Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 80

August 22, 2023

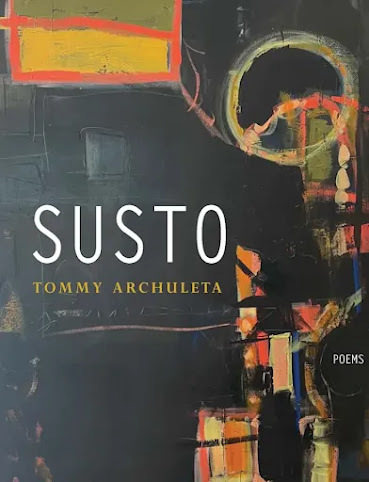

Tommy Archuleta, Susto: Poems

AFTERWORD

In the wake of my mother’sdeath, in that sheer-white numbness, Pop and I found among her things ahomemade book on curanderismo. Its contents pair physical, mental, andspiritual ailments with a particular herb, plant, or root native to northernNew Mexico. The instructions on how to prepare and administer each treatment (remedio)run from precise to vague. The paper stock is not of this century, nor of thelast; its margins are filled with notes in Spanish and English, some in pencil,some in pen. And while the writing style of the notes varies greatly, here andthere Mother’s longhand stands out. Soon after this discovery, another came myway in the form of a line that continues to play to this day: To love deeplyis to grieve deeply. Along the ground of this line a sinkhole appeared, anddown I went, emerging years later with something close to the book you how holdin your hands, kind reader.

Idon’t usually begin at the end, but there is something important in the “Afterword”of New Mexico poet Tommy Archuleta’s full-length debut,

Susto: Poems

(FortCollins CO: The Center for Literary Publishing, 2023), that seems important forhow one might begin to approach this collection. Susto is a book of grief,and how one might survive a loss so deeply felt. Composed across a sequence ofmeditative accumulations, originally prompted by the death of his mother in2013, Archuleta offers an array of first person lyric fragments interspersedamong his mother’s own words as a kind of daily meditation, one that echoes the“I remember” form by Georges Perec. He writes of dreams and the landscape ofNew Mexico, his mother’s language and the history of the region, blending allinto a singular, ongoing purpose. “Tell me again about / the saint they namedme after,” he writes, “About how she floated / when she prayed // and how youcan’t be / alive and a saint at the same time // You just can’t // You have tobe dead first [.]” Susto fractions and fractals and even pursuesgrief; composed across moments, and through stages, with poems clustered intofive sections of lyrics and the occasional prose poem. “Love as seed or love asplow,” he writes, mid-through the collection, “End as end / or end as opening// Either way why go / on fearing /the dark part // god part doorway / Go ahead // Ask me [.]”

Idon’t usually begin at the end, but there is something important in the “Afterword”of New Mexico poet Tommy Archuleta’s full-length debut,

Susto: Poems

(FortCollins CO: The Center for Literary Publishing, 2023), that seems important forhow one might begin to approach this collection. Susto is a book of grief,and how one might survive a loss so deeply felt. Composed across a sequence ofmeditative accumulations, originally prompted by the death of his mother in2013, Archuleta offers an array of first person lyric fragments interspersedamong his mother’s own words as a kind of daily meditation, one that echoes the“I remember” form by Georges Perec. He writes of dreams and the landscape ofNew Mexico, his mother’s language and the history of the region, blending allinto a singular, ongoing purpose. “Tell me again about / the saint they namedme after,” he writes, “About how she floated / when she prayed // and how youcan’t be / alive and a saint at the same time // You just can’t // You have tobe dead first [.]” Susto fractions and fractals and even pursuesgrief; composed across moments, and through stages, with poems clustered intofive sections of lyrics and the occasional prose poem. “Love as seed or love asplow,” he writes, mid-through the collection, “End as end / or end as opening// Either way why go / on fearing /the dark part // god part doorway / Go ahead // Ask me [.]”What calm

in the way the gravedigger

unbuttons his coat

and the frozen

ground below him

How it longs to be opened

You learn not to wave

at the soldier

coatless always

wandering the roads andfields

He’s home now

for good

says his mother

Yes home now

for good

say the wolves

August 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jade Wallace

Jade Wallace (they/them) [photo credit: MarkLaliberte] is the author of a poetry collection

Love Is A Place But You Cannot LiveThere

(Guernica Editions 2023), a novel Anomia(Palimpsest Press 2024), and the co-author of ZZOO (Palimpsest Press2025), as well as several chapbooks, most recently

Expression Follows Grim Harmony

(JackPine Press 2023). Wallace is alsothe book reviews editor for

CAROUSEL

and co-founder of the collaborative writing entity MA|DE. Keep in touch: jadewallace.ca

Jade Wallace (they/them) [photo credit: MarkLaliberte] is the author of a poetry collection

Love Is A Place But You Cannot LiveThere

(Guernica Editions 2023), a novel Anomia(Palimpsest Press 2024), and the co-author of ZZOO (Palimpsest Press2025), as well as several chapbooks, most recently

Expression Follows Grim Harmony

(JackPine Press 2023). Wallace is alsothe book reviews editor for

CAROUSEL

and co-founder of the collaborative writing entity MA|DE. Keep in touch: jadewallace.ca1 - How didyour first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Now is when Irealize that I actually can’t remember my first chapbook specifically. It wasthirteen years ago, and a few of them came out in quick succession. I’m notsure anymore which was first.

My first book,however, just came out in April: Love Is A Place But You Cannot LiveThere (Guernica Editions). Mostly I feelrelief. Yes, I am a person capable of writing a book other people will want topublish and read. Whatever doubts I still have (and there are many), I can’thave that one anymore.

From my firstchapbook to my debut poetry collection to what I’m working on now, I would saythe general trajectory is toward the stranger, the more complicated, and themore plural.

2 - How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Absolutelypoetry was first for me. Poetry is still first for me. I have no idea why, Ijust accept the inevitability of it. If my prose doesn’t sound a bit likepoetry, I invariably think it’s no good. I have a novel coming out next year, Anomia,with Palimpsest Press, and a lot of the “chapters” probably read more likeprose poems than fiction. Some may see that as a fault, but even the prose Iprefer to read is the kind that’s preoccupied with imagery, and the sound ofwords, and enigma at the heart of language, and whatever else poetry is about.

3 - How longdoes it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I do everythingquite slowly. I thought about my novel for years before I started it. Then ittook still more years to write. Poems are not quite so bad, but I often thinkabout a poem for weeks or months before I sit down to it. For any genre ofwriting, there is usually one atrocious draft, sometimes short and sometimeslong but always a mess, and then there is a draft that looks like a story orpoem, and then usually there is a third version that is readable and needs onlya little more prodding to be done. No one, not even the people I trust most,sees anything until it’s at least at the second draft stage.

4 - Wheredoes a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

A poem alwaysbegins with a problem I cannot solve. At any given time in my life, I tend tobe preoccupied with a certain problem or set of related problems, and all thepoems I write orbit around that fixation. Sometimes I realize what’s happeningin advance, and the book concept precedes the poems, but even when I don’t it’susually apparent pretty early on.

Like with whatI hope will be my second full-length poetry collection, The Work Is DoneWhen We Are Dead, I was thinking a lot about the problems of labour. Ithought about it while I was at my day job, I thought about it when I wasvolunteering, I thought about it when I was trying to manage my personalrelationships, I thought about it when even making art had begun to feel likework. It was easy to write a big set of poems about the same subject; it washard to make that particular subject fun. I think I succeeded, but then again Ihave very dowdy notions of what’s fun. Crossword puzzles are deeply exciting tome, for example.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doingreadings. In every book, I feel it’s essential to have at least a few poems orstories or excerpts that will be thrilling (for me at least) to read aloud.Usually they are pieces where the voice is very distinct, or the rhythm isquite pronounced, or the language is slippery and playful. If I feel a piecewill lend itself well to being read, I will turn up the volume on thosequalities during editing.

I love doingreadings but I loathe being away from home, so it can be a struggle. When Icame back from my first tiny book tour in August, which was only a week long,by the way, I was about ready for a nervous breakdown.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

Always, butthey vary from project to project. I started reading philosophy as a teenagerbecause I was very interested in the questions it attempts to answer, but Ifound the way it answered them to be desperately unfulfilling. The philosophersI ended up enjoying most were the very literary ones, like Camus, and Ieventually realized I wanted the promises of philosophy in the package offiction or poetry. So that’s what I try to write.

I guess if youwanted the very simple version, there are two basic questions at the crux of mywork: “Why do we bother?” and “What shall we bother with?” Each project answersthose questions differently.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

For me,literature and sunlight are about the only consistent things that make me wantto go on with life day to day. There seem to be some writers who don’t feel agreat need to read, and maybe they would be happy being the only scribes onearth, but I experience reading and writing as a kind of ongoing conversationwith the world around me. As in any social situation, I prefer to listen morethan I speak.

If writing hasany purpose other than this, I don’t know about it.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

Certainly both.Unless you’re keeping a diary, writing is a communal practice. I want to knowhow other people will respond to my work, and to control for their reactions tosome extent, while also being aware that the extent of my control is extremelylimited, which is both exciting and horrifying.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Keep at it.

10 - Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to collaboration)? Whatdo you see as the appeal?

In my work,poetry and collaboration are overlapping genres. Strangely, I findcollaboration easier to dig into sometimes. Maybe because you can’t have an egoabout the kind of writing I do as MA|DE with my partner Mark Laliberte. “My”voice and “his” voice dissolve, and MA|DE has a single, unified “third” voicethat I am a part of but that doesn’t belong to me, so I can’t feel particularlyself-conscious about anything I contribute. It’s easier to sing in a choir thansing solo I guess. That is very freeing, at least at the drafting stage. Laterwe go back in together and edit everything so it’s harmonious and precise,which is not freeing but it is as easy as editing ever is.

11 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

Not to be toobohemian about it, but for me art and routine are antithetical. If my writingprocess is too prescribed, I start to resent it. Instead I try to have severalwriting projects, and a never-ending list of related administrative tasks,bouncing around at any given time, and I’ll tackle at least one of them almostevery day. How much time I spend and which one I do depend on my mood.

It’s like howsomeone who loves reading tends to have stacks of books all over their houseand will on most days probably pick up one or two books and read a bit fromthem, without a need for scheduling the books they’ll read or how many pagesthey’ll read each day.

12 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

If I feel likeI lack ideas, I pick a book off my shelf that interests me and read. I don’tthink too hard about which one. It usually ends up being relevant. If I feelrestless or uninterested in the project, I’ll go for a walk or play guitar ordo literally anything else. Life is too short to spend trying to force myselfto be interested in things that are not urgent. If it’s a good project, myinterest will return soon enough anyways.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

My parentsbuilt a log house and that’s where I lived for the first twenty years of mylife, so pine always smells like home. My mom hung pomanders whenever citruswas in season, so oranges and cloves smell like home. My dad did automotivework in our basement and driveway so gasoline and engine grease smell likehome. I spent all the spare hours of my childhood and adolescence in a horsestable, so hay smells like home, too.

14 - DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

It’s only booksthat make me want to write books, but it’s the other things in my life thatgive me things to write books about. I spend an awful lot of time thinkingabout our home garden, and how it’s a way of interacting with the local floraand fauna. Just before I started this interview, I was reading this great thread by writer Leah Bobet on practicalthings we can all do for the environment—and no it’s not a list of things youcan give up, it’s about constructively beneficial actions we can take, likemaking pollinator gardens in any space, no matter how small.

I also spend alot of time with “true crime” media, which might seem odd because I am adie-hard pacifist who hates causing or experiencing harm (I get genuinely upsetwhen bugs die), and who has enormous qualms about judicial and prison systems,but my interest in “true crime” goes back to my preoccupation with problems wecan’t solve. Murder is a rather fascinating example of a problem that can’t besolved, per se, and yet there are so many ways to lessen the likelihood of ithappening and to deal with the aftermath when it does, if we can understand howand why it occurs in the first place and what the far-flung effects of it are.

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Unexpectedly,Tennessee Williams has remained a long-time love of mine ever since I read TheGlass Menagerie in high school. I hardly read plays, and there are fewthings from high school I still enjoy, but I’m well on my way to collectingevery work of his that was ever published. To me he’s a great example ofsomeone who’s not writing poetry but always has poetry in his writing.

Otherwise I’m abit of a goldfish—whatever I’m reading at the time is probably what’s mostimportant to me. Right now I’m absolutely delighted by The Ants bySawako Nakyasu (Les Figues Press), a charming and unnerving collection of prosepoem type pieces that “takes the human to the level of the ant, and the ant tothe level of the human.”

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Relax.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, like mostwriters, I have no choice but to do other jobs as well. Most of that work, forme, has been in legal clinics, but I’ve also spent a lot of time being a gradstudent, and some amount of time being an editor, and in previous lives I’veworked in a horse stable and a Chinese restaurant. I suppose if I weren’tfrittering away my time with poetry I’d be trying harder to become a lawyer orprofessor. All of my other hobbies—growing plants, baking cakes, playinginstruments—are not things I would want to do full-time.

18 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

There wasnothing else.

19 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

For this I’llneed to consult my records.

According to mybooklist, some of my favourite reads of 2023 included poetry collections likeCecily Nicholson’s Harrowings (Talon Books), Anahita Jamali Rad’s still(Talon Books), natalie hanna’s lisan al’asfour (ARP Books), andHollay Ghadery’s Rebellion Box (Radiant Press); short story collectionslike Corinna Chong’s The Whole Animal (Arsenal Pulp Press) and JeanToomer’s Cane (Mint Editions); and graphic novels like Joe Kessler’s TheGull Yettin (New York Review Comics).

According to myLetterboxd account, my favourite recently watched films are George Kane’s Crashing(2016), which is only debatably a film, but I enjoy everything writes, Sarah Polley’s Take This Waltz (2011), though thatmight only be because it too closely mirrors my twenties, Donna Deitch’s DesertHearts (1985), which is a queer classic and hard not to like, and ParkChan-wook’s Decision to Leave (2022), which was generally brilliantthough I confess I was disappointed by the ending.

20 - Whatare you currently working on?

I think myaforementioned, hopefully sophomore poetry collection, The Work Is Done WhenWe Are Dead, is basically complete, less a few nitpicking edits I willcontinue to make until a publisher takes it out of my hands, so I am planningto spend more time with a couple of MA|DE’s many projects:

Waste Not the Marrow, a hybrid collection of collage-sculptures and ekphrastic poetry (as previously featured in The Ex-Puritan, for example).

I’m alsogrudgingly contemplating what I need to do to finish and fix up my firstmanuscript of short fiction—the most significant challenge is trying toresist the urge to turn all the pieces into poems.

August 20, 2023

Heidi Greco reviews essays in the face of uncertainties (2022) in subTerrain #94!

Thanks much to Heidi Greco, who reviewed my suite of pandemic essays, essays in the face of uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022), in subTerrain #94! Naturally, you can order a copy of the book from the publisher directly, or even from me! Here's an excerpt of her review (the review is roughly three times longer than this):

mclennan is also amazingly widely-read. I can only imagine the bookshelves in his home. Nearly every essay references the work of some writer -- from those whose work I know to those well beyond my ken. [...] Yet this book isn't some high-falutin' literary treatise; it's an extended diary and includes bits of material long since posted on his blog -- often about matters as mundane as washing floors, doing laundry, and dealing with grocery shopping. It's also about some of the grim realities of the pandemic -- the death counts so high in New York that refrigerator trucks serve as temporary morgues, the absurdities of valuing the economy over the preservation of lives. These were also the days when Breonna Taylor and George Floyd died at the hands of police, causing racial tensions to surge. Personal loss also figures into these pages; he addresses the difficulties of unresolved grief from not being able to observe the rituals many of us rely upon for dealing with death.

On the other hand, there is also much in the way of abounding joy, often via the behaviours of his six- and four-year-old daughters, Rose and Aoife. They build Lego villages on the dining room table, and go through what often sounds like a repertoire of costume changes over the course of a day -- from dressing like a cat or a witch or an elf to donning bathing suits and pretending to swim indoors. As for his own sartorial splendours, the author takes pride in earning an award for the 'best beard' during Covid, and even admits to wearing house slippers when he runs errands. Truly, a man after my own heart, though even he draws the line at what Fox Mulder warned about in an old X-Files, "...the return of drawstring pants."

This book is a kind of time capsule for the future -- documenting a period of collective uncertainty, when we were isolated from one another, not only physically, but to an extent, psychically. A time when one of mclennan's steady refrains was our most reliable reality: "We wash our hands. We wash our hands." A time that we can only hope we have finally (at least mostly) left behind.

August 19, 2023

Mia You, Rouse the Ruse and the Rush

The blood hasturned

darker andthicker,

brown smearedacross

white cloth, as if

a paletteknife was taken

to this womb,and here

are the scalesof the

raspberry shaped

insect, ground

into poppyseed

oil and earth,

and beneath that,

dead-color,

doodverf,

of the groundthat held

you until the

rustle and the

rush insisted

you could not

stay.

I’mvery pleased to be able to go through the latest title by Mia You, her

Rouse the Ruse and the Rush

(Berkeley CA: Nion Editions, 2023), a book-lengthlyric with accompanying art by Fi Jae Lee, produced in a sleek and graceful hardcoverletterpress edition of one hundred and fifty copies. As it states in You’s bio,she was “born in Seoul, Korea, grew up in Northern California; and currentlylives in Utrecht, the Netherlands,” and is the author of the poetry collection

I,Too, Dislike It

(1913 Press) and the chapbook

Objective Practice

(Achiote Press) [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here]. Rouse theRuse and the Rush is a book-length lyric writing translation and ekphrasisthrough the body, blending separate threads into a weave of between-ness, onestate into and across another. “The title Rouse the Ruse and the Rushplays on the name Ruysch,” You offers, to begin her introduction to thecollection, “which belonged to the Dutch ‘Golden Age’ painter of floral stilllifes Rachel Ruysch (1665-1750) and her father, Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), ananatomist and botanist well-known for his innovative embalming techniques. WithRachel’s help, Frederik created a series of dioramas incorporating human,mostly fetal, body parts and decorative elements such as lace ribbons, pearls,and coral that were collected as art. Almost a thousand of these dioramas arestill on display in St. Petersburg, where they went after being purchased in1713 by Peter the Great.” You’s extended lyrics writes around and through thetwo Ruysch’s and their works, writing on painting and life, stillness and autonomy.“I’m nearly alive / as many years as Vermeer,” she writes, near the end of herbook-length poem, “and as a woman / that means / I’m even older // and I’venever known / a scenario in which / the opposition / is truly between // choiceand life [.]” Further on in her introduction, she adds:

I’mvery pleased to be able to go through the latest title by Mia You, her

Rouse the Ruse and the Rush

(Berkeley CA: Nion Editions, 2023), a book-lengthlyric with accompanying art by Fi Jae Lee, produced in a sleek and graceful hardcoverletterpress edition of one hundred and fifty copies. As it states in You’s bio,she was “born in Seoul, Korea, grew up in Northern California; and currentlylives in Utrecht, the Netherlands,” and is the author of the poetry collection

I,Too, Dislike It

(1913 Press) and the chapbook

Objective Practice

(Achiote Press) [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview here]. Rouse theRuse and the Rush is a book-length lyric writing translation and ekphrasisthrough the body, blending separate threads into a weave of between-ness, onestate into and across another. “The title Rouse the Ruse and the Rushplays on the name Ruysch,” You offers, to begin her introduction to thecollection, “which belonged to the Dutch ‘Golden Age’ painter of floral stilllifes Rachel Ruysch (1665-1750) and her father, Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), ananatomist and botanist well-known for his innovative embalming techniques. WithRachel’s help, Frederik created a series of dioramas incorporating human,mostly fetal, body parts and decorative elements such as lace ribbons, pearls,and coral that were collected as art. Almost a thousand of these dioramas arestill on display in St. Petersburg, where they went after being purchased in1713 by Peter the Great.” You’s extended lyrics writes around and through thetwo Ruysch’s and their works, writing on painting and life, stillness and autonomy.“I’m nearly alive / as many years as Vermeer,” she writes, near the end of herbook-length poem, “and as a woman / that means / I’m even older // and I’venever known / a scenario in which / the opposition / is truly between // choiceand life [.]” Further on in her introduction, she adds:Fi Jae’s articulation ofthe multilayered self resonates with my own attempt to map the cosmology of thereproductive (in this case, female) body in Rouse the Ruse and the Rush.Further, her drawings visualize to me the ways in which we can push beyond thelimited vocabulary employed when defining “personhood” and the status of “humanbeing,” and when seeing them as absolute values. In 2022, history has shown us,and the future warns us, that these categorization are inadequate fordetermining who or what has the right to life and who or what has the right tochoose what can happen to their bodies. Bodily autonomy is the modern world’sgreatest mythology. For those of us nonetheless determined to see greaterreproductive justice in this world, we need new terms for regarding the bodies weinhabit and the varying bodies that inhabit us.

Nion Editions is a small press run out of Berkeley by Jane Gregory, Lyn Hejinian and Claire Marie Stancek, producing some stunning titles, with a simultaneous titleby Ed Roberson, and even one forthcoming by Lisa Robertson. “definition is astill-life,” You writes, mid-way through the poem, “a well-crafted ruse, / sowhat can translation be, / but noise that comes / to rest in song?”

At the bottom of the aquarium

is a pearl and a grain ofsand.

The pearl says, “Grain ofsand,

why must you always writein

such long, unreadablesequences?”

The grain of sandreplies, “O Pearl,

you always emerge tosurprise

and with such glory,

but for me, but for me,

I’m so scared

of ever leaving anything

on its own.”

August 18, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jed Munson

Jed Munson is the author of the essay collection

Commentary on the Birds

(Rescue Press, 2023), as well as the poetry chapbooks Portrait with Parkinson's (Oxeye Press, 2023),

Minesweeper

(New Michigan Press/DIAGRAM, 2023), Silts (above/ground press, 2022), and

Newsflash Under Fire, Over the Shoulder

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021). He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Jed Munson is the author of the essay collection

Commentary on the Birds

(Rescue Press, 2023), as well as the poetry chapbooks Portrait with Parkinson's (Oxeye Press, 2023),

Minesweeper

(New Michigan Press/DIAGRAM, 2023), Silts (above/ground press, 2022), and

Newsflash Under Fire, Over the Shoulder

(Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021). He lives in Brooklyn, New York.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

UDP published my first chapbook Newsflash Under Fire, Over the Shoulder, in 2021. More than anything, it was my editor, Lee Norton, who changed my life by believing in the work and the play. My recent writing feels lower to the ground, slower, maybe also louder.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Attempting fiction and nonfiction writing in college was how poem writing first happened to me--I'd jot down ideas for essays or stories I couldn't actualize offhand, stuff to unpack later, and littered a bunch of notebooks like that. When I of course never unpacked anything I realized I was enjoying more than anything the poetic potentiality of that shorthand. Then weirdly poems taught me how to reapproach prose with a more poetic posture, which has helped prose feel lively again.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Takes forever, then suddenly it's over. The gathering and positioning of the body and mind is the mysterious and laborious part for me. Once I'm in compositional time, I'm just occurring with the thing and adjusting to it. More and more those stretches/pockets feel like a gift.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems tend to start as sound for me, in the air, usually when I'm walking or in a space in the day where it feels possible to ask a question, even a basic one, like what now? Then I work something out by hand in a notebook, pen and paper, sometimes many times, then transfer it into a document when the pages start to get so cluttered I can't see the sound/thing anymore. So I go from trying to hear the thing to trying to see it. It's in the document phase, when I'm working with something as standardized text, that it starts to harden into something that feels like a poetic object, as if the ease of pushing something around in a text doc is concurrent with the imminent sense of its hardening. That's when I think I try to feel the poem, fix it until I think I feel it as an organism. Essays actually work similarly, or I've been applying my process with poems to prose writing. Books are still mysterious to me. I have no idea what a book is but I would like to write a good one.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like readings that are small enough for the mic to feel optional and the reading poems part to feel optional. BYOB!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Lately I'm interested in the aroma of math in poetry.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Good question. Maybe the writer should write. Despite the world and because the world.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I enjoy editorial relationships because they're basically just collaborations to my mind, an extension of the writing process where writing exits the fiction of your control. Which can be frustrating of course, or miraculous.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

If you don't want your porch pumpkin to rot so quickly, turn it upside down on its stem so that it thinks it's still in the ground. (--My grandma)

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

Essays felt possible to me once I'd been reading and writing poems for a while and wanted to try applying poetic patterning to prose. I do think essays are a powerful field/form for showcasing thinking. I admire clear thinking but am not great at it. Essays help me discover moments of clarity though. They let me manage content and information more than poetry, but they can behave like poems. It's the saying power of essays that I appreciate, how they feel directed at a cry for truth. Sometimes you want to say something about something, and you want it to be understood that it's real.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write what I can when I can and rejoice when it happens. I'm constantly dreaming of a life where it happens more often and I'm not overwhelmed by the sense of guilt for stealing the time from something else I should be doing.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I usually read good poems or talk to my sister.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Muted kimchi and garlic, mowed lawn smell, tinge of mildew and moth balls.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above!

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Trilce by Vallejo.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write actually accomplished poems in Korean.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

This is all I've got.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

This is all I've got.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Pink Noise by Kevin Holden--a great book by a great poet. I watched Totoro for the millionth time with some kids and my sister the other week and it's the greatest. Perfectly compact, digressive, stirring, fortifying. The kids had a gleeful scream in that scene where Totoro yawns. I can't stop thinking about it. Totoro's mouth is so tiny, like a pinhole, and then suddenly it's so big!

20 - What are you currently working on?

Joy.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 17, 2023

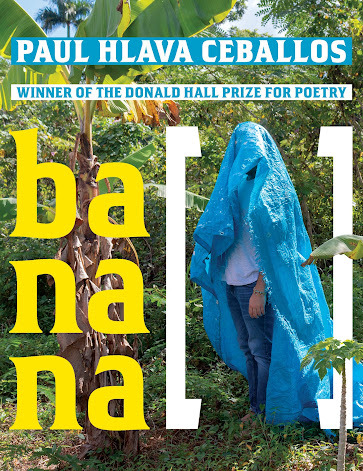

Paul Hlava Ceballos, banana [ ]

Genesis

The first day in the garden,God was

an immigrant who plantedgulls

in clouds. Even thesmallest

leaflet untangled

solar filaments with prudence

dissimilar to fire.

If culture’s root iscare, it matters

the object of care is visible.

Did Adam first teach Godthe word semilla

or resource extraction?

Did God lack the word formonocrop

when she raised its sugarfrom raw earth?

Each body has its ownsmall gravity.

The banana pulled theworld when it fell.

Winnerof the 2021 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry is Seattle-based poet Paul Hlava Ceballos’ full-length poetry debut,

banana [ ]

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022),published as part of the Pitt Poetry Series. banana [ ] is a collection of powerful lyricsthat manage a lean density, intertwining personal and political histories, and offeringa perspective from a culture too often deemed outside the American centre. Hewrites of racism, from an underpinning of language and violence to elegies ofthose lost through the deliberate actions of those claiming to exist asprotectors. “When a concerned citizen pinned / me to airport wall to check my// origin,” he writes, as part of the poem “Split,” “I whispered, thank you. /My dad says, Good, we’re safer now. / My uncle: then leave the country.” Hewrites of American imperialism across Central America, and of the ongoing tollendured through violences ranging from cultural and human devastation to themost casual and everyday act of racism and dismissal. He writes of a culture toomany self-buried, in order to survive, or even endure. “So she cut her nativetongue to protect her kin,” he writes, as part of the second poem “Genesis,” whichopens the book’s third section, “forced me to scrub peeling linoleum on myhands and knees / handed down ass-whoopings with a wooden spoon / dabbed lagañasat weepy corners of midnight [.]”

Winnerof the 2021 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry is Seattle-based poet Paul Hlava Ceballos’ full-length poetry debut,

banana [ ]

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022),published as part of the Pitt Poetry Series. banana [ ] is a collection of powerful lyricsthat manage a lean density, intertwining personal and political histories, and offeringa perspective from a culture too often deemed outside the American centre. Hewrites of racism, from an underpinning of language and violence to elegies ofthose lost through the deliberate actions of those claiming to exist asprotectors. “When a concerned citizen pinned / me to airport wall to check my// origin,” he writes, as part of the poem “Split,” “I whispered, thank you. /My dad says, Good, we’re safer now. / My uncle: then leave the country.” Hewrites of American imperialism across Central America, and of the ongoing tollendured through violences ranging from cultural and human devastation to themost casual and everyday act of racism and dismissal. He writes of a culture toomany self-buried, in order to survive, or even endure. “So she cut her nativetongue to protect her kin,” he writes, as part of the second poem “Genesis,” whichopens the book’s third section, “forced me to scrub peeling linoleum on myhands and knees / handed down ass-whoopings with a wooden spoon / dabbed lagañasat weepy corners of midnight [.]”Ceballos’use of experimental form and structure engages with a culture that has, overtime, become essentially interwoven into the fabric of the American cultural andpolitical landscape. “Immigration is not a void / of desire nor long histories/ of dropped fire that blossoms in air,” he writes, to open the poem “Blossom IsPollen in Transit.” The poem, further on, ending: “can we plumb blue depths ofthose shared / years to be not-numb not-nothing / whole as a neighbor as a kiss[.]” He works through the threads of history, of histories, offering an insightfrom a perspective that refuses to be overrun, and stories that need to betold. He writes of border patrols, and an agent involved with a shooting, lostkingdoms, and, as the poem “Elegy for Sergio Adrián Hernández Güerca” writes, a“boy-shaped body / in permanent fall [.]” As the poem “Rahua Ocllo, Queen andMother,” one of six poems in a suite of “Kingdom of the Americas Sonnets” ends:“Men taught me body is a debt / to lust or sun-god, paid with life. / I wasborn, married off, alive / as curse. When a white man bought me, // he did notknow my pitted heart. / I smile. My love will bury him.”

August 16, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Stephanie Austin

Stephanie Austin

is the author of

SOMETHING IMIGHT SAY

out now from WTAW Press. Her short stories and essays haveappeared in more than 25 literary journals in the United States and Canada. Sheruns the Mugshot Writers project on Instagram @mugshot_writers2 You cansubscribe to her newsletter or learn more about her writing at her website:stephanieaustin.net

Stephanie Austin

is the author of

SOMETHING IMIGHT SAY

out now from WTAW Press. Her short stories and essays haveappeared in more than 25 literary journals in the United States and Canada. Sheruns the Mugshot Writers project on Instagram @mugshot_writers2 You cansubscribe to her newsletter or learn more about her writing at her website:stephanieaustin.net1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book just cameout July 18. I don’t know how it feels yet. I’ve spent twenty years workingtoward a book publication. It feels surreal. Also, oddly, hard to accept?Success is, bizarrely, sometimes a harder pill to swallow than failure.

2 - How did you come toshort stories first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

When I was growing up, Iwanted to write screenplays. (I still want to write screenplays.) Then Istudied creative writing and thought I’d write novels. But you don’t studynovels in early CRW classes, you study short stories, which is awesome, butthen it’s also unsustainable because no one publishes short story collections[except for the people who do but those people are fledging small presses (orbigger presses you get by lucking into an agent because you have an interlinkedstory collection which is basically a novel)].

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Sometimes it’s lighting tothe heart and sometimes it’s a slow burn.

4 - Where does a work ofprose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I start with whateversadness rises to the top that day. I’ve written two novels and am working onthird and a bunch of short stories that when put together aren’t exactly interlinkedbut aren’t not connected.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

The first reading I didwas about 18 years ago. The journal I was reading for was new, so new theyprinted pages from a Word doc and put it in a single binder which people couldbrowse when they entered the room, which was not a literary event, per se, butit was a multicultural event that included a fashion show. The journal askedthe readers to get up and read between breaks of the show, but they forgotabout me and/or didn’t plan well so by the time it was my time, I read to myfew friends who stayed all day and the editor of the journal and the otherwriter who I think they also forgot about. The fashion show portion ended. Mostof the audience had left. We’d been there four or five hours. After I read, Iwas so overcome with hunger, I left and took my friends with me. We left thelast reader to read just to the editor of the journal in an empty room and tothis day I feel both guilty about that but also remember how desperate andconfused I was during the entire day. Readings are better now! I’ve only done ahandful of public readings but that seems to be picking up steam lately.Readings can be super boring or the most awesome thing you’ve been to all week.I try to be lively and entertaining when I read. I’m a work in progress.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Sadness, family trauma,childhood trauma, sexual assault, anxiety, addiction, nostalgia. I think latelythe question I’m trying to answer is: Is it possible to co-exist with your ownbullshit? Can you reconcile your own bullshit and find a path forward?

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers can often putwords to what others are feeling but can’t say. That’s the kind of writer Istrive to be.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It is difficult andessential. I absolutely need an editor. Everyone needs an editor. Sometimes (Ihave not had this experience) editors can be heavy-handed and want to take overbut 99% of them work toward making the work better.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Find the heat in yourstory and stay there, the more uncomfortable the better.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (short stories to essays)? What do you see asthe appeal?

The truth here is most ofmy short stories could be essays and vice versa. I write from personalexperience. Everything I write stems from some lived experience.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I work full-time, and Ihave a kid. I don’t have a routine. I write when I get a chance, mostly late inthe evening or early in the morning (like 5 a.m. even on weekends).

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

Music. I’ll go back andfind music from whatever particular period of my life I’m sorting out that day.Sometimes the music is bad, but hat’s between me and my playlists.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Ashtrays. Not kidding.Cigarettes. I was a child of the 80s. Everyone smoked.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music all the way. Butagain, I sometimes like very bad music. I am/am not ashamed of some of themusic I listen to. I’ll be like, oh hey guys, I listened to Ruston Kelly forfour hours and felt the earth move. I don’t necessarily admit that I boppedalong to Extreme’s Hole-Hearted.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’m a huge fan of otherwriters. Sometimes when I’m lagging in my own work I give up for awhile and go backto reading and almost always find the way forward by remembering what moves mewhen I read. The reading comes first.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

I’m looking for a timemachine to take me back into the 80s where I plan to burst onto the scene withJay McInerney and go to high profile literary events wearing all black, smokingCamels, and drinking expensive red wine paid for by Vintage Books while Amanda Urban’s assistant tracks me down for a cocktail lunch.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Psychiatry. Counseling.I’d lean forward and ask people to tell me about the moment when they realizedthey were no longer a child and we’d process that profound sense of losstogether. Also I would like to be a jazz singer but I can’t sing.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

I literally have no otherskills. My single talent in this world is to analyze my own bad choices. I amnot an athlete, I can’t sing, I don’t have artistic ability, my fashion senseis poor, I don’t know how to work TikTok, no one cares if I’m drinking out of aStanley mug-thing, and I have no rhythm.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Jonathan Escoffrey’s IfI Survive You.

I don’t get to watch a lotof my own shows. My daughter gets most of the TV time. We saw Barbietogether and I openly wept at certain points. I think that counts? I also saw Promising Young Women recently (it’s already like 5 years old I think) and I loved itbut later read mixed reviews so taste is always subjective.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

A novel about going to asupport group for people with bad dads. Revising a novel about a teenage ghostwho gets trapped on a baseball field. Polishing a story collection about howlosing one’s virginity is a set-up for a decade of dating failure. An essaycollection about grief and loss.

August 15, 2023

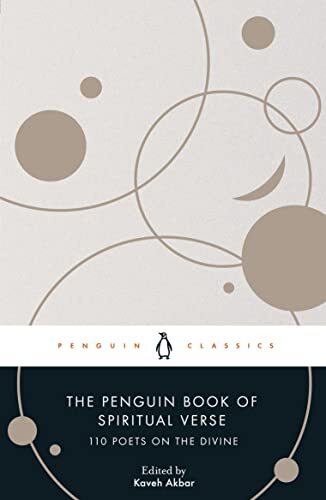

The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 110 Poets on the Divine, ed. Kaveh Akbar

The earliest attributable author in all of humanliterature is an ancient Sumerian priestess named Enheduanna. The daughter ofKing Sargon, Enheduanna wrote sensual, desperate hymns to the goddess Inanna: ‘Mybeautiful mouth knows only confusion. / Even my sex is dust.’ Written around2300 BCE, Enheduanna’s poems were the bedrock upon which much of ancientpoetics was built. And her obsession? The precipitating subject of all ourspecies’ written word? Inanna, an ecstatic awe at the divine.

A year after I got sober, I learned from a routine physicalthat my liver was behaving abnormally, teetering on the precipice of pre-cirrhosis.This was after a year of excruciating recovery, a year in which nothing harderthan Ibuprofen passed through my body. If it’s this bad after a year ofhealing, a nurse told me, imagine how bad it must have been a year agowhen you quit.

My earliest formulating of prayer was in Arabic, thatbeautiful, mysterious language of my childhood. I’d be called away fromwhatever trivia book I was reading or Simpsons episode I was watching tojoin my family in our ritual of collectively pushing these enigmatic sounds throughour mouths. Moving through the postures of devotion in our kitchen, watching myolder brother, my mother, my father, I had no idea what any of it meant, but I knewit all meant intensely. (“Introduction”)

Thebiggest reason I requested a copy of the new anthology The Penguin Book ofSpiritual Verse: 110 Poets on the Divine (Penguin Random House UK, 2023)was due to the book’s editor, Tehran-born American poet and editor Kaveh Akbar.If you know anything about Akbar’s work, whether his bestselling full-lengthpoetry debut Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Farmington ME: Alice James Books,2017) [see my review of such here] or follow-up, Pilgrim Bell: Poems(Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], it wouldbe fair to suggest that anything he does is very much worth paying attention to(and honestly, his introduction to this collection is worth the price ofadmission alone). The range of writing that Akbar includes here is breathtaking,moving across and beyond canonical poets from a purely Western tradition and perspective—onepoem per author, given there are one hundred and ten contributors, with a shortsummary-sketch to accompany each contribution, composed by Akbar—into an arrayof multiple cultures and languages, expanding not only the lyric sense of thedivine, but of poetry and literature itself. As Iraq poet Rabi’a al-Basri (c.717-801) writes in an untitled piece included in the collection, as translatedby Charles Upton:

O my Lord,

the stars glitter

and the eyes of men areclosed.

Kings have locked theirdoors

and each lover is alonewith his love.

Here, I am alone with You.

AsAkbar’s note to accompany writes: “Freed from slavery at a young age, whenher master saw her praying alone surrounded by celestial light, Rabi’a becamean early Muslim ascetic, spiritual leader and poet. Late in her life, whenasked about the origin of her wisdom, she replied: ‘You know of the how, I knowof the how-less.’” Akbar includes works by Virgil, King David, Sappho andLi Po, and by Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, W.B. Yeats and ConstantineCavafy, but also from Patacara (Sixth century BCE, India), Shenoute (c. 360-c.450 CE, Egypt), Kakinomoto Hitomaro (c. 653-c. 707, Japan), Uvavnuk (Nineteenthcentury, Igloolik), Oodgeroo Noonuccal (1920-1993, Australia) and Toronto poet M.NourbeSe Philip, among a wealth of others. As Akbar writes of the poet Uvavnuk,from Igloolik, an Inuit hamlet in Nunavut, Northern Canada: “The great Inuitpoet and spiritual healer Uvavnuk was said to have been struck by a meteor thatbestowed her with visionary powers. The movement of the divines celebrated inthis poem – the sea and the wind – feel in her language like ecstatic occasionsfor great celebration.” And her short poem, as translated by Jane Hirshfield:

The Great Sea

The great sea

frees me, moves me,

as a strong river carriesa weed.

Earth and her strongwinds

move me, take me away,

and my soul is swept upin joy.

Myown sense of the spiritual, of the divine, has always remained at a distance: Iwas raised attending religion but never garnered a faith (I write poems for aliving, so I don’t think I can claim to live without faith), growing up amongstthe dour, stoic and unspoken ripples of old-style Scottish Protestantism. It wasyears before I understood my father’s own devotion, let alone the depth of it,attending weekly services as far more than a matter of routine or culturalhabit, always appearing to me as a matter of custom, gesture and rote. I’velong repeated that I’m somewhere between atheist and agnostic – I’m not surewhat I don’t believe – but hold an admiration for those who carry spiritualityas a matter of good faith, instead of, say, those who believe uncritically(including a refusal to question, which seems unsettling), or use any of theirbeliefs as bludgeon, or as a false sense of entitlement or superiority. Listen toStephen Colbert, for example, speak of his Catholicism: an interview he didwith Jim Gaffigan a couple of years back on The Late Show I thoughtquite compelling, in which they spoke of their shared faith. There are ways tobe positive, and through this collection, Akbar not only finds it, but seeks itout, and embraces it.

Myown sense of the spiritual, of the divine, has always remained at a distance: Iwas raised attending religion but never garnered a faith (I write poems for aliving, so I don’t think I can claim to live without faith), growing up amongstthe dour, stoic and unspoken ripples of old-style Scottish Protestantism. It wasyears before I understood my father’s own devotion, let alone the depth of it,attending weekly services as far more than a matter of routine or culturalhabit, always appearing to me as a matter of custom, gesture and rote. I’velong repeated that I’m somewhere between atheist and agnostic – I’m not surewhat I don’t believe – but hold an admiration for those who carry spiritualityas a matter of good faith, instead of, say, those who believe uncritically(including a refusal to question, which seems unsettling), or use any of theirbeliefs as bludgeon, or as a false sense of entitlement or superiority. Listen toStephen Colbert, for example, speak of his Catholicism: an interview he didwith Jim Gaffigan a couple of years back on The Late Show I thoughtquite compelling, in which they spoke of their shared faith. There are ways tobe positive, and through this collection, Akbar not only finds it, but seeks itout, and embraces it. Thereis such a lightness, a delicate touch to the poems assembled here, one thatbroadcasts a sense of song and a sense of praise to the notion of finding thatsingle spark of light in the dark. “Somehow eternity / almost seems possible /as you embrace.” writes Ranier Maria Rilke, as part of ‘The Second Duino Elegy’(as translated by David Young), “And yet / when you’ve got past / the fear inthat first / exchange of glances / the mooning at the window / and that firstwalk / together in the garden / one time: / lovers, are you thesame?” There is such a sense of joy, and hope, and celebration across thiscollection of lyrics, traditions, cultures, languages and faiths. If there is athread that connects us all together, might it be the very notion of hope? If thiscollection is anything to go by, that might just be the case. Whether spiritualor otherwise, this is an impressive and wonderfully-expansive collection thatcan only strengthen the heart.

August 14, 2023

Adams (birth) Family Gathering, 2023

Christine, our young ladies and I recently attended an extended weekend family gathering of "cousins," etcetera, via my birth mother's family (you can see wee Aoife in the background of this picture, upon my shoulders), which was enormously fun. It was the first I'd met most of them, having previously interacted with birth mother a couple of times, as well as three of her six siblings. It was absolutely lovely! Apparently there are around twenty cousins, with twelve in attendance at this event (myself included). I spent two full days in the company of a variety of relatives, some of whom I'd been interacting with here and there via social media, and none save one cousin and birth mother's siblings who even knew I existed, prior to three years ago.

Christine, our young ladies and I recently attended an extended weekend family gathering of "cousins," etcetera, via my birth mother's family (you can see wee Aoife in the background of this picture, upon my shoulders), which was enormously fun. It was the first I'd met most of them, having previously interacted with birth mother a couple of times, as well as three of her six siblings. It was absolutely lovely! Apparently there are around twenty cousins, with twelve in attendance at this event (myself included). I spent two full days in the company of a variety of relatives, some of whom I'd been interacting with here and there via social media, and none save one cousin and birth mother's siblings who even knew I existed, prior to three years ago. Julie, myself + birth mother, Elsie

Julie, myself + birth mother, ElsieIt was odd to be in a grouping of anyone who looked like me, let alone so many. I am deeply grateful to my cousin Julie and her husband John, who hosted the weekend at their old stone house just outside Moscow, Ontario (north-ish of Napanee/Kingston). And only the third (and fourth) time I'd seen birth mother in person! And only the second time she'd seen our young ladies! So the opportunity to connect (and ask questions/gather stories) was invaluable.

It was a surreal experience, as one might imagine, but I attempted to be in the moment as much as possible, and not overthink the whole thing. Cousins! So many cousins! (although perhaps it would be nice to get some social gatherings happening via the rest of my ongoing family as well? it has been years since we've done something like that).

It was a surreal experience, as one might imagine, but I attempted to be in the moment as much as possible, and not overthink the whole thing. Cousins! So many cousins! (although perhaps it would be nice to get some social gatherings happening via the rest of my ongoing family as well? it has been years since we've done something like that).Adams: descended from Dr. Samuel Adams, UEL (which means, also, that Ottawa writer Miller (formerly Sylvia) Adams, who ran The TREE Reading Series before I did, and was even a neighbour during the early 1990s, is a distant relative, which is pretty cool).

Oh, and you caught the t-shirt I made for the event, yes? I had to make an entrance, after all.

August 13, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nick Voro

A native of Kyiv, Ukraine, but living in Canada since the age of eleven,

Nick Voro

discovered literature at an early age, never quite mustering the ability to put an excellent book down. A recent graduate of the Toronto Film School, Nick divides his time between being a full-time parent and a full-time author.

A native of Kyiv, Ukraine, but living in Canada since the age of eleven,

Nick Voro

discovered literature at an early age, never quite mustering the ability to put an excellent book down. A recent graduate of the Toronto Film School, Nick divides his time between being a full-time parent and a full-time author.His debut work, Conversational Therapy: Stories and Plays , is available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble and Chapters Indigo. The work has recently sold over 100 copies and is part of the library system (Toronto and South Australia).

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Publishing my first work allowed confidence to enter my artistic life. Confidence which I did not possess for more years than I care to mention. I was terrified. Critics, criticism, negative reviews… This has been a journey. Which ended in monumental mental step-taking. I got here a little later than I wanted, but I regret nothing.

My recent work, Conversational Therapy: Stories and Plays, truly has a therapeutic quality for me. It compiled stories I have written around 2006-2008 and plays I wrote in 2014-2016 around the time I attended the Toronto Film School. Some plays were actually short films originally. I’ve included what I thought was the strongest, re-wrote plenty and edited the whole thing with my dear friend and mentor Lee D. Thompson, who also happens to be a fantastic writer.

This collection is a step forward. A step in the right direction, and it pays homage to what I did in my twenties with a polish, maturity and confidence I’ve gained in my thirties. This won’t be my strongest or most memorable work, but it is brave, innovative and deliciously experimental. Personally, I think that’s worth something.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Both of my parents were strong readers who wrote poetry in their twenties but discontinued their poetry writing as time passed. I am in possession of some of my mother’s poems, which I hope with her permission and blessing to translate and release one day. That being said, since a very early age, I have always gravitated toward fiction. With age, I am not inflexible in this stance. I welcome both poetry and non-fiction, but fiction is where my heart and soul find solace.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I must confess that I am a slow writer. I still haven’t achieved the work ethic required daily of writers for the best results possible. I always seek that which is impossible in writing—perfection. Obsessiveness, rewriting, seeking perfect words to use. In the end, what I am left with won’t change too drastically. When I perfect something at the very start, I find I won’t need to resort to heavy editing. Editing will transpire, polishing will happen and even some re-writing. But I would say that my pace and my approach to my work are usually rather close to my final vision.

4 - Where does a work of prose or a play usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?

I used to think of myself as a short story writer and a scriptwriter for many years. Forever stuck with a dream of writing longer and more important work. The importance of length mindset soon disappeared, disproven rather quickly once I read short stories by Jorge Luis Borges and Vladimir Nabokov. I often champion short stories to people who prefer novels. I tell them often that what Borges could do in four pages is better than most novels. Short Stories are forever underrated and underappreciated. Bernard Malamud, Juan Rulfo, Clarice Lispector, Julio Cortázar, Raymond Carver, Flannery O’Connor, Bruno Schulz, to name a few masters of the short form. My current project is a novella tied to two or three short stories from my debut collection. And I hope to follow that up with a novel. But I will never renounce my love and admiration for short stories.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have yet to do one. Perhaps in the future. Canada was a very different place when I arrived here in 1998. I had to deal with many years of non-acceptance. My background was not accepted. My accent was not accepted. I was not accepted. When you feel like an outcast for so many years, it doesn’t exactly boost confidence for public speaking. But I am slowly getting over this bump and working toward making public appearances and certainly looking forward to eventually doing a reading.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

With this work, I largely set out to disprove notions about the mystery/crime/noir genres as being lesser. I tread where better writers than I have gone before, such as Vladimir Nabokov with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and Paul Auster with his New York Trilogy.

The premise of one story, The Train Ride, is, of course, an homage to the one and only Patricia Highsmith. Before Paul Auster cleverly reminded us how it is possible to elevate this genre, and truly break through presumptions about it, a path I’ve also tried to follow. There was Highsmith and her incredible psychologically dissecting thrillers with plenty of dark comedy. The genre is more than locked door mysteries. It is more than black gloves and silenced pistols. To use my own work as an example, I believe most readers understood what my intentions were and what I was trying to achieve here. I wasn’t actually writing serious crime mysteries or noir thrillers. There was always a toying with the genre, but always respectfully, there was also always the psychological aspect, beyond the dazzle of metafiction, experimentation and innovative trickery. At the heart of it all, I wanted to infuse a genre often looked down upon with the complexity and depth of literary fiction that far surpass it according to those same individuals until all lines and opinions are blurred. Did I fail? This isn’t for me to decide. That is for the reader. But for me, it’s never fascinating to write about a gun. What fascinates me is to write about a person holding the gun and firing it. The motivation behind their actions. Nor about the actual investigation, as much as about the person investigating it. Plenty of serious and great writers also dabbled with crime writing. Because there’s this allure. Impossible to ignore.

When my favourite novelist wrote a non-conventional detective novel, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight , I knew I was onto something. For many, that work isn’t in Nabokov’s top five, but I’d argue that it can easily be. And the amusing part, you don’t remember the investigation. The train tracks taken, or roads driven upon, or many of the twists and turns. You remember the discussions on memory, philosophy, things which we leave behind which we are remembered by (in this case photographs, diaries). You remember the characters which under masterful brushstrokes become real people, or do they? Since full understanding and true identity play an important role. But what is certain is that we learn about these characters more than what is generally expected by those critics of the genre. And therefore, the elevation has successfully occurred. The work is no longer just a thriller. It is a serious work of fiction that should be seriously considered. And are we not perhaps too rash at times, to compare, and to do so negatively? What would G. K. Chesterton, Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler, among so many others, have to say about this? Why do we need work like The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, The Lime Twig and The New York Trilogy to direct our attention to the fact that the walls separating these genres are rather thin and decrepit? Why must these in-between novels be written to make us question literary fiction elitist gatekeeping about what exactly classifies as a masterpiece and the criteria it has to fall under? The Lime Twig is a crime novel at heart. And I consider it to be brilliant for one.

7 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Hiring a professional editor was a learning experience full of growing pains. I learned plenty, and I am a different writer now who has a better understanding of ways to improve my work. There is a difference between a light edit and a more serious one. My editor became my friend and my mentor. What I will say is that no one is above therapy, and I don’t think anyone is above editing. This is my opinion, but I stick to it. I’ve met plenty of lovely individuals and talented writers who do not believe in professional editing, and they are fully entitled to their opinions. I respectfully disagree. Some writers are natural editors, some learn and reach a level where outside editors are not needed. But most of us require another set of eyes. Expertise of someone removed from our work. In the end, do whatever works for you. What works for me is working with editors like Lee D. Thompson.

8 - What is the best piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

To stop obsessing over trying to achieve perfectionism and flawlessness in my writing. To simply, just write.

9 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (plays to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I believe all writers have the ability to move between genres. Their level of success is to be determined. But if one can write, one can write anything. I began with short stories and continued with them until I experimented with screenplays. Largely, it is the recalibration of the brain in order to jump aboard another ship and set sail. Otherwise, it is all writing and writers surely know how to do this.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

There is no specific routine, but I do have to have my notebook when I am reading. I get inspired by reading great works of literature. Ideas come to me. Snippets of dialogue. Entire paragraphs if I am lucky. Writers cannot write without reading. The two go hand in hand.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I have been fortunate not to have dealt with writer’s block thus far. But to answer the question of where one seeks inspiration. I find it in outstanding books and unforgettable cinema. All I need to do is pick up a book by Vladimir Nabokov or watch a film by Ingmar Bergman. The online community for artists is also wonderful. My brief e-mail exchange with Joseph McElroy was truly inspiring. A brilliant novelist who took all sorts of literary risks and deserves more recognition.

All one has to do is to keep going. If I stopped writing, I would stop living.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I would love to answer this question with Proustian prose. Alas, I am unable. My first home is under attack. When I think of my home, I do so with tears in my eyes. But Ukraine will survive.

13 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Vladimir Nabokov, Don DeLillo, Joseph McElroy, Thomas Bernhard, László Krasznahorkai, Franz Kafka, Machado de Assis and a few others I’ve mentioned elsewhere in this lovely interview. I would also encourage readers of this interview to sample the work of some really great Canadian authors, like Lee D. Thompson, Jeff Bursey, W.D. Clarke and Braden Matthew.

14 - What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?

To write a novel.

15 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Writing, sadly, does not pay the bills for most of us. I work. I support my family. Do I enjoy this non-artistic type of work? No. Would there be a great difference if it were something else but still a distance away from art? The answer would be a firm No once again. Most of us dream the same dream. Perhaps one day that dream will become a reality. And we can do only the type of work we truly want to be doing.

16 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Impossible to answer. I was doing it from such an early age. It is part of my identity at this point. A separation is inconceivable. I write. I am a writer. And I will continue to create until I am unable.

17 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Books: Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk. Satantango/Chasing Homer/The Last Wolf/Spadework for a Palace by László Krasznahorkai.

Films: Ruben Östlund’s The Triangle of Sadness.

18 - What are you currently working on?

A novella which will take me out of my comfort zone. Challenging everything I have learned about writing up to now and making me try different styles to go along with the highly experimental nature of this work. Which is: Psychological, philosophical, poetic.

This novella revolves around the journey of a woman seeking meaning and understanding. Her life at the moment is incomprehensible, her partner is missing, and she is all alone. A mysterious phone call in the middle of the night sets things in motion, and so begins a deeply rich psychological analysis of a character trying to adjust to her newfound situation.

Silence plays a significant role in one chapter. Almost becomes the protagonist. Another chapter brings us inside of a book which was abandoned on a nightstand by the main heroine. And yet another chapter focuses on a philosophical discourse on life and death between the said heroine and a ruthless hitman inside of a motel which seems to be suspended between worlds.

A splintered narrative, a remarkable tale of humaneness, a breaking down of our deeply embedded beliefs, the ignited gunpowder of originality. An honest look at human fragility, the tenderness and vulnerability. Masked faces unmasked. An examination of our routines, our societal performances, stationary existences, medievalism of our belief in predestination. A written concernment with everything that makes us human. Humanity transcribed onto the page.

I really want this work to cause a revolutionary reaction. I want any preconceived opinions or expectations of a work of fiction from Canada to go out the window. While this pays homage to the past, it is also very much the next stage of Canadian Literature. Unafraid to take any plunge. Deterministic to undermine all preconceptions.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;