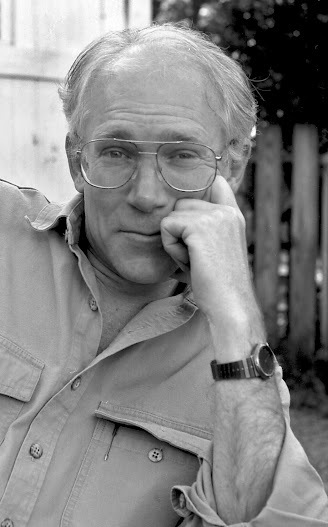

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Robert Bringhurst

Robert Bringhurst winner of the Lieutenant Governor’s Awardfor Literary Excellence and former Guggenheim Fellow in poetry, trainedinitially in the sciences at MIT but has made his career in the humanities. Heis also an officer of the Order of Canada and the recipient of two honorarydoctorates. He lives on Quadra Island, BC.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Writingbooks is like putting one foot in front of the other. It hasn’t changed mylife; it’s been my life. Not doing itwould have changed me quite a bit, or so I imagine – but I can’t tell youexactly how, since in fact that didn’t happen.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

Therewas never any question. Even in the beginning, when I really didn’t have a cluewhat poetry was, I was pulled in that direction. I’ve written a lot ofnonfiction in my life, and that’s what pays the rent, but poetry came first,and comes first, because it is first.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Ican’t tell you how or when anything starts. I’m always looking in the otherdirection when it happens. I don’t guess anything would start if I were standing over it watching. It’s clearly abiological process, but it often feels more geological: slower than molasses,with inexplicable, unpredictable sudden lurches, like spring floods and mudslides.Scott Fitzgerald said all good writing is swimming under water and holding yourbreath. Maybe so. For me, it’s more like trying to get my head out of thetorrent often enough to keep on breathing. Yet there’s no sensation of speed.That’s what I mean by geological.

4 - Where does a poem or work of translation usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Booksgrow like trees. They start in the ground. I’ve written the odd piece forperiodicals, and I’ve worked – this was decades ago – for both daily and weeklypapers. There are people who do that kind of writing brilliantly; I don’t.Books are what make sense to me. I like, and need, their glacial sense of time.But trees start as seedlings, not as trees, and books don’t start as books; theystart as a fragile mouthful of words.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readingsfor me are a vital part of the editing and revision process. That’s because Ihear the poem differently when I’m reading it in public than when I’m readingit to myself. If I were in charge, most readings would be scheduled in themonth or two before a book goes to press rather than after it’s been published.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

Ihave no theoretical concerns.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Thereare many kinds of writers, serving lots of different roles. But when a cultureis disintegrating, as ours is, most writers are going to play their roles,whatever they are, on a pretty small stage. Some will find their audience in asingle town or a single archipelago. For others, it might be an equally smallnumber of people scattered all over the globe. If a role in the larger culturewere what I wanted most, I’d have a better chance now as a demagogue than as awriter. That’s too steep a price to pay.

Wealways used to console ourselves by saying the best writers have their impactafter they’re dead – and that was in fact partially true for 2,500 or 3,000years. Now it’s a fantasy: the literary counterpart of the tooth fairy andSanta Claus.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Everywriter needs an editor, but not all writers need the same editor, and not justany editor will do. Great publishers have a knack for making matches betweeneditors and writers. It seems to me great editors are even scarcer than greatwriters, and great publishers are scarcer than great editors. On the whole, nevertheless,I’ve been lucky.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Shut up and listen. Or to put itmore politely, Pay attention.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to non-fiction to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ittook me a long time to learn to write half-decent poetry, and even longer tolearn to write half-decent prose. Translation helped, on both fronts. Beingable to move from one to another is just as important to me as being able to gofor a walk. It’s a way of keeping fit and rounding out my education.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Iwork all the time – waking and sleeping, walking and sitting, writing and notwriting. But the thing I most want, first thing in the morning, is just to beleft alone so I can find out what I’ve learned since the morning before.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Ilive in the country where there are always things to do. I don’t mean there arealways amusements and distractions; I mean there is always broken stuff to befixed, half-built stuff to be finished, there’s trail maintenance to do and aforest to be cared for. When I don’t have anything brilliant to say to a pieceof paper, I do carpentry or typography or forestry, or I put on my boots andhead up the trail. Or if all else fails, I go read a book.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Nofragrance really, but quite a few sounds. The sound of ravens talking, and oftree frogs singing, and of nighthawks diving, pileated woodpeckers beatingtheir slow tempo, band-tailed pigeons cooing, juncos ticking, nuthatcheshonking their little horns.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

It’s true, David said that. Many others have said ittoo. But not all of them were saying the same thing. Some books, of course, arejust reactions or responses to other books, and the farther you travel in thatdirection, the thinner and slipperier the ice gets. It seems to me the bestbooks come from reality: from the attempt to say hello and thank youto reality. Even those books are related to other books – and to music,science, visual art, as you say. But “coming from” and “related to” or“benefiting from” are not the same.

It’s also true that more good books – and stringquartets and sonatas and sculptures and paintings – get made in healthycultures, where other such things are being made, and fewer get made in sickcultures, where goodness is more likely to get squished before it flowers.“Books come from books” could refer to that fact: the fact that good books aregood for each other. It could also mean – and this, I think, is how David meantit – that literature is basically self-referential, like social media. He and Idisagreed about that.

A lot of so-called literature (and music and scienceand visual art) is indeed fundamentally self-referential. And for that veryreason, it’s dispensable. The important work – in art and science alike – mightinclude a few self-referential echoes, but essentially it’s not about itself.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Allthe good writers and all the good books are important to me. But a lot of themost important “writers” for me are not writers at all. They’re oral poets,most of whom couldn’t read or write and never needed to.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Seehow this plays out: how this gruesome and beautiful species does itself in.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

WhenI was eight years old, living in Calgary, the guys who came up the alley once aweek with their garbage truck looked to me like the most interesting peoplearound, and maybe the happiest. So I wanted to be agarbage man. I still take an active interest in garbage. Some years later, Iwanted to be a percussionist, then a lutenist. In fact I was a working drummerfor a time, but I never worked as a lutenist, and the life of a back-upmusician wasn’t for me. Still, in a way I got my wish: I’ve been, likeeverybody else, a non-professional garbage man most of my life.

When I started university, I had in mind to become eithera physicist or an architect. In middle age, my chief regret was that I hadn’tmajored in biology.

Except for playing the lute, all these professionsseem to have changed quite a lot in the course of my lifetime. They’ve changedbecause society has changed. In North America, garbage collectors spend lesstime on the ground and more in their comfy air-conditioned cabs, with musicmachines plugged into their ears. And they don’t look as happy. Garbage itselfhas also changed. It’s now mostly plastic. And physicists now join teams andsit at computers hooked up to still bigger computers. Physics has changed,though physical reality hasn’t. But writing is still just writing, as playingthe lute is still playing the lute – a nice thing to do; very nice, but I’mbetter at writing.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

For one thing, speaking poetry, and composing it, isanother form – a subtle and quiet form – of percussion. That’s whatdistinguishes speaking from singing. The speaking voice is tuned to no specificpitch, and it isn’t tied to a metronome, but its syllables vary in pitch andintensity and duration, and they do this in patterns and increments, notarbitrarily. So the speaking voice can play the drums and talk at the sametime. That, for me, is a reason for writing.

Another quite wonderful thing about literature is,it’s low-tech. No supercomputers or fancy equipment required. No expensive anddelicate instruments either, apart from mind and voice and heart. Yet you canpeer into the universe by doing it. Really you can.

And another excellent thing is, it’s essentiallyprivate. No assistants or apprentices required, almost never any meetings toattend, and really not much time in public. Yet you can share whatever youlearn. And others can too. What could be better?

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Thelast good book I read is the one Ijust finished: Annie Proulx’s Fen, Bog& Swamp. But you asked about greatbooks. That question has no answer. All the greatbooks I’ve ever read are books that I’m still reading. None of them is thelast. Nor could I tell you, at this late date, which was the first. As forgreat films, I just don’t know. I live in the boonies, where there are no movietheatres, and I spend too much time with computer screens as it is. I’d really ratherlook at a printed page. So, much as I love a good film, it’s been years since Isaw one.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Toomany things at once, but it’s bad luck to talk about what’s cooking.

[24March 2023, updated 17 April 2023]