Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 4

September 15, 2023

(46/54) “There was nothing I could do. It was like watching a...

(46/54) “There was nothing I could do. It was like watching a child fall from the roof of a building. I could only look on in agony. When I arrived in Germany there were two million unemployed. It was years before I could find a job. Resistance takes resources: you must travel, you must speak, you must organize. I just didn’t have the means. I moved into a small apartment with my daughter Ahang. I’d spend all day listening to the radio for news reports about Iran. I kept hoping that it would be over in an instant. That a dam would break, and everyone would say at the same time: ‘This is not working for us.’ But that moment never came. The grief would not leave me. I wrote poems about Iran. I taught myself to paint, and I painted paintings of Iran. All day I’d pace back and forth in the living room. I’d talk to myself like a madman: ‘How did we fall into this deep pit? How can we get out again?’ I can’t explain it. It’s an irrational love, an illogical love. I don’t know where it comes from. It begins before my memory. There’s so much to love about Iran. It’s so many things: it’s a land, it’s a people, it’s a culture, it’s a story, it’s a myth. But it’s not something you can hold. Through it all, my greatest grief was for Mitra. Less than a month after I left the country, another war started. Iraq invaded Iran, and the borders were closed for four years. Four years without seeing her. She’d write me letters every day. She’d tell me every little thing. One year she sent me a calendar, and she’d written me a love poem from a different poet on every page. Telephones were tough to come by, but she always found a way to call. Mostly we would share news. But we still found time to read each other poetry. It is said that at any given time there are one hundred thousand poets in Iran, and I am not one of them. But in Germany I finally wrote her some poetry of my own: 𝘐 𝘸𝘪𝘴𝘩 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘺 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯’𝘵 𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘦 / 𝘐 𝘸𝘪𝘴𝘩 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 /𝘠𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘨𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘢𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘦 /𝘞𝘪𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶, 𝘐’𝘮 𝘢 𝘣𝘳𝘰𝘬𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘩 / 𝘢 𝘣𝘰𝘥𝘺 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘢 𝘴𝘰𝘶𝘭/ 𝘢 𝘥𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘧𝘭𝘢𝘮𝘦/ 𝘞𝘪𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶, 𝘐’𝘮 𝘙𝘰𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘮 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘥.”

کاری از دستم برنمیآمد. تماشای افتادن کودکی از بام بود، آنهم در اندوهی سهمگین. پایداری به پول نیاز دارد و منابع مالی. باید سفر کرد، باید سخنرانی کرد، باید سازماندهی کرد. گذران یک زندگی ساده هم برایم دشوار بود. زمانی که به آلمان رسیدم، دو میلیون نفر بیکار بودند. با آهنگ همخانه شدم. او دانشجو بود. آپارتمانِ اجارهای کوچکی بود. سالی چند به درازا کشید تا توانستم کاری بیابم. هر آنچه در توانم بود میکردم. مقاله مینوشتم. میکوشیدم تا خود را از غم و اندوه برهانم. چامهای چند دربارهی ایران سرودم. نقاشی را خودآموزی کردم و از ایران میکشیدم. اما بیشتر وقتم را به قدم زدن در اتاق نشیمن میگذراندم. از گوشهای به گوشهای قدم میزدم، و ساعتها ادامه مییافت. یادمانها را میکاویدم تا دریابم: “چگونه در این گودال ژرف فُرو افتادیم؟ چگونه میشود دوباره بیرون آییم؟” این درد مرا آسوده نمیگذاشت. انگیزهی دلبستگیها را شناختن آسان نیست. آبشخورش کجاست؟ عشق است و عشق پدیدهای ناشناخته است، منطقینیست، غریزیست. پیش از یادها آغاز میشود. ایران پدیدهی سادهای نیست، پیچیده و تو در تو ست، خاک است، مردم است، فرهنگ است، داستان است، اسطوره است. عشقی بیپایان است. مادر است، پدر است، خواهران و برادران است، دوستان است. همه چیز است. بی او چیزی نیستم! در کنار اینها و فراتر از آنها، میترا بود. کمتر از یک ماه از رفتنام نگذشته بود که صدام حسین به خاک ایران تجاوز کرد. مرزها بسته شدند. هر روز نامه مینوشت. از تمام جزئیات با من سخن میگفت. یک سال، تقویمی برایم فرستاد که بر هر برگ آن سالشمار شعری عاشقانه از هر شاعری که میشناخت با خط خوش نوشته بود. در آن زمان تماسهای تلفنی بسیار دشوار بود. او همیشه راهی پیدا میکرد و گفتوگو میکردیم. بیشتر وقتها خبرها را به هم میدادیم. اما گاهی هم شعری برای هم میخواندیم. گویند سدهزار شاعر همزمان در ایران هستند. من یکی از آنها نیستم ولی در آلمان بِیتی چند برایش نوشتم: بی تو دامادِ خُفته در کفَنَم / بی تو افسُردهجان و خَستهتَنم / بی تو آسودگی کُجا با من / همه با درد و رنج همسُخنم / بی تو از هم گُسسته در زنجیر / چشمِ تاریک و خسته را مانَم / بی تو پایِ شکسته اَندر گِل / رُستَمِ دَستبَسته را مانَم

(45/54) A jar of soil. That’s all I have left of my home. It’s...

(45/54) A jar of soil. That’s all I have left of my home. It’s good soil. A guidebook once called Nahavand ‘a piece of heaven, fallen to earth.’ But there’s blood in the soil too. There have been more wars on Iran’s soil than any other country. We’ve had more battles, more bloodshed, more defeats than any other people. And this has been one of the worst of them. The people who stayed in Iran tried their best. But one by one they fell: anyone who stepped out, anyone who spoke up, anyone who said: ‘This is not working for us.’ They were silenced. It was a savage violence. A violence from fourteen hundred years ago. From the moment of those very first executions on the roof of the school, there has been no coherence. No 𝘥𝘢𝘢𝘥. The smallest act could lead to death: a blog post, a sign at a protest, a few strands of hair showing beneath a headscarf. The regime needs fear to stay in control. And for fear to spread, the violence must be random. So that everyone thinks: ‘I could be next. It could happen to me.’ They’ve turned the country into a dark forest. When there is light, when there is law, when there is 𝘥𝘢𝘢𝘥, you know where danger comes from. You can keep away from it. But in the dark danger can come from anywhere, at any time. Parvaneh stayed. The young woman from 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰. The one with the strongest voice. She tried to work for change within the country. In an interview she told a reporter: ‘Iranians abroad can provide spiritual support, but the front must emerge from within Iran.’ She kept writing. She kept speaking out. She kept fighting for political freedom. Only now she was fighting for one-tenth the freedoms that she had before. One night the intelligence services broke into her home. They stabbed her to death, alongside her husband. Dariush was a tall man, much bigger than Parvaneh. But they stabbed her twice as many times. Either they hated her twice as much, or she fought them twice as hard.”

شیشهای خاک است، از خانهام ایران. همهی آنچه از زادگاهم برایم مانده است. خاک خوبیست. خاک نهاوند. زمانی کتاب ایرانگردی آن را “پارهای از بهشت بر زمین افتاده" نامیده بود. خون بسیارانی با آن خاک درآمیخته است. خاک ایران بیش از هر سرزمین دیگری درگیر جنگ و ستیز بوده است. ما بیش از هر ملتی نبردها، پیروزیها و شکستها داشتهایم. اما این یکی از بدترینها بود. مردمی که در ایران ماندند، تلاش خود را کردند. ولی آنان را یکی پس از دیگری از میان برداشتند: هر کس پا پیش نهاد، پرسشی کرد، هر کس گفت: “این برای ما کارآمد نیست.” همه را خاموش کردند. خشونت دهشتناکی بود. خشونتی برآمده از هزار و چهارسد سال پیش. از آن دم که نخستین اعدامها بر پشت بام آن مدرسه آغاز شد، بیداد پهلوان میدان بود. کمترین جنبش مرگآور بود: یک پُست وبلاگی، یک پوستر اعتراض، چند تار مو که از زیر روسری نمایان باشد. رژیم میداند که خشونت باید ناگهانی و بیدلیل باشد تا ترس همهگیر شود. تا همه بپندارند: “شاید نفر بعدی باشم. این رویداد برای من هم رخ خواهد داد.” کشور را جنگلی تاریک کردهاند. هنگامی که روشنایی باشد، هنگامی که قانون باشد، هنگامی که داد باشد، خطر را میتوان شناخت. تاریکی اما از هر سو و هر آن تو را غافلگیر خواهد کرد. پروانه ماند. جوانترین عضو نیرو. آنکه رساترین صدا را داشت. ضد شاه بود. از اینرو فکر میکرد در امان است، تلاش کرد از درون کشور تغییر ایجاد کند. به روزنامهنگاری گفته بود: “ایرانیان خارج از کشور میتوانند پشتیبان معنوی باشند، اما کارزار میبایستی در درون پا بگیرد.” به نوشتن و سخن گفتن ادامه داد. به نبرد برای آزادی، برای یک دهم آزادیهایی که پیش از این داشت! یک شب دژخیمان رژیم اهریمنی به خانهشان ریختند. او و همسرش، داریوش فروهر را با زخم کارد کشتند. داریوش مردی بلندبالا و بسیار نیرومندتر از پروانه بود. پروانه را دو برابر او زخم زده بودند. یا کینهشان به او دو برابر بود، یا او دو برابر پایداری کرده بود

(44/54) “On my final morning in Iran I woke with the sun....

(44/54) “On my final morning in Iran I woke with the sun. I knelt to the ground and prayed. It was a six mile walk to the border. The road climbed through the mountains, the same mountains that ran through Nahavand. But in Nahavand the trees were green. Here there was no life. Ferdowsi once wrote: ‘You cannot escape what is written.’ I’ve always hated that quote. There’s always a choice to be made. Just do the next right thing. That’s what I’ve always believed. Do the next right thing, say the next true thing, and a path will open up. A way will appear. I thought that we could get there. I thought that we, as a people, were going to get there. Every day we would take a step closer: more jobs, more hospitals, more schools. If only we kept choosing the next right thing, we could get there. We could build a new Iran around us. In the end light would win, as Ferdowsi writes: ‘The universe bends toward goodness.’ But you must never underestimate the forces of darkness. They can be victorious for a long time. Years. Decades. Lifetimes. Ferdowsi worked for thirty-three years. Seven verses a day. In the name of the God of Soul and Wisdom. But when he finished no one cared. Iran had been invaded once again, this time by the Turks. No one took the time to read his words. He died a broken man. Nobody heard the story of his life. Nobody heard the story of his death. He wasn’t even given a proper burial. The local cleric wouldn’t allow him to be buried in an Islamic cemetery, so they buried him in his garden. But he died with hope. Because he knew. He knew that no matter how deep they are buried, some words have wings. At the end of Shahnameh, Ferdowsi wrote: “I shall not die. These seeds I’ve sown will save my name and memory from the grave.”

واپسین سپیدهدمم در ایران بود. با خورشید برخاستم و نماز خواندم. تا مرز دو فرسنگ راه بود و راه مرزی از کوهستان زاگرُس میگذشت. همان رشتهکوهی که از نهاوند هم میگذرد. ولی در نهاوند درختها سبز بودند. اینجا نشانی از زندگی ندیدم. مرز بسته و گذرگاه تهی بود. حس میکردم، مرگ پا به پای من می آید. فردوسی گفته بود: بکوشیم و از کوشش ما چه سود / کز آغاز بود آن چه بایست بود. همواره از این گفته بیزار بودهام. همیشه انتخاب و گزینشی هست. هراندازه تاریک مینماید، کار نیکِ پیشِ رو را انجام دهیم بس است. این باور همیشگی من بوده است. اگر تنها نیککردار باشیم و راستیها را بازگوییم، راهی باز و گذرگاهی نمایان خواهد شد. فکر میکردم که میتوانیم به آنجا برسیم. بر این باور بودم که ملت ما به آنجا خواهد رسید. هر روز یک گام و نزدیکتر خواهیم شد: پیشههای بیشتر، درمانگاههای بیشتر، آموزشگاههای بیشتر. اگرهمواره گزینههای نیکِ پیشِ رو را بر میگزیدیم به آنجا میرسیدیم، میتوانستیم ایرانی نو پیرامون خود بسازیم. هنگامی که چشماندازی بسیار تاریک هم روبهرویمان باشد، هنوز گزینهای هست تا سرنوشت را خود بنویسیم. همیشه گزینهای هست. نیکی یا بدی. روشنایی یا تاریکی. فرهنگ ما نویدبخش پیروزی روشنایی بر تاریکیست چنانکه فردوسی میسراید: که گیتی نگردد، مگر بر بهی / به ما بازگردد کلاه مهی. ولی هشیار باشیم، نیروی تاریکی را اندک نینگاریم! تاریکی میتواند زمانی دراز بپاید. سالها، دههها و بیشتر. فردوسی، دلشکسته جهان را بدرود گفت. یگانه پسرش مُرده بود. ایران در نبردی دیگر شکست خورده بود. ترکها اکنون کشور را زیر فرمان داشتند. سیوسه سال رنج او را در برآوردن آن کاخ بلند درنیافتند. گفتار نغزش ناخوانده ماند. مرد دینکار از خاکسپاری او در گورستان مسلمانان جلوگیری کرد. ناگزیر او را در باغ خانهاش به خاک سپردند. کسی داستان زندگی او را نشنید. کسی از مرگاش آگاه نشد. بزرگمرد روزگاران این خُرسندی را داشت که سخنانش در گور نمیشوند، بال گشوده و پرواز میکنند. هرجا و هر اندازه واژگانش را در ژرفای خاک فرو برند، بال خواهند گشود و پرواز خواهند کرد. جاودان مردا، تو میدانستی و آنرا به زیبایی سرودی: نمیرم از این پس که من زندهام / که تُخم سخن را پراکندهام

(43/54) “Thirty years earlier we’d sworn an oath, to give our...

(43/54) “Thirty years earlier we’d sworn an oath, to give our lives for Iran. I considered it. There was one parliamentarian who fled to the mountains and died fighting. Even with one eye, I was still a good shot. I could have made a stand. But if I gave my life, it would have to be in exchange for something. Thousands of people were dying at the time, and nothing was changing. The clerics only grew more powerful. The same slogans were being chanted in the streets. Our freedoms continued to be taken away. And then there was Mitra and the children. I couldn’t leave them behind. But with each week came more bad news: another colleague killed, another one arrested. My friends started encouraging me to leave the country, but I wouldn’t consider it. I had promised myself when I came home from Germany that I’d never leave Iran again. But even if I had wanted to, it wasn’t possible. I didn’t have a passport. I was on a list of people who were not allowed to leave the country. One afternoon we received a visit from a former colleague. He sat Mitra and I down in the living room, and he told us that he’d discovered a way to leave Iran through the Turkish border. There was a powerful family there that was known to oppose the regime. He said that the checkpoints weren’t stopping cars with families. So if Mitra rode to the border with me, I’d be able to walk the rest of the way on foot. He turned to Mitra, and said: ‘This is his final chance. If he is killed, never say that his friends abandoned him. We’ve done everything we can to convince him, so now it’s up to you.’ When he was finished, Mitra turned to me and said: ‘You must go.’ And Mitra’s word is law. We set out early in the morning. It was an eight-hour drive to the Turkish border. The entire ride was spent in silence. She kept her emotions hidden. I was a tsunami of tears. We kissed goodbye in Salmas. There was a statue of Ferdowsi in the main square.”

سی سال پیش سوگندی یاد کرده بودیم که جانمان را برای ایران ببازیم. به آن اندیشیدم. نمایندهی مجلسی بود که به کوهستان رفته و در جنگ و گریز جان باخته بود. با داشتن یک چشم، هنوز تیرانداز خوبی بودم. میتوانستم در درگیری ایستادگی کنم. ولی باید چیزی در برابر جان باختن بدست آورد. میدیدم هزاران تن به خاک افتادهاند. تنها بر قدرت روحانیون روز به روز افزوده میشد. همان شعارهای یکسان در خیابانها سرداده میشدند. آزادیهایمان را یکی پس از دیگری میگرفتند. با میترا و فرزندانم چه میکردم. او را نمیتوانستم بی پشت و پناه بگذارم. برخی دوستان مرا به ترک کشور میخواندند. جان بیبها بود. دوستانم یکی پس از دیگری دستگیر میشدند. یکبار هم به گزینهی رفتن نیندیشیده بودم. نه، حتا یکبار. گذرنامه هم نداشتم. نامم هم در لیست ممنوعالخروجها قرار گرفته بود. یک روز پس از نیمروز، دوست بس ارجمند سالهایم به خانهمان آمد. به گفتوگو نشستیم. گفت که مسیری برای ترک ایران از راه مرز ترکیه یافته است. خانوادهای پرنفوذ در آن ناحیه زندگی میکرد که مخالف رژیم بود. پلیس راه خودروهایی را که با خانواده سفر میکردند نگه نمیداشت. اگر میترا با من تا شهر مرزی میآمد، میتوانستم بازماندهی راه را پیاده بپیمایم. او به میترا گفت که این واپسین بخت است. گفت: “ما تمام تلاشمان را برای راهی کردنش انجام دادهایم. اکنون دیگر به شما بستگی دارد. اگر ماند و کشته شد، هرگز نگویید که دوستانش او را تنها گذاشتند.” میترا در خاموشی گوش فرا داد. هنگامی که سخن دوستم به پایان رسید، میترا رو به من کرد و گفت که باید بروی و سخنش قانون بود. سپیدهدم راه افتادیم. سراسر راه را در خاموشی گذراندیم. او احساساتش را پنهان میکرد. من توفان اشک بودم. در شهر سلماس با بوسهای یکدیگر را بدرود گفتیم. در میدان اصلی شهر تندیسی از فردوسی برپا بود

(42/54) “At dawn we woke to the sound of shots. First the...

(42/54) “At dawn we woke to the sound of shots. First the machine gun fire, then the single shots. That morning I counted more than ever before: twenty-one. When the newspaper arrived that morning, I ran my finger down the list until I found his name. It has always been my belief, that if one of us could have survived, it should have been him. He could have united people. His entire life, all his thoughts, all his words, led back to one thing: our common destiny. When you only fight for one lane, one party, one policy, all you see is conflict. Unity is so elusive. There is only one thing we all share: Iran. And nobody knew Iran more, nobody loved Iran more, than Dr. Ameli. We’d later learn his last words were: ‘Do not think of me, think of Iran.’ He was so brilliant. He could have earned all the money in the world. But that’s not where he stored his treasures. He chose to have less, so he could do more. And that is the rarest kind of person. There should be a statue of him in the center of Tehran. But nobody heard the story of his life. Nobody heard the story of his death. It was a seed that didn’t fall into soil. It was too dangerous to even hold a memorial service. We couldn’t grieve. We couldn’t gather together to share our memories. Our only way to honor him was to keep working, to keep resisting in whatever small way we could. We found an empty conference hall, a place so isolated that no one could hear our voices. And we’d hold meetings late at night. We’d bring in singers with beautiful voices, and they’d sing songs. Songs about loving Iran. And as people were leaving we’d hand out cassettes with the speeches of Dr. Ameli. At the very least we could spread his words. On the cover of the cassette we put a picture of his face, next to The Lion and The Sun. They’re two of the oldest symbols of Iran. The sun, the source of all light. And the lion. The lion is the most powerful animal in Iran. It’s loyal. It would do anything for its tribe. And it doesn’t run from anything. The lion is not the largest animal, but its power doesn’t come from its size. It comes from its heart. Its courage. Its soul. Its 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰.”

پنج بامداد با شلیک مسلسل از خواب پریدم. تکتیرها را شمردم. از روزهای پیش بیشتر بود. ۲۱ تیر. همینکه روزنامه رسید، با سرانگشتم لیست نامها را دنبال کردم تا به نام او رسیدم. همیشه بر این باور بودم که اگر از ما دو تن یکی جان به در برد، باید او باشد. او میتوانست مایهی همبستگی مردم باشد. پراکندگان را گرد هم آورد و گُسَستگان را به هم بپیوندد. در درازای زندگیاش همهی اندیشههایش، واژگانش به یک سرچشمه باز میگشتند و آن سرنوشت مشترک ملی بود. سخنانش پرواز می کردند. اتحاد چنان گریزان است که وقتی برای یک خط یا یک حزب یا یک سیاست مبارزه کنی، آنچه میبینی تنها کشمکش است. تنها یک چیز است که ما در آن مشترک هستیم و آن ایران است. و ایران است که ما برایش مبارزه میکنیم. بر آنم کسی بیش از او دربارهی ایران نمیدانست و ایران را دوست نداشت. چندی بعد شنیدیم که واپسین سخنش چنین بوده است: “به من نیندیشید، به ایران بیندیشید.” دکتر عاملی اندیشمندی یگانه بود. میتوانست از پس هر کاری برآید. فرهمند بود. آزمندی از جانش دور بود، گنجینهی جانش آکنده از مهر ایران بود. آگاهانه برگزیده بود کمتر داشته باشد تا بیشتر کار کند، برای ایران. چنین کسانی کمیابند، بلکه نایاب. باید تندیسی از او در دل ایرانشهر ساخت. کس داستان زندگیاش را نشنید. کس داستان مرگاش را نشنید. گویی دانهای بود که در خاک نیفتاده است. مراسم یادبودی هم بر پا نشد. نتوانستیم به یاد او گرد همآییم و غمگُساری کنیم. درد مرا رها نمیکرد. تنها راه دوام آوردن، ادامهی کار بود. پایداری تا توان داریم. تالاری که هیچکس نتواند صدایمان را بشنود، پیدا کردیم. و شبها دیرهنگام گرد هم میآمدیم. میآمدند تا با نوای خوش برای ایران آواز و ترانه بخوانند، سرودهای ملی، مردمی و میهنی. سرودهای دلدادگی به ایران. نوارهای کاست سخنرانیهای دکتر عاملی را میان مردم پخش میکردیم. کمترین کاری که میتوانستیم انجام دهیم، پخش کردن اندیشههایش بود. بر روی جلد نوار کاست، چهرهی تابناکش کنار درفش شیر و خورشید نشان بود؛ دو نماد امیدبخش از روزگاران کهن: خورشید، سرچشمهی نور و روشنایی و شیر، دلیرترین جاندار ایرانزمین. شیرخانواده دوست، شیر گریزناپذیر، نمادی از جان و دل، دلیری و نیرو

(41/54) “Mitra couldn’t sleep without me. On the nights when I...

(41/54) “Mitra couldn’t sleep without me. On the nights when I came home late, I’d always find her awake listening to tapes. We still read poetry together. Even in the midst of the chaos, even on the darkest nights, even if only for twenty minutes. It was my greatest comfort. The time when I felt most at peace. One of the most famous love stories in all of Shahnameh is the tale of Bijan and Manijeh. It’s a special story. Because it’s the one time in Shahnameh when Ferdowsi reveals a glimpse of his own life. He writes in the chapter’s opening that he has fallen into a great depression. He describes a night so dark that no birds sing. He calls for his wife to join him, and she brings him a candle. She offers to tell him a story, and Ferdowsi agrees to weave it into verse. She tells him the story of Bijan and Manijeh. Bijan is a champion of Iran. Manijeh is the daughter of an enemy king. By chance they meet in the forest, and Manijeh mistakes Bijan for an angel. She falls in love at first sight. She smuggles him back to her palace, and they spend several nights in each other’s arms. Until their love is discovered by the king. He grows so angry that he cries tears of blood. He banishes Manijeh from the palace. And he sentences Bijan to a fate worse than death. Total darkness. Bijan is chained to the bottom of the deepest pit, and a stone is rolled over the entrance. But Manijeh will not allow him to die. She roams the countryside, begging for food. She digs a hole beneath the stone, just large enough to fit her hand. And she keeps Bijan alive. One handful at a time.”

میترا بی من خوابش نمیبرد. شبها که دیر به خانه برمیگشتم، میترا را چشم به راه، گوش به آهنگها و ترانهها میدیدم. هنوز برای یکدیگر شعر میخواندیم. در میان آشوب، در تاریکی شب. اگر هم کوتاه، دمی پایدار و دلپذیر در زندگیما بود. یکی از پرآوازهترین داستانهای عاشقانهی شاهنامه، داستان بیژن و منیژه است. فردوسی تنها یکبار در شاهنامه گوشهای از زندگیاش را مینمایاند. در آغاز داستان، فردوسی سخن از افسردگی خود میگوید: شبی چون شبه روی شُسته به قیر / نه بهرام پیدا، نه کیوان، نه تیر / نه آوای مرغ و نه هرای دد / زمانه زبان بسته از نیک و بد / بدان تنگی اندر، بجَستم ز جای / یکی مهربان بودم اندر سرای / مِی آورد و نار و تُرنج و بِهی / زُدوده یکی جام شاهنشهی / دلم بر همه کار پیروز کرد / شب تیره همچون گه روز کرد. در چنین شبی همسرش برایش داستانی میگوید تا آنرا با زبان شیوایش بسراید. مرا گفت برخیز و دل شاد دار / روان را ز درد و غم آزاد دار / نگر تا که دل را نداری تباه / ز اندیشه و داد فریاد خواه / جهان، چون گذاری، همی بگذرد / خردمند مردم چرا غم خورد؟ همسرش داستان بیژن و منیژه را برایش بازمیگوید. بیژن سردار جوان ایرانی از دودهی پهلوانان بزرگ ایران و منیژه دخت افراسیاب، تورانشاه: شود کوه آهن چو دریای آب / اگر بشنود نام افراسیاب. یکدیگر را در جنگل اَرمان میبینند. بیژن به فرمان کِیخسرو به کشتن گرازان آمده است .منیژه بیژن را پریزادهای به زیبایی سیاوش میپندارد، بیژن میگوید: سیاوش نیاَم، نَز پریزادگان / از ایرانم، از شهر آزادگان. منیژه به او دل میبازد و او را پنهانی به کاخ خود میبرد و شبی چند را با شور و شادی میگذرانند. افراسیاب آگاه میشود، بیژن را در چاه و منیژه را در کوی و برزن رها میکند. منیژه، شاهدخت زیبای بیپروا، روزها لب نانی میجوید تا خود و بیژن زنده بمانند. او سوراخی زیر سنگ کَنده بود، به اندازهی یک مُشت

(40/54) “Every morning we awoke to the sound of shots. The...

(40/54) “Every morning we awoke to the sound of shots. The executions would begin with a volley of machine gun fire. Then there’d be a round of single shots, to make sure the prisoners were dead. I’d lay in bed and count them. When the newspaper arrived later that morning, I’d search for his name among the killed. I was so angry with him. He’d been so careless. On the day he decided to leave the safehouse, he had even made a joke. He’d said: ‘If they arrest me, we’ll all go to court and have a good laugh.’ He knew that he’d done nothing wrong. His entire career, he had been the model of integrity. He thought that his innocence would be enough. He thought: ‘What is true, will be true for everyone.’ But in this system there was no 𝘳𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. There was no 𝘥𝘢𝘢𝘥. It was one set of rules for believers, and another set of rules for nonbelievers. I watched some of the show trials on television, to see if I could find him. There were no lawyers, no witnesses, nothing. Just a few people with beards. They’d hand down vague sentences like ‘Crimes against God,’ which carried a sentence of death. We tried everything. We looked everywhere, we called everyone, but nobody knew where they’d taken him. Finally we were able to arrange a meeting with one of Iran’s highest ranking religious figures, Ayatollah Shariatmadari. We visited him at his house and pleaded with him to intercede. We told him: an innocent man has been arrested, one of the most honest men in all of Iran. There must be some justice. There must be some consideration of the truth. The Ayatollah was a good man. A man with 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘬𝘪. He was a man of faith, rather than a religious man. He listened with concern; we could see the compassion in his eyes. But there was nothing he could do. He’d already fallen out of favor with Khomeini; and a few months later he’d be arrested himself. After that there was no hope.”

هر بامداد با صدای شلیک تیربارانها بیدار میشدیم. اعدامها در ابتدا با شلیک مسلسلها آغاز میشد. سپس یک دور شلیکهای تکتیر تا یقین یابند که همه را کشتهاند. من دراز کشیده بر تخت شلیکها را میشمردم. زمانی که روزنامهی صبحگاهی به دستم میرسید، دنبال نامش میگشتم. دلم گرفته بود. بیاحتیاطی کرده، از پناهگاهش رفته بود، شوخی هم کرده، گفته بود: “اگر مرا دستگیر کنند، در دادگاه کمی میخندیم.” میدانست که کار خلافی نکرده است. تمام زندگیاش را نمونهی راستی و صداقت بود. فسادناپذیر بود. در این گمان که بیگناهیاش کافیست، میپنداشت که فرصتی برای بیان راستیها خواهد داشت. باور داشت: «حقیقت آنست که برای همگان پذیرفتنی باشد.» ولی در این نظام، نه راستی بود و نه داد. برای کافران و مؤمنان دو نوع عدالت وجود داشت. در جستجوی او دادگاههای نمایشی را تماشا میکردم. نه وکیلی، نه شاهدی. احکام ریشوها “محاربه با خدا” و “فساد در زمین” بود. تازه اگر دادگاهی هم تشکیل میشد. ما همهی راهها را آزمودیم. همه جا را برای پیدا کردن او جستجو کردیم. هیچکس چیزی نمیدانست. محسن پزشکپور دیداری با یکی از پرنفوذترین روحانیون ایران ترتیب داد. برای ملاقات آقای شریعتمداری به قم رفتیم. از او خواستیم که برای حفظ جان دکتر عاملی کاری کند. مرد خوبی بود. مرد نیکخویی. بیش از آنکه مذهبی باشد، مرد ایمان مینمود. با نگرانی سخنان ما را شنید. همدردی داشت. گفت سفارش میکند. کاری از دستش برنیامد. خمینی کینهتوز او را برنمیتابید. دیری نپایید که او را هم بازداشت و با او بدرفتاری کردند. دیگر هیچ روزنهی امیدی نمانده بود

(39/54) “It would have been suicide to fight. There were no...

(39/54) “It would have been suicide to fight. There were no courts to petition. No laws to challenge. The only weapon that we had left were our words. I joined together with five colleagues from the Pan-Iranist party, and we formed an underground journal. We met daily in an abandoned office. We wrote with pen and paper, and when each issue was finished it would be secretly printed by a friend that worked at a publishing house. I wrote under the name of Rahdmard. It was the same name Mitra and I would later give to our fourth child, who was born severely disabled. It means a man who is noble. A man who is morally upright. It’s what I wanted for him, and it’s what I wanted for myself as well. In my articles I never attacked the regime directly. I didn’t mention the executions. I never named any names. Instead I wrote about ideals and principles. 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪i. I said: ‘Let us not lose ourselves. Let us not descend back into darkness.’ We had no idea if our words were being read. Each issue would only be one thousand copies, and we’d only pass them out amongst our friends. But we were like a dying person who was desperate to live. If we wanted to survive, these were the breaths we had to take. Just being together gave us hope. Darkness was pressing in all around us. But coming together for a single purpose, a single goal, it gave our hearts energy. Each day we’d share the news we’d seen and heard. We talked about what we could do, how we could help. One of the members had been sheltering Dr. Ameli at his house. He’d been staying there since the first days of the revolution. But after several weeks he began to miss his wife and family. So he decided to leave the safehouse. He knew that he was innocent, so he took a chance. He went back home. And that’s where they grabbed him.”

(۳۹) پیکار با آنها خودکشی بود. امید چندانی برای نبرد مسلحانه نبود. دادگاهی برای دادخواست وجود نداشت. قانونی برای به چالش کشیدن نداشتیم. تنها کارمان نوشتن بود. همراه پنج تن از یاران پانایرانیست مجلهای زیرزمینی راه انداختیم. با کاغذ و خودکار مینوشتیم. مجله پنهانی به دست دوستی که در چاپخانه کار میکرد آماده میشد. از هر شماره تنها هزار نسخه. آن را میان دوستان پخش میکردیم. من با نام رادمرد می نوشتم. مرد آزاده و جوانمرد. راستکردار . مردی که آرزو داشتم باشم. این نام را برای چهارمین فرزندمان برگزیدیم. او بیمار زاده شد. آن ویژگیها را برایش میخواستم. در نوشتههایم به رژیم نتاختم. از اعدامها سخن نگفتم. نامی از کسی نبود. دربارهی آرمانها و بنیادها نوشتم. داد، راستی، آزادی. میخواستم خود را فراموش نَکُنیم، به تاریکی فرو نیفتیم. نمیدانستیم که نوشتههامان خوانده میشوند یا نه. تلاشهایی نومیدانه برای زنده ماندن بود. هر روز خبرهایی را که دیده و شنیده بودیم با هم در میان میگذاشتیم. دربارهی آنچه میتوانستیم انجام دهیم و کمکهایی که از دستمان برمیآمد، گفتوگو میکردیم. ما پشتیبان هم بودیم و برای آرمانی همگانی و هدفی مشترک همگام، و این به ما دلگرمی میداد. روزگاری بیمآمیز بود و همین با هم بودن امید میبخشید. نواری از آژیر با نیمرخی از چهر مهربانش بر آن که درفش شیر و خورشید نشان بر گردنش جنبان بود، جاکلیدی و سنجاقسینههایی با نشان شیر و خورشید، جزوهی «کار، تنها سند مالکیت و یگانه پاسدار آن» از کارهای آن روزهاست. یکی از دوستان از نخستین روزهای پس از شورش پناهگاهی برای دکتر عاملی فراهم کرده بود. دلتنگی همسر، فرزندان و دیگر گرامیانش او را از پناهگاه بیرون کشاند. او را در خانهی پدری دستگیر کردند.

(38/54) “I could not find it anywhere. The Iran of Shahnameh....

(38/54) “I could not find it anywhere. The Iran of Shahnameh. The Iran of Cyrus The Great. The Iran of Rumi, Hafez, Saadi, Khayyam. The Iran of our mothers and fathers. The Iran that I had loved since I was a little boy, it was no use to them. They didn’t care about our culture, our history, our ideals. One day Khomeini gave a speech saying that nationalism was against Islam. He said that we should be a nation of Muslims, not a nation of Iranians. The Lion and the Sun were removed from our flag, two of the oldest symbols of Iran. They were replaced by Arabic writing. Our institutions were dismantled one-by-one, until the only things left of the republic and constitution were their names. They became empty boxes that no one knew what was inside. Three months after the revolution I took one final trip to Nahavand. These were the people who trusted me most. Nobody could say that I’d ever wronged them. I wanted to speak with them freely, and share my thoughts. I wanted to see if they grieved along with me. Normally the moment that my car pulled into town, the news would spread like wildfire. People would gather at the house of my father. It had a very large salon, and people would come and go as they pleased. They’d come in excited, passionate, sometimes angry. They’d be critical. They’d debate me. Everyone had something to say. But this time only a small crowd gathered. And I was the only one who spoke. I shared all of my concerns: that we were losing our ideals. We were losing 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. We were losing 𝘕𝘦𝘦𝘬𝘪. We were losing 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. We were losing 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. But everyone just listened in silence. They knew my words were true. They knew better than me. But it was fear. They were silenced by fear. There is a famous parable about a caravan of one hundred merchants crossing the desert. Their camels are loaded down with riches. In the night they are overtaken by two bandits, and robbed of everything. Afterwards they are asked: ‘How could it possibly happen? There were one hundred of you, but only two of them.’ They replied: ‘Yes. But those two were together. And we were alone.”

آن را نمییافتم. ایران شاهنامه. ایران کوروش بزرگ. ایران خیام، مولانا، سعدی و حافظ. ایران مادران و پدرانمان. ایرانی که از کودکی دلبستهاش بودم. ارزشی برایشان نداشت. برای آنها فرهنگ، تاریخ و آرمانها بیارج بودند. خمینی گفت ملیگرایی بر خلاف اسلام است. گفت ما باید امت مسلمان باشیم، نه ملت ایران. نشان شیر و خورشید، دو نماد هزاران سالهی فرهنگ ایرانیان را از درفش ایرانزمین برداشتند، جایگزینش واژهای عربی بود. سازمانها و نهادها را فرو پاشاندند. به زودی دریافتیم که جمهوریت و قانون اساسیشان نامی بیش نبود، قالبی میان تهی. سه ماه پس از شورش، سفری به نهاوند داشتم. آنجا زادگاه گرامی من بود، مردمانش، ارجمندانی که دلبستهی هم بودیم. در زمانی کوتاه کارهایی برایشان کرده بودم. خواهان دانستن برخورد و برداشتشان بودم. آیا چون من افسرده و غمگین یا امیدوار، شاد و خشنودند. گفتوگو با آنان بایسته مینمود. پیشتر دیدن خودرو من آژیروار همه را خبر میکرد. در تالار خانه گرد میآمدیم . مردمی پرشور، هیجانزده، شاد، غمزده، آرام یا خشمگین میآمدند و میرفتند. بحث و انتقاد و درخواستهای شخصی و شهری از هرگونه پیش میآمد. رایزنیها برای همه آموزنده و دلنشین بود، امید در هوا موج میزد. ولی این بار تنها شماری اندک آمدند و تنها من بودم که سخن میگفتم. تمام نگرانیهایم را با آنها در میان گذاشتم. اینکه آزادیهایی را هم که داشتیم از دستمان میگیرند. راستی کاسته و کژی افزوده میشود. بیداد، بیداد میکند. دیدم همه خاموشند. دریافتم که همه همآواییم. آنچه زبانشان را بُریده، ترس است. از ترس دم درکشیده بودند. همه رفتند، جز یکی، دوستی که اسب و تفنگی هم داشت. گفت: “در شهر ناکسان در کارند، ناامن است .شب را به خانهی ما بیا، تنها نمان.” نگران من بود. چندان پافشاری کرد تا پذیرفتم. ایران سرزمین آزادگان و جوانمردان است! زبانزد پرآوازهای هست دربارهی کاروانی از سد بازرگان که از بیابان میگذشتند. بر شترهاشان بارهای گرانبها میبردند. شباهنگام دو دزد بر آنان شبیخون زدند و همهی داراییشان را دزدیدند. در آبادی از آنها پرسیدند: “چگونه پیش آمد؟ شما سد تن بودید و دزدان تنها دو تن.” پاسخ دادند: “زیرا آن دو تن با هم و ما سد تن تنها بودیم!”

September 14, 2023

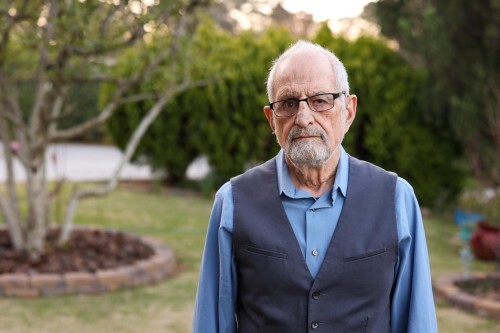

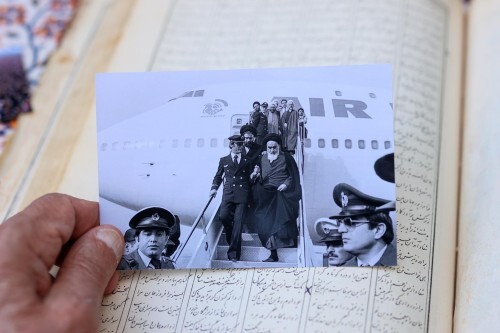

(33/54) “On the day Khomeini’s plane landed the road from the...

(33/54) “On the day Khomeini’s plane landed the road from the airport was lined with hundreds of thousands of cheering people. I hadn’t completely lost hope. The king was gone. But we still had a government, a parliament, a constitution. The only thing new was this man. Maybe he’d been telling the truth. Maybe he truly did want an open society. Khomeini had surrounded himself with liberal advisors. Maybe he’d allow them to run the country. Maybe he’d go to Qom and study his books. The parliament decided to form a small delegation to meet with him; to find out his plans. Since I’d been such a vocal member of the opposition, it was decided that I should go along. Khomeini had taken up residence in a school building directly behind the parliament. When we arrived we were escorted into an empty classroom. There was no furniture. Pillows and blankets were piled against the wall; it was clear that people had been sleeping there. After five minutes Khomeini entered the room. He was dressed all in black. After he took his seat we explained that we were hoping for a peaceful transition of power. One that kept the constitution intact, and the parliament in place. We presented a list of ministers that we thought he would approve. He listened in silence. At no point did he ask a question. At no point did he give a response. It was clear that he had no need for our participation. Power was in his hands. When we finished making our proposal, he asked us to deliver two messages. One: he wanted us to tell the military that they had his full support. And two: that no one would be harmed, except for the king. When asked later about his promises, he would claim that Islam allows lying in times of war.”

روزی که هواپیمای خمینی فرود آمد، سدها هزار نفر از فرودگاه تا شهر به پیشواز او آمده بودند. شاه رفته بود. اما هنوز دولت، مجلس و قانون اساسی بر جای بودند. تنها مهرهی جدید، یک روحانی بود. شاید راست بگوید؟ شاید به راستی خواهان جامعهای آزاد باشد؟ خمینی را مشاوران لیبرال احاطه کرده بودند. شاید اجازه دهد آنها کشور را اداره کنند؟ شاید به قم میرفت و سرگرم خواندن کتابهایش میشد؟ گروه اقلیت مجلس تصمیم گرفت پنج نفر را برای ملاقات با او و آگاهی از برنامههایش تشکیل دهد. من یکی از آن پنج تن بودم. خمینی در مدرسهای پشت مجلس اقامت داشت. وقتی وارد شدیم، ما را به کلاسی خالی هدایت کردند. هیچگونه اسباب و اثاثی در اتاق نبود. روشن بود که از آن اتاق برای خواب استفاده میشد زیرا بالشها و تشکهایی کنار دیوار انباشته شده بودند. پس از پنج دقیقه خمینی وارد اتاق شد. جایی نشست. به او گفتیم که ما امیدوار به جابهجایی صلحآمیز قدرت هستیم. انتقالی که قانون اساسی را حفظ کرده و مجلس را در جای خود نگه دارد. او در سکوت سخنان ما را شنید. هیچ پاسخی نداد. هیچ پرسشی نکرد، نیازی به مشارکت نداشت. تمام قدرت را یکجا میخواست. از ما خواست دو پیام را به بیرون برسانیم. نخست به سران ارتش بگوییم که خمینی خواهان بالا بردن احترام آنهاست و دوم آنکه هیچ کسی جز شاه مجازات نخواهد شد. دیری نپایید که دروغ گفتن را در هنگام جنگ روا دانست

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers