Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 7

August 19, 2025

recently on periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics:

recently at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics: Laura Kerr : Unfixed Readings : Fugue, Fire, Fish ; Buck Downs : How to Be Alone With Someone Else Who Is Also You ; Jessie Jones : Two poems ; Kemeny Babineau : Two poems ; Jérôme Melançon : On the Gaza Poets Society ; Dani Spinosa and Derek Beaulieu : Notes on Visual Poetries in Canada ; Misha Solomon : How Does a Poem Begin? ; Noah Berlatsky : The Absolutely True Origin Story of Spamtoum! ; Jamella Hagen : Four poems ; a review of Julie Carr's Underscore by Jérôme Melançon ; Process Note #61 : Dawn Angelicca Barcelona ; a review of THE WEATHER AND THE WORDS: THE SELECTED LETTERS OF JOHN NEWLOVE, 1963-2003, Edited by J.A. Weingarten by Ken Norris ; Sarah Wolfson : How Does a Poem Begin? ; Michael Sikkema : Contemporary Vispo Conversations : Kate Siklosi, Dani Spinosa and Amanada Earl ; Andrew Brenza : on Sigil Series ; Noah Pitcoff : Five poems ; Miranda Mellis : DRIVE SATISFACTION ; Scott Inniss : On First Looking into Andrew Mbaruk’s Slavespeare: A Brief Interview ; Darby Minott Bradford : How does a poem begin? ; a review of Shannon Webb-Campbell's Re: Wild Her by Kim Fahner ; Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño : Four/Four: The Decapitated Generation : translated by Tristan Partridge ; a review of Cherry Blue's Je ne ferai pas de casse-tête de dauphin by Jérôme Melançon ; two poems by Eva Haas ; J-T Kelly : Short Remarks on More of How to Read the Bible ; ryan fitzpatrick : Some Notes on Being the 2024–25 U of A EFS Writer-in-Residence ; Clint Burnham : from “Sea of Sludge” ; Process Note #60 : Elizabeth Costello : Childhood, Adulthood, Enchantments, Entanglements ; John M. Bennett : JIM LEFTWICH’S LAST BOOK : PIT SWAN & ORBATE WRITING ; Grant Wilkins : Where Does A Poem Come From? How Does A Poem Begin? ; Nicole Mae : Matryoshka and Other Poems ; a review of Aedan Corey's KINAUVUNGA? and Emily Laurent Henderson's Hold Steady My Vision by Chris Johnson ; Kim Trainor : A small quiet voice in the dark: ecocide and lyric poetry ; J-T Kelly : A Conversation with Poet Aaron Poochigian ; Jessica Lee McMillan : Pain in the Reverie: What is a good poem and how does it begin? ; Daniel Borzutzky : HIJ ; Arturo Borja : Four/Four: The Decapitated Generation : translated by Tristan Partridge ; J.A. Weingarten : John Newlove’s Life in Letters: Notes on the Publication of The Weather and the Words: The Selected Letters of John Newlove, 1963-2003 ; Tea Gerbeza : How a poem begins ; Laura Kerr : Unfixed Readings : Resisting Resolution ; a review of Chris Bailey's Forecast: Pretty Bleak by Kim Fahner ;

recently at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics: Laura Kerr : Unfixed Readings : Fugue, Fire, Fish ; Buck Downs : How to Be Alone With Someone Else Who Is Also You ; Jessie Jones : Two poems ; Kemeny Babineau : Two poems ; Jérôme Melançon : On the Gaza Poets Society ; Dani Spinosa and Derek Beaulieu : Notes on Visual Poetries in Canada ; Misha Solomon : How Does a Poem Begin? ; Noah Berlatsky : The Absolutely True Origin Story of Spamtoum! ; Jamella Hagen : Four poems ; a review of Julie Carr's Underscore by Jérôme Melançon ; Process Note #61 : Dawn Angelicca Barcelona ; a review of THE WEATHER AND THE WORDS: THE SELECTED LETTERS OF JOHN NEWLOVE, 1963-2003, Edited by J.A. Weingarten by Ken Norris ; Sarah Wolfson : How Does a Poem Begin? ; Michael Sikkema : Contemporary Vispo Conversations : Kate Siklosi, Dani Spinosa and Amanada Earl ; Andrew Brenza : on Sigil Series ; Noah Pitcoff : Five poems ; Miranda Mellis : DRIVE SATISFACTION ; Scott Inniss : On First Looking into Andrew Mbaruk’s Slavespeare: A Brief Interview ; Darby Minott Bradford : How does a poem begin? ; a review of Shannon Webb-Campbell's Re: Wild Her by Kim Fahner ; Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño : Four/Four: The Decapitated Generation : translated by Tristan Partridge ; a review of Cherry Blue's Je ne ferai pas de casse-tête de dauphin by Jérôme Melançon ; two poems by Eva Haas ; J-T Kelly : Short Remarks on More of How to Read the Bible ; ryan fitzpatrick : Some Notes on Being the 2024–25 U of A EFS Writer-in-Residence ; Clint Burnham : from “Sea of Sludge” ; Process Note #60 : Elizabeth Costello : Childhood, Adulthood, Enchantments, Entanglements ; John M. Bennett : JIM LEFTWICH’S LAST BOOK : PIT SWAN & ORBATE WRITING ; Grant Wilkins : Where Does A Poem Come From? How Does A Poem Begin? ; Nicole Mae : Matryoshka and Other Poems ; a review of Aedan Corey's KINAUVUNGA? and Emily Laurent Henderson's Hold Steady My Vision by Chris Johnson ; Kim Trainor : A small quiet voice in the dark: ecocide and lyric poetry ; J-T Kelly : A Conversation with Poet Aaron Poochigian ; Jessica Lee McMillan : Pain in the Reverie: What is a good poem and how does it begin? ; Daniel Borzutzky : HIJ ; Arturo Borja : Four/Four: The Decapitated Generation : translated by Tristan Partridge ; J.A. Weingarten : John Newlove’s Life in Letters: Notes on the Publication of The Weather and the Words: The Selected Letters of John Newlove, 1963-2003 ; Tea Gerbeza : How a poem begins ; Laura Kerr : Unfixed Readings : Resisting Resolution ; a review of Chris Bailey's Forecast: Pretty Bleak by Kim Fahner ; other features: seeking essay submissions in our "Reconsiderations" and "#FirstRealPoets" series. Originally prompted by Canadian poet Ken Norris, "Reconsiderations" is a series of essays by poets on older poetry titles they consider important. The "#FirstRealPoets" series was originally prompted by Canadian poet Zane Koss, who posed the questions: Who was the first poet you interacted with? While some of the responses have leaned into first discovering the work of a particular poet, the original question wished more to ask about interactions in-person. Was there a poet who read in your high school? Someone you caught early on at a reading? Was there a particular poet who first made you feel welcome in the community?

coming up: Farah Ghafoor : How does a poem begin? ; Laynie Browne : on Daily Self-Portrait Valentine ; Laressa Dickey : Four poems from THE LUNATIC SPEAKS TO US DIRECTLY, a manuscript in progress ; Nada Gordon : on COPIUM, …or…The Audacity of Dope ; Kim Fahner reviews Paula Eisenstein's Flight Problems: The Amelia Earhart Poems and Rebecca Salazar's antibody ; Holly Loveday : Three poems ; etc

be aware that periodicities is perpetually open to submissions of previously unpublished poetry-related reviews, interviews and essays . Please send submissions as .doc with author biography to periodicityjournal@gmail.com

August 18, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Matthew Nienow

Matthew Nienow’s

recently released collection,

If Nothing

(Alice James Books, 2025), has been recommended by the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post Book Club, and Poetry Northwest. He is also the author of

House of Water

(Alice James Books, 2016) and three earlier chapbooks. His poems and essays have appeared in Gulf Coast, Lit Hub, New England Review, Ploughshares, and Poetry, and have been recognized with fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Artist Trust. He lives in Port Townsend, Washington, with his wife and sons, where he works as a mental health counselor.

Matthew Nienow’s

recently released collection,

If Nothing

(Alice James Books, 2025), has been recommended by the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post Book Club, and Poetry Northwest. He is also the author of

House of Water

(Alice James Books, 2016) and three earlier chapbooks. His poems and essays have appeared in Gulf Coast, Lit Hub, New England Review, Ploughshares, and Poetry, and have been recognized with fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Artist Trust. He lives in Port Townsend, Washington, with his wife and sons, where he works as a mental health counselor.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m not sure my first book did change my life, though it perhaps coincided with a volatile period in which I did go through some very big changes. I can’t say for sure from this distance, but I likely held some hope that my first book was going to somehow open doors (to where, I don’t really know). All in all, the response was quiet, and this was one of several elements of my life that contributed to a deepening depression and addiction. My drinking, which was already problematic, got worse and worse, and I dove straight to the bottom and stayed there for some time.

When I finally began to get sober eight years ago, it took a great deal of time to get healthy enough to begin writing. Making If Nothing changed me. By going back to the source of pain and betrayal again and again with a hunger for honesty, I had to grow my capacity to be with the parts of myself I couldn’t bear. By doing this, I became more coherent, more resilient, and much more available to my family and friends. Until writing the poems that make up this new collection, there had always been a faint veil between my daily life and my poems. This book erased that separation for me and I haven’t fully metabolized what this means in the larger scope of my life.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I struggled with writing until I was about 20 years old when I took my first creative writing class. It was then that I was first introduced to living poets. Prior to this time, it was epically difficult for me to get even a single page out and my essays and assignments were always far shorter than the stated requirements. So, the fact that I found a life in writing was quite surprising. The typical brevity in poetry, though, really makes sense with that in mind.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to bristle at the word “project” when it comes to poetry, though I do understand it as a guiding concept. (More on this in the next question.)

I don’t take notes, but I do revise voraciously, often experimenting with significant changes in form and lineation. It is rare that my finished poems closely resemble their origins. As sound is really important to me, I often record the poems I am working on and listen to them while throwing the ball for my dogs, so I can check what is resonating and what falls flat. This often helps me take the work to the next level.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I consider reading an active part of my writing process; most of my poems begin in the space of reading. I’m looking to be knocked off-kilter, to be stunned away or lulled into a trance. It is in this interstitial space that I can follow the trail of something I can sense, but not yet see clearly.

I tend to draft without a book in mind, which means it can take a great deal of time before I begin to feel something larger growing up between and around the poems. When I do have a critical mass of sorts, I begin to hone myself towards this space without being overly restrictive. It still requires a great deal of patience and the willingness to write a lot of poems that will never leave my desk.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I see readings as adjacent to my creative process. I don’t write towards readings and I am rarely inspired to write by attending readings. With that said, I love doing readings and have devoted a lot of energy to the art and skill of reading and presenting well. It’s always sad and confusing to me how so many poets who make incredible work on the page read in such a dull or off-putting manner. As sound strongly guides me in making and revising my work, I can’t understand how poets who don’t read well relate to their art.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

This is constantly evolving for me. What I can say is that I see poetry as a place to encounter and wrestle with Truth, in all its varied forms. I am probably most interested in what this means in relation to the human experience. As for questions, I favor the asking over answering. One of the questions I’m currently interested in is: “What is healthy masculinity?”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Though they are nearly unavoidable, I think “shoulds” are often limiting and unhelpful expectations. I do, however, have opinions on what the “best” writing might be doing in the world, which is, of course, closely linked with the role of the writer. In the broadest sense, I believe good writers help us to look more closely at the world and ourselves, providing a chance to know and understand and feel the world more deeply.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I think it depends on the editor. For the most part, I am open to feedback, though I have worked very hard to develop and trust my own internal editor. I’m very lucky to have had both of my books with Alice James; they believe in collaborating with poets and the poets have final call on editorial guidance.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

No one does their most important work alone.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

For much of the last twenty years, I kept a pretty consistent practice of starting my day by reading poems and then drafting something new. If time and interest allowed, I could spend anywhere from 30 minutes to four hours revising work later in the day.

I entered a new chapter about two years ago when my older son got me into strength training. Now, I am at the gym first thing about six days a week, which has all but eliminated my decades-long struggle with anxiety. I’ve become more flexible with my writing practice, and now read and write at other times in the day, though I do believe setting a consistent schedule will help me dig in more fully with new work.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Almost always to the poems of others. If I can’t find something new and surprising in one of the many lit mags I subscribe to or read online, I turn to the favorites in my home poetry library.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cedar and salt water.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’m also a musician and woodworker, and these have influenced my writing. More so, I find that paying attention to what is happening in my life and the world at large tends to inform the poems I make. Fatherhood and marriage are at the core of my life and so these relationships are sometimes the most significant guiding forces.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Larry Levis, Natalie Diaz, Eduardo C. Corral, and Jack Gilbert are some of my favorite poets, though I read widely and am often very taken with single poems from too many poets to name.

Lately, True and False Magic by Phil Stutz has been helping me to grow and move beyond my self-limitations in all areas of my life. It’s an easy read with profound and accessible lessons, but the work of integrating these practices is lifelong work.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I have too many hobbies and passions and I know more will be on the way. With that said, I have been a musician and songwriter since the age of 14. I continue to draft songs all the time, but I almost never prioritize completing or recording these. I’d love to actually make an album I’m proud of even if it is just for me.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve already gone down the rabbit hole on several other careers (boat builder, woodworker, educator, therapist) and many of these continue to be present in my life alongside writing. There were times when I wanted only to be a writer, but I think I do my best writing when I have some friction from another occupation (or two). It keeps the world moving and I have to really choose to make it the page with a bit more urgency.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

As someone who also creates in other forms, I go to writing for a certain flavor of magic I find most strongly there. It may also be true that I am most able to finish what I start when it comes to writing. As noted above, my song drafts often remain unfinished and it isn’t always for lack of trying.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book: This is Happiness by Niall Williams. The last great film… To be honest, I spend more time watching shows than movies and a lot of it is entertaining fluff. I enjoy it, but I wouldn’t call it great.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Finishing a sauna and building my therapy practice. As for writing, I’m leaning into essays about a range of topics around healthy masculinity, fatherhood, ADHD. I’m also drafting poems without any specific aim.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 17, 2025

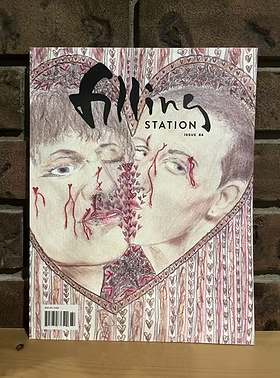

filling Station #84 : let slip the dogs

Hey America, How Are YourStones?

Sometimes the bicycleswirl of a landscape unfurls hot

butter – edge – white –wax – smear – mushed

into cloud // there’s a mountain out there

catches the eye even froma semi

barrel-rocket of goodsboxed into a flare jean

the urgency makes yousolution-oriented

//

Every time you leave likea video game (Meredith MacLeod Davidson)

Ithas been a while since I’ve more regularly discussed an issue of Calgary’slegendary literary journal filling Station [see my review of #83 here;my review of #81 here; see my review of #57: showcase of experimental writing by women here, etc], but I am trying to get better at it. Did you see all theposts up at The Typescript celebrating filling Station’sthirtieth anniversary? Thirty years is a long time for a journal, despite thehandful of journals that have made it far longer (Arc Poetry Magazine iswell over one hundred issues, for example), but always worth acknowledging abirthday, especially for a journal founded by scrappy youths passionate aboutexperimental writing, and producing a journal that has continued entirely withthat founding aesthetic. Yes, I said it: filling Station is and alwayshas been run by scrappy youths passionate about experimental writing, both inCanada and well beyond. Built with their usual array of “poetry, fiction,non-fic, review, interview, project, art,” filling Station #84 providesa showcase of established and emerging, some of whom I know well and others I’venever heard of. Virginia-born Scotland-based Meredith MacLeod Davidson, forexample, is a poet entirely new to me through these pages, as is Northern Ontario poet Erin Wilson [although a quick search provides that I actually interviewed her two years ago], who has two poems in this particular issue, includingthe poem “Tenebrae,” that begins:

The watering can beadswith rain.

Slugs slowly ruin the gibbousrind of the pumpkin.

Put your black nylonsocks on your cold black feet.

Think think think, charcoal,in darkness.

Further,there’s Calgary-based poet, fiction writer and editor Chimedum Ohaegbu, and herpoem “Culpable, Too, the Minutes,” that begins: “My innocence on the abacus /although you’ve already deemed me / wolf. Courtroom drama / as directed by Internetquestionnaire: / How often do you feel seen?” Otherwise, I think everyoneshould be reading the work of Montreal poet Misha Solomon (who has a couple ofchapbooks out, with a full-length poetry debut out next year, you know, with BrickBooks), or Brooklyn-based Canadian poet Michael Chang [see my review of their latest here], both of whom have new work in this particular issue. Or there isToronto writer Sneha Subramanian Kanta, with the three-stanza/paragraph piece “Three BrokenSonnets: Escape Room City,” a lyric and narrative swirl of layer upon layer thatincludes: “Two cups of hot chocolate arrive in / ceramic glasses like we weredrinking a warm beverage in the home / of a friend. No one befriends another inthis city because they don’t / have time. The evening streets are quiet althoughhours are porous. / I have begun to understand the concept of time as not beingfinite.” As ever, if you wish to know what is happening on the ground when itcomes to contemporary writing, one could not do much better than payingattention to the little magazine, and filling Station (alongside

The Capilano Review

,

Geist

and

FENCE magazine

) remains high on mylist.

Further,there’s Calgary-based poet, fiction writer and editor Chimedum Ohaegbu, and herpoem “Culpable, Too, the Minutes,” that begins: “My innocence on the abacus /although you’ve already deemed me / wolf. Courtroom drama / as directed by Internetquestionnaire: / How often do you feel seen?” Otherwise, I think everyoneshould be reading the work of Montreal poet Misha Solomon (who has a couple ofchapbooks out, with a full-length poetry debut out next year, you know, with BrickBooks), or Brooklyn-based Canadian poet Michael Chang [see my review of their latest here], both of whom have new work in this particular issue. Or there isToronto writer Sneha Subramanian Kanta, with the three-stanza/paragraph piece “Three BrokenSonnets: Escape Room City,” a lyric and narrative swirl of layer upon layer thatincludes: “Two cups of hot chocolate arrive in / ceramic glasses like we weredrinking a warm beverage in the home / of a friend. No one befriends another inthis city because they don’t / have time. The evening streets are quiet althoughhours are porous. / I have begun to understand the concept of time as not beingfinite.” As ever, if you wish to know what is happening on the ground when itcomes to contemporary writing, one could not do much better than payingattention to the little magazine, and filling Station (alongside

The Capilano Review

,

Geist

and

FENCE magazine

) remains high on mylist.

August 16, 2025

above/ground press author spotlights : substack,

Over at the above/ground press substack [free to sign up for and free to leave] I've been posting a series of interviews with above/ground press authors with multiple titles through the press [as above/ground press authors with only a single title often get covered in the essays posted over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics] with new interviews posted so far with Amish Trivedi, Brook Houglum, Orchid Tierney, Jason Christie, Steph Gray, Monty Reid and

Lydia Unsworth

, with further interviews scheduled with Micah Ballard, Nathanael O’Reilly and Michael Sikkema, and even further interview currently-in-progress (as well as new titles forthcoming) with Ben Ladouceur and Renée Sarojini Saklikar. Click the links to see the posted interviews so far, and even sign up to catch what might come next! The next few months of above/ground press really does have some exciting material coming through. And be sure to watch in a few weeks for the announcement for 2026 subscriptions!

Over at the above/ground press substack [free to sign up for and free to leave] I've been posting a series of interviews with above/ground press authors with multiple titles through the press [as above/ground press authors with only a single title often get covered in the essays posted over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics] with new interviews posted so far with Amish Trivedi, Brook Houglum, Orchid Tierney, Jason Christie, Steph Gray, Monty Reid and

Lydia Unsworth

, with further interviews scheduled with Micah Ballard, Nathanael O’Reilly and Michael Sikkema, and even further interview currently-in-progress (as well as new titles forthcoming) with Ben Ladouceur and Renée Sarojini Saklikar. Click the links to see the posted interviews so far, and even sign up to catch what might come next! The next few months of above/ground press really does have some exciting material coming through. And be sure to watch in a few weeks for the announcement for 2026 subscriptions!August 15, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ashley D. Escobar

Ashley D. Escobar is a literary angel fromSan Francisco, residing in New York City. Eileen Myles selected her debutpoetry collection

GLIB

(2025) as the Changes Book Prize winner. She is a highschool dropout who graduated from Bennington College and holds an MFA in fictionfrom Columbia University. She is a proud outpatient at the teenage art ward.

Ashley D. Escobar is a literary angel fromSan Francisco, residing in New York City. Eileen Myles selected her debutpoetry collection

GLIB

(2025) as the Changes Book Prize winner. She is a highschool dropout who graduated from Bennington College and holds an MFA in fictionfrom Columbia University. She is a proud outpatient at the teenage art ward.1 - How did your first bookor chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook SOMETIMES guided methrough the pandemic. My long-distance friend Kendall and I wanted to trywriting a poem a day for a month and it was October and I drove my mom’s creamMini Cooper in circles trying to decipher if this would ever come to an end. Itwas a period of unrequited longing. California ennui. It’s influenced a lot byBaudelaire and Cortázar and long pensive walks alone by the beach. I don’t havethat same privilege of long days spent looking out onto the ocean, but I try toaccess that inner meditative state despite the chaos of New York. It’s strangebecause I was younger, yet one of the poems, “Beachcomber,” that made it intomy debut collection GLIB has been remarked as more “mature.”

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I think poetry just comes naturally to everyone,especially as a child learning to string words together. I never stoppedplayfully stringing words together. Fiction requires more focus and sittingdown to finish a single scene, whereas in poetry, you can leap into infiniteworlds in a few stanzas, even between a few words. I love the liminality andopen endlessness that poetry offers.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Regarding poetry, I never knew SOMETIMES orGLIB were necessarily going to become a manuscript. The poems werecollected throughout a certain period of my life. My writing usually comesquickly, and the initial drafts usually are quite similar to the final shape,give or take a few word changes or removing scaffolding. It was interestingreshaping a few poems in GLIB that I would have never thought about ifit weren’t for my editor Kyle Dacuyan. I think the words are usually alreadythere but playing with form can sometimes transform the poem into somethingelse.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I usually think of a line and go from there. Icollect a lot of my poems in an ongoing document, and I came to a naturalstopping point with GLIB where I felt like I had archived enough of aspecific era of my life to turn it into a book.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I’ve grown to enjoy readings since moving to NewYork City. It’s cool to see what the audience reacts to, especially when it’s anew poem I haven’t shown anyone yet. I’m in awe of my boyfriend Matt Proctorwho always reads something new at every reading. I feel restrained to readingthe “hits” at certain readings, but I’m getting back into writing poems morefrequently. I’d like to create more youth-centered readings intertwined withmusic, which I’ve done through my zine We Are in the Shop, bringingtogether upcoming artists with established ones in cool places such as Billy’s Record Salon. R.I.P. Billy Jones. He helped bring together some of my favoritewriters and musicians into the same room.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

With SOMETIMES, I was concerned with thedifference between loneliness and solitude. But with GLIB, I wasn’tnecessarily trying to answer question, but a few ideas were naturally broughtup and answered throughout the collection such as “Walking in New York likescrolling the internet.” GLIB examines the multitudes of a persona andhow we’re basically actors in our everyday life, code switching from person toperson. GLIB examines girlhood in a world where its overly commodifiedonline.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I feel like being a writer is only one role toplay alongside being an activist, a lover, a friend. I think of the sign inCity Lights bookstore: “Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angelsin disguise.” Writing is important for not only documenting the culture butshaping it and creating something instead of just reciting what’s fed to us.It’s about making connections within neighborhoods and sparking revolution.

8 - Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Like I said before, I worked with Kyle when hewas at Changes, and it offered a lot of perspective on form that I had neverconsidered before. As long as there’s some common ground, I don’t mind theprocess. It gave me a lot to think about. He was the first one to look at someof the poems I later added in, and I was honestly surprised by the generousfeedback and enthusiasm.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To not wait forpermission!

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to filmmaking)? What do you see as theappeal?

They’re separate in terms of process but I findpure poetry in moving images. At the New York GLIB launch at AnthologyFilm Archives, my boyfriend Matt and I played our cut-up vlogs during our readings. It wasamazing to be in such a historically rich theater.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I have more of a writing routine if I’m writingprose or have a deadline. If not, I’ve been working a lot during the afternoonlately and going out at night. I’ve started working on a longer prose project,so I’ll have to find blocks of time to continue the pace I’d like for it.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I dig into my archives. Listen to songs I usedto be obsessed with. Old diary entries. Old tweets. Old Rateyourmusic.com posts. Anything that reminds meof me. I start writing things down again even if it’s just a to-do list.It turns into something, usually.

13 - What was your lastHallowe'en costume?

I was a bunny Sonny Angel doll and a vampire. Itwas cute, and I read a few poems at Matt’s Easy Paradise open mic and hung outat Tile Bar after.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

It’s mainly music for me. I’ve actually made a playlist for a song accompanyingevery poem from GLIB based on what I was listening to around the time Iwrote it. I’m a very sonic person, and getting lost in a certain song evokes alot of memories and feelings for me that don’t necessarily come out of othermediums as easily. There are a lot of references to songs and musiciansscattered within GLIB. The Clientele, Felt, Now, Weyes Blood, JackKilmer, Bright Eyes, Housekeeping, Horsegirl, and Dear Nora are a few of theartists who directly influenced GLIB.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Alice Notley has been an important guiding forceas of late. R.I.P. to her as well. I feel lucky to be in conversation withMatt, Eileen Myles, Aristilde Kirby, Edwin Torres, Julien Poirier, and Eddie Berrigan. Zines like Eli Schmitt’s Unresolved are important to me. Oldletters mean a lot. I love reading interviews with indie bands. Julio Cortázarand the Beats, especially Jack Kerouac, haunt me always.

16 - What would you like todo that you haven't yet done?

I would like to direct a feature film. I alreadyhave a screenplay called The Lovers III that is a continuation ofMagritte's painting sequence. It follows a young girl, coping with the recentdeath of her mother and hospitalization, as she runs off to Greece with astranger––an older woman in a baby blue suit. It intertwines the human conditionwith the gaze, desire, and a love of art. I would also love to be in a band,even if it’s a Pastels cover band. I’d love to sing and play tambourine! I canplay guitar, too.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would love to open my own restaurant, imaginea tiny bistro in Paris where we play cards in the back room. Or a bookstorecafé that turns into a wine bar at night. I’d love for it to be a place thatmerges gastronomy with literature and music. Without being pretentious. I wouldnot like it to be recommended on TikTok. It would have to be undergroundenough.

If I was not a writer, I would be a fashiondesigner. I love vintage clothing and going thrifting. There’s a reference in GLIBto the “fish pants” I made when I was sixteen. Also be in a jangle-pop bandbut that’s possible. Please reach out. I love K Records.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

It’s something I can do without any budget orplanning. I can turn to my notebook or computer rather than go out and extramaterials or wait around for approval. I love playing cinematographer, artdirector, and the lead role without a film crew. I also can’t help it.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Can I speak about the last two records I lovedinstead? Now Does the Trick, the latest from Now, is immaculate glampop. Glimmering music to dance to. Each song is a poem. They hold a specialplace in my heart, especially when I’m away from the fog. Radio DDR bySharp Pins has also been on repeat. Pure pop pleasure. I love Kai’skaleidoscopic world of layers and layers of sound and color, fuzz and janglyguitar. Long live the youth musik revolution.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I’m currently working on an ongoing book-lengthprose poem that I like to call my “one-sentence novel.” It blurs the boundariesbetween genres, grammar, and cultural eras. The poem questions the presence andpurpose of the “I” in writing through recollections, overheard dialogue, andinteractions between memory and art, reality and the imagined. As well as anovella about a girl swept in Christmas.

If anyone wants an irreverent novel set in Berlin about a19-year-old girl who ends up living in her lesbian godmother’s bookshop mixedwith rowdy boys and Joë Bousquet, please email me. I am also pitching around mysemi-autobiographical short story collection Have a Pepsi Disappear.Think Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles meets Eve Babitz. It’s a love letterto California, underage cocktails, and above all, poetry.

August 14, 2025

Cedar Sigo, Siren of Atlantis

Ode to The Hi-way House

OK calm down, let’s alsosay

there is no need to writeanything down for a while,

Let’s think back on allthe poets that may have flirted in this room

or fucked or tried to ormet often, in semi secrecy several times a week.

For now, I feel silencedby the everyday I have already told you,

diseased and purposelykept form new love and old.

And then Margaret dreamtthat she and Barbara

drove back-up through thedesert 900 miles

to leave cooked food infront of room 217. I call Lydia to say that Kazim

is teaching a wholeNaropa summer course on Yoko Ono.

I hope this means aretelling of the Chambers Street

concert series withJackson Mac Low.

This constructed attempt atpoverty so chic I can forgive.

Especially if real poetswere there as specimens taking part.

Any other poets that mayhave collapsed halfway down the hallway

of the archive? The onesthat barely made it.

They make the rest of ussmell so sweet; it becomes unreal.

Thelatest from Lofall, Washington-based poet and member of the Suquamish nation, Cedar Sigo, following titles such as

Stranger in Town

(San Francisco CA: City Lights,2010),

Language Arts

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014),

Royals

(Wave Books, 2017),

All This Time

(Wave Books, 2021) [see my review of such here] and

Guard the Mysteries

(Wave Books, 2021), is

Siren of Atlantis

(Wave Books, 2025), a collection assembled as an ongoingaccumulation, akin to a day-book of lyrics held together across a particularstretch of attention. “I toss my stencils / to the neon fire and begin tobuild, / stacking obsidian dust,” he writes, to open the poem “STRANGER (FULLTEXT) #2,” “a text that betrays the shape of a tone, / a semblance of pitch, /the opposite of rubbing down / onto a headstone.” Referencing poets such asBernadette Mayer, Clark Coolidge, Wanda Coleman, Joanne Kyger (Sigo editedKyger’s There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera for Wave Booksback in 2017, don’t you know) and Kazim Ali, Sigo composes a book of echoes andof the everyday, keeping a regular writing practice of his immediate, from hisreading and recollections of mentors and the immediacy of his peers, dystopianperil and climate crises, and a very present and particular sense of time. “Laymy figures bare / and give them no rest,” offers the short poem “THE LIFE OFSUN RA,” “I can relate to his premise, that he was born on Saturn // and mustbe getting back soon, // that the earth is a failed planet, // that rehearsalitself / becomes a ceremony.”

Thelatest from Lofall, Washington-based poet and member of the Suquamish nation, Cedar Sigo, following titles such as

Stranger in Town

(San Francisco CA: City Lights,2010),

Language Arts

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2014),

Royals

(Wave Books, 2017),

All This Time

(Wave Books, 2021) [see my review of such here] and

Guard the Mysteries

(Wave Books, 2021), is

Siren of Atlantis

(Wave Books, 2025), a collection assembled as an ongoingaccumulation, akin to a day-book of lyrics held together across a particularstretch of attention. “I toss my stencils / to the neon fire and begin tobuild, / stacking obsidian dust,” he writes, to open the poem “STRANGER (FULLTEXT) #2,” “a text that betrays the shape of a tone, / a semblance of pitch, /the opposite of rubbing down / onto a headstone.” Referencing poets such asBernadette Mayer, Clark Coolidge, Wanda Coleman, Joanne Kyger (Sigo editedKyger’s There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera for Wave Booksback in 2017, don’t you know) and Kazim Ali, Sigo composes a book of echoes andof the everyday, keeping a regular writing practice of his immediate, from hisreading and recollections of mentors and the immediacy of his peers, dystopianperil and climate crises, and a very present and particular sense of time. “Laymy figures bare / and give them no rest,” offers the short poem “THE LIFE OFSUN RA,” “I can relate to his premise, that he was born on Saturn // and mustbe getting back soon, // that the earth is a failed planet, // that rehearsalitself / becomes a ceremony.”Part-waythrough the collection, Sigo introduces the following pages with a note thatbegins: “I suffered a stroke in late July of 2022. As I was reentering mybody, I decided to try writing poetry again (I was still endlessly flippingfragments in my head and reorganizing them.) The following poems seemed to comeout as a series of exhibits, a naïve garden that I forced myself to connectinto something larger. It is a gift to be reintroduced to your practice.”It is interesting to think of the journey, the distance, the author travelled tocompose these pieces, held in similar foundations to what I’m already aware ofhis work. One might suspect that the experience, as he suggested in his note,forced a return to the foundations of how he approaches writing, and approachesthe poem, something that perhaps someone far more familiar with his ongoingwriting should probably delve into with more detail. Either way, these poemsare remarkable, and deeply grounded, held in the hand as a bird might trust tolight, while able to take wing at any moment. As one of the poems that followshis short note, “MEMORIZATION SONNET,” begins: “The common vernacular is ourmovement / and should never be reduced to echoes of voice.”

August 13, 2025

Jeff Derksen, Future Works

Obsolete cold-war navydolphins write algorithms that design an

app to do the laundry foroveremployed people.

Dung beetles,decommissioned from nature documentaries,

collectively lugoverweight luggage into the cargo bays of

discount Europeanairlines.

The bats who took ashort-term contract to patrol a new condo

construction site atnight to thwart theft from “the midnight

lumberyard” are injuredwhen the beam they hang on to take

their break collapses.

Metallica replaces theirdrummer with an octopus from Vigo,

Spain, who learned heavymetal on the sides of ships they

once riveted on the waterfront.

Acrobatic barn swallowsdust the penthouses of oligarchs,

poetically catching eachmote in the air.

Turf wars break outbetween European and Chinese praying

mantids; the deadlysquabbles end through negotiations by

unemployed European parliamentarianswho lost their jobs

when elected politicalpositions were opened to all species.

(“MORE THANHUMAN LABOUR”)

Verygood to see a copy of

Future Works

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2025), thelatest poetry title by Jeff Derksen, a poet, critic and professor who currentlydivides his time between Vancouver and Vienna, Austria, and who emerged acrossthose heady days of 1970s and 80s language-exploration through and around The Kootenay School of Writing (originating in Nelson, British Columbia’s David ThompsonUniversity Centre, relocating to Vancouver when the government shut DavidThompson down in 1984), blending language experimentation with and throughsocial and political commentary. Following poetry titles including

Until

(1987),

Down Time

(Talonbooks, 1989), Dwell (Talonbooks, 1994),

Transnational Muscle Cars

(Talonbooks, 2003) and The Vestiges (2014) [see my review of such here], Derksen’s Future Works offers a heft of referencesand lines and commentaries stitched together as a rush of a shape, a coherentmass of accumulated texts that form the structure of his poems. “Ants closedown the North American banking system with / a highly coordinated strike on ATMs:over New Year’s Eve, / individual bills are carried out of the machines,” hewrites, as part of the extended opening poem, “MORE THAN HUMAN LABOUR,” “moved along/ predetermined routes, and stashed in complex underground / networks. Two antsare captured but refuse to five up their / comrades. In solidarity, they eateach other.” More power in union, one might say.

Verygood to see a copy of

Future Works

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2025), thelatest poetry title by Jeff Derksen, a poet, critic and professor who currentlydivides his time between Vancouver and Vienna, Austria, and who emerged acrossthose heady days of 1970s and 80s language-exploration through and around The Kootenay School of Writing (originating in Nelson, British Columbia’s David ThompsonUniversity Centre, relocating to Vancouver when the government shut DavidThompson down in 1984), blending language experimentation with and throughsocial and political commentary. Following poetry titles including

Until

(1987),

Down Time

(Talonbooks, 1989), Dwell (Talonbooks, 1994),

Transnational Muscle Cars

(Talonbooks, 2003) and The Vestiges (2014) [see my review of such here], Derksen’s Future Works offers a heft of referencesand lines and commentaries stitched together as a rush of a shape, a coherentmass of accumulated texts that form the structure of his poems. “Ants closedown the North American banking system with / a highly coordinated strike on ATMs:over New Year’s Eve, / individual bills are carried out of the machines,” hewrites, as part of the extended opening poem, “MORE THAN HUMAN LABOUR,” “moved along/ predetermined routes, and stashed in complex underground / networks. Two antsare captured but refuse to five up their / comrades. In solidarity, they eateach other.” More power in union, one might say.Publishedmore than a decade after his prior collection, Future Works is assembledwith an opening selection of poems that take up two-thirds or so of the book,as well as a second section of poems, titled “URBAN TREES.” There’s playfulnessto Derksen’s serious poems, one with a wry glance across what might otherwise seemserious, dark or even absurd. “I was working in a gas station,” the prose piece“MY SHORT NOVEL” begins, “a greenhouse, in delivery, in gardening, in editing,in teaching, in administration. The weather has a new name and it is no longeradorable.” The distance of time since his prior collection was published offersa slightly different perspective on his ongoing work, providing a reminder at justhow much the structure and poetics of Canadian (Calgary, Vancouver, Toronto,Edmonton, Calgary) poet ryan fitzpatrick’s work really has evolved and beeninfluenced by poets such as Jeff Derksen [see my review of ryan fitzpatrick’s latest collection here], both poets presenting moments and meaning through thecontext and collision of moments and references into and across each other; howideas of capital, labour, language and capitalism relate and interrelate acrosslayerings and collage of direct statements. “My hard edge paintings / are alist / of demands,” begins Derksen’s poem “MY HARD EDGE PAINTINGS, a poem subtitled“after Pierre Coupey,” “or plans where colour / rushes into / ourkinetic future / on a hard-to-observe land / to so-called light / upon in theshadows / under the cover / of canvas, an advance / like walking out / into thecity [.]” There is a curious way that Derksen’s approach engages ethics andperspective, offering an alternate way of realizing the lyric, one that speaksof late capitalism and global war zones, future climate catastrophes andcontemplative wit across what might otherwise appear as a collage ofreferences, laid end to end, built to produce something far larger and ongoing.“or the most beautiful thing / may be the space you make / it as you imagine it/ conceived built inhabited altered,” he writes, to close the poem “THE MOST BEAUTIFULTHING,” “by an encounter that swerves / to what is possible / an act an action/ an unscripted learning [.]”

August 12, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Danielle Vogel

Danielle Vogel is a poetand interdisciplinary artist working at the intersections of queer and feministecologies, somatics, and ceremony. She is the author of the hybrid poetrycollections

A Library of Light

(Wesleyan University Press2024),

Edges & Fray

(Wesleyan University Press 2020), The Way a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity (Red Hen Press 2020),and

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press 2015).Vogel’s installations and site responsive works have been displayed atRISD Museum, among other art venues, and adaptations of her work have beenperformed at such places as Carnegie Hall in New York and the TjarnarbíóTheater in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Danielle Vogel is a poetand interdisciplinary artist working at the intersections of queer and feministecologies, somatics, and ceremony. She is the author of the hybrid poetrycollections

A Library of Light

(Wesleyan University Press2024),

Edges & Fray

(Wesleyan University Press 2020), The Way a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity (Red Hen Press 2020),and

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press 2015).Vogel’s installations and site responsive works have been displayed atRISD Museum, among other art venues, and adaptations of her work have beenperformed at such places as Carnegie Hall in New York and the TjarnarbíóTheater in Reykjavík, Iceland.Vogel is committed to anembodied, ceremonial approach to poetics and relies heavily on field research,cross-disciplinary studies, inter-species collaborations, and archives of allkinds. Her installations and site-responsive works—or “ceremonies for language”—areoften extensions of her manuscripts and tend to the living archives of memoryshared between bodies, languages, and landscapes.

Born in Queens, New York, andraised on the South Shore of Long Island, Vogel earned a PhD in literature andcreative writing from the University of Denver and an MFA in creative writingand poetics from Naropa University. She is currently associate professorat Wesleyan University where she teaches workshops in experimental poetics,investigative and documentary poetics, ecopoetics, hybrid forms, memory andmemoir, the lyric essay, and composing across the arts.

Vogel lives in the ConnecticutRiver Valley with her partner, the writer and artist Renee Gladman, where shealso runs a private practice as an herbalist and flower essence practitioner.Learn more at: https://www.danielle-vogel.com/

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When Carmen Giménez andNoemi Press picked up Between Grammars for publication back in 2015, after the initial immense joy andgratitude, I was flooded with an intense fear of being seen in a new way. I wasestranged from my family and felt that the published book-object would be a rawextension of my own form, a conduit through which they would have access to mein a way that filled me with a kind of terror. This fear became conflated with afear of the reader, a reader who might possibly not like the book.

When Between Grammars came out, I had to really ground myself in a newkind of poetics, one that included “the audience” in a way I hadn’t had toconsider before. I was no longer a poet without a book. And this book, BetweenGrammars, was a book about a book. About an author being met by areader through the unique and intimate ecosystem a physical book-object cancreate. I had to transmute that fear into intention. And this intention ispresent in each of my subsequent books: how can the book become a haven for myown story and the reader’s? This question is, in varying forms, at theroot of all of my collections.

A Library of Light, published nearly ten years later, is very directly about myfamily and maternal lineage, my motherline, as I say in the book. Thatfear, which grew from estrangement, that I mention above became a kind ofchapel I climbed inside of to write this book.

2 - How did you come to hybrid writing, as opposed to, say, a stricterdelineation of literary forms?

Honestly? Through the linernotes on a Bob Dylan album called, Desire. When I was 19 or 20, I pickedup this album from some hole-in-the-wall record shop in Manhattan. On theinside sleeve, the envelope that holds the LP, is a lyric essay, “Songs ofRedemption,” about the album written by Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg’s signaturesays:

Allen Ginsberg

Co-Director

Jack Kerouac

School

of Disembodied

Poetics,

Naropa Institute

York Harbor, Maine

10 November

1975

I was like, hmmm, I know and love Ginsberg’s work and I’m totallydisembodied and I’m sort of a poet, what the heck is Naropa Institute? Itwas the early days of the internet, so I was able to find Naropa’s website,which was, by then, a university in a state (Colorado) I had never in my younglife considered moving to or even visiting. I knew I needed to leave home if Iwas going to survive my life. I requested an application, applied (in fiction),was accepted, settled in Boulder, and within a few weeks had met the phenomenalAnne Waldman and felt safe enough to come out as a lesbian. It was at Naropathat I was introduced to hybrid writing, book arts, and where I met and studiedwith writers like Akilah Oliver, Cecilia Vicuña, and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge,among endless other luminaries of hybrid and experimental forms.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I work like a birdbuilding her nest. But instead of that nest being built fairly quickly, as thebird must lay her eggs, my nests often take around a decade to be plaited intotheir final and sustainable forms.

4 - Where does a poem or hybrid text usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Each of my texts begin with a question glowingat its center. If tended, this question acts as guiding and organizing force. Inever want to answer this question, only live with it devotionally letting mydays and manuscripts be sculpted by the ceremony. Because I think of the bookas a ceremonial container, a place within which a kind of transformation cantake place, I am always working on “a book” or “a ceremony” from the verybeginning.

I tend to write book-length poems or hybridmeditations. Often these are composed of a series of longer pieces. Althoughright now, I’m working on brief “veils,” “visions” and “drifts” in two of mymanuscripts-in-process. I let the project shape itself through the ceremony ofongoing attention.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I would say publicreadings are neither a part of nor counter to my creative process. But because,ideally, the book-as-intimate-object is central to all of my collections, Ioften wonder what is lost (or activated) when I become, in a way, the bookembodied or the object at a remove, not in the hands and minds andbreathing bodies of my readers.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

Oh, yes. As mentionedabove, each of my books has a question glowing at its center. Some of myearlier questions were: What is language’s relationship withtrauma and embodiment? (for TheWay a Line Hallucinates Its Own Linearity) What is my responsibilityas a weaver of books, of habitations, for the bodies of others? (for Edges &Fray) If light had a translatable syntax, what would it be? (forA Library of Light) While those will always resound through my writing, oneof the questions I am holding close now is: What happens when we returnlanguage to Land, when we invite Earth into our bodies, when we remember thatlanguage weaves us (by way of breath, light, and consciousness) with others,with place?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

To remember. To weave. Ina time when many are hopelessly and infuriatingly watching the devastatinglive-streaming of multiple genocides, particularly of the Palestinian people,their homeland and ecosystems, it is more important than ever that we find waysto remember. What needs to be remembered is a very individual question.But that we, as artists, find ways to remember our shared humanity, ourconnection with lineage, place, language, one another, especially acrossdistances and differences, feels vital.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I love the editor/authorrelationship and have been blessed by working with Suzanna Tamminen of Wesleyan University Press for my last two collections. She understands my work on acellular level and her editorial advice, instead of being line-based orstructural, is often what I think of as essential energy based. It’s asif she’s reading the vibrational field of my collections. She gives me thatlevel of editorial advice, which has been essential to my editorial rituals atboth macro and micro levels.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Give your body whatit needs. Told to me very recently by the brilliant poet and astrologerSara Renee Marshall. I needed that reminder, especially in this time ofpolitical overwhelm where the powers that be are trying to flood and disorientus. As an herbalist and professor/mentor, I’m always helping others findbalance and nourishment in how they tend to their creative projects and living.I can forget to turn that care and attention toward myself.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (hybrid writingto installation)? What do you see as the appeal?

My practice has alwaystaken place both on and off the page. It is what my manuscripts and theirquestions necessitate of me. Each of my manuscripts have in-the-field companionprojects through which I explore the core concerns and mysteries of amanuscript. These are often ephemeral, durational, private, and site-responsiveworks. Because so much of my work, once published, has to do with my devotionto reintegrating a reader within their inner and outer environments, I seeinstallation or any of the work I do off the page as essential. My hope isalways to activate both inner and outer terrains, the visible and invisible,the conscious and subconscious, the known and unknowable and to bring them intosymbiosis. Right now, a lot of that work is made manifest through mycollaborations with plants and with/in herbals.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

On a day when I don’thave to be on campus or go somewhere, I like to wake early. I press my herbalinfusion that I always set to steep overnight before heading up to bed, pour aglass, and sip it as a kind of morning prayer. Renee makes us a moka pot ofcoffee. Then I’ll light a candle and get to some kind of creative work for afew hours. Maybe I write. Edit photos. Blend client formulas. Then we oftenclose the morning’s work with a family hike in the woods. And then we come homeand cook a beautiful meal.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Each of my manuscriptshas a journal or a series of journals within which I’ve traced the evolution ofits central question or intention. I think of these journals as living altarsfor the book. I always return to the beginning. Tend the altar. Relight thetaper of the earliest question. And see what rises in the glow of that renewedintimacy.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Shallots and garlicsauteing in a rich extra virgin olive oil. Wild roses. Sandalwood.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Oh, yes! I can’t helpbut think here of The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard. Everythingfrom a cupboard to a nautilus shell to the contracting spiral of DNA to abird’s nest to a crystalline grain of pollen. In terms of A Library of Light,I held the drawings of Emma Kunz, Swiss healer and researcher, close over thedecade of writing. Epigenetic theory and the science of biophotonics were alsocentral avenues of research while I was writing the collection. I’m also anherbalist and flower essence practitioner and what I learn about poetry as ahealing modality through my ongoing collaborations with plants are at the rootof a lot of what I compose.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I mentioned some of themearlier, but the work and lives and devotions of writers like Cecilia Vicuña, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and M. NourbeSe Philip are incredibly important to me. I’m inawe of what their work, which feels inseparable from a kind of sacred practice,makes manifest. And then there are numerous brilliant friends who I write incommunity with like a. rawlings, fahima ife, Jen Bervin, Carolina Ebeid, Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola (among many others!) and, of course, my love, Renee Gladman.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to meetAntarctica.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

Something in ecologicalrestoration. I’m very moved by the work of United Plant Savers and have oftenfantasized about joining them.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing is essential.It’s kept me alive.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

It was a while ago, butLauren Groff’s Matrix really still has a hold of me. I also can’t stopthinking about the film Petite Maman.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Iwork on many projects at once, but for the last couple of years I’ve beencollaborating with the multidisciplinary artist and director Samantha Shay, herSourceMaterial collective, and the Icelandic musician Sóley on a film project,which has my heart and attention this summer. As a part of that collaboration,I’ve been working on a manuscript tentatively titled Oracle Net, as wellas a lineage of flower and mineral essences that work with/in the text.

August 11, 2025

from the green notebook,

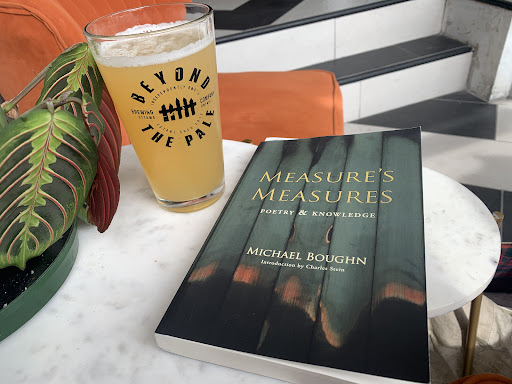

, reading Michael Boughn, Audrey Thomas, Maggie Nelson, Maggie Smith + Vladimir Nabokov

, further (spring 2024) notes from awork-in-progress,

[see multiple other sections from this project over at my substack]

Today is Aoife’s penultimate day of grade two. Rose finishedgrade five last week, and she is currently in Picton with Christine’s fatherand his wife, most likely in their pool as we speak. Christine is laid flatwith a cold, a trickling virus that has tendrilled through the house over thepast few days. It ignores Aoife, and Rose seems to have missed it, but I swatat the potential of impending summer cold with both hands. I will not get sick.

Reading through elements of MichaelBoughn’s new Measure’s Measures: Poetry & Knowledge (2024), I’mstruck by his descriptions of some of those “poetry wars” during and around theperiod of American poetry that developed The New American Poetry (1960).The term “poetry wars” has come up a bit again recently, in reference toconflicts in Prince George, British Columbia a decade or two back, as JeremyStewart and Donna Kane were putting together their folio of poetry and prose tocelebrate the life and work of Barry McKinnon (1944-2023) that I was postingonline at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. Nothing any ofthe three of us wished to re-ignite.

I’ve never been interested inparticipating in wars. Ken Norris used to speak of poetry wars, some of whichhe got caught up with in the 1970s, with a kind of resigned inevitability. As Iunderstand them, most of these conflicts didn’t seem to stem beyond someonesaying something confrontational and others responding, or simply a matter ofdifferent aesthetics falling into the perceived requirement of a personalclash. What does it matter that one person writes a poem in a different way?There is work I am interested in and work I am less interested in; people I aminterested in and people I am less interested in. I think you’d be surprisedhow often those considerations blend into different configurations.

For the longest time, one of my absolutefavourite humans was Toronto writer Priscila Uppal (1974-2018), her early deatha devastating loss for everyone that knew her. A particular favourite spot ofhers in Ottawa was Zoe’s, the bar lounge of the Chateau Laurier, where we’dalways meet up when she came through town. She quite literally glowed withenergy, enthusiasm and creativity, and we were able to support and encourageeach other despite having little overlap, it seemed, in reading or writinginterest. Most of the writers and writing she admired and was influenced by Ihad little to no interest in, so how much could I really appreciate her work,no matter the quality?

There are numerous writers it would belovely to be able to sit down and have a beer with, and conversation; butsomehow, for some, aesthetics prevents us. There is so much that can be learnedfrom alternate perspectives on writing and thinking, and it becomes far tooeasy to fall into our bubbles. Is the goal not to expand our thinking? Is ourgoal not to improve, and make new? Why have a war?

*

Today is Aoife’s final day of grade two.Rose remains in Picton, for at least two more days. She is older, there.

I am moving slowly through final proofsfor these short stories, and thinking about how words get shaped on the page.Simultaneously, I am going through a recent reminiscence by Canadian writerAudrey Thomas on the late Alice Munro, sent out by email newsletter to membersof The Writers’ Union of Canada. Thomas writes of heading to do research inEngland in 1987, and convincing Munro, simultaneously aiming herself toScotland for the sake of her own research, to not fly to Scotland, but to joinThomas by boat. Thomas makes the trip sound delightful enough it almost makesme consider the same. Thomas writes of their sea-faring adventure, the two ofthem learning a handful of daily words in Polish, until a storm at the very endof the trip, upon entering the English Channel.

“I’m sorry it turned out tohave such a terrifying ending,” I said. “I wouldn’t have missed it for theworld,” said Alice.

*

Los Angeles writer Maggie Nelsonreferences Alice Munro as part of The Argonauts (2015). I had pulled thebook from yesterday’s shelves, opened it seemingly at random, and there it was:Munro’s work providing Nelson’s teenaged-self a perspective on sexualexperience, violation, lust “and how such ambivalences can live on in an adultsexual life.” The gift of clarity the greatest one can offer, after all.

I’ve been thinking of Nelson againrecently, having caught inklings via social media that she might have a newtitle either out or forthcoming, which made me curious. Naturally I haven’t yetset down to verify this. I’ve enough other reading in-progress I shouldprobably attend to, first. What of those essays on Sheila Heti and Lydia Davis?But I am curious.

This morning, reading through a recentpoem by Andy Weaver. He was good enough to comment upon my work-in-progresselegy for Barry McKinnon, “I wanted to say something,” so it just seems fairfor me to do the same for him. Sometimes one simply requires another eye.

“There’s a moral / here or there //isn’t,” he writes, as part of this sequence, “Cut,” “how a straight / edgecreates the curved // cut that will heal / in a crescent shape.” There hasalways been something quietly powerful about Weaver’s work, comparable to thework of Ottawa poet Jason Christie for their stretches of lyric concretenessacross lengthy meditative stretches, considerations of writing the complexitiesof fatherhood, the long form and their own modesty. I’ve been attempting to getthese two to interview each other for some time now, to clarify, perhaps, someof their overlap, but as of yet, I have been unsuccessful.

*

In a recent substack post, American poet Maggie Smith writes:

The writing life is one withmany paths. There’s no one way. I wish I’d thought more about this when I wasstarting out; it would have relieved a lot of pressure. And I wish I hadrealized how many writers—most of us!—have jobs outside of writing books. We’reteachers, editors, arts administrators, and technical writers. We’retherapists, receptionists, and childcare providers. We’re doctors, yogateachers, and small business owners.

When I say, “I’m a writer,” I’mtelling you about more than what I do for a living. I’m telling you who I am.

There’s a lot swirling around in those fewsentences worth commenting upon, at least from where I’m sitting: a variety ofresponses of what I might think, or have thought, or might say, or have said.Smith is entirely correct, obviously: as many ways to write as there might bepractitioners. As many grains of sand on the beach, say, or stars in theheavens. The first decade or so of my own foray into serious writing includedhaving to figure out how best to approach my own writing. It isn’t enough to learnhow to write, but learn how best I should be writing the things I should bewriting. There are no clear paths, nor across-the-board solutions. What mightwork for one might be anathema to another.

I work best through routine, and byscratching out attempts to figure out shape. My first drafts can often beleagues away from where the poem, the story, the manuscript, might finallysettle. Although, I say “settle” as though the process inevitable and smooth,of which it is neither; there are drafts upon drafts upon drafts, includingmultiple on paper and those through my own head. I used to take thirty to fiftyhandwritten drafts to make it to a single page, a single poem. Now the processis much more internalized, but my literary archive still grows in leaps andbounds, in pages scribbled upon and reworked. There is an endless array, evendown to the copy-edit. A word, moved. A word, excised. The occasional typo.

*

Someone posts a paragraph by VladimirNabokov to social media, on how he attempted to discern the difference of tastebetween a poisonous and non-poisonous butterfly. Why did he do this? And whathave we, as readers, learned through his experience?

August 10, 2025

SPEECH DRIES HERE ON THE TONGUE: Poetry on Environmental Collapse and Mental Health, eds. Hollay Ghadery, Rasiqra Revulva and Amanda Shankland

The poets inthis book explore the complex relationship between environmental collapse andmental health, inviting readers to consider the unprecedented personal impactsof the crisis. The looming thread of environmental collapse has brought with ita sense of impending annihilation and intensified a mental health crisis thatwas made crueller by a global pandemic that revealed our fragile nature. As writers,we use our words to navigate this turmoil, alleviate our own suffering, and inspireothers. Through speaking and writing, we reclaim power, not only over our ownnarratives but in how we shape our collective futures. As we continue tograpple with the overwhelming realities of ecological destruction, these poemsinvite us to listen, to feel, and to respond. In this moment of profound loss,we are reminded that the voice can be a force for change, a means of healing. Thoughthe weight of environmental collapse may sometimes silence us, we are called tospeak. Even as speech may dry on the tongue, it gives us a thirst for change. (“Editor’sPreface”)

I’mintrigued by this new collection,

SPEECH DRIES HERE ON THE TONGUE: Poetry on Environmental Collapse and Mental Health

, edited by Hollay Ghadery, Rasiqra Revulva and Amanda Shankland (Guelph ON: The Porcupine’s Quill, 2025), a poetrytitle that provides a complexity of literary response to “the relationshipbetween environmental collapse and mental health,” and the precarity throughwhich we currently live. “whereupon I join Lear and his Fool / on the blastedheath,” writes London, Ontario-based writer and speaker Jennifer Wenn, in thepoem “Fire and Flood,” “and while the erstwhile king howls / at the gale and delugeI cower, / uselessly, / looking for a sign, [.]” There are multiple piecesechoing Wenn’s particular sentiment, seeking a sign or marker of hope throughthe gloom, with other pieces that rage their appropriate rage through the storm,or even a spiraling into a dark swirl of hopelessness. As Toronto-based poet,editor and translator Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi begins the poem “Movement XVI”:“that dark resignation to loss. how long to run after joy and just / find constructioncones scattered. I take out the trash and who / knows maybe I’m resistant topesticide. some relief comes in / the form of needles. I’m defeated by numbers.It simply won’t / happen.”” Sometimes the only way to respond to a crisis is towrite through it, providing a clarity of thought and potential action, and thiscollection, put together as the result of a public call, provides an assemblageof first-person lyric narratives by some two dozen Canadian poets that shake tothe roots of mental health and climate concern, providing both observational comfortand clarity to their sharpness. The collection includes contributions byBrandon Wint, Jennifer Wenn, Conal Smiley, Concetta Principe, Dominik Parisien,Khashayar “Kess” Mohammmadi, Kathryn Mockler, Tara McGowan-Ross, D.A. Lockhart,Grace Lau, Fiona Tinwei Lam, Aaron Kreuter, gregor Y kennedy, Maryam Gowralli,Elee Kraljii Gardiner, Sydney Hegele, Karen Houle, Nina Jane Drystek, AJDolman, Conyer Clayton and Gary Barwin. There’s a precarity to these lyrics,these lines, one that writes directly into crisis,

I’mintrigued by this new collection,

SPEECH DRIES HERE ON THE TONGUE: Poetry on Environmental Collapse and Mental Health

, edited by Hollay Ghadery, Rasiqra Revulva and Amanda Shankland (Guelph ON: The Porcupine’s Quill, 2025), a poetrytitle that provides a complexity of literary response to “the relationshipbetween environmental collapse and mental health,” and the precarity throughwhich we currently live. “whereupon I join Lear and his Fool / on the blastedheath,” writes London, Ontario-based writer and speaker Jennifer Wenn, in thepoem “Fire and Flood,” “and while the erstwhile king howls / at the gale and delugeI cower, / uselessly, / looking for a sign, [.]” There are multiple piecesechoing Wenn’s particular sentiment, seeking a sign or marker of hope throughthe gloom, with other pieces that rage their appropriate rage through the storm,or even a spiraling into a dark swirl of hopelessness. As Toronto-based poet,editor and translator Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi begins the poem “Movement XVI”:“that dark resignation to loss. how long to run after joy and just / find constructioncones scattered. I take out the trash and who / knows maybe I’m resistant topesticide. some relief comes in / the form of needles. I’m defeated by numbers.It simply won’t / happen.”” Sometimes the only way to respond to a crisis is towrite through it, providing a clarity of thought and potential action, and thiscollection, put together as the result of a public call, provides an assemblageof first-person lyric narratives by some two dozen Canadian poets that shake tothe roots of mental health and climate concern, providing both observational comfortand clarity to their sharpness. The collection includes contributions byBrandon Wint, Jennifer Wenn, Conal Smiley, Concetta Principe, Dominik Parisien,Khashayar “Kess” Mohammmadi, Kathryn Mockler, Tara McGowan-Ross, D.A. Lockhart,Grace Lau, Fiona Tinwei Lam, Aaron Kreuter, gregor Y kennedy, Maryam Gowralli,Elee Kraljii Gardiner, Sydney Hegele, Karen Houle, Nina Jane Drystek, AJDolman, Conyer Clayton and Gary Barwin. There’s a precarity to these lyrics,these lines, one that writes directly into crisis,Theseare poems that want and crave hope, but can’t always get there, perpetually searchingthrough the fog for a clarity. How might we get there? “My best friend tells /me all life on earth shares a single common / ancestor, with a name.” writes urban Mi’kmaq writer and multi-disciplinary artist Tara McGowan-Ross as part of thepoem “if I had a son I would call him Ben,” “My therapist explains that / my obligationschange as something gets closer.”