Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 8

August 9, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Martha Ronk

Martha Ronk

has had intersecting careers as aprofessor of Renaissance Literature and as a poet. She received her PhD fromYale University and has written numerous articles on Shakespeare’s plays,focusing on the interplay of the verbal and visual—a topic in her poetry aswell. Teaching classes on 17th century literature and on modern andcontemporary poetry revived her practice of writing poems leading to poetryworkshops at Bennington College. She has taught at Tufts University, ImmaculateHeart College, Otis College of Art and Design, and for most of her career atOccidental College in Los Angeles where for many years she taught creativewriting and coordinated the campus-wide Creative Writing Program.

Martha Ronk

has had intersecting careers as aprofessor of Renaissance Literature and as a poet. She received her PhD fromYale University and has written numerous articles on Shakespeare’s plays,focusing on the interplay of the verbal and visual—a topic in her poetry aswell. Teaching classes on 17th century literature and on modern andcontemporary poetry revived her practice of writing poems leading to poetryworkshops at Bennington College. She has taught at Tufts University, ImmaculateHeart College, Otis College of Art and Design, and for most of her career atOccidental College in Los Angeles where for many years she taught creativewriting and coordinated the campus-wide Creative Writing Program. Ronk has published eleven books of poetry, mostrecently with Omnidawn Press: CLAY bodies+ matter 2025, The Place One Is2022, Silences 2019, Ocular Proof 2016 on photographs, and Transfer of Qualities 2013 (the title aquotation from Henry James), long-listed for the National Book Award. Also in2022 Parlor Press issued A Myth ofAriadne. Her book, Partially Kept,published with Nightboat Books, is in dialogue with Sir Thomas Browne’s Garden of Cyrus; Vertigo, a National Poetry Series selection with Coffee House Presspays homage to W.G. Sebald, and why/whynot, UC Press, plays off to be or notto be and is indebted to the play, Hamlet. In alandscape of having to repeat, influenced by Freud’s essay on “ScreenMemory,” won the PEN USA best poetry book of 2005.

Often in dialogue with other authors, Ronk seesher work taking shape in the spaces between various forms, vocabularies, andgenres, each volume operating as a coherent whole rather than a series ofindividual poems. Besides the profoundinfluences of other authors, Ronk has also focused her poems on paintings,photographs, ceramics, and photograms, and many of her books include ekphrasticpoems. Her collection of short stories, GlassGrapes and other stories, utilizes a variety of obsessive, unreliablenarrators; and her book on food, Displeasuresof the Table—semi-autobiographical, satiric, appreciative of allcooks—recommends reading over eating.

She has received a NEA award, had residencies atMacDowell Colony and Djerassi. She received the Sterling Award for scholarlyexcellence at Occidental College. Ronk has had readings at numerous bookstoresand other venues, was a visiting writer at the University of Montana and atGeorge Mason University. She was an editor of poetry books published by LittoralPress, and has had work included in eight anthologies, most recently North American Women Poets of the 21stCentury, Wesleyan 2021.

1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

I wrote CLAYbodies+matter when I returned to the potter's wheel after a longacademic career at Occidental College. It is the practice of making pots on thewheel that is the change in my life. The Clay book is different since itfocuses on a specific practice, on the merging of hands and clay, on theemptiness inside a bowl, and on another form of practicing as writing poetry isa practice. I found myself working at both, revising in both arenas, doingresearch, and thinking about the ways in which they reflect one another. Clayis far messier. I so much enjoyed reading about Japanese practices, theirlong tradition in clay.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Itaught 16th and 17th century poetry, wrote a dissertation on Milton, taughtShakespeare. I love John Donne. I was always drawn to poetry even as a child. Iwrote one book of short fiction, Glass Grapes, because I wanted tocreate an obsessive narrator. I am not sure why this seemed to me to befiction, but it did. I also find that poetry, for me, has to wrestle more withmy interest in the visual. Although many poets don't like to use imagery,I do; I also like to write about photography and paintings: ekphrastic poems

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

It has depended onthe particular project. Some come quickly or in tandem with an experience.Right now I am writing poems that seem distinct from one another,, but it isearly days. A book usually takes 4 years and I mean for each project to be aunified book.

4 - Where does a poem usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I write drafts and individualpoems until I have a fairly firm sense of what "book" I am workingon; most of my books have been in dialogue with other authors: W.G. Sebalf,Henry James, Shakespeare's Hamlet, or specific places. I like having a partner,another to influence my narrow views.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

As I've gotten older I've been less andless interested and able to travel to give readings. I always enjoyed them, butrecently not so much.I always liked listening to the others I was reading with.I'm reading for Omnidawn on Zoom on July 13 with others published in the fall.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

It seems to me that manyrecent books concern gender, immigration, grief & war, and displacements ofvarious sorts. There are so many gifted young writers from other countries. Itis important for poetry to address these issues. I have written an unpublishedmanuscript on climate change; I will continue to write more about trees, birds,drought, and the environment. (A few poems to be published by The ColoradoReview.) As a past teacher, I find myself interested in my relationship to pastauthors. I am interested in fragility (bodies, clay pots, cultures), in poetrythat manages to include conceptual as well as linguistic work: that is, workthat asks for deep engagement and thinking. Work that I want to re-read.

7 – What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

See #6

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I wish Ihad an editor. I do have a poetry group that meets every few weeks and I getgood critical readings from the other poets. It helps enormously to have otherpoets respond to one's work before it goes public.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

"To be a goodpoet you have to have a good seat." That is, show up. Practice. Show upagain. Etc. It is also good to wait sometime to review one’s work.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

As an academic I wrote academic articles on Shakespeare'splays; I also got up early to write poetry before leaving to take my son to school and me to class. I likethat both require precision, research, reading, revision etc. I do lessacademic work now.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

I write something most days; Iprefer early morning. Other poets often provide inspiration. Also form itselfcan inspire: choosing to write prose poems or epigrams or dialogues or longpoems. Recently, I found myself inspired by memories of paintings ,memories of people I've lost track of or lost. I also like walking:sometimes, if I’m lucky, a word or stairway or song will fall out as I’mwalking: also there are all the things one sees: clouds, trash, a window ledge,leaf.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

13 - What was your last Hallowe'encostume?

none. I watched achild put on heavy make-up to be a cat.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, paintings and especially black and white photographs: I wrote an entirebook on photographs: “Ocular Proof.” My first husband was a photographer. I nowlook at pictures by great potters; I love the paintings of Giorgio Morandi. Ilike photographs of reflections in water, the idea of correspondences. New toCA I wrote a book about the desert (and HIV): “Desert Geometries,” and anothercalled “State of Mind.” The paintings of Ariadne by De Chirico influenced my bookon A Myth of Ariadne from ParlorPress: focused on the vulnerability of women, women’s bodies.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

W.G. Sebald. Edmund De Waal. mostrecently. Many poets. The Autobiography of Red. Shakespearemost especially because his plays were central to my teaching forso long. I was moved by the writer Claire Keegan’s new novels.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

I wish I hadtraveled more. Scenes fill up the brain: I went to Sicily most recently andkeep seeing temples in my mind’s eye. Andmosaics. And the view to Africa.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think that moving from the eastcoast to LA had a profound effect on me as I found it strange, “familiar/unfamiliar’ asI’ve written in The Place One Is.

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

I couldn’t seem to help it. I think Ineeded to say things I believed I couldn’t say in any other way.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

I liked the films on tv: Wolf Hall,The Fall. I listened on Audible to Little Dorrit and havecome to appreciate Dickens and his skewering of the wealthy as I didn't ingraduate school. I'll never tire of re-reading Hamlet.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm trying to write about "thespecious present" (William James) and time. Trying the operative word.Failing. Etc. Don't all beginnings feel like tripping and falling and feelingas awkward as possible? I keep asking “what is a moment?” How might I define it or live it or imaginethe ends of my own time? Reading his words on time stick with me, pushed me totry to find other ways of expressing the way amoment contains both past and future as well.

August 8, 2025

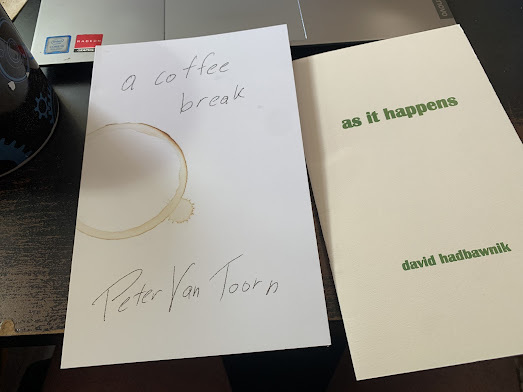

Ongoing notes: early August, 2025: Peter Van Toorn + david hadbawnik,

Hey!Are you following the above/ground press substack? Lots of new stuff overthere.

Hey!Are you following the above/ground press substack? Lots of new stuff overthere. Montreal QC: I was curious to see a new chapbook ofpoems, a coffee break (Montreal QC: Turret House, 2025), by the late Montreal poet Peter Van Toorn (1944-2021), especially given that his lastpublished work was the collection Mountain Tea: & Other Poems (Montreal QC: VehiculePress, 2004) [see my notes on such here], a collection originally published byMcClelland & Stewart in 1984 as Mountain Tea & Other Poems. Justprior to the publication of that 1984 title, Van Toorn had a stroke, and, as I’maware, didn’t publish any further new work through the remainder of his life. Movingthrough an author’s archive for the sake of publishable work is an interesting endeavour—I’vedone my own excavations through the work of Andrew Suknaski, for example, andkeep hoping that someone might wade through the archives of Artie Gold to seewhat might be buried there—working a fine line between original authorialintent, especially for an author as reticent as Van Toorn, and continued publicinterest (especially if the work is publishable). One can point to a recent posthumoustitle by the late Joan Didion (1934-2021), her Notes to John (2025), awork that one can’t entirely know (at least from this distance) if such wouldhave even been considered publishable (although if it sits in one’s literary archive,one can argue it is all fair game).

Not that the line inquestion lacks refinement in the sense of finesse—they are skillful enough—but theylack seriousness. And worst of all, these lines try to borrow power from theircontext, by their close association with the tradition of the sacred. So, theycome to be a beggar dressing up and putting on airs—in clothes borrowed withoutpermission from a rich cousin.

VanToorn’s work has long been known for a particular precision, as well as a deceptiveease, of a lyric fine-tuned across years, so this short eight-poem prosesequence is intriguing. There is an ease here, and a further openness to thelines assembled here, in comparison to the poems of Mountain Tea—one couldbounce a quarter off of those lines, certainly. This is a lovely, sleek thing,and it does make me curious as to whether or not there might be somethingfurther in that archive of his. What else might such boxes and file-foldershold?

Eden Prairie MN: From American poet david hadbawnik’s polispress comes his chapbook as it happens (2025), published as a sleekchapbook dedicated “for Tina and Elliott,” but made up of a single, extendedpoem “for alice notley,” published as an elegy and homage for the legendary American poet who died earlier this year (1945-2025). “she learned to speak with thedead,” the sequence opens, “whose voices go in a continuous / dark loop acurrent / between this and that / white noise / perhaps heard through / ameasure of trees / or birdsong in spring / all she or you or anyone had to do /was stop breathing and the voices / come through no language [.]” There is animmediacy, even a rawness, to hadbawnik’s ongoingness through this sequence,one that suggests a fresh project potentially far larger than the current selection.Might there be more?

Ride into big sky. The lightgoing on

and on. Above trees abovebuildings is

that the sea is that traceof shipwreck or

morning sun? When we stepdown from the car

into splendor of green recedingwhen

we mouth the words thatjangle open doors

will our breath describea line that seems like

darkness falling? My armthrust around you

your slim shoulderlaughter of beard trails and

in California is it always?This way

and that sand wigglingwet in between

like a dog’s nose or thesmell of found money

or a glimpse of skin as askirt shifts and

legs uncross or a newbeginning

August 7, 2025

The Factory Reading Series, August 21, 2025: Currin, Heinis, JAAWORD + Pirie,

The Factory Reading Series Presents:

The Factory Reading Series Presents:readings by:

Jen Currin (Vancouver)lovingly hosted by rob mclennan

Shery Alexander Heinis (Ottawa)

Jamaal Amir Akbari/JAAWORD (Ottawa)

Pearl Pirie (QC)

Thursday, August 21, 2025

Doors 7pm / Reading 7:30pm

Avant-Garde Bar, 135 Besserer Street, Ottawa

Jen Currin has published two collections of stories, Disembark (House of Anansi, 2024) and Hider/Seeker (Anvil Press, 2018), which was a finalist for a ReLit Award and was named a 2018 Globe and Mail Best Book. They have also published five collections of poetry, including Trinity Street (House of Anansi, 2023) and The Inquisition Yours (Coach House, 2010), which won the 2011 Audre Lorde Award for Lesbian Poetry and was a finalist for a LAMBDA and two other awards. Currin lives on the ancestral and unceded territories of the Halkomelem-speaking peoples, including the Qayqayt, Musqueam, Kwikwetlem, and Kwantlen Nations, in New Westminster, BC. They teach creative writing and English at Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Shery Alexander Heinis [pictured] is a St. Lucia born poet, writer, and former diplomat. She is the co-founder and Artistic Director of In Our Tongues Reading and Art Series, an Ottawa-based arts non-profit that showcases, nurtures, and advances Black, Indigenous, and racialized artists from the National Capital Region and across Canada. She is the author of A Greater Whole, as well as her debut poetry collection, Splinter (self-published). Her work has appeared in ARC Poetry Magazine, The League of Canadian Poets’ Black History Month Chapbook, These Lands, Bywords, In\Words and more. She has been a feature reader at the Ottawa International Writers Festival, VERSeFest Ottawa and The Tree Reading Series among others. Shery is featured in BREATH, a multimedia immersive art installation and the documentary film FOUR WOMEN on Bell Fibe TV1 and CBC Gem.

Jamaal Amir Akbari or JAAWORD is an award winning poet, songwriter, recording, screen and performance artist, arts educator and creative entrepreneur. He is Ottawa’s 2017-2019 Poet Laureate Emeritus, and his career in arts education earned him 2016's Ontario Arts Educator Award.

He has brought his work to audiences nationally and abroad, and served as Carleton University’s Artist in Residence for the 2019-2020 school year. He also founded the Origin Arts & Community Centre in 2015, a performance arts hub on the edge of Ottawa’s Hintonburg neighbourhood that provides an event space for performing artists to share their passion.

His topics range from emotional maturity to black heritage, from parenting to the human condition. He resides in rural Marathon Village, ON, with his wife and 8 children, using the national capital region as his launch pad to teach, mentor and advocate for the arts.

Pearl Pirie lives quietly & slowly in rural Quebec and Ottawa. Her latest is we astronauts from Pinhole Poetry. www.pearlpirie.com

August 6, 2025

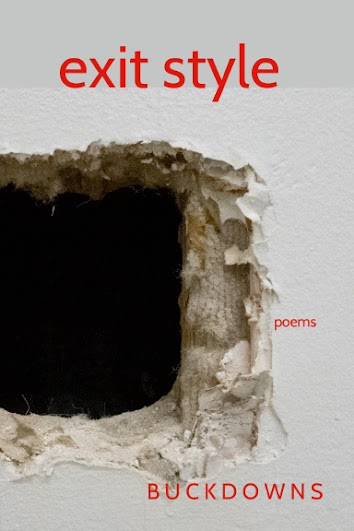

Buck Downs, exit style

nothing left to refund

did you ever try

to fix yourself

and find out

that doesn’t work

a purchase that looks

like you found it

it shakes my whole body

like a chuck full of wood

Thelatest from Washington DC poet [and above/ground press author, I should add] Buck Downs is the self-published

exit style

(2025), following

NICE NOSE

(2023) [see my review of such here], the chapbook-length

GREEDY MAN:selected poems

(Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks, 2023) [see my review of such here],

OPEN CONTAINER

(Washington DC: privatelyprinted, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Unintended Empire: 1989-2012

(Baltimore MD: Furniture Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], amongmultiple other titles. Composed as seven cluster-sections of short poems—“shyboy,” “illucidations,” “little wages,” “’patacoustics,” ““For Bleachers”,” “thisis not to say” and “exit style”—Downs’ has long been engaged with observationalthinking, but one that provides a sense of continued, ongoing andinterconnected meandering. “your dream should have / an exit plan,” he offersin the poem “sleepervescent,” “clinging / to the rock / of emptiness // returnto dust / no other places / can I go / but where I come to [.]” His poems arecomposed as self-contained sharp moments, of wisdoms and self-aware questionsand clarifications, that accumulate, even build, in a finely-tuned lyric acrossa perpetual engagement with the surrounding world and life’s possibilities. “I spreadout / in my body / til I could feel / my presence / in every cell,” the poem “apiece in a pinch” offers, “the pressure / of cell on cell / compounding // it’sa find-me puzzle / I can’t quit matching [.]”

Thelatest from Washington DC poet [and above/ground press author, I should add] Buck Downs is the self-published

exit style

(2025), following

NICE NOSE

(2023) [see my review of such here], the chapbook-length

GREEDY MAN:selected poems

(Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks, 2023) [see my review of such here],

OPEN CONTAINER

(Washington DC: privatelyprinted, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Unintended Empire: 1989-2012

(Baltimore MD: Furniture Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], amongmultiple other titles. Composed as seven cluster-sections of short poems—“shyboy,” “illucidations,” “little wages,” “’patacoustics,” ““For Bleachers”,” “thisis not to say” and “exit style”—Downs’ has long been engaged with observationalthinking, but one that provides a sense of continued, ongoing andinterconnected meandering. “your dream should have / an exit plan,” he offersin the poem “sleepervescent,” “clinging / to the rock / of emptiness // returnto dust / no other places / can I go / but where I come to [.]” His poems arecomposed as self-contained sharp moments, of wisdoms and self-aware questionsand clarifications, that accumulate, even build, in a finely-tuned lyric acrossa perpetual engagement with the surrounding world and life’s possibilities. “I spreadout / in my body / til I could feel / my presence / in every cell,” the poem “apiece in a pinch” offers, “the pressure / of cell on cell / compounding // it’sa find-me puzzle / I can’t quit matching [.]”Thebrevity of Downs’ poems can be deceptive, almost obscuring, in plain sight, justhow smart these poems really are, and have become over the years he’s beenworking, and almost set themselves in that space between knowing and unknowing,perpetually between dreaming and conscious thinking. There are echoes here ofthe observational language first-person movements of such as American poet William Carlos Williams in Downs’ short, clipped lines, or even certain elements of thework of Vancouver poet George Bowering and American poet Robert Creeley, oreven the ghazal of the late east coast poet John Thompson, as Downs offers hisown sequences of meditative response-moments in a particular, ongoing cadence,each poem set as its own kind of thought-sentence. Or the poem “this is not tosay,” that writes:

I know something

I thought I knew

before and how

like knowing

that the clock

is wrong

but still you

can’t tell the time –

there was dope left

for safe keeping

in a place where nobody

would think to look,

ever – and later found

by someone

who wasn’t even

trying to find it –

August 5, 2025

Spotlight series #112 : Mandy Sandhu

The one hundred and thirteenth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring

Oakville, Ontario-based poet and above/ground press author Mandy Sandhu.

The one hundred and thirteenth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring

Oakville, Ontario-based poet and above/ground press author Mandy Sandhu.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau, Indiana poet Nate Logan, Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn, North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson, award-winning poet Ellen Chang-Richardson, Montreal-based poet, professor and scholar of feminist poetics, Jessi MacEachern, Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell, San Francisco poet Micah Ballard, Montreal poet Misha Solomon, Ottawa writer and editor Mahaila Smith, American poet and asemic artist Terri Witek, Ottawa-based freelance editor and writer Margo LaPierre and Ottawa poet Helen Robertson.

The whole series can be found online here .

August 4, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with fahima ife

fahima ife

is anAmerican poet, essayist, and editor. She writes about radical intimacy, beauty,and sensuality as it pertains to nature and metaphysics. She is author of thepoetry book, Septet for the Luminous Ones (Wesleyan University Press,2024), the hybrid book, Maroon Choreography (Duke University Press,2021), the chapbook,

abalone

(Albion Books, 2023), and other poems andessays appearing in The Kenyon Review, the Brooklyn Rail, Obsidian:Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, The Indiana Review, Air/Light,ASAP/J, liquid blackness, Interim, Poetry Daily, andmore. She has performed at the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics, thePoetry Foundation, the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton, the Museum ofthe African Diaspora, and other places. Her work has been written about in the NewYork Times, the Poetry Foundation, Fugue Journal, the PoetrySociety, Brooklyn Poets, Lateral, and other places. She isassociate professor of Black Aesthetics & Poetics in the department ofCritical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of California Santa Cruz. Sheteaches creative classes on African diasporic music and performance,experimental poetry and poetics, Black Studies, Black Lesbian practices, andmore. With poet Ian U Lockaby she co-directs, co-creates, co-curates, andco-edits a chapbook series for their poetry micropress,

LUCIUS

. Shemakes her home on the central California coast where she practices a yogalifestyle grounded in daily rituals of love, joy, and peace. She is at work ontwo books which explore sacred feminine aging in tantric union with mature masculinity:a poetry book called, Cosmic Libido, and an essay on experimentalpoetics called, Love Scene, or dancehall on the radio.

fahima ife

is anAmerican poet, essayist, and editor. She writes about radical intimacy, beauty,and sensuality as it pertains to nature and metaphysics. She is author of thepoetry book, Septet for the Luminous Ones (Wesleyan University Press,2024), the hybrid book, Maroon Choreography (Duke University Press,2021), the chapbook,

abalone

(Albion Books, 2023), and other poems andessays appearing in The Kenyon Review, the Brooklyn Rail, Obsidian:Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, The Indiana Review, Air/Light,ASAP/J, liquid blackness, Interim, Poetry Daily, andmore. She has performed at the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics, thePoetry Foundation, the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton, the Museum ofthe African Diaspora, and other places. Her work has been written about in the NewYork Times, the Poetry Foundation, Fugue Journal, the PoetrySociety, Brooklyn Poets, Lateral, and other places. She isassociate professor of Black Aesthetics & Poetics in the department ofCritical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of California Santa Cruz. Sheteaches creative classes on African diasporic music and performance,experimental poetry and poetics, Black Studies, Black Lesbian practices, andmore. With poet Ian U Lockaby she co-directs, co-creates, co-curates, andco-edits a chapbook series for their poetry micropress,

LUCIUS

. Shemakes her home on the central California coast where she practices a yogalifestyle grounded in daily rituals of love, joy, and peace. She is at work ontwo books which explore sacred feminine aging in tantric union with mature masculinity:a poetry book called, Cosmic Libido, and an essay on experimentalpoetics called, Love Scene, or dancehall on the radio. 1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

Wow, great question. Myfirst book, Maroon Choreography, changed my life in profound immediateways. Stephanie Burt wrote a sweet review in the New York Times Book Review,which brought significant attention and light to my previously subterraneanexistence. I moved into community with so many other great souls, became knownin a way. Financially, my entire life changed for the better. I got a new joband tenure at the University of California Santa Cruz, was able to move fromNew Orleans back to my home state of California, to live by the ocean which issomething I always wanted. Maroon continues to create such powerfulopportunities to think deeply with many people I would otherwise not have achance to study with. I receive messages all the time from people who expressgratitude for that book. It's an ongoing phenomenon. My second book, Septetfor the Luminous Ones, has brought me into deeper community withcontemporary poets, which is something I did not know how much I needed until Ibegan to experience the unmatched joy of being able to pick up my phone andtype or speak a message to some other brilliant living poet who lives hundredsof miles away from me, to momentarily feel less alone in the general vastnessof being a poet in this world-simulation that still—on a mass scale—has no ideawhat we are, or what we are for.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I first came to poetry asa child. I began dancing when I was 3. I began reading and writing when I was4. Growing up, my family was very mystical, musical, spiritual, so at home itwas easy for me to "be" a poet, meaning I could explore and deepen myneurospicy sensibilities—I was a sleepwalker as a child, I had incredibly vividdreams that I could recall with great detail, I began astral traveling, I wasdeeply connected with spirit realms, could commune with spirits, otherentities, was incredibly sensitive (secretive), had a lot of imaginary friends,would spend hours preoccupied within the invisible realms in our backyard, oncamping trips, or just drifting around aimlessly in my own imagination, I couldeasily imitate the sounds of other people's voices, could sing lyrics to songseven if I had never heard the song before and was singing it for the firsttime, had an episodic memory that felt almost epic, for the most part all ofthis was fine in the context of my family. I went to a public, creative artsschool, I was in a magnet program, so I was involved with various creativepractices as a child. In first grade, I guess around age 7, I started recitingpoetry by Harlem Renaissance poets, Gwendolyn Brooks, Langston Hughes, other greatslike Emily Dickinson, because my teacher, mom, and assistant teacher—threeBlack and Brown women who were all about Black history and Black poetry—co-createda daily practice that they collectively reinforced at home, in the classroom,at recess on the playground, and in the world. My mom would have me read poetryaloud to her most nights when I was young, she taught me how to type on hertypewriter at the kitchen table, she also taught me how to sew, so poetrybecame something embedded within my daily practice of reading, studying,playing, moving, making, breathing, speaking, being. Just this very naturalthing. I finally began writing poems around age 14, which makes sense to me nowbecause that was around the time when I told my mom I wanted to beginpracticing witchcraft and I was no longer interested in going to our ChristianScience church. Fortunately for me, she listened and supported my decision.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes me a very longtime to start anything. Writing is no different. Sometimes I get a very clearflash of an entire project—generally a book—I see, feel, experience it as afinished product, understand exactly what it is, experience a heightenedecstasy that's unlike anything, then soon after I lose the thread and can'tseem to figure out how to get from A to B. But if I feel that flash and committo a project then I'm determined to see the thing through, no matter how longit takes or where it takes me. My first book was written in time constraints,it was my tenure project, so there was external pressure which I did not enjoy.Writing Maroon was such a painful process for my physical body, becauseI was so focused on the work itself I could not properly attend to all thesignals coming from my body, or actually release years of the accumulated painthat I was working through in the process of shaping Maroon whose formchanged dramatically from initial drafts to the published book. I was superanxious the whole time. I really had to learn how to get out of the way, tostop trying to control it, to let the book become itself and not what I wantedit to be. Septet came in a delicious flash. Suddenly, after Maroon,I was receiving invitations from poets to submit new work. I was shocked tolearn I actually had more work, a lot of it! Rae Armantrout sent me a letterasking if she could put me in touch with her editor (now our editor) SuzannaTamminen at Wesleyan. After talking with Suzanna, I ended up writing Septetin nine months, which was entirely unexpected, a beautiful surprise! A doulafriend, Laurel Gourrier, told me it was a pregnancy and to treat it as such.I've never been pregnant with a human fetus, but I really loved working in agestational way, some of those final poems look the same as they first arrived,many of them went through several revisions before the final shape. Now,because I no longer have any time constraints, I have this incredible freedomto truly listen to a project, to allow it to come in its own time, to readjustenergetically to receive the work, receiving poems is a serious energeticcommitment (it's not often easy on the body), I'm much better at listening tomy body, pausing, properly caring for myself, releasing, moving stagnantenergy, and understanding how certain things I'm working through in the poetryis connected to actual trauma I've experienced in my human life, and the deepancestral work I'm healing at the cellular levels through my mother,grandmother, and all our mother's mitochondrial DNA. Working this way feelssuper natural, healing, sacred. I'm currently writing three books, differentgenres, all at once, have never done this before, it's ongoing. The firstsensation of these three new books emerged while I was wrapping up Septet,and by post-production I was committed to bringing these new books into theworld, began making notes on what I thought they might be. They change so muchas time passes. Lovingly, I refer to them as my triplets. It's such a slow,intentional, co-creative process. Only a little comes, or sometimes these hugefloods, followed by long periods of nothing. I spend a lot of time reading inthe nothing.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I'm generally working on abook from the very beginning. The poem, or really the book, arrives with aline, a sound, a sentence, a fragrance, laughter, a texture, an image, somethingsensual. In late spring 2021, I was sitting in a little casita in a rural townin New Mexico outside of Santa Fe when the line "petrichor / a waft justnow" floated in with the breeze, and the scent of coming rain. I heard theline in the wind, could feel it in the scent, wrote it down, it was thebeginning of Septet long before I began writing it. The actual lineappears in the poem "acid west" which emerges pretty far into theactual book, I was thinking partially with my friend Joshua Wheeler's AcidWest, after spending a lot of time with his book on the beach, probablythinking about the constant interplay of beach and desert. Poems are suchintimate spaces for me. They often begin on the precipice of great love,essentially for myself, and personal things I am exploring with friends andlovers.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I love reading poems. Iwant to read more public poems. I go through shadow and light periods.Sometimes I just need to be unperceived, in the dark, left alone. Other times Ilike to be very intensely in the light, just everywhere as much as possible. I'mcoming into a bright moment. I live in a small coastal town in California,which is not at all like a city, it has a much sleepier, subdued, sensualitythat I truly adore. Like no one is rushing, no one is really trying to impressanyone, people are just grateful to be in a shared creative spirit, it feelslike a great place to start talking into some microphones. The pace is exactlymy pace. I've been slowly making plans to do public readings here in SantaCruz, where the poetry scene is microscopic but intimate. I want to get up tothe Bay Area and start hanging with those poets too.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

These things have shifteddramatically for me post-tenure. Before my first book, I was basically tryingto hone a language to discuss what I care about, what I think about, what Istudy. I seem to be very obsessed with intimacy, sensuality, and beauty, theway we (as a species) can experience these heightened existential states ofbeing while still grappling with the horrors of systemic racial capitalism. That'sthe very broad thing. More specifically, at this point in my life, as a42-year-old Black woman, I am preoccupied with graceful aging, with renewing myrelationship with my uterus and hormones, with being a lunar creature, withdeepening my Tantra, with spirituality, with love and loving. It's so rare toencounter mainstream positive literary portrayals of Black women who are trulyinhabiting their power, who are loving fully and deeply, or the only spaceswhere I witness such delight is in the works and practices of Black Lesbians.Politically, in my writing and in my life, there is a very strong Black Lesbianethos, that is my main concern now. And I mean "Black Lesbian ethos"in that Cathy Cohen ("Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens") sensewhere a Black Lesbian politic is less about sex and who is sleeping with whom, andmore about intentional relating and caring for each other. I don't know exactlywhat other people's current questions are, but I am asking questions about howI can be more loving with myself and others in a time of continuous violence,precarity, scarcity, isolation, and fear.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

The writer is soessential. I think people forget this, or do not realize that the objectivereality we inhabit is a narrative, something written, something reinforced.Everyone is talking about Artificial Intelligence (AI), everywhere I turn, somuch anxiety around that, and whatever current trend in the media. Everythingis written. People speak things that are written. For better or for worse. Eachwriter has a different role. My role as writer is to spread love, to try andplay my part in shifting the vibrational frequency of this planet fromfear-based to love-based frequencies. It's easier, I think, to do this withmusic. The next closest thing is poetry. As a Black woman, I've experiencedsome terribly painful shit in this life, so much core trauma, inherited legacypain, but I work hard to transmute that pain into something beautiful. I'm sodisciplined in my craft, practice, to raise the lyric to a more consciouslevel, even if it doesn't come off that way to a reader, I know what type ofenergy I channel into my work. It's all Love. I think the role of the writer,on some levels, is to become exquisitely devoted curators of our craft —whatever forms we're working through and contributing to — to make a point ofcontextualizing our work in the "traditions" and groupings (etcetera) that inform and shape our work. I read so much. Poetry. Philosophy.Fiction (both great and bullshit). Essays. I read much, much, more than I write.My practice as a writer mostly involves a lot of deep study and also communionand conversations with the friends who help keep my ideas in motion. I thinkour role is super communal. I learn so much more about my role by being incommunity with friends, both practicing and non-practicing artists,experiencing moments of life together, having conversations about what we doand don't do. There's sometimes a tendency for people to distinguish practiceas some sort of rudimentary form that one must relinquish after a particularstage of development, at which point one presumably becomes adept, orproficient enough to no longer need to practice. Writing doesn't work like thatfor me. Even though lately much of what I think of as my "best"writing arrives quite rapidly, in order to receive these glimmers, I mustpractice to keep my instrument (my bodyaura) functioning at its optimal andready to receive when it's time. The whole process is incredibly feminine. Isort of work like an improvisational experimental jazz artist, those harpistsand horn players of the 1960s and 1970s, it only seemed as if they were jammingfree, but they could only do so because they spent so much of their time indeep continuous study, practice, and play. I'm grateful I have the privilege tolive how I live. That I get to immerse myself fully in the creative process tothe point where I get to live inside my works-in-process. For folks who stillhave to deal with a 9-5 job, or who are struggling with securing basic needs,it seems the role is to remain true to their struggle, to express what needs tobe expressed, to honor the tiny snatches of time when there is a moment tocontinue practicing, to continue shaping whatever poem, story, or missive thatis their pleasure (and perhaps purpose) and to share it with the world.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love the process ofworking with an editor. It's essential. I'm very independent, but receptive. Idon't like being told what to do. That's a huge turn off. I love when an editortrusts me, when they step back, when they (perhaps) perceive some glitch orsticky part in the work, but they let me figure it out on my own. I like faith.A lot of space. And figuring shit out on my own.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

June Jordan said"poems are house work" and I think that's the best advice I've everheard because it explodes into meaning and is resonant with how I live in myphysical home and physical body, what I do in these spaces, whom I invite in tothese places, the work I do.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as theappeal?

It appears seamless, but it'shard as hell. I use entirely different sensibilities when writing an essayversus receiving and shaping poetry. I'm doing this now in the three books I'mwriting. One is poetry, the other essay, the other fiction. I think the appealfor poets to move between poetry and essays is about being known. It's essentialfor poets to place our work in the context of other poetry, throughout time andspace, and to talk about the continuity, the expansions, whatever else ishappening, through essays. We are the only ones who can do this. We cannot relyon (non-poet) literary critics or analysts, to define what is taking placewithin our poetry. Plus, the labor of writing essays helps keep the traditionof poetry alive for future generations of readers and I am so committed to thisparticular part of the practice. And for me, it's totally practice. I practiceeach day and night. Mastery is a myth peddled by racial capitalism.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I'm incredibly domestic. Beingintentional with how I make home is necessary to my practice. At home, I live avery simple, ritualistic life and poetry is deeply embedded within this. Idon't like routine because it's too rigid for my lifestyle, but each day I tendto do the same things with slight variation. I move intentionally (either hike,yoga, dance, sometimes run), I breathe intentionally (in meditation), I preparenearly all of my meals, I fast sometimes, I drink a lot of water, I have ajournal I write in daily or many days a week, I eat in a seasonal Ayurvedic wayto maintain balance, I spend time on the ground outside (in the sun, in thegrey), I listen to the birds, I talk with people I know and strangers too, Iwork with plant medicines (cannabis and other herbs), sometimes I work withmagic mushrooms, I feel things very deeply, I make love to myself, I payattention to how my energy shifts throughout my menstrual cycle, I show up inthe ways I can in my communities, I read something, read a lot of thingsactually, I share the house with visitors I love, I remain in flow. Theuniversity where I teach is on a quarter system, I do not teach every quarter.If I'm in a teaching quarter, my rituals expand to allow more space to dealwith more humans than is typically the case for me, but I still dedicate timeto my creative practice. Days of the week have spiritual significance. I followthe astrological movements of the planets, the phases of the moon, I am alwaysmoving in accordance with the great invisible threads that hold us alltogether. Every day I recommit to life. Every day I practice deep gratitude forthe overall abundance in my life. When I am not in a teaching quarter, I ammuch more disciplined in my daily rituals, there's a precision, a tightness, aminimalism I cannot even articulate, but it's palpable. When I'm not teaching, becauseI live alone and do not have any children, I move into the delicious phase inmy year where I feel as if I am living in a continuous artist residency onlybroken by going out dancing with local friends which is totally part of mywriting practice.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I remember hearing thesinger Erykah Badu say in an interview once that there's no such thing as acreative block, that when we arrive at an impasse it's actually just a momentof heightened receptivity, we enter an intensive downloading or uploading partof the process. This might be another exceptional piece of advice, it changedhow I think about creating. Sometimes it feels frustrating when the writingstalls because I love creating, but I understand it's necessary to the process,to life. Everything goes through cycles. Nothing is in full bloom all yearlong. Whenever I experience these pauses, I don't even think about it anymore,I just surrender to the experience, feel things very deeply, pick it back upwhen it's time for me to re-enter the great stream. It might sound terrible,but when the creative process slows down, I often turn to my lovers and friendsand family who I had been unconsciously ignoring while I was busy at work. Ialso return to nature, take longer, slower walks, immerse myself with theearth, go deeper into meditation, sleep longer, sometimes hop around in variousbooks or sometimes binge watch a great television series. I'm not so muchsearching for inspiration in these moments, I feel as if I'm reacclimating tothe material plane, the whole thing is super grounding. I also tend to writevery long letters to friends, to poets, to other people during lulls.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

My home often smells like jasmine,sandalwood, frankincense, ganja, cedar, copal, cumin, cinnamon, coffee, rose,olive oil, lavender. These scents remind me of home.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, nature. I live veryclose to the ocean, it's such a delight to exist in the continuous sensation ofcoastal life, and the lifeforms that are here, various birds, flora and fauna,everything is so fertile, lively, synergistic. The way the weather fluctuateson a coast is so different from where I grew up in a desert valley in SouthernCalifornia and the landlocked experiences I had living outside the state inGeorgia, Wisconsin, and Louisiana. On the coast, there's a constant marinelayer, at dawn at dusk, interspersed by bright sun, it changes rapidly, themovement is a rhythm I'm still learning and honing in my craft. For the pastcouple years, one of the greatest influences on my work is the soundscapecreated by my friend and local dancehall DJ Selecta 7 (aka Osha B) who hosts aweekly radio show on KZSC 88.1fm and streamed online called "Reggae LoveRadio" on Saturday nights, and his monthly global bass music dance partiescalled "Outernational" here in Santa Cruz. Both surreal music spacesare great companions for all three of the books I'm currently preparing.Because Osha is super technical and precise, his shows/parties are so carefullycurated they feel like poems, or a kind of poetics that is at the exactfrequency in which I create, so his curatorial work within his scene is superinfluential.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Everything by Nathaniel Mackey, Renee Gladman, Ed Roberson, akilah oliver, Alice Notley, is importantto my work. Various books on Tantra. Also, I can't stop reading JasmineGibson's A Beauty Has Come. Otherwise, lately I've been reading fictionseries in English translation. Yoko Tawada's Scattered All Over the Earth,and Suggested in the Stars (look forward to the final book in theseries, Archipelago of the Sun) translated by Margaret Mitsutani. I alsolove Solvej Balle's On the Calculation of Volume (books one and two of aseven book series, translated by Barbara J. Haveland), which is unlike anythingI've ever read. I like stories that are mundane, minimalist, serial, composedthrough the simplicity of looping a certain sequence of events over and overwith slight variation, which happens in both Tawada and Balle's work. I've alsobeen reading a lot of Clarice Lispector's work alongside work by Hélène Cixous.I've been reading More Than Two (the original and the second edition) onhealthy polyamory, because I've been polyamorous for 20 years but just barelyreading these books because I'm writing about polyamory in a way that's stillvery fresh and exciting to me, so these books are helpful. I just got DebbieUrbanski's short stories, Portalmania.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

Grow food. Go to Morocco,Spain, Thailand, Bahia, Patagonia. Make quilts. Grow roses.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Hmm. I'd probably workwith textiles, make quilts, work on looms to make natural fiber blankets andclothing. Actually, I'd live on a farm with my partner and other people welove, some bold new age commune where we all have our own yurts, we'd all makea point of loving ourselves and each other, plus we would live with sheep whowe would carefully shear each season, lots of other animals. It would be a lotof work, a huge commitment, the whole thing would be rootsy, artsy, herbalist,based in trade, biodynamic, with plenty of time for shared walks, meals,intimate conversations. We'd host wellness retreats for people who live incities and want to reconnect with the earth. This is the dream! Fuck, I'm socottagecore. Maybe we could start some new great cult. Haha! Oh, or afilmmaker!

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

My frequency did this tome.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

No idea.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

A poetry book called, CosmicLibido. An essay book called, Love Scene, or dancehall on the radio.A fiction book whose name cannot yet be revealed to the public. And,co-directing, co-creating, co-curating, and co-editing a juicy new poetrymicropress, LUCIUS, with my friend Ian U Lockaby. We're preparing topublish our very first chapbook this summer—Nathaniel Mackey's very beautiful SoWoke We Saw Thru Stone, which continues his double long song, ongoingstill!

August 3, 2025

new from above/ground press: Downs, Kelly, Souffrant, Hausner, Gray, Vitkauskas, Chang-Richardson, Sandhu, Brenza, Berlatsky, Touch the Donkey #46 + Verse on the Banks / Poèmes sur le rivage,

Buck Downs, B U R N T O R A N G E $6 ; J-T Kelly, More of How to Read the Bible $6 ; Leah Souffrant, BIBLIOMANCY $6 ; Beatriz Hausner, The Oh Oh $6 ; Steph Gray, Never Saw it Coming: prose poems $6 ; Lina Ramona Vitkauskas, The Deaf Forest of Cosmic Scaffolding $6 ; Ellen Chang-Richardson, The Moleskin Coat $6 ; Mandy Sandhu, THE TEMPORARY SPACE OF A PLACENTA $6 ; Andrew Brenza, Sigil Series $6 ; Noah Berlatsky, Spamtoum $6 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #46, with new poems by Kirstin Allio, Kemeny Babineau, Joseph Donato, Beatriz Hausner, Matthew Walsh, Nicole Markotić, Lisa Pasold, Lina Ramona Vitkauskas and Emily Izsak $6 ; Verse on the Banks / Poèmes sur le rivage, eds./dir. Véronique Sylvain and/et David O’Meara including new poems in English (alongside French translation) and new poems in French (alongside English translation) by: Manahil Bandukwala, Julie Huard, Amanda Earl, Myriam Legault-Beauregard, David Groulx, Michèle Matteau, Monty Reid, Clémence Roy-Darisse; translations by/traductions de Myriam Legault-Beauregard $6

Buck Downs, B U R N T O R A N G E $6 ; J-T Kelly, More of How to Read the Bible $6 ; Leah Souffrant, BIBLIOMANCY $6 ; Beatriz Hausner, The Oh Oh $6 ; Steph Gray, Never Saw it Coming: prose poems $6 ; Lina Ramona Vitkauskas, The Deaf Forest of Cosmic Scaffolding $6 ; Ellen Chang-Richardson, The Moleskin Coat $6 ; Mandy Sandhu, THE TEMPORARY SPACE OF A PLACENTA $6 ; Andrew Brenza, Sigil Series $6 ; Noah Berlatsky, Spamtoum $6 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #46, with new poems by Kirstin Allio, Kemeny Babineau, Joseph Donato, Beatriz Hausner, Matthew Walsh, Nicole Markotić, Lisa Pasold, Lina Ramona Vitkauskas and Emily Izsak $6 ; Verse on the Banks / Poèmes sur le rivage, eds./dir. Véronique Sylvain and/et David O’Meara including new poems in English (alongside French translation) and new poems in French (alongside English translation) by: Manahil Bandukwala, Julie Huard, Amanda Earl, Myriam Legault-Beauregard, David Groulx, Michèle Matteau, Monty Reid, Clémence Roy-Darisse; translations by/traductions de Myriam Legault-Beauregard $6and: “poem” broadside #355 : TWO POEMS: “she left under a cloud” by Christine McNair and “010 : I can lift ten thousand pounds” by rob mclennan

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

June-July 2025

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

AND DON'T FORGET THAT SANDHU, CHANG-RICHARDSON, REID, CHRISTIE, HAUSNER + VITKAUSKAS WILL BE LAUNCHING THEIR NEW ABOVE/GROUND PRESS TITLES IN OTTAWA ON AUGUST 7TH, AS PART OF THE 32ND ANNIVERSARY READING/LAUNCH/PARTY! TICKETS ARE AVAILABLE! it is going to be a great event; did you see my report from last year's anniversary event?

To order, send cheques (add $2 for postage; in US, add $3; outside North America, add $7) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). See the prior list of recent titles here, scroll down here to see a further list of various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; and you know that 2025 subscriptions (our thirty-second year!) are still available, yes? i can totally backdate; and you know above/ground press has a substack now? sign up (for free!) for announcements, and even new features! catch recent/new interviews with Orchid Tierney, Jason Christie, Steph Gray, Monty Reid, etc.

With forthcoming chapbooks by: Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Stuart Ross, kevin mcpherson eckhoff, Michael Sikkema, Charlotte Jung and Johannes S.H. Bjerg, Jon Cone, Ben Ladouceur, Yaxkin Melchy (trans. by Ryan Greene, Mrityunjay Mohan, Laynie Browne, Nada Gordon, David Phillips, and probably others! (yes: others, (and: given I've been clearing a bit of a publishing backlog lately, I'm actually hoping to return to reading months' worth of submissions very soon,

August 2, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ian U Lockaby

Ian U Lockaby

is the author of

Defensible Space/if a crow—

(Omnidawn,2024), and

A Seam of Electricity

(Ghost Proposal, 2025). Recent work canbe found in Fence, West Branch, Noir Sauna, WashingtonSquare Review, Poetry Daily, etc. His translation of Mexican poet Diana Garza Islas was recently published by Carrion Bloom Books. He edits theonline journal

mercury firs

, co-edits the chapbook press LUCIUS withfahima ife, and lives in New Orleans.

Ian U Lockaby

is the author of

Defensible Space/if a crow—

(Omnidawn,2024), and

A Seam of Electricity

(Ghost Proposal, 2025). Recent work canbe found in Fence, West Branch, Noir Sauna, WashingtonSquare Review, Poetry Daily, etc. His translation of Mexican poet Diana Garza Islas was recently published by Carrion Bloom Books. He edits theonline journal

mercury firs

, co-edits the chapbook press LUCIUS withfahima ife, and lives in New Orleans. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It has not been out so long, so looking back on its publication interms of a life narrative turn is difficult. But having a book to share andknowing that the work and the object is having a life beyond me feels strangeand expansive. I don’t want to over-legitimize the book for book’s sake, butit’s true that a reader can live more immersively in a poet’s world with the physicalfact of a book, or can co-create a world with them, and I feel lucky that somepeople are living and co-creating with mine. It was also cool as hell, verylucky, and very affirming to publish a book with Omnidawn, which has long beenlegendary to me. Learning I won their contest (back in 2022) encouraged me tokeep doing my thing—after much rejection and discouragement, of course. I wrotemost of that book like 5 and 6 years ago, so it feels like a different era of aestheticattentions and impulses. Life has changed a lot since then. I always feel likemy new work is very different—I like to chase new music!—but there are certainlyshared concerns.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction?

I don’t think I came to poetry first—I think I wrote prose first, ina poets’ manner. I read a lot of fiction as a kid. I wrote everything/anythingthrough high school and college, honestly don’t think I considered genre much,maybe because my favorite writers even then wrote in-between things. And I alsodidn’t have much conception of doing it for any other reason than the making ofit, so I didn’t have to decide on a genre or figure out what to call it. Inever really tried to publish anything until much more recently. A professorsenior year of undergrad told me what MFAs and suggested I consider one, and Isaid thank you, ain’t no way. I was done with school, until years later,you know how that orientation changes sometimes. But I was still fully engagedwith literature, it’s always been a main obsession in my life.

I guess my last year of undergrad is probably when I stepped more firmlyinto poetry. I began to feel that poetry could contain or obtain thepossibilities of all other forms of literature because poetry is beyondliterature. It’s the form that felt most porous to life itself and opened newpores in life, and life was my main concern. I was exposed to some important thingsthat year—I read Aimé Césaire for the first time, when I was assigned Notebookof a Return to the Native Land, Clayton Eshleman’s translation, and I readit in one sitting late at night and everything was different afterwards. Icouldn’t believe it. Carried the book around with me for days rereading it. Iwas also working with a poet named D Wolach who introduced me to George Oppen anda lot of contemporary experimental poets—David Abel came to our class; Rob Halpern’s work was another revelation. That was an important dive into morecontemporary poetry and after all that I just kept going deeper.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

It varies a lot. Though it does tend to all be very slow for me,and rarely do first drafts appear close to their final form. Things come inbursts, then I tinker endlessly and put things away for long periods. Everythingis long gestation, and things get shuffled around. In a way, I feel like all thewriting projects are just the writing project, because anything mightbelong to another thing.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning?

They begin everywhere and anywhere. Sometimes I write fragments innotebooks or notes app when I’m driving, or voice-to-text dictations (I likethe errors), and later—days or months—I cull and combine lines and see what’sthere. Sometimes I work out a few stanzas by memory over the course of a couplehours before I write them down. Sometimes I decide I’m working on a longerthing and find a form and start throwing everything into that vessel for weeksor months at a time. I get ideas for “books” a lot, but you know, very few ofthem have actually happened.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy doing readings a lot, yes, usually. Especially if it’s agood space with some good people (‘good’ can be a lot of different ways, ofc). Thepoems change when I bring them to a reading, and I get excited by that. Onething I love about poems is their ability to shape-shift, to be differentthings at different times. I like to see what poems can be when they arearranged differently, new cadences, in new rooms… I don’t ever want the poemsto be static. The pressure before performing is good for editing too. SometimesI edit as I’m reading—like suddenly I realize just in time that a line orstanza really ain’t going to hit, or I decide I don’t like it, so I skip it andknow it’s never coming back. Or other times, I might accidentally say the wrongword and roll with it—gotta roll with it in my opinion—sometimes you say abetter word. All that is fun, making it live in whatever present.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

I have theoretical concerns behind my writing, sure, some arelasting, and some are constantly changing based on whims or readings or variousencounters. Sometimes I figure them out after things are written. Lately I’vebeen thinking about metaphors for God, and the language of infrastructure. I donot try to answer any questions; I prefer finding more questions. Answers in poetryand literature generally usually feel like dead ends, or concerns for themarketing, and I don’t care for that.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

There are so many kinds of writers, so it seems tricky to pin thatone down. But the kinds of poets I love best—I think they make things new(and/or to show how they are very old)—to expand what’s possible in language,and therefore in thought.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Depends on the editor? I’d say both. I like being made to questionchoices or defend them, when I feel like the editors have something of analigned vision or imagination. It was great, for example, working with KellyClare, Nora Claire Miller, and Alyssa Moore, the editors at Ghost Proposal on ASeam of Electricity, a chapbook of mine they published. They pushed me toexpand and sharpen it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

Here are two that often come to mind, from my teacher LauraMullen:

“Notice what you notice,that’s who you are as an artist”

“See what happens when youtry to test your endurance in the wilderness of experimentation”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetryto translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Very easy. They move through each other. Translation can be verydifficult of course, but it can also at moments, feel as easy as good reading. Andit opens new possibilities for my own poetry constantly. Questions oftranslation are also the essential questions of language.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

No routine. No typical days if I can help it. I have littlediscipline in such things, and I suppose I avoid routine. I always walk my dogin a different direction. I drink coffee. I look out the back door. I keep agarden in my yard, and sometimes I look at it while the water boils. If I canread or write first thing when I wake up, I love to, but that’s rare,unfortunately.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Anywhere but a screen. I like to walk. I also like to drive. Andto read, of course. Talking to certain friends puts a faith back in me—Iremember that a few people care about what I’m doing and are doing it too.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

River water or frying garlic.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Encounters with good visual art make me want to write. Music iseverything, it’s all music. One time I thought suddenly that my love of DMX asa kid had been the basis for my entire understanding of poetry. Not thespecifics of his lyrical style—but his sonics. I not sure that’s true, but I’mnot sure it’s not. The cadences of rappers I listened to growing up (Ghostfaceis a big one) are like bedrock in my mind.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

Aimé Césaire, Alice Notley, Etel Adnan, Ed Roberson, Henri Michaux, Lisa Robertson, CD Wright, Jimin Seo, fahima ife, Laura Mullen,Sebastian Gómez Mátus, Javier Raya, Carlos Cociña, Diana Garza Islas, many more.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get these two chapbook/press projects in operation that have beenlong in planning. (On the way! LUCIUS, co-edited with fahima ife—first chapsummer 2025—& mf editions, physical branch of mercuryfirs.org,coming…soon…). I’d like to be able to publish full-lengths someday.

Also, I’d like to put out a few albums of my own music that no onelistens to.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

If I hadn’t decided to go back to school when I was 28 or so, and endedup teaching as I’m doing now, I might have kept farming, which was myoccupation for most of my 20s. Often I wish I were a good carpenter. I don’tdream of employment; I do dream of non-employment. And I do think about usefulskills for the commune.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I have done and do plenty of something else’s, but I think Ialways come back to writing because, for one thing, it’s always available, alwaysan option, there as “a refuge but also a centrifuge,” as Eric Baus said to meonce. Like back in high school, which I did not like and did not excel, I’dignore lessons and write long free-associative prose-poem things for pages andpages, getting into a trance—that shit was thrilling, life-giving. It is a sortof meditation or transportation that I need—desperately then, and still now. Iwas semi-serious about music from my teens through my mid-20s, wrote lots ofsongs, moved to Austin for a while with a band. We were a mess and it fellapart quickly but I loved it and I miss that mode of creation/attention/collaboration.But it’s a lot to get band members and space and equipment together. And I tendtowards solitude—being in a band and playing out is very social. Writing hasbeen the most consistent thing, partly because it was something I could dounder any circumstances—moving around, broke, odd housing situations, etc. Poetrystays free.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

The Grimace of Eden, Now by Cody Rose Clevidence. I’vebeen watching for the first time—can’t stop thinking about WhereIs the Friend’s House? Also, Close-Up. Great-great-great.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A life outside of time (nothing doing).A book of poems called Vegetable With, that I’ve been working on quite awhile. A translation of Chilean poet Sebastián Gómez Matus’s collection AnimalMuerto. Another bunch of poems collectively called Half the Soybeans ofthe World Float by Me on the River, and maybe another bunch called 2 or3 Houses. Always a lot of different things. And always the editorial/organizational/etc.work of running mercury firs, and the aforementioned LUCIUS. All that isa ton of work, but I love it a lot.

August 1, 2025

Josh Fomon, Our Human Shores

Absence makes of me askeletal transmission. A future silence hummed into the ether.

In a fog of salt, themarsh blesses the morning. Reflects all our history, our inhuman attempt atliving, the sentimental idea of power. We see nothing until it reveals itselfor we seek out how far we can bleed. Human instead of human, another caterwaulclearing.

But this warm morning we washourselves against decaying concrete slabs. We watch misshapen waves pourflotsam foam over a rippled tide. We seep bleach and outdo the limits placed onus like the water-soaked logs piling on dead streets.

A flapping door wags itslife awake—I step through the frame, the threshold that once stood here, once sawthe ocean at a distance—the water slams it back close. Slams it open towardheaven. This music we search out, this magic humans hoard, but always thisslamming, this brackish song, this throttling praise. This new way of living. (“OurHuman Shores”)

Thelatest from Seattle poet Josh Fomon [see his 2018 ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], following

Though We Bled Meticulously

(Boston MA: BlackOcean, 2016), is

Our Human Shores

(Black Ocean, 2025), a collectionstructured as a quartet of extended poem sequences—“Our Human Shores,” “TheMemory Machine,” “Book of Skeletal Transmissions” and “The Somnambulist’sLullaby.” Working through a narrative around the Anthropocene, Fomon exploresextended poem-shapes and accumulations while examining human effect,environmental shifts, the limitations of writing and the way through which onewrites the world. “My sweet catastrophe—,” begins one of the pieces in thesecond section, “a cascading cool summer lemonade / spills into a plague ofants.” Composed as assemblages of line-breaks, poems in open form, prose poemsand sharp-edged couplets, I’m very taken by Fomon’s accumulations, and the fidelityof his lyrics, an offering of sharp observations shaped through both adirectness and an indirectness, with a musical undertone across every quarter. “Thebook is an unwritten infidelity—,” he writes, as part of the third section, “alie that anything can be complete—a benediction toward an infinite incompletenesswritten taut, gritted raw—a primal howl of caring enough to carry on to newhorizons—the books beyond the books, a patient penitent scraping.” A directness,and an indirectness; and a single narrative through-line stretched and extendedto impossible lengths. “How can we maintain distance when we don’t evenunderstand where we stand? The madronas glisten best when they’re wet.”

Thelatest from Seattle poet Josh Fomon [see his 2018 ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], following

Though We Bled Meticulously

(Boston MA: BlackOcean, 2016), is

Our Human Shores

(Black Ocean, 2025), a collectionstructured as a quartet of extended poem sequences—“Our Human Shores,” “TheMemory Machine,” “Book of Skeletal Transmissions” and “The Somnambulist’sLullaby.” Working through a narrative around the Anthropocene, Fomon exploresextended poem-shapes and accumulations while examining human effect,environmental shifts, the limitations of writing and the way through which onewrites the world. “My sweet catastrophe—,” begins one of the pieces in thesecond section, “a cascading cool summer lemonade / spills into a plague ofants.” Composed as assemblages of line-breaks, poems in open form, prose poemsand sharp-edged couplets, I’m very taken by Fomon’s accumulations, and the fidelityof his lyrics, an offering of sharp observations shaped through both adirectness and an indirectness, with a musical undertone across every quarter. “Thebook is an unwritten infidelity—,” he writes, as part of the third section, “alie that anything can be complete—a benediction toward an infinite incompletenesswritten taut, gritted raw—a primal howl of caring enough to carry on to newhorizons—the books beyond the books, a patient penitent scraping.” A directness,and an indirectness; and a single narrative through-line stretched and extendedto impossible lengths. “How can we maintain distance when we don’t evenunderstand where we stand? The madronas glisten best when they’re wet.” There’salmost a way through which he writes around his larger subject, articulating anoutline that can’t help but shape the book into a kind of absence, lines thatcircle around enough to highlight what is shown without showing. “Thebuffed-out metals / rusted through. / A belched-out mantra—,” he offers, aspart of the second section, “It’s me. It’s me. It’s free. // Pressed new conflagration within the sorrow / we wait, we miss that whichwe don’t know is missing.”

July 31, 2025