Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 68

December 20, 2023

Beir Bua Press: Lydia Unsworth, Vik Shirley, Tom Jenks + Anthony Etherin,

WhenTipperary, Ireland publisher Beir Bua Press (2020-2023) announced, seeminglywithout prior warning, whether to the public or to their authors, that theywere suspending publication and pulling books from availability back in June, Iknew I had to get my hands on a few more titles before they disappearedcompletely. Thanks to individual authors, I’d managed to see two titles priorto this two-week warning: Texas-based Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly’s pandemic-era BOULEVARD (2021) [see my review of such here]and Hamilton writer Gary Barwin and St. Catharine’s, Ontario writer Gregory Betts’ collaborative The Fabulous Op (2022) [see my review of such here]. Given how quickly the press vanished, it did cause a certain amount ofchaos, especially from authors of relatively-recent titles, but more than a fewhave since been picked up for reissue by other presses: the Barwin/Bettscollaboration and both Beir Bua O’Reilly titles were picked up by Australia’s Downingfield Press, for example, with other Beir Bua titles picked up by Salmon Poetry, kith books, Sunday Mornings at the River and IceFloe Press. The loss of the press isfrustrating, but they accomplished an enormous amount across a relatively shortperiod of time.

Runby Irish poet and editor Michelle Moloney King, Beir Bua Press seemingly appearedout of nowhere, quickly establishing itself as a press willing to take risks onexperimental work across a wide spectrum of style and geography. King clearly hasa fine editorial eye, and the print-on-demand Beir Bua poetry titles were well-designed,looked sharp and included some fantastic writing. To be clear: by shuttering the press so abruptly and allowing her authors no recourse (or prior warning), she did her authors an enormous disservice, and they deserved far better. Either way, given the press disappeared so suddenly,I wanted to at least acknowledge a couple of these titles I ordered back inJune, prompted by that infamous “last call for orders.”

Lydia Unsworth, Some Murmur (2021): I’ve been an admirer of Unsworth’s work for a while (a third above/ground press chapbook is forthcomingnext month, I’ll have you know), and this is a collection framed as onereacting to a sequence of changes in quick succession: moving to Amsterdam fromEngland ten days before the Brexit referendum, and discovering that she waspregnant. As she writes in her prologue: “When I found out I was pregnant, notlong after the Brexit referendum, it felt like a part of me had died and like asecond part of me was steadily dying. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, becausea lot of people feel a lot of things about procreation—about wanting babies,not wanting babies, really wanting babies, having babies, not having babies,really not having babies, how you should have babies, how you should not havebabies—but the way I saw it, from that side of the expansion, was that someunknown and unknowable event was lurching towards me, and its manifestationswere showing up all over my body; rising out, bearing down.” Unsworth appearsto be a poet that engages with projects, whether book-length orchapbook-length, and this collection works to engage with this sequence of new,foreign spaces, reacting to the notion of permanence, and fluidity across whathad previously been fixed. Have you read her take on the prose poem, over at periodicities?She writes of escape, changing forms and sustainability, offering a prose lyricthat manages to articulate these shifting sands even as they move. “Thought itwas wise to stand before the mirror crack,” she writes, as part of the poem “Attemptsto Recover My Previous Form,” “wide like bags of old receipts in supermarketbins. I didn’t compare myself to anyone but how can you not look at all thoseupended trunks trying to hold their bad weather in?”

Lydia Unsworth, Some Murmur (2021): I’ve been an admirer of Unsworth’s work for a while (a third above/ground press chapbook is forthcomingnext month, I’ll have you know), and this is a collection framed as onereacting to a sequence of changes in quick succession: moving to Amsterdam fromEngland ten days before the Brexit referendum, and discovering that she waspregnant. As she writes in her prologue: “When I found out I was pregnant, notlong after the Brexit referendum, it felt like a part of me had died and like asecond part of me was steadily dying. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, becausea lot of people feel a lot of things about procreation—about wanting babies,not wanting babies, really wanting babies, having babies, not having babies,really not having babies, how you should have babies, how you should not havebabies—but the way I saw it, from that side of the expansion, was that someunknown and unknowable event was lurching towards me, and its manifestationswere showing up all over my body; rising out, bearing down.” Unsworth appearsto be a poet that engages with projects, whether book-length orchapbook-length, and this collection works to engage with this sequence of new,foreign spaces, reacting to the notion of permanence, and fluidity across whathad previously been fixed. Have you read her take on the prose poem, over at periodicities?She writes of escape, changing forms and sustainability, offering a prose lyricthat manages to articulate these shifting sands even as they move. “Thought itwas wise to stand before the mirror crack,” she writes, as part of the poem “Attemptsto Recover My Previous Form,” “wide like bags of old receipts in supermarketbins. I didn’t compare myself to anyone but how can you not look at all thoseupended trunks trying to hold their bad weather in?”Stoop

The body bends towardsyou like a plant. You are

my sunshine, my ray of sunshine.What do you call

a plant warped by circumstance?I hold you up to the

light. Ten lifts then tento the side. Environmental

stress weakens the plant.You are heavy fruit. My

stem turns to you, hulkingsunflower head bows

down, seeds fall from myeyes. Wind-blown tree –

frozen in flight. Umbrellainside-out, novelty tie

coat-hangered into aU-turn, leg kicked out high.

Flamboyant ice. Waitingfor a coin in a hat to say

it’s time.

Vik Shirley, Grotesquerie for the Apocalypse (2021): As Shirleywrites in her introduction, the origins of this short collection emerged “outof an intensely creative period in the first year of my PhD, which exploresDark Humour and the Surreal in Poetry. Focussing on the grotesque, I wasimmersed in, and obsessed with, the work of the Russian-Absurdist, Daniil Kharms, and the strange and surreal fable-like poems of Russell Edson.” This isa relatively short collection (why are these books unpaginated?) very muchshaped through the prose poem and prose sentence, and one can see echoes of Edson’swork throughout, with similar echoes that emerge through Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany. As the poem “Husband Ghost” opens: “A hospital rang to tell awoman that her husband was dead. // Not only was he dead, but his body haddecomposed already and he / had progressed straight through to the ‘ghostphase,’ they said. // They told her she should come and collect him.” There aresome interesting echoes, as well, that connect certain of these poems, whetherthe cluster of “Hello Kitty” poems, or poems that open with a similar descriptivestructure. I would very much like to see further pieces by Vik Shirley, and herstatement on the prose poem over at periodicities is worth reading, incase you haven’t already seen (and she does mention that this collection will appear as part of a larger work to appear in 2025, which has yet to announce). In a certain way, Shirley appears to approachher lyric from the foundation of the sentence, opening the collection with poemsthat lean further into line breaks, but soon moving into poems built out of prosepoem blocks, each of which offer short, sketched scenes that twist and turn andfurther twist. The poem “Devil Baby” is a striking example of such, and reads,in full:

A baby started speaking intongues.

“We don’t want a devil baby,”its parents said.

So they put it in adinghy, covered it with foil and set it sail down the Nile.

They were on holiday inEgypt, you see.

It was the worst holidaythey’d ever had.

Tom Jenks, rhubarb (2021): Providing echoes of thework of Vik Shirley, Tom Jenks’ rhubarb also seems a collection of poemsthat focus on the sentence, some of which offer line breaks, with others set ina more prose poem structure. One might say that his poems offer first person narrativesthat seek out their structures. “The horse was revealed to be entirelytwo-dimensional.” the two-sentence poem “opportunities” begins. “This presentedchallenges, but also opportunities.” The prose sentences ofTom Jenks offer first person nararatives, movingback and forth from short, sketched bursts, expansive open form poems toclustered prose blocks. There’s such a wry delight in sound and syntax across these poems that are intriguing, and the collection exists as a kind of collage on form, moving from the expansive open lyric to densely-packed short burst. I’d only seen Jenks’ visual works prior to this, so amnow quite fascinated by what he is exploring through his sentences: a kind ofsurreal swirling of narrative twists and turns, one that is open to the experiment-as-it-occurs. I am very interested in seeing where else his poems might find themselves.

scissors

Syrop on soya, the squareholes in waffles,

cheesy dumplings, ancientgrain rolls,

I don’t know what to makeof any of it.

All the elements for agood life are in place,

yet a good life is notbeing lived.

We should rethink the solarsystem

or buy each othershoulder bags.

I saw a dog that was entirelysee through.

I’ve got a ride on mower

but I still use scissors.

Anthony Etherin, Fabric (2022): Another author published previously through above/ground press, “experimental formalistpoet” Anthony Etherin, a poet, editor and publisher who lives “on the border ofEngland and Wales,” offers a cluster of poems in Fabric that continuehis strict adherence to formal poetic structure, engaging with such as theacrostic, anagram, lipogram, palindrome, villanelle, sonnet and ambigrams, evento the point of brevity, as some were composed with the Twitter/X limit of 280characters/140 characters in mind. “Fit one sent rule:,” the final couplet of “SonnetFuel” reads, “Tier sonnet fuel.” Part of what is always interesting in Etherin’songoing work is in seeing just how far it is possible for him to continueacross such highly-specific formal paths, and the wonderful variations thatemerge through his collections. The overt brevity is interesting as well,offering new layers to his ongoing structures. In his introduction, he offersthat “The poems of Fabric [a book he posted online as a free pdf, by the way] are at ease with their poemhood. Some discusspoetry itself, while others are more introspective, eager to evaluate theprinciples and rules by which they were constructed.” They are at ease withtheir poemhood, highly aware of their structures, as the collision of sound andmeaning provide the delight of what formal possibilities might bring.

Anthony Etherin, Fabric (2022): Another author published previously through above/ground press, “experimental formalistpoet” Anthony Etherin, a poet, editor and publisher who lives “on the border ofEngland and Wales,” offers a cluster of poems in Fabric that continuehis strict adherence to formal poetic structure, engaging with such as theacrostic, anagram, lipogram, palindrome, villanelle, sonnet and ambigrams, evento the point of brevity, as some were composed with the Twitter/X limit of 280characters/140 characters in mind. “Fit one sent rule:,” the final couplet of “SonnetFuel” reads, “Tier sonnet fuel.” Part of what is always interesting in Etherin’songoing work is in seeing just how far it is possible for him to continueacross such highly-specific formal paths, and the wonderful variations thatemerge through his collections. The overt brevity is interesting as well,offering new layers to his ongoing structures. In his introduction, he offersthat “The poems of Fabric [a book he posted online as a free pdf, by the way] are at ease with their poemhood. Some discusspoetry itself, while others are more introspective, eager to evaluate theprinciples and rules by which they were constructed.” They are at ease withtheir poemhood, highly aware of their structures, as the collision of sound andmeaning provide the delight of what formal possibilities might bring.

Tautograms

The tautogram ties

terms to their typography–

tightening this text.

December 19, 2023

Kim Rosenfield, Phantom Captain

Americans are terriblereaders of anything as old and complex as a 1757 work on how sublime andbeautiful changes upset our lives and become traumatic ideologies gettingcrowded out by a future like Manners Maketh the Man. We didn’t fall forWorld War wit. Humor of the forbidden went on and on and we had to functionwith creative tensions that produced emotional intensity

My attitude should becomemore like my way of describing great observations. I need to know, from all thewhatnot that gets in my way of thinking, about what is going on. That’s when I’llfinally have insight into what is bothering my characters

World War wit is based onforbidden reciprocity that stands above political thinking’s shoulder. “Peacewithout Victory” is lacking in triumphalism. Here I am thinking of war as aproblem to be solved by not joining either side (“Former Present Times”)

Thelatest by Brooklyn poet Kim Rosenfield [see her recent ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], and the first of hers I’ve seen, winner of the Ottoline prize, is

PhantomCaptain

(Astoria NY: Fence Books, 2023). Set in six numbered, extendedsections—“Longing Crosses the Sea,” “Former Present Times,” “Aesthetics of theInvisible Realm,” “Natures Afterward Hours,” “It’s Been an Almost HystericalTest of My Mettle” and “The Great Empty Goodnight”—her lyric sextet engages inan unfurling, extending page across page of examination and poem-as-elegy,offering a book of presence and self-examination. “I am as American assuffering.” she writes, as part of the second section. “Born from an epidemicof people who like to eat sugar for a high and make ineptitude fun, who are notyet social enough to understand pathological hatred is making history the wrongapproach [.]” The lyric sweeps of Phantom Captain work to articulate whatrefuses the fixed point, offering a sweep across a body, and a thinking, verymuch in motion. “My changes are rapid enough to defy recognition.” she writes, aspart of the opening section. Slightly earlier, offering: “In this very identity/ Sits a pleasurable condition / Void of wishes [.]” This is a collection that beginsat the self and ripples outward, slowly, one ring, one sentence, one fragment-accumulationat a time, from cultural capital to disinformation, political action and communalresponsibility, and how the ego responds and reacts, allowing the language ofher lyrics to fold in on themselves. “We tear at our wounds on Vita Instagram,”she writes, as part of the fifth section, “When I slide / It is a deep dark /Hallucinogenic hole / A gourmet donut / Round how I’ve failed / At life atbirth / At wisdom at hedging [.]” Or, as the final fragment of the collectionoffers:

Thelatest by Brooklyn poet Kim Rosenfield [see her recent ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here], and the first of hers I’ve seen, winner of the Ottoline prize, is

PhantomCaptain

(Astoria NY: Fence Books, 2023). Set in six numbered, extendedsections—“Longing Crosses the Sea,” “Former Present Times,” “Aesthetics of theInvisible Realm,” “Natures Afterward Hours,” “It’s Been an Almost HystericalTest of My Mettle” and “The Great Empty Goodnight”—her lyric sextet engages inan unfurling, extending page across page of examination and poem-as-elegy,offering a book of presence and self-examination. “I am as American assuffering.” she writes, as part of the second section. “Born from an epidemicof people who like to eat sugar for a high and make ineptitude fun, who are notyet social enough to understand pathological hatred is making history the wrongapproach [.]” The lyric sweeps of Phantom Captain work to articulate whatrefuses the fixed point, offering a sweep across a body, and a thinking, verymuch in motion. “My changes are rapid enough to defy recognition.” she writes, aspart of the opening section. Slightly earlier, offering: “In this very identity/ Sits a pleasurable condition / Void of wishes [.]” This is a collection that beginsat the self and ripples outward, slowly, one ring, one sentence, one fragment-accumulationat a time, from cultural capital to disinformation, political action and communalresponsibility, and how the ego responds and reacts, allowing the language ofher lyrics to fold in on themselves. “We tear at our wounds on Vita Instagram,”she writes, as part of the fifth section, “When I slide / It is a deep dark /Hallucinogenic hole / A gourmet donut / Round how I’ve failed / At life atbirth / At wisdom at hedging [.]” Or, as the final fragment of the collectionoffers:What is required to cometo life?

is from the performance?

is contact at odds withdelivering

these opposites

which are so much everywhere

my personality statues

my barbaric natural body’sway to consolidate

a careful commodity thatis not containing anything

that is not a vessel foranything

but a sensory smatter ofself-hood some people never get together

as in what does it meanthat I can’t take a lifetime

in this aggravatingacceleration

to say

what I

must

December 18, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jane Huffman

JaneHuffman’sdebut collection, Public Abstract, won the 2023 APR/Honickman First BookPrize, selected by Dana Levin. Jane is a doctoral student in poetry at theUniversity of Denver and is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. She iseditor-in-chief of Guesthouse, an online literary journal. Her work hasappeared in the New Yorker, Poetry, The Nation, andelsewhere. She was a 2019 recipient of the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy SargentRosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. Online at www.janehuffman.com

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thefirst book didn’t change my life, but I’m happy for the new opportunities andconnections it has brought me. I’m working on something very different now.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Istudied it seriously for the first time as an undergraduate, taking classes atKalamazoo College with Diane Seuss. Before that, via e.e. cummings: Complete Poems, edited by George J. Firmage, which my dad bought me when I was a kid.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Itend to work on a draft to completion in one or two sittings. I revise as Iwrite. I tend to decide quickly and intuitively whether a poem is going toamount to something.

4- Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Poemsusually begin with language rather than ideas. I never thought of the poems in Public Abstract as a book until it suddenly was one, and then it took on various manifestations, forms, shapes, titles, before it was ready to be published. The project I’m working on now feels more like a project, more congealed.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ienjoy reading a lot, but since COVID-19, I have become extremely wary of largegroups. I love Zoom readings and would like to do more of them.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Lately,the idea of “firstness,” “secondness,” and “thirdness” from Charles Sanders Peirce, which proposes how an “idea” emerges. I am also interested in theories of illness and recently began writing about the “cough” as a semiotic unit, a driver of repetition.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Tokeep record. To add to the human archive. To be humane. And if they teach, toteach energetically and ethically.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Iwelcome editorial feedback whenever it is available. I have a few trustedfriends who read new work and can tell me if something is getting warmer orcolder.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Fromthe al-anon community: Easy does it.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to criticalprose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ifind it extremely difficult, and so by necessity, one register bleeds into theother. I think that is also the appeal.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Idon’t have a writing routine. I write when I can, as much as I can. A typicalday begins stallingly, mid-morning, with coffee and a dog walk.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Ireturn to reading. Or listen to talk radio. In each, I’m trying to pick up on amode or register in an outside voice.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

CanI say a sound instead? Snow-blowers blowing before sunrise.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Ihave been learning ceramics, and I love how, unlike a poem, you work from thebottom to the top. This concept has informed my current writing project.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Somany. I’ll narrow to a few who sat with me as I wrote Public Abstract: Emily Dickinson, Kay Ryan, Kimiko Hahn, Jean Valentine, John Keats, Dionne Brand, Rosmarie Waldrop.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Answerthe unanswered emails.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Iwould be training horses in rural Michigan.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Idon’t know. Despite many tortured efforts, I was a terrible singer, dancer, andmusician.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Currentlyreading The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing. Recently loved Brian Teare’s Poem Bitten by a Man. The film that comes to mind is Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow (2019).

20- What are you currently working on?

Asecond manuscript of poems that incorporate parentheses. Also a PhD in Englishand literary arts.

December 17, 2023

Matthew Gwathmey, Tumbling for Amateurs

A DIVE

Look to Sparta

or Athens

or Rome

for examples

of how to

reduce risk.

Jump for height

and distance,

alighting on praxis.

Bend arms,

duck head,

and forward

body over.

Never strike

the middle

of your back first.

Gradually

increase the height

and distance

until you can

dive across

the whole court

without jolting

or bumping

yourself in the least.

Thesecond full-length collection by Fredericton, New Brunswick poet Matthew Gwathmey, following the full-length debut, Our Latest in Folktales (LondonON: Brick Books, 2019) [see my review of such here] and the chapbook looping climate (above/ground press, 2022), is Tumbling for Amateurs(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023). “We have no other way to touch eachother.” he writes, to open the poem “NO OTHER WAY.” “Really no other way totouch each other. / We seek this particular exercise because / we have no otherway to touch each other.” Compiled as a collection of collaged and reassembledtext and image, Tumbling for Amateurs is a book of lyric translation,response, poetic structure, play and verve, riffing off an athletic manual ofthe same name, described on this collection’s back cover as “a 1910 manual from the Spalding Athletic Company.” As Gwathmey writes as part of his “NOTES ANDACKNOWLEDGEMENTS” at the end of the collection:

Tumbling for Amateurs is a modernreimagining of an old sporting manual written by a distant relative. The originaltext literally fell into my lap, and I was immediately taken by the descriptionsof various feats of tumbling as well as accompanying illustrations and associatedmetaphors. I tried to peel back these layers to find the possibility of ahidden subculture of desire, both homosocial and homoerotic. This collectionaims to give voice to a suppressed existence of the early twentieth century. JamesTayloe Gwathmey’s original text of the same name was published in 1910 as partof Spalding’s Athletic Library and was gifted to me by someone who recognizedthe last name and thought that it must be poetry. JTG really is my distantrelative: my second cousin, four times removed. I wanted to write the book thatmy friend thought Tumbling for Amateurs was.

There’sa twirling and tumbling to his lines, many of which might need to be heard orspoken to be properly appreciated. “All in a queue & start & start& we start & we / start & we crotch front & we straddle over& / we crotch back & we straddle under & we / crotch front,” thepoem “CROTCH & STRADDLE” begins. Sharp and studied, the poems thataccumulate, and even collage, into this book-length collection display a myriadof forms, offering overt play and visual displays of language, sound and, dare Isay it, gymnastic fervor. “Reclining at meat,” the poem “THE JOUSTINGTOURNAMENT” begins, “three guys clench each other’s hopes / and roll intochivalrous accolades. / To aid and succour at the sound of a bugle or herald’scry – / Arthur squats, / Bennie planting charity / on Arthur’s strength.” Theimages included by Gwathmey, acrobatically collaged from the source volume, illustratethe poems, but just as much interact, and even counterpoint, allowing a visualthread that intermingles with the poems in its own simultaneous directionthrough the collection. Leaning into male movement, attention and desire, the poemsopen from the perspective of a subject matter that, at least from the sourcematerial, both suggests and deflects, all of which is on full display in MatthewGwathmey’s playful blend of translation and reimagining.

There’sa twirling and tumbling to his lines, many of which might need to be heard orspoken to be properly appreciated. “All in a queue & start & start& we start & we / start & we crotch front & we straddle over& / we crotch back & we straddle under & we / crotch front,” thepoem “CROTCH & STRADDLE” begins. Sharp and studied, the poems thataccumulate, and even collage, into this book-length collection display a myriadof forms, offering overt play and visual displays of language, sound and, dare Isay it, gymnastic fervor. “Reclining at meat,” the poem “THE JOUSTINGTOURNAMENT” begins, “three guys clench each other’s hopes / and roll intochivalrous accolades. / To aid and succour at the sound of a bugle or herald’scry – / Arthur squats, / Bennie planting charity / on Arthur’s strength.” Theimages included by Gwathmey, acrobatically collaged from the source volume, illustratethe poems, but just as much interact, and even counterpoint, allowing a visualthread that intermingles with the poems in its own simultaneous directionthrough the collection. Leaning into male movement, attention and desire, the poemsopen from the perspective of a subject matter that, at least from the sourcematerial, both suggests and deflects, all of which is on full display in MatthewGwathmey’s playful blend of translation and reimagining.

December 16, 2023

Katy Lederer, The Engineers: Poems

MUTATIONS I

We had been organismsmostly, as we slung our legs across the plain.

Observed, we wereobservable. Before we saw, we closed our eyes.

Before we could becomeourselves, we had to name the animals;

successive in ourshortening, unable to extend our lives.

Observed we wereobservable. Before we knocked, we closed our eyes.

Late-acting, deleterious,we saw by death we would be had.

Successful in ourshortening, unable to extend our lives.

Contemplative without ourtails, we knew we’d say what could be said.

Lactating, deleterious,we saw by death we would be had.

What seekingunobtainable, pursuing prey, we closed right in.

Contemplative without ourtales, we knew we’d say what could be said.

What knowing wasunknowable, without our eyes we might have seen.

What seekinginexplicable, pursuing prey, we closed right in.

Before we could controlourselves, we had to name the animals.

What showing wasun-showable, without our eyes we might have seen.

As organisms mostly, we wouldsling our lives across the pain.

Fora while now I’ve been anticipating New York poet Katy Lederer’s latestcollection,

The Engineers: Poems

(Ardmore PA: Saturnalia Books, 2023), acollection that incorporates several poems from her chapbook

The Children

(above/ground press, 2017). “Sometimes, in the middle / of the night,” opensthe first poem in the collection, “FETUS PAPYRACEUS,” “our children will /insist that we tell them a story. / In the story, after heavy / rhyme andinsistent inculcation / of our customary ways, / our children will look down /at our apparent missing limbs, / which remind them / that they should nottouch, / and, if they do decide to touch, / that absence will feel presence.” Theauthor of a memoir,

Poker Face: A Girlhood Among Gamblers

(Crown, 2003),as well as three prior full-length poetry collections—

Winter Sex

(Verse/Wave Books, 2004),

The Heaven-Sent Leaf

(BOA Editions, 2008) [see my review of such here] and

The bright red horse—and the blue—

(Atelos,2017) [see my review of such here]—the poems of The Engineers: Poemsoffer lyric narratives that wrap and coil around and through rhythm and repetition,offering an examination of the history of the human body, running the gamutfrom the abstract to the deeply and immediately intimate. “We can look into thetissue,” she writes, as part of the poem “INFLAMMATION,” “can examine the finegradient. // We can speak in foreign languages, the language of the internet, /or maybe in the language of cell death. // Have we reached the site of injury?/ We have been injurious. // Have we served well on our jury? / We have juried.We have jured and jured. // We are sad. / Sad as a parent.” Onemight suggest this a book entirely set through and around the body, abook-length suite of poems offering insight and commentary into physicallimitations and requirements. I’m intrigued at how her poems echo, even loopback into each other, playing with repetition and shadow, curling back across acollection of poems interconnected at a rather deep and subtle level. Is therea better word to describe any part of this collection, whether in part orwhole, as sublime?

Fora while now I’ve been anticipating New York poet Katy Lederer’s latestcollection,

The Engineers: Poems

(Ardmore PA: Saturnalia Books, 2023), acollection that incorporates several poems from her chapbook

The Children

(above/ground press, 2017). “Sometimes, in the middle / of the night,” opensthe first poem in the collection, “FETUS PAPYRACEUS,” “our children will /insist that we tell them a story. / In the story, after heavy / rhyme andinsistent inculcation / of our customary ways, / our children will look down /at our apparent missing limbs, / which remind them / that they should nottouch, / and, if they do decide to touch, / that absence will feel presence.” Theauthor of a memoir,

Poker Face: A Girlhood Among Gamblers

(Crown, 2003),as well as three prior full-length poetry collections—

Winter Sex

(Verse/Wave Books, 2004),

The Heaven-Sent Leaf

(BOA Editions, 2008) [see my review of such here] and

The bright red horse—and the blue—

(Atelos,2017) [see my review of such here]—the poems of The Engineers: Poemsoffer lyric narratives that wrap and coil around and through rhythm and repetition,offering an examination of the history of the human body, running the gamutfrom the abstract to the deeply and immediately intimate. “We can look into thetissue,” she writes, as part of the poem “INFLAMMATION,” “can examine the finegradient. // We can speak in foreign languages, the language of the internet, /or maybe in the language of cell death. // Have we reached the site of injury?/ We have been injurious. // Have we served well on our jury? / We have juried.We have jured and jured. // We are sad. / Sad as a parent.” Onemight suggest this a book entirely set through and around the body, abook-length suite of poems offering insight and commentary into physicallimitations and requirements. I’m intrigued at how her poems echo, even loopback into each other, playing with repetition and shadow, curling back across acollection of poems interconnected at a rather deep and subtle level. Is therea better word to describe any part of this collection, whether in part orwhole, as sublime?

December 15, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brandi Bird

Brandi Bird [photo credit: Heather Saluti] is anIndigiqueer Saulteaux, Cree, and Métis writer and editor from Treaty 1territory. They currently live and learn on the land of the Squamish,Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam peoples. Bird’s poems have been published in Catapult,The Puritan, Room Magazine, and others. They are a fourth yearBFA student at the University of British Columbia, but their heart is alwaysyearning for the prairies.

1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst chapbook, I Am Still Too Much, published with Rahila’s Ghost Pressin 2019, changed my life in so many beautiful ways. When I first signed thecontract for my chapbook, I only had about five pages of usable work. I had tobuild the chapbook from the ground up and I learned so much about myself and myprocess. I also met some of my best friends through the editing processincluding my poet twin, Selina Boan (who edited the chapbook). We still editeach other’s work with a kindness and an honesty that I value with my wholeheart. She wasn’t afraid to push me and still isn’t. My writing and editingprocess for my first full-length book, The All + Flesh, was differentfrom my chapbook because I feel like my voice is more fully honed and isn’tconcerned with what’s expected of me. I wrote what I wanted and for who Iwanted.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Istarted writing poetry in 2016 after a very long break from it. I wrote as achild and adolescent and suddenly stopped at fifteen because I was moreconcerned with survival than creation. I picked poetry up again as an adultafter getting my mind blown by reading Liz Howard’s The Infinite Citizen ofThe Shaking Tent. I decided to go back to school and took poetry classes atDouglas College where my instructor Liz Bachinsky told me I was a poet. One ofthe first poems I wrote is actually in The All + Flesh (2023). I thinkpoetry makes sense to me because it is something that takes me places I can’tgo with fiction or non-fiction (at least right now). It feels small and thenexplodes. It changes me.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Myfirst book of poems is full of the work I’ve done over 3 years. I wrote amanuscript I shelved before The All + Flesh and I doubt it’ll see thelight of day. My writing comes quickly when I’m in a routine and I don’t waitfor inspiration to strike. I do take breaks from writing though because I findI get my best work done when I’m living too. I find restorative time to gathermy thoughts essential but I have to remember that I have a return to routine totoo. It’s a constant cycle of trying to measure my capacity especially sincewriting makes me feel alive when I can get it done.

4- Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

TheAll + Fleshis a cumulative work. My next book is a “book” with a theme I’m very cognizantof. Even within a theme, a poem usually begins with an idea/prompt or maybeeven just a word. I will often recycle metaphors and images in multiple placesjust to figure out where they best fit and then figure out how to untangle themess I’ve made in the revision process. I have a lot of fun with first draftsand I’m not afraid to share first drafts with people because I truly believe theyare something to be celebrated.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ishake when I do readings. But I find them fun too. Like a horror movie.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I’mvery concerned with health and “wellness” cultures right now. We use health andwellness as punishing forces in society and they get tangled in the largersystems at play. They seem like structures we have to scale and I’m so tired ofit. I touched on this theme a little in The All + Flesh but that bookwas more focused on physical pain as I wrote it when I was suffering fromextreme nausea almost every day. My next project is a book concerned with thegrief that comes with sickness/illness.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ithink being a writer is being a storyteller. Having a storyteller around isgreat fun but I don’t think a storyteller is as useful as say a plumber or amidwife or a dishwasher. Stories teach us a great many things and maybe theyteach us to be better people but I’m struggling with language and it’slimitations in the midst of the terrible grief I have felt recently.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Havingan editor is essential for me. My editors made my book better than I evercould’ve imagined. Working on my own turns everything I have written into salt.I stare at it too long and I lose it.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Writewhat’s true, not what’s beautiful.

10- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Iam a morning writer. Not every day of course but I try to write at least twodays a week. I revise more often than I write. Revision is great fun!

11- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Igo to my therapist because I’m usually afraid of something in my writing or inmy life that is making it hard to write. I will also just let myself take abreak sometimes and just live without the expectation of writing. That usuallyshakes it out of me.

12- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilacs.My grandma and grandpa had lilacs on their property in East Selkirk, Manitobaand it’s my favourite smell in the world.

13- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

I’minspired by the land of course, especially the land I grew up on in Manitoba.But music is another big inspiration for me. I write exclusively to music withlyrics, usually the same song on repeat, until I tune it out and vibrate out ofmy body. I’m writing this interview to a song right now (MGMT’s “One Thing Left To Try”).

14- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

OtherIndigenous writers’ work is so important to me. Liz Howard and Jordan Abel arewhy I write today. I can’t express how much their books changed my life.

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Iwant to write a novel!

16- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Onceupon a time, I wanted to go to medical school and was pursuing a sciencedegree. I wasn’t any good at it. I’m getting a Master of Fine Arts degree a.k.adelaying adulthood so I’ll let you know what I actually get up to when I finish!

17- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Anger.

18- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

SwanFeast byNatalie Eilbert. It’s research for my next book. And I saw Hot Rodrecently and it’s possibly the best comedy I’ve ever seen.

19- What are you currently working on?

Ihave sixty pages of a new manuscript about eating disorders. They’re roughpages but I’m happy to have written them. I wrote them during a literalmanic episode when I was sleeping between two and four hours a night andwriting the rest of the time. I wouldn’t recommend this process but the wordspoured out of me. If I could’ve chosen between not having the pages and beingwell, I would’ve chosen that though!

December 14, 2023

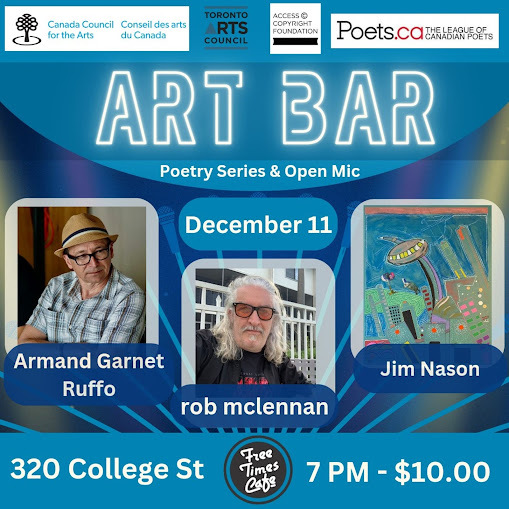

report from the art bar reading series: myself, Jim Nason + Armand Garnet Ruffo,

[Armand Garnet Ruffo, Michael Bryson, a stuffed owl + Jim Johnstone]

[Armand Garnet Ruffo, Michael Bryson, a stuffed owl + Jim Johnstone]It was good to read in Toronto the other night, my first reading at the Art Bar Reading Series in some time, a year to the day I launched my Mansfield Press non-fiction title in Toronto with Stephen Brockwell and Amy Dennis, etcetera [see my report on such here]. Did you know the Art Bar is the longest running poetry-only series in Canada? That is pretty cool: some thirty-some years so far. Currently run by Kate Rogers and Michelle Hillyard, it was a fine evening of readings by myself, Toronto poet Jim Nason and Kingston-based writer Armand Garnet Ruffo, followed by a brief open set of about a dozen poets.

I've read at the Art Bar a few times over the years, at least half a dozen, I'd say, going back to the 1990s. I read with Marcus McCann and Sandra Ridley back in 2010, and with Pearl Pirie and Shannon Maguire a year later, but no other notes from anything earlier, although I've notes from attending a reading back in 2006. I know I read more than a couple of times when it was still held at the old Victory, a Toronto cafe landmark now long, long gone (a venue that also hosted the early days of John Degen's Ink magazine).

I've read at the Art Bar a few times over the years, at least half a dozen, I'd say, going back to the 1990s. I read with Marcus McCann and Sandra Ridley back in 2010, and with Pearl Pirie and Shannon Maguire a year later, but no other notes from anything earlier, although I've notes from attending a reading back in 2006. I know I read more than a couple of times when it was still held at the old Victory, a Toronto cafe landmark now long, long gone (a venue that also hosted the early days of John Degen's Ink magazine). Naturally, I hung out a bit first with my pal Andy Weaver (left; at Dundas and University), and we met up with Stephen Cain for pre-reading dinner, which was good. Did you know Andy Weaver has a fourth poetry title forthcoming with University of Calgary Press (in 2025, I think)? And Stephen Cain has a new one out next fall with Book*hug? You should pay attention to those things.

Naturally, I hung out a bit first with my pal Andy Weaver (left; at Dundas and University), and we met up with Stephen Cain for pre-reading dinner, which was good. Did you know Andy Weaver has a fourth poetry title forthcoming with University of Calgary Press (in 2025, I think)? And Stephen Cain has a new one out next fall with Book*hug? You should pay attention to those things.It was good to see Khashayar Mohammadi, although very briefly. A new title by Mohammadi appears very soon with Pamenar Press, by the way. Jim Johnstone was there also, but you already know about him, right? I've been reviewing his books all over the place lately [two books this year! see here and here]. And Michael Bryson! I haven't seen him in a while (although I'd literally mailed him a package the day prior, so there you go), so I appreciated the opportunity to catch up. His substack, where he posts fiction reviews, is worth following (so you should go do that now).

Jim Nason (above) read from his latest, a poetry title with Frontenac House that even includes some of his artwork on the cover, as well as some newer work. It was especially nice to read with Armand Garnet Ruffo (left), as he'd moved from Ottawa to Kingston a decade or so back (I recall him gifting us multiple bags of baby necessities around the time Rose was born), which means I hadn't really heard him read as often as I had prior. It was good to get a sense of what he's been up to, and he offered a bit of an overview of a handful of his recent titles (including his Governor General's Award-nominated 2019 Wolsak and Wynn title, which I reviewed here), which I appreciated.

Jim Nason (above) read from his latest, a poetry title with Frontenac House that even includes some of his artwork on the cover, as well as some newer work. It was especially nice to read with Armand Garnet Ruffo (left), as he'd moved from Ottawa to Kingston a decade or so back (I recall him gifting us multiple bags of baby necessities around the time Rose was born), which means I hadn't really heard him read as often as I had prior. It was good to get a sense of what he's been up to, and he offered a bit of an overview of a handful of his recent titles (including his Governor General's Award-nominated 2019 Wolsak and Wynn title, which I reviewed here), which I appreciated.

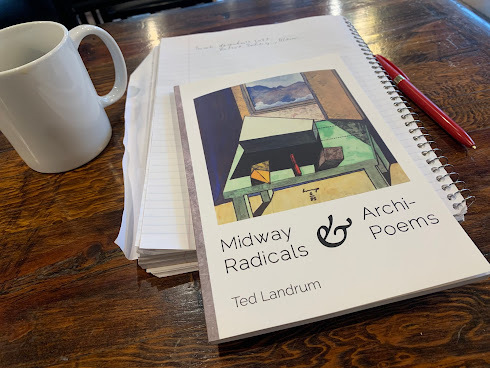

Ted Landrum (newly landed in Toronto from Winnipeg) read in the open set! I hadn't met him prior, and learned he had a full-length debut back in 2017 with signature editions. Did I know about this? I did interview him in my '12 or 20 questions,' so I clearly must have, although I hadn't seen the book before now. I spent part of the following day going through it, and there were some interesting structural things within, playing with lyric form from the perspective of architecture (something he teaches, by the by). After the reading, a couple of us (joined by Toronto poet, translator, critic, editor and publisher Mark Goldstein, which was lovely--everyone needs to read his

Part Thief, Part Carpenter

collection of essays that I reviewed here), we wandered over to a small tavern (cash only? god sakes) for conversation. We considered Grossman's Tavern (where Milton Acorn was presented his People's Poetry Prize back in 1970, you know), but we theorized they might have a very loud band happening.

Ted Landrum (newly landed in Toronto from Winnipeg) read in the open set! I hadn't met him prior, and learned he had a full-length debut back in 2017 with signature editions. Did I know about this? I did interview him in my '12 or 20 questions,' so I clearly must have, although I hadn't seen the book before now. I spent part of the following day going through it, and there were some interesting structural things within, playing with lyric form from the perspective of architecture (something he teaches, by the by). After the reading, a couple of us (joined by Toronto poet, translator, critic, editor and publisher Mark Goldstein, which was lovely--everyone needs to read his

Part Thief, Part Carpenter

collection of essays that I reviewed here), we wandered over to a small tavern (cash only? god sakes) for conversation. We considered Grossman's Tavern (where Milton Acorn was presented his People's Poetry Prize back in 1970, you know), but we theorized they might have a very loud band happening. Oh, and a couple of folk captured some photos of me reading. Here's one by Jim. I focused on reading from the latest poetry title, World's End, (ARP Books), the prior poetry title,

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press) and the opening half or so of the prose sequence "snow day," a chapbook reprinted as part of

groundwork: the best of the third decade of above/ground press, 2013-2023

(Invisible Publishing).

Oh, and a couple of folk captured some photos of me reading. Here's one by Jim. I focused on reading from the latest poetry title, World's End, (ARP Books), the prior poetry title,

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press) and the opening half or so of the prose sequence "snow day," a chapbook reprinted as part of

groundwork: the best of the third decade of above/ground press, 2013-2023

(Invisible Publishing).As well, I did get bored a few nights prior, and created some ridiculous memes as publicity for the reading. I think the Batman one and the first Star Trek are the most effective. Either way, I'll leave you with those.

December 13, 2023

Ongoing notes: mid-December 2023: Jack Davis, Katie Naughton + Yaxkin Melchy Ramos (trans. Ryan Greene,

Isure have been picking up a bunch of chapbooks lately (but I would welcomefurther, as you probably know).

Isure have been picking up a bunch of chapbooks lately (but I would welcomefurther, as you probably know). Calgary AB: Parry Sound ON: The debut publication byMonica Kidd’s Whiskey Jack Letterpress is the gracefully-produced GuillemotsGillemets: AUDUBON IN LABRADOR: some poems (2023), by Parry Sound, Ontario poet Jack Davis. There’s much to celebrate in this lovely and sleekpublication, including the fact that Davis’ work is not only searing in itsattention to detail, and the fact that he doesn’t publish that often [see myreview of his full-length debut, Faunics, published in 2017 by Pedlar Press,here]. A note at the end of the chapbook offers that “This piece is composedsolely of words contained in select entries from John James Audubon’s journalof his travels along the coast of Labrador in the summer of 1833, makingillustrations to complete his BIRDS OF AMERICA.” What is it about Audubon thatalways gets the poets worked up? Not long ago there was BéatriceSzymkowiak’s full-length debut, B/RDS (Salt Lake City UT: The Universityof Utah Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] set as an erasure project of Birdsof America (1827-1838), and even Andrew Steeves mentioned an Audubon project he was working on as part of his own ’12 or 20 questions’ interview(whatever became of that project, Andrew?). There is something intriguing abouthow Davis moves from the short, sharp lyric moment to a continued moment inthis particular seven page, seven poem piece, offering a detail of smallsomehow stretched or continued. The small moment, touching and touching downonce more, again, and continued. As well, there is something reminiscent of RobertKroestch’s own The New World and Finding It (1999) in terms ofletterpress, book structure and poem structure, each page and poem of Davis’work three couplets long, set on the right page:

Inside this linenenclosing a skin of tolerable French

braided with a grouse forits maker

I am of a peaty naturefed by the drainage of

decomposed truths andopinions I would call a song

What I know full well isrenewed every few minutes

like the shy accuracy ofdrawing ‘somewhere’ on a map.

Vancouver BC/Chicago IL: I’m always pleased tosee new work by Vancouver-based American poet Katie Naughton [see also her above/ground press title], and her latest is a second singing (dancing girlpress, 2023), a chapbook-length extended suite of lyric fragments, stanzas andmoments extended across an ongoing stretch and thread and thought. “this is themoment / of crisis / this is / the crisis” she writes, mid-point in thecollection, offering grey spools of lyric across climate, capitalism and the “formalhistories” of personal space, geography, being and loss. As she speaks as partof a recent interview for the Colorado Review blog, referencing herpre-Vancouver time in Buffalo: “At Buffalo especially I’ve been exposed to verysocially conscious poetry, or work that is very interested in thinking aboutpositionality and forces beyond the individual that shape the conditions ofindividual life. I started thinking about how to contain those in poetry, andhow to write from a place of relative privilege or being somewhere in themiddle in a way that doesn’t just reinforce the oppressive system that you areboth negatively affected by and also, at least relatively, rewarded by.”

look at the trees theirAugust shade

from the window of yourlife your one window

from the bedroom from thestairs

you went up and won’tcome down again

the heat, the house, thelaundry and breath

done there

your minutes transit thehouse from the bed

of all Augusts

same silent heat wind sunshade still

of time gathered there,that room

I lay on the floor

your child and not

the blonde wood and whitelinen

soap and ceiling

you had a room once

a bicycle a dusty road

the oak shade the sun

in another state

as children

as I did

do

Houston TX: I’m intrigued by the chapbook WORD HEART(2023) by Mexican and Peruvian-Quechua poet (currently studying in Japan)Yaxkin Melchy Ramos, translated from Spanish by Arizona poet and translator Ryan Greene. According to Greene’s author biography, this chapbook was producedas part of a project to translate (and presumably publish) the first threebooks of Ramos’ five-part “constellation-book,” THE NEW WORLD. I’mintrigued by the lyric Ramos (via Greene) offers, one filled with beautiful optimism;open-hearted, writing light, especially across the dark. Ramos’ narrative “I”is one filled with resolve and optimism, even when wading waist-deep in grief.

BLANKETS

I’m out of my mind when Isleep

because poetry is a song

where your axles singover the asphalt

I travel toward thethought of your mouth

when I see how the hillsrun and

I leave them in my dust

I travel by night

while your stomach isyour heavy heart

and it rolls down thehighway like a ship across the Moon

and you hear an identicalword

and tomorrow will be theday the beds

in the houses

in the hospitals

in the bedrooms

in the childhood kneelingon the blankets

will end up in our heart’sfolds

piling up day after dayunwashed.

December 12, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Meghan Fandrich

Meghan Fandrich

lives with her young daughter on theedge of Lytton, BC, the village that was destroyed by wildfire in 2021. Shespent her childhood and much of her adult life there, in Nlaka'pamux Territory,where two rivers meet and sagebrush-covered hills reach up into mountains. Forthe past decade, she ran Klowa Art Café, a beloved and vibrant part of thecommunity; Klowa was lost to the flames. Burning Sage (CaitlinPress, 2023) is Meghan’s debut poetry collection.

Meghan Fandrich

lives with her young daughter on theedge of Lytton, BC, the village that was destroyed by wildfire in 2021. Shespent her childhood and much of her adult life there, in Nlaka'pamux Territory,where two rivers meet and sagebrush-covered hills reach up into mountains. Forthe past decade, she ran Klowa Art Café, a beloved and vibrant part of thecommunity; Klowa was lost to the flames. Burning Sage (CaitlinPress, 2023) is Meghan’s debut poetry collection.1 - How did your first book change your life? How doesyour most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book is my most recent work and my previousand my all and my only. I had never written poetry before; I had filledjournals, yes, volume after volume through childhood and adolescence and into adulthood,but those were never for any eyes but my own (except once, in the subway inBerlin, when I handed over a journal to the crush whose name appeared on almostevery page and then blanched with horror at what I’d done.) I had never writtenanything that I needed to share.

The first book, Burning Sage, the only book, haschanged my life. Writing it allowed me to finally step into the grief of losingour little town, and sharing it has helped me walk through that grief, and tofeel the support and love around me, and to receive the gift of others’vulnerability and emotion in response to my own.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to,say, fiction or non-fiction?

A first answer:

When I was a child, the quotes that were woven into thebooks of LM Montgomery (“Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam / Ofperilous seas, in faery lands forlorn”) led me to Keats and Tennyson andLongfellow.

When I was a teenager, there was a gift from my dad:his copy of Poems in English, an anthology, inscribed with “Lower Mall,UBC” and a date in the 1960s. I read it cover to cover, and then bought The Norton Anthology of Poetry and read its 2,000 pages too.

When I was a young woman, in a dark tiny shop in Cusco,Peru, a tattoo artist inked “on – on – and out of sight” onto the arch of myfoot. I walked into adult life on that line of Siegfried Sassoon’s.

A second:

A year after the fire, I sat at the typewriter on theliving room floor, thinking I would write a little vignette, a memory, for afriend. And the memory emerged as a poem, and it surprised me. And that poemled to another and another and another – they poured out of me – until thestack of poems became Burning Sage, and I still have no explanation forit, except that there was this intense need to write them, and they could onlybe written as poems.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

It took forty years to start the first project, butthen there was no stopping it. Poem after poem, day after day at thetypewriter, and my fingers typing wildly to keep up with the words as theypoured out.

Most of my first drafts look and feel similar to howthe poems appear in the book; I edited them heavily, but preserved that firstrush of emotion. Night after night I sat with a pencil and pages in hand, whilemy daughter slept in the next room, indenting a line a fraction of an inch orreplacing a single word a dozen times until it was perfect. Editing gave mecontrol over the process, but also over the emotions, the grief, the experience.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Each poem in Burning Sage began as somethingthat needed to come out, just the flash of an image or the hint of a feeling. Iwould start typing with that emotion-memory in my mind, and often be surprisedby where the poem would take me.

I think I knew almost immediately upon writing thefirst poem that it would turn into a book, though. I didn’t have a vision or aplan, just this feeling of story: how each poem was a piece of somethinggreater, something I needed to tell.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Prior to the two months of the Burning Sage booktour, I had never been to a literary reading; I was in Lytton, in a differentlife and a different world. But the book tour was amazing, not so much for mycreative process as for my healing. I shared from my book and from my story andfelt the love and support – and saw the tears and the visible emotion – of theaudience. I am full of gratitude for that experience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I’ve always believed that there will be theoreticalconcerns behind a piece of writing, whether an author intentionally addressedthem or not, and those concerns will be informed by time and place andexperience.

I had no intentions when writing Burning Sageother than to get the memories out of me, but when I went through it afterward,poem by poem, I saw the different currents that run through it. Mediasensationalism, disaster capitalism, the slow-moving cogs of bureaucracy, andhow damaging they each are to survivors of trauma. Love and community and self,even, and how immensely healing they can be. And these currents flow togetherto ask what happens when the climate crisis no longer exists in the abstractdistance – when it moves into the deepest, most personal nearness.

7 - What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

My answer to this question is the same as the last, butin different words. The role of the writer now, as it has always been, is to bringus into others’ lives. At a deep level, all experience is shared experience,and the writer reminds us of that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love editing: it is my dearest geeky pleasure, and asI said above, it was the refining and polishing of my poems that let me turn myraw experience into art. In theory, I know that working with an outside editoris essential, but in practice I’ve found it difficult; I think it’s a matter offinding the right author-editor relationship.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

This: When anxiety is surging, put a hand on yourchest, breathe into the anxiety, and talk to it. “I see you there. What’s goingon?” Sometimes the answer is profound, and identifying it helps. And sometimesthe answer can be “I’m hungry.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I struggle with routines, even as a single parent. Buton our perfect days, my daughter sleeps a little later than me and I sit in thequiet living room with morning light and coffee and my journal, until,inevitably, we’re suddenly running late and everything turns back into chaos.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turnor return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Because I have neverdefined myself as a writer, nor felt any particular need to write (with theexception of those months of writing Burning Sage), there is no suchthing as a stall; there is just gratitude for the moments when, unexpectedly, Iam writing.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The sweet woody vanilla of ponderosa pine bark (withthe sound of cicadas) and the potency of sagebrush just before a summer storm.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Yes. There is a certain feeling in the heart, and itcan come from anything. The memory of a laugh. The evening sky reflected inbroken glass. The voice of a cello that folds around song (I think of AppendixC by Holy Hum / Andrew Yong Hoon Lee). A charcoal drawing. A crow. Pinetrees swaying in summer wind. Blood-stained concrete. Love. And, always andforever, heartbreak.

14 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

- Michael Ondaatje in general, and In the Skin of a Lion inparticular, with the way that language and story wrap themselves around eachother

- On Earth We’re BrieflyGorgeous by Ocean Vuong, which showed me that prose, too, canhurt like poetry

- Rayuela (Hopscotch) by Julio Cortázar, in the original Spanish, which feels like dark redwine and low voices and the flash of a lit cigarette in the night

- Where the Blood Mixes by Kevin Loring (someone from home), with its humour and love andheartbreaking truths

- And, not to be overwhelmedby so many men, Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot and By GrandCentral Station I Sat Down and Wept by Elizabeth Smart, each with its ownbeauty and vulnerability and immense, honest sorrow

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

Why does this question feel more challenging than anyof the others?

I think it’s because the fire taught me not to haveexpectations for the future, when the present can be gone in a moment. What Iwould like to do is what I’m doing now: staying present with my daughter.Making choices for our today, not our hypothetical tomorrow. Teaching her tovalue her own self more than any future goal. And showing her love.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

The fire brought intense trauma and life-alteringgrief, but it also brought gifts. A chance to look at my old life, tore-evaluate, to choose what to rebuild and what not to. Out of that choice camemy burgeoning career as an editor: trauma-informed editing of poetry, prose,and community-focused communication. It’s such an honour to work with others’words, their art.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

That day at the typewriter on the living room floor,there was no choice. And maybe, even if I wasn’t a writer until now, writinghas always been my medium, and language my love.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

A few months ago I opened Exculpatory Lilies bySusan Musgrave, and my heart was submerged. I sat down at the water beside herand cried. And when I closed the bookafter the last poem, truth felt even more necessary, and grief more sacred.

And, because the seven-year-old in the room chooses themovies, the answer to the second question has to be The Grinch, shesays.

19 - What are you currently working on?

At this moment,my daughter and I are in New York City for three months. She has never livedanywhere but Lytton and already a third of her life has been spent on the edgeof a burned-up town. So we’re here in Brooklyn, where there are playgrounds andrestaurants and grocery stores – unfamiliar luxuries – and I can see her worldexpanding.

It will be hardto do any writing here, where there isn’t the break from parenting that schoolaffords, but then the heart aches in a certain way and I think maybe, justmaybe…

December 11, 2023

Ben Meyerson, Seguiriyas

Tekiah Gedolah

Wind through the ram’shorn. Bone-stench,

a blast from the varicosecanal. Stillness

slants the swaying crowd—Iawait the lengthened

tone even once it spillsinto my ears:

the breath is sapped ofair before it ever fills,

stretched and pale to bepreserved, dead but not—

time is a leech that letsthe note like blood,

a year milked out intothe swollen abdomen of history,

its woolen pulse thatebbs from organs out to breath

and back, our corner ofToronto in a holding pattern

of sleep cars, finery,forgetting. Blithe assurance

that we are special. Windthrough the horn.

The call, a musclewrenched beyond

its axis of return. Time isa leech.

I’mintrigued by this full-length debut by poet Ben Meyerson, a poet who currentlysplits his time between Canada and Spain, the collection

Seguiriyas

(BostonMA/Chicago IL: Black Ocean, 2023). Following on the heels of four poetrychapbooks—

In a Past Life

(The Alfred Gustav Press, 2016), Holcocene (KelsayBooks, 2019),

An Ecology of the Void

(above/ground press, 2019) and

NearEnough

(Seven Kitchens Press, 2023)—Seguiriyas is expansive andambitious: composed around a particular musical structure, one with deep culturalties to the Gitanos (the Romani population) of Andalusia. To close the three-page“Al Cante,” he writes: “To live is to be buoyed / without knowledge of thebuoyancy: // a cry that gives and refuses to give. // A cry that accompaniesthe cry.”

I’mintrigued by this full-length debut by poet Ben Meyerson, a poet who currentlysplits his time between Canada and Spain, the collection

Seguiriyas

(BostonMA/Chicago IL: Black Ocean, 2023). Following on the heels of four poetrychapbooks—

In a Past Life

(The Alfred Gustav Press, 2016), Holcocene (KelsayBooks, 2019),

An Ecology of the Void

(above/ground press, 2019) and

NearEnough

(Seven Kitchens Press, 2023)—Seguiriyas is expansive andambitious: composed around a particular musical structure, one with deep culturalties to the Gitanos (the Romani population) of Andalusia. To close the three-page“Al Cante,” he writes: “To live is to be buoyed / without knowledge of thebuoyancy: // a cry that gives and refuses to give. // A cry that accompaniesthe cry.” Ashis “Author’s Note” offers, the “Seguiriyas” of his title “is derived from theflamenco palo (or ‘song form’) of the same name.” Structured with opening poem “Close”and closing poem “Open,” with four numbered sections of poems in between, Meyersoncomposes an assemblage of poems that fit together as thoughtfully as individualpuzzle pieces, or possibly a quilt, all assembled through and around the largermusical structure of the song form. “Take dawn and make it a hinge,” he writes,to open the poem “Daybreak Translation,” “as if night is a shutter to be tugged/ up or down / in the talons of a rock dove, pulled / from above, where thepulsation of wingtips / warps air into pillars banished sharp / against theempyrean cliff, whose summit / is a vertex in the fold / of a face averting.” Thepoems write elements around and through the large subject of placement,displacement and history—a perspective from and a tether between his Torontoupbringing to larger conversations around diaspora—and how cultural memory isheld, passed on and preserved. His opening “Author’s Note” goes on to write:

The seguiriyas palo isknown to draw on solemn subject matter— poverty, displacement, incarceration,mistreatment, and lost love are among the most commonly recurring themes acrossthe extant collection of traditional lyrics, which have emerged out of thehistorical memory, social life and material conditions of the Gitano community inthe Iberian Peninsula. Though the vast majority of flamenco’s oldest lyricswithin palos such as the siguiriya and the soleá (another fundamental song formin the tradition) can only be dated back to the eighteenth and nineteenthcenturies, they often showcase an awareness of events in Andalusia thatoccurred centuries prior, detailing aestheticized interactions with Muslims andMoriscos, who were formally expelled from Spain in 1609, making reference to thehistorical presence of Jews, who were expelled in 1492, and alluding to theheavily discriminatory policies that the central authorities imposed againstthe Gitano population between 1499 and 1783, which led to waves ofincarceration and the forcible conscription of many Gitano men as rowers in thegalleys that carried out the state’s imperial affairs.