Sarah Maddox's Blog, page 19

January 16, 2016

Learnings from a doc sprint

A doc sprint is an event where technical writers work with engineers and other product team members to develop or update documentation. A well planned doc sprint is productive and rewarding for the documentation and the participants. This post shares some of the things I’ve learned from recent sprints.

A doc sprint can last anything from a few hours to a few days. I’ve found two days to be a useful period when the focus is fixing bugs. That may seem a little long, but it gives the disparate members of the team time to contribute to the sprint while keeping their primary roles ticking along too. When working with a distributed team across time zones, it’s particularly useful to have a flexible period that gives everyone the opportunity to take part.

Sometimes people use the term “doc fixit” when the sprint is focused on fixing bugs rather than developing documentation for a new product. Either way, a sprint or a fixit is a time box focused on the documentation.

Why run a doc sprint?

The primary goal is to fix documentation bugs and thus improve customers’ experience of the product. Sometimes it’s hard for a small team of technical writers to find the time to fix the small things. Yet, to our customers, those small doc bugs can mean death by a thousand cuts.

By inviting the developers and support or sales engineers to update the documentation, we make immediate and direct use of the expertise of our subject matter experts. By inviting product managers and programme managers to assess the documentation requests and help prioritise them before the sprint, we’re making use of their product and customer knowledge too.

Another goal is to foster a feeling of ownership of, pride in, and responsibility for the documentation amongst the engineers. It’s likely that they already know the value of the documentation, but they may not feel empowered to suggest and make updates. The hands-on experience of a doc sprint gives them that power. The feeling of power lasts long after the sprint has ended.

A doc sprint offers an opportunity for people to meet each other. Technical writers meet engineers and other members of the product team that we may not cross paths with often.

Some things I’ve learned from running doc sprints

These are a few things that have made an impression on me from recent sprints, and some hints that I’ve picked up along the way:

Engineers and other members of the product team appreciate the value of the documentation, and are keen to help improve it.

When deciding which tasks to allocate as suitable for the doc sprint, include some gnarly ones. It’s tempting, as a technical writer, to think that some tasks can be handled only by a technical writer. Well, that is true for some tasks :) but recently I’ve found it’s rewarding to err on the side of “let’s do it”. Big things happen in a doc sprint. Big bugs get squashed with surprisingly little fuss.

As the technical writer, be prepared to spend the entire period of the doc sprint reviewing changes, rather than making changes yourself. The main benefit of getting software engineers and support engineers to fix bugs is that you’re making direct use of their technical and business knowledge. They know the products and systems, and the ways the customers use them. On the other hand, the engineers don’t necessarily know the ins and outs of your documentation system. So, while the facts are probably right in the documentation created during the sprint, you’ll need to tweak the language and the adherence to other documentation standards like content re-use and page structure. It’s best to do that as part of the sprint, so the bugs can be closed off.

Create bug hot lists, to give people priority and focus. A hot list is a collection of bugs of a certain type. Since they’re fairly crucial to the success of a sprint, I’ve dedicated a separate section to hot lists below.

Hold a kickoff meeting at the start of the sprint, to give people information about what they’re doing and how to do it. Keep the kickoff short: 15 to 20 minutes is good. But allocate an hour, in case people have lots of questions.

Create a sprint guide that you can share with the sprint participants. The guide should be short and sweet, including information such as the date(s) of the sprint, the aims, the sprint organiser, the time of the kickoff meeting, the links to the bug hot lists, information on how to update the documentation, and where to send the reviews. Walk through the sprint guide at the kickoff meeting.

If you have the budget, provide food and prizes. For example, cakes at the kickoff, and prizes for most bugs fixed, most scary bug tackled, and so on.

Send out a report on how things are going at the end of the first day, as well as a wrapup after the sprint has ended. Include interesting bits of information such as who fixed the first bug, how many bugs have been fixed so far, and the scariest bug fixed.

More about hot lists

A hot list is a collection of bugs of a certain type. Many bug tracking systems offer a way of creating hot lists, naming them, and allocating bugs to them.

Hot lists are key to the success of a doc sprint where the focus is fixing bugs. When planning the sprint, I spend quite some time devising a set of hot lists that helps define the aims of the sprint, then filling the hot lists with issues. It’s worth it. When the day of the doc sprint dawns, people can get started immediately, even if I’m not there yet. (That last is particularly handy when my day starts five hours after many of the team members’ due to time zones.)

It’s fun to think up some attractive, appealing names for the hot lists. For example, being in Australia, we chose the name Mozzie (mosquito) for the hot list of small, easy fixes. For the big scary bugs, we chose Huntsman (a rather large, strangely beautiful, but admittedly scary, spider). In our most recent sprint, we created a hot list called Product Manager’s Choice (fix these bugs to win a PM’s mark of honour) and another called Technical Sales Engineer’s Choice (fix these bugs to win a TSE’s undying gratitude).

Note that a bug can appear in more than one hot list. For example, a big complex doc request could be a Huntsman as well as a Technical Sales Engineer’s Choice.

Have one master hot list for the sprint, which includes all bugs to be tackled during the sprint. This hot list will be invaluable in tallying up totals when the sprint is over. It’s also a good container for bugs that don’t fit into any of the other hot lists, but which you’d still like tackled during the sprint.

Having hot lists also makes it easier to award prizes based on the hot lists.

More about doc sprints

If you’d like to know more, try some earlier posts on planning and running a doc sprint. The sprints I’ve been involved in recently have focused on bug fixing. In earlier sprints we created entirely new documentation sets.

Bug husks

These are the husks of two cicadas that I spotted while walking in the bush. The bugs themselves have shed their skins and gone on to bigger, better things.

January 8, 2016

Write the Docs San Francisco, January 2016

I’ll be speaking at Write the Docs San Francisco, on Tuesday, January 19th. The topic is “Working with an Engineering Team”. I’ll share some tips that I’ve picked up while working at Google and Atlassian, and open up the discussion for input from the attendees too. This is a great topic, and many people will have varied experiences and best practices to share.

The meetup is at the Splunk offices (250 Brannan St., San Francisco) at 6.30 pm on Tuesday, January 19th. For signup and more details, take a look at the Write the Docs Meetup.

Here’s an outline of my talk, Working with an Engineering Team:

Sit with the team

Grok teamwork and audience

Play with the team

Adopt the team’s methodologies

Get to know the tools

Gather and share information

This will be my first Write the Docs meetup. I’m delighted and excited to meet everyone!

January 1, 2016

How a developer accesses an API

This post is one in my emerging series of API basics from a technical writer’s point of view. How does a developer get hold of an API, so that she can use it in her application?

The other day, I was chatting to folks in our Marketing team about the three essential items of information an API quick-start guide should give developers:

Where to download the API and other tools you need.

Where to get your API key or other required app credentials.

A hello world app or some basic sample code.

During that discussion, I realised that the first item (“download the API”) differs depending on the type of API you’re discussing. It’s not always a case of downloading the API and adding it to your development project. Sometimes you don’t need to download anything – you just send a request. Sometimes the download happens each time your application needs to use the API. And sometimes you download something in your development environment and compile it into your application project.

Before the recent discussion, I’d understood the difference subconsciously, but during the conversation it became clear to me that this is something worth bringing to the fore, especially for those of us who need to document or market APIs. It’s a useful way of becoming more familiar with the types of API that we’re writing about. (If you’d like to know more about the various types of API, take a look at my attempt at a tech writer’s classification of APIs.)

Calling a REST API or other web service API

As a developer using a REST API or other web service API, you don’t necessarily need to download anything. You can simply start sending requests over HTTP and receiving responses from the API, which does all the work on the server (“server side”). In some cases, however, the API developer or the development community supplies client libraries that developers can download to provide the basis for their app’s interactions with the API. Examples are the Flickr client library for .NET, the Twilio client libraries, and the client libraries for the Google Maps web services.

Importing a library-based API

For a library-based API, you need to import a library of code or binary functions into your development project (your application). Then you can use the functions and objects in your code. When using a JavaScript API, for example, you get the API by including a documentation

For an Android API, you install the Android SDK and then add any additional SDK packages into your development project, within your IDE. (An IDE is an integrated development environment, such as Eclipse or IntelliJ IDEA.) In this case, the API download happens when the developer builds their application. See the Android documentation on installing the SDK and additional packages. The Google Maps Android API, for example, is one of a number of APIs distributed via the Google Play Services SDK, which is one of the packages described in the above link.

Downloading a flowerRecently encountered in my neighbourhood: This sulphur-crested cockatoo is importing a flower recently downloaded from a bottlebrush tree. :)

November 23, 2015

3 essentials in an API get-started guide

Developers may need to hook their application up to an API so that the app can get data from somewhere, or share data with another app, or request a service such as displaying a message to the user. The getting-started guide is one of the most important parts of an API documentation set. Often the developer can find their way around an API with just the getting-started guide and the reference documentation.

A getting-started guide for an API (Application Programming Interface) helps a developer get their application interacting with the API.

At a minimum, a getting-started guide tells developers how to:

Download any tools required, such as an SDK (Software Development Kit) or a code library.

Get any necessary authentication credentials for their app, such as an API key.

Fire up a hello world app. This is a program that does very little. Typically, it prints “hello world” to a web page, a screen, or the developer console. The purpose of a hello world app is to make sure the developer has all the tools and configuration required before they can start developing.

Here are some examples of API getting-started guides:

Google Maps JavaScript API

Google Maps Android API

Google Places API for iOS

GitHub API

Heroku Platform API

eBay

Interestingly, if you examine API documentation on the Web, you’ll come across a few different types of guides called “getting-started guides” or “quick-start guides”. It’s an overloaded doc type. :) For example, some quick-start guides take the form of a tutorial, leading developers through a simple use case for the API. The resulting app is something more than a hello world app, and is useful for developers who need information about what the API does (typical use cases) as well as the authentication and setup steps.

November 19, 2015

Top writing tip – go for a walk

You know that feeling when you’ve written yourself into a corner in your blog post, presentation, thesis, or another type of document? Here’s a tip that’s helped me often to get past the corner: Go for a walk!

Take an energetic stroll. In the bush, on the beach, whatever suits you. Don’t consciously think about the problem in your document. If your brain comes up with a thought, toy with that thought in a semi-interested manner. Follow where it goes. Be open to its consequences even if they involve throwing away an entire section of your presentation, redoing some research, changing the direction of your thesis.

The thing is, your subconscious is probably right. Often, it’s bringing to the surface a feeling that you’ve had for a while. That niggling worry that something’s not quite right with the document, but you haven’t had time to go down the rabbit hole of investigation, or are perhaps too timid to follow the White Rabbit to an unknown world of randomly shrinking and expanding presentations. :)

While you’re on the walk, write yourself a note about your musings. Right then and there, in the bush or on the beach. I send myself emails, sometimes a series of them. A note on a scrap of paper would do too. Make sure you capture the actual words of your thoughts, because they encapsulate the insight that you’ve come to.

When you get back to your desk or your computer, save your work in its current state. Then remodel it, based on your new insights.

This happened to me recently. I’d mapped out a presentation then spent weeks working on its separate sections. A couple of days ago I read through a section I’d planned a while ago, which I’d thought would be the centre piece of the presentation. Oh no, it sounds out of place, uninspired, weird even. How can I adapt the rest of the material so this section works?

I went for a walk, watched the birds, admired the budding trees, wrote myself some emails. The end result was that I removed the worrisome section and integrated some of it into the rest of the presentation. The entire concept of the document had developed and moved beyond its erstwhile centre piece.

It’s a bit like those fictional characters who take a story in directions the author hadn’t originally designed.

I took this picture (above) at Snoqualmie Falls, near Seattle WA.

November 6, 2015

Excited about tcworld India 2016

I’m delighted that I’ll be attending tcworld India 2016, on 25-26 February in Bangalore. This is an annual conference organised by tekom Europe and TWIN (Technical Writers of India). Let me know if you’re planning to come!

This will be my first trip to India, and of course my first time at tcworld India. I was lucky enough to attend the related tcworld conference in Europe in 2012, where I learned a lot, met many technical writers, and caught up with friends I’d previously met only online. I’m expecting tcworld India to be at least as great. :)

At the moment, I’m having fun putting together my two presentations for the conference. I’ve been invited to give the keynote at the beginning of the conference, which is a huge privilege. In addition, my proposal was accepted to present a session on API technical writing.

Keynote: The future *is* technical communication

Preparing the keynote presentation in particular is a lot of fun. I’m exploring the march of technology, the way we deal with it, and in particular how it’s affecting the way we communicate. Here’s the introduction:

Over the past few years there’s been quite a bit of discussion about the future of technical communication. Now let’s look at the world in a different light:

The future *is* technical communication.

People’s understanding of the world is based on technical communication, and getting more so by the minute… (join me at tcworld India to hear the rest!)

Later presentation: API technical writing

Later in the conference I’ll speak about APIs and API documentation. APIs are a hot topic in our field, and technical writers with the skills to document them are in high demand. Have you ever wondered what API technical writers do and how they go about it? I’ll demonstrate some easy-to-use APIs, examine examples of API documentation, and give some ideas on getting started in this exciting and rewarding area of technical communication.

The conference program for tcworld India 2016 is looking good. I’m looking forward to meeting the speakers, organisers and attendees. And I’m looking forward to exploring Bangalore!

October 24, 2015

What is an API client library?

Client libraries are sometimes called helper libraries. What are they and how do they help developers use an API?

Over the past year I’ve run a few workshops on API Technical Writing. Part of the workshop content is about client libraries, and I decided it’s worth discussing this topic in a blog post too. It’s of interest to technical writers who are documenting APIs, particularly web services and REST APIs.

What is a client library?

A client library, sometimes called a helper library, is a set of code that application developers can add to their development projects. It provides chunks of code that do the basic things an application needs to do in order to interact with the API. For example, a client library may:

Provide boiler-plate code needed to create an HTTP request and to process the HTTP response from the API.

Include classes that correspond with the elements or data types that the API expects. For example, a Java client library can return native Java objects in the response from the API.

Handle user authentication and authorisation.

How is that useful?

Looking at the developer who’s using the API: With a REST API or any web service API, the developer could be using any of a number of programming languages to make the API calls.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could give them some code in their own language, to help them get started with the API? That’s what a client library does. It helps to reduce the amount of code the application developers have to write, and ensures they’re using the API in the best supported manner.

Examples of client libraries

In some cases, the API developers provide client libraries for the API. In other cases, client libraries are developed and supported by the community rather than the API developer.

For example, here are the Flickr API client libraries listed by programming language, all maintained by the developer community:

flickr-net for .NET

flickgo for Go

flickrj for Java

flickcurl for C

node-flickrapi for Node.js

Here are more examples of client libraries, listed per API:

Twilio API (an impressive number of client libraries)

Google Calendar API

Google Maps web services

Is a client library the same thing as an API?

No, although they’re closely related. My post on API types describes library-based APIs, which are libraries of code that developers need to import before they can use the API. So, how does that differ from a client library?

Here’s how I see the difference between library-based APIs and client libraries:

Library-based APIs are those where the developer needs to import or reference a library of code or binary functions before the application can interact with the API. For example, the documentation for the Google Maps JavaScript API describes the HTML

Client libraries are additional libraries of code that are provided to make a developer’s life easier and to ensure applications follow best practices when using the API. In general, you can call the API directly without using the client library. (In some cases, though, the client libraries may be the preferred or even the only supported means of interacting with a particular service.)

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this topic – does the above summary make sense, is it useful, and what have I left out?

September 29, 2015

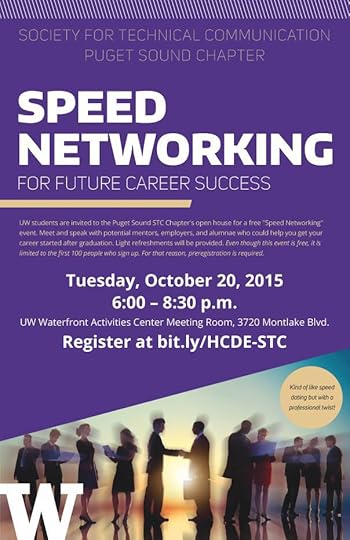

Inviting Seattle tech comm students to speed networking and workshop

The Puget Sound Chapter of the Society for Technical Communication (STC) is hosting a “speed networking” session at the University of Washington at 6pm on Tuesday, October 20th. I’m delighted to say that I’ll be there too.

In addition, you’re invited to an API Technical Writing Workshop that I’m running in conjunction with the STC on Friday, October 23rd. It’s open to students as well as people already in the tech writing field. See the details here.

So, that’s 2 tech comm events in one week – an opportunity not to be missed. :)

Quick registration links:

Register for the speed networking event: http://bit.ly/HCDE-STC

Register for the workshop: http://goo.gl/FYqCzf

Here’s the poster the STC shared with me, for the speed networking event:

Random remarks from me:

I like the spelling of “alumnae”. At first I thought, “Gah, typo!” Then I realised it’s a thing.

The purple colour is awesome. It matches my Ubuntu background!

I hope to meet many students and other Seattle tech comm folks at the networking event and at the workshop!

August 29, 2015

Seattle workshop on API Technical Writing

Will you be in Seattle on Friday, October 23rd? Join me and the Puget Sound Chapter of the STC for a full-day workshop on API technical writing. It’s free, and there’s free food too. :)

Anyone interested in learning about API technical writing is welcome to attend – you don’t need to be a member of the STC.

Quick links: Register to attend, and learn more on the STC Puget Sound site.

What is API technical writing?

API stands for Application Programming Interface. Developers use APIs to make apps that communicate with other apps and software/hardware components. API technical writers create documentation and other content that helps developers hook their apps up to someone else’s API.

For a tech writer, it’s an exciting, challenging and rewarding field. I love it!

This workshop gives you hands-on experience with APIs and API documentation, insight into the demands of the role, and plenty of information for your own follow-up study.

Workshop details

Date: Friday, October 23rd, 2015

Time: 9am to 4pm – breakfast and setup are at 9am, for a start at 9:30 sharp

Instructor: Sarah Maddox – that’s me ;)

Cost: None. The workshop is given free of charge.

Location: Google Offices, 601 N 34th Street, Seattle, WA 98103. (Link on Google Maps.)

This is a practical course on API technical writing, consisting of lectures interspersed with hands-on sessions where you’ll apply what you’ve learned. The focus is on APIs themselves as well as on documentation, since we need to be able to understand and use a product before we can document it.

The workshop includes the following sessions:

Lecture: Introduction to APIs, including a demo of some REST and JavaScript APIs.

Hands-on: Play with a REST API.

Lecture: JavaScript essentials.

Hands-on: Play with a JavaScript API.

Lecture: The components of API documentation and other developer aids.

Hands-on: Generate reference documentation using Javadoc.

Lecture: Beyond Javadoc – other doc generation tools.

Lecture: Working with an engineering team

Preparation for the workshop

Please take a look at the prerequisites and setup to see what you need to install on your laptop before the workshop. Doing the recommended installations will save you a lot of time at the workshop so that you can avoid missing crucial bits when you’re there.

Hope to see you there!

Here’s that signup link on Eventbrite. I hope to see you there!

Slide from lecture – working with an engineering team:

August 14, 2015

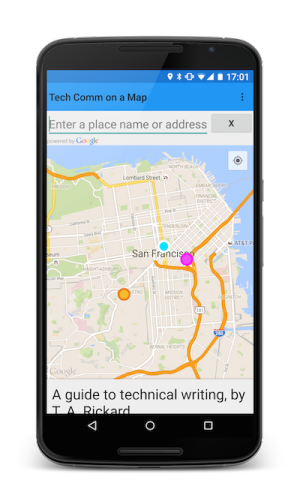

Fledgling Android app for Tech Comm on a Map

I’m very excited, because there’s an Android app on its way for Tech Comm on a Map. The Android app uses the same data source as the Tech Comm on a Map website – so you can see the same events on the map in both apps. In addition, you can add events to the map directly from within the Android app, and it does smart marker clustering too.

Tech Comm on a Map puts technical communication titbits onto an interactive map, together with the data and functionality provided by Google Maps. It’s already out there on the Web. See it in action on the Tech Comm on a Map website, and read more on this page.

And now the Android app

The code for the Android app is already on GitHub. A group of us got together during a hackathon and created the initial version of the app. I’ve added to the app since then, and intend to continue improving it. Eventually I’d like to add it to the Google Play store. There’s a bit to do before that. :)

Friendly disclaimer: Although I work at Google, this app is not a Google product. It’s a personal project by me and the other contributors.

The Tech Comm on a Map app for Android is developed with Java and the Android SDK. It uses the following APIs:

Google Maps Android API

Google Places API for Android (Autocomplete and Place Picker)

Google Play services Fused Location Provider (Get Current Location)

Google Apps Script

Realm.io (a mobile database)

AndroidSlidingUpPanel (a draggable sliding-up panel)

Android Saripaar (a validation library):

If you’re interested in developments, follow the Tech Comm on a Map app for Android on GitHub. You can build it from the source and load it onto your Android device to try it out. It works. :)