Sarah Maddox's Blog, page 26

April 5, 2014

Login or log in – a way to choose one word or two

‘Login’ or ‘log in’? One word or two? It’s an oft-debated question. I’m not proposing a hard-and-fast rule, though I do have my preferences. What this post offers is a handy way of choosing between one word and two, if it’s important to you.

It’s not just logging in that’s affected. There are plenty more cases where we need to choose one word or two:

‘logon’ or ‘log on’

‘logout’ or ‘log out’

‘signup’ or ‘sign up’

‘shutdown’ or ‘shut down’

‘backup’ or ‘back up’

‘setup’ or ‘set up’

and more, including words not related to computing, such as ‘workout’ versus ‘work out’

Who’s up for an experiment?

Warning: Don’t try this at home, unless your partner is in a good mood.

Try speaking these sentences out loud, replacing ‘bbbbbbb’ with ‘backup’ and ignoring the spelling for now:

What is your bbbbbbb strategy?

When did you last bbbbbbb your data?

When did you last do a bbbbbbb?

Now try these, replacing ‘llllllll’ with ‘login’:

What are your llllllll details?

Where can I llllllll to the bank’s website?

My llllllll failed.

Did you notice any pattern in the way you pronounced the words “back/up” and “log/in”? If you’re like me, your stress pattern in the middle sentences would be different from the first and third sentences.

In the middle sentence, you would give equal emphasis to both parts of the phrase: back up; log in.

In the first and third sentences, you would give greater emphasis to the first part of the phrase: backup; login.

And the answer is…

‘Backup’ or ‘back up’:

What is your backup strategy?

When did you last back up your data?

When did you last do a backup?

‘Login’ or ‘log in’:

What are your login details?

Where can I log in to the bank’s website?

My login failed.

Rules and things

It may be that you decide to go with the growing common usage, and just use one word (like ‘login’) for everything. But if you want to follow the ‘rules’, they’re something like this:

If it’s a verb, use two words.

If it’s a noun, including cases when the noun is used to qualify another noun, use one word.

What about hyphens (‘-’)? Technical writers try to avoid them.

Who decreed that this is how it’s done, and where is it written down? Most tech writers and other guardians of language would agree that we should be descriptive rather than prescriptive, and that there are a equally-viable alternatives out there. But we also agree that it’s good to have a standard, so that our readers have a smooth ride through the documentation and application screens.

Here are some style guides and commentaries that agree we use one word for a noun, two for a verb:

Guardian and Observer Style Guide – Scroll down to the entries for ‘log in’ and ‘login’.

Log in vs. login by Grammarist – This post has some useful examples from online newspapers.

A thread on the English Language and Usage Stack Exchange – People express various opinions, but the consensus is one word for a noun, two for a verb.

Another thread on the English Language and Usage Stack Exchange – This one is particularly cool, because someone pointed out in a comment that the instructions on the Stack Exchange page itself said ’Sign up or login’, and Stack Exchange fixed it!

The Wikipedia page on login – The page consistently uses ‘login’ as a noun and ‘log in’ as a verb. It also states, ‘The noun login comes from the verb (to) log in‘.

And someone who has a strong opinion, backed up by good research: “Login” is not a verb.

Who cares? Is this a difference between US and British usage? I don’t think so. It’s more a difference between people who feel a sense of jarring disconnect when someone uses ‘login’ and the like as a verb, and people who don’t. If you do want to differentiate, the pronunciation test may be the quickest way to decide whether you need one word or two.

There’s only one word for this spider: Eek!

This spider took up residence between my window panels for a while. It’s a huntsman: huge, very fast, scary but beautiful, and largely harmless. I put the peg there for scale. It’s a large peg.

March 15, 2014

Are conference proceedings papers useful

I’m composing my proceedings paper for STC Summit 2014. Not all conferences require a proceedings paper. This set me wondering: Do people find proceedings papers useful? Do you read them, either during or after the conference, or perhaps not at all?

The “proceedings” of a conference is a collection of papers written by conference speakers. The content of a proceedings paper may be a summary of the talk, or an academic treatment of the topic of the talk, or a deep dive into one aspect of the talk.

My upcoming presentation at STC Summit 2014 is API Technical Writing: What, Why and How. For the proceedings paper, I’ve decided to write a deep-dive description of APIs. In the live session at the conference, I’ll cover the same content in less depth, then focus on examples of APIs and on their documentation, and on the role of the technical writer.

Some conferences ask speakers to present their slides a couple of months ahead of the conference date, so that the slides can be included in the documentation handed out to attendees. Others, like STC Summit, ask for a proceedings paper ahead of time, and the slides much closer to the date of the event.

When attending a conference session, I sometimes follow along on the slides if they’re part of the conference package. This is helpful if I can’t see the screen too well, or if I want to make notes on the slides. It’s very seldom that I refer to the conference proceedings. I think I’ve only done that once or twice throughout the years, and it’s been when I want an in depth look into the topic of a particularly interesting session.

What do you think? Are proceedings papers useful, how do you use them, and do you prefer the slides, the papers, or both?

March 8, 2014

What I get from speaking at conferences

I’m in the throes of composition. My presentation for STC Summit 2014 is in good shape, and I’m working on the proceedings paper right now. I got to thinking about why I put myself up for speaking at conferences. It’s a lot of work! Is it worth it? I also saw a post from Neal Kaplan, who doesn’t get conferences. So I decided to blog my thoughts.

If you’d told me five years ago that you’d seen me speaking at a conference, my reaction would have been

Ha ha, nope, that must have been some other Sarah.

Public speaking scared me to death. (Actually, it still does.) I never thought I’d be able to do it. Simply standing in front of a handful of peers turned me into a blob of jelly on a roller coaster.

Then Joe Welinske asked me to speak at WritersUA in Seattle in 2009. Of course, I said “Eek, no.” But Joe’s sweet persistence persuaded me to think about it. After all, he said, I knew a lot about what was then an emerging technology for technical writing: wikis. A few days later, Joe asked me again. To my utter horror, I said yes. My thinking went along these lines: I know no-one in the US. I’ve never even been to the US. If I make a total fool of myself, it doesn’t matter. No-one I know will ever know.

I survived WritersUA 2009. And now, five years later, I’ve spoken at twelve conferences.

Oft-discussed benefits of attending conferences include:

Peers: Meeting other tech writers has been hugely rewarding. It’s especially great to meet in person the people I’ve bumped into on blogs, Twitter, and other online meeting spots.

Learning: Conferences seed ideas. I see what other people are up to, get a glimpse of new technologies, peer at different products. A while later, an idea pops up about something I can use in my own environment.

What’s the benefit of speaking yourself?

Getting funding to attend the conference is a big one. For me, living in Australia, the travel costs are too big to cover personally.

But for me, the biggie is this: Putting together a presentation makes me think about how others see what I’m doing. It makes me look at my own work, and that of my team, in a new light. It gives me a wider perspective. It firms up my own opinions on what are good procedures to follow, and what could do with tweaking.

So, a call to all conference speakers: why do you do it?

February 15, 2014

API types

I’m putting together a list of the various types of API we might encounter. This is primarily a resource for technical writers, who may need to know what type of thing they could be asked to document if they take on the role of API tech writer.

A Google search didn’t reveal much material about API types. The best source of information is the Wikipedia page on APIs.

I tried searching for “API classification” and received plenty of information about engine oil.

So here goes… my attempt at an API classification.

Before we start: What is an API?

API stands for “application programming interface”. Put briefly, an API consists of a set of rules describing how one application can interact with another, and the mechanisms that allow such interaction to happen.

What is an interaction between two applications? Typically, an interaction occurs when one application would like to access the data held by another application, or send data to that app. Another interaction might be when one application wants to request a service from another.

A key thing to note: An API is (usually) not a user interface. It provides software-to-software interaction, not user interactions. Sometimes, though, an API may provide a user interface widget, which an app can grab and display.

There are two primary benefits that an API brings:

Simplification, by providing a layer that hides complexity.

Standardisation.

Examples:

Microsoft Word asks the active printer to return its status. Microsoft Word does not care what kind of printer is available. The API worries about that.

Bloggers on WordPress can embed their Twitter stream into their blog’s sidebar. WordPress uses the Twitter API to enable this.

Web service APIs

A web service is a piece of software, or a system, that provides access to its services via an address on the World Wide Web. This address is known as a URI, or URL. The key point is that the web service offers its information in a format that other applications can “understand”, or parse.

Examples: The Flickr API, the Google Static Maps API, and the other Google Maps web services.

A web service uses HTTP to exchange information. (Or HTTPS, which is an encrypted version of HTTP.)

When an application, the “client”, wants to communicate with the web service, the application sends an HTTP request. The web service then sends an HTTP response.

In the request, much of the required information is passed in the URL itself, as paths in the URL and/or as URL parameters.

For example:

http://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/staticmap?center=Sydney,NSW&zoom=14&size=400x400&sensor=false

In addition to the URL, HTTP requests and responses will include information in the header and the body of the message. Request and response “headers” include various types of metadata, such as the browser being used, the content type, language (human, not software), and more.

The body includes additional data in the request or response. Common data formats are XML and JSON. The process of converting data from internal format (for example, a database or a class) to the transferrable format is called “data serialization”.

Most often-used types of web service:

SOAP

XML-RPC

JSON-RPC

REST

SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol)

SOAP is a protocol that defines the communication method, and the structure of the messages. The data transfer format is XML.

A SOAP service publishes a definition of its interface in a machine-readable document, using WSDL – Web Services Definition Language.

XML-RPC

XML-RPC is an older protocol than SOAP. It uses a specific XML format for data transfer, whereas SOAP allows a proprietary XML format. An XML-RPC call tends to be much simpler, and to use less bandwidth, than a SOAP call. (SOAP is known to be “verbose”.) SOAP and XML-RPC have different levels of support in various libraries. There’s good information in this Stack Overflow thread.

JSON-RPC

JSON-RPC is similar to XML-RPC, but uses JSON instead of XML for data transfer.

REST (Representational state transfer)

REST is not a protocol, but rather a set of architectural principles. The thing that differentiates a REST service from other web services is its architecture. Some of the characteristics required of a REST service include simplicity of interfaces, identification of resources within the request, and the ability to manipulate the resources via the interface. There are a number of other, more fundamental architectural requirements too.

Looked at from the point of view of a client application, REST services tend to offer an easy-to-parse URL structure, consisting primarily of nouns that reflect the logical, hierarchical categories of the data on offer.

For example, let’s say you need to get a list of trees from an API at example-tree-service.com. You might submit a request like this:

http://example-tree-service.com/trees

Perhaps you already know the scientific name of a tree family, Leptospermum, and you need to know the common name. You request might look like this:

http://example-tree-service.com/trees/leptospermum

The tree service might then send a response containing a bunch of information about the Leptospermum family, including a field “common-name” containing the value “teatrees”.

An example of a REST API: The JIRA REST APIs from Atlassian.

The most commonly-used data format is JSON or XML. Often the service will offer a choice, and the client can request one or the other by including “json” or “xml” in the URL path or in a URL parameter.

A REST service may publish a WADL document describing the resources it has available, and the methods it will accept to access those resources. WADL stands for Web Application Description Language. It’s an XML format that provides a machine-processable description of an HTTP-based Web applications. If there’s no WADL document available, developers rely on documentation to tell them what resources and methods are available. Most web services still rely on documentation rather than a machine-readable description of their interface.

In a well-defined REST service, there is no tight coupling between the REST interface and the underlying architecture of the service. This is often cited as the main advantage of REST over RPC (Remote Procedure Call) architectures. Clients calling the service are not dependent on the underlying method names or data structures of the service. Instead, the REST interfaces merely represent the logical resources and functionality available. The structure of the data in the message is independent of the service’s data structure. The message contains a representation of the data. Changes to the underlying service must not break the clients.

Library-based APIs

To use this type of API, an application will reference or import a library of code or of binary functions, and use the functions/routines from that library to perform actions and exchange information.

JavaScript APIs are a good example. Take a look at the Google Maps JavaScript API. To display an interactive Google Map on a web page, you add a

Another example is the JavaScript Datastore API from Dropbox. And the Twilio APIs offer libraries for a range of languages and frameworks, including PHP, Python, JavaScript, and many more.

TWAIN is an API and communications protocol for scanners and cameras. For example, when you buy an HP scanner you will also get a TWAIN software library, written to comply with the TWAIN standard which supports multiple device types. Applications will use TWAIN to talk to your scanner.

The Oracle Call Interface (OCI) consists of a set of C-language software APIs which provide an interface to the Oracle database.

Class-based APIs (object oriented) – a special type of library-based API

These APIs provide data and functionality organised around classes, as defined in object-oriented languages. Each class offers a discrete set of information and associated behaviours, often corresponding to a human understanding of a concept.

The Java programming community offers a number of good examples of object oriented, or classed-based, APIs. For example:

The Java API itself. This is a set of classes that come along with the Java development environment (JDK) and which are indispensable if you’re going to program in Java. The Java language includes the basic syntax and primitive types. The classes in the Java API provide everything else – things like strings, arrays, the renowned Object, and much much more.

The Android API.

The Google Maps Android API.

As an example for C#, there’s the MSDN Class Library for the .NET Framework. The Twilio APIs mentioned above also include both Java and C#.

Functions or routines in an OS

Operating systems, like Windows and UNIX, provide many functions and routines that we use every day without thinking about it. These OSes offer an API too, so that software programs can interact with the OS.

Examples of functionality provided by the API: Access to the file system, printing documents, displaying the content of a file on the console, error notifications, access to the user interface provided by the OS.

Object remoting APIs

These APIs use a remoting protocol, such as CORBA – Common Object Request Broker Architecture. Such an API works by implementing local proxy objects to represent the remote objects, and interacting with the local object. The same interaction is then duplicated on the remote object, via the protocol.

As far as I can tell, most of these APIs are now considered legacy. Another example is .NET Remoting.

Hardware APIs

Hardware APIs are for manipulating addressable pieces of hardware on a device – things like video acceleration, hard disk drives, PCI buses.

Other developer products

There’s more to life than APIs, of course.  A technical writer may be called upon to document other developer-focused products:

A technical writer may be called upon to document other developer-focused products:

SDKs – software development kits, which typically contain a set of tools that developers use to interact with, and develop on top of, your product.

IDE plugins – custom additions to standard development environments, which give developers the extra tools they need to interact with your product from within a development environment like Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, or Visual Studio.

Code libraries that developers can import into their projects.

Other frameworks that support software development in a specific environment, such as custom XML specifications, templates, UI guidelines.

There’s more than one way to can has a cat

Your turn. What have I missed, and are there more useful ways of classifying APIs?

February 8, 2014

World’s best API documentation – what do you think

I’m curious to see how things have changed since I last asked this question, back in March 2012: What’s your favourite API documentation, and why?

Part of the reason for asking is that I’ll soon present a session at STC Summit 2014 on API technical writing. I want to give examples of excellent documentation. I have some favourite documentation sets myself, but it’s great to get the opinions of developers and other technical writers too.

So, have at it!  Please comment on this post.

Please comment on this post.

What’s your favourite API documentation, and why?

I’ll also collect any suggestions that people send via Twitter, Google+, and other channels, and add the links to this post.

OT: This has to be the world’s best bird. Well, it’s my current favourite anyway. This is a Tawny Frogmouth, spotted on an early morning walk. Tawny Frogmouths are night birds, about the size of a large owl (34-52 centimetres). During the day, they pretend to be old tree branches.

February 1, 2014

Tools for technical writers – the super-useful list

I’ll be speaking about API technical writing at STC Summit 2014. Part of the presentation is about useful tools for API technical writers. Since there are already some great resources on the Web about editors and IDEs, I plan to focus on a motley collection of “other” tools. Those that do a specific job very well. Those of which you’d say, “When I need it, I really need it.”

There are plenty of blog posts and articles about tools for documentation and code, including open source tools. Particularly when talking about editors and IDEs (Integrated Development Environments) most people have their favourites. The debates about which tool is best can get quite fiery!

Here are some useful links:

Mike McCallister’s presentation, Open Source Tools for User Assistance. It’s well worth following Mike’s blog too.

Chantel Brathwaite, writing on the TechWhirl blog about Technical Writing on a Shoestring.

From Bret McGowen on the Rackspace blog, My Text Editor Final Four.

So, aren’t you going to talk about editors at all?

Hehe, I can’t resist mentioning my favourite editor, Komodo. It supports a number of languages. I use it primarily for HTML, CSS and JavaScript. I do dip in and out of other editors when I need to. For example, if trapped on a Linux VM where I don’t have my own editor, I may find myself in Pico editor. I can even get by in vi.

My favourite IDE is Eclipse. I like to dabble in Android Studio and IntelliJ IDEA, just to see what’s happening.

Now that’s out of the way, let’s look at some super-useful and less-talked-about tools for API tech writers in particular.

Syntax highlighter for code samples

I frequently need to add a code sample to an HTML page, or include a slice of code in a presentation. Code is much easier to understand if the text is highlighted to indicate method names, variable declarations, and other syntactical essentials. And it just looks prettier too.

hilite.me converts a code snippet into styled HTML, which you can copy and paste into your page. Paste in your code, and select the coding language, to get the appropriate highlighting. Then click “Highlight!” to see the result. You can grab the HTML and CSS code, or copy and paste the highlighted text itself. You can even choose from a number of styles, such as “colorful”, “friendly”, “fruity”, and so on.

For example, I pasted in a Java “hello world” class, and asked for “tango” style highlighting. The “Preview” box at the bottom of this screenshot shows the result:

hilite.me

Testing web services and REST APIs

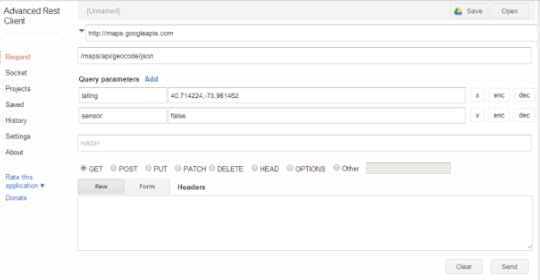

There’s an add-on for Chrome browser, called the Advanced REST Client, which I find very useful for getting examples of web service requests and responses. You can craft an HTTP request, then submit the request and see the response. This is a nice GUI alternative to a command-line tool like cURL.

Let’s say I want to use the Google Geocoding API to get a human-readable address for a pair of latitude/longitude coordinates. My URL would look like this:

http://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/geocode/json?latlng=40.714224,-73.961452&sensor=false

I’ve pasted the above URL into the Advanced REST Client tab in Chrome, then used the add-on to expand the URL parameters, making it easy to see the composition of the HTTP request:

Advanced REST Client – request

Now press the “Send” button to see the response. This is a partial screenshot:

Advanced REST Client – response

Very handy indeed.

Chrome Developer Tools

The Chrome Developer Tools are a little tricky to grok, but once you’ve figured out what’s going on, they’re coolth personified. To find them, click the three-barred icon at top right of the Chrome window (the tooltip says “Customize and control Google Chrome”) then choose “Tools” > “Developer Tools”. The keyboard shortcut is Ctrl+Shift+I or Cmd+Shift+I.

A panel opens at the bottom of the page. It’s pretty busy, so take your time getting used to it. You can click an option to undock the panel and see it as a separate window, if you prefer that. In this screenshot, the DevTools panel is open at the bottom of the screen, and is showing the “Elements” tab:

Chrome DevTools

There are many many things you can do with the DevTools. The Chrome DevTools documentation is a good guide. These are the functions I use most often:

Check which CSS style is in effect on a particular block of HTML. This is particularly useful when there are a number of stylesheets at play. Sometimes the cascading effect of CSS doesn’t seem to follow the laws of gravity!

Debug a JavaScript function, using breakpoints and variable watches.

Watch the error messages scrolling past on the “Console” tab.

Edit HTML on the spot, to see the effect live on a web page before putting my changes into the source code.

Open Device Labs – Access to real devices and platforms for test-driving an app

It can be very difficult to try out an application on every supported device or platform. Especially for those of us dealing with mobile apps, there are just way too many devices out there for it to be feasible to have an example of each one.

One solution is to use emulators. But here’s an exciting initiative that I heard about recently: Open Device Labs.

OpenDeviceLab.com

The idea is that people may have last year’s mobile phone lying around, that they’d be willing to allow other people to use for testing. Some people may even want to donate new devices to the cause. Smart, enthusiastic people have set up hubs of Internet-connected devices at various locations around the world, and made them available to us all to use. For free!

I haven’t yet used a device from one of these labs, but the idea is awesome. What a great way to test an app, get screenshots, figure out the “how to” instructions you need to write, and just see how the user experience feels.

Mobile emulator in Chrome browser

With Chrome’s mobile emulation, you can make your desktop browser pretend that it’s something else. It can masquerade as an iPhone, Kindle, Blackberry, Nexus, and more. This is very useful for taking screenshots, and for seeing how responsive an app is to different device sizes and resolutions. The emulator is available via a fairly obscure setting in the Chrome Developer Tools panel.

Emulator in Chrome Developer Tools

Source repositories

Online source repositories are good for sharing code. In a tutorial, it works well to include code snippets and point readers to the complete source in a repo. Bitbucket and GitHub are very popular. I have accounts on both, because I’ve worked with teams on both. GitHub works with Git, while Bitbucket supports both Git and Mercurial.

More?

That’s my list so far. If I find any more tools before the STC Summit in May, I’ll add them to the list I’m creating for my presentation. It will be fun to share them with the tech writers at the conference. Can you think of any super-useful tools to add to the list?

January 17, 2014

Storyboards for video design and review

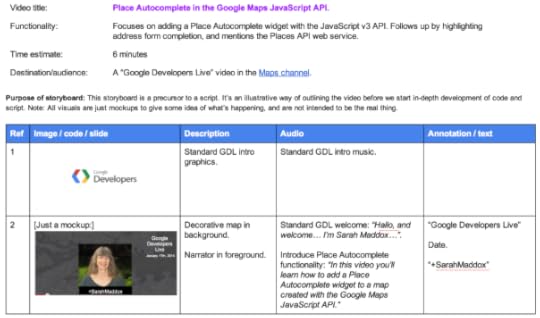

I’ve just created two short instructional videos, introducing specific aspects of our APIs to developers. I used a storyboard as a way of outlining the video content, illustrating my ideas about the flow of the video, and requesting a review from my colleagues.

A colleague, Rachel, introduced me to the idea of storyboarding a while ago. This is the first time I’ve tried it.

What a storyboard looks like

This is what the storyboard looked like when I sent it out for initial review comments:

My first storyboard

To get started, I looked at the examples Rachel had given me of her own storyboards, remembering her very useful comments about how she used them. Then I looked online to see what other people are doing. I found two examples that gave me more good ideas on how to represent my video design in a storyboard:

Storyboards, from the Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design. I like the Hunting Sequence from the Jane Animation Project.

Storyboarding, from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. The sketches at the bottom of the page are appealing, and show how different formats of storyboard are useful in different situations.

The design of my storyboard is a conglomeration of ideas generated by my colleagues examples and the two sources above. I shared my storyboard template with members of my team, and suggested they may like to use something similar when designing videos. They like the idea, and each person adapted the template to suit them. This approach works surprisingly well.

What a storyboard is good for

For me, the primary goal of a storyboard is to share an easily-absorbed way of representing the flow of the video.

This is what I wrote at the top of my first storyboard:

This storyboard is a precursor to a script. It’s an illustrative way of outlining the video before we start in-depth development of code and script. Note: All visuals are just mockups to give some idea of what’s happening, and are not intended to be the real thing.

Building out the storyboard

As time passed, I fleshed out the script on the storyboard, replacing the outlined content with the words I was planning to say during the presentation. So the storyboard evolved continually during the scripting of the video, the flow design, and the planning of the visual aspects such as screenshots, demonstrations and annotations.

A number of colleagues responded to my requests for review. After a few revisions, my script was ready to move to a separate document for final tweaking and practice runs. This is what the storyboard looked like at that point:

The storyboard ready to be transformed into a script

The resulting video

This is the very first instructional video that I’ve ever presented! (Apart from videos shot during conference presentations.) It’s short by design. The target audience is developers who are using the Google Maps Android API to include maps in their Android apps.

Producing the video

I could write an entire blog post about the process of filming the video. So for now, I’ll just show you a couple of photos of the video production studio.

The first photo shows me sitting in the hot seat, with the green screen behind me. In the foreground are the two video production screens, with ATEM Television Studio (the input stream switcher) on the right and Wirecast (which we used to define the video format and control the flow) on the left.

In the hot seat in the video production studio

The second photo is a panoramic view from the hot seat, showing all the lights that glare down at you. The production centre in the middle at the back.

The view from the hot seat

Conclusion

A storyboard is a good tool for solidifying my own ideas about the video, showing them to others, and conducting a collaborative review.

I’d love to hear your ideas about storyboarding, the format of the storyboards you use, and how you find them useful (or not).

December 20, 2013

How to write sample code

Technical writers often need to create sample code, to illustrate the primary use case of an API or developer tool, and to help developers get started quickly in the use of the API or tool. Here are some tips on how to go about creating that code. I’ve jotted down everything I can think of. If you have more tips to add, please do.

I recently published a set of documentation on a utility library created by Chris Broadfoot, a Google developer programs engineer. The utility library is an adjunct to the Google Maps Android API. The documentation includes an overview of all the utilities in the library, a setup guide, and an in-depth guide to one of the utilities. (I’ll document more of the utilities as time goes on.) As part of the guide to the marker clustering utility, I created some sample code that illustrates the most basic usage of the utility and gets developers up and running fast.

Quick introduction to the API and the utility library

The Google Maps Android API is for developers who want to add a map to their Android apps. The API draws its data from the Google Maps database, handles the displaying of the map, and responds to gestures made by the user, such as zooming in and out of the map. You can also call API methods to add markers, rectangles and other polygons, segmented lines (called polylines), images (called ground overlays) and replacement map tiles (called tile overlays). It’s all in the API documentation.

The utility library is an extra set of code that developers can include in their Android apps. It includes a number of useful features that extend the base API. One of those features is “marker clustering”. The full list of features is in the utility library documentation.

The marker clustering utility

The sample code illustrates the marker clustering utility in Chris’s utility library. So before diving into the code, you be asking:

What’s “marker clustering”?

Let’s assume you have a map with a large number of markers. (Typically on a Google Map, a marker is one of those orange pointy droplets that marks a place on the map.) If you display all the markers at once and individually, the map looks ugly and is hard to grok, especially when the map is zoomed out and many markers are concentrated in a small area. One solution is to group neighbouring markers together into a single marker icon (a “cluster”) and then split them into individual marker icons when the user zooms out or clicks on the cluster icon. That’s what Chris‘s marker clustering utility does.

What does marker clustering look like? See the screenshots in the documentation.

Developers can implement the classes Chris has created and customise the appearance and behaviour of the clusters. The utility library also includes a demo app, containing sample implementations of the utilities.

The sample code

The best way to describe a code library is to provide sample code. I created a simple marker clustering example, based on the demo app. Take a look at the sample code in the documentation section on adding a simple marker clusterer.

Now compare it to the code in the demo app that’s part of the utility library: ClusteringDemoActivity.java

The differences, in a nutshell:

The sample code doesn’t show any of the “plumbing”, such as the library import statements.

The sample code does include a listing of both the primary method that does the clustering (called “setUpClusterer()“) and a class that’s important for developers to understand (“public class MyItem implements ClusterItem“).

Instead of reading input from a file, the sample code includes a method called “addItems()” to set up some sample data directly from within the code.

I’ve added plentiful comments to the sample code, explaining the bits that are specific to marker clustering or the sample itself.

In summary, the sample code provides all the developer needs to get a simple marker clusterer working, just by copying and pasting the code into an existing Android project.

How to write sample code

While writing the sample code, a thought struck me:

Hey, it’s actually quite an interesting process writing sample code. I’ll blog about what I’m doing here, and see what other technical writers have to say about it.

First, a stab at defining the goals for the sample code:

Get the developer up and running as quickly as possible.

Be suitable for copying and pasting.

Work (do what it’s meant to do) when dropped into a development project.

Be as simple as clear as possible.

Provide information that is not easy to find by reading the code.

Illustrate the primary, basic use case of the API or tool.

And here are my jottings on how to go about creating a useful code sample:

Find out what the primary and simplest use case is. That is what your code should illustrate. Talk to the engineers and product managers, read the requirements or design document, read the code comments.

Find out what you can safely assume about your audience. Can you assume they are familiar with the technology you’re working with (in my case, Java and Android development)? Do you know which development tools they are using?

Find some “real” code that does something similar to what you need. Perhaps a similar function or a working implementation that’s too complex for your needs.

Simplify it. Make names more meaningful. Remove functionality that’s unique to your environment or that adds super-duper but superfluous features. Remove plumbing such as import statements and all but the essential error handling.

Put your into a framework and test it. The framework should be one that your audience will be using. In my case, that’s an Android development project.

Take screenshots of the code in action. They’re often useful to give people an idea of the goal of the sample code, and of what the API or tool can do.

Get the code reviewed.

Include it in the doc.

If possible, put the code in a source repository and hook it up to some automated tests, to help ensure it will remain current.

As far as possible, have all the necessary code in one piece, so that people can copy and paste easily. This may mean moving stuff around.

Add code comments. Engineers often add technical comments to the code, but don’t include an introduction or conceptual overview of what’s going on. And our target audience, developers, will often read code comments where they don’t read other docs. So code comments are a great medium for technical communication!

Perhaps the most important thing to do is to see yourself as the advocate for or representative of those developers who need to use the API or tool you’re illustrating. Think what questions they would ask if they had access to the people and tools that you do, and put the answers into the documentation and sample code.

Conclusion

To do this job, tech writers need a certain level of coding knowledge, and also a good understanding of what a developer needs to get started. The sample code provides a stepping stone between the conceptual overviews and the complex implementations.

Well, that’s all I can think of. What have I forgotten?

December 14, 2013

How to start a YouTube video at a given point or time

Here’s a tip that technical writers will love! You can start a YouTube video at a specific point, by including the time-from-start in the URL or as a parameter in an embedded video.

Let’s say the sales team has produced a video introducing a number of new features in your product. Or an engineer has covered a suite of classes in an API. As a technical writer, you are writing about just one of those features, or just a subset of the classes. So, you need to start the video at the right point. Otherwise you’ll lose your readers!

In the examples below, I’ve used an excellent video from Chris Broadfoot, a Google engineer who is showing developers how to add spiffy map features to their Android apps using the Google Maps Android API utility library. I’m currently writing the documentation which focuses on just one of the utilities Chris covers: the Bubble Icon Factory. Does that sound like fun? It is! Watch the video to see what it’s about.

Using a URL to start a YouTube video at a specific point

Add the ‘t‘ parameter with a value in minutes and seconds. For example, this YouTube URL starts the video one and a half minutes into the story, where Chris talks about bubble icons:

http://youtu.be/nb2X9IjjZpM?t=1m30s

Starting an embedded YouTube video at a specific point

Use the ‘start‘ parameter and specify the number of seconds from the start of the video.

This is the code to embed a video using an iFrame, and start it at the 90-second point. Please assume the following code is within an HTML iframe element:

width="560" height="315" src="http://ffeathers.wordpress.com//www.y..." frameborder="0" allowfullscreen

Because this blog is on WordPress, I’ve used a WordPress macro to embed a video on this page and start it at the 90-second point. This is the code:

youtube=http://youtu.be/nb2X9IjjZpM?start=90

And here’s the result:

More parameters

The YouTube documentation has a list of other useful parameters, including ‘end‘ for stopping the video at a given time, and ‘rel‘ for showing or suppressing the list of related videos when yours stops playing.

November 30, 2013

How to check Java syntax in your sample code

Let’s say I’ve put together some sample Java code, and I want to check the syntax. What’s the easiest way to do that? This post compares two of the many possible solutions I’ve found. The first is to use the Java compiler (javac) from the command line. The second is to use Eclipse’s built-in syntax checker.

The Java compiler (javac) is part of the developer toolkit that comes with Java. You can run javac directly from the command line. Eclipse is a free and open source IDE (integrated development environment). For checking Java syntax, I prefer Eclipse because it’s smarter about figuring out the root cause of the problem, and the messages it gives are easier to understand.

I’m using a Mac running OS X, and Eclipse 4.2.1 bundled with the Android Developer Tools (ADT).

Kind reader, please note that I’m not a full-time Java programmer. I’m a technical writer building up her Java skills, and sharing information as she goes. So if I’ve made some silly mistakes, please tell me about them, and do it kindly.

Getting Java

Check that you have Java, by opening a command window (called a “Terminal” window on a Mac) and running this command:

java -version

You should see something like this:

java version "1.6.0_65"

Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 1.6.0_65-b14-462-11M4609)

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 20.65-b04-462, mixed mode)

If not, download and install Java, making sure you get a JDK (Java Development Kit) rather than just a JRE.

Confirm that you have the Java compiler by running this command:

javac -version

You should see something like this:

javac 1.6.0_65

If not, check your Java installation to ensure you have a JDK (Java Development Kit) installed.

Wrapping a Java class around your code

An important thing to understand is that you’ll need to wrap your code within a Java class. Even if you only want to check a single line of code or an itsy-bitsy method, you’ll need the framework of a class to give it context.

Let’s assume I want to build a string that includes some constant text plus two variables, representing someone’s favourite colour and toy. I’ve cobbled together this code, which builds the string and also prints it to the command window (the standard system output destination) for easy verification:

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

String s = String.format("My favourite toys are %s %s.", colour, toy);

System.out.println(s);

}

Here’s a simple class that includes the above code:

public class FavouriteToy {

// Since I have only one class,

// I must include the "public static main()" method in this class.

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Make an object to hang my "printToy()" method on.

FavouriteToy favToy = new FavouriteToy();

// Check the number of arguments received as input.

// Default to "purple koalas" if number is not 2.

if (args.length == 2) {

favToy.printToy(args[0], args[1]);

} else {

favToy.printToy("purple", "koalas");

}

}

// Construct and print a text string showing the favourite colour and toy

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

String s = String.format("My favourite toys are %s %s.", colour, toy);

System.out.println(s);

}

}

Save the code in a text file called FavouriteToy.java. Note that the file name must match the class name.

Using the Java compiler to check your code

Run the Java compiler to compile your Java file into an executable class file:

javac FavouriteToy.java

If everything goes well, your code has passed the syntax checks and you’ll notice that you now have a new file called FavouriteToy.class.

But what if you’ve made a mistake? The compiler will display the error messages in your command window. For example, if I forget to put the semicolon at the end of this line:

FavouriteToy favToy = new FavouriteToy()

Then I’ll see this in the command line:

javac FavouriteToy.java

FavouriteToy.java:8: ';' expected

FavouriteToy favToy = new FavouriteToy()

^

1 error

That’s quite handy. It even tells me exactly where in the line the missing semicolon should be, by placing the circumflex (^) in the right spot.

Things get tricky, though, when there’s a more complex error or more than one error. For example, this is what happens if I leave out the closing curly bracket for the main() method:

javac FavouriteToy.java

FavouriteToy.java:20: illegal start of expression

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:20: illegal start of expression

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:20: ';' expected

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:20: ';' expected

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:20: not a statement

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:20: ';' expected

private void printToy(String colour, String toy) {

^

FavouriteToy.java:24: reached end of file while parsing

}

^

7 errors

Eek!

Running the code on the command line

By the way, assuming your code has passed the compiler checks, you can run it via the command line with the java command. Here’s the command to run our sample class with a couple of input parameters, and the resulting output:

java FavouriteToy pink kangaroos

My favourite toys are pink kangaroos.

Using Eclipse to check your code

Eclipse is a free and open source development platform, including an IDE (integrated development environment) and a number of useful tools. The IDE includes a nice editing environment. Provided you let it know that your project is a Java project, it can do all sorts of fancy things for you.

Download the right version of Eclipse for your operating system. Installing it is simple: It’s just a matter of unzipping the downloaded file into a directory of your choice. See the installation guide.

Start Eclipse, and choose a workspace directory as prompted. You can leave it at the default. If the “Welcome” screen appears, close it.

Now you need to add a Java project, so that Eclipse knows what sort of files and project structure it will be dealing with. Choose “File” > “New” > “Java Project”. Enter a project name (like “TestPony”) and click “Finish”. You can leave all the other project settings at their defaults.

Time to explore a bit. Find the panel called “Project Explorer” in your Eclipse work area. If you can’t see the Project Explorer, choose “Window” > “Show View” > “Project Explorer”. In the Project Explorer, click the twisty arrow next to your project, to open up the file structure below the project name. You’ll see a “src” directory, which is currently empty, and a JRE system library.

The next step is to add the code for your Java class. Choose “File” > “New” > “File”. Select the “src” directory as the destination for the new file, and enter a file name, like “FavouriteToy.java”. Click “Finish”. (You could also let Eclipse know up front that you’re adding a class, by choosing “File” > “New” > “Class” instead of “File” > “New” > “File”.)

The file will appear in the Project Explorer, and will also open in the editor panel that occupies most of your Eclipse work area.

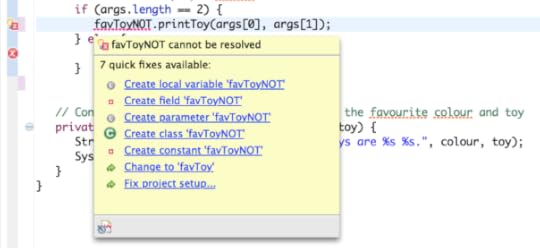

Paste your Java code into the editor panel. Eclipse immediately analyses the code and highlights errors.

This screenshot shows the Eclipse editor with my sample code. Two red circles with cross in the left-hand margin indicate lines with errors in them. There’s also a red squiggly underline on the offending portion of the line. I can hover over the red circle or the red squiggly line to see the error message:

Eclipse editor highlighting syntax errors

Here’s the neat error message for my second deliberate mistake, where I missed out a curly bracket:

Eclipse’s explanation of the missing curly bracket

I think you’ll agree that Eclipse’s message is much easier to understand than the 7 errors given by the javac command.

Eclipse is really neat

It was when I started getting more complicated Java errors that I really fell in love with Eclipse. It gives you suggestions on how to fix the problem!

Suggestions from Eclipse