Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 3

September 28, 2025

Sophia Dahlin, Glove Money

THAT’S MY WEAKNESSNOW

I’m well known throughoutthe co-ops for being a splashy dishwasher,

and I’m well known in thesuburbs for singing to the mayor’s daughter.

Wine is cheaper thanbooks unless you drink it by the bowlful.

I need books hand overhand and my hands are soulful.

Softer than a cloud in achild’s rhyme, your dainty cleaning after love.

Softer than the edges ofa fan’s blades furred with dust.

You speak intimateuniverses to your listeners, then make moue.

Surely no one since Boophas winced at fierier triumphs than Sophia.

The latest from Berkeley poet and editor Sophia Dahlinis

Glove Money

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), a follow-up to herfull-length debut,

Natch

(San Francisco CA: City Lights, 2020).“obviously I am a child of language,” she writes, to open the poem “LIFESTUFF,” “for I think I am a child of nature / raised on words I believe Iwas raised in a green pasture / having ideas about goats, ideas about sheep /yet literally never in my life having been beside a sheep of any color /temperament or texture, sure though of its woolly heft and fecal odor [.]”There is a lushness to these poems, monologues extended and compact, propelledand performative, offering gestures, agency and an urgency that feels moreforceful, even grounded, through being spoken in hushed tones. “I come sore myimmediate waters,” she writes, as part of the short poem “RIVERR PONDR LAKERSEAR,” “run drawing out these previous waters / I wish rivers of cum didn’tall connect / but glad you can’t step in it twice / the water’s always changing[.]” These poems are insistent, immediately present and confident, witty andeven dangerous, such as the poem “SHE’S GOT A HABIT,” that includes: “I’m theschmuck receiving warning, // and I’m the predatory lesbian / promising oralunderstand to / the girls at karaoke. / But I’m unbelievable, / I croon to him/ ‘You’ll be the lonely one’ and I mean // me, the dizzy cook, who bites / thetops off / carrots, swaps recipes mid- / bake, spins in the pan / to check theoil’s hot.” And I can’t imagine there are too many poems that weave togetherkaraoke, cooking, oral sex, a reference to John Lennon and a phrase by Canadianpoet Lisa Robertson (and that’s only on the first page of this particular fivepage ride). Pay attention to Sophia Dahlin: this collection really is somethingglorious to behold.

The latest from Berkeley poet and editor Sophia Dahlinis

Glove Money

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2025), a follow-up to herfull-length debut,

Natch

(San Francisco CA: City Lights, 2020).“obviously I am a child of language,” she writes, to open the poem “LIFESTUFF,” “for I think I am a child of nature / raised on words I believe Iwas raised in a green pasture / having ideas about goats, ideas about sheep /yet literally never in my life having been beside a sheep of any color /temperament or texture, sure though of its woolly heft and fecal odor [.]”There is a lushness to these poems, monologues extended and compact, propelledand performative, offering gestures, agency and an urgency that feels moreforceful, even grounded, through being spoken in hushed tones. “I come sore myimmediate waters,” she writes, as part of the short poem “RIVERR PONDR LAKERSEAR,” “run drawing out these previous waters / I wish rivers of cum didn’tall connect / but glad you can’t step in it twice / the water’s always changing[.]” These poems are insistent, immediately present and confident, witty andeven dangerous, such as the poem “SHE’S GOT A HABIT,” that includes: “I’m theschmuck receiving warning, // and I’m the predatory lesbian / promising oralunderstand to / the girls at karaoke. / But I’m unbelievable, / I croon to him/ ‘You’ll be the lonely one’ and I mean // me, the dizzy cook, who bites / thetops off / carrots, swaps recipes mid- / bake, spins in the pan / to check theoil’s hot.” And I can’t imagine there are too many poems that weave togetherkaraoke, cooking, oral sex, a reference to John Lennon and a phrase by Canadianpoet Lisa Robertson (and that’s only on the first page of this particular fivepage ride). Pay attention to Sophia Dahlin: this collection really is somethingglorious to behold.September 27, 2025

Farid Matuk, Moon Mirrored Indivisible

To stay inside the blind’sslat light, words

Would touch paper, a jar,the smell of the laid upon

By foundations, the samesteady, wide sunlight

Cut through at the bottom

By busy diesel routes andmy citizen skin

Walking around dares beheading

In a recruitmentvideo Then the outrage comes

To make a story of thetool,

When it’s just an iterationof sky

Piled with tacticalflight paths (“Perfect Day”)

Itis very good to see a new book by American poet Farid Matuk, his

Moon Mirrored Indivisible

(Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2025), althoughfrustrating to realize I’m a book behind, having missed

The Real Horse

(TucsonAZ: University of Arizona Press, 2018), but catching

This Isa Nice Neighborhood

(Letter Machine Editions, 2010) and My Daughter La Chola(Ahsahta Press, 2013). Set in four numbered sections of short, sharp lyrics,Matuk’s poems offer an exactness of first-person exposition and exploration,seeking out points along the long line of experience through the world and howit works, or doesn’t entirely work the way it should. “So, we’re at the edge / Ofthis visibility regime?” writes the six-line poem “Show Up,” “Maybe two inchesback / A little and aging // Against it we’re told to repeat / Our dissonanceand lack of closure [.]” Matuk works through his lyrics writing collision of narrationand image, offering observation and commentary, and the occasional mirror. “Iwant to talk to you about happiness to stay inside it,” opens the poem “BeforeThat,” “But boys displaced by proxy war are falling onto gravel / Outside my window,under the police helicopter’s searchlight // The gravel bites through to theknees; the searchlight is a thing / The bars on the windows are promised to //And the wisdom of the body, like articulations // Of capital through time,means some things / But not others [.]”

Itis very good to see a new book by American poet Farid Matuk, his

Moon Mirrored Indivisible

(Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2025), althoughfrustrating to realize I’m a book behind, having missed

The Real Horse

(TucsonAZ: University of Arizona Press, 2018), but catching

This Isa Nice Neighborhood

(Letter Machine Editions, 2010) and My Daughter La Chola(Ahsahta Press, 2013). Set in four numbered sections of short, sharp lyrics,Matuk’s poems offer an exactness of first-person exposition and exploration,seeking out points along the long line of experience through the world and howit works, or doesn’t entirely work the way it should. “So, we’re at the edge / Ofthis visibility regime?” writes the six-line poem “Show Up,” “Maybe two inchesback / A little and aging // Against it we’re told to repeat / Our dissonanceand lack of closure [.]” Matuk works through his lyrics writing collision of narrationand image, offering observation and commentary, and the occasional mirror. “Iwant to talk to you about happiness to stay inside it,” opens the poem “BeforeThat,” “But boys displaced by proxy war are falling onto gravel / Outside my window,under the police helicopter’s searchlight // The gravel bites through to theknees; the searchlight is a thing / The bars on the windows are promised to //And the wisdom of the body, like articulations // Of capital through time,means some things / But not others [.]” Edginghis circle of subject matter beyond the immediate domestic and fatherhood of someof that earlier work, the ripples of this current collection still hold at thatcentral core, but move further out into the world, attempting a declarative staccatoacross a firm lyric, something that has long been present within his work. “PornoClydesdale leadership pony totems,” begins the poem “Form & Freight,” “Onfire sons would be Bid us prance / Tamp this scrub grass tocome up in sparkler light, / Branchinginto three or four points at the ends, every time [.]” In clear tones, Matukarticulates his observations across an increasingly hostile culture, fromwithin an America ramped up in rhetoric, domestic terror and foreign wars, and eventhe purpose of poetry across such divides. “However mannered,” he writes, aspart of “Concentric,” “the poem dares // Write about the poem / I’m fool enoughto say it flattens [.]”

September 26, 2025

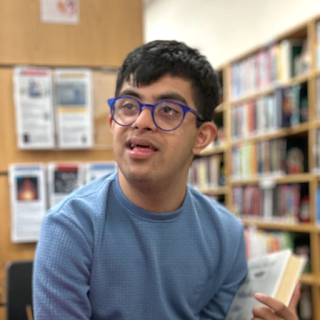

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sid Ghosh

Sid Ghosh

is a levitator of language, meandering through the rivers of Down Syndrome, gilling himself through poetry. He is the author of two chapbooks: Give a Book and

Proceedings of the Full Moon Rotary Club

. His full-length debut is

Yellow Flower Gills Me Whole

. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Sid Ghosh

is a levitator of language, meandering through the rivers of Down Syndrome, gilling himself through poetry. He is the author of two chapbooks: Give a Book and

Proceedings of the Full Moon Rotary Club

. His full-length debut is

Yellow Flower Gills Me Whole

. He lives in Portland, Oregon.2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I am a poet. So getting here is a life flow situation, I think.

3 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I mostly keep some amorous tether to the wisdom inherent in volumes of books living in me.

4 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Amorous tether lets me be quick.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

So freeing to interact with a live audience. Settles me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Why answer when you can ask!

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Really freeing the public’s mind.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Want final say. But editor is essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Foster your inner poet. Write.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Mother, asters, lakes that flow, amorous tethers, yaks, math.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Tarragon.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Still poetry, asters, lichen, lakes that flow, winds that rest.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Herman Hesse.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Love, live, laugh.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Fermenter.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Chris Martin and Mother.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

All X-Men.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Sufi poetry.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 25, 2025

Gina Myers, Works & Days

Everybody’s working for the weekend

Unless you’re working forthe Clampdown

The Jam sing, If wetell you that you got two days to live

Then don’t complain

John Maynard Keynesthought that technology

Would advance enough togive us

A 15-hour workweek

And David Graeber pointedout that it probably has

Thelatest from Philadelphia poet Gina Myers [see my review of her prior collection here] is the book-length suite,

Works& Days

(Philadelphia PA: Radiator Press, 2025), a collection that playsoff the dailyness and immediate title of

Works and Days

(New York NY:New Directions, 2016) by the late American poet Bernadette Mayer (1945-2022). Insteadof articulating the dailyness of being, Myers works through, as Marie Buckoffers in their back cover blurb, “[…] all the hours we’ve lost to working; italso registers the continuous urge to want more from life than just sustainingoneself with a paycheck.” “Once I commit to writing a long poem about work,” Myerswrites, near the end of the collection, “I decide to read a number of booksabout work / And this too becomes work, thankless and unpaid / And it begins tomake me feel worse / And I begin to dread the work of reading about work [.]”

Thelatest from Philadelphia poet Gina Myers [see my review of her prior collection here] is the book-length suite,

Works& Days

(Philadelphia PA: Radiator Press, 2025), a collection that playsoff the dailyness and immediate title of

Works and Days

(New York NY:New Directions, 2016) by the late American poet Bernadette Mayer (1945-2022). Insteadof articulating the dailyness of being, Myers works through, as Marie Buckoffers in their back cover blurb, “[…] all the hours we’ve lost to working; italso registers the continuous urge to want more from life than just sustainingoneself with a paycheck.” “Once I commit to writing a long poem about work,” Myerswrites, near the end of the collection, “I decide to read a number of booksabout work / And this too becomes work, thankless and unpaid / And it begins tomake me feel worse / And I begin to dread the work of reading about work [.]”Therehas been an interesting anti-capitalist work poetry emerging from Philadelphiafor some time, centred, as my awareness provides, around the work of Myers andRyan Eckes [see my review of his latest here], offering a kind of continuationof the 1970s “work poetry” ethos worked through by Canadian poets Tom Wayman,Kate Braid, Erín Moure and Phil Hall, and furthered by poets including the late Vancouver poet Peter Culley (1958-2015) and other elements of The KootenaySchool of Writing (Wayman being one of the founders), to more recent examples,whether Vancouver poet Michael Turner (think Company Town, for example),Chicago poet Andrew Cantrell or Vancouver poet Ivan Drury [see my review of his full-length debut here]. Whereas those early Vancouver days of “work poetry”championed the idea that labour was worth articulating as literary subjectmatter, an idea that evolved through poets such as language-specificinterrogations and pro-labour criticisms of capitalist culture—leaning into thework of poets such as Jeff Derksen, Louis Cabri, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Clint Burnham, Colin Smith, ryan fitzpatrick and others—Myers employs numerous of thosesame threads with the added flavour of general frustrations, one that I knowshe shares with numerous other writers (few who ever discuss such in theirwriting): the mere fact that requiring employment takes time away from actuallywriting.

And yet—I tell myself Iam unlearning productivity

Then I found out I haveto have surgery

And will be off work fora couple of weeks

I ask for recommendationsof movies and TV shows

To watch and make stacksof books to read

I think maybe I’llfinally work on that essay

That has been kickingaround in my head

Or write a book review ortwo

Things I enjoy doing buthave felt too depleted

By work in recent yearsto work outside of work

When it is time for me toreturn to work

I feel like a failureeven though I know it is wrong

I was not productive atall as my body healed

And I slept entire daysaway

Not everyone holds the same physical requirements, the same mental load, foremployment, which can allow for a very different level of post or pre-workenergy. We all know about Frank O’Hara working poems during his lunch break, Dr. William Carlos Williams sketching upon prescription pads, or Toronto poet bpNichol, who used to compose his thoughts directly into a tape machine, duringhis long commutes from downtown Toronto to his lay-work at Therafields.Vancouver poet George Stanley composed a long poem while commuting around on BC Transit. Minneapolis poet Mary Austin Speaker composed The Bridge(Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2016) [see my review of such here], heraccumulation of untitled, stand-alone poems as she made her daily commuteacross New York’s Manhattan Bridge. I also know of writers too exhausted toeven think about writing, once they leave the physical threshold of work.

Ina cohesive collection of accumulated, first-person lyric interrogations, Myerswrites on writing and work. She writes on writing and not writing, and offeringher best energies and time to what she cares less about than other elements ofher life, and of wanting to keep her writing life and writing time separatefrom ideas of “product,” a notion she feels enough pressure, put upon through capitalism,to resist. “It turns out when I wasn’t writing” she offers, “I still filled notebookswith words / But I didn’t think it counted / Because there wasn’t a product toshow [.]” Myers writes of fear and of silence, and of being too tired to thinkabout writing, despite such fervent wish to get to the page. She writes of herown expectations, and through capitalism and propaganda, wasted time andwork-speak, reminiscent of the corporate-speak that Canadian expat Syd Zolfexamined through their own full-length collection, Human Resources(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2007), attemptingto turn a dehumanizing language back in upon itself. Simultaneously many-layeredand straightforward, these poems are very different than how Bernadette Mayermight have approached the same subject matter. One might say the world isdifferent now, certainly, as Myers pushes her lyric far deeper into a critiqueon capitalism, and a study around how writing gets made, among and between therequirements and expectations of full-time employment.

This is the fear: that wego through our lives unable to do

The things most importantto us, everyone making demands of our time

The working conditionsays there will never be time enough

When you think you’vemade it, it’s too late

Or as the Dead Kennedys say in “At My Job”:

Thank you for yourservice and a long career

Glad you gave us yourbest years

September 24, 2025

Jane Shi, echolalia echolalia

I’m intrigued by the long sentence, sentences, that stitch together toform Vancouver poet Jane Shi’s full-length debut,

echolalia echolalia

(Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2024), a collection that follows her debut chapbook

Leaving Chang’e on Read

(Vancouver BC: Rahila’s Ghost Press, 2022). Stretchingacross the length and breadth of the one hundred and twenty compact pages ofher debut collection, hers is a remarkable extended thought across lyricmeditation and formal invention writing the body, loss, nostalgia and layers notsimply reconsidered, but recycled, repurposed. “a tide-pool winter a hiss / ofhot violets little fibres / along my bedspread brush of threaded grass / in thegrubby broken cinema of memory scrub / my back filthily in the thick sublunarylust / starts would make canyons o me the vast valleys / airless marshes wheretravellers stumbled,” she writes, to open the poem “worship the exit light,” apoem subtitled “A found poem created / from my wordpress poetryjournal / of my late teens (2008-2016) [.]”

I’m intrigued by the long sentence, sentences, that stitch together toform Vancouver poet Jane Shi’s full-length debut,

echolalia echolalia

(Kingston ON: Brick Books, 2024), a collection that follows her debut chapbook

Leaving Chang’e on Read

(Vancouver BC: Rahila’s Ghost Press, 2022). Stretchingacross the length and breadth of the one hundred and twenty compact pages ofher debut collection, hers is a remarkable extended thought across lyricmeditation and formal invention writing the body, loss, nostalgia and layers notsimply reconsidered, but recycled, repurposed. “a tide-pool winter a hiss / ofhot violets little fibres / along my bedspread brush of threaded grass / in thegrubby broken cinema of memory scrub / my back filthily in the thick sublunarylust / starts would make canyons o me the vast valleys / airless marshes wheretravellers stumbled,” she writes, to open the poem “worship the exit light,” apoem subtitled “A found poem created / from my wordpress poetryjournal / of my late teens (2008-2016) [.]”Across five sections of lyrics that offer visual and language play—“UnreliableNarReader,” “griefease,” “picture/que,” “TheOrganization” and “ECHOLALIA AS A SECOND LANGUAGE”—Shi offers poemsas declaration, observation, visual reference, restraint and expansive gesture,study notes; as points of clarity, both to the reader and herself. “You offerto run him over with your wheelchair.” begins the poem prose sequence “I’llDial Your Number,” a sequence that counts down in reverse order, starting withfive. “I come to you deceived and smelling of fish oil. You pat my back withyour hospital-gown grin. It’s so soft I cackle. I cough him out tat the rate ofdecomposing newspapers.” Her lyric is delightfully witty, even absurd, and subversive,articulating through her exploratory gestures an underlying loss that layers,ripples, the more one moves away from those points of origin. Listen, forexample, to the opening of the poem “then you put missing them in your calendar,”that begins:

after tax season you stare at the gingko leaf lines ofyour excel sheet. long bridges dull linger of lullabies. until. you pause ateach last lantern lit desk doorknob dusk grip laptop foxglove-covered drawer. openit to sort through documents you were too tired to sort through last winter. returnto each drawstring/word dock/sticky note: another year, gone. smoke insong-shadow, milk candle rehearsal. you light things up to shimmer chimney whatthey’ll say when they hear you. you light things up till your steps are in stepwith theirs through history’s afterword.

These are such lovely visual and gestural sweeps, such as the poem “Iwant to face consequences,” which begins with and leads into such an expansive swirlacross the page, one of a number of such she composes throughout: “17 / years /old, and / still throwing / tantrums, the suburban / problem so specifically /misdiagnosed / as the problem / of picky eating, on a sunday 10 / years latershe’ll check / into a resignation hostel, become / an audible ghost, beckon amake-believe / social worker to arrive at her pillowside like a tooth / fairy.”There’s a coming-of-age or coming-into-being element to these poems, but onefar more self-aware and wry, more playful, than most examples I’m aware of,providing a sense of exploration and wonder, collaging observation withcultural and pop culture references, and what one carries no matter where one lands,such as the poem “is it literature or deforestation?,” that includes:

you imagine her in the faces of others: you see themogui of race in the crowds of this too-Asian campus: so you emptied yourselfof what they saw as competition: remaining useless so you no longer neededneeding: years later he will Gwen Stefani another sidekick: she will have thesame name as you: will get another chance to pay respects: stilling a compassof coincidence: had a knife fight in the Uwajimaya parking lot: not a shell(not a shell): you belong to shoe polish: you belong to gavel polish: goodbye2014: your legs froze: your throat thawed: you ripped up their contract: refusedto take hush money: god/dess of mercy smiling through the paragraphs: ghosts: historians:hesitations: scrawled hi: hello: the caramel salt sting: sigh: wont be long now

September 23, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mia Kang

Mia Kang is the author of All Empires Must (AirliePress, 2025), which won the 2023 Airlie Prize, and the chapbooks Apparent Signs (Ghost City Press, 2024) and City Poems (ignitionpress, 2020).Her writing has appeared in Gulf Coast, Poetry Northwest, Pleiades,wildness, and elsewhere. Named the 2017 winner of Boston Review’sAnnual Poetry Contest, she has also received awards and residencies fromBrooklyn Poets, the Academy of American Poets, the Fine Arts Work Center inProvincetown, Millay Arts, and University of the Arts. Whatever prizes she haswon, she paid for three-fold in submission fees. www.miaadrikang.com

Mia Kang is the author of All Empires Must (AirliePress, 2025), which won the 2023 Airlie Prize, and the chapbooks Apparent Signs (Ghost City Press, 2024) and City Poems (ignitionpress, 2020).Her writing has appeared in Gulf Coast, Poetry Northwest, Pleiades,wildness, and elsewhere. Named the 2017 winner of Boston Review’sAnnual Poetry Contest, she has also received awards and residencies fromBrooklyn Poets, the Academy of American Poets, the Fine Arts Work Center inProvincetown, Millay Arts, and University of the Arts. Whatever prizes she haswon, she paid for three-fold in submission fees. www.miaadrikang.com1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My recent book All Empires Must is my first full-length, and I'mnot sure if its publication has changed my life. My main feelings toward itsrelease have to do with the strangeness of being nearly a decade removed fromthe process of writing it. The years I spent working on those poems (2015-2017),however, certainly changed my life. It was my first experience working on aproject at that scale, and it was also my deepest experience with writing todate, in the sense that I discovered how an immersive conceptual engagementcould process personal experience into something else. I think the book is moreserious, maybe braver, than what I've written since, but it's also less honest,or self-accountable. I guess that's the description of being young.

The best way of describing the difference between my recent work and myprevious is probably to say I have become less precious about poetry. Part ofthat is that I've become less ambitious, in the sense of some external idea of"achievement" as a writer. I want to be serious, but I do not want tobe prestigious, which I desperately did want when I was younger. That allows meto be looser, to try more varied approaches, and to let things take the timethey take.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

As a kid, I actually tried to write fiction first. But I could never geta story to go anywhere. I would get mired in description. Plot held no interestfor me. When I first started getting serious about poetry, after I moved to NYCin my late teens, I also tried to write non-fiction intermittently. I couldonly really do it in email form. There's a trove of long emails I wrote tofamily members from the years I was 17 and 18, plus a bunch I wrote to a mainlyemail-based lover the years I was 18 through 20 or so. But I've never succeededin connecting with the essay as a form for my own thinking. I have the vaguememory––possibly fabricated––of my first poems being written on scraps ofpaper. Poetry writing, in that sense, was easier to hide. Haha.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

Total variety. I tend to start from some kind of fixation. I've probablygrown more attuned over the years to what kind of fixation might be likely tohold up as the basis for writing and what might not, but I still get surprised.I think I used to be closer to writing on a day-to-day basis; I used to findthat first lines or sticking phrases would pop up and I would go from there.Since having my relationship to reading and writing completely reconfigured byvarious engagements with institutions (that's the avoidant way of sayinggraduate school), I've had to work much harder to make space for language toshow itself. I'm not very disciplined about it, frankly, and sometimes I feelbad about that.

The poems in All Empires Must often came in a single sitting, buteach poem (and the book as a whole) was at one point or another completelytaken apart, edited, and reformulated. Some of the early drafts wouldeventually kind of splice into each other and become different poems. My secondmanuscript (unpublished, titled PERISH / ABOLISH) arrived moreintact––individual poems still required refinement, but not in the same"down to the studs" kind of way. More of the thinking was doneexterior to the poetry, in the second book. Also I was really, really, reallyangry all the time. Poems would get spit out in an already hardened state.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I guess I jumped the gun and answered the first part of this above. I'malways thinking in terms of projects, whether the project is a "book"or something else. I can't stomach the notion of a poem that stands alone.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Still trying to figure this out! I do enjoy readings, kind of. I like thephysical act of reading aloud, and I'm interested in the thing that can happenwhen that happens with an audience. However, I am also someone who finds ithard to track a poem when I'm listening to it being read aloud. I greatlyprefer reading from the page. I know not everyone is like that, but it alwaysmakes me feel weird about reading publicly myself.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

Yes. What is writing? Why am I doing this? Who am I doing it for? Whatdoes writing do?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

See questions in answer above.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I can't say that I've had too much experience working with an outsideeditor on poetry. With my first chapbook, City Poems, I got some greatedits from the folks at ignitionpress. There was one long poem in particularthat they helped me refine over several versions. At the time, I hated theprocess, but it absolutely made the book better, and I think I would be muchmore appreciative of that kind of editing now. I wish I had had the chance towork with an editor on All Empires Must. It won a book contest, so itwas published basically exactly as I submitted it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

I don't know if I think it's the best piece of advice, but it's the firstthing that comes to mind: don't give up on a piece until you've gotten 100rejections. Sadly, much about publishing is a numbers game, given the totallack of infrastructure for poetry.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Alas, I have no routine. My day begins with feeding cats and makingcoffee. From there it unravels.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

To writers and books I love. I'll reread the poetry books that have beenmost important to my writing life. I'll especially turn to the work of dearfriends. But also, and maybe more importantly, I need to go outside of writing.Learning something new helps, as does engaging with the material world(cooking, gardening, cleaning). Visual and performance art have often been thethings that get what's stuck to move.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Copal.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

My study of art history has run alongside my writing since the beginning,I guess. Architecture moves me more than probably any other visual form.Watching and thinking about and sometimes making dance and performance havebeen central to my writing as well.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Wayyyyy too many to name, so I'll just say Cam Scott because everybodyknows it already.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

You're catching me in August, and I've been to a lot of baseball gamesrecently. I really, really want to be able to walk on the field at thePhillies' ballpark, with few or no other people on it. Maybe this is the memoryof the proscenium; I just feel I need to experience this.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

I'm a nonprofit administrator, occupation-wise. I'm also qualified as anart historian, though I'm not teaching much these days due to the terribleconditions of that occupation. I'm working toward sitting for a CPA license. Iwish I could be an NBA player (I have never played basketball at all). Iestimate I will attempt 5-7 more occupations before I die.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I do many things else. Mainly else. I started my life as a dancer, and Igot injured. Writing is less expensive than say, painting, which I have notalent for anyway. Language is a source of pleasure and the stupidest kind ofcage (the one you make yourself!). Everything is writing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book was Emily Skillings' second book, Tantrums in Air,which came out recently from The Song Cave. I first read it in manuscript formover a year ago, and it is beyond fantastic and everyone should read it. Ibarely watch movies. The last great film I watched was probably Scarface,because I watch it once or twice a year, and I don't think Center Stage (withwhich I maintain a similar schedule) counts as a great film.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on a booktentatively titled Rookie of the Year. The book centers around a long,overdetermined metaphor between my failed engagement and the so-called Process,the strategy by which the Philadelphia 76ers have been trying to build a teamand win a championship since 2013. I'm still early on in the project, but Ithink the book is really about the beauty of devotion and the incongruity ofthe devastation by which it is accompanied. Several basketball-related poemsfrom the project have appeared on The Rights to Ricky Sanchez podcast over thepast year or so. None of these are published in a normal way yet, but you canhear Spike Eskin read "Breach of Promise," or you can see me give a live performance on the occasion of the NBADraft Lottery. I have a lot of problems. Daryl Morey, please give me a presspass so I can write this book.

September 22, 2025

Prageeta Sharma, Onement Won

Secular Ornament

Throughout this fallenfall into a diminished winter

with its ten thousandupturned leaves,

its impervious starlightfor which I was given sight to look up, Upa,

having perceived themind,

in an imperceptible

snowed-in shadow. A demarcatedyellow.

I was giving a future tobreathe in.

I am still discussingwhat traumas won’t shake.

Could they lessen intime?

Why do you think I amwith him because he is at peace with himself

and brings his peace tome.

There is incalculablevalue in the quiet night of nonviolent affairs.

Thelatest poetry title by American poet Prageeta Sharma, her sixth, is

Onement Won

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2025), a follow-up to her devastating

GriefSequence

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2019) [see my review of such here], a collection that wrote on and reacted to the loss of her husband due tocancer. As she wrote: “These are the facts: I lost my husband, composer andartist Dale Edwin Sherrard, on January 14, 2015, after his fight withesophageal cancer. // This is the fact and narrative, my obituary of his dyingdays, his death days.” This new collection is dedicated to her mother, and toher second husband, the photographer Michael Stussy, both of whom passed in2023. As the press release for Onement One offers: “Having been twicewidowed to cancer, Sharma questions the various relationships—familial, social,romantic, religious—that have shaped her identity.” How does one continueacross such a length of grief? Or, as the poem “Metaphorically Challenged”begins: “I meant well and resisted comparisons / for a while because those whomight cajole / me into finding their inaccuracy accurate / need likenesses. I wasmeant to find myself inside a metaphor / but I wasn’t there and feltdisillusioned.”

Thelatest poetry title by American poet Prageeta Sharma, her sixth, is

Onement Won

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2025), a follow-up to her devastating

GriefSequence

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2019) [see my review of such here], a collection that wrote on and reacted to the loss of her husband due tocancer. As she wrote: “These are the facts: I lost my husband, composer andartist Dale Edwin Sherrard, on January 14, 2015, after his fight withesophageal cancer. // This is the fact and narrative, my obituary of his dyingdays, his death days.” This new collection is dedicated to her mother, and toher second husband, the photographer Michael Stussy, both of whom passed in2023. As the press release for Onement One offers: “Having been twicewidowed to cancer, Sharma questions the various relationships—familial, social,romantic, religious—that have shaped her identity.” How does one continueacross such a length of grief? Or, as the poem “Metaphorically Challenged”begins: “I meant well and resisted comparisons / for a while because those whomight cajole / me into finding their inaccuracy accurate / need likenesses. I wasmeant to find myself inside a metaphor / but I wasn’t there and feltdisillusioned.”“Thisis about coming back to oneself. // No Ram Dass. No Be Here Now. // No Om ofsitting in place.” she writes, early in Onement One. “This is about sizeand succumbing.” Across such long and languid sentences that extend the page insequence, and poems that extend across distances and into each other, Sharmawrites through and around grief, and what might follow; what might emerge from sucha heft of death and loss and ash. Sharma composes lyric meditations on griefand beyond grief, writing lost friendships and navigating such strange, foreignand familiar territories. “I want to feel more sentient,” she writes, as partof the poem “Sunday, Sunday,” “I say to the blankets and to the neurological /labor I hope to integrate. // I don’t want the ingestible lyric of my body to blindfoldme. / I do wonder what David Lynch has learned from the Upanishads.” Given theextensive lyric explorations of her stunning prior collection, as well, howdoes one follow grief with grief? Or, as the poem “Long-Term Intimacy andTerminal Illness” ends:

Your body is working so hardto endure these days

and my body feels the sadache of new melancholia

for what is coming, forwhat is being taken away by fate,

and what of our heartsthat become capacities of secular possession.

September 21, 2025

Qurat Dar, Non-Prophet

BE NOT AFRAID

Take the blessing in theemouth

& go. The scriptureon tattered wings.

Every word peeling fromthe skin.

Where is my levelled mountain,

my parted sea? I wish thelight would

moth toward me for once.

Enough of the vacant angels,

the platitudes, the declawedgods.

The trials I would endureto feel

the conviction of thetrees.

I’mimpressed by the meditative and exploratory “serious play” (what bpNichol termedit) of the full-length poetry debut by the former Mississauga Youth Poet LaureateQurat Dar, her

Non-Prophet

(Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions, 2025),winner of the inaugural Claire Harris Poetry Prize. “The sunlit dargah knows /no prayer but that of survival.” Dar writes, as part of the poem “Snail Respondsto the Ring of Crushed Eggshells / I Put Around the Lettuce,” “A porcelain cagethat / could spear you in its shattering. Ask yourself: / do the dervishes spinor spiral?” As judge Kazim Ali wrote to blurb the collection: “I loved Non-Prophetfor so many reasons: this book speaks to my own experience and history, itaddresses questions of spiritual and daily live (and for many of us, those twoare inseparable), but perhaps most importantly, these are exciting andimmediate poems that continue the great legacy of Claire Harris. As Harris didin her poems, Qurat Dar bravely confronts a cultural imperative to silence oracquiescence with refusal; more than refusal, but response.” Claire Harris (1937-2018),for those unaware, was an award-winning Canadian poet based in Calgary, born inTrinidad, and who emigrated to Canada in 1966. As her online entry at TheCanadian Encyclopedia offers: “Using such verse techniques as contrastingprose and poetry on the page, or alternating journalistic prose with the voiceof prophecy, Harris dramatizes and makes public the psychological strugglesexperienced by radicalized women who face oppression.”

I’mimpressed by the meditative and exploratory “serious play” (what bpNichol termedit) of the full-length poetry debut by the former Mississauga Youth Poet LaureateQurat Dar, her

Non-Prophet

(Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions, 2025),winner of the inaugural Claire Harris Poetry Prize. “The sunlit dargah knows /no prayer but that of survival.” Dar writes, as part of the poem “Snail Respondsto the Ring of Crushed Eggshells / I Put Around the Lettuce,” “A porcelain cagethat / could spear you in its shattering. Ask yourself: / do the dervishes spinor spiral?” As judge Kazim Ali wrote to blurb the collection: “I loved Non-Prophetfor so many reasons: this book speaks to my own experience and history, itaddresses questions of spiritual and daily live (and for many of us, those twoare inseparable), but perhaps most importantly, these are exciting andimmediate poems that continue the great legacy of Claire Harris. As Harris didin her poems, Qurat Dar bravely confronts a cultural imperative to silence oracquiescence with refusal; more than refusal, but response.” Claire Harris (1937-2018),for those unaware, was an award-winning Canadian poet based in Calgary, born inTrinidad, and who emigrated to Canada in 1966. As her online entry at TheCanadian Encyclopedia offers: “Using such verse techniques as contrastingprose and poetry on the page, or alternating journalistic prose with the voiceof prophecy, Harris dramatizes and makes public the psychological strugglesexperienced by radicalized women who face oppression.”Setin three sections of tight, first-person lyrics—“DUST,” “CLOT” and “BREATH”—thepoems of Non-Prophet write from a foundation of faith, of spirituality,one that the author/narrator works to understand on her own terms, not simplyreplicating or offering lip-service. “You were taught that to pray is to make /your mouth form sounds without meaning. / Reading suras like sheet music.Cradling / foreign words behind your teeth.” she writes, to close the poem “55:13,”“How fitting that your faith is just another language / you’re losing, or oneyou never learned to speak.” Dar works to articulate and engage on her ownterms, which feels a normal enough experience around growing up, but with theadded factors of cultural touchstones that seem to contradict how she has beenraised to think, feel and approach her own spirituality; the added culturalfactors of one spiritual context into another, the cultural collision betweenthe onslaught of western culture and anything else it deems outside. This is,as much as anything, a coming-of-age book around spiritual faith and culturalidentity, attempting to find balance amid what feels like chaos. “On a bathroomfloor somewhere in Lahore,” she writes, to open the poem “Ablution/Absolution,”“I’m trying to find the delicate balance between / trying not to soak the tileand trying to wash / out an hour’s worth of hairspray and backcomb, / to look presentablefor people that I’ve forgotten, / or who’ve forgotten me, maybe both.”

Again,that title, loaded with meaning through double entendre; reminiscent of theplay the late Judith Fitzgerald offered as an early title to a work on thesubject Joan of Arc and Gilles de Rais, “D’Arc and de Rais” (sound it out, you’llget there). The full work later appeared through Ottawa’s Oberon Press as 26Ways Out of This World (1999), a title I didn’t think nearly asinteresting. Curiously enough, Dar even offers her own Joan of Arc poem, “Joan,”that begins: “It could never have been me. A woman’s platform is always a pyre.”

ThroughDar’s Non-Prophet, she articulates her own seriousness beneath such performativegestures, and a sense of spiritual through the everyday, as Manahil Bandukwala offersas part of her own blurb for the collection: “As we hurtle towardsannihilation, Dar combines rich Islamic and Sufi mythology with deepfakes andTeams lights. The poems loop and circle through destruction and renewal, diasporaand home, worshipper and worshipped.” “I / see a thousand patient / fingerswhere others / see God.” Dar writes, as part of “Waiting for the Moon to HowlBack.” Or “The opposite of eulogy is a prophecy,” a poem (with such a strikingtitle) that reads with such being and purpose, and a repeated declaration of presencethat the narrator appears to be directing, first and foremost, to herself:

and the clouds whisperedto me that you will outlive this.

You will pull the starsfrom the sky with your teeth. Spit

them out, grinning. Your mouthbloodied brilliant. White-

hot with flame. You havetaken blows that could fell giants.

Kept a quiet survivaltucked below your tongue. You will

do this as long as youlive. But how you will live, darling!

Weaving dreams likeflowers in your hair. Laughing until

your lungs burst tofireworks. Loving and dancing as clumsily

as you do fiercely. Yes,my blood says that it is so, and a

river would sooner stopthan lie. Yes, the darkness will

recede. A wave pullingreluctantly from the shore. You will

outlive this. Yes, eventhis.

September 20, 2025

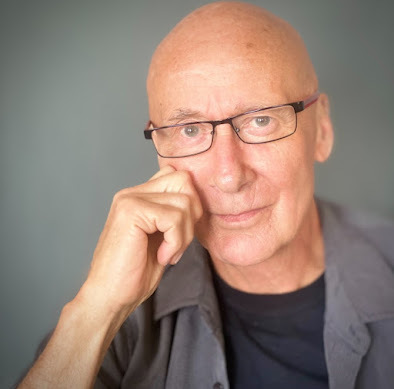

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tom Bentley-Fisher

Tom Bentley-Fisher

[photo credit:Miranda Bentley] is an award winning theatre director, teacher and publishedfiction writer and playwright. He has directed over one hundred productions,taught at numerous universities and theatre schools, and served as the artisticdirector of five professional theatres, working throughout North America andEurope.

Tom Bentley-Fisher

[photo credit:Miranda Bentley] is an award winning theatre director, teacher and publishedfiction writer and playwright. He has directed over one hundred productions,taught at numerous universities and theatre schools, and served as the artisticdirector of five professional theatres, working throughout North America andEurope.Hisfiction has beenpublished in Canadian magazines, including Grain, The Dalhousie Review, andNeWest Review. His collection of short stories, Blind Man’s Drum , was afinalist for Saskatchewan Book Awards, and his short story, "Wars and Rumoursof Wars," a finalist for the National Magazine Award for Humour. He has beenproduced by Canadian Broadcasting Company, written the foreword to sixteenpublications of new plays, and penned lyrics for plays produced in Barcelonaand Canada. His play Friends was published by Red Deer Press.

Duringhis twelve year tenureas an artistic director of Twenty-fifth Street Theatre in Saskatoon, Tom gaineda strong reputation for developing and producing original Canada plays, and wasthe founder of the Saskatoon International Fringe.

In 2008, Tom became theartistic director of Tant per Tant Theatre, developing, directing, andexchanging plays between Canada and Catalonia. His accomplishments includedirecting a critically acclaimed all-female version of The Iliad forFestival de Teatro Clásico de Mérida and a multi-lingual production of MarieClements Burning Vision for Barcelona’s International Grec Festival.

He is now the ArtisticDirector of The Yat/Bentley Centre for Performance, an international theatrecompany based out of San Francisco. He divides his time between his workoutside Canada and his home in Saskatoon.

1 - How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

My firstbook, Blind Man’s Drum, published by Thistledown Press, was a series ofShort Stories. At that time, almost twenty years ago, I used the name TomBentley. Writing initially was a way of running away from the pressures ofbeing an artistic director of a theatre. When I began to write, spurred on bythe great Canadian poet, Anne Szumigalski, I realized I could live in myaloneness. It was an interior world where I didn’t need to be an artisticleader, but was being led. I felt entirely at home.

It was thenthat I realized I could fully engage with the main thing that always fascinatedand drove me - the connection of the inner and outer life.

The Boy Who Was Saved By Jazz is my first novel - It has challenged me in new ways. I onlywrote for a few years twenty years ago and then found myself back in thetheatre. During those few years my focus was trying to discover what wasbeneath language. Strange way to get back into language but there we are.

This bookfeels different in that I am not involved with results. It feels honest andvulnerable. I am not hiding behind humour. I have been in the ‘zone’ and amwilling to expose by eccentricities.

2 - How didyou come to short stories first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I love thework of Alan Bennett. I loved how he suggested so much in the turn of a phrase.I am a bit of a sensationalist I think, and I enjoyed exposing the quick anddirty bizarre part of my mind that was challenged in short story writing.

Also - mylife’s work has been inspired by the theatre training of my mentor YatMalmgren, who is known for how he developed one of the most significantapproaches to acting. That work has guided me. It has taken me to a roadmap I’vebeen developing and now teach internationally called Character Transformation.Yat’s original title for it is ‘ThePsychology of Movement’. The premise of the work is that it takes us to theunknown in ourselves, allowing us to view the world through others’ eyes, which I believe is essential in these troubled times.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

A firstdraft is usually a quick process. I let it flow. I don’t care if it’s accurate.I try to find the essence. I feel it emotionally and write emotionally. I lovesecrets. Then comes the hard part - the rewrites. Trying to say what needs tobe said - and trying hard not to fall into the state of being clever, oranticipating what people might think.

4 - Wheredoes a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I meet thehuman being before the circumstance in prose. I ask the questions - Who areyou? Who are you trying to be? And how are you perceived? And I know that thesethree questions provide very different answers. Then comes the detective work.And them I fold in given circumstances and relationships that challenge thecharacters the most. I

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Yes, I lovereading and performing. My short stories are longing to be read out loud. Ihave been an actor - Including being part of BBC’s Radio Four Monday Nightdramas when I was an actor in England. I’m a story teller. When I ran a theatrein Canada, the administrative staff wouldn’t start work until I told them astory.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

How can getout of the pockets of ourselves?

How can wediscover the unknown in ourselves?

How can wecommunicate beneath borders and language?

How canyield down the resistances and conflicts of our time rather than taking asledgehammer?

How can wecontribute as artists and let go of the ever present ego?

How can welive within our contradictions.

Can weexperience the world upside down?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I think Imay have responded to this above, butwould add:

The currentconditions of the world demand that the role of the artist is to be the one ofthe healthiest persons in society - Emotionally psychologically, spiritually,physically. And that our greatest tool is one of empathy. As a writer I do notbelieve we should judge. We should live within the contradictions.

We canproduce a change. We must.

And always,the writer must come from love. That gives us the freedom and license toexplore hate.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

It helpsenormously. As a director of theatre I tried hard to match the playwright withthe best dramaturge for the project.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Listendeeply.

In order tosee you must be willing to be seen.

Never lookonce - Look again and again.

There areno straight lines in creativity.

Be guidedby mystery and wonder. What you don’t know is magnificent.

Live belowyour personality.

Love thechaos.

10 - Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel todirecting to playwriting)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m a cheapsensationalist. I bounce well. If you are stuck within a single medium, you canget lost in form. Different ways into the artistic questions are important. Infact, the question is often more important for the writer than the answer.

11 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

I amobsessed for several weeks. I wake up thinking - is too early to get up andstart writing? Then I leave it entirely. It is when my dreams start guiding methat I’m back. I try to write for fewhours in the morning before anything else.

12 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

I have ahard time not blaming myself for a stall. I try to allow myself to live in theinsecurity fully.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Gas fumes.My true home - Many years ago.

14 - DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

This bookcomes from the inner experience of music. Between the notes, within thetransitions of chords, there is a world that is entirely awake. It is where Ifeel comfortable. Obviously my career in the theatre has also influenced mywork. What is active? What is really going on?

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Poetry isvery important. Problem is that I’ve always felt unworthy to be a poet myself.I feel like a coward.

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want toperform my own work. I want to bring my acting, writing, directing, music, andteaching under one umbrella. I want to turn the corner and meet someone amazingwho challenges me - revolutionizes me - And takes me on an artistic voyage Inever thought possible. I want to live in my beloved Catalonia. I want todirect Medea.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Coming towriting is late for me. I do know that if I wasn’t an artist, and I’ve been employed as an artist from theage of sixteen, I’d be utterly lost. I’ve been a single parent most of my life.That has been my other joy. Maybe a teacher, although all the vocation tests Itook at school said I’d be best suited as a forest ranger. Once it came back asa light house keeper

18 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was atime when I didn’t have to take care of anybody - I could enter my ownmysteries, and that includes the pain.

19 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I re-read Crime and Punishment last week. I tend to re-read books - Dostoyevsky, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Shakespeare. I saw The Taste of Things.

20 - Whatare you currently working on?

The NakedReveal - something I’ve been carrying on my shoulders for years. I started it inNew York last summer and can’t stop. It is about the creative process, butreads in part like a novel, memoir, anda new way of looking at acting in the 21st century.

Almost aTherapist - a series I am writing with my daughter abouta therapist who needs therapy badly.

MetamorphosisBy Chaos - a series of short stories about theeccentricities of loneliness.

Almost aHamlet - a collaboration about ‘something’s rotten .…’

September 19, 2025

MA│DE, ZZOO

VENTRAL

As above, this eternitybelow the ocean waves

is a bitter and frigidblue. Heavenly heads are

full of cold light,though blood swells their hearts

with auroras pink andgold.

Peaceful poison twinklesteal along the seascape,

winking at the passingsea angels whose wing fins

flutter like twin flames,flare pinpoints of holy

fluorescence.

lucid as water, naked asan androgynous body,

their interior intimacyis brightly exposed, tweaked

into the devilish curl ofbuccal cones. Free-floating,

slow-moving alongside thedrift ice,

violence graces theangels. They crush butterflies

in the dusk of themidnight zone, gorging their young,

who will swell like a redwave until they overwhelm

the bodies that borethem.

Incase you weren’t aware, collaborative duo MA│DE, “established 2018,” as thebiography in their full-length poetry debut,

ZZOO

(Windsor ON:Palimpsest Press, 2025) reads, “is a collaborative writing entity, a unity oftwo voices fused into a single, poetic third. It is the name given to the jointauthorship of Mark Laliberte and Jade Wallace – artists whose active solopractices, while differing radically, serve to complement one another.” The publicationof ZZOO, which appears through Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther Books imprint,follows a quartet of chapbooks, the work from some of which falls into this newcollection: Test Centre (ZED Press, 2019),

A Trip to the ZZOO

(CollusionBooks, 2020), A Barely Concealed Design (Puddles of Sky Press, 2020) and

Expression Follows Grim Harmony

(JackPine Press, 2023). The poems andillustrations that make up ZZOO actively play with and between thebinary, composed as a blended work of smart and engaged language bounce andclatter and precision, resonating with sound and lyric play across thehuman-animal divide. “Questions fuzz like dust,” writes the poem “FURVERTS,” “bunniesalong the edges / of ever changing rooms. // We’re pooling our fantasies, / lowpoly sprites in a garden / of prismatic light. // When skin crawls and minds /purr, we bump against // the immovable / body // of a tree inside a forest / ofillusion.”

Incase you weren’t aware, collaborative duo MA│DE, “established 2018,” as thebiography in their full-length poetry debut,

ZZOO

(Windsor ON:Palimpsest Press, 2025) reads, “is a collaborative writing entity, a unity oftwo voices fused into a single, poetic third. It is the name given to the jointauthorship of Mark Laliberte and Jade Wallace – artists whose active solopractices, while differing radically, serve to complement one another.” The publicationof ZZOO, which appears through Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther Books imprint,follows a quartet of chapbooks, the work from some of which falls into this newcollection: Test Centre (ZED Press, 2019),

A Trip to the ZZOO

(CollusionBooks, 2020), A Barely Concealed Design (Puddles of Sky Press, 2020) and

Expression Follows Grim Harmony

(JackPine Press, 2023). The poems andillustrations that make up ZZOO actively play with and between thebinary, composed as a blended work of smart and engaged language bounce andclatter and precision, resonating with sound and lyric play across thehuman-animal divide. “Questions fuzz like dust,” writes the poem “FURVERTS,” “bunniesalong the edges / of ever changing rooms. // We’re pooling our fantasies, / lowpoly sprites in a garden / of prismatic light. // When skin crawls and minds /purr, we bump against // the immovable / body // of a tree inside a forest / ofillusion.” Thereis a bounce and clatter, but one of a density of lyric, one that works to interrogaterelations and interrelations, offering a collaborative language between andacross language, sparking a binary through a binary, and where they mightpossibly connect. The poems are layered, and sharp, writing in the midst of, oreven between, or beyond, the work of these two, such as the single sentence of thepoem “PITCHDOWN BAY,” that reads: “The small sound of a falling snowflake, /slow it down, low frequency rumble / of a whale, both melting into the ocean /in time, the water glowing as bright / as lanterns, and sailors drowning as if/ they’d seen lighthouses, more lost men / entering from the shore’s mouth,that / emptiness between the stars, pupils / compensating for this hard blanketof / deadlight night, still surrounded by / silent shorebirds, nested, watching,/ stringing the surface of the water / like quickening nix when they alight.”

ThroughZZOO, the poet/s of MA│DE write of boundaries made, met and blurred, andthe impossibilities of crossing those boundaries. As the final poem in the collection,“THE ETERNAL ZOO,” ends: “On exhibition are humanity’s / ersatz transmutations.Mammals / and mundane birds reinterpret / the phoenix, rising out of the ash /of death into which they disappeared: / Life still vivid in the distance.”