Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 9

July 30, 2025

Éireann Lorsung, Pattern-book

BRAMBLE CUTTING

Five-petaled, milk-white—say

thin as milk, aswholesome:

pithy centres turn topulp

in July. All year, canes

overrun garden paths,empty

lots. Bramble is a lesson

in plant economy.

—In another life

I could be bramble: or

rain on bush shelterroofs,

the taste of saltstepping

off a train. An estuary

in the morning under fog

not to be seen through.

Bunkers overgrown withthicket.

These last times I was agirl.

Itwas very good to spend a few days with

Pattern-book

(Manchester UK: Carcanet,2025), the latest full-length collection by American poet (recently returned afterspending a few years living and teaching in Ireland) Éireann Lorsung,especially days prior to hearing her read from the collection [see my notes onour shared Dublin reading here]. Slated to take over editing of

South Dakota Review

this fall, Lorsung is the author of three prior full-length collections—

Musicfor Landing Planes By

(Minneapolis MN: Milkweed Editions, 2007),

Her book: poems

(Milkweed, 2013) and

The Century

(Milkweed, 2020),winner of the Maine Literary Award in Poetry—with a further title, PinkTheory! forthcoming with Milkweed Editions in 2026. The poems in Pattern-bookprovide a curious sequence of crisp narratives, each of which begin with aspark, a speck, that broadens as each poem carefully and deliberately unfolds. “Nowclouds pass / the sun, for a moment, and are gone,” she writes at the centre ofthe poem “DESIDERATA,” a poem subtitled with the quotation “reverie alonewill do (Dickenson),” “and everything retains / its gold, and all / we needis in this / meadow, its / umbels and its star- / shaped yellow heads of ragwort/ and, floating off somewhere, / a train’s sound.” Her line-breaks often hold apause, a held breath, through quatrains, couplets, sonnets and other form-shapes,and even seem to employ elements of the English-language ghazal, offering leapsof narrative between lines that allow for wider narrative gaps.

Itwas very good to spend a few days with

Pattern-book

(Manchester UK: Carcanet,2025), the latest full-length collection by American poet (recently returned afterspending a few years living and teaching in Ireland) Éireann Lorsung,especially days prior to hearing her read from the collection [see my notes onour shared Dublin reading here]. Slated to take over editing of

South Dakota Review

this fall, Lorsung is the author of three prior full-length collections—

Musicfor Landing Planes By

(Minneapolis MN: Milkweed Editions, 2007),

Her book: poems

(Milkweed, 2013) and

The Century

(Milkweed, 2020),winner of the Maine Literary Award in Poetry—with a further title, PinkTheory! forthcoming with Milkweed Editions in 2026. The poems in Pattern-bookprovide a curious sequence of crisp narratives, each of which begin with aspark, a speck, that broadens as each poem carefully and deliberately unfolds. “Nowclouds pass / the sun, for a moment, and are gone,” she writes at the centre ofthe poem “DESIDERATA,” a poem subtitled with the quotation “reverie alonewill do (Dickenson),” “and everything retains / its gold, and all / we needis in this / meadow, its / umbels and its star- / shaped yellow heads of ragwort/ and, floating off somewhere, / a train’s sound.” Her line-breaks often hold apause, a held breath, through quatrains, couplets, sonnets and other form-shapes,and even seem to employ elements of the English-language ghazal, offering leapsof narrative between lines that allow for wider narrative gaps.

POSTCARD TO SHANA WITHPHOTGRAPH OF

FLORALIËN GHENT, 1913

Everyone I know is losingcities this year. Yesterday

I heard the cuckoo forthe first time, which means

it’s spring. Since I lastwrote, teams of gardeners

have gone to work allover Ghent, secateurs catching

light; in days theneighbourhood was transformed.

Gardenias, azaleas. A youngman stood near a shallow

pool breaking flowersfrom a peach branch and setting

them in water. Industry unrecognizablein its new

horticultural clothes. Youknow I have been tending

to an orchard of my own:peach tree and cherry

trees; apples; plum. The lawnis stippled bright with daffodils.

I thought, if I leavehim I will lose the garden

I made. I thought, Ican make another garden anytime.

Nevertheless (the lambsare playing now—again!), I stayed.

Throughoutthe collection, Lorsung riffs off lines and poems by such as Emily Dickinson,Gerard Manley Hopkins and Gwendolyn Brooks, John Berryman, Walt Whitman andEdna St Vincent Millay, among others, in her exploration of rhythmic thoughtacross the American Midwest and English Midlands, of the details anddifferences of geographic, cultural and domestic space. As the poem “LINNAEANSYSTEM” begins: “You know the rose is in five pieces. / You know the centre ofthe split apple copies it. / The skin of a nectarine, a pear, an almond, apeach makes my mouth burn.” There is something of Lorsung’s careful precisions,her narrative care that occasionally attempts to shake lose from itself, writinggardens and photographs and paintings and swans, that I find slightlyreminiscent of the work of Montreal poet Stephanie Bolster [see my short review of her most recent book here]. “I have a sense of history as if it were a picture:,”she writes, near the end of the poem “FEBRUARY MOTHER,” “here the donkey/ struggles uphill under its load of sticks, and here the pigeons //pick at grain. The fire never burns out. No one dies. The world / is alwaysthere, under the tympanum’s perfect sky. The point // of the painted world isthe blue of our world that lives / and dies. There is no other point but that.”

July 29, 2025

Hannah Brooks-Motl, Ultraviolet of the Genuine

POVERTY MOUNTAIN

a reference qua the epics

an evening

“coming out of my wormhole”

into the hollow

what’s good for thescurfpea

to be like the soul

crisply transpicuous

Notlong ago, I discovered, thanks to the chapbook Poem Staple Collage / forJonathan Rajewski / & Other Poem (Chicago IL: The Year, 2024) [see my review of such here], the incredible work of western Massachusetts poet HannahBrooks-Motl. Her fourth full-length title, and the first of her full-lengths I’veseen, following

The New Years

(Rescue Press, 2014),

M

(The SongCave, 2015) and

Earth

(The Song Cave, 2019), is

Ultraviolet of the Genuine

(The Song Cave, 2025), a book self-described as “an expansive record of time andthought, weaving together philosophy, science, theology, dreams, grief,literary theory, criticism, history, and ideas of utopia—becoming a book thatcontinuously surprises and is nearly impossible to categorize.” “If you thinkwords are made of poems,” she writes, as part of the extended fragment-sequencepoem “POET DILEMMA,” “I mean poems made of words / As we’re taught // I know plentyof words / Though I come from the provinces / Where the earth is filled withviolence [.]” There’s something remarkable in the swoop and the rush of Brooks-Motl’slyrics, a simultaneous sense of compression and expansion, one that allows lessa narrative trajectory than a sequence of thought-clusters that interconnectacross every other moment and cluster across such wider expanse. “In Exeter,England one June or July,” she writes, to open the poem “EXETER,” “we slept onthe floor / Rhetorically, sentimentally—I bring / this up— / not to interpretroses or be watched / by the deer on Pulpit Hill Rd. / Yes it is strange / Ineveryone there is a certain no one / The garden, the blankets the poem / should be a world, a real world/ Savanging the carved stone / Ymaginator / and the demi-angels now / justshapeless blobs [.]”

Notlong ago, I discovered, thanks to the chapbook Poem Staple Collage / forJonathan Rajewski / & Other Poem (Chicago IL: The Year, 2024) [see my review of such here], the incredible work of western Massachusetts poet HannahBrooks-Motl. Her fourth full-length title, and the first of her full-lengths I’veseen, following

The New Years

(Rescue Press, 2014),

M

(The SongCave, 2015) and

Earth

(The Song Cave, 2019), is

Ultraviolet of the Genuine

(The Song Cave, 2025), a book self-described as “an expansive record of time andthought, weaving together philosophy, science, theology, dreams, grief,literary theory, criticism, history, and ideas of utopia—becoming a book thatcontinuously surprises and is nearly impossible to categorize.” “If you thinkwords are made of poems,” she writes, as part of the extended fragment-sequencepoem “POET DILEMMA,” “I mean poems made of words / As we’re taught // I know plentyof words / Though I come from the provinces / Where the earth is filled withviolence [.]” There’s something remarkable in the swoop and the rush of Brooks-Motl’slyrics, a simultaneous sense of compression and expansion, one that allows lessa narrative trajectory than a sequence of thought-clusters that interconnectacross every other moment and cluster across such wider expanse. “In Exeter,England one June or July,” she writes, to open the poem “EXETER,” “we slept onthe floor / Rhetorically, sentimentally—I bring / this up— / not to interpretroses or be watched / by the deer on Pulpit Hill Rd. / Yes it is strange / Ineveryone there is a certain no one / The garden, the blankets the poem / should be a world, a real world/ Savanging the carved stone / Ymaginator / and the demi-angels now / justshapeless blobs [.]”Acrosstwenty-five poems, some short and some extended, Brooks-Motl clearly delightsin extended meditation and play; she delights in structure, delights in howpoems get built and are built, across meaning and rhythm and purpose, across avenuesof articulated exploration. The strength of her poems emerge through the blendof collision and clarity, set precisely in that foundation of poems builtthrough the building blocks of words, achieving far more than a straight lineever could. With each poem, it feels as though Brooks-Motl is slowly building somethingincredibly detailed and impossibly large. All of it, as she said, built out ofwords. “Nothing was plain or open,” begins the poem “MUTTS OF AQUINAS,” “no one/ was invited to explain Chained up all day / you might wonder: To whom does the good accrue?”

July 28, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Luisa Muradyan

Luisa Muradyan

isoriginally from Odesa, Ukraine, and is the author of

I Make Jokes When I'mDevastated

(Bridwell Press, 2025), When the World Stopped Touching(YesYes Books, 2027), and

American Radiance

(University of NebraskaPress, 2018). She holds a Ph.D. in Poetry from the University of Houston andwon the 2017 Raz/ Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize. Additionally, Muradyanis a member of the Cheburashka Collective, a group of women and nonbinarywriters from the former Soviet Union. Additional work can be found at BestAmerican Poetry, the Threepenny Review, Ploughshares, and OnlyPoems, among others.

Luisa Muradyan

isoriginally from Odesa, Ukraine, and is the author of

I Make Jokes When I'mDevastated

(Bridwell Press, 2025), When the World Stopped Touching(YesYes Books, 2027), and

American Radiance

(University of NebraskaPress, 2018). She holds a Ph.D. in Poetry from the University of Houston andwon the 2017 Raz/ Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize. Additionally, Muradyanis a member of the Cheburashka Collective, a group of women and nonbinarywriters from the former Soviet Union. Additional work can be found at BestAmerican Poetry, the Threepenny Review, Ploughshares, and OnlyPoems, among others.1 - How did your first book change your life? Howdoes your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book will always be a reminder to myselfthat what I have to say matters to someone out in the universe. When I startedwriting poetry, my wildest dream was that a press would actually take myridiculous poems about sentient sexy potatoes, Prince, and Predator seriously.I am still amazed that my poems find readers and now that I have a second bookout, I am constantly pinching myself that this is my reality. After I finishedmy first book, American Radiance,which is largely about my family, I promised myself I would move on and writeabout a new topic. My second book, I MakeJokes When I’m Devastated, is even more focused on my family. I realizedthat I’m essentially going to write the same book over and over again, becauseevery poem about my grandmother is ultimately a poem about the moon, andeveryone knows how poets feel about the moon.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposedto, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I am drawn to poetry for the privacy. Most of thetime, I feel naked writing in prose, and while I love reading novels andessays, I need the distance that the lyric provides, or to put it lesspoetically, I want to keep my top on.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

Writing is a long process for me. I think of mybrain as a crock pot that I’m constantly shoving images into. Eventually, Ipull images out after a few hours of staring at my computer screen. A finaldraft often looks nothing like the original version of that poem, and that’stypically because I don’t have a clear idea of where the poem needs to go. Occasionally,I’ll tell myself “I’m going to write a love poem that starts with prunes,” but that’sabout as much direction as I tend to give myself.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very Beginning?

Poems often begin for me with images. I’ll see abursting peony bush and immediately think, “obviously I’ll be writing about youlater,” and continue on my day. I am rarely a writer who works on “projects”and mostly just assembles manuscripts slowly over time. I obsessively writeabout ten different things over and over again, and eventually those poemsbecome a book.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter toyour creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I adore attending readings. I often think of themas a place of tremendous inspiration, and I often feel energized when they areover. For me, there is something magical about hearing poetry read out loud byfriends or poets whose work I am not familiar with.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?What do you even think the current questions Are?

My concerns are endless. I have a thousandanswers for “what do poems actually do?” but none of them feel like the rightone. As a poet who often writes about war in my birthplace, I think about thisquestion often.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

I generally avoid prescribing what the role of awriter should be. As a teacher of young writers, I see firsthand the tremendousimpact that poems have for helping people understand themselves, and also forunderstanding others. To me, empathy and poetry are connected in a way that isessential. I teach “Try to Praise the Mutilated World” by Adam Zagajewski everyyear because that poem saved my life; I don’t know what role that gives me as awriter. Mostly, I’m not that different than a person handing out pamphlets onthe street. I’m giving you something that has transformed the way I see the world, Maybe you’ll remember a line from thispoem when you need it, maybe you’ll immediately throw it into the recyclingbin.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have been lucky to work with some reallygenerous editors throughout the years. For individual poems, I really onlyshare them with a handful of friends and mostly as proof that I am stillliving. When I am struggling with a poem, I find that sharing drafts with a friendI trust is tremendously helpful. I worked with Katie Condon on my last book andshe was essential in helping me iron out some poems that I had over-edited whenI was putting my manuscript together. Since Katie understood my work, she wasable to provide some suggestions for not only how to make the poems better buthow to shape them towards what I wanted them to be.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard(not necessarily given to you directly)?

The best way to learn about writing is by readingas much as possible.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Admittedly, I am on the “parent of three youngchildren” routine which means I’m often writing poems on my phone in betweenhockey practices, in a school pickup line, or during my lunch break betweenclasses I teach.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do youturn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Stanley Kunitz reading “Touch Me” will likelybring me back to earth for a few seconds after I’ve died. When he leans intothe microphone and says “remind me who I am” at the end of the poem I gaspevery single time.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Home is a complicated idea for me as I came tothis country as a refugee when I was a child. What reminds me of Odesa? Thesmell of meat section in the Pryvoz market or the peonies that grew outside ofour apartment building. What reminds me of Kansas City? The smell of bbq andthe park after it rains. My current house smells like mint leaves from tea Imake throughout the day, scented markers in my children’s playroom, or theabsolutely horrific scent of unwashed adolescent hockey gear that lives in my garage.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

I am moved by visual art and often begin writingpoems in my head as I walk through museums or galleries.

14 - What other writers or writings are importantfor your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Gerald Stern is a poet that will always pull meout of whatever writing hole I find myself in. I also have a deep love forMarina Tsvetaeva, Wisława Szymborska, Robin Coste Lewis, Kathleen Peirce,Mahmoud Darwish, Ross Gay, Stanley Kunitz, Adam Zagajewski, Anna Akhmatova, Ada Limon, Tiana Clark, Ilya Kaminsky, Ruth Stone, Matthew Olzmann, Li-Young Lee,Safiya Sinclair, and so many others.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven'tyet done?

I’d love to write a children’s book length poem.I promised my oldest child that this would be our summer project.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

This might be too close to the same wheelhouse aswriting but I think I would be a very good namer of things. I want to bewhoever is in charge of naming nail polish colors, newly invented cheeses,flavors of candy, or recently discovered insects. Are you a beverage companywho doesn’t know what to call your strangely hued newest creation? Allow me tobe drunk with power and name that juice.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

For a long time writing was the thing that Isaved for myself as a reward for doing all of the other things I had to dothroughout the day. Eventually, I got tired of putting my joy Last.

18 - What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

I just finished Traci Brimhall’s Love Prodigaland I recommend everyone with a beating heart buy this incredible book. I alsosaw Sinners last night and it was brilliant.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I typically allow myself to go through a quietphase after I have a book come out. I am currently working on getting back to writing poems morefrequently.

July 27, 2025

i got knocked off facebook on july 2nd, (and where to find me otherwise,

in case anyone was wondering where I've been. I have been fielding an array of emails on the subject, asking if I've blocked or unfriended anyone; I haven't, I've been knocked off, with a perpetual "you submitted an appeal" notice when I try to log in, saying that it usually takes but a day or two to "review your information," but I've been in limbo since, as I said, July 2nd. It's maddening, as it means I've lost hundreds of friends and family contacts. It isn't the same, but if you wish, you can follow me via bsky here, or my instagram here, or sign up for the weekly "Tuesday poem" email list, which often includes multiple other notices for readings, publications, above/ground press, periodicities, Touch the Donkey, the ottawa small press book fair etcetera. I've also a bsky account for periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, the ottawa small press book fair, Chaudiere Books and the (ottawa) small press almanac (given all those facebook groups are now lost to me). Separately, we've a monthly email list for VERSe Ottawa/VERSeFest: Ottawa's International Poetry Festival, or you can sign up (free, if you wish) to my weekly and incredibly clever substack here (where I've been offering excerpts of various non-fiction works-in-progress), or to the above/ground press substack (entirely and completely free), where one can be reminded of events, new publications and even a bunch of brand-new interviews with above/ground press authors. Not the same as facebook, I know, but I don't know what else to do there, as the whole system seems deliberately built to refuse anyone support. Might it reappear? God only knows.

in case anyone was wondering where I've been. I have been fielding an array of emails on the subject, asking if I've blocked or unfriended anyone; I haven't, I've been knocked off, with a perpetual "you submitted an appeal" notice when I try to log in, saying that it usually takes but a day or two to "review your information," but I've been in limbo since, as I said, July 2nd. It's maddening, as it means I've lost hundreds of friends and family contacts. It isn't the same, but if you wish, you can follow me via bsky here, or my instagram here, or sign up for the weekly "Tuesday poem" email list, which often includes multiple other notices for readings, publications, above/ground press, periodicities, Touch the Donkey, the ottawa small press book fair etcetera. I've also a bsky account for periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics, the ottawa small press book fair, Chaudiere Books and the (ottawa) small press almanac (given all those facebook groups are now lost to me). Separately, we've a monthly email list for VERSe Ottawa/VERSeFest: Ottawa's International Poetry Festival, or you can sign up (free, if you wish) to my weekly and incredibly clever substack here (where I've been offering excerpts of various non-fiction works-in-progress), or to the above/ground press substack (entirely and completely free), where one can be reminded of events, new publications and even a bunch of brand-new interviews with above/ground press authors. Not the same as facebook, I know, but I don't know what else to do there, as the whole system seems deliberately built to refuse anyone support. Might it reappear? God only knows.July 25, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Geoffrey Olsen

Geoffrey Olsen

is the author of

Nerves Between Song

(Beautiful Days Press 2024) and seven chapbooks, most recently

In Sleep the Searing

(New Mundo Press 2025) and

Neck Field

(Portable Press @Yo-yo Labs 2025). He lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Geoffrey Olsen

is the author of

Nerves Between Song

(Beautiful Days Press 2024) and seven chapbooks, most recently

In Sleep the Searing

(New Mundo Press 2025) and

Neck Field

(Portable Press @Yo-yo Labs 2025). He lives in Brooklyn, NY. 1 - How did your first book orchapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

The primary change for me is that thecreation of NervesBetween Song allowed me toconceive of writing “books”. As a young poet, I could write series -- 5-7 poems-- before losing focus, then I eventually shifted to chapbook length forms forthe next decade of writing. NBS accumulatesfrom these 10 - 20 poem series. Now, I write in terms of the book-length work,as if the book gave me permission for this practice.

I feel more assured in my activity aspoet and it’s been nice to have more people reach out to me. More friendships,more sense of the visible nexus of poets and our community that invigorates thewriting.

In some ways, Nerves Between Song is my“previous work”: the oldest poems in the book are over a decade old, thoughedited and changed over that time. Across my work there’s an attention to themotion of the poem -- a sense that the poem beckons, but does not dictatemeaning. The writing that follows is always going to play against the impulsesdriving the previous work, as I try to ascertain what new possibilities canemerge.

2 - How did you come to poetryfirst, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wanted to write fiction at first: itseemed the only way to be a writer. Isoon realized that I was not interested in narrative, in character, and thatinstead I was interested in the emergence of detail and language as in motion.I’ve always been drawn to improvisation when it comes to creative activity, andpoetry seemed the ideal medium for me to explore this.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Each work is continuous on some level,though I have been interested in exploring particular forms. Despite writingwithin somewhat similar structures throughout my work, on some level it isimpossible to repeat the form of the poem as it moves with a continuallyaltering pulse of consciousness. We respond to unceasing change: the conduitsof material crisis promulgate poetic intent. Writing exists as accumulatinggesture of undercurrent and submerged energy.

Poems start in motion and do not changemuch from initial writing. There’s a pruning of the work that always happens:cutting away here and there, growing out other aspects.

4 - Where does a poem usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

It is difficult to think of the shortpieces that I write over time and the final book itself as distinct. It tendsto morph as it moves along. That said, my recent manuscript, Rend, -- a portion of this has just beenpublished as the chapbook InSleep the Searing -- wasintentionally prepared as a book-length series of formally united poems: myfirst time writing a sustained work where the form is stable andself-contained, rather than determined in its gradual unfolding over a seriesof poems.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I love doing readings! In the past, Iwould get so nervous and do them rarely, but I’m fortunate to have had enoughopportunities to do them over the years so that the anxiety they generate canbe channeled into excitement. I want to think more about my reading practice,particularly in relation to music. Readings with the musician Ceremonial Abyss,who generates a sonic field alongside the poetry, have been incredibleexperiences and helped me hear the work in new ways. I know I’m not alone inthis -- Ceremonial Abyss has been relentlessly touring and reading with so manypoets across the US. It’s energizing to see the collaborations he’s convening,not just with him but with other musicians, such as with composer and movementartist Lia Simone, who performed with poets Jared Daniel Fagen and Jessica Elsaesser the evening of my first reading with Ceremonial Abyss.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

This is a huge question! The currentquestion for me is how can the US continue to exist in this way where itexploits beings all over the planet so as to perpetuate the control of thewealthy? And then the second question, which comes from this, is where doespoetry arrive and occur in this calamity? What is the space of imagination asinterwoven with our concerns for survival? I also wonder at what can be “said”with the poem, and become more immersed in it as beautiful noise, churningwithin what I experience, what I want to know, what I fail to understand, andyet still drawn to a more abstract music that moves with this, vacated of me.There’s always a certain skepticism involved in my approach to language, andwith that a lot of uncertainty.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Reading Eleni Stecoupolous’s wonderfulnew book Dreaming in the Fault Zone: APoetics of Healing reminded me of the George Oppen quote that poets imagine themselves “legislators of the unacknowledged”. This brings to mind Robert Kocik’s call for poets to make law. I don’t know where I stand. In the unknownprobably.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Working with Beautiful Days cofoundersand editors Joshua Wilkerson and George Fragopoulos was such a satisfying andsupportive experience. They were very thoughtful about the work and onlylightly intervened to refine NervesBetween Song. Poet and novelist Brenda Iijima, who published my chapbook NECK FIELD several months ago, is alongtime friend and influence. I am deeply fortunate to have her as an astutereader of my work for almost two decades now, and as an editor she helped mehone in on the underlying root structure of the poems. It’s essential!

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Alan Davies once told me that one has todo the same thing again and again first before the new emerges, but to do thiswithout repetition. Something about being in the dialectical tension of therepetition and the seemingly new is where poetry happens for me. I feel theprocess is generating a personal syntax, and rhythm, as if one is improvisingon an instrument. That all the discipline is turning toward the practice inmotion.

10 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

My practice is centered on reading andlistening. “Writing” is a continuous occurrence, typically inside as I moveabout my day. I usually write in the interstices of my reading, since withpoetry or theory and then turning to my notebook and writing out a poem. Ialways handwrite poems and type them out usually months later.

I work a fulltime job as a staff at theNew School, so most days start with a commute, but I do try to read poetry inthe morning.

11 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Back to music, back to reading, back tofilm. Medium transfer transmutes stall into flow.

12 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

Decaying leaves. I grew up on the edge ofa forest. Teenage afternoons were spent on the paths that ran through thewoods. I just would walk and be slightly spooked by the surroundings.

13 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music always and often film. The poetryI’ve been working on lately has been influenced by electro-acoustic music andfield recordings, and often pieces of music that operate in both genres. Taku Unami and Toshiyo Tsunoda’s Wovenland series heavily influenced my recentchapbook NECKFIELD, particularlytheir attention to estranging “natural” sounds, generating a sort ofanti-pastoral of parks and streams and other populated outdoor spaces. Theestablished the field in which the horrors of the genocide in Gaza werereverberating through my daily attention and remain the focus of my politicalactivity outside of poetry. My work is (for better or worse) never direct, yetsomething about how they were approaching sound obliquely let me register morein the poems the dire urgency of this moment, when the United States continuesto arm Israel’s war machine over 600 days into this intensification of thegenocide.

As for film, I’m still trying to clarifyits direct importance to my work. I often reference films in my poems --frequently it’s been the filmmakers or . They both offer a duration of image that feels like thinking. Ilike to write alongside and into the feeling that opens up.

Recent work has been engaging with thefilms of Robert Beavers after I had the chance to see many of his films at aretrospective at the Anthology Film Archives. Rebecca Rutkoff’s incrediblerecent book on his work, Double Vision:On the Cinema of Robert Beavers led me to read his film almost as poetry,and as a medium of language, even if that may not have been his intent. I’minto rendering as poetry that which cannot be truly held by it.

14 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My core poets: Leslie Scalapino, Will Alexander, Larry Eigner, P. Inman, JH Prynne, Myung Mi Kim, Roberto Harrison,kari edwards, Brenda Iijima, Nathaniel Mackey.

For theory (recently): Samir Amin,Vladimir Lenin, Raymond Williams

15 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

Write many essays and reviews. This hasbeen something I’ve found very challenging for some reason. It feels abrasivein relation to my poetry practice, requiring a focus that does not come to meeasily. I would also like to write a long poem, though this may or may notalready be underway.

16 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I honestly don’t know how to answer this.Maybe a musician, though part of why I became a poet in the first place isbecause that dream of music collapsed pretty quickly.

17 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

I wanted to be a musician at first -- Iplay the piano, pretty much purely improvisation in solitude. When I began torecognize that wasn’t going to go anywhere, I switched to poetry as animprovisational mode that seemed more suit me much more, and not requireperforming with others, which seemed impossible at the time.

18 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

The last great film was Frederick Wiseman’s Essene: his documentary of a Benedictine monastery in upstate NewYork, released on public television in the 70s. There is a beautiful intimacyand fragility to how the monks relate to each other. It was moving, even ifreligion is not a part of my existence.

The last great book is challenging so Iwill list three! Tessa Bolsover’s Craneis a uniquely ambitious work that straddles theory and poetry. I was raptreading Jennifer Soong’s My EarliestPerson. Thomas Delahaye’s Numéraire wasa work that truly surprised me, a work that delights as the poetry turns inwardon itself.

19 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I started a second manuscript in 2021while I finished editing Nerves BetweenSong and submitted it for publication (which took three years from thecompletion of the MS).

This work, Rend is much more dense and led by sound that the more diffuse andambient Nerves Between Song.

While wrapping this work up on Rend, I have started a long poem. It’snot clear to me yet what this will be as it’s still unfolding. I want it to besomething unspooling wildy, playing with the sentence, which is not usually thelevel I operate on.

July 24, 2025

Kimberly Campanello, An Interesting Detail

The Language

The books don’t know what’sinside their covers, or they don’t care. Just when you learned what washappening, what direction to face, how to move and what to carry where, thelanguage changed. You were reassured it was all still working and thetransformation would be total, just as before. We could just as easily go tothe top of the dune and play with roots in the sand. We could even kneel downand twist them around our hands and wrists to hold ourselves down. As I understandit, the heart can be seen to beat if you can get a glow to show up properlyaround it. Any background will do.

Thelatest poetry title by Irish-American poet Kimberly Campanello, currently aProfessor of Poetry at the University of Leeds, is

An Interesting Detail

(Bloomsbury, 2025), an expansive collection of sequences, prose poems andstand-alone lyrics that extend a sheen of surrealism grounded in concretemoments. “The family walk the sandbar for sand dollars,” the poem “Family Walk”begins, “slip them between toes, foot to hand, and bucket them. The dollars dryto death on the condo patio. The family walk to the cave paintings. They find awild horse in a sinkhole just before it dries to death at the level of theirknees.” I describe the poems within as expansive, but at less than seventypages of poems, this collection is compact, thick as stone and incrediblysharp. “begins with shouting / in sleep I am naked / on the carpet in a powerstance,” opens the poem “Moving Nowhere Here,” “sensing an army nearby / I amcharging the ghost / hanging on the back of the door [.]” Campanello’s poemsbegin with small objects or moments, offering descriptions that expand intolarger ripples of narrative, akin to surreal kinds of field notes.

Thelatest poetry title by Irish-American poet Kimberly Campanello, currently aProfessor of Poetry at the University of Leeds, is

An Interesting Detail

(Bloomsbury, 2025), an expansive collection of sequences, prose poems andstand-alone lyrics that extend a sheen of surrealism grounded in concretemoments. “The family walk the sandbar for sand dollars,” the poem “Family Walk”begins, “slip them between toes, foot to hand, and bucket them. The dollars dryto death on the condo patio. The family walk to the cave paintings. They find awild horse in a sinkhole just before it dries to death at the level of theirknees.” I describe the poems within as expansive, but at less than seventypages of poems, this collection is compact, thick as stone and incrediblysharp. “begins with shouting / in sleep I am naked / on the carpet in a powerstance,” opens the poem “Moving Nowhere Here,” “sensing an army nearby / I amcharging the ghost / hanging on the back of the door [.]” Campanello’s poemsbegin with small objects or moments, offering descriptions that expand intolarger ripples of narrative, akin to surreal kinds of field notes. Much of the collection is constructed via the prose poem, each of which extendout their narratives, both echo and counterpoint to her more traditional lyrics,built of accumulated, almost stand-alone phrases and sentences. Two sides of thesame poetic, one might say, the line-breaks articulating further spaces betweenphrases and thought, although not always where one might immediately think. “Oneremarkable item,” the prose poem “Receipt” begins, “found with a man buriednear where I used to live, turned out to be a whistle made from a carved andhighly polished human thigh bone. Dating suggests it belonged to someone wholived around the same time as him. To bring you up to speed on this, I’mcertain they could squeeze me in here among the greats. It’s what I want. It’simportant to let people know your wishes in advance.” Through Campanello, hersurrealism is held with an anchor to the real, allowing elements of truth toshimmer across the skin of her narratives. As the poem “Use Value” begins: “If Ihad studied / STEM things might / have been different. / If I had fed / intothe meeting / there would have / been an outcome. / The tin whistle / is apassion of mine. / Aren’t I lucky / to do what I’m / passionate about?” Herdetails are moments, and her moments are vast.

They Didn’t Expect

hedges steeplesthe time it takes

to cut awaythe chutes purpling

lips down thepromenade past

nationsstepping forward fire

blocking fireimportant speech

looped in adarkened room

hardy sightseersin rainproof

jacketseverlasting bunkers

farmers orfarmers wives or

farmerschildren blown

up mundanetasks running

commentaryalong the bottom

of thetapestry build up

of bodieswhere do we go

when we diethe lovers

eating theircrêpes her

outrageouslyclassy flowers

their rollingcigarettes like sex

July 23, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Latorial Faison

Latorial Faison

is an award-winningpoet, author, and Assistant Professor of English at Virginia State University,a Historically Black College & University (HBCU). A native of ruralSouthampton County, Virginia, Faison earned a BA in English with a minor inReligious Studies at the University of Virginia, an MA in English at VirginiaTech, and a doctoral degree in Education at Virginia State University. Herwriting boldly explores Black Southern traditions, race, and African Americanculture and identity. Faison’s most recent poetry collection,

Nursery Rhymes in Black

, received the 2023 Permafrost Poetry Prize and waspublished by the University of Alaska Press, an imprint of the University Pressof Colorado. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and a recipient of fellowshipsfrom the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP), VirginiaHumanities, and the Furious Flower Poetry Center.

Latorial Faison

is an award-winningpoet, author, and Assistant Professor of English at Virginia State University,a Historically Black College & University (HBCU). A native of ruralSouthampton County, Virginia, Faison earned a BA in English with a minor inReligious Studies at the University of Virginia, an MA in English at VirginiaTech, and a doctoral degree in Education at Virginia State University. Herwriting boldly explores Black Southern traditions, race, and African Americanculture and identity. Faison’s most recent poetry collection,

Nursery Rhymes in Black

, received the 2023 Permafrost Poetry Prize and waspublished by the University of Alaska Press, an imprint of the University Pressof Colorado. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and a recipient of fellowshipsfrom the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP), VirginiaHumanities, and the Furious Flower Poetry Center.Faison’spoetry and prose have appeared in acclaimed literary publications, such as Callaloo, Obsidian, PrairieSchooner, West Trestle Review, Artemis, RHINO, AuntChloe, About Place Journal, SouthernPoetry Anthology, Stonecoast Review, SolsticeLiterary Magazine, Poetry Quarterly, and Virginia’sBest Emerging Poets. Her work is also featured in notable volumessuch as Three Minus One and the NAACP Image Award-winning Keepingthe Faith. Faison is the author of numerous poetry collectionsincluding Mother to Son, LOVE POEMS, and the Amazon Kindle best-selling trilogy 28 Days of Poetry Celebrating Black History. She is also the author ofthe historical study The Missed Education of the Negro: AnExamination of the Black Segregated Experience in Southampton County, VA,and children’s books Kendall’s Golf Lesson and 100 Poems You Can Write.Faison has received multiple honors, including the Tom Howard Poetry Prize. Shehas been a finalist for the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, Louise Bogan Poetry Award,North Street Book Prize, Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize, and others. A VeteranMilitary Spouse and proud mother of three sons, Faison has served on thefaculty of various colleges and universities throughout the US as well asabroad—wherever military duty called. She holds Life Membership in The PoetrySociety of Virginia, College Language Association, and the historic WintergreenWomen Writers Collective.

1 - How did your first book change your life? Howdoes your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

My first book was a small chapbook collection of poems, entitled PoeticallySpeaking. It allowed me to see what was possible. Holding a book in yourhand with your name on it is powerful, inspiring. I sold over 250 copies ofthat chapbook, which helped to finance the self-publication of my first bookcollection, Secrets of My Soul. That book changed my life in that theworld around me recognized me as an author, a poet. I was invited to myhometown to do a reading and book signing the local community college. Thepeople showed up in support of it, and they enjoyed the poems. That wasassuring, life changing. The people at home, my family, friends, teachers, andcommunity had always had faith in me, supported me. They showed up, purchasedbooks, told their friends and family about it, and the rest was history. Booknumber one made book number two a reality. You can write books. You can sellbooks. But neither are worthwhile without readers. That first book establishedmy audience—the fact that I could even have an audience—and in essence, itchanged my life.

I don’t think my initial work, my first book, quite compares to mymost recent work or this last book collection. The passion for the poetry wasthere in the beginning and the dedication to learning the craft, but my worldhas changed so much then. The world we know has changed in so many ways, forbetter and for worse. How could I ignore it? So much has changed since thatfirst book. In the first book, I was writing out of adolescence and girlhood, asort of early becoming, seemingly with a little naivete and a lot lessexperience. I was a new, young wife, living on love, a new mother, a newmilitary spouse, a college graduate. In my most recent book, I’m writing out ofthe old-fashioned wisdom not only passed down but called on in times oftrouble. I’m writing out of two decades of coming to full grip and reality withsystemic racism, racial inequality, gender inequality, societal capitalism, religioushypocrisy, and having raised our own young Black sons through two eras just asterrorizing to Black males as Jim Crow. My latter work has been a labor of loveand war, joy and pain, awareness, and necessary family, community, nation-building.If we don’t teach and pass down our own history, who will do it for us. Thechildren must know the ways of the elders, how they made it over. My latterwork speaks to the woman I have become; it is a credit to the strong women whohave defined me. It tells a story. Nursery Rhymes in Black is an act ofamplifying Black voices—the elders, the mama’s, the fathers, the sons, and thedaughters. It’s historic, cultural, identifying, and shifting.

I don’t like to compare thework because the one exists because of the other; they each have theirplaces and purpose. But it does indeed feel different because it is different.My first book felt nice, easy, inviting, calm, but strong, assuring,accommodating and bold even. My latter work feels more prolific yet inspiring,intentional, radical yet creative, aggressive yet inviting, demanding yetcollaborative, lyrical, telling, epic, and historic. There’s somethingancestral, mature, and grown-up about the poems I’ve been writing. NurseryRhymes in Black is a collection that marks time, documents history, callsreaders to lean in, listen, to give history and my people attention. I wasn’tnecessarily commanding these kinds of things in my first book, Secrets of MySoul. I was finding my way, sharing my soul intimately, introducing myvoice to the world in a shy kind of way. In these recent works, I have lost allshyness. I am grabbing the mic, owning my feelings, thoughts, and ideas. I’mstanding center stage on the page and confronting so much, everything, usingthe everyday lives of people I knew and loved. Their stories mattered; theirlives mattered. That’s it. I’m telling stories, documenting history in myrecent work. There’s an homage to my upbringing and those who brought me up—allthose experiences culminating in the sum total of me. I was likely paintingpictures and finding myself, my voice in my first collection. In fact, thetitle poem read “Dare me to pursue this / to pen the secrets of my soul / infather time’s precious ink royal black and memory gold.” There’s a difference;there’s an innocence. I was born in that first book. I have come of age in thislast one with lines that must be reckoned with, “Likethree blind mice, three white churches stand watch covering blood shed by whitehoods: one for their fathers, one for their sons, one for their holy ghosts.” Idon’t mince words or hide behind facades in the latter work. I bring it,without hesitation. What I may not have said over twenty-five years ago, I haveto say it now. So much has happened in the in between years. Life demandsthe poetry that I now write.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction?

Nothing has had more influence on mylife than the historical literary and musical tradition that is rooted andgrounded in the Church, the Black church, the Black Baptist church—it’s music,its liturgical, ecclesiastical, oratorical, and theological ways, means, vibes,logos, love ballads, shouts, hollers, and spirituals.

I came to poetry by way of the Blackchurch. I remember holding the Bible and The Baptist Hymnal in my hands asearly as I can remember and following along in Sunday School, Sunday morning worshipservices, Bible studies, and vacation Bible schools in summer with the words ofscriptures, prayers, praise songs, hymns, chants, Negro spirituals.

Scriptures and songs were myintroduction to poetry and old deacons and church mothers’ well-rehearsed andmemorized prayers. I memorized so many. I fell in love with the ebb and flow ofthe words, with the rhythms, the rhyme, with the spirituality of it all, it wasamazing, the most amazing thing I’d ever read or heard or learned or fathomedat those very young tender, teachable moments in my life. I mastered them.

This is how I came to poetry. It drewme—the voice of god, a savior—the lyrics of so many songs inspired by god orwritten to and about god; it was hypnotic for sure, healing, comforting,hopeful, believable—the absolute best therapy and coping mechanism ever for mylittle young, Black self, the best EVER. So, it was poetry from day one, andlater the poetry became nonfiction. I don’t play around much with fiction. Ilove truth. It saves. It heals. It delivers. It liberates. It’s not easy, butit’s freedom.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

It can take anywhere from a minute to years. My writing projectsare not usually things that I’ve started, not my poetic ones anyway. Mydissertation, of course, was a project that I had to plan, start, finish, anddeliver. The poetry doesn’t must happen in that way, whether it’s a single poemor an entire collection. I’d much rather write poems that come to me than tohave a poem commissioned. I like to write what I feel, and you have to feelthings and then be free enough to write about them. Over the years, when Iworked less, writing was easier; there was more time. As my children becameolder and life became busier, more demanding, I have found it harder to findtime to write, to finish projects. My best poems have come when there has beentime—time to feel all the things that I want to capture and deliver in a poem,time to travel back in time or think far into my future about what is, whatwas, and what could be. My grandmother passed in 2008; the poem I wanted towrite for her didn’t come until about three to four years later. I didn’t wanther poem to be something I wrote in a few minutes, day, or a month even. “Mamawas a Negro Spiritual” was a poem I pieced together just like a quilt. It camein patches, in pieces, in figments of my memory and imaginings. For mygrandmother, a poem had to be grand. In the end, it was. It was award-winning.So, it’s a slow process because I like it to be. But sometimes words, phrases,they come quickly, and I jot them down, save them up—they are the patches, thepieces, that ultimately come together in the end. First drafts, second drafts,and sometimes un-trackable numbers of drafts appear. I often know how I want apoem to look but most importantly how I want it to feel, and that’s what I longto master in the final shape and draft of many of my poems, all of my work. Theend is important. Through notes on napkins, notepads, in my phone texts, ordigital notepads and messages, they are worked out and pieced together in myhead and on paper and via computer. It’s a magic that happens, a poem comingtogether.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning?

Poems, for me, can begin with a single word or a phrase that Ilove. They can also begin with a moment, a line from a book or movie or even aconversation. I write short pieces and long pieces. I think my best fallssomewhere in between. In my early writing, I wrote many pieces that cametogether without really thinking of themed collections; they were generalcollections. Today, I write on various themes and subjects (as PhillisWheatley’s first collection), but with more of a theme in mind when writing forcollections or calls for submissions and prizes. I don’t necessarily think of abook from the beginning of a poem. But I do have book ideas. There are kinds ofpoetry books that I’d love to write, various kinds. I must find the time, takethe time, make the time.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have been a public speaker since I was a child. My love forreading in public, like my love for poetry, was also formed in the Blackchurch. I was tasked with reading scriptures and leading songs, publicly, as akid. I don’t mind it at all. I like it even. It comes easy for me. Some havesaid I’m a natural. So, to read my workis natural, to read or recite my poems and talk about them, that’s notnecessarily a part of it, and it’s certainly not counter to the creativeprocess. I don’t write a poem or a book with the intent to publicly read it(thought I now know that comes with the territory), but I mostly write for mefirst. There’s some freedom and deliverance in writing and publishing for me.Secondly, it’s to be read and to inspire or help heal or educate others, toenlighten. I am a storyteller at heart, and even my poems tell stories. So,they don’t have to be read by me. If they are read, that’s enough. But I don’tmind public readings. There’s a dance that can happen between reader or authorand audience, poet, and people. The interaction usually always leads to someamazing, wonderfully engaging, or powerful experience in itself.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

I don’t set out to have theoretical concerns behind my writing,but I know they are there. I’m a Black woman writing. Race in America ispolitical. Gender in America is political. If it’s political, it’s theoretical.I am concerned about Black life, womanhood, the underprivileged, the voiceless,hypocrisy, the evil men do in society—those are my concerns. I am not so muchtrying to answer questions as I am telling a story, testifying, documentinglife, history, and times of people, places, and ideas. I think that we shouldall be asking the questions that will cause us to work harder to make lifebetter. Questions engage. Questions inspire critical thought. We need morequestions, more critical thinking, more engagement, more change, moresolutions, more kindness, compassion, more understanding. I’m interested in whywe do what we do and to whom we do it, and why. It’s circular. It’s systemic.It’s layered. Everybody has a story; everybody’s story is important. I tellmine and many of the stories I know, via poetry, nonfiction, narrative.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

The writer has always had a responsibility to take readers, thepublic, on a journey, down a road, for a ride—the responsibility of giving onea glimpse into a life and/or time they’ve never known or may not be fully awareof. Writers have the role of teaching, providing escape, enlightenment,entertainment, simulation, rhetorical analysis, theorizing. Writers wake us,take us, and catapult us into other worlds where we can be better. The writingmust be, should be, an experience, that changes one for the better. That’s therole of the writer in larger cultural. As an African American woman writer, Icarry the responsibility of cultural analysis and critic, ethnographer, truthteller, revealer.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

I think it’s both difficult and essential, working with outsideeditors, depending on the editor(s). I enjoy working alone, writing alone,going it alone and having it edited in the end. I don’t think I’d like writingin tandem with an editor. Editors are very necessary for the professionalreputation and readability of the work. I don’t write novels. I gather thateditors could be crucial in the various stages of novel writing. I’veself-published for nearly three decades for a reason. I don’t like the idea ofhaving one’s work validated by others, and sometimes that is what happens inrelationships with some editors. Editors have control, and I believe writersshould be in control of their material. Advice is great, but I think a goodeditor knows that and knows there should be a line drawn.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

It hasn’t been one single piece of advice but a compilation of somany pieces of advice: Don’t try towrite like anyone else. Write what you know Write what you imagine. Write thekind of books you want to read. Write the books you have not read. Write foryour own self first. Tell your truth. Tell your story. If you want to be awriter, be a reader. “To thine own self be true.” Never give up. You can do it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetryto creative non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

It has gotten easier over the years to move between the genres ofpoetry and nonfiction. My prose often becomes poetic or lyrical, and my poetryoften becomes narrative. It’s certainly becoming easier with time.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t have a writing routine. I write when I one. I mostly doit, “when the spirit hits me.” I don’t write at certain times of the day or anyparticular way. I am a night owl, always have been. I will steal a momentanywhere to write words, phrases, lines . . . that later become poems. I amalways open to and looking for reasons to write, people, places, and things orideas about which to write. I love to document what I see and feel and hear.That’s the only routine I have, paying attention to life and feeling all of thefeelings it brings—capturing those feelings in poems, essays, or whatever.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When my writing gets stalled or when I feel there’s a block, Ikeep living. I read, watch tv, pay attention to what’s going on in my home, mycommunity, my state, organizations, globally. Things are happening to people,good and bad, every moment. Every moment there is something terrible or amazinghappening, things that bring joy and pain. That always pulls me back into thegame; it brings me back to poetry, writing. I am called to respond. So, I justkeep living, and eventually, something draws me to the page, summons me to getin the game and get busy writing.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The scent watermelon, the smell of freshly cut grass, and thearoma of soul foods, especially sweets—reminds me of home, family, mygrandparents who raised me. I grew up in the country. My grandma was an amazingcook. My grandfather was an outdoorsman with a beautiful garden. My othergrandmother lived just down the road—her sweet potato pies where out of thisworld.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science,or visual art?

Everything I see and hear, taste, smell, or feel influences mywork. McFadden is probably right. But books also come from experience. Poetryis experience. Music is an experience. It influences my work. Trauma isexperience; it influences my work. People influence my work. Places influencemy work. Circumstances, things . . . everything influences my work. And yes,books have influenced my works and so have movies, tv shows, documentaries,entertainers, historical figures, people long gone have influenced my work. Ihave written poems in response to nature, music, science, art, you name it.Poetry is an experience, a response.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

There are absolutely too many writers or writings to name that areimportant for my work. I am in awe of historical poets and writers andlyricists. I have long been a fan of Langston Hughes' poetry, Phillis Wheatley,Douglass’ “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, DuBois’ Souls of BlackFolk, Woodson’s The Miseducation of the Negro, Hurston’s TheirEyes Were Watching God, Angelou’s poetry and iconic Caged Bird, JamesBaldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lucille Clifton, Amiri Baraka, Toni Morrison’spoetry and cadre of works from The Bluest Eye to Song of Solomonand SULA, Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls, August Wilson’splaces, especially Fences, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun,Alice Walker, Margaret Walker’s For My People, Mari Evans, NikkiGiovanni’s poetry, Sonia Sanchez, the late Val Gray Ward, voice of the Blackwriter and founder of Chicago’s Kuumba Theater.

In the last six years, I’ve come to know and love so manycontemporary African American scholars, poets, and writers. I am completely inawe of the work of poets Patricia Smith, Jericho Brown, Danez Smith, Rita Dove,Natasha Trethewey, Tracy K. Smith, Sharan Strange, poets who formed The Dark Room Collective. I have found so manynew friends and sisters in this work as well through Furious Flower PoetryCenter: Joanne Gabbin, Lauren Alleyne, the Wintergreen Women, Nikki Giovanni,Trudier Harris, Daryl Cumber Dance, Maryemma Graham, Meta DuEwa Jones, DaMaris Hill, Desiree Cooper, Opal Moore, Ethel Morgan Smith, Hermine Pinson, Renee Watson.

Oh, and I LOVE Ariana Benson, Cedric Tillman, and Remica Bingham-Risher. The work of Joan Kwon Glass, Jamaica Baldwin, Kendra Bryant,Adrienne Christian, Adrienne Oliver, Glenis Redmond, JeMayne King, DarleneAnita Smith, and Judy Juanita. Gabrielle Pina wrote two amazing books that Icame across when she joined the faculty at my University. Dr. Ayo Morton, anamazing poet, spoken word artist, writer, and scholar is also a new colleagueand sister writer friend. The sisters are writing, and the work is liberating.Then there’s the talented Carmin Wong and gifted Angel Dye, young women, poets,playwrights, spoken word artists, and scholars on fire and on the rise. Avery Young, Chicago’s poet laureate. Jessica Care Moore, Detroit’s poet laureate. Theprolific Dominique Christina who is absolute FIRE!! Tony Medina at HowardUniversity. Amazing!

I am surrounded by beautiful people, by women, by beautiful Blackwriters, artists of all colors and creeds who write powerfully, who arechanging worlds like Liseli Fitzpatrick, Alysia Dempsey, and Leah Glenn founder of the Leah Glenn Dance Theater and Dance professor at The College of William& Mary with whom I’ve had the opportunity to perform and collaborate. Icould literally go on . . . I have not scratched the surface of all the artistswho have engaged me in powerful ways. Durie Harris, Ebony Lumumba, Roxane Gay,and Nikole Hannah-Jones, I love what they are doing in the literary world. Infact, I’ve left somebody out of this group of amazing writers who inspire me,and I’m sorry. But I am blessed to be in the company of some of the greatestwriters who have ever lived. I just met Imani Perry for the first time at aretreat. She is doing phenomenal work. Oh, and my goodness . . . poets Anastacia Renee, JP Howard, Cynthia Manick, Regina YC Garcia. The future is in goodhands.

Some great poets and writers have graced the Earth, left theEarth, but they have left us with their words, and I am daily inspired by poetsand writers who are both ancestors and contemporaries. We have inherited anAfrican American literary tradition and legacy that has kept us, sustained us,and these people are doing the work good, one poem, one play, one article, onenovel, one book at a time. I am happy to be a benefactor, happy to be a part ofit all, happy to continue such a great literary tradition.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a play. Write a novel. Write memoir. Edit a new anthology. Writemy life story, or some of my mom’s. Hers is an episodic thriller—s.h.i.t. thatsells, for sure (smile). See some of my work on the big screen someday, that’sa dream!

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

I’d like to have my own talk show, perhaps radio or podcasting.Had I not been an academic, a poet, a writer, I’d likely have been a goodengineer, pastor, psychiatrist/therapist, or motivational speaker.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Life made me write. Trauma, tragedy, emotions, people,circumstances . . . life made me write; there was nothing else that held orkept or stayed with me like writing. It didn’t cost much to grow as a writer,just time and witness.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

The last great book(s) I have read have included Black Pastoralby Ariana Benson, My Mouth a Constant Prayer by Angel Dye, Lot’sDaughters by Opal Moore, Black Girl You Are Atlas by Renee Watson, Blissby Gabrielle Pina, WORN by Adrienne Christian, What My Hand Sayby Glenis Redmond, The Fire Talker’s Daughter by Regina YC Garcia, and ThoseWho Ride the Night Winds by Nikki Giovanni (for the umpteenth time). I amcurrently reading What We’ve Become by darlene anita smith, We BeTheorizin by Kendra Bryant Aya, and Side Notes form the Archivist byAnastacia-Renee, and other collections. I read fiction and nonfiction, novelsand plays, but I am always reading a poet.

20 – What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on ways topromote my new book, Nursery Rhymes in Black, winner of the 2023 PermafrostBook Prize for poetry published by University of Alaska Press an imprint ofUniversity Press of Colorado. I am working on this in addition to stepping intothe brand-new role of Dept. Chair of The Languages & Literature Departmentat Virginia State University. I hope that readers will get the book. It’savailable via the publisher as well as online at Amazon and Barnes n’ Noble. Ihope that colleges and universities and organizations will invite me to doreadings and participate in festivals and conferences or deliver guestlectures. I have other collections in the works. I have more oral historyresearch on Black segregated education in Virginia that I’m hoping to publishas well as collect more stories and oral history. So, there’s more poetry andprose, more writing, in my future for sure; there’s work to do. All I need istime. Keep up with my new work and happenings online via social media like Facebook,LinkedIn, and Instagram. I serve on the Board of the Wintergreen Women Writers Collective. I am looking forward to all of the new work that will be inspiredby and spring forth from the Collective in poetry, novels, essays, research,scholarship, documentary, anthologies, and digital works individual andcollaborative. It’s a great time to be alive and writing! There’s a lot towrite about and so many good reasons to be a writer in this moment.

July 22, 2025

a fool and his monastaries are soon parted: church and castle ruins, Inishmore (Aran Islands) and Galway quarters, (part two,

[see part one of these notes here]

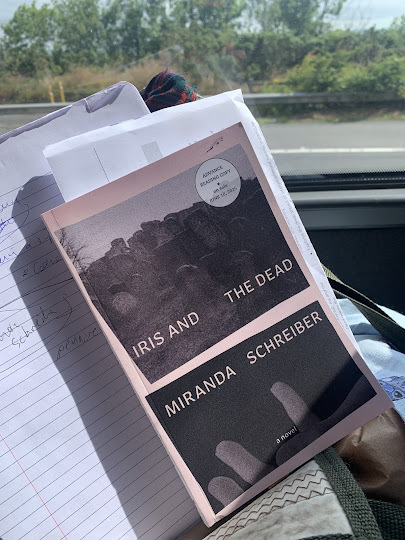

[see part one of these notes here] Monday, July 7, 2025: We woke in Belfast, as one does, and made our way to the shared bus with Rose and her choir, en route to Galway, where the choir would be setting the second city of their three-city tour. I made my slow way through Toronto writer Miranda Schreiber's fiction debut, Iris and The Dead (Book*hug Press, 2025), an intriguing novel composed as a series of journal entries on youth and trauma, seeking to articulate and clarify the past tense (a very readable book, leaning into the young adult, almost). We passed a sign for the Brontë Homeland, ancestral home of Patrick Brontë (b. March 17, 1777), father of writers Charlotte, Emily and Anne, as well as a sign for a Game of Thrones tour, the counterpoint slightly jarring, but providing a particular kind of Irish expansiveness in a very short stretch.

Peat bricks in rows, again. The silence of cows, sheep. Finally, leaning off the highway, a roller coaster (why must they drive so fast, I swear to god) of narrow, ancient roads (often two narrow for passing cars) that took us to the Clonmacnoise (Cluain Mhic Nóis) Monastic Site, the ruins of a monastery originally founded on a slight hill in 544 on the River Shannon, providing a full view of the river distance. And the tower, also, providing an even better view, for when the Viking ships would have arrived for their usual plunder.

The views were stunning, and we even managed a short tour by one of the staff, an archaeologist (who specified that this is very different than a historian): how his job is to interpret the sites, and not simply what is already known (a bit of a slant on his part, I thought, but it made sense; but one can still "discover" new information through discovering new ways to interpret archival materials, but whatever). His name was Ruairí, the Irish name that anglicizes as "Rory" (I have a niece named such, as you might know), which also has the full Scottish variation as Ruairidh (such as the current Clan MacLennan Chief; do you remember when I met him?) (Rory can also be an abbreviation of Roderick). When I offered such, the guide suggested the Scottish was from the original Irish, which I'd be interested to know more about, actually (I had thought Irish Gaelic and Scottish both emerged from a single Gaelic language circa 1200, but I wasn't about to argue with an archaeologist).

The views were stunning, and we even managed a short tour by one of the staff, an archaeologist (who specified that this is very different than a historian): how his job is to interpret the sites, and not simply what is already known (a bit of a slant on his part, I thought, but it made sense; but one can still "discover" new information through discovering new ways to interpret archival materials, but whatever). His name was Ruairí, the Irish name that anglicizes as "Rory" (I have a niece named such, as you might know), which also has the full Scottish variation as Ruairidh (such as the current Clan MacLennan Chief; do you remember when I met him?) (Rory can also be an abbreviation of Roderick). When I offered such, the guide suggested the Scottish was from the original Irish, which I'd be interested to know more about, actually (I had thought Irish Gaelic and Scottish both emerged from a single Gaelic language circa 1200, but I wasn't about to argue with an archaeologist). Can you imagine this tower was originally twice the height? Apparently it got cut in half not long after it was built, so they made a whole new tower down the hill with the ruin, which is amazing to consider. Would such a tower have remained intact for near a millennium if it had been twice the height?

Can you imagine this tower was originally twice the height? Apparently it got cut in half not long after it was built, so they made a whole new tower down the hill with the ruin, which is amazing to consider. Would such a tower have remained intact for near a millennium if it had been twice the height?Our guide conjectured that the historians were incorrect that this was a tower for the sake of protection or as a longer view (one can see pretty far simply by being on a hill), but one of securing valuable items in case of a raid. If the vikings en route, a monk would climb inside (as the doorway is raised up from ground level) with the valuable books, and lift the rope ladder up, thus preventing anyone from following. The only drawback being, of course, that the vikings would have simply tossed in a torch, and lit the whole thing up to either burn or smoke them out (not a perfect system, certainly).

The tour guide also introduced us to a whispering doorway, where one could whisper quietly into one side of the doorway and be heard if one were to place an ear on the other side of the doorway, as a kind of open-air confessional. Whisper quietly, to be barely heard, but to be heard. Some of the choir tested it, and apparently it worked.

The tour guide also introduced us to a whispering doorway, where one could whisper quietly into one side of the doorway and be heard if one were to place an ear on the other side of the doorway, as a kind of open-air confessional. Whisper quietly, to be barely heard, but to be heard. Some of the choir tested it, and apparently it worked.Near the end, the choir leader, James, organized the young ladies within the bounds of the ruin of the main building, as they did an impromptu performance [I took photos but do not include here, as one does not post photos of other people's children upon the internet sans consent]. It was incredible, and brought tourists in from all corners of the site to quietly listen, take photographs and recordings (which I wasn't terribly fond of them doing) and simply take in. I've seen versions of this before in other places, other sites, but the experience is far more resonant when one of the participants is your child, after all.

I was curious about this particular ruin [above] just outside the boundaries of the monastery, as we were leaving, but it had not been mentioned. I would presume this an extension of the same thing, possibly. Hm?

From there, we returned to the bus, and the roller coaster of ancient roads (it made for a number of us to feel quite loopy/queasy), and eventually landed in Galway, a very pleasant and seaside tourist town. The whole time, I had a particular Waterboys song in my head, as I'd once heard they from here (although they're from all over Scotland and Ireland, it would seem). Galway smelled like Vancouver, a bit. There were little flags everywhere, as we seem to have found ourselves in a tourist area for dinner attempts. Once we landed, the whole crew, at our university residence, the choir went in one direction, and we went into another, everyone pulling bags and seeking rooms and figuring ourselves out. Although by the time we had completely figured ourselves out from our room, the choir had already been out and was returning from the city centre, where they'd had dinner (roughly a thirty minute walk, we eventually figured out), so we used their cab for our own attempt out into the world.

Upon landing, we saw our pal Susan with some of the older choir members, catching some bubble tea. An old resident sidled up to me there, a bag of wine bottles clattering along, as he insisted he knew me, he knew me. I gave him a "poem" handout, and he said, about time. He knew me, oh yes, he knew me. He was a Bishop, once. Oh, yes. The choir girls looked worried, a bit confused. When Christine mentioned I'd been in Galway back in 2002, he, what? No, he didn't live here then, he was somewhere else. [Reader: I do not think he knew me.]

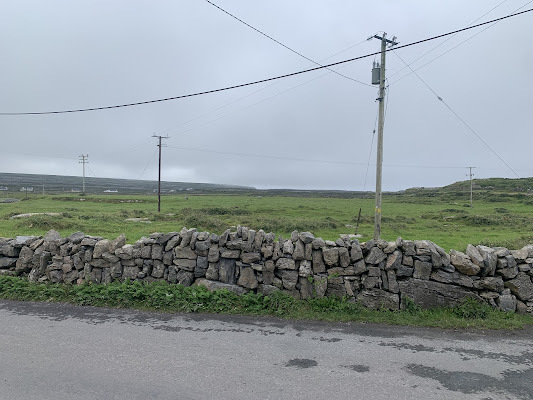

Tuesday, July 8, 2025: We woke and quickly got on a waiting bus and accompanied the choir on a day-trip to Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. At the ferry docks, an outcrop of tourist businesses (including bicycle rental, for those wishing to explore the island on their own) and an array of shops, pubs, horse and buggy rentals, that sort of thing. There were Bed and Breakfasts everywhere, scattered around the island as well. Thirty-one square kilometres and a population of less than a thousand. Enough stone everywhere (fencelines, houses, other structures) that one might think they grew from the ground (something I recall from when Stephen Brockwell and I drove across the west coast of Ireland back in 2002, even seeing some houses, roofs et al, made of stone).

Tuesday, July 8, 2025: We woke and quickly got on a waiting bus and accompanied the choir on a day-trip to Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay. At the ferry docks, an outcrop of tourist businesses (including bicycle rental, for those wishing to explore the island on their own) and an array of shops, pubs, horse and buggy rentals, that sort of thing. There were Bed and Breakfasts everywhere, scattered around the island as well. Thirty-one square kilometres and a population of less than a thousand. Enough stone everywhere (fencelines, houses, other structures) that one might think they grew from the ground (something I recall from when Stephen Brockwell and I drove across the west coast of Ireland back in 2002, even seeing some houses, roofs et al, made of stone).

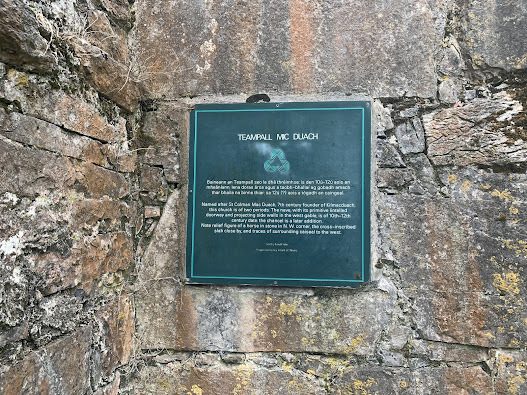

We immediately went for a tour bus that rolls and strolls an hour around the island, slow meanderings into and beyond. Half-through, we landed in a bit of a courtyard, with some shops, and the bus driver told us we had about ninety minutes or so, before we needed to head back down to the ferry.