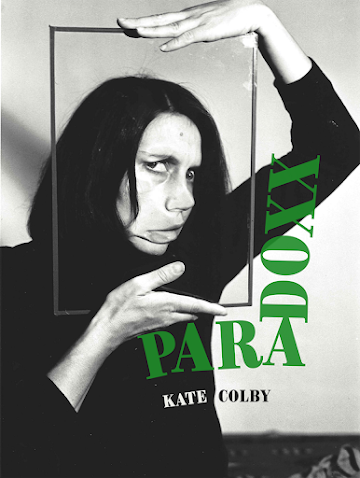

Kate Colby, PARADOXX

To lie by omission is toleave out the truth. To tell truth by omission is to leave out the lies, butthe lie of my continuity constitutes my continuity, without which there’snothing to tell. And if truth by omission is also to leave out misapprehensions,then I am not equal to the work.

Iam absolutely struck by the thoughtful and interconnected ongoingness ofProvidence, Rhode Island writer Kate Colby’s

PARADOXX

(Essay Press,2025) [a book I took with me to read in Ireland, as you well know], afirst-person non-fiction portioned across a wide stretch of exploratory,present prose. Each of her sections begins with a moment, thought or quote thatexpands exponentially out, as she reacts and explores, furthering to see howfar it might go. “Neither my experiences nor my memories are exceptional,” sheoffers, as part of the fifteenth section of her opening monologue, “HOW ITENDS,” “but the relationship between them interests me now that I have childrenmaking memories of their own. I do my best to ensure that they will havepositive memories of their childhoods, but the question of which will provemost important to them preoccupies me. When they are away from me at school andother activities, they are making memories we’ll never share, which makes mefeel that my kids are being ripped from me slowly like the wrong way to takeoff a Band-Aid.” Colby writes through the coordinates and considerations ofwomen writers, artists and thinkers, swirling around her own writing andthinking through her own parenting, and her own writing, and of those distancesthat might seem impossible but also seem impossibly interconnected.

Iam absolutely struck by the thoughtful and interconnected ongoingness ofProvidence, Rhode Island writer Kate Colby’s

PARADOXX

(Essay Press,2025) [a book I took with me to read in Ireland, as you well know], afirst-person non-fiction portioned across a wide stretch of exploratory,present prose. Each of her sections begins with a moment, thought or quote thatexpands exponentially out, as she reacts and explores, furthering to see howfar it might go. “Neither my experiences nor my memories are exceptional,” sheoffers, as part of the fifteenth section of her opening monologue, “HOW ITENDS,” “but the relationship between them interests me now that I have childrenmaking memories of their own. I do my best to ensure that they will havepositive memories of their childhoods, but the question of which will provemost important to them preoccupies me. When they are away from me at school andother activities, they are making memories we’ll never share, which makes mefeel that my kids are being ripped from me slowly like the wrong way to takeoff a Band-Aid.” Colby writes through the coordinates and considerations ofwomen writers, artists and thinkers, swirling around her own writing andthinking through her own parenting, and her own writing, and of those distancesthat might seem impossible but also seem impossibly interconnected.The poet Muriel Rukeyserfamously wrote, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?/ The world would split open.” Did she mean every little truth or oneoverarching one? Would all of the former add up to the latter? Either way,Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journal feels like what spills from thegash, evincing exhaustion and interruption—a mishmash of memories, sex,scatology, and mundane notes-to-self punctuated by shouty all-cappedimperatives from the inside of her forehead. But unconventional as it is, ClairvoyantJournal is thoroughly of its moment—the real-time transcription of the mindwas a project common to many of Weiner’s peers, including Bernadette Mayer andLyn Hejinian. Where is the line between her diagnosed schizophrenia and aliterary movement?

Throughone hundred numbered sections, Colby writes her thinking and experience throughand across an array of forebears, including Gerard Manley Hopkins, C.D. Wright,Kurt Vonnegut, Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost and Lyn Hejinian.One hundred sections, across one hundred days, reminiscent of the one hundreddays I composed my own one hundred pages across the onset of the Covid-era. Sheoffers the footnote: “One hundred days ago (on paper) I was spontaneouslyinduced to begin this writing by Jean Rhys’s unfinished autobiography. I’vesince spent years replacing nearly every word and sentence, letting the wholething gather and shed like a thousand skins of its snake. I wish my life in theworld was the same—that I could freeze it and work with what’s already heretill I knew it was fruitless and/or finished.” Her exploratory, accumulative self-containedsections almost give the sense of writing from the foundation of Hejinian’sclassic My Life (1980), utilizing biographical moments as the buildingblocks of structure, but through a more exploratory prose style, as abook-length essay, attempting to navigate, as she suggests on one point, herlife on paper. Referencing Hejinian’s Writing Is an Aid to Memory (TheFigures, 1978), she writes of memory and how it impacts being: “Writing Isan Aid to Memory is an experiment in omissionless self-depiction, where thesum of a life is an endless journey toward a shifting image of what it alreadyis. Great, but I’d rather see my memory in a display case. (It would have toinclude the display case.)” She writes of collectivity and individuality; shewrites of establishment and anti-establishment, negative capability and globalculture, folk songs and the Spice Girls. “Reflecting and reacting to the narrativeconventions of social media,” she writes, “the current literary approach toreality is self-reportage that represents representation within the exigenciesof late capitalism. I want to take a hard look at my role, but can I see itfrom inside the eddy?” She writes of forebears, as this moment near the endoffers: “I have a lot of obvious predecessors—Stein, Rhys, Wright, Hejinian. I don’tbegrudge their sexiness. I do resent my first wives, though, and all of themare men.” Her writing, her thinking, is remarkable, and this is a book worthsitting within for as long as possible. Or, as she writes near the end:

Mallarmé said, “Everythingin the world exists in order to end up as a book.” What baloney, but I’ll ownit. I process the world by considering how I’d render it on paper, and then myconclusions are the product of having been written. At times I hide from newsmedia, but am still beset by ambient information—birds and weather and aglimpse of a headline about a journalist’s beheading.

There should be a wordfor a word that should be its own opposite. Why does “behead” not mean to gaina head, in the manner of “bejewel,” “betroth” and “befriend”>

There’s a certain episodeI can’t write about because I would lie.

Willie wants to know whyall my writing rhymes.