Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 85

July 2, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jenny Molberg

Jenny Molberg is theauthor of Marvels of the Invisible (winner of the Berkshire Prize,Tupelo Press, 2017), Refusal (LSU Press, 2020), and The Court of No Record (LSU Press, 2023). Her poems and essays have recently appeared orare forthcoming in Ploughshares, The Cincinnati Review, VIDA,The Missouri Review, The Rumpus, The Adroit Journal, OprahQuarterly, and other publications. She has received fellowships andscholarships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sewanee WritersConference, Vermont Studio Center, and the Longleaf Writers Conference. Havingearned her MFA from American University and her PhD from the University ofTexas, she is Associate Professor and Chair of Creative Writing at theUniversity of Central Missouri, where she edits Pleiades: Literature inContext. Find her online at jennymolberg.com or on Twitter at @jennymolberg.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When I was studying for my doctorate, I was honored to winTupelo Press’s Berkshire Prize for Marvels of the Invisible, my firstbook of poems. It changed my life in that the opportunity opened many doors forme—I was then qualified for teaching positions that required a published book(and thus was hired at my current position at the University of CentralMissouri), and the award gave me a sense of confidence in my work. I wasthrilled to join Tupelo Press’s catalog of incredible writers, and I was invitedto read from the collection at the AWP Conference in 2017. I am so grateful forthe award and the opportunities it led to. My first book was inspired by mydoctoral studies in historical connections between poetry and medicine; I waswriting about my mother’s breast cancer, but also did extensive research onmedical literature from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The bookinterrogates the ways in which gender norms negatively affected the progress ofscientific study, as well as my own experience as a woman dealing with medicalissues and loss. My more recent work is also research-driven, but through thelens of law. As a survivor of intimate partner abuse and assault, I wanted toconfront the ways victims are ignored or subjugated by the U.S. justice system,and looked to outside study to reflect on these issues.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

In a way, I came to poetry last—as a child and young adult,I was interested in journalism; I majored in journalism in college for twoyears, until I was fired from the university newspaper and switched my major tocreative writing. After declaring a creative writing major, I took primarilyfiction classes until my last year at the university, when I enrolled in myfirst poetry workshop. All genres of writing greatly interest me, and I’vewritten poetry, too, since I was a child; however, when my wonderful professorRandolph Thomas at LSU gave me permission to take myself seriously as a poet, Iknew that I had found my language. As someone particularly interested in musicand visual art, poetry seems to make most sense in my brain—the negative spaceon the page, the lyric, the associative nature of imagery. Dedicating my lifeto the study of poetry is the best decision I’ve ever made.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

I’ve learned to let myself off the hook a bit, in terms ofhow long a new project takes. The “thinking part” tends to take months, evenyears. I’ll become obsessed with a field of study or a concept and research,read, and take notes for a long time before I ever approach shaping thesethoughts into poems. I’ll fill notebooks and notebooks with ideas, quotations,images, sketches, etc. and then usually, one day, something clicks and I’mready to write poems. There are some poems that have taken me years to write,and some that have taken an hour. My mentor calls those poems that take an hour“poems from the future”—some future version of myself knew how the poem wentand it fell from the sky fully-formed. But I do think that those poems that arequick to appear are actually the product of a lot of thought and study, andmany failed drafts of other poems, as if the repeated failure finally gavebirth to a fleshed-out form.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think that depends—I write many poems that don’t end upin a book, as they’re not necessarily cohesive with a larger thought I might bewriting towards. I’ve often had the experience, too, where I write what I thinkis an essay, until I whittle it down to a poem. Some of my longer poems beganas essays. From the very beginning of a new line of thought, I don’t think I amworking on a “book” from the start, though I do have several title ideas andconcepts for books I’ve never written. I think it’s fun to come up with a bookidea, but usually the poems arrive in a shape I never expected, following aline of inquiry that almost shapes itself into a collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

What I love about readings is the connections I am able tomake with new people, especially when they relate personally to something Ihave written and I can see that they have been touched or inspired in some way.I still keep in touch with many people I’ve met at my own readings or thereadings of other poets. Also, though, I don’t know that I necessarily enjoyreadings, as I’m introverted—as a southerner and as a woman, I think I’vealways been well-trained to be sociable and outgoing, but being on a stage andthe social anxiety that comes along with readings can be draining. I haveencountered the work of so many poets I love because I first saw them read,too, so I believe community and sharing work is integral to the creativeprocess, especially considering poetry as a part of a larger dialogue.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I recently wrote a piece for the LSU blog where I exploredsome central questions of my most recent work. Here’s a brief excerpt thataddresses some of the central theoretical and craft questions I’m asking with TheCourt of No Record: “Whilewriting The Court of No Record… I found myself asking: When legal rhetoric ismanipulated to exhaust, damage, and financially and emotionally drain people,especially disenfranchised people, how can one reempower themselves withlanguage? How can one write about unfair legal proceedings without settingthemselves up for more?… Even though poetry, as Auden attested, “makes nothinghappen,” can it give evidence that will never be heard in a court of law? Canmetaphor, though it distorts, also serve and protect in a way the law fails todo?”

Here is a link to that post: https://blog.lsupress.org/metaphor-as-shelter-in-the-court-of-no-record/

The theoretical questions are always evolving,but my work has always been concerned with what it means to say the unsayable,what it means to live in a female body in the world, both politically and inliterary spaces, and how poetry can get to deeper truths in order to looktoward positive systemic change.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I think the writer has a responsibility to listen, toanalyze, to challenge, and to dream. Like scientists, writers must interrogatehistory and articulate the present in order to imagine a future that is more inclusive andopen to evolutions, both in language and in culture. Because words matter, and words last, I believe writershave an enormous responsibility to be empathetic, to challenge oppressivesystems of power, and to be open to new ways of seeing.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

For the most part, I find it essential and not difficult.My editors at LSU Press are fantastic, and I think they see my intentions andconcerns really clearly. I also have a few friends who are my trusted readers—Ithink it’s important to get others’ perspectives in order to fully beconsiderate of the reader.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

From my mom: “one thing at a time”. I say this to myselfnearly every day.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

As a professor and editor, it’s often difficult to keep aconsistent writing routine for myself—I typically find larger chunks of time inthe summer, or at a writers’ residency, to really dedicate to craft. I try towrite and read something every day, but I need long periods of time toreflect, read, and imagine in order to create more than little scratchings on apage.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like to visit my local museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, or read fiction, which always renews my sense ofimagination.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Sunscreen, gasoline, chili, fresh-cut grass.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Yes—I am heavily influenced by visual art, music, andscientific study, especially (but not limited to) works and studies thatprogress our thinking about restrictive binaries of gender.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are so many that it’s difficult to list.Writers I surrounded myself with while writing my most recent book include:Muriel Rukeyser, bell hooks, Maggie Nelson, Carolyn Forche, Natasha Trethewey,Vievee Francis, Shara McCallum, Anne Carson. Writers I’m always looking towardsas guides: David Keplinger, Kathryn Nuernberger, W.B. Yeats, Seamus Heaney,Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

There are things I’ve done that I would like to do more,like travel, campaign for causes I care about, and spend more time with my grandmother.I’ve always dreamed of going along on a scientific research expedition of somekind.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I always wanted to be a marine biologist. If I could do itall again, I think I would go to medical school.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I really think I have to write. No matter what myjob is, I’ll always be a writer. At one point, I was working four jobs, barelymaking rent, and then, as now, I don’t know who I would have been if I hadn’tbeen writing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan, The Galleons by Rick Barot.I just saw the film Orlando for the first time, and can’t stop thinkingabout it (1992, starring Tilda Swinton).

19 - What are you currently working on?

I have recently beenawarded a studio residency at the Charlotte Street Foundation in Kansas City,and I’m excited to embark on a project that blends poetry with visual art,working with visual artists in my cohort.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

July 1, 2023

last day(s) of school :

Aoife completed Grade 1 on Thursday, and Rose completed Grade 4 (achieving the 'honour roll' for citizenship, I'll have you know) the Wednesday prior. Do you remember, four or five years back, when I suggested their personalities could be boiled down into "casual" and "swagger"? Now that they're home, I suspect the next few weeks will be very busy.

Aoife completed Grade 1 on Thursday, and Rose completed Grade 4 (achieving the 'honour roll' for citizenship, I'll have you know) the Wednesday prior. Do you remember, four or five years back, when I suggested their personalities could be boiled down into "casual" and "swagger"? Now that they're home, I suspect the next few weeks will be very busy.

June 30, 2023

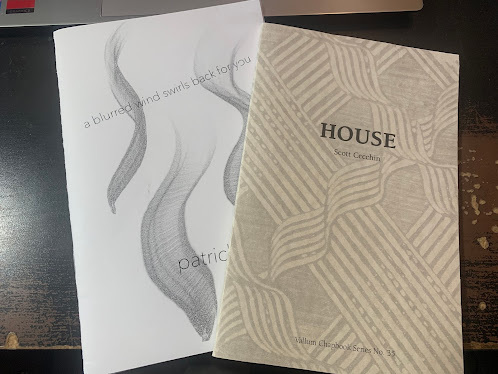

Ongoing notes: late June, 2023: Scott Cecchin + Patrick Grace,

Oddto think that my mother would have been eighty-three today; my father wouldhave been eighty-two this past Monday.

Oh, and don’t forget I have a substack, yes

? I think I’m gearing up for another book-length non-fiction project(possibly).

Oddto think that my mother would have been eighty-three today; my father wouldhave been eighty-two this past Monday.

Oh, and don’t forget I have a substack, yes

? I think I’m gearing up for another book-length non-fiction project(possibly).Montreal QC: A resident of Nogojiwanong/Peterborough, poet Scott Cecchin’s second chapbook is HOUSE (Montreal QC: Vallum Magazine/VallumChapbook Series No. 35, 2022), following Dusk at Table (O. Underworld!Press, 2020). I’m intrigued by the breaks, breaths and halts, the rhythms ofthis particular chapbook-length suite, and his poems expand upon their rhythmsas the poems progress. What I find most interesting is how and where he holdsthe small moments and fragments of speech, appearing far more compelling thanlater on in the collection, as his narratives stretch into more traditional andeven conventional plain-speech. But there is something here, and I amintrigued. As the opening title poem, “HOUSE,” reads:

The house flowers

in light. Be-

low that,

dirt. Deeper,

a glacier. And deepest:

fire.

Inside you, a moon. And

in the moon, somewhere, is

you. The sun gets inside every-

thing; and when the sun’s out

we are too.

*

The house, pressed

into the deep,

like a seed,

sinks. Look up:

air, so

many ships sinking up

there. Above that,

ice—and higher:

fire.

The earth

is shaped by fire andwater, while

water enters earth andair. The air,

sometimes, holds fire andwater,

and fire gives earth tothe air.

Montreal QC: One of the latest titles from James Hawes’ Turret Press is a blurred wind swirls back for you (2023), a secondchapbook by Vancouver poet and editor Patrick Grace, following Dastardly (AnstrutherPress, 2021). Set in three sections of sequence-fragments—“a brazen thing,” “thesky cottoned” and “a blurred wind swirls back for you”—this is a curious chapbook-lengthsequence, offering one step and then another, towards a kind of expansion, say,over a particular ending or closure. The first section offers what might be aflirtation, writing as the third page/fragment:

lightning came lightning lit the night

it gave us an easy in

an ice

to break

Whatstrikes most are the rhythms, the pacing; a very fine patter across a length oftethered fragments, although there are some moments in the language that strikefar less. Either way, there is something interesting here, and worth payingattention to, to see where Grace moves next. I say keep an eye on this one.

June 29, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Matthew Hollett

Matthew Hollett is a writerand photographer in St. John’s, Newfoundland (Ktaqmkuk). His work exploreslandscape and memory through photography, writing and walking. Optic Nerve, acollection of poems about photography and visual perception, was published byBrick Books in 2023. Album Rock (2018) is a work of creative nonfiction andpoetry investigating a curious photograph taken in Newfoundland in the 1850s.Matthew won the 2020 CBC Poetry Prize, and has previously been awarded the NLCUFresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers, The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Prizefor Best Poem, and VANL-CARFAC’s Critical Eye Award for art writing. He is agraduate of the MFA program at NSCAD University.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, AlbumRock, is a mix of creativenonfiction, poetry and archival material investigating a strange photo taken inNewfoundland in the 1850s by Paul-Émile Miot. The project began as a blog post,then expanded over several years to a research grant, an exploratory road trip,and eventually a published book. You learn so many things over the course of along-term project like that (publishing contracts, working with editors anddesigners, image permissions). It’s not lightning-bolt life-changing, but morecumulative. It snowballs.

My most recent book, OpticNerve, is a collection of poems aboutphotography and visual perception. It took shape over many years, too, and hadits own complicated flight path. Both books gesture towards some of the sameideas and preoccupations – ekphrasis, photography and complicity, a sense ofplace – but they’re very different. Album Rock is a macro lens, OpticNerve more fish-eyed. I like that oneis published by Boulder and one by Brick. A good solidity there.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

I came to poetry through My Body Was Eaten by Dogs by David McFadden – it caught my eye one day in my high school library,and I read it cover to cover and almost immediately started writing poems.Terrible poems. Shortly afterwards I became fascinated by E.E. Cummings, andfilled notebooks with floaty visual cloud-poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

My projects always begin as a nebulous collection of small things whichgradually cohere into a larger thing. I am always generating small things:journal entries, field notes from walks, poem fragments, quotes from books,photographs. Every project is rooted in these archives. So beginning somethingnew is usually a matter of sifting through bits and pieces, finding unexpectedconnections.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

A single poem usually begins either as a firsthand observation, or as anexploration of language (sometimes I think of the poems as either “outdoorsy”or “indoorsy”). Bookwise, OpticNerve is themed around photography andseeing, and I’m working on a new collection of poems about walking.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love reading aloud. During solo writing residencies I’ve often readentire books aloud to an empty house, which is a fantastic way to feel immersedin the writing’s texture and soundscape. I write my own poems with the ideathat they will be read aloud, and enjoy public readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I like looking at things. The current question depends on what I’mlooking at. The bigger question, of course, is what to look at.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I’ve always liked Kurt Vonnegut’s take on this: “I sometimes wonderedwhat the use of any of the arts was. The best thing I could come up with waswhat I call the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. This theory saysthat artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They aresuper-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long beforemore robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

Working with an editor is difficult in the best kind of way, where youfeel discomfort, which is the sensation of being challenged and learning andchanging. I find it essential, but never easy.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

From Guy Debord’s autobiography: “My method will be very simple. I willtell what I have loved; and, in this light, everything else will become evidentand make itself well enough understood.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry tophotography)? What do you see as the appeal?

It doesn’t feel like moving between genres – both poetry and photographyare the work of seeing things in new ways. I’m fascinated by the way that poemsand photos can complement each other. They both feel like quieter, moreintimate ways of making, creating meaning by stringing a series of smallobservations together.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My only routine is to read for about 45 minutes as I eat breakfast. Irealize it’s a luxury to structure my mornings this way, and I cling to itdesperately. I don’t have a regular writing routine, but I make writing timeduring evenings or days off, or once in while through grants, residencies orcreative writing classes.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Going for a long walk works miracles. I can sometimes also unblock mybrain by switching from my computer to writing on paper.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Ocean wind – not so much the fragrance but the force of it. There’snothing like the breath-burgling, voice-snuffing, brain-numbing winds out onthe headlands near St. John’s.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

I went to art school, and I really enjoy writing in response to images –paintings, photographs, films. Anything visual. I’m especially interested inthe way that documentary films can be lyrical and poetic (I love Agnès Varda’swork, and Werner Herzog’s), and the way that they can weave real-lifeobservations together to create meaning. There are lessons there for poetry, Ithink.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Teju Cole is an incredible writer and photographer and I enjoy his booksimmensely. I just finished reading Robert Macfarlane’s Underland and reallyloved it. Likewise Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. And one of my favourite films is Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I, a documentary about finding things, which begins in whimsy and moves almost surreptitiously to morepoignant social concerns.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A really long walk, like the Kumano Kodō or the Pennine Way or theCamino de Santiago.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

Writing is an ongoing creative practice for me, but I wouldn’t call itan occupation. I do lots of things that are not writing – photography, designwork, web development, arts administration.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing gives me a specific kind of joy that I don’t experienceelsewhere. I love language – its sound, its mouthfeel, the deep deep history ofwords – and I get enormous pleasure from the process of wrangling language intosomething poem-shaped or book-shaped.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Teju Cole’s BlackPaper is a collection of brilliant,incisive essays about art, photography and seeing. Cole traces Caravaggio’stravels in exile, considers what it means to look at photographs of suffering,and writes about writing during dark times. “The secret reason I read, the onlyreason I read, is precisely for those moments in which the story being told isdeeply alert to the world, an alertness that sees things as they are or dreamsthings as they could be.”

I watch a lot of movies. The one I’ve enjoyed the most recently is CiroGuerra’s The Wind Journeys. It’s set in Northern Colombia, and in addition to marvellouscinematography, characters, and music, it features the most captivatingaccordion battles ever put to film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A collection of poems about walking.

June 28, 2023

Béatrice Szymkowiak, B/RDS

Re/sound

How pleasing when aclouded sky

ripens with rain. Water-logged

seeds imagine blossoms& the swell

of duration / wings sail along

ponds & hedges /clear rivulets

root rivers. Hear in shallowpools,

the unremitted flappings/ flocks

wading the course of days

in the afterstorm / an axe’sthud

hung at the extremity ofa twig

drops & drowns. Ringsripple,

quills / fly off.

Thefull-length debut by French-American writer and scholar Béatrice Szymkowiak [see her recent '12 or 20 questions' interview here],following RED ZONE (Finishing Line Press, 2018), is B/RDS (SaltLake City UT: The University of Utah Press, 2023), published as winner of theAgha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry. Much like New Hampshire-based Polish-American poetand translator Ewa Chrusciel’s recent Yours, Purple Gallinule (Omnidawn,2022) [see my review of such here], B/RDS (obviously) is a book of birdsthat writes into the Anthropocene and out of John James Audobon’s Birds ofAmerica (1827-1838) as a source text both for content and language, pullingthreads and highlighting the losses of entire species of birds due to humaninterference. As Szymkowiak offers as part of the book’s “Preface”:

My writingprocess started by considering the text of Birds of America (the OrnithologicalBiography accompanying the drawings) as an archival cage. For this reason, Iresolved to strictly abide by the rule of keeping the order of the words (orletters) from the text-source—my text-source being Birds of America in alphabetical order. I then selectively erasedthe textual cage to reveal its ambiguity and the complex relationship betweenhumanity and the other-than-human world. As the cage disappeared, birdsescaped, their voices inextricably entangled with ours—a spectral, equivocal “we.”Finally, I reshuffled the resulting poems and added migratory poems written inmy own words and prompted from lines from the erasure poems. These migratorypoems, like ripples, trace the link between past and present.

B/RDS is a book of precision and moving through space,through air, propelled and attuned to a uniquely-magical language and lyric. Thereis such delight and play of strike and sound through these lines, even as eachpoem sits as an individual cobblestone or brick, each set to articulate theaccumulated outline of her subject of ecological erosion. She writes on birds,and the waves of man-made losses and their rippling effects. As Agha Shahid AliPrize judge Monica Youn writes as part of her “Foreward”: “Throughout Béatrice Szymkowiak’sdevastatingly beautiful B/RDS, I felt as if I were responding to asimilar call, but the echoing voices in this collection are real, urgent,inescapable—a fusion of elegy and prophecy. With its trills and elisions, gracenotes and percussive cries, the collection gives voice to the billions of birdslost on this continent over the past decades through human predation, industrialization,waste and sprawl—James Elroy Flecker’s classic phrase seems apt: ‘That silencewhere the birds are dead / yet something pipeth like a bird.’” Szymkowiak simultaneouslywrites directly and slant on birds and their losses, writing of seasons andflights, of sun and landscapes along the ridge. As the prose poem “Wherever SunEnds” writes, in full: “Two crows perched in the pine grove caw ghosts ofunsung passing. Ice spears from the eaves. Dread devours clouds. I fear howtangible your tongue before its silence. Deer ellipses dot the snow thawing clock.On the ground, a red-tailed hawk claws & tears its own disappearance.”

The Night Is Pitch-Darkbut We /

murmur through shatteredglass breathe, breathe, the light from dead stars still glows! Along nighteaves, mangled starlings heave stellar wings to tenebrous ceilings & tiltequinox back to breathe, breathe constellations. Light isshattered from the mangled night. how many dead stars still glow?Tenebrous wings cleave away from you, heave equinox back to pitch-darkceilings. Breathe, breathe, starlings murmur along mangled eaves, howconstellations tilt from dead stars to light! Still you,shattered wings through tenebrous glass murmur how many, how many dead stars

& cleave equinoxhalves away.

June 27, 2023

A manifesto on the poetics of Asphodel Twp.

Sadto hear, via the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild (through a facebook post) that Canadian bookbinder Michael Wilcox has died. Back out in2011 (July, I think) we drove out to Big Cedar so Christine could interview himfor the CBBAG magazine, and she brought me along for the sake of the three-plushour drive, as well as for the fact that the Wilcox was well-known for hisgruffness. Wilcox was a Master Bookbinder, and had been decades been repairingbooks for the University of Toronto Rare Books Library, driving up to pick upbooks to take home for repair (I suspect he was the only one allowed to leavethat building with any of their materials).

Wedropped into his studio, and apparently the fact that I tagged-along allowedfor some stories he might not have told. Before the interview officially began,he showed us his studio workshop, including the incredible array of tools he’d hand-made.Given I’m unaware of most printing and book-repair tools (especially then), I keptasking him what various items and equipment were and were for, which wouldprompt him to tell a small story for each (stories he might not have told,Christine says, as she would have known what all that equipment was). It was aninteresting visit, and his wife Suzanne was delightful, and she said we couldcome back and visit at any time (he didn’t seem against the idea, but also notthe sort of thing he might have offered). I’m wishing we would have taken her upon that (although he and Christine did correspond quite a bit after our visit).

Here'sa poem I wrote them, after we landed back home (and yes, they did live inAsphodel Township):

A manifesto on the poetics of Asphodel Twp.

for Michael & Suzanne Wilcox,

Ihave forgot

and yet I see clearly enough

something

centralto the sky

which ranges round it.

William Carlos Williams, “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower”

1.

If Heaven, river. What greeny something. Shine,Kawartha Highlands. Lake, and early hum. Once, in the shadows. Glowingoutwards, temperate. Ontario syntax. Reassuring this, and self. A revelation,you. I see the world. Claw, in architecture. Bipolar lift, a tongue. A peacethe mind can breathe. Although the dark remains, small lights in favour.Celebration, soar.

2.

The mouth, at Cameron's Point. An acid-free layer.Craft: a promise, fold. Is this all nothing? Repair, a situation. Sorrow, and acock-eyed grin. In this room, this other room. A complicated, binding. Thismorning, Highway 7. Double-binding, surface of a still. Lovesick Lake, meetinghip to shape to shore to night. A glacier, made. Such frozen light.

3.

Asphodel, greeny flower. Surveyed in 1820, RichardBirdsal. To warm up, bottles under covers. All the uphill way. If it is,repeated. Notes, and highway. Hummingbird feeders, to keep from ants, fromblack bears. An empty bench, among. Back and forth, snow-scribbling. Some otherstar. The metaphor: cast iron, photo-legal. Walking. John Becket and his wife,five children.

4.

You left your mark. Combination of industry. Vaguelyseen, but can't cross. Waterskin. Go, central-eastern. The shores of Rice Lake,frequent. Burned away. Big Cedar, smoke. Yours, truly. Tell, no other story.Picked up, by useless clouds. Such well-bred manner, brush. Such lovely liquid.A leather casing, isolation. Those that have the will.

June 26, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tucker Leighty-Phillips

Tucker Leighty-Phillips is the author of

Maybe This Is What I Deserve

(Split/Lip Press, 2023). He lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. Learn more at TuckerLP.net.

Tucker Leighty-Phillips is the author of

Maybe This Is What I Deserve

(Split/Lip Press, 2023). He lives in Whitesburg, Kentucky. Learn more at TuckerLP.net.1 - How did your first chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It’s difficult to answer this question in past-tense, because it continues to change my life. It has been a comfort to hold it and know that I created it. I used to work with a lot of musicians–I was a show promoter, a booking agent, a tour manager and merch guy. But I was never an artist myself, and I envied that a lot. I wanted something to call my own. I wanted it to be music, but I could never play. Releasing my first chapbook feels like releasing my first EP. It’s something I can point to and feel good about.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I think it’s just the form that interests me the most. When I was a kid, I read Louis Sachar’s Sideways Stories From Wayside School over and over. It contained everything I could ever want in a book–humor, invention, brilliant callbacks and lively storytelling. Something about the possibilities contained within that book made me want to contribute to the world in a similar way.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Every draft is different, which is a boring answer, but it’s true. Some of my favorite stories are ones I’ve hammered out in one sitting, or thought about in my head for a long time before committing it to the page. I’m also not a very good editor, so if it doesn’t work early on in the process, I may lose interest. Pitiful, I know.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ve always wanted to be a “project” writer, because some of my favorite books are projects. I love the long-form exploration of an idea. I’m reading Joe Brainard’s I Remember right now, and his approach is so fascinating. It’s a true honeycomb of a novel. I’d like to commit to doing something similar at some point. I typically just write short stories and see what they do when placed in close proximity, rather than thinking about an umbrella theme from the jump.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I think readings are fun, but I wish they were more fun. I want to be more deliberate about creating an atmosphere when I read, being a performer. There are some authors whose readings I’ve really loved, because they know how to perform. Danez Smith comes to mind. I’m also a longtime fan of Scott McClanahan’s boombox readings, where he would read a story with music playing on a boombox in the background, and in a climactic moment would destroy the boombox, hold a lull in the room, and then pull out another boombox playing the same song, picking up where the last boombox left off.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I was doing a bunch of applications a year or two ago, and I always led with a mission statement: Tucker’s work celebrates the lives of the impoverished, but never romanticizes their poverty. I wanted to create work that felt true to a lived experience, without doing the hokey “everything’s okay and we don’t actually require material needs because we have each other.” We can still have each other, even if nothing is okay.

I think that continues to be a major theme in my work, but it’s also evolved. I’ve been writing a lot about nostalgia, a concept I’m skeptical of, but love to play with in my work. Nostalgia feels conservative in a lot of ways. It yearns for a previous time. It glorifies individual experience. But it can also be a tool of connection–to find our similarities, to understand the ways we think alike. I’m trying to use it as a critical tool in my work, to reexamine the past and imagine a collective, more communal future.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oh man, that’s a much bigger question than I can wrap my brain around. I think they should punch up, for sure, and be willing to call out those punching down. I think they should continue to find possibility and explore it, even in places where it seems there is none.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve never had a problem with them. Sometimes, a difficult editor is one who cares a lot, and wants to tighten your work. It has done me good to fight to defend my prose.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Well, I don’t think it works anymore, but I once read that you should sign up for AAA Membership from your cell phone after you’ve broken down. But now I think they make you wait a week for your membership to kick in. I used it once and it saved me a ton of money.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to plays to essays/reviews)? What do you see as the appeal?

The ease fluctuates! There are months where I can’t envision anything beyond a single medium. And then there are days where I am working on three at the same time. I am also always interested in blurring the lines between genre distinctions and toying with what’s possible. I remember there being an old Reddit thread about what Major League Baseball would be like if games were only played once a week, and the post turned into this heartbreaking, harrowing account of love, artistic success, and loneliness. It was deleted a while back, but I think about it often, because it was one of the first times I was genuinely surprised by a piece of writing on the internet.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have absolutely zero routine. I am very flighty and cannot commit to any kind of schedule. When it hits, it hits. When it isn’t hitting, I don’t bother.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I like attending readings. There aren’t a ton where I live, but I always come away with new ideas and enthusiasm. I think that’s important, trying to be in a shared space with people who are excited about art. We’re communal creatures.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Grippo’s potato chips and compost.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Oh absolutely. I would say I’m arguably more inspired from non-books than I am books. Nickelodeon shows like Hey Arnold, The Adventures of Pete & Pete, and Rugrats play a huge role in my work. Old Looney Tunes cartoons; their internal logic and engines especially. The films of have been massively important to my progression as an artist. I’m also heavily influenced by gossip–I try to write stories that feel like anecdotes from within a community.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are a few writers or books who I’ve read and found something unlock within me–the most notable being Deb Olin Unferth, Scott McClanahan, Shivani Mehta, Renee Gladman, Michael Martone, and Lucy Corin. When I was a teenager, I read Vonnegut and Brautigan, and I think they helped attract me to the short-form.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I really want to get into mudlarking. I watch lots of videos of people in England doing it.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, when I first went to school, I thought I wanted to go into PR. I don’t think I ever wanted to do it, but it felt like a good use of my skills. I really like cooking, and felt like working in kitchens gave me a lot of tangible skills. It’s important to know how to use a kitchen knife.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Honestly, I have no idea. I didn’t really write until my mid-twenties, and it felt like something clicked. Like I mentioned, I always wanted to be a musician, but could never get it right in lessons. I started writing, and felt like I was always steadily improving, which was motivating. It feels good to progress in something.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last book I loved was Lindy Biller’s Love at the End of the World, which is a chapbook story collection about climate change, motherhood, and the experience of trying to be a kind person even amidst an apocalypse. I haven’t watched a movie in a hot minute, because I’ve gotten really into Columbo , but I did recently rewatch Ozu’s Good Morning, which is one of my favorites.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m mostly sending emails to promote MTIWID, but I’m still kicking around a couple projects. I’m superstitious, but I’ll say one of them is a novel-length quasi-historical Appalachian fairy tale. Someone referred to it as “Evil E.T.”

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 25, 2023

two poems + an upcoming (Ottawa) reading,

I've two poems online as part of the new issue of horseshoe literary magazine! So, that's pretty cool.

Oh, and did you see I'm reading this Thursday night with touring poet Kevin Spenst (Vancouver) and Conyer Clayton (Ottawa)

?

I've two poems online as part of the new issue of horseshoe literary magazine! So, that's pretty cool.

Oh, and did you see I'm reading this Thursday night with touring poet Kevin Spenst (Vancouver) and Conyer Clayton (Ottawa)

?June 24, 2023

Quietly Between: Megan Kaminski, Brad Vogler, Lori Anderson Moseman and Sarah Green

with texture and light

with words sunk

skin hoarding electric

my relation to scarcity

to extended touch (lack)

I tell you stories I tellno one

that they were just names

whispered from ash a collection

of coin without reprieve(Megan Kaminski)

I’mintrigued by Quietly Between (Fort Collins CO: A Viewing Space, 2022), aquartet of solicited poem sequences and photography by American poets Megan Kaminski, Brad Vogler,Lori Anderson Moseman and Sarah Green that each respond to the same veryparticular prompt. As the original prompt, included at the back of thecollection, opens:

15-25 images/cards (combinationof text and image).

Begin with place andtime.

Place(s): where youare/were. Both text and photos could be of your present place. Or one elementis, and the other draws from something else.

Time: some element oftime is incorporated into the project. In the film All the Days of the Year,Walter Ungerer returns to the same place in Mount Battie, Camden, Maine everyday for one year. He sets up his camera, and takes thirteen, ten second shotswhile turning the camera clockwise.

Curiouslyenough (at least to me), three of these poets are above/ground press authors,with the fourth, Sarah Green, being a name entirely unknown to me before this. FromLawrence, Kansas, Kaminski writes “this wide open heavy”; from Fort Collins,Colorado, Vogler writes “Ceremony of Knotted Songs”; from Provo, Utah, Mosemanwrites “(t)here now soon new”; and from Joshua Tree, California, Green writes “HoldingGround.” I’m fascinated by each contributor’s approach to the serial poem and thepoem/photograph interplay, as well as to the poem-as-document, an echo of how Canadian poet Dorothy Livesay termed her own particular exploration through thetradition of the Canadian long poem, “the documentary poem,” or even to Lorine Niedecker’s own simultaneous explorations examining geography and languagethrough and against each other. “My project documents a deep listening and akind of answering,” Megan Kaminski writes, to open her “PROCESS” note at theback of the collection, “as well, to the human and more-than-human persons thatcall us into relation and into the specificity of place through their whispers,songs, and histories. From the Kansas Ozarks to my backyard in East Lawrence,to First Landing State Park in Virginia Beach where I sought refuge as ateenager, to the daily bike rides to the Wakarusa wetlands on the edge of town—likethe oversaturated spring and summer soil, my embodied experiences and thesepoems soaked up all that fed them.” Each of the four poets have short ‘processnotes’ at the back, offering insight into elements of their thinkings andresponses to the original prompt, and there are interesting echoes that ripplethroughout all four works of attention to small detail, and how each poet respondsthrough landscape to their individual landscapes and how they see them. As LoriAnderson Moseman writes: “I wrote poems not about the images but through them:snapshots became magnets that drew emotions, experiences, ideas to them. I wouldrevise words as more photos/life events joined the sequence. The most dramatictransformation came after a conversation with Brad Vogler. He challenged me tonot limit my vision of our project: one postcard does not have to contain justa single landscape.”

Curiouslyenough (at least to me), three of these poets are above/ground press authors,with the fourth, Sarah Green, being a name entirely unknown to me before this. FromLawrence, Kansas, Kaminski writes “this wide open heavy”; from Fort Collins,Colorado, Vogler writes “Ceremony of Knotted Songs”; from Provo, Utah, Mosemanwrites “(t)here now soon new”; and from Joshua Tree, California, Green writes “HoldingGround.” I’m fascinated by each contributor’s approach to the serial poem and thepoem/photograph interplay, as well as to the poem-as-document, an echo of how Canadian poet Dorothy Livesay termed her own particular exploration through thetradition of the Canadian long poem, “the documentary poem,” or even to Lorine Niedecker’s own simultaneous explorations examining geography and languagethrough and against each other. “My project documents a deep listening and akind of answering,” Megan Kaminski writes, to open her “PROCESS” note at theback of the collection, “as well, to the human and more-than-human persons thatcall us into relation and into the specificity of place through their whispers,songs, and histories. From the Kansas Ozarks to my backyard in East Lawrence,to First Landing State Park in Virginia Beach where I sought refuge as ateenager, to the daily bike rides to the Wakarusa wetlands on the edge of town—likethe oversaturated spring and summer soil, my embodied experiences and thesepoems soaked up all that fed them.” Each of the four poets have short ‘processnotes’ at the back, offering insight into elements of their thinkings andresponses to the original prompt, and there are interesting echoes that ripplethroughout all four works of attention to small detail, and how each poet respondsthrough landscape to their individual landscapes and how they see them. As LoriAnderson Moseman writes: “I wrote poems not about the images but through them:snapshots became magnets that drew emotions, experiences, ideas to them. I wouldrevise words as more photos/life events joined the sequence. The most dramatictransformation came after a conversation with Brad Vogler. He challenged me tonot limit my vision of our project: one postcard does not have to contain justa single landscape.”Kaminski’s“this wide open heavy” offers a kind of unfurling across sixteen short lyricbursts, providing one step and then a further step. “to enter into a clearing,”the opening poem writes, “to bathe in gray April light / not-dying not quiteemerging [.]” Vogler’s “Ceremony of Knotted Songs” is a sequence of sixteennumbered poems, and there is such delicate thought and placement to his shortlines and phrases. “I keep going back // here there,” he writes, to open thesecond poem. Or as the third piece begins: “pillowcase curtains / season with/ wind [.]” I very much likethe way Moseman’s “(t)here now soon new” writes around and across herparticular landscape, spacing out the lyric across the varying and individual pointsacross her view. Her particular lyric offers a kind of accumulation ofindividual points across a wide gesture. “dear cottonwood,” she writes, “I cannothear you / from the far jetty // your roar fell last fall [.]” And for Green, her“Holding Ground” is the first I’ve seen of her work; the effect of each poem isakin to setting down one playing card after another, each card shifting themeaning of what came before, each poem self-contained in a kind of tethered rowof lyric moments.

Viathe poetic sequence, each of these four poets offer their variation on thestretched-out lyric sketch, allowing this collection to emerge into a bookabout being present in temporal and physical space, each poet blending lyricand photographic attention from their own particular American corners, across aquartet of American states moving straight west from the Midwest to the Coast.

mother left a letter

of

naming

(home) tree – sassafras

here ash

for you

walking

walking

unsettled

leaf at (the) river lip

loosed quietly (lost)

(on its way) away (Brad Vogler)

June 23, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joe Hall

Joe Hall [photo credit: Patrick Cray] isa Buffalo-based writer and reading series curator. His five books of poetryinclude Fugue & Strike (2023) andSomeone’s Utopia (2018).He has performed and delivered talks nationally at universities, living rooms,squats, and rivers. His writing has appeared in places like PostcolonialStudies, Poetry Daily, Best Buds! Collective, terrain.org,Peach Mag, PEN America Blog, dollar bills, and an NFTA busshelter. He has taught poetry workshops for teachers, teens, and workersthrough Just Buffalo and the WNYCOSH Worker Center. Get in touch with Joe: Twitter, Instagram, website.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How doesyour most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

2008: I’m sitting at a desk in a sub-basement in Indiana. In frontof me is a candy jar. Behind me is a particle accelerator. My official jobtitle is Secretary. I get an email from Black Ocean. They’re going to publish PigafettaIs My Wife. I get the hell out of there, and I am still getting the hell outof there: my poetry leading me out of the big abyss of bad jobs to the frailextent art can, which is only ever to contribute to a constellation of momentsof momentary escape.

Like my first book, Pigafetta Is My Wife, my fifth book, Fugue& Strike, grows from historical research. PIMWdrew from primary and secondary sources surrounding Magellan’s circumnavigationof the globe and attempt to claim the Philippines; it attempts to turn thesesources inside-out into a self-implicating, anti-imperialist sequence. Fugue & Strike draws on researchsurrounding sanitation strikes and the uses of waste in militant politicalaction. Fugue & Strike departsfrom the mysticism that animates stretches of PIMW, embracing absurdity, humor,and the polemic. It’s tonally rangier and includes prose.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction?

I came to poetry through song, and I came to song through therhythmic boredoms of work, singing while I was mowing strip after strip oflawn. Rapture in repetition. Soundgarden melodiesmutated into my own.

And I came to poetry through evening prayer. Performing a nightlyself-inquiry before an omniscient being transformed into the devotion togetting some thing right on paper. Iwrote my first book in bed—at night until I fell sleep then immediately when Iwoke up, notebook and pen sometimes tangled in the sheets.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

The process is a two-minded mess. I often toggle between apatient, research-based poetics, building up notes, slowly secreting atheoretical framework—and just going for it: freewheeling, intuitive, ecstatic attempts totranslate a whole emotional-intellection moment into the world.

So I write multiple projects at a high volume and get lost in andbetween these modes, often. I have to hit the brakes in order to figure outwhat I’m actually doing and if these different modes make sense together. Sometimesthey really do not.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning?

It’s almost always a book. The poem iterates from some energy thathas a coherence beyond the poem and wants to animate and bind more poems—eachpoem a variegation of the larger distinct wave that is the book and the bookitself an expression of the smaller patterns it contains. That said, whateverRobert Duncan referred to as Life-Melodies, well, usually I mistake thebeginning of a year or two of this iterating energy as a life-poem. So I mostoften feel continuity more than difference when I first draft then must finddifference and silence in retrospect.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ideally, I think about the context that a reading is then reshuffleand sometimes rewrite my poems for that context; sometimes that rewritingsticks and becomes the printed version. Readings are creation, what the scoreeach written poem represents has been waiting for. I owe it to those pieces toperform them in a way that demonstrates this.

But because of the investments I have in readings, they are also abig outflows of energy. That can be dangerous and not enjoyable. And I wishthere were more expansive formats for readings. 10-15 minutes just doesn’t fitmuch work or many readers. There are so many poets I would listen read for anhour who will never get the chance to read for that hour.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

Three hauntings:

1. From Marxist ecology: what is apoetics, in this long moment of climate crisis, that can account for (notlandscapes but) ecologies as open-ended, dynamic systems of human and non-humanactors involved in the circulation (and extraction and hoarding and etc.) ofenergy? What is a poetics that can account for the dynamic, open-endedco-evolutionary and thickly contextualized relations between natures andcultures?

2. How might post-2020 theories ofracial capitalism speak to a white writer (Joe Hall) living in a mid-size city(Buffalo) in the imperial core (the United States) to inform municipalpolitical action and the production, distribution, and reception of art withinthat context?

3. What are the answers when we askthese questions together?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

Current? Outside of the big prize-winning Iowa and Ivy-League circle-jerk club and all the people outside thesenetworks bending their best energy toward the delusional goal that they’ll beable to join that club, I think there are a lot more poets than we might thinkwho have, in the last ten years, hooked up with social movements, grass rootsgroups, unions, etc. They’re organizing, being organized in the crosswinds of aprofound post-2020 backlash and proposing through that activity relationsbetween writers and culture. But how to exactly define that relation betweenartists and culture, what’s going to come out of it, part of that is alwaysgoing to be subterranean and part of that, in this moment, is still germinal.That’s cool. We’ll see. But we may not see without more literary journalismgenuinely curious about the full scope of writers lives and theinterconnections between poetry scenes and social movements. So I guess whatI’m saying is that cultural production and political practice should informeach other and we should represent that in non-naïve terms. We should do thatwhile also being skeptical of universalist claims of the politics of any aestheticsoutside of considerations the specific networks a given work circulates within.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Essential and desired.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

I was tempted to quote one of my first teachers of poetry, Lucille Clifton on the necessity of bringing one’s whole self, including their hatred,especially their hatred, into a poem. But since I’ve been seriously ill lately,here’s part of a parable of Chuang-Tzu in the translation I first received itin 2001. In it Master Yu is dying and is attended by his friend:

All at once Master Yufell ill. Master Ssu went to ask how he was. "Amazing" said MasterYu. "The Creator is making me all crookedy like this! My back sticks uplike a hunchback and my vital organs are on top of me. My chin is hidden in mynavel, my shoulders are up above my head, and my pigtail points at the sky. Itmust be some dislocation of the yin and yang!"

Yet he seemed calm atheart and unconcerned. Dragging himself haltingly to the well, he looked at hisreflection and said, "My, my! So the Creator is making me all crookedylike this!"

"Do you resentit?" asked Master Ssu.

"Why no, whatwould I resent? If the process continues, perhaps in time he'll transform myleft arm into a rooster. In that case I'll keep watch on the night. Or perhapsin time he'll transform my right arm into a crossbow pellet and I'll shoot downan owl for roasting. Or perhaps in time he'll transform my buttocks intocartwheels. Then, with my spirit for a horse, I'll climb up and go for a ride.What need will I ever have for a carriage again?

Recognize everything is change (Epicurus, Lucretius, Marx).Approach that change with delight and curiosity as to its possibilities. Thenride your butt-bike into the darkness.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetryto essays to music)? What do you see as the appeal?

At first poetry and song where the same polysemous ball of stuff.Now that the boundaries between poetry and essay can be thin when I’m writingsomething I’ve learned a lot about. A long piece in Fugue & Strike, “Garbage Strike / 🗑️🔥,” crosshatches poems striving for agarbage-compacted density of materials (to create an unpredictable connotativeleachate) with essay—sometimes, elliptical, sometimes not—on histories andfutures of waste and militant actions with waste or by waste workers. An essayI’m writing now on the implication of canonical sonneteers in the earlyformation of English settler-colonialism and racial-capitalism actually grewfrom footnotes on an anti-sonnet a friend suggested I grow into somethinglarger.

The relation between poetry and essay is easy when the subject isthe same. The appeal there is that essays can provide a rich contextualframework to inform a poem’s play.

Okay, halfway through. Take a breather, reader.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Age, entropy: no words arrive without an hour of body work after Iwake up. Exercise, stretch the damaged bits, prepare a breakfast that fits mychronic illness. A bit of reading. Then I write. But C.A. Conrad argues writingshouldn’t be like working in a factory (or as an on-demand worker for a taskapp company). I’ve been there. It sucks. So my writing routine only works when Ialso carry that writing beyond the boundaries of that routine and am receptiveto how the messages of the larger world unfolding around me must shape thatwriting. This is why I’m most productive when I go to sleep in thecross-currents of thinking about my days in the world and what I’m going to writein the morning.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t know how to answer this question. Sometimes I avoidinspiration and embrace being stalled. There are crucial times I need to avoidother poetry, especially poetry I love, and sink into my life. I wait forfriction with the world to intervene—the social ecologies of my house, myblock, my neighborhood, growing outward. Or sometimes a friend lovingly kicksme in the ass. That’s probably what I need—someone to keep me from revising mybest work into particles.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Burning wood.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Forms: I can’t help but think of Bernadette Mayer’s exercise towalk through a city and, on each new block, write a single line of a sonnet. OrMei Mei Berssenbrugge’s idea that the line is generated by the body’s sense ofextension, or periphery in a particular environment. I have the sneakingsuspicion that pandemic-era long aimless walks through Buffalo’s empty,pot-holed roads and uneven sidewalks may be expressing themselves in the longlines of many of the poems I’ve written in the last year. As did a bike path inBuffalo alongside the Niagara River. In stereo: the river flowing and the 190’swhip-sawing traffic.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

Samuel Delany: The Mad Man,The Motion of Light on Water, Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand; John Milton’s Paradise Lost and The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates; a whole world of documentary poetry from Rukeyserand Reznikoff to Susan Tichy, Mark Nowak, and Craig Santos Perez to Janice Lobo Sapigao.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a book while not worrying about money or time, but, hey, whodoesn’t want that?

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

When I was in middle school in Western Maryland I was asked towrite about a future self I hope to be, and I said I hoped to be working in andoffice and living in an apartment in Ohio. I fucked up. Work sucks. I hate it.Get me cultivating a big, big food and flower garden and doing somebio-remediation in a city with a new, more functional body. I’ll do it withfriends. I’d love that. Is that a job?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Where to start? A deeply felt incompatibility with the socialworld. A huge gap between I and thou. In the words of Karen Brodine: "All my life, the urgencyto speak, the pull toward silence." I came up in a disciplinaryenvironment and my parents giving each other loudly and at length the woundsthat would cause them to split. I had weird dreams—a whale corpse, itsmoldering eye looking into my bedroom window, a planet made of condensed, heavystatic, bearing down through a void that couldn’t be more complete.

And alot of time alone as a kid, to roam in the woods we lived beside.

And aninfinitely patient grandfather who lived next door, through these woods, who Icould interrupt, say, while he was splitting wood, to sit down at the kitchentable and talk while he smoked.

Whocan say if this explains it? For a long time it did. How about I was painfullyshy? If I could be alone with language and that would still connect with otherpeople? That would be nice.

Otherthings happened to change the reasons I wrote, thankfully. Then, a sort ofmomentum kicks in.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Book: Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, Samuel Delany’s 872 page door-stop about the lives ofpartners Eric and Shit in a black, queer commune on Georgia’s Gulf Coast. A lotof labels have been applied to this novel (like a pornotopia) but the point ofDelany is that none of them quite stick. It’s a novel as ferocious, unsettling,gently, steady, and terrifying as the ocean that is it’s backdrop.

Film: Congratulations, you’ve made it this far, so you get tolearn a secret. For over a decade, my partner Cheryl and I have been recordinga hardly ever advertised podcast about movies. We watch a movie. Wetalk about it. We like the excuse it provides for us to talk at length and withintention about something. Through the podcast, I’ve found myself thinking moreand more lately about Bi Gan’s 2018 LongDay’s Journey Into Night. It’s a mysterious, trance inducing poem in a noirshell. And a great piece of Chinese cinema that slipped by before as theboundaries erected by the U.S. against U.S.-Chinese cultural exchange growharder and harder. Try watching The Battle at Lake Changjin in the U.S. It’s the highest grossing Chinese filmof all time. You can’t watch it. Also, Bacurau rips.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Thesequel Fugue & Strike. It’sprovision and likely to change title:Fugue & Fugue & Fugue. It’s shaping up to be a big book of poems.It goes full Buffalo, inspired by Samuel Delany’ssentences, radical municipalism, and the knot of rage and despair that was andfollowed the people of Buffalo trying to topple the dangerous, centristDemocratic machine here—and losing, for now. The poem, I think, is, in its way,about most small and mid-size, post-industrial cities. Not New York or SanFrancisco: most cities. Help me if I don’t finish it this summer.