Rob Mclennan's Blog

October 18, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sophia Dahlin

Sophia Dahlin is a poet in the East Bay. Her first collection,

Natch

, was released in 2020 by City Lights Books, and her second book,

Glove Money

, is forthcoming from Nightboat. She leads generative poetry workshops and teaches youth creative writing. With Jacob Kahn, she edits a small chapbook press called Eyelet, and with seven other poets, she curates a weekly reading series at Tamarack, Oakland.

Sophia Dahlin is a poet in the East Bay. Her first collection,

Natch

, was released in 2020 by City Lights Books, and her second book,

Glove Money

, is forthcoming from Nightboat. She leads generative poetry workshops and teaches youth creative writing. With Jacob Kahn, she edits a small chapbook press called Eyelet, and with seven other poets, she curates a weekly reading series at Tamarack, Oakland.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When my first book, Natch came out, in 2020, it liberated me from the tremendous overwhelming exhausting desire to see my first book published. It liberated me from assembling new versions of Natch.

My second collection, Glove Money, is talkier than Natch—more narrative and gossipy and argumentative. Just as my first book liberated me, so too is Glove Money liberated of the carbon crusher pressure of the first book. Instead, it came together in a fleshier plantlike form. We’re good friends.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I like making sounds, which one does in poetry. That might have given it the leg up.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It’s the eruption of new work that hooks me—the poem breaking out of the quagmire. At this stage in my writing, the first drafts of poems usually look quite similar to the final drafts, but manuscripts change a lot draft to draft. I never take notes! Even as a student, I didn’t. I don’t know what notes are for. Just write the poem!

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I write fairly short and unrelated poems, doing my best not to think about what I am doing, and later I try to assemble them and think them through. The poems come quickly and the bulk of them get thrown away as the manuscript slowly asserts itself.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I freaking love giving readings, and I always learn about the work in the process. Readings help me cut the bullshit—even when it plays well (bullshit often does), if I feel unconvinced while reading it, chop.

I love hosting readings, and I love attending readings. My girlfriend once said to me, witheringly, “You’re just happy people are in a room.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

If there are questions behind Glove Money, they are probably “What is a transamorous sapphic poetics?” and “Wow is it wild that love is charging down the avenue to destroy me and I have no desire to run or what?”

The current question for most of us right now is probably, you know, what constitutes a human poetics, and what constitutes a machine poetics. And I’d say poets were working on those questions way before Language Learning Models were on the market.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writers have a lot of roles in larger culture! We (I’m speaking for the larger culture here) need to constantly relearn how to listen to language, and we need our experiences and our values and our strategies worded. Not all poets are good at all of those things. Not everyone is June Jordan, though if you are, you probably should be. But we need writers who can take apart a sentence, and writers who look out the window and describe the miscarriages of the breeze, and writers who can say Free Palestine and Don’t talk to cops.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

For books, essential. For poems, generally unproductive. I’ve had the luck of working with excellent editors on both my books (Garrett Caples from City Lights and Lindsey Boldt from Nightboat) who focused on shaping the manuscripts rather than, say, line-editing. That’s what I personally need editors for the most: help me see the forest. My eyes are full of tree.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best pieces of advice I have heard are: when you think the poem is done, keep writing, and: when you think the poem is done, end it immediately.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

For about five years I wrote a poem every day, and I didn’t allow myself to go to sleep until I had a draft. I slept poorly, but that’s how I learned how to write poems.

Nowadays, I work on new drafts, manuscripts, and writing-related tasks (this, for instance) Monday through Friday from about 2-4pm, on the high of post-lunch coffee, and before my evening teaching begins.

Of course, I often end up writing alongside my students in the evenings, so we can tack that onto the routine too.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If I really want to write poetry in the moment and can’t, I translate a poem from the Spanish.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Southern California tap water! Smells like tap, tastes like home.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Folk music, poetry translation (it’s a separate form!), theater, comic strips—comedy in general.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My girlfriend Violet Spurlock is very important to my work. I like to praise her beauty and win our arguments in my poems.

The Bay Area poets are kind of everything to me, by whom I mean the disorganized collective of leftist writers influenced by New Narrative, the New York School, Language Poetry, and Feminist Poetics here in the Bay who were already here hanging out when I moved to town a little before Occupy.

I learned how to be a poet in the world from them—which is, and this is my real advice for young writers: do it yourself, together. Make chapbooks, start a press, run a reading series, reading group, writing group. Forget the gods and dads and prizes that so rarely materialize, or ask too much of you when they do. Find comrades.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to grow old and join an all-retiree Shakespeare in the Park community theater collective. I would like to play Viola from Twelfth Night and Jacques from As You Like It.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Besides retired community-theater participant? Novelist, teacher. And I do teach and I do write novels, in fact.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

When I was deciding whether to devote my life to writing or acting, I was in high school, and looking around at my peers screaming for attention in the high school theater where we all hung out every lunch period, I became convinced that acting was bad for one’s character. That’s why I’m waiting till retirement to learn how to act. I’ll finally be ready for corruption.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just fed Vivian Blaxell’s Worthy of the Event through the book-return slot of my local library this morning. I thought it was gorgeous.

I recently saw Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev for the first time, at the Pacific Film Archive. It was undeniably great, but I was kind of devastated that you never see him painting. Violet says that’s the point. If so, I wish it weren’t.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Should I be honest, or gnomic?

I’m editing a collection of love poetry written during the pandemic, when my at the time brand new girlfriend and I moved in together “temporarily” ahaha.

I’m editing a collection of post-pandemic poetry about community art heaven, state-mandated hell (my brother is incarcerated), and dreams of anarchist maternity. Lots of Bernadette Mayer inspired forms in that one.

I’m not so much editing as re-reading and weighing the merits and humiliations of a book-length poem I wrote in a day. You know, like Bernadette Mayer.

I’m looking for a children’s literature agent who might be willing to sell some gay novels I wrote.

I’m being gnomic about another project that will, I imagine, fuck up everything else.

I’m writing new poems.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 17, 2025

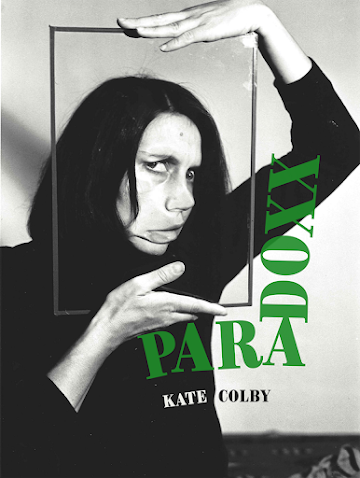

Kate Colby, PARADOXX

To lie by omission is toleave out the truth. To tell truth by omission is to leave out the lies, butthe lie of my continuity constitutes my continuity, without which there’snothing to tell. And if truth by omission is also to leave out misapprehensions,then I am not equal to the work.

Iam absolutely struck by the thoughtful and interconnected ongoingness ofProvidence, Rhode Island writer Kate Colby’s

PARADOXX

(Essay Press,2025) [a book I took with me to read in Ireland, as you well know], afirst-person non-fiction portioned across a wide stretch of exploratory,present prose. Each of her sections begins with a moment, thought or quote thatexpands exponentially out, as she reacts and explores, furthering to see howfar it might go. “Neither my experiences nor my memories are exceptional,” sheoffers, as part of the fifteenth section of her opening monologue, “HOW ITENDS,” “but the relationship between them interests me now that I have childrenmaking memories of their own. I do my best to ensure that they will havepositive memories of their childhoods, but the question of which will provemost important to them preoccupies me. When they are away from me at school andother activities, they are making memories we’ll never share, which makes mefeel that my kids are being ripped from me slowly like the wrong way to takeoff a Band-Aid.” Colby writes through the coordinates and considerations ofwomen writers, artists and thinkers, swirling around her own writing andthinking through her own parenting, and her own writing, and of those distancesthat might seem impossible but also seem impossibly interconnected.

Iam absolutely struck by the thoughtful and interconnected ongoingness ofProvidence, Rhode Island writer Kate Colby’s

PARADOXX

(Essay Press,2025) [a book I took with me to read in Ireland, as you well know], afirst-person non-fiction portioned across a wide stretch of exploratory,present prose. Each of her sections begins with a moment, thought or quote thatexpands exponentially out, as she reacts and explores, furthering to see howfar it might go. “Neither my experiences nor my memories are exceptional,” sheoffers, as part of the fifteenth section of her opening monologue, “HOW ITENDS,” “but the relationship between them interests me now that I have childrenmaking memories of their own. I do my best to ensure that they will havepositive memories of their childhoods, but the question of which will provemost important to them preoccupies me. When they are away from me at school andother activities, they are making memories we’ll never share, which makes mefeel that my kids are being ripped from me slowly like the wrong way to takeoff a Band-Aid.” Colby writes through the coordinates and considerations ofwomen writers, artists and thinkers, swirling around her own writing andthinking through her own parenting, and her own writing, and of those distancesthat might seem impossible but also seem impossibly interconnected.The poet Muriel Rukeyserfamously wrote, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?/ The world would split open.” Did she mean every little truth or oneoverarching one? Would all of the former add up to the latter? Either way,Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journal feels like what spills from thegash, evincing exhaustion and interruption—a mishmash of memories, sex,scatology, and mundane notes-to-self punctuated by shouty all-cappedimperatives from the inside of her forehead. But unconventional as it is, ClairvoyantJournal is thoroughly of its moment—the real-time transcription of the mindwas a project common to many of Weiner’s peers, including Bernadette Mayer andLyn Hejinian. Where is the line between her diagnosed schizophrenia and aliterary movement?

Throughone hundred numbered sections, Colby writes her thinking and experience throughand across an array of forebears, including Gerard Manley Hopkins, C.D. Wright,Kurt Vonnegut, Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost and Lyn Hejinian.One hundred sections, across one hundred days, reminiscent of the one hundreddays I composed my own one hundred pages across the onset of the Covid-era. Sheoffers the footnote: “One hundred days ago (on paper) I was spontaneouslyinduced to begin this writing by Jean Rhys’s unfinished autobiography. I’vesince spent years replacing nearly every word and sentence, letting the wholething gather and shed like a thousand skins of its snake. I wish my life in theworld was the same—that I could freeze it and work with what’s already heretill I knew it was fruitless and/or finished.” Her exploratory, accumulative self-containedsections almost give the sense of writing from the foundation of Hejinian’sclassic My Life (1980), utilizing biographical moments as the buildingblocks of structure, but through a more exploratory prose style, as abook-length essay, attempting to navigate, as she suggests on one point, herlife on paper. Referencing Hejinian’s Writing Is an Aid to Memory (TheFigures, 1978), she writes of memory and how it impacts being: “Writing Isan Aid to Memory is an experiment in omissionless self-depiction, where thesum of a life is an endless journey toward a shifting image of what it alreadyis. Great, but I’d rather see my memory in a display case. (It would have toinclude the display case.)” She writes of collectivity and individuality; shewrites of establishment and anti-establishment, negative capability and globalculture, folk songs and the Spice Girls. “Reflecting and reacting to the narrativeconventions of social media,” she writes, “the current literary approach toreality is self-reportage that represents representation within the exigenciesof late capitalism. I want to take a hard look at my role, but can I see itfrom inside the eddy?” She writes of forebears, as this moment near the endoffers: “I have a lot of obvious predecessors—Stein, Rhys, Wright, Hejinian. I don’tbegrudge their sexiness. I do resent my first wives, though, and all of themare men.” Her writing, her thinking, is remarkable, and this is a book worthsitting within for as long as possible. Or, as she writes near the end:

Mallarmé said, “Everythingin the world exists in order to end up as a book.” What baloney, but I’ll ownit. I process the world by considering how I’d render it on paper, and then myconclusions are the product of having been written. At times I hide from newsmedia, but am still beset by ambient information—birds and weather and aglimpse of a headline about a journalist’s beheading.

There should be a wordfor a word that should be its own opposite. Why does “behead” not mean to gaina head, in the manner of “bejewel,” “betroth” and “befriend”>

There’s a certain episodeI can’t write about because I would lie.

Willie wants to know whyall my writing rhymes.

October 16, 2025

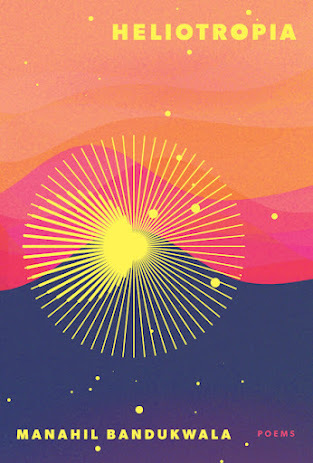

Manahil Bandukwala, Heliotropia

My review of Ottawa poet Manahil Bandukwala's Heliotropia (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2025) [

which won the 2025 Archibald Lampman Award, by the by

], following her full-length debut

MONUMENT

(Brick Books, 2022) [see my review of such here],

is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

.

My review of Ottawa poet Manahil Bandukwala's Heliotropia (Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2025) [

which won the 2025 Archibald Lampman Award, by the by

], following her full-length debut

MONUMENT

(Brick Books, 2022) [see my review of such here],

is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

.

October 15, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Roque Raquel Salas Rivera

Roque Raquel Salas Rivera

is a Puerto Rican poet,educator, and translator of trans experience. His honors include being namedPoet Laureate of Philadelphia, the Premio Nuevas Voces, and the inauguralAmbroggio Prize. Among his six poetry books are lo terciario/ the tertiary (Noemi,2019), longlisted for the National Book Award and winner of the Lambda LiteraryAward, and while they sleep (under the bed is another country) (BirdsLLC, 2019), which inspired the title for no existe un mundo poshuracán atthe Whitney Museum. In September 2025,Graywolf Press will publish his epic poem

Algarabía

. Roque currently teaches inthe Comparative Literature Program at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, isthe Creative Editor for

sx salon: a small axe literary platform

, andserves the needs of a fierce cat named Pietri.

Roque Raquel Salas Rivera

is a Puerto Rican poet,educator, and translator of trans experience. His honors include being namedPoet Laureate of Philadelphia, the Premio Nuevas Voces, and the inauguralAmbroggio Prize. Among his six poetry books are lo terciario/ the tertiary (Noemi,2019), longlisted for the National Book Award and winner of the Lambda LiteraryAward, and while they sleep (under the bed is another country) (BirdsLLC, 2019), which inspired the title for no existe un mundo poshuracán atthe Whitney Museum. In September 2025,Graywolf Press will publish his epic poem

Algarabía

. Roque currently teaches inthe Comparative Literature Program at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, isthe Creative Editor for

sx salon: a small axe literary platform

, andserves the needs of a fierce cat named Pietri.1 - How did your first book change your life? Howdoes your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

I published my first book when I was 25. I hadbeen obsessed with poetry since I was 12 and had been participating in readingsin San Juan along poets such as José Raúl "Gallego" González, HermesAyala, Mara Pastor, and Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro as a teenager. My style changeda lot after I want to SWP's Summer Writing Program when I was 18. There Istudied under the mentorship of Daisy Zamora and Akilah Oliver and got to hearAmiri Baraka, Chip Delany, and Robin Blaser.

I worked intensively on the poems in my firstbook for about five or six years after that. While I was in the ComparativeLiterature Program at Mayagüez—the same program where I now teach—I metLissette Rolón Collazo. She is an incredible editor and intellectual who ranthe queer colloquium, El Coloquio ¿Del Otro Lao? and the press Editora EducaciónEmergente. She was also my professor and when she found out I had a manuscript,she invited me to submit to the press.

After I submitted the manuscript, there was aprocess where it was reviewed by three different readers who decided if itshould be published. They decided on publication. I'm still so impressedbecause it was a long poetry book and the accumulation of many years of workingon an early style. Publishing it gave me a great deal of confidence in my work.Sometimes I go back and reread those poems and have such mixed feelings. I cansee a lot of how my style and work has changed, but the seeds are there. Thematically,questions of labor, coloniality, and gender were already present, as well and aformal interest in baroque metaphors rooted in daily life here.

I am incredibly grateful I published my first twobooks in Puerto Rico. This is my home. My forthcoming book la bella crisiswill also be published here with Semipermeable.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposedto, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I don't think I could answer that simply. We'dhave to have a shared definition of what makes poetry and fiction different. Ican definitely say I am a poet, not a prose writer. There is always a momentwhen I am reading a great novel that I think, "Wow. Impressive. That iswhy I'm not a novelist." Algarabía is an epic poem, a narrativepoem. It was incredibly fun to write, and the narrative was challenging, but itis a poem. It reads like an epic, not a novel.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

I usually take a break after a big project. By break I don't mean a long time,but a time when I don't write at all. I need to disconnect from poetry after abook. A reset. I need to hang out and share and celebrate the work I just made.It's not about a specific amount of time, but about enjoying the work! Aboutbeing alive.

Editing and rewriting is part of the writingprocess. Each poem requires different edits, some more than others.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don't know. I just write. Poems come. Some areshort pieces. Some don't belong anywhere. Others are long. Some are part ofcollections. Others end up being the beginning of larger projects. Books tendto be projects for me, but sometimes it takes time for a project to take shapeand make itself known to me.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter toyour creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. I love it when peoplerespond to my work. I love sharing my work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?What do you even think the current questions are?

Each book answers a different question andconcern.

My third poetry book lo terciario/the tertiary (1sted. Timeless, Infinite Light, 2nd ed. Noemi Press), a poeticresponse to the Puerto Rican debt crisis and a decolonial reconsideration ofMarx's Capital.

My fourth poetry book, while they sleep (under thebed is another country), a text written in dialogic fragments andinterspersed with prose poems reflecting on the lasting impact of the traumaexperienced after Hurricane María. It is centered con questions ofcoloniality, power, trauma, aesthetics and linguistic colonialism.

My fifth poetry book, x/ex/exis,offers poems that meet at the intersection of gender, nation, andlanguage.

My sixth poetry book, antes que isla es volcán/before island is volcano (Beacon Press, 2022), imagines a multiverseof decolonial futures for Puerto Rico.

My newest collection, Algarabía, whichwill be out on September 2, isan epic poem that follows the journey of Cenex, a trans being whoretrospectively narrates his life while navigating the stories told on hisbehalf. It inscribes an origin narrativefor trans people in the face of their erasure from both colonial andanti-colonial literary canons.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

Debates about the roles of writers in society areas old as writing. I can't talk about the role of "the writer"because I do not have a lot in common with some writers. Being a writer doesn'tautomatically make me anti-colonial or even socially aware. I think writersshould spend less time debating the role they should have and more time eitherwriting or acting. I go to protests as a person, not as a writer. I write as awriter. I say "Free Palestine" because I believe in a world withoutgenocide, colonialism, and profit margins. There are many writers who arecomfortable investing in Lockheed Martin. I am not one of them and I don'tthink I share anything with them except a general interest in literature.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I request specific editors for most of myprojects because the Spanish side of my books is written in a Puerto Ricandialect of Spanish and I am trans and my language reflects that, which means Ineed someone comfortable with inclusive language and respectful of my work. Iam not going to spend hours teaching an Argentinian copyeditor that in PuertoRico we say "cristal" when referring to a car window. It's not myjob. I have Puerto Rican editors.

As for editors in English, I also tend to requestpeople who are aware of linguistic colonialism and won't ask me to translate"múcaro" as "screech owl" when those are literallydifferent birds. After many years of bad experiences, I've become demanding andlearned to say "no." It isn't my responsibility to decolonize theeditorial world. All I can do is ask for editors that understand the gift thatis Puerto Rican literature. It is the bare minimum. I am doing all the work of translatingmyself and my life, the least I can ask for is that the translation be treatedwith respect.

For Algarabía I was quite luck. I workedwith editors that helped a great deal and were very thorough.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard(not necessarily given to you directly)?

A writer once reminded a group of us that we weregetting so excited about being featured in a well-known publication that wewere losing sight of the fact that it was an honor for the magazine to get tointerview us. That has been my guiding light for a long time. Be true to yourwork. Read and work hard. Never let colonizers disrespect you by giving themyour power.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres (poetry to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Those aren't different for me. I used the sameset of tools for both. If you've ever tried translating a sonnet, you know thatyou need to be a poet for that to be a great sonnet in the target language. Notall poets are translators, and not all translators are poets, but I am both andthey don't exist separately in my life. Literary translators should be writers.It is not a popular opinion, but I am always surprised that people think theycan render something extraordinary in another language without having a senseof how it sounds, of its literariness. If anything, I am simply focusing on aslightly different aspect of language when I am translating, but translating isa form of rewriting.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A typical day for me begins with class prep andcoffee because I am teaching four literature courses. This week we discussVladimir Propp's functions, Philip K. Dick and the movie Total Recall,Alice Notley's The Descent of Alette, Longinus's On the Sublime,contemporary Puerto Rican poetry, Farid ud-din Attar's The Conference of theBirds, Cervantes, and whether Popeyes or Church's Chicken has the best biscuits.Reading is a huge part of my writing practice. I am not one of those writersthat has a writing routine, but I am a rigorous and consistent reader.

When I am writing, I sometimes take long breaksfrom work and concentrate on writing. It is the only way I can workconsistently.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do youturn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read literature.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I had to call my uncle for this question. Jajaja.When I was a kid, I would visit my grandparents place on the road leading toAñasco for the summers. My uncle had a room where he lived and kept his toolsand mountain climbing equipment and I have a visceral smell of the mix of hisperfume and the equipment. He says it was probably Curve.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

Of course. Music: reggaetón, salsa, música detríos, nueva trova, hip-hop, have all influenced me deeply. I am obviouslyinspired by Villana (Villano Antillano), and I am inspired by everyday things:oil puddles, edibles, two changos fighting, going to the Walgreens. I lovemovies, from commercial films like Clueless or John Wick, to moreindependent productions like Andrea Arnold's films or Perfume de Gardenias.Lists feel pretty limiting, but in terms of visual artists, I love Cy Twombly,Natalia Bosques Chico, and Pepón Osorio and I am inspired by performanceartists such as Awilda Sterling and André Po Rodil.

15 - What other writers or writings are importantfor your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I am part of a community. Puerto Rican literaturewouldn't exist without our incredible efforts to keep it alive despitecolonialism. Other writers here are so important to me. My friendships withwriters such as Xavier Valcárcel, Roberto Ncar, Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro, HakeemTorres, Cristina Pérez Díaz, Angelía Rivera Mar, Gaddiel Francisco Ruiz Rivera,Gamelyn Oduardo-Sierra, Mayra Santos-Febres, üatibirí, Urayoán Noel, Mara Pastor, Isamar Anzalotta, Alejandra Rosa, Francisco Félix Canales Dalmau, Luis Negrón, Kadiri Vaquer Fernández, Veronika Reca, Willie Perdomo, Denice Frohman,Yara Liceaga, Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, Carina del Valle Schorske, Yamil Maldonado, Jean Alberto Rodríguez, Nicole Cecilia Delgado.... I know I've leftout so many people. I am sorry! My point is that my community is expansive andincludes a bunch of people. Even if we don't see each other regularly, we counton each other for a lot.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven'tyet done?

Visit every place in the Caribbean I haven't visitedyet.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

A filmmaker. I love movies so much. They take upa lot of space in my life.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

Sincerely, I don't know if I could have donesomething else, but I fell in love with poetry at a very young age and decidedI wanted to be a poet. I am now almost 40, so it has been about 28 years ofobsessing over poetry. I love it still and it has kept me alive.

19 - What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

I just reread The Descent of Alette and Altazar.They are still both great! I see too many movies, so I'm not sure what thelatest is, but I recently saw The Ugly Stepsister, which was great, andI saw Sinners in theaters, which I also loved.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Touring with Algarabía and organizing abig launch on September 13 at Casa Aboy with a line-up that includes someamazing writers and performers, drinks, and a book signing with Casa Riel.

October 14, 2025

Stephanie Bolster, Long Exposure

It is not something thatbegins.

Before there was landthere was water.

A place silted itself up.

Around the time of the pyramids

parts of other placesmade this place.

Some of the youngest landin the world.

People came to stay.

The river was why.

Where some already tradedon the high ground

a city of settlerssuggested itself.

Later a café that wouldsurvive the storm

and in the swampy parts fartherfrom the river

a place where those calledfree

and those who didn’t getto be

went on Sundays to dance.

Thelong-awaited fifth full-length poetry title from Montreal poet Stephanie Bolsteris

Long Exposure

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2025), a title I’ve knownof as in-the-works for some time, given an excerpt of the work-in-progressappeared as the chapbook

GHOSTS

(above/ground press, 2017). As well, hertitle that takes on a slightly different sheen, given that fourteen years havepassed since her prior full-length title. Long exposure, indeed. Bolster is, asyou might already know, the award-winning author of

White Stone: The Alice Poems

(Montreal QC: Signal Editions/Vehicule Press, 1998), which won theGovernor General’s Award for Poetry and the Gerald Lampert Award,

Two Bowls of Milk

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1999),

Pavilion

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2002) and

A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth

(London ON: Brick Books, 2011) [see my review of such here],as well as a small handful of chapbooks (including four from above/groundpress). Across her published work to-date, Bolster continues to focus on the book-lengthproject, but through a poetic that began with an attention to finely-honed andself-contained, densely-sharp lyrics, gradually evolving into this new flavourof book-length suite: a stretched-out sense of the fragment, which accumulateacross the sentence and staggered narrative into the form of the long poem. Asshe writes, mid-way through Long Exposure: “Rail cars full of oil slidfaster down / the slope until at the curve where the town / was a birthdayparty exploded and a woman / with cancer who’d chosen not to mark / this yearstill lives because she didn’t / go. All that long-dead / plankton lit the sky.”

Thelong-awaited fifth full-length poetry title from Montreal poet Stephanie Bolsteris

Long Exposure

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2025), a title I’ve knownof as in-the-works for some time, given an excerpt of the work-in-progressappeared as the chapbook

GHOSTS

(above/ground press, 2017). As well, hertitle that takes on a slightly different sheen, given that fourteen years havepassed since her prior full-length title. Long exposure, indeed. Bolster is, asyou might already know, the award-winning author of

White Stone: The Alice Poems

(Montreal QC: Signal Editions/Vehicule Press, 1998), which won theGovernor General’s Award for Poetry and the Gerald Lampert Award,

Two Bowls of Milk

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1999),

Pavilion

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2002) and

A Page from the Wonders of Life on Earth

(London ON: Brick Books, 2011) [see my review of such here],as well as a small handful of chapbooks (including four from above/groundpress). Across her published work to-date, Bolster continues to focus on the book-lengthproject, but through a poetic that began with an attention to finely-honed andself-contained, densely-sharp lyrics, gradually evolving into this new flavourof book-length suite: a stretched-out sense of the fragment, which accumulateacross the sentence and staggered narrative into the form of the long poem. Asshe writes, mid-way through Long Exposure: “Rail cars full of oil slidfaster down / the slope until at the curve where the town / was a birthdayparty exploded and a woman / with cancer who’d chosen not to mark / this yearstill lives because she didn’t / go. All that long-dead / plankton lit the sky.”Acrossthe three decades since her debut chapbook, Three Bloody Words (1996;2016), her poems have evolved from those original, diamond-carved shapes into alyric pulled apart, allowing her poems to breathe, and into this extended,full-length accumulated structure of fragments, accumulations and pinpoints. Thereis almost an element of the Big Bang to her evolution as a published writer,from that incredible density of lyrics in White Stone to this currentcollection, twenty-seven years later, exploded across the length and breadth ofthe boundaries of the poem, of the page. “Upheaval meaning the earth moved.” shewrites, mid-way through this complex patterning of fragments. “Unrest meaningno one slept.” What earlier held as restraint has still that same control, butone far more confident, mature; more open and adventurous, with each title-to-dateplaying a variation of the long poem, working in the book as her unit of composition.

Meanwhile the trees. It cannotbe said often enough

how many leaves. Yesterdaya cloud

in the shape of wind thegirl M said and a cloud in the shape

of the inside of a fish.

That you would give me gloves of the skin of a fish.

Asthe back cover of Long Exposure provides: “After Hurricane Katrina, the photographer Robert Polidori flew to New Orleans to document the devastation. In thewreckage he witnessed, and in her questions about what she saw in what he saw,Stephanie Bolster found the beginnings of a long poem. These questions led to unexpectedplaces; meanwhile, life kept pouring in.” In her own acknowledgments at the endof collection, Bolster offers: “What began in 2009 as an interrogation of myunsettling fascination with Robert Polidori’s photographs of post-Katrina NewOrleans became an education that has lasted for 16 years and does not end here.I am grateful to those who have supported this project, reading drafts, askingquestions, and posing challenges.”

There are people who makeminiatures of ruined libraries with trees in them.

There are people who takephotographs of miniatures of ruined libraries.

These are the samepeople.

The people who spendevenings looking at screens that display photographs

of miniatures of ruinedlibraries with trees in them know

it could always be worse.Are too lucky for their own good.

What does that mean.

Why must suffering.

Thepoems are more pointed, but the canvas across the collection, far broader. Bolster’spoems allow for such small precisions, as well as the spaces between thought,where the poems themselves, the collection as a whole, coheres. “My address acaption.” she writes, amid her exploration through New Orleans. She writes onhuman story, on those that document, on the long and short of aftermath. She writeson how some devastations run across and through generations, holding far worseeffect than what might be originally catalogued. “They are singular,” shewrites, “not. They are / You through not you or maybe you yes you / you and youand you / are me are not me I am not me.”

Bolsterworks through detail, through document, offering, as the late Canadian poet Dorothy Livesay (1909-1996) coined her own sense of the long poem, the documentary poem,although one that works primarily through her own response to response, throughsecondary sources. Bolster responds to these responses, citing a heft ofdetailed research, working a long poem around observation, exploring what,precisely, it means to observe. What it means, and what it might cost, throughthese disasters, man-made and preventable.

A bomb dropped on a ship

in a harbour off anisland

far from the coast, theship’s name

the name of a dry and inlandstate

the colour of the Mars ofthe mind.

Long Exposure circles the histories, stories, depictionsand documents around human disasters, from the Chernobyl nuclear explosion ofApril, 1986 (both the world’s worst nuclear disaster and the most expensivedisaster in history), the tropical cyclone Hurricane Katrina that devastatedNew Orleans in August, 2005 (and the extensive destruction, response and aftermath),Japanese internment camps in British Columbia during the Second World War, to theFukushima nuclear disaster and resulting tsunami in March, 2011. Bolster’sexposure is long, and purposefully so, and it takes a while for her study, herportrait, to come into focus across such intricate detail. She writes ofmemory, loss, and death. “In the dream where nothing’s left / is freedom. I holdmore / than I can.” Having worked poems around various degrees of Victorian control,attempting to shape the environment, forcing nature itself into their owndesignations and depictions, from zoos to gardens, here Bolster focuses on specificpoints of man-made disaster, articulating the human and environmental costs ofwhat could and should have been prevented, from the cruelty inflicted throughuprooting entire communities via internment, and multiple instances of capitalismand neglect leaving further communities more exposed to environmentalconsequence. She names observed, and observers; she articulates a multitude of voicesfrom ground level. The book asks without asking, what are we doing to each other?

He went inside and with nopower

he kept the shutter openlong enough

for what light there was

to seal the scene.

*

Until he presses, nothinghappens.

When he presses, thenothing affixes.

Prints are made.

Walk into rooms of walls,look

into the rooms on thewalls.

*

The larger the negative,the more.

In the print of the wreckof a room

(smaller than the room,larger than

the mind) are things we wouldn’thave seen

had we been there. (Someof us

were. Is there ever us?)

October 13, 2025

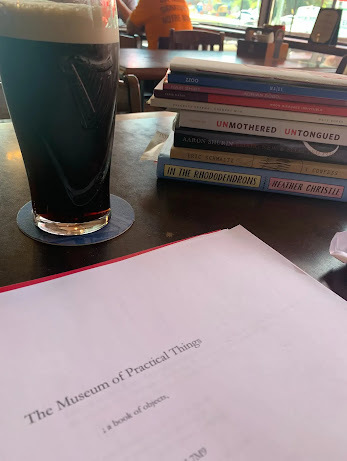

The Museum of Practical Things : , some notes from within the current work-in-progress, (and Ottawa book launch this Saturday,

In case you missed, I published an essay from within the current work-in-progress, "The Museum of Practical Things," over at my enormously clever substack. Check it out if you have a moment. I recommend it!

In case you missed, I published an essay from within the current work-in-progress, "The Museum of Practical Things," over at my enormously clever substack. Check it out if you have a moment. I recommend it!Also, there's a similar write-up I did on the current collection, the book of sentences (University of Calgary Press, 2025), which I'll be launching in Ottawa (alongside Stephanie Bolster launching a new Palimpsest title [oh no! she just cancelled!] and Zane Koss launching a new Invisible Publishing title) at The Manx Pub/Plan 99 at 5pm this coming Saturday. The piece originally appeared at my substack, but has been republished at Chris Banks' The Woodlot, alongside a couple of poems from the collection . Thanks much!

October 12, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Thea Matthews

Thea Matthews

[photo credit: CoskunCaglayan] is the author of

GRIME

and

Unearth [The Flowers]

, whichwas named one of Kirkus Reviews’ Best Indie Poetry books of 2020. Herwork has been featured in The Colorado Review, The New Republic, TheMassachusetts Review, Obsidian, and more. She lives and teaches inNew York City.

Thea Matthews

[photo credit: CoskunCaglayan] is the author of

GRIME

and

Unearth [The Flowers]

, whichwas named one of Kirkus Reviews’ Best Indie Poetry books of 2020. Herwork has been featured in The Colorado Review, The New Republic, TheMassachusetts Review, Obsidian, and more. She lives and teaches inNew York City.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was a triumph-over-trauma composition—a kind ofthroat-clearing for me as a poet and author. It was both a way to processsurvivor visibility and an extension of the research I was pursuing for myundergraduate thesis at Cal. The book became a vehicle to release what neededto be said so I could do the work I do now. In fact, I’ve come to accept thateverything I create as a poet today could not have existed without Unearth[The Flowers].

After finishing my MFA, I went through a phase of embarrassment becausethe book had been published before my graduate studies; I felt unrefined andeven cringed at my own work. That moment has thankfully passed. I am now deeplyproud of the book. As for the craft, I remain humbled and grateful to havetangible evidence of my evolution as a writer.

My two books, in fact, feel as though they were written by two differentauthors. My second collection GRIME is dramatically different, shaped bythe exponential growth I experienced during NYU’s MFA program. That bookreflects far greater intentionality and critical engagement with form, sound,and poetic lineage—asking, on the page, which poets I am in conversation with.I imagine my next book will serve as a kind of bridge, carrying echoes fromboth works into new terrain.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Poetry came to me first. The rest is history, as they say...

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

Projects come quickly, and the writing itself often arrives in bursts.But completing a poem—or an entire project—takes much longer. Nicole Sealey,one of my MFA craft professors, once distinguished between fire poets andcrystal poets. I have come to accept that I am a crystal poet: I need time,pressure, and patience before I am willing to abandon a poem and call it“done.” I am rarely, if not never, satisfied with my initial draft of a poem.Instead, I research more, revise, and return to the work again and again.Often, I’ll draft thirty poems in a single month, but it can take a year ormore before one of them feels finished. My poems, in other words, simmer in aslow cooker rather than sear in a sizzling hot pan.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Any new poem I write will emerge from one or more of these core themes oflove, survival, resilience, grief, despair, desperation, terror, violence… Ofcourse, there will be surprises—every poem begins with an idea whose finalshape I can’t predict—but having these thematic anchors helps me recognizewhich poems belong to a project and which can be set aside.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love and deeply enjoy doing readings because I love embodying the poemand the reenactment of emotion. Honestly, readings give me validation more thana heightened flow of creativity.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

In my writing, I wrestle with questions of representation andresponsibility: How do I avoid the trap of romanticizing pain? Can I subvertsensationalism rather than fall into it? When meditating on events that have actuallytaken place, I ask whether my approach brings justice to the subject matter. AmI honoring the essence of the people whose voices become speakers in my poems?Am I attentive to the gravity of the moment being reimagined on the page?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

That’s a great question, but I can’t say what I think the role of thewriter should be. I’m tired of hearing writers tell other writers what theirrole is in culture and society at large. If you write, then honor the roleyou’re in—celebrate it—and stay in your lane. I am a writer, yes, withphilosophical tendencies, but I am not a spokesperson for writers.

What I know for myself is this: I expose the underbelly of society whilegrappling with the human condition and notions of societal values. My focusremains: can I do that exceptionally well? The practice continues…

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I find working with an editor to be essential to the production process.I value the support of another set of eyes critically engaging with my work,offering feedback, and helping guide the book toward its fully realized form.I’m deeply grateful for the synergy I’ve experienced with the editors of mybooks. Thank you, Jessie Carver and Garrett Caples!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Robin Coste Lewis, one of my MFA workshop professors at NYU, once toldus: “Be good to your art, and your art will be good to you.” When I meditate onthis statement, I’m reminded to honor what arrives through me and to cherishit, rather than dismiss it with criticism or despairing envy. Perhaps one ofthe reasons people encounter writer’s block is that they don’t value thewriting that comes.

Robin emphasized that we write to reach what truly needs to be written. Ihold that advice close. No matter how negative or imperfect a draft may feel, Iwrite it out and let the poem breathe. For me, revision cannot come from aplace of negativity; it is an act of reimagining, of allowing the poem itselfto guide me toward its fullest actualization.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing routine moves in seasons. Thanks to the poet EK Keith, I makeit a point to participate in a poem-a-day challenge during one or more of the30-day months in a year (April, June, September, November). The remainingmonths are devoted to revising the poems I’ve written.

Throughout the day and week, I’m constantly collecting ideas—whetherphrases, key words, or dramatic scenarios. These can range from somethingplayful, like “grippy socks” or “if the world was a poem,” to somethingharrowing, like a dramatic monologue imagining the fatal subway burning of awoman by a drunk man who claims he remembers nothing. I collect these ideas sothat when the 30-poem challenge arrives, I have prompt-like springboards readyto jump from.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t believe my writing ever stalls. There may be a moment ofhesitation—Okay, can I write a poem? I know how to write a poem. I’ve done thisbefore…—but I never experience a true block. I keep my process fresh. I have astrong aversion to stagnation.

So, my approach to writing evolves constantly. I am methodical in how Iengage with subject matter. My relationship to form also provides inspiration:whether I’m working with a golden shovel, a cento, or a dramatic monologue, Iam critically engaging with other poets, and that conversation keeps mefocused. I don’t seek inspiration externally, because I am either generatingnew material from a collected set of ideas or revising existing work. Theseasonal cycle of writing and revision keeps both the pace steady andcreativity flowing.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Vanilla with a dash of cinnamon

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

My books are inspired not only by other books but also by human nature,visual art, and music. Grime, for example, is a musical genre whose harsh,jagged sounds parallel the stark realities in GRIME, the book. I grew upimmersed in punk and rock—especially grunge and alternative—so my writing oftenreflects that distortion: loud guitars, a solo here and there, and the tonalregister of that lyrical atmosphere. Movie soundtracks also inform my work andcan even accompany it; for instance, the Requiem for a Dream soundtrackby the Kronos Quartet aligns closely with the beats of GRIME.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I won’t be able to name them all, but I must acknowledge the work of Ai,Terrance Hayes, Robin Coste Lewis, and Bob Kaufman, as well as Sharon Olds’s SatanSays and Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler. Their influence resonatesdeeply in my own work and I continuously learn from them.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get an originally drafted screenplay successfully sold with producerrights.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

I have always been an artist. I think I would have been a visual artistof some kind or find some nest in music.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

O my soul yearned for it.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great film I read and watched was The Conjuring (2013).

19 - What are you currently working on?

My next book of poetry and a horror screenplay!

October 11, 2025

Sadiqa de Meijer, In the Field

I lost my notebook.

Thiswas, for a few days that summer, my distracted answer when people asked me how Iwas.

Itclearly wasn’t a disaster, I wanted to convince myself, but my body seemed toargue; there was a void in my chest, and I couldn’t relax, repeating my searchesuntil they were senseless compulsions.

Onlysome of that discomfort had to do with the possibility of exposure—that someone,anyone, might read my private scribblings. Sure, it was unsettling to imagineeye contact with that individual, to be so inwardly naked, but after thoseseconds of awkwardness, I would have my notebook back. The universe wouldresume its semblance of order. (“FOUND”)

The latest fromKingston poet (and current poet laureate for that city) Sadiqa de Meijer is thecollection of essays,

In the Field

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press/AnstrutherBooks, 2025), a sharp reminder of just how good her award-winning alfabet/ alphabet: a memoir of a first language (Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2020) [see my review of such here] was. You should pick up both books, really, to get a senseof how detailed, how precise, are her examinations of language and being; how,for her, the two are intertwined. The author of two prior full-length poetrycollections—

Leaving Howe Island

(Fernie BC: Oolichan Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] and

The Outer Wards

(Montreal QC: SignalEditions/Vehicule Press, 2020) [see my review of such here]—there is such astriking way her first-person prose so quickly allows a reader, with ease andcomfort, into not only her own thinking and experience and complexities, but thatof the people she encounters, considers, reconsiders and reflects upon. Across ninepersonal essays, she composes fieldnotes for and through her own experiences,whether searching for a lost notebook, through medical studies, travelling to Amsterdam(the city where she was born), or working as part of a study of life through aparticular corner of Southwestern Ontario. As she writes in the essay “In theField”: “I was working for a professor named Kee. He knew the geology of thecity, where there were moraines and buried creeks. He told me that trees holdso many symbiotic bacteria that if their wood and leaves were somehow erased,they would still look like phantoms of themselves.”

The latest fromKingston poet (and current poet laureate for that city) Sadiqa de Meijer is thecollection of essays,

In the Field

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press/AnstrutherBooks, 2025), a sharp reminder of just how good her award-winning alfabet/ alphabet: a memoir of a first language (Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2020) [see my review of such here] was. You should pick up both books, really, to get a senseof how detailed, how precise, are her examinations of language and being; how,for her, the two are intertwined. The author of two prior full-length poetrycollections—

Leaving Howe Island

(Fernie BC: Oolichan Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] and

The Outer Wards

(Montreal QC: SignalEditions/Vehicule Press, 2020) [see my review of such here]—there is such astriking way her first-person prose so quickly allows a reader, with ease andcomfort, into not only her own thinking and experience and complexities, but thatof the people she encounters, considers, reconsiders and reflects upon. Across ninepersonal essays, she composes fieldnotes for and through her own experiences,whether searching for a lost notebook, through medical studies, travelling to Amsterdam(the city where she was born), or working as part of a study of life through aparticular corner of Southwestern Ontario. As she writes in the essay “In theField”: “I was working for a professor named Kee. He knew the geology of thecity, where there were moraines and buried creeks. He told me that trees holdso many symbiotic bacteria that if their wood and leaves were somehow erased,they would still look like phantoms of themselves.”

It is the detailsthat occur through her thinking I’m struck by, offering moments almost asasides that provide the deepest meaning. “I imagine my objections areprincipled,” she writes of her medical studies, in the essay “Bloodwork,” “rootedin ethics and aesthetics, and then I doubt myself—because the hospital is acollective ruse, a place of faith in the reductive and separate, and I asurrounded by believers. My classmates sound eager to be in the building,mastering its workings, close to doing what doctors do. I begin to wonder if myaversion has other roots.” If reading helps teach us empathy, to understand another’sexperience from the inside, I can think of no better example than movingthrough this particular collection, as de Meijer provides a remarkable exampleon just how deep, and how detailed, the possibilities.

October 10, 2025

Sabyasachi (Sachi) Nag, The Alphabet of Aliens: prose poems

The Stopped River

By the time we returned,the river had stopped. It wasn’t a failure of God alone or the ruined robes ofpreachers. Not the bitter acids in the partisan trench or the cinder in the sibyl’seyes. Not the shattered spine after the steep climb or the weight of waterafter centuries of gravity. It was about the manner in which the sun had set. Isthere going to be nothing after this? The child was anxious.

When no one listened, heposed his question again and again, his tongue wagging like an ancient churchbell. When no one spoke, he cried like someone who had just heard death rattlehis mother’s ruined bones. No one knew how to console him.

Then his mother asked forink, a blank sheet, plain water. Painted a river that shone like a lamp on arainy afternoon and licked up the pale sky. And in the river, she plantedblithe waves. And down the stream, toward the edge of the sheet, she planted alittle whirlpool that moved like a furry one-eyed animal. And between thewaves, she planted a dark shadow of our sunk history.

Thefourth full-length poetry collection, and fifth title overall, by Calcutta-bornMississauga, Ontario-based Sabyasachi (Sachi) Nag, is

The Alphabet of Aliens: prose poems

(Mawenzi House, 2025). Following Bloodlines (2006),

Could You Please, Please Stop Singing?

(Mosaic Press, 2016) and

Uncharted

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2021), the poems across The Alphabet of Aliensblur the boundaries between short prose and lyric, subtitled “prose poems,” butlanding, more often than not, in the imperfect designation of flash fiction orpostcard stories. “At the corner of South Linn and Washington is a consolation,”opens the piece “The Curry Shop,” “but mostly empty. I entered once but didn’t eat,instead, suffering an immediate deflation upon touching the menu, tradedstories, conflating places and times.” I’ve noted previously how the self-declaredprose poems of the late Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014) [see my review of his posthumous selected here], said to be the father of the Americanprose poem, felt more akin to flash fiction than even the short fictions ofwriters such as Lydia Davis [see my piece on her work here] and Kathy Fish [see my review of her latest here], so the declared boundaries surrounding prosepoems have been blurred for some time. Across seventy-nine individual pieces, eachranging from one to three pages in length, Nag composes a series offirst-person narratives, of first-person reports, offering sketch-notes onactivity and an interiority, monologues blending observation, commentary anddocumentary. As the first of the three-sectioned “Place is a Sentence” begins: “Toprove you are capable of belonging you had to reveal your place. Since theywere busy touching different parts of your tongue you could say nothing else. Whatis place anyway? The scent of your tilled back garden, someone said,opened a window. And in the strong headwind when you floated up like a shadowof three pasts, they freaked out.”

Thefourth full-length poetry collection, and fifth title overall, by Calcutta-bornMississauga, Ontario-based Sabyasachi (Sachi) Nag, is

The Alphabet of Aliens: prose poems

(Mawenzi House, 2025). Following Bloodlines (2006),

Could You Please, Please Stop Singing?

(Mosaic Press, 2016) and

Uncharted

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2021), the poems across The Alphabet of Aliensblur the boundaries between short prose and lyric, subtitled “prose poems,” butlanding, more often than not, in the imperfect designation of flash fiction orpostcard stories. “At the corner of South Linn and Washington is a consolation,”opens the piece “The Curry Shop,” “but mostly empty. I entered once but didn’t eat,instead, suffering an immediate deflation upon touching the menu, tradedstories, conflating places and times.” I’ve noted previously how the self-declaredprose poems of the late Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014) [see my review of his posthumous selected here], said to be the father of the Americanprose poem, felt more akin to flash fiction than even the short fictions ofwriters such as Lydia Davis [see my piece on her work here] and Kathy Fish [see my review of her latest here], so the declared boundaries surrounding prosepoems have been blurred for some time. Across seventy-nine individual pieces, eachranging from one to three pages in length, Nag composes a series offirst-person narratives, of first-person reports, offering sketch-notes onactivity and an interiority, monologues blending observation, commentary anddocumentary. As the first of the three-sectioned “Place is a Sentence” begins: “Toprove you are capable of belonging you had to reveal your place. Since theywere busy touching different parts of your tongue you could say nothing else. Whatis place anyway? The scent of your tilled back garden, someone said,opened a window. And in the strong headwind when you floated up like a shadowof three pasts, they freaked out.”Whilethemes and subjects thread across and through these pieces, writing insecurity andfamily, life and death and longevity, fantastic fictions and the small moment, TheAlphabet of Aliens is a collection one could dip in and out of at random, eachpiece set in a locus uniquely itself, but held firmly in place amid thisbook-length suite. “For a change, I wanted to write a happy poem. One that’dhave no nightmares from childhood,” begins the piece “The SeeminglyIrreconcilable Differences Between a Happy Poem and a Sad Poem,” “no traces ofthe failures waking up at five before getting on the highway to clean up pasttransactions inside a gray cubicle, for bread. Not even the shadow of RayCarver by the window watching paper boys deliver in the snow.”

“Someonesaid,” begins the two-page “At a Street Play About the Soul,” “scientists havecreated a camera to film soul particles as they leave a cold body. It happenedyesterday. And as they were being presented the Nobel prize, my mother lookedup from her crewel work. But the soul is a slice of sapodilla, she said,sweet when you smell it, stones when you don’t.” His short narratives havea sheen of the surreal and fantastic in short bursts reminiscent of some of thework of Hamilton writer Gary Barwin, for example, or even that of Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany; providing a rather straightforward description or narrativethat suddenly takes (sometimes quietly) a surreal turn. Or a turn that suggestsall is not what it appears. As the piece “He Was Alone in a Park” begins: “Hewas alone in a park. We sat shoulder to shoulder, two drunks under a floweringmyrtle. Late August, newly arrived, I was looking for work. He wore a pinstripetux, the kind they rent for weddings. He looked shattered in his gray beret.”

October 9, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jumoke Verissimo

Jumoke Verissimo

is a poet and novelist living in Toronto. She is the author of two well-recognised collections:

i am memory

and

The Birth of Illusion

, both published in Nigeria and nominated for various awards, including the Nigeria Prize for Literature. Her most recent novel

A Small Silence

, received critical acclaim and was nominated for several awards, including the Edinburgh Festical First Book Award and the RSL Ondaatje Prize. It won the Aidoo-Synder Book Prize. Her writing explores traumatic re/constructions of everyday life and its intersection with gender, focusing on themes of love, loss and hope. She currently teaches in the Department of English Toronto Metropolitan University.

Jumoke Verissimo

is a poet and novelist living in Toronto. She is the author of two well-recognised collections:

i am memory

and

The Birth of Illusion

, both published in Nigeria and nominated for various awards, including the Nigeria Prize for Literature. Her most recent novel

A Small Silence

, received critical acclaim and was nominated for several awards, including the Edinburgh Festical First Book Award and the RSL Ondaatje Prize. It won the Aidoo-Synder Book Prize. Her writing explores traumatic re/constructions of everyday life and its intersection with gender, focusing on themes of love, loss and hope. She currently teaches in the Department of English Toronto Metropolitan University.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I think I can compare my first book to seeing a child take her first step. I wrote my first book in my teens, at 18 or 19, and it was published when I was in my early twenties. It was well-received, and it definitely paved the way for me. You know how the first step gives a child confidence that she can do more, I guess that was what it meant for me. Over the years, my writing has evolved so much, as my thinking and exposure and it shows in my subsequent works. Still, I will always cherish my "baby steps," for emboldening me to think, I have subdued the fear of not being heard. The excitement remains when I publish a new book, but this time it is not about taking a first step, it is about the possibilities of where I can reach with these steps, and how much it is also about preservation, that is beyond me. I have come to see how writing also becomes a form of survival, not in an existential way, but in a way that explores a de/reflection, which I am thinking of as how we are not just shattering the image of my previous reflections, a distortion that may or may not bring clarity, and even instances of contemplation that feel impulsive, all while quieting the many forms of anxieties that are mine and those that belong to others.

I guess the thing about my most recent work, Circumtrauma , is that it ascertains the possibilities of the more that I can do. You know, each new book gives its own clarity, and it is different. I feel like I grow an inch when I publish a new book, and that is what I feel like now. I can see how, in my recent writing, there is the breaking down and moving beyond a past self-image or identity I have had about myself. I think I remain consistent and intentional, such that my poetry becomes what Joe Brainard would describe as “that certain something we so often find missing.” When I say about myself, it is also about how I now see the world and it is not necessarily me in the poems, but me learning to make room for others in my poem, in a way that I can read the evolution of self in it. Also, I guess I am now coming to the realization that in my writing generally, completion is not always an endpoint but a moment of cessation. I also know, more than ever, that the writing I do now is necessary, even when it feels disorienting. There is the memory of the fragmented self that wants to read a clear and coherent image from inside and outside of themselves.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'd say music. I know music isn’t poetry, but there's a connection, and that's what first introduced me to it. Looking back, music filled my childhood home. I come from a rich culture of oral poetry, and this influenced how I first experienced it. It also showed me that poetry could be in anything and everywhere. The idea of poetry as a written form in the English language, however, came from a set of old books. I don't know if it was the same in Canada, but in Nigeria, it was fashionable among the Silent Generation and Baby Boomers to have a shelf of encyclopedias in their living rooms. My dad, who is from the Silent Generation, had a four-volume set of The World of Children’s Encyclopedia. I read those four green hardbacks until they were worn out. They contained excerpts of poetry from classic Western literature. I would copy the poems and then write my own. I also remember my brothers being assigned poetry anthologies like Poems of Black Africa, edited by Wole Soyinka, among others I can't recall now. It all feels so distant, and too many things have dragged along those memories.

But, meeting Odia Ofeimun, a Nigerian poet who had a huge collection of books and old newspapers at the Association of Nigerian Authors was a different experience. He had so many books in his house, and you couldn’t walk past a wall that didn’t have a shelf leaning against it. It was a dream come true, nothing like I had seen. He was also eager to discuss the books, so I was constantly reading, though it all feels like a blur now. He’d suggest one book and then another and then another. I was also meeting other poets, and I guess that's a short version of how poetry came to me. These are the things I can remember, but how I came to poetry is simply me realizing that I found it to be a dependable place to hold myself together.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I took a while with this question because I am thinking about how each writing project is different and how it situates my own transformation as a person. You start off thinking you’d end up this way and then you end up another way. I see my writing the same way. I mean, I can only make plans, but the writing itself can re-invent itself along the way and it happens all the time. I am lucky sometimes, even with airtight planning, these things give way. So, I’d say, it all depends on what I am working on.

Circumtrauma, my latest poetry collection, that Coach House is publishing, emerged from my PhD work, and that it is the creative aspect of years of research and thinking on how best to resolve how several negative emotions that become grievances following a war are transmitted across generations. The theoretical thinking of making sense of resentment and hatred became an interest in identifying the many emotions that become transferable across generations. I then began to think of how this translates into the way war victims narrate a war, especially one deepened by colonial legacies and conflated by years of political misrule. What is remembered? Whose voice is the heard and whose, gets repressed? How deep does the felt emotions of the crisis embody generations unborn—especially when what is passed on as negative emotions like “hate” and the “pain”? What is remembered, the pain or the event?

In this case, the poetry shifted from impulsion to the deliberateness in letting time present its own perspective and offer me a chance to re-see and deepen my questions. It was about experimenting with narratives that are beyond mine and trying to invent traces of the leftover emotions in them.

My point is, each writing project dictates its own urgency, and this does not always translate to time. It could be how much time is needed to work around form and structure or simply fumbling with word choice or even an urgency that is primarily just about the anxieties of conceiving what is felt—you know that idea of knowing there is a poem in the vibrating silence that is concealed but asking to be let out.

In all of this, what emerges are first drafts that look nothing like their final shape. The initial writing is the fragmented memories that slip into the mind in a quiet time, the rough scribbles on notes here and there collected from conversations, eavesdropping, chat groups, or wherever, the unwritten short story that imagination brought in a dream. The first draft feels like a breakthrough until I read it the following day. I can tell you for free, anything I send out without reading over and over again turns out to be a disaster. I have realized that I am a logorrheic thinker, and I will always need to clarify my thoughts and make a microcosmic universe from the vastness of my thoughts, so I think it over and over and over again and write. Maybe we can say the writing project starts when I begin to focus my thinking on a particular project. And how long this thinking happens is not something I can control in a sense of "this should end now." I know most writers would say starting any particular project begins with thinking, and that takes time. Some ideas clarify themselves as you begin to think through, and the layers of complexities, or the absence of them, become what I anticipate in the writing. I do like to think, and that’s my favorite thing in the world: to just be and think of whatever I am fascinated with, to contemplate over a sentence or a word over and over, to feel excited about an image and ponder its many sides. Thinking is writing for me, and my belief is that if I invest adequate time in the thinking, I may—may—just be able to have an idea of where I need to go with the writing. So, I really do not know how to quantify the duration of the thinking process, but I have come to know that the ability to give time to an idea in my thinking may result in what feels like a speeding up of the writing, as I have done most of the structure and imagining in my head, and then I start the writing. Most of the time, what I imagine is different from what comes out—and that is totally fine. The point is to have something to work with, and I try to beat it into shape, not with the intention to have what I pictured in my head, but to have what best conveys the emotions surrounding what I was trying to say.Thinking for me takes time and it is the most important part of my writing, and if I can think carefully and begin to visualize it to a point where I can feel it in my fingers and my synapses begin sending signals that drag me to my desk, I obsess over the project until it is done.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like to think of Poetry as being in everything, actually, I mean, it's about learning to listen and to pay attention to how we exist and interact with the world. It is the art of refining a scattered focus into a lingering image, a word, a film, a book, or a piece of writing, and then interrogating it because it aligns with or goes contrary to your own view. Poetry is a profound act of translation. It's the moment when the chaos of experience is distilled into the precise order of language. It is not merely a record of observation but a transformation, where the poet's inner life, and we talking about their emotions, intellect, and memory, collides with the world beyond the person. It is the lens’s fleeting frame, the memory that lives in a single word, the music of a phrase that becomes a memorial of gestures, and the material that births a new form, it is the dance on the page when the music stops. Poetry is the brave, it is the vulnerable, it is the work of feeling and thought. It is the language of suggestion and compression, that leaps beyond the sentence of a story. It is a dialogue with the self and an invitation to the reader, to think together and see one thing, but in many ways.

So, a poem begins when I can capture the poetry in that moment. A project could start when there’s an encounter with what feels like an idea asking to be upturned, observed, and disrupted. The problem, however, is that some ideas feel ready, but the moment I go into thinking mode, they go nowhere. I may not be the one to recognise the poetry in that moment. I feel that when I do, the instances when I can make poetry of an event or a moment, I feel deep gratitude.

I have written standalone poems and one or two short stories, but I love to work on larger projects from the beginning. I like the wholesome experience of not knowing where it will lead me. There's something very final—and feverishly so—about short pieces that can be satisfying but also abysmal in their abruptness. Perhaps it is also because I am a pathetic ruminator, and reflecting on the turns and shifts of a book is more satisfying. Still, I do write short forms; I only wish I could give them more time.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?