see you there! If you’d like to let me know you’re coming, feel free to add a comment to this blog post.

November 13, 2020

Soothing Musings: A new way of communicating

Soothing Musings with Sarah is a new way of communicating for me. Using a blend of beauty, information, and story-telling, my goal is to share a sense of calm in a few short minutes. This post describes where the idea came from and introduces the latest musing, called The Humble Mushroom. I hope you enjoy the post and the musing.

It all started from a realisation that walking in the Australian bush is, for me, a very soothing experience. I see the creatures carrying on their lives, short though those lives may be, as if there’s no need to worry about tomorrow. Birds and reptiles and animals, wild and beautiful, go about their business around me, accepting me as part of their world.

Every little sound is an indication of life. It’s a possum nibbling a leaf, or a parrot gnawing at a seed pod, or a branch rubbing against a tree trunk. Swamp wallabies bound-pound away then turn to examine me, ears and paws raised. An echidna hides its nose under a bush, convinced I can’t see the rest of its body, then peers out when I’ve been quiet for a couple of minutes and bumbles over to investigate my feet. A lace monitor lizard, longer than I am tall, waddles across my path then climbs a tree, tasting the air with flickering tongue.

In the early morning, all the creatures are out and about. In the middle of the hot day, the bush is quiet while everyone rests. When rain threatens, the cockatoos scold the universe with glee. Day turns to night, ushering in the Tawny Frogmouths and the shy bandicoots.

Life goes on. For me, it’s the comfort of the inevitable.

I wanted to find a way to capture and share the feeling of calm that I get as soon as I walk onto a bush path. One day, someone asked me to put together a lightning talk. on a topic of my choice. I thought, perhaps I could do a talk that was short on words and high in atmosphere. A soupçon of information, some beautiful images, and a ton of calm.

And thus Soothing Musings with Sarah was born. By design, each musing is just a few minutes long.

The humble mushroom, with music by Philip Horwitz

Now, I’m delighted to share the latest musing, The humble mushroom. This musing includes a gorgeous musical interlude by Philip Horwitz.

Over the course of a few months recently, I wandered through the forests and woodlands near my home, eyes on the undergrowth, looking for fungus. I was amazed at how many different kinds of mushrooms I found and how beautiful they are. All the photos in The humble mushroom are from a tiny area of Australia.

Click the image below, sit back, listen to some stories about mushrooms, then relax into the musical interlude.

[image error]

For those who want to experiment

Would you like to put something similar together? This communication style may even be useful for some types of technical documentation. I recently wrote some guidelines on how to record yourself in a webcam view and show a presentation at the same time.

September 19, 2020

Top tip for breaking writer’s block

My top tip for getting out of writer’s block is: Move to a different medium, temporarily. Yesterday I was struggling to get started with some writing, and I remembered that this strategy often works for me. So I tried it. It worked again!

By “moving to a different medium”, I mean opening a text editor and jotting my thoughts there, or writing on a scratch pad, or simply opening a page that is completely separated from the work that I’m trying to complete.

When I’m trying to write something, there are two decisions I need to make:

What do I want to say?

Where should I put it?

Sometimes the two decisions are so intertwined that my brain gets in a loop. I start writing, then I think, “Wait, this shouldn’t go here.” So I delete what I’ve written. But then I realise that I do need to write it, and start again, and … loop. Then I spend time trying to figure out where the content should go, which makes me lose my thread of thought and lose impetus.

This destructive loop can happen in any type of writing. Most recently, it happened to me when I was providing detailed feedback in a doc review. I wanted to help the author with the syntax and correctness of the content, but the work also needed higher-level input on the structure of the page as a whole and its location in the doc set. I started putting my feedback on the page itself, but some of the feedback was too high level to belong on the page, or so I thought. So I removed what I’d written. But then there was nowhere to put that feedback, and I lost time trying to figure out how to give the feedback rather than focusing on what the feedback actually should be.

Then I remembered what’s worked before! I moved out of the doc review tool into a text editor and jotted down my feedback as it came to me, without trying to decide where it belonged. When I’d finished, it was easy to slot the pieces of feedback into the right place.

This type of writer’s block can happen when you’re writing a book (“should this content be in the book, or is it more like plot and character notes for me, or should it be in the blurb?”) or a technical document (“does this content belong in this doc or another doc, or should I split the doc, or does it belong in a blog post?”) and so on..

Moving to a different format or medium gives my brain the freedom to write what I need to say. After that, it’s relatively easy to decide where the content should go.

September 11, 2020

Live streaming with StreamYard to record presentation and webcam view

I’ve recently started a YouTube channel called Soothing Musings with Sarah. I’ll tell you a bit about the channel itself later. First, though, I want to share what I learned about how to record a presentation alongside a webcam view of myself. After quite a bit of investigation, I found that the best combination of services for my needs is StreamYard, Google Slides, and YouTube.

For my video format, I wanted to include a mini window showing myself talking. I therefore needed an app that would record a webcam view. Alongside the talking me, I wanted a main window showing pictures of the thing I was talking about. For the main window, I decided a slide deck would be best, so that I could include text as well as photos. So, I needed an app that would record a slide presentation, as well as the mini window of me as presenter.

Here’s the end result:

I already had a Gmail account, which gives me access to Google Slides for presentations, and YouTube for sharing videos.

Getting started with Google Slides and YouTube

You can get help from the Google documentation on how to set up an account. You can use the same account for Gmail, Google Slides, and YouTube. There’s also information on how to create presentations with Google Slides.

Setting up a named YouTube channel

When you set up a YouTube account, you automatically get a YouTube channel that has the same name as your account. For my videos, I wanted a channel with a specific name: Soothing Musings with Sarah. YouTube calls a named channel a brand account (or sometimes just an account). A brand account doesn’t need to be a business account.

The YouTube docs describe how to set up a named channel. One thing to note is that there may be a 24-hour delay before your new named channel is available. I found there was no delay for my default YouTube channel, but the delay did occur for the named channel (brand account) which I created.

StreamYard for recording of presentation and webcam view

StreamYard gives you a browser-based streaming studio. I’m using Chrome as my browser. StreamYard works by streaming your recorded video directly to YouTube. All you need to do is set up your screen layout and other options in StreamYard, then record the session. As soon as you finish the session, you can watch your video on your YouTube channel. StreamYard gives you a link to the video on YouTube, which you can find on the StreamYard dashboard.

After you finish recording your video on StreamYard, YouTube still needs to complete some post-processing, which can take a few hours. When that’s done, your video becomes visible in the list of videos in your YouTube channel. That’s also when you can set the video thumbnail and download the video. Note that you can view the video on YouTube immediately after finishing the session on StreamYard, even before YouTube’s post-processing is finished.

Connecting StreamYard to YouTube

Here’s how to connect StreamYard to your YouTube channel:

Sign up for a StreamYard account. StreamYard offers free and paid plans.

In StreamYard, go to the destinations page. As you can see in this screenshot, I currently have two destinations set up in Streamyard: one for my default YouTube account, and one for my brand account. Your destinations page is probably empty at this point:

[image error]

Click Add a Destination.

On the next page, click YouTube Channel:

[image error]

Follow the prompts to sign in to Google and to choose your account or brand account. Make sure you use the email address that you used to set up your YouTube channel.

When that’s all done, you’re ready to create your first recording, which StreamYard calls a broadcast.

Recording your session on StreamYard

The following steps include some tips that I gleaned while experimenting with StreamYard. They may not all apply to you, but they’ll at least help you get started.

Get ready to be filmed.

April 24, 2020

What is Git cherry picking and how do you use it?

“Cherry pick a commit”. I’ve heard the phrase often. It sounds kind of endearing, yet scarily technical at the same time. What is cherry picking and why would you want to do it? One fine day I found that I needed it, and suddenly I appreciated the what and the why. So I figured out the how. I hope this post will help you towards the same understanding.

Here’s the scenario: I’d applied a change to the latest version of the Kubeflow docs. Specifically, the change added a banner and associated logic to inform readers if they’re reading an archived version of the docs. Now I needed to copy the same banner and logic to the older (archived) versions of the docs.

More details of the scenario

The screenshot below shows the banner that I wanted to add to all the archived versions of the docs:

The way we store archived versions of the Kubeflow docs is to make a branch of the current version (that is, a branch from the master). For example, here’s v0.6 of the docs, for which the source is in this branch on GitHub. The master branch contains the current version of the docs.

I’d added the banner and accompanying logic to the master branch in this pull request (PR). Now I needed to copy the code to all the archived branches. I didn’t want to have to copy/paste all my changes into the relevant files in every affected branch.

Enter cherry picking.

Picking sweet cherries

It’s useful to know that, when you’re using GitHub, cherry picking a commit is equivalent to cherry-picking a PR. GitHub squashes all the commits in a PR into a single commit when merging the PR into the code base.

What does a cherry-picked PR look like? No different from any other PR. It’s a collection of changes that you want to make, pointing to the branch on which you want to make them. For example, PR #1550 is a cherry pick of PR #1535, with a few extra changes added after cherry picking.

Below are the steps that I figured out to prepare and do the cherry picking. One thing to note in particular is that I had to do something different if my fork of the repository already contained a copy of the branch into which I intended to cherry pick.

The first step is to check out the master branch, which contains the updates that I want to copy to the archive branches:

git checkout master

Make sure my local working directory is up to date, by pulling all content from the remote master branch. (I’m working on a fork of the Kubeflow website repository. The convention is to give the name upstream to the repository from which you forked.)

git pull upstream master

Get a log of commits made to the master branch, to find the commit that I want to cherry pick:

git log upstream/master

A commit name consists of a long string of letters and numbers. Let’s say that I need the commit named e895a107edba5e68cc0e36fa3a05a687e806cc19.

Check to see which branches I have locally:

git branch -v

Also check my fork on GitHub to see which branches I already have there.

Now I’m ready to prepare the first archived branch for cherry picking. Let’s say I start with the version 0.6 branch of the docs, named v0.6-branch. If I don’t already have the branch on my fork, I need to get a copy of the branch from the remote master, and then push that copy up to my fork, so that I have a clean slate to apply the cherry pick to. So, I pull the branch down to my local working directory then push it up to my fork. In this example, the branch name is v0.6-branch:

git checkout master

git pull upstream v0.6-branch:v0.6-branch

git checkout v0.6-branch

git push origin v0.6-branch

(I’m working on a fork of the Kubeflow website repository. By default, the name of your fork of the repository is origin.)

In the cases where I do already have the branch on my fork, I need to copy the branch from my fork down to my local working directory, check that the branch is up to date by fetching updates from the main repository, then push the branch back up to my fork. In this example, the branch name is v0.5-branch:

git fetch origin v0.5-branch:v0.5-branch

git checkout v0.5-branch

git status

git fetch upstream v0.5-branch

git push origin v0.5-branch

Now I’m ready to cherry pick the changes I need. Remember, I’m cherry picking from master into an archive branch. Let’s say I want to cherry pick into the v0.6-branch:

git checkout v0.6-branch

git cherry-pick e895a107edba5e68cc0e36fa3a05a687e806cc19

The long string of letters and numbers is the name of the commit, which I obtained earlier by running git log.

The changes are now in my local copy of the branch. I can make extra changes if I want to. (For example, in my case I needed to update some metadata that relates specifically to the branch, including an archive flag used in the logic that determines whether to display the banner on the doc pages.)

When I’m happy with the cherry-picked updates and any other changes I’ve made, I push the updated branch up to my fork:

git push origin v0.6-branch

Then I create a PR and specify the base branch to be the name of the branch into which I’m cherry picking the changes. In the case of the above example, the base branch should be “v0.6-branch”. The screenshot below shows the base option, currently pointing to “master”, on the GitHub UI when creating a PR:

Can the cherries turn sour?

In the above scenario, I used cherry picking to apply a change going backwards in time. The requirement was to apply an update to older versions of the docs, which as a rule we don’t update very often. I didn’t cherry pick from a feature branch into the master branch. There are plenty of warnings on the web about things that could go wrong when you cherry pick. I found this post by Rob Friesel helpful in providing context in a non-scary way.

How did I make the banner itself?

That’s another story.

March 31, 2020

How to add a banner to website pages using Hugo

A while back, I needed to display a banner on every page of a documentation website. Furthermore, I wanted the banner to appear only under specific conditions. We use Hugo as the static site generator for the website. Here’s what I figured out, using Hugo templates.

I wanted to add a banner to the archived versions of the Kubeflow documentation, such as v0.7 and v0.6, letting readers know that they’re viewing an unmaintained version and pointing them to the latest docs.

Here’s an example of such a banner:

In Kubeflow’s case, the purpose of the banner is to catch people who enter the archived documentation from a web search and make sure they realise that a more up-to-date set of docs is available.

Summary: Adding a banner to a page with Hugo templating

In essence, you need to do the following:

Figure out which Hugo layout file is responsible for the base layout of your pages. In the case of the Kubeflow docs, the responsible layout file is at layouts/docs/baseof.html. You can see an example of the layout file in the Docsy theme: layouts/docs/baseof.html. (Kubeflow uses Docsy on top of Hugo.)

Add the code for your banner to the layout file. Or, even better, create a partial layout, often called just a partial. A partial is a snippet of code written in Hugo’s templating language. Put the code for your banner into the partial, then call the partial from the base layout. For the Kubeflow version banner, the code sits in a Hugo partial named version-banner.html.

There’s an explanation of the code later in this post.

Making the banner’s appearance conditional

In order to offer docs for multiple versions of Kubeflow, we have a number of websites, one for each major version of the product. The overall configuration of the websites for the different versions is the same. For example, we have the current Kubeflow documentation, and archived versions 0.7 and 0.6.

I wanted to make sure we had to do only minimal extra configuration to cause the banner to appear on the archived doc sets. I didn’t want to have to edit the layouts each time we create an archive. A good solution seemed to be a parameter that we can set in the site’s configuration file.

How it works – first the configuration settings

The parameter that controls the appearance/non-appearance of the banner is named archived_version. If the parameter is set to true, the banner appears on the website. The parameter value is false for the main doc site, kubeflow.org. When we create an archived version of the docs, we set the parameter to true.

The parameter is defined in the site configuration file, config.toml. The configuration file also contains a version number and the URL for the latest version of the docs. Both these fields are used in the banner text.

Here’s a snippet showing the relevant part of the configuration file:

# The major.minor version tag for the version of the docs represented in this

# branch of the repository. Used in the "version-banner" partial to display a

# version number for this doc set.

version = "v1.0"

# Flag used in the "version-banner" partial to decide whether to display a

# banner on every page indicating that this is an archived version of the docs.

archived_version = false

# A link to latest version of the docs. Used in the "version-banner" partial to

# point people to the main doc site.

url_latest_version = "https://kubeflow.org/docs/"

How it works – the content and logic

For the Kubeflow website, a Hugo layout file is responsible for the base layout of the documentation pages:layouts/docs/baseof.html. You can see an example of the layout file in the Docsy theme: layouts/docs/baseof.html. (Kubeflow uses Docsy on top of Hugo.)

I inserted the following line into the base layout:

{{ partial "version-banner.html" . }}

The above line calls a Hugo partial named version-banner.html. The partial contains the banner content and logic. (I’ve contributed the logic for the version banner to Docsy, which is why the URL leads to the Docsy repository.)

Below is a screenshot of the content of the partial. Unfortunately I can’t paste the code, because WordPress strips out all HTML:

You can copy the code from the partial: version-banner.html.

The code does the following:

Check the value of the archived_version parameter. If true, continue to the next step.

Get the value of the url_latest_version parameter, for use in the banner content when giving readers a link to the latest version of the docs.

Get the value of the version parameter, for use in the banner content when showing readers the version of the website that they’re viewing.

Create an HTML div containing the styling and content for the banner.

Here’s the screenshot of the banner again, so that you can compare it to the HTML div:

Docs or it didn’t happen

I created a user guide for other people who want to use the banner logic on their sites using the Docsy theme: How to display a banner on archived doc sites.

I also updated the release procedures for the Kubeflow engineering/docs team, explaining that we must set the archived_version parameter to true when archiving a website version.

In closing

I hope this post is useful to you, if you find that you need to add a banner to a website using Hugo templating!