Beir Bua Press: Lydia Unsworth, Vik Shirley, Tom Jenks + Anthony Etherin,

WhenTipperary, Ireland publisher Beir Bua Press (2020-2023) announced, seeminglywithout prior warning, whether to the public or to their authors, that theywere suspending publication and pulling books from availability back in June, Iknew I had to get my hands on a few more titles before they disappearedcompletely. Thanks to individual authors, I’d managed to see two titles priorto this two-week warning: Texas-based Irish-Australian poet Nathanael O’Reilly’s pandemic-era BOULEVARD (2021) [see my review of such here]and Hamilton writer Gary Barwin and St. Catharine’s, Ontario writer Gregory Betts’ collaborative The Fabulous Op (2022) [see my review of such here]. Given how quickly the press vanished, it did cause a certain amount ofchaos, especially from authors of relatively-recent titles, but more than a fewhave since been picked up for reissue by other presses: the Barwin/Bettscollaboration and both Beir Bua O’Reilly titles were picked up by Australia’s Downingfield Press, for example, with other Beir Bua titles picked up by Salmon Poetry, kith books, Sunday Mornings at the River and IceFloe Press. The loss of the press isfrustrating, but they accomplished an enormous amount across a relatively shortperiod of time.

Runby Irish poet and editor Michelle Moloney King, Beir Bua Press seemingly appearedout of nowhere, quickly establishing itself as a press willing to take risks onexperimental work across a wide spectrum of style and geography. King clearly hasa fine editorial eye, and the print-on-demand Beir Bua poetry titles were well-designed,looked sharp and included some fantastic writing. To be clear: by shuttering the press so abruptly and allowing her authors no recourse (or prior warning), she did her authors an enormous disservice, and they deserved far better. Either way, given the press disappeared so suddenly,I wanted to at least acknowledge a couple of these titles I ordered back inJune, prompted by that infamous “last call for orders.”

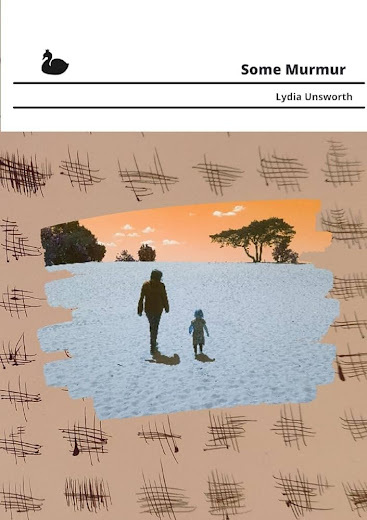

Lydia Unsworth, Some Murmur (2021): I’ve been an admirer of Unsworth’s work for a while (a third above/ground press chapbook is forthcomingnext month, I’ll have you know), and this is a collection framed as onereacting to a sequence of changes in quick succession: moving to Amsterdam fromEngland ten days before the Brexit referendum, and discovering that she waspregnant. As she writes in her prologue: “When I found out I was pregnant, notlong after the Brexit referendum, it felt like a part of me had died and like asecond part of me was steadily dying. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, becausea lot of people feel a lot of things about procreation—about wanting babies,not wanting babies, really wanting babies, having babies, not having babies,really not having babies, how you should have babies, how you should not havebabies—but the way I saw it, from that side of the expansion, was that someunknown and unknowable event was lurching towards me, and its manifestationswere showing up all over my body; rising out, bearing down.” Unsworth appearsto be a poet that engages with projects, whether book-length orchapbook-length, and this collection works to engage with this sequence of new,foreign spaces, reacting to the notion of permanence, and fluidity across whathad previously been fixed. Have you read her take on the prose poem, over at periodicities?She writes of escape, changing forms and sustainability, offering a prose lyricthat manages to articulate these shifting sands even as they move. “Thought itwas wise to stand before the mirror crack,” she writes, as part of the poem “Attemptsto Recover My Previous Form,” “wide like bags of old receipts in supermarketbins. I didn’t compare myself to anyone but how can you not look at all thoseupended trunks trying to hold their bad weather in?”

Lydia Unsworth, Some Murmur (2021): I’ve been an admirer of Unsworth’s work for a while (a third above/ground press chapbook is forthcomingnext month, I’ll have you know), and this is a collection framed as onereacting to a sequence of changes in quick succession: moving to Amsterdam fromEngland ten days before the Brexit referendum, and discovering that she waspregnant. As she writes in her prologue: “When I found out I was pregnant, notlong after the Brexit referendum, it felt like a part of me had died and like asecond part of me was steadily dying. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, becausea lot of people feel a lot of things about procreation—about wanting babies,not wanting babies, really wanting babies, having babies, not having babies,really not having babies, how you should have babies, how you should not havebabies—but the way I saw it, from that side of the expansion, was that someunknown and unknowable event was lurching towards me, and its manifestationswere showing up all over my body; rising out, bearing down.” Unsworth appearsto be a poet that engages with projects, whether book-length orchapbook-length, and this collection works to engage with this sequence of new,foreign spaces, reacting to the notion of permanence, and fluidity across whathad previously been fixed. Have you read her take on the prose poem, over at periodicities?She writes of escape, changing forms and sustainability, offering a prose lyricthat manages to articulate these shifting sands even as they move. “Thought itwas wise to stand before the mirror crack,” she writes, as part of the poem “Attemptsto Recover My Previous Form,” “wide like bags of old receipts in supermarketbins. I didn’t compare myself to anyone but how can you not look at all thoseupended trunks trying to hold their bad weather in?”Stoop

The body bends towardsyou like a plant. You are

my sunshine, my ray of sunshine.What do you call

a plant warped by circumstance?I hold you up to the

light. Ten lifts then tento the side. Environmental

stress weakens the plant.You are heavy fruit. My

stem turns to you, hulkingsunflower head bows

down, seeds fall from myeyes. Wind-blown tree –

frozen in flight. Umbrellainside-out, novelty tie

coat-hangered into aU-turn, leg kicked out high.

Flamboyant ice. Waitingfor a coin in a hat to say

it’s time.

Vik Shirley, Grotesquerie for the Apocalypse (2021): As Shirleywrites in her introduction, the origins of this short collection emerged “outof an intensely creative period in the first year of my PhD, which exploresDark Humour and the Surreal in Poetry. Focussing on the grotesque, I wasimmersed in, and obsessed with, the work of the Russian-Absurdist, Daniil Kharms, and the strange and surreal fable-like poems of Russell Edson.” This isa relatively short collection (why are these books unpaginated?) very muchshaped through the prose poem and prose sentence, and one can see echoes of Edson’swork throughout, with similar echoes that emerge through Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany. As the poem “Husband Ghost” opens: “A hospital rang to tell awoman that her husband was dead. // Not only was he dead, but his body haddecomposed already and he / had progressed straight through to the ‘ghostphase,’ they said. // They told her she should come and collect him.” There aresome interesting echoes, as well, that connect certain of these poems, whetherthe cluster of “Hello Kitty” poems, or poems that open with a similar descriptivestructure. I would very much like to see further pieces by Vik Shirley, and herstatement on the prose poem over at periodicities is worth reading, incase you haven’t already seen (and she does mention that this collection will appear as part of a larger work to appear in 2025, which has yet to announce). In a certain way, Shirley appears to approachher lyric from the foundation of the sentence, opening the collection with poemsthat lean further into line breaks, but soon moving into poems built out of prosepoem blocks, each of which offer short, sketched scenes that twist and turn andfurther twist. The poem “Devil Baby” is a striking example of such, and reads,in full:

A baby started speaking intongues.

“We don’t want a devil baby,”its parents said.

So they put it in adinghy, covered it with foil and set it sail down the Nile.

They were on holiday inEgypt, you see.

It was the worst holidaythey’d ever had.

Tom Jenks, rhubarb (2021): Providing echoes of thework of Vik Shirley, Tom Jenks’ rhubarb also seems a collection of poemsthat focus on the sentence, some of which offer line breaks, with others set ina more prose poem structure. One might say that his poems offer first person narrativesthat seek out their structures. “The horse was revealed to be entirelytwo-dimensional.” the two-sentence poem “opportunities” begins. “This presentedchallenges, but also opportunities.” The prose sentences ofTom Jenks offer first person nararatives, movingback and forth from short, sketched bursts, expansive open form poems toclustered prose blocks. There’s such a wry delight in sound and syntax across these poems that are intriguing, and the collection exists as a kind of collage on form, moving from the expansive open lyric to densely-packed short burst. I’d only seen Jenks’ visual works prior to this, so amnow quite fascinated by what he is exploring through his sentences: a kind ofsurreal swirling of narrative twists and turns, one that is open to the experiment-as-it-occurs. I am very interested in seeing where else his poems might find themselves.

scissors

Syrop on soya, the squareholes in waffles,

cheesy dumplings, ancientgrain rolls,

I don’t know what to makeof any of it.

All the elements for agood life are in place,

yet a good life is notbeing lived.

We should rethink the solarsystem

or buy each othershoulder bags.

I saw a dog that was entirelysee through.

I’ve got a ride on mower

but I still use scissors.

Anthony Etherin, Fabric (2022): Another author published previously through above/ground press, “experimental formalistpoet” Anthony Etherin, a poet, editor and publisher who lives “on the border ofEngland and Wales,” offers a cluster of poems in Fabric that continuehis strict adherence to formal poetic structure, engaging with such as theacrostic, anagram, lipogram, palindrome, villanelle, sonnet and ambigrams, evento the point of brevity, as some were composed with the Twitter/X limit of 280characters/140 characters in mind. “Fit one sent rule:,” the final couplet of “SonnetFuel” reads, “Tier sonnet fuel.” Part of what is always interesting in Etherin’songoing work is in seeing just how far it is possible for him to continueacross such highly-specific formal paths, and the wonderful variations thatemerge through his collections. The overt brevity is interesting as well,offering new layers to his ongoing structures. In his introduction, he offersthat “The poems of Fabric [a book he posted online as a free pdf, by the way] are at ease with their poemhood. Some discusspoetry itself, while others are more introspective, eager to evaluate theprinciples and rules by which they were constructed.” They are at ease withtheir poemhood, highly aware of their structures, as the collision of sound andmeaning provide the delight of what formal possibilities might bring.

Anthony Etherin, Fabric (2022): Another author published previously through above/ground press, “experimental formalistpoet” Anthony Etherin, a poet, editor and publisher who lives “on the border ofEngland and Wales,” offers a cluster of poems in Fabric that continuehis strict adherence to formal poetic structure, engaging with such as theacrostic, anagram, lipogram, palindrome, villanelle, sonnet and ambigrams, evento the point of brevity, as some were composed with the Twitter/X limit of 280characters/140 characters in mind. “Fit one sent rule:,” the final couplet of “SonnetFuel” reads, “Tier sonnet fuel.” Part of what is always interesting in Etherin’songoing work is in seeing just how far it is possible for him to continueacross such highly-specific formal paths, and the wonderful variations thatemerge through his collections. The overt brevity is interesting as well,offering new layers to his ongoing structures. In his introduction, he offersthat “The poems of Fabric [a book he posted online as a free pdf, by the way] are at ease with their poemhood. Some discusspoetry itself, while others are more introspective, eager to evaluate theprinciples and rules by which they were constructed.” They are at ease withtheir poemhood, highly aware of their structures, as the collision of sound andmeaning provide the delight of what formal possibilities might bring.

Tautograms

The tautogram ties

terms to their typography–

tightening this text.