Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 81

August 11, 2023

Thirteen ways of looking (in-progress,

, after RobertKroetsch

1.

A blackbird, thus. A lemon.Glacier. A mass of scatter, heart. The scent of that, green. Christine fillsthe sunroom with tomatoes, garlic, sunflower seeds. She pulls at the lettuce. Isit the distance that separates. Rose, mutters. Underneath her breath. Christine’spotted lemon tree. A bale of straw in the trunk of the car. For the garlic, shesays. To plant the garlic.

You hear the sun. Whenlight is not your friend. This bite, is melancholy.

When they have senses. Anotherwheelbarrow of dirt. Another broken wheelbarrow. Rhythm: an elusive quality. Whattwo are opposite. The children walk on sound.

The differences of smallhands. The differences of hands, without which there is no poem.

I have an abidinginterest. My father carried around such years. His father, before him.

2.

Whether,red. These green tomatoes: a double reference. Whenever speech an act.

AsI continue to expand. What I could not, for the writing of it.

Howthis is not my book.

3.

Thisblackbird, lemon. As I wander, thoughts. A frame supports the language.

Christineprepares the garden. She separates out, what is familiar. I haul out awheelbarrow of topsoil. I haul out a wheelbarrow of topsoil. I haul out awheelbarrow of topsoil. A cubic yard. I empty the bag from our driveway.

Togarden, which might be a form of translation. Aoife, her twice-weekly Germanclass. She responds to her sister: nein.

Someoneis chewing a bone in my rib cage. Aurora Borealis. What memory is.

CraigSantos Perez: It was summer all winter. What we know, for the writing of it. Forthe looking.

4.

Asheer of frost. The morning, withers. Children vacillate: breakfast, clothes.

Morning:the first and last daily capture during which I self-orient. A form, we lack. Scribblenotes in my notebook, this notepad, this postcard. Even the dishwasher grumbles.

Forestschool: Aoife names her newly-acquired stick “red crayon.” Once home, shemarkers the point black, not red. Is this not a pipe.

Letus skip across categories, the ideal situation. An ordinary day, persists. The lovesongs of Nancy Sinatra, Lizzo. Everyone on television has such good teeth.

Ihave lost my ability to count.

5.

Ifsomeone asked me: How are sketches shaped? How is a lemon? How might an hour?

Theyoung ladies’ e-learnings present themselves in packets. One ninety-minutesession. A wee break, there.

Onemoves beyond the iron element.

Christineleft the house today at 9am. She will return around dinnertime. One thought leadingdirectly and immediately into another. With a clean edge.

Myflippant response to a Twitter question: What prompts you to write?

I answered: Fear of death.

(October 2021-

August 10, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Eugenia Leigh

Eugenia Leigh is aKorean American poet and the author of two poetry collections, Bianca (FourWay Books, 2023) and

Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows

(Four Way Books,2014), winner of the Late-Night Library's Debut-litzer Prize in Poetry selectedby Arisa White, as well as a finalist for both the National Poetry Series andthe Yale Series of Younger Poets. Poems from Bianca received Poetry magazine’sBess Hokin Prize and have appeared in numerous publications including TheAtlantic, The Nation, Ploughshares, and the Best of the Netanthology. Her essays have appeared in TIME, The Rumpus, andelsewhere. Eugenia received her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and serves as aPoetry Editor at

The Adroit Journal

and as the Valentines Editor at

Honey Literary

.

Eugenia Leigh is aKorean American poet and the author of two poetry collections, Bianca (FourWay Books, 2023) and

Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows

(Four Way Books,2014), winner of the Late-Night Library's Debut-litzer Prize in Poetry selectedby Arisa White, as well as a finalist for both the National Poetry Series andthe Yale Series of Younger Poets. Poems from Bianca received Poetry magazine’sBess Hokin Prize and have appeared in numerous publications including TheAtlantic, The Nation, Ploughshares, and the Best of the Netanthology. Her essays have appeared in TIME, The Rumpus, andelsewhere. Eugenia received her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and serves as aPoetry Editor at

The Adroit Journal

and as the Valentines Editor at

Honey Literary

.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My firstbook, Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows, and my recent collection, Bianca,were published nine years apart, and like any siblings, they are both similarand vastly different from each other. They share the narrative of childhoodabuse, domestic violence, and parental incarceration, but my first book engagesthe subject from the perspective of a young adult child who processes thatworld with more surreal language, more imagination, more experimentation on thepage.

Bianca was written after Ibecame a mother and after I was diagnosed with both CPTSD and bipolar II disorder—experiencesthat gave me access to a much-delayed rage and much-needed vocabulary that ledto shattering clarity about my past. One goal for this book was to convey thatclarity through my poems.

If Blood,Sparrows and Sparrows changed my life, it was maybe because that book gaveme permission to identify myself as a poet. I felt I’d earned that label, whichmy father continued to reject. It was also the book that taught me toprioritize myself, as its launch came with a difficult decision to estrangemyself from my father and his side of the family.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

Idabbled in all genres as a child and as a teenage writer, but I took severalpoetry workshops in college at UCLA, where I was fortunate enough to work withHarryette Mullen, Joy Harjo, and Stephen Yenser. I only applied to poetryworkshops because the creative writing concentration was my only way out oftaking difficult literature classes I wanted to avoid as an English major. Inaddition to working almost full-time while in school, I was also dealing with alot of real-time trauma involving my father who had just left years of prisonvia deportation, and writing poems sounded more manageable than writingmulti-page papers about Chaucer or Milton.

Twoyears after college, when I decided to shoot for an MFA, I initially planned tostudy fiction because I was enamored with Salvador Plascencia’s The Peopleof Paper. If I’m being honest, I was probably also acutely aware that poetsdidn’t make money (and had a misguided understanding of what novelists made —ha!). Having grown up in poverty for much of my childhood, and then in theworking class, I couldn’t imagine taking out graduate school loans to follow apassion with no real hope of an income down the road.

But oneof my former literature professors, Karen E. Rowe, hesitated to write a letterof recommendation for fiction and reminded me that I was a poet, that my bestwork was in poetry, and that I should follow that path. I trusted her—and Ialso found that working on a poetry manuscript came much easier to me than afiction manuscript—so I listened to that advice, and here I am. I do write andhave published essays, and one of those essays appears at the center of Bianca,but time will tell whether I have an entire book of prose in me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

My firstdrafts often look nothing like my final drafts. It takes me forever to write apoem draft, and then I revise maniacally before I feel comfortable sending apoem out for publication. I also often abandon poem drafts for months beforereturning to them with fresh eyes. I simply don’t trust my early drafts and mustcreate distance before I can revise them. To give you an idea: one of my poemsin Bianca began when I was single and child-free, and the final draftcontains an anecdote about my husband and son.

Essayscome a bit faster, but I do take notes for months before I begin writing adraft. I usually come to the blank page with pages of notes and then figure outhow to puzzle the pieces together. Essays are like collages to me. I approachpoems with more faith and wait for revelations.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I haveyet to write toward a book project idea, though working on a “project” soundslike a fun dream that I’d love to try. Both of my books began with individual,disparate poems that, at some point, began to speak to each other until itoccurred to me that I had a book. This usually happens at the point when I haveabout 60-75% of the poems required for a book, and then I’ll write theremaining poems with that book in mind. It’s usually the poems I write towardthe end with the book in mind that wind up being my favorite, most “impressive”pieces. Maybe that’s my sign to attempt a book project after all.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Oh, Iabsolutely love giving readings. I write poems to connect with people, to givevoice to the ugly experiences we don’t typically advertise. I write to silenceshame, and I think there’s incredible power in speaking out these kinds ofpoems, especially in community. When I first started writing poems, I alsobecame an avid fan of spoken word poetry thanks to my former poet roommate, sothat’s also part of the literary history I’ve long studied and admired. And ofcourse, before printed books existed, the earliest poets were rooted in theoral tradition.

There’san art to bringing a poem to life onstage. To ensure every word is heard, everyemotion is felt. I practice my sets in front of the mirror, record them overand over, the whole nine yards, but I still get nervous sometimes maybe becauseI put so much weight on what a reading can achieve. A public reading is aunique chance to create authentic emotional intimacy with complete strangers(or friends) face-to-face for 10 to 30 minutes with minimal distractions. Intoday’s Internet culture, that kind of interaction is pure gold.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I wanteverything I write to take a risk. Whether in content or in its artistry. Thequestion I am writing toward is one Laure-Anne Bosselaar taught me to ask: whydid this poem have to be written? Why couldn’t the poet remain silent?I’m also constantly conscious of how for many of us, myself included, “poetryis not a luxury,” as Audre Lorde famously wrote. How do I make that clear onthe page? After a book is written, I ask myself, what risks can I take nextthat I haven’t yet dared to take?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

“Therole of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.” — Toni Cade Bambara

“Perhapspoetry is another of science’s deepest roots: the capacity to see beyond thevisible.” — Carlo Rovelli

“I’m notasking you to describe the rain falling the night the archangel arrived; I’mdemanding that you get me wet. Make up your mind, Mr. Writer, and for once inyour life be the flower that smells rather than the chronicler of the aroma.” —Eduardo Galeano

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential!Painful to the ego maybe, but essential. A good editor can see what you’retrying to accomplish and help you get there more efficiently. They can alsocall out your weaknesses that are hard to spot when you’ve looked at yourmanuscript a thousand times. One of my absolute favorite things about Four WayBooks is the way they graciously and meticulously provide edits for our books. Twoeditors went through my manuscript to offer detailed feedback that I was freeto accept or reject. The first note I got for Bianca was that I used theword “rage” way too many times throughout the manuscript. It deadened theeffect and sometimes didn’t leave room for actual rage to simply existwithout having to announce itself. I took out a bunch of rages and left aselect few where necessary, but I absolutely loved that they caught this. LikeI said earlier, I don’t trust my own writing, so I’m generally eager for feedbackfrom editors I trust.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

MarieHowe told a graduate workshop I took to “write as if everyone you love isdead.” Don’t think about other people’s reactions to your work. Just get it alldown. Kimiko Hahn said the same to me years later at a Kundiman retreat. Don’tbring your fears to the table when you write. Write everything that comes toyou. Then later, once it’s written, you can evaluate each piece and ask whetheryou’re comfortable with publishing it. Writing and publishing are two separatebeasts. Don’t let the idea of publishing limit your writing.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I beganwriting poems during the heyday of Xanga and Blogger, where I wassimultaneously writing blogs that read as very casual essays. So both energieshave always existed in my writing. When I took a nonfiction workshop with Luis Alberto Urrea during my one year I attempted a PhD program, I thought I wouldlearn to write essays, but I came out realizing that I already knew how—atleast in one way. Of course, there are a myriad other ways I still have yet tolearn. But it’s only now that I’m learning some editors will actually publishmy essays, too.

At therisk of making a gross generalization, I’d say prose is better able than poetryto cushion saccharine emotion or cliché—the kinds of events that make usbelieve in angels or happy endings. It’s harder to take a spoonful of sugarstraight versus drinking a spoonful of sugar stirred into a glass of water. Youcan sneak sweetness into prose or maybe also into a longer narrative poembecause there is more space to contain a wide range of human experience tojustify belief in something so cloyingly romantic. I say this as a cynic. Somepeople write happy poems all the time and manage to convince us of them. But Ineed space to break a heart before I can mend it. And poetry can do that to anextent, but prose can really hit you in the gut with it because you’re forcedto stay with it longer and go on a longer rollercoaster ride with the characters.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’thave a solid writing routine, which I hate. So I recently reached out to threewriter friends I admire who work their asses off and asked them to keep meaccountable to writing at least one line every day before I turn 40 next year.I started out trying to write a “real” poem draft each day and burned myselfout after two days, and thanks to some advice from one of those friends, I nowwrite a few lines in my notes app on days when I can’t get to a desk.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Sciencearticles. Novels. Poetry books that do something I have not yet done or maybewant to do. Instagram memes. Old journals. Old text messages. Anything withinreach really.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Muskreminds me of being trapped in an unairconditioned car in the Chicago heat onthe way to church with my parents as a child. To this day, I get nauseated whenI get a whiff of a perfume or cologne that contains musk. I can’t stand it.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Alright,I’ll be very honest and admit emo song lyrics heavily influenced my first book,which I wrote in my twenties. I’ve also stolen bits of revelation from pastsermons. After my first book, during a spell when I was clinically depressed fora couple of years, I was hardly writing and hardly reading, so I subscribed to TheScientific American, which later inspired two poems in Bianca. Ithink it’s safe to say my therapy appointments have also heavily influencedthis recent book. Also, a very accessible book called The Order of Timeby Italian theoretical physicist, Carlo Rovelli.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Thebooks I turned to over and over as I wrote Bianca were Hybrida byTina Chang, The Undertaker’s Daughter by Toi Derricotte, and StillLife with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl by Diane Seuss, all of Marie Howe’s books, among many others.

Thereare a number of writers whose voices I hear lately—whose conversations Iremember—when my internal critic gets loud, and I need to remember who I am.These are the writers whose genuine encouragement and support for Bianca havetruly buoyed me during this past year: Hanif Abdurraqib, Mahogany L. Browne, Jennifer S. Cheng, Su Cho, Victoria Cho, Noah Arhm Choi, Jessica Cuello, Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach, Danielle DeTiberus, Linda Harris Dolan, Tarfia Faizullah, Joan Kwon Glass, Sarah Kain Gutowski, K. Iver, Keetje Kuipers, Jason Koo, Iris Law, Hannah Matheson, Rita Mookerjee, Cassie Mannes Murray, Patrick Rosal, Brenda Shaughnessy, R.A. Villanueva, and Keith S. Wilson. I also feel way less alonein my neuroses and in all things poetry when I talk to poets Janine Joseph,Sophie Klahr, and Brenna Womer because they have the best sense of dark humor.

16 – What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?

I’d liketo see the Northern Lights.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

Thereare multiple alternate versions of me I’ve thought through in a lot of detail. Iloved fashion as a teenager and used to make some of my own clothes and pursespartly because my mom made a lot of our clothes when my sisters and I were verysmall. Some of my happiest memories involve the fabric store. I designed my ownprom dress when I was a high school junior, which my mom sewed for me. So inone reality, I am probably a fashion designer.

Inanother universe, I probably became an extreme version of my corporate self.For several years after my MFA, I worked as an executive assistant to c-levelexecutives in NYC finance firms. At the last of those jobs, at a fintechstart-up attached to a large hedge fund, I had to hire four people to replaceme. I got a big kick out of being able to be efficient, smart, and necessary inthese big money-churning machines. Most days, I consider myself ananticapitalist, but sometimes I think I could have become the most annoyingspokesperson for capitalism if things had turned out a different way.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

A largepart of it was that I had many creative interests as a child, but my parentshad no money to pay for dance lessons or voice lessons or art classes or evenbasic materials. All I wanted as a kid was one of those 96-crayon Crayola boxeswith the built-in sharpener and every shade of red with their delicious names.I turned to writing because I didn’t need lessons or materials other than apiece of paper, a pencil, and my imagination to make a story.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Book:Vievee Francis’s The Shared World. Film: Kill Boksoon on Netflix.

20 – What are you currently working on?

Hahahahahahahahahah *ignores thisquestion & shares a meme on Instagram*

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 9, 2023

Spotlight series #88 : Dessa Bayrock

The eighty-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet Dessa Bayrock.

The eighty-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet Dessa Bayrock.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win and Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik.

The whole series can be found online here.

August 8, 2023

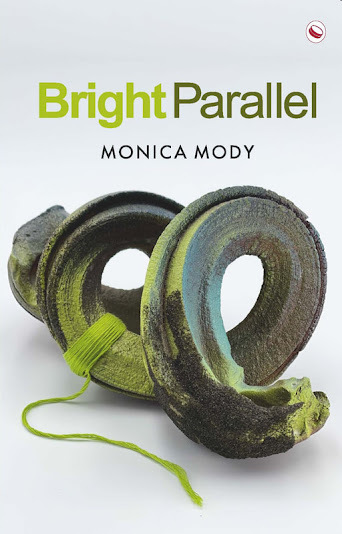

Monica Mody, Bright Parallel

In the beginning of time,a poet lived with family. Family loved and cossetted her, kept her away fromhousework + farmwork + roadwork.

She kept letters dancingbefore her eyes. She with letters festooned on bedpost. She with skin laid outon bed.

In the beginning of time,poet knew not what to remember but paid attention to the call of time. Timesang arias to her. She sobbed. Large-fingered, time folded her like a rag. Timelet her see.

In the beginning of time,when nothing lived but stark winds too eerie to see a small figure—running andrunning—

When she fell down,someone reached out and picked her up.

There I floated, there I lay,before the mouth of time. Retched. (“Fundamental”)

Thesecond full-length collection by San Francisco-based poet, theorist and educator Monica Mody, following

Kala Pani

(1913 Press), is

Bright Parallel

(Delhi India: Copper Coin, 2023), a suite of interconnected first-person lyricstriations and sentences. Her poems, ranging from the contained to a moreextended lyric, explore and examine with such an intensity and detail of interiority.“i want this house of cards to be / shelter,” she writes, as part of the poem “shadown.”Her poems offer a kind of swirl, a sweep of prose poem lyric set as breath, inhaled,inhaled and held. “on tip of your feather, tip of your wing,” she writes, toopen the poem “Wild—,” “soaring familiar as bones / cracking open to curve ofdance that bends // what spills from your eyes to its own rage, endemic / ache,deep into memory that lives in your muscles, [.]”Hers is a book of explorationand examination, of seeking; simultaneously responding to and reporting on theworld as it occurs from a singular point, occasionally rippling out, into familyand deeper elements of community. “The poems were written across multiplecontexts of solitude and community,” she offers, as part of her “Acknowledgements”at the end of the collection. Through Bright Parallel, Mody worksthrough lyric and the lyric sentence to work through uncertainty and into clarityand beauty. Or, as she writes as part of the extended “How We Emerge”:

Thesecond full-length collection by San Francisco-based poet, theorist and educator Monica Mody, following

Kala Pani

(1913 Press), is

Bright Parallel

(Delhi India: Copper Coin, 2023), a suite of interconnected first-person lyricstriations and sentences. Her poems, ranging from the contained to a moreextended lyric, explore and examine with such an intensity and detail of interiority.“i want this house of cards to be / shelter,” she writes, as part of the poem “shadown.”Her poems offer a kind of swirl, a sweep of prose poem lyric set as breath, inhaled,inhaled and held. “on tip of your feather, tip of your wing,” she writes, toopen the poem “Wild—,” “soaring familiar as bones / cracking open to curve ofdance that bends // what spills from your eyes to its own rage, endemic / ache,deep into memory that lives in your muscles, [.]”Hers is a book of explorationand examination, of seeking; simultaneously responding to and reporting on theworld as it occurs from a singular point, occasionally rippling out, into familyand deeper elements of community. “The poems were written across multiplecontexts of solitude and community,” she offers, as part of her “Acknowledgements”at the end of the collection. Through Bright Parallel, Mody worksthrough lyric and the lyric sentence to work through uncertainty and into clarityand beauty. Or, as she writes as part of the extended “How We Emerge”:We who tell the story

still live

What is remembered lives

This body remembers

August 7, 2023

reminder : rob's clever substack,

Youprobably already know, but

I’ve been working a substack for a while

, aiming topost once a week or so. I started last fall, working on a book-length essayaround literary community, responsibility and other considerations ("Lecture for an Empty Room"), and wasalso interspersing a variety of short stories, as well as a lengthy essay I hadworked on my collaboration with Denver poet Julie Carr (there was a lengthyabove/ground press essay I slipped in there as well). I figured the weekly-ishprompt would push me to further work into potential book-length thinking, akinto the burst of one hundred days that became

essays in the face of uncertainties

(Mansfield Press, 2022). While I attempt to only include apaid post every third or fourth time (I can’t help but keep much of it open,not wishing to exclude readers), there are options to pay monthly or annuallyetcetera. I’m pretending it’s a trickle of income, but we shall see where itgoes.

Youprobably already know, but

I’ve been working a substack for a while

, aiming topost once a week or so. I started last fall, working on a book-length essayaround literary community, responsibility and other considerations ("Lecture for an Empty Room"), and wasalso interspersing a variety of short stories, as well as a lengthy essay I hadworked on my collaboration with Denver poet Julie Carr (there was a lengthyabove/ground press essay I slipped in there as well). I figured the weekly-ishprompt would push me to further work into potential book-length thinking, akinto the burst of one hundred days that became

essays in the face of uncertainties

(Mansfield Press, 2022). While I attempt to only include apaid post every third or fourth time (I can’t help but keep much of it open,not wishing to exclude readers), there are options to pay monthly or annuallyetcetera. I’m pretending it’s a trickle of income, but we shall see where itgoes.Whileour big ridiculous driving drip (and now the mound of work required up to the above/ground press anniversary event this Saturday) has knocked me a bit out ofmy momentum, I have been working on the beginnings of a further book on genealogy,given I’ve been learning further details on the new biological threads of mygenealogy. There are some interesting places I’ve been going on this thing, butthe sections aren’t quite ready for publication yet, but hoping soon. Genealogyis something curious: most of us care only as much or as little as we wish, andsome of these connections are so tenuous: what does it all mean, and whatshould it mean?

August 6, 2023

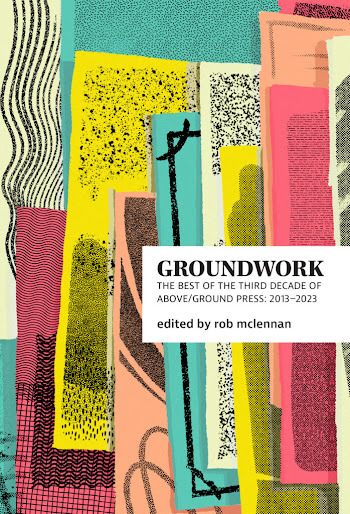

pre-order! groundwork: The best of the third decade of above/ground press: 2013–2023 (Invisible Publishing,

Celebrating thirty years of continuous activity with well over twelve hundred publications to date, groundwork celebrates the third decade of rob mclennan’s Ottawa-based above/ground press, publisher of lyric, innovative, and experimental writing across a wealth of chapbooks, broadsides and multiple simultaneous journals, including Touch the Donkey, The Peter F. Yacht Club and G U E S T [a journal of guest editors]. Following on the heels of the anthologies GROUNDSWELL, best of above/ground press, 1993-2003 (Broken Jaw Press, 2003) and Ground Rules: the Best of the second decade of above/ground press 2003-2013 (Chaudiere Books, 2013), groundwork pushes against the short-lived and the ephemeral of small and micro press publishing. Firmly situated in his home base of Ottawa, above/ground press revels in the possibility of expansive conversations between writers, writing and readership, and groundwork works to acknowledge mclennan’s deep and ongoing dedication to the work of hundreds of contemporary writers across North America and beyond. See link here to pre-order!

Contributors:

Jordan AbelJennifer Baker

Gregory Betts

Alice Burdick

Allison Cardon

Kimberly Campanello

Norma Cole

Julia Drescher

Kristjana Gunnars

Natalie Hanna

Brenda Iijima

Emily Izsak

N.W. Lea

damian lopes

Natalie Lyalin

Rob Manery

rob mclennan

Christine McNair

Allyson Paty

Julia Polyck-O’Neill

Shazia Hafiz Ramji

Stuart Ross

Kate Siklosi

George Stanley

Hugh Thomas

Chris Turnbull

August 5, 2023

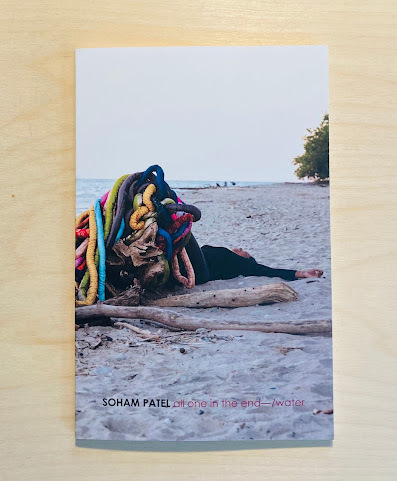

Soham Patel, all one in the end—/water

That September when I firstsaw Lake Michigan, I wanted it to be the sea. Inhales and I would pretend I couldtaste salt from the air in my nose.

In the many monthshundreds of articles twenty pounds three books all the injury and essaysmouthfuls and loves and songs there were births and murders and deathsdisasters storms and protests—and some semblance of home now every day when I seethis lake.

Like that cocooningsettle downhill into Manitou Springs in Colorado—closer to Pikes Peak’s whitecap of snow and closer to my apartment, another threshold, so far away from themegachurch and from the military bases where I worked—or Bloomfield intoFriendship neighborhood in Pittsburgh where the red house brick red house linethe avenue to school. (“ON LAKE MICHIGAN”)

I’vebeen eager to see further work from Soham Patel, rewarded this past weekthrough the publication of her third full-length collection all one in the end—/water (Fort Collins CO: Delete Press, 2023) [see my review of her first two full-length collections here]. one in the end—/water is a collectionthat is, in part, set as an intimate and book-length response via lyric to an array of poetsworking a blend of lyric, deep attention and ecological concern, including Lorine Niedecker, Brenda Iijima, Matthew Olzmann, Maggie Nelson, Dawn Lundy Martin andRonaldo V. Wilson. The title of the collection, for example, is directly borrowedfrom Niedecker’s poem “Paean to Place.” Blending lyric, line-breaks and prosepoems, Patel’s is a lyric attending the very consideration of being, and beingpresent, and the variety of perspectives and observations provide multipledirections upon the same sense of attending those moments. “Debris leftstanding is dead and so won’t be cut down for the humans’ safety so the powercompany says accordingly a fear I now hate but have conditions towards eachtree from the middle to the end of our easement where I warranty me to learnall we can about this here rooted lands we’ve just moved in.” (“EXACTNESS COMESWITH WIND GUSTS”).

I’vebeen eager to see further work from Soham Patel, rewarded this past weekthrough the publication of her third full-length collection all one in the end—/water (Fort Collins CO: Delete Press, 2023) [see my review of her first two full-length collections here]. one in the end—/water is a collectionthat is, in part, set as an intimate and book-length response via lyric to an array of poetsworking a blend of lyric, deep attention and ecological concern, including Lorine Niedecker, Brenda Iijima, Matthew Olzmann, Maggie Nelson, Dawn Lundy Martin andRonaldo V. Wilson. The title of the collection, for example, is directly borrowedfrom Niedecker’s poem “Paean to Place.” Blending lyric, line-breaks and prosepoems, Patel’s is a lyric attending the very consideration of being, and beingpresent, and the variety of perspectives and observations provide multipledirections upon the same sense of attending those moments. “Debris leftstanding is dead and so won’t be cut down for the humans’ safety so the powercompany says accordingly a fear I now hate but have conditions towards eachtree from the middle to the end of our easement where I warranty me to learnall we can about this here rooted lands we’ve just moved in.” (“EXACTNESS COMESWITH WIND GUSTS”).Patelwrites colours and waves and lights across the ether. Writing on place names andancestors, rain and what it uncovers, these are poems around a singular senseof geography that just as much explore how writing is thought and composed. Aspart of the poem “ON LAKE MICHIGAN,” she writes: “Matthew’s poems about shipwrecksin the great lakes lists fish and it all makes me so thirsty.” This is clearly abook composed in conversation, and in response, and there is something startlingin this approach centred in a poetics of Niedecker and Iijima (the book is dedicatedto Iijima), of space and rock and ecological concerns. Something startling, I suppose,in how clear-minded the poems read, amid, or even through, such polyvocabulary.It is interesting to think, as well, of this collection, as Patel offers in anote at the end of the collection, as “reassemblages from the previouslypublished chapbooks,” blending previously-published material into an entirelycoherent book-length form. There is such deep, abiding care through herattention. “Once I found a shiny layered rock on // Brighton Beach in the sand,”she writes, as part of “LISTEN IT’S MY DAY OFF,” “All over the darkness is realthough // And oil fueled the plane not a boat [.]”

LIKE SNOW IN THE SUN IWANT TO S(T)AY. Opaque and at arm’s length with screens and the satellites,how this new word we learned, beautiful, is so. We are a dangerous thing,candles uttering against trees. We are dismantling from within under&uncommonand yet here to illuminate or else we’ll correct or uncover. Our light awaitswarm and burn. It means renewal.

August 4, 2023

Natalie Rice, Scorch

ARROW-LEAVED BALSAM ROOT

FLOWER

splits the hillside.

Your arms are crossed, “maybeI’m not

your flower,” you say.Your mouth closes,

mine opens. But JohnThompson

leaps between his woman’sarms and blood,

and the moon, themoon, the moon. Was I

the one who put thoseyellow flowers on

our sill? I walk the yellow-green

pond. A heron slips aperfect leg

into the water, moveslike a dream I had

and forgot, of someoneturning towards me,

arms wide open.

I’mvery pleased to engage with the carved hush of Kelowna, British Columbia poet Natalie Rice’s full-length debut,

Scorch

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2023),a book I’d been looking forward to for some time. She had a chapbook with Gaspereau in 2020 [see my review of such here] and I was immediately struck bythe clarity of her lyrics, offering a sequence of sketches that are simultaneouslyeasygoing and lyrically taut. “[…] everything is the shape / of what you love.”she writes, to close the poem “APPLES.” Across an assemblage of honed lyrics,Rice offers a way of seeing between and among the trees, able to articulateecological space and time and our place within and surrounding it, articulatingjust how intimately connected and interconnected we truly are. As the sequence “LOSTLAKE” begins: “A jagged breath. Sometimes stars / peel off the pond.

I’mvery pleased to engage with the carved hush of Kelowna, British Columbia poet Natalie Rice’s full-length debut,

Scorch

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2023),a book I’d been looking forward to for some time. She had a chapbook with Gaspereau in 2020 [see my review of such here] and I was immediately struck bythe clarity of her lyrics, offering a sequence of sketches that are simultaneouslyeasygoing and lyrically taut. “[…] everything is the shape / of what you love.”she writes, to close the poem “APPLES.” Across an assemblage of honed lyrics,Rice offers a way of seeing between and among the trees, able to articulateecological space and time and our place within and surrounding it, articulatingjust how intimately connected and interconnected we truly are. As the sequence “LOSTLAKE” begins: “A jagged breath. Sometimes stars / peel off the pond.August 3, 2023

new from above/ground press: Massey, mclennan, Melançon, Hilder, Bowering/Gold, Stearne, Vogler, Gorin, Drescher, Norris, Donato, Pirie + Touch the Donkey #38

SONGS FROM THE DEMENTIA SUITCASE, Karen Massey $5 ; edgeless : letters, by rob mclennan $5 ; Bridges under the Water, by Jérôme Melançon $5 ; Where there's smoke, by Monty Reid $5 ; {NANCY} [an essay on Nancy Shaw], by Jamie Hilder $5 ; LALIQUE, by George Bowering and Artie Gold $5 ; Bits and Bobs, two stories by Ryan Stearne $5 ; Report from the (Pearl) Pirie Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; errand : towards, by Brad Vogler $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #38 $7 ; Simple Location, by Andrew Gorin $5 ; “Almost Alive” by Julia Drescher $5 ; ECHOES, by Ken Norris $5 ; Toothache, by Joseph Donato $5 ;

SONGS FROM THE DEMENTIA SUITCASE, Karen Massey $5 ; edgeless : letters, by rob mclennan $5 ; Bridges under the Water, by Jérôme Melançon $5 ; Where there's smoke, by Monty Reid $5 ; {NANCY} [an essay on Nancy Shaw], by Jamie Hilder $5 ; LALIQUE, by George Bowering and Artie Gold $5 ; Bits and Bobs, two stories by Ryan Stearne $5 ; Report from the (Pearl) Pirie Society, Vol. 1 No. 1 $7 ; errand : towards, by Brad Vogler $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #38 $7 ; Simple Location, by Andrew Gorin $5 ; “Almost Alive” by Julia Drescher $5 ; ECHOES, by Ken Norris $5 ; Toothache, by Joseph Donato $5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; see the previous batch of backlist here,

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

May-August 2023

as part of the above/ground press 30th anniversary

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

and don't forget THE ABOVE/GROUND PRESS 30TH ANNIVERSARY READING/LAUNCH/PARTY! Sat, Aug 12, 2023 : Clocktower Brew Pub, Glebe; celebrating THIRTY YEARS of continuous activity (and nearly thirteen hundred publications)

Forthcoming chapbooks by Colin Dardis, Sophia Magliocca, Russell Carisse, Micah Ballard, Cary Fagan, Jennifer Baker, Amanda Deutch, Kevin Stebner, Kyla Houbolt, Gary Barwin, Adriana Oniță, Noah Berlatsky, Heather Cadsby, Blunt Research Group, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Zane Koss, Peter Myers, Gil McElroy, Ben Robinson, Miranda Mellis, MLA Chernoff, Terri Witek, Geoffrey Olsen, Pete Smith, Robert van Vliet, Marita Dachsel, Grant Wilkins and Angela Caporaso (among others, most likely). And there’s totally still time to subscribe for 2023, by the way (backdating to January 1st, obviously).

August 2, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Laila Malik

Laila Malik is a desisporic settler and writer living in Adobigok, traditional landof Indigenous communities including the Anishinaabe, Seneca, MohawkHaudenosaunee, and Wendat. Her debut poetry collection, archipelago (Book*HugPress, 2023) has been described as haunting, tender and exquisite (SalmaHussain, Temz Review) and was named one of the CBC's Canadian poetrycollections to watch for in 2023. Her essays have been nominated for thePushcart Prize and Best of the Net anthology, longlisted for five differentcreative nonfiction and poetry contests, and widely published in Canadian andinternational literary journals. Malik has been awarded grants from the CanadaCouncil for the Arts and the Ontario Council for the Arts, and was a fellow atthe Banff Centre for Creative Arts for her novel-in-progress.

Laila Malik is a desisporic settler and writer living in Adobigok, traditional landof Indigenous communities including the Anishinaabe, Seneca, MohawkHaudenosaunee, and Wendat. Her debut poetry collection, archipelago (Book*HugPress, 2023) has been described as haunting, tender and exquisite (SalmaHussain, Temz Review) and was named one of the CBC's Canadian poetrycollections to watch for in 2023. Her essays have been nominated for thePushcart Prize and Best of the Net anthology, longlisted for five differentcreative nonfiction and poetry contests, and widely published in Canadian andinternational literary journals. Malik has been awarded grants from the CanadaCouncil for the Arts and the Ontario Council for the Arts, and was a fellow atthe Banff Centre for Creative Arts for her novel-in-progress.1 - How did your first book changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

My first book was avery slow, jigsaw process of building courage and coming to acceptance. I comefrom a people who are intensely private, and the prospect of publishing hasalways posed carried great risk to me and to us. I had to slowly come to termswith the idea of becoming more public, and think through ways to navigate alandscape that was foreign and riddled with real and perceived threat. But oneof the most wonderful results has been the opportunity to connect withindividuals who were just as starved as I had been for more complex diasporastories, and specifically voices from our hitherto unspoken experience as SouthAsians coming of age in the Arabian Gulf.

I still writepoetry after archipelago, but I havebeen trying the new challenge of novel-writing, which so far feelscomparatively slow and clumsy. I did a residency at Banff where a mentormentioned that it takes on average between four and six years to complete anovel, and that sounds about right. Add to that the daily needs of paying thebills and feeding the children, and who knows how much longer it might take?

2 - How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I was a high schoolmisfit in a place of impossible airlessness, skulking the dusty aisles of mylibrary to alleviate desperate boredom when I came upon two forms that changedmy life: poetry and plays. There was ee cummings and Eugene Ionesco, and thestrange speed and immediacy of poetry, alongside the radical but upside-down,inside-out approach of the theatre of the absurd in particular, split open myuniverse of possibility. I was stunned that this work was sitting casually anduntouched in the middle of an otherwise strictly guarded world. I began acorrespondence with another poetic rebel friend, and we compared notes on formand content, pushing one another to try new things with words on paper to speakto all things unspeakably sublime and grotesquely unbearable.

But it wasn’t untilI got to university and encountered the work of feminist, and especially Blackfeminist poets like Audre Lorde and June Jordan that I began to understandpoetry as innate and experiential to the lives of women and those who arerepeatedly kept out of institutions of power, a form that is fundamentallyrevolutionary and accessible. I could and did write poetry in hospitalhallways, in the mosque, at 3am while feeding a child, after a racist or sexistencounter at a supermarket, with a boss, with a government official. Poetrygleams from within the blood and visceral filth of the every day and so Iseized it quickly and greedily and eternally as mine, before anyone could tellme any different.

Finally, in 2017, Iwas selected to participate in a small, advanced poetry workshop withaward-winning poet and author Chelene Knight. Besides being a phenomenalwriter, Chelene has devoted her career to enabling writers to succeed andnavigate the publishing world with creative balance. The workshop was pivotalfor me in terms of deepening my craft, understanding the industry, and gainingenough confidence to take the next step. archipelagowas born of that process.

I did and do writefiction and non-fiction, but it requires a different kind of time andattention.

3 - How long does it take to startany particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or isit a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape,or does your work come out of copious notes?

My writerlythoughts initially come quickly, and most often in the place between sleep andconsciousness. It’s always a question of how persistent those thoughts are thatdetermine whether they make it to paper. Poems almost always get completed,seconded by essays. Fiction is a whole other ballgame and seems to engage anentirely different part of my brain.

4 - Where does a poem or work ofprose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

For me, poemsusually begin from an experience or observation, suffused with strong emotion,often emerging as snippets in my journaling. Essays begin when I’m wrestlingwith an incident or dynamic that has no name or precedent, and I’m compelled todocument and make sense of it. Fiction begins with a flirtation with outrageouspossibility – perhaps the reason I’ve yet to really fully explore that path.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

The prospect ofpublic readings used to fill me with the deepest dread but since publishing archipelago I’ve come to look forward toit – the opportunity to connect with readers and other writers is precious.People who were waiting for me to give name and life to experiences and didn’tquite know it, much as I have waited for other writers to do the same for me.I’m not sure how much it propels my creative process but it does remind me tostay in the room, and not to get too distracted by the drudgeries of life tocontinue the practice.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Certainly. I’mpreoccupied with the big ticket items – eco-collapse, spirituality, encountersbetween gender, imperialism and petty human power-mongering around identity,all from the perspectives of the specific groups of peoples from whom I draw mylineages and in the context of the most unprecedented migratory movement ourplanet has ever seen. I suppose my “the questions” are “Who are we becoming?What are we choosing? And what will be the outcomes?”

7 – What do you see the current roleof the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

After decades ofshirking that question for fear of sinking into hackneyed hubris, I’ve come to thinkthat the role of the writer is to provide relief to the reader by giving voiceto the complex vagaries and possibilities of existence. A window through whichto see and be seen, hence to feel fulfilled. In an essay I wrote for my latesister, I talk about seeing the CN tower on a prodigal return to Toronto, andhow it provided “a reassurance, corresponding with my earliest memory. Asingle, immovable constant, proof that we happened, my family and I.” Don’t weall want to be assured that we happened?

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It really dependson the editor. For the most part, I find it to be an incredibly rewarding,educational experience – almost all of the editors I’ve worked with have anincredible eye, and show me things I hadn’t seen. On the rare occasion I’veworked with a pedant, or an editor who is really not getting where I’m comingfrom or what I’m trying to do, and I’ve found it necessary to learn how to holdmy ground a bit. Overall I do find it to be an essential and extremely usefulpart of the process.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Keep writing.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I spent a long timein the academy, and work in communications, so I do tend to move betweendifferent types of writing frequently. My approach to essays, though, issteeped in poetry, so I haven’t found it difficult at all. On the other hand,there are some readers who have found it challenging. I’m thinking of aworkshop I did many years ago, in which the instructor, despite seeming toreally like my work, scratched her head at my meandering, sometimes rhythmic,alliterative and occasionally absurd sentences. But that’s my jam and I’m happywith it.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

In a perfect worldI would journal religiously. Life and its upkeep often keep me from this goal.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books, film, travel(when available), visits to desi neighbourhoods, family.

13 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Jasmine, thai basiland the salt scent of the Arabian Gulf at night.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above,but definitely nature, science and music. It’s been decades since I saw it, butthe Indian Ocean fires every one of my neurons.

15 - What other writers or writingsare important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many. When I wasyounger, I was so influenced by the humour and absurd possibility in TerryPratchett and Neil Gaiman’s works. More recently, my jaw was reset by AkwaekeEmezi’s Dear Senthuran. Ocean Vuong’sOn Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous tookmy breath away and reminded me, as did Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, that it is not impossible towrite a poetic novel beautifully and with solid, coherent, narrativearchitecture, and that this ultimately is what I want to achieve next.

16 - What would you like to do thatyou haven't yet done?

See above. I’mworking to achieve this with my novel-in-progress, Bitumen, but I have a long way to go.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I pay the billswith communications but I think it would have been deeply rewarding to be azoologist or a meteorologist, had I had more of a scientific brain.

18 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

The feeling of beingchronically, constantly, eternally silenced, and the irrepressible need to givevoice to the unspoken, the grotesque, the beautiful, the ludicrous, thepossible.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

Book: Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English.Film: Desi Standard Time Travel, anincredibly sweet, funny and poignant short by Kashif Pasta. I hope they bothget turned into feature films.

20 - What are you currently workingon?

I’m working on myfirst novel, which germinated twenty years ago in a very different world and avery different moment in my life. I’ve been trying to work out who it is now,and what it needs to say.

I’m alsocontemplating a book of essays, comprised of some of the work I’ve alreadypublished, alongside newer work. Thinking through narrative threads andconsidering publication options.