Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 4

September 18, 2025

2025 Ottawa Book Awards shortlist : On Beauty: stories,

Thanks much to the City of Ottawa! Yesterday it was announced that my short story collection,

On Beauty

(University of Alberta Press, 2024),

was shortlisted for the 2025 Ottawa Book Awards

! This is my first ever appearance on a shortlist for this particular award, so that's pretty exciting. Congratulations, also, to the other four on the shortlist: Manahil Bandukwala, for

Heliotropia

(Brick Books); Nina Berkhout, for This Bright Dust (Goose Lane Editions); Paul Carlucci, for

The Voyageur

(Swift Press); and Chuqiao Yang, for The Last to the Party (Goose Lane Editions). Hooray all! I've only actually seen Chuqiao's book of the quartet [see my review of such here], and it is remarkable, which makes me curious to see the other three.

Naturally, I think you should pick up a copy of my short story collection

[check out here for some links to reviews of the book, although it's Salma Hussain who really gets it], as well as the other nominated titles. There's plenty of time to read all five books, I'd think, before the winner gets announced on November 15th, yes?

Thanks much to the City of Ottawa! Yesterday it was announced that my short story collection,

On Beauty

(University of Alberta Press, 2024),

was shortlisted for the 2025 Ottawa Book Awards

! This is my first ever appearance on a shortlist for this particular award, so that's pretty exciting. Congratulations, also, to the other four on the shortlist: Manahil Bandukwala, for

Heliotropia

(Brick Books); Nina Berkhout, for This Bright Dust (Goose Lane Editions); Paul Carlucci, for

The Voyageur

(Swift Press); and Chuqiao Yang, for The Last to the Party (Goose Lane Editions). Hooray all! I've only actually seen Chuqiao's book of the quartet [see my review of such here], and it is remarkable, which makes me curious to see the other three.

Naturally, I think you should pick up a copy of my short story collection

[check out here for some links to reviews of the book, although it's Salma Hussain who really gets it], as well as the other nominated titles. There's plenty of time to read all five books, I'd think, before the winner gets announced on November 15th, yes?September 17, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with catherine corbett bresner

catherine corbett bresner

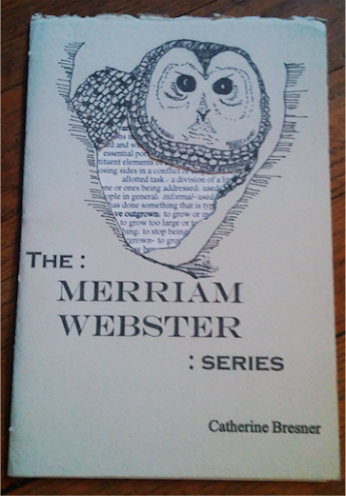

(they/she) are the author of the chapbooks The Merriam Webster Series (2012) and

SomeBreak A / Others Say Do

(Press Brake, 2025), and the full-length poetrycollections

Can We Anything We See

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025),

the empty season

(winner, Diode Editions Book Prize, 2018), and the artist book Everyday Eros(Mount Analogue, 2017). Their poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in FENCE, VOLT,b.l.u.s.h, Denver Quarterly, Sixth Finch, Fonograf magazine and elsewhere.Currently, she are the publicist for Wave Books and co-edits Spirit Duplicator,a biannual mimeograph magazine of poetry and art, with the poet Adam Tobin.They believe in a free Palestine.

catherine corbett bresner

(they/she) are the author of the chapbooks The Merriam Webster Series (2012) and

SomeBreak A / Others Say Do

(Press Brake, 2025), and the full-length poetrycollections

Can We Anything We See

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025),

the empty season

(winner, Diode Editions Book Prize, 2018), and the artist book Everyday Eros(Mount Analogue, 2017). Their poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in FENCE, VOLT,b.l.u.s.h, Denver Quarterly, Sixth Finch, Fonograf magazine and elsewhere.Currently, she are the publicist for Wave Books and co-edits Spirit Duplicator,a biannual mimeograph magazine of poetry and art, with the poet Adam Tobin.They believe in a free Palestine. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

Imade my first chapbook, which was handstitched at Flying Object, an artistspace that existed in Hadley, MA from 2012-2015. I was so proud of this chap,and now I am bashful of its poems, which are pretty bad. But the design isbeautiful, I think. Here is a picture:

Atthe time of my writing the empty season, my first full-length book, my fatherwas dying quickly and prematurely, a long-term relationship ended, and I wascoming out as queer. So in a way, it feels like my life was changing in verydramatic ways and the book was a culmination of a lot of different forms whichI was playing around with at the time. Mainly, poetry comics, which I don’treally do anymore.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to,say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry when I was reallyyoung. My middle school best friend, the poet Katie Fowley, and I would go intoCambridge on a Wednesday night to hearpoetry in the basement of the Cantab Lounge in Central Square, MA. This wasduring the days when Patricia Smith was reading a lot. We were twotwelve-year-old kids and the poets there took us under their wing and treatedus like adults. It all felt very glamorous, especially for me, because I wasraised by a strict father who wouldn’t even let me watch TV during the week, andin a moment of clarity, made this one exception, so I treasured these trips.

The first poem I remember readingover and over again was Ginsburg’s “Sunflower Sutra” in HOWL, trying tomemorize it just so that I could listen to it all day in my head. Also, I havea middle school memory of a performer named Odds Bodkin who came into my schoolto perform, over the course of three days, The Odyssey in bard.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

It comes when it comes, which isalways a surprise to me. I don’t start projects as much as I get languageearworms that need to wriggle their way out or I get obsessed with asubject and then naturally I startwriting into it. A poem might start with a line, which may not even be itsfirst line. Sometimes it is not a line but just one word that needs someinvestigating. I write most days, and I am not very disciplined. Over theyears, my poetry practice has not been as much about daily writing as much as itis an act of attention in the day.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

It changes with each poem. If I ampaying attention, there is nothing ‘usual’ about the beginning of a poem atall. It is a surprise and a calling most of the time. For example, Can WeAnything We See, my most recent book, is a long poem concerned with A.I. andpersonhood. For this book, it would seem like a “project book,” and in someways, my writing constrictions made it a project. But I didn’t set out to writea book. I followed the language that became a long poem, which happens to bebook-length. It is important in my practice to make that distinction, as mypoems aren’t very good when they come from a place of knowing or planninginstead of coming from a place of curiosity. For CWAWS I started writinglanguage – about a line or two a day – in response to various randomly selectedAI photojournalism pictures that I found through keyword searches. The line wasusually written on a typewriter so that I would need to pull my attention awayfrom the screen to write. I think I might have even started our writing in pen,but then handwriting seemed too lyrical for the poem, and the language demandeda serif font. I wrote pages and pages of these lines, most of which did not endup into the slim manuscript. So by starting from a place of ekphrasis butomitting the photographs, I created a sort of reverse ekphrastic for thereader. Human beings are always doing this – filling in the gaps with our ownnarratives, and this poem lays that bare.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love giving readings, but I hate togo last and I don’t like Q&A’s. My first experiences of poetry were aloud. Sometimesreading aloud is a way I can edit my poems, and I’ve been known to edit a poemextemporaneously during a reading. Andmore than reading my own poems, I love listening to other people’s poems, whichwhy I typically request to read first, even at my own book launches. AlthoughI’ve given many readings, I always getreally nervous, and I am relieved to sit down and relax and give all of myattention to the poets around me afterwards. Also, talking is perhaps my leastfavorite form of communication, which is why I get shy at live Q&A’s. I’drather just folks come up to me after a reading and engage me in conversation.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

This is such a beautifully impossiblequestion for me to answer, as the theoretical questions I have changebook-to-book and poem-to-poem. For CWAWS, I was really curious (and yes,concerned) with the ways in which AI technologies can not only shape anindividual’s sense of personhood but also shape an individual’s sense ofcollective identity in relation to that personhood. What keywords drive dailybrowser searches? What do these searches say about our fears and obsessions?How can we believe anything we see? In what ways do we rely on photos,specifically photojournalistic ones, for evidence and why? How do captionsshape our meaning-making?

As I write this, I am rethinkingabout a lot of these questions not only because I just read today that AI’sleading developer, Nvidia, is worth 3 trillion dollars, a staggering numberthat could feed countries and end wars. Instead, the U.S. is spending billionsof dollars investing in the “Lavender,” an “A.I. targeting system used to bombGazans with little human oversight and permissive policy for casualties.” When I wrotethis poem, however, I remember that I was thinking about my own gender identitya lot in relation to AI, and in my digging around., I came across “The Gender Panopticon: AI, Gender, and Design Justice” by Sonia K. Katyal and Jessica Y.Young,” which is cited in my notes,. This article started to shape a frameworkfor my thinking around the many ways AI shapes a collective sense of personhood,for better or worse (and as the authors argue, more often the latter).

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

I think that depends on the writer,the specific culture, and the current moment. Which is to say, I don’t thinkthere is a singular answer. For me, my role is only to write.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find it to be both. I do getpleasure and a thrill sharing my work with a trusted reader/editor for thefirst time. I have an intimate list of poets who challenge and inspire me, andwhom I often share early versions of my work.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

“Don’t pay for an MFA.”—Peter Gizzigiven to me directly at my undergraduate thesis dissertation.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between textto visual work? What do you see as the appeal?

I take photographs for the samereason I write poems. I am curious about the result. And it is very easy tomove between the two mediums for me, as photography seems very externallyfocused, and poetry seems grounded in interiority. I like to think of each act asa kind of breath, poetry an inhale and photography an exhale, and I breathethroughout the day.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep,or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I am not a disciplined writer, but Ido write daily. I keep a notebook with me everywhere I go. A typical day for mebegins with making my daughter her lunch while slugging coffee. I am alwayswriting in my head until it is on the page.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turnor return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I would say that I am lucky in that Idon’t really get stalled, not in the ‘writer’s block’ sense. But the truth is Ido get stalled… by my chronic clinical depression. I have a history of outpatientand inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals, and I have also struggledthroughout the years with alcoholism and self-harm. As I get older, I try toshare about this as candidly as possible when appropriate, as my experience isvery common within writer communities, but often not discussed. So where do Ireturn for inspiration? In a way, I could say medication and therapy, as thesethings restore inspiration to me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

mothballs and pipe tobacco

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Yes, all of the above and more.

15 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The writers who were specifically onmy mind and on my nightside table in the creating of Can We Anything We Seewere Renee Gladman’s Plans for Sentences, Rosmarie Waldrop’s Lawn of theExcluded Middle, Radi Os by Ronald Johnson.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

Make pottery. Learn to crotchet. SpeakSpanish fluently. Start a children’s book imprint. Write a review for the film HOMEstarring Isabelle Huppert and directed by Ursula Meier.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I don’t think it is an either/orsituation, but I do have dreams of becoming a beekeeper someday.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just started finishing a long lyric poem called SomeSay Break / Others Say Do which I started in October 2024. The firstthirty-five pages were published in a chap from Press Brake.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 16, 2025

Guy Birchard, Most By Books

Preface

Though he daily invocate,though he sacrifice Hecatombs, the Muses and the Graces still upon the Duncelook asquint. John Donne profanely paraphrased.

Why on earth in a guy’seighth decade would he contemplate issuing yet another unwanted masculiniststream of invitations and affection? or affectation and invective.

Why?

Jack B. Yeats answeredThomas MacGreevy: “I get headaches from reasons… I think Reasons arevery little use down here. But up aloft, just after St Peter shuts the gategently on us, with us within, we will be as happy as lambs throwing littleround reasons from hand to hand until they roll over the side and flop downinto Hell…”

The Ideal Reader would beshe who takes as much time to read a page as the author took to write it.

It is too much to ask.

Iwas recently intrigued to catch a copy of Victoria, British Columbia poet Guy Birchard’s Most By Books (Victoria BC/Parry Sound ON: Symple PersonePress, 2023), a chapbook designed and produced by poet Jack Davis [see my review of his own full-length debut here] “in a private edition of forty copies.” I wasfortunate enough to discover Birchard’s work through a title produced by BethFollett,

Only Seemly

(St. John’s NL: Pedlar Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], a title I picked up a small number of extra copies of when thepress folded, the book is just that good. I give them away, here and there, to those that I think should be reading it, as well as to counter the fact that thereis something about Birchard’s approach to almost going out of his way to sitjust under the radar, releasing new work with small or even smaller, ephemeralpresses. Over the past forty-plus years, Birchard’s list of published books andchapbooks includes Baby Grand (Ilderton ON: Brick Books / Nairn, 1979),

Neckeverse

(Newcastle upon Tyne: Galloping Dog Press,1989), Birchard’s Garage(Durham UK: Pig Press, 1991), Twenty Grand (Boston MA: Pressed Wafer,2003), Further than the Blood (Pressed Wafer, 2010), Hecatomb(Brooklyn NY: Pressed Wafer, 2017),

Aggregate: retrospective

(BristolUK: Shearsman Books, 2018),

VALEDICTIONS

(Ottawa ON: above/ground press,2019) and

Montcorbier

(above/ground press, 2020), with a further titlethrough above/ground press to appear later this fall. Might a selected poems atsome point be worth doing? I would certainly think so.

Iwas recently intrigued to catch a copy of Victoria, British Columbia poet Guy Birchard’s Most By Books (Victoria BC/Parry Sound ON: Symple PersonePress, 2023), a chapbook designed and produced by poet Jack Davis [see my review of his own full-length debut here] “in a private edition of forty copies.” I wasfortunate enough to discover Birchard’s work through a title produced by BethFollett,

Only Seemly

(St. John’s NL: Pedlar Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], a title I picked up a small number of extra copies of when thepress folded, the book is just that good. I give them away, here and there, to those that I think should be reading it, as well as to counter the fact that thereis something about Birchard’s approach to almost going out of his way to sitjust under the radar, releasing new work with small or even smaller, ephemeralpresses. Over the past forty-plus years, Birchard’s list of published books andchapbooks includes Baby Grand (Ilderton ON: Brick Books / Nairn, 1979),

Neckeverse

(Newcastle upon Tyne: Galloping Dog Press,1989), Birchard’s Garage(Durham UK: Pig Press, 1991), Twenty Grand (Boston MA: Pressed Wafer,2003), Further than the Blood (Pressed Wafer, 2010), Hecatomb(Brooklyn NY: Pressed Wafer, 2017),

Aggregate: retrospective

(BristolUK: Shearsman Books, 2018),

VALEDICTIONS

(Ottawa ON: above/ground press,2019) and

Montcorbier

(above/ground press, 2020), with a further titlethrough above/ground press to appear later this fall. Might a selected poems atsome point be worth doing? I would certainly think so.Thetitle of Birchard’s latest collection, Most By Books, is excised from alonger quote, set on the title page to include the full—“They do MOST BY BOOKSwho could do much without them.”—lifted from the prose work Christian Morals(1716) by the English writer Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), a posthumously-publishedwork originally composed as advice for his eldest children. Through nearlyforty pages of lyric heft, Birchard reshapes Browne’s advice, leading byexample through a selection of poems rife with reading. “From my fingers,”begins the poem “Mustapha Reached His Koran Back,” “off the shelf from which I hadcasually picked / up The Book in barely enough time to open it, Mustapha, with/ dignified tutting, his father projecting approval, retrieved the / Koran frommy hands, from before my eyes.” These are poems built from books, from not onlyreading but years of intense, dedicated and ongoing study; the kind ofattentions that lesser poets proclaim loudly across author biographies,entirely the opposite of what Birchard writes for his: “Scholar of nothing. Nodegrees. No prizes. Neither profession, trade nor career. A lay poet.Anglo-Canadian.”

Thereis such an interesting way that Birchard uses writing, uses what we might thinkof as poems, as a way of thinking through writing and big ideas. “Augustine,rhetorician / that millennium and a half ago,” opens the piece “Homage to SarahRuden for Her Confessions,” “yet crazy as Beckett or Roberto Benigni /by virtue of the sedulousness and circularity // of his case, for want ofconfidence enough to match her / predecessors, drives our current ladytranslator to her cups.” This is Birchard, the well-read thinkingreader, the intellectual crafting poems out of reading notes, allowing thelyric to explore and examine. He writes of St. Augustine and The TroubadourClub in West Hollywood, Jack Kerouac and Saint Pancras, moving across incredibledistances through a short cluster of lines, stepping one foot ahead of another,keeping such detailed notes as he journeys. His poems blend study with journey,a wandering through language that explores alternate corners and catalogues of language.Dedicated to the late writer and critic Stan Dragland (1942-2022), Birchard’sbricolage, his own ‘journeying through bookland,’ one might say, is certainly comparableto Dragland’s work, but holds a different tenor, whether to Dragland’s work or thework of that other poet of bricolage (as Dragland wrote), Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall. “Exiting the cinder block shower next morning,” writes the poem “Butterflies& Turtle,” “not a / soul around, sunlit, stepping into his gotch, hisshoulders / and damp, bare back were suddenly a drift of Painted Ladies /alighting. // Guy fetches the camera a look of small-c concern.” There’s a densityto Birchard’s lines that hold a different kind of weight, perhaps, well beyondthe myriad of alternate reference, offering not just connecting reading andideas from across an alternate spectrum, but, veering occasionally into OldEnglish, one that holds a depth of language, and language meaning. As the poem “Company”writes, to close:

Smoked a rollie, usingthe tinplate ashtray. Sat, gazing round. Inside unaccustomed hush—out of thewind. Lit no woodstove. Book of Common Prayer in syllabics. Lit no kerosenelamp. Despite no roof overhead for weeks, we would not crash there. Nah.

Understood. At dusk,canoed back to make that heathen camp of ours in sandy, hallowed precinctsbetween Native graves and water.

Slept.

September 15, 2025

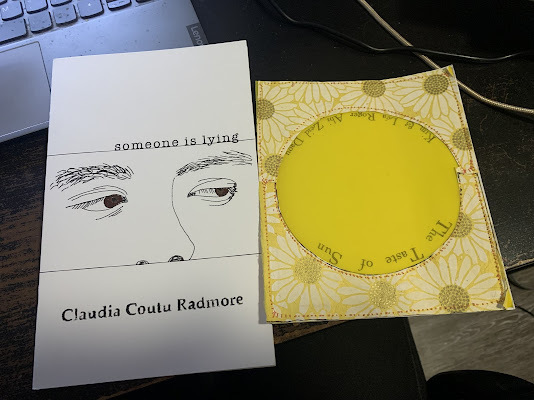

Ongoing notes: mid-September, 2025: Claudia Coutu Radmore + Kim and Léa Roger Abi Zeid Daou,

September,once more. Keep in mind:

The Factory Reading Series later this month

,featuring Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly, who is coming upfrom Texas, Michael Lithgow (who recently returned to Ottawa from half adecade in Edmonton) and Ottawa poet Ben Ladouceur (launching his new above/ground press chapbook). There are probably other updates to keep track ofas well, but it can be hard to recall everything. I say: check out www.bywords.ca

September,once more. Keep in mind:

The Factory Reading Series later this month

,featuring Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly, who is coming upfrom Texas, Michael Lithgow (who recently returned to Ottawa from half adecade in Edmonton) and Ottawa poet Ben Ladouceur (launching his new above/ground press chapbook). There are probably other updates to keep track ofas well, but it can be hard to recall everything. I say: check out www.bywords.ca Ottawa ON/Montreal QC: There are moments goingthrough Ottawa poet Claudia Coutu Radmore’s work that I’m occasionally surprisedby, whether the chapbook I produced through above/ground press, or this latesttitle, someone is lying (Montreal QC: Turret House Press, 2025); momentsI’m surprised her work isn’t better known than it is. Over the years, she’s hadchapbooks I’ve heard of through multiple presses, from Alfred Gustav Press to Apt.9 Press to Shoreline Press to Aeolus House Press to Catkin Press (and even garnered a bpNichol Chapbook Award), but full-length collections I rarely hear of, asthough she’s finding presses that are underselling the quality of her work. someoneis lying is a collection of poem-blocks, each piece set as single stanzaprose poems. Her poems offer a propulsion, one with precise angles and a delightfulattention to sound and collision. Listen to the opening of the poem “rawvocabulary and water,” for example, that jangles across the lyric: “from aplace beyond thought / where language originates in / where it resides proceduretakes / us halfway there after that w / need raw something feels each / thoughtcrumbles falls to pieces […]” Going through this work reminds me of Amanda Earl,another Ottawa poet doing stellar work, under the radar for long enough that itbegins to frustrate, wondering what certain editors might be thinking. A smarteditor at a small press, I should think, should be putting some of these chapbookstogether into a full-length collection.

CO: I’ve been moving through siblings Kim and Léa RogerAbi Zeid Daou’s collaboration, The Taste of Sun (Ethel Zine, 2025). Bothare PhD candidates and extensive creatives, with Kim also the author of thechapbook You are Memory, and I Archive (Cactus Press, 2023). TheTaste of Sun is a collection of four pieces of short prose with anepilogue. “My dad tells me to always remember the big picture—the point—whilealso adding my special touch.” opens the title piece. “This story is theperfect example of a flashbulb memory, which I learned about in an Introductionto Cognition class.” This is a book about family, about fathers; a heartfeltexploration and declaration of love and admiration. “My dad was always ahead oftime. He felt in his heart,” continues the title piece, “what is right,equitable, and just, long before the culture catches up. He taught me love isbeyond time.” These first-person pieces are curious in their approach to form,a blend of postcard fiction and first-person postcard memoir pieces. As well, Iwould be curious as to what the original prompt for such a project was, and ifthe two of them have been working on further of these. I could see afull-length collection of these, certainly.

Epilogue

On our walk

Dad hands me a daisy.

He holds my hand.

And closes his eyes.

In his warm palm

I feel close to my heart.

I asked what he thought,

As he looks at the blueof the sky.

He says thank you thankyou thank you.

September 14, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Rachel Blau DuPlessis is a poet,scholar, critic, and collagist. Her work includes the notable long poem Drafts(1986-2012), related historical-serial books such as

Daykeeping

(2023),and collage poems. Her latest is

The Complete Drafts

(2025), published by Coffee House Press. As a poet-critic she has written extensively on gender,modern and contemporary poetry, and both feminist and objectivist poetics, withspecial attention to H.D., Mina Loy, Lorine Niedecker, Barbara Guest, andGeorge Oppen.

Rachel Blau DuPlessis is a poet,scholar, critic, and collagist. Her work includes the notable long poem Drafts(1986-2012), related historical-serial books such as

Daykeeping

(2023),and collage poems. Her latest is

The Complete Drafts

(2025), published by Coffee House Press. As a poet-critic she has written extensively on gender,modern and contemporary poetry, and both feminist and objectivist poetics, withspecial attention to H.D., Mina Loy, Lorine Niedecker, Barbara Guest, andGeorge Oppen.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How doesit feel different?

My first book--done in a purist mode, tending tominimalism, a realist and a feminist-mythic and lyric mode --was writtenout of and inside of a generally Objectivist poetics that was at that momentbecoming resurgent. The book was Wells(New York: Montemora, 1980). One of fourbooks published as a “Supplement” to the periodical Montemora, edited byEliot Weinberger, the journal was characterized as elegant, intent,sophisticated in its literaryness. The editor sought European, Latin American, and United Statescontributors. This “Supplement” enterprise published Gustaf Sobin, MaryOppen’s poetry, a first work by Mark Kirschen, and myself. As a first book, it helped me declare I was awriter of poetry, come what may.

My most recent poetry book, Drafts,in two volumes (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2025) joins the modern andcontemporary long poem with its ode-ic and serial works in 114/115 cantos. Thelong work was written between 1986 and 2012, and became an excessive andwide-ranging work of poetic scope, cultural and historical commentary within anethical aesthetics. It has been my central poetic project from the moment itshowed its potential and was variously published (in many periodicals, by SaltPublishing in England, and one set by Wesleyan another by Chax Press in theU.S, during the generally twenty-five years during which I wrote it, before Iclosed it in 2012. Book-lengthselections have been translated into French, Italian, and Russian; andindividual works into Spanish, Portuguese , and German, with a book-length workexpected in Spanish. Canto-length works from this long poem have beenanthologized, often in collections including the words innovative, experimental,or conceptual in the titles. The projectled me to having something like an Objectivist-Projectivist poetics, committedto working out the contradictions of those position. The Complete Draftsas an unusually compelling and varied work of summation, explores topicspersonal, historical, and ethical with a striking array of genres and tonalvarieties. This poetry tries to manifest my well known interest in agender-subtle attitude and a lucidityand commitment to social poetics.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

As I child, I was readto a good deal from both poetry and fiction. As an adolescent, I picked up oneof Louis Untermeyer’s anthologies of modern poetry. Between A.A Milne andWallace Stevens, I was hooked.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

Well, from 1986, I had aparticular writing project. Because individual Drafts are about smallchapbook size, I will use those to answer that spirit of your question. Initialwriting (of one work, one Draft) may come quickly, yet I am generally a slow writer, very committed torevision, but also to the heuristic process of “making,” following where the poem might lead me, whileat the same time that I am both responding to it, and pushing and pulling it.The individual drafts of Drafts took a while to get their finalshape—whether that shape was an emotional trajectory, a rhythm of understanding,a serial examination, or an arousal toawe. The sound of the works in Drafts varies, because I have multiplegoals: such as reacting to events, collecting soundings in the news, pursuing an investigation, creating an experience. Many works of Draftsare like poetic-essays; many write to a horizon infused with my homage to andresistance to various modernisms. In a certain way these works as a whole takepoetry is a mode of expressive research into cultures (and sometimes specificmoments of histories).

4 - Where does a poem or work ofprose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I have done both. Once Ibegan my long poem in 1986 after I published my second book, called TabulaRosa (Elmwood, CT: Potes & Poets Press, 1987), shorter writing was incorporated into a given work of making one Draft.I did not habitually craft or work through the possible shape of a giveninsight into a shorter poem but let shorter materials fuse and connect intolonger forays. Once any single Draft started, materials often coagulatedor were written with that Draft in mind. I did use citations and currentrealities as part of what I found as material; I also have a commitment to theliterature of the past as I want to resee it.

After the whole longpoem was declared closed in 2012, subsequently I wrote several shorter books,some as collage work, but one project presented itself in several bookstogether beginning in work published in 2015. This set of short books emerged oneafter another as if in chapters about my particular experiences andobservations of the (now) twenty-first century, particularly uneasy ones in the changed, authoritarian United States. That six book group I now seeunder the rubric (title?) of Traces, with Days. This set of works are (in reverse chronological order)Daykeeping. Chicago: Selva Oscura, 2023; Poetic Realism. Buffalo:BlazeVOX, 2021; Late Work. NY: BlackSquare Editions, 2020; Around the Day in 80 Worlds. Buffalo: BlazeVOX, 2018; Daysand Works. Boise: Idaho: AhsahtaPress, 2017; and Graphic Novella.West Lima, Wisconsin: Xexoxial Editions, 2015. (the last one a college and text work.) I am currently completing this set of works, with a work conceived of asanother shorter book, called Blazes, in the mode of socio-aestheticsaturation in contemporary histories taking soundings in the sense of time that Ihave. .

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love giving readings,particularly of my longer poems, since they have a logic through the voice. Theauthor’s presence does not hold the poems together, but they can be dramatizedthrough my voice, with clear readings of the syntax as a certain’s poem’srhythmic disclosure.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

One concern got articulated in the first essay in my second book of gender and poetics : BlueStudios: Poetry and Its Cultural Work.(Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.) I think the work of modernity isincomplete for many people (because of intolerance, compromised literacy,badly-adjudicated justice, uneven distribution, despoiling economies) and thatliterary writing now has a responsibility to point out that incomplete modernity(given some of its promises and even premises). Hence I say that with my poetry, I’m trying to begin realmodernisms all over again. In the essay,I say I want to approach “power and hegemony” with (among others) the tools ofa “feminism of critique,” that is, with critical insights, empathy, claims ofequity, and resistance where necessary. With the critical vocabulary and itssources in multiple groups, I have felt that a “re-vision” and rectification ofour global disasters would necessitatethe multiple, forceful, and polyvocal invention of a new culture” –might we sayan inclusive, lively, and fairer one. At the same time, I do not for myselfdesire a hectoring or tendentious voice, although well-deployed polemic can havegreat virtues. The poetry I write does not pretend “answers,” it wants to seeand register the world we know and that we want to question. I am moreinterested in “it” (the world and its languages and situations) than I am in“I”myself alone as an single particular,expressing feelings and pasts without any context or sense of what historiesformed the self (and selves) of my poems.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

Aside from my comments above, Iappreciate in many ways the implications of “a poetics of critique.” With thatanalytic-poetic acumen, I’d want sincerity, a poetry of observed accuracy,language-intelligence, and of necessity.. I also deeply admire Joan Retallack’s phrase and sense of purpose in“the poethical wager.” I also do not think poetry need be solemn, but ratherwitty and playful, filled with the joys and twists of languages and dictions, becauseit is serious.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I have learned a good deal from good suggestions and a critical eye fromothers on my work.Those would be most often from reader’s reports througheditors of my prose. I have had almost no poetry editors, but I was lucky enough to have George Oppen’sintrasigent eye on my very early work.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

When I had postponedwriting too many times. I would say to others,”don’t postpone. If you need todo a work now, do it now!! Things do not keep indefinitely, and you can losetheir impetus.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toessays)? What do you see as the appeal?

Nothing is”easy”; youare working in different zones of address. But I have definitely done both withpleasure. For ease of identification for others, I sometimes call my poems “poem-essays,” becauseof their tonal variety (heteroglossia), and topical change-ups (collage). Aperson might choose to write, or somehow be chosen by these genres. You putyour all into either, but a slightly different mix of that “all.” Because I havedone both, I’d also distinguish them from scholarly essays and books (which I havealso written with serious interest );this is both an intriguing question and a longer term query—more than I cancomment on here. First off, a work of scholarship for me is research-based atsome point, might involve pertinent close readings that are essential to achapter’s argument, and, without pretending you are the only decent critic inthe world , such a genre presents a serious and efficient argument, often butnot crucially to a community of professionals of which you are part. That setof commitments has degrees of difference from both essay and poetry.

Both essays and poetry differ from thissomewhat idealized model of scholarship in my field (poetry/literature). Inboth you have to be called in a different way to write either, often in both bya very compelled sense of listeners, a community into which you are talking,and to a self as writing voice that compells you to say just this. Riskis paramount. Compulsion and desire distinguish these modes. For scholarship,one has keen external standards that are mostly in play. For essays and poetry,there is a keen and irreducable sense of internal necessity that makes youstick to. with, and by a given work at a different level of loyalty to yourvision of it. The degree of sheer drivenness and the deep need to work on theshape and tonalities of poems and essays are certainly part of the appeal forme.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one?

In my professional life,it was quite hard for me to compartmentalize. A writing routine has been what Icould manage in the time available.That seems to be true even after retirement.

How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wish I had a typical scheme I could give you. Days differ drasticallythroughout one’s life.

I was a professor in auniversity. My teaching schedule changed semester to semester. I graded studentwork as part of my job. I saw students, often accounting for their schedules. Iprepared (or over-prepared) my classes (literature, creative writing women’sstudies, “Western humanities”) and had original syllabi to draw up sometimesseveral time a year. I had profession responsibilities inside and outside theuniversity (editorial, administrative).. Schematizing all this, plus beingmarried and a mother—and a person, and a poet—I kind of wonder how everythingdid happen. My only answer is I didn’twatch TV.

I will say one thing, I used to revise Drafts on my commute bytrain. The half hour or forty minutes meant I would whip out a current poem andread it and listen to it and revise it during that private time in a publicspace.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Patience, doingsomething else, and giving the stalled work a week or a month off; and oftenreading something-- a poem in a different language than English, or a writeropposite from my mode, or a work reminding me of what I am trying .

13 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Of my home? Of the home Igrew up in? Mine—spices I like to cook with; of my childhood home, maybe teaand buttered toast.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

All on your list—arts and sciences—(science and math ideas through NY Times science pages andgeneral-audience books ) All , definitely, consistently, rigorouslyvalued and pursued during all my active years (in concerts, museum and gallery attendance, some friends in thosefields). I sometimes understand my experience making my long pom as creating a“sculptual” shaping. Big chunks of matter are made by me brought into, meldedinto one item to experience. I therefore value the different-from-literaryinsights of other forms and the shaping each accomplishes to reach their total,completed shapes. To answer thisquestion, I would also include much foreign travel (much more than most peopleI know) and even the chance toexperience living in places other than my actual citizenship for months at atime.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

George Oppen, Robin Blaser, Virginia Woolf, and many contemporaries as serious companionswith true writing grit and sometimes with large-scale projects. Their names vary over lifetimes ofreading and teaching.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Have had piano lessonsor cello lesson early enough in my life so I could have played an instrumentdecently. Have the stamina to take a very big hike. You’ve cast the question as“what do you still want to do.” That’s not where I am temporally.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?

Medical doctor.

Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

Since I have had a negligible income from my poetry, essays, reviews,readings and appearances, reader’s reports for presses, etc. . ., I always hadto have an occupation in another profession. What i somehow choose was my adefinite interest, and that is “what I did” (I didn’t “end up” doing it—Iwanted to do it!) I picked a profession near to writer, incorporatingwriting (that is, being a literatureprofessor), but it was a more regularly structured profession than onlywriting. Hence I could count on its income and benefits along with otherinstitutional advantages, like good library access and some veryintriguing.students and colleagues.I don’t think I could have survived themarket as a high-end or free-lance journalist, or as an editor Plus, I thoughtthat women should choose (if possible)to have an income they called their own, one that a person could actually liveon, so tht marriage was a choice, not done for access to an income.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

That’s the mode mycreativity took, and that path was more clearly available and valued thanothers to people who had an influence on me; writing also appealed to my own curiosity. I might also answer with Robert Creeley’ssummary remark, “I’m driven to write poems.”

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Not sure I can formulatea response to this. I like lots of creative works for what they say, how they sayit, and what they give me.

20 - What are you currently working on?)

The book called Blazes that I mentioned already. And f I am lucky,a book of essays in poetics and poetry called Difficult Bliss. Which isexactly what this literary and scholarly career has been.

September 13, 2025

Ottawa book launch : the book of sentences, (with Stephanie Bolster + Zane Koss,

the book of sentences

(University of Calgary Press, 2025): now available / order through your favourite bookstore or, in Canada, through the press directly; elsewhere, order through bookshop.org / if you are an above/ground press subscriber, simply toss me $20 and I'll add a copy to your next delivery / Ottawa launch: October 18 via Plan 99 Reading Series, 5pm, at The Manx Pub w/ Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster (new Palimpsest Press poetry title) + Guelph poet Zane Koss (recent Invisible Publishing poetry title) / myself, new poetry title and above/ground press will also be at: 2025 Toronto International Festival of Authors Small Press Market, November 1st + Meet the Presses Indie Literary Market, November 2nd (Toronto) / the ottawa small press book fair, November 22, 2025 / and can you believe the book has already had a review? / be sure to check out the essay I wrote on the collection over at my substack,

the book of sentences

(University of Calgary Press, 2025): now available / order through your favourite bookstore or, in Canada, through the press directly; elsewhere, order through bookshop.org / if you are an above/ground press subscriber, simply toss me $20 and I'll add a copy to your next delivery / Ottawa launch: October 18 via Plan 99 Reading Series, 5pm, at The Manx Pub w/ Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster (new Palimpsest Press poetry title) + Guelph poet Zane Koss (recent Invisible Publishing poetry title) / myself, new poetry title and above/ground press will also be at: 2025 Toronto International Festival of Authors Small Press Market, November 1st + Meet the Presses Indie Literary Market, November 2nd (Toronto) / the ottawa small press book fair, November 22, 2025 / and can you believe the book has already had a review? / be sure to check out the essay I wrote on the collection over at my substack,September 12, 2025

Isabella Wang, November, November

tears salt the goodfabric

of her poppy scarf there is slow quiet

mapped ribbondevelopments

of our black ice

future winters

everywhere there is the mildness

of unanticipatedclemencies

showing us care

this salt remnant of her leaving

melting the ground keeps us safe

while you are driving

for miles the heart pulses

distances the mind cannotimagine

to cross in a lifetime (“PASSAGE2: NOVEMBER 2021”)

Inthe “Afterword” to her second full-length collection,

November, November

(Gibsons BC:Nightwood Editions, 2025), a follow-up to

Pebble Swing

(NightwoodEditions, 2021) [see my review of such here], Vancouver poet Isabella Wang writes of her ongoing engagementwith the work of the late Salt Spring Island poet Phyllis Webb (1927-2021). Webbis a poet originally introduced to Wang through Vancouver poet Stephen Collis [see my review of Collis’ critical volume on Webb here], and Wang writes of timespent in the Special Collections vault at Simon Fraser University, listening toarchived reel-to-reel cassettes of Webb reading, and conversations with Collis onWebb’s work, including discovering a previously uncollected poem in therecordings. She writes of grief, and of visiting “Syowt’s Bowl,” the ancientstone shape set in Salt Spring Island’s Ganges Harbour, an artifact that enteredCanadian poetry through Webb’s Wilson’s Bowl (Toronto ON: Coach HousePress, 1980), the title poem composed as her memorial for the Canadianarchaeologist, cultural anthropologist and curator Wilson Duff (1925-1976). “whyam i crying,” Wang writes, as part of the extended lyric “PASSAGE 2,” “grievinga person i’ve never met [.]” As she offers as part of her afterword: “Shared griefis like a weighted blanket. It is also a collaboration in the way that the sixof us shared stories by the bowl and the moment we started reading our favouritePhyllis poems, Salt Spring suddenly started hailing.”

Inthe “Afterword” to her second full-length collection,

November, November

(Gibsons BC:Nightwood Editions, 2025), a follow-up to

Pebble Swing

(NightwoodEditions, 2021) [see my review of such here], Vancouver poet Isabella Wang writes of her ongoing engagementwith the work of the late Salt Spring Island poet Phyllis Webb (1927-2021). Webbis a poet originally introduced to Wang through Vancouver poet Stephen Collis [see my review of Collis’ critical volume on Webb here], and Wang writes of timespent in the Special Collections vault at Simon Fraser University, listening toarchived reel-to-reel cassettes of Webb reading, and conversations with Collis onWebb’s work, including discovering a previously uncollected poem in therecordings. She writes of grief, and of visiting “Syowt’s Bowl,” the ancientstone shape set in Salt Spring Island’s Ganges Harbour, an artifact that enteredCanadian poetry through Webb’s Wilson’s Bowl (Toronto ON: Coach HousePress, 1980), the title poem composed as her memorial for the Canadianarchaeologist, cultural anthropologist and curator Wilson Duff (1925-1976). “whyam i crying,” Wang writes, as part of the extended lyric “PASSAGE 2,” “grievinga person i’ve never met [.]” As she offers as part of her afterword: “Shared griefis like a weighted blanket. It is also a collaboration in the way that the sixof us shared stories by the bowl and the moment we started reading our favouritePhyllis poems, Salt Spring suddenly started hailing.”Thepoems that make up Wang’s November, November are composed with such deep anddelicate precision; as a calendar of meditative space around grief, homage,illness and recovery. “parts of this body are negative / parts of this body arediffusely positive,” she writes, as part of the poem “THE BODY IS” in the thirdsection of the book, “this body is whole / this body goes by one given name /except the parts of it removed [.]” Structured in five sections—“CONSTELLATIONS:NOVEMBER 2020,” “PASSAGE 2: NOVEMBER 2021,” “PASSAGE 3: DECEMBER 2021,” “PASSAGE4: NOVEMBER 2022” and “PASSAGE 5: NOVEMBER 2024”—the third and fifth of whichare composed of shorter, self-contained pieces, there is something really compellingin the way Wang offers this collection as a deep engagement with Webb and herwork through a particular period, through Webb’s death and Wang’s cancerdiagnosis, treatment and recovery. Wang’s poems allow for influence andengagement with Webb’s work without overtaking Wang’s own lyric, offering afoundation for possibility across a delicate, open-hearted and deeply mature lyric.Webb’s work might have been the engine, but Wang is clearly at the wheel, as thepoem “PRAYER ON AN OPERATING TABLE” reads, to close:

love effortlesschildhoods : branches of moss : their own little tree :

love so many beams ofasphalt : the tongue becoming a highway : love

medicines : options arenone : Deer Lake : hope country of nowhere :

Wanghas become quite adept at pulling at the small moment, allowing the line toextend across a great distance, offering her own take on the long poem throughsequences, sections, clusters of poems and, eventually, this book-length,meditative suite, all of which is wrapped around attention, and adeeply-attuned ear. Listen to the opening untitled poem of the second section, “PASSAGE2: NOVEMBER 2021,” a section subtitled “for Phyllis and the Loving Crew”;the piece is dated “November 11,” the same day Webb died:

white pines frosted window

won’t let in images ofmorning

but sunlight until they melt

bus loop bus drove by me

me stop-signed at anothercurb

ice crystals writesquiggly lines

where previousscratches on glass

feel everything

talked to Phyllis

yesterday said we both

enjoyed the company

of your friendship

her your anchor

your purpose for escape

the city your work

they are your two ends

pulling on your Tsawwassen heart

keeping you steady

youngest of seven siblings

still feel everything

September 11, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Patty Nash

Patty Nash's first book,

Walden Pond

, was published with Thirdhand Books in August 2024. Her poems haveappeared in The Paris Review, the Washington Square Review, Annulet,and elsewhere. Website: patty-nash.com.

Patty Nash's first book,

Walden Pond

, was published with Thirdhand Books in August 2024. Her poems haveappeared in The Paris Review, the Washington Square Review, Annulet,and elsewhere. Website: patty-nash.com. 1 - How did yourfirst book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

Walden Pond is my first published book, but it’s mythird or fourth manuscript, depending on how I’m counting. My earliestmanuscripts consisted of single poems that I had more or less haphazardlystapled together, the later ones were more interested in specific topics. With WP, I was narrowly interested in a broadconstellation: nationhood, institutions of religion and language, the exchangeof capital, how these make us identify and relate in codified ways. I wasparticularly interested in national narratives and figures, like Martin Luther,whose high German translation of the Bible paved the way for Germany to thinkof itself as a nation. I live in Germany, and for about two years, I wouldintentionally seek out sightseeing trips or site-specific “research” that madesense for the book. This was different to my writing process before, whichentailed me sort of waiting for things to happen. I also started working onlonger poems and series in this book, many of which didn’t even make it intothe final manuscript. It was originally over 200 pages long…

2 - How did you cometo poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poems because I thought I didn’t have toknow the rules. What others called “good” poems seemed to me totally random atthe time (I was a teenager), at least compared to novels, which had (to me)clearer markers of success or failure. I’m not sure I still agree with myearlier self, but I still feel more freedom writing poems than I do in othergenres.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My tendency is to struggle for a long time around a singleconceit, like for months. Then, after some break in routine, everything coheresand suddenly starts working, or I find a form that’s so much fun I can’t stopwringing it out. Still, most of my writing is a slog. My early drafts are quitemessy and often quite different from their final versions.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Since writing WP, Ihave become convinced of long poems. The longer the better! I like working on a“book” from the very beginning, but the “book” often splinters off into otheriterations or siblings… I enjoy pursuing a question without having fullyarticulated it yet, because then everything I do has a poem underneath it. Thatsounds instrumentalizing, but it really isn’t – my poems often surprise me inhow they confound my initial experience of something, be it a wedding or agroup excursion into the woods or a doctor’s appointment.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I love public readings. The poems that are best suited forpublic readings aren’t always the ones that make it into journals, sadly –which is why I like reading them, looking the audience in the eye. That’s mybig thing: eye contact.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

This is a big question… I’m not sure I can answercompletely. More recently, I’m thinking about the forces that allow or impel meto think of myself as a subject in the first place, someone with descriptive ordenotative authority. Isn’t it curious – the fact that my experience can betrusted, at least in certain contexts? Why is that? If these are currentquestions, I think they’re also perennial questions writers ask – aboutrelations, about power, about systems, about death, but also how we make senseof them, how we emote in them. For me, the central instrument of thatsensemaking is my “I,” but it’s so strange and arbitrary that I have come tothink of myself in this way, and not some other pronoun or grammatical unit ofaffiliation. It seems quite constructed, but also conflated with my whiteness,my German-Americanness. I also see this responsibility to look at thatinstrument as an instrument of power. If there were a question I’m trying toanswer with my work, it would be “What is going on?” And then: “What happened?”And then: “What’s that?” Of course, the central question of “Who am I”, whichis quite common in lyric poetry, attends as well… I don’t want to take anythingfor granted, and I don’t want to detect these big questions in monuments or grandhistorical gestures, but like, when I’m eating breakfast, for example, orwatering my houseplants.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think good writers make everything strange, or at leastcall attention to how “normalcy” is a motivated aesthetic device. To be moresentimental: it’s bizarre that we are on this earth, and equally bizarre thatthe world is the way it is! Isn’t it? I think writers should be as various asthey want to be. Broadly speaking, I am glad that there are lots of differentkinds of writers and texts.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s absolutely essential. My work would be terrible withoutthe input of readers, friends, and editors. The editors at Thirdhand Books(Lindsey Webb and Kylan Rice) absolutely made my first manuscript better than Icould have alone.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I am frequently told that taking a break will make mywriting better. It’s true, but I don’t always follow the advice, and insteadchurn out dozens of middling poems until I become too frustrated with myself togo on. Then I take a break and things are indeed easier and more exciting.

10 - How easy has itbeen for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose/reviews)? What doyou see as the appeal?

I’m currently writing my dissertation, and it’s frighteninghow similar that process feels to me compared to writing poems, though on thesurface the process would seem so opposed. I have the same associativecompositional style and many similar formal questions when I’m writing thedissertation, i.e., a vague question that I can only articulate when seeing itwritten. I also research a lot, though it’s questionable how much of thatresearch makes it into the poems themselves. And in both I force myself to slogthrough even when the productivity has long since waned. Unfortunately, thecreative energy I bring to the dissertation drains the poems, so I have to becareful about how much I’m working on each.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

Sometimes, I do a daily writing practice, often sharing thepoems in a poem-a-day doc started by a friend, poet Emily Bark Brown. Then Ihave months when I try to sit down twice a week to look at my poems or write anew one. Typically, it’s about four or five times a week, however. Beforestarting the PhD, writing was like popping a zit, a compulsion, because it feltso necessary compared to my day job. Now I have to be more intentional aboutcarving out time and, more importantly, interest. I typically write in themornings, after I get back from the gym and before I sit down for the “realwork.” My best poems are written, however, when I haven’t scheduled writing andactually should be doing something else.

12 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

With the exception of Wikipedia and select Youtube videos,the internet is horrible for my writing. When I feel stalled, I do something I(ideally) feel ambivalent about, like going to a museum or forcing myself intoan uncomfortable social interaction. I like churning that ambivalence into apoem. The resulting poem is usually not very good but it is a good distraction.If I have the means, I skip town – breaks in routine are fantastic for mywriting and usually the best way to start something new. I honestly think thebest thing for my writing, however, is not writing. I have this compulsion toalways be writing and I think it leads to bad poems.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Douglas firs! Gasoline.

14 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I do like opera a lot, but I’m not sure it influences mywork. Same goes for movies. I think fantasy RPGs have found their way into mypoems, surprisingly – I like this idea of suspended contingency, of beingsomeone else and trying things out, erasing them, moving around. I played Morrowind while writing Walden Pond. My boyfriend introduced meto it and I spent hundreds of hours there…I hadn’t really played any games before, besides The Sims.

15 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

This is so hard, because there are so many. But I do wish Icould write with the same unabashed ambition as Thomas Mann and Leo Tolstoy – Isense this desire to combine forms, fiction and history. I love reading both oftheir works, though I have to say I don’t always love the books themselves, ifthat makes sense. The books are so determined and controlled, and yet withhistorical distance it’s also possible to make diagnoses from afar – Magic Mountain is to me a book aboutthis deadly idea of Europe as much as it is about sickness, time, andmodernity.

16 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

I really would like to write a libretto. I have started afew but don’t have a composer yet, sadly.

17 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I honestly like being a poet, but I wish I had picked uptraining for a job that would allow me to earn a living wage without workingmore than 20 hours a week. Does that exist? I really love writing, but I hatehaving to earn money and worry about that.

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I wish I knew! I enjoyed writing and it was easy to dologistically (I didn’t need extra equipment, or anyone supporting me). I thinkthat was the main reason.

19 - What was thelast great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky and this timetranslated by Michael R. Katz. The last film I enjoyed was Dahomey, directed by Mati Diop.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I am pregnant and, if all goes well, my baby is due in 1.5weeks. Pregnancy is a very strange experience and has, rather predictably,consumed my writing. When I found out I was pregnant, I started a book called The Experiment, which is composed ofvarious little sections, but also inspired by a pregnancy experiment I’m takingpart in at the Berlin Philharmonic. (You’ll have to read the book to learnmore.) But the bigger, more loomingproject is another one. For the past three years, I’ve been working on abook-length poem about historical Hanses, titled HANS – “Hans” being the diminutive of Johannes in German, andrelated to names John, Ian, Sean, Giovanni, Jean, Yahya, Johanna, Hannah, Ivan,Anna, Nancy, and many more. The book is interested in historical reproductionand repetition, which occurs through the same name in different persons. Thereare a lot of historical Hanses that could make it into the book. The issue isactually keeping the number down…

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 10, 2025

Saretta Morgan, Alt-Nature

Low-basin flora. Verdant.

Inching vertebral ache.

A warm anatomy to feelthreatened:

endangered by;

thick-muscled and in danger of. Iridescentover.

And in the tissue between floodplains and the officer’sscience.

And the quiet between andwant for shade, the hooded eyes and fluid

body.

Gentle body for whom I liedown. (“First”)

I’dbeen eager to see further from Brooklyn poet Saretta Morgan for some time,after discovering her work through her chapbook

room for a counter interior

(Brooklyn NY: portable press @ yo-yo labs, 2017) [see my review of such here], finallyable to get my hands on her debut full-length collection,

Alt-Nature

(MinneapolisMN: Coffee House Press, 2024). Through eighteen extended lyrics, Morgan offersan ongoing declaration, almost a sequence, articulating an unfolding betweenpages, between poems, presented as a lyric of inquiry. There is such awonderful, underlying sense of music that moves through her lines. “We had verygood reason to believe that the authorities were lying.” the opening poem, “First,”begins. “Were / not omnipresent. Which meant the authorities would at somemoment / arrive.” Further on in the collection, offering: “In this foreign citythe population is small. Very few spend money on / beads & pigeon feathers.// She takes care of a man. It is the same job her mother does.”

I’dbeen eager to see further from Brooklyn poet Saretta Morgan for some time,after discovering her work through her chapbook

room for a counter interior

(Brooklyn NY: portable press @ yo-yo labs, 2017) [see my review of such here], finallyable to get my hands on her debut full-length collection,

Alt-Nature

(MinneapolisMN: Coffee House Press, 2024). Through eighteen extended lyrics, Morgan offersan ongoing declaration, almost a sequence, articulating an unfolding betweenpages, between poems, presented as a lyric of inquiry. There is such awonderful, underlying sense of music that moves through her lines. “We had verygood reason to believe that the authorities were lying.” the opening poem, “First,”begins. “Were / not omnipresent. Which meant the authorities would at somemoment / arrive.” Further on in the collection, offering: “In this foreign citythe population is small. Very few spend money on / beads & pigeon feathers.// She takes care of a man. It is the same job her mother does.”ThroughAlt-Nature, Morgan offers poems that bleed into each other, with blurredyet delineated boundaries; a suite of clusters, if you will. She writes ofnatural elements and of human nature, articulating elements of landscape andecology and the extensions and limitations of human choice, human reaction. Thereis such attention to detail through these lyrics, such a delicate and devoted kindness.Alt-Nature is a book one could almost dip in and out of, writing familyand human interaction, borders and boundaries, and how we relate, andinterrelate. As she writes: “Holes, like decades. Advancing with acute, unannouncedrelease // the lip of geographic faults.” As announced by the title, there’s anecological thread that runs through this collection, this book-length poemsuite, one that echoes concurrent conversations by poets including Orchid Tierney, or Tasnuva Hayden [see my review of her latest here]; a thread heldjust under the surface of certain poems, akin to tendrils, interconnectingsections of her ongoing lyric. Hers is an astute, ecological lyric, a series ofnotations on travel, writing out the nuance into a declared horizon. The openingsection of “For Francees, because she said, One day maybe you’ll write a poemabout us,” for example, reads: “For a long time she could make a living weavingdream catchers from / paper heads and wild bird feathers in her birthplace,Agua Prieta. // She could call from detention to remind me of my anniversary. Of/ my wife’s birthday, weeks before the fact. I’d say, Whose birthday is it / coming?But she was never wrong. // In that life she said, I must be patient with mydaughter. // Offered anything she would say. I want my mom.” Or, further in thecollection, as she writes:

The dominant orientation isbased in devotion. The geography, devoted,

disfigures each wrist.

Veins negotiate a well-marbled music of territory.

Militant roots open tothe half-drawn beauty of corridors. Where the

governing image brancheswith light.

September 9, 2025

Steffi Tad-y, Notes from the Ward

You Who The Earth Was For

After Jean Valentine

You fleeing war, carryinga rooster with your shaky hand.

You trained to pummel,never the first to wince or flinch.

You who plant theirsadness into dirt.

You whose questions haveno gentle answers.

You who cook too close tothe stove.

You at the table, missingthe one.

You whose loss comes withwordlessness.

You beside the rubble,out to build again.

You in the backseat beingloved.

You running towardswater.

Thesecond full-length collection by Manila, Phillipines-born Vancouver-based poet Steffi Tad-y, following

From the Shoreline

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022)[see my review of such here] is

Notes from the Ward

(Gordon Hill Press,2025), a book composed, the back cover offers, as a “collection of poetryexploring bipolar disorder and psychotic break through lived experience and apoet’s eye.” Through sharp, first-person lyrics, Tad-y offers a variation onthe declarative point-form, providing a precision across difficult subjectmatter, writing phrases that accumulate across her lyric stretches. Thefoundation of Tad-y’s lyric clarity holds each line in place, even through descriptionsof untethering; a lyric one might hold on to, for dear life. In the poem “Mangroves,”as she writes: “Back in the truck with Dad & Uncle. I tell them how thetrees are / skin & sanctuary to the coast, protection against the onslaught/ of storms. // My father places his hand on the headrest of my uncle in the /driver seat and says, Families can be mangroves too.”

Thesecond full-length collection by Manila, Phillipines-born Vancouver-based poet Steffi Tad-y, following

From the Shoreline

(Guelph ON: Gordon Hill Press, 2022)[see my review of such here] is

Notes from the Ward

(Gordon Hill Press,2025), a book composed, the back cover offers, as a “collection of poetryexploring bipolar disorder and psychotic break through lived experience and apoet’s eye.” Through sharp, first-person lyrics, Tad-y offers a variation onthe declarative point-form, providing a precision across difficult subjectmatter, writing phrases that accumulate across her lyric stretches. Thefoundation of Tad-y’s lyric clarity holds each line in place, even through descriptionsof untethering; a lyric one might hold on to, for dear life. In the poem “Mangroves,”as she writes: “Back in the truck with Dad & Uncle. I tell them how thetrees are / skin & sanctuary to the coast, protection against the onslaught/ of storms. // My father places his hand on the headrest of my uncle in the /driver seat and says, Families can be mangroves too.” Whatholds the collection together as a coherent unit are the dozen numbered titlepoems throughout, gathering her thoughts in a space that blends both attemptingto heal and the challenges of existing in such a physical and mental space. As “Notesfrom the Ward #3,” a poem subtitled “After Ocean Vuong’s ‘Reasons forStaying’,” begins: “Think of the next thirty years, mother asked. // The magnoliatree at Oben Street still a pleasant memory. // Of the book, black with deepblue letters, music despite my lack / of understanding.” Tad-y offers lyricdeclarations underneath titles set as umbrellas, suggesting and directing andhinting at the context of lines that blend direct with the indirect; her poemsprovide a tone of attempting clarity through these poems, these ward-notes,seeking both as documentary and process. While working through Tad-y’s poems, I’mreminded how, in his novel Why Must a Black Writer Write About Sex? (translatedby David Homel; Toronto ON: Coach House Press, 1994), Dany Laferrière wrotethat he composed his first novel—referencing his debut, How to Make Love to a Negro (Without Getting Tired) (translated by David Homel; Coach HousePress, 1987)—“to save his life.” Or, as the poem “Hold on,” set near the end ofthis new collection, begins:

Everyone has something.

This is yours.