Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 76

October 1, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Myronn Hardy

Myronn Hardy is the author of several books ofpoems.

Aurora Americana

isforthcoming, October 2023 (Princeton University Press). His poems have appeared in The New YorkTimes Magazine, Ploughshares, POETRY, The Georgia Review,The Baffler, and elsewhere. His books have garnered the PEN/OaklandJosephine Award among others. He is anassistant professor of English at Bates College.

Myronn Hardy is the author of several books ofpoems.

Aurora Americana

isforthcoming, October 2023 (Princeton University Press). His poems have appeared in The New YorkTimes Magazine, Ploughshares, POETRY, The Georgia Review,The Baffler, and elsewhere. His books have garnered the PEN/OaklandJosephine Award among others. He is anassistant professor of English at Bates College.1 - How did your first book change your life? The first book truly gave me confidence. It confirmed that it was possible to do thisthing I thought impossible which was to write and publish a book of poems. How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? Aurora Americana and my previous book, RadioactiveStarlings, are both thinking through the notion of place. They are doing this in different ways but thenotion of place is the link by which they connect. How does it feel different? AuroraAmericana is a dawn book. Most of the poems take place during or closeto dawn. I’ve never centered time inthis way.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction? I think I initially found the shapes of poemscurious. When I started learning more aboutwhat they do, how concentrated language can create feeling, make music, I knew Iwanted to attempt to make poems.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? I’ve written poems that have taken years, a couple took a decadeto write. I need time to figure out whatpoems need and how I can give them what they need. Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Slow. Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes? Rarely do poems resemble first drafts. Attempting to make and know a poem take a lotof time. I spend a long-time compilingimages, lines, phrases, sentences. Iwrite several versions before the version is set. Often, during a reading, I’ll even change aword or phrase.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning? I write poem afterpoem. I never know if single poems will compileinto a book. After several years, I’ll lookback to see what I’ve been writing, of what I’ve been fixated. Sometimes that looking back tells me that abook might be emerging.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? I likedoing public readings because they allow me to see and hear reactions to thework. As someone who attends poetry readings, I know that hearing poems read bythe poet reinform one’s experience and knowledge of the work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What doyou even think the current questions are? I’m very interested in howwe connect and disconnect. How do we live,thrive despite everything? How does placeinform? How do we sustain our humanity?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe? The roleof the writer is to see what they see and write what they write. To always go there and get to the truthdespite the pull to be untrue.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)? My experiencewith editors has been good. A goodeditor asks questions as opposed to saying, “This is wrong. Do it this way.” And this, for me, has always been helpful.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)? Be free. Your work, your writing (your poetry) is perhaps the only place whereyou can be free and dangerous. You arein control of that danger.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? I write every day. I wake up very early, before sunrise. I like to have that new day’s sunlight fallover the page as I write. I usually writefor four hours in the morning. I end themorning writing session with a run. Idedicate the evenings to revision.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration? When the writing isstalled, I read; sometimes I’ll listening to music, I’ll force myself to getlost within it.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home? Pine.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art? The natural world is my most profoundinfluence. It’s an inexhaustible resource.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work? Fernando Pessoa. Bob Kaufman. Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Lucille Clifton. Mahmoud Darwish. Elizabeth Bishop.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? I would like to visit Oman.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer? If I hadn’t become a writer, I think I wouldhave liked to have become either an architect or astronomer.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? Writing is a necessity forme. It selected me. And I said, yes. And despite that selection,I didn’t believe it was possible. Buthere I am and here it is. And I’mgrateful.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film? Book: MPH and OtherPoems by Ed Roberson; Film: Death for Sale

19 - What are you currently working on? I’m writing poem afterpoem. And I have novel manuscript. We’ll see what happens.

September 30, 2023

Ongoing notes: TIFA’s Small Press Market (part two: Lannii Layke + Janette Platana,

the moment Ken Norris met ryan fitzpatrick

the moment Ken Norris met ryan fitzpatrick

[see part one of my notes here] Here’s another accounting of some of the titles I pickedup at the most recent fair in Toronto!

Toronto ON: I’m fascinated by the debut chapbook by Toronto-based poet Lannii Layke, their Os (knife|fork|book, 2022), a gracefully-sleekcollection of exploratory poems. There is an intriguing narrative layering toLayke’s lines, offering line upon line upon fragment, a hush, and a halt. Theirauthor biography at the end of the collection offers a couple of intriguingdetails: “They attend to crafting memory and fine jewellery. In French, osis bone.” The poems here are crafted but not precious: precise, and deftin their resolve, offering eight first-person poems that seek, seek out. “wehave those secrets that stick us,” the poem “Sister” offers, “like our /talk and hate and / waxing piss onto our man [.]” There issuch graceful, absolute beauty in Layke’s searchings, one that sparkles not justthrough discovery, but revealing and remarking upon what was already known.

Plum

My frequency

factors in the cloning of plums

The rib of plum

in the posture of plumline a smaller Sweat

is that same salt collecting so

Toronto ON: There’s a wonderful sense of play and language acrossthe nine poems of Peterborough writer Janette Platana’s chapbook NewFairious (Anstruther Press, 2023), each offering short narratives, akin tocharacter studies, to a list of alternate fairies, from “The Shame Fairy” and “TheLiterary Fairy” to “The Fairies Feify & Deify” and “The Truth Fairy.” “Theyare not twins, these two,” the poem “The Fairies Reify & Deify” begins, “butreciprocating parasites who // rfuse to play host. / Yet each outstrips theother // in unxious luxury.” There’s a delight of sound and meaning through herword choises throughout these poems, offering an unexpected richness line by lineby narrative line, all of which rolls along into a sequence of impossibility. HowPlatana is a writer I hadn’t heard of previously, although her author biographyoffers that her short story collection, A Token of My Affliction (TorontoON: Tightrope Books, 2014), “was a Finalist for the Ontario Trillium BookAward.” Oh, how I wish to see more poems by Janette Platana.

The Shame Fairy

Her dust encauls you innausea.

Until the ignosecond ofHer enclaspment

you did not even know

She was a thing. Now, youare filled

with Her shitty gift.Now, you bob

inside Her gassy bubble

like you are the grinningbonhomme

in one of those oversizedinflatable snow globes

in the parking lot of thebiggest big box store

when your anchor cablehas sprung

and you bounce betweenparked cars,

legless, footless, aswell as entrapped,

head blog

indignant andindistinguishable

from bottom blog.

It would be funny if it weren’tforever.

September 29, 2023

David Martin, Kink Bands

TURNER VALLEY OIL FIELD

They trotted out hisanticline,

capstone crust punctuated

by a wedge-thrust to thetown’s

makeover bonanza, where

seismic pricks could plot

secured flab, and flatterhim

under talk-show sunlight.

Yet look at the aftershot:

Devonian shell-sweat is

girdled by a deer-headbuckle,

his footwall has leadfoot

an a King Cab, and during

apotheosis to carboncloud

his Nudie suit willblacken

at dusk, sloughingsequins

over our sweet, crudesleep.

Followinghis book length debut,

Tar Swan

(Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2018), comesCalgary poet David Martin’s second collection,

Kink Bands

(NeWest Press,2023), a collection slyly and semi-deceptively titled for a geological term. Asthe back cover offers, Kink Bands is composed via “lyrically experimentalpoems expanding and retracting,” in a collection that “finds sonic andconceptual energy from the perspective of deep time and the geological forcesthat have shaped and continue to shape the Earth.” The notion of “deep time” isone that contemporary poets seem to only occasionally wrestle with (not nearlyenough, one might think), focusing instead on more immediate moments and concerns,but for the length and breadth of what might be seen as Don McKay’s secondlyric act (with Long Sault more of an opening salvo than an extendedact), following a career of multiple poetry titles focusing on birds andbirding into multiple book-length lyric meditations on geological andecological time (the 2021 title Lurch might be McKay emerging out theother end of this into a larger, blended consideration, but that’s aconversation for another time). For Martin, the notion of the “kink band”examines both a layering and an extended thread, approaching his blending ofgeological research and the narrative lyric akin to extended study.

Followinghis book length debut,

Tar Swan

(Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2018), comesCalgary poet David Martin’s second collection,

Kink Bands

(NeWest Press,2023), a collection slyly and semi-deceptively titled for a geological term. Asthe back cover offers, Kink Bands is composed via “lyrically experimentalpoems expanding and retracting,” in a collection that “finds sonic andconceptual energy from the perspective of deep time and the geological forcesthat have shaped and continue to shape the Earth.” The notion of “deep time” isone that contemporary poets seem to only occasionally wrestle with (not nearlyenough, one might think), focusing instead on more immediate moments and concerns,but for the length and breadth of what might be seen as Don McKay’s secondlyric act (with Long Sault more of an opening salvo than an extendedact), following a career of multiple poetry titles focusing on birds andbirding into multiple book-length lyric meditations on geological andecological time (the 2021 title Lurch might be McKay emerging out theother end of this into a larger, blended consideration, but that’s aconversation for another time). For Martin, the notion of the “kink band”examines both a layering and an extended thread, approaching his blending ofgeological research and the narrative lyric akin to extended study.Martin’spoems are hewn, carved and crafted, comparable to if one could simultaneously carveand reconceptualize stone. Simply to read the notes set at the end of thecollection makes for interesting reading, seeing how he approaches thecomposition of poems and the application of ongoing study. Martin moves from bedrockto striation, legends of the creation and use of stone tools to the myth ofPhiloctetes, and even to Martin’s own adaptation of Earle Birney’s infamous poem “David,” from David and other Poems (Ryerson Press, 1942), a poemhe translates “into the restricted language of Basic English. the poem mimicsthe crystalline structure of foliated metaporic rocks that have been subjectedto extreme pressure and heat at tectonic zones of subduction.” There issomething so deeply fascinating about a particular interest or researchbecoming ingrained to the point that the poems that emerge feel entirelynatural. “I watch my daughter clap two mitts / of snow,” he writes, to open thepoem “SINTER,” “amalgamating hand-bergs. // A jillion columns, taunts, andspoked / dentrites have their civil distance // fractured.” There’s a playacross Martin’s sharp language, and one might even compare Martin’s lyric useof scientific research and landscape to such as Lorine Niedecker’s “Lake Superior,”or Monty Reid’s The Alternate Guide (Red Deer College Press, 1985). Hisnote on the poem “Stone Tape Theory,” for example, referencing the infamousFrank Slide of 1903, the subject of numerous poems over the years (includingone of my own, around the time of the event’s centennial), read: “One explanationfor the magnitude of displaced debris that occurred during the rockslide at TurtleMountain in 1903 (next to the town of Frank, Alberta) is a phenomenon known as acousticfluidization. To my knowledge, the Stone Tape Theory has yet to be substantiated.”As the first of the four stanzas of the poem reads:

Turtle Mountain belting atonic

from its spooned-outlungs

as Livingstone scutessurf

on tranced cushions ofsound:

charming friction’s coefficient

to embrace a dazeddisinhibition.

September 28, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Hannah Kezema

Hannah Kezema

is an artist whoworks across mediums. She is the author of the debut collection, This Conversation is Being Recorded (Game Over Books, 2023), and the chapbook,

three

(Tea and Tattered Pages, 2017),and her work appears in Black Sun Lit,Grimoire, New Life Quarterly, FullStop, Spiral Orb, and otherplaces. She was the 2018 Arteles Resident of the Enter Text program, and she iscurrently the co-editor of Moving Parts Press’s broadside series of Latinx andChicanx poetry, in collaboration with Felicia Rice and Angel Dominguez. Shelives in the Santa Cruz mountains by the sea, among the redwoods andwildflowers.

Hannah Kezema

is an artist whoworks across mediums. She is the author of the debut collection, This Conversation is Being Recorded (Game Over Books, 2023), and the chapbook,

three

(Tea and Tattered Pages, 2017),and her work appears in Black Sun Lit,Grimoire, New Life Quarterly, FullStop, Spiral Orb, and otherplaces. She was the 2018 Arteles Resident of the Enter Text program, and she iscurrently the co-editor of Moving Parts Press’s broadside series of Latinx andChicanx poetry, in collaboration with Felicia Rice and Angel Dominguez. Shelives in the Santa Cruz mountains by the sea, among the redwoods andwildflowers.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? Howdoes your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

My chapbook, three, came out in 2017 through a nowdefunct press, Tea and Tattered Pages, and I remember feeling like I’d beenvalidated as a writer. I was still sort of fresh out of grad school, and beingsolicited (after many, many rejections) and then published felt like I’d beengiven the “okay” to keep going. It’s a strange and dark little book centeredaround the number 3 – triangles, mirrors, mythology, pyramids, threesomes, andan unreliable first-, second-, and third-person narration. Very experimentaland what I would call within the Naropa [University] aesthetic. I rememberbeing really surprised that there were no edits from the publisher, aside froma few things I tweaked here and there, since I tend to over-edit. Looking back,I definitely would’ve asked more questions about the process and book roll-out,but I hadn’t even so much as signed a contract, and that book struggled to getout in the world for a variety of reasons.

My debut full-length, This Conversation Is Being Recorded,which came out with Game Over Books in late March, was a completely differentexperience, both in terms of the publishing process and subject matter. I’veworked in the insurance fraud industry for the past 7 years now in a few roles,but primarily, as a field investigator and editor, and I began writing poemsabout the cases I was working on about one year in. Over time, the poems beganaccumulating, and Game Over Books was actually the reason the book becamehybrid. I’d always been interested in incorporating visual aspects into mywork, and ironically, This Conversation Is Being Recorded was my firstwork that was just straight up poetry. Honestly, after creating hybrid workwithout any traction for years, I was a little discouraged, and I was trying todo something more “straightforward.” But I was so thankful to have a publisherthat understood my praxis as an artist and encouraged me to go all out. To pickup the paintbrush. Get my hands in the dirt.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I kind of came to poetry last! I studied literature in myundergrad while at the New School, and when I got to Naropa for my MFA, I wasvery much interested in writing prose but also expanding my notion of whatprose could be. I hadn’t read any contemporary poetry whatsoever and feltcompletely out of the loop compared to my peers. I hadn’t even heard of smallpress publishing, and outside of doing theatre for years, I’d never read mywork in front of anyone. Those two years were vigorous for me because I hadalways felt safer in the sentence than the line. Then, of course, I fell inlove with the freedom of the line.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

It depends on how we quantify a “start,” but I’d say that themoment I have an idea for something, even if it isn’t totally cohesive, Iusually make a note in my notebook or phone. Something non-committal because Idon’t want to scare the idea away! Then I’ll usually wait and see if the ideasticks. Sometimes, lines will come to me first, without the full shape of theidea, but more often than not, I’ll get the impulse to make something specificand it’s a matter of figuring out from there whether it’s fruitful orworthwhile. I think about things very categorically. When the idea becomes aThing, then the real work happens, and I am (to my own detriment) quite aperfectionist in that regard. I want my first draft to be as close to polishedas possible, and as an editor, I can’t turn that part of my brain off. Ioverthink and I edit and edit and edit, which is likely why each project takesme years to complete.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ve always considered myself a very projects-orientedperson, maybe to a fault. I have a very hard time writing a piece “justbecause,” or without thinking about it within a larger context. Of course,every now and then, I’m inspired to write a poem with no strings attached. I’mtrying to be better about this because I think being so book-forward canactually stifle the process. Who’s to say a single poem can’t hold the samegravity as a book of poems? This is something I’ve been thinking about lately.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have a kind of love-hate relationship with readings. Forstarters, they make me very anxious, despite my performance background. There’ssomething specifically stressful about reading words you’ve written in front ofa crowd – it’s more vulnerable for me than singing. But I will say that thedread only lies in the build-up of the event because once I’m reading, I’m inthe zone. And I feel the post-reading high afterwards. While it’s stillchallenging all these years later, I think it’s important to take your work offthe page and let it test the waters. What comes up – and how others respond -might surprise you and possibly change the trajectory of the work. I do believea sort of synergy can happen between the reader and the audience when bringingthe written word into a physical space.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

I’m not sure that my body of work has a unifying theme by anymeans, but I think of each work in terms of various stages of my life. All mywork is hybrid, which is a common thread, but where my earlier works were moreconceptual and form driven, This Conversation Is Being Recorded and thework leading up to it became more about my own life, my job, the seeking oftruth, and exploring issues like labor and gender under capital. Of course, Ican’t help but weave in the visual aspects, too. Perhaps I’m not as interestedin answering the questions as I am in letting the questions linger in mywork.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

This is a tough question, as I feel I’m still figuring thisout for myself. Many people will say that in these times, the role of theartist at large is to be an activist for change. I don’t disagree with this butalso feel the pressure of it and find myself just as interested with theinternal kind of revolution that a reader can experience. If a text can changethe way you think or feel, then I think it’s fulfilled its “purpose.” Alleffective change must begin with the individual. I also can’t deny that therole of the writer historically has been the outrider of society, and yet, theyare also the visionaries who archive histories, and their legacies live onbeyond them. The writer is the dreamer, the documentarian, the hermit, theShaman. Ultimately, I think writers and artists shouldn’t be afraid to createfor themselves – the act of creating a work of art is just as, if not morevital, than its reception. When we become too concerned with the latter, westray further from poetry and closer to careerism. There’s a lot of nepotism inthe poetry “community,” but I don’t believe in the commodification of poetry. Ibelieve that defeats poetry’s very essence.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Both! Especially as I’ve had many people tell me I’m a brutaleditor myself. But it’s always valuable to get an outside perspective on yourwork. Sometimes we just need another pair of eyes.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

I can’t remember who said this, or if it was a conglomerationof things other people have said, but more or less: “Give yourself permissionto write.” And probably cliché at this point, but Ginsberg’s “first thoughtbest thought.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t typically do both simultaneously, as I believedifferent mediums require different minds. But they can support one another inthat way – it can be incredibly beneficial to turn to painting when I’m hittinga wall with the writing. That being said, I do find the visual work is fasterfor me, or at least I spend less time doing it. For instance, with ThisConversation Is Being Recorded, most of the paintings were created in thefinal months of my working on the manuscript, whereas the text itself took meabout six years. For this book, I needed to get all the writing out first, sortof like laying down the foundation. I needed more time to consider how thevisuals would be executed, with plenty of trial and error along the way.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

What’s cool about this is you asked me a similar question in 2019, and when I first answered, Ihad recently completed my first residency at Arteles in Haukijärvi, Finland,during which time, I’d finally developed (if only for about a month) aconsistent writing routine. Outside of that and my MFA program, I really haven’thad one. I used to shame myself about it, but I’ve learned that I’m not thekind of writer who can force it. I’m not of the school of thought that doingsome writing is better than no writing at all. I’m just not interested inwriting for writing’s sake, but I know this works for a lot of other folks. Ialso hate sitting down at the computer. Unconventional aspects of my “writingroutine” are spending time outside, touching water, having meaningfulexperiences with people I love, sitting still with hard feelings, spending timewith art that moves me, and traveling. I let myself get inspired, and it keepsthe writing exciting (and not burdensome) for me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Usually, I read the work of others before me or turn to otherforms of art altogether, so as not to be too influenced. I’m also a firmbeliever in a good walk or moving the body in general to getunstuck.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Pine-Sol, newspaper, and fireplace smells. Fresh mint leavesalways make me think of my grandmother and her famous iced tea. Cinnamon andclove remind me of my mother.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Being in nature is vital – among the flowers, trees, animals,fungi, and bodies of water. I also usually listen to music that resonates withthe mood of what I’m writing. It’s surprising what can come up if you even justput on a song that makes you emotional. It can make the writing even morecathartic or therapeutic. I also love zoning out to images as a break fromlanguage, which can be so unruly. Letting my mind rest and my eyes scan thecolors, shapes, and textures of something allows me to slow down. Gardening andcreating floral arrangements with flowers from my garden and other things I’veforaged has also been really meditative but creative at the same time.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many, but I’ll try to be brief: Molly Brodak, Diane Seuss,June Jordan, Maggie Nelson, Clarice Lispector, Truman Capote, Lisa Robertson,CAConrad, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, etc. etc.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Take a real vacation in adulthood.

17 – If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

I always saw myself studying law or forensics if I decided togive up on my creative pursuits. I’ve also felt like I could’ve been a lawyer(or even judge) in a former life. I’m fascinated by detectives but could neverbe a cop. For some time, my dream job was to be a handwriting analyst, which Iguess isn’t too far off from writing.

18 – What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing has always come naturally for me, even if I resistedit at first. I was a voracious reader as a child and wrote these dark littleghost stories. But what I really dreamt of then was becoming an actress andsinger – I always wanted to perform. I did theater all throughout high school,studied it during my first year of college, and I was living in New York,hustling but not getting call-backs and questioning whether my heart was reallyin it. I ultimately decided it wasn’t working and took a semester off to travelto California and then transfer to another school to study literature beforelater going on to study writing and poetics in grad school. It worked outpretty seamlessly, in the end, but I still sometimes miss being on stage. Maybemy next phase will be playwriting, who knows?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

La Movida by Tatiana Luboviski-Acosta and Asteroid City by WesAnderson.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Self-care and gardening, for the most part. I’ll be teachingan online workshop focused on This Conversation Is Being Recorded onOctober 24th and hope to have some morereadings later in the year. I may have also started writing another book, butonly time will tell…

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 27, 2023

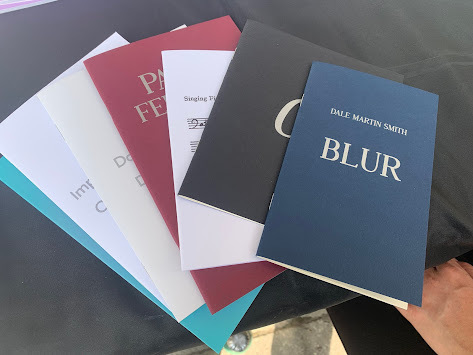

Ongoing notes: TIFA’s Small Press Market (part one: Dale Martin Smith + Chris Johnson,

[see my four posts from the debut fair back in 2019 here andhere and here and here] What a delightful fair this was! I was unable tomake last year’s event due to my host falling sick with covid last minute, butmanaged to drive down for the sake of this small curated small press fair at Toronto’s Harbourfront, as hosted by Kate Siklosi/Gap Riot Press. Here are acouple of the items I collected as part of this year’s event:

Toronto ON: Some of the most intriguing small publishingwork right now is being produced by Kirby’s Knife|Fork|Book; I’ve really beenadmiring the way that Kirby manages to find remarkable work by an array ofwriters that might not have been able to find homes for their work, at least easily.One of the titles I picked up at the fair was by Dale Martin Smith [see myreview of his 2021 Talonbook title, Flying Red Horse, here], thechapbook

Blur

(2022). Dedicated to his partner, the poet Hoa Nguyen, thepoems in Blur are an assemblage of short lyrics composed with such alight and even delicate touch. “What you know of me / is duration,” he writes,to open “Circles,” “movement / along the path between / our home and theneighbors’.” Smith’s work has long held an element of the personal in his work,but there is an intimacy here that focuses very deeply on the small that is stunningly,staggeringly moving and beautiful. Here is Dale Martin Smith composing poemswith the density and brevity of poets such as Mark Truscott or Cameron Anstee,but set with the entirety of his whole heart.

Toronto ON: Some of the most intriguing small publishingwork right now is being produced by Kirby’s Knife|Fork|Book; I’ve really beenadmiring the way that Kirby manages to find remarkable work by an array ofwriters that might not have been able to find homes for their work, at least easily.One of the titles I picked up at the fair was by Dale Martin Smith [see myreview of his 2021 Talonbook title, Flying Red Horse, here], thechapbook

Blur

(2022). Dedicated to his partner, the poet Hoa Nguyen, thepoems in Blur are an assemblage of short lyrics composed with such alight and even delicate touch. “What you know of me / is duration,” he writes,to open “Circles,” “movement / along the path between / our home and theneighbors’.” Smith’s work has long held an element of the personal in his work,but there is an intimacy here that focuses very deeply on the small that is stunningly,staggeringly moving and beautiful. Here is Dale Martin Smith composing poemswith the density and brevity of poets such as Mark Truscott or Cameron Anstee,but set with the entirety of his whole heart.Mundane

You step out of the house

with trash and rain

comes down cold,intimately

known across the time youimagine

is your life.

Jim Johnstone, Anstruther Press

Jim Johnstone, Anstruther Pressoronto ON: It was interesting to catch Ottawa poet Chris Johnson’s latest title, 320 lines of poetry (counting blank lines) (2023) fromJim Johnstone’s Anstruther Press, apparently in my hands before even the authorgot to see copies (this has happened the rare time before over the years withother publishers). There is something about Johnson’s poetry that is intriguingfor the way he is so overtly exploring the lyric through experimentations with formand influence, seeking out a form through which to finally land. His poems areso clearly exploratory, seeking and reaching out to see what might strike, fromhis prior explorations through the haibun to these explorations through elegy, prose poemsand extended lines, with individual poems composed “after” specific works byJessie Jones, Kim Mannix, John Newlove, Artie Gold (his entire prior chapbook was a riff of a specific title by Artie Gold) and Christian Wiman.

Otherpieces in the collection reference specific friends, many of whom also happento be contemporary writers. “the rain has stopped,” Johnson writes, to open “somedays are harder than others,” “but Monty says / there is always something /with bigger holes in it.” There are moments that the poems do fall too deeplyinto the self-referential, such as the opening poem, “elegy for chris johnson,”offering “today I ate a turkey sandwich and / thought about stephanie roberts’turkey sandwich.” Throughout this piece he cites and he references, but doesn’tseem to offer really anything more than that, so the poem is intriguing, but doesn’treally seem to go anywhere. There are times that his line breaks do offer some nicelysharp turns, moments and corners, such as the opening of “when does the hungerbegin?”: “the last days of February were honeyed, / snowy, and enlightened bywhisky and weed.” That’s some fine precision, there. As well, there are momentswithin his prose poems where the music in his lyric shows itself quite nicely, whetherthe poem “asleep” (after “Awake” by Kim Mannix) or “a regular person” (after “BetterManifesto” by Jessie Jones). All in all, it feels (in an interesting andpositive way) as though Johnson is still searching, still experimenting; I lookforward to seeing what occurs when he finally lands.

September 26, 2023

Lisa Olstein, Dream Apartment

The same racist neighborswho refer to the Obama presidency with a vile slur are the ones who hauled waterto them, unasked, when their well went dry, who plowed the no-plow road twice aday during his six-week radiation commute, who didn’t tell him his medicalbills were what the green beer and corned beef fundraiser were for until theydropped off the cash, B. tells us over dinner, dismayed, embarrassed. It’s afriendly place to live, if you’re white. Across the valley, the canola field’selectric yellow drains the just-bloomed sweet clover of all its light. Closerin, the Monsanto new product tester’s square green fields leak chemicals intothe wind. He’s a true believer, thinks he’s going to feed the starving world,B. reports. What happens next, I ask hours later gesturing weakly toward the crises,the crossroads, the whatever-you-want-to-call-it we’ve been circling for hours.What happens next, he repeats, what happens next is what we do.

Animal, adjust. (“GLACIERHAIBUN”)

Austin,Texas-based poet and non-fiction writer Lisa Olstein’s fifth poetry titlethrough Copper Canyon Press, and the first I’ve explored of her work—beyond hercollection of epistolary letters co-written with Julie Carr,

Climate

(Essay Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]—is

Dream Apartment

(Port Townsend WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2023). Dream Apartment is a collectionof poems structured across seven clusters of sharp lyrics, each of whichstretch out across incredible distances, as the first, say, forty percent ofthe opening poem, “FORT NIGHT,” reads: “The snake is / a sleeve the deer / putson its mouth / a beaded cuff / in the haze men / make of morning / with eachrelease / of their fist-gripped / guns.” There is an element of Olstein’s DreamApartment that suggest this a collection of dream narratives or dreampoems, offering a subtle play on rhythm, sound and internal rhyme covering lossand an ongoing grief, from the intimate to the external, including aroundclimate. “So spring today, bees in the bok choy / bolted yellow before we couldeat it,” she writes, to open “TO FLEE THE KINGDOM,” “let them eat it instead,let them carry on / carrying its stardust from place to place, // let us alleat, come future come. Meanwhile, / the cat takes, gives a good long bath.”

Austin,Texas-based poet and non-fiction writer Lisa Olstein’s fifth poetry titlethrough Copper Canyon Press, and the first I’ve explored of her work—beyond hercollection of epistolary letters co-written with Julie Carr,

Climate

(Essay Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]—is

Dream Apartment

(Port Townsend WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2023). Dream Apartment is a collectionof poems structured across seven clusters of sharp lyrics, each of whichstretch out across incredible distances, as the first, say, forty percent ofthe opening poem, “FORT NIGHT,” reads: “The snake is / a sleeve the deer / putson its mouth / a beaded cuff / in the haze men / make of morning / with eachrelease / of their fist-gripped / guns.” There is an element of Olstein’s DreamApartment that suggest this a collection of dream narratives or dreampoems, offering a subtle play on rhythm, sound and internal rhyme covering lossand an ongoing grief, from the intimate to the external, including aroundclimate. “So spring today, bees in the bok choy / bolted yellow before we couldeat it,” she writes, to open “TO FLEE THE KINGDOM,” “let them eat it instead,let them carry on / carrying its stardust from place to place, // let us alleat, come future come. Meanwhile, / the cat takes, gives a good long bath.”Thereis an interesting shift of pacing and structure across Olstein’s lyrics, fromthe accumulative staccato of the cluster of poems “ANIMAL,” “SEE IT,” “MOTHERNORTH,” “SPRING” and “GROUP PORTRAIT 1244403” to the five poem prose sequence “GLACIERHAIBUN” to the extended sequence of fragments underneath the title “NIGHT SECRETARY,”and the curve of fragment-accumulation lyrics “AND THEN FOREVER,” “MATERIALFRAGMENTS,” “KINDER SEA,” “YOUR NAME HERE,” “ALL THIS BRITTLE LACEWORK” and “ONLYA FLAWED HUMAN IS YOUR JUDGE” There is such an interesting shift in tone,rhythm and effect through her evolution of lyric structures, one that allowsfor the larger shape of the collection to emerge out of shared purpose amidmyriad structures. “Sorrow what’s my ration tonight,” she writes, as part of “NIGHTSECRETARY,” “full portion [.]” The back cover offers that this collection is “Devotedequally to the long arc and the sharp fragment,” and each shape and patterattends uniquely to the music of each line, offering a precise and dreamyeffect through her examinations, and even negotiations, on how one lives ormight live in the world. As the poem “KINDER SEA” begins:

There in the tremblingport

of morning who knew yet what

wriggled in the net pulled in the

predawn and slapped down on

the rough dock offuel-flowered

air?

September 25, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Patti Grayson

Patti Grayson

is the author of two award-nominatednovels and one award-nominated short fiction collection. Her debut novel,

Autumn, One Spring

, was translated into German and was a popular book clubselection. She lives and writes from the prairies.

The Twistical Nature of Spoons

is her fourth book and was published in fall of 2023.

Patti Grayson

is the author of two award-nominatednovels and one award-nominated short fiction collection. Her debut novel,

Autumn, One Spring

, was translated into German and was a popular book clubselection. She lives and writes from the prairies.

The Twistical Nature of Spoons

is her fourth book and was published in fall of 2023.1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

The first bookchanged the interior of my life within the context of personal accomplishment.Following publication, I received an email from a high school acquaintance thatread: “You’ve managed to fulfill your dream.” At that point, I was in my 40s,and it was surprising to me that people who knew me in my teens understood and rememberedthat I’d aspired to become a writer. Having the first book out in the world allowedme to refer to myself as an author without a full-blown imposter-syndromeattack every time. And my exterior world was definitely enriched. Publicationprovided me with opportunity to encounter readers and to engage with peers atvarious events. Both those aspects were very rewarding.

I’m hoping that thenew work reveals that some writerly growth has taken place. Structurally, this novel is more complex thanany of my previous projects, which were all more straightforward narratives.This work definitely feels more strenuous.

It also feels moreinstinctual—metaphorically speaking, there was less checking over my shoulderin the fear that validation was refusing to follow me down the path. For betteror worse, I granted myself permission to proceed unaccompanied with what I wascreating.

2 - How did you come to fiction first,as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Actually, when Idecided to become serious about my writing, my initial focus was poetry, andalthough I never pursued a collection, I did have pieces published in literaryjournals before I turned to short fiction. I’d always favoured poems that leanedtoward storytelling, so it felt natural for me to begin to concentrate onnarrative fiction. Once I started writing short stories in earnest, I suddenlyfelt that I’d never be able to write another poem. It was almost as if thatarea of my sensibilities sealed shut and was no longer accessible. For me,poetry and fiction remain quite distinct from one another in terms of what theyask of me as a writer. Non-fiction terrifies me, so that was an easy evasion.Fiction continues to be my preferred fit.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to plungeright in when I get an idea, but then the process most often turns into a slowcrawl. I think it would be helpful if I could work from an outline (sometimes,when I start revisions on a completed draft, I have to create a thumbnail chaptersummary for quick reference, but I’ve never started with or followed an outlineotherwise). I seem to prefer the wandering, loitering, and dithering thatresult from the lack of one.

When it comes torevising, my projects have varied in terms of number of drafts, and of theoverall overhaul that they produce. I also do tend to become obsessed withminutia; I can easily spend an entire morning reconstructing a single sentenceand then delete it at noon.

4 - Where does a work of prose usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Each of my publishedworks has originated in a different manner. Core Samples was adetermined march toward accruing a collection of short stories. Autumn, OneSpring was originally a series of connected stories which were intended toserve as the backbone for Core Samples, but I pulled them out at a latestage and replaced them. I felt that the main character wanted more of myattention, and that perhaps I was ready to tackle a novel for her sake. Thoseconnected stories were significantly altered when I subsequently began thelarger project—but their solid roots remained. Ghost Most Foul, my novelfor younger readers, came from a single spark of inspiration that was literallygifted to me while I was taking a walk with my dog. The entire story arc presenteditself, and every time I sat down to start a new chapter, its purpose anddirection were clearly defined in my head (despite not having an outline). Atthe opposite end of the spectrum, The Twistical Nature of Spoons, mynewest adult novel, has had numerous false starts, including the completion of ahefty number of chapters for a forerunner that was totally abandoned (otherthan one minor character and the vague essence of a single scene that insistedon accompanying me out of the debris). Spurred on by research that led me downabsurd paths and produced notebooks of ideas that were never included, Ifinally did manage to write one-half of a chapter that I knew immediately wasgoing to stick. What it was going to stick to was a complete unknown, but itroused enough curiosity in me that I was compelled to find out, and see it throughto completion. I’d have to say that I equally despaired and revelled in myinefficiency.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

Despite theanxiety they instill, I love to take part in public readings. Reading aloud ispure joy to me, and sharing with an audience is bliss.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

At times, I’m plaguedby the question of relevance in my own work. Why not leave the writing of booksto those who have wider scopes—those who are more politically situated or who havemore socially relevant stories to tell? Wouldn’t it be prudent to leave it towriters who are addressing environmental issues, race relations, humanatrocities, the increasing polarization of ideologies, economic disparity, theencroaching dominance of social media in our lives?

But there areother aspects to our humanity that exist within the scope of our daily lives.I’m drawn toward those more interior factors and feel compelled to explore themcreatively. We all live within the framework of our families and ourrelationships, and within the context of community, be it geographical,cultural, or endeavour-based. The everyday questions that swirl within thoseboundaries fascinate me. What drives human beings to forge bonds, betray, aspire,achieve, jump to conclusions, accept defeat, hold a grudge, love, harm, hope? Whatmakes us human? And what can we do about that? These are my questions.

7 – What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

As I ponder thesequeries, the WGA (screen writers) strike is ongoing, and there is anever-widening discussion of the threat of AI within the creative community at large.I think the role of the individual writer is so crucial within society today toensure that humanity’s story is safeguarded and continues to be widely interpreted—whetherit’s recording broad-sweeping historical moments, or creating the scene inwhich a fictional character raises an eyebrow and pandemonium breaks loose.

Yes, AI canstring together sentences from data bases too large to imagine, but it can’t smellthe sweetness of a baby’s head, can’t feel the stinging cruelty of a racialslur, or slowly emerge from under the heavy blanket of a close friend’sbetrayal. AI can think it knows these things, but it doesn’t. Writers do, andcan tell us about them in a way that is uniquely their own.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve justrecently wrapped up the editorial process on my new novel, and both thesubstantive edit and copyedit were definitely essential. With my editors’ keeneyes on the manuscript, I was afforded a glimpse of the work from outside myown head, and the book benefitted from the collaborative efforts in terms of diggingdeeper and adding vertical depth. I’ll admit the process of addressing all theeditorial notes was challenging—at times, exhausting—but absolutely worth it.

Improvisationaltheatre is mentioned in this book, and one of improv’s guiding principles is the“yes, and” rule: If someone presents an idea, you say “yes, and” adding thenext idea to build the scenario, rather than saying “no” and blocking the scene.I decided to try and adhere to that rule during this book’s editorial process. Irecall one particular substantive suggestion that seemed quite unworkable to me,so I tamped down my resistance with the “yes, and” rule. The revisions that Imade, using my editor’s suggestion, not only resolved the original concern, theyadded extra value. The suggestion was also a far more natural fit than I firstimagined possible when my initial impulse was to question or reject it.

I couldn’t bemore grateful to all the editors I’ve worked with on each of my books.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When it comes towriting advice, I can never get enough of others’ wisdom. I do, however,consistently rely on one single, straightforward suggestion that I receivedfrom a mentor: “Just keep your derrière in the chair.”

Recently, afamily member gifted me a thirty-minute hourglass timer that complements thatbit of advice. It’s a beautiful object, and while the sand is descending, I’mvery reluctant to get up and walk away from the keyboard. Turn the hourglassover a couple of times, and something usually gets accomplished simply becauseI’ve stayed put long enough to do the work . . . perhaps even long enough tohave entered the “zone” where time falls away, and upon resurfacing, I have noidea when the hourglass last clocked out.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (novels to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t tend tobe one of those writers with multiple, concurrent projects actively on the go.I literally do full stop on one before moving to the next (that has happened tome while smack dab in the middle of a project). However, after taking abreather, my plan is to turn back to short stories for awhile, and I doubt Iwill even think about the longer format again until I’m story-satiated.

As for appeal,I’ve been totally content residing in one novel’s world for quite a few yearsnow; it will be equally satisfying to bop in and out of places for shorterdurations, an aspect that the short story accommodates more readily. For me,the appeal is the immersion—disappearing into the work—regardless of theformat.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

In early days, Iused to be quite consistent at writing in the mornings until about 2 p.m.Within that system, there would often be gaps of several months, but then I’dreinstate. That routine is no longer in play. It’s been replaced by a catch-as-catch-cansystem, and if that means 2 a.m. insomniac writing, I give in, get up, and doit. I still believe that breakfast at my desk with a large pot of Earl Grey teais the ideal way to start a writing day.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I’m stalledout on a specific problem, listening to music always helps. It seems to “pop” me out of the negativedoubts and struggles. Sometimes I dance along. (In the past, I’d often turn tolong walks or long showers/tub soaks to free up my mind).

If a more generallack of commitment is circling, there is no better way to motivate me againthan to pick up a book and read. Contemplating the work of others justnaturally inspires me to want to create again. Fortunately, the sources forthat stimulus abound! (I will never complete my bedside TBR stack because mycompulsion to add to it reigns supreme over my ability to reduce it).

13 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Evergreens/haylofts. I’m half Canadian Shield/half Prairie.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Apart from theaforementioned music, I do turn to the visual and theatrical arts for stimulus.Nature is providing more rejuvenation than inspiration as of late. Socialscience tends to take the win over science for me, although my abandoned novel containeda scientific component that excited me—perhaps that will resurface.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many writershave influenced me and continue to do so. I’m not sure I would have everimagined becoming a writer if I hadn’t encountered the work of Margaret Atwoodand Kurt Vonnegut in my early days. Since then, I’ve stayed the course with Ms.Atwood, but there have been dozens of other contemporary writers along the way whosebooks have taught me, inspired me, changed me, or expanded my understanding ofhow to situate myself within my own work. My incomplete list (with apologies tothe many not mentioned) includes: Alice Munro, Di Brandt, Catherine Hunter, Margaret Sweatman, Katherena Vermette, Wayne Tefs, Sheila McClarty, CS Richardson, Joshua Whitehead, Patrick deWitt, E. Annie Proulx, Douglas Stuart, Zadie Smith,Jennifer Egan, Lily King, George Saunders, Richard Russo, Ann Patchett, Donna Tartt, Maggie O’Farrell.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

Screenplay. Stagedrama. Children’s picture book.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

That’s aninteresting question because I’ve worked professionally at a variety of thingsin my life, including bank teller, hunting/fishing-store clerk, puppeteer,office assistant, trophy engraver, educational assistant, advertisingcopywriter, school librarian, and actor. Another occupation? Concierge? Thinkof the stories!

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

As indicated inthe previous answer, I’ve done a fair bit of the ‘something else’, but I’d haveto say that being told that I was a good writer by teachers probably had a lotto do with me pursuing the written word. (I loved school in that teacher’s petkind of way. During my elementarygrades, my spare time was filled with visiting the library and writing my ownstories).

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

I’m answeringthis question strictly on the basis of most recent . . . I just finishedEleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood, and so admired her ability to maintain adiscourse on societal issues alongside a captivating portrayal of characters ina snarl of subtle, oscillating power balances. The last film I viewed was Coda(not the recent Academy Award winner, but a film by the same name, directedby a Canadian and partially shot here). It’s a film that invites contemplation about classical music, self-doubt,aging, and grief—understated and ‘engaging’ (TNG Trekker pun was unavoidable).

20 - What are you currently working on?

At present, ashort hiatus is on the schedule as I prepare to launch The Twistical Natureof Spoons, but my husband and I have recently been discussing the law ofunintended consequences (or the knock-on effect), and I’m curious as to how Imight create a short story around the concept. Hopefully, its unintendedconsequence will be a positive outcome with an unanticipated benefit. Fingerscrossed.

September 24, 2023

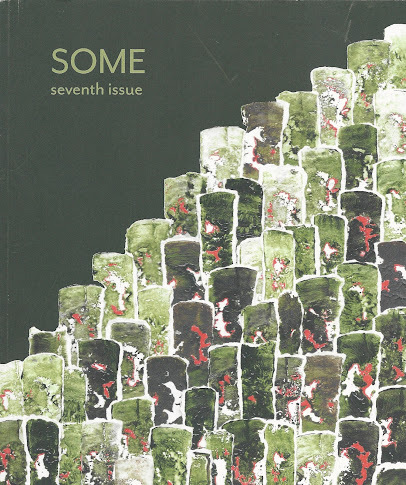

SOME: seventh issue,

Creeps

Old creep

staring at blooming,

solid flesh,

remembering home. (RaeArmantrout)

I’malways interested to see the latest issue of Vancouver poet Rob Manery’s SOMEmagazine, and the seventh (summer 2023) landed on my doorstep not that longago. Compared to the issues he’s produced-to-date [see my review of issue six,issue five, issue two], this issue appears to focus on literary elders (each ofthis list began publishing their work in journals in a range that extends fromthe late 1950s—as with George Bowering—into the 1970s). One might say thatexperiment without attending our influences can lose foundation, so theacknowledgement is one appreciated, and this issue includes extended poems, sequencesand prose by Rae Armantrout, George Bowering, Phil Hall, Lionel Kearns, Ken Norris and Renee Rodin. There is something of Rae Armantrout’s work that I’vealways found reminiscent of the structures of poems by Ottawa poet Monty Reid,in the way they both extend small moments, stretching them out further than onemight think possible. Reid does this in part through the physical line, which Armantroutbreaks for the sake of slowness, pause, extending moments into a particularkind of simultaneous extended and sharper focus. She writes in portions, insections, and her contribution of five poems are incredibly sharp. As thesecond half, second section, of her poem “First Born” reads: “To be present /is to start, // to feel a flash / of dread // when opened. // Dead the eldest /child of what?”

I’malways interested to see the latest issue of Vancouver poet Rob Manery’s SOMEmagazine, and the seventh (summer 2023) landed on my doorstep not that longago. Compared to the issues he’s produced-to-date [see my review of issue six,issue five, issue two], this issue appears to focus on literary elders (each ofthis list began publishing their work in journals in a range that extends fromthe late 1950s—as with George Bowering—into the 1970s). One might say thatexperiment without attending our influences can lose foundation, so theacknowledgement is one appreciated, and this issue includes extended poems, sequencesand prose by Rae Armantrout, George Bowering, Phil Hall, Lionel Kearns, Ken Norris and Renee Rodin. There is something of Rae Armantrout’s work that I’vealways found reminiscent of the structures of poems by Ottawa poet Monty Reid,in the way they both extend small moments, stretching them out further than onemight think possible. Reid does this in part through the physical line, which Armantroutbreaks for the sake of slowness, pause, extending moments into a particularkind of simultaneous extended and sharper focus. She writes in portions, insections, and her contribution of five poems are incredibly sharp. As thesecond half, second section, of her poem “First Born” reads: “To be present /is to start, // to feel a flash / of dread // when opened. // Dead the eldest /child of what?”GeorgeBowering gets a pretty hefty section in this issue, a sequence of twenty-fourshort lyrics under the title “Divergences” that feel reminiscent of some of thepoems in his Teeth: Poems 2006-2011 (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2013)[see my review of such here] and Could Be (Vancouver BC: New Star Books,2021) [see my review of such here], and even through his collection SmokingMirror (Edmonton AB: Longspoon Press, 1984), through the use of the short,lyric burst, although one that extends across short stanzas as a loosenarrative thread down his usual seemingly-meandering but highly purposefulcadence. Although, one might say, there’s a calm resoluteness to these poemsthat differs from his other work; the electrical energies of his prior lyricsare quieter here, seeking a kind of intimate calm. Ever since working his one-chapbook-a-month-year-long-manuscript,My Darling Nellie Grey (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2010) [see my review of such here], Boweringappears to be more overtly working sequences of chapbook-length sequences, eachof which he seems to attempt to each get into stand-alone publication beforethe publication of the full-length collection; given the reluctance of literaryjournals to publish such long stretches across a single author, he’s focused onchapbook publication, so this sequence, whether it be part of something largeror not, does appear to be one of those rare journal placements. As Boweringwrites as a kind of afterword to the poems: “Each of the sequence’s 24 sectionsbegins with a line or two from the start of a Romantic poem of the 19thcentury, then diverges into something from the mind/soul/mood of the presentold poet. You may notice that Goethe gets pilfered from twice. That was an accident.It takes, they say, nine accidents to kill a cat. Which is odd, because curiositymeans carefulness. It is also the last word of the poem. Poems, the old poetthinks, are made through accidents and carefulness.” His first poem in the sequence“Divergences” reads:

Open the Window

Open the window, and letthe air

freshly blow fromtreetops to faces

that care not.

They are turned

heedless away from theblue sky

they will never glancewhile some

they do not see arelowering

them beneath fresh air’s reach.

Perth,Ontario poet Phil Hall’s contribution to this assemblage are three poems fromhis forthcoming collection Vallego’s Marrow (Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2023) [see my review of his 2022 title with the same publisher, TheAsh Bell, here], a title that should be out somewhere in the next couple ofweeks. The poems here offer a continuation, a furthering, of Hall’s uniqueblend of lyric first-person essay, swirling through memoir, memory, literatureand what I’ve referred to in the past as a kind of “Ontario Gothic” almost folksycharm. Hall’s straight lines are never straight; his lines have a way ofturning, moving, altering in tone and shape while retaining direction, akin to whitelight through a prism. There is such a scope of length to Hall’s ruminations,one that seems to extend with, and even through, each new poem, each newcollection. “I see my dead parents as characters in fables / or extinctcreatures trapped in an old story,” he writes, as part of the first of thesethree poems, “there is no memory that has not savaged or been savaged / atongue is eaten & thumb grease sees through a page // now here comes my ownlittle train / the doors of its empty boxcars rusted open on both sides //black fields black fields black fields black fields / I can see through eachclanging frame [.]” Lionel Kearns is one of those Canadian poets that I don’t thinkhas ever been given his due, in part, I’m sure, through the fact that he doesn’tpublish books terribly often. An early experimenter with form (his authorbiography includes the note that “His most anthologized work, Birth of God /uniVers, first published in 1965, stands today, in its various forms andformats, as one of the earliest examples of digital art.”), his contribution tothis issue sits under the umbrella title of “Selections from Very Short Essays,”each of which sits, stand-alone, as text within a box shape. The poems readakin to koans, offering compact lyrics and twists in the language.

Ofthe eight poems included by Ken Norris—originally American, then Montreal, backto Maine and now retired in Toronto—the first two offer themselves as projects,responding to the works of poetic influence: “The Wordsworth Project” and “TheShakespeare Project.” “To realize the full variety of humanity.” the second ofthese begin, “To get it all down in a cast of characters.” Each of Norris’poems in this assemblage are slightly different than where his poems often go [seemy review of his 2021 Guernica Editions title, South China Sea, here],offering a broader overview of thinking, reading and response. After somethirty or forty-plus poetry collections since the 1970s, there is something of Norrisonce again seeking out origins, even legacy, perhaps, through these shortnarrative lyrics. Or, as he offers as part of the poem “Cultural Marginalia,” apoem dedicated to Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell, “Louis [Dudek] said we werekibitzers, / and I guess that’s true. My poems have never been / broad culturalstatements. // Someday someone will realize I was speaking / to them, for them.”Vancouver poet Renee Rodin is another poet too often not given her due, and forreasons similar to that with Kearns: her biography references her Talonbooks published in 1996 and 2010, respectively, as well as a chapbook with Nomados in2005, now long out-of-print. Her two-page prose piece included here is “Here inthe Rainforest – The Lighter Version,” a piece composed “during the invasion ofUkraine and the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria” that begins:

Suddenly the morning isdark, hot water cold, no heat, no stove. My phony landline doesn’t work,cellphone almost dead. The last text is from a friend, also in Kitsilano,asking if my electricity is out too.

Cut off fromcommunication I panic. My kids are long distance calls away, there’s nothingcloser that the sound of their voices. Now I’m scared they might need me andwon’t be able to get through. I find this thought unbearable.

Here in the rainforest we’vehad a severe drought, I loved the months of sunny, warm days. To not enjoy thebeautiful weather would have only compounded the waste. Today we’re having anatmospheric river, a lovely sounding name for prolonged pelting rain.

Rodinhas long utilized the prose lyric, similar to the work of Vancouver writer Gladys Hindmarch [see my review of Hindmarch’s 2020 collected, published by Talonbooks, here], as a way in which biographical threads are offered as thestructure through which she is able to comment on all else. Similarly toHindmarch being a prose counterpart to the 1960s TISH poets, Rodin’swork feels akin to emerging as a prose counterpart to the poetry experiments inand around Vancouver of the 1970s and 80s, all of which made Rodin, andHindmarch as well, literary outliers. There is a seriousness to Rodin’s work,an ecological and social engagement, that underlies much of her work as well. Onewould hope we might even see another collection at some point, hopefully soon.

Thecolophon to the issue reads: “Contributions and email correspondence can besent to somepoetrymagazine@gmail.com / Subscriptions are $24 for two issues. Singleissues are $12. E-transfers are welcome.”

September 23, 2023

the genealogy book : (a new work-in-progress,

Nearly a year ago, I started a substack for the sake of prompting a particular writing project, and have just started posting from the most recent work-in-progress, "the genealogy book," the first two of which are now available here and here. Since my teens, I've been the self-designated genealogist for my family, and spent years working through a variety of archives to piece together innumerable threads of genealogy. Through this, I've been fully aware that I was adopted, and had other threads as well, but I've only been learning them over the past few years, and am now pushing further to explore those threads, and what that potentially means, through a non-fiction project. If I self-identified so heavily through one set of threads, only to be presented with a whole slew of alternate threads, how does that fit in with my consideration of self? What does it all mean?

Nearly a year ago, I started a substack for the sake of prompting a particular writing project, and have just started posting from the most recent work-in-progress, "the genealogy book," the first two of which are now available here and here. Since my teens, I've been the self-designated genealogist for my family, and spent years working through a variety of archives to piece together innumerable threads of genealogy. Through this, I've been fully aware that I was adopted, and had other threads as well, but I've only been learning them over the past few years, and am now pushing further to explore those threads, and what that potentially means, through a non-fiction project. If I self-identified so heavily through one set of threads, only to be presented with a whole slew of alternate threads, how does that fit in with my consideration of self? What does it all mean?Through the substack, I'm aiming to post weekly, with every third or fourth post for paid subscribers only (I mean, I have to give some incentive to sign up with money). The substack originally started to prompt my non-fiction "Lecture for an Empty Room," a book-length essay on literature, small press, community and responsibility, so there's a bunch of pieces on there for that. The weekly prompt I originally gave myself for posting sections on this blog of the manuscript-in-progress that eventually became my pandemic-era memoir, essays in the face of uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022), worked out pretty well, after all. As well, I was posting fragments of a forty-ish page essay I had worked on, "A river runs through it: a writing diary," composed during the months that Denver poet Julie Carr and I were actively working on our collaborative poetry call-and-response. Other threads via the substack include a two-part essay on above/ground press, a variety of self-contained short stories, and the sprinklings of a journal project from 2019-2020 around genealogical discovery, Christine's health and my father's illness and eventual death, "the blue year." I've also been posting self-contained essays on fiction writers as part of an ongoing series titled "reading in the margins: a writing diary," with some new pieces forthcoming, hopefully, on Lucy Maud Montgomery, John Lavery and Dany Laferrière, among others. Since starting, I've tried to treat the substack as a kind of weekly column, and the trickling of support from such has been helpful, although the big push is really to get me writing further and deeper into these ongoing prose explorations. Why not sign up? Who knows what might come next? And I'm completely fine with folk signing up gratis; the working-class farm lad in me always thinks that lack of finances should never be a hurdle to engaging with literature, after all.

September 22, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kimberly Reyes

Kimberly Reyes is the author of the poetry collections

vanishing point.

(Omnidawn 2023),

Running to Stand Still

(Omnidawn 2019), and the chapbook

Warning Coloration

(dancing girl press 2018). Her nonfiction chapbook of essays

Life During Wartime

(Fourteen Hills 2019) won the 2018 Michael Rubin Book Award. Her work is featured in various international outlets including The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Associated Press, Entertainment Weekly, Time.com, The New York Post, The Village Voice, Alternative Press, ESPN the Magazine, Film Ireland, The Irish Examiner, Poetry London, Poetry Ireland, RTÉ Radio, NY1 News, The Irish Journal of American Studies, The Best American Poetry blog, poets.org, American Poets Magazine, The Feminist Wire, and The Stinging Fly. Kimberly has received fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, the Academy of American Poets, the Fulbright Program, CantoMundo, Callaloo, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Tin House Workshops, The Irish Arts Council, Culture Ireland, the Munster Literature Centre, the Prague Summer Program for Writers, Summer Literary Seminars in Kenya, Community of Writers, and other places.

Kimberly Reyes is the author of the poetry collections

vanishing point.

(Omnidawn 2023),

Running to Stand Still

(Omnidawn 2019), and the chapbook

Warning Coloration

(dancing girl press 2018). Her nonfiction chapbook of essays

Life During Wartime

(Fourteen Hills 2019) won the 2018 Michael Rubin Book Award. Her work is featured in various international outlets including The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Associated Press, Entertainment Weekly, Time.com, The New York Post, The Village Voice, Alternative Press, ESPN the Magazine, Film Ireland, The Irish Examiner, Poetry London, Poetry Ireland, RTÉ Radio, NY1 News, The Irish Journal of American Studies, The Best American Poetry blog, poets.org, American Poets Magazine, The Feminist Wire, and The Stinging Fly. Kimberly has received fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, the Academy of American Poets, the Fulbright Program, CantoMundo, Callaloo, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Tin House Workshops, The Irish Arts Council, Culture Ireland, the Munster Literature Centre, the Prague Summer Program for Writers, Summer Literary Seminars in Kenya, Community of Writers, and other places. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I didn’t, haha. Unless you win a major award it doesn’t really change your life and you realize you’re a writer so you keep writing. vanishing point. is similar to my previous work in that it represents significant years of my life -- I don’t pretend that my work isn’t mostly autobiographical. And It feels different from my first book in that it’s a bit more experimental in form.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I didnt come to poetry first, I was a journalist first so prose was and will always be my bread and butter, I for sure still write nonfiction. Poetry is just my true love that doesn’t pay. It keeps me sane, although I guess sanity is relative.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Such a good question. It really depends on where I am mentally and readings serve as barometers for that. I can tell if I feel situated and if I have community by how comfortable I feel in a particular place and time at a reading. So sometimes I enjoy reading and sometimes I dont. And as far as my creative process I don’t really know if i connect giving readings to that but I am certainly inspired by hearing certain poets read.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

God yes. I mean what is this all for? Is the human condition worth it? Do we take these lesson with us? Does it all even out in the end or are all of these injustices meant to just eat at us until the end of time? Why why why?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To try to make sense of things and to try to make this existence a bit more bearable for ourselves and for each other.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I absolutely LOVE working with editors! I think it’s such a privilege when someone takes you and your work seriously enough to engage with it in a meaningful way, to ask questions, and to challenge you to do better. A good editor really needs to be engaged beyond the surface level and when that happens I’m always appreciative. I’ve noticed that the practice of editing is disappearing, especially from smaller, underfunded presses, and it’s sad. Attention is the most valuable currency there is.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Rising pizza dough and hot trash (I’m from NYC).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a screenplay. I’ve become hooked on poetry films and seeing my work come to life visually so I’d love to see that happen on a larger scale.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d love to be a small shop owner, maybe selling crystals or baked goods in the countryside. Something without deadlines in the way I’m used to, where my day to day is an actual day to day that I can’t predict.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don’t know if I ever really had a choice. My teachers told my parents it was something I should pursue ever since elementary school and then I was always writing for my school papers so I assumed I’d be writing for magazines and then I saw Almost Famous while I was in college and I was like: Done! This kinda ties back into the screenplay thing, I guess I just wanna be Cameron Crowe.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great book: Wanda Coleman’s Wicked Enchantment

Last great film: Aftersun.

20 - What are you currently working on?

My next book for Omnidawn while trying to stay sane in my PhD program. If the book comes out and I’m a doctor in 2025 I will have succeeded.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;