12 or 20 (second series) questions with catherine corbett bresner

catherine corbett bresner

(they/she) are the author of the chapbooks The Merriam Webster Series (2012) and

SomeBreak A / Others Say Do

(Press Brake, 2025), and the full-length poetrycollections

Can We Anything We See

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025),

the empty season

(winner, Diode Editions Book Prize, 2018), and the artist book Everyday Eros(Mount Analogue, 2017). Their poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in FENCE, VOLT,b.l.u.s.h, Denver Quarterly, Sixth Finch, Fonograf magazine and elsewhere.Currently, she are the publicist for Wave Books and co-edits Spirit Duplicator,a biannual mimeograph magazine of poetry and art, with the poet Adam Tobin.They believe in a free Palestine.

catherine corbett bresner

(they/she) are the author of the chapbooks The Merriam Webster Series (2012) and

SomeBreak A / Others Say Do

(Press Brake, 2025), and the full-length poetrycollections

Can We Anything We See

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025),

the empty season

(winner, Diode Editions Book Prize, 2018), and the artist book Everyday Eros(Mount Analogue, 2017). Their poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in FENCE, VOLT,b.l.u.s.h, Denver Quarterly, Sixth Finch, Fonograf magazine and elsewhere.Currently, she are the publicist for Wave Books and co-edits Spirit Duplicator,a biannual mimeograph magazine of poetry and art, with the poet Adam Tobin.They believe in a free Palestine. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

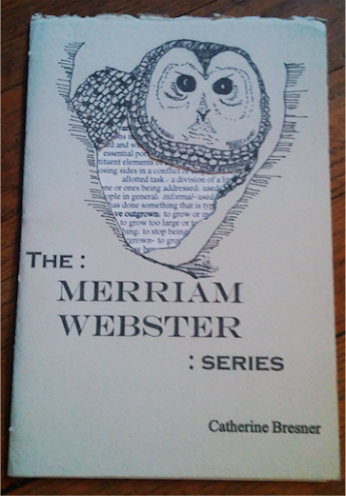

Imade my first chapbook, which was handstitched at Flying Object, an artistspace that existed in Hadley, MA from 2012-2015. I was so proud of this chap,and now I am bashful of its poems, which are pretty bad. But the design isbeautiful, I think. Here is a picture:

Atthe time of my writing the empty season, my first full-length book, my fatherwas dying quickly and prematurely, a long-term relationship ended, and I wascoming out as queer. So in a way, it feels like my life was changing in verydramatic ways and the book was a culmination of a lot of different forms whichI was playing around with at the time. Mainly, poetry comics, which I don’treally do anymore.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to,say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry when I was reallyyoung. My middle school best friend, the poet Katie Fowley, and I would go intoCambridge on a Wednesday night to hearpoetry in the basement of the Cantab Lounge in Central Square, MA. This wasduring the days when Patricia Smith was reading a lot. We were twotwelve-year-old kids and the poets there took us under their wing and treatedus like adults. It all felt very glamorous, especially for me, because I wasraised by a strict father who wouldn’t even let me watch TV during the week, andin a moment of clarity, made this one exception, so I treasured these trips.

The first poem I remember readingover and over again was Ginsburg’s “Sunflower Sutra” in HOWL, trying tomemorize it just so that I could listen to it all day in my head. Also, I havea middle school memory of a performer named Odds Bodkin who came into my schoolto perform, over the course of three days, The Odyssey in bard.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

It comes when it comes, which isalways a surprise to me. I don’t start projects as much as I get languageearworms that need to wriggle their way out or I get obsessed with asubject and then naturally I startwriting into it. A poem might start with a line, which may not even be itsfirst line. Sometimes it is not a line but just one word that needs someinvestigating. I write most days, and I am not very disciplined. Over theyears, my poetry practice has not been as much about daily writing as much as itis an act of attention in the day.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

It changes with each poem. If I ampaying attention, there is nothing ‘usual’ about the beginning of a poem atall. It is a surprise and a calling most of the time. For example, Can WeAnything We See, my most recent book, is a long poem concerned with A.I. andpersonhood. For this book, it would seem like a “project book,” and in someways, my writing constrictions made it a project. But I didn’t set out to writea book. I followed the language that became a long poem, which happens to bebook-length. It is important in my practice to make that distinction, as mypoems aren’t very good when they come from a place of knowing or planninginstead of coming from a place of curiosity. For CWAWS I started writinglanguage – about a line or two a day – in response to various randomly selectedAI photojournalism pictures that I found through keyword searches. The line wasusually written on a typewriter so that I would need to pull my attention awayfrom the screen to write. I think I might have even started our writing in pen,but then handwriting seemed too lyrical for the poem, and the language demandeda serif font. I wrote pages and pages of these lines, most of which did not endup into the slim manuscript. So by starting from a place of ekphrasis butomitting the photographs, I created a sort of reverse ekphrastic for thereader. Human beings are always doing this – filling in the gaps with our ownnarratives, and this poem lays that bare.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love giving readings, but I hate togo last and I don’t like Q&A’s. My first experiences of poetry were aloud. Sometimesreading aloud is a way I can edit my poems, and I’ve been known to edit a poemextemporaneously during a reading. Andmore than reading my own poems, I love listening to other people’s poems, whichwhy I typically request to read first, even at my own book launches. AlthoughI’ve given many readings, I always getreally nervous, and I am relieved to sit down and relax and give all of myattention to the poets around me afterwards. Also, talking is perhaps my leastfavorite form of communication, which is why I get shy at live Q&A’s. I’drather just folks come up to me after a reading and engage me in conversation.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

This is such a beautifully impossiblequestion for me to answer, as the theoretical questions I have changebook-to-book and poem-to-poem. For CWAWS, I was really curious (and yes,concerned) with the ways in which AI technologies can not only shape anindividual’s sense of personhood but also shape an individual’s sense ofcollective identity in relation to that personhood. What keywords drive dailybrowser searches? What do these searches say about our fears and obsessions?How can we believe anything we see? In what ways do we rely on photos,specifically photojournalistic ones, for evidence and why? How do captionsshape our meaning-making?

As I write this, I am rethinkingabout a lot of these questions not only because I just read today that AI’sleading developer, Nvidia, is worth 3 trillion dollars, a staggering numberthat could feed countries and end wars. Instead, the U.S. is spending billionsof dollars investing in the “Lavender,” an “A.I. targeting system used to bombGazans with little human oversight and permissive policy for casualties.” When I wrotethis poem, however, I remember that I was thinking about my own gender identitya lot in relation to AI, and in my digging around., I came across “The Gender Panopticon: AI, Gender, and Design Justice” by Sonia K. Katyal and Jessica Y.Young,” which is cited in my notes,. This article started to shape a frameworkfor my thinking around the many ways AI shapes a collective sense of personhood,for better or worse (and as the authors argue, more often the latter).

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

I think that depends on the writer,the specific culture, and the current moment. Which is to say, I don’t thinkthere is a singular answer. For me, my role is only to write.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find it to be both. I do getpleasure and a thrill sharing my work with a trusted reader/editor for thefirst time. I have an intimate list of poets who challenge and inspire me, andwhom I often share early versions of my work.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

“Don’t pay for an MFA.”—Peter Gizzigiven to me directly at my undergraduate thesis dissertation.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between textto visual work? What do you see as the appeal?

I take photographs for the samereason I write poems. I am curious about the result. And it is very easy tomove between the two mediums for me, as photography seems very externallyfocused, and poetry seems grounded in interiority. I like to think of each act asa kind of breath, poetry an inhale and photography an exhale, and I breathethroughout the day.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep,or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I am not a disciplined writer, but Ido write daily. I keep a notebook with me everywhere I go. A typical day for mebegins with making my daughter her lunch while slugging coffee. I am alwayswriting in my head until it is on the page.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turnor return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I would say that I am lucky in that Idon’t really get stalled, not in the ‘writer’s block’ sense. But the truth is Ido get stalled… by my chronic clinical depression. I have a history of outpatientand inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals, and I have also struggledthroughout the years with alcoholism and self-harm. As I get older, I try toshare about this as candidly as possible when appropriate, as my experience isvery common within writer communities, but often not discussed. So where do Ireturn for inspiration? In a way, I could say medication and therapy, as thesethings restore inspiration to me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

mothballs and pipe tobacco

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Yes, all of the above and more.

15 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

The writers who were specifically onmy mind and on my nightside table in the creating of Can We Anything We Seewere Renee Gladman’s Plans for Sentences, Rosmarie Waldrop’s Lawn of theExcluded Middle, Radi Os by Ronald Johnson.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

Make pottery. Learn to crotchet. SpeakSpanish fluently. Start a children’s book imprint. Write a review for the film HOMEstarring Isabelle Huppert and directed by Ursula Meier.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I don’t think it is an either/orsituation, but I do have dreams of becoming a beekeeper someday.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

20 - What are you currently working on?

I just started finishing a long lyric poem called SomeSay Break / Others Say Do which I started in October 2024. The firstthirty-five pages were published in a chap from Press Brake.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;