Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 56

April 19, 2024

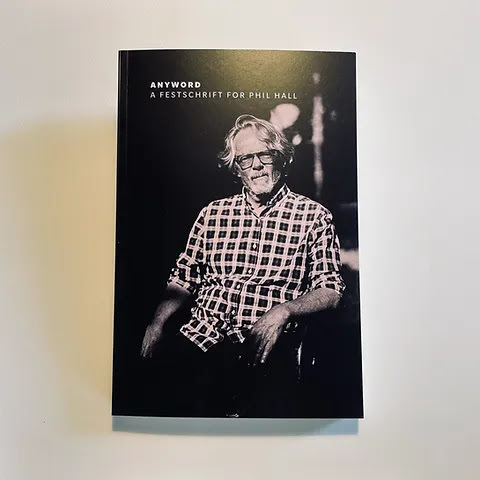

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik

It must be noted thatHall is one of the most widely and deeply read people I know. Years after hewon the Governor General’s Award, he told me that, “It’s very, very difficultto recognize a good work.” Moreover, Hall has a Master’s degree which hecompleted at the University of Windsor in the 1970s. No small feat, consideringHall was the first person in his family to finish high school. When I askedHall why he didn’t pursue a PhD (which he’d considered) he said, “Because I didn’twant it to dry me out.”

The idea for thisFestschrift was inspired in 2021 by the publishing efforts of the inimitablepolymath Nick Drumbolis and his remarkable imprint LETTERS. And though thisFestschrift is a gathering of writings for Hall as he turns 70, it is not abirthday party. It is an opportunity to give thanks for the years of steadyfriendship, mentorship, and work that he has provided. (Mark Goldstein, “Preface”)

I’mnot usually in the habit of reviewing a collection I have work in, but recentlya Canadian contemporary said they didn’t know what a “festschrift” was, sothought that prompt enough to discuss the recent

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL

, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik (Toronto ON: BeautifulOutlaw Press, 2024). Unlike the more formal essay series produced by, say, Guernica Editions (another essential grouping of responses), the literary festschriftallows for more of a range of responses-as-celebration, from the critical tothe creative and all between, from essays and interviews to small memoirpieces, poems and photographs.

I’mnot usually in the habit of reviewing a collection I have work in, but recentlya Canadian contemporary said they didn’t know what a “festschrift” was, sothought that prompt enough to discuss the recent

ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL

, eds. Mark Goldstein and Jaclyn Piudik (Toronto ON: BeautifulOutlaw Press, 2024). Unlike the more formal essay series produced by, say, Guernica Editions (another essential grouping of responses), the literary festschriftallows for more of a range of responses-as-celebration, from the critical tothe creative and all between, from essays and interviews to small memoirpieces, poems and photographs.Festschriftsproduced by a trade publisher do occasionally (very occasionally) emerge, butover the past few decades in Canadian writing, at least, it had been thejournals doing the bulk of this kind of work, with a variety of special issuesthrough The Capilano Review focusing on works by Robin Blaser, GeorgeStanley [see my review of such here], Sharon Thesen [see my review of such here] and George Bowering, among others, or Open Letter: A Canadian Journalof Writing and Theory (1965-2013), a journal that included specialfestschrift issues on bpNichol, Steve McCaffery [see my review of such here],Barbara Godard [see my review of such here] and Ray Ellenwood, not to mention avariety of other journals over the years that have less frequently featuredspecial issues on particular writers, whether Arc Poetry Magazine onErín Moure, Prairie Fire on Dennis Cooley or The Chicago Reviewon Lisa Robertson [see my review of such here], etcetera. Given how far the festschriftseems to have fallen by the wayside (mainly through a slow decrease ofproper publisher funding and that 1990s drop-off in library funding, whichreduced their purchasing power), I began producing a series of similarchapbook-sized festschrift publications during the Covid-era throughabove/ground press (I thought the Covid period could use some increased positive)—the “Report from the Society” series—with more than a dozen published volumesto-date, which also includes one on the work of Phil Hall (a reworked versionof Susan Gillis’ piece from mine appears in this current collection).

Theremight be those who recall

A Trip Around McFadden

(Toronto ON: The FrontPress/Proper Tales Press, 2010), the festschrift produced by Stuart Ross and JimSmith to celebrate David W. McFadden’s 70th birthday, or thecombined four hundredth issue of 1cent/thirteenth issue of news notes thatjwcurry produced on the work of Judith Copithorne (“for Judith with love”) [see my review of such here], but how many might recall

Raging Like a Fire: A Celebration of Irving Layton

(Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1993), thefestschrift edited by Henry Beissel and Joy Bennett? There are probably others,naturally, that I’m either unaware of, or simply can’t recall at the moment,but either way, there simply aren’t as many out there as should be. Volumessuch as these are important parts of literary conversation and acknowledgement(as are volumes of selected poems, something that occurs far less since the GovernorGeneral’s Award declared them ineligible for consideration back in the late1990s), none of which is occurring nearly enough, so a volume on award-winning Perth, Ontario poet, critic, editor, mentor and teacher Phil Hall, especially one sobrilliantly and thoroughly done, becomes an essential commodity.

Theremight be those who recall

A Trip Around McFadden

(Toronto ON: The FrontPress/Proper Tales Press, 2010), the festschrift produced by Stuart Ross and JimSmith to celebrate David W. McFadden’s 70th birthday, or thecombined four hundredth issue of 1cent/thirteenth issue of news notes thatjwcurry produced on the work of Judith Copithorne (“for Judith with love”) [see my review of such here], but how many might recall

Raging Like a Fire: A Celebration of Irving Layton

(Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1993), thefestschrift edited by Henry Beissel and Joy Bennett? There are probably others,naturally, that I’m either unaware of, or simply can’t recall at the moment,but either way, there simply aren’t as many out there as should be. Volumessuch as these are important parts of literary conversation and acknowledgement(as are volumes of selected poems, something that occurs far less since the GovernorGeneral’s Award declared them ineligible for consideration back in the late1990s), none of which is occurring nearly enough, so a volume on award-winning Perth, Ontario poet, critic, editor, mentor and teacher Phil Hall, especially one sobrilliantly and thoroughly done, becomes an essential commodity. Inmany ways, one can’t get much better than the short essay “Landscapes,” by Br.Lawrence Morey, a contributor who lives as a Trappist monk at the monastery ofGethsemani in Kentucky, that opens: “I first became aware of Phil Hall’sexistence when I was in grade 9 and he was in grade 10. I had taken out thebook Cariboo Horses by Al Purdy from the school library, which I loved. Thosewere the days in which you would write your name in the back of the book on asmall, pasted-in form, along with the due date, which corresponded to a card inthe librarian’s files. In front of my name on the form, I saw the name PhilHall. I knew Phil to see him, but didn’t dare approach him, since I was a mere9th grader and he lived at the exalted level of the 10thgrade.” This particular perspective on Hall’s ongoing work is wonderful (andMorey’s biographical detail, itself, provides a curious insight into Hall’s Gethsemani sequence), as Morey writes, later on:

Though poetry is Phil’s main medium, he also loves tomake quirky sculptures out of found objects, bottle caps, paperclips, and otherthings. Like the work of Kurt Schwitters, his sculptures grow like livingcreatures. His journals are a mixture of writing, drawing, and pasted words andimages. I think this reflects his working methods beautifully. In everything hedoes, he takes disparate pieces of things, letters, words, phrases, sequences,and molds them into something new, something surprising and revelatory.

Overthe past decade, Toronto poet, editor, critic, publisher and book designer MarkGoldstein has evolved into one of Hall’s most thoroughly-considered supportersand critics, having now produced three full-length collections by Hall throughhis Beautiful Outlaw Press—Toward a Blacker Ardour (2021), The AshBell (2022) and Vallejo’s Marrow (2024)—as well as a chapbook (Essayon Legend, 2014) and postcard (Rampant, 2022) in small editions. Producedand co-edited by Goldstein, ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL may be wonderfullyexpansive and even exhaustive, but it should be noted that his own contributionsinclude the essay “A Maker’s Dozen: from Eighteen Poems to Killdeer,”a whopping sixty-six page essay that examines, as he writes at the offset, “PhilHall’s published body of work from 1973 to 2011. With a focus on form (as wellas syntax and subject), I will investigate Hall’s line through thirteen tradeeditions and how it changed over the nearly forty-year span since he first sawhis work published.” Living writers, especially those still active and engaged,are rarely provided such thorough, thoughtful examination, and Goldstein shouldbe commended for not only this piece, but his ongoing critical work, whichitself is provided not nearly as much attention as it deserves [see my reviewof his 2021 Part Thief, Part Carpenter: SELECTED POETRY, ESSAYS, AND INTERVIEWS ON APPROPRIATION AND TRANSLATION, produced through Beautiful Outlaw as well, here]. As Goldstein writes as part of his lengthy essay:

To be clear, by employing the term poetic form, I ampointing to the structural and organizational patterns of a poem, including its(subtle or more obvious) rhyme scheme, meter, stanza structure, lineation,sentence structure, and other elements that shape its overall configuration anddesign on the page. In light of free verse, poetic form has played asignificant role in the development of contemporary poetry, as poets like Hallhave experimented with new forms and pushed the boundaries of traditionalstructures to create highly readable yet neoteric and innovative styles of writing.

As I’ll show in this essay, Hall’s sense of form wasfirst influenced by both traditional and modern forms of poetry found withinthe canon, and later it was increasingly written in concert and conversationwith contemporary and postmodern poetry itself. Hall is a careful reader of alltypes of poetry (and literature) and has thought deeply about form. He has consideredhis own use of free verse and, rather than adhering to accepted rules or anti-rulesof meter and rhyme – whether outmoded or contemporary – he has, over time,experimented with myriad structures and patterns in his poetic line. This haslikely afforded Hall a greater flexibility in expressing his ideas and emotionsin poetry. This has also pushed him to develop new poetic forms of his owndesign, as well adapt or redeploy older ones – such as the prose poem and the haibun– to his own unique use. Moreover, Hall has slowly gravitated toward anexpansive use of his own idiosyncratic forms and sub-forms which are drawn fromthe dictates and necessities of his own poetry’s deployment.

Against a more prescribed approach to form, Hall hassaid, “What are we making? Sausage?”

Atmore than three hundred pages and twenty-six contributors, ANYWORD: AFESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL includes poems, essays, reminiscences andinterviews by George Bowering, Erín Moure, Don McKay, Sandra Ridley, GeorgeStanley, Steven Ross Smith, Tom Dilworth, Cameron Anstee, Br. Lawrence Morey,Mark Goldstein, Susan Gillis, myself, luke hathaway, Nicole Markotić, Fred Wah,Louis Cabri, Karl Jirgens, Arthur Craven, Chris Turnbull, Ali Blythe, JohnSteffler, Pearl Pirie, Donald Winkler, Ronna Bloom, Andrew Vaisius and AngelaCarr, as well as an array of photographs of Hall over the years—including anearly 1980s photo at Michael McNamara’s apartment on page 272 where he looksthe spitting image of a late 2000’s former Ottawa poet Jesse Patrick Ferguson—anda healthy bibliography of Hall’s published work. The responses run the gamut fromthe personal to the intimate to the critical and the celebratory (with most incorporatingmost if not all of those features), many of which I’m still working my slow waythrough reading [the video of the zoom-launch for the collection, which included readings by Hall, Moure, Blythe, Ridley and myself, is now online]. AsAngela Carr writes to introduce the first of two interviews she conducted withHall: “Phil Hall is to poetry in Canada what style is to reason.” The essay byPearl Pirie is easily the strongest critical work I’ve seen by her to date, andboth Moure and Blythe offer pieces that delight in their scale and intimatescope. The collected pieces offer such appreciation and delight, attempting toshare or discern the shapes of how Hall reacts, presents and writes, and boththe generosity and curiosity of a writer decades-deep into an appreciation ofhow the poem moves, or might move, or could move. It becomes hard to highlightmuch in this collection without wanting to reproduce whole pages, which I won’tdo here, but I shall leave the last words to Hall himself, out of one of thoseinterviews conducted by Angela Carr, where he speaks of the late Stan Draglandin such a way that it could be applied to Hall and his work, as well:

It is a style (one thingreminds me of another) that can easily go wrong. If a writer seems to bepadding, if a writer seems to be flailing or name-dropping, if the examplesseem too carefully or metaphorically fetched. But Stan makes in his essays eachstep of his argument seem inevitable, so that we say, “Of course!” Then, at theend of an essay by him there’s that feeling of having participated in a dance –& having gotten somewhere unexpected, wider.

It has a lot to do withtexture. And character. And with a widening of community. During the time I knewStan, from 1984 until this year, he moved toward an on-rush of critical herding& gathering that can be breathtaking to read. Breathtaking in its humility& faith. He had a deep faith in us. He believed that we, his friends, wereworth it – worth every quirky added bit – and worth every word.

April 18, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Allison Thung

Allison Thung is a Singaporean poet and project manager. She is the authorof Reacquaint (kith books, 2024) and the forthcoming Things Ican only say in poems about/to an unspecified ‘you’ (Hem Press,2025). Her poetry has been published in ANMLY, Heavy Feather Review,Cease, Cows, The Daily Drunk, and elsewhere, and nominated for Bestof the Net, Best Microfiction, and Best Small Fictions.Allison reads poetry for ANMLY. Find her on Twitter and Instagram @poetrybyallison, or at www.allisonthung.com.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

Although it’s only beena little over a month since its official release, Reacquaint (kith books, 2024) hasbeen several years in the making, plus I’ve known since I was fourteen that Iwanted to someday see my words in print, so it’s definitely felt like alongtime dream fulfilled. More practically, it is tangible assurance that mywords have a place in the world; a reminder to keep writing.

2 - How did you cometo poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I actually started writing prose before Ifound my way to poetry. Growing up, I mostly read short story collections,young adult novels, and comic books, and so I naturally tended towards fictionwhen I began writing. It wasn’t until I returned to the written word after ahiatus of eight years, saturated with emotions I couldn’t fully access viaprose, that poetry became my genre of choice.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It really depends. Reacquaint took memaybe 18 months, but that’s because it started as standalone pieces that I laterbrought together to create a coherent manuscript and narrative. Things I canonly say in poems about/to an unspecified 'you', which is forthcoming with HemPress in 2025, as well as two other chapbook manuscripts I have out onsubmission, were each completed within a few months; the poems for those werewritten with the inherent understanding that they were meant to be part oflarger manuscripts.

Save for two or three, I don’t think I’veever significantly changed any poem between their first and final drafts. Mostof the time, my poems appear close to their final form, and editing focuses onflow, grammar, and specific word choices.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Poem: Often from the middle of a sentence Iam saying to someone else, which I imagine is kind of annoying for the otherperson, because then I stop talking to make a note. Sometimes from a longtime ruminationsuddenly become coherent and distinct from the rest of the noise inside my head.Occasionally from a dream.

Approach: These days I prefer to work on a“book” from the start, though it’s important to me that the individual poemscan stand on their own. That said, I do still write standalone pieces thatdon’t fit into a larger theme if I think them necessary to exist.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings, but it’s something Ireserve for after the work has been officially published. My creative process ismostly an exercise in solitude, save for the very occasional times I sharepieces about which I have doubts, or for which I have particular affection,with trusted individuals.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

At its core, my poetryseeks greater meaning in the mundane, and to finally put into coherentsentences the many ruminations and emotions that bounce around inside myhead. I spent much of my life worryingthat I had lived too underwhelmingly for me to have something worth writingabout, and every poem is a much-needed reminder that it’s less about whatyou’ve experienced, and more about how you perceive and process saidexperiences.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t know if “role” is the word I’d use.Maybe concerns? But to answer the question, I think it would vary greatly basedon the type of writer you are. A journalist, for example, would have verydifferent concerns from a novelist.

At the personal level, I write to tellstories, make sense of my interior and exterior worlds, and defy mortality insome small way.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential and appreciated.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Forgive yourself”, specifically said to me. It’snot something I’m good at.

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I tend to alternate between phases of unshakeablewriter’s block and intense creativity, and my writing practices—I wouldn’t usethe term routine—differ accordingly. In the former phase, I focus on taking detailednotes whenever ideas or lines come to me; in the latter, I try to draftsomething daily, even if it’s just a few words.

Generally, when I can write, I prefersilence, solitude, and to be at my desk on my own laptop.

11 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Talking to other people, exercising, andgetting out of the house can be helpful with idea generation, but I’ve come toaccept that there isn’t very much I can do to affect the larger cycle that Imentioned in my response to the previous question.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Homemade lotus root or watercress soup,bubbling away in the slow cooker until its aroma permeates every inch of thehouse.

13 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Neither nature nor music feature heavily inthe work itself, nor do I tend to create in their midst—I’m very much a poetwho prefers to write indoors at my desk, in absolute silence—but both areprimary sources of inspiration.

14 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

Iconsider the work of Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Richard Siken, and Chen Chen to beutterly essential. And then outside of the literary world, I have a lot of loveand respect for Hozier’s lyricism and how he’s able to embody an entire worldin just a few lines of lyrics.

15 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d love to travel through Europe for a yearor so, and then settle down in Ireland for a couple. Less ambitiously, I’d liketo meet and hang out with a capybara or a wallaby.

16 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Realistically, I’d probably still be aproject manager, which is my current day job. Unrealistically, I’d be anarchitect, lawyer, or singer-songwriter.

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s just what came most naturally to me wheneverI needed to express myself or make sense of the world, and brought me the most satisfaction/fulfilment.Throughout my life, I’ve tried and enjoyed various forms of creativity, includingart, craft, and music, but none of those have felt entirely “right” the waywriting does.

18 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Kerry Trautman’s Irregulars.

Film: I’m less a film and more a seriesperson, so let’s go with Grace and Frankie.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

I’m currently working on a hybrid chapbookmanuscript, and I’ve also got two more completed poetry chapbook manuscriptsout on submission.

April 17, 2024

Kim Trainor, A blueprint for survival: poems

327.45 ppm

I begin with 1972, year11,972 of the Holocene era, the year The Ecologist published ABlueprint for Survival to warn that we were running out of time. My mom ina yellow tank top and bell-bottom jeans grips my sister by her left hand, me bythe other. We’re dressed in identical play suits, apple-green sleeveless topsand sky-blue shorts. I’m barefoot, with a turquoise floral kerchief. I can feelthe heat baked into the granular sidewalk, grit under my toes. From the frontdoor of our house on east 56th, an entrance we never use except forguests, there’s a clear view of Mount Baker. We always take the side entrance—throughthe mudroom where my mom stands for hours by the hinged window, pinning laundrywith wooden pegs to the line, reeling it out to flap in the breeze, reeling it backagain, sterilized by the sun. The snap of white sheets folded into squares. A freshscoured smell of earth and wind. This is my earliest memory.

Writingfrom and through Delta, British Columbia and wildfire season while “charting along-distance relationship,” Kim Trainor’s fourth full-length collection is

A blueprint for survival: poems

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2024), a book-lengthpoem around climate crisis, fires and long-distance love, following hercollections Karyotype (London ON: Brick Books, 2015), Ledi (TorontoON: Book*hug 2018), and

A thin fire runs through me

(Fredericton NB:Icehouse poetry/Goose Lane Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here]. Furtheringher examination of the book-length lyric suite, A blueprint for survivalseems comparable Matt Rader’s FINE: Poems (NightwoodEditions, 2024) [see my review of such here] for their shared book-length BritishColumbia perspectives around climate crisis and wildfires, but with added layersof emotional urgency. As Trainor’s poem “Iridium,” set in the first section,includes: “I can’t read anymore. / There is no clear way. I will venture outalong white tracks. Mark ink / on green-ruled numbered pages. Lay down stripsof black carbon. Scatter / signals of plutonium and nitrogen, Tupperware, chickenbones, lead. / Absorb radionuclides. Take shelter. Mourn. Make fire. Write poems./ Conserve. Despair. Decay.”

Writingfrom and through Delta, British Columbia and wildfire season while “charting along-distance relationship,” Kim Trainor’s fourth full-length collection is

A blueprint for survival: poems

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2024), a book-lengthpoem around climate crisis, fires and long-distance love, following hercollections Karyotype (London ON: Brick Books, 2015), Ledi (TorontoON: Book*hug 2018), and

A thin fire runs through me

(Fredericton NB:Icehouse poetry/Goose Lane Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here]. Furtheringher examination of the book-length lyric suite, A blueprint for survivalseems comparable Matt Rader’s FINE: Poems (NightwoodEditions, 2024) [see my review of such here] for their shared book-length BritishColumbia perspectives around climate crisis and wildfires, but with added layersof emotional urgency. As Trainor’s poem “Iridium,” set in the first section,includes: “I can’t read anymore. / There is no clear way. I will venture outalong white tracks. Mark ink / on green-ruled numbered pages. Lay down stripsof black carbon. Scatter / signals of plutonium and nitrogen, Tupperware, chickenbones, lead. / Absorb radionuclides. Take shelter. Mourn. Make fire. Write poems./ Conserve. Despair. Decay.”Thereis a thickness to her lyric, writing undergrowth and foliage, of trees andscientific names. A few pages further into the first section, as the poem “PaperBirch” begins: “These are notes for a poem I meant to write in August, butpoetry / seemed very far away then. The BC wildfires smudged the shoreline / ofthe Saskatchewan—everything ash on the tongue, like cigarettes / or coffeedregs, and the sun a smoked pink disc. / I had not seen you for weeks except bySkype (I’ll strip for you, / you said, and you did) but now in fleshmeandering, / now talk, now silence, now climate change and / your research onthe Boreal.” There is something of the long poem combined with both the poeticdiary and book-length essay that Trainor offers in this collection,articulating crisis and climate but expanding into an agency of archival researchand illustrations; she writes asides and footnotes and prose stretches througha lyric framework in an impressive book-length package. This is a highly ambitiousand heartfelt collection, one that even provides echoes of the detailed lyricresearches of one such as Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris, attending to the bigidea through an accumulation of minute details. The scale of this volume isincredible. I don’t know how to begin.

April 16, 2024

today is Aoife's eighth birthday,

Our delightful wee imp turns eight years old today; how did that happen? She had a grand weekend as well, away two nights as part of her Embers camp, and home just in time for a birthday party on Sunday that saw fifteen young ladies run chaos throughout our house. Just what might the future bring?

Our delightful wee imp turns eight years old today; how did that happen? She had a grand weekend as well, away two nights as part of her Embers camp, and home just in time for a birthday party on Sunday that saw fifteen young ladies run chaos throughout our house. Just what might the future bring?April 15, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kit Dobson

Kit Dobson lives in Calgary, Treaty 7 territory, in southern Alberta.He is the author or editor of eight previous books, including

Malled:Deciphering Shopping in Canada

and

Field Notes on Listening

, one ofthe CBC’s top non-fiction books of 2022.

We Are Already Ghosts

, hisfirst novel, is scheduled to be published in May 2024.

Kit Dobson lives in Calgary, Treaty 7 territory, in southern Alberta.He is the author or editor of eight previous books, including

Malled:Deciphering Shopping in Canada

and

Field Notes on Listening

, one ofthe CBC’s top non-fiction books of 2022.

We Are Already Ghosts

, hisfirst novel, is scheduled to be published in May 2024.1 - How did your first book changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

My first book was an academic book, Transnational Canadas, published in 2009. It changed my life in many ways, first andforemost by showing me that I could actually see a book through to publication.That book still brings me the occasional note from readers, for which I amgrateful. My most recent writing has shifted toward creative work, so it’squite different. The most recent examples are my 2022 nonfiction book FieldNotes on Listening and my forthcoming first novel, We Are Already Ghosts.The work now feels very changed. I have the confidence of having seen otherprojects through, which is great, and I am continuing to challenge myself innew ways.

2 - How did you come to creativenon-fiction first, as opposed to, say, fiction or poetry?

Spending a lot of time in universityshaped my initial writing. So it’s shifting from academic writing that broughtme to creative non-fiction and then to other modes. My first creativenon-fiction book was Malled: Deciphering Shopping in Canada. I initiallythought that I was writing an academic book. It took a discerning reader to letme know that I was trying to fit a creative project into a critical frame – andthat it wasn’t working. With that book, it was a matter of shedding aprotective layer (my academic voice) in order to let that book be what itwanted to be. Fiction has been harder. My thinking was that I’ve read hundredsand hundreds of novels; I’ve written essays and criticism about dozens of them;maybe I could write one. Turns out it’s really hard, as any fiction writer cantell you. Having now endeavoured to complete a novel has enriched how I readand write about all of the fictional works that I encounter. I have tremendousrespect for anyone who manages to write a novel.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

It varies so much! I work on more thanone project at a time. That means that if I get stuck on one project, I canflip to working on another – until I get stuck again and make another shift.It’s a process that works for me. So the forthcoming novel has been about nineyears in the making, but in the middle of that I paused and wrote FieldNotes on Listening, which took about five years. I kept editing the novelwhen I got stuck with Field Notes in turn (and I have more projects inthe works, ones that I’ve kept working on in fragments). All of that is to saythat my writing is a slow, laborious, and at-times painful process. Firstdrafts look nothing like their final published forms. I have a notebook inwhich I scribble notes, plot timelines, do character sketches, organize ideas,and draft in longhand, then I rewrite drafts into my computer, then I take apause, then I print out drafts, scribble all over them, and then rewrite fromscratch on the computer all over again – multiple times, as necessary. It isnot a tidy process, but it is one that I am pretty happy with.

4 - Where does a work of prose usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

For whatever reason, the scale and scope of the book worksfor me. I tend to think in book-sized and book-shaped projects, for good or forill. I may put out some smaller pieces from that project along the way, but findthat I am always working on a book from the get-go.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

I enjoy doing some readings because I am concerned withfostering and building literary communities. Readings can be one way ofsupporting that process. But this question is perhaps a version of one that Ioften ask people who write, which is: do you prefer to write or to havewritten? That is to say, do you prefer the process or the product? While I dowrite because I have a goal of sharing an idea or of presenting an argument toreaders, if I am honest I prefer the process. There is nothing better for me thanbeing at home, at my desk (which is formerly my grandparents’ farmhouse diningtable), with a coffee, during a cold, snowy day, and writing for an hour ortwo. That’s the best. I do readings for the sake of community, friendship, andconversation – but my writerly self (who is rather an introvert at heart) ishappiest when writing.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My answer to this question will varyfrom project to project, but I am always thinking in terms of theory, society,and the political. In the broadest of terms, I concern myself with thinkingabout the world we live in, analyzing its shortcomings, and trying toarticulate how we might learn to think, see, listen, and live differently. Mypersonal goal is to leave my own little corner of the world a little bit betterwhen I go. I hope that I can do that. Whenever anyone tells me that they haveread a piece of mine, my answer is some version of “I hope that it was usefulfor you in some way.” I really do mean it. I don’t think that I am aparticularly interesting human, but I do think that we can have meaningfulconversations with each other through words. To me, that’s an amazing thing.The current questions are wide-ranging, but I am at this moment very concernedwith polarization and social fragmentation. The literary has a role to play inbridging between divides and I work in that spirit.

7 – What do you see the current roleof the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

Writers absolutely have a role to play in larger culture. Ihave been following the conversations about book bans and censorship withinterest lately. I taught a course on this subject this past year, one thatfeatured some of the most controversial books of the twentieth and twenty-firstcenturies. If books – and by extension writers – didn’t matter, then therewouldn’t be this intense energy being directed toward banning and censoringbooks. I’ve spent many years having to defend books and literary studiesagainst the charge of being boring or passé. These days it's the reverse. Republicansin the US are threatening literal burnings of books with LGBTQ+ and BIPOCcontent and similar attempts to ban books are afoot in Canada. To me, this signis one among very many that books continue to play a vital role in culture writlarge. Books matter as a way of sharing vital information and for formingcommunities. I am a passionate believer in the importance of literary works andI believe that this role is a good one – if fraught – for writers.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Editors are crucial. Anyone who wishes to write andbelieves that they do not need an editor is, in my view, not ready to be makingtheir work public. I say this because such a resistance means that the writer isnot ready to accept feedback and criticism (which, believe me, happens when onepublishes a book). The process can be difficult, yes, but it is essential. Igave the example already of a reader – who became my editor – who let me knowthat Malled wasn’t working because of the box into which I was trying toput that manuscript. That’s one example. The editor for my latest book is Naomi K. Lewis, who is a brilliant writer, reader, and editor whom I admiretremendously. Naomi’s insights were crucial, and I do my best to maintainpositive relationships with anyone who has ever served as an editor for any ofmy projects.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t fall in love with your ownwriting. That piece of advice was given to me by Judith Mitchell, the professorat the University of Victoria who taught the introduction to literary theoryseminar that I took more than a quarter-century ago. I was frustrated by thatadvice at first because I wanted every word to count. I realize now that it wasan invitation to the recognition that one can edit one’s work without worryingabout “losing” important or valuable words. Most of what I draft doesn’t seethe light of day – and that’s a good thing. Just because one has written asentence doesn’t mean one needs to keep that sentence. Let it go. Becoming lessprecious about my writing has been tremendously helpful.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (essays to creative non-fiction)? What do you see as theappeal?

My moving between genres has been anendeavour to respond to how best to share my arguments, ideas, or visions.Essays serve one kind of audience and creative non-fiction serves another. Myacademic training focused relatively little on thinking about audience, sothat’s something that I’ve been meditating on in depth recently. That’s not aslight against my mentors or my training; they taught me fantastic andwonderful things about how to think and how to exist in this world. I wouldn’tbe able to do the work without them. But I suppose that I wasn’t ready to learnto think in depth about audience until more recently. It’s been that shift inmy thinking about audience that has helped me to move between genres.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

I wish I had a routine! My daily lifeis moderately chaotic. My day begins with helping everyone in my household toget set for the day, walking the dog, and so on. I answer emails from mystudents first. I plan my teaching, I do my marking, I go to meetings. I keepscholarly tasks on campus moving along. I coordinate future plans, touch basewith fellow writers, colleagues, friends. On good days, I squeeze in somewriting early on (sometimes quite early). When deadlines start to loom, I dealwith them. I think it may be easier to think of my routine in terms of seasons:fall and winter I am typically doing all of those things that I just listed ata full-out sprint. Spring and summer I get more writing done, but it remains astruggle. I look forward to a time when I might be better able to calibrate myrhythms, but I haven’t managed it lately. I do insist, though, on takingweekends away from my desk. I’ve been through enough rounds of burnout in mylife to know that I need to maintain a level of balance. I have had cycles ofburnout that have taken years for me to recover from and I never want to findmyself there again. So self-care is also very important to me, as best as I canmanage it.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Inspiration is a fine word by me,partly because it is connected to breathing. I head to the woods and get abreath of fresh air. I go outdoors as much as I can and that is what grounds mypractice (literally and metaphorically). A good hike with a friend will do morefor me than any amount of trying to force my writing when I stall out.

13 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Pine, spruce, cedar. I am fussy aboutsmells. I am actually fussy about almost all sensory inputs. I cut the tags outof my shirts because they itch and I can only tolerate certain fabrics. Samefor smells. If it smells like a forest in Alberta or BC, then I can enjoy it.Otherwise I struggle with fragrance. Most fragrances tip me into a kind ofsensory overload. Same with loud noises and bad lighting. My partner (rightly)tells me that I am not the easiest human to deal with.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Books definitely come from books –that’s a cornerstone to my practice. But yes, books come from elsewhere too. FieldNotes on Listening came from other books, but also, and very importantly, thatbook came from the landscapes of Alberta, and northern Alberta in particular.That book is a result of over forty years of returning to the same landscapeand then slowly learning words that could attempt to convey that experience.Music, science, and visual art can inspire me in ways similar to books, but I’dreally like to emphasize the importance of returning to land and environment,especially in my most recent work. My previous non-fiction book, Malled,also involved being in specific spaces – in that case, each of the shoppingenvironments about which I was writing. I literally wrote the initial draft ofthe first chapter of that book in Calgary’s Chinook Centre mall on Boxing Day.

15 - What other writers or writingsare important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I am often asked what my favouritebook is. I thought for a very long time about this question before I settled onVirginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. It’s a novel that I return to everyfew years and I get something else out of it each time. My own novel is anattempt to mix stylistic elements of To the Lighthouse with bpNichol’s playful poetics in an Albertan setting. I have an extremely long list of keytexts in my life – touchstones to which I return and new books that devastateand inspire me – but maybe that’s a whole separate conversation.

16 - What would you like to do thatyou haven't yet done?

I would like to slow down. I couldcome up with a more zippy answers, but slowing down speaks to where I’m atright now. I return to this challenge periodically. One my commitments is to bein the forest as much as possible. Every summer for the last few years I havemanaged nearly a week of being fully off the grid, but it seems like a drop inthe bucket in an otherwise very busy life.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, it sure wouldn’t be anastronaut. (My friends know that I have a perhaps ill-founded antipathy towardsour celestial über-Menschen because they are always looking down on us.Besides, my eyesight isn’t nearly good enough.) I work at the University ofCalgary and so I am also a professor, or at least that’s my job title. I don’ttend to think of myself as a writer. Instead, I usually think of myself assomeone who writes. Back in the day I signed up to write the LSAT exam and to goto law school, but I don’t think that I would have been good at it. My baselinelevel of anxiety is too high for that profession.

18 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

Increasingly I will say that the best– or even the only – reason to write is that one couldn’t not write. Ithink that that’s my reason: I couldn’t not write. It’s a thing that I do. I doother things also, but I write because I couldn’t do otherwise.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’reBriefly Gorgeous is the most recent book that I read that absolutelyknocked me flat. What an amazing book. Sad, devastating, and beautiful. Icannot recommend it enough. The film Portrait de la jeune fille en feuis probably the last great film; its nuanced reworking of the story of Orpheusand Eurydice made it one of the most touching and simultaneouslyheart-wrenching films that I have seen in a long time. Both are not exactlyup-to-the-moment references, but I come to some things later than others do.

20 - What are you currently workingon?

With my novel We Are Already Ghosts set to bepublished in May, I am going to dedicate some of my energies to having thefollow-up conversations that that book may lead to, for a start. Behind thatbook I have several academic projects that I am working on, none of which arereally in such a state that I can say too much about them yet. But more thanany of those things, I am working on finding small cracks of time that mightallow me to slow down. I might never complete another novel, I don’t know(though I have one in the works). I am working on community, on relationships,and on figuring out how to become a better person. I’m a work-in-progressmyself, after all.

April 14, 2024

Sarah Burgoyne & Vi Khi Nao, Mechanophilia, Book 1

0 of two or three square miles

9 of tears striates across a river rewritten by a

7 city shape. A foolish pitch to cancel

4 my membership with loneliness.

9 Something hit our heads and tiptoed into cirrus

Clouds

4 while desolate rain memorized

4 imperfect geometries, letting fall

5 devastating isotopes of emotional indifference

9 in the same place. You, in pristine ditches, find

2 an absolute

3 tangle spreading apart

0 eyelids from dreams.

FromMontreal-based experimental poet Sarah Burgoyne & Iowa City-based Vietnamese-born poet and multi-genre writer Vi Khi Nao comes the collaborative

Mechanophilia, Book 1

(Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2023), produced through Stuart Ross’imprint, A Feed Dog Book. I’ve been an admirer of Burgoyne’s work for some time[see my review of her latest solo collection here], but hadn’t previously been aware of thework of Vi Khi Nao (although I’ve caught more than a couple of interviews she’s conducted, including this one with Sarah Burgoyne), the author of not only sixpoetry collections, a short story collection and a novel, but a priorcollaborative work, the novella Funeral, with Daisuke Shen (KernpunktPress, 2023). Mechanophilia, Book 1 is composed as the first of anongoing, potentially open-ended collaboration between the two, comparable to the two volumes of the “Continuations” series [see my review of the second volume here], composed as well via email, by Douglas Barbour and Sheila Murphy.It is interesting to get a sense of the crossing of vast, geographic distancesbetween these two writers, something articulated as well in a review of Nao’s prior collaboration, almost as though she is working to either chase or bridge anumber of solitudes.

FromMontreal-based experimental poet Sarah Burgoyne & Iowa City-based Vietnamese-born poet and multi-genre writer Vi Khi Nao comes the collaborative

Mechanophilia, Book 1

(Vancouver BC: Anvil Press, 2023), produced through Stuart Ross’imprint, A Feed Dog Book. I’ve been an admirer of Burgoyne’s work for some time[see my review of her latest solo collection here], but hadn’t previously been aware of thework of Vi Khi Nao (although I’ve caught more than a couple of interviews she’s conducted, including this one with Sarah Burgoyne), the author of not only sixpoetry collections, a short story collection and a novel, but a priorcollaborative work, the novella Funeral, with Daisuke Shen (KernpunktPress, 2023). Mechanophilia, Book 1 is composed as the first of anongoing, potentially open-ended collaboration between the two, comparable to the two volumes of the “Continuations” series [see my review of the second volume here], composed as well via email, by Douglas Barbour and Sheila Murphy.It is interesting to get a sense of the crossing of vast, geographic distancesbetween these two writers, something articulated as well in a review of Nao’s prior collaboration, almost as though she is working to either chase or bridge anumber of solitudes.Mechanophilia, Book 1 is composed as a continuous,book-length piece across more than a hundred pages, following a numberingsystem of lines that accumulate, following the numerical structure of pi. A “collaborativeepic,” as the press release offers, “by American poet Vi Khi Nao and Canadianpoet Sarah Burgoyne (who have never met) that follows the omniscient conversationsand complaints of ad hoc biblical characters as they attempt to make sense ofthemselves on an ordered, disordered planet.” The numerical system is reminiscent,slightly, of those grid-poems that Canadian Modernist poet Wilfred Watson(1911-1998), a poet better known for being married to legendary prose writerSheila Watson (1909-1998) than for his own work, spent his career focused upon.Through Burgoyne and Nao, there is the suggestion of the call and response,threads that myriad and move beyond the two distinct voices that mingle, weaveand interweave, blending into each other as a separate sequence of a combinedsingle voice. Through these two, references weave into and around each other,changing shape and texture as the poem furthers. Part of what becomesinteresting through such a project is not only how such a project might progressacross the further three volumes, but how the individual works of these twomight adapt as well. As their “EPILOGUE” writes:

Alas, we have lost heart.Or so it seems after three thousand and two lines of poetry (pi to 3,000 decimalplaces). But this is merely the first of many (infinite) volumes. To write thisbook, we foolishly cancelled our memberships with loneliness and wrote acrosscountries, in virtual high seas, daily, for years, spooling out line after lineof ancient questions, complaints, please, declarations, each taking a line, poets’do-si-do. While we wrote, we got to know each other for the first time. We chattedabout our lives, our loves, our families, our pain, our pasts, what we wereeating, cooking, planting, not planting, buying, teaching, reading, painting,who was visiting, who was publishing, and whether the heart is really locatedunder the floorboards, as Poe suggested. (It is.) This side chat, perhaps the mostprecious document of all, maps an epistolary acquaintance, charts a friendshipin the making, and Mechanophilia is its shadow, its dream, itsunder-the-floorboards heart, friendship’s supraliminality. We think this is whyit gets funnier as it moves along. Like books of the Bible, Mechanophiliaat its current stage comprises four books, each corresponding to a few thousanddigits of pi. This project will continue until we die. This is the first book. Agenesis in more ways than one.

April 13, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Amy Mattes

Amy Mattes loves PNW rainy days powered by too much coffee and writing toepic movie scores. She has a vintage suitcase full of old journals and a heartshaped rock collection. She is inspired by the grit and beauty of human connection,often drawing story out of struggles with identity, sexuality, grief andaddiction. She holds an Anti-Oppressive Social Work Degree from the Universityof Victoria and is currently enrolled in the Bachelor of Arts School ofCreative Writing at Vancouver Island University. Amy is represented by Carolyn Forde of Transatlantic Agency and is currently writing her second noveland raising a child. She holds gratitude for the Snuneymuxw First Nation whoseunceded territory she lives, learns and loves on.

1 - How did your first book change your life?How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

Late September is my fictionalized story thatbegged to be written. There was a lot of healing for me in having it come tofruition. It is a dream come true. A dream I worked at, but I don’t think Iever want to go back into the headspace of a 19-year-old character again. Formy work in progress, the main female lead is closer to my age now. There is awisdom that comes with ageing that I couldn’t have tapped into in my current writinguntil I’d been through it.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, asopposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

My novel contains a lot of non-fiction experiencesand observations woven in and embellished or mutated and I’ve been writing whatI call ‘scrap’ poetry my whole life. For some reason calling myself a poetfeels superfluous, though I am starting to take more ownership of that term. Alot of my note taking starts out as poetry. Writing a fiction novel, however, wasjust something I always felt that I needed to make happen. I believed in thestory that was developing and kept on with it, despite a gap where I went touniversity. Writing a fiction novel was what I always wanted to accomplish, nowI feel like the possibilities are open ended.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

I am a mix of all those. Some works come and Ihave to get them down immediately and others I sit with. My drafts usuallymaintain their bones. I free write and journal a lot and then move to mycomputer. I try to make sure I really live outside of my writing time, doing sogives me more passion when I get the opportunity to craft.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

So far, I’ve started both books from thebeginning, though they don’t take a linear trajectory after that. My firstnovel I wrote the start, then the end, then the middle over the span of sixyears. My second, I’ve promised myself won’t take that long, and I am tryingsomething different with perspectives and timelines, so I am jumping aroundeven more.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter toyour creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I wouldn’t say readings are part of mycreative process, but I do enjoy them. They help me develop a dialogue withpeople who care about the same things I do and being given graciousopportunities to read from my work feels cathartic, though I’m learning theyneed to be sustainably planned.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are?

My debut novel is about the coming-of-agethemes I experienced like grief, addiction, and sexuality and I look to otherauthors to read the ones I haven’t like immigration, and racism. I think thequestions we ask are still the basics of who are we? What unites us? What hurtsus and divides us? I really valueconnection and listening, and I imagine most of my work will cover personalgrowth in one way or another.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

Like any artist, a writer reflects life. Ithink part of that role is a responsibility to be political and just andcurrent. To be more than tolerant, to teach and to learn. A writer should aimto channel and articulate issues and values.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Patients wouldn’t survive to tell a good storyif their surgeons didn’t perform their best. The editors I’ve worked with havefixed me up, made me a better writer. Got me exercising my writerly muscles.Editing is a big and miraculous undertaking. I’m enthralled by their abilitiesto see within.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you'veheard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Most thing aren’t worth anger.

10 - How easy has it been for you to movebetween genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

As I said before poetry has always been therefor me, but it’s felt less tangible. I’m taking some poetry classes right nowand since my days are busy, I love that it gives me the chance to read andwrite in shorter spurts, but with the same command.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tendto keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

On days when I don’t have my son, I drinkcoffee leisurely in bed while I think, no phone, no book. Then I will write atmy desk for an hour or so before heading to work. When I do have him, life ismore hectic, but I always carry a notebook everywhere and will write on myphone. I’ll puts words down wherever and then try to amalgamate them in theevenings when he’s asleep.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where doyou turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I take my dog for a walk in the rainforest toquiet things down. I usually focus my thoughts on where I am stuck, and I will problem-solveand breathe and usually get the answers I’m looking for. If that doesn’t do thetrick I will rest or read. I am a big fan of sitting in stillness.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I have a sensitive sense of smell, so thisconjures up seasons and memories over a lifetime of homes, but to choose one,since “home” here feels like the past, or the first, I’d say the crisp, but staleinside of an old hockey rink.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that bookscome from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music all the way. I am moved to tears on aregular basis by song. I also really love film moments where the music is just right,and feelings are captured and slowed down. I aim to reconstruct that in words. Mynovel was influenced by skateboarding and the use of public space as a contextfor adolescent development. Skateboarding is a hobby that is emulated infashion and art, but if you are a real skateboarder, you’re usually apatheticabout inspiring the trends, the true focus is on creative expression withoutboundaries. Grit and determination, play. I don’t think we play enough asadults.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’m a huge fan of Miriam Toews and Joshua Whitehead. The Kite Trick by Bill Gaston changed the limits of what Ithought was possible in a short story. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeousby Ocean Vuong, to me is the most eloquent production of a poem and I justbathe in those words when I lose track of where I am going.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

This question is so perplexing to me. I’vedone a lot in my lifetime. Take my son to Disney? Travel the World? What is onesupposed to say? In my truth, there is something deeper percolating: I want toenter a relationship with the vulnerable task of communicating my needs calmly.I want to be seen and heard in love. I don’t think I’ve done that.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

I have a full-time career as a ProbationOfficer on the side. It’s humbling and forces me to show up for people and bearwitness to their stories. I try to fudge the system how I can, I am not in itfor the law enforcement. I love connecting with people and being a part oftheir lives in a positive way.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

Strangely enough, writing has been theconstant. It’s as though if I am not writing I am not breathing. It’s the way Iprocess life. In my elementary school writing books, I was always asking theteachers for more library time and more art!

I played a lot of sports, played in band anddid drama, but when things fell to the wayside, writing was always there.

19 - What was the last great book you read?What was the last great film?

I can find greatness in nearly every book Ifinish. I recently adored Rouge by Mona Awad. As for film, I was very moved bythe remake of All Quiet on the Western Front. I am a sucker for dramas with anepic score.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Iam currently working on a collection of poems, and a second novel about aninfertile woman returning to her unincorporated hometown for the funeral of herchildhood best friend, a woman whose addiction resulted in the loss of herkids. One desperate to have a child, the other incapable of caring for them. Itis a walk down the memory lane of a secret-holding, shady and depressedcommunity.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

April 12, 2024

Jeremy Clarke, STONE HOURS

Angelus

An old wooden chair withthree legs | stands on the bypass

Holding a handful of rain| A monument of sky sits

On the water | A cloudcomes to the sky | stays for a time

Then | unthinking |strays |

In winter | snow’s

Slow surrender surpriseseverything |

FromBritish-born British-Canadian poet Jeremy Clarke comes STONE HOURS (TorontoON: Rufus Books, 2024), a “medieval Book of Hours reimagined in an urbanlandscape. Although devised in London, the poems, like the crosses in the city’skerbstones, stand for all that is urban.” I hadn’t heard previously of Clarke, sowas intrigued at someone seemingly out of nowhere with a 340 page volume. Accordingto online sources, he is the author of the chapbooks Incidents of Travel(2012) and Common Prayer (2012), and full-length collections Devon Hymns (2010) and Spatiamentum (2014), all published by Torontopublisher Rufus Books, as well as the privately printed illustrated booklet Cathedral(2017) and Bread of Broken Ground (2020), as well as Psalms in theVulgar Tongue (Turkey: Wounded Wolf Press, 2018). Also, according toWikipedia, Clarke was Poet in Residence at Eton College from 2010 to 2020. Whyhave I not previously heard of Jeremy Clarke? As part of his “Requiem,” heoffers:

The place where the windis always. Going

through a pile of bricksfor a single precious

stone. One red in all theold brown there

must be. Colour is whatthe light is simply

taking. The days streamand it would be

summer and everythingthriving in the arc

of its decline.Everything in its hunger

for undoing. How a wholeplace will separate

into parts to become aland of strangers.

It is being said. What iseach thing but moving

towards its owncounterweight of wild

in the adoration of thealways

emptying air. It is forthe wind

the rain will make abrown reveal its red.

Withopening poem “Angelus,” STONE HOURS (a lovely edition of 350 copies, with pressed goldfoil on the cover and flaps) works the format of the medieval Book of Hours acrossfifteen sections—“Last Dream Before Sleep,” “Tender for the Garden,” “Praise,” “Requiem,”“Night Office,” “Adam’s Lament,” “Bread of Broken Ground,” “Stonelight,” “CommonPrayer,” “Breath & Echo,” “The Desire Field,” “Psalms in the Vulgar Tongue,”“Music for Amen,” “Cathedral” and “Seven Words”—of sequential short orexpansively long poems composed as fragments, prayers, narrative stretches, momentsand meditations. The poems dig deep into such small, important moments, onesthat, at times, I wonder if there might ever be a way out. “And I am here,” hewrites, near the end of the third section/hour, “Praise,” “in a place beyonddesire or fear. / Lying watching the day / turning inside out, // pulling outthe night / until it has filled the room.”

Withopening poem “Angelus,” STONE HOURS (a lovely edition of 350 copies, with pressed goldfoil on the cover and flaps) works the format of the medieval Book of Hours acrossfifteen sections—“Last Dream Before Sleep,” “Tender for the Garden,” “Praise,” “Requiem,”“Night Office,” “Adam’s Lament,” “Bread of Broken Ground,” “Stonelight,” “CommonPrayer,” “Breath & Echo,” “The Desire Field,” “Psalms in the Vulgar Tongue,”“Music for Amen,” “Cathedral” and “Seven Words”—of sequential short orexpansively long poems composed as fragments, prayers, narrative stretches, momentsand meditations. The poems dig deep into such small, important moments, onesthat, at times, I wonder if there might ever be a way out. “And I am here,” hewrites, near the end of the third section/hour, “Praise,” “in a place beyonddesire or fear. / Lying watching the day / turning inside out, // pulling outthe night / until it has filled the room.” Poetshave long been engaged with compositions around time—I could mention recentexamples including Stefania Heim’s Hour Book (Ahsahta Press, 2019) [see my review of such here] or Brenda Coultas’ The Writing of an Hour (WesleyanUniversity Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]—but the “Book of Hours” isobviously a very specific kind of liturgical meditation, engaged morespecifically over the years by poets such as bpNichol, as part of his multiple-volumelong poem, The Maryrology, or Cole Swensen, who wrote around afifteenth-century book of hours, the Trés Riches Heures du Duc de Berry,through her Such Rich Hour (University of Iowa, 2001). For Clarke, thereisn’t the experimental push of language that some of those other examples mighthave employed, as he instead deliberately examines the structure of thosehours, those prayers and meditations, and moves across a narrative trajectory simultaneouslytimeless, ongoing and sequentially regulated. He takes a medieval form down toits roots, adding a fresh perspective across old knowledge, unfurling his lyricacross such ancient bones. As Robert Kroetsch offered via his stone hammer,when a rock becomes tool it becomes stone, and Jeremy Clarke provides. As in thepoem-section “A Mass,” as he writes:

Under weeds, tippedwaste. Old lumber, blown litter. What the light

is reaching withdiamonds. How a day is broken and distributed. Even

as an hour falls in avacant country bearing the responsibility of being

without utility. Still,each item intricate as a fingerprint in the desert

of everything taken by surprise.

April 11, 2024

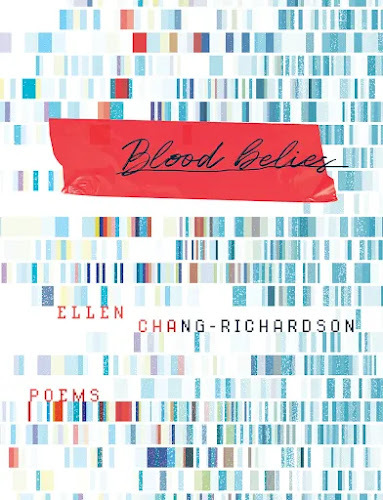

Ellen Chang-Richardson, Blood Belies

I can still hear the mosquitosin my deepest anxieties, hear

their high-pitched hum. Ican feel the oppressive heat. I can

smell it, thatcombination of human feces and fear pungent.

My small nose wrinkles.

I crawl into my fort-likecabinet, run my hands over solid

wood, feel the p u l s e of my father’s secrets in my

veins. enclosed. safe. claustrophobic. free. (“storm surge”)

Oh,I am absolutely delighting in the structures and shapes of Ottawa-based poet, editor and collaborator Ellen Chang-Richardson’s full-length poetry debut,

BloodBelies

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2024), published through PaulVermeersch’s Buckrider Books imprint. Even the back cover copy provides aliveliness, working to prepare any reader for the wealth of possibilities thatlay within: “In this arresting debut collection Ellen Chang-Richardson writesof race, of injury and of belonging in stunning poems that fade in and out ofthe page. History swirls through this collection like a summer storm, as theybring their father’s, and their own, stories to light, writing against thebackground of the institutional racism in Canada, the Chinese Exclusion Act,the head tax and more. From Taiwan in the early 1990s to Oakville in the late1990s, Toronto in the 2010s, Cambodia in the mid-1970s and Ottawa in the 2020s,Blood Belies takes the reader through time, asking them what it means tolook the way we do? To carry scars? To persevere? To hope?” There is such awonderful polyvocality to this collection, a layering of time and tales told, includingasides, overlapping and faded, fading text; a multiplicity within a singularframe, representing multiple ways, furrows and threads across this collection.The poems offer quick turns, clipped lyrics and inventive speech, writingheredity, silence and open space.

Oh,I am absolutely delighting in the structures and shapes of Ottawa-based poet, editor and collaborator Ellen Chang-Richardson’s full-length poetry debut,

BloodBelies

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 2024), published through PaulVermeersch’s Buckrider Books imprint. Even the back cover copy provides aliveliness, working to prepare any reader for the wealth of possibilities thatlay within: “In this arresting debut collection Ellen Chang-Richardson writesof race, of injury and of belonging in stunning poems that fade in and out ofthe page. History swirls through this collection like a summer storm, as theybring their father’s, and their own, stories to light, writing against thebackground of the institutional racism in Canada, the Chinese Exclusion Act,the head tax and more. From Taiwan in the early 1990s to Oakville in the late1990s, Toronto in the 2010s, Cambodia in the mid-1970s and Ottawa in the 2020s,Blood Belies takes the reader through time, asking them what it means tolook the way we do? To carry scars? To persevere? To hope?” There is such awonderful polyvocality to this collection, a layering of time and tales told, includingasides, overlapping and faded, fading text; a multiplicity within a singularframe, representing multiple ways, furrows and threads across this collection.The poems offer quick turns, clipped lyrics and inventive speech, writingheredity, silence and open space.Setthrough three sections, and a poem on either end of the collection to bookend,Chang-Richardson plays with space on the page through word placement, composed absence,swirls of text and image, erasure and hesitation, providing a forceful book-lengthprovocation of slowness, storytelling, pulse and punctuation. “My brother and Isometimes posit” they write, part-through the collection, “that maybe theynamed him Sing in the hopes he would go through life / embodying a song – //past present and future interactions make us question that line of thinking.” Chang-Richardsonwrites of race, of family, of identity; of anti-Asian racism, and a historythat provides an intimacy around such facts as Canada’s Royal Commission onChinese and Japanese Immigration in 1902, and The Chinese Immigration Act of1923, which prevented Chinese immigration into Canada until the Act wasrepealed in 1947. Chang-Richardson offers a delicate and powerful lyric of suchstrict, incredible precision, speaking only a single word or phrase or absence,where others might have offered pages. Through memory, archive, gymnasticlanguage, erasure and an expansive, inventive sequence of forms, Chang-Richardsonoffers insight into and through family history, trauma, possibility and story,one that honours both past and the present, constructed as a larger portrait offamily, history and self, but as much a loving and attentive outline of theauthor’s father. “I lost my wanderlust in tandem / to losing you --,” Chang-Richardson writes, near the openingof the collection, “ – but we no longer speak / of such things.”

April 10, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jesse Keith Butler

Jesse Keith Butler

is an Ottawa-based poet who recently won third place in the Kierkegaard Poetry Competition. You can find his poems in a variety of journals, including Arc, Blue Unicorn, THINK, flo. and The Orchards Poetry Journal. His first book,

The Living Law

(Darkly Bright Press, 2024) is available wherever books are sold.

Jesse Keith Butler

is an Ottawa-based poet who recently won third place in the Kierkegaard Poetry Competition. You can find his poems in a variety of journals, including Arc, Blue Unicorn, THINK, flo. and The Orchards Poetry Journal. His first book,

The Living Law

(Darkly Bright Press, 2024) is available wherever books are sold.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book of poetry, The Living Law, was published on March 1, 2024. It's probably too early to say how it has changed my life. This book is a compilation of selected poems written over the last twenty years, so it is much more a continuity of my writing rather than a break from an earlier phase. It feels like the fulfillment of all my writing to date.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

While I've dabbled a bit in fiction and published non-fiction (academic articles) poetry has always been my preferred medium. I remember as a very young child aspiring to be Dr. Seuss. Something about the musical and rhythmic use of language, the intense compression of meaning, has always appealed to me at a deep level. It still feels to me like the most natural way to use language.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm a very slow writer. Sometimes a first draft comes quickly, though more often it'll start as a seed--just a phrase or even a rhythm--rattling around my head for weeks. Once I have a draft I tend to revise it many times. I'll often have multiple times when I think a poem is complete, and even submit it for publication, but then later rethink it and revise it again. A number of the poems in the book are revisions of a poem previously published in a journal.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

This book is definitely more of a compilation, although there are themes running through the book that give it a sense of unity. Now that I have published my first book, I find that I'm more likely to think about how new poems might fit into an imagined future collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy connecting with people about poetry, but not being the centre of attention. I'm an introvert and I stutter, so poetry readings are a bit of a stretch for me. But I value them as a way to share my poetry with people who might not otherwise pick up the book.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I prefer a poem to emerge from either a striking image or a memorable phrase. It can engage with theoretical concerns as it develops, but I feel like poems are richer if they don't start with a specific thesis.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I'm not sure I can speak for writers in general, but I see the role of the poet as reminding people to slow down in a frantic age. Most people don't listen, but I think there's value in presenting an alternative way of engaging deeply with language and reality.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It's both. There's a difficult balance as a poet in getting outside your own head to speak engagingly with your audience while also staying true to the original gut instinct that is the source of the poem. A thoughtful dialogue with an external editor can help you work through this, but it can also be frustrating and water down the work.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

At one point in developing my book I had the impulse to cut a bunch of the older poems and replace them with brand new ones I was then writing. My friend and fellow poet Joshua Alan Sturgill told me I should keep the focus on poems that I've been satisfied with in a stable way for a long time, rather than what's exciting me at the moment. It was good advice -- many of the poems I was then thinking of including were too fresh and have continued to evolve over time. They still need time to stabilize.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a writing routine. I have a full-time job and kids, and I write in little bits where I can.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I try not to get stressed about it. I try to just focus on living well, having good relationships, and reading good books. Those things are the source of good poetry, when it comes.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I grew up in the Yukon, so my first thought here is pine trees.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yeah, a lot of my inspiration is literary. But I also have many poems inspired by nature, memories, experiences, or relationships.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Some of my favourite poets are Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. H. Auden, Emily Dickinson, Dylan Thomas, William Blake, Alice Oswald. I also read the Bible a lot, and other ancient literature. I also have a soft spot for science fiction. I'm a pretty eclectic reader, and it all shapes my poetry.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I've been really interested in the recent trend of verse novels. I think I'd like to give that a try eventually.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Writing really isn't my occupation, it's a hobby I do where I can on the side. I'd love to be a full-time writer, but that's not really an option right now.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I'm not sure I have an answer to that. I've always been drawn to poetry, as far back as I can remember.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I'm currently reading Stanislaw Lem's Solaris. I'm a big fan of the Tarkovsky movie, and finally am getting to the novel. I love science fiction that explores an encounter with a genuinely alien form of life. Speaking of which, the last great film was probably Annihilation , which I'd also group in that genre.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Since finishing The Living Law I've been writing a series of poems roughly themed around flood mythologies, geological history, and climate anxiety. This may be the beginning of my second book, but time will tell.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;