Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 61

February 28, 2024

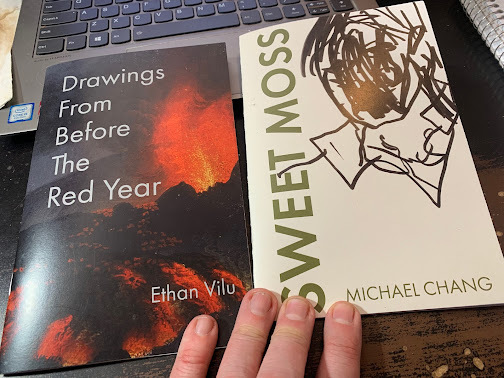

Ongoing notes: late February, 2024 : Michael Chang + Ethan Vilu,

There are only THREE DAYS LEFT in the VERSeFest fundraiser!

But youalready knew that, yes? And the schedule for this spring’s VERSeFest: Ottawa’s International Poetry Festival (March 21-24) will be announced very very soon!

There are only THREE DAYS LEFT in the VERSeFest fundraiser!

But youalready knew that, yes? And the schedule for this spring’s VERSeFest: Ottawa’s International Poetry Festival (March 21-24) will be announced very very soon!Toronto ON/Brooklyn NY: I’ve seen work byAmerican poet and editor Michael Chang around for a while now, so it is good tofinally get my hands on a small collection, the chapbook SWEET MOSS(Anstruther Press, 2024), following collections such as SYNTHETIC JUNGLE(Northwestern University Press, 2023) and EMPLOYEES MUST WASH HANDS(GreenTower Press, 2024). Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther has been leaning intopublishing work by more Americans these days, I’ve noticed, allowing for aparticular kind of cross-border conversation within the bounds of his press,one of the more active chapbook publishers in Canada. The seventeen poems thatmake up SWEET MOSS shift in structure, from prose poems to more traditionalline-breaks, each of which offer accumulations of first-person statements.Chang’s poems write in a kind of propulsion of direct statements, sly commentaryand observation in a language condensed, communicating with the immediacy ofsocial media or text messages. “if the gods are watching,” Chang writes, aspart of the poem “SPECIAL SNOOZE,” “I’m not allowed to be too happy // I’m notsure why I think this / Probably something learned from television [.]” There’san element of Chang’s lyric lined with input from every direction, whether culture,social media, relationships and travel, attempting not only a through-line buta line through. Perhaps, through Michael Chang, one might manage, and evenmaintain, a degree of clarity through all the external noise.

SMOKE IN JAPAN

the man u loved

died in a war

of ur own making

downturned mouth

mess of fallopian tubes

yes but have u heard of

staring in the samedirection

changing NO HOPE FOR US!!!

we’re full

of special moments

that end

in a matter of hrs

a place in nature

we can finally meet

pegged by peggy

hootin’ for hooten

heads in clouds

in flagrante delicto

the battys in the club

peep ur finest garb

seething assured

a hit dog will holler

Toronto ON/Calgary AB: The latest from Calgary poet, reviewer and editor Ethan Vilu, following the longsheet, A Decision Re: Zurich (The Blasted Tree, 2020), is Drawings From Before The Red Year (Anstruther Press, 2024), an assemblage of short narrative scenes witha clipped lyric. Vilu’s poems are lean, and precise, a sketchform of linesenough to see the whole portrait, even the spaces not drawn. Taking theircontent from the online fantasy game series, Elder Scrolls, I’m surprised therearen’t more poems composed across further elements of pop culture (although thelist of those composing poems for superhero comic characters are fairly short,also), specifically online gaming, something Leah MacLean-Evans has beenworking for a while (I’ve been awaiting a chapbook or collection of some time)and Ottawa poet IAN MARTIN, who has been exploring both gaming and programming.“In my skull I hear the clattering of bad fables. Dark signal,” Vilu writes, toopen the poem “Galtis Guvron,” “scrabled scar. Down the stairs, a messenger approaches:// blood on her hands, a translusccent musical name. A siren // siphoning fromthe stars.” Vilu’s poems here are sharp, serious and playful, and one mightwonder if there might be a full-length collection-to-come, perhaps, one thatmight even allow certain readers an entry point into poetry, from online gaming.The opening lines of the poem “Drarayne Girith,” might even serve as a kind ofars poetica for Vilu’s explorations through gaming: “I stop just short. //Clipped writsts, ragged staff, crushed tongue.”

The Docks Outside Vivec

Ambrosial, this seabreeze –

salt, anther pollen andpearl.

Linen and wood

form a necklace to collarthe cove.

straight ahead: theheather patch,

the sigil-stone, thesky-vibrant beach

and the wide bridge,

tense and time-honoured,

carrier of secrets,

working to cast off itsburden.

February 27, 2024

Danielle Vogel, A Library of Light

When we are. When we arethere, we lay together and cover ourselves with our voices. When we are ten, weare also twenty-one. We speak of breathing, but this is a thing we cannot do. Whenwe are seven, we are also eighteen. When we are eighteen, we begin our bodies. Butwe are unmappable, unhinged. A resynchronization of codes, the crystallinefrequencies of stars, seeds, vowels, lying dormant within you. we are theoldest dialect. A sound the voice cannot make but makes.

Thelatest from American “cross-genre writer and interdisciplinary artist” Danielle Vogel, currently an associate professor of English at Wesleyan University, is

A Library of Light

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2024), acollection that follows

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press, 2015),

Edges& Fray

(Wesleyan University Press, 2019) [see my review of such here]and The Way A Line Hallucinates its Own Linearity (Pasadena CA: Red HenPress, 2020) [see my review of such here]. As the press release offers: “Whenpoet Danielle Vogel began writing meditations on the syntax of earthen and astrallight, she had no idea that her mother’s tragic death would eclipse the writingof that book, turning her attention to grief’s syntax and quiet fields ofcellular light in the form of memory. Written in elegant, crystalline prosepoems, A Library of Light is a memoir that begins and ends in anincantatory space, one in which light speaks.” Composed across three extendedsections of prose poem accumulations—“Light,” “of Light” and “Light”—as well asthe “Postscript—Syntax: a bioluminescence,” Vogal examines the shifting of selfand of selves, light and of light, and the simultaneity of all of the above throughthe complexities of grief. This is, as she offers, a book of light. “This fieldis the first inscription.” she writes, early on in the collection. “A cracklingpulse that set me going. I think words like amniotic, birth, origin,beginning.”

Thelatest from American “cross-genre writer and interdisciplinary artist” Danielle Vogel, currently an associate professor of English at Wesleyan University, is

A Library of Light

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2024), acollection that follows

Between Grammars

(Noemi Press, 2015),

Edges& Fray

(Wesleyan University Press, 2019) [see my review of such here]and The Way A Line Hallucinates its Own Linearity (Pasadena CA: Red HenPress, 2020) [see my review of such here]. As the press release offers: “Whenpoet Danielle Vogel began writing meditations on the syntax of earthen and astrallight, she had no idea that her mother’s tragic death would eclipse the writingof that book, turning her attention to grief’s syntax and quiet fields ofcellular light in the form of memory. Written in elegant, crystalline prosepoems, A Library of Light is a memoir that begins and ends in anincantatory space, one in which light speaks.” Composed across three extendedsections of prose poem accumulations—“Light,” “of Light” and “Light”—as well asthe “Postscript—Syntax: a bioluminescence,” Vogal examines the shifting of selfand of selves, light and of light, and the simultaneity of all of the above throughthe complexities of grief. This is, as she offers, a book of light. “This fieldis the first inscription.” she writes, early on in the collection. “A cracklingpulse that set me going. I think words like amniotic, birth, origin,beginning.”A Library of Light exists as bothexamination and archive of memory, loss, dislocation, connection andinterconnection; of light, working through a translation of how light acts, andreacts. “Sometimes, when asked what I’m working on,” she writes, as part of thesecond section, “I tell people I’m writing a translation of light. Light, likethe memory of a color, of a sound that we can’t quite sense, but is there,nonetheless. Inherited light. cellular light. Interstellar. Memories that havealready happened to someone or somewhere else.” Whereas Ottawa-area poet Robert Hogg worked his lyric as a sequence of extended stretches that utilized aparticular lightness of tone and touch in his Of Light (Toronto ON:Coach House Press, 1978), Vogel utilizes that same element of light but onethat acknowledges its lightness, as well as its weight (or mass), the gravityof each section shifting like sand, until certain might sit lighter than air, andothers, almost too heavy to bear. As she writes:

Light lets the grid of athing respire. Each intersection becomes an or in relation. Imagine theskin of you, all its points of convergence, either through sense or sound,being met at once. The grid begins to glow.

We move in everydirection even standing still. We are let by light. It culls something againstus. The grid is refracting. Light oracles us. Languages us. Reflexes relation. Ibecome beside myself and something else while stationary.

,

As language contracts, I experiencemy form. Its skin, sensors and bones, its joins and synapses. Language iserotic, sensory. Atmospheric and physical. The living bridge between the two.

,

Ilike how Vogel holds commas to separate her sections, furthering the suggestionof accumulation and ongoingness to the sequence of prose pieces. One step, andthen another, progressing throughout the length and breadth of the collection. Thepieces, poems, in A Library of Light are deeply thoughtful, lyricallycompact and meditative, working her light through the dark, a call-and-responsebetween the two, each one threading the other’s needle. Vogel holds whatotherwise can’t easily be held. There is such an ongoingness to grief, thegrief described here, described here in terms complicated and even contradictory;the grief over the loss of her mother, a figure that hadn’t an easy presence,and the years of distance they’d had between them. As Vogel writes: “Grief hasa long passage. For months I referred to my mother’s death in the present tense.My mother dies. Was what I said and wrote. What was this slippage? When I foundout, I paced the floor until my knees left me. And then I crawled toward the bathroom,picked up an old toothbrush and proceeded to clean the room with it. I beganunder the claw foot tub. Stretched out, on my belly, my cheek pressed to thefloor, I reached for the furthest corner.”

February 26, 2024

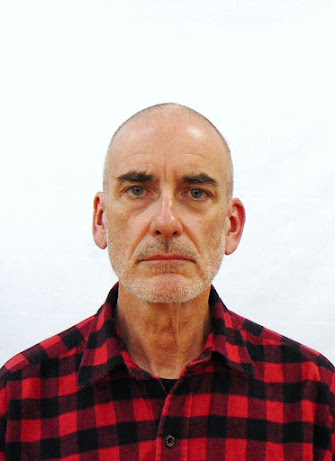

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ian Seed

Ian Seed's recent collections of poetry and prose poetryinclude Night Window (Shearsman,2024), Operations of Water (Knives,Forks & Spoons Press, 2020), and New York Hotel (Shearsman, 2018) (a TLSBook of the Year). His most recent translations are The Dice Cup, from the French of Max Jacob (Wakefield Press, 2022),and the river which sleep has told me,from the Italian of Ivano Fermini (Fortnightly Review Odd Volumes, 2022). See www.ianseed.co.uk

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

My first full-length collectionwas Anonymous Intruder. I was already 52 years old when it was publishedby Shearsman in January, 2009. Finally I could begin to believe that I was notan imposter after all, and feel much freer to make writing a real commitment.

My more recent work is on thewhole based more on narrative, while Anonymous Intruder revolved morearound association of images and sounds. Nevertheless, the voices in Anonymous Intruder are spookily similar insome respects to those in my most recent collection, Night Window(January 2024). Perhaps the main difference now (from Makers of Empty Dreams(2014) onwards) is that my writing is much more likely to make you laugh (inthe best sense, I hope), while remaining, in the words of Luke Kennard, ‘shotthrough with melancholy’.

2 - How did you come to poetryfirst, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I first came to poetry when Iwas 17, studying ‘A’-level English. One of our set texts was the Selected Poems of Edward Thomas(1878-1917). I was fascinated and haunted by the melancholy and sense of regretin his poems, as much as I was moved by his observations of nature, hislyricism, and his narratives of encounters. At around the same time, I began todiscover that there was a wide and eclectic mix of poetry out there. Forexample, my aunt had the Selected Poems of T.S. Eliot on her bookshelves,and I remember being drawn especially to ‘The Love Song of Alfred J Prufrock’,while, much more radically, my mother owned a copy of Kenneth Patchen’s Loveand War Poems, which is where I discovered prose poems, although I didn’tknow the term ‘prose poem’ at that time. Kenneth Patchen’s work was also myfirst encounter with surrealism. Then there was the Poet Modern Poetsseries of the 1960s and 70s; I was drawn to the likes of Alan Jackson, Jeff Nuttall and William Wantling in PMT 12, and Charles Bukowski, Philip Lamantia and Harold Norse in PMT 13. I loved the more minor poems ofDylan Thomas, such as ‘To Others Than You’ or ‘Twenty Four Years’ (‘ With my red veins full ofmoney,/ In the final direction of the elementary town / I advance as long asforever is’); I was not so keen on ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’, which Ifound (and still do) overly ‘poetic’. Mark Hyatt (1940-72) was a poet whofascinated me; I am so pleased to see his work now, fifty years on, finallygetting some of the recognition it deserves, and I have recently reviewed his Selected Poems: So Much for Life (Nightboat Books, 2023) for PN Review. Thisis all very male and pale, I realise (reflecting what was mainly on offer atthe time, even in anthologies such as Michael Horowitz’s Children of Albion:Poetry of the Underground in Britain), but I also loved Sylvia Plath’s Arieland some poems by Rosemary Tonks that I discovered in an anthology editedby Edward Lucie-Smith. My favourite poems I would copy into an exercise book tocarry around with me.

Reading poetry made me want towrite. Most of what I wrote was pretty awful, of course, but I got better tothe point where an English teacher, David Herbert, who was a poet himself,introduced me to the world of ‘little magazines’ and encouraged me to send somepoems off. I would like to say I never looked back, but after having some veryminor success with publishing – poems in magazines of the time, two tinypamphlets published, one self‑published pamphlet featured on local radio(thanks to a contact of David Herbert’s), I more or less stopped writing at theage of 24 and didn’t come back to it in any serious way until two decadeslater, when I had a kind of mid-life crisis – I am glad that I did. (If you’reinterested for more details on my writing journey, see https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk/2022/06/seed-penguin-poets/ , https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk/2018/10/discovery-rediscovery/ and https://ianseed.co.uk/background .)

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend just to ‘turn up forwriting’, even if it’s only for a few minutes a day, and then I go from there. Sooneror later, poems or pieces of short prose start coalescing around certainthemes, which I may then develop into a collection over a period of around twoor three years. I tend to write quickly and quite copiously but around 90% ofwhat I write does not make it into a published piece. Like most writers, I do alot of editing and simply playing around with language, imagery and narrative. Ofcourse, there are those rare occasions when I get lucky and write somethingwhich I suddenly realise reads the way it is meant to be without me messing itup in a second draft.

4 - Where does a poem usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Poems usually begin when I goback to all my messing around with words and images, and see if I findsomething which I can then tease into a poem. I am definitely an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into something larger. Nevertheless, inspite of the lack of deliberate plotting, my poems and prose poems are usuallyinterlinked in any one collection, and can be read as a kind of continuousstory, albeit a fragmented one. Georgia Matthews, reviewing New York Hotel(Shearsman, 2018) for Stride magazine, suggested that readers will findthemselves invested in the characters and narratives as they would in a novel.(Perhaps I am really a frustrated novelist at heart!)

5 - Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I love doing readings because Ican see in real time how people respond to my work. And it’s always good to seea few more books being sold.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I remember recently comingacross an old note written in my early twenties saying that I wrote ‘to createsomething of beauty and to move people.’ That may sound a bit clumsy and naïve,but I think that even in my youth my ultimate aim was not one ofself-expression, but of doing something interesting with language, imagery andnarratives, and sometimes rhythm and sound. Which is not to say that thereisn’t a lot of self-expression and hidden confession in my writing – there is.

I tend to let my writing poseits own questions without looking for immediate answers; the questions cansometimes be political ones, such as an exploration of our attraction tostrongmen (e.g. ‘Tutor’ in New York Hotel), but more often they are acombination of personal, archetypal and aesthetic ones.

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

This is a monster of aquestion, rob, and any answer risks being a portentous one. There are a fewwriters who are able to capture the spirit of an age or the voice of ageneration. Clearly, I am not one of those. In any case, I would not wish to hoistany role onto a writer, though they should take responsibility for what they sayand not use language to spread hatred.

I see my own role more tocreate poem-stories and to take readers into a world which will make people notknow if they want to laugh or cry, or both at the same time. As James Tate famously said in aninterview with Charles Simic for ParisReview, ‘Ilove my funny poems, but I’d rather break your heart. And if I can do both inthe same poem, that’s the best. If you laughed earlier in the poem, and I bringyou close to tears in the end, that’s the best. That’s most rewarding for youand for me too.’

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s always good to getsuggestions from an editor. Even if I don’t agree, it will make me go back to mywork with fresh eyes. I am grateful to all my editors.

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Turn up for the writing – everyday, if you can, but if not, then on a fairly regular basis. It’s easier forpoets – we can work in short spurts; much more difficult for a novelist.

Have faith in the poem orstory; trust in where it wants to go, not in where you want it to go.

10 - How easy has it been foryou to move between genres (poetry to translation)? What do you see as theappeal?

I see translation as being justas creative as my ‘own’ writing. When I translate poetry into English, I ammaking something new. The appeal and challenge of translation for me is tocreate a text which is as true to the spirit and letter of the original as itcan be, but also reads naturally in English while at the same time preservingthe otherness of the original.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I tend to wake early and justhandwrite while lying in bed. I build lots of notes like this to go back toevery couple of days – this is where the next stage of writing begins, assumingthere is anything in my early morning writing worth taking further; if not, nomatter: there will be the next day, or the day after that.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I like to reread authors I findliberating through their use of language, for example John Ashbery, Mark Ford,Sheila E Murphy, Jeremy Over.

Or I will return to authors whomay reflect the mood I’m in, such as Lucy Hamilton or Mark Hyatt (both of whosebooks I have reviewed recently for PN Review). Kenneth Patchen is alwaysgood to go back to.

Or I will write reviews –paying attention to another author’s work is enriching and refreshing for myown work.

Or I will cut up an articlefrom a magazine and work with the pieces. The great thing about cutup andcollage (although not a technique I use often) is that you never know whereit’s going to take you.

13 - What fragrance reminds youof home?

The smell of cat fur. I like todig my nose into the fur of our ancient cat, just as I did with cats we hadwhen I was a child.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think I am still influencedby different British 1960s TV series that I watched as a child, such as TheAvengers and The Prisoner: their zaniness, sense of menace, andsurreal quality, even if they weren’t strictly surrealist.

I’ve listened to blues, countryand rock ‘n’ roll since I was in my teens, and I’ve always had a bit of anobsession with Elvis. This makes its way into my work, for example ‘Country’ in

New York Hotel or ‘Inthe Anniversary TV Special, the Real’ in Makersof Empty Dreams. For more on Elvis, see https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk/2019/01/building/.

Art also influences my work,and on occasion I have written pieces in response to artists such as JosephCornell, Edward Hopper and Giorgio de Chirico.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many writers have entered mybloodstream and remained. I will read almost anything and gain somethingfrom it. I suppose I am most drawn to ‘outsider’ literature; I read ColinWilson’s The Outsider when I was in my teens, and that set the terms formuch of my initial plunging into the work of authors such as Dostoevsky, Knut Hamsun, W.N.P. Barbellion, Blake and Kafka, especially the latter.

Imagism and Surrealism alsohelped shape my youthful world outlook, and I think this has very much stayedwith me.

In my early twenties, I readauthors such as Jean Rhys, Ralph Ellison, Aldous Huxley, James Baldwin, EM Forster and DH Lawrence. Oh, and I loved Anna Kavan’s Ice. Once myItalian was good enough (I worked in Italy for ten years), I got into Dante inquite a big way after reading TS Eliot’s essay on Dante (his own personalfavourite among all his essays). I also worked for two years in Paris (teachingEnglish as a Foreign Language), and after around a year, I felt confidentenough to read authors such as Ionesco, Gide, Sartre, Patrick Modiano, Simone de Beauvoir, and Annie Ernaux in the original French. And Pierre Reverdy, notimagining that thirty years later I would publish the first translation of Le voleur de Talan into English (see https://wakefieldpress.com/products/the-thief-of-talant ).

And languages are of immenseimportance to me. I should confess that I am entirely self-taught, and still sufferfrom imposter syndrome. I picked up Italian, French and Polish by living andworking in Italy, France and Poland (though I am rusty in all of them now thatI have been living in the UK again for the last twenty or so years). Even my personalitywill change according to which language I am speaking. When I have the rare opportunityto speak Italian, I feel as if I am my thirty-year-old self again living inItaly.

16 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

Learn German well enough to read Kafka in the original. I’ve recently started abeginner’s class.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I only make a partial living as a writer and translator, so I have always had toearn my living in different ways, some more conducive to my character thanothers. I really just wish I hadn’t stopped writing for so long between myearly twenties and early forties. Apart from anything else, I believe thatwriting helps me to be a better person. Writing makes me listen to my own voices,and as a result helps me to listen better to the voices of others.

18 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

That’s just the way the cookie crumbled.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve just finished reading David Copperfield – very late on in life, Iagree. I have to confess that it is only in the last ten years that I havereally taken to much of 19th-century English literature, to authorssuch as George Eliot (especially Daniel Deronda), the Brontës (especially Charlotte Brontë’s Villette), and Wordsworth (especially The Prelude). I am notsure why it took me so long to properly enjoy some of the great literature ofmy own country.

A very powerful and distinctivebook of contemporary poetry I read recently is Lucy Hamilton’s Viewer |Viewed (Shearsman, 2023) – my review is just out in PN Review.

The last great film I saw: Anatomyof a Fall, directed by Justine Triet. A good one for writers to watch.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

My writing is a bit quiet at the moment. I don’t have anyparticular project going, but I expect one will emerge as long as I keep‘turning up’ for the writing.

Thanks so much for thequestions, rob!

February 25, 2024

Kate Greenstreet, Now that things are changing

American poet Kate Greenstreet was good enoughto send along her latest title, the hand-sewn full-sized chapbook Now thatthings are changing (arrow as arrow, 2024), her first publication in quitesome time since her fourth full-length title, The End of Something (BoiseID: Ahsahta Press, 2017) [see my review of such here], the fourth in a quartetthat suggested an ending, just as this small collection teases at a kind ofpivot, perhaps. A pivot into and towards something further, else. As she wroteof that fourth collection as part of her 2017 interview in Touch the Donkey,realizing that, through composing The End of Something, as she offered, “[…]I was putting down a fourth corner to define a formerly open-ended space.” Therewas a finality there that certainly felt final, suggesting she was simplymoving on to other projects, other things, and would return to poetry in herown way, in her own time, and perhaps, through this, we are inching closer tothat time. In certain ways, Now that things are changing exists as acovert publication, as Greenstreet has been seemingly-silent on publishingpoems since the publication of The End of Something, and the final arrow as arrow blog post in 2010 leads to a website that no longer exists (and I can’tfind contacts for series editors Michael Slosek or Luke Daly, despite whatever breadcrumbsthe internet might offer). Do any of them even exist? [UPDATE: their website is actually here] Of the fifteenpublications listed at the back of Now that things are changing (numberedsixteen in the series), the first thirteen of these occasional chapbooks appearedsemi-regularly, from 2006 to 2014, followed by Cedar Sigo’s On the Wayin 2021, Hannah Brooks-Motl’s Still Life in 2022, and now this,appearing with the date “Winter 2024.”

We were only going to bethere a couple of days, but the first

thing I did was scrub thewall above the stove, wash the floor,

and move the furniturearound. I put the big chair in a corner

of the kitchen, where thelight was best. Then I took a bath.

What was possible that neverbecame actual?

What else was real?

Eitherway, perhaps I should just hold on to the fact that this small chapbook ofpoem-fragments rests in my hands. Now that things are changing issimilar in structure and tone to her prior published poetry, self-containedlyric first-person sections of meditative commentary and speculation that sitone to a page and allow for the interaction, almost accumulation, of playingcards: less a narrative trajectory than a game of poem-fragment solitaire, eachnew piece reacting to all that came prior. “Lately I’ve been working insilence.” she writes, close to the opening of the collection. “No music, hardly/ reading. Walking in the mornings, almost no one on the street. / Abandonedstorefronts, barber shop, a laundromat. A few / parked cars that never move.” Thepoems sit as three clusters of seven poems each (twenty-one in total),suggesting a measure of some sense of narrative trajectory, even as these poemslean into a kind of ongoing field notes on life on earth, silence, interiorityand the body. Throughout, these poems, this chapbook, offer a curious kind ofcatch-all that manages to be simultaneously composed of self-contained unitsand building blocks toward something larger. “You can’t deny plot.” She writes,as part of the third cluster, “The way it moves. The way it pulls down dirt andtrees from / both sides of the river.”

It's been snowing allday. Last night, a big fire several blocks

away. You can’t reallytalk about faith without coming to the

topic of being forsaken.

I made a list with theheading: What do we look for in

relationships? The last thing I thought of was corroboration.

Plot development wasnumber two.

February 24, 2024

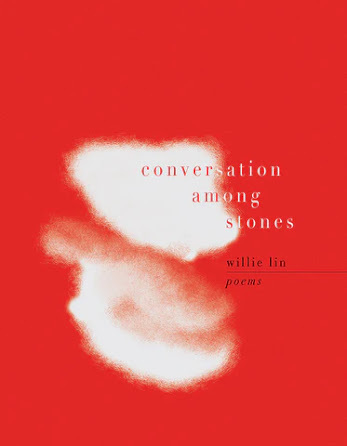

Willie Lin, conversations among stones

Birth

Already, the crops arefailing.

The crows shuttling backand forth,

breaking branches,dropping stones.

How easy to read sadness

into the empty room. It isyours.

All season the family hasbeen filling

pots and jars with riverwater

heavy with red silt. Theyare tired

of that color. Cover themoon.

It is good to be inconsolable.

It is good to leave thefish uneaten,

to sing a little, sweepthe floor.

Traces of breath,abundant as winter,

the uncreated memory ofyou.

Thefull-length debut by Chicago-based poet Willie Lin, following the chapbooks LesserBirds of Paradise (MIEL) and

Instructions for Folding

(Northwestern UniversityPress), is

conversations among stones

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023),a collection of meditative lyrics composed in clear narratives with directpurpose. “A knife pares to learn what is flesh.” the two-line poem “Dear” offers,“What is flesh.” There’s a remarkable way Lin’s poems unfold, unfurl and slowlyreveal, offering an intriguing patience, pause and cadence. “The things in mylife / I remember with perfect clarity:,” she writes, but I’d offer that thesepoems themselves are wonderful examples of that “perfect clarity” she suggests,as Lin composes first-person intimacies of thought and narrative that work to comprehendthe world, both internal and external, and how one finds and secures one’s place.There’s a lot of considering within these poems, and a lot to consider. “Nowwhen the wind comes,” she writes, to open the poem “Brief History of Exile,” asix-page expansive lyric set at the heart of the collection, around all else isstructured, “I lean into it. / I’m learning to be that pure, relinquish orcarry without // seeming to.” This is a book of tethering and of feelingunplaced, untethered, attempting to better comprehend those connections, andthe very notion of belonging, instead of automatically attempting to latch onto what might come along next. “I thought if I / could desire less / I could behappy.” she writes, to open the poem “Gauntlet for the Left Hand,” “I wasmoving toward / an idea.”

Thefull-length debut by Chicago-based poet Willie Lin, following the chapbooks LesserBirds of Paradise (MIEL) and

Instructions for Folding

(Northwestern UniversityPress), is

conversations among stones

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023),a collection of meditative lyrics composed in clear narratives with directpurpose. “A knife pares to learn what is flesh.” the two-line poem “Dear” offers,“What is flesh.” There’s a remarkable way Lin’s poems unfold, unfurl and slowlyreveal, offering an intriguing patience, pause and cadence. “The things in mylife / I remember with perfect clarity:,” she writes, but I’d offer that thesepoems themselves are wonderful examples of that “perfect clarity” she suggests,as Lin composes first-person intimacies of thought and narrative that work to comprehendthe world, both internal and external, and how one finds and secures one’s place.There’s a lot of considering within these poems, and a lot to consider. “Nowwhen the wind comes,” she writes, to open the poem “Brief History of Exile,” asix-page expansive lyric set at the heart of the collection, around all else isstructured, “I lean into it. / I’m learning to be that pure, relinquish orcarry without // seeming to.” This is a book of tethering and of feelingunplaced, untethered, attempting to better comprehend those connections, andthe very notion of belonging, instead of automatically attempting to latch onto what might come along next. “I thought if I / could desire less / I could behappy.” she writes, to open the poem “Gauntlet for the Left Hand,” “I wasmoving toward / an idea.”February 23, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Clint Burnham

Clint Burnham

has lived in Vancouver since 1995.

Clint Burnham

has lived in Vancouver since 1995.1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst chapbooks were published by Lillian Necakov’s Surrealist Poets Gardening Assoc and Daniel Jones’ Streetcar editions – Lillian published The And thatCain Forgot and Jones did The Toronto Small Press Scene – both in1990, the first was minimalist fiction, which I’ve continued to do up to myrecent White Lie book from Anvil (2021) & the book of mine you justdid (The Old Man: New Stories – 2024) and the second a critical accountof local publishing. So there is a certain thru line – I continue to writefiction/poetry, mostly published with small(ish) presses like Coach House (back20 years ago), Arsenal, Anvil, Book*hug; and I write criticism, mostlypublished by Canadian or international presses (in anthologies fromMcGill-Queen’s University Press, but also Routledge, Bloomsbury, Palgrave).

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Again,poetry/fiction AND criticism – at the same time, in the late 80s. For me, someof the poets that came out of TISH and the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E and from mygeneration, the KSW, emulated that “impossible” non-relation (as we say inLacan-speak) between criticism and creativity, a scholar and a poet (but not ascholar-poet). A scholar-poet, in my reckoning, means either just a bougielyric poet employed by the uni, OR the poems full of obvious or encodedversions of, say, one’s research on TS Eliot or Donne or The Iliad (or,just as bad, theory code words like “grammatology” or “affect”). But my originstory is that when I was in high school in Regina, Sask., in the late 1970s, Icame across a bill bissett poem in an anthology, (“th wundrfulness uv th mountees our secret police”?), I started writing lower-case, phonetic poems,submitted a wack of them to a Sask. arts board manuscript service, can’tremember the response. My high school teacher at the time, Ruth Robillard, wasamazing, also had me reading Camus & Ondaatje. John Newlove came to read –he was writer in residence at the Regina public library (78? 79?). I moved toVictoria in 1980, at military college for a year before getting the boot, thenfell in with writers in the city and around the university, including Gail Harris, Clint Hutzulak, and the poet Stephen Scobie who also taught. ThenToronto, to go to grad school, in the late 1980s, when again, fell into thesmall press community there, which led to a few chapbooks already mentioned.After that it’s book books, in Toronto and then Vancouver.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Istart in the Notes app, usually. (I’m very ADHD so keep getting distracted,copy down things, forget to finish this question., come back to it monthslater):

Certainly for The Old Man: NewStories, the project of mine you just published (thanks rob!), but also TheGoldberg Variations, my poetry collection due out this spring (2024) fromNew Star, that was the origin. Cutting & pasting from other texts tofriends & vice versa (when some of the stories in Old Man firstoccurred/were written, I’d send them to friends by WhatsApp or Signal etc. For TheGoldberg I took what were written in bold heading font for the Notes app,and then dropped them all into a Word file and kept the line breaks from theapp (so, in media studies lingo, the “affordances,” what’s SOP), then startedmoving them around, first into sonnet like things of 7+7 12+2 or 8+6 blocks,which became strings for the first three poems (“No to a harm rinse,” “Weddinghi viz,” and “Passion waged” – this was being put together in Berlin in thesummer of 2022 so “Wedding” refers to that neighborhood), then strings of7x2line couplets (“History b’y” – or Newfie for History boy). “5.2 cop crows”was then just single lines separated, and the next two poems “Back-out drink”and “Looks aren’t” were written as one line per page, compressed for reasons ofpolitical economy. “No to Nato,” the next poem (title taken from Weddinggraffiti) then had two 7 line columns: you can read across or down. This wasroughly half-way thru the manuscript so then I started fucking shit up. “B.A.”(named for a character in the great social democratic 80s tv show The A-Team)was structured like that vile contribution of Vancouverism, the podium and tower condo – so thin lines interspersedwith fatter ones, indented (with a few that ran over the end, which I alwayslike, so you get:

forced feeding scene, orderly flickingcigarette ash onto food

in funnel in hose in

nostril serves me right just took thedamned documentary

film course

which takes a memory of revulsionwatching Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies in a film course in the1980s, and exceeds the page just as the visual described in the poem exceededboth the patient’s and my own bodies.

The poems that follow, “QUELNSEN”(historic centre of the Kòmoks people) strings up the various sonnet forms (7+712+2 or 8+6 blocks etc), “More likely a stroller” and “Cherry” are one-offs,“Coq. (pron. coke)” (as in Coquitlam or kwikwetlam) and “Frownlines get Marx-y”are working with the double columns (which, again, had much moving textaround). Followed by “Naum Gabo!” both a gnarly Russian futurist whosecardboard structure I saw (still preserved, 100 years later, isn’t that crazy)and a song by Vancouver art-punks U-J3RKS, more futzing around with Vancouvercondo-types, and finally “stéyəs LOSER” (the formeran island in the Salish Sea, in the W̱SÁNEĆ language, the lattera 90s grunge ref., natch), where it all falls apart/comes together, take yourpick.

NB re working from Notes app, that’sembedded in “5.2 cop crows”:

why if Nate

Mackey writes his poems in

his iPhone notes app is that

cool? and who remembers

Ho Tak Kai? but if I do it

just looks like thud? I mean this?

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Iwas asked about this but, continuing what I said above, don’t be too knowing.Or when you are too knowing, make that its own thing, so you’re not too knowingabout being knowing. You never know what you’re doing in a work. Or when youthink you do, you become one of those bloviators, telling you what their workmeans.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Thisis a tough one, because I don’t like directly political writing or art, but Ido think writing and art has a politics. For me, when it shows up in the work,it may be content, or it may be form. The use of quick commentaries orobservations via my phone to the collection you published, that process, seemsto me to be the politics of The Old Man. I find if I “intend” or “try”to write a political text, it fails. It has to nominate me, not the other wayaround. Or: the unconscious.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Ilove being edited. It’s very carnal.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard given to others?

Irarely send to places I don’t have a relationship with.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Ireally like Simon King’s TikTok on Northern Alberta. Lydia Davis’ Strangers.Jonathan Glazer’s film Zone of Interest. Just finishing EmilyWilson’s translation of The Iliad.

20- What are you currently working on?

A continuation of/sequel to WhiteLie, more super short stories. Now published by you!

February 22, 2024

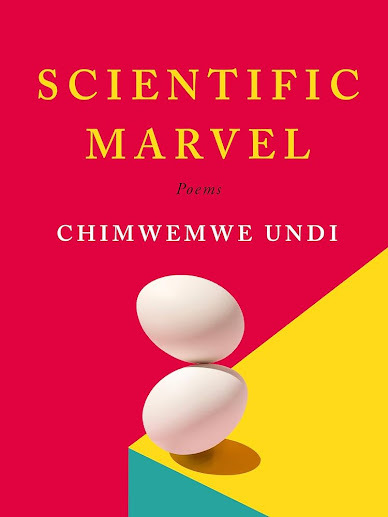

Chimwemwe Undi, Scientific Marvel: Poems

AGAINST “MANITOBA”

Build a province of ourabsence,

and that province comesto pass

And it passeslegislation, and the legislation

is profuse with theabsence you allege.

I suggest your unseeinghas its consequence.

I suggest the coastsunmoor you,

and those distant citiesfit your heads.

Your bad spell echoes inthis centre

of emptying centres. We measurewheat

in seeds. Your insistencefollows

your gaps, a needle

leaving two holes and onestitch.

From2023-24 Winnipeg poet laureate Chimwemwe Undi comes the impressive full-length poetrydebut, Scientific Marvel: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2024), a sharp andself-aware assemblage of prairie gestures, lyrics and examinations. “Goodpractice is dissolving my beloved / into traits,” she writes, as part of theopening poem, “PROPERTY 101,” “either useful / or distinct.” Undi is well awareof Winnipeg streets and prior descriptions, citing specific local markers suchas prairie sky, Portage and Main and the works of John K. Samson and , two other Winnipeg artists deeply immersed in articulating their love ofthis shared space. Undi’s is a love equally thoughtful, critical and filledwith light, offering sparkle and wit, humour and deep critique. “A beautifulcountry,” she writes, to open the poem “GRUNTHAL, MANITOBA (2019),” “so full ofbreath / The sky as wide open as a howling throat // My throat as wide open asa prairie sky / As blue, as hungry to ungive what’s been taken // You can’tgive back what has been taken / Unname the place named what it already is [.]”

From2023-24 Winnipeg poet laureate Chimwemwe Undi comes the impressive full-length poetrydebut, Scientific Marvel: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2024), a sharp andself-aware assemblage of prairie gestures, lyrics and examinations. “Goodpractice is dissolving my beloved / into traits,” she writes, as part of theopening poem, “PROPERTY 101,” “either useful / or distinct.” Undi is well awareof Winnipeg streets and prior descriptions, citing specific local markers suchas prairie sky, Portage and Main and the works of John K. Samson and , two other Winnipeg artists deeply immersed in articulating their love ofthis shared space. Undi’s is a love equally thoughtful, critical and filledwith light, offering sparkle and wit, humour and deep critique. “A beautifulcountry,” she writes, to open the poem “GRUNTHAL, MANITOBA (2019),” “so full ofbreath / The sky as wide open as a howling throat // My throat as wide open asa prairie sky / As blue, as hungry to ungive what’s been taken // You can’tgive back what has been taken / Unname the place named what it already is [.]” Thisis an impressive collection, one comfortably powerful, without the awkwardstretches of so many other debuts; she knows full well what she is doing, withoutany sense of showiness or hesitation, but a calm understanding of her ownlyric, her own strength. “Taking its title,” as the press release offers, “froma beauty school in downtown Winnipeg that closed in 2017 after nearly 100 yearsof operation,” the lyrics of Undi’s Scientific Marvel investigate andinterrogate the landscape of Winnipeg as city and cultural space, articulatingalternate perspectives on what had so long been assumed, presumed or simplyignored. She writes a field guide of gestures, expectations, absolute delightsand utter losses. “every horizontal edge the city hesitates,” she writes, aspart of “FIELD GUIDE TO THE BIRDS OF NORTH AMERICA,” “and they die in suchnumbers / with such specifity that scientists / name it and watch unmoved [.]”Undi tethers her lyrics to these local histories, that sense of Winnipeg space,fully acknowledging the self-described lineages through lovely, performativegestures, guttural markers and lines composed as direct offerings turnedsideways. “It is bigger than its targets,” the short poem “IN DEFENCE OF THEWINNIPEG POEM” reads, in full, mid-way through the collection, “& still small,& there is nothing to do // & so much to be done, & here // at thecentre of a bad invention, // it is, in fact, pretty cold.”

Undiincludes, sprinked through the book, a thread of erasures out of the text of “Bakerv Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration),” a landmark decision of theSupreme Court of Canada, in which Mavis Baker, a Jamaican woman who had livedin Canada without status for more than a decade, appealed for fairness inregards to potential deportation, in part due to her having given birth to fourchildren while living and working in Canada. Undi uses these erasures to writeof erasure itself, a kind of prairie insistence to set aside what might not fitneatly into presumed categories. Through her interrogations, Undi continues a threadof articulating prairie Blackness that has become more prevalent over the pastfew years, sitting alongside books such as Bertrand Bickersteth “Writing BlackAlberta” through The Response of Weeds: A Misplacement of Black Poetry on the Prairies (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2020) and The Black Prairie Archives: An Anthology, ed. Karina Vernon (Waterloo ON: Wilfrid LaurierUniversity Press, 2020). For Undi, specifically, it is Winnipeg, the city thatloves to hate to love itself, and all within. “What else // will we cleave? Thelight before / and after,” she writes, as part of “SPRING, OR SPIRAL IN THREEPARTS,” “the smokeless air.”

February 21, 2024

rob mclennan reads at Fluid Vessels : The Online Reading Series of the Montreal International Poetry Prize

Fluid Vessels : The Online Reading Series of the Montreal International Poetry Prize

Fluid Vessels : The Online Reading Series of the Montreal International Poetry Prize11 March 2024, 1 PM ET / 5 PM GMT

Host: Jay Ritchie

Readers: Caroline Bird, rob mclennan, Vivek Narayanan

sign up here to join! www.montrealpoetryprize.com/fluid-vessels

February 20, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jill McCabe Johnson

Jill McCabeJohnson’s third poetrybook, Tangled in Vow & Beseech (MoonPath, 2024), was named afinalist in the Sally Albiso and Wheelbarrow Books poetry prizes. Honorsinclude an Academy of American Poets prize, the Paula Jones Gardiner PoetryAward from Floating Bridge Press, twoNautilus Book Awards, plus support from the National Endowment for theHumanities, Artist Trust, and Hedgebrook. Recent works have appeared in Slate,Fourth Genre, Waxwing, The Brooklyn Review, Gulf Stream,Brevity, and Diode. Jill is editor-in-chief of Wandering AengusPress. https://jillmccabejohnson.com

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first poetry book was a collection of persona poems, all written inthe imagined voice of the sea. It allowed me to write from a persona that feltto me as though it were innocent, wise, and brimming with love. Subsequentbooks and chapbooks, including the latest book, Tangled in Vow & Beseech,have fewer persona poems. Even when the pieces aren’t about my life, they feelfar more personal and therefore risky. At the same time, I hope readers willconnect with them in a more intimate, meaningful way. I don’t know if thewriting changed me or if changes within me changed the writing, but I do feelmore confident in myself as a person and poet, and that allows me to expose myvulnerabilities more in relationships as well as on the page.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Lo, so many years ago, when I started at the wonderful MFA program, theRainier Writing Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University, I wanted to studypoetry because I believed it would provide a foundation for writing in prose,too. The attention to image, music, form, diction, and even, at times,narrative teaches a kind of precision but with unlimited wildness, too. It’s contradictory, but it teaches a personto work without constraint despite constraints—basically doing the impossible.Who could resist?

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I wish there were one, predictable way. Sometimes the writing comes in anunexpected gush, other times it emerges as a complete package, and too often itflops into the world, a floundering, unwieldy mess.

4 - Where does a poem or essay usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

For me, poems almost always begin with an image but are written fromsound. It took me a long time to trust the sounds bubbling up and onto thepage. Now, I do my best to get out of the way of what the subconscious wants tosay. Easier said than done, of course. The essay writing process is similar,except that it usually begins with an unusual incident or situation, forexample, getting laid off from a job or sitting with my father’s dead body.Like so many have said before me, I don’t know what I have to say until I beginwriting. That takes its own form of trust and getting out of the way, too. Withenough smaller pieces and momentum, I finally see what a larger manuscript isworking toward. If I try to force things, the writing isn’t as good.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readings are fun, and I do find it informative to see how audiencesrespond to narrative pieces. Mostly, I just love when authors and readersconnect during a live reading, regardless of whether I’m in the audience or onthe stage.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

In the last several years, I’ve been writing my way through trying tounderstand gender violence. I don’t really even want to write about it, but thesubject won’t let me go. It’s frustrating because there are so few answers, andI don’t like most of them, anyway. But the subject has me in its grips for now.We’ll see where it leads.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

Do we have to have roles? Can we simply write what matters to us?

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

All praise for editors! I can’t be objective about my work. I can’treread it and hear it for the first time. Editors help us clarify and refine.That doesn’t mean their suggestions should always be taken. We still have to bediscerning about how we revise, but editors help us see when there’s need torevise and ways we might do it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Stan Sanvel Rubin said to read widely, even work you don’t like, becauseyou learn from it and might even grow to appreciate it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toessays)? What do you see as the appeal?

It’s hard for me to go immediately between working on poetry and prose.With a little time between—a walk, for example—it’s easier. There’s a differentmindset required, at least for me, to write in one or the other. Even fromessay to essay or poem to poem. It’s as though my mind needs a palate cleanser.That said, I love writing both. Some things are better suited for an essay or apoem, and I like being able to go between.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My husband and I have a bed and breakfast. Summers are insanely busy, somy writing routine doesn’t follow a daily schedule. It’s on a yearly cycle,with only short work and revision in the summers and longer works in thewinters when I have time to immerse myself more deeply.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Any good writing will inspire me to write. Also, writing just after a napor when I wake in the morning, assuming I don’t reach for my phone and read thenews.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The scent of a briny seashore.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Books come from the rattling sound of the hoola-hoop at your ninthbirthday party, from the bully who broke your glasses playing dodge ball, theycome from the coffee-flavored candies in your grandmothers crystal box, fromhow it felt to tear the necklace your first boyfriend gave you from your14-year-old neck when he broke up with you and started dating your sister, fromoysters roasted open over campfire coals, from the ache in your lungs hikingMt. Si and being too embarrassed in front of your athletic friends to stop andcatch your breath, from kissing your dead mother’s forehead, from apologizingto your son for shaking his shoulders when he forgot once again to turn in hishomework, from listening to a flock or red wing blackbirds singing winter inside-out.Books come from books? Don’t make me laugh.

To be fair to David W. McFadden, books absolutely inspire and influencethe creation of other books. I also like to look at the structure of things andmake correlations to writing, for example, is the work like a nautilus, ariver, a pair of lungs, a branching tree? Good standup comedians are experts atshaping story. They know how to setup a situation and seed an idea, as well ashow to convey a story specifically and concisely, and how to close in asatisfying yet surprising way.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I read so widely, this is a tough question to answer. There are too manywriters I love to even attempt to list them, though Rebecca Solnit would bevery high on my list.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Skydive. Live in Paris. Hike in Patagonia. Master bread-making. See bothmy husband and son grow old. Be kinder to everyone. Forgive. Listen. Accept.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

Botanist. Cheesemaker. Marine biologist. Jazz singer. Weaver. Chimneysweep.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

How else to connect with humanity and express wonder and try to make theworld a better place?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: All the Light We Cannot See

Film: The Square

20 - What are you currently working on?

Lyric essays as well as essays on gender violence.

February 19, 2024

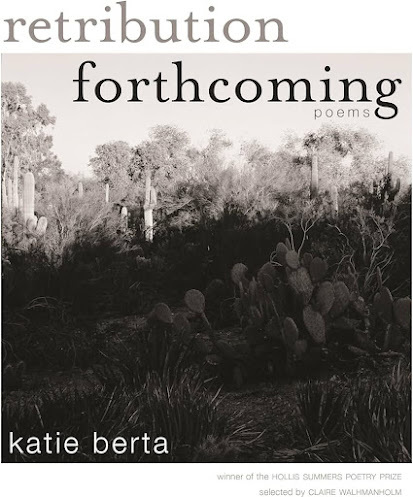

Katie Berta, retribution forthcoming: poems

I Will Put Your NameRight in the Poem

Don’t be offended—I willput your name right in the poem

because what you do iswho you are and we can all see what

that is. Or—don’t beoffended—I will put your name right

in the poem because I needyou to see that you don’t

scare me anymore. Hello,little man. Why are you so upset

to see your name in thepoem? Did you not say “whore”?

did you not say, “Hopeyou die soon”? I will put your name

right in the poem becauseI have saved all the receipts

for just this occasion. Iwill put your name right in the pom

because I don’t care ifit fucks your ass up, my dude.

I will put your nameright in the poem. Just wait for my poem,

little baby. Here itcomes.

Thereis a force behind and within the lyrics of Iowa poet Katie Berta’s full-lengthdebut,

retribution forthcoming: poems

(Athens OH: Ohio University Press,2024), winner of the Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, as selected by Claire Wahmanholm. Across a lyric simultaneously stark and lush, Berta offers astunning and expansive display of articulating devastating events and anenormous heart, one that no longer wishes to hold back. As the poem “I lived ina beautiful place” begins: “and then in a place of bitter cold. / I had aterrible brain. When the winter came, / it brought with it a series ofcomplications. / Always having to put on a hat and coat. / Snow falling overthe tops of your boots. / Many thoughts over which I had no control.” There isa clarity and a fierce self-protection, entirely finished with the nonsense ofothers, that is propulsive, across poems that are expansive, slick and scalpel-sharp.“The earth is short. Reason / is short. Each person’s extends /up over her head,” the poem “Cave,” near the end of the collection, begins, “petersout / as the air gets thin.” The poems carry enormous wounds and anxiety,populated by rapists, ex-boyfriends, rattlesnakes and the body of a deadmotorcyclist, most of which hold titles as warnings for content, whether “AfterI was raped the second time, I lost forty pounds,” “The women I thought of as popularin high school / are having babies who die” or “The NY Times Real EstateSection Publishes Pictures / inside the Expensive Apartment Belonging / toYour Ex-Boyfriend and His New Wife.” Composed as short essays or monologues, thereare poems here that are utterly devastating, all presented in such a clear,straightforward lyric, describing heartbreak, sexual assault, emotionalbrutality, thoughts of retribution alongside elements of absolute, open-heartedbeauty, working through and across the worst of things toward something better.The poem, for example, “Remembering that time in my life / when I used to thinka lot about innocence,” includes, towards the end: “Something about it touches/ me, touches a raw, open place, the way a man / never would. / Is it the corerushing up to take the place / of all that stuff, all that was outsideof me, entering / almost without permission?” It is a lot to digest, and evenmore to process, but throughout, both author and narrator have clearly realizedthey deserve better, and these poems are the direct result of that discoveryand new ownership. As that same poem offers, to close: “Here is my boyfriend, /engaged, as usual, in the garden. I watch him from the window / as he moves, /like a lake does, in the wind.”

Thereis a force behind and within the lyrics of Iowa poet Katie Berta’s full-lengthdebut,

retribution forthcoming: poems

(Athens OH: Ohio University Press,2024), winner of the Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, as selected by Claire Wahmanholm. Across a lyric simultaneously stark and lush, Berta offers astunning and expansive display of articulating devastating events and anenormous heart, one that no longer wishes to hold back. As the poem “I lived ina beautiful place” begins: “and then in a place of bitter cold. / I had aterrible brain. When the winter came, / it brought with it a series ofcomplications. / Always having to put on a hat and coat. / Snow falling overthe tops of your boots. / Many thoughts over which I had no control.” There isa clarity and a fierce self-protection, entirely finished with the nonsense ofothers, that is propulsive, across poems that are expansive, slick and scalpel-sharp.“The earth is short. Reason / is short. Each person’s extends /up over her head,” the poem “Cave,” near the end of the collection, begins, “petersout / as the air gets thin.” The poems carry enormous wounds and anxiety,populated by rapists, ex-boyfriends, rattlesnakes and the body of a deadmotorcyclist, most of which hold titles as warnings for content, whether “AfterI was raped the second time, I lost forty pounds,” “The women I thought of as popularin high school / are having babies who die” or “The NY Times Real EstateSection Publishes Pictures / inside the Expensive Apartment Belonging / toYour Ex-Boyfriend and His New Wife.” Composed as short essays or monologues, thereare poems here that are utterly devastating, all presented in such a clear,straightforward lyric, describing heartbreak, sexual assault, emotionalbrutality, thoughts of retribution alongside elements of absolute, open-heartedbeauty, working through and across the worst of things toward something better.The poem, for example, “Remembering that time in my life / when I used to thinka lot about innocence,” includes, towards the end: “Something about it touches/ me, touches a raw, open place, the way a man / never would. / Is it the corerushing up to take the place / of all that stuff, all that was outsideof me, entering / almost without permission?” It is a lot to digest, and evenmore to process, but throughout, both author and narrator have clearly realizedthey deserve better, and these poems are the direct result of that discoveryand new ownership. As that same poem offers, to close: “Here is my boyfriend, /engaged, as usual, in the garden. I watch him from the window / as he moves, /like a lake does, in the wind.”