Sarah Maddox's Blog, page 16

July 29, 2016

Eliminating the zombie vulnerability – removing passive voice from the docs

If you can insert the words “by zombies” into a sentence, then that sentence very likely uses the passive voice. A colleague recently reminded me of this tip. It made me laugh, and so I thought it’s worth blogging about. If only to share the chuckle.

Here are some examples of zombie-infested sentences, and their equivalents using active voice.

Example 1

Geographic requests are indicated by zombies through use of the coordinates parameter, indicating the specific locations passed by zombies as latitude/longitude values.

Converting passive voice to active:

You can use the coordinates parameter to indicate geographic requests, passing the specific locations as latitude/longitude values.

For an even more concise effect, use the imperative:

Use the coordinates parameter to indicate geographic requests, passing the specific locations as latitude/longitude values.

Example 2

Latitude and longitude coordinate strings are defined by zombies as numerals within a comma-separated text string. For example, “40.714,-73.998” is a valid value.

Converting passive to active imperative:

Define latitude and longitude coordinates as numerals within a comma-separated text string. For example, “40.714,-73.998” is a valid value.

Why eliminate the zombie vulnerability?

Active voice is more concise than passive voice. It’s usually easier to understand.

To me, the most important point is that active voice makes it clear who’s responsible for what. Putting zombies aside, if you use the passive voice your readers may think that the nebulous “system” may do the thing you’re talking about.

Who does what, in this example?

The API can return results restricted to a specific type. The restriction is specified using the types filter.

Answer: The developer has to specify the types in the types filter. I don’t think that’s clear, though, when reading the text. Often the context makes it clear, but not always. Zombies lurk in the shadows, ready to grab the unsuspecting reader.

The distinction between active voice and imperative mood

In the above examples I’ve pointed out the difference between active voice and imperative mood. In technical writing, both are good. The imperative mood is particularly concise and clear, but in some cases it can come across as too abrupt.

Should we ever invite zombies in?

I think there are times when passive voice is OK, or even a good thing. Sometimes a sentence sounds artificial if you attempt to inject a subject. Sometimes the passive wording is a well known phrase that readers will accept and understand more easily than the equivalent active phrasing. For example, what do you think of this wording?

These community-supported client libraries are open-sourced under the Apache 2.0 License and are available for download and contributions on GitHub. The libraries are not covered by the standard support agreement.

July 26, 2016

Stack Overflow’s documentation should be called samples

I’m thinking “documentation” is a misnomer for Stack Overflow’s new feature. “Samples” would better convey the feature’s purpose and form. A topic is basically a code sample (or a few code samples) with metadata (title, tag) and comments.

Calling it “documentation” led me to expect more of it. I looked for such things as navigation aides, a way to order topics in logical sequence rather than by date/popularity, and more control over the hierarchy of concepts.

I love the idea of sample-driven documentation, but I don’t think the Stack Overflow platform offers it yet.

For background, see my earlier posts: What does Stack Overflow’s new documentation feature mean for tech writing? and Information architecture of Stack Overflow’s documentation feature.

July 23, 2016

Information architecture of Stack Overflow’s documentation feature

A couple of days ago I pondered on the effect Stack Overflow’s new documentation feature may have on technical writing. Now I’ve taken a closer look at what goes into a topic and how topics are organised.

At first I found Stack Overflow’s documentation feature a little confusing, both as a reader of the docs and as a potential contributor. I thought the organisation wasn’t “intuitive”, by some definition of intuitive. A deep dive has helped me understand the structure offered by Stack Overflow as a documentation platform. It’s less complex than I’d expected. That’s probably why I couldn’t grok it at first!

TL;DR: Topics are grouped under a tag, such as “CSS” or “Java Language”. A tag represents something that needs documenting. The subject of the tag can be as big or as small as you like – or rather, as big or as small as the community likes. Topics are linked together by the tag and by hyperlinks.

What does a topic look like?

When you create a topic, Stack Overflow offers you an outline to fill in. A topic has the following parts:

Topic title

Examples – that is, code samples

Syntax – a place to call out the most important bits of the code, particularly signatures

Parameters – that is, method parameters

Remarks – anything that doesn’t fit into the above sections

Here’s a screenshot showing the first few parts of a new topic, titled “Find directions”, in edit mode. There’s some useful contextual help for the topic author.

I like the fact that code comes first, given that the products being documented are developer products such as APIs and SDKs. On Stack Overflow, the audience consists of developers. A good code sample gives developers context and is often all the developer needs to be able to use the product.

On the other hand, it’s interesting that the “remarks” section is right at the end of the topic, and that it’s called “remarks” rather than something a little more weighty or alluring. Even the ubiquitous “more information” would convey… well, more information about what this section is intended to contain.

Code samples are great, but developers often do need other types of information: conceptual content such as an introduction, typical use cases, overviews, best practices, and more.

How do people tie topics together?

How do readers get a complete view of the entirety of a particular subject on the Stack Overflow documentation platform? Actually, taking a step back, I find myself wondering what that “entirety” might be. It’s up to the community to define the size of the things that are documented, and how those things fit in with other things, big or small.

Documentation is attached to tags on Stack Overflow. These are the same tags as are used for the original Q&A part of Stack Overflow. The tag is the primary mechanism for organising topics. For example, the classic Stack Overflow has a “CSS” tag with tagged questions, and now with tagged documentation topics too.

Note that there’s also a more specific set of CSS3-tagged questions and CSS3 documentation topics, and indeed many other CSS-related tags.

For each tag, you can see the set of available topics on the “all topics” tab, like this list of topics for the CSS tag:

As a reader, you can order the topics by popularity or by date last modified.

There’s an overview topic for each tag, which in this case is titled “Adding CSS to a Document“:

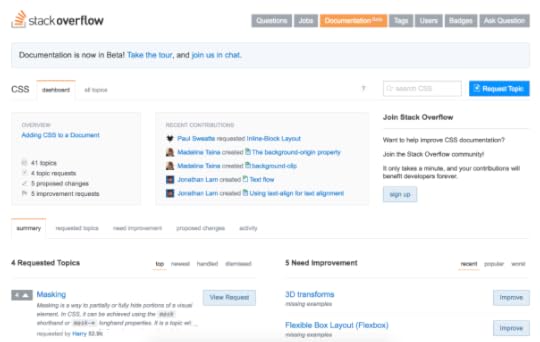

Each tag also has a dashboard, which shows requests from the community and changes that need reviewing. If you’re a contributor, you can use the dashboard to manage your own activity. Here’s the dashboard for the CSS tag:

As you can see on the dashboard, people can suggest new topics and contribute to existing topics. There are currently 41 topics tagged “CSS”, and 4 requests for new topics. People can also mark a topic as needing improvement.

Getting around the documentation

So, in summary, topics are linked by tags. You can also cross-link within topics, using hyperlinks as is standard in web-based documentation.

The only table of contents is the list of topics on the “all topics” tab for each tag. There’s no other type of navigation, such as a curated left-hand navigation or top-level menu.

As David Vogel remarked, this could lead to interesting new information architecture models. I think there’s room here for Stack Overflow to adapt the new platform in response to the way people are using it. Larry Kunz commented that technical writers can keep an eye on this development to learn more about SEO and findability.

Stay tuned!

What the community thinks of the documentation feature

There’s plenty of discussion, much of it heart-felt, about exactly what documentation should be, and hence what Stack Overflow as a doc platform should look like. Here are a couple of examples:

Sumurai8 discussed the structure of the documentation model: Documentation is not a library, tags are not books

Nicol Bolas suggests A better Documentation model: Task, not Topic

In conclusion

If Stack Overflow has the resources to put into it, they’ll be able to adjust the new documentation platform to suit the needs of the community. As technical writers, we’ll be able to watch and learn. Exciting times.

July 22, 2016

What does Stack Overflow’s new documentation feature mean for tech writing?

Stack Overflow has recently announced the public beta release of its new documentation feature. That is, Stack Overflow now provides a platform for crowd-sourced documentation relating to any number of products, for the people, by the people.

For those of us managing the docs for widely-used products in particular, this means our customers may soon have access to an alternative, crowd-sourced documentation set.

What an awesome experiment for us as technical writers to follow! We’ll be able to see at first hand what our customers know they need, in terms of information about our products. Because this is Stack Overflow, the documented products are likely to be APIs, SDKs, and other developer-focused tools and technologies.

What if the documentation on Stack Overflow turns out to be voluminous and extremely useful – where would that leave us as technical writers working on proprietary doc sets? I think it will give us the opportunity to streamline our content, focusing even more than we do now on ensuring our information is up to date, and that our information architecture is the best we can make it.

In other words, we can ensure our target audiences can find what they need, even when they don’t know yet what that is.

Technical writing is hard. Information architecture is hard. The Q&A side of Stack Overflow works extremely well, because it focuses on short snippets of content that answer a particular question. It’s going to be very interesting indeed to see how well the new documentation feature works, with the more narrative demands of technical documentation.

An issue I foresee is that people will be tempted to kick off a topic, and then tire half way through and end up providing a link to the official documentation. Is that a bad thing? Tech writing know-how says our readers find it disconcerting to have to click around to find their information. It’s OK in a Q&A format, but not so good in a tutorial or step-by-step guide.

I really like Stack Overflow’s focus on sample-driven documentation!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this development. Where do you think it’ll go within the next few months, and how about within the next two years? Will it fizzle into nothingness, or explode into something huge and beautiful? Will the original Q&A form of Stack Overflow merge into the new documentation form, becoming something new?

July 7, 2016

Doc bug fixits – a doc sprint to fix issues

If you’re a tech writer on a fairly typical large documentation suite, your docs probably contain some inaccuracies caused by error, misunderstanding, missing information, or pages going out of date. If you’re lucky, like me, you may have an eager group of developers, engineers, support team members, product managers, and more, who’d love to help fix those bugs. Enter the doc bug fixit, or doc fixit for short.

Over recent months I’ve run a number of doc fixits. It’s been a lot of fun, we’ve fixed some good bugs, and we’ve learned a lot. These tips may be useful to people considering running a fixit themselves.

A doc fixit is an event where technical writers work with engineers and other team members to update the documentation. It’s a type of doc sprint, but one where the aim is to apply small to medium-sized updates rather than add new features. The updates may fix errors in the docs or add missing bits.

Image attribution:

Friendly Purple Ant, by Schade,

from openclipart.org.

Why run a doc fixit?

These are some of the good things that tech writers experience from running a doc fixit:

Fix bugs and improve the docs.

Foster feelings of ownership of, pride in and responsibility for the docs amongst the engineers and other team members.

Share your tech writing and information architecture knowledge with others, and see how appreciative they are of your skills.

Educate people about the process of updating the docs, so they can do it themselves when they discover a small error in future. The process includes sending the doc to the tech writers for review and approval.

Meet people in the engineering and product teams.

Help the engineers see first hand how their code comments end up in the public-facing documentation (that is, the code comments that are formatted for Javadoc or some other doc generation tool, and thus appear in the generated reference docs).

How long should the fixit be?

A fixit can last anything from a few hours to a few days. I’ve found two days to be a good time period. It’s rare for each participant to be able to spend more than half a day on the sprint, and people are often called away unexpectedly to do their “day job”. A period of two days gives everyone a chance to help out, and ensures you get a good number of fixes done.

In particular if you’re working with teams in different time zones, the sprint should extend over at least two days so that people in far-flung offices get the best opportunity to work together on updates.

Things to consider before running a doc fixit

Some strategy never goes amiss:

Consider whether your doc set will benefit from a fixit. Ideally, it should have a reasonably large number of bugs, and a fair number of engineers and other team members who can participate.

Contact the tech leads and managers to explain the purpose of the fixit. Make sure they’re happy for members of their team to participate, and ask them to promote the fixit within their team.

Select the participants based on their product knowledge. If people have already shown an interest in the docs, they’re an excellent choice. Send them personal invitations.

How can you encourage people to take part in the doc fixit?

Motivate the participants:

Set a goal, such as the number of bugs to close.

Suggest that people examine the docs and raise bugs beforehand, so they can fix them in the fixit. That’s a good way for them to get to know the docs, and a good way to put themselves in line for a prize.

If possible, be present yourself at the location where most of the participants will be. It’s amazing and rewarding to see how engineers appreciate having a tech writer on tap.[image error]

Make it competitive. For example, “that other team’s fixit closed 42 bugs – let’s beat that!”

Provide food: pizzas, muffins, whatever your budget allows.

Award prizes. It’s great to have a number of categories, such as the first bug fixed, the most bugs fixed, the most complex bug fixed, and so on. The prizes can be small – it’s the thought that counts. And the fun.

Make sure people feel that the fixit is a well-organised event that will give them good material to add to their resumés.

Create one or more hot lists

Create “hot lists” of bugs that you want fixed. A hot list is a selection of items, in this case bug reports, with a characteristic in common.

For example, you could create the following hot lists:

Quick, easy fixes.

Complex bugs.

Bugs that require specific technical knowledge.

And so on.

Make sure the bugs in the hot lists are suitable for a fixit. For example:

Ideally, the fix should be immediately relevant, and not dependent on a software release. That means people can submit the change and experience the immediate satisfaction of seeing it published during the sprint.

The fix should not require too much tech writer input. So, structural doc changes, for example, are not suitable for a fixit.

Take advantage of the fact that your subject matter experts are suddenly uniquely interested in the documentation. Choose tasks that require intimate knowledge of the product – where you’d have to consult your subject matter experts before you could make the update: corner cases, unexpected behaviour, and so on. In a fixit, it’s often your subject matter experts taking part!

Prioritise small bugs that you’re not finding the time to tackle. An accumulation of small bugs can be as bad as a single huge one, for negatively affecting customer experience.

Supply a fixit guide

Keep it short and simple. Just one page is enough. Include:

The goal of the fixit.

Date and time.

Location of the kickoff meeting.

Links to the hot lists.

A guide on how to update the docs.

How to send the updates for review and approval.

Your contact details.

Hold a fixit kickoff meeting

Put it on everyone’s calendars. Entice people with food.

Say just a few words, telling people about:

The goal of the fixit.

Prizes.

How to participate.

A link to your fixit guide.

How to find you and other tech writers during the sprint.

Go!

Run the sprint

Keep ’em at it:

Issue daily progress reports: tell people the total number of bugs closed so far, the top runners for each prize, any other news items.

Keep the food coming.

Review the incoming doc updates promptly.

Wrap it up nicely

Remember, you’ll probably want to run another fixit. Wrap this one up well, so that you can refer to it in future.

Write a report and share it with everyone involved. Describe:

Results (number of bugs closed).

Participants and prize winners.

Interesting factoids, such as something unexpected that happened, or the first product manager to fix a doc bug ever, …

Thank everyone involved, and don’t forget to hand out the prizes.

May 24, 2016

Write the Docs NA 2016 wrapup

This week I attended Write the Docs NA 2016, which wrapped up a couple of hours ago. This post is a summary of impressions, with links to my notes on some of the sessions I attended.

One thing that strikes me about Write the Docs is that I’ve spent much of my time talking to people. This is partly because half of each day is devoted to unconference sessions as well as formal presentations. In the unconference sessions there’s a facilitator rather than a speaker, so everyone can contribute to the discussion. Another reason I’ve done so much talking to people is that there are so many interesting, friendly, enthusiastic people to talk to.

There were approximately 400 attendees. They’re people who love documentation – that is, people who know its value. Based on a show of hands at the introductory session, approximately 60% of the attendees are technical writers and about 15% are software developers. Others are UX specialists, support engineers, librarians, knowledge management specialists and more.

Another thing that strikes me is that the pre-conference activity was a half-day hike through the forested hills around Portland. Now, that’s my kind of activity.

The sessions

These are the notes I took from some of the sessions I attended:

Interactive document environments

A readable README file

API documentation tools

Values of effective tech writing teams

Internal docs for startups

From tech writing to information experience team

Doc sprints and API doc meetup

On the first day of Write the Docs, we gathered at Centrl Office to write docs and talk about API documentation. It was great chatting to so many enthusiastic, knowledgable writers. People got together and contributed to open source documentation with Mozilla, Google, and more. We filled three rooms to the brim. This photo shows the scene early in the day, before most people had arrived.

Conference venue

Days two and three were at the Crystal Ballroom. What a lovely venue! Here’s the view from the stage looking out across the conference attendees.

A closer view of the murals:

A chandelier:

More about Portland

My travelling bookmark, Mark Wordsworm, has some pictures and words about the city: Lost in Portland, Oregon.

Thanks

A huge thank you to the organisers of Write the Docs NA 2016. This is my first experience of a Write the Docs conference. I’ve wanted to attend for a couple of years, but it’s a long way from Sydney, Australia, to any of the conference venues. This year, everything came together and here I am. It was a great experience, and well worth the trip. Thanks!

From tech writing to information experience team at Write the Docs NA 2016

This week I’m attending Write the Docs NA 2016. The final talk of the conference was by Daniel Stevens, titled “Atlassian: My Information Experience Adventure”. These are my notes from the session. All credit goes to Daniel, and any mistakes are mine.

Summarising the theme of Daniel‘s session:

The process of creating and growing a writing culture which is technically accurate, writes with a human voice, and connects to every other part of the information experience.

Moving from QA to design

Dan talked about the Atlassian tech writing team’s transition from the QA team to the design team, and how this changed everything they knew about technical writing. Shortly after Daniel joined Atlassian, the team started a conversation about tech writing – what it meant to them, what makes it work.

They built a culture where information is considered an essential part of the experience. Daniel emphasises that they’ve only just started, and there’s still a lot to do. The team has expanded to include researchers, developers and designers, sharing skills and learning from each other.

There have been some frustrations. Change is hard. Adopting new ways of thinking is difficult. It can be hard to stay focused on writing great docs, especially now that the tech writers are part of the design team. And it’s become more complex to define the “team”.

The goal is that everyone tells the same story and thus delivers an amazing information experience. The information should come at the right time, in the right place.

Overcoming resistance to change

Dan gave some ideas about how to manage change. The key is to stage the changes, so that people can adjust. Constantly remind people of the value of what you’re doing. Enhance the strengths of every team member, so that they don’t feel that they can’t do what’s being asked of them. Encourage everyone to participate.

And give them all cake!

Making Confluence behave

Design helped the team rethink the way they were doing things. They re-designed the layout of Confluence wiki pages used for documentation, with more white space, better structure. The team uses the Scroll Viewport plugin to implement the design changes. They work with plugin developers, finding and adapting tools to make Confluence do what they need. And the team works with the developers to add new features to the wiki.

What IX (information experience) means to Dan

It’s about a new way of thinking about the information experience. Gather information so you know ahead of time what you need in the docs. Use analytics to gather data and understand what the users are using and how they’re getting from one part of the docs to another.

Work with a content strategist to define the brief – the elements that make great documentation. Use this brief to set direction. Dan also emphasised that we’re all content strategists.

Measure the results of any change – make everything measurable.

Work like designers: card sorting, sparring. Dan described how they hold a live meeting with teams across the world, using Confluence. Then they spar: everyone mentioning one thing they like, one they don’t like, and sparring with each other.

Connect stories: linking from tutorials to blog posts, and back, so that when customers see any information about any product of Atlassian’s, they feel at home. To achieve this, you need to work with every other team: marketing teams, various IX teams, product teams, design teams, engineering teams.

What’s next?

The Atlassian IX team wants to influence “all the things”.

They’ve created an IX toolkit which everyone can use. It includes design guides, content guides, voice and tone, all shared with the entire company. The IX team has contributed to the ADG (the Atlassian Design Guidelines). This year, IX was part of Atlassian’s internal design confluence, and gave one third of the presentations.

Dan’s enthusiasm shone through in this talk. Thanks Dan!

Interactive document environments at Write the Docs NA 2016

This week I’m attending Write the Docs NA 2016. I’ve just attended a fast-paced, exciting session: “Code the Docs: Interactive Document Environments”, by Tim Nugent & Paris Buttfield-Addison. These are my notes from the session. All kudos goes to Tim and Paris, and any mistakes are mine.

Tim and Paris warned us up front that they speak Australian. Suddenly I feel right at home.[image error] They also write books, are academics, train people in coding, and do other stuff. They’ve noticed that we need better linking between the documentation and the code. Otherwise things break too quickly.

What is an interactive document environment?

Interactive document environments put live code and documentation side by side. You can write content and embed code that runs within the doc.

This talk looked at two examples in particular: Jupyter Notebook (formerly known as IPython Notebook) and Swift Playgrounds.

In the Apple environment, before Tim and Paris started using Swift Playgrounds, they noticed that people got lost. People were switching between docs, code, notes, and couldn’t keep up. So Paris and Tim investigated the tools and made up the term, interactive document environment.

The code, the person’s own notes, and the official documentation all in one place.

Core features:

Live code

Pretty formatting

You can add notes

You can add media such as gifs, videos, etc

It’s real code that you can play with

Swift Playgrounds

Swift is Apple’s new language. Paris and Tim think Swift is the bee’s knees. Swift Playgrounds is a core part of Swift. It’s an interactive coding environment, designed for prototyping, learning and experimenting.

To use Playgrounds, download Xcode from the Apple Store.

Playgrounds currently supports basic HTML and Markdown for content development.

Tim and Paris gave a demo of Swift Playgrounds. It was impressive to see how you can embed code and see it execute right on the page.

Swift supports emoji, so of course the demo included emoji.[image error] You can also add pagination, with a “Next” link at the end of the page. The code is running all the time, and you see the output on a panel next to the page.

We also saw Apple’s example, called Newton’s Cradle and UIKit Dynamics, which runs in Xcode. (Apple’s announcement blog post has a screenshot and a link to the downloadable demo as a zip file.) The code is live, so you can change it and play with it.

IPython Notebooks, now Project Jupyter

Project Jupyter is an interactive Python coding environment.

It’s used by O’Reilly Media for project Oriole, a learning environment that blends executable code, data, text, and video.

Tim and Paris showed us Regex Golf with Peter Norvig. (Sign in, scroll down the page, and run the code. Change the code and run it again. It’s worth it.)

To try creating content in this environment yourself, download Jupyter Notebook. (The process is a little tricky.)

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths:

The code and the docs are together, and the code is live. It’s easy to keep them in sync.

You can mix in your own notes. Paris and Tim say it was a real surprise to see how useful people found it, to be able to add their own notes on the docs.

People don’t have to context switch.

Weaknesses:

These environments are new and thus prone to crashing.

They support only Markdown and HTML for content development.

Limited support for languages and frameworks.

No hooks into existing doc tools.

Only really relevant for narrative docs.

Paris and Tim predict that these environments will become more stable and will support more languages and projects. These environments will replace books and articles. There’ll be better support for non-narrative docs. It’s a natural evolution of API guidelines where you give the developers a cURL command to try the API, and even those more advanced docs that supply a button to run the code live.

Thanks Tim and Paris, this was an entertaining and informative talk. Notes and slides will be at lonely.coffee and blog.paris.id.au.

Internal docs for startups at Write the Docs NA 2016

This week I’m attending Write the Docs NA 2016. I’m at a session titled “Move Fast And Document Things: Hard-Won Lessons in Building Documentation Culture in Startups”, by Ruthie Bendor.

Ruthie Bendor‘s session was about strategies for writing internal docs at fast-moving organisations. Ruthie is one of the brave engineers who attended a conference full of tech writers!

Internal tech docs are things like README files and wiki pages, containing instructions for setting up engineering environments, and so on. They’re what we write for our colleagues to enable us to build upon our work. Even our future selves will find this documentation useful.

When you work at a technical startup, saying “that’s not my job” doesn’t work.

Ruthie told us a few stories of how she’d experienced internal docs as a software engineer. A telling example was when Ruthie worked at an agency. In that organisation, most of the programs Ruthie wrote weren’t meant for production – they were demos for customers, to be thrown away after they’d met their purpose. In this case, there was no need to write much documentation. This is in contrast to working on production code and procedures, where docs help the company progress.

Another story was about Ruthie’s first few days at a startup, where there was no internal documentation to help her get started with all the tools and processes. She stumbled through the first tasks of getting code committed, repeatedly having to bother other people when she messed up the code base.

Based on her experiences, Ruthie suggests four steps to writing internal documentation for a fast-moving organisation.

Figure out what’s broken. Don’t guess. Find out what the rest of the organisation thinks is broken, rather than going on your own assumptions. You’re probably wrong! Find out whether the team values tech documentation, and if not, why not. Possible reasons why engineers may not value docs are the belief that internal docs get outdated too quickly, or that all engineers have the same technical background.

Figure out why your organisation cares about fixing its internal technical docs. You may think the docs will make the software last as long as possible, or will help onboard new staff. But these points don’t apply to fast-moving startups. Startups are focused on making the product. Ruthie learned that the people in her organisation value learning from each other. This is why they care about internal docs. What you document and how you document is an expression of your company culture.

Couch your solutions in the organisation’s values. Ruthie says this is hacking in the best sense: how to get the results you want with the tools you have, and not necessarily in the traditional way. Think about videos, weekly show and tells, etc.

Iterate. At every inflection point of the organisation, reevaluate the values, rinse, repeat.

Incidental learning from this session: The “bus factor” is the number of people who can be unexpectedly lost by a project before the project collapses. It’s the number of people who can be hit by a bus without the organisation going out of business.

Thanks Ruthie! This was a fun and informative session.

Values of effective tech writing teams at Write the Docs NA 2016

This week I’m attending Write the Docs NA 2016. One of the sessions I attended is “7 Values of Effective Tech Writing Teams”, by Joao Fernandes. Here are my notes. All credit goes to Joao, and any mistakes are my own.

Joao Fernandes started by saying that success and effectiveness are words without meaning, unless you have a specific goal in mind. So, what’s the goal of tech writing?

Some answers are:

Teach people how to use a product.

Explain complex information in a clear way.

But those goals aren’t ambitious enough, says Joao. There’s something more profound that guides us. Our users don’t want to read the docs. They want to use the product. So Joao proposes the following goal for tech writers:

Help build products that need no documentation.

Given that premise about our goal, these are my notes on the rules that Joao discussed:

Be the CEO of the docs. Define a vision for the docs, communicate that vision to all interested parties, and make sure others follow it. Make sure you schedule time to do strategic work, as finding that time will be difficult otherwise.

Know the market, product and users. Understand the need that your company is trying to fill in the market.

One of the main points of this session is that we need to decide what documentation is required (the answer may be, very little), and where best to put it (the answer may be that the doc is part of the product rather than traditional documentation). Joao suggested we should apply the 80/20 rule when deciding which docs are required.

Another point is that effective tech writers ask “why” all the time.

Effective tech writers use words as tools, in the same way as developers use programming tools. A natural language is an interesting tool, because it allows for the transfer of knowledge from one person to another. Sometimes the transfer doesn’t go too well. We can complement language with other tools, such as diagrams. And we can adapt the language to make it more effective.

Sharing knowledge is also an important part of an effective tech writer’s role. Coach others, and create resources to help new members of the team.

Thanks Joao for a beautifully presented session!