Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 69

December 10, 2023

Spotlight series #92 : Kyla Houbolt

The ninety-second in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring California poet Kyla Houbolt.

The ninety-second in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring California poet Kyla Houbolt.

The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace and San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa.

The whole series can be found online here .

December 9, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mandy-Suzanne Wong

Mandy-Suzanne Wong is a Bermudian writer of fiction and essays. Her novels include The Box, a Bustle Best Books selection, and Drafts of a Suicide Note, aForeword INDIES finalist and PEN Open Book Award nominee. Awabi, herduet of short stories, won the Digging Press Chapbook Series Award; and heressay collection Listen, we all bleed was a PEN/Galbraith nominee andASLE Book Award finalist. Her work appears in Black Warrior Review, ElectricLiterature, Literary Hub, Litro, Menagerie, SuperstitionReview, and Necessary Fiction and has won recognition in the Best ofthe Net and Aeon Award competitions.

She is represented by Akin Akinwumi (aakinwumi at willenfield dot com) at Willenfield Literary Agency.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book, Awabi, a duet of short stories, won the inaugural Digging Press Chapbook Series Award. It was my first opportunity to work with an editor, the greatGessy Alvarez, from whom I learned so much. She gave me the confidence to developsome of Awabi’s characters into protagonists of mycurrent novel-in-progress, of which the lead character, Ayuka, daily brings mejoy.

2 - How did you come tofiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Since my earliest days,all my favorite books have been novels; and it’s reading other books that makesme want to write them. Fiction has always been a refuge for me, a way ofgetting out of myself.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It depends on the project.All my books begin as reams of handwritten notes; but whereas my novel TheBox came together in less than a year, with the final manuscript bearing asurprising degree of resemblance to the first drafts, Ayuka’s novel is alreadyin its third major overhaul.

4 - Where does a prosework usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

Again, it depends. TheBox and my first novel Drafts of a Suicide Note were conceived asnovels, the novel form being my first love as a writer and my favorite kind ofbook to read. My short story “The Indoor Gardener,” though its acceptance forpublication preceded that of The Box, began as an excerpt from thatnovel. Ayuka’s novel, though, is arising from short stories.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy givingreadings, but I also find it terrifying. I’ve been fortunate in my audiences,which for the most part have been encouraging rather than discouraging. But Iprefer only to give readings of work that’s already settled into itself.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I seem to be obsessed withanti-anthropocentrism. Even when the first spark of a project is a humancharacter, some nonhuman thing or phenomenon, like the handful of paper in Draftsof a Suicide Note, shows up to undermine the human characters’ agency andself-control. Dispelling the human from the center of our imaginative universesis vital: it has long been time to put other Earthlings first and to admit thatwithout, for example, a healthy Ocean, our species will not survive. It’s ourspecies’ hubris, believing humans to be the most important beings on Earth,believing ourselves to be entitled (by virtue of nothing whatsoever!) toexploit and consume everything else, that’s directly causing global ecological collapse.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Literature has the abilityto pinpoint and question the ambiguities inherent to each and every moment;great writing discovers beauty in ambivalence, complexity, even contradiction.In today’s egocentric, exclusionist, and exploitative cultures where simplisticdemagoguery and unquestioning cancelations decide what counts as “freeexpression,” ambiguity is suffocated at every turn—and yet, it may be the onlytruth.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve been really fortunateso far in that the best, most talented, professional, and companiable editorshave wanted to work with me; and they have shared my determination to make thebook or story of the moment its best self. Even when that self is weird anddoesn’t “fit in.” They’ve also relished joy and laughter as integral parts ofthe process, and that is so important.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

From Grace Paley in TheParis Review, an interview to which my awesome editor Yuka Igarashi drew myattention: “One of the first things I tell my classes is, If you want to write,keep a low overhead. […] Don’t live with a lover or roommate who doesn’trespect your work. […] Write what will stop your breath if you don’t write.”

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (short stories to essays to the novel)? What doyou see as the appeal?

I wouldn’t say that movingbetween forms has ever been easy for me. Novels and short stories require verydifferent strategies for timing and pacing; essays are beholden to thingsbeyond themselves to a greater extent than fiction. These constraints present specificchallenges and opportunities that preclude effortless flowing between forms. ButI do aspire to such flexibility in my writing; I don’t want my work to fallinto unbreakable patterns. That means continuing to experiment with form,genre, language, subject matter beyond my comfort zones. Each project has somethingnew to teach me.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I try to keep to aneight-hour workday just as I would in any profession, but that doesn’t alwayspan out. Each morning begins with some sort of caffeinated beverage and a phoneconversation with my mom, almost always about books!

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

From the edge of writerlydespair, I turn to other writers’ books. Anything with beautiful prose mighthelp me to stave off panic and regroup—to find, if not exactly inspiration, thecourage and desire to carry on searching for ideas.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Seaweed in salt water.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Other-than-humanEarthlings, including boxes, snails, sounds, artworks, buildings, shapes, andtheoretical or scientific papers, are vital influences on my writing. I tend tothink about language in musical terms; my sentences prioritize rhythm, timbre,tone, breath, phrasing . . . Even though I’m not a poet, the way a piece lookson a page, even in manuscript, is also an important consideration for me.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Ah! You got me started.This list could go on for reams. Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, Clarice Lispector, Sofia Samatar, Andrei Platonov, Antoine Volodine, Lev Tolstoy, Mark Haber, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Fernando Pessoa, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, Salman Rushdie, Amina Cain, Terry Pratchett, Mieko Kanai, Marie N’Diaye, Maxim Osipov,Chinua Achebe, Maria Stepanova, Yoko Tawada, W.G. Sebald, Maaza Mengiste, Yoko Ogawa . . .

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

I wish I understood Greek,Japanese, Russian, Portuguese, and German, and I wish I could improve mytotally inadequate French and Italian. If only such things came easily.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Had I not decided to throwcaution to the winds, throw over my education and common sense, and become awriter, I would’ve ended up a miserable musicologist or piano teacher wishingdaily for the world to end me.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

Can’t help it. Can’t stop.Tried to stop and (see question 17) shan’t try again.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Right now I’m reading twophenomenal novels for blurbs. Watch for both of them in 2024! Lesser Ruins byMark Haber (forthcoming from Coffee House) is an inimitable digression ondigression, grief, and techno that curls and stretches language in ways thatEnglish doesn’t often dare. The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan(forthcoming from Counterpoint) looks obliquely at McCarthy-era artworlds whileexperimenting elegantly with the very idea of “plot,” with what makes a story alove story, and of course with color. Films haven’t been doing it for me lately,but Nathan’s novel may just make me want to take another look at Old Hollywood.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

Inaddition to Ayuka’s novel, I’m working with several writers and artists on TheTubercled Blossom Pearly Mussel Memorial Library of Hope, which I wasinvited to create for Delisted 2023; an international artisticcollaboration curated by Jennifer Calkins in honor of twenty-one nonhumanspecies that were recently stricken off the US Endangered Species List anddeclared extinct, relieving the US Government of the obligation to either seekthem out or preserve their habitats.

December 8, 2023

Nikki Reimer, No Town Called We

Fear Is, Um, Part of Love

an insect’s eye is how webegin

we’re thick with it

fear with

riotous cones and rods

how we melt into it

sick with

worry into muddled

now you see

not fear but

one dozen refractions of

the other’s body

blink again, whoops

followed one dozen arms

to their logical conclusion

now we don’t

Thelatest from Calgary poet and editor Nikki Reimer—following the tradecollections

[sic]

(Calgary AB: Frontenac House, 2010) [see my review of such here],

DOWNVERSE

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here] and

My Heart Is a Rose Manhattan

(Talonbooks, 2019) [see my review of such here], and chapbooks

fist things first

(Windsor ON: Wrinkle Press, 2009), that stays news(Vancouver BC: Nomados Literary Publishers, 2011) and

BEHIND THE DRYWALL

(Gytha Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]—is

No Town Called We

(Talonbooks,2023), published alongside the companion above/ground press visual chapbook,

Dinosaurs of Glory

(2023). Composed across a quartet of lyric clusters—“No TownCalled Poetry,” “The Daily We,” “One Poet Always Lies” and “The iLL Symbolic”—NoTown Called We is a suite of lyric experimentation and cultural discourse,working to orient and even articulate oneself amid a field that pushes an insistenceto keep moving, move forward and do not question. “consciously enter the stateof we,” the poem “Keep on Truck” ends, “via this inherited truck / in the landof trucks and honey / to keep moving: / just keep moving [.]” If David Martin’srecent Kink Bands (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] examined considerations of the underground, including minerals andtheir extraction, Reimer examines the effects of those very extractions uponthe land, the landscape, the people and multiple cultures above ground. As shewrote specifically of that companion chapbook in periodicities: a journal ofpoetry and poetics: “Resistance, too, might take the form of art practice,a deliberative contemplative act that refuses to be yoked to the wheel ofcapitalism. Not product, but practice. Listening to the bees while turning yourpain into art. And together these methods of resistance might become a kind ofagnostic prayer.”

Thelatest from Calgary poet and editor Nikki Reimer—following the tradecollections

[sic]

(Calgary AB: Frontenac House, 2010) [see my review of such here],

DOWNVERSE

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2014) [see my review of such here] and

My Heart Is a Rose Manhattan

(Talonbooks, 2019) [see my review of such here], and chapbooks

fist things first

(Windsor ON: Wrinkle Press, 2009), that stays news(Vancouver BC: Nomados Literary Publishers, 2011) and

BEHIND THE DRYWALL

(Gytha Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]—is

No Town Called We

(Talonbooks,2023), published alongside the companion above/ground press visual chapbook,

Dinosaurs of Glory

(2023). Composed across a quartet of lyric clusters—“No TownCalled Poetry,” “The Daily We,” “One Poet Always Lies” and “The iLL Symbolic”—NoTown Called We is a suite of lyric experimentation and cultural discourse,working to orient and even articulate oneself amid a field that pushes an insistenceto keep moving, move forward and do not question. “consciously enter the stateof we,” the poem “Keep on Truck” ends, “via this inherited truck / in the landof trucks and honey / to keep moving: / just keep moving [.]” If David Martin’srecent Kink Bands (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] examined considerations of the underground, including minerals andtheir extraction, Reimer examines the effects of those very extractions uponthe land, the landscape, the people and multiple cultures above ground. As shewrote specifically of that companion chapbook in periodicities: a journal ofpoetry and poetics: “Resistance, too, might take the form of art practice,a deliberative contemplative act that refuses to be yoked to the wheel ofcapitalism. Not product, but practice. Listening to the bees while turning yourpain into art. And together these methods of resistance might become a kind ofagnostic prayer.”Reimer’sis a lyric that has been increasingly open and engaged on deeply personalmatters of grief, fear, loss and anxiety, examining death, climate crisis and capitalismgenerally, and Alberta’s oil production and ensuing climate devastations and overtcultural loss through the capitalist engine more specifically, as well as herongoing grief following the sudden and unexpected loss of her brother. In NoTown Called We, she speaks of direct human consequence upon the land andlandscape, the responsibilities and failures of humans generally, and evenpoets, specifically, offering the poem “But the Moon” as a kind of complaint ondistraction, focused on what is happening in the sky instead of here on theground. “What exactly did you think the moon was going to do for you, poet?”she writes. “Why are you writing these words, line by line by line?” As Reimerwrites to open the poem “Plants We Have Killed”: “what duty of care do we oweeach other? // when embodiment stands in / for direct action?”

December 7, 2023

Ongoing notes: Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks: J-T Kelly + Mark Statman,

I’vebeen seeing these Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks that Jordan Davis has beenproducing out of Brooklyn for a while now—see my review of Buck Downs’ GREEDYMAN: selected poems (2023) here and Nada Gordon’s The Swing of Things(2022) here—so I’m pleased to see copies of J-T Kelly’s LIKE NOW (2023)and Mark Statman’s CHICATANAS: SELECTED POEMS (2023) appear at my door.

I’vebeen seeing these Subpress Collective/CCCP Chapbooks that Jordan Davis has beenproducing out of Brooklyn for a while now—see my review of Buck Downs’ GREEDYMAN: selected poems (2023) here and Nada Gordon’s The Swing of Things(2022) here—so I’m pleased to see copies of J-T Kelly’s LIKE NOW (2023)and Mark Statman’s CHICATANAS: SELECTED POEMS (2023) appear at my door. Thechapbook debut by Indianapolis poet and innkeeper J-T Kelly, LIKE NOW, offersan assemblage of short lyric first-person narrative and layered accumulations thatsway and play, such as the short poem “Plunder”: “Pomegranate—ripe, / Unbroken—// I, too, hide my heart— / Fruitlessly.” There’s something of a disjointedlyric reminiscent of Canadian poets Stuart Ross, Gary Barwin and Alice Burdick,each composing poems that lean into disconnections, connections and surrealthreads and sly humour across the short lyric. I’m curious in how Kelly’s poemsform across such narrative disjoints and jumbles, and how these pieces shape themselvesnot simply through a completed thought run all the way to the end, but one thatrests somewhere in the middle, allowing the reader the space through which tocomplete on their own. I am intrigued by these poems of J-T Kelly.

West

What I said when I wasleaving.

Your friends and theirboots.

I left it there on thekey stand.

The road is dry. But I stillthink about

standing on the on-rampoutside of Bismarck.

At the mercy of. Sometimesforty-five miles

from a pay phone. I wentnorth because

Zach didn’t listen andhad gone south.

He had been picked up andtaken to some field.

They tried to set him onfire, but the gasoline

dissolved the adhesiveand he broke free.

The wheat so near toharvest must have swayed majestically

as he ran, pain in hiseyes, suffocating,

And deciding to finishgrad school, which he did.

You, it turns out,consider me to be.

The headlights extendsideways out of the low stalks of winter

wheat.

The passenger seat holdsmy fur-lined leather mittens

and your anthology ofpoetry from The New York school which I

will not give back.

You can go to hell. I’m goingto Seattle.

Ihadn’t actually heard of New York-based American writer, poet and translator Mark Statman before seeing this new title, although the acknowledgments of CHICATANAS:SELECTED POEMS offers that he is the author of six poetry collections, twoworks of prose and has translated collections by Federico García Lorca (withPablo Medina), José María Hinojosa and Martín Barea Mattos. I’m fascinated bythe idea of the chapbook-length selected poems, something Davis has beenexploring for some time (there was also the chapbook-length Stuart Ross bilingual Spanish/English ‘selected’ I reviewed recently, published in Argentina), and I would almost think that putting together a chapbook-lengthselected would be far more challenging than attempting one book-length, even beyondthe consideration of weighing the possibility of ‘best’ against potential ‘representativeof this author’s work,’ etcetera. I’m curious as to how the poems in thiscollection might be representative of Statman’s larger canvas of writing,offering first-person lyric musings via hesitation, soft and slow unfolding ofnarration. There’s a slowness here his lines and breaks require, both firm andthoughtful, never in any particular hurry, because you’ll get there in the end,either way, whether losing a poem through a young woman’s accent (“the disappearanceof the poem”) or a piece on the death of Kenneth Koch, that opens thecollection, “Kenneth’s Death,” that begins: “he’s dead and / I still don’tbelieve: / years later / I’m walking someplace / and I’ll think / this issomething / I’ll tell him / when he gets back / when he gets back / as thoughwhere Kenneth’s gone / is simply too far away / to telephone or / send apostcard [.]”

chicatanas

some mysteries have

to be that way

Alma asked me yesterday

if I was going to

the casita today

was I going to harvest

our chicatanas

giant ants from

whose toasted bodies

legs and heads removed

Alma makes a

sharp spicy salsa

the chicatanas onlycome out

once a year and everyyear

since we bought the

casita we’ve had them

they emerge before dawn

the ground wet it’seither

on the 24th or25th of

every June St. John’s Day

I ask Alma

but how do you know

which day 24, 25 and she

smiles and says because

the morning after

the dawn fills with

small white butterflies

December 6, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Mary Leader

Mary Leader [photocredit: Margaret Ann Wadleigh] began writing poems around age forty in themidst of a career as a lawyer, working for the Oklahoma Supreme Court. She left home to earn a PhD in English andAmerican Literature from Brandeis University, published her first book, RedSignature, and went on to teach, primarily at Purdue University in Indiana. Retired now, she has returned to Oklahoma toread and write full-time. Her Britishpublisher is Shearsman Books. Shearsman hasbrought brought out three of her collections, most recently her fifth book, The Distaff Side, and will also publish her sixth book, The Wood That WillBe Used, in 2024.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book, titled RedSignature, was chosen for the National Poetry Series and was published byGraywolf in 1997. I was 49, so my viewof the world (jaundiced) and of myself (knowing "in myheart" that my poems were real) combined to mean I was never reliant onpublication as representing any kind of meaningful judgment pro or con. On the other hand, I was penniless, and thebook allowed me to get a tenure-track University teaching job. That was a big plus.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Circuitously, andlate. I married at 20 and had one babyseven months later and another two years after that. As they grew up, I started taking collegeclasses, and decided fiction was my direction. I went to law school, though, and worked as a lawyer until the kids weregrown, then had my stereotypical midlife storm. I came out of that writing poems.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

To be honest, I am notsystematic enough in my writing to be able to answer those questions. I notice dust on a neglected knickknack on adusty shelf, next to a pile of paper not covered with dust but not presentableeither. It's a wonder anything evercoheres, but it does, and from my language-busy brain things like poems, andultimately the parameters of projects, emerge. Then I further mess with connecting my old writing over the years withnew ideas for pushing this way or that.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Well, in saying I couldn'tanswer that last question, I seem to have answered this one!

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I love doingreadings. My road not taken? anactress. I adore voices.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Again picking up from "voices"from the last question, the biggest theoretical concern I don't have,and never have had, is the prescription to "find your voice." For me, that's not the task of poetry. Utterance that comes out has to do with the intersectionsof imagination and memory and language and form. Voice as identity? having just one? well,that's not a process I believe in. Ibelieve in engagement at intersections, with other minds and with weather.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I get nothing, personally,by placing the tips of my third-and-fourth fingers on the wrist ofculture. I know there's a pulse therebut it is so huge and so complex, I can't deal with it. Only language and the art of using it is therealm I have access to. Infinitewriters, manifold roles, make up reality for me. It may or may not have a public aspect, butfor me, not so much. It's abstract. It's a belonging to consciousness. Culture and consciousness overlap, I suppose,but on different levels of our times and spaces.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

At least one readeris essential. Editors doing what they do— putting out magazines and books and webpages and so on — I find pleasant towork with on those things, especially Tony Frazer of Shearsman Books. Seeing the book into print is an importantjob and I personally am quite keen on the book form as a thing of beauty.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Always consider — don'talways do it but consider — removing first lines and last lines. Those are the two most popular places fortelling a lie. Sometimes, they can beswitched instead of being removed. Oh,and read poems line by line up from the bottom. That helps you, over years, get a sense for shapeliness of line. Once in a blue moon, the whole poem is betterthat way.

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I wake up early and firstthing, I stagger to my chair and boot up my laptop. I do word puzzles on the New York Timeswebsite (saving the news for afternoon or evening) and jigsaw puzzles onLenagames.com, Lena being a Russian. This drill lets me wake up and see how my brain is doing. If it's perking, I turn to the hard stuff ofcomposing language and editing it, almost "playing poems" as a game. If my brain is sluggish, I do corollaryactivities such as corresponding with someone or flipping through a book ofpoems or making my bed. I wish I knewanother language. I'd enjoy translationas another kind of game. See, HomoLudens, by Johan Huizinga.

11 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I'm retired, so betweenreal writing and fooling around, there's always something to do. Attention produces inspiration. I also have fallow periods, but that is goodtoo.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Childhood home? cigarettesmoke. Where I'm from, and have returnedto? Oklahoma has a dry smell of grass when it gets parched at the end of thesummer, and a juicy smell when cut, come spring.

13 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Those four richlyavailable sources — evergreen — support me as a writer, but tangentially. They're all worth pursuing and that pursuit, howeveramateurish, deposits impressions and details that will pop up duringcomposition or revision. But I also seewhere McFadden is coming from. A book isinconceivable unless another book exists and is known to a person who wouldproduce one. It's a Plato thing.

14 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

When, as a lawyer, I firsttook up the notion of poetry, I studied from Norton anthologies. I treated them as catalogues of designs Iwould like to try my hand at, drawn to form. I relished the patterns of George Herbert and shapes of May Swenson, the ventriloquism of T. S. Eliot and thedocumentary technique of Muriel Rukeyser. Poets close to my heart are Eleanor Ross Taylor and Gwendolyn Brooks.

15 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

Edit and write anintroduction to a Selected Poems by my mother, Katharine H. Privett.

16 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Actress. But you can't do that alone.

17 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

I did other things first,and did not have anything to do with writing (other than legal writing) until Iwas nearly 40. What made me write thenwas having a psychotherapist ask me what made me happy as a child. I burst into tears. Making art was the answer, mostly visual butalso some little stories or poems or plays. I have practiced drawing as an adult, but I realized I couldn't do thework that artists do unless I made language my medium. Possibly to do with my mother being extremelyverbal, with poetry as her core.

18 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

At 75, I read and watchfilm mostly for entertainment. Have youseen Derry Girls on netflix? Knowing what is great in these departments is no longer very operationalfor me. I do serious reading, though, ofthe Hebrew and Christian Bibles, in small pieces — as if poetry — at my LectioDivina group. We meditate in silence,contemplate, read slowly and intensively, and finally talk about it.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

I am polishing my nextbook, titled The Wood That Will Be Used, which is due out from Shearsmanon September 1, 2024. I am going throughthe boxes and piles of paper in an effort to make sense or an archive(whichever comes first), of literary materials from my life. And I have some nascent stories, which I amendeavoring to bring into short prose or long poetry.

December 5, 2023

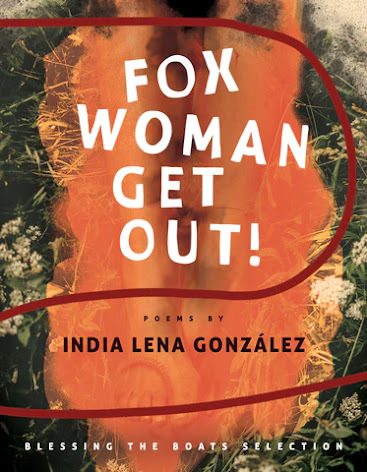

India Lena González, Fox Woman Get Out!

fox womansaunters back

i amloose-limbed woman

sudden on my black-tippedtoes fine ears and underfur

wind between trees

i’ve been stuck in this viridescentlandscape

a hazy film where istrike along the base of forest

where my cunning becomesfeminine

i am praying for all thebodies

i am asking for light

i am asking to get out ofthis verdant dreamscape

i did not mean to outrunyour gun

with your eyes fixed onmy snout

you wanted flattenedskull and underfur

i did not mean to scream

the way a woman does indistress

i did not mean to ravageyour inner flesh

i am praying for all thebodies

i am asking for light

i will not wound youagain

i am too many

trees between wind

long jagged teeth

someone’s reddish brown love

I’mintrigued by this full-length debut by Harlem, New York-based poet India Lena González,the expansive

Fox Woman Get Out!

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), acollection held together through a blend of simultaneously wild and preciseenergies. “i do not feel big mother sitting at the foot of my bed with all ourother ancestors,” she writes, towards the end of the poem “MAMI : a chest for healing,” “so forgive me as i golooking in all the earthly places / you’ve got that divine prerogative / i’mstuck at planet level [.]” González explores and articulates growing up andbody comfort, ancestors both distant and immediate, and a self of blendedhistories and threads, enough that one can’t easily keep track of much beyondthe speculative, and what can be immediately seen. “nobody is a purebredanymore,” she writes, to close the poem “una parda, which is me,” “i’m precociousmutt / i know all about the small living quarters for / tender-tribed-peoplelike me / the people-with-too-many-ancestors-inside-of-us / we have now paintedour living room / we chose the color of bloodied-up hide / we chose us [.]” Shespeaks to both the living and the dead, composing lyrics that are deeply physical,offering a propulsive energy and veritable heft, occasionally utilizing ALLCAPS across line breaks and prose poems. She both asks and answers the questionof who she is and where she is from, a stylized and expansive lyric acrossgenerations and the length and breath of the page with a stylish, energized anddeeply thoughtful expansiveness. Is she woman or wild beast? Perhaps, in herown way, she is both?

I’mintrigued by this full-length debut by Harlem, New York-based poet India Lena González,the expansive

Fox Woman Get Out!

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), acollection held together through a blend of simultaneously wild and preciseenergies. “i do not feel big mother sitting at the foot of my bed with all ourother ancestors,” she writes, towards the end of the poem “MAMI : a chest for healing,” “so forgive me as i golooking in all the earthly places / you’ve got that divine prerogative / i’mstuck at planet level [.]” González explores and articulates growing up andbody comfort, ancestors both distant and immediate, and a self of blendedhistories and threads, enough that one can’t easily keep track of much beyondthe speculative, and what can be immediately seen. “nobody is a purebredanymore,” she writes, to close the poem “una parda, which is me,” “i’m precociousmutt / i know all about the small living quarters for / tender-tribed-peoplelike me / the people-with-too-many-ancestors-inside-of-us / we have now paintedour living room / we chose the color of bloodied-up hide / we chose us [.]” Shespeaks to both the living and the dead, composing lyrics that are deeply physical,offering a propulsive energy and veritable heft, occasionally utilizing ALLCAPS across line breaks and prose poems. She both asks and answers the questionof who she is and where she is from, a stylized and expansive lyric acrossgenerations and the length and breath of the page with a stylish, energized anddeeply thoughtful expansiveness. Is she woman or wild beast? Perhaps, in herown way, she is both?BELUGA

i remember when your bones outgrew your skin

mama rubbing fermented banana leaf

like a prayer all over you

who goesfirst this time?

hermanita

siempre hemos sido ballenas beluga

pero qué más sucededespués?

very blue water

& the echo of our great twin mouths

December 4, 2023

andrea bennett, the berry takes the shape of the bloom

When people said stay hungryI thought they

meant it literally, stayhungry because that was

the price of being thin. Whenthey said salad

days I thought itmeant the days when we were

young enough to be alwayshungry and only

eating salad. I can tellyou how many calories

are in an apple and howmany calories make

up a pound. I can tellyou how many pounds

my mother weighs and howold I was when

I surpassed her weight. Theonly time I was

thin the thinness camebecause I was sick and

couldn’t eat. When the sicknesslifted I felt relief

and sadness. When peoplesay unhealthy they

mean fat. When people sayunhealthy they do

not mean what unhealthyhas done to my brain.

Thelatest from British Columbia poet, writer and editor andrea bennett is the poetrytitle

the berry takes the shape of the bloom

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks,2023), a book-length lyric suite comprised of untitled, accumulated fragmentsthat cohere into a loose kind of narrative arc. Following bennett’s full-lengthdebut

Canoodlers

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2014) [see my review of such here] and more recent essay collection,

Like a Boy but Not a Boy

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020), there is something about bennett’slyric, bennett’s line, that refuses to remain static. “I had a temper so hot itcould fry an egg.” they write, early on in the collection. “Like a / keybreaking off inside a rusted U-lock. Like an / unanchored bookshelf in anearthquake. Like a / crow picking a fight with an eagle.” Offering a blend of lyricbend and first-person memoir, these poems rush and run electric across acollection that originated, as the back cover offers, “as a gesture towardsoptimism after loss, pain, difficulty, and fear. It began as a linearnarrative, offering a window into one trans person’s life after they feltcontented and secure. But in the end these poems, which capture particularmoments in time, may recur in any given present: sometimes what surfaces is anxietyor anger, sometimes love or eagerness.”

Thelatest from British Columbia poet, writer and editor andrea bennett is the poetrytitle

the berry takes the shape of the bloom

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks,2023), a book-length lyric suite comprised of untitled, accumulated fragmentsthat cohere into a loose kind of narrative arc. Following bennett’s full-lengthdebut

Canoodlers

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2014) [see my review of such here] and more recent essay collection,

Like a Boy but Not a Boy

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020), there is something about bennett’slyric, bennett’s line, that refuses to remain static. “I had a temper so hot itcould fry an egg.” they write, early on in the collection. “Like a / keybreaking off inside a rusted U-lock. Like an / unanchored bookshelf in anearthquake. Like a / crow picking a fight with an eagle.” Offering a blend of lyricbend and first-person memoir, these poems rush and run electric across acollection that originated, as the back cover offers, “as a gesture towardsoptimism after loss, pain, difficulty, and fear. It began as a linearnarrative, offering a window into one trans person’s life after they feltcontented and secure. But in the end these poems, which capture particularmoments in time, may recur in any given present: sometimes what surfaces is anxietyor anger, sometimes love or eagerness.” I dreamed we abandonedour anxious life for a

different one in Phoenix.I imagined a campus

of new buildings, tryingto look old. We lived

together in a concretesingle: one bed, two desks,

and a hot plate. Whereis the library? The dream

was supposed ot mean wecould leave, but it also

meant we could neverstart over. I palmed the

concrete hallway and gotstuck in its pores.

“Iforget what poetics are.” bennett writes, towards the end of the collection. “Iforget the word for / the study of knowledge. I need a phrase when / the wordis a thing unto itself, a special ornate / thing in itself. I work in thekitchen, where I / make the food.” Deeply personal and exploratory, bennett composesa book-length meditative thread that examines a variety of shifts of being fromwithin, writing partners and ex-partners, pregnancy and mothering, all of whichare enormous enough shifts on their own, but all through the lens of becomingthe person they were meant to become: opening up as transgender, and the shift,as Mercedes Eng writes on one of the blurbs on the back cover, “from daughterto not-daughter,” and the difficulties of the author’s mother, a character unwillingto adapt, and perhaps, frustratingly, best left behind. There’s a lot going onwithin the bounds of this book-length poem, writing anger and acceptance,witness and loss, running the gamut from wild uncertainty and rage to acceptanceand clear confidence.

My mother haunts themargins of my life.

My mother said I always,I never, I always. My

mother got angry like thesky changes before

a summer storm. My motherbought clothing

four sizes too small fora daughter she didn’t

have. My mother said begrateful. My mother

said what you don’t know.My mother said I

was difficult. My mothersaid I was just like my

father. My mother sleptwith my best friend’s

father, my mother said I couldn’tstop working

at my best friend’sfather’s store, my mother

slapped me across theface. My aunt said please

stop writing about yourmother andthe next day

I read aloud, at afestival, all the worst poems I’d

ever written about mymother.

December 3, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nina Mosall

Born in Surrey to Iranian refugees, Nina Mosall attended Kwantlen Polytechnic University and the University of British Columbia, in which she obtained her BA in Creative Writing and MA in Library Studies. Currently working as a librarian, she writes poetry during her spare time when she is not singing and reading to babies, or helping seniors figure out how to use cell phones. Her poetry and short stories have appeared frequently in Kwantlen Polytechnic University's literary magazine, Pulp, and in the literary magazine,

Event

.

Bebakhshid

is her debut poetry collection, which explores Middle Eastern identity, immigration, familial relationships, and the romance of everyday life.

Born in Surrey to Iranian refugees, Nina Mosall attended Kwantlen Polytechnic University and the University of British Columbia, in which she obtained her BA in Creative Writing and MA in Library Studies. Currently working as a librarian, she writes poetry during her spare time when she is not singing and reading to babies, or helping seniors figure out how to use cell phones. Her poetry and short stories have appeared frequently in Kwantlen Polytechnic University's literary magazine, Pulp, and in the literary magazine,

Event

.

Bebakhshid

is her debut poetry collection, which explores Middle Eastern identity, immigration, familial relationships, and the romance of everyday life.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, Bebakhshid is my first book! I think it sobered me in relation to what it means to have a book published and be seen as an "official" writer. I guess I would say it's been humbling, anti-climatic, and surreal? Big words!

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Without sounding pretentious, I think poetry is in my blood. I'm Iranian, and my father was born and raised in the city of Shiraz, known as the "city of poets." My father recited and read many Persian poems to me as a child, so it definitely wasn't a form I was unfamiliar with. But overall, poetry came to me secondary in the trajectory of my life. I initially thought myself a fiction writer, and had been slowly working up to full length novels by writing tons of short stories in my highschool years. During my time there, a teacher had told me that poetry wasn't my strong suit, and to stick to fiction instead - as a very serious, sensitive, and insecure kid, I took that sentiment to heart and didn't doubt it for a second. It wasn't until my time in university that I felt permission to experiment and explore where my gut told me to go. That's when I got serious about poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

As of late, it's taken me a while to start projects. I'm learning to balance my non-writing world with my writing world, and hoping to be able to merge the two. As a result, I start and stop projects numerous times.

When the spark appears, the writing comes to me quickly, like I'm trying to catch what my brain is showing me before it's too late! But I edit poems a few time. I have a lot of scribbles, repeated lines, and synonyms written on the pages of my notebooks.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

It usually begins with an image that comes up in my mind and leaves an impression on me. Sometimes it begins with a feeling I have and I can't place, but I can imagine it or think of words or sentences associated with that feeling.

As a younger writer, I believe I wrote pieces without any kind of cohesiveness or project in mind. Now, I think it helps me with focus and discipline to have some kind of plan in mind. But of course, the heart writes what it wants to write!

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings have no influence or part in my creative process.

For the longest time, I disliked doing readings a lot. I had this idea that my work was only meant to be read internally, privately, amongst one's loved ones, or maybe in front of an audience...but not by me! Sometimes I still feel that way. My writing makes me feel vulnerable but honest, and to perform it (which is how I feel when I do readings) feels the opposite of that. I also fear being misinterpreted, or seen differently than how I or my loved ones see me. But I can't control that, and does it really matter? Once the words are out, they're not just mine anymore. On a more positive note, I do enjoy networking among fellow writers - it's always lovely to feel less alone and among people who also love what you love. Talking to people who resonated with my readings is also such a lovely, sincere experience. I cherish that. I've also had such amazing opportunities to share the stage with talented and experienced writers, such as yourself, rob. That is truly the highlight for me! I've been able to read with people I read in my undergraduate classes!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In relation to Bebakhshid, I think a concern I explored was, "will I ever understand?"

Some of the questions I had during the process of writing the poems that ended up in the book were in relation to understanding my parents, their varied past, and my cultural and religious roots. Who are these people who raised me aside from being the people who raised me? What was their experience in and out of Iran during a time of immense political tension? What was their experience being refugees? What are they going through? Who am I in relation to my parents? Who am I in relation to my culture? I also had a lot of questions about familial relationships, as that has always been an area of concern and fascination with me. What does it take to be a family? What kind of bonds occur? Will my family ever be happy? Will I ever understand what it means to have a family bond? Etc.

Currently, I don't know. Sometimes I feel like the book was published so I could move on with my life. I still grapple with these questions and topics, but to go back to that book and fully explore it again feels like I'd be moving backwards in my writing and personal life. Although it is my first and something I hold dear, I also feel a bit combative towards my book now. I resent having the writer-of-colour label and tokenism that comes with it. I'm currently tired of exclusively focusing and talking about my ethnic and cultural identity. Books take a few years to publish, and so it's been around 4-5 years since the last poem that was written in Bebakhshid. I feel and am different now.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don't know what the role of a writer should be. I also don't think I have much skin in the game to speak to that. But I see the role of a writer being one who can document, interpret, and convey information through many forms. To share things, whatever they may be. To inspire someone else to write, maybe. I don't know. Don't take my answer seriously.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. It was a new experience for me to work with an editor. I value feedback and constructive criticism. Although I feel vulnerable writing, I am not precious with my work in relation to editing it. I would say it's essential because it gets you out of your own head and in the present moment.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To be vulnerable is to be brave!

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I find poetry my comfort and much easier now than it was when I was in high school. I haven't written much fiction as a result - it's a little daunting!

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Currently, I am all over the place and don't have a routine. But usually, when I'm more gathered, I try to write early in the morning by my window. Otherwise, I'll write when it comes to me - that can often be in a movie theatre, the park, a coffee shop that feels just right, or out in nature.

Lately, a typical day begins with taking my dog, Honey, out for a long walk. This is followed by some stretching, a cup of tea, and maybe a bit of reading if I have enough time.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I find reading doesn't usually encourage me to write. I don't often get inspiration from other books or authors. I usually get inspiration from the visual arts, or being present. Films, paintings, and performance art keep me curious. I also love learning about almost everything. Fixating on subjects, people, events, etc gets my wheels turning. People watching, fully engaging with the everyday (much which is mundane) has also provided me some mental clarity to be able to write.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Mowed grass.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes! Movies. I love movies. I love going to the movies, talking about movies, reading about movies, dreaming about movies, blah blah blah. Good movies do the same thing a good poem does for me. It leaves me feeling things I don't know how to convey, and makes me want to capture them. It leaves such an impression on my outlook on life and my understanding of other human beings. It makes me feel human! I love movies. Did I mention I love movies?

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I've enjoyed Ottessa Moshfegh's work. I like the ugliness of it. She writes well and she knows it - her confidence with herself is something I hope I can have a little of.

Shel Silverstein has marvelous poetry collections that are cleverly written for children and adults to enjoy. I find them amusing. The Giving Tree is a heartbreaker.

Joyce Carol Oates' short story, "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been" has left a haunting impact on my worldview.

Jon Krakauer writes true stories so well. He balances fact and emotional vulnerability perfectly, to me. I enjoy his book Into the Wild , and re-read it every so often.

The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien has taught me a lot about the power of storytelling and the approach to take when doing so.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Have my own form of family.

Act - specifically die a horrific death in a major horror film.

Work with animals on a farm.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Since I'm not a full time writer, I am currently working as a Librarian. I'd probably be a homemaker if the stars aligned. Otherwise, maybe something in the film industry. A director if I'm feeling brave.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing has always come easy to me. I loved to read, and gained an advanced vocabulary for my age. I was also a quiet, shy child who often internalized a lot of my feelings. I spent a lot of time alone in my room, so I kept myself company with myself. I had many diaries and notebooks that I filled with all the things I didn't feel I could say aloud, and stories I hoped to experience. Writing had and has been my voice in the world.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

For a book, probably The Door by Magda Szabó.

For a film, The Sound of Metal

20 - What are you currently working on?

A Children's book of poetry. A collection of poems in response to films. Being kinder to myself.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

December 2, 2023

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part two : Ellen Chang-Richardson + Beth Follett,

[see the first part of these notes here]

[see the first part of these notes here]Ottawa ON: The latest from Ottawa-based poet Ellen Chang-Richardson, following a handful of five prior chapbooks authored orco-authored, including their debut, Unlucky Fours (Anstruther Press,2020) [see my review of such here] and the collaborative holy disorder of being (Gap Riot Press, 2022) [see my review of such here] is concussion, baby (Ottawa ON: Apt. 9 Press, 2023). concussion, baby is a small,sketched assemblage of poems that respond directly to the author’s concussionand aftermath, following a trajectory of poets responding to health crises,whether through works by Pearl Pirie, Elee Kraljii Gardiner’s Trauma Head(Anvil Press, 2018) [see my review of such here], Brian Teare’s The EmptyForm Goes All the Way to Heaven (Ahsahta Press, 2015; Nightboat Books,2022) [see my review of the first edition here] or Christine McNair’sforthcoming non-fiction Toxemia (Book*hug, 2024). These poems are set asmoments, narrative pinpoints and jumbles, as though all the mind could hold atthe time, striking against illness and rippling alongside recovery. “I text mylover, / mumble-jumbles / the same day I / find a house / mouse dead,” theopening poem, “sweet nothings” reads, “at the bottom / of my recycling bin.” Anddid you hear that Chang-Richardson’s full-length debut is out come spring with Wolsak and Wynn?

beauty

[in] the meteor of aperson with too much red in their system

[in] the safety of theshape of someone who sleeps while you are awake

[in] the motes of acarpet old & dusty & worn

[in] the striations ofstarburst that burns

[in] the cornea as itshrinks.

Ottawa ON/St. John’s NL: The latest from St. John’s, Newfoundland writer Beth Follett is Learning to Crawl (and other poems)(Ottawa ON: Apt. 9 Press, 2023), her second chapbook with Cameron Anstee’s Apt.9 Press, after A Thinking Woman Sleeps With Monsters (2014) [see my review of such here]. It would appear that Follett, amid novel publication (I wouldhighly recommend her second novel, Instructor: A Novel, published byBreakwater Books in 2021; I reviewed it here), she has quietly releasedchapbooks every so often, with another, Bone Hinged (Toronto ON:espresso, 2010) [see my review of such here], released a few years prior tolanding with Apt. 9; might a full-length poetry debut for Follett be on thehorizon at some point? Honestly, there is something quite compelling aboutthese seemingly stand-alone missives quietly put out into the world, and Learningto Crawl (and other poems) is a title that might not have begun as acollection on and around grief, but one that evolved into such, following the death of her partner, Stan Dragland, in 2022. The opening poem, “BETWEEN CUTKNIFE & SWEETGRASS,” sets the tone for the collection in both astraightforward and devastating manner, offering this as the first of the poem’sthree stanzas: “I am a cold, cold teacher. / I don’t even. I don’t have a. /Husband. No he died, you can / tell me till you’re blue in the face. / But afact. It isn’t even. I don’t even. / I don’t have a snack. I’m here, / a coldinstructor on a widow odyssey.” Or, as she writes as part of the poem “I ACHESOMETIMES, FROM LOVING MY DAYS SO MUCH, FROM LOVING”: “I love asking via FannyHowe what are you looking for when you erase a word / because I took out adecorative word and replaced it plainspokenly.” Set on a foundation of profoundloss, Follett’s narrative lyric meditations offer a pause within a moment that accumulateinto a slow lean, one that might evolve into the mid-step before into whatmight follow.

BEFORE A WALK IN WINTER

The sun a pale dot in anerstwhile veil. Never trust it. Have a cookie.

Don’t put on boots whilethe fog horn blows. Know exactly

where and when to putyour foot down. Propulsion. Here’s the dust,

the grime of electricity.Teaser the dove. Soon oh soon genius will rise,

the chartered grant of sleep.You might miss it if you leave the house.

Should nails be filed,those of toes that moon

for the darning of socks?Was that the post? Maybe drink some water,

avoid deep thrombosis proceedingfrom dehydration. Potatoes are sprouting,

ice cream is lost tofreezer burn. Fully naked the doorbell

rings. Fully clad forthis winter walk, nature calls.

Leave oh leave too soonforever gone.

December 1, 2023

Jordan Davis, Yeah, No

The Apricot

The red and white foldedwith gray

shadows of the Americanflat

reflected and beating I theconcavity

of the silver orange bowlthree seeds

ridged with spikes ofhere red here

orange dried fruit thespikes like

the edge the edge likethe shell

of a crab the damp grayday

left at the isthmus theapricot

Thethird full-length poetry collection by Brooklyn poet, editor and publisher JordanDavis, following

Million Poems Journal

(Faux Press, 2005) and

Shell Game

(Edge Books, 2018), is

Yeah, No

(Cheshire MA: MadHat Press, 2023). WhereasI had seen two chapbooks by Davis prior to this—

NOISE

, which appearedlast year through my own above/ground press (full disclosure) and

Hidden Poems

(If A Leaf Falls Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]—this is thefirst full-length collection of his I’ve seen (although the poems of NOISE doexist within). From the title alone, one can see how Davis revels in thecollision of words and meanings, allowing a combination of collision and pivotto form new shapes, utilizing thoughts and phrases that occasionally even seem torun each other through. “Believing me, believe me, be believing me.” he writes,to open the poem “Loud Singing,” “I found the envelope empty. / I did not know Iwas not supposed to open the envelope.” Long associated with the flarf poets,as his author biography attests, his poems are sensory, rhythmic and gymnastic,simultaneously flippant and dead serious—showcasing elements of the “seriousplay” that bpNichol often referenced—offering lyrics neither surreal or straightforwardbut clearly made out of words. “A pirate in a repeat environment / plays tag inthe ironing.” the poem “Eleven Forgiven” begins, “Entangle the raiments. / Peeved,tap clogs, / the livery of pillory talk / evangel living as foreign / as thedriver of the Rangers’ van.” Davis’ craft is clear through the speed and theease through which his lines roll; composed as moments, but fractured,fragmented; offered to keep the mind slightly off-balance, guessing. Not merelyblending but smashing together political commentary with pop culture, Davis’ poemsaim, one might say, not for the “a-ha!” conclusion of traditional lyric, butone of moments altered and alternate, working to see what else might begathered through how phrases are formed. “Do the easy things first, get somemomentum.” he writes, to open the poem “Think Tank Girl,” “It’s a managementprinciple. Also? / You might make sure you’re not poisoning apples / in the sprawl,claiming responsibility / for turning the hillside from smooth dark green / toa grid of pale cubes, an avocado / you’d invent to feed your young. / In a freemarket they call sneak attacks troubleshooting.”

Thethird full-length poetry collection by Brooklyn poet, editor and publisher JordanDavis, following

Million Poems Journal

(Faux Press, 2005) and

Shell Game

(Edge Books, 2018), is

Yeah, No

(Cheshire MA: MadHat Press, 2023). WhereasI had seen two chapbooks by Davis prior to this—

NOISE

, which appearedlast year through my own above/ground press (full disclosure) and

Hidden Poems

(If A Leaf Falls Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]—this is thefirst full-length collection of his I’ve seen (although the poems of NOISE doexist within). From the title alone, one can see how Davis revels in thecollision of words and meanings, allowing a combination of collision and pivotto form new shapes, utilizing thoughts and phrases that occasionally even seem torun each other through. “Believing me, believe me, be believing me.” he writes,to open the poem “Loud Singing,” “I found the envelope empty. / I did not know Iwas not supposed to open the envelope.” Long associated with the flarf poets,as his author biography attests, his poems are sensory, rhythmic and gymnastic,simultaneously flippant and dead serious—showcasing elements of the “seriousplay” that bpNichol often referenced—offering lyrics neither surreal or straightforwardbut clearly made out of words. “A pirate in a repeat environment / plays tag inthe ironing.” the poem “Eleven Forgiven” begins, “Entangle the raiments. / Peeved,tap clogs, / the livery of pillory talk / evangel living as foreign / as thedriver of the Rangers’ van.” Davis’ craft is clear through the speed and theease through which his lines roll; composed as moments, but fractured,fragmented; offered to keep the mind slightly off-balance, guessing. Not merelyblending but smashing together political commentary with pop culture, Davis’ poemsaim, one might say, not for the “a-ha!” conclusion of traditional lyric, butone of moments altered and alternate, working to see what else might begathered through how phrases are formed. “Do the easy things first, get somemomentum.” he writes, to open the poem “Think Tank Girl,” “It’s a managementprinciple. Also? / You might make sure you’re not poisoning apples / in the sprawl,claiming responsibility / for turning the hillside from smooth dark green / toa grid of pale cubes, an avocado / you’d invent to feed your young. / In a freemarket they call sneak attacks troubleshooting.”