Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 7

September 12, 2023

(12/54) “She was brave in many ways. But there were three things...

(12/54) “She was brave in many ways. But there were three things that Mitra feared most: darkness, silence, and being alone. In Germany we’d take long walks through the countryside. Mitra couldn’t stand the quiet. She’d recite entire poems back-to-back-to-back. At the time she’d gotten into modern poetry. Her favorite poet was a young woman named Forough Farrokzhad. Mitra had many of her poems memorized. Farrokzhad was a modern poet. She wrote in free verse. She wrote from a feminine perspective. And she wrote about everything, including sex. By the time we finished Shahnameh I think I’d destroyed Mitra’s interest in the book. The book’s longest section is the historical section. Here the heroic nature of the prose fades. There are no more dragons. No more Rostam and Gordafarid. Here Ferdowsi writes about real people. He must stick to what is known. You can’t turn a real person into a mythic hero. That summer I took a road trip home to Iran. The Shah had just announced his White Revolution. It was a sweeping campaign of reform. Women were given the right to vote. Factory workers gained a share in profits. Agricultural estates were seized and redistributed to the sharecroppers who worked the fields. With a single stroke of his pen, the Shah gave more freedom to millions of Iranians. But not everyone supported it. When I arrived in Tehran the city was in chaos. Several buildings on my street were in flames. A cleric named Khomeini had come out against The White Revolution, and he’d ordered his followers to riot. Khomeini practiced a different kind of Islam. This was not the Islam of our fathers. This was not the Islam of the Persian Mystics. This was an Islam of cutting off hands, death for nonbelievers, and oppression of women. We thought these things were demons from our history. Monsters buried far in our past. But there’s a parable in 𝘔𝘢𝘴𝘯𝘢𝘷𝘪, where Rumi writes about a dragon frozen in a block of ice. The dragon seems to be dead. So the people place him on a cart and wheel him into the center of the city. They’ll soon discover that he’s still alive. He was only sleeping, waiting for things to heat up.”

میترا در بسیاری کارها بیباک بود ولی از سه چیز میترسید: تاریکی، سکوت و تنهایی. در آلمان به پیادهرویهای طولانی پیرامون شهر میرفتیم. میترا تحمل خاموشی را نداشت. پی در پی شعرهایی را به طور کامل میخواند. در آن هنگام شاعر دلخواه او فروغ فرخزاد بود. فرخزاد شاعری نوگرا بود. او شاعر سبک نو بود. شعرهای او دیدگاههای زنانه داشتند. در هر زمینهای مینوشت، حتا سکس. قشر مذهبی جامعه، او را زنی هرزه میخواند. میترا بسیاری از شعرهای او را به یاد سپرده بود. یک سال طول کشید تا شاهنامه را با هم خواندیم. هنگامی که خواندن را به پایان رساندیم، فکر میکنم از دلبستگیاش به شاهنامه کاسته بودم. بلندترین بخش کتاب بخش تاریخی آن است. در اینجا، سرشت حماسی سخن کمرنگ میشود. دیگر خبری از افسون و جادو نیست. از اژدها. از رستم و گردآفرید. در این بخش، فردوسی دربارهی انسانهای واقعی مینویسد. هنگام نوشتن تاریخ باید به واقعیتها پایبند بود. نمیتوان شخصی عادی را به پهلوانی اسطورهای تبدیل کرد. درآن تابستان، سفری زمینی به ایران داشتم. شاه به تازگی انقلاب سفید را اعلام کرده بود. یک کارزار فراگیر اصلاحات بود. زمینهای کشاورزی زمینداران بزرگ به بهایی اندک به کشاورزانی که روی آن کار میکردند داده میشد. زنان از حق رأی برخوردار میشدند. سهمی از سود کارخانهها به کارگران میرسید. در یک رفراندم به میلیونها ایرانی آزادی بیشتری رسید. اما همه از آن پشتیبانی نمیکردند. هنگامی که به تهران رسیدم، چندین ساختمان را آتش زده بودند. یک روحانی به نام خمینی علیه انقلاب سفید قیام کرده و به پیروانش دستور شورش داده بود. خمینی به گونهی دیگری از اسلام باور داشت. این اسلام پدران ما نبود. این اسلام عارفان ایرانی نبود. این اسلام بریدن دستها و کشتن آزادیخواهان و ستمگری علیه زنان بود. اینها را اهریمنانی برخاسته از تاریخمان میپنداشتیم. دیوهایی که در سالهای دور به خاک سپرده بودیم. مولانا حکایتی در مثنوی دارد که در آن اژدهایی در تکه یخی منجمد شده است. گویی که مُرده است. از این رو، مردم آن را بر ارابهای نهاده و به مرکز شهر میبرند. ولی بزودی در مییابند که اژدها هنوز زنده است. تنها در خواب بوده است و در آرزوی گرما. مرده بود و زنده گشت او از شگفت / اژدها بر خویش جنبیدن گرفت

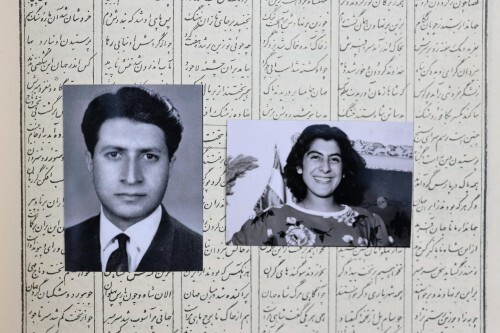

(11/54) Before our wedding Mitra’s father gave her one final...

(11/54) Before our wedding Mitra’s father gave her one final piece of advice: ‘Never let a man enforce his opinions on you.’ And she took it to heart. She was my opposite. My antithesis. The hardest for me to convince. She would tell me I was too optimistic. She’d say that I only saw the best in things, whether that be people, Iran, or Shahnameh. After our marriage I finally convinced her to read it with me. We’d just moved to Germany so that I could attend university. Each night when I came home from class, she’d lay her head in my lap and I’d read her a chapter. It was my second time reading the book all the way through. My first time as an adult. As a boy I’d always been drawn to Rostam’s feats of strength: his taming of Rakhsh, his defeat of the demon king, his slaying of the dragon. But now I noticed something else. Rostam lived by a code. He would not serve an evil king. He would only serve his ideals. 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. Justice. 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. Truth. And most of all, 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. Freedom. Rostam would never sacrifice his freedom. The great champions of Shahnameh were more than warriors, they were vessels for our ideals. Even in the darkest times, even in the times of greatest danger, they lived by their code. I did my best to interest Mitra in certain parts. When I came to the story of the female knight Gordafarid, I quickened my pace. I filled my words with excitement: ‘The battle was nearly lost. Gordafarid’s commander had been captured on the battlefield. Her castle was completely surrounded by the enemy. Gordafarid tried to rally the men to fight, but none would join her. They wanted to stay behind the castle walls. They wanted to surrender. Gordafarid’s cheeks turned black with rage. She grabbed her bow and arrow, tied her hair beneath her helmet, and rode out to face the enemy alone. She stopped just short of the enemy lines, and like a lion she roared: 𝘞𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘮𝘱𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴?’ In the heat of the story, I peeked down at Mitra to see if she was scared. But she’d fallen asleep.”

پیش از ازدواجمان پدر میترا آخرین اندرز را به او داد: «هرگز اجازه نده مردی به تو زور بگوید.» و او آن درس را جانانه پذیرفته بود. و ما در تمام زندگیمان چنین بودهایم. او همواره آنتیتِز من بوده است. نقطهی مقابل من. سرسختترین کس برای متقاعد شدن. میگفت بیش از اندازه آرمانخواهم، بیش از اندازه ناآزموده و بیش از اندازه باورمند. میگفت که من همیشه بهترین را در هر چیزی میبینم، چه مردم باشد، چه ایران و چه شاهنامه. پس از ازدواجمان سرانجام توانستم او را راضی کنم که همراه من شاهنامه بخواند. دوران دانشجویی را در آلمان زندگی میکردیم. و هر شب که از دانشگاه به خانه برمیگشتم، سرش را روی پاهایم میگذاشت و من بخشی از شاهنامه را برایش میخواندم. این دومین بار بود که شاهنامه را از آغاز تا پایان خواندم. نخستین بار در بزرگسالی. در کودکی همواره شیفتهی نبردهای رستم بودهام: رام کردن رخش، شکست دیوان، کشتن اژدهای پیدا و پنهان. ولی آن روز به نکتهی دیگری پی برده بودم. رستم برپایهی یک قانون زندگی میکرد. او به پادشاه ستمگر خدمت نمیکرد. او تنها به راه آرمانهایش میکوشید: داد، راستی و بالاتر از همه، آزادی برایش ارجمندترین بود. رستم هرگز از آزادیاش نمیگذشت. پهلوانان بزرگ شاهنامه فراتر از جنگجویانی نیرومند بودند. آنها نگهدارندهی آرمانهایمان بودند. حتا در تاریکترین زمانها، حتا در بزرگترین خطرها، پیرو قانون پهلوانی خود بودند. من بیشترین تلاش خود را میکردم که میترا را دلبستهی بخشهای ویژهای از شاهنامه کنم. هنگامی که به داستان گردآفرید رسیدم، شتابم را بیشتر کردم. واژگان را با شور بیشتری خواندم. دژ سپید به محاصرهی دشمن درآمده بود، هجیر نگهبان دژ بود. به جنگ سهراب رفت و به کمند او گرفتار شد. هنگامی که گردآفرید آگاه شد، گونههایش از شدت خشم به سیاهی گرایید: چنان ننگش آمد ز کار هجیر / که شد لالهرنگش به کردار قیر. پس تیر و کمان خود را برداشت. گیسوانش را به زیر کلاه خود گرد آورد، و یکه و تنها بر دشمن تاخت. به نزدیکی سپاه دشمن ایستاد و چون شیر غرید: به پیش سپاه اندر آمد چو گرد / چو رعد خروشان یکی ویله کرد / که گردان کدامند و جنگآوران / دلیران و کارآزموده سران. در اوج داستان نگاهی زیرچشمی به میترا انداختم تا ببینم که آیا ترسیده است. او به خواب رفته بود

September 11, 2023

(9/54) “The club was called 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰 The Force. There were ten of...

(9/54) “The club was called 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰 The Force. There were ten of us. We were all so different. But we were like charms on a bracelet, united by our love for Iran. It was nothing important: we’d graffiti our slogans onto walls. We’d stand on busy street corners and try to convert people to our cause. But it felt so important. We felt like we were building a new Iran around us. We held our meetings in an attic. We’d check the street for spies before we went inside. I had one of the strongest voices in the group, so I’d open each meeting by reciting a hymn about loving Iran. We’d review our activities from the previous week. Then Dr. Ameli would lead us in long discussions about the meaning of Iran. Dr. Ameli was a nationalist. But it wasn’t a nationalism of expansion. It was a nationalism of preservation. A nationalism based on history and culture, with respect for all people. That’s one of the very first things he taught us: ‘What is true, must be true for everyone.’ We learned that the Persian Empire began when Cyrus The Great united a group of nomadic tribes in 550 BC. Many consider Cyrus to be the founder of human rights. Whenever he conquered a new territory, he outlawed slavery. He allowed everyone to live with their own language and religion. In the ancient world Iranians were known as 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘦𝘩. Free people. It’s even in the Shahnameh. When one of our champions is mistaken for an angel, he says: ‘I come from Iran. The land of the free.’ Listening to Dr. Ameli speak about the foundations of Iran, we felt like we’d discovered something hidden. An Iran built on ideals. 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪. 𝘕𝘦𝘦𝘬𝘪. 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. An Iran built on freedom. 𝘈𝘻𝘢𝘥𝘪. During the final meetings of 𝘕𝘪𝘳𝘰𝘰 that I ever attended, we were joined by a girl named Parvaneh. She was a basketball player; and her voice was just as strong as mine. At the close of each meeting, we’d lead the group in the swearing of seven oaths. I don’t remember all seven, but I remember the final. To give our lives for Iran.”

گروه خود را نیرو مینامیدیم. ده تن بودیم با ویژگیهای گوناگون ولی چون مهرههای یک دستبند - پیوسته و همپیمان در عشق به ایران. کارهای برجستهای نمیکردیم: شعارهامان را بر دیوارها مینوشتیم. در خیابانهای پر رفت و آمد ایستاده و رهگذران را با آرمانهامان و برای پیوستن به کوششها فرامیخواندیم. اندیشهها را با همگان در میان میگذاشتیم. این تلاشها برایمان بسیار با ارزش بود. احساس میکردیم در حال ساختن ایرانی نو در پیرامون خود هستیم. گردهمآییها را در بالاخانهای برگزار میکردیم. پیش از ورود، ایمنی خیابان را بررسی میکردیم. گردهمآیی هفتگی ما با خواندن نیایشگونهای به نام سرآغاز شروع و با پیماننامهای به نام هفت پیمان به پایان میرسید. بسیار پیش میآمد که من یکی از آن دو را با صدای رسا بخوانم. کوششهای هفتهی پیش را دوره میکردیم. آنگاه آژیر با ما به گفتوگو دربارهی ایران و فرهنگ آن میپرداخت. آژیر ملیگرا بود. نه ملیگرایی بر پایهی کشورگشایی بلکه ملیگرایی بر پایهی پاسداری از یگانگی سرزمینی و فرهنگ ملی. ملیگرایی بر پایهی تاریخ و فرهنگ، بر پایهی گرامیداشت همهی مردمان زمین و میهنها و فرهنگهایشان. این نخستین درسی بود که به ما آموخت: «حقیقت آنست که برای همگان پذیرفتنی باشد.» آموختیم که بنیاد شاهنشاهی ایران با یکپارچه کردن قومها و تیرههای گوناگون به رهبری کوروش بزرگ در سال ۵۵۰ پیش از میلاد نهاده شد. بسیاری کوروش بزرگ را بنیانگذار حقوق بشر میدانند. او به مردمان آزادی داد که با زبان و دین خود زندگی کنند. و هرگاه بر سرزمینی نو میرسید، بردگان و اسیران را آزاد میکرد. در دنیای باستان، ایرانیان با نام “آزاده” شناخته میشدند، مردمان آزاد. در شاهنامه نیز به این نامگذاری اشاره شده است. منیژه بیژن را میبیند و به او دل میبندد. میپرسد آیا تو سیاوشی که زنده شدهای یا از پریزادگانی؟ پاسخ بیژن این است: سیاوش نیَم نَز پریزادگان / از ایرانم از شهر آزادگان. سخنان آژیر دربارهی بنیادهای فرهنگ ایرانیان دل و دیدهی ما را بر گذشته و آیندهی ایران میگشود، احساس میکردیم به رمز و رازهای ماندگاری آن دست یافتهایم. ایرانی ساخته شده بر پایهی آرمانها: راستی، نیکی و داد. ایرانی ساخته شده بر پایهی آزادی. در یکی از واپسین گردهمآییها، تنی چند از دختران دانشآموز به ما پیوستند. در میان آنها دختری بود به نام پروانه، بسکتبال بازی میکرد؛ صدایی رسا و گیرا داشت. ایستادیم و در پایان گردهمآیی هفت پیمان را خواندیم. آخرین بند هفت پیمان از جان باختن به راه ایران میگوید

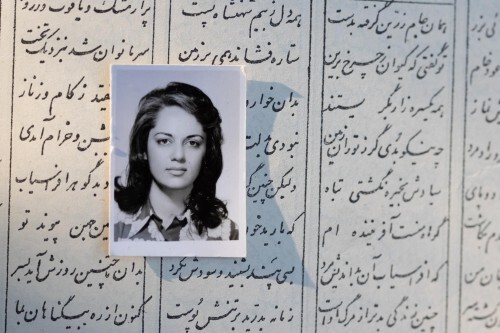

(8/54) “There’s only one way for love to begin in a traditional...

(8/54) “There’s only one way for love to begin in a traditional society. With the eyes. At the dinner table Mitra disagreed with everything I said. If I said ‘red,’ she said ‘green.’ If I said ‘spice,’ she said ‘sweet.’ But there was something between us. I could see it in the eyes. It was like glancing at a beautiful mountain from afar. The mountain hasn’t been experienced yet. Its cliffs have not been climbed. Its flowers have not been picked. But you are drawn to its beauty, even at a distance. On her fifteenth birthday I got her flowers. It was winter. There weren’t many flowers during winter. So I went to an Armenian flower shop and got fifteen white carnations, with one red in the center. I was shy with my words, so I wrote her a long letter. I told her the story of the female knight Gordafarid, one of the bravest champions in all of Shahnameh. Gordafarid was a master of archery. No bird could escape her arrows. And she was beautiful: her face glowed like the moon. Her waist was cypress-shaped. Her hair was worthy of a crown. I told Mitra: ‘She’s just like you. Together we can do great things for Iran!’ Mitra hid the letter from her father. One night over dinner I told him about my plans to become king. I told him that I would use my voice, and speak about 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. Justice. He said: ‘This boy is delusional! He’s living in a thousand-year-old book!’ He told me that Iran was a constitutional monarchy. And unless I planned to lead a coup, the highest I could rise was Prime Minister. He said that Iranians were too worried about survival to care about ideals. So if I wanted to be Prime Minister, I’d need to put away childish ideas and learn about the real world. A few weeks later I joined a club of students at my school who met each week to discuss politics. It was the youth chapter of a new party called the Pan-Iranist Party. The leader of the club was a medical student from the University of Tehran. His name was Dr. Mohammadreza Ameli Tehrani. But everyone called him by his nickname: The Siren.”

در جامعهی سنتی تنها یک راه برای ابراز دلبستگی هست. آن هم راه نگاه. سر میز شام میترا با هر آنچه میگفتم مخالفت میکرد. میگفتم سرخ، می گفت سبز. میگفتم تند، می گفت شیرین. ولی حسی میان ما در حال شکفتن بود. میتوانستم در دیدگانش ببینم. مانند تماشای کوهی در دوردست. کوهی که هنوز آزموده و پیموده نشده است. صخرههایش هنوز پیموده و گلهایش هنوز چیده نشدهاند. ولی میشد از دور پیوندی گیرا را احساس کرد. در پانزدهمین زادروز میترا به او دسته گلی هدیه کردم. زمستان بود و در زمستان گلهای زیادی یافت نمیشد. به یک گلفروشی ارمنی رفتم و پانزده گل میخک سفید و یک میخک سرخ در میانشان، خریدم. از سخن گفتن خجالت میکشیدم. از این رو نامهی بلندی برایش نوشتم. داستان زن پهلوانی را به نام گردآفرید برایش بازگفتم. گردآفرید از دلیرترین پهلوانان شاهنامه است. تیرانداز چیرهدستیست. هیچ پرندهای را یارای رهایی از تیرش نیست. زیباست: رخسارش چون خورشید درخشان، سر و گیسوانش شایسته و درخور تاج. رها شد ز بند زره موی او / درخشان چو خورشید شد روی او / بدانست سهراب کاو دختر است / سر و موی او از در افسر است. به میترا گفتم: «به راستی که مانند توست! همگام با هم میتوانیم کارهای ارزشمندی برای ایران انجام دهیم.» میترا نامه را از پدرش پنهان کرد. شبهنگام آرزویم را برای شاه شدن با پدر میترا در میان گذاشتم. به او گفتم که سخنانم، صدای دادخواهی همهی ایرانیان خواهد بود. گفت: «این پسر رؤیاییست! او در کتابی هزارساله زندگی میکند!» به من گفت مگر آنکه نقشهای برای کودتا داشته باشم وگرنه بالاترین جایگاهی که میتوانم به آن دست یابم نخست وزیریست. و ایرانیان بیش از آنکه در اندیشهی آرمان باشند، نگران زنده ماندنند. چنانچه بخواهم نخستوزیر شوم، باید خیالهای کودکانه را کنار بگذارم و به دنیای راستین بیندیشم. چند هفته پس از آن دیدار، به گروهی از دانش آموزان دبیرستان که گردهمایی سیاسی هفتگی داشتند پیوستم. این گروه شاخهی جوانان حزب نوپایی بود که پانایرانیست خوانده میشد. رهبر گروه، دانشجوی پزشکی دانشگاه تهران بود. نامش محمدرضا عاملی تهرانی. ولی همه او را با نام مستعارش صدا میزدند: آژیر

(7/54) ”In Shahnameh there’s one word that Rostam uses more than...

(7/54) ”In Shahnameh there’s one word that Rostam uses more than any other: 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥. Justice. 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥 is a simple concept. It means that everyone gets what they deserve: both good and bad. Everyone gets a fair share. The Nahavand of my childhood was very poor. People would come to our door each day asking for a single piece of bread. It seemed unjust to me. So I decided I would not eat more than that. My mother begged and begged, but I would not do it. I decided that if I became king, every child in Iran would be given their fair share. But until then I should participate in their suffering. I had no idea how I would become king. In Shahnameh it seemed so simple. Good kings glowed with light. Their wisdom was plain for all to see. I was an optimistic child. I felt that if I could use my voice, and speak about 𝘋𝘢𝘢𝘥 —then a path would open up before me. When I turned fifteen I went to boarding school in Tehran. It was nothing like Shahnameh. Half a million people lived there, and it was a time of great upheaval. A huge debate was being held over the nationalization of oil. The streets were filled with voices of every kind, and nobody could agree on the future of Iran. I realized that many people didn’t want the same things that I wanted, and for complicated reasons. At the end of each week I’d go to the house of a relative to pick up my allowance. His wife was the first person in Iran to have a cooking show on the radio, so sometimes I’d stay for dinner. They had a young daughter named Mitra. Her hair was cut short in the style of a famous American actor. One of her hands was crippled by polio. She was very shy about it, but it was never something I noticed. Back then most Iranian girls were modest and deferential, but not Mitra. And she argued with everyone: her friends, the help, her family, and me. One night over dinner I started speaking about the past greatness of Iran: who we were. Back in the days of Shahnameh. When I finished talking, Mitra was the first to speak. She said: ‘You talk about Iran like it’s a lion. But it’s a cat.” That was the year I discovered something new. There are love stories in Shahnameh too.”

واژهای که رستم بیش از همهی واژگان به کار میبرد: داد است. عدالت. مفهومیست ساده. بدین معنا که هر کس هر آنچه را شایستهاش هست، دریافت میکند. هم نیک و هم بد. رستم میگوید: جهان را همه سر به سر گشتهام / بسی شاه بیدادگر کُشتهام. فقر در نهاوند کودکیام زیاد بود. هر روز میشد تنی چند به خانهمان بیایند و تکه نانی درخواست کنند. غمگین بودم. بر آن شدم که برای همدردی با آنان تکه نانی بیش نخورم. مادرم بارها خواهش کرد، ولی من خودداری میکردم. میاندیشیدم که اگر شاه بودم هر کودکی در ایران به سهم عادلانهی خود میرسید. امروز تنها میتوانم در رنج آنها شریک باشم. هیچ اندیشهای دربارهی چگونگی پادشاه شدن نداشتم. در شاهنامه دنیا بسیار ساده به نظر میآمد. شاهان خوب در هالهای از نور میدرخشیدند. خردشان بر همه آشکار بود. من کودکی خوشبین بودم. بر آن بودم که اگر از عدالت بگویم، راهی پیش رویم باز خواهد شد. در پانزدهسالگی، راهی مدرسهی شبانهروزی البرز در تهران شدم. تهران شباهتی به شهرهای شاهنامه نداشت. نیم میلیون نفر در آنجا زندگی میکردند، و آن روزها هنگامهی دگرگونیهای بزرگ بود. کارزاری گسترده پیرامون ملی کردن نفت در سراسر کشور برپا بود. خیابانها پر بود از صداهای ملیها، ملیگراها و کمونیستها. روشنایی و تاریکی درهم آمیخته بودند. به دلایلی پیچیده بسیاری از مردم با آرمانهای من همراه نبودند. پایان هر هفته، به خانهی یکی از خویشان میرفتم تا کمک هزینهی هفتگیام را دریافت کنم. همسرش نخستین زنی بود که در ایران برنامهی آموزش آشپزی رادیویی داشت، گاهی برای شام میماندم. دختر نوجوانی داشتند به نام میترا. موهایش را مانند یک بازیگر مشهور آمریکایی کوتاه کرده بود. دست چپش به دلیل بیماری فلج اطفال اندکی ناکار بود. میکوشید آنرا بپوشاند. من آنرا نادیده میگرفتم، به نگاه من چیزی از ارزشهای او نمیکاست.در آن زمان بیشتر دختران ایرانی سربهزیر و خجالتی بودند، ولی میترا اینگونه نبود. او با همه بحث میکرد: با دوستانش، با خدمتکاران، خانوادهاش و من. شبی هنگام شام، از بزرگیهای ایران باستان گفتم. و اینکه در روزگار شاهنامه چه بودهایم. و چگونه میتوانیم دوباره آن بزرگیها را بازیابیم. پس از سخنانم، میترا پیش از همه چنین گفت: «تو از ایران به مانند شیری سخن میگویی. ولی ایران گربهای بیش نیست.» در همان سال بود که حس تازهای در من جان میگرفت. شاهنامه داستانهای عاشقانه هم دارد

(6/54) “One New Year our whole family took a bus to Qom, one of...

(6/54) “One New Year our whole family took a bus to Qom, one of the holiest cities in Iran. When we arrived in the city it was like stepping back in time. This was a different kind of Islam. It wasn’t my father’s. It wasn’t even my mother’s. It was an Islam from fourteen hundred years ago. The bookstores only stocked religious books. There were no radios, no music. My nine-year-old sister tried to buy some glass bracelets at the bazaar, but the shopkeeper wouldn’t serve her. Because she wasn’t wearing a hijab. When he turned his back I broke the bracelets against the table. In the afternoon I was given time to explore on my own. I remember I was wearing long pants. I’d never worn long pants before, so I felt like a man. I made my way to the biggest shrine in the city. There was a huge crowd for the holiday. As I pushed my way through, the crowd began to sway and move. People began to shout all around me. Hats were thrown in the air. I couldn’t see what was happening, even when I stood on the tips of my toes. But suddenly the crowd began to part. If I’d been one step further back, it would never have happened. But a path opened up in front of me. And there he was. I’d seen his portrait every day of my life on the inside cover of my Shahnameh: Mohammed Reza Shah. The king of Iran. He was not yet the famous Shah that he’d one day become. At the time he was still a young man. But on that day he seemed to me like one of the great kings of Shahnameh. I was a shy child, but something came over me. I broke free from the crowd and began to follow him. He took off his shoes, I took off my shoes. He entered the shrine, I entered the shrine. This was my chance. I’d never been so close to a king. I knew I had to do something, so I reached out. And I touched his coat. I touched the coat of a king. That night when I came home I looked at myself in the mirror. Ferdowsi describes Rostam as having the height of a cypress. And arms that could rip rocks from the side of a cliff. I took one look at my scraggly body, and decided I was much too skinny to be a knight. But my garden was the best, it was plain for all to see. So I decided I would become the shah of Iran.”

یک سال برای نوروز، همراه خانواده با اتوبوس به قم رفتیم - یکی از دو شهر مهم مذهبی ایران. هنگامی که به قم رسیدیم، انگار به گذشتههای دور بازگشته باشیم. گونهی دیگری از اسلام بود. اسلام پدرم نبود. اسلام مادرم هم نبود. اسلام هزار و چند سد سال پیش بود. کتابفروشیها تنها کتابهای دینی داشتند. موسیقی نبود. خواهر کوچکم میخواست چند تا دستبند شیشهای ارزان از بازار بخرد، ولی فروشنده از فروش به او خودداری کرد، چون حجاب نداشت. پس از اینکه فروشنده پشتش را به ما کرد دستبند را روی میز انداختم و شکست. بعد از ظهر آن روز اجازه گرفتم به تنهایی شهر را بگردم. به یاد دارم که شلوار بلند پوشیده بودم. پیش از این شلوار بلند نپوشیده بودم و احساس مردانگی میکردم. راه حرم را پیش گرفتم. انبوه مردم برای تعطیلات نوروزی در حرم گرد آمده بودند. به دشواری وارد صحن شدم، ناگهان تکاپویی میان مردم افتاد، جا به جا شدند. دور و بریهایم هورا میکشیدند. کلاههایی به هوا پرتاب میشد. روی نوک پاهایم ایستادم، در کلاس در شمار کوتاهقدها بودم، نمیتوانستم ببینم چه رخ داده است. ناگهان مردم از هم جدا شدند. اگر تنها یک گام عقبتر میبودم چیزی برایم رخ نمیداد. مسیری در برابرم باز شد. او آنجا بود. چهرهاش را هر روز در داخل جلد شاهنامهام میدیدم: محمدرضا شاه پهلوی، پادشاه ایران از کنارم گذشت. هنوز شاه پرآوازهای که در آینده شد، نبود. در آن هنگام او مردی جوان بود. ولی در آن روز او برایم مانند یکی از شاهان شاهنامه بود. من که همیشه کودکی خجالتی بودم، ناخودآگاه، در یک آن از جمعیت جدا شدم و او را دنبال کردم. کفشهای خود را درآورد، من هم کفشهایم را درآوردم. وارد آستانهی حرم شد، دنبالش کردم. کودک خجالتی برای دقیقهای چند از پوستهی همیشگی خود درآمده بود. میبایست کاری انجام میدادم که ارزش تعریف کردن داشته باشد، پس دستم را دراز کردم و پایین کتش را یکدم با دو انگشت گرفتم و رها کردم. سپس با شتاب به خانه برگشتم تا این پیشآمد را برای همه تعریف کنم. خود را در آینه نگاه کردم. فردوسی رستم را پیلتن مینامد، با چنگی که سنگ خارا را موم میکند. اگر سنگ خارا به چنگ آیدش / شود موم و از موم ننگ آیدش. نگاهی به خود انداختم و دانستم که بسیار لاغرتر از آنم که بتوانم پهلوان شوم. ولی باغچهام بهترین باغچه بود، زیباییاش بر همگان آشکار. آرزوی شاه شدن برآوردنیتر مینمود

(5/54) “The meaning of our most important words I learned from...

(5/54) “The meaning of our most important words I learned from my mother. 𝘙𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪: Truth. I never heard her tell a lie. 𝘕𝘦𝘦𝘬𝘪: Goodness. I never heard her gossip. And 𝘔𝘦𝘩𝘳: Love. We were three brothers and five sisters, but she loved us all equally. There were no assigned places at our dinner table. Everyone got their desired portion. While we ate our father would encourage us to debate the events of the day. No topic was off limits: history, politics, even the existence of God. And everyone was encouraged to use their voice. One weekend my father drove us all to visit Ferdowsi’s tomb in the city of Tus. It’s a large tomb. It’s modeled after the tomb of Cyrus The Great. On its face is etched the first line of Shahnameh. The master verse. The cornerstone: ‘In the Name of the God of Soul and Wisdom.’ 𝘑𝘢𝘢𝘯 and 𝘒𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘢𝘥. Soul and Wisdom. The two things that all humans have. With the opening line Ferdowsi does away with all castes and classes. He does away with all religion. He gives everyone a direct connection to the creator. As a young boy I’d memorized hundreds of verses. One of my favorite stories in Shahnameh is when Rostam selects his horse. Rakhsh is the only horse in Iran that can carry Rostam’s weight. Rakhsh has the body of a mammoth. But he’s wild, he foams at the mouth. Rostam has to fight to tame him. I was a shy child. But something happens when I read Shahnameh. There’s an epic cadence. The words demand to be spoken. It’s like touching a hot stove. I feel the heat, I feel the pressure. It’s like a sword pierces my body and I have to let it out: ‘𝘙𝘢𝘬𝘩𝘴𝘩 𝘳𝘰𝘢𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘦𝘯𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘩 𝘙𝘰𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘮!’ The neighbors would come running to their balconies to watch. Every region in Iran has its own dialect, and I could switch between them. The language is ancient, so I didn’t know the meaning of every word. But I could feel the music. When I mispronounced a word, I knew. As if I’d played a wrong chord. I could almost tell what he wanted. I could almost hear the voice of Ferdowsi himself.”

معنای مهمترین واژگان زبانمان را از مادرم آموختم، راستی، هرگز دروغی از او نشنیدم. نیکی، هرگز غیبت نمیکرد و مهر و دوستی. ما سه برادر و پنج خواهر بودیم و مادر همه را به اندازهی مساوی دوست داشت. برای هیچکس جایگاه ویژهای بر سر سفره در نظر گرفته نمیشد. هر کسی به میل و اندازهی خود از خوراک سهم میبرد. هنگام خوردن پدر تشویقمان میکرد که دربارهی رویدادهای روز گفتوگو کنیم. هیچ موضوعی قدغن نبود: تاریخ، سیاست، حتا وجود خداوند. و همه تشویق میشدند که اندیشههای خود را بیان کنند. پدر ما را یک هفته به دیدن آرامگاه فردوسی در شهر توس برد. آرامگاهی بود بزرگ. بسان آرامگاه کوروش بزرگ طراحی شده است. نخستین بیت شاهنامه بر روی سنگ آرامگاه حک شده بود. شاهبیت است. پایه و ستون اندیشه و جهانبینی ایرانیست: به نام خداوند جان و خرد. دو چیزی که همهی مردمان از آن برخوردارند. در نخستین برگ شاهنامه، فردوسی همهی طبقات اجتماعی را کنار مینهد. همهی دینها را کنار مینهد. فردوسی به مردمان پیوندی بیواسطه با خداوند میبخشد. او میگوید: هر آنچه در این کتاب است، برای همگان است. در کودکی سدها بیت شاهنامه را به یاد سپرده بودم. از داستانهای مورد علاقهام در شاهنامه جاییست که رستم اسبش، رخش را برمیگزیند. رخش تنها اسبیست در ایران که میتواند رستم و جنگ افزار سنگینش را تاب بیاورد. رخش تنی بسان پیل دارد. سرکش است، رستم برای گرفتن و رام کردنش میبایست سخت بکوشد. من کودکی خجالتی بودم. ولی زمانی که شاهنامه را میخواندم، شور شگفتانگیزی مرا فرا میگرفت. شعرها آهنگی رزمی دارند. واژگان خواستار خوانشاند. همانند دست زدن به کورهای گرم. گرما را حس میکنم، فشار را حس میکنم. همانند شمشیری که تنم را میشکافد و باید آن را فریاد بزنم: از این سو خُروشی برآورد رَخش / وزآن سوی اسب یل تاجبخش. همسایگان شتابان بر روی بامهاشان جمع میشدند تا شنوندهی فردوسی باشند. هر منطقهای از ایران گویش و لهجهی خود را دارد. من داستانهای شاهنامه را به فارسی و گویشهای محلیمان میخواندم. کتاب به زبان پارسی کهن سروده شده است، معنای همهی واژگان را نمیدانستم ولی آهنگش را حس میکردم. اگر واژهای را اشتباه میخواندم، درمییافتم. چنانکه گویی نُت موسیقی را اشتباه زده باشی. میتوانستم به درستی بدانم که او چه میخواهد بگوید. گویی صدای دلآویز فردوسی را به جان میشنیدم

(4/54) “My father named me Parviz, after one of Iran’s ancient...

(4/54) “My father named me Parviz, after one of Iran’s ancient kings. His story comes at the end of Shahnameh, in the historical section. Parviz was a good king. Not a great king, but a good king. His reign was a golden age of music. But he made many mistakes. His grandson Yazdegerd would be the last king of the Persian Empire. Every day on the way home from school I’d pass by the ruins of an ancient castle, where he made his final stand against the armies of Islam in 642 AD. The Battle of Nahavand was the bloodiest defeat in the history of our country. Most days when I got home I’d go straight to my room and read Shahnameh. The book opens in myth: our oldest stories, from before the written word. But the poets say our myths are even truer than our history. They emerge from the collective psyche. They hold our dreams. They hold our ideals. When Ferdowsi writes about our mythic heroes, he writes about all of us. And in Shahnameh there is no greater hero than Rostam. The Heart of Iran. A knight with the height of a cypress. And a voice to make, the hardened hearts of warriors quake. At one point in Shahnameh Iran is on the brink of defeat. Three enemy kings have joined their forces. Our armies are almost beaten. Rostam arrives at the battlefield on foot: no horse, no armor, carrying nothing but a bow and arrow. And with a single shot he slays the greatest champion of the other side. I wanted to be Rostam. My brother and I built a gym behind our garden. We took the heads off of shovels and made parallel bars. We made barbells out of clumps of dirt. We’d wrestle sixty times a day. And while we wrestled my brother’s friend would beat a drum and chant our favorite verses about Rostam: his defeat of the demon king, his battle with the dragon. There were no dragons in Nahavand, but there were ibex. They only lived at the highest elevations. And they were beautiful with their horns. I’d climb all night. I’d make my way by moonlight. The cliffs were covered in ice, a single slip could mean death. But I’d reach the summit by dawn, and watch the sun come up on herds of ibex grazing on the peaks.”

پدرم مرا «پرویز» نام نهاد - به نام یکی از پادشاهان ساسانی. داستان خسرو پرویز در بخش تاریخی شاهنامه میآید. او شاه بدی نبود ولی در کار فرمانروایی لغزشهایی بدفرجام داشت. پادشاهی او دوران طلایی موسیقی بود. نوهاش یزدگرد سوم پادشاه سالهای پایانی شاهنشاهی ساسانی بود. روزانه، در راه مدرسه به خانه، از نزدیک ویرانهی کاخی باستانی میگذشتم که جایگاه شکست یزدگرد سوم از سپاه اسلام در سال ۶۴۲ میلادی بود. نبرد نهاوند بدفرجامترین شکست تاریخ ماست. همینکه به خانه میرسیدم، بیدرنگ به اتاقم میرفتم و شاهنامه میخواندم. کتاب با اسطورهها آغاز میشود: کهنترین داستانهای ما، از دوران پیش از نوشتار. برخی میگویند که افسانههای ما از تاریخمان هم راستینترند. آنها از روان گروهیمان برخاستهاند. دربرگیرندهی آرزوها و آرمانهای ما هستند. هنگامی که فردوسی از پهلوانان افسانهای ایران میسراید، دربارهی همهی ما مینویسد. و در شاهنامه پهلوانی والاتر از رستم نیست. قلب تپندهی ایران. پهلوانی بالابلندتر و نیرومندتر از همه. به بالای او در جهان مرد نیست / به گیتی کس او را همآورد نیست. با صدایی که دلهای استوار جنگجویان را به لرزه میانداخت. در بخشی از شاهنامه، ایران در آستانهی شکست است. سپاه سه کشور به هم پیوستهاند. رستم پیاده به آوردگاه میرسد: بی اسب، بی جنگافزار، تنها با دو تیر و کمانش. اسب و سردار نیرومند سپاه دشمن را از پای در میآورد. میخواستم رستم باشم. من و برادرم زورخانهای پشت باغچهمان ساخته بودیم. دستهبیلها را جدا کرده و با دستهها میلههای موازی (پارالِل) برپا کردیم. هالتر را از دسته بیل و گِل رُس تهیه کردیم. ما هر روز تا شصت بار کُشتی میگرفتیم. هنگام کشتی، دوست برادرم طبل مینواخت و شعرهای موردعلاقهمان را دربارهی رستم میخواند: شکست دادن دیوان، نبرد او با اژدهای پیدا و پنهان. در نهاوند اژدهایی نبود، ولی کَل و بزهای کوهی بودند. شاخهایشان چه زیبا و شکوهمند بود. بر بلندترین قلهها میزیستند. تمام شب را از کوه بالا میرفتم. مسیرم را با روشنایی مهتاب مییافتم. گاه تختهسنگها از یخ پوشیده بودند، اندک لغزشی میتوانست مرگبار باشد. ولی پیش از سپیدهدم خود را به قله میرساندم، و به تماشای تابش آفتاب بر گلهی بزهای کوهی که سرگرم جست و خیز و چرا بودند، مینشستم

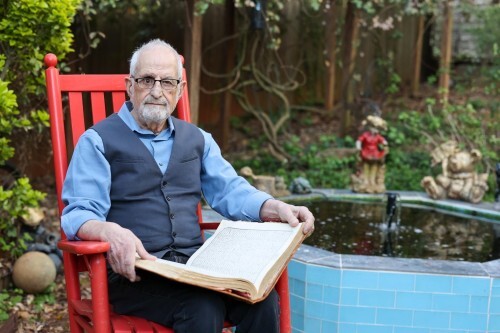

(3/54) “It’s been forty-three years since I’ve seen my home. All...

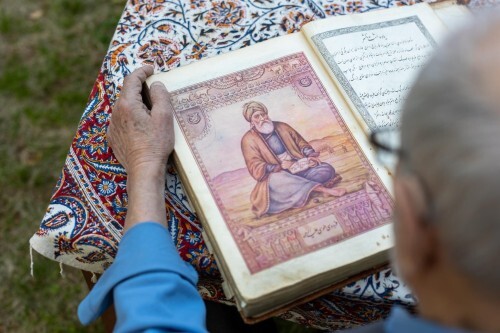

(3/54) “It’s been forty-three years since I’ve seen my home. All I have left is a jar of soil. It’s good soil. Nahavand is a city of gardens. A guidebook once called it ‘a piece of heaven, fallen to earth.’ The peaks are so high that they’re capped with snow. A spring gushes from the mountain, and flows into a river. It spreads through the valley like veins. We lived in the deepest part of the valley, the most fertile part. Our father owned thousands of acres of farmland. When we were children he gave us each a small plot of land to plant a garden. None of the other children had the discipline. They’d rather play games. But I planted my seeds in careful rows. I hauled water from a nearby well. I pulled every weed the moment it appeared. As the poets say: ‘If you cannot tend a garden, you cannot tend a country.’ My garden was the best; it was plain for all to see. The discipline came from my mother. She was very devout. She prayed five times a day. Never spoke a bad word, never told a lie. My father was a Muslim too, but he drank liquor and played cards. He’d wash his mouth with water before he prayed. The Koran was in his library. But so were the books of The Persian Mystics: the poets who spent one thousand years softening Islam, painting it with colors, making it Iranian. Back then it was a big deal to own even a single book, but my father had a deal with a local bookseller. Whenever a new book arrived in our province, it came straight to our house. I’ll never forget the morning I heard the knock on the door. It was the bookseller, and in his hands was a brand-new copy of Shahnameh. The Book of Kings. It’s one of the longest poems ever written: 50,000 verses. The entire story of our people. And it’s all the work of a single man: Abolqasem Ferdowsi. Shahnameh is a book of battles. It’s a book of kings and queens and dragons and demons. It’s a book of champions called to save Iran from the armies of darkness. Many of the stories I knew by heart. Everyone in Iran knew a few. But I’d never seen them all in one place before, and in a beautiful, leather-bound edition. The book never made it to my father’s library. I brought it straight to my room.”

چهلوسه سال از هنگامی که از میهنم دور افتادهام میگذرد. آنچه برای من باقی مانده، شیشهایست پر از خاک. خاک خوبیست. خاک نهاوند، خاک ایران. نهاوند شهر باغهاست. زمانی کتاب ایرانگردی را خواندم که آن را “تکهای از بهشت بر زمین افتاده” نامیده بود. بر قلههای بلندش برف همیشگی پیداست. چشمهای که از دل کوه میجوشد، رودی میشود. چون رگهای تن در سراسر دره پخش میشود. ما در ژرفترین بخش دره زندگی میکردیم. حاصلخیزترین بخش آن. پدرم از زمینداران بود. او در کودکی من، به هر یک از فرزندانش پاره زمینی در باغ خانه داد تا باغچهای درست کنیم. بچههای دیگر چندان علاقهای به این کار نداشتند. آنها بازی را بیشتر دوست داشتند. ولی من دانههایم را به هنگام با دقت میکاشتم. آب را از حوض یا چاه نزدیک میآوردم. گیاهان هرزه را بیدرنگ وجین میکردم. همانگونه که میگویند: «اگر نتوانید از باغچهتان نگهداری کنید، از میهنتان نیز نمیتوانید.» باغچهی من بهترین بود؛ زیباییاش بر همگان آشکار. این نظم را از مادرم آموخته بودم. مادرم بسیار پرهیزکار بود. روزی چند بار نماز میخواند، هرگز واژهی بدی بر زبان نمیراند، هیچگاه دروغ نمیگفت. پدرم نیز مسلمان بود، ولی در جوانی گاهی نوشابهی الکلی هم مینوشید و ورقبازی هم میکرد. پیش از نماز دهانش را آب میکشید. در کتابخانهاش قرآن و کتابهایی از عارفان ایرانی داشت. شاعرانی که در درازای هزار سال اسلام را نرم و ملایم کرده بودند، به آن رنگ و بو بخشیده بودند، ایرانی کرده بودند. در آن زمان که داشتن کتاب کار آسان و عادی نبود، پدرم با کتابفروش محلی قراردادی داشت. او هر بار کتاب جدیدی به دستش میرسید، باید یکراست نسخهای به خانهی ما بفرستد. هیچگاه آن بامدادی را که صدای کوبیدن در را شنیدم، فراموش نخواهم کرد. کتابفروش آمده بود و در دستانش کتاب شاهنامهی جدیدی بود. نامهی شاهان. یکی از بلندترین شعرهایی که تا کنون سروده شده است، بیش از پنجاه هزار بیت شعر. همهی داستانهای مردمانمان. همهی ایران در شعری یگانه. و همهشان سرودهی یک شاعر: ابوالقاسم فردوسی. شاهنامه کتاب نبردهاست. کتاب شاهان و شهبانوان، اژدهایان و اهریمنهاست. کتاب پهلوانانیست که ایران را در برابر نیروهای اهریمنی پاس میدارند. بیشتر داستانها را از بر بودم. هر ایرانی داستانی از شاهنامه میدانست. ولی من هیچگاه همهی داستانهای شاهنامه را یکجا در جلدی چرمی و زیبا ندیده بودم. آن کتاب هرگز به کتابخانهی پدرم راه نیافت. آن را یکراست به اتاقم بردم

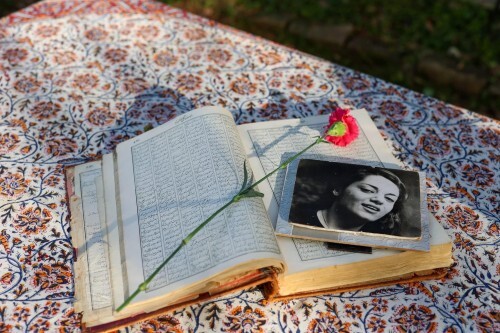

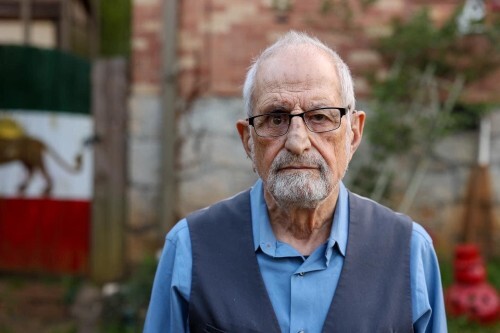

(2/54) “I couldn’t find it anywhere. Even on the streets of...

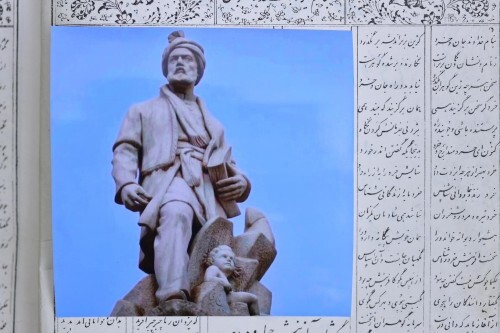

(2/54) “I couldn’t find it anywhere. Even on the streets of Tehran, it was nowhere to be seen. The Iran I knew was gone. Everywhere I turned it was nothing but black: black cloaks, black shrouds. The universities were closed, the libraries were closed. Our poets, our singers, our authors, our teachers: one-by-one they were silenced. Until Iran only survived inside our homes. I never planned to leave. I didn’t even have a passport. Twenty years earlier I’d sworn an oath to The Siren: every choice I made, I’d make for Iran. But The Siren was dead. They shredded his heart with bullets. And there was only one choice left: leave and live, or stay and die. It was an eight-hour drive to the Turkish border. Mitra came with me. We rode in silence the entire way. I’ve always wondered how things would have turned out differently if we’d been more aligned. She wanted our lives to be a love story. A surreal romantic journey. She wanted a life of togetherness, surrounded by beauty. For me life was meant to be lived in the pursuit of ideals: truth, justice, freedom. Even if that meant the ultimate sacrifice. We kissed goodbye in the border town of Salmas. In the main square stood a statue of Iran’s greatest poet: Abolqasem Ferdowsi. On that day it was still standing. Soon the regime would tear it down. I spent the night in the house of a powerful family who was known to oppose the regime. Their servants stood around the house with machine guns on their shoulders. Six months later they’d all be dead. On my final morning in Iran I woke with the sun. I knelt on the floor and prayed. The final journey was made on foot. It was six miles to the border, the road climbed through the mountains. It was a closed border; so the road was empty. Every step felt like death. I’ve never cried so many tears. Ferdowsi once wrote: ‘A man cannot escape what is written.’ I’ve always hated that quote. I hate the idea of destiny. There is always a role for us to play. There is always a choice to be made. But on that day it felt like destiny, a river flowing in one direction. And I was a leaf, floating on top. Away from where I wanted to go.”

آن را نمییافتم. حتا در خیابانهای تهران - در هیچ جای دیگر هم نبود. ایرانی که من میشناختم، رفته بود. به هر سو نگاه میکردم تنها سیاهی بود: عباهای سیاه، چادرهای سیاه. دانشگاهها را بسته بودند، کتابخانهها بسته بودند. شاعرانمان، هنرمندانمان، نویسندگانمان، آموزگارانمان - همه را یک به یک خاموش کرده بودند. ایران تنها درون خانههامان زندگی میکرد. من هرگز قصد رفتن نداشتم. من حتا گذرنامه هم نداشتم. بیش از بیست سال پیش در نیروی آژیر سوگند یاد کرده بودم: همهی اندیشه و توانم، برای ایران خواهد بود. ولی آژیر را کشته بودند. قلبی را که هر تپشش برای ایران بود با گلوله سوراخ کرده بودند. و تنها یک گزینه مانده بود: رفتن و زنده ماندن، یا ماندن و مردن. تا مرز ترکیه نزدیک به هشت ساعت رانندگی بود. میترا با من همراه شد. سراسر راه را در خاموشی گذراندیم. همواره کنجکاو بودهام که سرنوشت ما چگونه میشد اگر ما همآهنگتر میبودیم. او همواره میخواست که زندگیمان سفری رؤیایی و عاشقانه باشد. همراهی در زیبایی. ولی زندگی برای من مسئولیتی جدی بود. میبایستی آرمانخواهانه برای رسیدن به راستی، داد و آزادی زندگی کرد. در شهر سلماس با بوسهای همدیگر را بدرود گفتیم. در میدان اصلی شهر تندیسی از بزرگترین شاعر ایران بر پا بود: ابوالقاسم فردوسی، پیر پردیسی من. آن روز تندیس هنوز برپا بود. دیری نپایید که رژیم آن را ویران کرد. شب را در خانهی خانوادهای پرنفوذ که به مخالفت با رژیم شناخته میشد، سپری کردم. خدمتکاران آنها مسلسل بر دوش خانه را پاسبانی میکردند. شش ماه پس از آن دیدار بسیاری از آنها را نیز کشتند. در واپسین بامدادم در ایران با سپیدهدم بیدار شدم و نماز خواندم. واپسین بخش راه را پیاده رفتم. تا مرز دو فرسنگ راه بود. راه از میان کوهستان میگذشت. مرز بسته بود، گذرگاه هم تهی بود. هر گامی سخت بود و اشکم جاری. فردوسی چنین میگوید: بکوشیم و از کوشش ما چه سود / کز آغاز بود آن چه بایست بود. همواره از این گفته بیزار بودهام. از مفهوم سرنوشت بیزارم. هرگز نپذیرفتهام که سرنوشت از پیش نوشته شده باشد. همیشه گزینش و انتخابی هست. ولی آن روز سرنوشت من چون رودخانهای به یک سو روان بود. و من چون برگی شناور بر آب. دور از جایی که آهنگ رفتنم بود

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers