Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 5

September 14, 2023

(32/54) “In the end the king turned against his own friends. One...

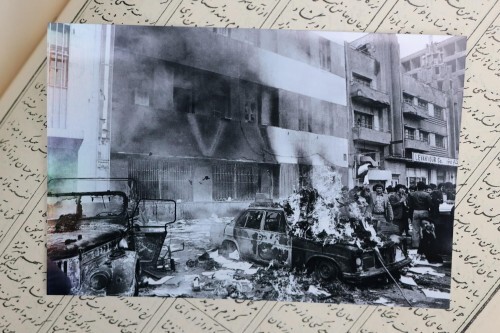

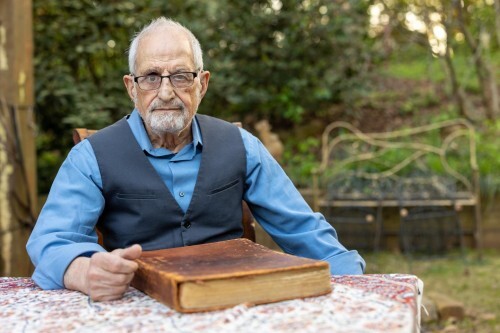

(32/54) “In the end the king turned against his own friends. One day a colleague approached me in the halls of parliament. She was married to a former minister, and the king had just thrown her husband in jail to appease the mobs. She asked me what I thought was going to happen. I answered with a quote from Shahnameh: ‘Tomorrow I will calm your fear.’ Even then I still had hope. I thought we still had time to save the country. But those were the end days. On the Friday after Ramadan there was a huge protest in one of Tehran’s main squares. The army panicked and fired machine guns into the crowd. One hundred people were killed, and that night one hundred fires raged in Tehran. Strikes began to hit the country. Everything shut down: schools, factories, air travel, even the oil industry. The lifeblood of Iran. The country became like a paralyzed man, gasping for its final breaths. In October the king went on television. It would be his final speech to the Iranian people. By then he was suffering-from late-stage cancer. He was a very sick man. He apologized for past mistakes. He said: ‘I am the guardian of a constitutional monarchy, which is a God-given gift. A gift entrusted to the Shah by the people.’ He said that he had finally heard our voice, but it was too late. The people had stopped listening. The king only had one option left.. His generals were still loyal. He still controlled the military, and there were half a million men under arms. He could fight. He could hold onto power, but only if he spilled the blood of Iranians. He had a choice. There’s always a choice to be made. Three months later I was listening to Mohsen Pezeshkpour give a speech from the podium of parliament; he was the founder of the Pan-Iranist party. In the middle of his speech, a messenger handed a note across the podium. He read the note, then over the microphone we heard him ask loudly: ‘Where did he go?’ The crowd let out a gasp. We knew then, the king was gone. The flag had fallen. The day was lost. And there’d be no more role for us to play. That’s the problem with absolute power. It’s like a tent with a single pillar. And when you take out that pillar, everything collapses.”

(۳۲) در پایان شاه به دوستانش پشت کرد. روزی در تالار مجلس همکاری نزد من آمد. دلواپس و هراسان بود. همسرش از وزیران پیشین بود. شاه به تازگی برای دلجویی از شورشیان او را زندانی کرده بود. پرسید: چه خواهد شد؟ با شاهنامه پاسخش را دادم: «من امروز ترسِ تو را بشکنم». حتا در آن زمان هنوز امیدوار بودم. میپنداشتم هنوز زمان برای نجات کشور باقیست. ولی آن روزها، روزهای واپسین بودند. در آدینهی پس از ماه رمضان، تظاهرات بزرگی در یکی از میدانهای تهران برگزار شد. حکومت نظامی شده بود. برای پخش کردن مردم تیراندازی شد، نزدیک به سد تن کشته شدند. آن شب، سد آتشسوزی در تهران به پا شد. اعتصابها در کشور آغاز شده بودند. مدرسهها، کارخانهها و حتا صنعت نفت که شاهرگ کشور بود بسته شدند. کشور زمینگیر شده بود. در ماه اکتبر شاه آخرین سخنرانی تلویزیونیاش را داشت. پیمانی با مردم برای انتخابات آزاد و سپردن کار مردم به نمایندگانشان. از اشتباهات گذشته پوزش خواست. گفت: من حافظ سلطنت مشروطه هستم که موهبتیست الهی که از طرف ملت به پادشاه تفویض شده است. او گفت که صدای مردم را شنیده است. دیر شده بود. مردم گوش نمیدادند. جادوگر جادویشان کرده بود! شاه تنها یک گزینه داشت. هنوز فرماندهی ارتش در دست او بود. ژنرالهای ارتش هنوز به او وفادار بودند. نیم میلیون نظامی زیر فرمانش بودند. میتوانست قدرت را در دست خود نگه دارد، با ریختن خون ایرانیان. همیشه گزینشی هست. سه ماه پس از آن در مجلس در حال گوش دادن به سخنرانی محسن پزشکپور بودم. او پایهگذار حزب پان ایرانیست بود. در میانهی سخنرانیاش، پیامرسان یادداشتی را پشت تریبون مجلس به دست او داد. آنرا خواند، سپس با صدای بلند پرسید: «به کجا میروند؟» آنگاه بسوی مجلس برگشت، و گفت: «شاه از کشور خارج شده است.» حاضران ناباورانه آهی از سینه کشیدند. آنزمان دانستم که دیگر نقشی برای ما نمانده است. شاه رفته بود. پرچم بر خاک افتاده بود. نبرد از دست شده بود. مشکل خودکامگی این است: چادریست که بر یک ستون ایستاده است، ستون را که برداری - همه چیز فرو میریزد.

(31/54) “One of Dr. Ameli’s first acts as Minister of...

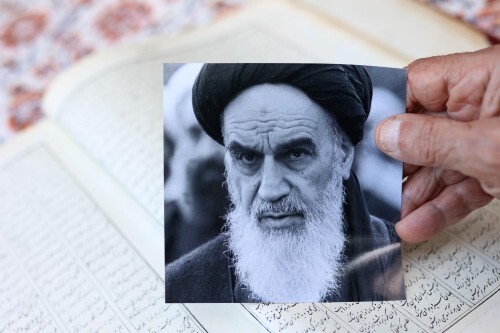

(31/54) “One of Dr. Ameli’s first acts as Minister of Information was to bring cameras and microphones into parliament. For the first time ever, our speeches would now reach the ears of ordinary Iranians. During the first recorded session I gave a speech. I spoke about the same things I always spoke about. I spoke about 𝘥𝘢𝘢𝘥. About every Iranian getting their fair share. I spoke about 𝘢𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. About every Iranian having the chance to participate in the future of their country. For the next week our phone at the house rang off the hook. People were calling me to thank me for my words, people I didn’t even know. But by then it was too late. Khomeini had grown too powerful. So much of the country had received their political education in mosques. They viewed him as a savior; they thought a true Islamic revolution was coming. Opposition groups could sense the wave building, and they rushed to align themselves with Khomeini. They thought that they could mix in their own ideology with his views. They thought they’d be able to ride the dragon’s back, and direct his fire. Even many of the liberal groups were siding with him. Khomeini had been giving interviews. He was telling reporters that he wanted a democracy. He was saying that he would protect the rights of women, and people believed him. He would later claim that Islam allows lying during times of war. One week a rumor spread across the country that Khomeini’s face would be visible in the next full moon. Hundreds of thousands of people went to their rooftops. And hundreds of thousands of people, even educated people, reported seeing his face. On Ramadan nearly a million people marched in Tehran against the king. Our house was on one of Tehran’s main boulevards, so I stood in the doorway to watch the crowd pass. Many were students. They were joyful. They thought that freedom was finally coming to Iran. But the crowd was also filled with young religious men. They were dressed all in black. They would take a few steps, kneel, pray, and then they would rise and do it again. It was like a river, moving in one direction. And Iran was a leaf, floating on top.”

از نخستین کارهای دکتر عاملی در جایگاه وزیر اطلاعات و جهانگردی آوردن دوربین و میکروفون به مجلس بود. اکنون برای نخستین بار صدای ما به گوش مردم ایران میرسید. من در نخستین جلسهی ضبط تلویزیونی سخنرانی کردم. از موضوعهایی سخن گفتم که همواره آنها را بیان میکردم. از داد سخن گفتم. که هر ایرانی سهمی عادلانه داشته باشد. از آزادی گفتم. که هر ایرانی امکان مشارکت داشته باشد در ساختن کشورش. یک هفته پس از آن تلفن خانهیما بیوقفه زنگ میزد. مردمی که آنها را نمیشناختم از سخنانم قدردانی میکردند. ولی دیگر دیر شده و بر قدرت خمینی افزوده شده بود. بسیاری از مردم کشور آموزش سیاسی خود را در مسجدها گرفته بودند. آنها کورکورانه در خمینی یک منجی میدیدند. مخالفان شاه احساس کردند که موجی در حال شکل گرفتن است و برای پیوستن به آن شتاب میکردند. میپنداشتند که میتوانند عقیدههایشان را با نظرات او بیامیزند. گمان میکردند که میتوان بر پشت اژدها سوار شد. در این خیال بودند که میتوانند آتش او را به جایی که میخواهند ببرند. لیبرالها هم با او همگام شده بودند. خمینی در مصاحبهها به خبرنگاران میگفت که خواهان دمکراسی است، از حقوق زنان دفاع خواهد کرد. مردم او را باور میکردند. او بعدها ادعا کرد که در اسلام دروغ گفتن در هنگامهی جنگ مجاز است. شایعهای در کشور پخش شد که چهرهی خمینی در ماه پیداست. هزاران تن به پشتبامها رفتند و او را در ماه دیدند. خبرش در صفحهی نخست روزنامهها چاپ شد! در پایان ماه رمضان بسیارانی در تهران بر ضد شاه تظاهرات کردند. فضا آکنده از فریادهای «مرگ بر شاه» شده بود. خانهی ما در یکی از بلوارهای اصلی تهران قرار داشت، از این رو در آستانهی در ایستادم تا حرکت جمعیت را تماشا کنم. بسیاری دانشجو بودند. شادمان بودند. باور داشتند که سرانجام آزادی به ایران میآید. ولی بیشتر آنان مردان جوان مذهبی بودند. سیاهپوش. گامی چند برمیداشتند، زانو میزدند، سر به سجده میگذاشتند، بلند میشدند و این کار را تکرار میکردند. مانند رودخانهای بود روان و ایران چون برگی شناور بر آب

(30/54) “We were at the eighteenth birthday party of our...

(30/54) “We were at the eighteenth birthday party of our daughter Ahang when we learned that a crowded movie theater had been set on fire in the town of Abadan. The arsonists had locked the exits from the outside, and four hundred people were killed. It was the largest act of terrorism in the history of Iran. Later it would be discovered that the arsonists were religious fanatics. But Khomeini was able to convince much of the country that the fire had been started by SAVAK, at the order of the king. The riots continued to grow. And the king began to panic. He called for the formation of a new government and fired his ministers. He wanted to replace them with upright people. People who could inspire confidence. People who could not be corrupted. And there was one member of parliament that was trusted most of all. He lived in a simple house. He drove a beat-up car. Nobody could question Dr. Ameli’s integrity. The king asked him to join the new administration as Minister of Information. In his new position he would be responsible for investigating the Abadan fire. If he discovered something that implicated Khomeini, I knew he would become a marked man. I drove to his office. I begged him to turn down the position. I told him: ‘Things have become too dangerous. Let’s stay low, let’s keep in our bunker. Once things have calmed down, we can reemerge. We can take a stand and make our case to the people.’ Thirty years earlier we had sworn an oath, to give our lives for Iran. The years had changed him in so many ways. There was white in his hair now. He was a respected leader. He’d written and spoken on every facet of Iran’s society and history. His thoughts had evolved. His policies had evolved. But his ideals had never changed. Every choice he made, he made for Iran. Every choice. He listened politely while I made my case. He knew. Deep in his heart he knew. He knew even better than I did. If something happened to the king, he was done. He’d have no protection. He’d have no support. But he had already made his decision. He was going to serve.”

ما سرگرم جشن هجدهمین زادروز دخترمان آهنگ بودیم که دریافتیم سینمای بزرگی در شهر آبادان به آتش کشیده شده است. آتشافروزان درهای خروجی را از بیرون قفل کردند، و بیش از چهارسد تن را سوزاندند. این بزرگترین کار تبهکارانهی تروریستی در تاریخ ایران بود. دیرتر آشکار شد که آتشافروزان از تندروهای مذهبی بودند. خمینی و یاران تبهکارش به سادگی توانستند به بسیاری بباورانند که آتشسوزی کار ساواک بوده است و به فرمان شاه. پیروانش بیش از پیش خشمگین شدند. شورشها رو به فزونی بود. شاه ترسیده بود. نخست وزیر را برکنار کرد و دولت جدیدی سر کار آمد. میخواست دولتی درخور اعتماد مردم باشد، دنبال درستکردارانی میگشت که به عنوان وزیر خدمت کنند. کسانی که آلوده به فساد نبودند. آنانی را که به درستی شهرت داشتند. دکتر عاملی پزشکی توانا، استاد دانشگاه و نمایندهی مجلس بود که در خانهای ساده به سادگی میزیست و خودروی فرسودهای را میراند. مردی ستودنی بود. شاه از او خواست که به دولت جدید به عنوان وزیر اطلاعات و جهانگردی بپیوندد. در آن جایگاه وی سرپرست بررسی حادثهی آتشسوزی سینما رکس آبادان بود. او بود که باید تبهکاران را پیدا کند و چنین کاری جانش را در خطر میانداخت. هنگامی که شنیدم به او چنین پیشنهادی شده است به دیدنش رفتم و نگرانیام را یادآوری کردم و گفتم بهتر است که ما در سنگر خود بمانیم. سی سال از سوگندی که در همراهی با او برای جان باختن در راه ایران یاد کرده بودم، میگذشت. موهایش اندکی به سپیدی گراییده، گرانمایهای ارجمند بود. دربارهی تمامی زمینههای جامعه و تاریخ ایران نوشته و سخنرانی داشت. اندیشهها و سیاستش پختهتر شده و آرمانهایش همچنان استوار و پا بر جا بودند. هر تصمیم و گزینشش برای ایران بود. او به سخنانم با ادب و بزرگی همیشگیاش گوش داد. میدانست، در ژرفای قلبش میدانست که اگر سلطنت شاه به خطر افتد، کار او نیز تمام است. از من بهتر میدانست که دیگر پناهگاهی نخواهد داشت. ولی او راهش را برگزیده بود. باید خدمت میکرد.

(29/54) “The riots began in Qom. One day Khomeini gave a speech...

(29/54) “The riots began in Qom. One day Khomeini gave a speech saying that the moment had arrived for a true Islamic revolution. And that it was the duty of all Muslims to oppose the monarchy. The rioters targeted anything they deemed anti-Islamic: cinemas, liquor stores, shops selling Western clothes. When the police tried to crack down, a few of the rioters were killed. Khomeini declared the men to be martyrs, and forty days later a public memorial was held. Huge crowds came out. And the rioting began again. It was as constant as the beat of a drum: riots, deaths, memorial. Riots, deaths, memorial. Every forty days there would be another wave. And with every wave the destruction would grow. Eventually the riots spread to the capital. Many mornings I would walk to parliament because the traffic was so bad. One morning I was forced to take a different route entirely, because rioters were destroying a liquor store. They were breaking hundreds of bottles in the street, and the gutters were filled with liquor. My colleagues in parliament were nervous, but I was optimistic. I thought this might even be an opportunity for us. Our entire careers we’d been in the opposition. We often spoke against the king’s policies. Now the people were mobilized. They were in the streets. They were looking for an alternative. Maybe this would be the moment that the king would finally hear the voice of the people. Maybe this would be the moment for us to have a true constitutional monarchy. Khomeini wanted to bring Iran back to the dark ages. But I knew that Khomeini didn’t represent the Muslims of Iran. Iran had been Islamic for one thousand years. We were the nation of Rumi. The nation of Hafez. These fanatics did not represent our religion. I even gave a speech from the podium of Parliament where I quoted the Koran. It was the words of Allah: ‘Those who are furthest from evil, are closest to me.”

شورشها از قم آغاز شد. خمینی در سخنرانی خود گفت که زمان برای انقلاب اسلامی واقعی فرا رسیده است. وظیفهی همهی مسلمانان است که ضد سلطنت به پا خیزند. شورشیان آنچه را غیراسلامی میپنداشتند هدف میگرفتند: سینماها، فروشگاههای مشروبات الکلی، فروشگاههایی که لباسهای غربی میفروختند. در تلاش شهربانی برای خاموش کردن شورشها، شماری ازشورشیان کشته میشدند. خمینی کشتهشدگان را شهید میخواند. چهل روز پس از آن، مراسم یادبود برگزار میشد و جمعیت زیادی در آن شرکت میکردند. مانند کوبش پیاپی طبل صحنهها تکرار میشد: شورش، مرگ، سوگواری. شورش، مرگ، سوگواری. هر چهل روز موج تازهای به راه میافتاد. و با هر موج تازه ویرانیهای بیشتری. سرانجام شورشها به تهران کشید. بیشتر صبحها پیاده به مجلس میرفتم زیرا ترافیک بدی بود. یک بار مجبور شدم راهم را تغییر دهم چون شورشیان در کار تخریب فروشگاه مشروبات الکلی بودند. آنها بطریها را در خیابان میشکستند و در جویها میریختند. همکاران من در مجلس نگران بودند، من هنوز خوشبین بودم. شاید فرصتی باشد. بسیار پیش آمده بود که ضد برخی سیاستهای کشور سخن گفته بودم. بودن مردم در خیابانها روزنهی امیدی بود که سرانجام به پادشاهی مشروطه برسیم. تلاش میکردم گروه کوچک همفکرانم را در مجلس آسودهخاطر سازم. میدانستم که خمینی نمایندهی مسلمانان ایران نیست. هزار سال از اسلامی شدن ایران میگذشت. ما ملت مولانا بودیم. ما ملت حافظ بودیم. این تندروان نمایندهی دین ما نبودند. حتا در یک سخنرانی در مجلس نقل قولی از قرآن آوردم. گفتم: کسانی برای خدا گرامیترند که از بدیها دورترند

(28/54) “The king loved Iran. And I believed him when he claimed...

(28/54) “The king loved Iran. And I believed him when he claimed that it was his dream to have a more open society one day. With a truly free press. And truly free elections. But he didn’t think Iran was ready. It was fear. So many foreign powers were trying to control Iran. The country was full of spies. He’d already survived two assassination attempts, and he saw enemies everywhere. I never viewed myself as an enemy of the king. There was only one thing I wanted. It was the same thing I’d wanted since I was a little boy, when I saw him for the first time. When I touched his coat. I wanted him to be a good king. I wanted him to respect the constitution. I wanted him to involve the people, and hear our voice. On the day of his visit I was excited to welcome him to Nahavand. I wanted to show him that we were trusting the people to make their own choices, their own decisions. I arrived early to the airport. The king’s handlers explained how the welcoming ceremony would proceed. I was to stand on the tarmac about fifty meters from where the king’s helicopter was supposed to land. He would speak to me first. And then he would go on to speak to a crowd of dignitaries gathered behind me. I walked out to my assigned spot. I was out there all alone, with a crowd of fifty people watching. I had my quote from Shahnameh ready. It’s from the moment that Rostam welcomes Prince Esfandiyar. He says: ‘𝘉𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘰𝘯𝘦. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘦𝘰𝘱𝘭𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘐𝘳𝘢𝘯, 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘨𝘶𝘢𝘳𝘥𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘧𝘶𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦.’ When the helicopter landed, the king stepped out. He gave a quick salute to his military escort. And then he began to walk my way. I had my words ready, but I did not get to speak them. He did not stop. He did not slow down. He didn’t even look me in the eye.”

(۲۸) شاه عاشق ایران بود. میگفت میخواهد روزی جامعهی ایران آزاد باشد با رسانههای آزاد. انتخاباتی به راستی آزاد و من او را باور داشتم. ولی بر آن بود که ایران هنوز آماده نیست. ترس بود. قدرتهای خارجی بسیاری در تلاش برای کنترل ایران بودند. شاه تا آن زمان از دو سوءقصد جان به در برده بود. دشمن را همه جا میدید. من هرگز دشمن پادشاه نبودم. تنها یک چیز میخواستم. همان چیزی که در زمان کودکی، روزی که او را دیدم، آن روز که کت او را لمس کردم، میخواستم. میخواستم شاه خوبی باشد. میخواستم که به قانون اساسی احترام بگذارد، میخواستم که مردم را در کارها شریک کند و صدایمان را بشنود. مشتاقانه چشم به راه ورودش بودم. میخواستم به او نشان دهم که میتوان مردم را مشارکت داد و به تصمیمگیریهایشان اعتماد کرد. در روز بازدید او از نهاوند به محل فرود هلیکوپترش رفتم. مدیران تشریفات شاه مرا به فاصلهی پنجاه متر از جایی که قرار بود هلیکوپتر فرود آید، راهنمایی کردند. به من گفتند که شاه نخست با من گفتوگو میکند، سپس به ملاقات با دیگر سرکردگان و نمایندگان گروههای مختلف و بانوان شهر خواهد رفت. من به جایگاه تعیین شدهام رفتم و ایستادم، تک وتنها، جدا از پنجاه تن افرادی که برای پیشواز شاه آمده بودند. بیتی از شاهنامه را آماده کرده بودم که خوشآمد رستم به اسفندیار است: خنک شهر ایران که تخت تو را / پرستند و بیدار بخت تو را. هنگامی که هلیکوپتر بر زمین نشست، شاه پیاده شد. گزارش نظامی را شنید. سپس به سوی من راه افتاد. سخنانم را آماده کرده بودم ولی فرصتی نیافتم که بیانشان کنم. او توقف نکرد. آهنگش را آهسته نکرد. حتا نگاهی هم نینداخت.

September 13, 2023

(27/54) “One morning I was called into the Speaker’s office...

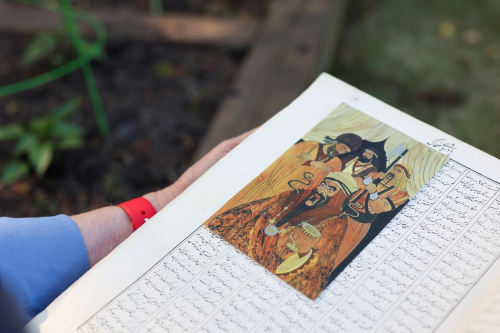

(27/54) “One morning I was called into the Speaker’s office along with another colleague. We were told that he’d received a call from the king’s office, and the king needed our two votes on an upcoming issue. My colleague was silent. But I replied: ‘I cannot do it. If I was a soldier of the king, I would crawl across the floor at his command. But I am a representative of the people. And I answer only to them.’ When I looked over, my colleague had tears in his eyes. Nobody disobeyed a direct request from the king. But Iran was a constitutional monarchy. We had a constitution. That was supposed to mean something. It had to mean something, or we were left with nothing but a king. I knew I wasn’t helping my career. The parliament was a corrupted system, and the only way to advance was to support the king. But I wasn’t there to be part of the system. I was there to scream 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. Freedom. One afternoon the Speaker told me that the king would be making a trip to Nahavand, and I should be there to greet him at the airport. I searched Shahnameh for the perfect quote to welcome him. I chose from one of my favorite stories: the story of Rostam and Esfandiyar. In this story Rostam is a much older man. He’s served many kings. But the current king has turned oppressive, and Rostam refuses to obey his commands. The king sends his son Esfandiyar to arrest Rostam. Esfandiyar promises Rostam that the king only wishes to set an example. He says: ‘Please, just let me bind your hands.’ He promises that he’ll immediately be released. He promises Rostam all the riches of the kingdom, if only he’ll allow his hands to be bound. Esfandiyar is protected by a divine blessing. He has never been beaten in battle. And Rostam knows that if they fight, he will almost certainly die. But still, he will not allow his hands to be bound. He’d never give up his 𝘢𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. Here Ferdowsi shows his genius. The dialogue is rich. The men dine together. They share wine. They flatter each other. Each man does everything to persuade the other to change his mind. But their fate was already written. They would battle to the death. Because one could not disobey his king. And the other could not disobey his code.”

بامدادی همراه یکی از همکاران به دفتر رئیس مجلس فراخوانده شدیم. گفت که از دفتر شاه پیامی رسیده که میخواهد ما در رأیگیری پیش رو رأی موافق بدهیم.گفتم: «اگر من سرباز شاه میبودم، سینهخیز از این سو به آن سو میرفتم و فرمانش را میپذیرفتم ولی من نمایندهی مردمم.» اشک در چشمان همکارم بود. رئیس برآشفته گفت: “یکبار بر سر بحرین دوستان شما مرا بدبخت کردند و امروز شما.” سرپیچی از درخواست شاه کمسابقه بود. قانون اساسی ایران سلطنت مشروطه بود و این باید گویای واقعیتی باشد. هنگامی که سیاستهای شاه به سود ایران باشد، نخستین کسی هستم که از آنها پشتیبانی کنم ولی کشور نمیتواند بر پایهی یک اندیشه اداره شود. اگر آن اندیشه خردمندانه هم باشد. هر چیز میباید با اندیشههای گوناگون بررسی شود. بسیاری شنیده شوند تا مردمان دریابند که شهریاران میهنند. پیام رئیس مجلس خبر از آمدن شاه به نهاوند میداد و میخواست اگر بتوانم آنجا باشم. خبر خوبی بود. نهاوند نیازمندیهایی داشت. میشد آنها را در میان گذاشت. شاهنامه را زیر و رو کردم تا بهترین پیام خوشآمدگویی را بیابم. پیامم را در یکی از داستانهای دلپسندم یافتم، داستان رستم و اسفندیار. در این داستان رستم مردیست سالخورده. شاهان بسیاری را یاری کرده است. ولی آنگاه که پادشاه زمانه ستمگر شود، از فرمانبرداری او سر میپیچد. گشتاسب پسرش اسفندیار را میفرستد تا دست رستم را ببندد و نزد او ببرد. اسفندیار خواهان جنگ نیست. اسفندیار به رستم چنین خوشآمد میگوید: که یزدان سپاس ای جهان پهلوان / که دیدم ترا شاد و روشن روان / سزاوار باشد ستودن ترا / یلان جهان خاک بودن ترا / خنک آنکه او را بود چون تو پشت / بیاساید از روزگار درشت. اسفندیار رویینتن است و هرگز تا آن روز شکست نخورده است. رستم میداند که در صورت نبرد، کشته خواهد شد ولی نمیپذیرد دستانش بسته شوند زیرا هرگز از آزادی خود نمیگذرد. در اینجا نبوغ فردوسی هویداست. گفتوگوی این دو بسیار پر بار است. به ستایش یکدیگر میپردازند. رستم اینچنین به ستایش اسفندیار میپردازد: خنک شاه کو چون تو دارد پسر / به بالا و فرت بنازد پدر / همه ساله بخت تو پیروز باد / شبان سیه بر تو نوروز باد / دو گردنفرازیم پیر و جوان / خردمند و بیدار، دو پهلوان. آنها به هر تلاشی دست می یازند تا رای دیگری را برگردانند ولی سرنوشت آنها نوشته شده است. وارد نبردی مرگبار خواهند شد زیرا یکی از پادشاهی خود نمی گذرد و دیگری از آرمانش

(26/54) “Mitra was the oldest in her class, but all the younger...

(26/54) “Mitra was the oldest in her class, but all the younger students loved her. She knew all the latest in culture: the movies, the magazines, the trends. Every night when I came home she’d always be up listening to tapes. The seventies were a golden age of music in Iran: Googoosh, Delkash, Marzieh, Aslani, Hayedeh, Shajarian. And Mitra had many of their songs memorized. She was a great student. During the second year of her program she was chosen to study under one of Iran’s top Shahnameh professors. It was the closest she ever came to understanding me. One day in class the professor told her that every society needs a few idealists, because they’re the ones who move society forward. Often I would help with her homework, and it helped me view Shahnameh from a more academic perspective. Ferdowsi uses the mythic kings as placeholders for periods in Iran’s history. When he writes that Jamshid ruled for seven hundred years, he means that it was a time of great freedom and culture in Iran. But when Jamshid loses touch with the people, a period of terror and oppression follows. The throne is taken over by the Serpent King Zahak. In Shahnameh Zahak is the embodiment of darkness. He cares only for his own power. Two giant snakes grow out of his shoulders. The devil promises Zahak that he will stay in power, as long as he feeds the snakes with the brains of young Iranians. It had to be the brains of the young. Because young people are the ones with energy. They’re the ones with courage. They’re the ones that can overthrow the regime. One day twenty students at Mitra’s school entered the cafeteria wearing masks, and began to forcibly separate men and women. They physically assaulted any women who were wearing make-up or Western clothing. On the way out they scattered pamphlets on the floor, warning that all women should adhere to Islamic guidelines, or there will be consequences. An atmosphere of fear began to spread across the campus. Mitra began wearing a hijab to school. She chose a beautiful white one, made of silk.”

میترا از همکلاسیهایش مسنتر بود، همکلاسیهای کمسنوسالتر او را دوست داشتند. دایرهی دوستانش گسترش یافت. میترا از تازهترین رویدادهای فرهنگی با خبر بود: فیلمها، روزنامهها و گرایشها. شبها که به خانه برمیگشتم او را در حال شنیدن نوارهای کاست میدیدم. دههی هفتاد دوران طلایی موسیقی بود: گوگوش، دلکش، مرضیه، اصلانی، هایده، شجریان و … میترا بیشتر ترانههای آنها را از بر داشت. در سال دوم دانشگاه، کلاسی را برگزید که استادش یکی از برجستهترین استادان شاهنامهشناسی دانشگاه تهران بود. سالی بود که میترا را بیش از همیشه به اندیشههایم نزدیک میدیدم. روزی استادش گفته بود که همهی جامعهها نیازمند آرمانخواهاناند زیرا آنها هستند که جامعه را پیش میرانند. اگر فرصتی دست میداد، در درس شاهنامه یاریاش میدادم. این کار برایم خوشایند بود. کمک کرد تا داستانهای شاهنامه را از دیدگاه دانشگاهی بکاوم. دریافتم که فردوسی پادشاهان افسانهای را بسان نمایندگان بازههای زمانی برگزیده است. هنگامی که مینویسد پادشاهی جمشید هفتسد سال به درازا کشید، منظور او دوران آزادیهای فراوان و گسترش پرشکوه ایران و فرهنگ ایرانیست. ولی پیوند جمشید با مردم گسسته میشود. فر او میکاهد و تخت پادشاهی به ضحاک میرسد. ضحاک نماد تاریکیست. خودکامهای ستمگر است. دو مار بزرگ بر شانههای او میرویند. اهریمن به ضحاک میگوید تا زمانی که مارها را با مغز جوانان سیر نگه دارد، آسوده خواهی زیست زیرا جوانان نیرومند، آرزومند و دلیرند! جوانان میتوانند حاکمان ستمگر را سرنگون کنند. یک روز بیست دانشجو وارد سالن غذاخوری دانشگاه شدند و به زور مردان و زنان را از هم جدا کردند. آنها به زنانی که آرایش کرده و لباس غربی پوشیده بودند، یورش بردند. هنگام بیرون رفتن از سالن غذاخوری، بیانیههایی بر زمین ریختند که به زنان هشدار میداد، میبایستی به احکام اسلامی پایبند یا در انتظار پیآمدهایی ناگوار باشند. ترس در پردیس دانشگاه گسترده شد. میترا حجاب بر سر کرد. او روسری ابریشمین سپیدرنگی را برگزید

(25/54) “There is a game that Mitra and I would often play. One...

(25/54) “There is a game that Mitra and I would often play. One of us would recite a verse from a poem. Then whatever letter that verse ended with, the other person would think of a verse that began with that letter. We’d go back and forth until someone got stuck. And Mitra could not be beaten. Her memory was a library of Persian poetry. When our children were older she applied to the literature program at the University of Tehran. It was a very selective program, but she received one of the highest possible scores on the admissions test. Some mornings I’d drop her off at school on my way to parliament. She’d have me drop her off down the street, because she didn’t want to be seen with a parliamentarian. The college campuses in Tehran had become a hotbed of political protest. With his White Revolution the king had provided free education to the children of Iran. Now those children were grown, and they wanted a say in the future of their country. Many wanted more freedom. They wanted truly free elections. They wanted an end to censorship, an end to political persecution, an end to SAVAK. Others thought the king had brought too many freedoms to Iran: the capitalism, the tight clothes, the violent movies. It was too much, too fast. They wanted a return to tradition. And Islam became a rallying point. But this was the Islam of our fathers. An Iranian Islam. The Islam of Rumi. The Islam of Hafez. During our next break from Parliament I visited a bookshop. The owner reached beneath his desk and pulled out a book by Khomeini, the cleric from Qom who had incited the riots in Tehran. Khomeini had been sent into exile by the king, but he still had a large following in the country. His speeches were smuggled into the country on cassettes and sold in the bazaar. In his book he called for an Islamic dictatorship. He talked about returning to ‘the source’ of Islam. Sharia Law. It was an Islam from fourteen hundred years ago. An Islam of cutting off hands, oppression of women, and death for non-believers. He said that ‘Islam provides a law for every aspect of human life.’ But he did not say how the law would be enforced. That he said, would be figured out later.”

گاهی میترا و من با یکدیگر مشاعره میکردیم. با بیتی آغاز میشد. آخرین حرف بیت میبایستی نخستین حرف بیت بعدی باشد، تا آنجا ادامه مییافت که یکی نتواند بیتی به یاد آورد. هیچگاه نتوانستم میترا را شکست دهم. حافظهی او کتابخانهی کوچکی از شعر فارسی بود. هنگامی که فرزندانمان بزرگتر شدند، میترا تصمیم گرفت در رشتهی ادبیات دانشگاه تهران نامنویسی کند. رشتهای گزینشی بود، آزمون را به خوبی گذراند. روزهایی در مسیر کارم او را به دانشگاه میرساندم. از من میخواست کمی دورتر از دانشگاه او را پیاده کنم. نمیخواست با همکلاسیهای جوانش که با اتوبوس میآمدند فرقی داشته باشد. دربارهی من به آنها چیزی نمیگفت. دانشگاههای تهران کانون ناآرامیها و اعتراضهای سیاسی شده بودند. آموزش رایگان برای همه فراهم بود. اکنون کودکان بزرگشده میخواستند نقشی در آیندهی سرزمینشان داشته باشند. امیدبخش بود. بسیاری خواهان آزادی بیشتر و سانسور کمتر ،نبود آزار و اذیت سیاسی و ساواک بودند. گروهی دیگر بر این باور بودند که شاه بیش از اندازه به مردم آزادی داده است. میگفتند ایران غربزده شده است: مادیگرایی، لباسهای تنگ و فیلمهای خشن در زمانی بسیار کوتاه. میخواستند به سنتهای مذهبی برگردند. اسلام انگیزهای برای رسیدن به این خواستها شد. حجاب به نمادی از اعتراضهای سیاسی تبدیل شد. ولی اسلام پدران ما اسلام ایرانی بود. اسلام مولانا و حافظ. تابستان بود، به کتابفروشی بازار تجریش رفتم. فروشنده دستش را زیر میز برد و کتابی از خمینی بیرون آورد، تازه به دستش رسیده بود. او را از سال ۱۹۶۳ از ایران بیرون کرده بودند ولی هنوز طرفدارانی در کشور داشت. سخنرانیهایش بر روی نوار کاست به صورت مخفیانه و قاچاق به کشور وارد میشدند و در بازار به فروش میرسیدند. او در کتابش خواهان یک دیکتاتوری اسلامی بود. بازگشت به اسلام نخستین، اسلام ۱۴۰۰ سال پیش. اسلام بریدن دستها، مهار کردن زنان، چندهمسری، سرکوب دگراندیشان، از میان بردن آزادیهای اجتماعی و فرهنگی و مرگ برای ناباوران. او میگفت که اسلام برای هر بخشی از زندگی انسانها قانونی دارد ولی هرگز نگفت چگونه آن قانونها اجرا خواهند شد. آن را به آیندهی تاریکی سپرد که هنوز در آن گرفتاریم

(24/54) “One afternoon the empress and prince attended a session...

(24/54) “One afternoon the empress and prince attended a session of parliament. It was an important day. Everyone was hoping to make a strong impression, and I’d prepared a speech especially for the occasion. I was the last speaker on the schedule. The Speaker of Parliament saw me approaching the podium and tried to wave me off. When I kept coming, he hurriedly adjourned the session. I think some of my colleagues viewed me as an annoyance. I’d developed a reputation for speaking my mind. And whenever I could speak, I spoke. I gave a speech on every budget, every proposal, every vote. The topic was always different. But the theme was always the same: 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. Justice. The word that appears most in Shahnameh. Everyone gets what they deserve. One day I gave a speech saying I’d been informed that Iran’s highest-ranking admiral had used a battleship to import Italian furniture. I asked how we could allow such corruption, from a man with a breast full of public service medals. The crowd was silent. It was unheard of to criticize the military, because it was in the hands of the king. But I wanted to show that I was not afraid to speak. So that other Iranians would feel free to share their thoughts. My words were never heard in the media. If there was ever a mention in the newspaper, it would only say: the representative from Nahavand gave a speech. But still, I spoke. I always had hope that I’d find a way to be heard. There is an Iranian proverb about ‘words that fly.’ It says that if words are false, if they are self-serving, if they come from ambition: they will never fly. Even if they’re shouted from loudspeakers. Even if everyone says them at the exact same time: they will soon be forgotten. For they have no soul. They have no 𝘫𝘢𝘢𝘯. But if a person can find the right words. If the words have 𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘨, if the words have 𝘬𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘢𝘥, if the words have 𝘳𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪- they will grow wings. And they will fly. Even if they’re censored; they will fly. Even if they are silenced; they will fly. Even if they are buried deep in the ground; they will still fly. And they will reach the doorstep of every household.”

بعد از ظهر شهبانو و شاهزاده به نشست مجلس آمده بودند. روز مهمی بود. بودجهی سال آینده در مجلس بررسی میشد. نمایندگان رسانهها برای گزارش این رخداد دعوت شده بودند. من شب پیش در رویارویی با نخست وزیر در زمینهی قانون «از کجا آوردهای» بگو مگو داشتم. در آنجا سخنان تندی میان ما رد و بدل شده بود. رئیس مجلس ترسیده بود که من در هنگام بررسی لایحهی بودجه آنها را به میان آورم. هنگامی که نمایندهای دیگر را در حال بازگو کردن سخنانم در مجلس دیدم، شگفتزده شدم. سخنران بعدی من بودم. برخاستم تا به سوی تریبون بروم که رئیس مجلس پیشنهاد کفایت مذاکرات داد و جلسه پایان یافت. مرا به رُکگویی میشناختند. بیشتر نمایندگان به رویدادهای محلی میپرداختند. من همواره دربارهی اولویتهای ملی سخن میگفتم. در رابطه با هر بودجهای، هر پیشنهادی و هر رأیگیری سخنرانی میکردم. زمینهها متفاوت ولی بُنمایه همیشه یکسان بود: دادگری. واژهای که بسیار در شاهنامه آمده است. همه، آنچه را که شایستهی آنند دریافت میکنند. باری در یک سخنرانی گفتم باخبر شدهام که دریاسالار، فرمانده نیروی دریایی از ناو جنگی برای وارد کردن اسباب و اثاثیه خانهاش از ایتالیا استفاده کرده است. پرسیدم چگونه میتوانیم چنین فسادی را برتابیم، و آن هم از مردی با سینهای پر از نشانهای افتخار. همه ساکت بودند. انتقاد از نیروهای نظامی امری کاملاً ناشناخته بود، زیرا آنها برگزیدهی شاه بودند. من میخواستم نشان دهم که از بیان راستیها بیمی نباید داشت. شاید دیگران نیز چنین کنند. آن فرمانده برکنار شد. کشور را نیکخواهی مردمانش پیش میبرد و نیازمند مسئولیتپذیری دلیرانه است. سخنان من هرگز در رسانهها بازتاب داده نمیشد. اگر هم در روزنامه اشارهای به آن میشد، تنها گفته میشد: نمایندهی نهاوند سخنرانی کرد. ولی من کار خود را میکردم. همیشه امیدوار بودم که راهی برای شنیده شدن پیدا کنم. پندواژهای دربارهی «سخنانی که پرواز میکنند» وجود دارد که میگوید اگر سخنان دروغ باشند، اگر خودخواهانه باشند، اگر آزمندانه باشند، هرگز پرواز نخواهند کرد، حتا اگر از بلندگوها فریاد زده شوند. حتا اگر همه در یک آن آنها را بیان کنند، بزودی فراموش میشوند زیرا جان ندارند. ولی اگر کسی واژههای مناسبی پیدا کند، سخنانی آهنگین، خردمندانه و راستین، بال خواهند گشود و پرواز خواهند کرد. حتا اگر از شنیده شدنشان جلوگیری شود، پرواز میکنند. حتا اگر گویندگانشان را خاموش کنند، پرواز میکنند. حتا اگر در ژرفای زمین فرو برند، همچنان پرواز میکنند و به در هر خانهای میرسند

(23/54) “Each night when I came home from parliament I’d find...

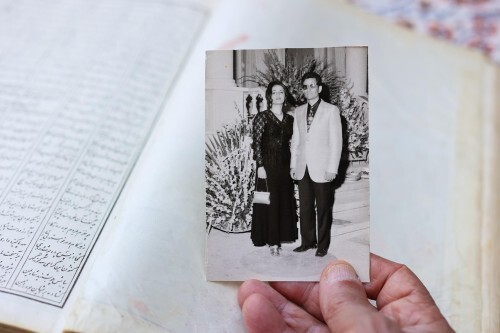

(23/54) “Each night when I came home from parliament I’d find Mitra ready to go out. And no matter how tired I felt, off we would go. She always looked perfect. She stayed current with all the latest trends. Every few months she’d have her hair cut in the style of a different American actress. I loved having her by my side in social situations. I was horrible at parties. I could never think of the right thing to say. If I tried to make a joke, people would tickle themselves to laugh. But not Mitra. She was spontaneous, she was funny. Words came from her like light from a lamp. And she could speak to anyone. There were never any formalities. No warm-up. She’d talk to every person as if she’d known them her entire life. We’d go to gatherings with ten or fifteen of our friends; often Dr. Ameli would be there. As soon as Mitra walked in the room the silence would end. At some point in the evening the conversation would always turn to politics. And the moment I began to debate an issue, Mitra would take the other side. She would team up with anyone against me. The person never mattered. The topic never mattered. She never wanted to get me started, so she’d always shut me down. It’s how we’ve been our entire lives. I’ve been the gas, she’s been the brakes. I thought about her every time I wrote a speech. She’s always been my antithesis. The hardest for me to convince. It could sometimes seem like her main purpose in life was to oppose me. To the outside world our love made no sense. We seemed so far apart. But there are many types of closeness. And some the world will never see. We still read poetry together. Mitra still trusted me to find the melody. There was one poem called ‘Sin,’ by Forough Farrokhzad. It scandalized religious society; everyone was talking about it. But it was one of Mitra’s favorites, so I’d memorized the entire thing: 𝘐 𝘴𝘪𝘯𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢 𝘴𝘪𝘯 𝘧𝘶𝘭𝘭 𝘰𝘧 𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘶𝘳𝘦 / 𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘯 𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘸𝘢𝘳𝘮 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘢𝘨𝘦𝘳 / 𝘐 𝘴𝘪𝘯𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘸𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘳𝘮𝘴 / 𝘩𝘰𝘵, 𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘥, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘷𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘪𝘯𝘨 / 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘢𝘳𝘬 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘴𝘦𝘤𝘭𝘶𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 / 𝘐 𝘬𝘯𝘦𝘸 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘴𝘦𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘵𝘴 / 𝘮𝘺 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘮𝘺 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘵 / 𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘩𝘶𝘯𝘨𝘳𝘺 𝘦𝘺𝘦𝘴.”

هر شب که از مجلس به خانه برمیگشتم، میترا را میدیدم که آمادهی بیرون رفتن بود، با همهی خستگیها باید میرفتم. بودنش در کنار من همیشه دلپذیر بود. خوشلباس بود. بریدههای مجله را نزد خیاطش میبرد و مو به مو آنچه را میخواست به او میگفت. موهایش همواره آراسته بود. هر چند ماه یکبار، موهایش را به سبک بازیگری آمریکایی به مدلهای گوناگون کوتاه میکرد. در مهمانیها آرامش نداشتم. هرگز نمیتوانستم سخنان مناسبی برای گفتوگوی معمولی بیابم. هر بار تلاش میکردم شوخی کنم، مردم به زور میخندیدند. ولی میترا نه. واژگان به راحتی از دهانش بیرون میآمدند مانند نور از چراغ. او خودجوش بود، شوخ بود. میتوانست با هر کس سخن بگوید. هیچ رودربایستی نداشت. نیازی به آمادگی نداشت. با هر کس چنان سخن میگفت که گویی همهی عمر او را میشناخته است. با ده، پانزده تن از دوستانمان دوره داشتیم؛ در پارهای از مهمانیها دکتر عاملی هم میآمد. همین که میترا به اتاق وارد میشد، خاموشی پایان مییافت. زمانی میرسید که گفتوگوها به سیاست میگرایید. درست زمانی که من وارد بحثی میشدم، میترا بیدرنگ جانب شخص مقابل را میگرفت. او در برابر من با هر کس متحد میشد. مهم نبود چه کسیست. مهم نبود زمینهی گفتوگو چیست. او تنها میخواست مرا ساکت کند. من چون پِدال گاز بودم و او چون ترمز. هر گاه متن یک سخنرانی را مینوشتم، به میترا فکر میکردم. او همواره نقطهی مقابل من بوده است. سرسختترین شخصی که میبایستی متقاعد میکردم او بود. گاه به نظر میرسید که هدف بزرگ او در زندگی مخالفت با من بوده است. از دیدگاه دنیای بیرونی، عشق ما منطقی نمینمود. بسیار دور از هم به نظر میرسیدیم. ولی گونههای بسیار از نزدیکی وجود دارند و برخی را دنیا هرگز نتواند دید. ما همچنان با هم شعر میخوانیم. میترا هنوز باور دارد که من آهنگ شعر را به درستی درمییابم. شعریست از سرودههای فروغ فرخزاد به نام «گناه». این شعر جامعهی مذهبی را به چالش میکشید؛ همه دربارهی آن سخن میگفتند. میترا این شعر را چندان دوست داشت که آنرا از بر کرده بود: گنه کردم گناهی پر ز لذت / در آغوشی که گرم و آتشین بود / گنه کردم میان بازوانی / که داغ و کینهجوی و آهنین بود / در آن خلوتگه تاریک و خاموش / نگه کردم به چشم پر ز رازش / دلم در سینه بیتابانه لرزید / زخواهشهای چشم پر نیازش

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers