Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 66

January 9, 2024

two new reviews!

It has been very nice to see two new reviews of my titles pop up lately! Pearl Pirie was good enough to review

World's End,

(ARP Books, 2023)

over at The Miramichi Review

, and

Nick Thran offered this review

of

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press, 2022) via Event magazine; thanks so much! And of course, I'm attempting to keep track of all links to my reviews over at my author site, here.

It has been very nice to see two new reviews of my titles pop up lately! Pearl Pirie was good enough to review

World's End,

(ARP Books, 2023)

over at The Miramichi Review

, and

Nick Thran offered this review

of

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press, 2022) via Event magazine; thanks so much! And of course, I'm attempting to keep track of all links to my reviews over at my author site, here.January 8, 2024

the VERSeFest fundraiser is live!

the VERSeFest fundraiser is live!

to officially launch our rebuilding year, check out perks including an in-person poetry workshop with Stephen Brockwell! manuscript consultations with Madeleine Stratford, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek, Sandra Ridley, Stephen Collis, ryan fitzpatrick, Stephanie Bolster and Annick MacAskill! books, chapbooks and magazine subscriptions! and more to come!

the VERSeFest fundraiser is live!

to officially launch our rebuilding year, check out perks including an in-person poetry workshop with Stephen Brockwell! manuscript consultations with Madeleine Stratford, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek, Sandra Ridley, Stephen Collis, ryan fitzpatrick, Stephanie Bolster and Annick MacAskill! books, chapbooks and magazine subscriptions! and more to come!

January 7, 2024

just emerging from losing four days to the flu,

so everything moving a bit slower than I'd prefer. We landed home from family-travel on Wednesday when I went down almost immediately, and I was properly not out of bed again until yesterday. I slept for nearly three full days! At least my fever broke on Friday night. I'm still feeling a bit worn, so if you are expecting anything from me, patience, please.

so everything moving a bit slower than I'd prefer. We landed home from family-travel on Wednesday when I went down almost immediately, and I was properly not out of bed again until yesterday. I slept for nearly three full days! At least my fever broke on Friday night. I'm still feeling a bit worn, so if you are expecting anything from me, patience, please.January 6, 2024

A ‘best of’ list of 2023 Canadian poetry books

Once more, I offer my annual list of theseemingly-arbitrary “worth repeating” (given ‘best’ is such an inconclusive,imprecise designation), constructed from the list of Canadian poetry titlesI’ve managed to review throughout the past year. This is my thirteenth annual list [see also: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018,2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011] since dusie-maven Susana Gardneroriginally suggested various dusie-esque poets write up their own versions ofsame, and I thank her both for the ongoing opportunity, and her original prompt.

Once more, I offer my annual list of theseemingly-arbitrary “worth repeating” (given ‘best’ is such an inconclusive,imprecise designation), constructed from the list of Canadian poetry titlesI’ve managed to review throughout the past year. This is my thirteenth annual list [see also: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018,2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011] since dusie-maven Susana Gardneroriginally suggested various dusie-esque poets write up their own versions ofsame, and I thank her both for the ongoing opportunity, and her original prompt.It does feel as though I’ve done far fewer reviewsthis year than across the prior few, overloaded with a couple of largenon-fiction projects and various other book deadlines, etcetera. There wereplenty of books I simply didn’t manage to get to yet; or are there simply morebooks? There is still a handful of titles from this year I have yet to get to,certainly (including the new Judith Copithorne, which looks brilliant), but unlessI do a count, I haven’t a clue how many reviews I’ve actually managed. The factthat I’ve “only” thirty-eight on this list (compared to other years) suggeststo me that I haven’t reviewed nearly as much this year as I’ve done prior(which I’ve suspected throughout the year, simply busy with other things; andthere are certain Canadian publishers that simply haven’t been sending booksalong, frustratingly), although my count shows I’ve posted some one hundred andforty book reviews across 2023, which is quite a lot. I’m pleased I managed toget a mound of chapbook reviews posted, as well as some journal reviews (somethingI hadn’t been doing nearly as much across the year or two prior), composingreviews of The Capilano Review : 50th Anniversary Issue(s) : 3:46-3:48[see my review here], SOME : sixth issue [see my review here], fillingStation #81 : Some Kind of Dopamine Hit [see my review here] and SOME:seventh issue [see my review here]. There’s also been a plethora of worthy non-fictionprose reviews I’ve posted, with stellar works including INDIGIQUEERNESS:Joshua Whitehead In Dialogue with Angie Abdou (Athabasca University Press,2023) [see my review of such here], Gail Scott, Furniture Music: A Northernin Manhattan: Poets/Politics [2008-2012] (Wave Books, 2023) [see my review of such here] and Jim Johnstone, Write Print Fold and Staple: On Poetry andMicropress in Canada (Gaspereau Press, 2023) [see my review of such here].

Barry McKinnon died this past year, so that was a bitof a hit [see my obituary for him here].

I wonder, occasionally, if I should be working similar‘best of’ lists for chapbooks, or American full-length collections, or fiction,or a geographically-unspecified list of full-length collections, but then I rememberthat this list takes a full day to compile and post, so there you go. And youknow this list always includes a few stragglers from the year prior, yes? I mean,I can only do so much during a calendar year. Beyond that, I always mean forthese lists to be shorter, but I couldn’t think of a list without includingevery book on this list. Is there simply too much exciting work being producedright now?

This year’s list includes full-length poetry titles by Dale Tracy, Khashayar Mohammadi/Saeed Tavanaee Marvi, Manahil Bandukwala, David Dowker, Erin Robinsong, natalie hanna, Jason Purcell, ryan fitzpatrick, Milton Acorn and bill bissett, George Bowering, Dennis Cooley, Jen Currin, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek, Kate Siklosi, Gary Barwin and Lillian Nećakov, Camille Martin, Matthew Hollett, Laila Malik, Emily Osborne, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Weyman Chan, Alycia Pirmohamed, Amy Ching-Yan Lam, Kate Cayley, Jake Byrne, Natalie Rice, Tom Cull, David Martin, Erín Moure, Adam Beardsworth, Jim Johnstone, Amanda Earl, Shane Book, Sandra Ridley, andrea bennett, Nikki Reimer, Ben Meyerson and Matthew Gwathmey.

See this year's full list here.

January 5, 2024

Spotlight series #93 : Emma Rhodes

The ninety-third in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes

.

The ninety-third in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa and California poet Kyla Houbolt.

The whole series can be found online here .

January 4, 2024

today is kate's thirty-third birthday,

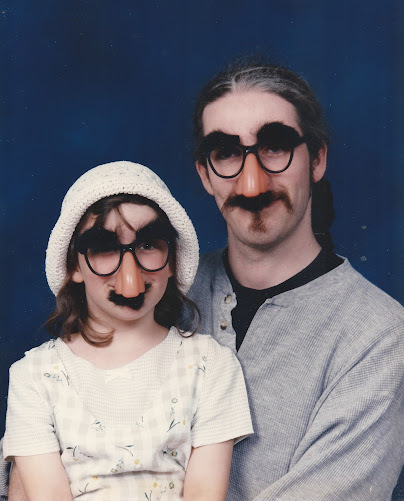

My eldest child turns thirty-three years old today! Happy birthday!

My eldest child turns thirty-three years old today! Happy birthday!Here's a photo we got at the Bay Photo Studio on Rideau Street when she was around seven or so (a photo I have up in my office). I had a coupon for a free 8x10, so thought this would be fun to do as a session. Kate's mother politely declined to participate, and held our coats instead. When my mother heard we were doing photos, she paid for extra copies for herself, although when she finally saw the finished product, she was horrified. I don't think she ever distributed any of her copies.

A few years later, I wanted to do a second session, where Kate and I braid our long hair and dress up as vikings (fur and hats with horns and swords, etcetera), but she responded by immediately getting her hair cut.

January 3, 2024

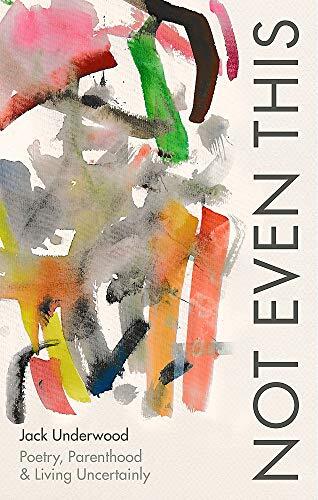

Jack Underwood, Not Even This: Poetry, Parenthood & Living Uncertainly

An obvious analogy occurs:the similarity between the positioning of your miscellaneous objects, and thebusiness of shifting a poem about on a page. Wait, OK, now I understand exactlywhat you’re doing: that need to go back over and over, resting configurations,rehearsing the through-lines and relations … the muttering and staring intospace, and yes, admittedly, when I’m tired and feel that I cannot convey mypredicament, or the correct formal arrangement does not materialize I, too, knowthat inconsolable frustration … Words have to be right, and in the right orderand position.

Christinewas good enough to gift a paperback copy of British poet Jack Underwood’s NotEven This: Poetry, Parenthood & Living Uncertainly (Corsair, 2021), thinkingI might be interested in this blend of poetry, parenting and uncertainty, abook I spent the bulk of Christmas Day quietly reading as the kids disassembledtheir gifts and wandered into their corners (last year she gifted a memoir by Stanley Tucci, which I devoured in a day or two, but did not write about). I hadn’theard of Jack Underwood prior to this, but his author biography offers that heis the author of a debut poetry title, Happiness (Faber & Faber,2015), as well a follow-up,

A Year in the New Life

(Faber & Faber,2021). Certainly, Underwood’s Not Even This provides a curiouscounterpoint to my own book on uncertainty: whereas mine focused on the centralpoint of original Covid lockdown, Underwood’s essay-memoir focuses on the swirling(and natural) uncertainty—blending fear, curiosity, delight and bafflement—of becominga parent for the first time, both books circling out from their central thesesthrough a lens of writing, poetry and the structures of thought poetry allows. “Maybeuncertainty can be a positive position in knowledge, like Keats’s ‘negativecapability’,” he offers, early on in the book.

Christinewas good enough to gift a paperback copy of British poet Jack Underwood’s NotEven This: Poetry, Parenthood & Living Uncertainly (Corsair, 2021), thinkingI might be interested in this blend of poetry, parenting and uncertainty, abook I spent the bulk of Christmas Day quietly reading as the kids disassembledtheir gifts and wandered into their corners (last year she gifted a memoir by Stanley Tucci, which I devoured in a day or two, but did not write about). I hadn’theard of Jack Underwood prior to this, but his author biography offers that heis the author of a debut poetry title, Happiness (Faber & Faber,2015), as well a follow-up,

A Year in the New Life

(Faber & Faber,2021). Certainly, Underwood’s Not Even This provides a curiouscounterpoint to my own book on uncertainty: whereas mine focused on the centralpoint of original Covid lockdown, Underwood’s essay-memoir focuses on the swirling(and natural) uncertainty—blending fear, curiosity, delight and bafflement—of becominga parent for the first time, both books circling out from their central thesesthrough a lens of writing, poetry and the structures of thought poetry allows. “Maybeuncertainty can be a positive position in knowledge, like Keats’s ‘negativecapability’,” he offers, early on in the book.Thereis a way in which Underwood speaks of uncertainty as both goal and approach. “Iwant to live more uncertainly,” he writes, “and to understand uncertainty as afundamental feature of how I know the world. I want to be less wasteful andreductive through it. And I want you to have a fuller, more profound experienceof being alive by also being able to be in uncertainty.” It is as though he is attemptingto articulate wishing to be more open to speculation, the accident and a kindof unknowing, writing through and around subject in ways I find similar toAmerican poet and essayist Elisa Gabbert; it is almost as though his argument opensfrom a foundation of reason, attempting to move beyond conscious reason. One mightalmost wish to introduce him to Canadian poet Fred Wah’s notion of ‘drunken taichi,’ a notion of deliberately moving off-balance to reveal what the body, whatthe mind, already intuitively knows, but that might be an argument for anotherday.

January 2, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joe Baumann

Joe Baumann is the author of four collections of short fiction, most recently

Where Can I Take You When There’s Nowhere to Go

, from BOA Editions, and the novels

I Know You’re Out There Somewhere

and

Lake, Drive

. His fiction and essays have appeared in Third Coast, Passages North, Phantom Drift, and many others. He possesses a PhD in English from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette. He was a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellow in Fiction. He can be reached at joebaumann.wordpress.com.

Joe Baumann is the author of four collections of short fiction, most recently

Where Can I Take You When There’s Nowhere to Go

, from BOA Editions, and the novels

I Know You’re Out There Somewhere

and

Lake, Drive

. His fiction and essays have appeared in Third Coast, Passages North, Phantom Drift, and many others. He possesses a PhD in English from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette. He was a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellow in Fiction. He can be reached at joebaumann.wordpress.com.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Oh gosh--in so many ways. I think beyond anything else it felt validating and gave me a certain confidence in what I was doing, that after all of the no answers, I really was onto something that would, could, and did lead to a yes.

I think my recent work actually still emulates a lot of what I was up to in previous work thematically, in many ways, although the subjects have changed--as I've gotten older, so have my protagonists, and the kinds of "issues" they're facing have matured as I have.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Actually, I have a pretty weirdly circuitous path that led me to where I am now. When I started college two decades ago (eep!), I was convinced I would spend my life writing fiction and poetry. It became immediately clear I was not meant to do much of the latter. But I also struggled with fiction. I took a nonfiction course with a professor I really liked from taking my introductory course, and I was hooked--my senior project for my BA as well as my master's thesis were both in creative nonfiction, and it wasn't until I was doing my PhD and rolled the dice on taking my first fiction-focused course in about five years that I fell back in love with fiction, and I've largely stayed there (with dabblings into the other two) since.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am not much of a note-taker, or planner, except for the former when I get into revision. Otherwise, I usually start with some goofy premise and not much else and I spend a ton of time figuring out what that idea is about. So the start is usually pretty fast, and sometimes there's a dip as I wander about trying to figure things out.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

If I'm working in short form (which is my favorite), I usually begin with an opening sentence that marinates for a little bit in my brain before I set it down on the page. Then I explore from there, and figure things out as I draft and try things out. Sometimes I'm working on a book conceptually--for example, I have a book of stories where each story reimagines one of the biblical plagues of Egypt, and I knew that I was trying to write one of each of those from the start. Other times, a collection simply emerges out of a larger pool of stories where I start to see thematic connections.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings, whether they're open mic nights on my campus or planned events. And I also love attending them--hearing other writers really helps get my creative work moving.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The fundamental question that I'm always looking at, from some angle (as I think almost all writers are), is What does it mean to be a human being? I'm also deeply interested in the human desire for rationality and the complete irrationality of humanness, particularly as it relates to experiencing and responding to human emotions.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oof! That's a big one. I think the work of a writer these days is to capture the cultural now--though that 'now' can be a different time (and different place) within the world of a particular story. We can't divorce ourselves entirely from the way the social, political, and historical landscape looks outside our writing nooks, and I think it's the writer's job to confront the tides of the world and make people think about them.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Sometimes both. I love getting outside eyes to see what I'm too close to see, but I also don't want to have my vision stifled by someone else's vision for what my work "should" be, if that makes sense.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

That a great ending is both inevitable and unexpected.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel to young adult fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Pretty easy--I like working on several things at once, and I actually like when they are very different. I find it fun to switch modes, as they play against one another in interesting ways.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I almost exclusively write in the morning and then edit/revise when I can during the afternoons/evenings around my work schedule. I usually spend a short period on each piece I'm working on (never really usually generating more than a page or two per project in a given day). I've followed this for about ten years, and it's really worked for me.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The things I read. I read a ton, and if I'm stuck, I'll often read something that will unstick me.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Vanilla and apples--two of my favorite baking smells.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

TV has actually influenced me a lot. I loved Buffy the Vampire Slayer when I was young. I don't watch as much television as I used to, but the shows that drew me in years ago have stuck with me.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I'll follow Jennifer Egan, Adam Johnson, Ramona Ausubel, and Margaret Atwood to the ends of the earth. I read the magic realists from Latin American religiously (in translation).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I've had some ideas for screen--television--but haven't ever really pulled the trigger.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

There was a time where I thought I'd be an eye doctor, and that would certainly still be neat (though quite the sea change).

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don't really know, to be honest. I've always had an interest in the creative; I wrote my first 'story' (a ripoff of a cartoon I loved as a kid) when I was in 2nd grade. I think invention just appealed to me, and I never let that appeal go.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just reread Hernan Diaz's Trust, which continues to fool and amaze me. I don't sit down to watch movies that often, but I recently rewatched Parasite and loved it as much as I did the first time.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Well, I just finished the garbage draft of a novel for NaNoWriMo, but I'm setting that aside for awhile to return to a surreal Southern campus novel about a young faculty member at a private college in Louisiana where strange things begin happening to administrators. The original draft was jammed with too much stuff, but after several months of letting it marinate I think I have a plan forward, so I'm excited to return to that project.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 31, 2023

Gale Marie Thompson, Mountain Amnesia: Poems

A Rank, Bleak Devotion

That violence lies inwriting is not so far

from the truth. This isthe animal I knew before

I started, whose neck I wishedto rub my own against.

She brings the word mercyinto the field.

Her mouth staggers overthe counting, the one

and one and one of bodiessoaked in oil. In the blue

of gathered facts itfeels the same: splattered

mouth, bloody bulb of thesign. I keep practicing

the problem, To getback at, to get back at, the letters

written on a field ofdark paper, disorder.

I make lists. I peelonions beneath my skin

and push them out of me. Iwake up

in the morning andrealize that a sex dream

can also be a sexual assaultdream. Mercy, healing—

these are words I’venever used in a poem before.

Can I write into her, shewhose own wool

touches mine? A blunterway to say: am I a body

who depends on otherbodies? I make lists.

A loved posture can alsobe a speech act.

This is how it begins. Whatwill seep will seep.

Havingdeeply enjoyed North Georgia poet Gale Marie Thompson’s second full-lengthcollection,

Helen or My Hunger

(Portland OR: YesYes Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], I was very excited to see her latest:

Mountain Amnesia: Poems

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for Literary Publishing, 2023),winner of the Colorado Prize for Poetry. As final judge Felicia Zamora writesof the collection: “Mountain Amnesia stretches thin the fibrous tissuesof grief that inhabit the body, mind, and ether of existence from burrowingtraumas. These lamentations expose the weight of abuse, longing and loss,unanswered prayers, and an inescapable natural law: ‘this I know: that evenevil men die.’” There’s such an unflinching sharpness to these poems, andThompson’s is a fierce and precise first-person lyric of violence, dark survivaland a weighted grief. “In the time it took to produce / this sentence,” shewrites, to open the poem “Turnover,” “the spinal // shadow of my house hasleaned / its wet angle over the yard // so completely, a massacre / so small—yetloved, like // the family lick of the herd— [.]” In this third full-lengthcollection, Thompson continues her engagement through densely-packed lyricsthat explore dark paths, dark threads: a thread I’ve increasingly seen across Americanpoetry these past few years, whether exploring titles by YesYes Books generally(including recent titles by Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach [see my review here], Alycia Pirmohamed [see my review here] and Allison Blevins [see my review here]), ortitles such as Jenny Molberg’s The Court of No Record (Louisiana StateUniversity Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] and Claire Schwartz’s CivilService (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2022) [see my review of such here].“There must be an aphorism here / about thunder and discipline,” she writes, aspart of “The Law of Jocasta,” the poem Felicia Zamora quotes from as part ofher blurb, “how its roll and hone engraves / from inside. Even Queen Elizabeth/ once remade herself a virgin / in this soggy, pink light. Because / this I know:that even evil men die. / It’s constitutional. It’s the law.”

Havingdeeply enjoyed North Georgia poet Gale Marie Thompson’s second full-lengthcollection,

Helen or My Hunger

(Portland OR: YesYes Books, 2020) [see my review of such here], I was very excited to see her latest:

Mountain Amnesia: Poems

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for Literary Publishing, 2023),winner of the Colorado Prize for Poetry. As final judge Felicia Zamora writesof the collection: “Mountain Amnesia stretches thin the fibrous tissuesof grief that inhabit the body, mind, and ether of existence from burrowingtraumas. These lamentations expose the weight of abuse, longing and loss,unanswered prayers, and an inescapable natural law: ‘this I know: that evenevil men die.’” There’s such an unflinching sharpness to these poems, andThompson’s is a fierce and precise first-person lyric of violence, dark survivaland a weighted grief. “In the time it took to produce / this sentence,” shewrites, to open the poem “Turnover,” “the spinal // shadow of my house hasleaned / its wet angle over the yard // so completely, a massacre / so small—yetloved, like // the family lick of the herd— [.]” In this third full-lengthcollection, Thompson continues her engagement through densely-packed lyricsthat explore dark paths, dark threads: a thread I’ve increasingly seen across Americanpoetry these past few years, whether exploring titles by YesYes Books generally(including recent titles by Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach [see my review here], Alycia Pirmohamed [see my review here] and Allison Blevins [see my review here]), ortitles such as Jenny Molberg’s The Court of No Record (Louisiana StateUniversity Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] and Claire Schwartz’s CivilService (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2022) [see my review of such here].“There must be an aphorism here / about thunder and discipline,” she writes, aspart of “The Law of Jocasta,” the poem Felicia Zamora quotes from as part ofher blurb, “how its roll and hone engraves / from inside. Even Queen Elizabeth/ once remade herself a virgin / in this soggy, pink light. Because / this I know:that even evil men die. / It’s constitutional. It’s the law.”Setas a quartet of numbered groupings of poems, Thompson’s poems don’t merelyexamine, but simultaneously dismantle and reassemble; one might describe thepoems in this collection as as exploring the dark shadows of human experience. “Marchkilled so much this year / just like every year. I hear that death exists,” shewrites, as part of the poem “No Witness,” “I hear it and I hear it, / but I keepmy mouth away from the wind, / I keep its noises muddied in the woods.” It is abook of survival mechanisms, witness and deep grief, and composing these piecesas a way to push through to the other end, or at least, as close as might bepossible. As part of her December 2021 ’12 or 20 questions’ interview, shedescribes her then-work-in-progress, a manuscript she responds via email is anearlier iteration of Mountain Amnesia:

I’ve been working on thismanuscript called Dummy Prayer for a number of years now, and new poemscome in each year and change its face a bit more each time. During the pandemicI’ve been hiking and reading in the mountains around where I live, and evenbefore the pandemic I was living a pretty isolated life here in North Georgia.Over the last few years, I’ve had a few friends pass away unexpectedly, as wellas some other losses and oblivions and changes that (like always) have affectedmy relationship with the world. So, all of that together means that my poemsare very much influenced by the messiness of nature in Appalachia, along withthe messiness of loneliness and grief, of a longing for connection. In thesepoems, nature is constantly working on its own disappearance. The rottingplants and animal bones and organic matter are housed in the same world as theramps and bellflowers on the verge of opening. All this to say, I’ve beenthinking quite a bit about how we connect with each other, or, to quoteAdrienne Rich, “the grit of human arrangements and relationships: how we arewith each other.” The frictions in communicating public and private experiencesto each other. And so I was thinking about these arrangements, how we keep eachother alive, and that’s a huge part of Dummy Prayer.

December 30, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brandon Reid

Brandon Reid [photo credit: Kevin Cruz] holds a B.Ed. fromUBC, with a specialization in Indigenous education, and a journalism diplomafrom Langara College. His work has been published in the Barely South Review,The Richmond Review and The Province. He is a member of theHeiltsuk First Nation, with a mix of Indigenous and English ancestry. Heresides in Richmond, BC, where he works as a TTOC. In his spare time, he enjoyscooking, playing music and listening to comedy podcasts.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Istopped worrying about what happened to me, as I no longer had to protectmyself to finish the book; I don’t sleep as much, now. I still take care ofmyself, of course (from time to time), but I no longer feel I have a duty tofulfill. The book also gave me confidence I didn’t have before. I would behesitant to call myself a writer, but now I’m proud to do so. I have apublished book out, that’s quite the accomplishment.

Beautiful Beautiful is my debut novel, althoughI self-published a book called Angel Hair Pasta on Amazon before. It wasabout a female chef working in LA and Seattle. It almost made me a toonie. Istill enjoy that book—it has satisfying sections of modernist first-personwriting—but Beautiful Beautiful is a much more thorough, meaningfulwork.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say,poetry or non-fiction?

WhenI was six or so, my friend and I had a competition who could make the bettercharacter/fighter. I came up with a multi-headed dragon that could only bestaggered by firing a fireball from the sun into its chest—wasn’t clear how itcould ever be defeated. We drew our characters, and then created backstoriesfor them. I continued creating characters, and I’d usually act out their storiesby myself in the park or living room. Then one day, a relative bought me ajournal, so I tried writing down these oral stories I was telling myself. They hardlywent anywhere, but that was the genesis. I drew and wrote a lot in school, too,during lessons, to keep myself occupied. I’d burn through several drawing booksa year, as most teachers were kind and encouraging enough to bestow as many asI requested.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Itreally depends. Generally, I try and let ideas blossom for a few weeks beforestarting, even if I’m eager to use new premises. Words flow easily while I’minspired, and incubation can generate inspiration. It’s not like an ice-creamcone, where you have to lick it all at once. I force myself to meet a word count,once I’ve begun writing a manuscript. I write at least 2,000 words a day, whichtakes approximately 2 to 3 hours. Some manuscripts require more research orthought, like I wrote a lot of sci-fi, which involved constant googling andconversing with ChatGPT about existentialism, aliens or space technology. Sci-firequires lots of details.

My first drafts are usually completelydifferent than the finished works. My words aren’t precious to me, so I likesacrificing them for something better. To be honest, I don’t think themanuscripts always get better; the first drafts are like sketches, which havetheir appeal, opposed to the meticulous final-drafts. It’s like Bob Dylanversus the Beatles: the former preferred minimal takes, usually, while thelatter would sometimes perform dozens of takes, especially in the later years. BeautifulBeautiful was linear in the beginning, then I utilized in medias res later,shifting parts around. Stephen King said try and write the first draft in threemonths, so I aim for that, then lend myself as much time required in theediting process.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are youan author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or areyou working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’monly concerned with writing books at this point, so that’s my initialintention. I think of certain scenes, like a storyboard, and then I work fromthe beginning until the end in one constant flow. I don’t plan a lot of it, Ijust add scenes that make sense—one after the other, shifting from positive tonegative—progressing until the end. I may have a clear idea of where I’d liketo end up, but I usually can’t predict the result. It’s like decoding a moviein my head: I’ll write a scene, then the fog will clear, and the best wayforward is revealed.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ithink they aid the creative process in the same way teaching does, in that Igauge the reactions of the audience, and realize what works and what doesn’t.That being said, I recognize reading aloud is different than reading quietly. Ienjoy sharing pieces intentionally crafted to be spoken, but I don’tnecessarily desire to read my books to people—it’s a different experience, auditoryinstead of visual, that sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

Wow,those are great questions, I’ll do my best to answer them. I would say I’m equallyconcerned with the theoretical as I am the plot. This is evidenced by the titleBeautiful Beautiful itself, as I strive to uncover the aesthetics ofwords and literature. I’m constantly thinking about why I write, the highermeaning. To me, Redbird is a songbird, singing the words. You can read into thedifferences between Indigenous and Western storytelling with BeautifulBeautiful. You may also apply a feminist reading using the internal logicof the tarot, that water and earth represent femininity. Or perhaps one may enjoyreading Raven as the archetypal raven. There were many lenses I applied to thebook. Of course, there’s plenty of cheese, as well.

There are so many questions I tryanswering through writing: what’s the difference between depicting dialogue andcommuning with spirits? How can I better articulate the thought chains of mymind? Does this work better to reach into the reader? Stuff like that. Mywriting is me capturing epiphanies I have along the way—about myself, aboutothers, about life. I hope that makes it exciting for the reader.

One current question I’m fascinatedwith, is what can a human do that an AI won’t be able to? I heard AI will developto the point it will be able to produce literature of any kind upon request. “Iwant a sequel to The Return of the King,” you’ll say, and your wish will begranted. What, then, will set humans apart from AI? It’s something I’mconstantly thinking about, how to stay ahead of the robot, basically.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Tobring book clubs together. I think most popular books help establish acommunity or tackle pressing issues. I don’t read many contemporary books. They’reoften too focused on plot for my liking. I enjoy reading books I either hardly comprehendor that are inventive with language. It’s a viable function, for a writer toappeal to the masses, but I realize most of my literary influences diedpenniless or lacked popularity in their times.

I think it’s fair some writers excelat marketing and business, but I’m interested in writers who convey a mind-setnot yet found in literature, above all else. The writer is one who documentstheir experience reaching into the realm of spirit so all may behold a glimpse,because even that is insufficient to describe the vision I have of what writingis. Sometimes it’s easy to explain what is seen, other times, simplicity onlymars the glory of that sight unfolding. Writers fall somewhere along thatgradient, and they’re all equally writers.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

It’sa difficult question. As I said earlier, some of my first drafts areinteresting and enjoyable. The editor is someone who hones the work so it’saccessible for readers. In that sense, they’re essential; I wouldn’t expect AngelHair Pasta to be found on bookshelves. I view working with an editor as acollaboration, and I really enjoy that element of the process. If it’sdifficult, it’s only difficult because we both set a standard that I ultimatelyhave to reach, so I have to push myself which I wouldn’t say is easy or lovely,it’s hard work that requires dedication and focus. I feel all the better forit, however.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Ateacher gave me an appropriate grade for a mediocre piece of writing Isubmitted, then at the end of their comments, they wrote, “Keep writing!”That’s all it took to encourage me to keep at it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(fiction to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal?

Writingfor journalism was easy, it was interviewing people while seeming credible thatwas difficult. Journalism is a fantastic foundation for writers, as it teachesyou to make a word count, respect deadlines, write concisely, edit thoroughly, handleinformation accurately, format well, and accurately record dialogue. There’s arich tradition of journalists who learned the essentials then branched outcreatively. Hunter S. Thompson is a classic example; he really blurred the linebetween each. The appeal for me is, there’s only so many ways I can objectivelywrite about a situation before getting bored and seeking the alternative meansof expression fiction offers.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Iwake up, put on headphones, listen to Spotify for an hour or two, get up, makemy bed, adore the sun, brush my teeth, get an espresso, check the web, pray,meditate, exercise, stretch, adore the sun for noon, make myself a cappuccino, hopefullysit down to some fresh fruit and madeleines supplemented with vitamins, then,generally speaking, I’m in peak writing-form. That all goes out the window if Imust head out to work.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Usually,music or reading other books. Inspiration can come from anywhere, though. Couldbe something I read online, something someone said to me—usually comes out of thinair. I force myself to meet my word-count, regardless, otherwise I don’tbother. Sometimes it’s good to sit around, waiting for inspiration, but if I’mimmersed in writing, I trudge on, even while uninspired by what I’m writing, asI know I can improve it in the edit. Craft endures while inspiration falters.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Smolderingsage smoke.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Asa polymath, I’m a strong believer all my experiences affect my writing. Cookingallows me to better capture the senses affected while cooking, which helps metranslate them to the page. It’s true, reading books helps writers learn thecraft, but you get to a certain point—where you develop your voice, yourability and your style—that you don’t necessarily need to be an avid reader. John Lennon said something similar, in that he didn’t listen to popular music, as itwas all variations of music he heard growing up.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Idon’t know if I’d consider them important to me, more so integrated into myconsciousness—probably the same thing. You know, James Joyce is my biggestinfluence. Aleister Crowley restored my faith. Moby Dick was a profoundnovel for me. Most writers that influenced me have passed.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’dlike to travel across Canada, perhaps by train. I feel that’s a true Canadianexperience.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

I’dtry being a musician. I’ve played various instruments throughout my life:guitar, piano, drums, saxophone. I wrote many songs in my 20s, and performedthem with a friend, but I didn’t really desire to play for anyone but us.

I promised myself, inhigh school, that if I was still single and had nothing going on by 23, I’ddrop everything and join the army. I wound up quitting my job, at 23, to write over3,000 words a day by hand, every day, for a year. I suppose I fatigued myselfmanifesting various partners through writing, instead.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Ijust found myself alone, a lot, so I manifested my own worlds of companions. Writingis the ultimate solitary act, after all. Perhaps I made a shell of sorts.Writing got me through many troubling times, as did playing music. Writing satisfiesme more than anything else, so I keep doing it. It sort of avoids definitionbeyond that.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Irecently finished Dante’s Paradiso, of all things. It was fun, followingthe rhythm, but it was an archaic version that was difficult to comprehend,which I state too often I enjoy.

I don’t watch many films. I used to. I watchedTitanic a few months back. Go ahead and laugh if you want. I’m prettysappy.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’mcurrently working on a novel about Raven, from Beautiful Beautiful, utilizingmy experience in the culinary industry.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;