Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 74

October 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nathan Mader

Nathan Mader is fromSaskatchewan and lives in Kyoto. His poems have been in The Fiddlehead, Plenitude, The Ex-Puritan, TheAntigonish Review, PRISM, TheNew Quarterly, and The Best Canadian Poetry 2018(Tightrope Books). The EndlessAnimal, his first full-length collection, is forthcoming in winter 2023 from Fine Period Press.

Nathan Mader is fromSaskatchewan and lives in Kyoto. His poems have been in The Fiddlehead, Plenitude, The Ex-Puritan, TheAntigonish Review, PRISM, TheNew Quarterly, and The Best Canadian Poetry 2018(Tightrope Books). The EndlessAnimal, his first full-length collection, is forthcoming in winter 2023 from Fine Period Press. 1 - How did your first book change your life?How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

My first full-length book of poems, The Endless Animal, will be out thiswinter and what might follow is a total mystery, but the process of gettingthis book ready for publication seems to have changed, whether positively ornegatively, my relationship to composition. Choosing the right, single poem torepresent a particular energy or angle on something—even if it means cutting apoem I like on its own—has made me more judicious.

2 - How did youcome to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Encountering Macbethin 10th grade English changed everything! I was never a great student orhuge reader in high school, but I remember becoming obsessed by Shakespeare’s queerand queering language, becoming aware for the first time of the textureand music of particular words, the way the combination of sound and sense couldbe magnetized to articulate primal forces of existence in ways nothing elseever had—I was hooked, but it would be years before I dared to write anythingapproaching poetry of my own.

3 - How long doesit take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initiallycome quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close totheir final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Some rare poemscome quite quickly and nearly fully-formed, others are built glacially slow oneline (often one word, sometimes onesyllable) at a time before they feel “right.” Usually the first line comes froma voice, an image, a memory, a rhythm that arrives from somewhere charged with lyricpotential, and the rest of the poem is called forth from there.

4 - Where does apoem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

For me, thehammering and chiseling of revision iswriting—the source of the initial gesture is from somewhere beyondregular consciousness. I often experience poetry, both reading and writing it, assomething very embodied—it begins with a tingling at the base of my skull andends with a sometimes pleasurable, sometimes sheer feeling of exhaustion whenthe poem is finished with me. One of my friends joked that I have “poetryASMR,” which I love, but I’m hesitant to give the place where poetry comes froma name. I don’t really think in terms of books or projects because of feelslike each poem is its own animal. If shaping a poem is one of seeing what eachline might have to say to each other, shaping a book has been one of seeingwhat different poems might have to say to one another.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings canbe a good reminder that poetry is both an act of communication and anincantation, and if an audience responds well to a poem, this can be taken as agood sign the poem is working. For me, poetry lives as much in the voice as onthe page, and I often make recordings of poems as I revise them to this end.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I’ve always lovedwhat Paul Muldoon says: “a poem is an answer to a question it itself has raised.”

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Except in times ofcrisis, the larger culture seems to care very little for poets and poetry—butthat’s okay. Opera and interpretative dance share the same fate. But for peoplelike me who need poetry, who hungerfor it, it’s everything. And I’d like to think if poets do have any kind ofrole, it is, as Dickinson says in her great poem, to “Dwell inpossibility.”

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I loved workingwith my editor, the wonderful poet Ivanna Baranova (everyone should get / pre-order her new book from Metatron Press!). She was such an empathetic yethonest reader of my work and essential to the process of getting The Animal Element where it wanted tobe. Ivanna was an “outside” editor in the truest sense because we’d never metbefore, and she shed new light on what many of the poems were up to. I’ve alsobeen fortunate to have friends as first readers of my work who are likewisegifted.

9 - What is thebest piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Can I just takethis chance to say thank you thank you thank you to any poet who has ever beenkind enough to look at one of my poems and / or offer advice? Also, someoneonce told me to turn the wheel into the skid when your car’s spinning out on anicy road—that’s saved my life more than once!

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

A poem can find meanytime—great when I’m on the train, dangerous when barreling down a hillthrough traffic on my bicycle—and I try to always be receptive to it. But I dotend to revise in the mornings after I’ve had coffee and before I have togo to work. Though the strange hours of teaching English as a second languagein here in Kyoto means working weekends and later into the evening toaccommodate office workers, the good thing is that I have most weekday morningsfree to work on things.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

I often take notwriting as a sign I need to be more in the world, to call myself back to myself.Meditation. Movies. Talking to friends. Talking to strangers. Talking to trees.Drawing something. Cycling somewhere. Sex. Silence. In other words, notthinking about writing at all and just being alive and present can help. Butthe biggest reenergizer for my poetry of all is reading a good poem by someoneelse! Often it only takes that single act of attention and reminding myself ofthe eros of language to feel the urge to put down on paper a poem I didn’t knowI’d already been writing.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Diesel engine exhaust.Lavender.

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

The short answer isthat everything influences my art. The long answer is that I mostly grew up onmovies, not books, and they continue to be a big part of my life. When I’mrevising a poem I often “sense” it in terms of scenes, shots, and cuts. But Ialso tend to obsess over all kinds of paintings, photos, and museum artifacts Icome into contact with. People and what drives them are endlessly fascinating,too. Does the nature of desire count as a form of nature? And I hope my worknever turns its back on the animals, human or otherwise—I think a recentencounter I had with an octopus while snorkelling this summer might’ve justchanged how I see the world forever.

14 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

I’ve made a nightlyritual of reading one poem by Dickinson and one by Rilke. Dickinson surpassesShakespeare in possessing the greatest wit in the history of the Englishlanguage, and something about her synapse-snapping speed of thought and formalmastery juxtaposed with the occasionally ostentatious, more often profound mysticismof Rilke in his castle keeps me in touch with the simultaneous wide specturm anddiscrete nature(s) of poetry. I likewise seem to return to Ashbery, Merrill,Schuyler, The Tang Dynasty poets (Li Bai, Du Fu, and co.), Blake, Terrance Hayes, Don Paterson, Richard Siken, Anthony Madrid, Hafez, CAConrad, Ariana Reines, Sylvia Plath, Eduardo C. Corral, The Odyssey, and the poems of my friends and mentors back home in the orbitof Canada, which I can’t bring myself to list out of fear of missing someonewhose work I love. I like to think my desire to feel the world and the word inthese various ways informs both my poems and thinking.

15 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

If the answer tothis question can be open to pure fantasy, I would love to try make a livingoff my poems and nothing else (laughter….uncontrollable sobbing…false stoicresolve).

16 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Sometimes I dreamabout what it would be like to be a Jungian psychoanalyst—to apply some of thegifts poetry has given me—a sense of the interior voice, the ability to thinkless-linearly and in terms of metaphor, symbol, and archetype, encountering subconsciousforces while attempting to “integrate” them—and apply them to people seeking toexplore and / or heal their psyche’s. Wasn’t this part of the poet’s jobdescription in the ancient world?

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

The feeling I getwhen I’m working on a poem was and is better than the feeling I get when I workon anything else.

18 - What was the last great book you read?What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was Robyn Schiff’s fourthpoetry collection, Information Desk (Penguin, 2023). It’s a long poem orshortish epic that stems from her time working at the titular desk in theMetropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the mid-nineties, where the artifacts,art, and everyday interactions she encountered there are recharged with newimplications through the light of lyric memory. I’m also absolutely cuckoo for thepleasurable tension Schiff creates when the propulsive force of her signaturelong sentences meets the formal rigour of her syllabic line breaks.

When it comes to movies, these days it mightbe Tar that has opened the most doorsin my mind: the relationship between power dynamics and the creative drive, theblurred line between art and artist, the entwining of jealousy and desire inboth the artistic and romantic spheres…not to mention the ghosts. CateBlanchet’s performance is so visceral and fascinating, and the director, ToddField, conjures Tarkovsky vibes in the way the he gives silence and atmosphereequal breathing space, and I love that in any film. Barbarian is another somewhat recent favourite movie—too good totalk about.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

Hopefully the nextpoem!

October 20, 2023

Nobody puts Baby in a Corner (Brook,

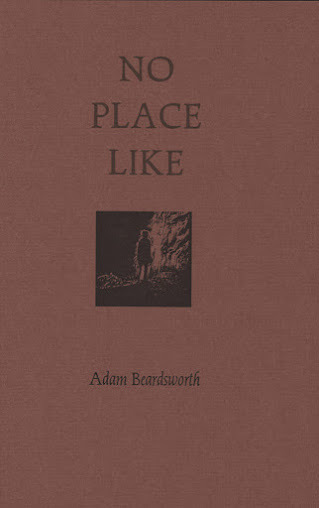

Okay,that’s a terrible title for this particular post, but I spent the weekend inCorner Brook, Newfoundland, participating in the second iteration of theHorseshoe Literary Festival (adjunct to Horseshoe Literary Magazine),which was pretty exciting. Newfoundland: the only province I had not yetvisited! On Thursday afternoon, I caught a flight to Halifax, with a furtherflight to Deer Lake. I spent two hours at Halifax airport, where I drank redwine, ate Mexican food and read Adam Beardsworth’s recent poetry debut, NoPlace Like (2023), from Gaspereau Press [see my review of such here]. Itwas Beardsworth who invited me out for this festival, so I thought the least I coulddo would be to get a sense of him through his work before I arrived. Also, via textfrom the Halifax airport, I did try to convince him (unsuccessfully) that I wasreading his poems aloud to airport patrons to the point that they cheered andheld me aloft (the text chain did get a bit ridiculous).

Therehad been an option for me to leave Ottawa at 6am for the sake of that night’sopen set, but I thought I should be around for school drop-offs instead (beyondnot wishing to take any kind of 6am flight). Instead, I landed at Deer Lakearound 11:30pm local time (the small airport there reminding me of 2004, when Iflew out of Charlottetown: remember that trip? I read with Gil McElroy!), and took a forty-minute cab over to Corner Brook, inconversation with the cab driver the entire time. Apparently Corner Brook is apulp town, and, as I realized, much prettier than Cornwall, but comparable toPrince George (two other pulp towns I’ve spent time in). I landed at the hotelwell after midnight thinking it was only 10pm-something back home and I shouldprobably do something, as I still had loads of energy. I was asleep within minutes.

Fridaymorning: I encountered a woman in the hallway, each of us attempting tonavigate our ways down to the lobby, although I got there first (returning theway I came, I thought, made the most sense; apparently she ended up in the kitchen).We realized we were both festival attendees, as she was Halifax writer Karen Kelloway, a YA author at her first ever festival! So we had breakfast together,and I heard all about her Newfoundland-set new novel

Keepers of the Pact

(Nimbus Publishing, 2023) and her various plans (she even set up a signing at alocal Coles, which seemed both smart and ambitious; far more ambitious than I hadany energy for). After breakfast, I made my way to the Corner Brook sign for aselfie, and then the Great Canadian Dollar Store, where I replaced my travel-mangledsunglasses (I sent Christine a selfie with new glasses: interesting choice, she responded; I'm pretending I'm like Bono, back when he was still cool). I did attempt to wander a bit, find where Matthew Hollett wassetting up his workshop, but couldn’t find him. Once I wandered back from myerratic stretch of walking through the rain, we did meet up for lunch.

Fridaymorning: I encountered a woman in the hallway, each of us attempting tonavigate our ways down to the lobby, although I got there first (returning theway I came, I thought, made the most sense; apparently she ended up in the kitchen).We realized we were both festival attendees, as she was Halifax writer Karen Kelloway, a YA author at her first ever festival! So we had breakfast together,and I heard all about her Newfoundland-set new novel

Keepers of the Pact

(Nimbus Publishing, 2023) and her various plans (she even set up a signing at alocal Coles, which seemed both smart and ambitious; far more ambitious than I hadany energy for). After breakfast, I made my way to the Corner Brook sign for aselfie, and then the Great Canadian Dollar Store, where I replaced my travel-mangledsunglasses (I sent Christine a selfie with new glasses: interesting choice, she responded; I'm pretending I'm like Bono, back when he was still cool). I did attempt to wander a bit, find where Matthew Hollett wassetting up his workshop, but couldn’t find him. Once I wandered back from myerratic stretch of walking through the rain, we did meet up for lunch.

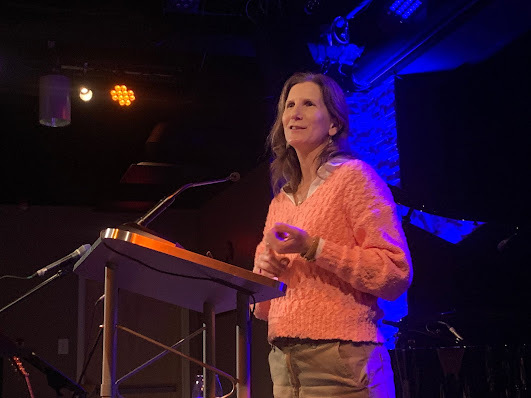

Ihad lunch with Matthew Hollett, I had breakfast with Matthew Hollett, I haddinner with Matthew Hollett, I had breakfast with Matthew Hollett. He isclearly good company. As well, I met up with organizer Adam Beardsworth and hislovely spouse, Shoshanna Ganz [above], at a local (amazing) local brew pub (Bootleg Brew Co.) before the first event. I used to know Shoshanna during her time atthe University of Ottawa, but I don’t think I’d seen her since the Al Purdyconference at uOttawa back in 2006 [see my notes on the conference here; see my notes on the post-conference collection that she co-edited here]. It was a delight to see her! It was almostunsettling to consider how many years it had been.

Ihad lunch with Matthew Hollett, I had breakfast with Matthew Hollett, I haddinner with Matthew Hollett, I had breakfast with Matthew Hollett. He isclearly good company. As well, I met up with organizer Adam Beardsworth and hislovely spouse, Shoshanna Ganz [above], at a local (amazing) local brew pub (Bootleg Brew Co.) before the first event. I used to know Shoshanna during her time atthe University of Ottawa, but I don’t think I’d seen her since the Al Purdyconference at uOttawa back in 2006 [see my notes on the conference here; see my notes on the post-conference collection that she co-edited here]. It was a delight to see her! It was almostunsettling to consider how many years it had been.

That evening included readings by Shelly Kawaja [above], Jiin Kim, Leo McKay Jr. [left], Matthew Hollettand Maggie Burton. Corner Brook-based writer Shelly Kawaja is the author of thedebut novel

The Raw Light of Morning

(Breakwater Books, 2022). I wasquite taken with the short story she read, working through the particulardifficulties of her teenaged protagonist. As it was an unpublished work, she askedfor notes (I had only one, and it was terribly minor). St. John’s-based writer Jiin Kim read from her debut YA novel

Lore Isle

(Nimbus Publishing, 2023)(misspoken by the host as “Love Isle,” which would be a very different book). Ienjoyed the clarity of her writing, and the sharpness of her narrative. There wasa lot going on in that particular book. She was also wearing the mostremarkable (black, shiny, nearly distracting) shoes.

That evening included readings by Shelly Kawaja [above], Jiin Kim, Leo McKay Jr. [left], Matthew Hollettand Maggie Burton. Corner Brook-based writer Shelly Kawaja is the author of thedebut novel

The Raw Light of Morning

(Breakwater Books, 2022). I wasquite taken with the short story she read, working through the particulardifficulties of her teenaged protagonist. As it was an unpublished work, she askedfor notes (I had only one, and it was terribly minor). St. John’s-based writer Jiin Kim read from her debut YA novel

Lore Isle

(Nimbus Publishing, 2023)(misspoken by the host as “Love Isle,” which would be a very different book). Ienjoyed the clarity of her writing, and the sharpness of her narrative. There wasa lot going on in that particular book. She was also wearing the mostremarkable (black, shiny, nearly distracting) shoes.

Leo McKay Jr. read from

What Comes Echoing Back

(Vagrant Press, 2023), andhis easygoing narrative style, built perfectly for public performance, was reminiscentof the work of Michael Blouin: both know very well how to work dialogue, sceneand performance. McKay’s writing was enormously funny, wonderfully dense andquick-witted. And, given how much I’ve encountered him via social media thelast bunch of years, I was actually surprised to realize we hadn’t yet met. Hadn’twe? (I'm still convinced that we did, around the time of his debut.) And of course, Matthew Hollett, who I discovered grew up nearby (hisparents were in attendance). He read from

Optic Nerve

(Brick Books,2023) [see my review of such here], a book I was very pleased to hear aloud. Andhe’s just about the nicest, he is. St. John’s-based writer, performer, classical violinist and city counsellor (what!) Maggie Burton [above] read from her full-length debut,

Chores

(BreakwaterBooks, 2023), an intriguing first-person lyric on women’s labour, relationships,parenting, family history and sexuality. Apparently Burton and Hollett havebeen part of a small group of writers meeting regularly, which is interesting(and fruitful, it sounds). After the event, we discussed children, as she has aplethora of children, including two very small ones (and she had her eldest attwenty, just as I had, so we have that in common).

Leo McKay Jr. read from

What Comes Echoing Back

(Vagrant Press, 2023), andhis easygoing narrative style, built perfectly for public performance, was reminiscentof the work of Michael Blouin: both know very well how to work dialogue, sceneand performance. McKay’s writing was enormously funny, wonderfully dense andquick-witted. And, given how much I’ve encountered him via social media thelast bunch of years, I was actually surprised to realize we hadn’t yet met. Hadn’twe? (I'm still convinced that we did, around the time of his debut.) And of course, Matthew Hollett, who I discovered grew up nearby (hisparents were in attendance). He read from

Optic Nerve

(Brick Books,2023) [see my review of such here], a book I was very pleased to hear aloud. Andhe’s just about the nicest, he is. St. John’s-based writer, performer, classical violinist and city counsellor (what!) Maggie Burton [above] read from her full-length debut,

Chores

(BreakwaterBooks, 2023), an intriguing first-person lyric on women’s labour, relationships,parenting, family history and sexuality. Apparently Burton and Hollett havebeen part of a small group of writers meeting regularly, which is interesting(and fruitful, it sounds). After the event, we discussed children, as she has aplethora of children, including two very small ones (and she had her eldest attwenty, just as I had, so we have that in common).

Saturdaymorning: what did I do on my second full day there? I wandered a bit, seekingout whatever I might find. I found a store that sells collectables, only todiscover that they had a reproduction of the Mona Lisa (I immediately sent to Christinewith a caption suggesting that the one we saw in Paris that time was a completefake; THE REAL ONE IS HERE IN CORNER BROOK). The store also had two differentpump organs from the late 1800s, which I was admittedly tempted by. There werealso a handful of images (portraits, photographs, prints, plates etcetera) of ayoung Princess and/or Queen Elizabeth II throughout. Curious, but I was seekingpostcards. Doesn’t anywhere in this town have postcards? I mean, I found theShoppers Drug Mart, which had stamps; I found the Dollarama, which had somecomics I didn’t have (stop looking at Dollarama, Christine responded; golook at Newfoundland!). Once I found Adam, he offered to take me to the Emporium,a small store a bit further that had a whole array of postcards, which I pickedup. For reasons unclear to me, this store also had a pipe organ, some plateswith the Mona Lisa upon, and a slew of images of the mid-century-era RoyalFamily. I am sensing a particular theme from Corner Brook, Newfoundland. Why wereall these pipe organs brought over, and what has prompted so many to be abandoned?Perhaps one could theorize about the loss of power of the church, and dwindlingattendance forcing churches to close, or even modernize (but that is purelyconjecture, obviously).

Thesecond evening included readings by myself, Allison Graves, Aley Waterman, KarenKelloway [left] and AdamBeardsworth. I didn’t realize until I walked into the reading that I would befirst, but at least it allowed me to actually hear the rest of the readers. I readthe array of poems (a quartet, so far) on our Rose wishing for a fish, gettinga fish, and then having various fish die and be replaced (the latest onlyrecently passed, so I am still working on a memorial piece; the household isalso still deciding on what we might do next). I was taken by St John’s-based writer Allison Graves’ reading; she read from

Soft Serve

(BreakwaterBooks, 2023), her newly-published debut of short stories. Following Graves was Corner Brook writer Aley Waterman [below], recently returned from Toronto, where she’dlaunched her debut novel

Mudflowers

(Dundurn, 2023), a book with somefantastic energy to it. Karen Kelloway moved through folklore and YAexploration reading from her latest novel (which she said has been praised by childrenand grandmothers alike). To close out the readings was Adam Beardsworth [further below], whooffered a precise calm through his ecological debut poetry collection ofattention, elegy and landscape.

Thesecond evening included readings by myself, Allison Graves, Aley Waterman, KarenKelloway [left] and AdamBeardsworth. I didn’t realize until I walked into the reading that I would befirst, but at least it allowed me to actually hear the rest of the readers. I readthe array of poems (a quartet, so far) on our Rose wishing for a fish, gettinga fish, and then having various fish die and be replaced (the latest onlyrecently passed, so I am still working on a memorial piece; the household isalso still deciding on what we might do next). I was taken by St John’s-based writer Allison Graves’ reading; she read from

Soft Serve

(BreakwaterBooks, 2023), her newly-published debut of short stories. Following Graves was Corner Brook writer Aley Waterman [below], recently returned from Toronto, where she’dlaunched her debut novel

Mudflowers

(Dundurn, 2023), a book with somefantastic energy to it. Karen Kelloway moved through folklore and YAexploration reading from her latest novel (which she said has been praised by childrenand grandmothers alike). To close out the readings was Adam Beardsworth [further below], whooffered a precise calm through his ecological debut poetry collection ofattention, elegy and landscape.

[photo of me reading, by Adam]

[photo of me reading, by Adam]Andthe final morning, a breakfast with Matthew, Adam, Shoshanna before she drovemyself and Allison off to the airport, where we each caught our flights home (Iflew through Montreal, myself). Where am I now?

October 19, 2023

Danielle Cadena Deulen, Desire Museum

LAKE BOX

How these dayswill arrive to us later,

later—in asubscription box full of grit and

loamy water,tadpole eggs and a thin skin

of algae—afterall the real lakes have dried

up, so wemight consider how rare they

are, how fine.The eyes of the world forever

closed, we’llsay, paying to walk circles

around thepuddle we’ve poured at the

center of ourrooms, where we walk with

linked arms,the call of nightbirds and

insects andwind through the reeds singing

from ourspeakers, where we will undress

and lay in theshallows, the moonlight

barely reachingthrough the windows to

the circleswidening in the water from the

dropped stoneat the center of our minds.

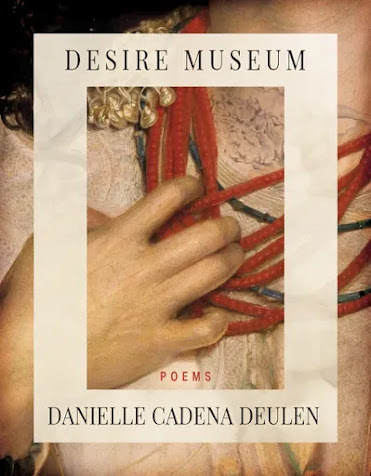

Thefirst I’ve seen by Atlanta, Georgia-based poet, professor and podcaster Danielle Cadena Deulen, following

The Riots

(University of Georgia Press, 2011),

Lovely Asunder

(University of Arkansas Press, 2011) and

Our Emotions Get Carried Away Beyond Us

(Barrow Street Press, 2015), is

Desire Museum

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a curious collection of lyrics set as asuite or sequence of subject-based studies. As the back cover offers, DesireMuseum is “shaped by female-identified embodiment,” and “touches on lostlove and friendship, climate crisis, lesbian relationships, and the imprisonmentof children at the U.S.-Mexico border.” Set in four numbered sections of lyric narrativepoems, I’m intrigued by the variety of lyric structures she utilizes to shapeher pieces, from the prose block to poems that focus on staggered phrases andline breaks, simultaneously focused on the whole unit as well as the lyricsentence, pause and prose line. Her museum holds a menagerie, held together asa singular unit through deep attention and an unflinching gaze. At times, herlines are absolutely devastating. “I used to walk through cities / with thighsso taut men would bless me as I went,” she writes, as part of the poem “SELF-DOUBTWITH INVISIBLE TIGER,” “the thin layer of oil on my cheeks seen as a pretty /sheen. Even then, I knew what they wanted most / was my silence.” Her poems areabsolutely sharp, and I’m fascinated by the way she aims her gaze at a subject,and unfurls across the length and breadth of her examinations, providing bothmeditation and commentary in stunning fashion.

Thefirst I’ve seen by Atlanta, Georgia-based poet, professor and podcaster Danielle Cadena Deulen, following

The Riots

(University of Georgia Press, 2011),

Lovely Asunder

(University of Arkansas Press, 2011) and

Our Emotions Get Carried Away Beyond Us

(Barrow Street Press, 2015), is

Desire Museum

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a curious collection of lyrics set as asuite or sequence of subject-based studies. As the back cover offers, DesireMuseum is “shaped by female-identified embodiment,” and “touches on lostlove and friendship, climate crisis, lesbian relationships, and the imprisonmentof children at the U.S.-Mexico border.” Set in four numbered sections of lyric narrativepoems, I’m intrigued by the variety of lyric structures she utilizes to shapeher pieces, from the prose block to poems that focus on staggered phrases andline breaks, simultaneously focused on the whole unit as well as the lyricsentence, pause and prose line. Her museum holds a menagerie, held together asa singular unit through deep attention and an unflinching gaze. At times, herlines are absolutely devastating. “I used to walk through cities / with thighsso taut men would bless me as I went,” she writes, as part of the poem “SELF-DOUBTWITH INVISIBLE TIGER,” “the thin layer of oil on my cheeks seen as a pretty /sheen. Even then, I knew what they wanted most / was my silence.” Her poems areabsolutely sharp, and I’m fascinated by the way she aims her gaze at a subject,and unfurls across the length and breadth of her examinations, providing bothmeditation and commentary in stunning fashion.

October 18, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jess Housty (‘Cúagilákv)

Jess Housty (‘Cúagilákv)

is a parent, writer and grass- roots activist with Heiltsuk and mixed settler ancestry. They serve their community as an herbalist and land- based educator alongside broader work in the non-profit and philanthropic sectors. They are inspired and guided by relationships with their homelands, their extended family and their non-human kin, and they are commit- ted to raising their children in a similar framework of kinship and land love. They reside and thrive in their unceded ancestral territory in the community of Bella Bella, BC.

Jess Housty (‘Cúagilákv)

is a parent, writer and grass- roots activist with Heiltsuk and mixed settler ancestry. They serve their community as an herbalist and land- based educator alongside broader work in the non-profit and philanthropic sectors. They are inspired and guided by relationships with their homelands, their extended family and their non-human kin, and they are commit- ted to raising their children in a similar framework of kinship and land love. They reside and thrive in their unceded ancestral territory in the community of Bella Bella, BC.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’ve contributed chapters and essays to various anthologies and media outlets over the years, and always had the experience of building my small piece into a thematic whole where it can be read in relationship with the wisdom and talent of other writers and artists. Crushed Wild Mint is my first book, and it’s daunting – and exciting! – to stand on my own.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I grew up spending a lot of time on the land with my father, who wrote and loved poetry. We had a habit from my childhood days of writing poems back and forth in a notebook that stayed in our favourite remote cabin in the wilderness. Although I also write non-fiction, poetry is the form I loved first in part because it was inseparable from my love for my father and that cabin in the wilderness.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to live a very busy life, so poetry is a form that fits beautifully in the margins and bubbles up through the cracks in my day. I find that often poems emerge in close to their final form, but often in fragments over time that have to be fitted together when they’re ready. That said, I’m sure I have thousands of vague post-it notes scattered around my desk as a testament to still unfinished writing projects.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I tend to write shorter pieces that emerge from very specific places and moments, and what binds them together is the motherland – the ocean and land and culture – where I’m rooted. This place defines the larger project, and my poems are just little windows in.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I live in a geographically remote community of 1,400 people, so I don’t often get to attend or participate in public readings. This is the hardest adjustment for me to make with Crushed Wild Mint – getting comfortable with a physical audience in front of me!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m not sure there’s a question I’m trying to answer, but I do want to show people that there is an authentic way of being that is rooted in land love and connection and reciprocity. I try to write without cynicism in a way that does not uphold capitalism, colonization, and patriarchy, one that centers Indigenous joy and thriving and real integration with lands and waters. It’s a beautiful and relational way of living and I hope one that more folks can draw from to feel connected to the places and cultures that matter deeply to them.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I come from a very oral culture where who we are is passed down through the loving and diligent repetition of stories. In this worldview, I think that writers are one modern iteration of the storytellers or oral historians who have always held the role of creating a container for history, knowledge, and identity to be held in. In my culture, the role of a witness is also an incredibly important one, and I think readers as witnesses are equally essential.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I expected to have a hard shell about it, but I found it to be an utter joy! It was so affirming to have an excellent editor who independently identified all the sticky bits of my writing that I’d never quite been able to resolve, and then helped me find my way out of them.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write bad poetry. I tend to get hung up on my own perfectionism, but it’s so liberating to write my own authentic grief or joy without always worrying about the craft of it all. When I let myself write without fretting about how it holds together, I often surprise myself in really good ways.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no routine beyond being present! I admire writers who have routines. I write in little gasps amid a busy life raising kids and working for my community, and then periodically I try to step back and take larger blocks of time for assembling fragments and revising drafts. It’s haphazard, but it’s how my life fits together.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t think I could ever have become a writer without first being a reader. When my own writing process is stalled, I immerse myself in reading books – any books – to bring me out of my frustration and back into my joy and sense of engagement.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

This is a little on the nose, but the fragrance of crushed mint. And I always travel with a little roller of redcedar essential oil to remind my heart of home.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I spend a lot of time in the wilderness and it absolutely influences my work; I’d argue it’s essential to my writing. I also feel my ancestors are a strong influence as I try to live their values and practices and thrive in the landscape where my people have been for hundreds of generations.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love Eden Robinson for her writing and for being the ultimate Auntie to young Indigenous writers. And the work of other Indigenous poets helps me thrive – especially Samantha Nock, Emily Riddle, Selina Boan, Erica Violet Lee, jaye simpson, and Katherena Vermette.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would love to write a piece of fiction! I think that fiction is the ultimate writing challenge – building worlds and crafting narratives that hold together and work with the imaginations of readers. I hope someday I develop my craft to the point that I can explore that form.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I could be anything at all, I’d be an outboard mechanic! Be what you need. Besides writing, I spend my time running a non-profit and taking care of my community, and that’s a pretty sweet gig.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wrote a lot when I was young, then I got caught up in every “something else” that felt more productive and urgent and for years, I almost never wrote at all. I’ve only come back to poetry in a serious way in the last few years as I realized writing is what makes me feel grounded enough to be a good human and do all the other things that give me a sense of purpose.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Heading into the fall I’ve been reading Indigenous literature that gives me chills – Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline for the haunting factor, and My Heart is a Chainsaw by Stephen Graham Jones for some seasonal gore. I’m not much of a film buff, but they’d both pop cinematically if they were made into films!

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working right now on a collection of essays that build my personal story into overarching narratives about place, culture, and wildness. I hope this will find its way into the world next year!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 17, 2023

Adam Beardsworth, No Place Like

Loons

At night with the windowsopened

you hear them on theriver,

their backs mirror thestars,

their deranged cries arethe crack in a

cellar door you want to peekdown,

maybe test the creakysteps,

compelled by the awfulneed to

prove something is downthere,

a shape hidden in themilky black. But

you won’t. It is betternot to know there

is nothing, an emptyriver. Better still

not to be called home bythe lunatic cry.

Iwas fortunate over the weekend to hear Corner Brook, Newfoundland poet Adam Beardsworth read from his full-length poetry debut,

No Place Like

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2023), as part of the Horseshoe LiteraryFestival. Set in three sections of first-person lyrics—“Home,” “Earth” and Sky”—NoPlace Like offer a meditative series of descriptive landscapes, populated bysuch as Robinson Jeffers, border towns, sanctuaries, how to survive a bearattack, youthful folly and suburban sprawl. “Traffic flows downstream,” hewrites, as part of “Biography of a Morning,” “past salmon // fighting thecurrent, past anglers lashing the rip / with flies, jonesing for the hit thatassures // man’s dominion over things.” There is a storytelling shade to hispoems, one that is deeply intimate, focusing a foundation of ecopoetic aroundmemory, moments and domestic matters. “The day I returned from school to find /you crying at the kitchen table / next to the canary’s empty cage,” he writes,to open the short sequence “Sanctuary,” “I learned that happiness is a glass /made of shards.”

Iwas fortunate over the weekend to hear Corner Brook, Newfoundland poet Adam Beardsworth read from his full-length poetry debut,

No Place Like

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2023), as part of the Horseshoe LiteraryFestival. Set in three sections of first-person lyrics—“Home,” “Earth” and Sky”—NoPlace Like offer a meditative series of descriptive landscapes, populated bysuch as Robinson Jeffers, border towns, sanctuaries, how to survive a bearattack, youthful folly and suburban sprawl. “Traffic flows downstream,” hewrites, as part of “Biography of a Morning,” “past salmon // fighting thecurrent, past anglers lashing the rip / with flies, jonesing for the hit thatassures // man’s dominion over things.” There is a storytelling shade to hispoems, one that is deeply intimate, focusing a foundation of ecopoetic aroundmemory, moments and domestic matters. “The day I returned from school to find /you crying at the kitchen table / next to the canary’s empty cage,” he writes,to open the short sequence “Sanctuary,” “I learned that happiness is a glass /made of shards.”Beardsworthcomposes poems in a combination of short phrases and long, languid sentencesthat lope across line breaks, stanzas and a deep earnestness, one that providesa comforting voice, even across multiple threads of elegy, and poemsacknowledging a multitude of losses, from the personal to the ecological. “Beheaded,birds / flew from my neck,” he writes, to open the poem “Elegy,” “warblers,thrushes, hosts of / sparrows, startlings murmured // the shape of an empty heart.”He writes of fathers and sons, and of a beer at the pub, offering fresh meaningand insight across familiar realms. One of the highlights to the collection isthe elegy “Buttercups,” that ends: “a reminder / of the day our lives divergedas you walked into the family / life that fitted like a knitted sweater, as ifto say you still // remembered life before that day, carefree and careless, / butwhat mattered came after, and as this dawns I feel / your hand on my shoulder,pulling me out of the dark // one last time, pointing me towards my son stillsitting / in the sandbox, holding a fresh-picked buttercup to my / bearded chinand smiling, wondering where I have been.”

October 16, 2023

Spotlight series #90 : Jade Wallace

The ninetieth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace.

The ninetieth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock and Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick.

The whole series can be found online here.

October 15, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with A.D. Lauren-Abunassar

A.D. Lauren-Abunassar is an Arab-American writer. Her work hasappeared in Poetry, Narrative, Rattle, Boulevard,and elsewhere. Her first book,

Coriolis

, is forthcoming from theUniversity of Arkansas Press as winner of the 2023 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize.

A.D. Lauren-Abunassar is an Arab-American writer. Her work hasappeared in Poetry, Narrative, Rattle, Boulevard,and elsewhere. Her first book,

Coriolis

, is forthcoming from theUniversity of Arkansas Press as winner of the 2023 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. 1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book is filled with work from so many different stages inmy life. So it means a lot to me in that I can look at something and rememberthe exact moment I wrote it and what was happening in the world then. A weirdkind of time travel and such. To have the book selected by writers I respect somuch, and designed/read/edited by such a generous team, is just something I’mreally grateful for. It’s changed my life because it has taught me how much ateam can come around a bit of writing—teachers, editors, designers,typesetters, publishers, etc. I remember going to all of these poetry lecturesand readings as a student. Once, one writer talked about how the streets nearhis house were all letters of the alphabet. And so, “in learning the alphabet,I found my way home,” he said — or something like that. It reminded me oflearning the alphabet with my father. My dad, in his really thick accent,always pronounced it “etch” instead of H and I loved to mimic this, even thoughit drove my teacher crazy. Years later, I was doing some volunteer work,reading stories with this really little kid who used to say ache instead of H. Three different waysto say one letter and, in learning all of them, I also felt like I wasexploring some city, looking for home. I guess I bring up memories like thesebecause it feels like it says something about my own work and how it’s changedbut also stayed the same. I’m always looking for something, always a bitrestless. The way I look changes—maybe my more recent work is different in thatI’m turning more and more to the stories of others than my own—but the impulseto break something down, even to the letter, is a kind of play for me that’salways present in my writing.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to poetry first as a reader, but a very narrow-minded one.Surrealists confused me. Modernists frustrated me. I struggled to see anythingof the world I grew up in reflected in work that felt, largely, distant tome—maybe a little elitist. So I went to college primarily interested infiction. Then I was so lucky to have some absolutely wonderful teachers. Onebrought a section of Adrienne Rich’s “Cartographies of Silence,” to my firstyear seminar. This has not only stayed my favorite poem, it also helped merealize that there was a world of poetry I never knew about. From there, I justkept reading. I returned to work that frustrated and confused me and hadtotally new experiences with it because I was so much more open to the utility(and importance!) of disorientation. More than anything, I think I began torealize that something doesn’t have to make sense to have meaning. And thatmeaning is a thing you build. You have to be accountable to it. For me, poetryhas always been a great reminder of that. Beyond art, it’s such a nicehuman/life lesson as well.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’m a pretty slow writer. I do keep lots of different notebookswith single lines that will come to me while I’m reading or watching orlistening to something. Sometimes these grow into fuller pieces and sometimesthey just stay lost there. As slow as I usually am, every now and thensomething will come very quickly and usually these are the pieces that are inresponse to something external. For example, a poem I wrote about an article Iread on a lion who ate her cub. After I read the story, the responding poemcame very quickly afterwards because I was in such a hurry to try and live inthat narrative world for a moment. It’s sort of similar with revision—sometimesbecause the piece has taken so long to emerge, it emerges fairly “finished.”More often than not, though, I’m a proponent of really radical revision.Swapping the order of lines. Rewriting an entire poem keeping just one or twoimages from the initial draft etc. Sometimes I’ll find an earlier draft of apoem in a notebook and think, “wow that was totally fine? Why did I scramble itso much?” I think in those cases it comes down to that internal engine we allhave that tells us when we need to keep going to get at something different,even if not necessarily better.

4 - Where does a poem orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I would say I’m typically not writing with a book in mind. Thoughthat could certainly change as I’ve found I do start thinking of larger/longer projectsmore and more lately. I also find that often single poems of mine turn intolarger sequences or series. The same way an essay or a piece of journalism or astory often sets down an obsession that guides the next four or five pieces Iwork on. Maybe for me it has to do with an interest in transmutation (how muchthis mimics memory and life) and how you can constantly push to examine onecentral thing from a new lens/perspective. Maybe it has to do with restlessnessand a sense I’m not quite getting it right, even when I’m getting close enoughto call something ready. For all of these reasons though, questions often markthe beginning of a piece for me. The journalist in me is also very driven byexternal sources: a film I love, a piece of music, even the fun fact on aSnapple bottle cap. I like the idea that a single focused influence can veryoften take up more of me than I expect, growing into something like a book or alarger project as a result.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

They’re definitely not counter to my creative process. I actuallythink attending readings and panel discussions was a monumental influence forme as a younger writer and as a writer to this day. It’s one of my favoritethings to do as an audience member—whether I’m in a creative drought or am veryactively writing. I haven’t quite gotten over that public speaking fear thatmakes reading my own work a little terrifying. But I try to keep pushing myselfand finding opportunities to read because it’s a lovely way to inch outside ofthe isolation writing sometimes enforces. Also, answering questions about mywork, or even just listening to the way something sounds in my voice or another’s,is a great way to get closer to understanding what I really want to be workingon or accomplishing with a given project.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I am someone that gets really paralyzed if I think too much abouttheoretical concerns. So I try to engage with them but limit them. When I wasin grad school, I wrote a poem about a character from Arabic literature. One ofthe critiques of the poem, in workshop, was whether or not I had a right totake on that voice. Several of my classmates spent the majority of the workshopdiscussing this question, not even really getting to the craft of the poemitself. They were concerned that the answer was no, I didn’t really seem tohave the right. It was a troubling experience for me because 1) The assumptionthat I was not Arab myself was incorrect 2) It brought up a whole lot ofexistential tailspinning (am I Arab enoughsince I don’t look as Arab as some of my family, for example, since I’m nottotally fluent in the language, etc.) and 3) It scared me that there was thispossibility we couldn’t engage with certain things that elicit our curiosity aswriters, and that this list of things we can’t engage with are constantlyshifting and hard to predict. Isn’t that an obstacle to empathy? At the sametime, yes—it’s hugely important to me that writing is genuine and that writersare aware of their own positionality AND do not obstruct or co-opt the voice ortradition of another. In that way, I suppose I’m always asking: where is mywork in relation to empathy, honesty, originality? And do I have a reason why I’ve written this? Those are thequestions that feel most important to me.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I guess this is a question I’m always asking (re: the abovequestion) and one I don’t think I ever get totally close to answering. Maybebecause the role of the writer is always changing, especially as the culturechanges. I think it’s important to question, to indict, to reflect, to listen.To engage (internally, externally). There are so many responsibilities androles. But I guess, at the end of the day, I keep coming back to empathy. And Idon’t want to project that onto every writer. I just know that for me, writingis a practice in empathy and is always something that shapes my own understandingof my work and what I feel my role is.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. I think if you find an editor who reads work on its ownterms, it’s not difficult. When you’re editing with someone (say in a workshop)who tends to project the way they would write something on your work, not theway you’ve written it, it can get tricky. I’m constantly guided by thatworkshop mentality of always wanting to hear other people out and try and finda place for their edit in my work. You have to eventually get good at knowingwhich advice to follow though, and which advice to save for another piecealtogether. Still—I always seek feedback and editing from others when I write.It’s essential for me.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t be afraid if you’re lost. When you’re lost, you noticeeverything.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to journalism)? What do yousee as the appeal?

I think I work best, or at least most regularly, in a state ofdivided attention. Writing and watchinga film, for example. Indexing an essay andlistening to a podcast. Because of that, I find myself moving betweengenres constantly. I hesitate to say I move between them easily because writingrarely feels easy to me. But I guess for me the forms are always inconversation. So moving between them is sort of like moving from room to roomall within the same house. I’m turning to writing as a way to explore. Andthat’s where the appeal of working in different genres lies: there are so manynew ways to explore. Where poetry or fiction may feel a little insularsometimes, journalism allows me to engage with the stories of others. Wherejournalism may have more fixed “rules,” poetry or fiction lets me deconstructrules if I feel so inclined. I think it’s so important to embrace a sense ofcuriosity. And different forms of writing allow me to really lean into thatimpulse.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Unfortunately, I’m just not the kind of person who is good atroutine. I end up feeling a little bit too trapped or stilted in them. Thatsaid, I try to write at least a little every day. When I was going through areally bad creative drought, a friend told me to commit to writing fivesentences daily, even if they were really bad ones. And I have found that infollowing that rule, five sentences often turn into a lot more. It’s reallyabout just making yourself start which, for me, has always been the mostchallenging part. I also try to stop writing for the day when I still have alittle more to say. That way I can start the next day with something already onmy mind. Usually, my tendency is to spend the first half of the day gatheringcontent by reading or engaging with outside material of some sort. The writingalmost always comes later. So a typical day would probably start by goingoutside for a little while, taking a walk. Then sitting outside for somereading or research. Basically doing everything I can outside, which helps mesort of “boot up the system.” And though I don’t follow routine by way of doingsomething at certain times, I do have daily habits: Try for one walk a day, tryto watch one movie a day, practice my Spanish and Arabic everyday, write atleast one thing in my commonplace book, etc.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

For me, there is a certain amount of waiting involved in enduring amoment of stall. I’ve found that trying too hard to unblock myself just makesme more frustrated and, as a result, more blocked. Even when I’m stalledthough, I’ll write those crappy five sentences (a teacher once told me toalways remember, “you can’t edit nothing,” and that is something that’s reallyalways stayed with me) and then I’ll step away and just try and stopoverthinking things. Reading has always been my surefire way to get inspired. Ialso go back to old writing prompts. Ekphrastic pieces based on paint swatches,something that responds to something I’ve read in the news, etc. One time, Itold a teacher that I felt blocked because I just kept writing about the sameobsessions over and over and how could I get new obsessions? And he (verywisely) told me it was not about getting new obsessions but finding new ways towrite about the obsessions you have. So doing things like writing a poem aboutgrief using only words found in the dictionary entry for joy, for example, areways I’ll try and look for new light, new perspective. And really, it’s oftenabout churning out a lot of bad stuff so that you can get to what has potentialunderneath it all.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Wet grass. New tennis balls. Sawdust. Sumac. Horse hair. LizClaiborne perfume. Elkalub. Too many!

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’m a really big collector. Old gas lamps, empty cigar boxes,typewriters, whiskey decanters, rolodexes, etc. And I think that instinct tocollect is there in my influences. Which is my way of saying I’m justinfluenced by so much. Nature, always. But also things like John Cage’s “As Slow As Possible,” Ann Hamilton’s “face to face,” Elizabeth Cotten’s folk songsor John Fahey’s requiems. , , Marjane Satrapi, Luis Buñuel, Katie Paterson, Wes Montgomery, Katherine Toukhy, Sarah Knobel, Gordon Parks, Henri Cartier-Bresson… And then yes, science — everything from the pheromones of ants(and animal behavior more generally) to botany to modern and antiquated medicalpractices. I started getting really into watching tennis with my brother a fewyears ago and even something like that feels like an influence, albeit maybe alittle less legible. The movement, the fluidity, the physicality, the sound.And while I find it difficult to actually write without reading, I’d say that maybethe inspiration for actual narratives or thematic obsessions come more oftenfrom things outside of books altogether.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

This list is massive. But a few examples: Adrienne Rich’s “Cartographies of Silence” and the entirety of The Dream of a Common Language beyond that. Etel Adnan — maybe Surge in particular. Joan Retallack’s Memnoir. Anything at all by Lorca.Maggie Nelson (also anything but Bluets first).Toni Morrison (also also anything but I’ve probably reread Song of Solomon the most, especially the section on how the cloudslove a mountain). The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy. Humanimal, Bhanu Kapil. Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams.James Agee, Let us Now Praise Famous Men. David Foster Wallace, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. There are just too many more tolist.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

Writing-wise, I’d love to try writing a play or a screenplay. Idon’t think I’d be any good at either but I’m such a fan of both forms.Non-writing: too many things to list but certainly one of them would be to hikethe Camino de Santiago.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would have loved to work in a library or a bookstore. Or, Ithink, as either a photojournalist or filmmaker. When I was a kid, I used tosay I’d be a professional tree climber.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

It’s hard to say because writing was just always the thing I wasgoing to do. Even if I wanted to be a soccer star or an equestrian or a riverguide, I always wanted to also write. Iguess I think of writing as a place to go as much as a thing to do. And it wasalways a place I kept coming back to.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

I just reread A Tale for theTime Being by Ruth Ozecki and that book never fails to knock me out.Films—maybe The Worst Person in the World.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I’ve currently been doing a lot ofresearch on pilgrimages. And I find that that, along with the concept ofwalking and believing, is finding its way into everything I write at themoment.

October 14, 2023

new from above/ground press: Stebner, Kemp-Gee, McElroy, van Vliet, Cain, Olsen, Cadsby + Williams,

; AGALMA, by Kevin Stebner $5 ; THINGS TO BUY IN NEW BRUNSWICK, by Meghan Kemp-Gee $5 ; Cartesian Wells, by Gil McElroy $5 ; This Folded Path, by Robert van Vliet $5 ; Mayday, by Stephen Cain $5 ; LIVID REMAINDERS, by Geoffrey Olsen $5 ; How to, by Heather Cadsby $5 ; An Extremely Well-Funded Study of Doors, by Evan Williams $5 ;

; AGALMA, by Kevin Stebner $5 ; THINGS TO BUY IN NEW BRUNSWICK, by Meghan Kemp-Gee $5 ; Cartesian Wells, by Gil McElroy $5 ; This Folded Path, by Robert van Vliet $5 ; Mayday, by Stephen Cain $5 ; LIVID REMAINDERS, by Geoffrey Olsen $5 ; How to, by Heather Cadsby $5 ; An Extremely Well-Funded Study of Doors, by Evan Williams $5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material ; see the previous batch of backlist here ,

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

September-October 2023

as part of the above/ground press 30th anniversary

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

And did you see my report on the above/ground press 30th anniversary reading/launch/party?

Forthcoming chapbooks by Saba Pakdel, Lydia Unsworth, Katie Ebbitt, Colin Dardis, Russell Carisse, Micah Ballard, Cary Fagan, Amanda Deutch, Kyla Houbolt, Gary Barwin, Adriana Oniță, Noah Berlatsky, Blunt Research Group, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Zane Koss, Peter Myers, Ben Robinson, Miranda Mellis, MLA Chernoff, Terri Witek, Pete Smith, Marita Dachsel and Angela Caporaso (among others, most likely). And 2024 subscriptions are now available!

October 13, 2023

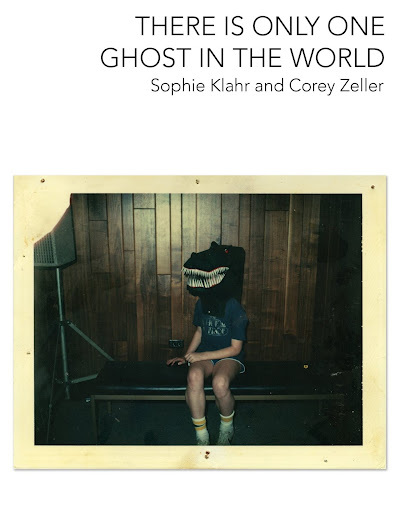

Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller, There Is Only One Ghost in the World

My mother was reading abook to me in bed when we saw the reflection of flames on my bedroom wall. Acrossthe street, the neighbor’s house was burning. I remember being outside in mynightgown, barefoot, my feet in the runoff the firetruck bled, ambulance-menrustling onto the stretcher something dark. My parents told me later that ourneighbor, the old woman I called Aunt Heppy, had died, and that her old whitedog had died too, but that her German shepherd puppy had survived. It jumpedthrough the big glass window of the living room, breaking the broad pane. At school,everything was uniform. The kids all wore the same outfits and their parents allhad the same medications. You looked out the window most of the time. Youlearned more than anyone should ever know about the sky. You drew a line with astick in the new snow and dared a friend on the other side to cross it. Onceyou cross it, you can never come back, you told him. He was reduced totears, and you got in trouble, even though his explanation made no sense toanyone. They told me I could never come back, he wailed. Only when I wasgrown-up did I realize that it couldn’t be true, that the puppy could not havebroken the glass. I asked my mother, and she admitted it wasn’t true.

Selectedas the winner of the 2022 Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Contest is Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller’s collaborative

There Is Only One Ghost in the World

(Tuscaloosa AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2023), an accumulation of untitledself-contained first-person stories, none of which are each longer than asingle page, that appear to connect or thread only loosely through structureand tone. I’m startled by how each narrative of seemingly random turns allowsfor a different kind of structure, one that composes fiction almost akin to thearc of a poem, moving from moment to moment, and allowing the collision andaccumulation of these varying threads to provide connection only through theact of reading, and the reader themselves. There is nothing straightforward here,and there are some stunning and powerful moments throughout these pieces, woveninto the larger fabric of this incredibly interconnected book-length quilt,offering wisdoms, comforts and important truths. “A girl you loved once lovedyou more and got angry when you didn’t love her like that,” the two of themwrite, “like, back enough. She is angry enough to say that you aren’t queerenough. This is always the problem—others drawing little boxes around yourdesire, waiting at a long panel like a spelling bee competition, waiting foryou to fumble.” Another piece offers: “Optimism is a chandelier. It swings toone side catching some light. It swings back and catches the dark. Pessimism,on the other hand, is nothing but a weathervane, a lightning rod.” Orelsewhere: “A piece of what elegy can do is hold an absence by naming it, asif, by saying its endlessness, it is, for a moment fixed in time, when so oftenthere seems no end to grief, only its opening. Even a poem on endlessness hasan ending, a hand, for a moment, resting on one’s shoulder.”

Selectedas the winner of the 2022 Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Contest is Sophie Klahr and Corey Zeller’s collaborative

There Is Only One Ghost in the World

(Tuscaloosa AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2023), an accumulation of untitledself-contained first-person stories, none of which are each longer than asingle page, that appear to connect or thread only loosely through structureand tone. I’m startled by how each narrative of seemingly random turns allowsfor a different kind of structure, one that composes fiction almost akin to thearc of a poem, moving from moment to moment, and allowing the collision andaccumulation of these varying threads to provide connection only through theact of reading, and the reader themselves. There is nothing straightforward here,and there are some stunning and powerful moments throughout these pieces, woveninto the larger fabric of this incredibly interconnected book-length quilt,offering wisdoms, comforts and important truths. “A girl you loved once lovedyou more and got angry when you didn’t love her like that,” the two of themwrite, “like, back enough. She is angry enough to say that you aren’t queerenough. This is always the problem—others drawing little boxes around yourdesire, waiting at a long panel like a spelling bee competition, waiting foryou to fumble.” Another piece offers: “Optimism is a chandelier. It swings toone side catching some light. It swings back and catches the dark. Pessimism,on the other hand, is nothing but a weathervane, a lightning rod.” Orelsewhere: “A piece of what elegy can do is hold an absence by naming it, asif, by saying its endlessness, it is, for a moment fixed in time, when so oftenthere seems no end to grief, only its opening. Even a poem on endlessness hasan ending, a hand, for a moment, resting on one’s shoulder.”Thestories touch on, and even return, like a skipping stone bouncing across water,to subjects including queer desire, loneliness, trauma, politics and culturewars, hope and memory, one thought immediately following another, movingthrough moments and references that fade in and out of view with remarkableclarity. As one piece offers: “Being pansexual doesn’t mean that you areattracted to more people than anyone straight or gay might be. It just meansthat desire is a kaleidoscope, and you are all of the pieces inside.” I’mcurious at how the back-and-forth between these two authors worked, exactly, ifeach composed individual pieces that bled together, or if each piece itself hasthe hands of both authors within; in a certain way, none of it matters. There arecertain directions that make me wonder if a handful of pieces were written byone author over the other, but on the whole, the tone is incredibly consistent,providing a wonderfully coherent whole between these two writers, during thepandemic era. As they write as their “Note on Creation” at the end of thecollection: “This book was written collaboratively over the course of eightmonths during the Coronavirus pandemic (November 2020-August 2021), in a singleshared Word document, from six states away.” I’m now curious to see further oftheir individual works: on her part, Los Angeles poet and editor Sophie Klahris the author of the poetry collections Meet Me Here at Dawn (YesYes Books,2016) and Two Open Doors in a Field (Backwaters press, 2023), and CoreyZeller is the author of MAN VS. SKY (YesYes Books, 2013) and YOU AND OTHER PIECES (Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2015), none of which I’ve seen (I’mclearly behind on my reading). Oh, this is a book I wished I’d written; and I amterribly jealous.

Fish have something inthem called a lateral line—this is what helps their schools stay together. Whenthey want to stay still, they face upward. Into the current. The day closesitself like an orphan’s locket, the lip of a candle resembling lace almosttouching the inside of a thigh. Now, and only now, you fail to find adifference. Some handless beauty. Blinking and squinting at the clearestpossible scene. Truth reversed does not make a lie. A lie reversed does notmake truth. The truth of a person is different than the truth of the poem. Youtry to make a Venn diagram of this, but can’t figure out what to put in thethird circle or in the pill shape of the intersection. A certain type of antscollect the skulls of other ants to decorate its nest. There is a type of sharkthat new theories say may have a lifespan of up to six hundred years. InGreenland, one is caught that scientists estimate as being between two hundredand seventy-two years old and five hundred and twelve years old. There arecertain types of crystals in the eyes of this shark. The oldest type of poetryis poetry with a riddle inside.

October 12, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cathy Stonehouse

Cathy Stonehouse

(she/they) is a poet, writer, teacher andvisual artist in Vancouver, BC. The author of a novel,

The Causes

, a collectionof short fiction,

Something About the Animal

, and two previous collections ofpoetry—

Grace Shiver

and

The Words I Know

. Stonehouse co-edited theground-breaking anthology

Double Lives: Writing and Motherhood

and is a formereditor of

EVENT magazine

. They teach creative writing and interdisciplinaryexpressive arts at Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

Cathy Stonehouse

(she/they) is a poet, writer, teacher andvisual artist in Vancouver, BC. The author of a novel,

The Causes

, a collectionof short fiction,

Something About the Animal

, and two previous collections ofpoetry—

Grace Shiver

and

The Words I Know

. Stonehouse co-edited theground-breaking anthology

Double Lives: Writing and Motherhood

and is a formereditor of

EVENT magazine

. They teach creative writing and interdisciplinaryexpressive arts at Kwantlen Polytechnic University.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book didn't change my life in the ways I naively expected itmight (i.e. entirely positively!). It was amazing, but also emotionallycomplicated. In fact, being published freaked me out so much I went silent for15 years, and I've been trying to reduce this effect with each book since. I'mgetting there. My most recent work, as a whole, is very different from my previouswork, in that I'm moving toward a more comfortably capacious andinterdisciplinary voice. I'm finally getting into my stride. A bit late, buthey ho.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Poetry has always been my first love. Sound, rhythm and musicality areeverything to me, even in prose. As a child I liked to read poems aloud even ifI didn't understand what they meant. Writing poems can feel like how I imaginebeing able to sing really well might feel (an experience I only have in dreams,then wake up). Whenever I write prose I look forward to the stage when I canrelate to the words and sentences as music again, i.e. when editing. I alsostart prose like this, but in the middle it's a heck of a lot of other work.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

It can take a very long time for me to finish a project, although I havenew ideas constantly. Work is often in my brain and/or notebooks for yearsbefore I have the space & time to manifest it, and sometimes revisions comeafter decades. This new book's main spine, the section called Dream House, camevery fast one summer (2018) after returning home from the UK having rapidlyemptied my mother's house. The rest of the book took a lot longer.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I work more and more in a long form--the sequence, the book-lengthwork--even with poetry and short stories. I get a kind of "feeling"of the work as a whole, then figure out the components.