Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 70

November 30, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Wanda John-Kehewin

Wanda John-Kehewin (she,her, hers; photo credit: Tammi Quin) is a Cree writer who uses her work tounderstand and respond to the near destruction of First Nations cultures,languages, and traditions. When she first arrived in Vancouver on a Greyhoundbus, she was a nineteen-year-old carrying her first child, a bag of chips, abottle of pop, thirty dollars, and a bit of hope. After many years oftravelling (well, mostly stumbling) along her healing journey, she shares herpersonal life experiences with others to shed light on the effects of traumaand how to break free from the "monkeys in the brain."

Now apublished poet, fiction author, and film scriptwriter, she writes to stand inher truth and to share that truth openly. She is the author of the Dreamsseries of graphic novels. Hopeless in Hope is her first novel for youngadults.

Wanda isthe mother of five children, two dogs, two cats, three tiger barbs (fish), andgrandmother to one super-cute granddog. She calls Coquitlam home until thesummertime, when she treks to the Alberta prairies to visit family and learnmore about herself and Cree culture, as well as to continuously think and writeabout what it means to be Indigenous in today's times. How do we heal from aplace of forgiveness?

1 - How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

The veryfirst book helped me feel like I was a writer. I did think after one book, itwas easy street from there (Not). Now that I am on my 9th book (twowere grade one and two readers) it feels like I am a writer. I am still not oneasy street but I love what I do!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

It was suchan easy form for me to write about trauma or things that were traumatic becauseto a point I could hide behind details and make inferences to things and notactually say the traumatic thing or event.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

I think mywork or any work for that matter comes out when it needs to come out. Mywriting is sort of a conspiracy between the ancestors and the universe! I thinkI am lead to write what it is I am supposed to write about. Sometimes thewriting comes quickly and other times, not so much. My work comes out in burstswith a lot of help from my editors. Editors are so wonderful. Without them,that is what it would be, bursts of ideas!

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I work onpoems first and collect one-liners and then it takes shape later on. It comesto fruition when there is a container for it. I do not start with a container,it sort of reveals itself afterwards.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are youthe sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do likereadings. I also like to share and I think it is a big part of teaching aboutIndigeneity on a micro level, I believe when we get to know people, and whenpeople get to know me, we can get past stereotypes and stigmas and perhaps evenhave our biases challenged.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I think thebiggest thing I do with my work is stand in my truth which, I believe helpsothers who come from trauma to stand in theirs as well. When we stand in ourtruth and aren’t ashamed of it, we can begin to heal.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture?Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This is abig question and I am sure has many avenues but to me, the role of the writerin larger culture depends on genre. I can only answer thoroughly from a poet'sperspective, YA, and perhaps graphic form but the answer will be different eachtime. I think the role of the writer is to tell a relatable story in whatevergenre it is meant to be in in order to reach the largest audience. It alsodepends on what the author’s intent is with it, my poetry, I would say is tohelp others stand in their truth, and my YA is to help others understand andoffer some answers to those in the process with similar experiences as mycharacter.

On a macrolevel, the role of the writer should be alongside what we as humans need. Somewill be fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, YA, graphic form, plays etc. Iwould say there is not one way to tell a story but the different ways we tellit will attract the different audiences.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

I find itessential, their name is on the line as well. Editing is their livelihood andso they are going to do the best they can as well.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given toyou directly)?

Stand inyour truth, Vera Manuel.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry tofiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Thankfully,I have had some great editors who have helped make that transition smooth andvery informative. I am a better writer because of them.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even haveone? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Lately, Ionly write for two hours\ on Sundays to finish the 3rd part of theGraphic Novel, Dream series. It will look different as things change,for sure. Change is the only thing I can depend on and I have to find ways toadapt.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

My children

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

StrawberryJam

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are thereany other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science orvisual art?

I thinkexperiences, memories, feelings and connection to spiritual self and ancestorsare also places books come from.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simplyyour life outside of your work?

Vera Manuelwas someone who started me on my writing path to actually believing that Icould share my poems and stories without crying and grieving and that one day,it would be possible for me.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write amemoir

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

I would bea philosopher! Or a spiritualist! But still a writer!

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing wasdone as a way to make sense of colonial history within the Indigenouscommunities. I needed to understand it and poetry gave me the ability toprocess and to think critically.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last greatbook I read? Jessica Johns, Bad Cree. The last great film? Bones ofCrow by Marie Clements.

20 - What are you currently working on?

The thirdand last part of my graphic novel series, Visions from Spirit.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

November 29, 2023

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part one : Stuart Ross + Pearl Pirie,

Incase you didn’t catch, we had another small press book fair not long back (theevent is now twenty-nine years old!), at the Tom Brown Arena in Hintonberg! Thenew location went better than expected, so I’m thinking of not returning toJack Purcell as originally planned, but perhaps remaining here. It’s a largerspace, and better parking, for one thing. There were other perks as well. Whatdo you think?

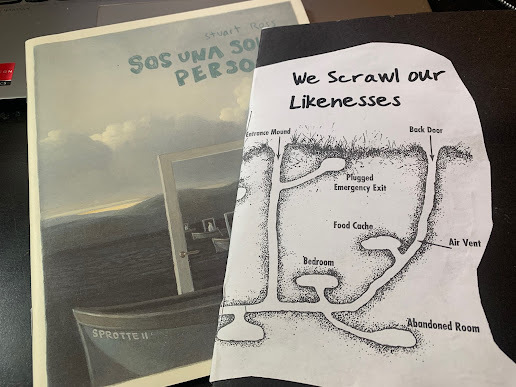

Incase you didn’t catch, we had another small press book fair not long back (theevent is now twenty-nine years old!), at the Tom Brown Arena in Hintonberg! Thenew location went better than expected, so I’m thinking of not returning toJack Purcell as originally planned, but perhaps remaining here. It’s a largerspace, and better parking, for one thing. There were other perks as well. Whatdo you think?Buenos Aires, Argentina/Cobourg: I recently picked up acopy of Stuart Ross’ Sos una sola persona (Buenos Aires: Socios Fundadores,2020), a bilingual ‘selected poems’ chapbook of his, with pieces translated intoSpanish (and presumably selected as well) by Sarah Moses and Tomás Downey. The selectionof poems offer considerations of place, of settlement; poems on fathers andsons; and elements of voice, akin to, say, the work of Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell (although Ross works his narratives quite differently, offeringanxiety, uncertainty and a surreal unsteadiness, instead of simply occupying a variationon scene and narrative character study). Honestly, it would be interesting ifsomeone Spanish speaking from Argentina, otherwise completely unaware of StuartRoss and his work prior to this small collection, to work through a review ofthese poems; I suspect they might catch something that I, a reader and reviewerof Ross’ work since the 1990s, might simply not catch. Maybe? Perhaps theelements of surrealism would find more familiar readers on that end, unconfusedwith approaching poems such as “RAZOVSKY AT PEACE” (the title poem of his 2001 collection with ECW that I reviewed for The Antigonish Review; thereview is long disappeared from the internet) that includes: “Razovsky becomes/ part of the ground. The chip bag become a butterfly, as ordained / by nature;it struggles from its / cocoon, bats its wings, / tugs frantically, / but stillit is lodged / between the rocks. Razovsky / is not surprised.”

Itis a curious selection, and apart from Brooklyn poet and editor Jordan Davis’ongoing work through Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks, I don’t see anyoneelse putting together chapbook-sized selected poem collections. Given he had aselected poems some twenty years back, Hey, Crumbling Balcony! Poems New& Selected (ECW Press, 2003), a book that still appears available onthe ECW Press website, one might think that perhaps a new selection should beput together of Ross’ work. How many trade collections and chapbooks has heproduced since then?

Ottawa ON: The latest from Pearl Pirie is the chapbook We Scrawl our Likenesses (phafours, 2023), a small title of poems built out ofelements of the work of Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall. As she writes in heracknowledgments: “In these poems I wrote not a word, only cobbled. Some capitalizationchanged. Each line is quilted, that is, the form is a cento of his poems andinterviews.” This isn’t the first time Pirie has worked such a form, assemblinga variation on the same through some of my own work through her rob, plunder, gift (Ottawa ON: battleaxe press, 2018). Pirie’spoems over the years has evolved into a poetics of declarations, observationsand examination, first-person meanderings that accumulate into curious collage-movements,most of which ebb and flow across thought and language, and there is much inher work to compare to that of Phil Hall’s own work. And yet, using Hall’slanguage, these poems are unmistakably, delightfully, hers.

a title is not a pitch,it is a commitment

there are too many Wordsworths

shoving the fields

& them running slapping their heads

to make progress happenby making poems be tools

wearing a giant dollar-billcostume

their minds likestumps in raw clearings

& fenced with theirown charred stumps

This is what you havemade carefully—tear it down

but what would that prove

& I can only pretendto help

anti-perfection. I seekwords to embellish my flaws.

the needed musicun-preplanned forms

a chickadee embeds itselfin the fog

but I insisted

November 28, 2023

Donna Stonecipher, The Ruins of Nostalgia

THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 2

We had been to the secretservice museum, to the shredded-documents-being-pieced-back-together museum, tothe museum of the wealthy family’s Biedermeier house from 1830, to the museumof the worker family’s apartment from 1905, to the museum of the country thatno longer exists, to the museum of the history of the post office, to the museumof the history of clocks. We had seen the bracelets made of the beloved’s hair,the Kaiserpanorama, the pneumatic tubes, the hourglasses, the shreds, themicrophones hidden in the toupees, the ticking, the gilded mirrors reflecting ourfaces, the two rooms eight people lived in, the eight rooms two people livedin, the shreds, the trays of frangible butterflies carrying freight, thesilvery clepsydras, the ticking, the simulacra, the shreds, the vitrines, thevelvet ropes, the idealized portraits of the powerful, the ticking, the pink façades,the upward mobility, the shreds, the plunging fortunes, the downward spirals,the ticking, the ticking, the shreds, the shreds. We had been to the museum ofthe ruins of nostalgia.

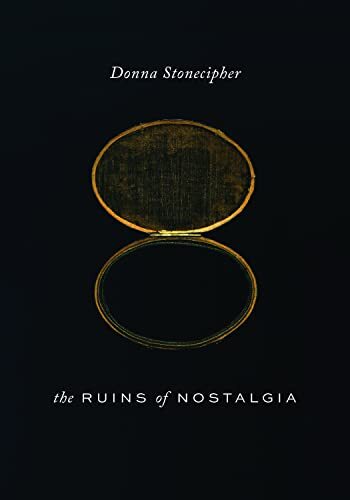

I’mdeeply behind on the work of American-expat Berlin-based poet Donna Stonecipher[although we did hang out that one time in Berlin], having gone through her

Transaction Histories

(University of Iowa Press, 2018) [see my review of such here],but not yet seeing copies of her books such as

The Reservoir

(Universityof Georgia Press, 2002),

Souvenir de Constantinople

(Instance Press,2007),

The Cosmopolitan

(Coffee House Press, 2008),

Model City

(Shearsman, 2015) or

Prose Poetry and the City

(Parlor Press, 2017). At leastI’m able to get my hands on her latest,

The Ruins of Nostalgia

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), an unfolding of sixty-four numberedself-contained prose poem blocks, each sharing a title. As the cover flap offers:“Sparked by the East German concept of Ostalgic (nostalgia for the East)and written while living through unsettling socio-economic change in bothBerlin, Stonecipher’s adopted home, and Seattle, her hometown, the poems mounta multifaceted reconsideration of nostalgia. Invented as a diagnosis by a Swissmedical student in 1688, over time nostalgia came to mean the notoriousbackward glance into golden pasts that never existed.” Stonecipher composes hersequence of prose poems as a weaving of lyric, essay and image, examining thevery act of remembering the past, focusing on periods and geographies in themidst of change, ranging from the intimate to the large scale. “It was beforethe city built traffic circles at every intersection to prevent accidents,” thepiece “THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 21” begins, “like the one she’d heard one Sunday afternoonthat sounded like someone shoving her parents’ stereo to the floor, but she’drun downstairs to find the stereo intact, her brother in front of it as usual,practicing ‘Stairway to Heaven’ on the guitar, headphones on.” Her prose linesextend and connect to further lines and threads held together, end to seemingend. “Of course it was a little odd to be glad of the bombs that had enabledthe holes to remain holes,” she writes, as part of “THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 7,” “tobe grateful for the failed bankrupt state that had enabled the holes to remainholes, so lying on the grass of an accidental playground, one just listened tothe ping-pong ball batted back and forth across the concrete table. And thoughtidly of one’s own surpluses and deficits.”

I’mdeeply behind on the work of American-expat Berlin-based poet Donna Stonecipher[although we did hang out that one time in Berlin], having gone through her

Transaction Histories

(University of Iowa Press, 2018) [see my review of such here],but not yet seeing copies of her books such as

The Reservoir

(Universityof Georgia Press, 2002),

Souvenir de Constantinople

(Instance Press,2007),

The Cosmopolitan

(Coffee House Press, 2008),

Model City

(Shearsman, 2015) or

Prose Poetry and the City

(Parlor Press, 2017). At leastI’m able to get my hands on her latest,

The Ruins of Nostalgia

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), an unfolding of sixty-four numberedself-contained prose poem blocks, each sharing a title. As the cover flap offers:“Sparked by the East German concept of Ostalgic (nostalgia for the East)and written while living through unsettling socio-economic change in bothBerlin, Stonecipher’s adopted home, and Seattle, her hometown, the poems mounta multifaceted reconsideration of nostalgia. Invented as a diagnosis by a Swissmedical student in 1688, over time nostalgia came to mean the notoriousbackward glance into golden pasts that never existed.” Stonecipher composes hersequence of prose poems as a weaving of lyric, essay and image, examining thevery act of remembering the past, focusing on periods and geographies in themidst of change, ranging from the intimate to the large scale. “It was beforethe city built traffic circles at every intersection to prevent accidents,” thepiece “THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 21” begins, “like the one she’d heard one Sunday afternoonthat sounded like someone shoving her parents’ stereo to the floor, but she’drun downstairs to find the stereo intact, her brother in front of it as usual,practicing ‘Stairway to Heaven’ on the guitar, headphones on.” Her prose linesextend and connect to further lines and threads held together, end to seemingend. “Of course it was a little odd to be glad of the bombs that had enabledthe holes to remain holes,” she writes, as part of “THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 7,” “tobe grateful for the failed bankrupt state that had enabled the holes to remainholes, so lying on the grass of an accidental playground, one just listened tothe ping-pong ball batted back and forth across the concrete table. And thoughtidly of one’s own surpluses and deficits.” Thenotion of the repeated title is one I’m fascinated by, something utilized by astring of poets over the recent years, from Peter Burghardt, through his full-lengthdebut (no subject) (Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2022) [see my review of such here] to the late Denver poet Noah Eli Gordon’s Is That the Sound of a PianoComing from Several Houses Down? (New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and Johannes Göransson’s SUMMER (Grafton VT:Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. There is somethingcompelling about working this particular kind of thread, attempting to pushbeyond the obvious across those first few poems under a shared title, into anarray of what else might come. As well, Stonecipher’s line “the ruins of nostalgia”repeats at the end of poems akin to a mantra or chorus, running through thefoundations of the sequence like a kind of tether, stringing her essay-poemstogether in a singular line of thought. It almost reminds of how RichardBrautigan used language as an accumulative jumble into the final phrase of In Watermelon Sugar (1968), a novel that ended with the name of the book itself;or the nostalgia of Midnight in Paris (2011), a recollection that soughta recollection of a recollection, folding in and repeating, endlessly rushingbackwards. As with nostalgia, the phrase is repeated often enough throughoutthat it moves into pure sound and rhythm and away from meaning; to look too farand too deep into an imagined recollection, one glimpsed repeatedly anduncritically, is to lose the present moment. It is, by its very nature, to becomeruin. As “THE RUINS OF NOSTALGIA 11” writes:

We were able to benostalgic both for certain cultural phenomena that had vanished, and for thetime before the cultural phenomena had appeared, as if every world we lived inhid another world behind it, like stage scenery of a city hiding stage sceneryof tiered meadows hiding stage scenery of ancient Illyria. For example it wasn’tanswering machines, or the lack of answering machines, or the sight of tinyanswering-machine tape cassettes that triggered our nostalgia, but therealization that our lives had transcended the brief life of the answeringmachine, had preceded and succeeded it, encompassed it, swallowed it whole,which meant we had to understand ourselves not as contained entities, but asplanes intersecting with other planes, planes of time, technology, culture, desire.One plane had waited by the phone for our best friend’s phone call beforeanswering machines, and then one plane had recorded outgoing messages on theanswering machine over and over, trying and trying to sound blithe. How many tinytape cassettes still stored pieces of our voices like pale-blue fragments ofPlexiglas shattered into attics and basements across any number of states? We stillowned a tape cassette with the voice of our first beloved on it, or a versionof it, and remembered the version of the girl who kept rewinding his messageover and over, under an analogue wedge of black sky and endlessly delayedstars. She was listening and listening for answers the answering machine couldnot provide. When we felt our material planes sliding to intersect withimmaterial planes, or vice versa, we bowed our heads and submitted to thepile-up of the ruins of nostalgia.

November 27, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sean Dixon

Sean Dixon grew up in afamily of 12, including his 8 siblings, parents and a grandmother, throughseveral Ontario towns, predisposing him to tell stories about groups of peoplethrown together in common cause. His debut novel, The Girls Who SawEverything, was named one of Quill & Quire’s best of theyear. His previous books include The Many Revenges of Kip Flynn, TheFeathered Cloak, and the plays Orphan Song and the Governor General’s Awardnominated A God In Need of Help. A recent children’s picturebook, The Family Tree, was inspired by his experience of creating afamily through adoption with his wife, the documentarian Kat Cizek.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

I had a big bereavement whenI was a child. I lost my 15-year-old brother when I was ten to a swift,horrible factory accident. It was a defining moment for me and it governed mylife choices well into adulthood. Some months after I published The Girls WhoSaw Everything — I don’t know how else to describe this — I felt all that griefleave my body. I knew the Epic of Gilgamesh held this kind of power all on itsown, and I do believe that’s why I became obsessed with it, but I didn't knowthat my embodying and retelling of it would have such a life-altering effect onme.

It wasn’t an entirelypositive feeling either: I didn't know who I was anymore. I had always lovedthe unchanging, wise, sad child that had grown up inside of me. I had alwaysfelt I had known death and was not afraid of it. Now suddenly, unexpectedly, Iwas like every other life-loving fool. I was no longer Max von Sydow in TheSeventh Seal, but rather just the strolling player with his family and hiswagon. Faced with grieving people I was just as tongue tied, bewildered andstammery as any normal, well-adjusted person. And, worst of all, I was afraidof dying too. Just like everyone else.

It was awful. I used to havea kind of wisdom. Now it’s gone. Though I will add that the up side ofoffloading all that wisdom was I was finally able to contemplate raising achild of my own. What happens when you don’t think you’re about to leave all thetime.

So I guess the answer is myfirst book changed my life because it made me less afraid to be a parent.

My daughter asked me to readmy latest book to her. So I did. Then she asked me to read my last one — TheMany Revenges of Kip Flynn. My impression, reading them back to back, isthat my experience reading thousands of words to my daughter out loud over thelast several years has paid off, it’s made me a better writer than I used tobe. I don’t add unnecessary details anymore. I seem to have a betterunderstanding of what to put in and what to leave out.

2 - How did you come towriting plays first, as opposed to, say, poetry, fiction or non-fiction?

I was trained as an actor atthe National Theatre School. In our second year, my class made a project with aCanadian actor from Denmark’s Odin Teatret named Richard Fowler forwhich we were asked to create short physical scenes using text and props, etc,where the meaning could be entirely personal and did not have to becommunicated to the audience. This was a liberating exercise for us, aparticularly shy bunch of acting students.

Then I observed, with greatfascination, as Richard took our scenes, ordered them, combined some of them,changed a few details, snipped a few bits, and created something resembling anarrative with them. He called it “a process in search of a meaning.” It gaveme insight into how you could generate a practice of creating raw materialwithout necessarily knowing how you were going to use it. Our physical bodiesprovided the raw material, but I realized that material could have beenanything, could have come from anywhere.

When my class graduated, weformed a company, Primus Theatre, and made a collective creation called Dog Daythat we had begun in third year, still working with Richard Fowler. While inschool, I had written some material for Dog Day in a ‘storyteller’ voice that Iwanted to expand beyond the parameters of that creation. While waiting for theDog Day rehearsals to get underway, I wrote a monologue play called FallingBack Home that ended up being a sort of tragedy about a spinner of tales whosuffers from the delusion that every story he dreams up is true, no matter howoutlandish. By the time the Primus company got underway, I was feeling the pullof responsibility to the script of Falling Back Home so much that the newcompany felt like a distraction from my true priorities. So I quit the company.It was an interesting decision: I was leaving behind my best friends, greatdinners, the opportunity to travel to Denmark and Italy and meet hundreds ofpassionate and interesting people because I wanted to have more time to sit inmy room and write.

So that’s how I started, butthe experience gave me the tools to create a larger work of any kind: playswere just my entry point. My father has always been a big novel-reader, so itwas the great desire for me to do that but I was so, so afraid that I neverwould. When I finally started, adapting my oversized stage play The Girls WhoSaw Everything, I spent eight months writing constantly, always fearing that Iwould quit at any moment. But I had the grid of the story-as-a-play to keep megoing.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I get an idea, an image, andI tell myself it’s never going to happen. (Currently I’m not going to write amodern version of Apuleius’s Golden Ass and I’mdefinitely not going to write a stage variation of Achilles sulking in histent, standing in for all the grievances of men.)

I think my first drafts havea real shape. But they’re a mess on the sentence level. I dispute the idea thatyou have to build a work via one perfect sentence at a time — Donna Tarttwriting The Little Friend. I’m more interested — to use an artist analogy — insketching out the proportions of the full figure and then going back andfilling in the details. If you don’t do that, I think it becomes very hard tothrow things away, which is a necessary part of writing a larger work, and itcan be very hard to tell a full story that feels proportionally satisfying tothe reader. You’re reading and you feel you’ve passed the beginning and nowyou’re moving into the middle, and now you’ve hit the peak and now you’vepassed the peak. To use the artist analogy again: you haven’t committed to anose too large and a forehead too small.

But then, once that is done,I think I really need some help from an editor saying now look this sentencehere: it’s a mess. And this one, and this one.

4 - Where does a play orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I’ve always thought of aplay as something I can write to inspire and challenge a group of people —something that would be fun for a little community of people to do. Myimpression is that most playwrights don’t start from this impulse. With anovel, the impulse is more private. I want to explore this world by myself.

With The Girls Who SawEverything, I was initially challenged to write a play for the women of arepertory theatre company in Montreal that was concentrating on the classicsand so there weren’t a lot of parts for them. All the great parts were for themen. So I set out to create a meaty part for every single one of them.

The younger founder of thecompany loved the play but the older one decided not to pursue it. I’m notsure, but my theory is that he misconstrued the heightened aspect of mycharacters for mockery. The play was doomed by that point, too large forCanadian theatres, although it did get a second life as a theatre schoolexercise.

Then, when I rewrote it as anovel, I dove in to what the Gilgamesh epic meant to me, all the personal stuffthat came into my mind while I was working on the play but had no performativeoutlet. The last third of the novel — when the characters find themselvesfollowing the old Nindawayma ferry ship across the world to a scrapyard in thePersian Gulf — is a complete departure from the play, and I suppose it rendersthe play out of date. It provides a much more satisfying ending, at least. Itmade me realize that it can take a long time to find a really good ending for astory.

For my most recent novel, Isuppose I set out to explore what had thwarted my teenage impulse to makevisual art. I wanted to feel again the joy that I had felt when I used to dothat kind of work.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I love them. I think I’mgood at them, but I also think that audiences who go to public readings are sosuper attentive (compared to theatre audiences, say) that they don’t ascribe alot of value to whether the reader is a good performer or not. The entertainmentvalue is just a side benefit. So my talent for it doesn't really stand out, itseems to me, except in the eyes of people who really care for that sort ofthing. I remember once I tried to behave like a regular, mature writer at apublic reading. An old friend admonished me afterwards for trying to behavelike everyone else. Ever since then, I’ve stopped worrying about it.

My favourite public readingexperience, though, remains a children’s reading at the Ottawa festival, in apacked space. A library, I think? I was promoting The Feathered Cloak, I think.I can’t recall who introduced me but they mentioned that I played the banjo. Soall the kids were asking about the banjo. But I had not brought my banjo. Ithought that would let me off the hook, but then, during the question period,someone asked me if I would sing a song without the banjo. I sang an oldScottish a Capella ballad called The Blackbird Song and then got mobbed. It wasunbelievable. I felt like Taylor Swift.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I think I’ve always held onto that idea from my youth of the process in search of a meaning. what thatidea means to me now, is: I sense that, as a very dull person who only findsdepth — gratefully, humbly — when I’m in conversation with a searching,thoughtful, charming, vibrant, observant person that is not me, I have nochoice but to try to conjure such voices out of the world that surrounds mewhen I write. I try to be attentive to serendipities that provide the rawmaterial and can then be sketched lightly into my work, and later hammeredhome. Perhaps that is gobbledeegook. I look for the questions. I don’t thinkthey’re inside me. It has to be a conversation with the world.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I do think the writer has aresponsibility to cultivate alternative points of view. My alt pov has alwaysbeen a celebration of the imagination, so I can see how that is not asimportant as explorations of culture and class.

8 - Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Not difficult. Certainlyessential. But also: celebratory. I loved working with Liz Johnston on TheAbduction of Seven Forgers. I recall a time when I was trying to conveysomething a little otherworldly, wherein my storyteller was catching a magicianin the middle of a mind-boggling sleight of hand. Liz kept writing back thatshe didn't see it, she didn't get it. I think I rewrote that passage four orfive times before I got it right. And I trusted her judgement 100%.

I also like to write aboutgroups of people. My bio addresses that. It can be tricky to keep the reader’scomprehension when you have several names flying around. Liz was instrumentalin helping me clarify and distinguish the introduction and follow-through ofall those voices.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I love the line from TheMisanthrope (I think) that got retooled in a French Moliere biopic to bemore pointed advice to the writer: “Time has nothing to do with the matter.”

And, along with it: do nothurry, do not wait.

How I interpret thesefragments: you might come up with the essence of your work, the rosetta stone,in five minutes — but it’s a burning a nub that will warm your hands through ahundred thousand exploratory words. An image can drop so deep that whole chapterswill pour out in joyful plumbing of it. Other times, you might spend days anddays just trying to catch something that’s just around the corner. Time hasnothing to do with the matter.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (playwriting to fiction)? What do you see as theappeal?

To summarize: I seeplaywriting as more of a social impulse and fiction as more of a privateimpulse. But Daniel Brooks once said that theatre is a young person’s game, andI’m finding this to be more and more the case. I know fewer and fewer peoplewho are making theatre, which means eventually, inevitably, there will be noone left who wants to play with me. So I suspect, if I want to keep writing ina way that feels meaningful, it will have to be from the more private impulse.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Every time I fall in lovewith a routine, I always mourn it when it’s over and it takes awhile before Irealize that I’ve just started a new routine. But I don’t write at all when I’mworried about the basic welfare of my loved ones. And that catatonia cansometimes go on for months, during which time I starting thinking I need tobecome a gardener, or a tree-pruner, or a teacher, or a plumber.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Ovid. The Golden Legend. PuSongling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. A lot of obscureclassics like the first poems in English or the Carmina Burana. A series ofpoetry and photo collections that were published in the 60s and 70s that myeducator father acquired, called Voices, edited by Geoffrey Summerfield,printed on durable paper. One day I will return to Gilgamesh. Zombie. Troy.Superstition. The first Rickie Lee Jones album never gets old. Get Out of My House from The Dreaming. Running Up That Hill. I aspire to write like thoseKate Bush songs, which are rigorous in adhering to their own interior logic.Self-contained. AWOO by the Hidden Cameras. That first album by Joanna Newsom,which I have not heard in awhile because she doesn't stream.

Florence and the Machine.Lhasa. The Waters of March. Halo. Walking in Memphis. Tracy Chapman, HAIM.

13 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

Old pee in the panel-board,sadly. And pine needles.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes. The Abduction ofSeven Forgers was, for me, a joyful exercise in celebrating the influencesof visual art.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Is it okay if I link to this essay I wrote?

16 - What would you like todo that you haven't yet done?

Honestly? I’d like to fronta band as a vocalist. No instrument hanging off me. I want to dress up,ostentatiously, Prince-like, and dance and sing. If I woke up tomorrow in thebody of a 20 year old, that is what I would do, no question.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’m often haunted by thefact that I looked into the architecture program at the university of Waterloowhile I was a first year theatre student there, and realized that my courselist from Grade 13 read like I had planned to enrol. But I was dissuaded by theseven year long program. Well and a theatre colleague of mine had suffered anervous breakdown while attending that program. That scared me away too. It’sone of the reasons I set out to explore what it means to have a visualimagination as a writer with The Abduction of Seven Forgers.

When I was a kid I lovedFarley Mowat and wanted to be a marine biologist. I’m recalling that becauseI’m currently reading some of his books to my daughter. I was dissuaded frommarine biology when I heard you spend most of the time in a laboratory, not inthe field. But I’ve come to realize that this is true about everything. As awriter, I spend most of my time in the laboratory too.

But if I were just coming ofage right now, though, I suspect I’d want to go fight forest fires. Maybe I’d convincemy backup band to fight forest fires with me, while we’re not doing gigs.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

Being a middle child in avery loud and opinionated family that drowned me out. The thought that‘brainstorming’ inevitably meant going with someone else’s idea. The fact thatmy father has always been a voracious reader and always had a book at hand. Thefact the my elder brother—five years senior to me, who was my mentor in allthings—died when I was ten. I was trying to write a story that morning, beforeI learned that he had died. An SF story called ‘The Circle’ about atime-traveller who loops back to — well, I don’t even know because I neverfinished it.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I loved Malicroix, byHenri Bosco. I loved The Corner That Held Them and Lolly Willowesby Sylvia Townsend Warner. I loved Tarka the Otter. I’d like to find anotheranimal novel that consumes me as much as that one did.

I want to read that Canadianbook about the forest fire fires. Western writer, yes?

I’m trying to read PipAdams’ The New Animals. I am bridling against its rigorous realismdespite admiring it greatly. What is wrong with me?

I read two blockbustersrecently: Cloud Cuckoo Land and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow.I admired them but did not love them.

I loved the film about thehawk-healers in India — All That Breathes. I am a sucker for the Guardiansof the Galaxy movies — all of them, except maybe the one about thestarlord’s dad.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I recently asked a localToronto theatre to reconsider a three-hander from a few years ago that theyrejected. The leadership there has changed so I thought I’d give it anothershot. They have offered a reading in early Feb. But I’ve had a look at the scriptand it truly is a mess. So I’m currently trying to use the limitation of thetheme and the actors I requested to write something wholly new.

(As of today I’m failing,though, because a 4th character has suddenlyrevealed herself, foiling all my plans.)

November 26, 2023

two recent reviews of World's End, (ARP Books, 2023)

Reviews! I'm constantly complaining that my work doesn't see critical response, but my latest, World's End, (ARP Books, 2023), has already two! Thanks much to both Wanda Praamsma and Billy Mills! And did you see the one-question interview Hollay Ghadery did with me recently on the book as well, over at River Street Writing? Obviously, copies of the new book are available via those fine folk at ARP Books in Winnipeg, but I have a box or two here, if anyone is so inclined. A similar deal to some of my most recent titles: send $18 (via email or paypal to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com) ; obviously adding $5 for postage for Canadian orders; for orders to the United States, add $11 (for anything beyond that, send me an email and we can figure out postage); for current above/ground press subscribers, I’m basically already mailing you envelopes regularly, so I would only charge Canadians $3 for postage, and Americans $6 (that make sense?)

Reviews! I'm constantly complaining that my work doesn't see critical response, but my latest, World's End, (ARP Books, 2023), has already two! Thanks much to both Wanda Praamsma and Billy Mills! And did you see the one-question interview Hollay Ghadery did with me recently on the book as well, over at River Street Writing? Obviously, copies of the new book are available via those fine folk at ARP Books in Winnipeg, but I have a box or two here, if anyone is so inclined. A similar deal to some of my most recent titles: send $18 (via email or paypal to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com) ; obviously adding $5 for postage for Canadian orders; for orders to the United States, add $11 (for anything beyond that, send me an email and we can figure out postage); for current above/ground press subscribers, I’m basically already mailing you envelopes regularly, so I would only charge Canadians $3 for postage, and Americans $6 (that make sense?)Here's the first review of the book, kindly written by Kingston poet Wanda Praamsma as part of a group review (alongside Sandra Ridley's latest, etc) via the Toronto Star! See the original review here .

Here's UK poet Billy Mills, who posted this on his blog, as part of a group review ( see the original post here ):

World’s End

by rob mclennan

ARP Books, 64 pages, $18

These poems take on the quality of measured breath — inhale inhale pause, exhale. Inhale, and exhale. In so doing, they slow us down, a necessary and welcome step for all, but particularly needed while moving through the births of children and their early years, as mclennan is/was. “A circle of latitude, this/rushing force/of birth; of hours. … Days fold, moments. Into/collapse, and/still.,” he writes in “The small return.” mclennan applies beginner’s mind — the ability to address everything anew — to every poem and fragment; he appears a Zen master through his meditative sequencing, though not unruffle-able to the trials. “Oh, you are stupid, death./You’re drunk; go home.” Intertwined are mclennan’s welcome lessons on process and form (“Attempt to see if sentences can breathe, take root, grow limbs.”) and the abundance of clarity gleaned from small children: “I later gift the toddler a small/plastic robot. She names it: robot.” No need to overcomplicate. These poems send that message: Simplify, breathe, look around.

The Worlds End of rob mclennan’s title is, we are told in an epigraph, is a ‘pub on the outskirts of a town, especially if on or beyond the protective city wall’; a space that is both convivial and liminal and a tone-setter for the book.

As a poet, editor, publisher and blogger, mclennan is a key figure in a world of poets, and this community is reflected in the fact that most of the poems that make up this book have individual epigraphs from writers, the regulars in the World’s End. A sense of poetry as being intrinsic to the world weaves through the book right from the opening section, ‘A Glossary of Musical Terms’:

The Key of S

Hymn, antiphonal. Response, response. A trace of fruit-flies, wind. And from this lyric, amplified. This earth. Project, bond. So we might see. Easy. Poem, poem, tumble. Sea, to see. Divergent, sky. Deer, a drop of wax. Design, a slip-track.

This melding of the natural and domestic worlds (hinted at by the slip-track) with the world of poetry and language is characteristic of mclennan’s work here, with frequent pivots on words that can be read as noun or verb (project). The carefully disrupted syntax calls out the sense of observing from the margins. This can lend a sense of Zen-like simple complexity, a tendency towards silence:

Present, present, present. Nothing in particular.

In the poems in verse, this disruption is often counterpointed by deft assonances:

A gesture: colour match.

Describe, describe. Sarcophagi. Small bite marks

perforate the humerus.

[from ‘Cervantes’ Bones’]

The second aspect of convivial community is family and parenting; the book overflows with babies and toddlers:

Toddler’s outstretched arms,

convinced herself bigger

than she still is, asks: Let me

hold her. Two ducks,

three. The western shoal,

swift curl of seagull, her

newborn deep

and impenetrable.

The contours

of a shapeless day.

Their mother, relieved

she finally out.

[from ‘Two ghazals, for newborn’]

As the book progresses, these themes become more closely interwoven, a process that comes to a head in the penultimate section, ‘mmm’ (the final one is just two pages long, so effectively at the end of the book):

We. Are turning a boundary.

Shush. Shush. Be quiet. Shush. Restrain. Restraint. Abate. Or don’t. Could never. Can’t. I couldn’t. Please. I beg you. Silence, or.

Begat, begat. This is a copy of a document held by the Office of the Registrar General. Begat, begat. Ceaselessly exposed, and hollow. Cyclical, ends. This grown head strikes a ceiling.

Until a separation, there can be no relation. Is this true?

Parthenogenesis. Maternal instinct, strikes. If you the only one. Trade for passage, ours. Delighted. Like it was the day before the day before. Slips through the fingers.

Former mother. Birth. My wrong grammar implicates.

It’s a quietly powerful conclusion to a book that benefits from, and fully merits, careful rereading. At the start of this review, I listed some of mclennan’s many roles in the world of poetry. Let there be no doubt, the primary one is poet.

November 25, 2023

Elizabeth Robinson, Thirst & Surfeit

Mary Reade

While I was captive,

I saw that horizon rhymeswith reason.

And like so, the shape ofthe roof

beckons the hull of aboat.

It’s the sun who decides,in the end,

whether the sea is aplateau or a well and how

such will clang on the atmosphere.

I was captive until I felloff the edge where the great heat

made me captain

of its lull and itswhitecap.

I am mistress, now, of similarities.

My reason is to take andtake now

as the horizon takes fromme

or toward:

the bowed edge of avessel never

secure or heal. The untowardadvance

of light arrests

this surface as given.

Zig-zagging freedom toillumine

what I’ve wrested.

Reason rejects the curve.

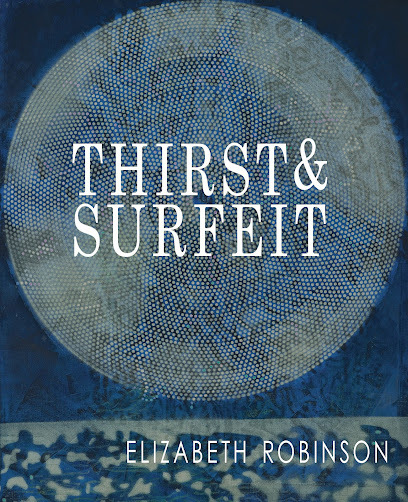

Thelatest from American poet and editor Elizabeth Robinson is the collection

Thirst& Surfeit

(High Point NC: Threadsuns, 2023), a collection that followsa sequence of historical threads, offering themes-as-section titles, seven inall: “The Bog Traverse 1200-600 B.C.E.,” “Hovenweep 1200-1300 C.E.,”“Anne Hutchinson 1591-1643,” “Two Pirates 1690-1782,” “FerdinandGregorovius 1821-1891,” “The Canudos Rebellion, Brazil 1893-1897”and “2023,” a section that holds but the single poem “Legion.” There’san incredible precision to these pieces, an extended stretch of poems on explorationand response across the veil of what might appear to be a scattered list ofhistorical moments and eras. What holds these different time-periods together? “Whatwe’ve shared in common / has made us sink.” she writes, to open the poem “Disappearance,”set as part of the penultimate section. “The earth floor, / swept clean so manytimes / clings to speech. Ubiquitous // sunlight / shows us these particles //as we dwindle beneath them.” Again, what ties these periods together? “History,”as the cover flap of the collection offers, “like ‘light untied and undone,’disperses itself across time and memory. The poems in Thirst & Surfeitreach into these fragments to interpret and sing interactions of human andenvironment, spirit and subsistence.” One might suggest that the connectingtissue between time-periods and their resulting lyrics are simply Robinson’s approachand attentions, striking lyrics on how so much remains unchanged between suchtemporal lengths, such as the weight of a moment, or how uncertainty andaccountability are as much explored as the details of each particular era, asthe opening poem of the second section reads:

Thelatest from American poet and editor Elizabeth Robinson is the collection

Thirst& Surfeit

(High Point NC: Threadsuns, 2023), a collection that followsa sequence of historical threads, offering themes-as-section titles, seven inall: “The Bog Traverse 1200-600 B.C.E.,” “Hovenweep 1200-1300 C.E.,”“Anne Hutchinson 1591-1643,” “Two Pirates 1690-1782,” “FerdinandGregorovius 1821-1891,” “The Canudos Rebellion, Brazil 1893-1897”and “2023,” a section that holds but the single poem “Legion.” There’san incredible precision to these pieces, an extended stretch of poems on explorationand response across the veil of what might appear to be a scattered list ofhistorical moments and eras. What holds these different time-periods together? “Whatwe’ve shared in common / has made us sink.” she writes, to open the poem “Disappearance,”set as part of the penultimate section. “The earth floor, / swept clean so manytimes / clings to speech. Ubiquitous // sunlight / shows us these particles //as we dwindle beneath them.” Again, what ties these periods together? “History,”as the cover flap of the collection offers, “like ‘light untied and undone,’disperses itself across time and memory. The poems in Thirst & Surfeitreach into these fragments to interpret and sing interactions of human andenvironment, spirit and subsistence.” One might suggest that the connectingtissue between time-periods and their resulting lyrics are simply Robinson’s approachand attentions, striking lyrics on how so much remains unchanged between suchtemporal lengths, such as the weight of a moment, or how uncertainty andaccountability are as much explored as the details of each particular era, asthe opening poem of the second section reads:You are not now what youwere meant to be. And this is why mirages are without irony.

So hurry: the precipatefalls hard onto forgetful dirt. The external, like rain, jars you.

There are stretches of miles,of the unexpected; they menace and recant. You prefer that the haste drop youoff like a passenger, into tedium. You are in brambles that annoy but do not scratch.

A cartoonish body waitsoutside yours, whistling and smirking.

The precipitous

falls sodden-to-itself,to shoulders like yours, piggyback.

Hard. Finally, hurtful:this patience.

The trees named forJoshua pick up their arms, plainly out of obedience.

Thereis an interesting structural shift in this collection, beyond what she’s workedin some of her more recent collections, composing a handful of collections viashort lyric response poems, each titled on the variation of “On _____,” fromher Excursive (New York NY: Roof Books, 2023) [see my review of such here] and On Ghosts (Solid Objects, 2013) [see my review of such here]. Thepoems of Thirst & Surfeit offer a blend of structures, from thefragmented long-poem effect of the second section, the self-containedcompactness of the prose poems that make up the book’s opening section, to thedual pirate poems that deliberately work to play off each other. The effect iscurious, akin to an anthology of sorts, as though the form through which sheresponds is as important a shift as her temporal zones and subject matter. “Wemeasure vastness by the limit of our mortal life.” She writes, to open the poem“Salvation,” set as part of the “Anne Hutchinson” section. “I would have youlook, as example, at the face of the clock. It is a face, // even as it cherishesits own absent mouth and closed eyes. Its example we // should emulate.” It isalmost as though she is attempting to capture something larger, and ongoing,with each collection that preceded this one all part of what went into this singularand multitudinous work, a heft of lyric across eighty pages.

November 24, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with John P. Portelli

JohnP. Portelli,originally from Malta, is a professor emeritus in the Department of SocialJustice Education at the University of Toronto. He has taught in Canadianuniversities since 1982. Besides 11 academic books, he has published tencollections of poetry (four in Maltese and English, one in English and French,three in Maltese, one in English (Here Was, available from Amazon) andone in Greek, The Loves of yesterday), two collections of short stories(one translated into English and published as Everyday Encounters), anda novel, Everyone but Faiza (Burlington, ON: Word and Deed, 2021). Hisliterary work has been translated into Italian, Romanian, Greek, Farsi, Arabic,Korean, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Polish. His latest collection, HereWas has been translated and published in Romanian by Rocart Publishers inJune 2023. Five of his books have been short-listed for the Malta Book CouncilAnnual Literary Award. He now lives between Toronto and Malta, and beyond! See,www.johnpportelli.com

1- How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, a poetry collection (2001), introduced meto a different audience than what I had been used to since by then I hadpublished 7 academic books. It gave me a sense of freedom to express myemotions and thoughts without therestrictions of the academia. My most recent work, Here Was (poetry, 2023 published by Word and Deed Publishers inCanada, and Horizons in Malta), while still very personal, is deeper and moremature, and also more emotionally adventurous.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry at the age of 16. Most probablybecause I lack prolonged attention, and given that poetry allows for strongfeelings, I swayed toward poetry.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

During the 40 years that I worked as a professor, givenmy academic focus, writing poetry and fiction did not come easy as it requiresconcentration, and I did not have that leisure. In the last 8 years or so,writing has become easier (but not easy) since I am able to dedicate time everyday to writing non academic stuff (which now I find very boring). I have learntthat good writing usually requires lots of edits. I have been revising a240-page novel for two years!

4- Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually writing begins with an existential experience ofsome sort, even a very mundane or at face value insignificant occurrence. I neverreally know where the first line will lead to! With regard to poetry, I havewritten mostly shorter pieces – although recently I composed a longer piece(about 40 pages) consisting of smaller pieces written in sequence (almostdialoguing with each other). With regard to prose fiction, I have written apublished collection of flash fiction (EveryDay Encounters), and a collection of full length short stories, and a novel(Everyone but Faiza). Writing thenovel was a completely different experience than writing poetry or shortstories. I had it all planned before I started writing. Of course, after thefirst draft was completed, I had lots and lots of revisions and changes.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

In my view, art is primarily a social event. There is noart without an audience that cares and engages. Hence, for me, public readingsfollowed by genuine conversations are essential. I enjoy reading and also, ofcourse, hearing others read.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Writing is always a social/political activity, that isone that involves some sort of power relations (good and bad). It is neverdisembodied! Yet, I do not belief that good literature should be written topass along a particular, specific message or moral. Literature primarily ismeant to give pleasure both to authors and readers by creating a dialecticbetween text and textuality. Having said that, in my writing, as I criticallyreflect on it, certain themes emerge: migration and exile; belonging and lackof belonging, home/not home; the sea; existential encounters; anger towardinjustices; death and memory. Writing (poetry and fiction) can be a form ofsocial activism and also genuine research.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

An astute/delicate observer and sympathetic critic oflife through an expression of genuine feelings-thoughts which may give rise tousually unnoticed insights about the ordinary.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Not difficult as I was lucky to always find a suitableeditor who was not afraid to be critical of my work. For me, it is essential tohave an experienced and courageous editor.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

It is exactly in those moments when you think you arewasting time that, in fact, you are gaining it – an advice I encountered andcherished since I was an undergraduate when I read the Confessions ofJ.J. Rousseau.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short storiesto the novel to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Although I have moved from one genre to another, it isnot easy to move from one to the other. Poetry takes a lot of very concentrated, relatively short spans of time– but it can be very exhausting. Even when I write prose, I get distracted withpoetry. And I suffer from a short spanof attention. In fact, I am surprised that I have written two novels.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Until I retired from full-time work in academia, I had tostruggle to find time to write between meetings, between classes, in boringmeetings etc. Now every morning, after praising the supreme being for giving melife, I meditate for just 5 minutes, drink lots of water and then 3 strongespressos, and then I write for an hour or two.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Re-reading of authors I love, meditate, and observepeople in coffee shops. When I am in Malta I visit the sea and converse withit!

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of the Mediterranean Sea! And the orangeblossoms.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Definitely existential encounters, aspects of nature, andmusic.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Tahar Ben Jelloun, Laila Lalami, Suheir Hammad, Albert Camus, Mahmoud Darwish, Maria Grech Ganado, Elena Stefoi, George Seferis. Italo Calvino, Adonis.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit Japan and Latin America.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Pizza maker and owner of a pizza place.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Dealing with the angst of life! I found freedom inwriting; it allowed me to dialogue critically with myself.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Present Tense ofthe World (poems) by Amina Said. Film: Babylon Berlin.

20- What are you currently working on?

Two collections of poetry, a collection of short storieson the theme of sexuality, and the novel that I mentioned earlier.

November 23, 2023

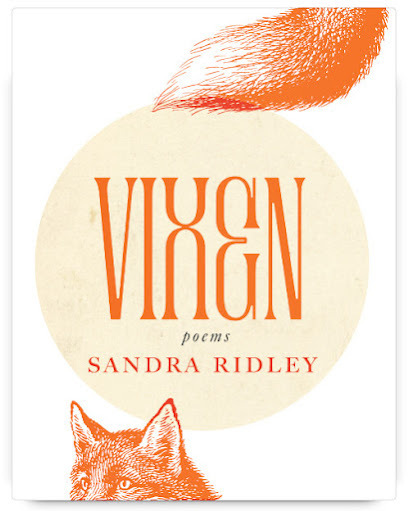

Sandra Ridley, Vixen

Clover andlaurel and thistle

velvet andsumac

muskroot andsundew and baneberry

crocus andcherrychoke

eyebright andbindweed

moonseed andcoltsfoot

panic grassand bloodroot and hyssop

loosestrife andboneset

goldenseal andsedge and lady fern

devil’s bitand daisy and aster

violet and ivy—everyleaf will wither.

You willsuffer the same.

(“THICKET”)

Forher fifth full-length poetry title,

Vixen

(Toronto ON: Book*Hug Press,2023), Ottawa poet and editor Sandra Ridley blends medieval language around women,foxes and the fox hunt alongside ecological collapse, intimate partner violenceand stalking into a book-length lyric that swirls around and across first-personfable, chance encounter and an ever-present brutality. Following hercollections

Fallout

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2009) [see my review of such here],

Post-Apothecary

(Toronto ON: Pedlar Press, 2011) [see my review of such here],

The Counting House

(BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here] and the Griffin Prize-shortlisted

Silvija

(BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here], the language of Vixenis visceral, lyric and loaded with compassion and violence, offering both alanguid beauty and an underlying urgency. “If he has a love for such,” shewrites, as part of the second poem-section, “or if loathing did not preventhim. // A curse shall be in his mouth as sweet as honey as it was in ourmouths, our mouths as / sweet as honey. Revulsive as a flux of foxbane, asoffal—and he will seem a lostling. // He came for blood and it will cover him.”

Forher fifth full-length poetry title,

Vixen

(Toronto ON: Book*Hug Press,2023), Ottawa poet and editor Sandra Ridley blends medieval language around women,foxes and the fox hunt alongside ecological collapse, intimate partner violenceand stalking into a book-length lyric that swirls around and across first-personfable, chance encounter and an ever-present brutality. Following hercollections

Fallout

(Regina SK: Hagios Press, 2009) [see my review of such here],

Post-Apothecary

(Toronto ON: Pedlar Press, 2011) [see my review of such here],

The Counting House

(BookThug, 2013) [see my review of such here] and the Griffin Prize-shortlisted

Silvija

(BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here], the language of Vixenis visceral, lyric and loaded with compassion and violence, offering both alanguid beauty and an underlying urgency. “If he has a love for such,” shewrites, as part of the second poem-section, “or if loathing did not preventhim. // A curse shall be in his mouth as sweet as honey as it was in ourmouths, our mouths as / sweet as honey. Revulsive as a flux of foxbane, asoffal—and he will seem a lostling. // He came for blood and it will cover him.”Setin six extended poem-sections—“THICKET,” “TWITCHCRAFT,” “THE SEASON OF THE HAUNT,”“THE BEASTS OF SIMPLE CHACE,” “TORCHLIGHT” and “STRICKEN”—Ridley’s poems arecomparable to some of the work of Philadelphia poet Pattie McCarthy for theirshared use of medieval language, weaving vintage language and consideration acrossbook-length structures into a way through to speak to something highlycontemporary. As such, Vixen’s acknowledgments offer a wealth of medievalsources on hunting, and language on and around foxes and against women, much ofwhich blends the two. A line she incorporates from Robert Burton (1621), forexample: “She is a foole, a nasty queane, a slut, a fixin, a scolde [.]”From Francis Quarles (1644), she borrows: “She’s a pestilent vixen when she’sangry, and as proud as Lucifer [.]” Or, as she writes as part of the thirdsection:

Find her in pasture tillall pastures fail her like hawthorns. She will run well and fly.

She slips out of theforest and when compelled she crosses the open country. When she runs, shemakes few turns. When she does turn to bay, she will run upon us and menace andstrongly groan. And for all the strokes or wounds that we can do to her, whileshe can defend herself, she defends herself without complaint.

She will spare fornothing.

Take leave of your hauntand hunt her down—

Till nigh she be overcome.

Thereis something of the use of such language to allow a deeper examination into darkpaths that seem unrelenting, and, as the back cover offers, “compels us to examinethe nature of empathy, what it means to be a compassionate witness, and what happensto us when brutality is so ever-present that we become numb.” Her lines througheach section, each individual poem-suite that accumulates into this full-lengthlyric suite, extend with such courage, grace and connective tissue as to be bythemselves book-length. Saskatchewan born-and-raised Ridley has always workedwith the structure of the long poem, and this collection further highlights anongoing attention to lyric and structure, offering not a book but a poem,book-length; one that extends across a landscape that includes works by Sylvia Legris, Monty Reid, Andrew Suknaski and Robert Kroetsch, among so many others, reachingto see just how far that lyric landscape might travel. And yet, her poems alsogive the sense of a lyric folded over and across itself, lines that collect andimpact upon each other from a multitude of directions and into a singular,polyphonic voice. This is a stunning collection, and deserves to be win everyaward. Approach with caution, please. Or, as she writes as part of the thirdpoem-section:

Look not in the eyes ofany creature. The same creature runs with different names: wolf, vixen, vermin,heathen, honey, harlot, bitch.

November 22, 2023

Wendy Lotterman, A Reaction to Someone Coming In

TIE

In the garden, privacy collideswith wine and Scrabble as I contemplate the single, silicone dome they emptiedon the belt at security. How to keep this in perspective, myself, inadmissible tothat love or what happens on each side of the border? I find it absolutely intolerableto be made to leave the room. Sex and cat toys punctuate the open-concepthonest of first nights at sea with the fluency of decoys that don’t gethomesick. I got lonely, went to church, entered a concept hospital for onlyhair and nails. Zioskirche falls in and out of relation, but only as long asyou think it: that this can and can’t go on forever, that you do and don’t wantthis to go on forever, that you are safe on planes, in a bathroom, captive, asleep,but that it is better to be out, beyond the idea of your secret interior. I squeezedmy thighs tight so I wouldn’t fall off. Like most protests, the bruise willdrain and then return to stasis. Your dreams turn sweet and then uncomfortablysour as sudden death drafts two teams of unequal need. You are slight andresonant. Your twin leaves the party before you can do the same. Come outside,bearing the shape of the house that you come from. Arrive at the diner,rarified by light-years of desire. Volumes of moss will roll out, red hot alongthe lava beside the road. Skies divide, the bed dissolves like Dippin’ Dots. Thereis a secret you don’t yet know how to confess. The game cannot end in a tie,but you are paralyzed by choice, and terrified by the loss of every side.

I’mquite taken with New York-based poet and postdoctoral fellow Wendy Lotterman’sfull-length debut,

A Reaction to Someone Coming In

(New York NY:Futurepoem Books, 2023), following on the heels of her chapbook

Intense Holiday

(After Hours, 2016). The blurbs on the back cover offer descriptorssuch as “percussive” and “scorching,” and Lotterman’s poems and prose-lyricsoffer a swagger and pulsating directness on degrees of family, intimacy,motherhood and sex, composing a layering of direct statements and lyrics thataccumulate across and form into larger narrative structures. “Let us rob them.”the poem “PEARL” opens. “When this family / Is discovered to be the secret ofthat / Family, it is difficult to keep. Up in / The steam room, nursed by /Noise and heat, the faucet talks / Down tapestries of scenes telling /Something other than stories.”

I’mquite taken with New York-based poet and postdoctoral fellow Wendy Lotterman’sfull-length debut,

A Reaction to Someone Coming In

(New York NY:Futurepoem Books, 2023), following on the heels of her chapbook

Intense Holiday

(After Hours, 2016). The blurbs on the back cover offer descriptorssuch as “percussive” and “scorching,” and Lotterman’s poems and prose-lyricsoffer a swagger and pulsating directness on degrees of family, intimacy,motherhood and sex, composing a layering of direct statements and lyrics thataccumulate across and form into larger narrative structures. “Let us rob them.”the poem “PEARL” opens. “When this family / Is discovered to be the secret ofthat / Family, it is difficult to keep. Up in / The steam room, nursed by /Noise and heat, the faucet talks / Down tapestries of scenes telling /Something other than stories.”

November 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Paola Ferrante

Paola Ferrante

[photo credit: Rob Skuja] is a writer living with depression. She has won Grain Magazine’s Short Grain Contest for Poetry, The New Quarterly’s Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award, Room Magazine’s Fiction Contest and was longlisted for the 2020 Journey Prize for the story “When Foxes Die Electric.” Her work appears in After Realism: 24 Stories for the 21st Century, Best Canadian Poetry 2021, North American Review, PRISM International and elsewhere. She was born, and still resides in, Toronto.

Paola Ferrante

[photo credit: Rob Skuja] is a writer living with depression. She has won Grain Magazine’s Short Grain Contest for Poetry, The New Quarterly’s Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award, Room Magazine’s Fiction Contest and was longlisted for the 2020 Journey Prize for the story “When Foxes Die Electric.” Her work appears in After Realism: 24 Stories for the 21st Century, Best Canadian Poetry 2021, North American Review, PRISM International and elsewhere. She was born, and still resides in, Toronto.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, What to Wear When Surviving a Lion Attack , was a book of poetry and at the time, I honestly felt it changed my life in that I felt I could call myself a “real” writer when it happened. In terms of comparing my debut poetry collection to my debut fiction collection, I will say that horror, fairy tales and plenty of animals in the service of exploring women’s experiences also definitely made appearances in my poems, but I think I’ve taken these motifs to a more interesting place in Her Body Among Animals , using the conventions of genre fiction, specifically horror and sci-fi, and meshing that with fairy tales and pop culture to look at how women challenge the boundaries placed on their bodies, and the violence enacted against both women and the earth because of toxic masculinity. What feels different this time is the reach of the book to be honest. Poetry can be a lonelier endeavour than fiction; with poetry you hope that maybe some other poets read your book and like it. With Her Body Among Animals, it’s felt so validating to read reviews of my work that describe exactly what I hoped readers would get from the experience. I couldn’t believe Publishers Weekly gave me a starred review, and having a review from The Toronto Star’s Robert J. Wiersema fulfilled an actual childhood dream. Also, getting compared to a short story great, Alice Munro (NOT in any sense of my style, but in how detailed our worlds both are) pretty much made my day. With fiction, I feel I’ve gotten to hear how people are affected by the work more, and it feels fantastic to know readers are connecting with my work, to talk to the amazing Bookstagrammers and the wonderful readers that I’m so lucky I get to meet at festivals.

2 - How did you come to short stories first, as opposed to, say, long fiction or non-fiction?

I think short fiction co-evolved with my tendency to write poetry, in that I enjoy having a finite space to play around in, as well as the opportunity to experiment with form. With short fiction, I can get away with cool formal tricks, like telling the story of a domestic abuse situation and then juxtaposing it with legends about lizard men, or in the case of “The Underside of A Wing,” a double third person narration technique to mimic the surreal dissociative experience that I had being in a mental health crisis, with lines like “She often experiences excessive worry;the albatross never experiences worry that isn’t excessive. The albatross sometimes experiences worry in social situations; she always worries that others will notice the albatross.” These techniques tend to get really old, fast when attempting a novel-length work of fiction, either feeling forced or gimmicky. I am currently working on a novel, and some of the more unconventional techniques in short fiction definitely don’t work in long-form fiction. As for non-fiction, that is a beast I don’t go anywhere near! I don’t enjoy the nakedness that comes with non-fiction, and I don’t enjoy being beholden to the truth of an event. I’m more of the “why let truth get in the way of a good story” type of person. Plus, every time I go to tell even a realist short story, a metamorphosis into a spider, or a lizard man jumps into the mix. So I truly don’t think non-fiction will ever be for me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Starting a short story is fairly quick; but after the initial idea phase though, I end up in the garbage draft zone for what feels like forever, where I rewrite and rewrite and rewrite the first third of a piece until I’m convinced what’s on the page is a story going somewhere and it starts to look close to its final form. (Alternatively I also might realize the idea I had is going nowhere and the piece gets consigned to the dumpster file on my computer). I’m a fairly slow writer when it comes to short fiction, because not only am I interested in plot and character and voice; at some point my poetry training also kicks in and I spend a lot of time reading my work out loud to make sure the rhythm at a sentence level is also correct for the rhythm of a science. From start to a draft that I’d be sending out to literary magazines, a month is the shortest time I’ve ever taken. “The Underside of a Wing,” which was the hardest piece for me to write in this collection(and which started life as an absolutely awful realist short story in a pet store of all places), actually took about four months, the first two of which were just finding the form and voice to tell it in.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me, stories generally start with a conceptual idea; say “mother experiences postpartum anxiety as a haunting,” or “girl loses herself in relationship while boy falls in love with a literal shadow of herself.” Sometimes stories start from news articles I’ve read as well; the first story in Her Body Among Animals, “When Foxes Die Electric,” was born from an article my husband showed me about a sex robot during a tech convention who was touched too much and actually shut herself down. When it comes to short fiction I’ve learned I’m truly a “pantser;” trying to outline my short stories has never worked for me so it should surprise absolutely nobody that, while of course I want to be working on a book from the very first short story, I honestly have very little idea of what I have is a book at all until maybe 40 000 words in. That’s the point where I could start to see the thematic connections between what I’d written already. That was imperative, because then I could write the next half with the idea that the new stories needed to tie into the thematic ideas of women challenging the boundaries placed on their bodies and of the entitlement of toxic masculinity enacting violence on both women and the natural world. At that point it was a bit like putting a multi-dimensional puzzle together; I had to write stories that dealt with these themes, that used horror and sci-fi and existed in the realm of the speculative, and that, of course, had animal imagery, which was already running rampant throughout the stories of Her Body Among Animals.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?