Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 59

March 20, 2024

Rob Manery, As They Say

who nowhere

or near

and indeed unwritten

or aware

will aim

at least

clutching

upon each

each end

ends each

further

on (“Sometimes Welcome”)

Vancouverpoet and

SOME magazine

[see my review of the seventh issue here] editor andpublisher Rob Manery is one of a handful of west coast poets that seem topublish intermittently enough (comparable to Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Lissa Wolsak [see my review of Wolsak’s collected poems here], Kathryn MacLeod [her above/ground press title is still available] andAaron Vidaver [see my review of Vidaver’s most recent here]; former Vancouverpoet Colin Smith [see my review of his latest here], now in Winnipeg, is alsoworth mentioning), that one might understandably lose track, one of manyreasons why it is good to see his second full-length collection

As They Say

(Chicago IL: Moira Books, 2023). There are those that might recall Manery as anOttawa poet during the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, collaborating withLouis Cabri as the Experimental Writers Group and curating readings at Gallery101, later publishing hole magazine and eventual chapbooks under holebooks while curating the N400 Reading Series at The Manx Pub until he left townfor Vancouver in 1996 (Cabri, on his part, left Ottawa for Philadelphia in1994). At least twice if not three times the size of his first collection, AsThey Say follows

It’s Not As If It Hasn’t Been Said Before

(Vancouver BC: Tsunami Editions, 2001), and chapbooks

Richter-RauzerVariations

(above/ground press, 2012), Many, Not Any (Vancouver BC: SomeBooks, 2023) and

Elegies

(above/ground press, 2022).

Vancouverpoet and

SOME magazine

[see my review of the seventh issue here] editor andpublisher Rob Manery is one of a handful of west coast poets that seem topublish intermittently enough (comparable to Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Lissa Wolsak [see my review of Wolsak’s collected poems here], Kathryn MacLeod [her above/ground press title is still available] andAaron Vidaver [see my review of Vidaver’s most recent here]; former Vancouverpoet Colin Smith [see my review of his latest here], now in Winnipeg, is alsoworth mentioning), that one might understandably lose track, one of manyreasons why it is good to see his second full-length collection

As They Say

(Chicago IL: Moira Books, 2023). There are those that might recall Manery as anOttawa poet during the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, collaborating withLouis Cabri as the Experimental Writers Group and curating readings at Gallery101, later publishing hole magazine and eventual chapbooks under holebooks while curating the N400 Reading Series at The Manx Pub until he left townfor Vancouver in 1996 (Cabri, on his part, left Ottawa for Philadelphia in1994). At least twice if not three times the size of his first collection, AsThey Say follows

It’s Not As If It Hasn’t Been Said Before

(Vancouver BC: Tsunami Editions, 2001), and chapbooks

Richter-RauzerVariations

(above/ground press, 2012), Many, Not Any (Vancouver BC: SomeBooks, 2023) and

Elegies

(above/ground press, 2022). Thereis such a wonderful heft to this collection, as though everything Manery hadworked on prior has been a kind of lead-up into this (the Elegies poems appearnear the end of the collection, as well). With poems that stretch and sequence,Manery’s is a language-fueled lyric of small movement across great distances, constructedas a kind of compressed expansiveness. “I at least / yield,” he writes, as thepenultimate poem in the seven-fragment sequence “These Constant Moments,” “toinarticulate / distances // if you depend / on these // unwelcome convictions /these constant // moments / some borrow [.]” Manery’s poems hold such exact languageand thinking, crafted and crisp stretches, providing such a delightful array ofsound collision and jumble of meaning, providing the poems far greater than themere sums of their parts. “Please tell me a story,” he writes, as part of thepoem “If All My Woulds,” “just a little story, // hemmed-in between the Would /and the Should, or the Must. It wasn’t / always like this? I count my / selfthe same man whether / I want or have.” There’s a staccato to his short lines,enough that he writes less across the page than straight down, providing a languageof craft and baffle, drawing vocabulary from multiple sources (depending on thepiece), from Sophocles, John Donne, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Louis Cabri, CatrionaStrang, Bob Hogg, Ted Byrne and Dr. Robin Barrow, among others. He utilizescollision and collage in such way to provide an effect of the pointed sketch, quicklines that simultaneously offer meditative pause and propulsive force. As hewrites as part of the book’s acknowledgements: “The Elegy poems draw almost allof their vocabulary from John Donne’s Elegies (Signet Classic, edited by MariusBewley). Each elegy in the series corresponds to the same numbered elegy pennedby Donne.” Built as a highly deliberate work of meditative collage, As TheySay is an assemblage of Kootenay School of Writing-infused language poetryas thoughtful and purposeful as anything I’ve seen. Rob Manery’s work hasclearly been flying underneath the radar for far too long.

do not excuse

a lie too

severe

and scrupulous

allow some

reservation

or illation

which they call

desirous of

some secret words

or was at that time

irresolute

both opinions

are possible

by their gravity

maturity, judgement

indifferency,incorruption

the impugners

carping at

just equivocations (“Equivocation”)

March 19, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions for John MacLachlan Gray

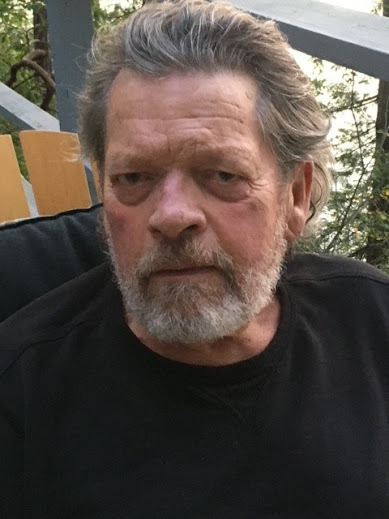

John MacLachlan Gray

[photo credit: Beverlee Gray] is amultiple award-winning writer and composer for stage, television, film, radioand print.

John MacLachlan Gray

[photo credit: Beverlee Gray] is amultiple award-winning writer and composer for stage, television, film, radioand print. In past decadeshe has appeared as a theatre director; as a composer/librettist of stagemusicals; as a satirist on CBC TV's The Journal, as a magazine journalist; as ascreenwriter; a columnist for The Globe and Mail and the Vancouver Sun;and as the author of five acclaimed novels.

A recipient ofmany awards including the Governor-General's Medal, he is an officer of theOrder of Canada.

He is currentlyworking on Mr. Good-Evening, the third in a series of novels set in 1920s Vancouver, following The White Angel and Vile Spirits.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first novel “Dazzled” was written in 1980, while I was in New Yorkwith “Billy Bishop Goes to War.” It gaveme something to do during the day. Though delighted that Irwin published it (after many, many revisions), Istill thought of myself as a working composer/librettist/pianist & wasworking on my musical “Rock And Roll.”

Then in the Nineties, the market for musicals (mine at least)tanked.

I started with non-fiction but became bored.

I had learned how to do dialogue and character, so I took upscreenwriting (Rock And Roll became a feature video, King of FridayNight ) & got into the craft of it, several scripts optioned, one thatactually became a film (Kootenai Brown). In the process I learned a good deal aboutmany things – especially plot and structure.

Then for some reason, I wanted to write a thing. Not a potential play or movie, but a thing. Like a painting – even if nobody seesit, it's still a painting.

So I decided to write plot-based novels, movies for people's minds,& eliminate the middlemen.

Which also eliminated the camera and microphone – and meant I would haveto do that job in sharp, rhythmic prose that kept people awake, interested,fascinated, whatever.

The other thing was that it would have to keep meinterested. It's a long, arduousprocess. As a person somewhere along theADD spectrum, I like crime novels. Not whodunnits, novels in which thefascinating thing isn't the crime itself, but what it reveals about humanbeings.

So I wrote A Gift for the Little Master, about a serial killerwho goes into management – ie manipulates weak people into becoming serialkillers themselves. The main charactersare a TV news girl, a multiracial bike courier & a bad cop. I wrote the book in English Prime – minus theverb to be – because this is a world where everything is changing, wherenothing is. Random House Canadapublished it. Yay.

At this point my agent suggested that I write a crime novel set inVictorian London. Which got me thinkingabout how Victorian my childhood was & how Victorian things still are. (Igrew up in a Victorian family, in a hundred ways.) Plus, this was when Vancouver arrested aserial killer who HAD murdered sex workers, in which the police had shown anastonishing reluctance to reach that conclusion – instead, they showed the sameassumptions & attitudes Victorians held, about “fallen women – as lostsouls who are doomed by their sinful profession.

The Fiend In Human was snatched up by international publishers, whosaw it as another The Exorcist; problem was, even Caleb Carr couldn'tproduce another The Exorcist. Somerave reviews but disappointing sales. They published White Stone Day andNot Quite Dead in fewer numbers, then lost interest entirely. (Publishers used to publish authors; thanksto Conde Nast, now they publish books.)

2 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

It takes me a year to come up with a plot. A plot isn't a story - a cause-effect chain;it's a petri dish that needs a certain amount of material to grow on its own,and it all has to interrelate. And eventhen it's vague. At some point I alwaysfind I have been wrong about something crucial & have to double back.

3 - Where does a work for page or stage usually begin for you? Are youan author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or areyou working on a "book" from the very beginning?

There's a long period of “controlled dreaming.” When I start in earnest I already have ashadow in my mind.

4 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings – especially Q&A.

5 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I'm just the old guy in the basement, working on his model train.

That said, I'm interested in psychopathy (interviewed Dr Hare a fewtimes). Evil as an absence –something trying to complete its self. A Rabbi told me that “The Tree of Good And Evil” in the Hebrew reads assomething like The Tree ofthat-which-is-complete-and-that-which-is-incomplete.”

It's a valid frame for a villain: Something Is Missing.

6 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I don't do “should.” I'm agnostic. In my brain at least, writing has become so intertwined with thinking,that writing has become thinking itself. Things need to be put into words. As opposed to blurting sentences, writing a thought down means you canlook at it & decide if that's the best way to say it. There have been storytellers as long as therehave been human beings; let's say some got laryngitis or something & wroteit down as they told it. There's ademand for their tablets...

7 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

Essential and fun. My motto is,“I am more than happy to take credit for your thoughts.” There is nothing like being read by a trainedreader who's not a pal & who has edited a shitload of material & isbasically on your side. Writing issolitaire; publishing is a team.

Lack of editing is the main reason bestsellers are so thick – anA-list author turns in a bug-crusher & the editor says “marvelous,” becausethey want to keep their job.

8 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Don't push the river, it runs by itself – in otherwords, Have faith in the process of the universe.

9 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (crime fictionto stage musicals)? What do you see as the appeal?

In my so-called career, I have just kind of backed into things. I have no idea how I became a newspapercolumnist; nor how I ended up on national TV for 5 years. Someone may have suggested it – an angel,perhaps. But switching genres has keptme interested, if fear can be equated with interest - there is always anembarrassing ropes-learning period that makes one shudder later on.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I do nothing for a year except accumulate scattered notes. When I decide to put the dream in writing, Igive it a couple of hours a day, starting with the packet of scribbles I jotteddown on pieces of paper and in a file called “Yet More Shit.”

Once I have a first draft & can see what's there, I work longerhours fixing, re-writing, chopping, etc.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don't. I do something else forawhile & let the greater part of the brain work it out.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of creamed salt codfish on mashed potatoes, with melted butter& pepper.

The smell of the Atlantic Ocean. (Smells different from the Pacific.)

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Music is central to my being. (Ican't remember not playing the piano.) Going over a paragraph, I hear it - hear it stutter & cack,and I try to make it sing. Themusic part isn't the ability to play butto listen.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Graham Greene; Richard Condon (Winter Kills, The Manchurian Candidate); Pierre LeMaitre (Alex, Camille); Patricia Highsmith,Muriel Spark.

The Yoga practice that developed out of Covid means I do a couple ofhours a day surrendering to Gaia. I'mstretchier than before, but not as wise.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'll write another book, or part of one, whether it gets published ornot. (It was like that with The WhiteAngel.)

It's what I do.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

My Grade 8 teacher recommended I take up a trade like welding. And I suppose I could have carried on sellingsuits for Fred Asher, Stores For Men in 1974. Or I could have worked in a universitytheatre department, bored footless. Andif Billy Bishop had been a hit on Broadway, I could have become analcoholic screenwriter – or perhaps a crime novelist.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had nothing better to do at the time. No kidding.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Drive Your Plow Over The Bones Of The Dead, by OlgaTokarczuk. Everything a crime novel“should” be.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I have something going on in my head about the 1934 Bedaux Expedition innorthern BC & its connection to Heinrich Himmler's quest for the origin ofthe Arian Race. Meanwhile in Vancouver,it''s the year before the Battle of Ballentine Pier - Fascists financed theShipping Federation are preparing for a showdown with Communist Unionists. And a policeman sent to investigate a murderfinds himself in the territory of the Nahani, which is literally anotherworld. Am waiting to find out whathappens.

March 18, 2024

Nate Logan, Wrong Horse

At the end of a toughweek, I treat myself to some curbside steak, broccoli, and brick of bread. I waitfor the bill and see right into the restaurant. A hostess rolls her eyes so farin her head, I feel a little sick. Some child uses a red crayon with disturbingflourish. A slice of cheesecake is put in front of an elderly couple. I’m theonly person in the designated to-go parking area. The wind nudges the car witha sock foot. (“Parking Lot”)

Thesecond full-length collection by Wisconsin prose poet and editor Nate Logan, following

Inside the Golden Days of Missing You

(Magic Helicopter Press, 2019), aswell as a small array of chapbooks (including one by above/ground press), is

Wrong Horse

(Chicago IL: Moira Books, 2024). I’ve been following for a while thecurious trajectory of the American prose poem, one that appears to have been furtheredquite prominently by the late Russell Edson [see my review of his posthumous selected poems here], a form that leans rather hard into what others mightsuggest as a very short or postcard story. There seem a handful of poetsfollowing that particular influence: Sarah Manguso’s early work, for example,or that of Evan Williams, Elisa Gabbert or Benjamin Niespodziany. Logan’s narrativeprose poems, through Wrong Horse, might share certain elements of all ofthe above, but not necessarily the surrealist and cinematic elements ofNiespodziany, or the theatrical gestures and impulse of Gabbert, yet the same elementsof scene-composition remain. Logan’s approach, instead, offers a curious andeven kinetic push against endings, refusing to provide those easy or expectedlandings. Logan’s poems offer a calm, almost unsettling sense of quiet, writingsomething slightly off in the narrative, unsettling the very foundation of the narrative;not in a surrealistic way, but something else, other. There is such a fantasticsubtlety to the way Logan approaches each prose-block, each poem, a quietudethat might allow inattentive readers to not fully appreciate just what it ishis work provides. His poems put all those narrative parts into play, intomotion, but stops just short of the implications, allowing the reader to fillin the rest. “To spend the equinox in a hammock,” he writes, to close the poem “TheHome Stretch,” “wasting my life. Or not breaking the backs of mothers walking aWeimaraner. And there’s the mannequin again with an egg in its mouth.” As Loganwrote as part of a statement on prose poems last fall, for periodicities: ajournal of poetry and poetics:

Thesecond full-length collection by Wisconsin prose poet and editor Nate Logan, following

Inside the Golden Days of Missing You

(Magic Helicopter Press, 2019), aswell as a small array of chapbooks (including one by above/ground press), is

Wrong Horse

(Chicago IL: Moira Books, 2024). I’ve been following for a while thecurious trajectory of the American prose poem, one that appears to have been furtheredquite prominently by the late Russell Edson [see my review of his posthumous selected poems here], a form that leans rather hard into what others mightsuggest as a very short or postcard story. There seem a handful of poetsfollowing that particular influence: Sarah Manguso’s early work, for example,or that of Evan Williams, Elisa Gabbert or Benjamin Niespodziany. Logan’s narrativeprose poems, through Wrong Horse, might share certain elements of all ofthe above, but not necessarily the surrealist and cinematic elements ofNiespodziany, or the theatrical gestures and impulse of Gabbert, yet the same elementsof scene-composition remain. Logan’s approach, instead, offers a curious andeven kinetic push against endings, refusing to provide those easy or expectedlandings. Logan’s poems offer a calm, almost unsettling sense of quiet, writingsomething slightly off in the narrative, unsettling the very foundation of the narrative;not in a surrealistic way, but something else, other. There is such a fantasticsubtlety to the way Logan approaches each prose-block, each poem, a quietudethat might allow inattentive readers to not fully appreciate just what it ishis work provides. His poems put all those narrative parts into play, intomotion, but stops just short of the implications, allowing the reader to fillin the rest. “To spend the equinox in a hammock,” he writes, to close the poem “TheHome Stretch,” “wasting my life. Or not breaking the backs of mothers walking aWeimaraner. And there’s the mannequin again with an egg in its mouth.” As Loganwrote as part of a statement on prose poems last fall, for periodicities: ajournal of poetry and poetics:There are frequent stopswhen traveling by prose poem; for me, this is one of its unique charms, maybethee charm that keeps me coming back. Unlike another poem that can move betweena line that spans across the page and a zig-zag all within the same piece, Iknow, and the reader knows, the prose poem will start and stop, then start andstop again. Being invited to sit with sentences, poetic sentences in noparticular hurry, is a pleasure. Furthermore, the tendency for the prose poemto wind around surrealism (neosurrealism?) is a nudge to the reader to staywith sentences longer—the associative leaps lend themselves to contemplation(this is a whole other essay). The “radicalness” of the prose poem still liesin its form, but the beat has changed. And when the poem does end, either atone paragraph or a few pages, if it goes especially well, the accumulation ofsentences stirs a reader, which is what all good poetry should do (even still,Charlie, I didn’t mean to make your mom cry).

March 17, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Katie Berta

Katie Berta’s

debut poetry collection,

retribution forthcoming

, won theHollis Summers Prize and was published by Ohio University Press. Her poems haveappeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, The Cincinnati Review,The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Denver Quarterly, TheYale Review, The Massachusetts Review, and Bennington Review,among other magazines. She has received residencies from Millay Arts, Ragdale,and The Hambidge Center, fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and theVirginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, and an Iowa Review Award. She isthe managing editor of The Iowa Review and teaches literary editing andpoetry at the University of Iowa and Arizona State University.

Katie Berta’s

debut poetry collection,

retribution forthcoming

, won theHollis Summers Prize and was published by Ohio University Press. Her poems haveappeared or are forthcoming in Ploughshares, The Cincinnati Review,The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Denver Quarterly, TheYale Review, The Massachusetts Review, and Bennington Review,among other magazines. She has received residencies from Millay Arts, Ragdale,and The Hambidge Center, fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and theVirginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, and an Iowa Review Award. She isthe managing editor of The Iowa Review and teaches literary editing andpoetry at the University of Iowa and Arizona State University.

1. How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Writing this book changed my life, I think. Or my lifechanged as I wrote this book. When the earliest poems in the book were written,I was exiting a period of my life that was dense with gendered trauma that Iwasn’t able to describe or investigate—in my writing or with my loved ones. Bythe time I finished the book, those experiences became less charged and morearticulable. I’m not sure whether that happened because of the act of writingor whether those traumatic experiences just aged out of their charge. Eitherway, this book was there as my life changed. People who know the undergraduatewriter I was or the MFA student I was or even the early PhD student I was mightsay the work in this book isn’t trying to gesture at experiences, to suggestthings, as maybe I did previously. Instead the book clearly describes. I thinkthat’s a change—a habitual gesture of new poets is to always find ways ofsaying without saying. This book taught me (or told me) not to do that anymore.

2. How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As a kid, I was actually much more interested infiction—it’s what I read and could imitate—but it quickly became clear that Iwas never going to finish anything that required any real follow through. Iwrote a lot at school when I was supposed to be paying attention, and thatdoesn’t leave a lot of time for completing longer work. I’m not sure what myfirst encounters with poetry were, but I started writing it in middle school. Ikept trying to write short stories into my first years of college, butcompleted them the way I completed other assignments—they were all last minuteand half-assed. And it just never stuck like poetry did—I could write andcomplete poem after poem and fix them up later. That way of working was justmore suited to the type of writer I am.

3. How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

I think, usually, when a project is beginning, I don’trealize it’s a project at all. I’m just thinking, “Well, this is a new kind ofpoem!” And the newness piques your interest a little, so you try to dosomething similar in the next poem and the next and on and on. And that becomesa project—or something like a project. Usually, in that stage of my writingprocess, I’m excited and poems are easy to produce. They might be the jankiestversions of the new work you’ll do, but they’re the most excited to you, sothey’re quick. And those poems might need a lot of work later, but the poemsthat come after them, once you’ve learned whatever new mode you’re working in,need a little less.

4. Wheredoes a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I’m never really thinking about a book when I write a poem.I’m writing single poems that hopefully will connect to each other thematicallyor by their voice and sound. I recently described the process of writing apoetry book as making and then collecting—you create and then curate your ownwork, which means you have to treat it like you’re an editor looking in fromoutside, deciding what’s good enough and what goes well enough with what youalready know you want. I’ve had to write many more poems than can fit in apoetry book so that I have choices between them, so I can make a book thatfeels cohesive and sturdy, as a piece of art.

5. Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love readings because they’re one of the only situationswhen writers witness the unvarnished reactions of their audience. I’m greedyfor feedback, so I read poems that I expect will make the audience laugh orotherwise express themselves. I wouldn’t call this a part of my creativeprocess, per se, but it is something that keeps me going, that inspiresme and makes me feel I’m a part of a community.

6. Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

It feels like a lot of writers are asking why we write atall, in the face of the serious global concerns we all feel too puny to change.Does it matter whether you write the great American novel if our way of life isobliviated by climate change? If entire civilian populations are being obliviatedby war? Writing as an art and a profession is having to deal with the ways it’sobsolete culturally (Americans read an average of 12 books per year and manyread none at all) and obsolete functionally (can books be used to affect acultural or political climate that requires massive corporate interests tofunnel money toward or away from any cause or value-system or politician inorder for that cause or value system to succeed or fail?)—is it callous to keepwriting your little poems knowing they’re not for anything? Of course wecan’t help it—humans are built to make stuff. And poets were more likely thanmoney-making writers, I think, to know that their art doesn’t have to be foranything and to already have bemoaned their lack of impact, but I know I’m notimmune from asking why, crying over it, and trying to address somethingin the art I make. Usually those somethings are the concerns I brush upagainst in my own life (I always think of the title of a poem by a friend, Sara Sams: “But Think, Are You Authorized to Tell It?” she asks). It often dependson the identity and the perspective of the reader, though, whether thoseconcerns are considered political and theoretical rather than interior,personal, or private.

7. What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Poems are speaking to very few people, which means they canbe as frank as they want. Maybe our very small role should be to speak very loudly,and in an annoying voice? I think of Solmaz Sharif’s amazing poem “Patronage”all the time, in which she critiques the system by which poets have to buildcareers (and depend, largely, on universities for support) and the ways itlimits what we think we can say: “They [poets] step/in as one steps in/to anursery and//quiet//calms the tantrum/attempts not to wake/the sleeping, themilkdrunk//and burped babe.” Of course, Sharif is a writer who is a great counterexamplefor that ultra-quiet, apolitical poet she describes.

8. Do you findthe process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Are people reticent to edit poets? I don’t think I’ve had aneditor suggest large changes to my poetry. Maybe they know poets are especiallyprickly and will use our genre to justify even our most unhinged choices (speakingfrom my experience as a writer, not my experience as an editor—at TheIowa Review, our contributors in all genres are universally lovely).

9. What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I was just at a reading and conversation between Sally Ball and Ellen Bryant Voigt and Voigt said, to revise, make the poem ugly. If it’sugly to you, you’ll be able to change it. I think this is a brilliant idea—andwe really do depend on our impulse to “fix” the “broken” poem to fuel ourrevision efforts—but I also just liked that piece of advice on its own: “Makethe poem ugly.” Why not? There’s nothing “good” (in any innate, intellectual,or moral way) about writing a pretty poem. We write pretty poems to show thatwe know what pretty is and to show that we can be pretty—and because webelieve beauty gives pleasure. But I (we?) get pleasure out of ugliness too.I’ll be working on some ugly poems this year, I think.

10. How easyhas it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What doyou see as the appeal?

These genres serve such different purposes for me. Lately, I’vebeen telling people that poems are a place of internal quiet in which I get toexplicate what I think and feel without the invading presence of another mind.In conversation, I often (always?) feel myself distorting in order to servewhat I believe the other person thinks and feels. This often gets me intotrouble, as whatever I’m reflecting to them/expecting of them isn’t always (isnever?) what they meant or wanted. In the poem, I’m in conversation with myselfand am following, to me, my most authentic intellectual impulse instead ofserving anyone else. Writing critical prose, on the other hand, feels like I’mapplying my mind to someone else’s work and should, on some level, be serving theirwork first. I like writing criticism because it gives me an occasion to thinkreally deeply about a book or poem—but it’s less about finding out what I thinkand more about practicing a kind of attention that I love to give to writingand art.

11. Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

I wouldn’t say I have a routine. Instead, I will beg,borrow, or steal any moment during which a poem arises. And the impulse towrite a poem comes and goes. Over the last year, I wrote, maybe, the fewestpoems of my life. I work from home and I suspect I just encountered less stuff,fewer things to make an image out of or to spark a bit of language. SinceJanuary, I’ve been writing about two poems per week. They happen when theyhappen—and that’s the luxury of being a poet rather than a prose writer—I scrawlsomething down in the car before going into the grocery store, if needed.

12. Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

I’ve been feeling devoted to Terrance Hayes for a littlewhile—his new book, So to Speak, has taught me a lot about patterningand repetition, a lot about using pattern and repetition to make an impact on the reader(see his “American Sonnet for the New Year,” whichbegins the book). The speed and funniness of poems like that one inspire me toget going again when things stall out. I’ve also returned to Frank Bidart thisyear—he’s another favorite, and I’ve been reading a poem a day from hiscollected since January. I think having a practice like that helps poems come alittle more easily—like priming your mind for later poetry use. Also,walking—writing and walking are accessory activities.

13. Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of rain in Arizona reminds me of my childhood insouthern California.

14. David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I really am a one-form girl, and mostly books made my book,but I also think my book came from the people—and the animals—that livealongside me. I also didn’t think I was engaged with the natural world, butsince coming back to Arizona, I’ve been lucky enough to experience awe in theface of natural things. I think books come from that feeling too.

15. Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I always come back to Anne Carson, who I was introduced toas an undergrad and who I still love to think and write about now. Sylvia Plathwas an early influence who is always popping up in my poetry. As I said above,Terrance Hayes is really important to my ideas about how poems work, why theywork. Ghost Of is also a book that influenced me really deeply (I don’tsay Diana Khoi Nguyen because I haven’t read her new book yet)—her ability tocreate a voice that exhibits to the reader/generates in the reader a certain emotionalmode. Tommy Pico, Rachel Zucker, Bernadette Mayer, Morgan Parker are all swimmingaround in the same brain pool, for me. Mary Ruefle, Chelsey Minnis, Jay Hopler,on and on…

16. Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Everything, it still feels like! Invite me anywhere! I’llbe happy to get out of the house!

17. If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think I’d be a lawyer or in some other wordy job. Gettinga JD and using it in the much more urgent ways one can use a law degree (vs. anMFA, which feels very useless at the end of the world) still sometimes seemsattractive to me.

18. Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Really, there was nothing else. I don’t think there wasanything else I wanted, or that wanted me.

19. What wasthe last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Favorite books I encountered for the first time last year: NoOne Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood, Just Us by ClaudiaRankine, Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party by Chessy Normile, Blackfishingthe IUD by Caren Beilin, Repetition Nineteen by Mónica de la Torre, Aug9 – Fog by Kathryn Scanlan, Spectral Evidence by Gregory Pardlo, andPerson of Interest by Susan Choi. It’s still too early to tell aboutthis year’s books. I also recently encountered Taste of Cherry, the 1997film by Abbas Kiarostami, for the first time. I’ll take that one with mewherever I go now.

20. What areyou currently working on?

I recently started writing poems in a more associative modethat are starting to cohere into something like a manuscript—many of the poemshave ended up called “The Internet.” I’ve been thinking on those and trying tokeep that impulse going. And I’m working on a review of a new novel for theEmily Dickinson International Society Bulletin. And I’m trying to decidewhether a verse novel I was writing is really a verse novel or if it’s just abook of poems. Lots of little things to tinker with. Lots of things to keep mebusy.

March 16, 2024

Gary Barwin, IMAGINING IMAGINING: Essays on Language, Identity & Infinity

What about mycohabitation with books? Unlike the well-ordered collection of my grandparents,that served to reinforce, preserve and establish – though part of me longs forsuch a Talmudic colloquy with the traditional structures of inquiry – I wishfor my own library to surprise and confound. To afford me the chance, as DylanThomas says, to read “indiscriminately and all the time with my eyes hangingout.” My personal library isn’t in one place. It’s pervasive. It’s scattered. Itoozes. It’s environmental. It’s in most rooms in the house. On shelves. In stacks.Beside the bed. In the bathroom. In books borrowed or ones that have wanderedoff to friends and family. I think of it as rhizomatic. Connected in invisible yetnourishing ways. From book to book. From book to me. And from book to my nowadult kids. They have some of the books, as indeed, I ended up with some of myparents’ books, as I still think about the books they had in my childhood. To paraphrasea discussion about Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of culture, the library “spreadslike the surface of a body of water, spreading towards available spaces or tricklingdownwards towards new spaces through fissures and gaps …” (“The Archive of Theseus”)

I’mvery much enjoying Hamilton poet, novelist, visual and sound poet, performer, collaborator, musician and teacher Gary Barwin’s latest, the collection ofessays

IMAGINING IMAGINING: Essays on Language, Identity & Infinity

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2024), twenty-three non-fiction piecesoriginally prompted, as he writes in the acknowledgements, by Wolsak & Wynneditor/publisher Noelle Allen, “who had the idea for a book of essays in thefirst place and whose keen editorial advice was invaluable.” As he writesfurther on, “Most of the essays here were written specifically for thecollection, but many were adapted from work written for other occasions […].” Composedwith humour and expansive thinking that punctuate the length of breadth of hisother work, these essays provide a curious and foundational centre for and howhe got to where he is now in his creative life; immersed equally, it wouldseem, in an array of genres and movements—from surrealist poems and novels tolyric narratives, visual and sound poetry, musical composition and performance,and a range of collaborations across each and every one of these forms—in anopen, engaged and questioning manner. The essays here articulate the shapes of histhinking, and how one idea might, impossibly, connect to another. “Before wecontinue,” he writes, as part of “Wide Asleep: Night thoughts on Insomnia,” “aword about digression and association. Association seems apropos to sleep (theoriginal Rorschach test) – borderless irrational night, ten-dimensional dream,time as an infinitely sided crystal made of pure possibility and quantum entanglement.Almost anything can relate to sleep. The endless monkey bars of darkness. The chocolatebar wrapper of night. Ten emus lined up, shaggy, ready to brush against yourclosed eyes.” There is such delight in the discoveries and connections thatBarwin makes in these pieces, and seeing ideas and references connect in realtime might perhaps be the finest element of these essays. Consider, forexample, the opening of the first essay, “Broken Light: The Alefbeit and What’sMissing,” that begins:

I’mvery much enjoying Hamilton poet, novelist, visual and sound poet, performer, collaborator, musician and teacher Gary Barwin’s latest, the collection ofessays

IMAGINING IMAGINING: Essays on Language, Identity & Infinity

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2024), twenty-three non-fiction piecesoriginally prompted, as he writes in the acknowledgements, by Wolsak & Wynneditor/publisher Noelle Allen, “who had the idea for a book of essays in thefirst place and whose keen editorial advice was invaluable.” As he writesfurther on, “Most of the essays here were written specifically for thecollection, but many were adapted from work written for other occasions […].” Composedwith humour and expansive thinking that punctuate the length of breadth of hisother work, these essays provide a curious and foundational centre for and howhe got to where he is now in his creative life; immersed equally, it wouldseem, in an array of genres and movements—from surrealist poems and novels tolyric narratives, visual and sound poetry, musical composition and performance,and a range of collaborations across each and every one of these forms—in anopen, engaged and questioning manner. The essays here articulate the shapes of histhinking, and how one idea might, impossibly, connect to another. “Before wecontinue,” he writes, as part of “Wide Asleep: Night thoughts on Insomnia,” “aword about digression and association. Association seems apropos to sleep (theoriginal Rorschach test) – borderless irrational night, ten-dimensional dream,time as an infinitely sided crystal made of pure possibility and quantum entanglement.Almost anything can relate to sleep. The endless monkey bars of darkness. The chocolatebar wrapper of night. Ten emus lined up, shaggy, ready to brush against yourclosed eyes.” There is such delight in the discoveries and connections thatBarwin makes in these pieces, and seeing ideas and references connect in realtime might perhaps be the finest element of these essays. Consider, forexample, the opening of the first essay, “Broken Light: The Alefbeit and What’sMissing,” that begins:When I was a littleleft-handed kid growing up in Ireland, we used fountain pens and I always smudgedthe letters as I wrote. I was really happy when I began going to Hebrew schooland found out that Hebrew is read from right to left – the opposite of English.I could write clearly now while all the right-handed kids smudged their writingand got ink all over their hands. It was electric: this idea that languagecould be turned around. That it could make you look at things differently. Yourinky hand. The page. Your way of being in the world.

Thissingle paragraph, akin to a strand of DNA, somehow holds the entirety of GaryBarwin’s approach to his entire creative output. Or at least, might provide anynew reader of his work a kind of introduction. To consider his poetry titlesfrom the past few years alone can be overwhelming, showcasing a small degree ofthose myriad directions he moves across almost simultaneously: Barwin andLillian Nećakov’s collaborative DUCK EATS YEAST, QUACKS, EXPLODES; MAN LOSES EYE: A Poem (Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here], the most charming creatures: poems (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022)[see my review of such here], a second full-length collaboration with TomPrime, Bird Arsonist (Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2022) [see my review of such here], a collaboration with Gregory Betts, The Fabulous Op(Ireland: Beir Bua Press, 2022) [see my review of such here] and For It Is aPLEASURE and a SURPRISE to Breathe: new & selected POEMS, edited withan Introduction by Alessandro Porco (Hamilton ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2019) [see my review of such here]. I won’t even begin to discuss multiple solo andcollaborative chapbooks, his musical performances (solo and collaborative),visual works, sound works, short prose or novels. How does he keep track of itall? Infinite, indeed. This is a remarkable work, and one remarkably layered, complex andpolyphonic, composed with such an ease through the language, even withinsurreal bends, quirky leaps and outright left-field asides. Somehow, theseessays introduce how the connections between seemingly-disparate works mightconnect, all part of the same expansive way of considering the world; howBarwin approaches and engages not only different perspectives, but multiple: heconnects his lefthandedness with learning Hebrew, and connects learning Hebrewwith his concurrent experiences growing up in Ireland. Through Barwin, somehow,everything connects, and there is such logic and clarity to his connections. I thinkof this paragraph, for example, included as part of the essay “That’ll Leave aMark,” which looks at collaborating in creating a public art sculpture, but onethat includes a perspective from years of working within the landscape of smalland micro literary presses in Canada:

A couple of years ago I,along with two artist friends of mine, Tor Lukasik-Foss and Simon Frank, werechosen to create a public artwork for the City of Hamilton. The work was to addressrefugees, migrants, immigrants, persecution, the search for freedom and safetyin new home. We designed and had ten bronze suitcases with a variety of symbolson them. One suitcase would lie open on its side with a live tree growing outof it. I’d never been involved in creating public art, let alone sculpture. Thelengthy and expensive process of creating bronze sculptures was fascinating. Hightemperatures. Fire. Blowtorches. Chemicals. Molten metal. Here was a work that Iwas involved in that was really heavy. Literally. And permanent. It could lastfor hundreds of years ensconced beside the path in the park. Not at all like aleaflet.

March 15, 2024

today is my fifty-fourth birthday,

although,between working on curating

next week’s VERSeFest

, working copy edits on myupcoming short story collection,

On Beauty

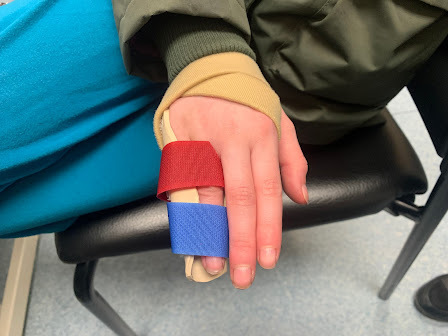

(scheduled to release in August)and a few other factors (Rose broke her right pinky recently, which meantmultiple attempts to find a working x-ray machine across Ottawa’s east end), I’vebarely had any attention span for any actual birthday anythings [where was I last year?]. Enough that I couldn’teven have my usual birthday gathering at the Carleton Tavern this time around (Itook too long to get around to booking, and by then, it was too late).

But VERSeFest next weekend is going to be amazing

. Have you seen the interviews appearingonline at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics to help promotesuch?

although,between working on curating

next week’s VERSeFest

, working copy edits on myupcoming short story collection,

On Beauty

(scheduled to release in August)and a few other factors (Rose broke her right pinky recently, which meantmultiple attempts to find a working x-ray machine across Ottawa’s east end), I’vebarely had any attention span for any actual birthday anythings [where was I last year?]. Enough that I couldn’teven have my usual birthday gathering at the Carleton Tavern this time around (Itook too long to get around to booking, and by then, it was too late).

But VERSeFest next weekend is going to be amazing

. Have you seen the interviews appearingonline at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics to help promotesuch?Andyou know the above poem from Robert Kroetsch, don’t you? Strange for me toconsider that I am now at the age where he was then, part of his Letters toSalonika (Toronto ON: Grand Union Press, 1983) (an edition gifted by dearhalf-sister a couple of years back), the poem-sequence he wrote about his then-wife, Smaro Kamboureli, being away, while Smaro was away and working on her in the second person(Edmonton ON: longspoon press, 1985). Not a solo birthday, but they leave soonenough: Christine and our young ladies head to hang out with father-in-law andhis wife in Boca Raton, Florida for four days, starting Sunday. I remain here,working on festival publicity and other such details. We hadn’t been tofather-in-law’s condo there since 2015, attempting an annual February/March tripthat we haven’t managed since Aoife was born [see my report on that 2015 trip].Had a different timing been possible, perhaps. I shall be home.

And,regarding Kroetsch: I’m still amused at the book he wrote about Smarobeing away, as Smaro wrote a book about Smaro being away. While Christinewas attending her two weeks at Banff Writing Studio in January of last year, I playedmy version of same, writing a poem sequence via Kroetsch’s own structure ofdailyness about Christine being away, which I produced last summer as achapbook, edgeless : letters, (2023). Be aware that the book she wasworking to finish during that period (the same project she turned from mound ofpaper to manuscript during her time at Sage Hill in 2019), Toxemia(Book*hug Press), is out this fall, and already up for pre-order.

Naturally,I’ve been wearing my birthday pin for the week, picking it up off a bookshelffor daily wear this past Sunday. I take the week, after all. I think it’s thatMarch Break holdover, unable to find the birthday acknowledgement my school-peersmight have, everyone home when mine would finally come around.

Naturally,I’ve been wearing my birthday pin for the week, picking it up off a bookshelffor daily wear this past Sunday. I take the week, after all. I think it’s thatMarch Break holdover, unable to find the birthday acknowledgement my school-peersmight have, everyone home when mine would finally come around. Distractedenough these days, that I’ve so far been unable to even consider a potential birthdaypoem this year. Might this be the first year I skip? We shall see what nextweek brings, hoping to get a couple of afternoons in a tavern somewhere, withnotebook and pen and mound of books, attempting to catch my breath a bit. Perhapsthe option remains. But let’s get through the weekend. Although, really, therehave been little to no poems for quite some time, focusing the past eighteenmonths on larger prose (fiction and non-fiction) projects; still, there werepages upon pages upon sketched-out notebook pages from our Florida jaunt lastfall [see my report on such here], but none of which I’ve been (as yet) able toreturn to. One project prompted by the work of Laynie Browne, another promptedby the work of Barry McKinnon. I keep hoping: soon.

Theyoung ladies this past March Break week in another Forest School day-camp [just like last year, except sans snow],although the finger Rose injured last week apparently a minor break, soWednesday morning was a second x-ray and a splint, which she must wear for fourweeks, followed by a further two weeks of tape. It means the end of those Saturdaymorning gymnastics classes, unfortunately (those things aren’t cheap, you know).

Theyoung ladies this past March Break week in another Forest School day-camp [just like last year, except sans snow],although the finger Rose injured last week apparently a minor break, soWednesday morning was a second x-ray and a splint, which she must wear for fourweeks, followed by a further two weeks of tape. It means the end of those Saturdaymorning gymnastics classes, unfortunately (those things aren’t cheap, you know).Iwork to further dismantle my home office, what I’ve been a month already workingon, moving myself into the finished basements. Our young ladies have become toobig to share a bedroom anymore. I’ve already moved multiple bookcases and atleast fifty to sixty boxes of books out of my office either downstairs or intostorage. The fact that neither child has even noticed what I’m doing yet mightsay something of them, but just as much the state of my office, I suppose. It wouldbe nice to have completed this task by the time they land home. I’m not sure suchmight be possible, but we shall see. I only started this process on February 6th.

Birthday,a check-in: in my note last year I mentioned an extended period of breathlessness,currently feeling I’ve been in a version of same since, what, last July? Pushingedits on my short stories, working on my genealogical creative non-fictionproject, “the genealogy book” [posting excerpts to substack, naturally], thehousehold taking turns across two weeks with flu at Christmas (every day a newcancellation of social gatherings, and a Christmas dinner at least four days late)and now my copy edits, which are actually due today. On my birthday? Come on.

Hopingonce the non-fiction a bit further along or even completed I can return to thenovel I began during the onset of Covid; a handful of shortstories-in-progress, as well as further essays on fiction writers. At leastthree poetry projects begun but on hold (as I said), including one that I’veexcerpted for the tenth anniversary issue of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], which lands in another month. And don’t I have a chapbooksoon with Montreal poet James Hawes’ Turret Press? And another full-length poetrytitle en route as well, recently accepted for most likely 2026 publication (butwe aren’t talking about that yet).

March 14, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michael Chang

Michael Chang (they/them) is the author of

SYNTHETIC JUNGLE

(Northwestern University Press, 2023) & THE HEARTBREAK ALBUM (Coach House Books, 2025). They edit poetry at

Fence

.

Michael Chang (they/them) is the author of

SYNTHETIC JUNGLE

(Northwestern University Press, 2023) & THE HEARTBREAK ALBUM (Coach House Books, 2025). They edit poetry at

Fence

.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My debut chap, DRAKKAR NOIR , came into existence because I won a contest. It was an eye-opening introduction to publishing, and the phenomenal people at Bateau Press took great care of me.

It's not up to me to say how the work is or feels different. I think the books demonstrate a natural evolution in my process. I'm trying to get at those same obsessions (not my favorite word) and concerns but from different angles.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or nonfiction?

I didn't have the patience for anything else.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don't think of them as projects, exactly. The writing comes in waves, and always hard and fast. I don't do "drafts" because I don't revisit poems after they are written.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For the most part I don't like themed books because the themes are often silly and the books grandiose and self-aggrandizing. In my own practice I tend to write until I have a critical mass of poems that I can bundle together in a collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I avoid readings unless I'm supporting a friend or have something to promote.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I'll write about anything and everything and do it with a critical eye, a strong point-of-view that could only be mine.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of the writer is entertainment. You should make people feel good, but it's okay to also make them uncomfortable and reflective in their positions.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

The editor-writer relationship must be governed by mutual admiration and respect. I have a very clear idea of how I want things to look, sound, etc., and editors know that coming in the door.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Sometimes people act not out of malice but out of stupidity.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

No routines beyond days earmarked as Reading Days or Writing Days. I keep those separate.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I never stall but imagine watching a good movie would bring me back.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Right now it's Serpentine by Comme des Garçons and Rose & Cuir by Frédéric Malle.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I don't talk about influences or references. Folx can (and should) draw their own conclusions from reading my work!

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I don't talk about other writers, either. I am highly focused on my own practice.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Run for office, maybe.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Something in fashion, probably.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Because nobody else is doing what I'm doing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Diane Seuss's new book, which she very kindly sent.

Probably the Taiwanese movie Your Name Engraved Herein -- heartbreaking but also lends itself to repeat viewing. Visually terrific.

19 - What are you currently working on?

A full-length collection, which is coming together very nicely.

Also getting my next book ready for publication in -- hopefully -- early 2025.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 13, 2024

Kate Bolton Bonnici, A True & Just Record

Sick, they drink. This isthe order of desire.

What can be seen:seeking.

What cannot:

In search of needs aburning to go from.

The fairy tree Spencerwill call warlike, in May

makes beauty thronged bydemand,

Belonging by custom not

by calling nor by name.

Is a walk with girls proximate

to the walk of the sickand which is other? wreaths

left nearby for thenearby image of one blessed

and one blessing

The near enough to hear,far enough to split

sickness, girlhood. Sad fringeof fairy belief.

She hears too from thoseso-called of bodies

Politic and church,having seen the there-gathered.

But what’s said is stuckat proving

a statement made, not anyother truth. (“Joan of Arc: Third Public Session, February 24, 1431”)

Thesecond full-length poetry title from Los Angeles-based poet Kate Bolton Bonnici,following

Night Burial

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for LiteraryPublishing, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

A True & Just Record

(Norwich UK: Boiler House Press, 2023), a collection originally prompted by andthrough the author’s interest in researching 16th and 17thcentury pamphlets during a period of time that quickly fell into the onset andinfluence of Covid-19 lockdowns. “Late March 2020,” Bonnici writes in herintroduction, “Witch Stichomythia: Chances, Changes, & Strange Shapes,” “I triedover the phone to help my grandmother—97, already living alone, and nowentirely isolated due to COVID-19 restrictions—figure out how to operate a laptopcomputer so that she could send emails and read the news online. Meanwhile inmy own reading, I toggled between doomscrolling hyper-current headlines andresearching English blackletter pamphlets from the 16th and 17thcenturies. Some of the latter fittingly concerned plague, such as the remarkablepamphlet attributed to Thomas Dekker—The Wonderfull yeare. 1602. Wherein isshewed the picture of London, lying sicke of the Plague. Through prose andpoetry, The Wonderfull yeare navigates that earlier mirabilis annus,as Dekker calls it, ranging from Queen Elizabeth’s death to the onslaught ofwidespread illness, by “tell[ing] only of the chances, changes, and strangeshapes that his Protean Climactericall year hath metamorphosed himselfe into.”

Thesecond full-length poetry title from Los Angeles-based poet Kate Bolton Bonnici,following

Night Burial

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for LiteraryPublishing, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

A True & Just Record

(Norwich UK: Boiler House Press, 2023), a collection originally prompted by andthrough the author’s interest in researching 16th and 17thcentury pamphlets during a period of time that quickly fell into the onset andinfluence of Covid-19 lockdowns. “Late March 2020,” Bonnici writes in herintroduction, “Witch Stichomythia: Chances, Changes, & Strange Shapes,” “I triedover the phone to help my grandmother—97, already living alone, and nowentirely isolated due to COVID-19 restrictions—figure out how to operate a laptopcomputer so that she could send emails and read the news online. Meanwhile inmy own reading, I toggled between doomscrolling hyper-current headlines andresearching English blackletter pamphlets from the 16th and 17thcenturies. Some of the latter fittingly concerned plague, such as the remarkablepamphlet attributed to Thomas Dekker—The Wonderfull yeare. 1602. Wherein isshewed the picture of London, lying sicke of the Plague. Through prose andpoetry, The Wonderfull yeare navigates that earlier mirabilis annus,as Dekker calls it, ranging from Queen Elizabeth’s death to the onslaught ofwidespread illness, by “tell[ing] only of the chances, changes, and strangeshapes that his Protean Climactericall year hath metamorphosed himselfe into.”Composedout of twenty-four poems, each piece in A True & Just Record unfoldsand expands, akin to the ripples of water from a pebble thrown into a lake,offering rings upon further rings beyond where the piece might have begun. “LittleRed Cap holds a lesson / on endings.” she writes, as part of the poem “Story ofGrandmother.” The narratives of many of her poems are pulled, spread apart andstitched from a multitude of threads, stitching together dire warnings with wisdoms,concerns and seemingly-impossible questions. “Imprimis,” she writes, invokinga sequence of firsts as part of the poem “Upon Information, Belief,” one of thefew poems in the collection under a page in length, “a painting of Mary &Jesus hosts the Three Living & the / Three Dead. / Imprimis, do youknow the evening prayer for getting my kid to bed?” Bonnici focuses herattentions in this collection on a conversation around the English witch trialsand a sequence of women through archival texts, weaving medieval language andtext from a variety of pamphlets into poems such as “Joan Cason: Executed forInvocation, 1586,” “Elizabeth Fraunces: Executed for Witchcraft, April 1579,” “ElizabethSawyer: Executed for Witchcraft on Thursday, April 19, 1621,” “Joan of Arc:Third Public Session, February 24, 1431” and “Elizabeth Stile: Executed forWitchcraft, 1579.” Connecting those isolations and those readings, she turns thecombination into a response that can’t help come through as writing, as sheoffers in a further part of her introduction:

Reading sometimes turns to writing when one wantscommunion. For writing begins, as Michel de Certeau explains, in loss. This losslies not only in the impossible distance between presence and sign. Writing beginsin want, which means both lack and desire. Writing into the want of and forcommunion (with far-away family, long-ago literature, past and presentscholarship) necessitates chances, changes, strange shapes.

Itis curious to see Bonnici examine the threads of that particular mirabilisannus, that “marvelous year,” given the related (or opposing) phrase utilizedby Queen Elizabeth II, “annus horribilis,” or “horrible year,” offeredas part of her Ruby Jubilee speech in November 1992, referencing the previouscalendar year across the Royal Household. Just as the first Queen Elizabeth ofEngland died during that earlier period, so, too, her contemporary namesake,who fell ill and died during the Covid-era (just beyond the temporal boundariesof this particular collection, I would presume), which do make a curiouscorrelation between eras. “The Wonderfull yeare is a pamphlet of princes& plague,” Bonnici writes, near the end of the collection, “all the waysone can be / worm-written written in blackletter (font & as to the law—whatis) // how some come from the maw of disease & others— […].”

Thereare elements of this particular work comparable to the work of Philadelphiapoet Pattie McCarthy, also known for folding in medieval language, as well as focusingon women of that era, from mothering to childbirth to healthcare (or what passedfor such during those times) [see my review of her 2021 collection wifthinghere]. Bonnici, in her way, approaches her collection from two different tethers:the language and content of medieval pamphlets around the witch trials andplague, and contemporary considerations through the Covid-era, acknowledgingthe wisdom of grandmothers, specifically her own, across the other end of thattelephone line. Whatever medieval implications might run through thecollection, the book opens and closes with grandmothers, framed against allelse that may exist within. As she writes as part of the poem “Story ofGrandmother,” a piece very close to the opening:

which means speaking thebody of an old wives’

tale, the one where thewitch

spun is a girl, twelve,spinning herself this claim: witch,

which is what opens theart

of want, the audacity todemand: sheep, wealth, wife,

a promise if she would fyrsteconsent. But spell love with blood,

and the bargained-forbreaks down (learned

once desire’s

been given to) […]

March 12, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joelle Barron

Joelle Barron is an award-winning poetand writer living and relying on the Traditional Territories of theAnishinabewaki of Treaty 3 and the Métis people (Fort Frances, ON). Their firstpoetry collection, Ritual Lights (icehouse poetry, 2018), was nominated for theGerald Lampert Memorial Award. In 2019, they were a finalist for the DayneOgilvie Prize for Emerging LGBTQ2S+ Writers. Barron’s poetry has appeared in ARCPoetry Magazine, CV2, EVENT Magazine, The New Quarterly,and many other Canadian literary publications. They live with their daughter.

1 - How did your first book changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

· My first book changed my life in that it connected me topeople who I never would have otherwise known, and it gave me a place in theworld of Canadian poetry. I think with this second book I’m more confident inmy voice and point of view, with similar themes of queerness and isolation buta more positive vibe overall. I wanted to write a book of love poems this time,because they are my favourite poems to read.

2 - How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

· I started writing poems in early childhood. I don’t reallyknow why; I have just always gravitated to writing as a form ofself-expression. My cousin—who was like a sister to me—died suddenly when I was13, and in the process of going through her things, I found that she wrotepoetry. I began writing poems to process her death, and I’ve never reallystopped.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

· I am extremely slow to start anything. Thinking about doingthe thing is a big part of doing the thing for me. What I love about writingpoetry is that, initially, it’s easier not to overthink it than with prose.Typically, the final product looks very different than the initial attempt,because I never start off imposing any sort of form or structure to a piece;that’s part of the editing process for me.

4 - Where does a poem or work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

· A poem usually begins with an image, or a line. Usually thetitle; like, what would a poem with the title “Your Wife is a Cryptid” beabout? It sort of shapes itself from there. I don’t usually start writing witha whole book in mind, but I follow whatever themes naturally emerge.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

· I live in a rural area so I don’t get the opportunity to domany readings. I get super nervous for readings but I do always enjoy them.Workshopping is definitely key to my process, and I really love to share mywork in that capacity.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

· This is a hard question for me to answer because I amautistic and part of that for me is that I am a very literal person. I don’tthink I’m trying to answer any questions with my work; I write because peopletypically understand me better through writing than through spokencommunication. So for the most part, I am writing to connect, and to feel lessalone in the world.

7 – What do you see the current roleof the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

· I think the role of writers is to connect people. There’ssomething so potent about seeing something you’ve always felt described withlanguage. Or understanding something you’ve never felt because it’s describedso adeptly.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

· Essential! I can’t say I’ve ever found working with aneditor to be difficult. I am grateful for all of the editors in my life.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

· The best writing advice I’ve been given is just to do it,regardless of how badly you feel about it or how hard you’re tempted to be onyourself. The best general life advice I’ve been given is don’t be in arelationship with someone who won’t dance with you at a wedding.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

· Fiction is harder than poetry because you have to keep holdof so many threads. My poetry is narrative, but you can only do so much in apoem. The appeal of fiction is that it gives you a lot more space to tell astory.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

· I get up in the morning about an hour before my daughterand read. Reading is an important part of my writing process, and I find it alot more difficult to access that “writer” part of my brain if I’m not readinga lot. It’s harder to have a routine around writing, being a busy singleparent. When I do write, I like to sit down for at least a few hours, in theevening or on the weekend.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

· I walk the dog. Moving my body (without the distraction ofmusic or a podcast) usually shakes things loose. I also re-read works that Iknow inspire me and make me want to keep trying.

13 - What was your last Hallowe'encostume?

· Mary Jane Watson.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

· All of the above for sure. Literally anything can (andshould?) be poetry.

15 - What other writers or writingsare important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

· This would be an extremely long list if I mentioned all ofthe writers whose work is important to me, so I am just going to mention my twoclose friends and editors, Ruth Daniell and Ellie Sawatzky. Brilliant poets whoinspire me and make me a better poet. Also, I wouldn’t be a poet without Rhea Tregebov.

16 - What would you like to do thatyou haven't yet done?

· Run across a windy moor in some sort of Victoriannightgown.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

· In another life, I would be a midwife for sure. It’s reallyhard to imagine what I would have done if not writing. It’s one of the fewthings I’ve ever felt sure about.

18 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

· Writing just always made me happy. I always loved to read,and that made me want to write stories of my own.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

· Book: Like a Beggar by Ellen Bass. Movie: Anatomy of a Fall.

20 - What are you currently workingon?

· I’m about half done the first draft of a novel.

March 11, 2024

Rosa Alcalá, YOU: poems

You, Supplicant

Over sashimi tostados andchelas, you tell your girlfriends about the time you kneeled on the carpetedstairs that led to the bedroom of the guy who dumped you, pleading. O, his longhair—his thinness—like Jesus! They said they couldn’t see it. “You, for a man,begging?” And how his roommate gently lifted you to your feet, an act ofkindness like so many meted out in those days by men adjacent to another man’sdestruction. He was trying to pull you from the image of yourself, not asbeautiful but as a supplicant before beauty. A penitent whose suffering was thedeep and persistent condition of being a woman. It was, like dictatorship, likeFirst Communion, a perversion. You didn’t say this to your girlfriends. You movedon to translation problems, and your humiliations remained fuzzy backdrops,like bookcases in author photos.

Thefourth full-length collection by Texas-based poet Rosa Alcalá is

YOU: poems

(Minneapolis MN: Coffee House Press, 2024), “a collection of prose poetryexploring the intergenerational inheritance of gendered violence.” In astriking assemblage of lyric scenes composed via a suite of hefty prose poems, Alcaláwrites on age and of distance, gendered violence and teenaged exploration, focusingon points along the path from child to young woman to becoming and being the motherof a young daughter. “What I mean to say is that this book is still about mymother,” she writes, as part of the opening poem, “How It Started, How It’sGoing {An Introduction},” “that in the absence of her I mothered myself allover again with worry, / which is how I mother. // I spoke to myself, the onlyrecourse when you’re / invisible.” Alcalá composes her poems through anaccumulation of direct statements that unfold, unfurl, each sentence anothercard placed, face up, on the table. She is showing you her cards, more oftenthan not as a warning. “Everything was lies,” she writes, as part of the poem “YouLie,” “and there was nothing / to keep you from your own fabrications, noeternal fire.” And then, how to warn her daughter without gifting her a newtrauma; how to protect without offering frightening tales of what could happen,or what had happened to her.

Thefourth full-length collection by Texas-based poet Rosa Alcalá is

YOU: poems