Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 78

September 11, 2023

Laynie Browne, Letters Inscribed in Snow, Practice Has No Sequel and Intaglio Daughters

My group review of Laynie Browne's new poetry trio of collections,

Letters Inscribed in Snow

(Tinderbox Editions, 2023),

Practice Has No Sequel

(Pamenar Press, 2023) and

Intaglio Daughters

(Ornithopter Press, 2023), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her

Translation of the lilies back into lists

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2022) here, my review of

You Envelop Me

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2017) here and my review of

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues, 2012), edited by Browne, Caroline Bergvall, Teresa Carmody and Vanessa Place, here.

My group review of Laynie Browne's new poetry trio of collections,

Letters Inscribed in Snow

(Tinderbox Editions, 2023),

Practice Has No Sequel

(Pamenar Press, 2023) and

Intaglio Daughters

(Ornithopter Press, 2023), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her

Translation of the lilies back into lists

(Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2022) here, my review of

You Envelop Me

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2017) here and my review of

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

(Los Angeles CA: Les Figues, 2012), edited by Browne, Caroline Bergvall, Teresa Carmody and Vanessa Place, here.September 10, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Buffy Cram

Buffy Cram isa writer of fiction and non-fiction, an entrepreneur and a farmer. Reviewingher 2012 book of stories, Radio Belly (Douglas & McIntyre), the Globeand Mail pronounced her “a whip-smart storyteller who aims to shake up ourreading expectations in ways that delight.” She has been a fiction finalist forthe Western Magazine Awards, has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and haswon a National Magazine Award. Her newest book is the novel Once Upon an Effing Time (Douglas & McIntyre). She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UBCand lives on Salt Spring Island, BC.

1- How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Themost significant change after my first book, Radio Belly, was that I gota job teaching creative writing at a small college. This forced me toarticulate what I knew about reading and writing and to unpack a lot of thingsI only had an intuitive sense of up until then. I think these years as ateacher and all the careful consideration of the elements of writing helped me getto the end of the novel.

2- How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Iactually started with journalism, then moved to creative non-fiction, theneventually found my way to fiction. I had to sneak up on fiction slowly becauseI revered it so much. It took a bit ofinternal work to give myself permission to make up stories. Then I had to disabusemyself of the notion that creative works arrive fully formed. But once Ilearned that creative works, like most things in life, are built slowly, methodicallyand even messily, from the ground up, fiction became a comfortable home.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Firstdrafts of short stories tend to come quickly for me. I always feel like I’mchasing after an idea, trying to get it by the tail. I often write stories inthe wrong order though, with the climax up front or the end at the beginning. Forme, 90% of the work of writing is in rearranging and “fixing” my first draft.With the novel the process is much the same except I’m working through severalpieces of the story at once and the hard work is in trying to stitch thesepieces together.

4- Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

The most successful stories I’ve written, whethershort or long, usually begin with an idea that is triggered by some real-lifeevent—an anecdote I’ve heard, or something I’ve read in the news. Once I knowwhat issue I want to write about, I do a lot of freewriting to search aroundfor the characters and scenes that will give me a fresh angle on that issue. Ialways start small, with the simple intention of expressing an idea. I try notto think about that idea’s final form (whether short story or book) until muchlater in the writing process.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I get really inspired by attending publicreadings, but I can’t say I enjoy giving them. People often mistake me for anextrovert, but I’m not. Being the centre of attention is always a somewhatpainful experience for me. I can get through giving a reading and it is almostalways a positive experience, but I usually need a stiff drink and/or a napafter.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Thereare many theoretical concerns that drive my writing. I’m very concerned about thestate of our world: the changing climate, homelessness, corporate greed,individual greed, systemic inequality, the failures of capitalism, ourdwindling relationship with nature and many other things. I suppose part of thedeal I made with myself when I became a fiction writer—part of giving myselfpermission to make up stories—was a promise to somehow address these issues inmy writing.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ispent my formative years as a writer living in South America and I was very drawnto the tradition of magic realism. The idea that applying imagination and evenmagic to political/societal problems in order to affect change in the realworld fascinates and inspires me. It is part of my personal contract withwriting to try and play at the edges of this tradition, but other writers mayhave a different contract.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Inmy opinion there is nothing better than working with an editor who understandsthe intent and tone of your work and can guide you towards clarifying it. I hadthis experience with my novel and it was wonderful. I do my best to offer thisexperience to others.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

The best advice usually comes from my mom. One thingshe’s taught me recently is to be suspicious of the feeling of panicked urgencythat sometimes comes up in life because often that means the ego is involved. Soinstead of immediate knee-jerk reactions, I’m learning about the virtues of inaction.I used to think inaction was a form of laziness, but now I understand it is aform of wisdom.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories tonon-fiction to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

In my 20s I went through a phase where I moved to adifferent country and/or city every year. I liked the challenge of arriving ina new place where I didn’t know my way around and didn’t speak the language.Switching genres is a little like that. I suppose I seek out these kinds of experiences—oneswhere I don’t have a map and am prompted towards dramatic growth.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I always write in the morning when my brain isquietest. When I’m working on a project I try to engage with it every day forat least an hour a day, otherwise I lose the connection to the world I’m tryingto build. This has been my routine for over a decade, but now that I’m done thenovel I’m thinking about exploring other types of routines.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Whileworking on my novel I often got stuck, often for months at a time and it wasquite painful because I just kept working and didn’t allow myself a break. Inow know that a better approach would be to step away from that project and dosomething else for a little while. Now when I get stuck in writing, I work onsculpture or take a long walk or play ping pong. I think this is a kinderapproach to the work.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Allthings woody: woodsmoke, sawdust, the smell of fresh-cut cedar.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Music has always been a huge influence on my writing.When I get mired down by the technical aspects of writing, music puts me back in touch with the feeling part ofwhat I’m trying to accomplish. For example, during the writing of my novel Iwas learning to play the banjo. I kept being drawn, melody-wise,to old murder ballads, many of which are told from the point of view of aperson who is about to hang from the gallows and is remembering where theirlife went wrong. These songs, with their intense sense of urgency and regret,ended up directly influencing the structure of my novel, which is told inalternating “before-the-crime” and “after-the-crime” sections.

15– What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Foreach phase of my life I have always had a few talisman books that I return toagain and again for wisdom or inspiration. There are two books that served astalismans for me during the writing of this novel. The first was Lynda Barry’sillustrated novel, Cruddy. When I worried my writing was becoming toodark, I turned to this book for permission to go further into the darkness andto trust that there could still be glints of light and humour. And the otherbook was Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. This book helpedme connect to the frenetic energy of the late 60s and taught me how to manage alarge cast of people.

16– What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?

I would like to go on a long bicycle trip through theflatter countries of Europe. Or maybe it could even be a long walk. I guess atthis point in my life I’m drawn to the idea of long, self-propelled journeyswithout too many hills.

17– If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

I would have liked to have become an acupuncturist. Overthe years TCM has become essential to managing my own health. I have greatrespect for it and I’m fascinated by the systems behind it. Like fictionwriting, it seems like the type of profession that lends itself to lifelonglearning.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

WhenI started writing fiction regularly, in my early 20s, I noticed that when I waswriting, I disappeared for a little while. There was no me, just these words andvoices that seemed to be coming through me. I became hooked on that feeling andI think it’s still the main reason why I write. There’s nothing better thangetting away from myself once in a while!

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

WhileI was writing my novel, I found I couldn’t read contemporary fiction because Iwas afraid it would influence my work too much. So I returned to the classics.The last great book I read was Lolita. I had always purposely avoidedthis book because I thought the subject matter would bother me. But when I readit, I realized that is exactly the point. The book purposely creates conflictwithin the reader. The subject matter is deeply troubling, but it is writtenwith such panache, with sentences and paragraphs that are worthy of beingframed and put on the wall. This creates an interesting push/pull within thereader.

20- What are you currently working on?

At the moment I’msneaking up on a second novel, but I mustn’t speak of it or I might spook it.

September 9, 2023

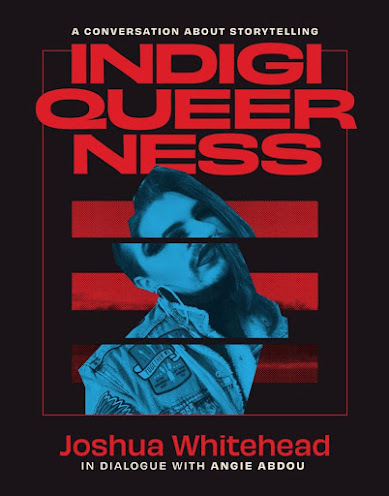

INDIGIQUEERNESS: Joshua Whitehead In Dialogue with Angie Abdou

Looking back now, as thirty-three-year-old Josh, I realizeI saw myself in those books.

I didn’t know at the time, but I was connecting,having fibres of paper also attaching to tendrils of Joshua’s identity.

I’ve seen myself in books without having the language orterminology to explain why I’m so attached to these queer figures or cyborgs ormutants. Now, looking back, that work was so formative to me becoming a Two-Spiritperson and writer. I got to escape into a wormhole and be devoured and devoidof all things around me, and in that space of nothingness, there was all things– which made the experience so rich and formative.

I’vebeen appreciating the structure and content of

INDIGIQUEERNESS: A Conversation About Storytelling: Joshua Whitehead In Dialogue with Angie Abdou

(AthabascaAB: Athabasca University Press, 2023), an extended conversation British Columbia-basedfiction writer (and Athabasca University professor) Angie Abdou and writerJoshua Whitehead [see my 2018 Ploughsares interview with him here] around blendingliterary and genre writing, queer and Indigenous content, working to emerge asa writer and performer, and of aiming work for a young adult audience. I’mcurious as to what prompted this particular conversation, and how it fell intoa book through the press, but I’m appreciating the insight into Whitehead’s workand thinking, the way an approach to writing was formed across genre. Part ofme wishes there could have been at least some spark of introduction to this collection,but there is something enticing, as well, about simply launching immediatelyin. Throughout his work, as well as through this conversation, I appreciate howWhitehead is open about his influences, blending genres such as YA novels,science fiction, punk and anime, and citing Richard Wagamese, Ursula K. Le Guinand Billy-Ray Belcourt; open about the writing in which his writing exists within a far larger conversation.

I’vebeen appreciating the structure and content of

INDIGIQUEERNESS: A Conversation About Storytelling: Joshua Whitehead In Dialogue with Angie Abdou

(AthabascaAB: Athabasca University Press, 2023), an extended conversation British Columbia-basedfiction writer (and Athabasca University professor) Angie Abdou and writerJoshua Whitehead [see my 2018 Ploughsares interview with him here] around blendingliterary and genre writing, queer and Indigenous content, working to emerge asa writer and performer, and of aiming work for a young adult audience. I’mcurious as to what prompted this particular conversation, and how it fell intoa book through the press, but I’m appreciating the insight into Whitehead’s workand thinking, the way an approach to writing was formed across genre. Part ofme wishes there could have been at least some spark of introduction to this collection,but there is something enticing, as well, about simply launching immediatelyin. Throughout his work, as well as through this conversation, I appreciate howWhitehead is open about his influences, blending genres such as YA novels,science fiction, punk and anime, and citing Richard Wagamese, Ursula K. Le Guinand Billy-Ray Belcourt; open about the writing in which his writing exists within a far larger conversation. I’malso appreciating how the conversation is broken up through design and asidesof accompanying visuals, including quoted texts, old poems, photographs and archivalmaterials, providing the body of the book as a performative space, one that isall-encompassing, well beyond the scope of the immediate conversation. “Poetryis at the base of everything I do.” Whitehead responds, mid-way through theconversation. There are some really interesting elements discussed within,also, of how pieces that didn’t fit into his full-length poetry debut, full-metalindigiqueer (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2017) [see my review of such here],evolved into his award-winning debut novel, Johnny Appleseed (VancouverBC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), and how he engages elements of genre writing, fullyaware of a conversation of how literature often looks down on genre.

I remember walking down Ellice Avenue, another streetjust off the University of Winnipeg campus, adjacent to that creative hub. I wastaking notes on the graffiti and the trash and the mundane things that nobodysees. From that, I wrote a poem, and it became the first poem I ever published,in Prairie Fire. I remember getting my cheque for $100 payment for thatpublication, and it’s been a snowball effect since then. I was working longhours and writing poems for pennies and performing in the streets of Winnipegfor free…and now, being the emerging writer that I am, and sitting on the stageat Canada Reads blows my mind still – that I’ve achieved that level of opticsin a short span of time.

But I never write in a vacuum. Everything I’ve craftedand made has been a whirlwind of community and folks and friends and lovers andfamily. I kind of write as an animated avatar. A lot of my material comes fromlistening fiercely to those around me and witnessing that which is discarded ornot seen.

September 8, 2023

Tom Cull, Kill Your Starlings

HOME KEPT COMING

how a cloud can be a fist

a visible hand

we only saw blue sky

and piled wreckage

the turtle carries

the word home onits back

what did that word looklike?

burnished, tectonic

the sound off crack

and scoop and slurp

Thesecond full-length collection from London, Ontario poet (and, from 2016-2018,that city’s poet laureate) Tom Cull, following

Bad Animals

(Toronto ON:Insomniac Press, 2018), is

Kill Your Starlings

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2023), a collection of poems that appear, carefully and delicately, asthough carved out of stone or ice. Across this book-length suite on family andplace, Cull offers an assemblage of descriptive, first-person lyrics, settingblocks down as if to build, writing on cars, family, Ikea, masculinity,toxicity and landscape. Listen to how he describes heading west by train out ofOttawa (specifically, Fallowfield Station): “Outside, land is drawn andquartered. / Wild turkeys step through / split-rail fences; a lone coyotepauses / in a pasture, head thrown / back across its body watching us pass.” Cull’swisdom, as well as his humour, emerges quietly, to rest amid rumination,offering one step and then another, further, considered step: not one word orline out of place. As the back cover offers, this is a book about family andplace, although there is a way he writes about masculinity is worth mentioning:his articulations are different, although equally powerful, than, say, DaleSmith’s Flying Red Horse (Talonbooks, 2021) [see my review of such here],offering a sequence of poems, for example, on the male gestures offered throughcar commercials. “Set it free.” he writes, in the poem “Subaru Wilderness,”the fourth and final poem in the sequence “AUTO EROTICA,” “See the Subaru inits natural habitat; / a hundred thousand mutations, / bionic selectionstalking slag ridges— // terrarium interiors—synthetic protein / seats, hotmist, pitcher plants, / neon salamander toes suction cupped / to the windows.” Cull’sthreads are subtle, offering a book heartfelt and deep, writing of a father helearned from by example, benefitting from the man’s quiet dignity. “Years aftermy dad died,” he writes, as part of the wonderfully graceful “AUTOPSY REPORT,” “Imoved home temporarily to help get the farm ready for sale. I hired plumbers, roofers,contractors to do the work. Over the course of that year, I met several men,who’d had my dad as their teacher. They all praised his patience, his care, andhis demand for discipline and hard work.” The poem ends:

Thesecond full-length collection from London, Ontario poet (and, from 2016-2018,that city’s poet laureate) Tom Cull, following

Bad Animals

(Toronto ON:Insomniac Press, 2018), is

Kill Your Starlings

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2023), a collection of poems that appear, carefully and delicately, asthough carved out of stone or ice. Across this book-length suite on family andplace, Cull offers an assemblage of descriptive, first-person lyrics, settingblocks down as if to build, writing on cars, family, Ikea, masculinity,toxicity and landscape. Listen to how he describes heading west by train out ofOttawa (specifically, Fallowfield Station): “Outside, land is drawn andquartered. / Wild turkeys step through / split-rail fences; a lone coyotepauses / in a pasture, head thrown / back across its body watching us pass.” Cull’swisdom, as well as his humour, emerges quietly, to rest amid rumination,offering one step and then another, further, considered step: not one word orline out of place. As the back cover offers, this is a book about family andplace, although there is a way he writes about masculinity is worth mentioning:his articulations are different, although equally powerful, than, say, DaleSmith’s Flying Red Horse (Talonbooks, 2021) [see my review of such here],offering a sequence of poems, for example, on the male gestures offered throughcar commercials. “Set it free.” he writes, in the poem “Subaru Wilderness,”the fourth and final poem in the sequence “AUTO EROTICA,” “See the Subaru inits natural habitat; / a hundred thousand mutations, / bionic selectionstalking slag ridges— // terrarium interiors—synthetic protein / seats, hotmist, pitcher plants, / neon salamander toes suction cupped / to the windows.” Cull’sthreads are subtle, offering a book heartfelt and deep, writing of a father helearned from by example, benefitting from the man’s quiet dignity. “Years aftermy dad died,” he writes, as part of the wonderfully graceful “AUTOPSY REPORT,” “Imoved home temporarily to help get the farm ready for sale. I hired plumbers, roofers,contractors to do the work. Over the course of that year, I met several men,who’d had my dad as their teacher. They all praised his patience, his care, andhis demand for discipline and hard work.” The poem ends:A few years ago, my momwrote a poem about my dad. The poem

ends with details fromhis autopsy report:

BUILD: moderately obese

BRAIN: unremarkable

HEART: massively enlarged

September 7, 2023

newly posted at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics : folio : (further) short takes on the prose poem

newly posted at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics : folio : (further) short takes on the prose poem

newly posted at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics : folio : (further) short takes on the prose poem

Gary Barwin ; Jay Besemer ; Heather Cadsby ; Maxine Chernoff ; kevin mcpherson eckhoff ; Anna Gurton-Wachter ; Jason Heroux ; Shane Kowalski ; Aaron Kreuter ; Alex Leslie ; Nate Logan ; IAN MARTIN ; Angelo Mao ; Sarah Moses ; Lori Anderson Moseman ; Gillian Parrish and Gene Pfeiffer ; Devon Rae ; Eléna Rivera ; Gillian Sze ; Vik Shirley ; Evan Williams ; Kim Fahner, Margo LaPierre, and Jérôme Melançon, Extroverted review: the book of smaller, by rob mclennan ; prior folio: twenty-eight short takes on the prose poem (March 2022) ; lovingly edited and compiled by rob mclennan,

September 6, 2023

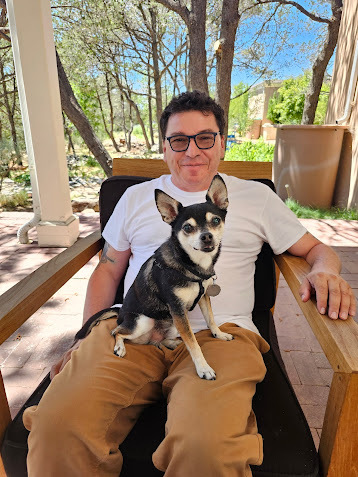

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tommy Archuleta

Tommy Archuleta is a native northern New Mexican. Heworks as a mental health therapist for the New Mexico Corrections Department.Most recently his work has appeared in the New England Review, LaurelReview, Lily Poetry Review, The Cortland Review, Guesthouse,and the Poem-a-Day series sponsored by the Academy of American Poets. Susto,his full-length debut collection of poems, published by the Center for LiteraryPublishing, is a 2023 Mountain/West Poetry Series title. He is also the authorof the chapbook, Fieldnotes (Lily Poetry Review & Books, 2023). Helives and writes on the Cochiti Reservation.

1 - How did yourfirst book change your life?

One’s first kiss.One’s first fish. One’s first day of school. Whatever the right of passage, thebody absorbs, then records them all, etches them onto stone tablets, stoneculled from a quarries nowhere near Ohio.

Why for—who knows?

Perhaps they’regiven to the mind for later playback over those final few breaths.

Perhaps they’resold outright to the unconscious who then trades them to the soul for Mozart’sunscored cello concertos.

Perhaps nothingmuch changes beyond our noticing how much the road we’re on narrows as we go incontrast to the ever-widening, ever-expanding horizon.

2 - How did youcome to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Not far from wherethey found me the first time I got lost, lies a fire road that was cut longbefore Eustacio Ortiz, the first ore miner, “courted” Delilah Rose. And along acertain, short section of that road lives a cake of air thrice colder than theair before or after it. Who can be blamed for believing one comes to thisparticular brand of cold, but no—with enough time and pressure, one arrives atthe realization that said cold was both never and always there, and anywhereelse land, air, and water might care to meet.

3 - How long doesit take to start any particular writing project?

151.7milliseconds.

Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process?

37 years ago, at abus stop on the corner of 42nd Avenue and Hollis Avenue, Oakland CA,an old old man in black shoes and white socks, said the following words:

“When you get to acertain stage, you’ll regret more what could’ve said rather than what ended upsaying.”

Two days ago, and37 years later, I heard the above words.

Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

Orchid:

seed germination

root growth

leafproduction

flower spike growth

bloom stage

dormancy

4 - Where does apoem usually begin for you?

As one enters theCochiti Reservation on foot, from the West, the earth there is redder than red.Nowhere else for miles and miles and every direction is this the case.

Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

Yes, and, also—Itouched a frog once.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process?

“Knowing one’s owndarkness is the best method for dealing with the darknesses of otherpeople.”

--C.G. Jung

Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’m the sort ofwriter who enjoys being read to.

6 - Do you haveany theoretical concerns behind your writing?

I’m concernedabout birds in midflight freefalling to the cold, hard ground.

Alternative factsvastly concern me.

I’m concerned theSandhill Crane won’t know where to fly when soon autumn feels as warm, orwarmer, than summer.

I’m concerned I’llbe at work when my father’s last few breaths arrive, finally.

7 – What do yousee the current role of the writer being in larger culture?

If we’re talkingabout a human writer, writing on the planet Earth, then I can’t think of abetter role than writer, nor can I think of a better larger culture than Earth.

Do they even haveone?

As far as I know,all writers have two of everything.

What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

I think the writershould avoid processed sugar and illicit drug trafficking.

8 - Do you findthe process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

If a higher powerdoth exist, then a lower one, too, must exist.

9 – What is thebest piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Avoid, at allcosts, staring directly at the sun for any length of time.

10 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?

As far as I know,all writers have two of everything.

How does a typicalday (for you) begin?

Through the ringing, now in both ears, and the wavering

hum of lower earth:

the caws of dawnlit crows lifting off.

We’re not built to sit still for too long, either.

Nor are we born broken.

And barely do we come equipped to survive

whatever might fly out of our own godgiven mouths.

It’s going to hail soon. You can feel it.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

Sorry—that’sclassified information.

12 – Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Human and/or goatblood.

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I once touch afrog that David W. McFadden once touched.

Translation: Ionce touched David W. McFadden’s frog.

14 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

I work as atherapist in a prison. Some of my clients are serving life sentences for havingmurdered another human being, to include several human beings. Clients of thissort often send me poems because they heard that I write poems. Few things inthis life move me more than reading the poems of men who experience theoutdoors belly-chained while in five boot by 12 foot iron mesh cage for onehour a day.

15 - What wouldyou like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like toapologize to at least two frogs.

16 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?

I would kill to bea Vanda Orchid.

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

Early childhoodtrauma.

18 - What was thelast great book you read?

As for Dreams by Saskia Hamilton.

What was the lastgreat film?

19 – What are youcurrently working on?

A pocket dreamdictionary.

September 5, 2023

new from above/ground press: Wilkins, drystek, Magliocca, Baker + Wilkins (again,

; Poetic Constructions: Poems written for the Enriched Bread Artists’ 2020 Open Studio, by Grant Wilkins $5 ; missing matrilineal, by nina jane drystek $5 ; Girl gives long-fingered self-portrait, by Sophia Magliocca $5 ; The Baroness and her Ex Read Orgasmic Toast: To Whom It May Concern, by Grant Wilkins $5 ; Groundling: On Apology, by Jennifer Baker $5 ;

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; see the previous batch of backlist here,

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

August 2023

as part of the above/ground press 30th anniversary

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

And did you see my report on the recent above/ground press 30th anniversary reading/launch/party?

Forthcoming chapbooks by Colin Dardis, Sophia Magliocca, Russell Carisse, Micah Ballard, Cary Fagan, Amanda Deutch, Kevin Stebner, Kyla Houbolt, Gary Barwin, Adriana Oniță, Noah Berlatsky, Heather Cadsby, Blunt Research Group, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Zane Koss, Peter Myers, Gil McElroy, Ben Robinson, Miranda Mellis, MLA Chernoff, Terri Witek, Geoffrey Olsen, Pete Smith, Robert van Vliet, Marita Dachsel and Angela Caporaso (among others, most likely). And watch soon for an announcement for 2024 subscriptions!

September 4, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Denise Da Costa

Denise Da Costa

[photo credit: Samuel Engelking] is a Canadian author and visual artist whose debut novel

And the Walls Came Down

, was published in Summer 2023. She studies Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and is an alumna of the Humber School of Writers and the Diaspora Dialogues mentorship program. Her work explores the complications of love and the impact of gender, race and class on identity formation.

Denise Da Costa

[photo credit: Samuel Engelking] is a Canadian author and visual artist whose debut novel

And the Walls Came Down

, was published in Summer 2023. She studies Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and is an alumna of the Humber School of Writers and the Diaspora Dialogues mentorship program. Her work explores the complications of love and the impact of gender, race and class on identity formation. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

And the Walls Came Down is my debut novel and though there have been few, if any, material changes in my life thus far - it feels like I'm finally on the right path with my writing journey.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I naturally gravitated to the narrative format that I enjoyed reading and writing most.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

When I'm fortunate enough for timing and inspiration to occur in unison, writing can be fluid, however, it can happen in ebbs and flows over long periods of time which can impact the subsequent drafts significantly for someone early in their writing practice.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

In most cases, shorter pieces are generally summaries or glimpses into a much larger idea. I tend to set out to write novels but I'm learning how to enjoy the practice of writing shorter works. It's a great way to exhaust myself of old pent up ideas and once those have been documented I can access fresh material.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have never done a public reading ! However, my first such event is soon approaching. I'll let you know how it goes.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I try to pose questions through my work, rather than answer them. Though ideas and interests will change over time, the construction of identity is something I enjoy exploring. What lies at the core of the individual, and how do the constraints of one's culture, place, race, gender and class impact the construction of our individual identities?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I like to think of the writer as one who catalogues the human experience - imaginative and factual. We attempt to extract the observable and unobservable qualities of lives that can be experienced by anyone with access. We create and interpret the story behind the photograph. The words behind the music. The dialogue that frames the film. We share a responsibility (with other artists) who aim to communicate the essence of living.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

My own experience working with external editors has been both an essential and pleasant part of the journey to bringing a project to completion.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

"It's not ready. Hire an editor."

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to essays to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

As a multi-disciplined artist, I find moving from visual art to writing to be as natural as switching between typing up screenplay and writing a short story the next day. One creation inspires the next - a continuation of an evolving story.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I do not have a writing routine - but I'm working on it. A demanding career makes it difficult but working with a writing group keeps me accountable.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read. I read books that make me want to write (often I turn to non-fiction!).

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Burning wood.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Film, Music and Cooking seems to seep through my work quite a bit.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I find it important to read essays on narrative, get lost in a literary magazine, and read genres other than what I'm writing at the time.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

See a film produced from a screenplay I've written.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I work in corporate, focusing on people leadership and technology so writing is the occupation I'd like to move into.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I've been writing as long as I can remember, but wasn't brave enough to commit to it the first time around.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Truth Telling, Michelle Good and Oppenheimer .

20 - What are you currently working on?

A speculative fiction.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 3, 2023

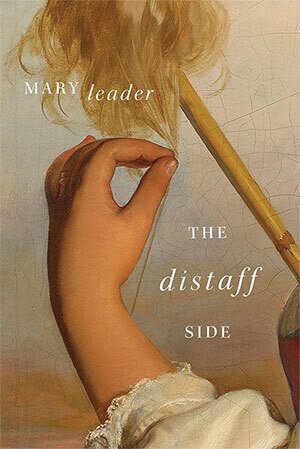

Mary Leader, The Distaff Side

PANEL F

My mother could not sewand neither

could she knit. I thinkshe’d have agreed

with Agatha Christie’sHercule Poirot:

“A woman did not look herbest

knitting: the absorption,the glassy eyes,

the restless busyfingers!” Similarly,

if my mother had evergotten to go

to Sewanee Writers’ Conference(which,

later on, I got to), I thinkshe’d have agreed

with a man’s commentabout how rude it is

when women in theaudience take out

their knitting and get towork on it while

listening to variouslong-winded readings.

Did he never know men tosit and whittle

while talking and,occasionally, spitting?

I’mfascinated by American poet and lawyer Mary Leader’s fifth full-lengthcollection,

The Distaff Side

(Shearsman Books, 2022), a curious blend ofa variety of threads: the needlepoint the women in her family held, dismissedas “women’s work”; her mother’s refusal to learn such a thing to focus onpoetry, and publishing in numerous journals yet never seeing a collection intoprint; and her own engagement with these two distinct skills, articulating themboth as attentive, precise crafts. “My mother couldn’t sew a lick.” she writes,to open the sequence “Toile [I],” offering her mother’s refusal to learn assomething defiant across the length and breadth of women across her family, “Butthat was a boast to her.” As the following poem reads: “1950, 1955, / 1960. Whatgirls and women got up to / with distaffs flax spindles standards / happlesand agoubilles was not called ‘their art.’ Not remotely. Needlework / wasno more ‘creative’ than / doing the dishes, and trust me, / doing the disheswas not marveled at, [.]” That particular poem ends: “And my / mother’s hobby morningafter / morning after morning, every morning, / every morning, was reading andwriting / poetry, smoking all the while.” There’s a defiance that Leader recountsin her narrative around her mother, and one of distinct pride, writing a womanwho engaged with poetry. A few poems further in the sequence: “I have / thetypescript of what, in my judgement, / should have been my mother’s first /published book, Whose Child? I have / here the cover letter she laboredover.” I’m charmed by these skilled, sharp and precise poems on the complexitiesof the craft of poems and needlework both, stitched with careful, patient ease.

I’mfascinated by American poet and lawyer Mary Leader’s fifth full-lengthcollection,

The Distaff Side

(Shearsman Books, 2022), a curious blend ofa variety of threads: the needlepoint the women in her family held, dismissedas “women’s work”; her mother’s refusal to learn such a thing to focus onpoetry, and publishing in numerous journals yet never seeing a collection intoprint; and her own engagement with these two distinct skills, articulating themboth as attentive, precise crafts. “My mother couldn’t sew a lick.” she writes,to open the sequence “Toile [I],” offering her mother’s refusal to learn assomething defiant across the length and breadth of women across her family, “Butthat was a boast to her.” As the following poem reads: “1950, 1955, / 1960. Whatgirls and women got up to / with distaffs flax spindles standards / happlesand agoubilles was not called ‘their art.’ Not remotely. Needlework / wasno more ‘creative’ than / doing the dishes, and trust me, / doing the disheswas not marveled at, [.]” That particular poem ends: “And my / mother’s hobby morningafter / morning after morning, every morning, / every morning, was reading andwriting / poetry, smoking all the while.” There’s a defiance that Leader recountsin her narrative around her mother, and one of distinct pride, writing a womanwho engaged with poetry. A few poems further in the sequence: “I have / thetypescript of what, in my judgement, / should have been my mother’s first /published book, Whose Child? I have / here the cover letter she laboredover.” I’m charmed by these skilled, sharp and precise poems on the complexitiesof the craft of poems and needlework both, stitched with careful, patient ease.

September 2, 2023

Brandon Shimoda, Hydra Medusa

These questions come to mind as I contemplate the intransigent,intractable void that hovers over the ruins of Japanese American incarceration.One element forming the void is the murders of Japanese and Japanese American meninside, outside, and on the perimeters of WWII prisons and concentration camps,murders that exist on and resonate through the continuum of the murder ofpeople of color by state operatives/law enforcement in the United States. The void(shadow) is earth, sky, everywhere in between.

Kanesaburo Oshima was shot and killed by a guard in theprison camp in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura were shotand killed by a guard outside the prison camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico. JamesIto and Katsuji James Kanegawa were shot and killed by military police inManzanar. James Hatsuaki Wakasa was shot and killed by a guard in Topaz. ShoichiJames Okamoto was shot and killed by a guard at the entrance to Tule Lake. Thesemen are the most commonly cited, if they are cited at all. (An eighth man,Ichiro Shimoda, was also murdered, also in Fort Sill, but the circumstances ofhis murder are unclear. Shimoda’s friends suspected that because he witnessedthe murder of Oshima, he was detained by the military police, and died in theircustody.) There has been neither justice for nor legitimate reckoning withthese deaths. The murderers (both individuals and the systems to which they werereporting) reaped the benefit of passing into oblivion. (“THE DESCENDANT”)

LatelyI’ve been going through Brandon Shimoda’s most recent collection,

Hydra Medusa

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2023), a self-described continuationof his collection,

The Desert

(The Song Cave, 2018), a book I have onlyheard tell of. Hydra Medusa is a complex collection composed as a bookof dreams and death, ancestors, parenting and desert stretches through a blendof essays and poems. “Death is what it took for us to be in each other’scompany. But what kind of company was I?” he writes, two-thirds through thebook. He writes of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during and aroundthe Second World War, and of repeated murders and ancestors, and how lives can’thelp but connect to each other. Hydra Medusa is a book on the living andthe endless dead, seeking answers to questions that might be impossible toanswer, or too individual to fully articulate. As he writes, early on, as partof the essay “THE DESCENDANT”: “What is an ancestor? I have been asking thisquestion, the past few years, of descendants of Japanese Americanincarceration, many of whom are friends, some of whom are family, some of whom Ihave never met, but know through their answers. It is an ongoing question.” Hisis a book on ancestors and the dead and how and where responsibility lands; a cross-stitchof violence and memorialization, deserts and the spaces within which one notonly occupies, but lives. He offers this insight, which I think a central pointto anyone concerned with elements of extended family, genealogy or ancestors: “Ancestorworship is a process. The exact nature of the relationship between an ancestorand their descendant is always to be determined.” As he writes:

LatelyI’ve been going through Brandon Shimoda’s most recent collection,

Hydra Medusa

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2023), a self-described continuationof his collection,

The Desert

(The Song Cave, 2018), a book I have onlyheard tell of. Hydra Medusa is a complex collection composed as a bookof dreams and death, ancestors, parenting and desert stretches through a blendof essays and poems. “Death is what it took for us to be in each other’scompany. But what kind of company was I?” he writes, two-thirds through thebook. He writes of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during and aroundthe Second World War, and of repeated murders and ancestors, and how lives can’thelp but connect to each other. Hydra Medusa is a book on the living andthe endless dead, seeking answers to questions that might be impossible toanswer, or too individual to fully articulate. As he writes, early on, as partof the essay “THE DESCENDANT”: “What is an ancestor? I have been asking thisquestion, the past few years, of descendants of Japanese Americanincarceration, many of whom are friends, some of whom are family, some of whom Ihave never met, but know through their answers. It is an ongoing question.” Hisis a book on ancestors and the dead and how and where responsibility lands; a cross-stitchof violence and memorialization, deserts and the spaces within which one notonly occupies, but lives. He offers this insight, which I think a central pointto anyone concerned with elements of extended family, genealogy or ancestors: “Ancestorworship is a process. The exact nature of the relationship between an ancestorand their descendant is always to be determined.” As he writes:The ancestors, bedeckedin robes of night

occupy a pantheon

We see ourselves in,imagine

ourselves

in the shapes

of sparest humility,

Hang me in the alcove, I say,

to the future faction

that might draw me out ofthe well

Thereis something curious about the way the non-fiction prose aims for the heart of hissubject matter, while the poems write a bit more abstract, writing as a kind ofoutline around and occasionally through that same purpose. If the prose feelsmore direct, the poems write slant, attending as a kind of connector between andamid prose sections, comparable to the abstract sections of Terrance Malick’s filmThe Tree of Life (2011) (a narrative structure more recently put to filmeffect through Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, as well). One could alsocompare this to the work of American poet Susan Howe: the call-and-response ofher poetry collections that sit with opening essay and collage-poems ascounterpoint of a larger, singular, book-length work. The difference of form isn’tmerely used to open for another, or sit in opposition but through a sense of balancebetween. The structure allows for the possibility of pulling back to see a farlarger context, one that suggests itself far larger and ongoing than what ispossible within the bounds of even this single book.

The white cross on thehill of rocks

is a house without light

over the greenest fieldsin the valley

The virgin, embedded inrocks

prepared the white cross

with the attributes oflightlessness

that illuminate subterraneanlife

where the cross entersearth

children lay flowers

the cross turns at night

into snakes (“SAN XAVIER”)