Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 86

June 22, 2023

Martha Ronk, The Place One Is

ANOTHER COUNTRY

The it in with-itshifts & pivots as a compass needle

vetch, clover, brackish seaweedin heaped up smells

bits of pulverized shell,skeletal casings underfoot

fog banks stoked by firesin the central valley,

scrims cover whatyesterday stood as branched trees, a

house barely visible—morememory than memory,

unheimlich as if and asif it had been or could have been

you whom I turn to innear-sleep stumbling over ourselves,

whose arms and legs wasit I thought you called

extracting the changedangle between two norths

a skeleton of rusted carseams laid out on the beach

each step unlinked fromthe one before

each detachable makes upthis country I’m pointed into

Withmore than a dozen published books to her credit, the latest from Los Angeles poet and fiction writer Martha Ronk is

The Place One Is

(Oakland CA: OmnidawnPublishing, 2022), a collection of prose structures, each of which attend tothe line even through her use of line-breaks. She centres her America acrossthe length and breadth of her sense of California, offering the elements of hergeopolitical and historical space as a stand-in for far larger, ongoingconcerns of colonialism and the Anthropocene, as well as considerations of how geographyis constructed, where one sits and where one needs to stand. “Ordinary bits oflight on neighborhood leaves,” she writes, to open the poem “NIGHT: A PHOTOGRAPHBY ROBERT ADAMS,” “trees passed by, // spattered not-very-white on a randomnumber of them, // the canopy of leaves wide enough to hold multiple bits oflight // and what I can’t help is how pulled I am into the lights as if my eyes// could focus on multiple places at once which I know they can’t [.]” The structureof her poems is centred in the prose-block, and her narratives work to stitchtogether untethered fragments into a larger quilt of individual patterns of commentary,including elements of history and ecological concerns. “the place one is is theplace that is one,” she writes, to open the sequence “PULLED INTO EARTH, AIR,SKY” early on in the collection, “—nowhere else / and although I can think myselfback into some places, / where one is is the only place and everyone’s feet /change underfoot as wet, sand, concrete, pebbles and smooth / operate as adjustmentsor the particular tree out of the window / one branch hanging down [.]”

Withmore than a dozen published books to her credit, the latest from Los Angeles poet and fiction writer Martha Ronk is

The Place One Is

(Oakland CA: OmnidawnPublishing, 2022), a collection of prose structures, each of which attend tothe line even through her use of line-breaks. She centres her America acrossthe length and breadth of her sense of California, offering the elements of hergeopolitical and historical space as a stand-in for far larger, ongoingconcerns of colonialism and the Anthropocene, as well as considerations of how geographyis constructed, where one sits and where one needs to stand. “Ordinary bits oflight on neighborhood leaves,” she writes, to open the poem “NIGHT: A PHOTOGRAPHBY ROBERT ADAMS,” “trees passed by, // spattered not-very-white on a randomnumber of them, // the canopy of leaves wide enough to hold multiple bits oflight // and what I can’t help is how pulled I am into the lights as if my eyes// could focus on multiple places at once which I know they can’t [.]” The structureof her poems is centred in the prose-block, and her narratives work to stitchtogether untethered fragments into a larger quilt of individual patterns of commentary,including elements of history and ecological concerns. “the place one is is theplace that is one,” she writes, to open the sequence “PULLED INTO EARTH, AIR,SKY” early on in the collection, “—nowhere else / and although I can think myselfback into some places, / where one is is the only place and everyone’s feet /change underfoot as wet, sand, concrete, pebbles and smooth / operate as adjustmentsor the particular tree out of the window / one branch hanging down [.]”Thereare moments that Ronk does describe two sides of geographies, suggesting theplace that one is sits in a space simultaneously unknown, offering two elements,two perspectives, on a singular and multifaceted whole: a place of beauty,suffering, constant possibility and perpetual self-destruction, including thatof, as Brian Teare writes as part of his back cover blurb, the “devastatingimpact of settler colonialism on the Wiyot people of Northern California.” “collectedin multiples piecemeal and over time,”she writes, as part of the poem “SCRAPS OF INDIGENOUS HISTORY,” “stitched withfishing twine housed in museum vaults// the ongoing catapulted into watersmoving out to // unfinished sentences [.]” Or, as the opening poem, “TO LET GO,”begins: “imprecise morning as if limbs were only loosely threaded in the coming// and going of tides, in flattened grazing land extending into beach sand //going on until far out of view, the imprint of a foot then another, // the timeit takes for a seeded oyster basket to mature [.]” It is interesting how Ronkoffers line breaks as sentence or phrase-breaks, composed as breaks of thought asopposed to breath, which allow theaccumulations of her sentence-phrases to pile on like logs into a cabin, constructingthe house of the poem, such as the poem “LEAVING IS ALSO A PLACE,” that begins:

Leaving moves into us,taking us from this place

where we are and from theplace we’re going

into some thirdbi-furcated in-between

as a swollen door doesn’tquite close,

no furniture floatsaround the rooms

but all groundings areweakened

tattered bird wings droopfrom the poles

June 21, 2023

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach, 40 Weeks

Nature must be a mother

to pour : thunder : punch

through potholes : hopingthis

will make something :anything

: grow : she must be moths: mouth

wide : wings panting forlightning :

who else would strikeherself : flame

veining the air? who elsewould bear

children to rise inspring : only to feel them

cut months later? themoth’s

charred outline on a log: the double

wound : her children’shead sinking

: left to dry on anothermother’s

windowsill : who elsewould ask

for such a violence?

Granville, Ohio-based poet Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach’s third full-length poetry title,following (Kent State University Press, 2019)and

Don’t Touch the Bones

(Lost Horse Press, 2020), is

40 Weeks

(PortlandOR: YesYes Books, 2023), a book-length poem on pregnancy and the difficultiesof waiting, wanting, catching and becoming. 40 Weeks follows pregnancy,a loss, and a further pregnancy, offering her poem-titles as individual andconsecutive weeks, each named and sized after a corresponding vegetable-to-fetussize, from “Week 4: Poppy Seed” and “Week 9: Grape” to “Week 14: Lemon” and “Week28: Eggplant.” Across this book-length suite, Dasbach composes a mapping of anintimate space, and the emotional and physical complexities and interruptionsof everything that pregnancy, mothering and motherhood involves and surrounds. Shewrites violence and loss, swirls of surrender and survival. As the short single-sentenceof the poem “Week 21: Carrot” ends: “into the street with your sun / still insidehis laughter / brought icicles down / from a neighbor’s gutter / they shattered/ irreparable / far from his body / unprotected and wholly / outside of you /inside / her fingerprints / became / permanent [.]”

Granville, Ohio-based poet Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach’s third full-length poetry title,following (Kent State University Press, 2019)and

Don’t Touch the Bones

(Lost Horse Press, 2020), is

40 Weeks

(PortlandOR: YesYes Books, 2023), a book-length poem on pregnancy and the difficultiesof waiting, wanting, catching and becoming. 40 Weeks follows pregnancy,a loss, and a further pregnancy, offering her poem-titles as individual andconsecutive weeks, each named and sized after a corresponding vegetable-to-fetussize, from “Week 4: Poppy Seed” and “Week 9: Grape” to “Week 14: Lemon” and “Week28: Eggplant.” Across this book-length suite, Dasbach composes a mapping of anintimate space, and the emotional and physical complexities and interruptionsof everything that pregnancy, mothering and motherhood involves and surrounds. Shewrites violence and loss, swirls of surrender and survival. As the short single-sentenceof the poem “Week 21: Carrot” ends: “into the street with your sun / still insidehis laughter / brought icicles down / from a neighbor’s gutter / they shattered/ irreparable / far from his body / unprotected and wholly / outside of you /inside / her fingerprints / became / permanent [.]”Setin a sequence of weeks, Dasbach articulates poems about and around pregnancyand motherhood that ripple out into poems about how precarious and wonderful itis to live, and live deeply, allowing every part of her to surrender to anexperience that overtakes every cell. “Four times they drew,” she offers, toopen “Week 31: Coconut,” “checking blood / for sweetness—how quickly / the bodycan dissolve / what feeds it.” There is such a delicate precision to thesepoems, simultaneously hard-set and tender, as Dasbach composes poems ofbecoming and becoming more; of being and the slow difficulty and clear beautyof pregnancy and motherhood, along with all the confusion, insecurity, heartbreakand all else that can’t help but come. “You’ve been leaking / for weeks now,”the poem “Week 38: Leek” begins, “secreting, sieving, / seeping, sweating even/ in the absence / of heat. You’ve been / leaving yourself / on every fabric, /spending more time / surrounded / by water / so what escapes / comes home.” Dasbach’s40 Weeks really is a breathtaking collection of documented moments inset lyric, even through the rush of attempting to document each moment as itoccurs, before it moves on to the next, and remains in no other form but throughmemory, or here.

June 20, 2023

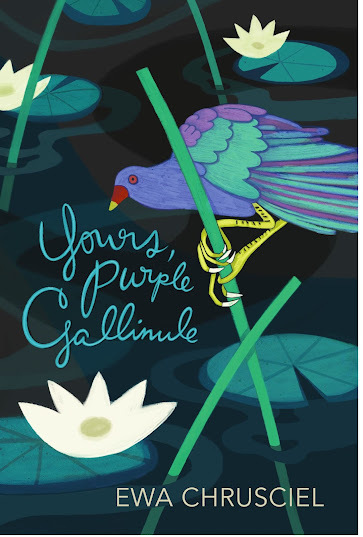

Ewa Chrusciel, Yours, Purple Gallinule

Tiny Throat Diagnoses

I have been listening toyou, dear loon.

I hear in your trilling amelancholy.

you inherited melancholyfrom your grandparents. How do you

regulate the states ofyour system? Neurotransmitters? How do you

restore your humoral equilibrium?

The point – entelechy? A relationshipbetween real and potential,

with astonishment of feathers.

I’mfascinated by New Hampshire-based Polish-American poet and translator Ewa Chrusciel’slatest full-length poetry title in English, her

Yours, Purple Gallinule

(Omnidawn, 2022). Following her prior English-language collections (she alsohas three collections published in Polish) Strata (Emergency Press, 2009;Omnidawn, 2018),

Contraband of Hoopoe

(Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here] and

Of Annunciations

(Omnidawn, 2017) [see my review of such here], Yours, Purple Gallinule is a book of birds, illnesses and depictions;a book of vertigo, pneumonia, diagnoses and mental aviaries, as well as avariety of temporal spaces. “In the meantime,” she writes, as part of the poem “TinyThroat Diagnoses,” “the larks rolled like scrolls around the pins of their /own laughter. What were they laughing about? They were simply / disciples ofjoy.” There is an opening of time beyond what we know into the knowledge ofbirds, from Hildegard of Bingen to Thomas Jefferson, and translations from theMiddle Ages to the narrator’s “80-year-old dad [who] visits from his nativecountry.” (“Acts of Exile”).

I’mfascinated by New Hampshire-based Polish-American poet and translator Ewa Chrusciel’slatest full-length poetry title in English, her

Yours, Purple Gallinule

(Omnidawn, 2022). Following her prior English-language collections (she alsohas three collections published in Polish) Strata (Emergency Press, 2009;Omnidawn, 2018),

Contraband of Hoopoe

(Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here] and

Of Annunciations

(Omnidawn, 2017) [see my review of such here], Yours, Purple Gallinule is a book of birds, illnesses and depictions;a book of vertigo, pneumonia, diagnoses and mental aviaries, as well as avariety of temporal spaces. “In the meantime,” she writes, as part of the poem “TinyThroat Diagnoses,” “the larks rolled like scrolls around the pins of their /own laughter. What were they laughing about? They were simply / disciples ofjoy.” There is an opening of time beyond what we know into the knowledge ofbirds, from Hildegard of Bingen to Thomas Jefferson, and translations from theMiddle Ages to the narrator’s “80-year-old dad [who] visits from his nativecountry.” (“Acts of Exile”).Tospeak of birds, at least in Chrusciel’s hands, is to speak of perpetual memoryand endurance through the complex and woven structures of fragment, short bursts,diagnoses, declarations and documentation. The poems of Yours, PurpleGallinule offer a collection that echoes John James Audobon’s Birds ofAmerica (1827-1838), but if birds were studied as a way to examine, also,the intellectual, ecological and emotional healthy of all life on earth,centred around that binary of birds and human. To heal the world one must firstarticulate the symptoms, in order to diagnose the illness. And, one might ask,are Chrusciel’s narrators the birds themselves? As the poem “And not to spill asingle grain” ends:

Like the centrifugalleaps

of my mothers neurons

make her grasp the inscape

of things.

One needs to be an oracle

to hear an oracle.

June 19, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Beatrice Szymkowiak

BeatriceSzymkowiak

is aFrench-American writer and scholar. She graduated with an MFA in CreativeWriting from the Institute of American Indian Arts and a PhD inEnglish/Creative Writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is the authorof Red Zone (Finishing Line Press, 2018), a poetry chapbook, aswell as the winner of the 2017 OmniDawn Single Poem Broadside Contest, and therecipient of the 2022 Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry for her full-lengthcollection

B/RDS

, published by the University of Utah Press in 2023. Herwork also has appeared in numerous poetry magazines, including TheBerkeley Review, Terrain.org, The Portland Review, OmniVerse, TheSouthern Humanities Review, and many others.

BeatriceSzymkowiak

is aFrench-American writer and scholar. She graduated with an MFA in CreativeWriting from the Institute of American Indian Arts and a PhD inEnglish/Creative Writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is the authorof Red Zone (Finishing Line Press, 2018), a poetry chapbook, aswell as the winner of the 2017 OmniDawn Single Poem Broadside Contest, and therecipient of the 2022 Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry for her full-lengthcollection

B/RDS

, published by the University of Utah Press in 2023. Herwork also has appeared in numerous poetry magazines, including TheBerkeley Review, Terrain.org, The Portland Review, OmniVerse, TheSouthern Humanities Review, and many others.1 - How did your firstbook or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

The publication of my first chapbook RedZone was definitely a moral poetry boost! Being a writer means dealing witha lot of rejections, so every publication is a celebration and anencouragement!

Red Zone and my full-lengthbook B/RDS are located on the same ecological axis, and belong to thesame investigative project into the roots and consequences of the Anthropocene:Red Zone through the ecologically devastated lands of WWI, and B/RDS throughthe ecologically shattered skies of North America. Both are experimental andintersect history and science. However, while Red Zone plays with someexternal texts, B/RDS is bringing intertextuality to its full extent, asthe collection was written by erasing the entirety of Birds of America ––theiconic ornithological work of John James Audubon. B/RDS is alsopurposefully much more lyrical, as if a song.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

To some extent, I inherited myfather’s love for poetry. Also, what I always have loved about poetry, is itscapacity of dissent, against ideas but also against language itself ––both beingintertwined. Discovering Baudelaire and Rimbaud, two poetry dissenters, was adefining moment for me, as a poet. Baudelaire shattered the idea of beauty anddeveloped a symbolist aesthetic towards Modernism, while Rimbaud shatteredmetric versification towards the Modern free verse, and then, just abandonedpoetry!

I will not abandon poetry, however I alwayshave been interested in non-fiction too. Non-fiction finds its way in my poetrythrough preliminary research and/or through intertextuality.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It always takes me a while to start awriting project. I do a lot of thinking and research beforehand. For example,for B/RDS, I researched 19th century naturalists and exploredposthumanist philosophy and Object Oriented Ontology (OOO). The work ofphilosopher Timothy Morton (another dissenter!) who wrote the fascinating TheEcological Thought, was particularly influential. Morton’s work led me towonder what could be an ecological, lyrical pronoun, and to experiment with thepronoun “we.”

I still continue researching andreflecting, even after I start the project. I am rather a slow writer. I liketo spend time on a poem, which means that revisions are usually not extensive. ForB/RDS, the revisions were mostly focused on the prose poems and theorganization of the manuscript. The constraint that I had given myself on theerasure poems (keeping the order of words from the original text) made anyrevisions of these poems difficult, so I really spent time on their initialdraft.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I like to have a project ––to have arough direction towards which I write my poems. Then, overtime, I redirect,which may lead me to drop some poems or revise others for the coherence of theproject. For example, Red Zone was included in a much bigger project.However, I felt that the project was lacking coherence, so I decided to cull itand keep only the poems related to the ecological and historical impact of WWI.

Poems themselves often begin with animage, a moment, or a word collision. For example, the poem “Vimy” in RedZone comes from the paradoxical, bucolic sight of the sheep used to mow thegrass in the red zones of France. The red zones are former WWI battlefields prohibitedto the public because unexploded explosives and harmful chemicals, from leakingammunitions, riddle their soil. Hence the use of sheep to mow the grass.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I absolutely enjoy readings! I lovehow a poem becomes different once you voice it, where you recite it, or how the audience interprets it in so manyvarious ways. Because my poetry projects are research projects, I also like toprovide the background or context that help readers appreciate the poems morefully. It sometimes generates incredible discussions.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

My projects are conceived withinpostcolonial and posthumanist theoretical frameworks, and work towardsdeveloping a poetry of ecological awareness. I am particularly interested inenvironmental writing in the context of a critical investigation of settlercolonialism, extractivism, and ecological imperialism. For example, my poetrycollection B/RDS questions the disconnected approaches to themore-than-human world, through a lyrical erasure of Audubon’s iconic Birdsof America.

I am also fascinated by how the lyric“I” can withstand the interconnectedness of all beings, or translate theecological subject. What about a lyrical “we”?

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

In these present times and society, Isee writers as disrupters, inspirers, and/or awakeners. I write with the hopethat poetry can shift perspectives and ways of seeing and being in the world,towards a kinder and more sustainable future.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

My work always benefits from theperspectives of outside readers/editors. And when the feedback or theconversation become challenging, it means it hit an important question orpoint. For example the final lay-out of B/RDS only came about afterseveral discussions with poets Brenda Cárdenas and Kyce Bello, as well as mywife, who is always my first and bluntest editor. So, yes, feedback isessential and challenging. But, to some extent, if it weren’t challenging, itwould not be constructive!

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I had a mentor, Joan Kane, whosuggested that before workshopping a poem, somebody else read the poem back to itsauthor. Having somebody else read your own poem back to you, should be part ofany feedback process!

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see asthe appeal?

Moving between poetry and criticalessay allows me to approach a topic from different angles, so I do see them ascomplementary. I think they also influence each other. The critical prose mightaffect formal choices in my poems, while my poetry might support theoreticalcreativity.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I like to have a wide swath of time towrite, because I need to really dive into a poem, to spend time with it. So Ioften write on the weekend. If I am really deep in the mix of a project, mywriting might spill over into the week, whenever I have time. I don’t reallyhave a routine, except a cup of tea, that inevitably gets cold!

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

All my experiences somehow inform mywritings. For example, B/RDS was written during the covid lockdown, whichhad a direct influence on the collection ––the “cages” we were in, the birds wecould hear louder, the death toll, etc. However, to bring these experiences tothe surface, I sometimes need a catalyst: non-fiction and poetry books,podcast, documentary films, etc., and nature. So when I get stuck, I delve backinto these catalysts: grab a book or go for a hike!

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

The smell of bread, croissants, andbooks!

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature greatly influences my work. Iam particularly interested in the relationship between humanity and themore-than-human world, in its zones of conflict and confluence. I am lucky tolive in an area (Northern Arizona) with magnificent and vast expanses of wildlife, however inexorably encroached upon. For example, the poem “Out of theirBreast / as if” in B/RDS came from hikes in the forest around Flagstaff.

Other great influences are science, history,and art. My poetry is always in dialog with external fields.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

As mentioned earlier, the work ofphilosopher Timothy Morton has deeply influenced my poetry. My poetry is alsoindebted to the work of many poets: CD Wright, WS Merwin, Craig Santos Perez,Sherwin Bitsui, Joan Naviyuk Kane, James Thomas Stevens, Santee Frazier, Alice Oswald, M. NourbeSe Philip.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

I would love to work in collaborationwith an artist from another field, or a scientist. I can’t but wonder forexample, what a collaboration with a scientist researching whale songs in thedisrupted oceans could bring. I am fascinated by forms of expression, human orother!

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would have loved to be anenvironmental scientist, an archivist, a medievalist, a park ranger, or an astronomer!

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

I am passionate with language andbooks. How fascinating that we can dialogue across time and space throughwriting, or that words can sometimes change the course of history! Think aboutMartin Luther King’ s “I have a dream...”!

Also, I might have leaned towards writingbecause it is an activity I can practice anywhere, at my desk, by a river, ontop of a mountain, etc.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read was To2040 by Jorie Graham, and the last great movie I watched, Portrait of a Lady on Fire by Céline Sciamma.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I am working on a new poetry project and a non-fiction essay.

June 18, 2023

Amy Ching-Yan Lam, Baby Book

My review of

Baby Book

(Brick Books, 2023) by Amy Ching-Yan Lam is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of

Baby Book

(Brick Books, 2023) by Amy Ching-Yan Lam is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

June 17, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sabyasachi Nag

SabyasachiNag is theauthor of Uncharted (Mansfield Press, 2021) and two collections ofpoetry. His work has appeared in Black Fox Literary Magazine, CanadianLiterature, Grain, The Antigonish Review, and The Dalhousie Review. Heis a graduate of the Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University and the HumberSchool for Writers. He is currently an MFA candidate at the University ofBritish Columbia and the craft editor at

The Artisanal Writer

. He wasborn in Calcutta and lives in Mississauga, ON. www.sachiwrites.com.

SabyasachiNag is theauthor of Uncharted (Mansfield Press, 2021) and two collections ofpoetry. His work has appeared in Black Fox Literary Magazine, CanadianLiterature, Grain, The Antigonish Review, and The Dalhousie Review. Heis a graduate of the Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University and the HumberSchool for Writers. He is currently an MFA candidate at the University ofBritish Columbia and the craft editor at

The Artisanal Writer

. He wasborn in Calcutta and lives in Mississauga, ON. www.sachiwrites.com. 1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

Back in2006, when I published my first book I was uncertain – what did I write? Is itany good? With my recent title, Hands Like Trees (Ronsdale Press, 2023),I am still full of self-doubt. So, what changed? I think the nature ofuncertainty changed. Much like copper fresh out of the mill greens with time,acquires a patina, I found newer things to be anxious about. Luckily though, mymost recent work deals with similar questions as my first title – questionsabout identity; belonging; the true nature of heroism – hopefully the answersevolved with time.

2 - How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came topoetry for my love of language – the sound of words and the relationship ofsounds to meaning. Also, because poetry can fulfill you immediately; instantgratification keeps you hooked. During the early phases of my writing, thatinstant and guaranteed payback was vital for me to continue.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

Some formsare relatively easy for me, some are harder. I find short fiction, for instance,particularly hard. I take a long time to craft a story. My most recent title forinstance – it’s about 200 pages and includes nine stories, involving one familywhere characters repeat, yet it took me eight years from start to finish. Why?Because there are more than a dozen ways to write each one. Some writers take along time to write anything. I belong to that category for the most part.

Sometimes astory comes quickly and is pretty bad. Sometimes it comes quickly and is about okay.I think, for me, in general, everything cooks on low flame, as I like to takeeverything through the same alchemical process – something burns somewhere, youwatch it become ash, you dissolve it in water, extract the hard pieces from thedistill; mix them again and something else forms…and now something else burns,somewhere else and you start over.

My firstdrafts are rough. I rarely look at them again. I find note-taking as a processto get stuff off my brain. It’s a good method for my mind to stop wandering andpay attention. But I easily forget the notes I have taken. Good ideas usually stick,they never leave the brain.

4 - Where does a poem or work offiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

For me, poemscan start anywhere – a washed-up grocery list; a weird arrangement of shoes;late blooming tulips; the neighbour’s cat; the sound of a word; an image, realor imagined. Meanings inside poems have to be mined, so one can be courageousto start.

Stories,for me, usually start with an idea, not fully formed, but something with a headand a tail and I pickle it in a bell jar; let time work out the middle before Iapproach it again.

By thetime I start the actual writing, I usually know what it is going to be – astory or a novella, or a poem. Of course, each form requires a differentapproach. I don’t think of a “book” at first.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

I thinkit’s important to get out there and read. It’s a great way, if not the onlyway, to listen to the sound of one's writing. I don’t do that as regularly asI’d like. I intend to do it more often.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I liketheoretical constructs about writing to stay in the background, in the Jungianunknown. I don’t like to think of my writing as a response to anything otherthan my urge to string up words and hopefully make sense. I don’t carry apredetermined set of questions. I believe new questions emerge from the same oldquestions whether such questions were once answered or not.

7 – What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

I feel thewriter’s role in culture is to keep telling stories. Stories are so important,we couldn’t live without them for more than three minutes – the time it takesto be completely breathless. While telling stories, one may discover storiestend to repeat. So then, I think, the writer’s role is to keep finding newerways to tell the same set of stories.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I feelit’s essential. The editors I have had the chance to work with were all sogood. They often did for me what a good photographer does. They made thematerial look better; removed inert bits; made sure the balance between spaceand conflict is optimal; challenged me for clarity.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Show up.Writing will happen.

10 - How easy has it been for you tomove between genres (poetry to fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I like theidea of it because, first of all, it’s a great way to push something awaythat’s breaking the brain. It’s liberating. But I like to not overdo it as I ameasily distracted. If I don’t move between two ideas or two pieces of writing carefully,I fear, I might be so consumed by the new stuff, I might never come back to thething I was doing when I got deflected.

11 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

A typicalday for me starts with a cup of piping hot Darjeeling tea with 2 green cardamompods, 2 cloves, 3 black peppercorns, and a piece of cinnamon stick, the size ofmy thumb. Other than that, I don’t like routines.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When mywriting gets stalled I like to read. That’s where a good bit of my inspirationcomes from; some of it comes from films; and the rest comes from sitting by awindow, doing nothing. I also like to listen to podcasts about wasps andbutterflies.

13 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Home is acomplex idea for me and it means many things – identity, separation, alienation,rift, etc. Honestly, no one fragrance can capture the whole essence of the word‘home’. It means different things at different times and carries many differentfragrances.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I agree. And to add, Cormac McCarthy said "Books are made out ofbooks, the novel depends for its life on the novels that have beenwritten." I depend a lot on books. And sometimes on films, nature, music,science, religion, people, art, and a host of things that are too many to list.15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

Other writers important to my work are far too manyto list. I like returning to Tagore – who I listen more often that I read; Premchandwho I like to read in original; of course Borges who continues to amaze mealways; and Marquez, Cesares, Alice Munro, Atwood, John Williams, Don Delillo…it’s a long, long list. I easily forget the books I read and have toreread the same books many times over, only to realize I wasn’t payingattention the first time. I think, for artists, the boundary between life andart is so fluid, it’s impossible to recognize where ‘life’ starts and the ‘story’stops.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

LearnSpanish so I can find out what I missed in the translations of César Vallejo, Roberto Bolano; Neruda and Antonio Machado; Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa to name afew.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I couldpick any other occupation aside from writing, without a doubt, it would have tobe a farmer’s; I love the idea of small scale farming.

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

I thinkthat’s because it’s one of the few things I can do well.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

I finishedreading Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold last week,before that I read Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand. Last great film – Iwatch a lot of Bengali films – Kaushik Ganguly’s Nagarkirtan about genderidentity; Atanu Ghosh’s Mayurakshi about home, place, and time; GoutamGhose’s Shankhachil about borders and belonging; Indrashis Acharya’s Pupaabout euthanasia. I also like revisiting older films – Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, Michel Gondry’s EternalSunshine of the Spotless Mind, Christopher Nolan’s Memento to name afew.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I amcurrently working on a novel about a place that no longer exists, where I believeI had lived briefly, many years back, perhaps in a previous life.

June 16, 2023

Douglas Piccinnini, Beautiful, Safe & Free

There, in my mistake. I ampresent. The present

lifted over itself. A daylike grout

in the tiles suddenlybrittle suddenly breaking

down this pattern. A dateyou remember

smeared in the pages of acalendar.

That was pleasure once. Sure-fit,needled

existence and as thenerve brough forward

a yellow seam in thesilence. Silence thrust

its burning face to theglass—

that kind of domain. (“AWESTERN SKY”)

NewJersey poet Douglas Piccinnini’s [see his '12 or 20 questions' interview here] third published book and second full-lengthpoetry title, after

Blood Oboe

(Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2015), is

Beautiful,Safe & Free

(Palm Desert CA: New Books, 2023). The poems that make up Beautiful,Safe & Free, including the sequence previously published as thechapbook

A WESTERN SKY

(Greying Ghost, 2022) [see my review of such here], are constructed through notational accumulation: short lines, phrasesand sentences are clustered together to form shapes of meaning and purpose,composed along the frayed and dusty edges of American civilization. “day afterday mine silage / stuffs the animal vassal,” he writes, as part of the poem “CASHFOR GOLD.” Piccinnini composes his poem-clusters out of scraps and fragmentsaround placement and uncertainty, declaring where he, the narrator, is situatedin this montage of contemporary America, through all its devastation, contradictionand absolute beauty. “one is a mind in refrain shelving the days,” he writes,to open the poem “FLOWER SHIELD,” “as the throat of where you’ve been speaks //as the once between of boundaries / becomes particular to retain an abandon [.]”Piccinnini’s poems appear to skim across an endless surface but instead revealsuch depths as can’t be fathomed, offering echoes of Canadian poet Hugh Thomas throughhow the accumulation of ellipses can provide a perfect outline of anarticulated absence.

NewJersey poet Douglas Piccinnini’s [see his '12 or 20 questions' interview here] third published book and second full-lengthpoetry title, after

Blood Oboe

(Richmond CA: Omnidawn, 2015), is

Beautiful,Safe & Free

(Palm Desert CA: New Books, 2023). The poems that make up Beautiful,Safe & Free, including the sequence previously published as thechapbook

A WESTERN SKY

(Greying Ghost, 2022) [see my review of such here], are constructed through notational accumulation: short lines, phrasesand sentences are clustered together to form shapes of meaning and purpose,composed along the frayed and dusty edges of American civilization. “day afterday mine silage / stuffs the animal vassal,” he writes, as part of the poem “CASHFOR GOLD.” Piccinnini composes his poem-clusters out of scraps and fragmentsaround placement and uncertainty, declaring where he, the narrator, is situatedin this montage of contemporary America, through all its devastation, contradictionand absolute beauty. “one is a mind in refrain shelving the days,” he writes,to open the poem “FLOWER SHIELD,” “as the throat of where you’ve been speaks //as the once between of boundaries / becomes particular to retain an abandon [.]”Piccinnini’s poems appear to skim across an endless surface but instead revealsuch depths as can’t be fathomed, offering echoes of Canadian poet Hugh Thomas throughhow the accumulation of ellipses can provide a perfect outline of anarticulated absence.INTERROBANG

as if—stuttering

a percentage of glyphs

inflates you like aflower

in a loveable number

zeroed—whole—round

fit into you in what

like a splinter

milked from division

like an anthem jerks up—

to follow you everywhere

in every mask you slip on

to make meaning

June 15, 2023

Jake Byrne, Celebrate Pride with Lockheed Martin

My review of

Celebrate Pride with Lockheed Martin

(A Buckrider Book / Wolsak and Wynn, 2023) by Jake Byrne is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of

Celebrate Pride with Lockheed Martin

(A Buckrider Book / Wolsak and Wynn, 2023) by Jake Byrne is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.June 14, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jayson Keery

Jayson Keery is based in Western Massachusetts, where they completed their MFA in poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. They are the author of

The Choice is Real

(Metatron Press, 2023) and the chapbook

Astroturf

(o•blēk editions, 2022). They have been anthologized in Mundus Press’s Nocturnal Properties, Nightboat Books' We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics, and Pilot Press London's A Queer Anthology of Rage. They received the 2022 Metatron Press Prize for Rising Authors, selected by Fariha Róisín, and the 2021 Daniel and Merrily Glosband MFA Fellowship, selected by Wendy Xu. A complete list of publications, awards, and interviews live online at JaysonKeery.com.

Jayson Keery is based in Western Massachusetts, where they completed their MFA in poetry at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. They are the author of

The Choice is Real

(Metatron Press, 2023) and the chapbook

Astroturf

(o•blēk editions, 2022). They have been anthologized in Mundus Press’s Nocturnal Properties, Nightboat Books' We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics, and Pilot Press London's A Queer Anthology of Rage. They received the 2022 Metatron Press Prize for Rising Authors, selected by Fariha Róisín, and the 2021 Daniel and Merrily Glosband MFA Fellowship, selected by Wendy Xu. A complete list of publications, awards, and interviews live online at JaysonKeery.com.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Well, I just published my first book, The Choice Is Real (Metatron Press) so I’m currently in the ~ life-changing ~ process. What can I say? It feels good! And also a lot of the book’s content is intimate/ previously emotionally repressed, so knowing all that is out in the world is pretty charged. But the act of publicly sharing has the effect of normalizing the content. Maybe normalizing is the wrong word, but you catch my drift. Like, this all happened. Now it’s in a book. It’s fine.

My past writing was mainly comedic memoir, and I think you can see traces of that in my poetics. My work is still funny, but I also began working with grief and heavier topics.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

At a certain point, I realized that the comedic memoir I was writing wasn’t quite prose, so I felt an obligation to start studying poetry. You know, poetry is one of those arts where people think they can write it without reading it, and I didn’t want to be like that. I wanted to respect the community I was entering. I never expected to get so deep into it, but here I am. I’m obsessed!

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Oh, I take an insane amount of notes, then I transfer those notes to notecards and hang the notecards on the wall. I’m a very slow and physical writer. I need to write by hand and be able to visualize everything before I put it on the page. Sometimes a poem will pop right out of the notes, and I’ll only make minor edits. Other times I could be working on a poem for years.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The Choice Is Real started off as somewhat disparate poems that emerged from what I was feeling strongly about on any given day. Then themes appeared (choice, Disney, shit talk, etc), so I shaped poems around them.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Oh my god. I’d be lost without readings. I do them all the time. And I use them to grow in my practice. I take note of the audience's reactions. I make little marks on the page so that I can go home and edit the poems based on those reactions.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The Choice Is Real is in many ways trying the resist the question of choice in queerness. Queer and trans people are pressured into writing narratives that justify the idea that their queerness is not a choice, often leaning into the born-this-way assertion. My book is kind of like, Who cares? Why be so focused on justifying how we got here as opposed to focusing on the fact that we are here? The Choice Is Real also questions a lot of assumptions surrounding queer relationality in general. Lots of rude uprooting.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Big questions. Small answer: To me, the role of the writer is to help the reader locate aspects of themselves that they wouldn’t have otherwise discovered. When I’m reading, it’s all about relating or not relating, both of which help me to clarify myself. It’s all about me!

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love an outside editor. I take nothing personally and say no when I need to. But yeah, poetry can be a weird thing to edit so you really need someone who knows how to tap into your flow.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

The people worth loving are the people you don’t have to prove your worth to. I don’t even know who said this to me. (Maybe it was me!) My book is partially about this. If we feel like we’re having to prove ourselves, something’s wrong in the dynamic.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My routine fluctuates (and I like that it does) but I write every day. I feel like if you write every day for a few months, you start to feel off if you don’t write one day. I have the same relationship with running. I built the habit, and I go nuts without it!

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Books, of course! My writing gets stalled every single day and so every single day I pick up a book to get it flowing again. I’ll actually close my eyes and run my hands along the shelf until I feel heat and then pick that book to take inspiration from. I don’t know. It works.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of a dog’s ear.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’d say other than books, the art of conversation influences my work the most. I love paying close attention to people’s cadences and reactions. My poetry feels conversational to me, yeah.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Oh, I don’t even know where to begin, so I’ll shout out the writers who wrote my blurbs because I have the amazing fortune of knowing my favorite authors: Peter Gizzi, Ocean Vuong, Cameron Awkward-Rich, and CAConrad. I re-read their work all the time.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Travel literally anywhere. I’ve only ever lived in Massachusetts and don’t leave much. I like that about myself, but could stand to get out once in a while. Relatedly, I have this fantasy that a wealthy, mature Disney Dyke will take me to Disney World someday. So if that’s you and you’re out there, hit me up!

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I was an arts/events coordinator. A kind of glorified party planner, I guess. I love to throw a party! I’ve partied maybe a little too much in my time. :/

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

What I’m about to say is ironic because I wrote a book called The Choice Is Real, but it felt like I never had a choice but to write. It’s the only thing that regulates my nervous system. It’s the only thing I consistently feel compelled to do. I’ve never even cared whether or not I was good at it. I just do it all the time.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

A Queen In Bucks County by Kay Gabriel. I just re-watched Only Lovers Left Alive , directed by Jim Jarmusch.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m writing a series of letters to the men I’ve dated. I love how humiliating it feels!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 13, 2023

Michael Earl Craig, Iggy Horse

DRIVING HOME

Hundreds of finches inroad

resting, drinking frompuddles.

As I drive through them

they flutter up like sacred

soap-flakes eunuch moths

and I think of thegaudiness

of poetry.

Thefirst I’ve seen from Montana poet, as well as 2015-2017 Poet Laureate ofMontana, and ferrier Michael Earl Craig, the author of

Can You Relax in My House,

(Fence Books, 2002),

Yes, Master

(Fence Books, 2006),

Thin Kimono

(Wave Books, 2010),

Talkativeness

(Wave Books, 2014) and Woods and Clouds Interchangeable (Wave Books, 2019), is

Iggy Horse

(WaveBooks, 2023). The poems in Iggy Horse have a crispness to them, and thepoems hold echoes of elements one might also see in the works of Canadian poetsStephen Brockwell and Stuart Ross: a slight narrative distance, as the nebulousnarrators of each poem slowly form as each poem unfolds. As the poem “SPRINGTIMEIN HORSE COUNTRY” begins: “Lady Aberlin of the oarlocks. / Colonel Mustard inthe cherry trees. / Lady Aberlin with a custard, / Lady Aberlin in waiting. / ColonelMustard in the pantry with an almond.” Perhaps it is but a single voicethroughout, or perhaps the differences between them are there, and perhaps it doesn’t,in the end, actually matter. “One leg looks to have been swung / the way woodenlegs often were,” he writes, as part of the poem “PORTRAIT OF THE WRITER / MAXMERRMANN-HEISSE,” “up and over a real one. / Or even over a second one. / It’shard to tell because it’s Berlin / in the ‘20s, all those wooden legs / comingin from Rumburk / on the Spree, with good hinges / and shellac jobs that couldstop / a luthier in the street.”

Thefirst I’ve seen from Montana poet, as well as 2015-2017 Poet Laureate ofMontana, and ferrier Michael Earl Craig, the author of

Can You Relax in My House,

(Fence Books, 2002),

Yes, Master

(Fence Books, 2006),

Thin Kimono

(Wave Books, 2010),

Talkativeness

(Wave Books, 2014) and Woods and Clouds Interchangeable (Wave Books, 2019), is

Iggy Horse

(WaveBooks, 2023). The poems in Iggy Horse have a crispness to them, and thepoems hold echoes of elements one might also see in the works of Canadian poetsStephen Brockwell and Stuart Ross: a slight narrative distance, as the nebulousnarrators of each poem slowly form as each poem unfolds. As the poem “SPRINGTIMEIN HORSE COUNTRY” begins: “Lady Aberlin of the oarlocks. / Colonel Mustard inthe cherry trees. / Lady Aberlin with a custard, / Lady Aberlin in waiting. / ColonelMustard in the pantry with an almond.” Perhaps it is but a single voicethroughout, or perhaps the differences between them are there, and perhaps it doesn’t,in the end, actually matter. “One leg looks to have been swung / the way woodenlegs often were,” he writes, as part of the poem “PORTRAIT OF THE WRITER / MAXMERRMANN-HEISSE,” “up and over a real one. / Or even over a second one. / It’shard to tell because it’s Berlin / in the ‘20s, all those wooden legs / comingin from Rumburk / on the Spree, with good hinges / and shellac jobs that couldstop / a luthier in the street.” Composingpoems around voice, character and examination, Craig’s poems offer a kind offolksiness, composing intimate portraits of ghosts, individuals, landscapes, techniquesin medieval and modern paintings and other small moments. As the poem “CUBES OFICE CLINKING” reads in full: “A medicine ball sits / all blau-schwarz /crushing carpet. / An accolade arrives / like a cut flower, / like old friendsposing / as cadavers.” There is something curious about the simultaneous intimatedistance, even as Craig writes a moment directly from within. Either way, thereis clearly a realm of portraiture that Craig admires, attempting to capture hisown variation on the form through the details of text instead of oil. As thepoem “THE RED MITTEN” reads:

A school bus is followingme.

I stop walking, it stops.

I start again, it resumes.

The windows fogged.

This goes on for a while,

creeping across town.

I turn left, bus turnsleft.

I rub curb, bus rubs curb.

I stop again, it stops.

I take a step backward

and hear a gear grind.

A small red mitten wipes

the windshield. I jog

sideways like a sedated

horse dreaming and

bus doors open, let out

forty screaming children

swinging book bags.