Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 63

February 8, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Trevor Mahon

Born in northern Ontario,

Trevor Mahon

now calls Ottawa home. Having spent his childhood in a half-dozen Ontariotowns, which taught him how to avoid wearing out his welcome, he lives with hiswife and son in the suburbs and can often be found indoors or outdoors, butalmost never in the ducts of an office tower.

The Man Who Hunted Ice

, his firstnovel, distills his fascination with the absurdity of celebrity.

Born in northern Ontario,

Trevor Mahon

now calls Ottawa home. Having spent his childhood in a half-dozen Ontariotowns, which taught him how to avoid wearing out his welcome, he lives with hiswife and son in the suburbs and can often be found indoors or outdoors, butalmost never in the ducts of an office tower.

The Man Who Hunted Ice

, his firstnovel, distills his fascination with the absurdity of celebrity.1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

I've had to learn howto sign a legible autograph. Also had to learn to come up with a personalinscription on the spot while the recipient of the inscription is talking tome. Way more difficult than expected. Otherwise, life remains much the same! Asthis is my first published work, I have nothing to compare it to. I think it'sbetter than my previous attempts, but I also think I can do much better.

2 - How did you come tofiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I've been makingstories up since I was a kid. I read non-fiction almost exclusively now,strangely enough, but have no interest in writing about reality, it seems.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I have a hard timetaking the leap and writing that first line. I make a lot of notes and plan outthings before actually writing, although I'm working on streamlining things.It's definitely a slow process, which helps, because ideas come to me months intoa story that I hadn't considered when I was starting out. I tend to vomit itall onto the page and then slash and burn in the editing process, although plotusually remains the same from beginning to end.

4 - Where does a workof prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I was apparently bornin the wrong century, because novels are my favourite form. Occasionally I'llattempt a short story, but I tend to rush it too much and then forget about it.I've come to have an enormous respect and admiration (i.e. envy) for people whocan write short fiction well.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

Public readings terrifyme. I did one for my book launch in front of a small and very friendly crowdand that was enough. (All the same, maybe they get easier as one goes along.)

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Yes and no. Basically,I want to tell a good story and write a good novel, although I suppose I'mdrawn to tragicomedy because it strikes me as exceptionally human--if a humanis lucky enough not to live out a full tragedy. I also dig the notion of a "whatif" story: in my novel The Man Who Hunted Ice, I explored ascenario where a random person doing a random job becomes as famous as aprofessional athlete. I love Herman Melville's short story "Bartleby, theScrivener" because it's a classic "what if": what if you had anemployee who stopped doing his job but wouldn't leave the workplace?

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

As Joyce wrote(essentially), "to forge in the smithy of their soul the uncreatedconscience of their race" (or, better, species). And/or to tell goodstories. If you can do one or the other (or both), you've proven yourselfuseful.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both! A good editor isworth their weight in gold, even if a good editor isn't always your pal.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Hemingway and Johnsonboth wrote something similar about removing "good" lines, lines thatyou're proud of, and letting what's left tell the story. Took me a long, longtime to understand that wisdom. I'm still working on it.

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I've gotten busier overthe past couple of years, so I set a word quota (which can change from projectto project) and pick away at it during the day, especially the morning. If Iset the quota too high, I tend to ramble; too low, and it takes too long tofinish. Still working on finding the sweet spot. If I get a chance to writeearly in the day, I can be amazingly productive--though that doesn't happennearly as often as I'd like!

11 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I wish I could say I goout and sit in nature or drive to New York and sit in Central Park andpeople-watch, but no. For me, it's consistency, persistence, routine. Not avery exciting answer, but "keeping warm" gets me through the dryspells.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Cold winter air andwood smoke.

13 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Movies to an extent,since I watched a whack of them when I was a teen/twentysomething. Morerecently, Parasite and Us got my juices flowing, even though I'm not really ahorror-comedy guy. (Or am I?) I really liked The Banshees of Inisherin.A really good movie makes me want to do the equivalent with a novel.

14 - What other writersor writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of yourwork?

I keep three novels onmy desk: , The Remains of the Dayby Kazuo Ishiguro, and The Man Who Was Thursday by G. K. Chesterton. Ithink if you cracked my head open and pulled out the SIM card, you'd find thosebooks--for better or for worse--in the software, explaining how my creativemind works, or tries to work. Blame those guys.

15 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

Oh, man. Lots ofthings. But are they worth it? Easy answers: write a legible autograph, writesomething really good.

16 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Professional athlete,if I had my choice of physique and talent (and age)? Actually, I've alwaysenvied people who do fascinating jobs and say they picked their careers whenthey were children. I read a book once by a forensic anthropologist who gotinterested in the field at a very young age, whereas I'm still wondering whatI'm going to do when I grow up.

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

Luckily, I do somethingelse, which pays the bills. I'd write anyway, but if I had to support myselfthrough my writing, I'd have starved long ago.

18 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

The Warmth of OtherSunsby Isabel Wilkerson was fantastic. I expect to be tongue-tied if I ever get achance to meet the author. That and Endurance by Alfred Lansing, aboutthe 1914 Shackleton expedition, are the two best books I've read in the pastseveral years (both are non-fiction, but read like novels). Last great film:repeating myself, but Parasite. Can't wait to see what Bong Joon-ho doesnext.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

Another tragicomedy,with social-satire elements. Should I go full horror-comedy? Maybe I will.

February 7, 2024

M.W. Jaeggle, Wrack Line

LETTER TO A FRIEND

CONCERNING ANOTHER’SWHEREABOUTS

He’s at that cabin on theCariboo plateau,

that one he’s alwaysyapping about,

washing chipped bowlswith lake water,

careful not to getneedle-thin bones stuck in the drain.

He keeps the big red gatelocked, the chintz curtains closed.

The garden, long gone tothistle, is home

to his eggshells, burntbarley, soup dregs.

Nothing can stop him frommundane pleasures,

catching rainbow troutonly to release them,

noon-warm tea with Kundera,a few laughs

from Diefenbaker onvinyl.

He’s in the cabin at theend of Antoine Lake Road,

counting cracks in thefoundation, where the rooms

are parting ways. He’s inthat tin-roof tinderbox,

cataloguing birds,flowers, stones,

watching Bogart movies,

reconciling Clapton with Buddhism.

If you were to ask him ifit gets lonely

in the hush of the cabin,he’d say

he’s distracted easily.

I’veknown his name for a while now (through seeing copies of his three published chapbooks),so was curious to see a copy of

Wrack Line

(Regina SK: University ofRegina Press, 2023), the full-length debut by Vancouver-born Buffalo, New York poet M.W. Jaeggle. Wrack Line is a collection of carved lyrics exploringand examining form, from prose blocks to sonnets to more open forms of thelyric. Jaeggle works through first-person lyric narratives to articulate grief,loss and distraction, writing out the distances and the distances between, asthe piece “POEM BY FRIDGE LIGHT” offers: “Here I am in the culvert where wefound a car’s die mirror. / Here I am in the fields of horsetails, / in the blackberrywith stained fingers. // Here, there’s no wristwatch on a nightstand, / just amind kidding around / someplace unaware it’s unawake. // If I look up at thecanopy now, the day’s / a shredded rag. If I close my eyes, / the light is honeycombed.”There is an intriguing way that Jaeggle works through form through an extensivereading list—examining and echoing form through the masters, as one does—and thepoems offer an array of literary models, from cited poets Denise Levertov and PhyllisWebb to Paul Blackburn and Wang Wei, as well as hints of poets such as JohnNewlove, perhaps. His lines are solid, offering precise rhythms on memory andland, although it is the two-part opening prose poem, “AUTUMN, ACCORDING TO CHILDHOOD,”where the lyric of his line really shines, a sparkle and rush that rise above andbeyond the precise specifics of his line-breaks, as the first poem opens: “Yourmother whispers your name, draws your eyes away from the / loon threadingwater, tight stitch. Look, she says. Look: there’s a deer / chewing dandelion,right here in the yard. Knees bending, she slowly / breaks distance.” Eitherway, there are some stunning moments and movements across Jaeggle’s WrackLine; I am very curious to see where he might go next.

I’veknown his name for a while now (through seeing copies of his three published chapbooks),so was curious to see a copy of

Wrack Line

(Regina SK: University ofRegina Press, 2023), the full-length debut by Vancouver-born Buffalo, New York poet M.W. Jaeggle. Wrack Line is a collection of carved lyrics exploringand examining form, from prose blocks to sonnets to more open forms of thelyric. Jaeggle works through first-person lyric narratives to articulate grief,loss and distraction, writing out the distances and the distances between, asthe piece “POEM BY FRIDGE LIGHT” offers: “Here I am in the culvert where wefound a car’s die mirror. / Here I am in the fields of horsetails, / in the blackberrywith stained fingers. // Here, there’s no wristwatch on a nightstand, / just amind kidding around / someplace unaware it’s unawake. // If I look up at thecanopy now, the day’s / a shredded rag. If I close my eyes, / the light is honeycombed.”There is an intriguing way that Jaeggle works through form through an extensivereading list—examining and echoing form through the masters, as one does—and thepoems offer an array of literary models, from cited poets Denise Levertov and PhyllisWebb to Paul Blackburn and Wang Wei, as well as hints of poets such as JohnNewlove, perhaps. His lines are solid, offering precise rhythms on memory andland, although it is the two-part opening prose poem, “AUTUMN, ACCORDING TO CHILDHOOD,”where the lyric of his line really shines, a sparkle and rush that rise above andbeyond the precise specifics of his line-breaks, as the first poem opens: “Yourmother whispers your name, draws your eyes away from the / loon threadingwater, tight stitch. Look, she says. Look: there’s a deer / chewing dandelion,right here in the yard. Knees bending, she slowly / breaks distance.” Eitherway, there are some stunning moments and movements across Jaeggle’s WrackLine; I am very curious to see where he might go next.

POEM IN THE MANNER OF WANGWEI

Each time on awell-marked and auspicious day, waiting,

a metic again in some newplace,

the thought of yououtside the terminal sharpens,

a narrow band of silveron a lake come midnight,

then, far away, there atthe baggage carousel,

hawthorn beside fir andcottonwood, you short person you.

February 6, 2024

Barbara Tran, Precedented Parroting

Imaginary Menagerie

In the end it was

as in the beginning No one

learned anything What was alive

was killed and stuffed

put on display The remaining live

wandered around amongstthe dead

wondering what they lookedlike

when they were alive andin the positions

in which they were nowposed which the live

could have witnessed inlife

had they not killed

the now

dead

Thefull-length poetry debut by Barbara Tran, author of the chapbook

In theMynah Bird’s Own Words

, winner of the inaugural Tupelo Press chapbook award,is

Precedented Parroting

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2023), publishedas part of Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther Books imprint. I’m fascinated by the threadsand fractures of Tran’s first-person expositions, a lyric composed through arhythm simultaneously layered with both the breathless stretch and the thoughtfulpause. “Pregnant my mother carried apacket of salt,” she writes, as part of the extended, staggered lyric of “Một: Rooted,” “wherever she went InChurch she would lick / a finger then press it to the fine white grains // Wasshe remembering her father and / a life lived according to the tides The sharp/ bite of salt on the tip of her tongue Was hers // the pure, sea salt sadnessof the outcast?” The rhythms here are layered, propulsive and fragmented:thoughts that don’t require beyond the clipped phrase to be fully formed. Tranwrites of home, being and belonging through numbered six sections of poems thatstretch across familial connection, first-person observation, memory andanti-Asian violence, providing layered fragments of observational lyric thatmanage great distances across form and structure. Moving between blocks ofprose lyric to more open structures, longer sequences and hybrid stretches,Tran writes of familial loss in ways heartfelt, graceful and precise, even as,as she writes as part of the extended “Interlude”: “in measured layers, offeringfacts but withholding / crucial details, repeating certain phrasings, teasing /with ambiguous wording.” There is incredible power in this collection, thisdebut, as subtlely held as it is immense.

Thefull-length poetry debut by Barbara Tran, author of the chapbook

In theMynah Bird’s Own Words

, winner of the inaugural Tupelo Press chapbook award,is

Precedented Parroting

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2023), publishedas part of Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther Books imprint. I’m fascinated by the threadsand fractures of Tran’s first-person expositions, a lyric composed through arhythm simultaneously layered with both the breathless stretch and the thoughtfulpause. “Pregnant my mother carried apacket of salt,” she writes, as part of the extended, staggered lyric of “Một: Rooted,” “wherever she went InChurch she would lick / a finger then press it to the fine white grains // Wasshe remembering her father and / a life lived according to the tides The sharp/ bite of salt on the tip of her tongue Was hers // the pure, sea salt sadnessof the outcast?” The rhythms here are layered, propulsive and fragmented:thoughts that don’t require beyond the clipped phrase to be fully formed. Tranwrites of home, being and belonging through numbered six sections of poems thatstretch across familial connection, first-person observation, memory andanti-Asian violence, providing layered fragments of observational lyric thatmanage great distances across form and structure. Moving between blocks ofprose lyric to more open structures, longer sequences and hybrid stretches,Tran writes of familial loss in ways heartfelt, graceful and precise, even as,as she writes as part of the extended “Interlude”: “in measured layers, offeringfacts but withholding / crucial details, repeating certain phrasings, teasing /with ambiguous wording.” There is incredible power in this collection, thisdebut, as subtlely held as it is immense.February 5, 2024

new from above/ground press : Caporaso, Fagan, BLUNT RESEARCH GROUP, Barwin, Unsworth + Touch the Donkey #40

Wars, by Angela Caporaso

$5 ;

Fifty-Two Lines About Henry, by Cary Fagan

$5 ;

The Pig’s Valise, by BLUNT RESEARCH GROUP

$5 ;

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #40

featuring new poems by Ryan Eckes, Dennis Cooley, Michael Harman, Terri Witek and Laynie Browne $7 ;

MY STRUGGLE WITH NOUNS, by Gary Barwin

$5 ;

These Steady Bulbs, by Lydia Unsworth

$5 ;

Wars, by Angela Caporaso

$5 ;

Fifty-Two Lines About Henry, by Cary Fagan

$5 ;

The Pig’s Valise, by BLUNT RESEARCH GROUP

$5 ;

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #40

featuring new poems by Ryan Eckes, Dennis Cooley, Michael Harman, Terri Witek and Laynie Browne $7 ;

MY STRUGGLE WITH NOUNS, by Gary Barwin

$5 ;

These Steady Bulbs, by Lydia Unsworth

$5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material ; see the previous batch of backlist from November-December 2023 here;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

January-February 2024

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

and there's still time to subscribe for 2024! (easily backdated,

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

Forthcoming chapbooks by Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Sacha Archer, Dale Tracy, Melissa Eleftherion, Kyle Flemmer, Saba Pakdel, Katie Ebbitt, Russell Carisse, Micah Ballard, Amanda Deutch, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Peter Myers, Terri Witek, Pete Smith and Clint Burnham (among others, most likely); what else might 2024 bring?

February 4, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with S. Fey

S. Fey

(they/he) is a Trans writer living in LA. Currently, they are the poetry editor at

Hooligan Magazine

, and co-creative director at Rock Pocket Productions. Their debut poetry collection,

decompose

, is out with Not a Cult Media. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Poet Lore, The Sonora Review, and others. They love to beat their friends at Mario Party. Find them online @sfeycreates.

S. Fey

(they/he) is a Trans writer living in LA. Currently, they are the poetry editor at

Hooligan Magazine

, and co-creative director at Rock Pocket Productions. Their debut poetry collection,

decompose

, is out with Not a Cult Media. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Poet Lore, The Sonora Review, and others. They love to beat their friends at Mario Party. Find them online @sfeycreates.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

decompose isn't officially out yet for a few months, so I think I haven't fully processed how it has changed my life, just yet. For now, I'll say that I finally have an answer for the question: "When will you have a book out and when can I get my hands on it?" I used to get this all the time after readings, and now, I can officially say: SOON.

Dr. Taylor Byas and I talk about this often. The new work feels sharper, and more elegant. Its light has changed hue. There is a luster the older poems have that I still admire, and the new poems have their own confidence and vigor that I can't help but respect!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was very young I started keeping a journal, I believe in first or second grade. Those journal entries had line breaks in them, before I even knew what they were. I think poetry has always been the most natural genre for me. I started poetry and fiction at the same time, actually. I think the rhythm of life has moved me to publish more poetry first, however I do publish both nonfiction and fiction, too. They are all important to me, equally.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

decompose, in particular, took about a decade. I started it around 18 years old. It depends on the project, but also, I think this book might prove to take longer than most of the books I'll write in the future. Now that I've done it once, it is a little less daunting. I have a good chunk of poetry book two and I am part of the way into a nonfiction project. I would say all of the above, in terms of quick or slow process, and first drafts being close or distant to their final form. It ranges from poem to poem. There are the poems that come out "ready to run" to quote our Poet Laureate, Ada Limón in her poem "What I Didn’t Know Before" and then there are poems that take dozens of drafts to chisel into their shape.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I go from poem to poem, and I'd say the pieces combine into a larger work in time. My second book came to me as a concept much more quickly than the first, but even then, the concept could change. I usually don't work on a book from the beginning, but with this second book I've sort of kept the framework in mind as I write. I don't expect everything I write to fit, but it's good to know there's a home waiting if it does.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy doing readings. It's a cool part of the process, to engage with an audience of readers and listeners in real time. I am often very inspired at readings and have written many a poem while attending a reading.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

think this changes from poem to poem, but right now I'm writing a lot about childhood and philosophy. Each poem has its own questions, and I'm not sure if they are ever really answered. The kind of work I want to write is meant to bring awareness and leave you with more questions than you started with. If I leave a reader thinking and asking questions, I'm happy.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I'm going to give you the classic playwright answer: to hold a mirror up to the world. There is an absolute necessity to storytellers in society, as stories are how a lot of us survive. For me, writing has kept me alive and been the light that guided me through times where I didn't think I would make it out alive. Through storytelling, I hope to make people feel seen.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Absolutely essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Javier Zamora told me: Remember, the book is not you. However successful the book is, it isn't a reflection of who you are as a person. People's opinions of it are not their opinion of you. It's going to go out there and live its own life, have its own journey.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every day, whether it be a poem, part of an essay, short story, script, etc. I have a full time job, so on my lunch break and after work I write. I read every morning and evening. 5-10 poems in the morning, 5-10 in the evening. Usually that amounts to 1-2 collections of poems a week. I typically like to read poems in the morning, nonfiction during the day, and fiction in the evening. Generally I'm reading one book of each genre. Right now I'm reading a lot of craft books and memoirs.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I go for a walk or read. I see a lot of films too, and this inspires me immensely. Sometimes, if I need to take the pressure off, I go play video games or pool.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Coffee in cold weather.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Film, visual art (I love museums), and video games, for sure. I also have playlists for each book.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I really could go on and on and on, but to add just a fraction of the writers who move me: Dr. Taylor Byas, Javier Zamora, Dia Roth, Dare Williams, Susan Nguyen, Danez Smith, Shira Erlichman, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Diane Seuss, Richard Siken, Jason B. Crawford, Rita Mookerjee, Jo Cipriano Zamora, Anne Carson, Carl Phillips, Khadijah Queen, Michelle Tea, Gem Arbogast, Amelia Ada, Austen Leah Rose, Erin Marie Lynch, Meg Kim, Erin Mizrahi, Chen Chen, Sarah Ghazal Ali, Megan Fernandes, Ariana Benson, and Rhiannon McGavin to name a few.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Be in a TV writers' room.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

When I was a kid I wanted to be a director, which is what I do besides writing. If I had to do any other occupation full time, that's where I'd be. Technically, my degree is in directing and playwriting.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I must.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Black Pastoral by Ariana Benson and Poor Things .

19 - What are you currently working on?

A nonfiction project and a TV pilot. <3

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

February 3, 2024

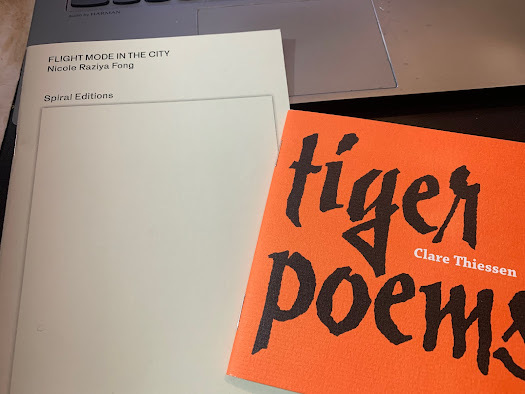

Ongoing notes: early February, 2024: Clare Thiessen + Nicole Raziya Fong,

We’re half-way through our big VERSeFest fundraiser, with an array of amazing perks still available!

And keep an eye out on an announcement of our upcoming (shorter) spring festival (with most likely a further short burst of events inthe fall, before, hopefully, returning to a full-size festival in spring 2025).And did you see that the dates for both 2024 editions of the ottawa small press book fair have been announced?

We’re half-way through our big VERSeFest fundraiser, with an array of amazing perks still available!

And keep an eye out on an announcement of our upcoming (shorter) spring festival (with most likely a further short burst of events inthe fall, before, hopefully, returning to a full-size festival in spring 2025).And did you see that the dates for both 2024 editions of the ottawa small press book fair have been announced?Wolfville NS/Vernon BC: It has been a whilesince Gaspereau Press sent me any chapbooks, so the only ones I’ve beenencountering are the ones passed along by authors, and Vernon, British Columbia poet Clare Thiessen recently sent along her tiger poems (GaspereauPress, 2023), a collection of short, sharp prose poems on, as you might alreadyhave guessed, tigers. I am intrigued by the cadence, the structure, of theseprose poems, offering each line/phrase as a kind of burst that accumulate and layerinto a kind of portrait or scene; how different might these pieces be if herlines were shifted between poems, or in a different order? “you world begins toshrink based on the tiger’s potential / whereabouts,” she writes, to open thepoem “eyes peeled,” “you learn from your older brother he goes to this / gas station you learn from a friend that he frequentsthe cafe / near her work you haveheard me may be living on a road that / you now avoid [.]” There is someintriguing movement in these poems, and I would very much like to see more ofher work.

only belly-height

no one sets up a cage forthe tiger even after they have

inklings even after worries even after proof and admis-

sion instead cardboard boxes are set up aroundthe tiger with

little gates if he should so choose to wander around the

cardboard is insufficientthey realize eventually so perhaps

a white picket fenceinstead it stretches up to the tiger’s

belly looks quite clean from the inside

“Kansas”/Tiohti:áke/Mooniyang/Montreal QC: The latest I’veseen from poet Nicole Raziya Fong is the chapbook FLIGHT MODE IN THE CITY (SpiralEditions, 2023), a numbered edition of one hundred and twenty-five copiesproduced by Ryan Skrabalak’s Spiral Editions down there in Kansas. Utilizing sidebars,alternate-sized and overlapping fonts, font-size, text and split narratives,Fong’s poem utilizes a kind of process-text: not incomplete but in a kind ofmotion. In this chapbook-length poem, they offer a lively notation of lyric andsketched-out thought, response and revision. How does a poem hold such obviousmovement? This is very much a poem in motion set on the page, which is not an easyconsideration to achieve.

February 2, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Judith Pond

Judith Pond

[photo credit: Gerald Mills] has published fiction and poetry in a widevariety of literary journals. She is the author of four poetry collections,including

A Shape of Breath

.

The Signs of No

is her debut novel.

Judith Pond

[photo credit: Gerald Mills] has published fiction and poetry in a widevariety of literary journals. She is the author of four poetry collections,including

A Shape of Breath

.

The Signs of No

is her debut novel.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book was published a very long time ago.I guess the main way it changed my life was that it astonished me by getting published.I remember thinking, Now I can be as eccentric as I want! I guess I assumed orhoped that all writers were weird like me. In more a more serious sense, myfirst book was poetry, as were my subsequent three, and coming to prose throughpoetry was for me the best way to learn my craft, as poetry is all aboutrhythm, subtlety, word play, and economy, which are fantastic tools for prosewriting.

There’s not a lot of comparison between mycurrent writing (novel form) and my previous work other than the economy that Ilearned as a poet. I am very glad that I trained in that form.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry ornon-fiction?

I started out attempting to write short stories,and then turned to poetry, I think because I fell in love with someone Iprobably shouldn’t have. Nothing like stolen love to make a person write poems.I never expected to be a novel writer, but at some point it seemed like a goodthing to attempt a longer project.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I think that a writing project is sort of alreadythere, and then when the time is right, starts nudging me to get at it. Theyseem to line up like airplanes waiting to take off. For me, writing is a slowprocess because I’m a perfectionist and a bit of a coward. The next sentence isholy terror for me. So I dawdle and polish. Drafts appear looking polished butit’s only because I want them to be done, and they never are. Three drafts is aminimum for me. I don’t take notes very much. It’s more a kind of groping, andI let the words lead to some extent. I don’t outline, which (outlining) seems abit artificial, and ultimately not very useful. I’m more organic at it, ormaybe stubborn, and that can get me in trouble. Thank God for my tiny writers’group of three. Those other two guys have no trouble pointing out where I’m offthe rails.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me a poem comes from an image that I buildwords around. With a novel, I assume that’s what it is (a novel) from the verybeginning.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I haven’t done a reading for a good while, andthey do stress me a bit, but I have a background in teaching, and that helps.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I confess that I don’t care much about currentquestions, though of course they find their way into my work. For example, I’ma big ally of trans and queer people, having a child who has transitioned, andthat process definitely informed The Signs of No. Other than the ‘current’things I happen to bump into, if I have theoretical concerns, they’re mainly aroundnot hurting other people. The question I’m trying to answer in my currentproject is about how far it is possible to go in the service of love (filial,erotic, parental, patriotic, etc.). To what extremity in other words, is itpossible to push a situation or a conviction in that service, however onedefines it.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture?Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I know it’s been said, but I still think that thewriter’s role is in some sense to show us ourselves. To show us the worldthrough a particular lens: love, for example, or duration, or loss.

I haven’t done much work with an editor, but Ihave found it both essential and illuminating to work with an outside editor.No way can I see everything I need to see about what I’ve put on paper. I lovebeing shown what a scene, for example, could be, if pushed a little farther,thanks to an intelligent reader’s POV.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given toyou directly)?

Richard Ford said in an interview that youshouldn’t think that all you’re going to have to do in a rewrite is ‘go throughand change the pronouns.’ He says that you are going to rip and tear andrummage in a draft (I now call that nice, pretty, seemingly-all-finished draftmy ‘grab bag’) and keep only what you can use. He says it isn’tnecessarily going to be the same book at all, once you’re done with it, andthat comment has given me more courage and freedom than pretty much any otheradvice I’ve received. You don’t just write The End and think you’re done.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to shortstories)? What do you see as the appeal?

Short stories from poetry wasn’t too bad, butnovel from short stories has been quite a jump, and yet I am finding it suitsme as a form. I like that big oversized messy overcoat that I can button up andkeep warm in( if I’m lucky) for a goodlong while. Like other writers I’vefollowed, I find that I’m quite lost when a big project is over.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even haveone? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write every day, though not in set hours. Ikind of live writing, so it’s always on my mind. On weekdays and Sundays I swimfirst thing in the morning (I do a lot of prewriting in the pool), and thenbrew up the coffee and get going. I don’t always get a lot done in a day but ifI have some significant contact—even if it’s just deciding that a scene shouldbe moved and where I could put it—with my work in a day, I’m happy.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

I read people I admire for inspiration.Invariably I come away thinking, I’m going to try that! I don’t get stalled alot. I can’t tolerate it. I never (unless something’s really wrong) let myselfup from the desk until I feel like I’ve pushed the work to a place it’s notscary to start up from the next day.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I guess it depends which home. Nova Scotia wouldbe the air, I guess. It’s lush and soft and shocking when you get off theplane. Calgary is my husband’s housecleaning products. ;)

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are thereany other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science orvisual art?

I totally agree about books coming from books,but I love dance, and I do find strong inspiration in visual art. Among otherthings, I studied Art History, and I worked for a decade in a university ArtHistory department categorizing and filing images; that work gave me my firstcollection of poems, and still informs my work constantly.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simplyyour life outside of your work?

I once had a therapist accuse me of ‘being inlove with a dead woman’ (Virginia Woolf). I devoured every word by and abouther and about the Bloomsbury group when I was young, and Woolf still gives me wondrousshivers. She taught me how to write letters that are daring and fun anddefamiliarized, for example—or at least to enjoy trying. To mention Ford again,though I don’t write like him at all and couldn’t, he is a major ‘lamp unto myfeet,’ to quote another great book. I’m reading Atwood again right now after along hiatus (Old Babes in the Wood) and really loving it. I’m glad I wasearly exposed to the Bible, and should mention that, since I see I’veinadvertently referenced it above. I can’t think of a better preparation for awriting career than a foundation in the King James Version and an education inArt History. Other than those books, I’m in Mexico right now, and I can’t stopthinking about Under the Volcano (Malcolm Lowry).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to dance more. By that I mean learnmore kinds of dance. And I would like to be friends with a horse.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

If I hadn’t been a writer, I think I’d have donea PhD and been a prof somewhere. I’d have liked that, maybe. The other thingwould be that I would have loved to have been a singin’ chick in a band.I’m pretty wistful about that.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Life is infinitely puzzling to me. I write tofigure stuff out.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just finished The Sportswriter for thesecond time. I’ll never know how Ford achieves so much with so muchunderstatement and apparent humility and gentle anarchy. As for films, I reallyenjoyed Saltburn. Great acting, beautiful cinematography, gorgeouslycreepy.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Right now, I’m about to start edits on acollection of linked stories that will come out in the fall of ‘25 withFreehand Press of Calgary, and I’m working on a next novel. What I want toexplore, as touched on above, is how far a person might be willing to ‘go’ inthe service of what they perceive to be love. A secondary thread in that novelwill be (I think so far) a consideration of the ways in which our originalwoundings operate subliminally and significantly in our lives.

February 1, 2024

SLIPSHEETS: created and introduced by Andrew Steeves, with an afterword by Christopher Patton

I’mfascinated by the recent SLIPSHEETS (Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press,2023), the full title of which seems to be (offering a bit more of adescription to the project) AN INCIDENTAL PRINTING OF GERARD MANLEY HOPKIN’S“PIED BEAUTY” ON SLIPSHEETS, CREATED & INTRODUCED BY Andrew Steeves, WITHAN AFTERWORD BY Christopher Patton. As Gaspereau Pressco-founder/publisher/printer Andrew Steeves writes in his introduction, “Readingthe Sheets in the Printer’s Trash Bin,” this is a project that emerged out ofprinting an edition of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ sonnet “Pied Beauty” in the spring of 2021, requiring extra sheets between printed sheets for the sake of reducingunintentional ink transfer during the printing process. As he writes:

In order toget the large type as black as possible, I printed the book on dampenedmouldmade paper using frightening quantities of ink. This tactic worked finewhen printing the front of each sheet, but printing the back side posed somechallenges. When the back side of a dampened sheet of paper is printed (‘backedup’), some of the still-tacky ink from the front side—which is now flipped overand making direct contact with the press’s impression cylinder—inevitably transfersonto the impression cylinder wherever the type from both the front and the backsides overlap on the sheet. Over the length of a press run, the transferred ink(the ‘offset’) builds up on the cylinder’s drawsheet and causes problems; thisoffsetting must be either kept to a minimum or cleaned off. Rather than wipingthe offset ink from the drawsheet after every impression, I decided to slip aclean sheet of cheap paper under each press sheet as I printed. These slipsheetsreceived the offsetting ink and kept the cylinder clean.

And so every stack of book sheets that I printed for myedition of “Pied Beauty” also produced a corresponding stack of soiledslipsheets carrying the bizarre rendering of the text that occurred whereverthe pressure from the back side of the form overlapped with the wet ink fromthe front side. What interests me about these slipsheets is how the imagerythey capture is an incidental expression of the poem, but not a random one. Theyare the inevitable outcome of a controlled and intentional technical process, agraphic expression of the poem refracted through the act of printing andrecorded in the project’s waste.

Thereis something fascinating about how the play with printing machinery offers ameeting point between the work of someone such as Andrew Steeves, anexperienced printer, critic, poet and editor, and the work of someone such asthe late Toronto poet bpNichol (1944-1988), who also engaged with learning howto work the presses at Coach House, often composing pieces towards what couldor shouldn’t be possible utilizing alternate printing methods. The result of Steeves’play with SLIPSHEETS has the effect of being an echo, or even a blend,of visual poetry elements utilized by visual poets such as Nichol, David Aylward,Gary Barwin and Derek Beaulieu (among multiple others, even such as ChristopherPatton, as well) and even the text-work of the late London, Ontario artist Greg Curnoe (1936-1992), playing with block text in a large format, but allowing forthe accident to see what else might be possible. It is always fascinating tosee printers play with the equipment, allowing themselves these quirky side-projectsof accident. And, whereas Steeves’ introduction offers an explanation ofprocess, ie: how we got there from here, as well as an overleaf of the printer’simposition scheme mapped “for those curious about this aspect of the process,”poet and critic Christopher Patton’s afterword, “Beauty of the Antiphon,”explores the result of these accidents, this project. As Patton writes: “Icannot shake the feeling Hopkins anticipated this setting of his poem. If notthe man, his dauntless, ecstatic eye.” He echoes the same towards the end ofhis short piece: “I cannot shake the feeling Hopkins anticipated this settingof his poem. His love for play among semblances. The antiphonal form of histhinking.” How does accident, such “waste” (as the back cover calls it) become thefocus of such an intriguing, playful translation of a poem? As Patton writes,mid-point through his piece:

These sheets are a fortuitous translation, made for the typographicaleye, of the test he called “Pied Beauty.” They meet letterforms as he metnatural forms: attuned to their selving and their interfusion andthe non-difference of the two. (Shitou Xiqian described it as “two arrowsmeeting in mid-air.”) That they are disjecta of a printing process bent on someother product lessens them not at all. As Hopkins wrote of his own self-being,his being-in-Christ, this “joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortaldiamond, / Is immortal diamond.” Note the two turns: one on the comma after “matchwood,”one on the virgule marking the moment the verse reverses.

January 31, 2024

David Melnick, Nice: Collected Poems, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman

I found Melnick’s work after moving to Berkeley, where helived in the late 1960s and early ‘70s before moving across the Bay to San Francisco.I had heard tell of his readings of PCOET—his “correct” pronunciations, howonly a few could remember the exact sounds his private language formed. I hadheard of his famous Homer Group, and read how Melnick’s voice was infectiousamong the other “Homersexuals,” how his homophonics perversely instigated akind of Bacchic frenzy. I remember being shown an event flyer from 1974, fromthe now-defunct Cody’s Books, featuring Melnick reading with Telegraph’s “BubbleLady,” Julia Vinograd. I would walk past the former Cody’s building daily tofeel their presences decades after.

Melnick’s workcreated a kind of orbit, tugging me to its center, but the force that propelledmy obsession was impossible to see. Was it that Melnick gave language to queerfeelings I had known somewhere deep inside me, but had been unable to voice?Was it that his work points to a kind of unspeakability of these very “qqrer!”feelings? I am left wondering what kinds of queer feelings we can represent inqueer (il)legibilities. Whether Melnick offers us a cipher, a code, a means ofreckoning with language and its limits, feelings and the limits of representingthose feelings, too. (Noah Ross, “(POETS; EXIST?”)

Ihadn’t even heard of San Francisco poet David Melnick (1938-2022) before thisnew collection landed in my mailbox—

Nice: Collected Poems

, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman (New York NY:Nightboat Books, 2023)—a book that includes preface on the author by poet and critic Noah Ross [see my ’12 or 20 questions’ with him here; see my review of his second collection here], and a collaborative introduction-proper by thefour editors. I’m fascinated by these seeming-reclamation projects that Americanpublisher Nightboat Books has been publishing over the past decade or so(possibly longer, but I’ve only been aware of their work for the past dozen-plusyears), all of which swirl around particular writers and writings, allowing documentationfor a wealth of literary activity, specifically: by, about and through queerwriters and writing. Some of the collections I’ve been particularly impressedby include their

Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader

, edited byJamie Townsend with an afterword by Alysia Abbott (2019) [see my review of such here],

We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics

, eds.Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel (2020) [see my review of such here] and

WritersWho Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

, eds. Dodie Bellamy and KevinKillian (2017) [see my review of such here]. I’d probably also include thecollection

On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays

(2022) by American poetand critic Douglas Crase [see my review of such here] to this list as well. Thereis something to be acknowledged and appreciated in Nightboat’s ongoingattentions to providing critical consideration, examination and celebration tothese histories that might otherwise have been overlooked, misunderstood oreven completely forgotten. As the first poem of Melnick’s posthumous collection,the five-page “I. LE CALME,” ends:

Ihadn’t even heard of San Francisco poet David Melnick (1938-2022) before thisnew collection landed in my mailbox—

Nice: Collected Poems

, eds. Alison Fraser, Benjamin Friedlander, Jeffrey Jullich & Ron Silliman (New York NY:Nightboat Books, 2023)—a book that includes preface on the author by poet and critic Noah Ross [see my ’12 or 20 questions’ with him here; see my review of his second collection here], and a collaborative introduction-proper by thefour editors. I’m fascinated by these seeming-reclamation projects that Americanpublisher Nightboat Books has been publishing over the past decade or so(possibly longer, but I’ve only been aware of their work for the past dozen-plusyears), all of which swirl around particular writers and writings, allowing documentationfor a wealth of literary activity, specifically: by, about and through queerwriters and writing. Some of the collections I’ve been particularly impressedby include their

Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader

, edited byJamie Townsend with an afterword by Alysia Abbott (2019) [see my review of such here],

We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics

, eds.Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel (2020) [see my review of such here] and

WritersWho Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

, eds. Dodie Bellamy and KevinKillian (2017) [see my review of such here]. I’d probably also include thecollection

On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays

(2022) by American poetand critic Douglas Crase [see my review of such here] to this list as well. Thereis something to be acknowledged and appreciated in Nightboat’s ongoingattentions to providing critical consideration, examination and celebration tothese histories that might otherwise have been overlooked, misunderstood oreven completely forgotten. As the first poem of Melnick’s posthumous collection,the five-page “I. LE CALME,” ends:These languages passaway:

:fellatio, ofsubjection

now kings are dead

becausethe head is lowered

“eyes ripe asolives

“a green seaknobby

bit by worms

stirred, in

the main stream

“bee keeperseized the earth

“size of a star

Walking, sorrowslew me

Nice: Collected Poems collects four previously-publishedlimited-edition works by Melnick across nearly fifty years of scattered production:Eclogs (Ithica House, 1973), PCOET (G.A.W.K., 1975), Men inAïda (Tuumba Press, 1983) and A Pin’s Fee (Logopoeia website, 2002;Hiding Press, 2019). There’s a liveliness to this work, one that sweeps unapologeticallyinto experimentation and the playfully-ridiculous, a quality that is quiterefreshing; the earlier works clearly showcase a poet of his period, employinga particular flavour of 1960s and 70s experimentation, but somehow timeless,offering an expansive play across meaning, sound and the lyric through apoetics of subverted and invented language. It would be impossible not to be simultaneouslycharged and charmed by the expansive heft of the poem “Men in Aïda,” a homophonictranslation of the Iliad, a piece that can’t not be heard aloud, evenfrom within the bounds of quiet reading. The language really is propulsive, andmy ears can catch comparisons with language/sound poets north of the border,from bpNichol and Christian Bök to The Four Horsemen, Gary Barwin and Gregory Betts (among others). Such glorious gymnastics of sound! As Melnick’s poem begins:

Men in Aïda, they appeal,eh? a day, O Achilles!

Allow men in, everyAchaians. All gay ethic, eh?

Paul asked if tea moussesuck, as Aïda, pro, yaps in.

Here on a Tuesday. ‘Hello,’Rhea to cake Eunice in.

‘Hojo’ noisy tap ashideous debt to lay at a bully.

Ex you, day. tap wrote a ‘D,’a stay. Tenor is Sunday.

Arreides stain axe andRon and ideas ‘ll kill you.

Movingthrough the material, I’m simultaneously surprised and not that I hadn’t heardof this poet before this book landed, making me wonder just how much materialexists in the world by those otherwise-forgotten writers? We move so quickly tothe next book and the next book that there are probably dozens of poets leftbehind: “only alive as long as in print,” to paraphrase a line by the (since late)Canadian poet Patrick Lane. So much literary history is unrecorded andoverlooked, and this is a wonderfully vibrant collection, even through the darkelements of Melnick’s later work, as the collaborative “INTRODUCTION” writes:

In parallel with hislife, Melnick’s poetry also yields story, a compact one. Four books comprise his legacy: Eclogs (written1967-1970), PCOET (mostly 1972), Men in Aïda (1983), and A Pin’sFee (1987). As the dates of composition show, his years of creativity spana crucial two decades in the rise of queer community: his first book begunbefore Stonewall; his last written in the crisis years of AIDS. And each bookreflects a truth of its moment, though in a manner entirely its own. In Eclogs,the beautiful façade of coded language preserves an experience it screens fromview. PCOET yields to the joy of invention, creating a language all its own. Menin Aïda, the pinnacle of this span, is his epic: an act of gayworldbuilding, embracing the past and transforming it through homophonic translation.A Pin’s Fee, the shortest of the four, is anguished: its last word, “DEATH, “repeating forty-five times. After this, nothing. For the rest of Melnick’slife, another thirty-five years, no other poetry would surface.

January 30, 2024

Maxine Chernoff, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems

3.

Roll over, Oscar Wilde. MeetGertrude Stein

and the Little Sparrow. MeetJim Morrison and

Chopin too. Deeper and deeperour travels

took us: there wasCreate, whose indoor toilets

were the first preserved.The tourists

from the cruise had sealegs, as Knossos listed

right or left. TheMexican economist hated

America’s presumptions,he confessed at dinner,

before the ping pong balldisappeared into the Aegean.

I thought Ship ofFools, how doomed

our journeys, feltcomfort in moss roses curled

around a railing wheremen worked sums.

The castle from the Crusades,rehabbed by Mussolini:

palimpsest of wrongideas: and no plot to save us. (“Zonal”)

Iwas curious to see a copy of Mill Valley, California poet and editor Maxine Chernoff’s latest, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems (Cheshire MA:MadHat Press, 2023), a collection that selects poems across six of her nineteenbooks of poetry— (Apogee Press, 2005),

The Turning

(Apogee Press, 2007) [see my review of such here],

To Be Read in the Dark

(Omnidawn, 2011),

Without

(Shearsman Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Here

(Counterpath Press, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Camera(Subito Press, 2017) [see my review of such here]—as well as a healthy openingsection of new poems. Focusing on her work with and through sonnets, sequences,extended lines and other lyric structures, Light and Clay exists as a counterpointto her

Under the Music: Collected Prose Poems

(MadHat Press, 2019) [see my review of such here], andthe two collections paired offer an interesting overview of Chernoff’sattention to poetic structure. “Love’s tender mercies clear the air,” shewrites, to open the poem “Traced,” “Unhinging the gate to practiced longing. /Tied to life, you spill into water, deeper / Than any atmosphere.” Chernoff’spoems extend lines of thought across great distances, whether the line, thepoem or as a sequence of pulled-apart sentences, offering a lyric that works toarticulate and examine intellectual and physical space. Hers is a lyric,essentially, of seeing, and what she sees is illuminating. As the short poem “Granted”ends: “We stayed in bed for years / and took our cures patiently / from eachother’s cups. / We read Bleak House and / stored our money in socks. /Nothing opened as we did.”

Iwas curious to see a copy of Mill Valley, California poet and editor Maxine Chernoff’s latest, Light and Clay: New and Selected Poems (Cheshire MA:MadHat Press, 2023), a collection that selects poems across six of her nineteenbooks of poetry— (Apogee Press, 2005),

The Turning

(Apogee Press, 2007) [see my review of such here],

To Be Read in the Dark

(Omnidawn, 2011),

Without

(Shearsman Books, 2012) [see my review of such here],

Here

(Counterpath Press, 2014) [see my review of such here] and Camera(Subito Press, 2017) [see my review of such here]—as well as a healthy openingsection of new poems. Focusing on her work with and through sonnets, sequences,extended lines and other lyric structures, Light and Clay exists as a counterpointto her

Under the Music: Collected Prose Poems

(MadHat Press, 2019) [see my review of such here], andthe two collections paired offer an interesting overview of Chernoff’sattention to poetic structure. “Love’s tender mercies clear the air,” shewrites, to open the poem “Traced,” “Unhinging the gate to practiced longing. /Tied to life, you spill into water, deeper / Than any atmosphere.” Chernoff’spoems extend lines of thought across great distances, whether the line, thepoem or as a sequence of pulled-apart sentences, offering a lyric that works toarticulate and examine intellectual and physical space. Hers is a lyric,essentially, of seeing, and what she sees is illuminating. As the short poem “Granted”ends: “We stayed in bed for years / and took our cures patiently / from eachother’s cups. / We read Bleak House and / stored our money in socks. /Nothing opened as we did.”Whereasher prose poem selected opens with an introduction by Robert Archambeau, thiscollection exists without, which, as regular readers of this space are alreadyfully aware, I consider a severe oversight for any selected or collected; it isimportant to place writer and writing within context, and offer why and howthis collection was decided upon, let alone shaped. For example: did the authormake the selections herself? What was the process of these books selected, andselected from, and not others? Either way, opening with the sixteen-part sonnetsequence, “Zonal,” the poems in the “new” section employ an increased complexity(compared to the other poems throughout), providing a layering of image, insight,craft and instability, finely-woven with deceptive ease. The shift across thebody of her work, at least as presented in this two hundred page-plus volume,is intriguing, subtle and even clarifying. This is an incredible work by a severelyunderrated poet, sliding under the radar for more than enough time (a recentfolio on her work did appear recently in Denver Quarterly, Vol 57 No. 4(2023), edited by Lea Graham, although the issue itself doesn’t seem to belisted anywhere on their website).

You Took the Dare

To live here and there,as recluse

and as host. While everythingexploded

and flames turned waterred, you

suggested a menu and gaveto

a proper cause. Nothing endured

the losses around you,the final note

that sounded past alarm. Acloudy

resemblance of what oncesufficed came

to be known as grace asyou listened

to grass growing, to aboy praying

near the great stonewall. Crisis after

crisis stacked up likeplanes in fog.

You counted moss-coveredbricks near

the former factory,where, at sunset,

brown light flickered.

What else to do but live?