Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 92

April 23, 2023

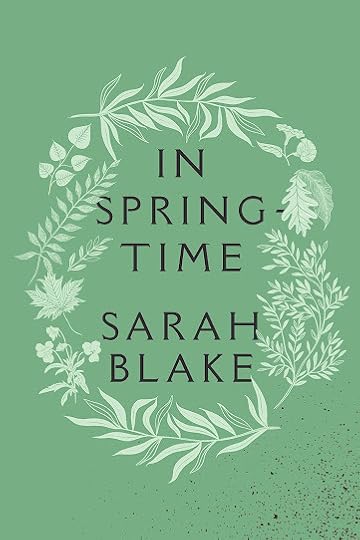

Sarah Blake, In Spring Time

12.

The bird spirit understandsthat her new form is more beautiful. Even

if it is less seen.

And she flies so easily. Minutesago she flew right under a bird of prey.

Hours ago she was abovethe clouds. The air was thin. The stars and

moon were close.

Her body has been singingto her from under the earth.

The song is sad, and whenshe sings, a whistling noise leaves her

torn stomach.

The mismatched notes ofher grieving body are the saddest of all.

Thethird poetry collection from American expatriate Sarah Blake, a poet andfiction writer currently living outside of London, England, is

In SpringTime

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), following on theheels of her

Mr. West

(Wesleyan University Press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and Let’s Not Live on Earth (Wesleyan University Press,2018) [see my review of such here]. In Spring Time is composed as a book-lengthsuite via a sequence of sixty numbered poems that loosely thread in, across andthrough the collection, grouped together across four numbered sections (“DAY 1,”“DAY 2,” “DAY 3” and “DAY 4”). Blake composes her meditative thread across ameandering of compressed time and the advent of spring, writing rebirth, renewaland death; she drifts across allegory and the specifics of foliage, wildanimals and even a horse. As part “31” offers: “She likes this. She likes you.She has no idea what she wants.”

Thethird poetry collection from American expatriate Sarah Blake, a poet andfiction writer currently living outside of London, England, is

In SpringTime

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), following on theheels of her

Mr. West

(Wesleyan University Press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and Let’s Not Live on Earth (Wesleyan University Press,2018) [see my review of such here]. In Spring Time is composed as a book-lengthsuite via a sequence of sixty numbered poems that loosely thread in, across andthrough the collection, grouped together across four numbered sections (“DAY 1,”“DAY 2,” “DAY 3” and “DAY 4”). Blake composes her meditative thread across ameandering of compressed time and the advent of spring, writing rebirth, renewaland death; she drifts across allegory and the specifics of foliage, wildanimals and even a horse. As part “31” offers: “She likes this. She likes you.She has no idea what she wants.”Offeringa poem that sits simultaneously within the body and the body of nature, Blake writesthe bounds of a season, following the details of movement and temporal space. “Who’sto say how far away the branches are?” she writes, as part of the poem “16.” in“DAY 2,” “Who’s to say how far / away the sky is? Who spends their time measuringdistances? // Is that an act of touching?” In Spring Time offers of andfrom spring, sketching moments through what appear as a kind of lyrical andphysical dream-state of horses, streams and daily meditations, attempting tofind her footing. As “20.” includes: “You’re glad the sun is going to spendtime every day shining on you. / This version of you that will outlast yourbody.”

April 22, 2023

Song & Dread, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek

My review of Otoniya J. Okot Bitek's

Song & Dread

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023) is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of Otoniya J. Okot Bitek's

Song & Dread

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023) is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.April 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tawanda Mulalu

Tawanda Mulalu [photo credit: Joseph Lee] was born in Gaborone, Botswana, in 1997. His first book,

Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die

, was selected by Susan Stewart for the Princeton Series of Contemporary Poets and is listed as a best poetry book of 2022 by The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The Washington Post. His chapbook Nearness was chosen as the winner of The New Delta Review 2020-21 Chapbook Contest, judged by Brandon Shimoda. Tawanda’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Brittle Paper, Lana Turner, Lolwe, The New England Review, The Paris Review, A Public Space and elsewhere. His writing has been supported by Brooklyn Poets, the Community of Writers, the New York State Summer Writers Institute and Tin House Books. Tawanda has also served as a Ledecky Fellow for Harvard Magazine and as the first Diversity and Inclusion Chair of The Harvard Advocate. He was recently awarded The Denver Quarterly’s 2022 Bin Ramke Prize for Poetry.

Tawanda Mulalu [photo credit: Joseph Lee] was born in Gaborone, Botswana, in 1997. His first book,

Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die

, was selected by Susan Stewart for the Princeton Series of Contemporary Poets and is listed as a best poetry book of 2022 by The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The Washington Post. His chapbook Nearness was chosen as the winner of The New Delta Review 2020-21 Chapbook Contest, judged by Brandon Shimoda. Tawanda’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Brittle Paper, Lana Turner, Lolwe, The New England Review, The Paris Review, A Public Space and elsewhere. His writing has been supported by Brooklyn Poets, the Community of Writers, the New York State Summer Writers Institute and Tin House Books. Tawanda has also served as a Ledecky Fellow for Harvard Magazine and as the first Diversity and Inclusion Chair of The Harvard Advocate. He was recently awarded The Denver Quarterly’s 2022 Bin Ramke Prize for Poetry. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Hmm. It hasn't actually changed much about my day-to-day life. I still have to labor and breathe and stuff. I feel marginally more confident in my ability to get published, but I don't actually feel more confident in my ability to write (actually, a little more horrified: I keep thinking of the poets I admire and what they did for their second book and, often, the jump in quality of writing from first to second book for those folks is absurdly large…) It's changed a few things socially. For my friends who believed I could be a writer, it was simple confirmation—which warms my heart, because I didn't feel that great about the whole endeavor (even though it was a dream of mine to get this thing out there). Those same friends say nice things about me at parties when I go with them, so I get cute introductions to new people (which is kind of helpful in New York for all sorts of reasons, both good and bad).

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I used to write a lot of personal essays, particularly in college. They were all hyper lyrical and suffered from a lack of cohesion and scattered, imagistic narratives. Eventually I gave up on being able to write something extended that could make 'sense' in the way that fiction and non-fiction tend to. So I ended up committing to the thing that made my brain feel safest. Poetry was, is, really good for the way I think: which tends to be deeply affective, wildly associative, etc. It's the only place where I don't have to feel ashamed for not having my thoughts altogether—and often, not having my thoughts altogether makes the poems more interesting (though the editing thereafter becomes a nightmare…) I’m suddenly worrying now because I’m remembering the much-quoted Auden phrase, “Poetry might be defined as the clear expression of mixed feelings.” Maybe let’s all focus on the “might be” part.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Honestly, I don't know. This is my first real (finished?) writing project. I wrote this book from a place of extended depression. A lot of it feels like it sort of just happened to (with?) me. I think, in writing terms, the book came relatively quickly (the first poems are from the fall of 2019, the last poems are from the summer of 2021). I have a strong feeling that the next project that I'd like to write will be long and torturous—which is fine. Totally fine. Genuinely fine. Yeah.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don't want it to be like this moving forward, but for this project anyways, the poems tended to come to me from places of feelings that weren't fun (pandemic depression, seasonal affective disorder, pretty-normal-in-retrospect heartbreak, persistent fears of racialized harm, diasporic longing, etc, etc—) I often wrote in a way that's kind of like listening to music when you need a pick-me-up. I was also fairly desperate—given my overly-large imaginations of the various failures I had accumulated during my time at Harvard—to write something to prove to myself that I could matter in some way (an insipid motivation for art, obviously). Some of the poems in the book are "project poems" that I wrote for the sake of filling in perceived gaps in the book (this is particularly true of 'Frenzy' which was basically an attempt to justify having the cover of the book as the cover of the book). For now, I have an idea for a second collection that involves writing several poems that sound like arias (even more so than in this one). We'll see how that actually ends up going. I’m pretty optimistic about it to be honest.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Not really? I read some of my poems to my friends sometimes when I was tipsy at parties or cuddling on a bed with them or whatever—all those things ended up being strangely helpful because I trust(ed) them. Also, reading poems out loud in writing workshops is also a little helpful because you get a sense of when the music is actually doing what you wanted it to do (or something worse, or something better). But mostly I read out loud to myself. I read out loud to myself a lot while writing the first book, and often did so when I wasn't feeling very happy in the vain (very vain) hope that the poems would somehow inevitably make me feel better. Which sometimes worked. Sometimes. Those were lucky moments that made me believe in the poems a lot more than was likely warranted (but I wouldn't have it any other way, really).

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I really need to get over Sylvia Plath but I have absolutely no intention of doing that anytime soon.

(I worry, like everyone else, that I'm not good enough. I mean, there shouldn't be a 'good enough' aspect of writing poetry in terms of the desire to write poetry. But I care a lot about writing something that outlives me. Not even for the sake of being remembered or whatever (that's what love and family and friendship is for). Mostly, I care about having poems outlive me because I think poems are beautiful and I want to be good enough to honor that beauty (also a little insipid, but, in this case: why not be? It's a maudlin, flowery, sentimental and astonishing art.))

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have no idea, sorry. I want to believe that poetry matters more than, I don't know, economics. It feels like that to me. But I don't have a good, universal theory regarding the importance of being a writer (tried that—failed horribly, got depressed again). I suppose we could acquiesce to pleasure: the idea that writing, like any other art form, when received or produced invokes pleasure, and that that pleasure is its own justification for writing. I actually don't believe that, and have always modestly resented that argument (yes, yes, pleasure need not be trivial, but the word itself sounds a little trivial, no?).

I guess I want writing and reading to feel more significant than whether or not it invokes strong feelings in me—even if that contradicts the fact that I do this precisely because it invokes strong feelings in me (and, hopefully, others). The best theory I have, at least for poetry, is that it feels like the closest representation of what it's like being a person, of what it's like being a mind in this world that I know and can personally understand (to the extent that poetry can be 'understood'). I think it's important to understand what it's like being a person because we have to live with ourselves and with each other. We can't escape our minds, the feelings within ourselves and others that our minds and other minds provoke. And, since we can't escape that, we should at least pay a great kindness and respect to the fact of our experiences. Poetry is a way of honoring each other, even if that honoring is so absurdly and blatantly materially useless.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Please edit my work, please please please. I love it when I submit stuff to journals and editors suggest I cut lines or re-arrange something or fix a poem in any way. shape or form that they desire. For one thing, if I don't like the advice, I can just ignore it and the work typically ends up getting published anyways. But—and here's the cool part—edit suggestions teach you how to read a poem even if you disagree with them. It's really fun seeing where other people's minds receive or reject ways that you wrote the lines of a poem. And it can also teach you how to read the poem, surprisingly, in its own terms, separately from how you thought you knew how to read it as the ‘original’ author. This is because you end up wondering to yourself: Why did I want to 'fix' the poem a certain way? What is the poem trying to do that is making my mind warrant that kind of intervention? Etc, etc.

I struggled a little because I was so used to taking edit suggestions from classmates and poetry professors and so on (I accepted, about, maybe half of whatever I got and revised my poems accordingly) But the editor for the series my book was published in, Susan Stewart, gave me, like, five edit suggestions and said "do what you want ,it's your book" which made me freak out for about two-plus months. I'm honestly not sure that anyone below the age of 30 should be allowed to publish a poem without editorial intervention (I'm obviously being facetious, and 30 is an arbitrary cut-off age…I'm just admitting to my own anxieties given that so many of my favorite poems that I've read recently have been written in a kind of "late" style that you basically only acquire after having been doing this for decades. I don't think it's me being too self-effacing to say that I trust that kind of learned beauty more than whatever it is that I end up cooking because I felt sad in college. Though, obvious counter-example: Rimbaud).

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don't laugh, but, genuinely, every time Naruto said "Believe it!", both in the manga and anime, he kept me going even up to my early twenties. I say this completely unironically. Perfect anxiety antidote.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a writing routine. Right now, a typical day begins with an alarm ringing "Wake-up!" and my body saying "No".

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Music. Always music.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I don't know. I didn't even know I didn't know. I haven't been home in three years.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music. Always music.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Sylvia Plath. Morgan Parker. T.S Eliot. F. Scott Fitzgerald. Robert Hayden. Okot p'Bitek. Chinua Achebe. Ngugi wa Thiong'o. Josh Bell. Jorie Graham. Jay Deshpande. Sharon Olds. Haruki Murakami. Vamika Sinha. Isabel Duarte-Grey. Emma de Lisle. Darius Atefat-Peckham. . Earl Sweatshirt. Childish Gambino. Kanye West. Adrianne Lenker. Robin Pecknold. Haolun Xu. Others more. Others more to come.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A good long poem.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wanted to be a theoretical physicist, but I failed at that. For the past year-and-a-half, I had been working as an investment researcher, which I wasn’t super good at either (I’ve recently resigned). I kind of wanted to try being a clinical psychologist at some point—but maybe later in my life? I was good at teaching, I could maybe try that again. Actually, no: I'd sing. If I could sing, I'd sing. Like in the Dorothea Lasky poem, 'Me and the Otters':

There is no poem that will bring back the dead17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

There is no poem that I could ever say that will

Arise the dead in their slumber, their faces gone

There is no poem or song I could sing to you

That would make me seem more beautiful

If there were such songs I would sing them

O they would hear me singing from here until dawn

At first, it was because I wanted to be smart. Then it was because I didn't really have much else going on (of course I did, we always do. People love us. We love them back.)

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Way of the Earth by Matthew Shenoda (still reading). Aftersun, directed by Charlotte Wells.

19 - What are you currently working on?

There's people I need to talk to.

April 20, 2023

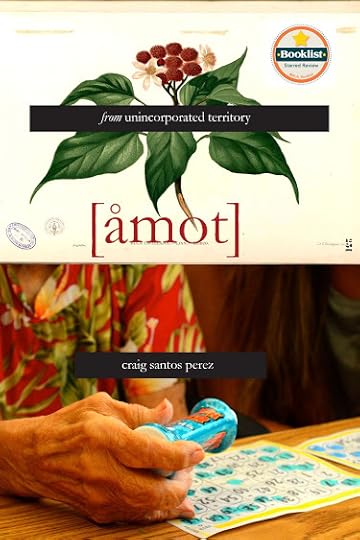

Craig Santos Perez, [åmot]

bingo is not indigenousto guam

yet here [we] are

in the air-conditionedcommunity center

next to the villagecatholic church

i help set the bingocards

& ink daubers on thecafeteria table

you sit in a wheelchair

like an ancient seaturtle

this has been your dailyritual

but the last time playedbingo with you

was 25 years ago when iwas a teenager

& still lived onisland

hasso’ when you won younever shouted

“bingo” too boastfully

when you lost you simplysaid

“agupa’ tomorrow we’llbe lucky”

here no onepunishes you

for speaking chamoru

here no warinvades & occupies life

no soldiers force you tobow (“ginen achiote”)

PoetCraig Santos Perez continues to expand his great long poem documenting, examiningand declaring his home territory through

from unincorporated territory [åmot]

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2023), the fifth book in his sequence both setas accumulation and ongoing thread, following

from unincorporated territory [hacha]

(Kaneohe HI: TinFish Press, 2008; updated edition, Omnidawn, 2017),

from unincorporated territory [saina]

(Omnidawn, 2010),

from unincorporated territory [guma’]

(Omnidawn, 2014) and

from unincorporated territory [lukao]

(Omnidawn, 2017). He is also the author of

Habitat Threshold

(Omnidawn,2020), although I haven’t seen that title, so I’m unaware how that book mightfit in the larger structure, if at all. As he described the larger project backin 2014 as part of his ’12 or 20 questions’ interview: “My first book was thefirst book-length excerpt of an ongoing story about my identity, culture, andfamily in the context of the history, politics, and ecology of my home(is)land,Guahan (Guam). My newest book is the third installment of the series, and itssubject matter focuses more directly on migration and militarization. In form,the newest book explores the poem-essay and the conceptual-collage poem.”

PoetCraig Santos Perez continues to expand his great long poem documenting, examiningand declaring his home territory through

from unincorporated territory [åmot]

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2023), the fifth book in his sequence both setas accumulation and ongoing thread, following

from unincorporated territory [hacha]

(Kaneohe HI: TinFish Press, 2008; updated edition, Omnidawn, 2017),

from unincorporated territory [saina]

(Omnidawn, 2010),

from unincorporated territory [guma’]

(Omnidawn, 2014) and

from unincorporated territory [lukao]

(Omnidawn, 2017). He is also the author of

Habitat Threshold

(Omnidawn,2020), although I haven’t seen that title, so I’m unaware how that book mightfit in the larger structure, if at all. As he described the larger project backin 2014 as part of his ’12 or 20 questions’ interview: “My first book was thefirst book-length excerpt of an ongoing story about my identity, culture, andfamily in the context of the history, politics, and ecology of my home(is)land,Guahan (Guam). My newest book is the third installment of the series, and itssubject matter focuses more directly on migration and militarization. In form,the newest book explores the poem-essay and the conceptual-collage poem.”Anindigenous Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guåhan (Guam) currently livingand teaching in Mānoa, Hawai‘i, unincorporated territory explores home,colonialism, ecological concerns and family, and where the indigenous culturemeets colonial influence, set in a geography that still holds in living memorythe stories of occupation by the Spanish, the Americans and the Japanese. An unincorporatedterritory of the United States, Guam is, much like Puerto Rico, politicallydisenfranchised, and unable to participate in the United States presidentialelections. How can a body, and a population, still be held and yet have no say?“today the military invites [us] / to collect plants & trees / within areasof litekyan / slated to be cleared / for a firing range,” he writes, early onin the collection. The poem continues, a bit further: “if [we] receive theirpermission / they’ll escort [us] to mark & claim / trees [we] wantdelivered / after removal // they call this ‘benevolence’ /// yet why / does itfeel / like a cruel / reaping [.]”

ginen during yourlifetime

for guam’s “greatestgeneration”

~

you survived

violent occupation

& the bloody march

to manenggon

you endured

the wounds of

our island stitched

by barbed wire fences

you said goodbye

to your children

as they donned uniforms

& deployed overseas

you prayed

as cancer diseased

half our relatives

you listened

as english endangered

i fino’ chamoru

& snakes silenced

native birds

o saina

i doubt if [we]

will ever receive

true reparations

or sovereignty over

our own nation

i can’t count

how many more

body bags will arrive

with touch boxes

& folded flags

i don’t know if

all your children

grandchildren

great-grandchildren

&great-great-grandchildren

will ever return

guma’

during your lifetime

to show

the abundance

that you

will be

survived by

Asa note from the publisher offers as part of the colophon: “‘Åmot’ is theChamoru word for ‘medicine,’ and commonly refers to medicinal plants.Traditional healers were know as yo’åmte, and they gathered åmot in the jungle,and recited chants and invocations of taotao’mona, or ancestral spirits, in thehealing process. Through experimental and visual poetry, Perez explores howstorytelling can become a symbolic form of åmot, offering healing from thetraumas of colonialism, militarism, migration, environmental injustice, and thedeath of elders [.]” The structure of Perez’s ongoing long poem feelscomparable to the late bpNichol’s nine-volume The Martyrology, or evenRobert Kroetsch’s “Field Notes,” both set as umbrella projects constructedthrough accumulated book-length structures, offering each volume as a furtherbrick, a further room, of something far larger and complex. Comparable, too, toPerez is how everything that Nichol and Kroetsch wrote fell into the larger structureof their ongoing projects, except, of course, for those projects that weredeliberately set beyond those particular boundaries. A rich and expansivecollection of fragments, fractals, family stories and archival material, fromunincorporated territory [åmot] holds elegies for the past and presentaround a land and people still in flux; of occupation and mourning, loss andfamily, flora and fauna, documenting the visual literacies of an island and itspeople, examining what erodes and what holds, and what might already be lost. Or,as he writes towards the end of the collection:

remember our people

scattered like stars

form new constellations

when [we] gather

hasso’ home is not simply a house

village or island

home is anarchipelago of belonging

April 19, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jon Riccio

Jon Riccio is the author of Agoreography and thechapbooks Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella and Eye, Romanov. He servesas the poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thank you, rob, for giving me the opportunity to discuss mywork. Also, for your stewardship of, literally, hundreds of writers. Happy 30thanniversary to above/ground press! Rachel Mindell’s rib and instep: honeyis how I became acquainted with the ways, large and small, in which “you’re[poetry’s] one in seven billion.”

My first book was the culmination of poems written over aseven-year period tied to my MFA and PhD degrees. Agoreography changedmy life in that I now have a ‘spokescollection’ for a poetry movement Ienvision, The Confurreal or Confessional Surrealism. Picture Anne Sexton,Robert Lowell, WD Snodgrass, and Sylvia Plath on a 1920s airship gabbing withJames Tate, Dean Young, Joyelle McSweeney, and Aimé Césaire. Whatevergerminates cerebrally and tonally in those quarters jumps to the present day.Vulnerability’s Petri-dish think tank, by any other.

My most recent work’s leaning more towards Surrealism than Confessional,with a peppering-in of where science fiction and occult speculation were about twenty-fiveyears prior. Infomercials, spacecrafts, little stargates that could.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I tried fiction. And I tried fiction again. Poetry’s a betterswim. Two books I bought, circa 2011/12ish, when they gave readings atKalamazoo Valley Community College, were Kay Ryan’s Elephant Rocks and PatriciaClark’s North of Wondering. Spending time with their poems after a threeyear-ish hiatus from reading any poetry was a way of quieting my brain,which at that point was immersed in all things OCD with frequent stops inagoraphobia. In August 2012, I joined a writing workshop mentored by John Rybicki. That September, I joined another, led by Traci Brimhall. Both gaveselflessly of themselves to the point where I felt ready to send my MFAapplication portfolio to six schools. The rest is University of Arizonahistory.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

The snails come to me for advice on how to slow things down.Glaciers have better responses to starter pistols. My first drafts areoverwritten, then pared anywhere from weeks to months before I consider a draftin submittable shape. In between, I have a quartet of readers who see the workat its newest. We encourage, we trade. Then, it goes to an online critique group.We trade, we encourage, we fawn over each other’s pets.

I love your question about copious notes. I had, at onepoint, a red notebook called Operation: Island, filled with lines frompoems that were beyond stalled. Many a revision benefitted from those Islandplug-ins. I should write an essay on the difference between rummage andsalvage. Vetted by mollusk.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Lately, my poems are coming from a two-month generativeproject I’ve described as The Cantos meets I Remember. I’m justnow revisiting the work with the intention of “what can I harvest?” Poemlengths vary: my chapbooks Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella and Eye,Romanov contained pieces on the shorter side. Agoreography haslonger work. Rare is the current poem where I go over a page.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I LOVE giving readings, in-person or Zoom, because theyremind me of the recitals I gave as a violist. You read your poems, see what fliesand what doesn’t (even though you thought it would in the revisions leading upto said reading). On the flipside, I LOVE organizing readings, whether duringschool days or now, in my work with the literary organization 1-Week Critique.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

I think about staying true (and nuancing) to my aestheticwithout completely alienating readers. I traffic in density and allusions noteveryone gets if they haven’t sponged pop culture (mainstream to obscure, peakwindow 1977 - 2000). The denser, allusion-heavier my poem, the more I’m apt toput it in couplets, which assist rather than mire. I’m worried about influence:do I innovate or mimic? That’s when I’m reminded of a phrase I hear at leastonce a month, “Nothing happens in a vacuum.” This calms me.

Currently asking myself: How, to paraphrase Lucie Brock-Broido, do I cultivate the patience of a taxidermist? Patience is myAchilles, yet I am at a point where patience is a life preserver in a sea ofsea changes, but gosh, is it slippery.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I’m interested in the linkages between poetry and thepedagogy I pass along to my students. Since June of 2021, I’ve been workingwith graduate-level writers at the University of West Alabama. I also teachcomposition and literature, so I look at reverse-engineering aspects (PoemProcess: what have you taught me and how can I channel it outwards?) We neverknow who is just one draft away from the decision to lead a life in letters (orrealizing the value of a life in letters). My eyes and ears are peeled, and ifthat’s my impact on larger culture, I’m fulfilled.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Three times where an outside editor has revolutionized myapproach to poetry: A) Dr. Charles Sumner, who served on my dissertationcommittee (so, a reader, but . . .), asked me seven or eight questions thattook my critical introduction from idea-spouting to The Confurreal’s inception.B) Dr. Jaydn DeWald, who as the editor at COMP: an interdisciplinary journal,had a similar method of question-oriented feedback, which helped me turn myrevised introduction of The Confurreal into a manifesto on The Confurreal,published as “The Florist’s Crossroads.” C) Andrea Watson, the founder of 3: A Taos Press and publisher of Agoreography, whose (wait, wait, let meguess) editorial line of questioning took the collection from what it was tothe book it became. Again, “Nothing happens in a vacuum.”

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

From Paul Tran’s “The Cave,” which appears in All theFlowers Kneeling (2022): “Keep going, the idea said.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I keep a log that records how many minutes I write each day.I aim for fifteen to a half hour, sometimes more. The day begins with either anhour of grading or reading. Before that, about fifteen minutes of personaljournaling.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Back-cover bios; past issues of Poets & Writers.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Meatballs frying in a spa of olive oil.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Classical music//soundtracks: Sibelius Violin Concerto ind minor, Khachaturian Violin Concerto in d minor, Tchaikovsky ViolinConcerto in D Major, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2 in g minor,Prokofiev Violin Sonata No. 1 in f minor, Vieuxtemps Violin ConcertoNo. 4 in d minor, Paganini Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major,Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 1 in f-sharp minor, Franck SymphonicVariations, Sibelius Symphony No. 1 in e minor, Symphony No. 2 inD Major, Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major// Psycho, HalloweenII, Halloween III, The Fog, Salem’s Lot, The StarWars Trilogy, Blade Runner, Alien.

Nature: Walks that last anywhere from one hour to eightyminutes.

Science: Any and all questions related to time travel andUFOs.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anne Sexton, everything she wrote, including the play Mercy Street; pedagogically, Graywolf’s The Art of Series has made all thedifference in how I approach classroom discussions about creative writing (DeanYoung’s The Art of Recklessness, Donald Revell’s The Art of Attention,Carl Phillips’s The Art of Daring); recent collections by Sandra Simonds, M Soledad Caballero, Jayme Ringleb, Tom Holmes, Bob Carr, Jessica Guzman, Charles Kell, Jaydn DeWald, Jonathan Minton; my Unexplained Mysteriescalendar.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Edit, distribute, and steward an anthology of writers whosework falls under the umbrella of The Confurreal. I have my solicitation listbut lack the funding to make it a reality.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

In no particular order, I would attempt: literary agent,manuscript editor, paranormal bookstore owner, Ufologist, craft servicescaterer (infomercials, television production sets). In my twenties, I had atwo-day interest in meteorology, then a few weeks where dairy farming wasentertained. Parallel universe Jon, he’s a concert violinist or world-renownedmathematician.

If not for writing, I would have stayed at my data-entry jobin a Michigan food bank.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In my best poetry self-excerpting voice: “I'm a writerbecause I ran out of zip codes to be fired in.” (“Parenting Wil Wheaton”).

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

DaMaris B. Hill’s 2019 poetry/prose collection, A Bound Woman Is A Dangerous Thing: The Incarceration of African American Women from Harriet Tubman to Sandra Bland. Cinema-wise, The Whale.

19 - What are you currently working on?

My stove burners are kettling student papers for a mythologyclass, essay drafts, submission screening at Fairy Tale Review,free-writing projects, and reaching out to poets for permission to write abouttheir work in my monthly craft articles at 1-Week Critique.

Thank you again, rob.

April 18, 2023

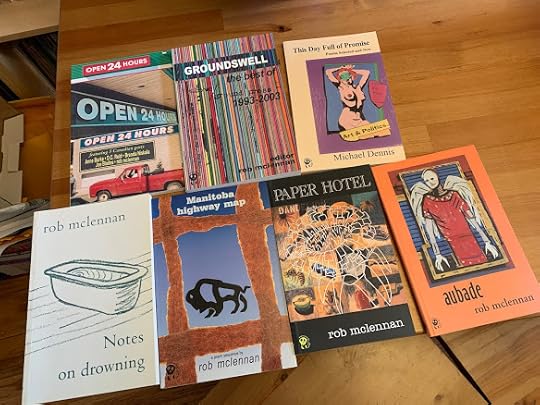

sale : rob's Broken Jaw Press titles,

I recently garnered a few mounds of books from Broken Jaw Press (see my obit for editor/publisher Joe Blades here), including a handful of my own early titles that Joe published, as well as a couple of other titles I was involved with as editor. If anyone is interested, I am offering copies for sale.

I recently garnered a few mounds of books from Broken Jaw Press (see my obit for editor/publisher Joe Blades here), including a handful of my own early titles that Joe published, as well as a couple of other titles I was involved with as editor. If anyone is interested, I am offering copies for sale.Notes on drowning (1998; my full-length debut!), paper hotel (2002) and aubade (2006) I'm offering for $7 each; Manitoba highway map (1999; my third trade collection) and the five poet anthology Open 24 Hours (1998; poems by myself, Brenda Niskala, Joe Blades, D.C. Reid and Anne Burke) for $5 each.

this day full of promise: new & selected poems by michael dennis (2002) that I edited and put through the cauldron books series that Broken Jaw published I can offer for $7 each as well. I'm very pleased to have a new stack of copies of GROUNDSWELL: best of above/ground press, 1993-2003 (2003), the anthology celebrating the first decade of the press, especially since this year is not only the thirtieth anniversary of the press, but Invisible Publishing is scheduled to produce the third 'best of' decade anthology this fall. I can offer copies of GROUNDSWELL for $15 each (it even includes a bibliography of the first ten years of the press!), although if you order 2 or more books, I'm willing to throw in a copy of Manitoba highway map gratis.

if interested, send funds via email or paypal to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com; if you are ordering a single book add $2 for Canadian orders, and $5 for orders to the United States : if you are ordering two or more books, add $5 for postage for Canadian orders, and $11 for the United States. for any orders beyond the boundaries of North America, send me an email and I can always attempt to figure out postage. I can even sign copies, if that is of interest. also, be sure to email if you have any questions.

Oh, and don't forget that I still have copies of the book of smaller (University of Calgary Press, 2022) and essays in the face of uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022) as well, yes? See the link here for information on those. And I've the final copies of my two novels with Mercury Press--white (2007) and missing persons (2009)--still available for $15 each. What a deal!

April 17, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Karen Enns

Karen Enns is the author of four books of poetry: Dislocations, Cloud Physics, winner of the Raymond Souster Award, Ordinary Hours, and That Other Beauty. She lives in Victoria, BritishColumbia.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book marked a commitment to poetry, to writing, thatwas already there, so it didn’t change my life in that sense, but having thepoems in print did make the commitment public, which adds a slightly differentperspective.

My most recent work reflects some of the same preoccupationsas the earlier poems but the structures are more variable. The pressure on theline has definitely changed over time and I’m more comfortable working with longerpoems.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I wrote poems when I was very young and then turned to musicfor a long time, but I was always drawn to the form, the condensation—whenreading, the possibility of being transported in just a few lines. Poetry’sobvious musical component was definitely an inducement.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

First drafts of poems often visually resemble their finalshape, in the sense that they already have a length of line and a rhythmic pitch,so to speak, but they don’t usually “appear” in any kind of final form. Theprocess is often slow, a chiselling away, but that working out of the lines andarcs, the modulations, is absorbing. It reminds me of learning a piece ofmusic.

I don’t usually make notes, but I’ve probably lost some goodideas along the way because of this.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I work on a poem, or sometimes several poems at once, withoutany sense of a longer book form. Much later, when I have a collection of files,I slowly begin to see the possibilities of a larger structure. It’s a bit likestanding on a dock watching for a boat to appear out of the fog.

A poem can begin in many ways, but there has to be arecognizable moment for me, a slipping into a different mode of seeing orhearing, with an emotional charge, that generates the impulse of the poem.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I write in solitude, so readings are not part of thecreative process itself, but they’re part of a broader cultural conversation ina public sphere, like concerts, plays, films, art exhibits, that is essential forartistic exchange. Everyone benefits from that dialogue. Having said all that,I do get nervous for readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I’m not conscious of trying to answer questions with my work.The searching is probably more crucial, not only for creative reasons, butalso—I like to think—because whatever the current questions may be, a sense ofopen-endedness can be transcending.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Absolutely, the writer has a role. I don’t know that it haschanged that much through history, although each era has its own particularchallenges. But writers often observe from the outskirts. They create a pause,a space, in which it’s possible to imagine other ways of seeing and thinking,other worlds.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s challenging to think hard about inconsistencies orweaknesses in your own work, or to question patterns you rely on, but theprocess is essential and broadening. And there is the possibility of developinga literary friendship with someone whose editorial work you trust and respect.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Some of the best advice appears in verse itself.Zagajewski’s “Try to praise the mutilated world” comes to mind.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write in the morning before the day’s distractions pileup.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Most of the time, it’s simply a matter of choosing whetherto push through or be patient while things settle, but bike rides and hikes arehelpful. I’m very fortunate to live near forests and coastlines.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

If I moved away from the west coast, I’m sure it would bethe scent of cedar when it rains, but to be back in Niagara again, on the farm,in a second, it’s the smell of turned-up soil in spring.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

I’d say all of the above have influenced my work at varioustimes.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

The writing community in and around Victoria is a strong,lively one, which has been important. Farther afield, the work of writers andthinkers responding to political crisis, violence, displacement, are animportant resource for thinking about the future, as well as looking back to myown family/cultural history.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Become fluent in German, my first language; learn Chopin’s Bminor Sonata; visit Ireland. The list is long.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

I worked as a classical pianist for a number of years, andstill teach, so I’ve had the opportunity to follow a path other than writing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

A love of reading.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

I recently read Walk the Blue Fields and SmallThings Like These by Claire Keegan, as well as a wonderful collection ofstories, Motley Stones, by Adalbert Stifter.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Short fiction.

April 16, 2023

today is Lady Aoife's seventh birthday,

April 15, 2023

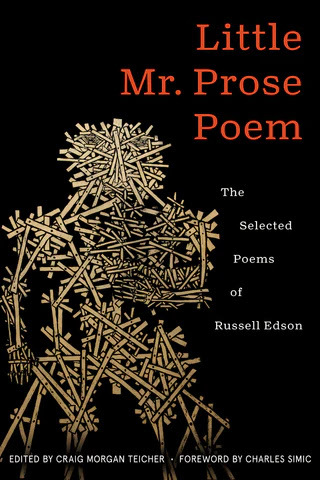

Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poems of Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher

Edson was one of thedefinitive practitioners of the contemporary American prose poem. Charles Simic,in his beautiful Foreword, says that no one has yet offered a convincingdefinition of prose poetry. Nonetheless, permit me to make an attempt. Is aprose poem just a poem with no line breaks? If so, what can prose sentences andparagraphs do for a poem that lines can’t? What is prose and what is poetry,and what are the supposed differences between them? The poet, critic, andtranslator Richard Howard, who was my graduate school mentor and friend, has awonderfully useful and precise maxim for describing the difference between poetryand prose: “verse reverses, prose proceeds.”

This concise and musicalphrase summarizes what I believe to be one of the central truths about thenature of these two forms of writing: though made of the same basic stuff—letters,words, punctuation—once they take their shapes, they are actually differentsubstances, like water and oil (though they do mix), or, perhaps, more likewater and wood. They are composed of the same elements, but those elements aredeployed so differently that the results can seem like distant cousins at best.

But what are they? First,we need a definition of “prose”: it’s the word on the street; the writingpeople talk in; the words on signs; and the stuff, beside images, that the Internetis made of. In itself, it’s not scary (though lots of it piled up, say, in abig, fat book, might be). Reading prose, you might not even realize you’rereading it. (“‘No, And’: Russell Edson’s Poetry of Contradiction,” Craig MorganTeicher)

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised?

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised? Soof course, I was curious to see a copy of Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poemsof Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher, with a Foreword by Charles Simic (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) land in my mailbox recently; perhapsthis collection might provide some sense of what it is I’d been missing, or atleast, not getting? Perhaps it is as simple as requiring the correct entrypoint in my reading. In my late twenties, after hearing from a variety of writersaround me on the brilliance of the work of Toronto poet David McFadden, thehalf-dozen titles I encountered weren’t providing me with any answers as to why,until I picked up a copy of his Governor General’s Award-shortlisted The Artof Darkness (McClelland and Stewart, 1984), a book that became my personalRosetta Stone for the since-late McFadden’s fifty years of publishing. With thatone title, all, including his brilliance, became abundantly and absolutely clear.

AsCharles Simic offers in his introduction: “Edson said that he wanted to write withoutdebt or obligation to any literary form or idea. What made him fond of prosepoetry, he claimed, is its awkwardness and its seeming lack of ambition. Themonster children of two incompatible strategies, the lyric and the narrative,they are playful and irreverent.” Little Mr. Prose Poem selects piecesfrom ten different collections produced during Edson’s life: The Very Thing ThatHappens (New Directions, 1964), What A Man Can See (The Jargon Society,1969), The Childhood of an Equestrian (Harper and Row, 1973), The ClamTheater (Wesleyan University Press, 1973), The Intuitive Journey (Harperand Row, 1976), The Reason Why the Closet Man Is Never Sad (WesleyanUniversity Press, 1977), The Wounded Breakfast (Wesleyan UniversityPress, 1985), The Tormented Mirror (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001),The Rooster’s Wife (BOA Editions, 2005) and See Jack (Universityof Pittsburgh Press, 2009). Given the final collection on this particular listemerged five years prior to the author’s death, one is left to wonder if therewere uncollected pieces or even an unfinished manuscript left behind after hedied? Did all of his pieces fall within the boundaries of his published books?

Thereare ways that Edson’s odd narratives, populated with fragments and layerings ofscenes and characters, feel akin to musings, constructed as narrativeaccumulations across the structure of the prose poem. And yet, there are times Iwonder how these are “prose poems” instead of being called, perhaps, “postcardfictions” or “flash fictions.” It would appear that an important element of Edson’sform is the way the narrratives turn between sentences: his sentencesaccumulate, but don’t necessarily form a straight line. There are elements ofthe surreal, but Edson is no surrealist; instead, he seems a realist who blurs andlayers his statements up against the impossible. I might not be able to hear aparticular music through Edson’s lines, but there certainly is a patterning; alayering, of image and idea, of narrative overlay, offering moments of introspectionas the poems throughout the collection become larger, more complex. As well,Edson’s poems seem to favour the ellipses, offering multiple openings butoffering no straightforward conclusions, easy or otherwise. Not a surrealist,but a poet who offers occasional deflections of narrative. Even a deflection isan acknowledgment of the real, as a shape drawn around an absence. A deflection,or an array of characters who might not necessarily be properly payingattention, or speaking the truth of the story, as the poem “Baby Pianos,” from TheTormented Mirror, begins:

A piano had made a huge manure. Its handler hoped thelady of the house wouldn’t notice.

But the ladyof the house said, what is that huge darkness?

The piano justhad a baby, said the handler.

But I don’t seeany keys, said the lady of the house. They come later, like baby teeth, saidthe handler.

Meanwhile thepiano had dropped another huge manure.

AsCraig Morgan Teicher writes as part of his afterword that Edson is “obsessedwith miscommunication; it is his bedrock truth. People don’t listen to eachother, are generally intent on fulfilling their own needs, and willfullyignorant of the needs of those around them. His characters constantly argue andcontradict one another.” Moving through this collection, I can now see Edson’sinfluence in a variety of younger American poets, most overtly through Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany (who I do think is doing some great things), butalso through Evan Williams, Shane Kowalski, Zachary Schomburg, Leigh Chadwick and the late Noah Eli Gordon, as well asthrough Manguso herself, across those early poetry collections. In many ways,Niespodziany might even be the closest to an inheritor I’ve seen of Edson’swriting, although with the added element of a more overt surrealism viaCanadian poet Stuart Ross. And perhaps, through Little Mr. Prose Poem, Iam slowly beginning to understand what all the fuss has been about.

April 14, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joy Castro

Joy Castro

is theaward-winning author of the 2023 historical novel

One Brilliant Flame

,set in the 19th-century Cuban anticolonial émigré community in Key West;

Flight Risk

, a finalist for a2022 International Thriller Award; the post-Katrina New Orleans literarythrillers

Hell or High Water

, which received the Nebraska BookAward, and Nearer Home, which have been published in France byGallimard’s historic Série Noire; the story collection

How Winter Began

;the memoir

The Truth Book

; and the essay collection

Island of Bones

, which received the International Latino Book Award. She is alsoeditor of the craft anthology

Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazardsand Rewards of Revealing Family

and the founding series editor ofMachete, a series in innovative literary nonfiction at The Ohio StateUniversity Press. Her work has appeared in venues including Ploughshares, TheBrooklyn Rail, Senses of Cinema, Salon, GulfCoast, Brevity, Afro-Hispanic Review, SenecaReview, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The New YorkTimes Magazine. A former Writer-in-Residence at Vanderbilt University, sheis currently the Willa Cather Professor of English and Ethnic Studies (LatinxStudies) at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where she directs theInstitute for Ethnic Studies.

Joy Castro

is theaward-winning author of the 2023 historical novel

One Brilliant Flame

,set in the 19th-century Cuban anticolonial émigré community in Key West;

Flight Risk

, a finalist for a2022 International Thriller Award; the post-Katrina New Orleans literarythrillers

Hell or High Water

, which received the Nebraska BookAward, and Nearer Home, which have been published in France byGallimard’s historic Série Noire; the story collection

How Winter Began

;the memoir

The Truth Book

; and the essay collection

Island of Bones

, which received the International Latino Book Award. She is alsoeditor of the craft anthology

Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazardsand Rewards of Revealing Family

and the founding series editor ofMachete, a series in innovative literary nonfiction at The Ohio StateUniversity Press. Her work has appeared in venues including Ploughshares, TheBrooklyn Rail, Senses of Cinema, Salon, GulfCoast, Brevity, Afro-Hispanic Review, SenecaReview, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The New YorkTimes Magazine. A former Writer-in-Residence at Vanderbilt University, sheis currently the Willa Cather Professor of English and Ethnic Studies (LatinxStudies) at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where she directs theInstitute for Ethnic Studies.1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book, TheTruth Book (2005), was a memoir that offered the true account of mychildhood as a Jehovah's Witness growing up in a violent and impoverished home.I ran away at fourteen, and the book also chronicles a little of the aftermathof that difficult decision. In addition, it explores the complexities of myCuban American heritage and the painful legacy of parental suicide.

Publishing TheTruth Book changed my life because I had previously concealed thoseelements of my past. They seemed too strange and shameful, and I was trying topass as normal in academia, a profession that was and remains normativelywhite and middle-class. To reveal those weird and troubling things about mypast, I had to overcome a great deal of fear—and decades of silence—which tooka great deal of courage, so that book was different for me than all those thathave followed it.

This newestbook, One Brilliant Flame, draws heavily upon my Cuban Americanfamily's background in Key West in the nineteenth century, a sociopoliticalmoment that is little-known today, and being able to recover that history andrestore it to public view has been very exciting and deeply moving to me.

2 - How did you cometo fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Well, I startedwriting made-up stories when I was extremely young, and my early publishedworks were short stories. That just felt natural to me, as I was absorbed fromearly childhood in the world of storybooks and Bible stories and fairy tales.

It didn't occur to meto write a memoir until I was urged to do so in my 30s by an editor and afellow writer. I actually felt quite shy and reluctant to do so.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It depends somewhat onthe project, but on the whole, I lay a lot of mental groundwork before I beginto draft, and sometimes much of the work has happened in my mind before I putpen to paper. I write everything longhand, which is immensely helpful inslowing my process down and forcing me to choose among various mental versionsof each sentence as I write them.

I do love to revise,though, so I revise many times for various elements, and I always read everysection many times aloud for rhythm, emphasis, and musicality.

4 - Where does a workof prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

Well, my short storiesare quite happy to stay short. That's my favorite form. I generally know whenI'm embarking on a book; I can feel the weight and scope of it stretching outahead of me, even if I don't know exactly what will happen.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy it. I'veheard a few awful, flat, droning readings, so I strive to make sure I providesomething intense and worthwhile. It's always top-of-mind that people couldjust as easily be at home enjoying their favorite series or reading a wonderfulbook. Instead, they've invested the time and effort to come out, so I try tofurnish an experience that will make them feel it was worth it.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Yes, very much so. ButI don't like to talk about them.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To write. To risk. Towake up.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I've been very luckyand have loved working with all my editors. I've balked at a few things,certainly, but it's always a good and edifying experience, and it almost alwaysstrengthens the work, which is what we're both serving.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

"Nothing can stopyou."

10 - How easy has itbeen for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel to essays tomemoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

Effortless. I don'tsee a particular appeal, exactly; it's just what happens.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typicalday (for you) begin?

I don't. A typical daybegins with coffee by the fire, or coffee by an open window in warm weather,and sometimes I write in a notebook, but sometimes I don't.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

It honestly doesn't.Sometimes my heart and soul feel depleted because I'm working too hard at mydayjob or due to political horrors in the larger world, so I feel drained andsad and despairing, but that's not specific to writing. When that happens, Ijust try to rest and be gentle with myself and remember to do a few extrathings I enjoy.

I do like JuliaCameron's notion of the artist's date very much.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

The salty sea.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Trees and plants;music, yes; history, obviously; and visual art a great deal. I tend to gothrough phases of obsession with various artists: Artemisia Gentileschi,Remedios Varo, Käthe Kollwitz. Film, too, especially film noir: I love itssleek aesthetic, and hardboiled narration and dialogue crack me up.

15 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

Katherine Mansfield,Jean Rhys, Colette, Margery Latimer, Sandra Cisneros, Mariama Bâ, Clarice Lispector, Louise Erdrich. Also James Joyce and William Faulkner.

16 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit Churchill,Manitoba to see the Northern Lights, polar bears, and Beluga whales. Not duringthe same season, apparently, though.

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would like to havemarried a forest ranger and been his little housewife up in a tower above thetrees. (So I could write, mainly.) I'm not a good cook or cleaner, so heprobably would have been disappointed.

I do like teaching, soI'm glad I stumbled into that. It's an excellent dayjob. I made a very poorwaitress—absent-minded, not really interested in the whole process.

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I always wrote. Idon't know the name of the thing inside that made me do so. I always just lovedwriting; it always felt natural and simple and necessary.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Great is a tricky word. I genuinely loved the newtranslation of Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, and Ivery much enjoyed the surprise of the gentleness of the stories in BananaYoshimoto's Dead-End Memories. In film, I'm still so moved andimpressed by No Intenso Agora (In the Intense Now).

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

My next book of shortstories and a suspense novel set outside Berlin.