Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 12

June 27, 2025

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part one: Bardia Sinaee + George Bowering,

Anotherfair has come and gone! Thanks to everyone who participated, from exhibitors to volunteers to readers to audience! And did you see I made shortbread? Be sure to save the date for this November, when the fair will turn thirty-one years old. That’s pretty exciting, yes? I’malready working on dates for June and November 2026 (which feels a millionyears away, I know). And of course, see my reviews from last fall’s thirtiethanniversary ottawa small press fair here (parts one, two, three), or last fall’sToronto International Festival of Authors’ Small Press Market (parts one, two,three, four) or even my notes from last spring’s ottawa small press book fair(parts one, two, three). So much small and micro press activity! Here are thefirst of my notes from what I picked up this time around:

Anotherfair has come and gone! Thanks to everyone who participated, from exhibitors to volunteers to readers to audience! And did you see I made shortbread? Be sure to save the date for this November, when the fair will turn thirty-one years old. That’s pretty exciting, yes? I’malready working on dates for June and November 2026 (which feels a millionyears away, I know). And of course, see my reviews from last fall’s thirtiethanniversary ottawa small press fair here (parts one, two, three), or last fall’sToronto International Festival of Authors’ Small Press Market (parts one, two,three, four) or even my notes from last spring’s ottawa small press book fair(parts one, two, three). So much small and micro press activity! Here are thefirst of my notes from what I picked up this time around:Ottawa ON: The latest from Ottawa poet Bardia Sinaee,author of Intruder (Anansi, 2021) [see my review of such here], is thechapbook Flinch (2025), a title, according to the colophon, “wasco-published by Skunkwords and Horsebroke Press [a press run by Ottawa poet Jeff Blackman] in Ottawa in May 2025 and distributed as issue 33 of TheseDays Zine.” There’s almost a wistful distance, a wistful quality, to these poems,offering a bit of distance across first-person observations so deeply personal,even intimate. “I can’t / remember why / I walked into / this room,” the poem “StillLife” begins, “with its / packed-away smell / & painting / of a water mill[.]” There’s such a lovely and delicate nuance to these short musings, theseshort narratives, one that holds an edge but not by displaying that edge; onethat provides a clarity beyond clarity, and into a far deeper understanding ofbeauty, and life, such as the last three stanzas of the two-page final poem inthe collection, “Love Poem,” that reads: “I don’t / miss the cancer / or theward / but the time / we snuck into // the shower / we thought / would be our /last together / I loved shampooing / your hair // it was like / breathing /under water [.]”

Household items

after receiving theliterary prize

I upgraded to ocean-friendlytuna

I finally cleaned themicrowave

then thinking better ofit

ordered a new microwave

spruce tips in antiquepinch bowls

reed diffusers inlavender oil

I curated the air

carrying on like I hadalways

known refinement

we are instructed to dothe negative

the positive is already

within us, wrote Kafka

who would have liked

to be a loaf of hardbread

that’s why I keep my mind

smooth as a pearl

grown from a splinter

a poem is not a wildanimal

roving the page

a poem is not a journey

it is always already here

anyone can access it

with only a few householditems

& ten thousand dollars

Phil Hall, Canadian poet

Phil Hall, Canadian poetVancouver BC/Cobourg ON: From Stuart Ross’ Proper Tales Press comes an odd assortment of poems from Vancouver writer and troublemaker George Bowering, the chapbook Phil Hall (2025), acollection with a photograph of Perth, Ontario writer and editor Phil Hall byPaul Elter on the front and back cover, as well as within, although the poemsin this collection may or may not have anything to do with that particular PhilHall. These are poems by Canadian poet George Bowering that reference Canadianpoet Phil Hall, playing with a slightly fictional Phil Hall that may or may notresemble the actual writer. As the opening piece, “Notes on the Life of theCanadian Poet Phil Hall” begins: “Phil Hall once took a jar of sand from a beachon the west coast of Costa Rica to Chad and emptied it into the Sahara. A companionreported him as saying, ‘Find that, you arseholes.’” These pieces are delightfullyodd, with narratives running from the entirely plausible into the completely implausible,running a fine line between the two until, of course, Bowering takes the wholesurrealist play up a level. With poem-titles including such as “Phil Hall andthe Chickadee,” “Phil Hall and My Mother,” “Phil Hall’s Macaw” and “The Malladeof Phil Hall,” this is a delightfully odd and entertaining small collection,one I entirely recommend you pick up a copy of. Although, I probably should have asked: What does Canadian poet Phil Hall think of all of this?

Phil’s Fiction

Over a warm October weekin Oliver I wrote a terrific love poem to my wife, who was visiting friends inCumberland.

Then one afternoon it rained, so there was no orchardwork, so Phil Hall sat down for an hour and wrote what I knew was a better poemfor her.

They were nice about it. They sent me a postcard fromCumberland.

I decided to quit poetry and wrote a story about lostlove and orchard work.

Phil wrote a story while having lunch with some of myVancouver friends. It won a prize in a Victoria literary magazine.

Over seven years I wrote a novel about a matricide inVancouver. It made the short list in a national creative writing contest. Philcame in the winner. And wrote three other books on the short list under pennames.

They sent me a nice postcard from Ottawa.

June 26, 2025

reminder : poetry manuscript evaluation services,

It seems as good a time as any to remind folk: for nearly thirty years I've been offering, to anyone interested, evaluation, editing and otherwise help shaping a poetry manuscript for potential publication. $300 for a manuscript up to 100 pages, or $400 for up to 150 pages.

It seems as good a time as any to remind folk: for nearly thirty years I've been offering, to anyone interested, evaluation, editing and otherwise help shaping a poetry manuscript for potential publication. $300 for a manuscript up to 100 pages, or $400 for up to 150 pages.I keep hearing my rates are low; I should probably up my rates at some point soon (but not quite yet).

If you are interested (or know anyone else who might be), send me an email at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com.

June 25, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rachel Hadas

RachelHadas [photo credit: Shalom Gorewitz] is the author of over twenty books ofpoetry, essays, and translations, most recently a collection of brief, lyrical prose texts,

Pastorals

(Measure Press 2025).

RachelHadas [photo credit: Shalom Gorewitz] is the author of over twenty books ofpoetry, essays, and translations, most recently a collection of brief, lyrical prose texts,

Pastorals

(Measure Press 2025). A recipientof honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a fellowship at the Cullman Centerfor Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, and an award inliterature from the American Academy-Institute of Arts and Letters, she taughtEnglish for many years at Rutgers University-Newark, in New Jersey, andcurrently teaches at 92Y in New York. She divides her time between new York City and Danville, Vermont.

For moreinformation please see www.rachelhadas.net

1. How did your first book or chapbook changeyour life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How doesit feel different?

My firstbook was indeed a chapbook, Starting from Troy, published by David R. Godinein 1975. I was in my twenties, and muchof the poems had been written when I was still an undergraduate. I don’t know that the book changed mylife! I remember that I had unreasonableexpectations of what effect this tiny book might have. The journalist and poetDon Marquis commented a century ago that expecting a poem or a book of poems togarner much attention would be like dropping a rose petal down the Grand Canyonand waiting for the echo. That’s stilltrue; if anything, there’s now a veritable digital blizzard of rose petals, butthey’re all pretty silent.

As far as how my most recent book (Pastorals,2025) compares with my first book, nothing dramaticcomes to mind. Not that my work hasn’tchanged and developed; of course it has. But I’ve written so much over the past half a century – a dauntingamount and a daunting span of time – what itfeels arbitrary to single out one book just because it happens to be my mostrecent. I’ve developed, I hope, adistinctive poetic voice, which is unabashedly literate and also personalwithout being confessional or hermetic. My themes are often memory and loss, but I also pay attention to domesticdetail and the look of my surroundings, whether they’re a Greek island,Riverside Park, a classroom, or a hospital room. The life-raft of language – the phrase isJames Merrill’s – has carried me over experiences from motherhood tobereavement to teaching. I’ve alwaysbeen drawn to the waypoetry unites the outside and the inside – what Hannah Arendt called the publicrealm, the world we share, and the private world of emotions, dreams, and ourdaily consciousness, what goes on inside our heads. How to make sense of these two worlds, how totie them to together, how to make beauty from our human bewilderment?

2. How did you come to poetry first, as opposedto, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve neverhad the slightest talent for fiction, for making up a story or characters orworking out a plot. I have great admiration for some novelists, but I’m not oneof them. Nonfiction prose I’ve enjoyedwriting over the years; sometimes book reviews or essays, sometimes poems thatasked to be turned into prose. But mynative medium has always, always been poetry.

3. How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don’talways know when or whether I’m starting a writing project, or quite how I’ddefine such a project. If the “project”is a poem, I’ll probably scribble something down, and it might take ten or morerevisions to lick it into shape, as the Roman poet Virgil described his writingprocess. Thoserevisions might take a week or less, or might take years; in the latter case Imight put a poem down, perhaps thinking it’s finished, and then look at itagain and realize how flabby it is. Often the leaner, tighter versions afterrevision are much stronger. “Copiousnotes” – not really. Copious drafts, sure. I’ve gotten much better at self-editing over the years.

4. Where does a poem or work of prose usuallybegin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona “book” from the very beginning?

I alwayshave more poems around, some published in periodicals, some unpublished, thancan fit into a book; the challenge is to carve the best book out of thatunwieldy mass. It’s rare for me to workon a book from the beginning. I didbecome aware, in writing my caregivingmemoir Strange Relation (2011), that the various poems and prosepieces in it all belonged together, but it took me a while to sort them intosomething like a coherent chronological order. As I say, I’m not a natural storyteller. My new book, Pastorals, is something of an exception too; earlyin 2023 I realized that my many poems about our house in Vermont all bore astrong family resemblance, needed to be together, and needed to be trimmed ofredundancies. And somewhat surprisingly,they also (not having been among my most formally ambitious in the first place,and I am something of a formalist) needed to be…prose! I’m not too fond of the term prose poem, butthere you are.

5. Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Publicreadings are fine if I don’t have to travel far or move heaven and earth to setup a reading. As I get older I am lessinvested in them. Literary conferencesor festivals which feature readings often have so many crammed into a few daysthat the readings become a bit of a trial for all involved.

6. Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questionsare you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Theoreticalconcerns; questions….These are interesting questions which the current fraughtand angry state of discourse turns into loaded questions. In trying to come up with a thoughtfulanswer, let me quote the wise elder, poet, and thinker Robert Pinsky, whorecently had this to say about the role of poetry, which I see as the genrewhere my main contribution lies: “…theart of poetry…takes for its medium each individual person’s breath: inherently,and by its nature, on an individual and human scale. That is the solace of poetry: not thereassurance of safety, but the restoration of human scale, theimportance of each person, amid a world of risk.”

7. What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

That quotefrom Pinsky above applies to this question about the role of the writer inlarger culture. If bywriter we mean poet. The other kinds ofwriting I happen to do are largely literary-critical and speakmore, I think, to the threatened areas of general knowledge and culturalmemory. Book reviewing for one – and thebooks I review are either poetry or nonfiction. A scholar like Edith Hall, who combines knowledge of the classics withmemoir, is right up my alley; see her fascinating 2024 book Facing Down the Furies.

Clearly,the role of the writer depends on what kind of writing they’re doing. I’ve studied classics and comparativeliterature and have translated both Ancient and Modern Greek. But perhaps more to the point, I grew up at atime and in a culture and family that was saturated with literature, and thatgeneral literary culture, which I feel I’ve absorbed by osmosis, serves me wellnow in unexpected and amusing if not lucrative ways. I retired from many yearsof teaching at Rutgers-Newark at the end of 2022, and thus have plenty of timeto devote to – well, what sometimes feels like answering questions aboutliterature which might come at me from all directions. In addition to being poetry editor of twovery different periodicals, Classical Outlook and The Robert Graves Review, I’ve been asked to in the past few weeks to contribute an opinionabout the American poet Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962); to blurb a book aboutHerodotus; to review the excellentCanadian poet Karen Solie; and to help celebrate the American poet Anne Sexton (1928-74). I am not a specialist! But that’s what general knowledge – literaryand cultural knowledge – seems to mean.

8. Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

I haven’tworked much with outside editors; increasingly I am my own best editor. A good editor can be incredibly valuable, butthere are hardly any of them around anymore. In general I don’t think poets or critics much on editors, for better orworse. Poets tend to be generous withtheir time (of course there are exceptions) when it comes to reading andcritiquing other poets. I think of MollyPeacock’s wonderful recent book about her long personal and poetic friendshipwith Phillis Levin, A Friend Sails in on a Poem; or of David Kalstone’s 1989Becoming a Poet, an examination of the literary friendships of MarianneMoore and Elizabeth Bishop, and then of Bishop and Robert Lowell. As Elizabeth Bishop wrote long ago, poets keep each other warm all over the world. This is a case where email can be a boon.

9. Whatis the best piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Oh gosh,many things come to mind. Mary Jo SalterI think (where did I hear this?) liked to say to her students “Remember, yourreader has a job” – which meant that they had other demands on their time thandecoding your hermetic poems! A.E. Stallings has advised “You cannot be too obvious, you cannot be too clear,”meaning not that poets should avoid clarity (I know it’s ambiguous) but the opposite:try to be intelligible. The practice ofasking for prose accompaniments to poems, which David Lehman has adhered to inhis Best American Poetry series, and which is now our policy at ClassicalOutlook, is often illuminating, but it can also reveal a startling gapbetween what’s in the writer’s head and what makes it onto the page.

10. How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres (poetry to essays to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Movingbetween genres can be a good strategy for avoiding burnout and boredom or acreative brick wall, so long as one isn’t on a strict deadline, which I rarelyam. I might work on a book review in themorning and a poem or poems in the afternoon, or vice versa. Once I have drafts I start to edit, but theprocess of revising poems feels more leisurely than in the case with bookreviews or translations, particularly book reviews, for the simple reason thatlike most poets, I’m not inundated with time-sensitive requests for poems.

11. What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

I don’thave a rigid writing routine and never have had one. But I do tend to get antsy if I haven’t atleast revised or looked at a poem in progress, or started something new, in aweek or two (more antsy now that I’m retired – I used to be able to shelve workin progress when I was teaching). Ingeneral, mornings are good, lunch and right after is nap or sleepy time, and Imay or may not work in the later afternoon or the evening, depending. In the early months of 2017, when I was onsabbatical, I wrote almost all the poems that were published in Poems forCamilla (2018) sitting up in bed – my husband, as I recall, would bring mecoffee. But unlike Edith Wharton, Ididn’t have a maid to collect the manuscript pages I tossed to the floor whenI’d finished writing on them.

12. When your writing gets stalled, wheredo you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

As I saidin answer to #10 above, moving between genres is good if you’re stalled. Translation is a good exercise. Reading, or letters from literary friends,can be good. But as David McFadden is quoted as saying in #14, books come frombooks. Not exclusively, but veryoften. There’s also, it occurs to me,the oracle of the everyday: what do I see out the window? What did I dream last night? What about that conversation I suddenlyremember having or overhearing?

13. What.Fragrance reminds you of home?

Fragrance:hmm. In Vermont, woodsmoke. Lilacs ifwe’re there early enough. In New York,sometimes petrichor, the indescribable smell of a rain-washed sidewalk. Pizza fragrance wafting out of an opendoor. Marijuana drifting down thestreet.

14. DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science, or visual art?

As well asbooks, poems can come from walks, dreams, paintings, and countless other piecesof experience including memories. Science, music, the daily phantasmagoria of the news.

15. What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside your work?

Really toomany writers are important to me to list. My life outside my work is sort of a head-scratcher. Here’s a wildly incomplete andunchronological list: Homer, Lucretius, Virgil, Keats, Proust, Anthony Powell,Edith Hall, A.E. Stallings, James Merrill, Thoreau, Lydia Davis. Baudelaire. Tolkien. Seneca.

16. Whatwould you like to do that you haven’t done?

I wouldlike to have known my father, the classicist Moses Hadas (1900-1966) for muchlonger than our lives permitted – I was seventeen when he died. But that doesn’t come under the category of“haven’t yet done,” does it? I both doand do not want to travel more, but not the way today’s travel conditionswork. Mostly my wishes involve havingthe health and energy to keep on doing what I love doing – writing, teaching –and to be able to spend more good time with my husband, my son and his wife,and friends. Not an imaginative list,perhaps, but not implausible either. Oh,and one literary genre I feel vaguely attracted to is drama – not fiction,never fiction, but voices. even encouraged me once, at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, to try my hand at writing a play. But when he heard that I didn’t have anagent, the matter stopped right there, which is okay.

17. If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

When I wasa little girl I wanted to be children’s book illustrator, or perhaps a monk ornun who illuminated manuscripts. I love to draw and paint in watercolors but amnot as good at those things as I used to be, which was never great. I started making collages around the time thepandemic started, and I still enjoy that. I’d never ever get into medical or nursing school, but I sometimes thinkI was a healer in another life. Or aninterpreter of dreams – but not a therapist!

18. What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

Writing waswhat came naturally and early. And myfather’s death helped kick-start me into writing poetry. “Death is the mother of beauty,” WallaceStevens reminds us. I never used tounderstand that, but I do now. Therewas never really a “something else,” unless one counts teaching, which alsocame pretty naturally. There stillisn’t.

19. What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

Last greatbook I read? I’ve already mentioned the Edith Hall. I adored A.E. Stallings’s2025 study of the Parthenon marbles, FriezeFrame. I’m currently rereadingTrollope’s maddening and wonderful Can You Forgive Her? Last summer Ireread, and loved all over again, Lucasta Miller’s biography of Keats via poems. I read poetry all the time – most recently Charles Martin, Karen Solie, Juliet Mattila, and RichardTillinghast –there’s always something to savor. The weekly zoom group I’ve been in since 2022 has read Ovid’s Metamorphoses,Virgil’s Aeneid, and now Homer’s Odyssey. I and a couple of others hope that ParadiseLost will come next. The last film Isaw in a theater period was the very enjoyable Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown. Great? I don’t know.

20. What are you currently working on?

I’m currently accumulating poems for maybe aNew and Selected, not sure. I seem to bewriting a lot, so there’s a lot of winnowing to do. Recently finished: a prosimetrum (prose andpoetry alternating) about myth, ie both poems of mine inspired by myth andprose interludes talking about the occasion of the poem, its inspiration,whatever. Put together, the proseportions form a kind of patchy memoir. This book is slated to be published late in 2025 or early 2026, but I’mnot holding my breath.

I’m also currentlyengaged, in a desultory way, with typing up the contents of commonplace booksI’ve kept for well over a decade – jottings down of passages I’d read thatseemed worth hanging onto. The resultingcompilations can also be sources of inspiration (see #14 above). For example, a phrase from something Howard Nemerov said or wrote, which I’d never have remembered had I not noted it downyears ago, inspired a sestina recently when I rediscovered it in my notebook.The phrase goes something like this – I can’t even remember it word for wordthis minute: “The world is always weaving itself over the ruins.”

June 24, 2025

Martha Ronk, Clay

Introduction

As a child I was certain Icould put my hand through the wall, that if I kicked gently my shoe would nudgethe other side of drywall. I wanted to feel it all the way through, to gobeyond the impenetrability of substance, to be inseparable from whatever itwas. Years later a faculty member with large hands taught a ceramics class;could I join it just to do something hands-on, wet, physical, material—other. Ingraduate school my life was hours in a library writing until late in theafternoon when I rode a bike to share a wheel and kiln in a damp basement. Thena career that included more papers, more words, more essays, until finally now,I have returned to the ceramic studio. I’m drawn to throwing bowls—their roundedusefulness, their similarity to cupped hands holding emptiness itself. Hands andskin and wet—involvement with a material substance. In one’s life one looks forthis sort of time when time itself slips by and all else has receded out of consciousness.I find it in writing (often ekphrastic poems), I find it at the wheel, and I alsofind it in paintings of vessels, jars, bowls: in Morandi, Cezanne, Heda wheretouch resides within sight.

Thelatest from Los Angeles poet and fiction writer Martha Ronk, following morethan a dozen books, including

The Place One Is

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn,2022) [see my review of such here], is

Clay

(Omnidawn, 2025), a booksubtitled “Bodies + Matter.” Set as a collection of prose poems aroundproducing clay pottery in a studio, Ronk’s poems quickly evolve into a largerconversation around touch, including the tactile sense of building somethingwith one’s own hands, and the tactile sensation of human connection and contact.“when we touch the moving clay we are in the midst of and we are in it,” shewrites, as part of the poem “One with matter,” “torqueing, bending, lifting //the work of shaping, of skin, of watery touch, / of breathing with the air thatinfills the cavity of clay / rounding it out, pushing against the sides [.]” I findit curious how Ronk seems to approach each poem, with titles such as “throwinga bowl,” “Emptiness,” “As a child,” “Porcelain bowls for the Chinese emperor”and “Celadon glaze,” each poem tracing and surrounding her subject as a kind ofself-contained wholeness. Her titles exist as umbrellas, or even prompts,allowing her to move outward and explore from that single, seemingly staticpoint. Or, as the poem “What am I before touching something?” begins: “What am Ibefore touching something out there, / some vagueness of limbs, extensionsmeant for unfolding [.]” A few lines down in the same poem, writing: “noboundary between what’s out there and these hands, [.]”

Thelatest from Los Angeles poet and fiction writer Martha Ronk, following morethan a dozen books, including

The Place One Is

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn,2022) [see my review of such here], is

Clay

(Omnidawn, 2025), a booksubtitled “Bodies + Matter.” Set as a collection of prose poems aroundproducing clay pottery in a studio, Ronk’s poems quickly evolve into a largerconversation around touch, including the tactile sense of building somethingwith one’s own hands, and the tactile sensation of human connection and contact.“when we touch the moving clay we are in the midst of and we are in it,” shewrites, as part of the poem “One with matter,” “torqueing, bending, lifting //the work of shaping, of skin, of watery touch, / of breathing with the air thatinfills the cavity of clay / rounding it out, pushing against the sides [.]” I findit curious how Ronk seems to approach each poem, with titles such as “throwinga bowl,” “Emptiness,” “As a child,” “Porcelain bowls for the Chinese emperor”and “Celadon glaze,” each poem tracing and surrounding her subject as a kind ofself-contained wholeness. Her titles exist as umbrellas, or even prompts,allowing her to move outward and explore from that single, seemingly staticpoint. Or, as the poem “What am I before touching something?” begins: “What am Ibefore touching something out there, / some vagueness of limbs, extensionsmeant for unfolding [.]” A few lines down in the same poem, writing: “noboundary between what’s out there and these hands, [.]”Some pots seem undefinable.The “Hu” pots from the Han Dynasty (206 BC to AD 220) appear to move and breathe.

Exploringthe working of clay and a history of pottery, Ronk’s poems work to bring oneback to sense, into senses; as an attention to surrounding detail, and how onemight better relate to both environment and other people, connecting to a farwider tapestry of human interaction, culture and history. “Touching—a mode ofinadvertency— / holding the bowl,” she writes, to open the poem “Touching,” “spinningthe clay, / dipping into chalky liquid, its ultimate color / hidden—how impossiblenot to envision the past / whether Chinese or one’s own / impossible not to bepulled into geography, [.]” With accompanying full colour and black and whitephotographs of bowls, Ronk’s Clay is a collection of poems that centredelicate care and human touch, the importance of physical and human connection,and the physical making of objects with care, and with one’s hands.

June 23, 2025

Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi, Disintegration Made Plain and Easy

another day another

Another day another

Soup god I

Am simple I

Will dunk my

Bread into the

Rain whatever juices

In the nightbowl

I make love

My mouth is

Full of bread

The moon stops

Like a clock

Overhead god how

I fall how

Must I eat

Twice my weight

In salt

I’mreally enjoying the narrative connections, disconnects and accumulations of thepoems in Bellingham, Washington poet Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi’s DisintegrationMade Plain and Easy (Chicago IL: Piżama Press, 2025). This is the firstvolume in a new press founded and run by Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany, “dedicatedto showcasing and uplifting the voices of the strange, the uncanny, the absurd,and the surreal.” I’ve been aware for some time that Niespodziany has quite agood eye for such work, his social media and substack long offering remarkablygood examples of poems and poets I might otherwise have not been aware, fromthe contemporary to the historical, working the surreal short, condensed and/orprose poem.

I’mreally enjoying the narrative connections, disconnects and accumulations of thepoems in Bellingham, Washington poet Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi’s DisintegrationMade Plain and Easy (Chicago IL: Piżama Press, 2025). This is the firstvolume in a new press founded and run by Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany, “dedicatedto showcasing and uplifting the voices of the strange, the uncanny, the absurd,and the surreal.” I’ve been aware for some time that Niespodziany has quite agood eye for such work, his social media and substack long offering remarkablygood examples of poems and poets I might otherwise have not been aware, fromthe contemporary to the historical, working the surreal short, condensed and/orprose poem. Disintegration Made Plain and Easy is set in twocluster-sections of poems, interspersed with illustrations (as well as an “INTERMISSION”between the two sections of poems) by Los Angeles-based illustrator, animator and interaction designer Gautam Rangan. “I like to get naked // I guess becauseit makes // Me think about death,” Araki-Kawaguchi writes, to open the firstpoem in the collection, “i like to get naked,” which stretches across threepages in a monologue reminiscent of the classic “Sex at 31” series (a series I’m sure no one actually recalls anymore), around death, sex and moving throughtime. The accumulative rhythms of Araki-Kawaguchi’s poems I find quitefascinating, as they suggest themselves as purely self-contained phrases piled atopeach other, offering, instead, real subtle twists and turns connecting phrases andrhythms as much between the lines as through. And then, of course, there arethe incredible “about the author” poems, six of which are sprinkled through thecollection, the second of which, a prose poem, begins: “The most striking thingof Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi’s poetry is he is so damn FINE. The words combining onhis page aren’t great. But as a reader you can imagine him freaking GOOD in hiscutoff shorts. Tan as lobster. At a rectangle in starbucks. Implement betweenwriting claws. Gazing moronically into the blank page.”

Araki-Kawaguchi’spoems are surreal, funny, dark and odd, composed via direct statements that accumulateacross distances, even through the prose poem structure, writing sentences thatpile atop each other to form shapes. His use of the double-space betweenstatements and phrases, for example, even provides a kind of pause for the reader,holding back what otherwise might seem propulsive through other poems,including those set as more direct prose-stanzas. There is something quiteremarkable in the way he twists and turns expectation, offering from the offseta point from which one couldn’t even begin to suspect, once you’ve read one or twoexamples of his work; he offers establishing direction almost as red herring,playing with expectation, and rushing off into completely unique and unknownrealms. “Devil devil in my heart,” the poem “devil devil in my heart” begins, “Icreated earth and heaven / In my own image yes / It is all extremely poorindeed / None of the horses have heads / How terrifying they are to ride / Andfeed I must pulverize / Their grass in my mouth [.]” His work provides a finebalance between laughter and horror, surrealism and whimsy in a series of poemsthat can’t help but delight. “You know what a man needs,” he writes, to openthe poem “what a man needs,” “I think we can all guess what he needs // Thepower to see himself clearly [.]”If the father of the American prose poem,Russell Edson, worked against expectation in his work, Araki-Kawaguchi’s DisintegrationMade Plain and Easy is working at a whole other level of surprise, whimsyand surreal twists. This is an incredible collection.

he is going to have totake it

I am not throwing a party

No I am not throwing aparty

But I would like to hirea clown

Yes I would still like tohave a clown today

I will enjoy him even if Iam alone

I will enjoy him more ifwe are left alone

I do not like thepressure to laugh

It is like beingstrangled

With an invisible twine

I will only laugh when itis true

I will only laugh when mybody feels

Like it would otherwisedisintegrate

Because of the clown’smovement

Because what he does formy amusement

In the quiet empty room

In exchange for a lot ofmoney

I put into the hands ofhim

I will only laugh when heearns it

I will put a lot of moneyno matter what

No I am not throwinganything

He is going to have totake it from me

June 22, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cara-Lyn Morgan

Cara-Lyn Morgan

is a citizen of the Metis Nation and the descendant of enslaved people in North America. She was born in Oskana, the area commonly known as Regina, Saskatchewan, and her work explores cultural duality, decolonization, motherhood, and the historical and present-day impacts of colonization. She currently lives and works in the Greater Toronto Area. She is a wife, mom, gardener, and neighbour. Her first collection,

What Became My Grieving Ceremony

was awarded the Fred Cogswell Award for Poetic Excellence and was followed closely by her second collection,

Cartograph

. Her third book,

Building A Nest from the Bones of My People

, has been warmly received since its release.

Cara-Lyn Morgan

is a citizen of the Metis Nation and the descendant of enslaved people in North America. She was born in Oskana, the area commonly known as Regina, Saskatchewan, and her work explores cultural duality, decolonization, motherhood, and the historical and present-day impacts of colonization. She currently lives and works in the Greater Toronto Area. She is a wife, mom, gardener, and neighbour. Her first collection,

What Became My Grieving Ceremony

was awarded the Fred Cogswell Award for Poetic Excellence and was followed closely by her second collection,

Cartograph

. Her third book,

Building A Nest from the Bones of My People

, has been warmly received since its release.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When I made my decision to go to art school and to study writing and visual arts, I had a foreboding sense that I had disappointed everyone. As the child of an immigrant, it can often feel like you are on a set path of success and there’s a great deal of anxiety that surrounds a life choice that threatens “security.” I had a feeling that my parents felt I was indulgent and somewhat petulant in my choice, believing that writing was essentially a “hobby” and that I should explore options that were much more stable, writing in my spare time. But I believed that I had a story to tell and that I was worthy of the investment to tell it, so when Thistledown accepted my first manuscript and my book was eventually published, I felt very vindicated and validated in my choices to that point. The physical book felt like proof that I was not just writing as a way to entertain myself.

My most recent work is a complete departure in style and in content from the previous two works. This is because I am a completely different person than I was when I started telling stories, specifically ones about my family. Since I first published, I have become a wife, a mother, someone who understands the mechanics of editing, someone who understands colonization and intergenerational trauma differently—I simply navigate the world from very different eyes. I’m a matriarch, and I feel a greater responsibility to this current book because it is a new legacy for me. These family stories are uncomfortable and sad, so I have shifted from writing “love letters to the family” as my previous books have been described. But no, maybe that’s unfair. This collection is a love letter to the family as well, because it was written out of a deep love and loyalty. I wrote this collection because I love my children and I want them to know where they come from.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I began my studies at UVic thinking I was a fiction writer—I fully expected to write novels. But part of the curriculum was to do introductory courses in a variety of media and I was blessed to study in one of Tim Lilburn’s poetry classes. He told me early on that my work was important and no one had ever said this to me. I had always felt like writing was a luxury that I indulged in and was kind of good at, but no one had ever read my work and said “this work is important and people should read it.” I found that poetry was the medium that worked for the stories I wished to tell. It was the medium that connected with how I walked in the world—paired down, hyper focussed. It was the closest thing to painting and visual arts (which I was also studying) in a writing style, and so it felt very organic and familiar to me. There’s a purity in poetry, it is the embodiment of art for art’s sake—we spend a great deal of time and energy creating it and are rarely compensated financially for the work we do. It’s a shame but it’s beautiful as well.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My first two books were written rather quickly and came out relatively close to each other, within a few years I believe. This current one took a great deal longer, for a variety of reasons. First, it deals with very fresh trauma which I experienced in real time, recorded as journal entries as a mechanism to process the trauma, and then wrote into poems. Simultaneously, I met my future husband, got married, and was quickly pregnant, all while navigating a totally alien reality without my family (as I knew it) and dealing with post-partum anxiety, post-trauma stress, and a gamut of other things all culminating at once. So, the book took much longer to conceptualize and to flesh out. I remember editing and revising while my newborn slept on my shoulder, being interrupted mid-thought by her as she stirred. I no longer had endless time to work, my time was no longer my own.

In terms of my process, I normally begin writing long-hand through a process Tim Lilburn taught me called “emptying the hands” where I basically write subconsciously, just a stream of thought for a set amount of time without editing or even reading it back. From there, I return to the writing a few months later and comb through the rambles to find a good line or thought, phrase or feeling, and that is usually where the poem comes from. They are born there, and I build from that. I’m also a note writer—I find scraps of paper with short lines of poetry or phrases which I compile over time and sometimes those become the poems.

Definitely my writing at the beginning of my career looked very different in draft than it did as a finished collection, but I feel like this current work had a much more cohesive flow and content—I knew what I was writing and why, so it came together for me. The order of poems, for instance, stayed relatively consistent from draft to draft.

I would also say that one of my main editorial tricks is that I have no problem sacrificing my lines—some writers get very attached to a certain line, or image, or phrase, but I am not this way. I am happily ruthless in the culling of words if it makes for tighter writing.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think currently I do write with a collection in mind—I have become a much more conscientious writer as I have matured. This is, I think, motherhood, and the necessity to use my time as efficiently as possible, as so little of it now belongs to me. I used to have a lot of space in my life to writing about just everything and anytime in an attempt to find beauty. I have experienced a lot of changes in my life over the past decade and those changes have altered my perspective and my approach to writing. These days, I eek out a bit of space for my work and have to get written what I need to write with the awareness that at any moment some aspect of my life will emerge, and that if I have not writing my thoughts down I may not get an opportunity to do so again. So I write very feverishly these days, my poetic lines are shorter and my images are more plain. This is because likely a small child has popped into my poetic space to ask a question or be comforted, or whatever it is they require at that moment. I lose lines and thoughts and phrases just as my children lose their cleats, this piano music, their matching socks.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love reading my work in public, even though I am an introvert by nature and relatively shy person (though I am often accused of saying this falsely because I am able to mask my shyness after four decades), I have always enjoyed readings. I think this is because I write poetry to be read aloud, it is an aural art form and part of a storytelling tradition that feels good to me—this is the good medicine of our Elders. Storytelling is healing, and so reading feels like that to me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Definitely I have many concerns with my work as it is rooted in family, history, and is extremely intimate. In my current collection, I had to be extremely aware that the story I was telling was about my own perspective and my own experiences of trauma, despite the collection being centred on the family, their experiences, admissions, stories, memories, etc. I wanted to ensure I was telling the stories without adopting any one else’s trauma, and that I was fair to my own perception and my own navigation of a very difficult circumstance. I actually had to rewrite the collection in the editing phase when I became aware that a family member who had read one of the drafts was feeling extremely stressed and vulnerable due to some of the stories I had decided to tell—there are no words that I could ever write that would be worth putting that kind of pain in to the world, so I made a choice to rewrite. My publisher was generous in allowing this, and I think the work was far more successful as a result of this. In terms of questions—I am always trying to answer the questions about who I am, and where I come from. I have always been interested in family stories and the ways in which they influence how we walk in the world. Now that I am a mother, I also seek to write in a way that will help my children to understand our history-whatever that may be. I think as a Metis person and as someone descended from enslaved peoples, there will always be mystery. There will always be questions about who we were, and what our people endured to get us here. I want to write down everything I know, as I understand it, so that they will have access to their own stories.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I can’t speak to all writers but I can speak to poets, who I believe have an essential role in society. Poetry, with its curated lines, holds up a mirror to society in a way that perhaps other genres do not. It is hyper-focussed—we are the recorders of the precise way that dust flutters in a ray of sun, of how the swirled bark of a tree feels when we place our finger tips on it. We consider the daffodil, the pucker of sumac in the hinge of the jaw. Poets remind us that we are interconnected, that we are all relations. And poetry is a genre that is the embodiment of art for arts’ sake. We write because we are drawn to create work, not because of the promise of financial compensation or even because of the desire to be read. Poets quietly record the world almost in opposition of attention, and I think that in a world that is constantly demanding attention and is constantly seeking a wider audience, we need that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Absolutely essential. I think that outside editors remind us that not everyone navigates the world as we do. They are so important to helping us see beyond our own writing—I often hyper-focus on whether I should be using a semi-colon or if I broke my line before or after a specific word, and miss that something I have written can be interpreted in a completely different way or that from a cultural perspective may mean something other than what I had intended. When we are creating work that we intend to send out in to the world we have to do so with the understanding that no everyone will understand what we are saying and not everyone will be engaged, and having an outside set of eyes grounds the work by letting us block interpretations. Often editors will say to me “you said this, but did you mean to say this other this?” and if I don’t want a line or a stanza or image to be read in a certain way, I can use language an other poetic tools to block that reading.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Rest is resistance. This is something I take extremely seriously as a woman who is both Indigenous and the descendant of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Generations of trauma and oppression have disregarded the need for women (especially women of colour) to engage in rest and self-care, and self-reflection, and quiet contemplation. But someone once gave me the permission to rest, and they explained that it is the greatest form of protest. I try to live by this.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think these two genres serve very specific purposes in my life—I have always loved colour and texture and visual art (both creating and observing it), and so here’s a tactile connection for me between the creation of visual art. It feels like physical story telling, but is also extremely humbling because it is 100% open to the interpretation of the viewer. Painting, for me, leaves no room for me to say “No, I meant to say this” when someone looks at my work and tells me “I see this.” I just have to accept that interpretation and remind myself that we all see the world only through the eyes that we have, not through what people tell us we must see. Poetry is more about expressing my thoughts. I have always written to save myself from carrying the heavy stuff. Writing poetry releases these stories from my brain, and perhaps, from my responsibility. So that I can continue to grow and evolve and look for new ways to record the world as I see it.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Nowadays, my routine is dictated 100% by my family and children specifically. I no longer have a regular writing practice, and instead seek to find time where I am able. I supposed I have become a very undisciplined writer but a relatively disciplined mother.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I never worry when the work slows down. Sometimes I think this happens to give me space to process information so that I can write it better, sometimes it is because I have new stories and experiences unfolding that will eventually become work. I am proud of the work I have created, and I have always had the feeling that if that is all I was ever meant to write, it would be ok. That said, usually the “stall” is just a regeneration period, and the work reveals itself either by way of experience or inspiration.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Grass. I have prairie bones, so wet crops. Alfalfa. The moments before rain falls. These are prairie smells, that is my home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Family stories are my biggest influence. I have always been interested in memory and how our memories change from person to person, and how all families seem to have that collective desire to speak of the past. Even if the past they recall is sterilized or even fabricated, there’s a human-ness to sitting at a table late at night and falling in to recall. I have always loved to hear these stories, and as I have grown to better understand the world, I even appreciate the difficult stories. I feel deeply that our ancestors, those who know the story’s ending, want us to tell stories because stories are how we heal and grow.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I am very interested in non-fiction work currently—I love Helen Knott’s memoirs. Becoming a Matriarch speaks to me so much, that book came in to my life exactly when I needed to face my own evolution. The Hon Murray Sinclair’s memoir Who We Are is also close to my heart right now. I feel like everyone needs to read that book to better understand this country and how to further reconciliation within it. Bad Cree by Jessica Johns is another recent read that I really enjoyed. It seems I’ve taken a break from reading poetry.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to go to culinary arts school and open up a bakery that caters to people with food allergies. I have a child with multiple life threatening allergies and have spent a great deal of time and energy learning how to give her food experiences that are relevant culturally and also safe, and I feel like in a perfect world I would have a beautiful little bake shop where people can come in and feel safe and have an experience that makes them happy about the food they are experiencing. I’d sell dairy-free ice cream and nut free pastries, sesame-free bread and beautiful chocolates.

I used to make allergy safe candies to sell at local markets, and I can’t even count the times that someone would try them and start to cry. A mom once said she had never shared a chocolate bar with her son before. I’d love to keep giving people those kinds of moments.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, I spent 20 years as a uniformed officer with Canada Border Services Agency, and in fact, I wrote most of my first draft of my first book sitting in one of those booths where you show your passport. For some reason that is very funny to most people who know me only as a writer. And the fact that I write poetry is always so mystifying to anyone who knows me only as a law enforcement officer. These days, I teach police officers Indigenous culture and history and reconciliation. But I would have liked to have been a baker or a pastry chef. How different a person I would have been though.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was taught to use writing as an emotional tool early on, to help process the trauma of my parents’ divorce and other adverse events. I journaled and wrote so that I wouldn’t be overwhelmed by things I was experiencing as I grew up, and now I use writing to process intergenerational trauma, and to send stories in to the world so that I do not carry them alone. I have always written, so I it doesn’t feel like it was ever a choice. I just did it.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

As mentioned above, Helen Knott’s Become a Matriarch is top of mind. I also loved Sinead O’Connor’s memoir Rememberings. It takes a certain bravery to write a memoir and though I write a lot about my life through poetry, it feels some how easier because poetry comes in breaths and snippets. I have always love reading the memoirs of interesting women though, and these two are extremely interesting. In terms of films, I feel like I have been watching Disney cartoons exclusively for the past seven years but recently I took a flight and re-watched the 1986 version of Little Shop of Horrors with Rick Moranis and Steven Martin among others. That is a great film, I have always loved it but realized that I didn’t understand what I was watching when I had seen it as a child. I loved the music and the singing and thought it was funny at times, but sometimes you have to revisit these types of stories once you’ve lived long enough to have been through some things. They hit differently now—but man, the music in that movie is still so good.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a collection of stories about homecoming—I recently travelled to my dad’s birthplace in Trinidad and Tobago and my mother’s/my birthplace in Saskatchewan and have been looking at ways in which returning home after learning painful truths about your family feels different. I travelled to many of the sites of my own childhood traumas, spoke to myself as a child in those places. I think there are some interesting poems coming out of those recent travels.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 21, 2025

John Phillips, Language Being Time

THE POINT

Why add more

words to the

too many there

already no one

pays much

attention to or

acts differently

after reading

as if the point of

it all were acting

differently which

hopelessly it is

Ittook some time for me to get to, but I am finally moving through British poetand expat currently living “in the hills of central Slovenia,” John Phillips’ fifthfull-length poetry collection

Language Being Time

(Shearsman Books,2024), a book that follows his

Language Is

(Sardines Press, 2005),

What Shape Sound

(Skysill Press, 2011),

Heretic

(Longhouse, 2016) and

Shapeof Faith

(Shearsman Books, 2017) [see my review of such here]. His shortlyrics each sit the small measure of a koan, thoughtfully offered and considered,held with a small turn. His are not the extreme and casual densities of poemsby such as Cameron Anstee [see my review of his latest here] or the late Nelson Ball [see my review of his selected poems here], but something quieter, looser,and at times, more flexible, subtle.

Ittook some time for me to get to, but I am finally moving through British poetand expat currently living “in the hills of central Slovenia,” John Phillips’ fifthfull-length poetry collection

Language Being Time

(Shearsman Books,2024), a book that follows his

Language Is

(Sardines Press, 2005),

What Shape Sound

(Skysill Press, 2011),

Heretic

(Longhouse, 2016) and

Shapeof Faith

(Shearsman Books, 2017) [see my review of such here]. His shortlyrics each sit the small measure of a koan, thoughtfully offered and considered,held with a small turn. His are not the extreme and casual densities of poemsby such as Cameron Anstee [see my review of his latest here] or the late Nelson Ball [see my review of his selected poems here], but something quieter, looser,and at times, more flexible, subtle. Hewrites in small turns, poems that occasionally offer a narrative hinge mid-way,where the poem might alter direction, or a straight line heading somewhereother than you might have been thinking, through a deeply thoughtful andengaged poetics. Listen to this short poem, “DISPENSATION,” in full, thatreads: “History begins / when loss is / saying what / no one present /understands / this going / towards when / & where / no tense / makes sense[.]” As well, I appreciate this note set just at the end of hisacknowledgements, hinting at further engagements, which I would be interested tohearing more than this single hint of what is most likely far larger, andongoing (including with another favourite of mine, American poet John Levy): “Certainpoems are from collaborations with John Levy and James Stallard in which we respondedto each other’s words.”

REPLY

This poem isn’t written

until you finish

readingit

June 20, 2025

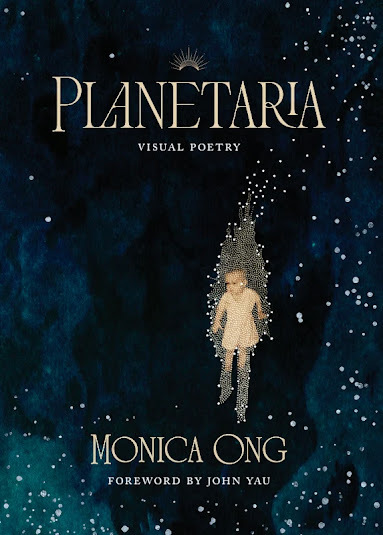

Planetaria: Visual Poetry by Monica Ong, with a Foreword by John Yau

At the beginning of hermarvelous book, Planetaria, Monica Ong declares her intention with anepigram taken from Chien-Shiung Wu, a Chinese-American particle andexperimental physicist, who was known as the ‘Queen of Nuclear Research’:

The main stumbling blockin the way of any progress is and always has been unimpeachable tradition.

Instead of aligning herwriting with an established, avant-garde agenda, Ong has defined a fresh trajectorythat arises out of living in the diaspora while being aware that we inhabit an expandinguniverse. By incorporating family photographs, Chinese star charts, astrologytexts, scientific diagrams, unwritten and neglected histories and biographies,and symbolic language, she is able to synthesize aspects of the microcosmic andmacrocosmic into something original and disruptive.

Ong’s visual poemsreplete with charged language expose the obstacles shaping an individual’slife. Motivated by a propelling desire to dissolve the constraints of literarytradition, gender bias, family history, and cultural beliefs, she hasintervened in classical Chinese texts and written shaped poems in praise ofwomen scientists, always making something new (John Yau, “Foreword”)

Iwould say you absolutely have to get yourself a copy of Planetaria: Visual Poetry by Monica Ong, with a Foreword by John Yau (Trumbull CT: Proxima Vera,2025), a stunningly-intricate blend of visuals and text as simultaneous poetrycollection, experimental memoir, visual poetry assemblage and fine art catalogue.Planetaria is a book on family, constellations, loss and storytelling, wrappedin a visual array of wistful gestures and grounded expression. If you aren’t awareof Connecticut-based American poet and artist Monica Ong [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], she is also the author of the poetry debut

SilentAnatomies

(Tucson AZ: Kore Press, 2015), selected by Joy Harjo as winner ofthe Kore Press First Book Award in poetry, with further work appearing innumerous journals including Scientific American, Poetry Magazine,and in the anthology

A Mouth Holds Many Things: A De-Canon Hybrid-Literary Collection

(Fonograf Editions, 2024), among other places. Planetariais swirling with full-colour gloss, as Ong collages text on maps of constellationsand an archive of family photographs that weave stellar cartographies andmythologies across a tapestry of storytelling, family story and song. Her gesturesare heartfelt, visual and far-reaching, ever looking to the stars to hold whatthe ground allows. As she writes: “This interactive poem takes the form of alunar volvelle. As the moon reveals its ever-changing shape, so too does thepoem that radiates from the volvelle’s heart. Fear not. During the full moon,my father’s mother will watch over you.”

Iwould say you absolutely have to get yourself a copy of Planetaria: Visual Poetry by Monica Ong, with a Foreword by John Yau (Trumbull CT: Proxima Vera,2025), a stunningly-intricate blend of visuals and text as simultaneous poetrycollection, experimental memoir, visual poetry assemblage and fine art catalogue.Planetaria is a book on family, constellations, loss and storytelling, wrappedin a visual array of wistful gestures and grounded expression. If you aren’t awareof Connecticut-based American poet and artist Monica Ong [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], she is also the author of the poetry debut

SilentAnatomies

(Tucson AZ: Kore Press, 2015), selected by Joy Harjo as winner ofthe Kore Press First Book Award in poetry, with further work appearing innumerous journals including Scientific American, Poetry Magazine,and in the anthology

A Mouth Holds Many Things: A De-Canon Hybrid-Literary Collection

(Fonograf Editions, 2024), among other places. Planetariais swirling with full-colour gloss, as Ong collages text on maps of constellationsand an archive of family photographs that weave stellar cartographies andmythologies across a tapestry of storytelling, family story and song. Her gesturesare heartfelt, visual and far-reaching, ever looking to the stars to hold whatthe ground allows. As she writes: “This interactive poem takes the form of alunar volvelle. As the moon reveals its ever-changing shape, so too does thepoem that radiates from the volvelle’s heart. Fear not. During the full moon,my father’s mother will watch over you.” Ifind it interesting that Ong includes a back cover blurb by Los Angeles-based poet Victoria Chang, as the pieces here are reminiscent of the interplaybetween the collage-visuals and prose stretches of Chang’s own stunning non-fictionproject, the deeply intimate Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief (Minneapolis MN: Milkweed Editions, 2021) [see my review of such here], a book that also writes of memory, history and mentors. Through bothvolumes, there is a particular collaboration between the visuals and the text,each one reacting to the other to create something that sits amid and surroundsthem both, wrapped into a single, sustained image or narrative thread. The imagesthat Ong collages and employs here are not there to accompany her text, butexist as one half of a larger structure along with those texts, offeringdifferent structures and purpose from piece to piece, from visual poems to whatappear like large visual art displays to more subtle blends of image and words.While other contemporary visual poets might be attending smaller, evensequential, works that interplay visual and text, such as Canadian poets Kate Siklosi, Gregory Betts, Gary Barwin or Erín Moure, Ong’s Planetaria isan expansive, full-bodied book-held installation, a structure my dear spouse suggestedwas closer to the blend of collaged image and text of what BritishColumbia-based writer Nick Bantock began with his debut novel Griffin andSabine: An Extraordinary Correspondence (Raincoast Books, 1991), the largernarrative structure of the work including visual and physical elements,although Ong’s doesn’t share the design and narrative (convoluted) intensity ofBantock’s novels. And while this collection does include a startling array ofvisual poems, I wouldn’t call this a collection of visual poems per se,as Ong’s visual poems are but part of a much larger and complex multitude of textand image structures, with much of the collection built out of works that workto interplay and collage the elements of visual and text, but more in way ofconversation or counterpoint than as a sequence of individual pieces where one formisn’t able to be removed without the whole structure collapsing (whereas thismight be me simply splitting hairs, admittedly). This is absolutely beautiful,and narratively complex. As the poem “WOMEN’S PLACE IN THE UNIVERSE” writes:

Odd number. Odd girl. Oneis an observation. The other, a polite indictment. She preferred to arrange herstudio against the laws of symmetry, her way of saying up yours to Confuciusand his man-pandering precepts. No matching pillows, tilted walls, her father’sbooks all perfect bound yet bent like a wormwood granny’s feet.

Imagine a woman’scalculations opening up the sky, the sun’s orbit but a mole on the lip of solarclustered nipple. How she spilled the milk from the glass of her astronomer eyeknowing it would feed another hunger in another womb of time.

Mathematics were justforeplay. There is nothing wrong with being easy. Any man can scribble odes toflatter a goddess of the moon. She turned her garden into a laboratory todecipher the secret turning of the stars. Behind the ecliptic strung up crystal,she glimpsed her face in the lunar mirror’s gleam.

Infinite planets. Her endlessether. There are those whose greatness grows in shadow, whose outer limits thespotting of blood cannot contain.

June 19, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Holly Flauto

Holly Flauto's

book of poetry,

Permission to Settle

(Anvil Press), is a CBC Books pick for Best Canadian Poetry of 2024. The memoir-based poems fill in the blanks of the application to immigrate to Canada, while investigating the implicit biases in the colonial system of boxes and check marks that still seek to categorize "the other" and to harness it in the face of reconciliation. Holly grew up moving between the USA and South America; she immigrated to Canada in 2008. Holly teaches creative and academic writing in the English department at Capilano University.

Holly Flauto's

book of poetry,

Permission to Settle

(Anvil Press), is a CBC Books pick for Best Canadian Poetry of 2024. The memoir-based poems fill in the blanks of the application to immigrate to Canada, while investigating the implicit biases in the colonial system of boxes and check marks that still seek to categorize "the other" and to harness it in the face of reconciliation. Holly grew up moving between the USA and South America; she immigrated to Canada in 2008. Holly teaches creative and academic writing in the English department at Capilano University.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

This is my first book! And it’s certainly changed my life. The biggest change is my own confidence in my writing and the willingness to tell people “I’m a poet!”

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’m not sure I can confidently say I came to poetry first. See now that I said above I am more confident saying I’m a poet, now I have to admit that I’m not. I have published both short stories and essays – and I love storytelling on the stage. I think the idea finds it’s genre for me most often. As ideas emerge they sometimes pull themselves into poetry or maybe from poetry to fiction or creative non-fiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m feeling a very slow start right now to my next project, but Permission to Settle came quite quickly. I even have lots of poems that didn’t make it into the collection. My first draft looked very different for the book. I considered the poems as one long poem, and it was only after getting some editorial and mentoring support that they became more individual poems.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I feel like I generally start with an idea that seems like it will be short, but then it goes somewhere else sometimes. I find that I obsess over the same themes for a while where similar lines or shapes or ideas keep repeating across different pieces of writing. So, I’m often working on a theme through a few pieces, and then sometimes those will kind of merge together in something longer. Sometimes the theme moves forward and sometimes the short starting pieces just get to then hangout on their own.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love readings! Love, love, love. I love talking to other writers, I love the audience questions, I love it all. The book has been a portal into being able to do that. I wrote my book to be in conversation with the reader, and I love how that can happen in real time in public readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My reoccurring theoretical concerns, I think, are about identity for one, and then with that comes relationships and family. And there’s always the current of exploring inequity and privilege and how we normal immigration and inequities. Theoretical underpinnings of antiracism come from academic writing and composition, and the work of Asao Inoue about the systemic racism inherent in how we assess writing and grammar.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think the role of the writer is to be in conversation with what’s happening in the world around them – with world being defined however they’d like. The writer can bring ideas forward and into other people’s thoughts and conversations and writing and art. We all build on each other.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. The real difficulty is getting back in the mind space after that period of time when you’ve released the work as the best that you can do right now. So there’s that initial reluctance to change something because it means work, even when you see it’s the right direction. I have to think of it as a bit of an uphill part of the trail, where you need to push yourself a little.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write what you are afraid to write about. (Thanks, Rachel Rose!)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to memoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

Easy! But only if I’m ok with it changing as I’m writing. Hard when I’m trying to stay in one genre with an idea and it won’t stay there. It becomes a more difficult project when the idea has to change to fit the genre instead of the other way around.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My best writing is done when I stick to a routine, but for some reason, I don’t do it with consistency. I am most productive in community – writing groups, online and in person.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Writing events – public readings, really – are the most effective form of inspiration for me. Art museums sometimes, maybe something I’m reading too, or a writer being interviewed on the radio or a podcast. But hearing writers talk about their work and ideas and hearing them read in a space with others is when my ideas notebook fills so quickly.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Garage. Is that a fragrance? There’s a certain smell of the garage at my mom’s house. It’s dead leaves and boxes and memories and somehow the ice cream in the outside freezer.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I love to sit in an art gallery and write. I have so many poem fragments musing about pieces of art. I don’t think I’ve ever thought to revise these for submission anywhere, strangely. But art

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I feel like I could never list all the writers or writings I find important. One that always resonates with me is Leonora Carrington. I love the magic of her stories and how they feel like painting and stories and myths and truths and dreams all at the same time. My book came into it’s form after reading Chelene Knight’s Dear Current Occupant. I learned through that book that a whole book could be one poem really and I could be so indulgently memoir-y in poetry.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to finish a novel. I have one almost done – but it’s been in that state for almost years now. It is my white whale of a project.

I wonder sometimes if I should give up on it and start another one. I have a story that keeps asking me to complete it – and I’m pretty sure that completion is novel-length. I’m resisting.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I love teaching. I had a brief career in upscale retail management that I also loved. Dream careers if it’s all possible: improve actor, artist of large scale paintings, photojournalist, talk show host.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Compulsion. I have to write. It’s an undercurrent of anxiety that’s always there.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m not a very astute film watcher. I am very sensitive to violence on screen – domestic violence, other violence, et al – and the intensity of seeing that and hearing it and feeling it is often overwhelming, especially when I don’t expect it as part of the story. And it’s so often part of the story.

The last great books were The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington, Dandelion by Jamie Chai Yun Liew and All Fours by Miranda July.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Great question. I just finished teaching for the year, and I’m having trouble transitioning back into writing mode. Teaching is intense! I made a list of ideas compiled from all my scraps of ideas penciled or typed all over the place. It has about 20 ideas on it. Then I highlighted four. I’m trying to pick one. Maybe others can weigh in? Should I choose idea 1, idea 2, idea 3 or idea 4?

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 18, 2025

Hajer Mirwali, Revolutions

January 22

In 1994 Mama gave birthto me in Amman on

her way from Baghdad toRichmond Hill and

Mona with wood sand metalelectric motor

transported us to thefirst home we were

exiled from. Two daughtersof a revolutionary

split. Two mothers of acontracting uterus

waiting to be Palestinianagain.

Past noon. Shadows castby a swinging

mobile are longer,higher.

Repetitive sounds mimicMona’s repletion:

whirring projector light,needle hitting

copper thread. Mama heldmy slippery body

to her chest. Mama’s slipperybody on my

chest. She asks if I haveever listened to

+ and –. Grains ofsand flowing through one

another. Every daughtergrain resorbs her

mother grain as firstforeign body. Lives her

whole life with thatinside her.

I later fix “Mona’srepletion” to repetition to

repletion. Mona so nearbursting every line she

erases reconfigures itsgenes to another line.

Every time Mama asks whatI am writing

I only say + and –.

Thefull-length poetry debut by Hajer Mirwali, “a Palestinian and Iraqi writerliving in Toronto,” is Revolutions (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2025), acollection that the back cover writes “sifts through the grains of Muslimdaughterhood to reveal two metaphorical circles inextricably overlapping: shameand pleasure. In an extended conversation with Mona Hatoum’s artwork + and –,Revolutions asks how young Arab women – who live in homes andcommunities where actions are surveilled and categorized as 3aib or not 3aib,shameful or acceptable – make and unmake their identities.” Composed as abook-length suite, this collections weaves and interleaves such wonderful structuralvariety, offering a myriad of threads that swirl around a collision ofcultures, and a poetics that draws from artists and writers such as Mahmoud Darwish,Erín Moure, M. NourbeSe Philip, Naseer Shamma and Nicole Brossard, writing talesof mothers and daughters; and how one self-edits, keeps hidden, and also providescomfort, solidarity. “Yes,” Mirwali writes, as part of the poem “January 23,” “avery good daughter who loves / her motherlands and her God. // A daughter moreor less. // A daughter + and –. // Never the same twice.”