Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 90

May 13, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cynthia Hogue

Cynthia Hogue’s new poetry collection is instead, it is dark (Red HenPress, 2023). Her ekphrastic Covid chapbook is entitled Contain (TramEditions 2022), and her new collaborative translation from the French of NicoleBrossard is Distantly (Omnidawn 2022). She served as Guest Editor forPoem-a-Day for September (2022), sponsored by the Academy of American Poets.Hogue was the inaugural Maxine and Jonathan Marshall Chair in Modern andContemporary Poetry at Arizona State University. She lives in Tucson.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book in the States was published about thirtyyears ago, The Woman in Red (Ahsahta Press, 1989). I also had a limited-editioncollection published by Whiteknights Press in the U.K. earlier in the decade, Wherethe Parallels Cross. Both books were published around the time that I wasworking on and finishing up a Ph.D. at the University of Arizona, and thanks tothem, I was offered my first job at the University of New Orleans as apoet-scholar. Now, that job changed my life.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry as a child. It's true, I alsowrote in other genres. I created a neighborhood newspaper when I was 10. Iwould assign the other children articles to write, but in fact, I wrote andproduced the only issue I was able to make by myself. In high school, a specialclass in creative writing was offered by my favorite English teacher, and inthat class, I wrote poetry. I attended Oberlin College in the year they offeredtheir first creative writing class in poetry, in the Experimental College. Itried other genres, but always returned to poetry. I had fun trying out fictionin New Orleans, but never finished anything I wrote. And I labored on amemoir-essay about living with someone, my first husband, with TourettesSyndrome, and also about the onset of Rheumatoid Arthritis in my mid-forties. Iwas pleased with those essays, but the first took me a decade to finish, sinceI didn't know what I was doing!

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Really depends on the project. In the last decade or so, asI explored drawing on research for book-length projects, my whole creativeprocess shifted from writing individual poems in short bursts to a slower,longer framework for completing a book, even if poems were arranged in series.I discovered a remarkable slave story in New Orleans right before I was leavingfor another position, the last slave to use the courts to sue for emancipationon the eve of the courts being closed to slaves with the signing of theFugitive Slave law. This slave, Cora Arsene, won her case. Dred Scott, in adifferent state but the same year, did not. Writing that long poem entailed adecade of research about Southern slave history (including the HaitianRevolution), and much much consideration of genre. The new collection, instead,it is dark, began with the shock of my husband's massive heartattack. He was born into occupied France, and my rather inchoateimpulse as I began the book was to honor his life by turning some of hismemories and dreams into poems. I conducted a lot of research and ended upinterviewing his extended family in France for this collection.

4 - Where does a poem or translation usually begin for you?Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project,or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For the translation of Nicole Brossard's Lointaines,which I published last year with Omnidawn as Distantly (with myco-translator, Sylvain Gallais), I eased into that serial project as if it werehot water, translating poems in the series here and there until we finallydecided to translated the whole book. With my last poetry collection, InJune the Labyrinth, I had been going on a sort of annual pilgrimage toChartres Cathedral every year for a decade when I decided to challenge myselfto write a book-length serial poem around the subject of the labyrinth. Iwanted to see if I could sustain a book-length project, but I adopted a loosenarrative structure to do so.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I rarely do solo readings, preferring group readings, andthey are certainly not part of my creative process, no.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I just returned fromthe wonderful New Orleans Poetry Festival, where I was on a panel called“Uncanny Activisms” (Lesley Wheeler’s terms for poetry in the tradition ofspells and prayers), so this is what I’ve been thinking about of late: Howcan/does poetry effect change? How does poetry matter (I actually neverquestion that it matters, being such an ancient art form, but realistically,how many people does it reach?) In his essay “On Poetry,” Velimir Khlebnikovraised the question of spells and incantations, magic words that are sometimes“beyonsense” in sacred or folk language. Great power is attributed to thesewords, and to magic spells, he says, because they are believed to contain magicand be capable of influencing our fate. Such poems and incantations go straightover the heads of leaders to Spirit. Khlebnikov said that “the magic in a wordremains magic even if it is not understood, and loses none of its power.” Thesedays, I am thinking very pointedly about the humane, inflected inspiritual and activist terms, in the hopes of changing, affecting, orraising consciousness. And sometimes, because I greatly admire many works indidactic tradition, I write poems with dryer, discursive statements inflectedby sonic lyricism.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

In the past, great writers could be cultural and politicalvoices, like a Yeats, Orwell, Pablo Neruda, Gore Vidal, Simone de Beauvoir, AlbertCamus. James Baldwin. Toni Morrison. Margaret Atwood today, Barbara Kingsolver,Ta-Nehisi Coates. The larger culture, I believe, benefits from the voices ofwriters and artists speaking in a more public arena, but now, with socialmedia, there is a levelling effect. A real democracy of voices. It can be hardto judge which voices are worth listening to. What writers offer is athoughtful, attentive, perhaps an ethical viewpoint. Many writers make theirliving teaching, and one by one, as students of literature and creative writinglearn the field, they are changed, at least potentially. Writers play the roleof mentor, sometimes guide, teaching students the skills to think forthemselves. Maybe that isn’t the role I think they should have, but I’ve cometo see it as important.

8—I’ve skipped that question, as I don’t have muchexperience with an outside editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Go where you are loved. Over the courseof a life, one receives much advice and counsel, sometimes requested andsometimes offered. This piece of advice is to be found in H.D.’s Trilogy, Ithink, and it is likely from the Bible. Once I took it in, during a dark timein my life, I never forgot it, and sometimes, I follow it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t see translating poetry as moving between genres.It’s certainly moving between languages, but in my experience, I feel I know myway around a poem that has been translated literally from another language—evenif I don’t immediately understand what the poet is doing. The strong appeal oftranslating other poets is the work enlarges your horizon, your language, andreplenishes and inspires the imagination.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Every day, I begin with some kind of writing. If I don’thave many interruptions, and especially, if I’m working on a longer project,I’ll usually write a poem or at least a draft. When I was writing my pandemicchapbook, CONTAIN, in the first months of lockdown, I had received a gorgeousvisual series from an artist I met at MacDowell, and I went into a kind ofaltered state of consciousness, meditating each day on one of the visual formsand writing an ekphrastic poem. Since there were no interruptions at that stageof the pandemic lockdown, I wrote 40 poems in 40 days. Very unusual for me, butthen the circumstances were intense and extraordinary.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I turn to poetry, reading some or many of the books piledon floor and desk, and I turn to nature.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilacs.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

As mentioned earlier, visual art (in the case of CONTAIN,the series by the remarkable Morgan O’Hara), sometimes history (as in the slavenarrative, “Ars Cora”), sometimes architecture (such as Chartres Cathedral,which has one of the few labyrinths that survived the French revolution), andin the beginning and for many years, and even now, nature.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dickinson and H.D., to some extent Marianne Moore, Stevens,Eliot, Gwendolyn Brooks, Muriel Rukeyser, Adrienne Rich, C.D. Wright, Forrest Gander, Lissa Wolsak, Nicole Brossard, Kathleen Fraser. Gary Snyder was veryimportant to me at one point, and Robert Bly, William Stafford. Nathaniel Mackey and Rachel Blau DuPlessis are amazing. I read deeply into Afaa Weaver,Alice Fulton, Brenda Hillman. Seamus Heaney’s North, his translation of Beowulf.Paul Celan. Those are some of the poets I return to. I am always open to prosethat is as beautifully written as poetry. I always read Barbara Kingsolver.There was a German writer I was much taken with, and she was beautifullytranslated: Christa Wolf. I am friends with a prose writer of great gifts,Karen Brennan (who is also a fine poet).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Actually, I went to Greece once many years ago, and I wouldlike to go back. The last time I saw an eastern autumn was ages ago, and I planto return to New York next fall to see the leaves.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I’d been planning on being a doctor. A scientist. Orperhaps a naturalist. I loved the outdoors. I began college as a biology major.But I loathed dissecting piglets and frogs and I fell in love with poetry. Mygrandmother had a gorgeous soprano, and had I inherited her voice, I might havetried to be an opera singer. I do love music.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I seemed to be good at it. I was otherwise very messed upwhen I was young, and writing poems was like my North Star.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver. Eo, one of the most painfulanimal rights films to watch, which I almost couldn’t finish watching.

20- What are you currently working on?

Ipublished three books over the last year, so I am in a fallow period. Gatheringmy thoughts, doing some readings and writing micro-essays.

rob,Thank you so much for these questions! This has been fun.

May 12, 2023

Margaret Ray, Good Grief, the Ground

It’s 2022. The world isending, but how fast? and for whom? and what do we have to pay to keep itaround for a little longer, just until we get that one last day with our kids, lasthour of rolling around in bed (with or without someone else in the bed), lastpancake, last walk, last book we love to read?

Good Grief, the Ground might be oneof those last books: light enough to come back to us, and heavy enough to staywith it. It certainly feels “like the end of something” to Margaret Ray, who is—orwrites as—a white, adult, American woman with Florida roots and a presence inNew Jersey now, a teacher still close to the epoch of fortunate teens, for whom“no one/ is dead yet,” teens full of hunger, “ready to go somewhere.” What do wedo with that hunger if we grow up, if we realize that some people are hungryfor us, that some people are never full, that we too have needs we mistake forwants and vice versa, that two contradictory things can be true? (StephanieBurt, “FOREWORD”)

Winnerof the 21st annual A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, as selected by Stephanie Burt, is New Jersey-based poet Margaret Ray’s full-length poetry debut,

Good Grief, the Ground

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a book that holdstogether as a selection of lyric narrative rolls and extended rushes. Offering portraitsof small town urban/suburban teenhood, Ray crafts urgent poems that strikethrough memory as they pour out sentence accumulations and lines that see no enduntil they finally, eventually, do. “I want to tell you about two events / thatform the cusp of a childhood:,” she writes, near the opening of the poem “ExpulsionLessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “One thing happened to me(alone), / and one happened (on TV) to America / after it happened (in private)to a pair // of people I’ll never meet.”

Winnerof the 21st annual A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, as selected by Stephanie Burt, is New Jersey-based poet Margaret Ray’s full-length poetry debut,

Good Grief, the Ground

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a book that holdstogether as a selection of lyric narrative rolls and extended rushes. Offering portraitsof small town urban/suburban teenhood, Ray crafts urgent poems that strikethrough memory as they pour out sentence accumulations and lines that see no enduntil they finally, eventually, do. “I want to tell you about two events / thatform the cusp of a childhood:,” she writes, near the opening of the poem “ExpulsionLessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “One thing happened to me(alone), / and one happened (on TV) to America / after it happened (in private)to a pair // of people I’ll never meet.” I’mintrigued at her poem-recollections and warnings that speak of the dangers anddrama of growing up and remaining, somehow, alive; writing on dark paths, darkcorner and the crevices of youth, violence and small towns. “Think of how skin/ glues itself back together after you slice your finger / chopping an onion,”she writes, as part of the poem “Enough,” “Not scar as metaphor no / how longit takes How quick the knife / Theproblem with children is that if you’re lucky // they grow up [.]” Or theincredibly striking “Reader, I Married Him,” riffing off the infamous quotefrom Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre (1847), that references youthfuldigression, hints at shades of domestic violence, and plays a number ofquick-turns and insights, including: “I threw the book at him and slammed / thedoor on the way out. In a poem I can leave / when I should have.” From the hardlessons of experience and distance, Ray writes generously of the hopes that youthmight hope and how inexperience can blindside even the sharpest mind. “It waslater, later,” she writes, as part of “Expulsion Lessons but Replace the Gardenwith a Swamp,” “once I turned the memory off its shelf / and turned it overagain, only / once I knew what he’d been doing / while he looked at me, that’s// when I was no longer a child.”

There’sa way that the structure of her collection feels akin to a sequence ofcalls-and-response, a back and forth of a section-cluster of poems followed bya single, stand-alone lyric, a second section-cluster followed by a further single,stand-alone lyric, and so on, offering a quartet of such pairings to make upthe larger structure of what becomes Good Grief, the Ground. The short pieces—“Wandais a Particle Physicist,” “Wanda Vibing,” “Wanda in the World” and “At a Distance”—almostexist as a kind of connective tissue that threads through the collection andholds it together into a larger narrative. As the first of these poems end: “Wandalooks back / at the traces her particles have left, // moving through a field.”It is interesting how the character “Wanda” somehow floats at a distance fromthe main action of the book, somehow tethered but unaffected, or even above,whatever may have occurred before. There is only what is happening now.

May 11, 2023

Spotlight series #85 : Eric Schmaltz

The eighty-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz.

The eighty-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon and New York-based poet Emmalea Russo.

The whole series can be found online here.

May 10, 2023

Emily Osborne, Safety Razor

“Sonatorrek”

Hardly can I hoist

my tongue or mount

song’s steelyard, forgeverse

in my mind’s foundry.

My tear-sea swamps

poetry, yet verse flows

like gore from a giant’s

throat onto Hel’s port.

The cruel sea hackedthrough

the fence of my kin.

A gap rots, unfilled,

Where my sons flourished.

I carried one son’scorpse.

I carry word-timber,

leafed in language,

from the speech-shrine.

I’mintrigued by the lyric density of the narratives in Bowen Island, British Columbia-based poet Emily Osborne’s full-length debut,

Safety Razor

(Guelph ON: GordonHill Press, 2023). “Thunder strums through my earliest memory / of family dinner.”she writes, to open the opening poem, “Infant amnesia,” “Summer in Ontario, //lightning pulses on the table. In the post- / voltaic hush, Dad tunes the radioto sirens, // tornado. We rush to the basement but / I’m leashed to myhighchair so Dad hauls // the hybrid downstairs, my bib scattering / remnantsin the dim.” She offers stories, memories and short scenes that unfold andunfurl with such careful precision, physicality and rootedness, composed withina present that includes moments across time and space to meet correspondingmoments of flesh and bone. As she writes as part of the poem “Diacritics”: “Yousaid my consonants split and replicate / like cells in tumours.” Writing onscrimshaws, dinosaur bones, runes, DNA, relativity, pollution, weather, balladsand folk tales, Osborne’s poems are centred on her narrative self, but also populatedwith different eras and perspectives, and the collection includes a selectionof poems that fold in a handful of her translations of Old Norse-Icelandic skaldicverse from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. I’m curious about her engagementwith such particular histories and old forms, and her author biography offersthat she “completed an MPhil and PhD at the University of Cambridge, in OldEnglish and Old Norse Literature.”

I’mintrigued by the lyric density of the narratives in Bowen Island, British Columbia-based poet Emily Osborne’s full-length debut,

Safety Razor

(Guelph ON: GordonHill Press, 2023). “Thunder strums through my earliest memory / of family dinner.”she writes, to open the opening poem, “Infant amnesia,” “Summer in Ontario, //lightning pulses on the table. In the post- / voltaic hush, Dad tunes the radioto sirens, // tornado. We rush to the basement but / I’m leashed to myhighchair so Dad hauls // the hybrid downstairs, my bib scattering / remnantsin the dim.” She offers stories, memories and short scenes that unfold andunfurl with such careful precision, physicality and rootedness, composed withina present that includes moments across time and space to meet correspondingmoments of flesh and bone. As she writes as part of the poem “Diacritics”: “Yousaid my consonants split and replicate / like cells in tumours.” Writing onscrimshaws, dinosaur bones, runes, DNA, relativity, pollution, weather, balladsand folk tales, Osborne’s poems are centred on her narrative self, but also populatedwith different eras and perspectives, and the collection includes a selectionof poems that fold in a handful of her translations of Old Norse-Icelandic skaldicverse from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. I’m curious about her engagementwith such particular histories and old forms, and her author biography offersthat she “completed an MPhil and PhD at the University of Cambridge, in OldEnglish and Old Norse Literature.”

“Verse making”

Goddess of therune-carved mead mug,

I’ve smoothed the prow ofthis song-ship.

Lovely lady, tree whocarries cups,

I deftly ply my tongue,the lathe of poems.

Organizedinto three sections—“FIRST CUTS,” “BARE BONES” and “FLESH MEETS”—the poems of SafetyRazor are infused with a density and a depth, and there is an attentivenessand a precision to Osborne’s lyrics that is quite striking, setting words downwith the deliberateness of letters carved directly into stone. “Art is youngerthan dirt,” the poem “Scrimshaw” ends, “only / as old as petroglyphs coating /earth’s aortas: […]” As well, I’m always intrigued by writers who are theoffspring of other writers [see my recent Touch the Donkey interviewwith Victoria, British Columbia poet Hilary Clark, in which she responds to aquestion around the work of her son, Winnipeg poet Julian Day], and I recentlyfound out that Osborne’s mother, Mary Willis, is the author of the poetrytitles Under this World's Green Arches (1977) and Earth’s Only Light(1981), both of which appeared through the Fiddlehead Poetry Book series. I wouldbe curious to know what echoes might have come through Osborne’s work from hermother, impossible to know for certain without knowing her mother’s work, or ifthere is any overt influence at all. “What else can I give my sons,” shewrites, as part of “Heirlooms,” “from my mother but pale eyes and stories?”

Eitherway, this is a collection that is fully aware of roots that span distances vastand intimate, moving in a myriad of directions, and even further, as thecollection closes with a small cluster of poems on new parenting. “Oh my son,”she writes, as part of “Labour, Eastertime 2019,” “from where did you come? /It’s true I didn’t see you until the curtain / lifted. But other hands are alwaysfirst // to catch, pull, hold you. Alone / I feed you, while the postnatal /room’s analog snips through sleep.” Razor Safety is a collection aware oftethers and tendrils, aware of what holds and where she reaches, seeking out andacknowledging a plethora of connections and connective tissue, no matter thedistances. Or, as she writes to close the poem “20-week scan”:

On these tones yourfather and I coast

through winter, foregoforeign travel,

speak of you. His basscaroms images,

half accurate perhaps. Afterthe first

made-up years, our wordsstatic back

until we’re parent shipsprojecting signals,

hoping you’ll echo. The biggeryou grow,

the less we know you’veheard us

our sonar broken

on open ocean

May 9, 2023

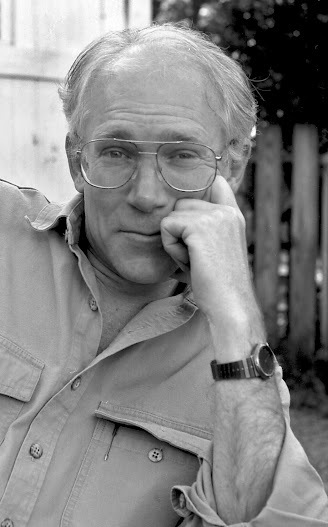

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Robert Bringhurst

Robert Bringhurst winner of the Lieutenant Governor’s Awardfor Literary Excellence and former Guggenheim Fellow in poetry, trainedinitially in the sciences at MIT but has made his career in the humanities. Heis also an officer of the Order of Canada and the recipient of two honorarydoctorates. He lives on Quadra Island, BC.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Writingbooks is like putting one foot in front of the other. It hasn’t changed mylife; it’s been my life. Not doing itwould have changed me quite a bit, or so I imagine – but I can’t tell youexactly how, since in fact that didn’t happen.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

Therewas never any question. Even in the beginning, when I really didn’t have a cluewhat poetry was, I was pulled in that direction. I’ve written a lot ofnonfiction in my life, and that’s what pays the rent, but poetry came first,and comes first, because it is first.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Ican’t tell you how or when anything starts. I’m always looking in the otherdirection when it happens. I don’t guess anything would start if I were standing over it watching. It’s clearly abiological process, but it often feels more geological: slower than molasses,with inexplicable, unpredictable sudden lurches, like spring floods and mudslides.Scott Fitzgerald said all good writing is swimming under water and holding yourbreath. Maybe so. For me, it’s more like trying to get my head out of thetorrent often enough to keep on breathing. Yet there’s no sensation of speed.That’s what I mean by geological.

4 - Where does a poem or work of translation usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Booksgrow like trees. They start in the ground. I’ve written the odd piece forperiodicals, and I’ve worked – this was decades ago – for both daily and weeklypapers. There are people who do that kind of writing brilliantly; I don’t.Books are what make sense to me. I like, and need, their glacial sense of time.But trees start as seedlings, not as trees, and books don’t start as books; theystart as a fragile mouthful of words.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readingsfor me are a vital part of the editing and revision process. That’s because Ihear the poem differently when I’m reading it in public than when I’m readingit to myself. If I were in charge, most readings would be scheduled in themonth or two before a book goes to press rather than after it’s been published.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

Ihave no theoretical concerns.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Thereare many kinds of writers, serving lots of different roles. But when a cultureis disintegrating, as ours is, most writers are going to play their roles,whatever they are, on a pretty small stage. Some will find their audience in asingle town or a single archipelago. For others, it might be an equally smallnumber of people scattered all over the globe. If a role in the larger culturewere what I wanted most, I’d have a better chance now as a demagogue than as awriter. That’s too steep a price to pay.

Wealways used to console ourselves by saying the best writers have their impactafter they’re dead – and that was in fact partially true for 2,500 or 3,000years. Now it’s a fantasy: the literary counterpart of the tooth fairy andSanta Claus.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Everywriter needs an editor, but not all writers need the same editor, and not justany editor will do. Great publishers have a knack for making matches betweeneditors and writers. It seems to me great editors are even scarcer than greatwriters, and great publishers are scarcer than great editors. On the whole, nevertheless,I’ve been lucky.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Shut up and listen. Or to put itmore politely, Pay attention.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to non-fiction to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ittook me a long time to learn to write half-decent poetry, and even longer tolearn to write half-decent prose. Translation helped, on both fronts. Beingable to move from one to another is just as important to me as being able to gofor a walk. It’s a way of keeping fit and rounding out my education.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Iwork all the time – waking and sleeping, walking and sitting, writing and notwriting. But the thing I most want, first thing in the morning, is just to beleft alone so I can find out what I’ve learned since the morning before.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Ilive in the country where there are always things to do. I don’t mean there arealways amusements and distractions; I mean there is always broken stuff to befixed, half-built stuff to be finished, there’s trail maintenance to do and aforest to be cared for. When I don’t have anything brilliant to say to a pieceof paper, I do carpentry or typography or forestry, or I put on my boots andhead up the trail. Or if all else fails, I go read a book.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Nofragrance really, but quite a few sounds. The sound of ravens talking, and oftree frogs singing, and of nighthawks diving, pileated woodpeckers beatingtheir slow tempo, band-tailed pigeons cooing, juncos ticking, nuthatcheshonking their little horns.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

It’s true, David said that. Many others have said ittoo. But not all of them were saying the same thing. Some books, of course, arejust reactions or responses to other books, and the farther you travel in thatdirection, the thinner and slipperier the ice gets. It seems to me the bestbooks come from reality: from the attempt to say hello and thank youto reality. Even those books are related to other books – and to music,science, visual art, as you say. But “coming from” and “related to” or“benefiting from” are not the same.

It’s also true that more good books – and stringquartets and sonatas and sculptures and paintings – get made in healthycultures, where other such things are being made, and fewer get made in sickcultures, where goodness is more likely to get squished before it flowers.“Books come from books” could refer to that fact: the fact that good books aregood for each other. It could also mean – and this, I think, is how David meantit – that literature is basically self-referential, like social media. He and Idisagreed about that.

A lot of so-called literature (and music and scienceand visual art) is indeed fundamentally self-referential. And for that veryreason, it’s dispensable. The important work – in art and science alike – mightinclude a few self-referential echoes, but essentially it’s not about itself.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Allthe good writers and all the good books are important to me. But a lot of themost important “writers” for me are not writers at all. They’re oral poets,most of whom couldn’t read or write and never needed to.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Seehow this plays out: how this gruesome and beautiful species does itself in.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

WhenI was eight years old, living in Calgary, the guys who came up the alley once aweek with their garbage truck looked to me like the most interesting peoplearound, and maybe the happiest. So I wanted to be agarbage man. I still take an active interest in garbage. Some years later, Iwanted to be a percussionist, then a lutenist. In fact I was a working drummerfor a time, but I never worked as a lutenist, and the life of a back-upmusician wasn’t for me. Still, in a way I got my wish: I’ve been, likeeverybody else, a non-professional garbage man most of my life.

When I started university, I had in mind to become eithera physicist or an architect. In middle age, my chief regret was that I hadn’tmajored in biology.

Except for playing the lute, all these professionsseem to have changed quite a lot in the course of my lifetime. They’ve changedbecause society has changed. In North America, garbage collectors spend lesstime on the ground and more in their comfy air-conditioned cabs, with musicmachines plugged into their ears. And they don’t look as happy. Garbage itselfhas also changed. It’s now mostly plastic. And physicists now join teams andsit at computers hooked up to still bigger computers. Physics has changed,though physical reality hasn’t. But writing is still just writing, as playingthe lute is still playing the lute – a nice thing to do; very nice, but I’mbetter at writing.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

For one thing, speaking poetry, and composing it, isanother form – a subtle and quiet form – of percussion. That’s whatdistinguishes speaking from singing. The speaking voice is tuned to no specificpitch, and it isn’t tied to a metronome, but its syllables vary in pitch andintensity and duration, and they do this in patterns and increments, notarbitrarily. So the speaking voice can play the drums and talk at the sametime. That, for me, is a reason for writing.

Another quite wonderful thing about literature is,it’s low-tech. No supercomputers or fancy equipment required. No expensive anddelicate instruments either, apart from mind and voice and heart. Yet you canpeer into the universe by doing it. Really you can.

And another excellent thing is, it’s essentiallyprivate. No assistants or apprentices required, almost never any meetings toattend, and really not much time in public. Yet you can share whatever youlearn. And others can too. What could be better?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Thelast good book I read is the one Ijust finished: Annie Proulx’s Fen, Bog& Swamp. But you asked about greatbooks. That question has no answer. All the greatbooks I’ve ever read are books that I’m still reading. None of them is thelast. Nor could I tell you, at this late date, which was the first. As forgreat films, I just don’t know. I live in the boonies, where there are no movietheatres, and I spend too much time with computer screens as it is. I’d really ratherlook at a printed page. So, much as I love a good film, it’s been years since Isaw one.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Toomany things at once, but it’s bad luck to talk about what’s cooking.

[24March 2023, updated 17 April 2023]

May 8, 2023

Julia Cohen, Collateral Light

If your first assessmentof a lake is its perimeter

forego prayer for theface

Water slaps laps up eye-fauna

In which designated spacewould your trapped

door unfold? If I do not spark?

Double-edged pen a pile of piney breath

to defend or discard (“ISTARED AT YOUR CAMERA / & PROMPTLY DIED”)

I’vehad Chicago poet, interviewer and essayist Julia Cohen’s second poetry title,

CollateralLight

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2013) on a list of books I stillneeded to get my hands on for years, most likely since I caught her work in anissue of

Black Warrior Review

[see my review of such here] (further onthat list include titles by Jennifer Moxley and Paige Lewis, in case you werewondering), only recently managing to actually do just that thing. The poemsthat make up Collateral Light are set as small moments, words andphrases that pool and cluster, propelled by fire, syntax and rhythm; afinely-honed sequence of small fragments that accumulate and hold togetheragainst, around and through the spaces she’s set just as deliberately as any wordchoice. She composes pinpoints that shape and hesitate, hold and cluster acrossnarratives. “You happen // Here” she writes, as part of the title poem, “I amwatching bees / traverse your jeans // I bit the point / of the strawberry // Offto the left / I’m seeding // The light peels back / a ringing splint [.]”

I’vehad Chicago poet, interviewer and essayist Julia Cohen’s second poetry title,

CollateralLight

(Brooklyn NY: Brooklyn Arts Press, 2013) on a list of books I stillneeded to get my hands on for years, most likely since I caught her work in anissue of

Black Warrior Review

[see my review of such here] (further onthat list include titles by Jennifer Moxley and Paige Lewis, in case you werewondering), only recently managing to actually do just that thing. The poemsthat make up Collateral Light are set as small moments, words andphrases that pool and cluster, propelled by fire, syntax and rhythm; afinely-honed sequence of small fragments that accumulate and hold togetheragainst, around and through the spaces she’s set just as deliberately as any wordchoice. She composes pinpoints that shape and hesitate, hold and cluster acrossnarratives. “You happen // Here” she writes, as part of the title poem, “I amwatching bees / traverse your jeans // I bit the point / of the strawberry // Offto the left / I’m seeding // The light peels back / a ringing splint [.]”Setif five numbered sections, Cohen’s poems in Collateral Light are piercingand propulsive, sharp and articulate. “Damp & cylindrical,” she writes, toclose the opening poem, “NO ONE TOLD ME I WAS THE ARROW,” “I raised / a blackrooster / tipping / the color / of my red / heart’s name // I sharpen / mypoint // plunge / into a glass / of soil [.]” She manages to compose a sequenceof narratives built out of sketched-out words and images that tether against anotherwise jumble, making clear sense out of pinpricks. “Everything I do / isvery grainy,” she writes, as part of “THE ROOM DEFORMED THE SOUND OF IT,” “Mypixels / deflect arrows [.]” Composing short phrases that accumulate down thestretch of each page, there is something similar in the shape and structure ofmany of these poems to the work of the late Robert Creeley, offering eachphrase-line as a further step down a staircase, uncertain, exactly, where thepoem might finally land. “A formation of water wheels / A formation of organs,”she writes, as part of “THE PLACE WE WORRY ABOUT,” “Movement caught in the work[.]” There is something interesting, also, in how each section begins with a singlephrase set at the bottom of the page, almost offering a suggestion of tone ortemperament for the poems gathered within; a single line to be read across thebottom of each of these five section-pages as a progression of the book’s toneand purpose: “my face was curious,” “I can’t just sit here with feelings,” “Openthe invitation to anyone,” “Everything needs to be moved through” and “Let’sworship doubt.” And then, of course, the final poem in the collection, which isset after the final section and colophon, almost as an end-credit piece,suggesting a poem to simultaneously close and suggest where she might go next:

IT MOVES IN, IS NOTSTATIC

Abdomen domain

Where I store my arrows

Thisis the first of her books I’ve managed to see, having seen neither her debutfull-length poetry title Triggermoon Triggermoon (Black Lawrence Press, 2011), nor her lyric essays, IWAS NOT BORN (Noemi Press, 2014), so I am clearly and ridiculously behindon her work. What has the intervening decade brought to her work? Where is shenow? I suppose I should count myself fortunate she hasn’t been more productiveover the intervening years, although now that I’ve said it, I’ve begun toworry.

May 7, 2023

Matthew Hollett, Optic Nerve: poems

Roll Over

We didn’t learn theburned-out building had been a cinema

until the day they toreit down, but we squeezed into the crowd

to watch an excavator pulverizeit into popcorn. In the rubble

we dug slivers of filmlike mussels, blowing ash off newsreels, musicals,

porn. I uncoiled a stripof colour, a cartoon beagle spinning through

a wild blue yonder. He wasa runaway load of laundry, an adorable

ouroborus pinwheelinginto a yin-yang of yellow and brown,

balled up like yarn or ayoga instructor. By yo-yoing the filmstrip

on my finger, I trainedhim to somersault at half speed, or double,

and when I took him homehe curled up in a film canister. I clipped

the mangled ends from hisreel, so now when I take him out for a tumble

he isn’t scorched or tornwhen it ends. He just goes, like a bubble.

Afollow-up to the creative non-fiction and poetry title

Album Rock

(PortugalCove-St. Philip’s NL: Boulder Books, 2018) is St. John’s, Newfoundland poet Matthew Hollett’s full-length poetry debut,

Optic Nerve: poems

(Kingston ON:Brick Books, 2023). Through an assortment of first-person poems set in a lyricsimultaneously narrative and cinematic, Hollett offers a descriptively-thickand finely-honed intimate portrait of east coast space. “It took two of us tohaul the river out of its box / and wrangle its segments together likevertebrae / or slabs of sidewalk. As rivers go,” he writes, to open the poem “WatersAbove and Waters Below,” “this one had been / stepped in more than twice, itsleisurely ripples and eddies / scuffed with footprints from small armies / ofschoolkids.” Hollett works his lyric as a way of examining small moments oftime, comparable to how Michael Crummey wrote contemporary and historic Newfoundlandthrough his Passengers: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2022) [see my review of such here], or how Michael Goodfellow wrote his personal Lunenberg County,Nova Scotia through Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems (KentvilleNS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. One could say that all three of these poets aresimply following elements of Newfoundland-based poet and editor Don McKay [seemy review of his 2021 collection Lurch here], and that would be entirelycorrect, each writing their own small perceptions through carved lyric observations.Weighed down through the dark, there is significant and even pragmatic light inthese lines. “If you find yourself lost,” the poem “Coriolis Borealis” begins, “trynot to walk in circles. A forest / is an aura of revolving doors, every spruceor fir is / a celestial body that wants you in its orbit. For the first /twenty-four hours, you’d be wise to stay put.” Across his densely-packed OpticNerve, Hollett writes short moments and scenes, fully aware of thedifferences in seeing and perception, writing narratives many of which are centredin and around Halifax. “In Halifax it greets me like a gauntlet of bear traps.”he writes, to open the poem “Shipshape.” “Sidestepping swollen potholes onQuinpool, I pass a traffic island / with its mascara of snow, a bicycle wheelcrushed into a taco, / a bird’s next asquint with icicles.”

Afollow-up to the creative non-fiction and poetry title

Album Rock

(PortugalCove-St. Philip’s NL: Boulder Books, 2018) is St. John’s, Newfoundland poet Matthew Hollett’s full-length poetry debut,

Optic Nerve: poems

(Kingston ON:Brick Books, 2023). Through an assortment of first-person poems set in a lyricsimultaneously narrative and cinematic, Hollett offers a descriptively-thickand finely-honed intimate portrait of east coast space. “It took two of us tohaul the river out of its box / and wrangle its segments together likevertebrae / or slabs of sidewalk. As rivers go,” he writes, to open the poem “WatersAbove and Waters Below,” “this one had been / stepped in more than twice, itsleisurely ripples and eddies / scuffed with footprints from small armies / ofschoolkids.” Hollett works his lyric as a way of examining small moments oftime, comparable to how Michael Crummey wrote contemporary and historic Newfoundlandthrough his Passengers: Poems (Toronto ON: Anansi, 2022) [see my review of such here], or how Michael Goodfellow wrote his personal Lunenberg County,Nova Scotia through Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems (KentvilleNS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. One could say that all three of these poets aresimply following elements of Newfoundland-based poet and editor Don McKay [seemy review of his 2021 collection Lurch here], and that would be entirelycorrect, each writing their own small perceptions through carved lyric observations.Weighed down through the dark, there is significant and even pragmatic light inthese lines. “If you find yourself lost,” the poem “Coriolis Borealis” begins, “trynot to walk in circles. A forest / is an aura of revolving doors, every spruceor fir is / a celestial body that wants you in its orbit. For the first /twenty-four hours, you’d be wise to stay put.” Across his densely-packed OpticNerve, Hollett writes short moments and scenes, fully aware of thedifferences in seeing and perception, writing narratives many of which are centredin and around Halifax. “In Halifax it greets me like a gauntlet of bear traps.”he writes, to open the poem “Shipshape.” “Sidestepping swollen potholes onQuinpool, I pass a traffic island / with its mascara of snow, a bicycle wheelcrushed into a taco, / a bird’s next asquint with icicles.”

May 6, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michelle Syba

Michelle Syba’s

debut story collection

End Times

is out inMay from Freehand Books. Described by Meghan O’Gieblyn as full of “humanity,ferocity, and grace,” End Times is about people variously entangled withevangelical culture. It features a cast of characters that includes a hipstermegachurch pastor, a management consultant who ends up at Davos, a nurse whobelieves in faith healing, and quite a few Slavic immigrants.

Michelle Syba’s

debut story collection

End Times

is out inMay from Freehand Books. Described by Meghan O’Gieblyn as full of “humanity,ferocity, and grace,” End Times is about people variously entangled withevangelical culture. It features a cast of characters that includes a hipstermegachurch pastor, a management consultant who ends up at Davos, a nurse whobelieves in faith healing, and quite a few Slavic immigrants. Michelle grewup Pentecostal and left the faith in university, becoming a zealot forliterature and completing a PhD in English at Harvard. She lives in Montreal. Youcan follow her on twitter at @lit_zealot.

1 - How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

I’m stillamazed that some strangers in Alberta were willing to put time and money intomy stories. They’re no longer strangers, of course, but given most publishers’reluctance to accept short-fiction collections I remain awed by the generosityand guts of Kelsey Attard, Naomi Lewis, Deborah Willis, and Colby Clair Stolson.

As far as howthe stories in End Times compare with my previous short fiction, mosthave a stronger current of plot. The titular story was the first one I wrote inwhich the plot unfolded fairly organically, in a way that surprised me and alsofelt inevitable, per Aristotle’s handy guideline.

2 - How didyou come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I didn’t. J It has been a long, twisty route tofiction, after a period of writing academically about literature, hoping itwould scratch my creative itch, and then writing a few memoir essays. Aboveall, I came to fiction first as a reader, and my time in academia gave me the opportunityto read gobs of wonderful art.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

On the wholeI’m a slow writer. I prefer some preliminary rumination, in the form of notes(often just a phrase, a bit of dialogue, an image, etc.) scribbled in mynotebook or typed into my phone. I need to feel some inner pressure ornecessity to write the story, and that pressure takes time to build. I’m totallyopen to being a faster writer, but that message has not yet been received by mysubconscious!

4 - Wheredoes a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

In the case ofEnd Times, the titular story had a lot of energy in it. After I wroteit, I realized that I wanted to write a story about a McKinsey managementconsultant like the daughter in “End Times,” Katy. (That story became thenovella For What Shall It Profit a Man?) Then the homophobic elements in“End Times” made me want to write a story about a gay evangelical man, as akind of counterargument. Plus I wanted to write more stories about Czechimmigrants, a topic treated only glancingly in “End Times”; and then there was thesurge of the Christian Right from 2016 until 2020, and again in 2022, with theOttawa convoy protest. So there were a lot of lively little kernels in thatfirst story, enough for a book, it turned out.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ve done onlytwo readings. Each time I enjoyed it: it’s thrilling to witness people’sattention to your words, but needless to say, it’s not essential. What’s been essentialis feedback from my writing group.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

I wouldn’t saytheoretical concerns, but my work has questions and concerns, yes, absolutely.Despite having left Pentecostalism, I remain fascinated by people of faith. I’mcurious about what their faith makes possible for them, where it can take them,especially people with more precarious lives, such as immigrants and singlemothers.

During theperiod when I began to write in earnest, Trump was newly elected and the damagewrought by white evangelicals was on full display. My first feeling towards manywhite evangelicals who supported Trump was contempt, and that reactionunsettled me when it implicated people I loved. After a while my contempt grewtedious. I wanted to explore a fuller range of emotions and perceptions vis àvis evangelicals. Also, I had long felt that there were things secularpeople didn’t understand about evangelicals, and I wanted to explore some ofthose blind spots.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It’s fair tosay that the contemporary literary writer is pretty marginal within the largerculture.

What do Ithink the writer’s role should be? I struggle with this. I don’t even know whatthe larger culture is anymore. There’s a bunch of niches, a few of which I findeither stimulating or cozy. I think literature is still useful for people whoseek out complex expressions of human life, where there is space for ambiguityand ambivalence and the emotions or thoughts that make us doubt our own certitudes.After all, reading a good story is an experience of being surprised,recognizing that you didn’t understand a character or a situation as fully as youthought you did. A story turns the experience of uncertainty, which in life weusually dislike, into a pleasure. In a story, I can be delighted by uncertaintyand the eventual apprehension of my own ignorance. In this way, literature canbe a tiny countervailing force to the snappy strong opinions of social media.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

Essential! Ican never see my words the way another reader does, so once a story is fully draftedit’s a gift to hear what another reader who cares about literature experienced asthey read my words.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Write whatyou’d like to read.

10 – Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (journalism to short fiction toessays to critical prose to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

Very! It hasbeen a relief, in fact. When writing in one genre feels stalled (say, memoir),I can always switch to another (like fiction!), which feels fresh and exciting.

11 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

When I can, I writein the morning, though first I read for 20-30 minutes. I need to be reminded ofthe thrill of literature by someone else’s example. Also, there’s always asnack, even if I’ve just eaten breakfast. I never sit at a desk, always in aneasy chair or on a couch. It’s a fairly spoiled routine.

When I beganto write creatively in earnest, I realized that I would need to make theexperience pleasurable to build the necessary endurance to finish a project.Given the failure built into the writing life (as Stephen Marche has recently arguedin his exhilarating book On Writing and Failure), the experience ofwriting has to be enough. And once you get into it, it is.

12 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

Books! Istarted to write creatively because it didn’t feel like ‘enough’ to be areader. My faves are fairly canonical. Munro. Flannery O’Connor. George Eliot.Woolf. Also: Bohumil Hrabal, Rachel Cusk, Yiyun Li, J. M. Coetzee, Gogol.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Lynda Barryhas a great piece about how bad we are at identifying the smells of our ownhomes, which to us smell like nothing much. Probably the home with the mostdistinctive smell was my childhood home, which was above my mother’shealth-food store. It had that classic ‘small health-food store’ smell—notes ofchamomile, nettle, cinnamon, glycerin, freshly-ground peanut butter, and abunch of other spices and herbs.

14 - DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Nature is theclosest thing. As I get older I am consistently charmed by nature. The way Inow notice the texture of lichen on a tree or the swoop of a chickadee’s flighthas made its way into my work. During the pandemic I started foraging for mushroomson Mont Royal, and that activity oriented me towards decay and death inunexpected ways, resulting in the story “Matsutake.”

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Like manymiddle-aged people I have been drawn to meditation. Shunryu Suzuki and Pema Chödrönare the bomb!

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Garden. Infact I’ve just started this spring, but I haven’t really ‘done’ gardening yet.I am becoming an aficionado of worms.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I don’t know. Ifeel very absorbed by my current life.

18 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

As many peoplehave acknowledged, making art isn’t really a choice. It’s something I have todo to feel sane.

19 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

EdithWharton’s The Age of Innocence!!! Somehow I never got around to it ingrad school. The exploration of wealthy 1870s New York life, wry but above allprecise—oh the tyranny of pleasantness!—and the way the protagonist Archer’sinner life secretly threads itself through the niceties of that world, the wayshe fools himself about what he feels, it all feels so true even now.

Filmwise, I lovedThe Farewell, its mix of pathos and hilarity; and also the way itpresents the audience with a situation they might not agree with (a family lie)but invites them to stay with it and try to understand it.

20 - Whatare you currently working on?

Recently I’vereturned to personal essays. I suspect that I have a creativesystolic/diastolic system whereby I alternate between nonfiction and fiction.We’ll see!

May 5, 2023

Claire Schwartz, Civil Service

Orderly Conduct

who wrong your hands

who run up your lacyunderwear

who tailored your tongue

who danced for the patron

who didn’t masturbate forforty days

who detonated the bathbomb

whose free two-dayshipping

whose pomp and impostersyndrome

whose hearts and mines

who applauded theveterans boarding the plane

who hate-read the article

whose title increased

whose art war makes

who took the meetinganyway

whose question was reallymore of a comment

whose difference of opinion

whose yard sign believedin love

whose kitchen was furnishedwith titles from a bathhouse

who brunched about threadcount

whose good deed goes

I’dseen enough of American poet Claire Schwartz’s poems in journals to know thather debut, once it landed, would be impressive. The resulting collection, CivilService (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2022), is a book set less insections of poems than clusters, composed as an assemblage of lyric form, from pulled-apartsentence fragments to tight stanzas to the prose poem that speak to narrativesaround war, history and perseverance. “History is / the only road thatsurvives.” she writes, near the end of the poem “Letter by Letter.” This is acollection that begins with a gesture, self-declared—the short sequence “[Theoriginal gesture]”—and follows across six clusters, each of which begin with ashort interrogation, each of which are titled “Interrogation Room.” As thefirst of these read:

[AMIRA LOOKSAT THE WALL]

What is themeaning of life?

We enlarge itwith our grief.

Threadingthe fugitive Amira, a character that sits in a nether-space of disappearing andexisting, through the book’s framing, Civil Service is a book of echoes,writing trauma and geometry, memory and power, civility and devastation. “Isthis a town square or a cell?” the opening sequence offers. “Difference is themeaning you make. // The poem is an event. // The poem takes place. // Thatmakes the poem a geography.” Schwartz’s poems are delicate, descriptive and devastating,and her “interrogations” exist in a kind of nebulous and urgent dream-state,writing an incredibly powerful kind of confessional around what isfrustratingly and familiarly unfamiliar. “The distance between you and the waris your country.” she writes, as part of the extended “Lecture on ConfessionalPoetry,” “The war is your country. // You think of this as nuance. // That youthink about the war makes you human. // To be human is to endow lines withmeaning / and make others susceptible.”

May 4, 2023

Ongoing notes, early May 2023: Vera Hadzic + Cindy Juyoung Ok,

Mayalready? God sakes. But you saw the daily poems posted on the Chaudiere Books blog for National Poetry Month, yes? Our tenth annual list! If you go here, you can even see the full list with links of all the poems posted so far in the series, which is pretty cool. I mean, it is an awful lot.

Mayalready? God sakes. But you saw the daily poems posted on the Chaudiere Books blog for National Poetry Month, yes? Our tenth annual list! If you go here, you can even see the full list with links of all the poems posted so far in the series, which is pretty cool. I mean, it is an awful lot.Ottawa ON: It was good to finally see Ottawa poet Vera Hadzic’s [see my “six questions” interview with her here] debut chapbook, Fossils You Can Swallow (Proper Tales Press, 2023), published recently throughStuart Ross’ Proper Tales Press. There’s such a lovely clarity and unselfconsciousnessto Hadzic’s lines, enough that one might end up following those lines to some unexpectedand even dark places through a thread of surrealism. “The sound of your name onmy tongue / is sweet and secret and swollen with / the crackling of syllables,”she writes, to open the poem “Your Name on My Tongue.” Offering poems as narrative-thesesthat accumulate from one point to another, there’s an interesting sense ofHadzic carefully feeling her way through form, with some poems feeling a bit ofhesitation, while others, a kind of confident, subtle, stride. “The Atlantic isdtoo deep and salty / to drink, lady.” the poem “Atlantic Drainage” begins, “Youare going / to hurt yourself. I am always hurting / myself.”

soup chicken

my sky is an overturnedbowl

bowling is something I dowhen I’m desperate

desperate birds tuck inwings, torpedo windows

windows that haven’t beencleaned in ages

ages are numbers paintedover in grease

grease gathers in thecurve of the pan

pan, god of wilderness,sings into moss

moss grows like furacross the backs of my hands

hands I once dug with,unlike now

now I feel the slownessin my pulse

pulse, that’s what thesky does when it turns red

red like onions and warmorange soup

soup would be good rightabout now

now I’m hungry for a nicefull bowl

a bowl of sky soup, maybe

maybe just chicken soup

Brooklyn NY: I recently received a copy of Cindy Juyoung Ok’s chapbook House Work (ugly duckling presse, 2023). I hadn’t heard hername prior, but a quick online search offers that she “is a writer, an editor,and an educator. Her debut poetry collection, Ward Toward, won the 2023 Yale Younger Poets Prize.” There’s a really propulsive and lovely flow to herlyrics, one that rolls along long threads through line breaks and commas and flow.As the opening poem “The Five Room Dance,” begins: “In our search for aproportionate address we leak / out of bed as you stretch your books and I mine/ the frozen language for olding hands day by week. / I account for each sirenand you count the hips to sigh // for with the seam of open borders.” Her linearityis anything but straightforward, through a wordplay that aims straight but turnsand twists in delightful ways, offered as tweaks and tics, presenting suchwonderful, subtle movement. “Tracing the yard,” the poem continues, “the laceof leaves as why I write. Why I, right, frown / your side affects, the cadenceof the fact that stars: / a woman is a thing that absorbs.”

Herlines are searing, slippery; and her narratives offer a quickness that suggestsphrases working to simply fly by until one meets you, as is her purpose,deliberately head-on. “My country is broken,” she offers, to open “Moss andMarigold,” “is estranged, is trying, we write, / as though there is such amaterial as a country, as / though the landlord doesn’t charge rent for lifelived / outside the house. When it comes to survival there is no right // waybut there’s no wrong way either. The country is / a construction, with eachwriting becomes more made.” Her poems have such an ease to them but strike withsuch incredible force. Oh, I think I am very much looking forward to seeingthis full-length debut.