Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 23

March 9, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Peter Dubé

Peter Dubé is the author, co-author or editor of a dozen books of fiction,non-fiction and poetry. His novella, Subtle Bodies, an imagined life ofFrench surrealist René Crevel was a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award, andhis recent work, a novel in prose poems entitled The Headless Man, wasshortlisted for both the A. M. Klein Prize and the ReLit award. He was a memberof the editorial committee of the contemporary art magazine Espace, artactuel for 18 years and is currently co-editor of The Philosophical Egg,an organ of living surrealism. He lives and works in his hometown of Montreal.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

As is the case for so many questions, there are atleast two answers to this. One concerns the writing of the book, which involvedteaching myself how to write a “book” rather than a poem, a story, or an essay.Thus in some ways it changed my approach to writing, and assisted inshaping my process, which had a profound impact. A second answer regardspublication. The appearance of Hovering World (my first book)did not have a significant impact on my life in material terms, but it didexpand my community of writers as it led to new encounters through morereadings, touring, joining the Writers’ Union, and so on. And those encountersand friendships are things for which I am profoundly grateful. In terms of itseffects on later work, a first book can, and in my case did, lay the ground, asit were, It established a number of concerns which I continue to explore –-hopefully– in greater depth and in diverse formal permutations.

2 - How did you come to fictionfirst, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

The truth is I have written across genres (poetry,fiction, and nonfiction) for most of the time I’ve written in a serious way.Genre represents possibility for me, rather than constraint. Thus I willusually gravitate toward a form I feel suits a particular project particularlywell. This also partly accounts for my interest in hybrid forms. My earliestpublications were poems and short stories. They appeared in literary magazinesand journals; then I began to publish reviews and articles in newspapers andart magazines. My first book, however, was a novel, Hovering World. What unites my work across the plurality of genres,is an enduring interest in figuration, specifically metaphor: its possibilitiesas a mode of thought and perception rather than simply a literary technique,and its larger import in the realm of the social, the way it createsassociative leaps and consequently, connection.

3 - How long does it take to startany particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or isit a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape,or does your work come out of copious notes?

An honest answer to this question is tricky since itrequires one to define what is meant by “to start.” I raise the point because Imaintain a regular notebook practice and am constantly writing down notes,observations, fleeting thoughts, things I see on the street or overhear in themetro, and very often it is one such note or other that will spark some writing.This can happen weeks, months, or more after the note was initially taken. Oncethe spark is struck however and I begin writing. a form often emerges andsolidifies relatively quickly. That form may shift a bit over the course ofcomposition, but will generally still be at least somewhat recognizable at theend. What does shift a great deal is the details. (And I am a committedpolisher of my work, so the veneer or surface definitely changes.)

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The answer to this one is already present in my answerto question number 3 above. But perhaps I can offer a concrete example here asan elaboration. My book TheHeadless Man, for example,grew out of my interest in George Bataille’s image of the “acephale”. Myinterest in him led to a long period of reading, after which I’d thought I’dworked through the obsession. Of course, he resurfaced one day and insisted onbeing heard. I was looking through some old notebooks and found a few pagesrecording some of my findings regarding that acephalic figure. I wrote a poemresponding to the image, a single poem, in which I sought to tease out acontemporary significance for this figure. However, in no time at all it provedto need more room to grow. And, it became a book, a book as hybrid as the image’shistory. (The image first surfaces, as far I’ve been able to determine, in theGreek magical papyri, but subsequently mutates over time becoming anantifascist allegory in the Twentieth Century and then - in my hands — a novelin prose poems that I hope honours the complexity of his millennia longtrajectory.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

The short answer to this one is: absolutely yes!Readings are important in all sorts of ways. First I see literature/writing aspartly (an important part) about sound, rhythm, voice (in a variety of senses),and - once again — connection. Reading directly to an audience centres thosethings. On top of that, it is a unique opportunity to see and hear from yourreaders/audience in real time and determine what is working especially well,and how. It is a conduit for feedback. And the conversationsafter a reading are often revelatory and engaging too.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

Although ideas and questions certainly emerge in apiece during the writing process itself, I have noted that a number of recurringtheoretical/philosophical concerns run through the body of my work in ways bothmore and less subterranean. One of the main ones, for example, isphenomenological in nature, and about the tricky relationship betweenexperience and account — the manner in which our lives are made meaningful –- indeedare made — by how we talk about or explain them. Another, and clearly relatedone, might be language and its operations, the ways in which itembodies/enables/elaborates thought. Beyond such abstract philosophical mattershowever, the work tends to investigate the desire for, and experience of,community and its tricky relationship to individuality too.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer beingin larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of thewriter should be?

Needless to say, the present historical moment is adifficult one for writers. Social, political and technological change hascomplicated life for everyone, writers included. That said, I’m notprescriptivist by nature, so I hesitate to make blanket statements about therole of the writer as such. I am more inclined to feel that each writer willcreate her/his/their own role and such a role is likely to emerge naturallyfrom the kind of work they produce.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

This is an interesting, if difficult, question; I willsimply say, my experience has varied. The occasions on which I have foundworking with an editor incredibly helpful and rewarding have consistently beenwhen the editor was sufficiently widely-read to recognize a variety ofaesthetic traditions and consequently able to look at, and work with, aparticular text on its own terms, with an understanding of its specific stakes,interests and project, and without attemptingto impose some other, arbitrary, form on it. The less successful cases for mewere those in which the editor had a fixed preconception of what made for “good”or “literary” writing. This invariably, in the end, produces a mutilated andinauthentic text.

Happily, I have worked with more editors of the formertype.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

If we are talking about writing advice specifically,then it would be the caution I received years ago to not worry about “writing a‘perfect’ first draft. That a first draft is “a starting point, and not afinishing line.” Happily I did take that to heart; my first complete drafts arenow always a place to begin polishing. If we mean advice for getting throughlife’s tougher moments, I’d have to hearken back to the wise words of PatsyStone (in Absolutely Fabulous) when she said “Darling, finishthe beaujolais and walk away from it.” That’s a handy recommendation forsomeone like me, who might have a tendency to take the small stuff a little tooseriously at times.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres (novels to short stories to essays to poems)? What do you see as theappeal?

In fact, this comes quite naturally to me; I’ve beenwriting poetry and fiction in tandem since I was a teenager. I suppose thisstems from my deep interest in all of the possibilities of language, all thecool stuff one might be able to do with it, and the desire to investigate thosepossibilities. Nonfiction and critical writing came to me a little later in mytwenties, I suppose… but those too arise from the same curiosity in many ways.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep,or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I am a morning writer; I prefer to get out new writingearly, as close to when I get up as possible –- while the gates to theunconscious, as it were, are still somewhat ajar, and the business of the dayhas not yet cluttered my mind. Afternoons I tend to focus on looking over andediting stuff.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turnor return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A nice walk is usually helpful to me. I get up and gooutside to get my blood pumping in time to the rhythms of the city. Theexercise and the sights, sounds and energy help recharge the battery and almostinvariably provide me with some image or snippet of talk that will get me backto work. For really serious blockages I have also been known to use some of thetechniques I’ve learned from surrealism; a little bit of automatic writing willget the words flowing again and is likely to provide an image or phrase as akind of starting point for beginning anew.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Chanel No. 5, in some ways. (That was my Mum’s perfumewhen I was a little fella and it always calls up my childhood for me. Hence thedeepest sense of home.) The odour of a particular type of cookie has the sameeffect on me too, I might note.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Given that I’ve written about and reviewed art fordecades, my imagination is clearly fed by works of visual art: contemporary,modern, and some earlier periods as well. Further, since I’m a movie buff and did graduate studies in cinema, themovies are just about omnipresent in my consciousness. Finally, I shouldreprise something I said above too: the city. I am an urban creature, and thepresence, energy, beauty and brilliant noise of a large city feed myimagination in particular ways few other things can.

15 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My personal canon would clearly include thesurrealists for sure, as well as gay liberationist writers and the New Narrative group. Those streams of writing are vital sources for my work, mythinking, and my politics. They also help provide a sort-of framework for myapproach to daily life at the same time. Finally, there’s no way for me to talkabout the important influences on my literary work properly understood withoutnaming Angela Carter. My encounter with her books was absolutelytransformational.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

The list of things that interest and tempt me is verylong indeed and features travel destinations, workout objectives, and variouspossible encounters and experiences, but if I restrict myself to just mycreative output: I am presently working on a friend’s film project, and am verymuch enjoying it. This has somehow triggered my long set-aside interest inmovie-making, so who knows… thoughtime and money are a factor here needless to say.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

As a teenager, I trained as an actor for severalyears, and was fairly serious about it; I suppose, if writing hadn’tintervened, I might have pursued that path. I also, at some point in myundergraduate studies, entertained the notion of studying the law, so thatcould have been a possibility too, if it hadn’t lost its appeal so quickly. Inthe end, writing was the only choice that really worked for me.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

That decision surely begins with a natural inclinationor predisposition, and with being a reader. Being someone who loved words,stories, and poems and found real joy in them led me to understand their powerto move. That in turn made me want totry it out myself. Once I began, I discovered exercising the imagination helpedone engage with what is in excess of reality: all the vital potential andcomplex possibility underlying some situations and experiences. Writing aboutthem — putting them down on paper — made that potential feel more real somehow,and –– as importantly –– gave them anenduring trace. That closed the circle for me, and I was hooked.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

I recently read Brendan Connell's Metrophilias which struck me as walking the line between shortfiction and prose poetry wonderfully, and doing so while being imbued with anicely realized, frequently weird, and sometime disturbing, eroticism.

As for a film, well, I recently enjoyed Jan Svankmajer’sInsect which was, to put it simply, astounding. I watched itas half of a double feature that also included a rewatch of Cruising. (That, I must say — as a sidebar — was an a veryinteresting combination of viewing.)

20 - What are you currently working on?

Having just published a new chapbook of poems and a hefty work ofnonfiction/poetics I am back to fiction and midway through a new novel.

March 8, 2025

VERSeFest 2025 : March 25-29 : schedule now online!

OUR FESTIVAL SCHEDULE IS NOW FULLY ONLINE: Check out the schedule for the fifteenth annual VERSeFest: Ottawa's International Poetry Festival! readings and performances by Jessica Hiemstra, Em Dial, Susan J. Atkinson, Oana Avasilichioaei, Kimberly Quiogue Andrews, Xénia Gould, Nshannacappo (Neal Shannacappo), Luna Cardenas, Rebecca Kempe, King Kimbit, Kaz Mega, Dumi Deja, Salem Paige, Laurie Koensgen, Adrienne Stevenson, Chelene Knight, Pamela Mosher, Alexis Vollant, Andy Weaver, Terese Mason Pierre, Phil Hall, Eileen Myles, Zoe Whittall, Chloé LaDuchesse, Stephanie Roberts, Bridget Huh and Sara Berkeley! poetry workshops by Eileen Myles and Phil Hall (with limited spaces)! a free daytime reading at Carleton University by Eileen Myles!

OUR FESTIVAL SCHEDULE IS NOW FULLY ONLINE: Check out the schedule for the fifteenth annual VERSeFest: Ottawa's International Poetry Festival! readings and performances by Jessica Hiemstra, Em Dial, Susan J. Atkinson, Oana Avasilichioaei, Kimberly Quiogue Andrews, Xénia Gould, Nshannacappo (Neal Shannacappo), Luna Cardenas, Rebecca Kempe, King Kimbit, Kaz Mega, Dumi Deja, Salem Paige, Laurie Koensgen, Adrienne Stevenson, Chelene Knight, Pamela Mosher, Alexis Vollant, Andy Weaver, Terese Mason Pierre, Phil Hall, Eileen Myles, Zoe Whittall, Chloé LaDuchesse, Stephanie Roberts, Bridget Huh and Sara Berkeley! poetry workshops by Eileen Myles and Phil Hall (with limited spaces)! a free daytime reading at Carleton University by Eileen Myles!with your usual batch of participating Ottawa-area host organizations, including In Our Tongues, Plan 99, Urban Legends, Arc Poetry Magazine, flo. lit mag, Riverbed Reading Series, Carleton University and the Ottawa Public Library! tickets are now available, as are evening passes, and festival passes! and of course, donations are always welcome (we even issue tax receipts).

https://www.verseottawa.ca/

March 7, 2025

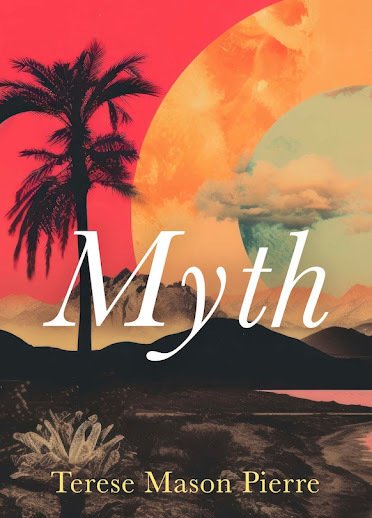

Terese Mason Pierre, Myth

Transfer

Much occurs in the glowbehind my eyes.

With every blink, memoryexpires, guides me

to a new construction. Inan ideal world,

my mouth works properly,my hands hold

my skin with love, thebody between

my sheets is my own. In theconspiracy of

imagination, birds soundnotes above

the coloured truth at hightide. My open chest

can house many storiesabout loss

and unrequiredadmiration. I feel every inch of it

like glass. No one mournsmore than me.

No one hopes for changemore than the sun,

the daughter, the carrierof light through

a lake filled with whatlooks like water.

Iknow there have been many eager to see what Toronto writer and editor Terese Mason Pierre could do through a collection beyond a chapbook, so it is good tosee the release of her full-length debut,

Myth

(Toronto ON: Anansi,2025), a collection of physical and precise poems on and around stories,storytelling and how stories take hold. These are poems as foundational as theearth or the ocean, offering sharp and astute first-person observational, declarativeand descriptive lyrics. “My grandfather says we can eat what we kill.” she begins,immediately setting the tone with the opening line of the opening poem, “Fishing,”“We wade into the water and find a shark.” Terese Mason Pierre’s poems tellsstories, including those that hint of their implications, meanings and truepurposes. She wants you to listen to what these stories are saying. As thisparticular piece continues: “In the bleeding night, we carry it home, across /the mountain. The way your feet land before // mine, I memorize. I copy yourplan for leading / me out of this spectacular cycle—fold it in and over //ourselves until our parents finally call for / the doctor. Our love has neverallowed // itself to be gutted.”

Iknow there have been many eager to see what Toronto writer and editor Terese Mason Pierre could do through a collection beyond a chapbook, so it is good tosee the release of her full-length debut,

Myth

(Toronto ON: Anansi,2025), a collection of physical and precise poems on and around stories,storytelling and how stories take hold. These are poems as foundational as theearth or the ocean, offering sharp and astute first-person observational, declarativeand descriptive lyrics. “My grandfather says we can eat what we kill.” she begins,immediately setting the tone with the opening line of the opening poem, “Fishing,”“We wade into the water and find a shark.” Terese Mason Pierre’s poems tellsstories, including those that hint of their implications, meanings and truepurposes. She wants you to listen to what these stories are saying. As thisparticular piece continues: “In the bleeding night, we carry it home, across /the mountain. The way your feet land before // mine, I memorize. I copy yourplan for leading / me out of this spectacular cycle—fold it in and over //ourselves until our parents finally call for / the doctor. Our love has neverallowed // itself to be gutted.”Setin five section-clusters of shorter lyrics—“Expanse (the sea),” “Interlude(the deep),” “Brink (the earth),” “Interlude (the cosmos)”and “Swell (the stars)”—she interplays the elements with the cosmos witha call-and-response, the “interlude” of the Greek chorus, providing asides tothe main narrative as part of this main narrative. “I’ve done it because it waswhat I wanted. / My neighbour’s garden grows mangoes beyond / a rotted fence,”she writes, to open the poem “Rich,” “and I stole one as it they’drequire / a descendant if caught. But this trope is old. / This means nothing.”

Inthe end, myths are the stories we tell ourselves and each other, the storiesthat warn, catch and inform, stories that can propel us forward, hold us back,distract our attention or inform our world-view, including times when all ofthe above occur simultaneously. “My mother tried to tell me I was broken,”begins “Dead Living Things,” “and I shut her away. Who died and made heroracle? / Where my mouth falters, my skin reserves.” Oh my, this is good. Mythis a striking and deeply complex debut.

March 6, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jordan Dunn

JordanDunn is theauthor of Notation (Thirdhand Books), Physical Geography as Modifiedby Human Action (Partly Press), as well as various chapbooks and ephemeralprints including Common Names, Reactor Woods, and A Walk atDoolittle State Preserve. He lives with his family in Madison, WI, where heedits and publishes Oxeye Press.

1 -How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Ipublished my first book, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action,with Partly Press in 2022. Partly Press is edited by Chuck Stebelton and housedat the Lynden Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, which is a wonderful non-profitthat has many missions in addition to running its literary press. This meantthat my first book appeared in a location slightly off-center from traditionalpoetry channels. It felt good to appear in a new space, and that experience helpedme feel confident that poets can appear in different kinds of venues.

My newbook, Notation, is like Physical Geography in that it’s a bookconstructed out of other books, and it relies heavily on intertexts to binditself together. The subject matter of Notation was different for me, however,in that it was partially inspired through more personal experiences, includingthe loss of several friends. Notation also feels different in that itsduration is more containable, and it looks quite different on the page comparedto Physical Geography.

2 -How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’vealways been attracted to the portability of poetry—it is an activity that canbe adjacent to whatever life I have at any given moment in time. I’m notpositive I’m a poet, but the poets gave me a seat at their table, so here I am,enjoying the good company of poets.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Idon’t know when I am beginning a project. After some time, I notice groups ofconsistencies, and then I focus on those as points of attachment. Because I aminterested in book arts, I often make small handmade editions. So, there’s lotsof variability with time and process and drafting.

4 -Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Accumulationover time is necessary for me. I don’t really attempt to compose individualpoems when I’m writing.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I usedto be more invested in performativity when I would give readings because mywriting was focused on permutation, and so the reading event felt like anextension of the writing process. These days, I am trying to focus on lifting statictext off the page. I feel like I am struggling with that process because Idon’t like it when text loses its subjectivity.

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I’m deeplyinvested in literary community and the answers I can find through friendshipwith other writers and artists. I’m also interested in natural history andunderstanding the local ecologies and landscape histories in my area, as wellas areas that I visit frequently.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

As Iunderstand it, literary writing is rapidly becoming an analog fixture in ourculture. That means it could have staying power and be used as a refuge, or itcould gradually empty itself of meaning and become irrelevant. Hopefully therole of the writer is to protect against obsolescence.

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Essential!Thank you to my past editors: Chuck Stebelton, Kylan Rice, and Lindsey Webb.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Ifinished college at the start of the Great Recession. I was living back athome, I was having a hard time finding work, and I was thinking about taking ajob that involved writing scripts for a company that produced training videosfor corporations. At the time, my dad was an ex-marine banker involved incommercial real estate lending, and when I told him about the job opportunityhe said, “What, are you going to be a fucking sell-out?” So, I instead saved upmoney working in a warehouse, quit that job, and rode my bike across thecountry. Thanks, dad. XO.

10- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

When I’mat my best and my schedule is at its best: I wake up, let the dog out, makecoffee, and then retreat to my lower-level workspace. I like to write in themorning before the rest of the house wakes up. Often, the carnival of being aparent means I write whenever I can, and I often wear noise-cancelingheadphones.

11- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

I keepstacks of books around my desk and on shelves above my desk. When I stall, Ipick up a book and read it until something wants to be transcribed, and thenI’m writing again.

12- What fragrance reminds you of home?

LakeSuperior white pine.

13- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

All ofthe above. I feel like books are simply placeholders for those other things.

14- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Toomany to list! A few writers/writings I return to: Susan Howe, Lyn Hejinian,Thomas A. Clark, & Thoreau’s journals, among many others.

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Athru-hike, like the AT or the PCT.

16- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Hmm .. . working with living things outside the world of finance?

17- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Repetition.

18- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Weedsin Winter, byLauren Brown. A few weeks ago, I watched The Lost Daughter.

19- What are you currently working on?

I’mworking on a new manuscript that feels attached to the methods used to writeNotation. I’m trying to distill two years of daily/occasional writing withinfused transcription and travel journals. I’m also working on several littlebook arts projects that include a disappearing prairie, collages from Thoreau’sjournals, images of tidal sand, and images of hackberry bark.

March 5, 2025

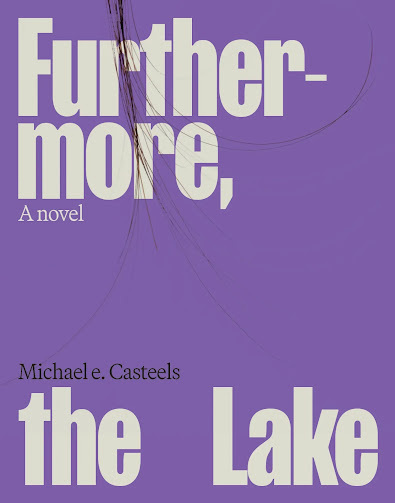

Michael e. Casteels, Furthermore, the Lake

The further I walked, thecloser I got. To what, I wasn’t sure, but my feet kept moving, carrying therest of me along with them. They had their own preconceived destination—somewherethey might finally settle down, a little slice of heaven, a place to call home.I was just their solitary witness, a quiet companion, the documenter of theirlong journey.

It was easy. They walked;I followed.

The path snaked along thelakeside. The sky was a dark canvas the stars punched small holes into one byone. A sickle moon crept up from behind the horizon. A large bird beat itsenormous wings, faded into distance. Somewhere a duck quacked, then hushed, andthe relative silence resumed.

A few soft waves lappedagainst the shore with a steady rhythm. The small stones cascading across oneanother clattered out a soft melody. It was a lullaby, though I wasn’t sure whowas being lulled: me, the city, or the lake itself.

The lake sighed. I sighed.

The city drifted off intothe night, far above the lake and me.

Thelatest from Kingston poet, editor and publisher Michael e. Casteels is thedebut novel,

Furthermore, the Lake

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2025),published as part of editor Stuart Ross’ 1366Books. Following a handful of chapbooksof poetry, prose and visuals, as well as his full-length collection,

TheLast White House at the End of the Row of White Houses

(Picton ON:Invisible Publishing, 2016) [see my review of such here], Casteels’ Furthermore,the Lake is composed as a novel of accumulated scenes that shimmer andripple, contradict and evolve, across shifting narratives. “A night can dragits feet when it wants to,” he writes, early on, “and that night it wanted to. Theoccasional car. An infrequent passerby. But when the late hours finally shiftedinto the early hours, even these ceased. The street lights shone down onnothing but cracks in the pavement.” Casteels’ narrator might be reliable but thescenes they participate in and witness seem to contradict, offering anuncertain view. His prose is composed across short bursts and flash sections comparableto the flash fictions of writers such as Lydia Davis [see my review of one of her most recent here] or Kathy Fish [see my review of her latest here], but onethat works a larger shape, although one not necessarily formed across any kindof easy or obvious concrete narrative. One has to pay close attention to detail,even across such lovely passages. And yet, the narrative does progress, momentsthat build upon moments, a thread within the swirl and field of further seemingly-contradictoryelements.

Thelatest from Kingston poet, editor and publisher Michael e. Casteels is thedebut novel,

Furthermore, the Lake

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2025),published as part of editor Stuart Ross’ 1366Books. Following a handful of chapbooksof poetry, prose and visuals, as well as his full-length collection,

TheLast White House at the End of the Row of White Houses

(Picton ON:Invisible Publishing, 2016) [see my review of such here], Casteels’ Furthermore,the Lake is composed as a novel of accumulated scenes that shimmer andripple, contradict and evolve, across shifting narratives. “A night can dragits feet when it wants to,” he writes, early on, “and that night it wanted to. Theoccasional car. An infrequent passerby. But when the late hours finally shiftedinto the early hours, even these ceased. The street lights shone down onnothing but cracks in the pavement.” Casteels’ narrator might be reliable but thescenes they participate in and witness seem to contradict, offering anuncertain view. His prose is composed across short bursts and flash sections comparableto the flash fictions of writers such as Lydia Davis [see my review of one of her most recent here] or Kathy Fish [see my review of her latest here], but onethat works a larger shape, although one not necessarily formed across any kindof easy or obvious concrete narrative. One has to pay close attention to detail,even across such lovely passages. And yet, the narrative does progress, momentsthat build upon moments, a thread within the swirl and field of further seemingly-contradictoryelements.Last but not least, youboarded the train and sat down in a window seat. You looked out at the stationplatform and smiled. Even from this distance your eyes were tiny lakes thatmirrored whatever they saw, and what they saw was me, standing on a shoreline,waving goodbye while you drifted away in your red canoe. Waves drawing you furtherand further. I didn’t expect to take a second look, but I did: your train longgone for years.

Casteels’prose has an ease to it, a compelling tone that floats across pages, amid numerousmemorable lines and prose-blocks. “The bathtub is surprisingly agile for itsage. You’d think it would lumber like a hippopotamus,” he writes, “but it’smore like a rhinoceros charging blindgly into the night. I’m a few hundredmetres behind it and losing ground. The bathtub leaps over a white picketfence, rounds a corner, and then it’s gone.” There is something of his shiftingnarrative reminiscent of Canadian playwright and mathematician John Mighton’splay Possible Worlds (1990; a film adaptation was released in 2000),holding a shifting not of perception but of action, of what is actually beingperceived. The unsettling of this foundation is purposeful and beautifully done,and does progress towards an understood meaning, one that rocks a foundation ofloss, grief and ultimate through-line, although one that doesn’t unfold orreveal as much as finally allow, all centred around, somehow, this particularimage of the lake. “The lake remembers a seagull,” he writes, “but it’s nowhereto be seen. It remembers loons, but they’re gone too. No, wait. I just heardone. A heart-wrenched wail. No response.” As he continues:

This could have beenyears ago. Or sometime last week. Or three days from now. It’s the type ofthing that happens again and again, and once started, can’t be stopped. A strandof hair stuck to your cheek. I brushed it away. It’s the only thing that keeps mefrom wandering off course. It’s what passes through my mind every time I squirta little toothpaste on my toothbrush.

March 4, 2025

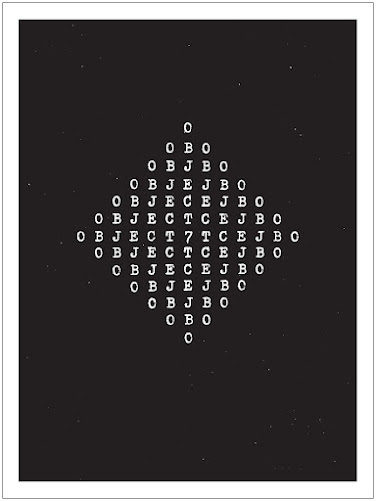

Tilghman A. Goldsborough, Object 7 ( ,a spirit loosely, ,bundled in a frame, )

2B honest [4 once] i’mstill kinda fucked up

from when The Groundmoved ..

, it’s hard 2 dealdirectly && forcefully w/ pressing issues

when there’s so muchgoing on w/o+w/in

&& i don’t kno

where 2 begin .

like , idk if i ever toldu

that My Greatest Fear isfalling

from a great height..

i don’t think it’s (re:)hitting

The Ground tho; it’smaybe more

fear of the Panic! ,, ofthe absolute lack

of control as a foregoneconclusion rushes

up 2 meet U,,

I’mabsolutely floored by the cluster, clash and careening of Brooklyn poet Tilghman Alexander Goldsborough’s second full-length collection, following

The Western

(1080 Press, 2023), his

Object 7 ( ,a spirit loosely, ,bundled in a frame, )

(Brooklyn NY: Futurepoem, 2024). Across what might first seem a jumble of punctuation,shortened words and clipped text, Goldsborough offers myriad delights through aninventive and engaged lyric working at a whole other level of visual and soundeffect, one that at turns sits as propulsive and precise, but ever highlypurposeful, thoughtful and deliberate. Reading through this collection, I’mcurious as to how such poems might sound aloud: performative and gestural, I’dsuspect. “The Yung Man is a Modern Person using modern technology {whose / mostvaluable possession is a wrinkled piece of parchment paper inscribed / withlatin text}_trying to Stay-Ahead of this Nothing he sees thru solace in /activities in The Present: getting in academic fights during master classes /at the nearby university_watching hours & hours of Home & Garden /Television, during which he described a 45 second Lowe’s Baumarkt / commercialas ‘…a capitalist assault that just won’t end…’_texting while / driving a 1996Mercedes E-class sedan along winding county roads w/ the / windows open,blasting CDs he bought back in high school.”

I’mabsolutely floored by the cluster, clash and careening of Brooklyn poet Tilghman Alexander Goldsborough’s second full-length collection, following

The Western

(1080 Press, 2023), his

Object 7 ( ,a spirit loosely, ,bundled in a frame, )

(Brooklyn NY: Futurepoem, 2024). Across what might first seem a jumble of punctuation,shortened words and clipped text, Goldsborough offers myriad delights through aninventive and engaged lyric working at a whole other level of visual and soundeffect, one that at turns sits as propulsive and precise, but ever highlypurposeful, thoughtful and deliberate. Reading through this collection, I’mcurious as to how such poems might sound aloud: performative and gestural, I’dsuspect. “The Yung Man is a Modern Person using modern technology {whose / mostvaluable possession is a wrinkled piece of parchment paper inscribed / withlatin text}_trying to Stay-Ahead of this Nothing he sees thru solace in /activities in The Present: getting in academic fights during master classes /at the nearby university_watching hours & hours of Home & Garden /Television, during which he described a 45 second Lowe’s Baumarkt / commercialas ‘…a capitalist assault that just won’t end…’_texting while / driving a 1996Mercedes E-class sedan along winding county roads w/ the / windows open,blasting CDs he bought back in high school.” Goldsboroughwrites the body, the black body, the black body in America, orbiting a seriesof concentric circles that land each and purposefully upon that radiating self,held without easy recourse in a particular social and political space. “It’s11.11 & idk what i want.” he writes, to open the propulsive two-part “testimonialof a depressed & disillusioned student / who seeks salvation—or an easyanswer—in the / ‘historically black’ nature of an UBCU & doesn’t find /what he thought would be There.,” “& times i speak in this classroom ofstrangers / abt ‘pure, destructive consumerism,’ ‘white supremacist capitalist/ patriarchy’ n other salient / issues. / otherwise i suffer in silence &the comfort of a persistent lowkey buzz / staring blankly & the consteallationson the tiles in the ceiling / or @ the blinds imported from Venice / or @ the unwritten possibilities on the blankboard / or @ the wood pulp taking the form of a table posing as a desk. / i amfeeling detached from ‘my community’: this room fully of hyphenated / american youth:[.]” He writes to find and articulate his cultural and political space, his ownagency, across a sequence of frays and histories and conflicts. Or, as the poem“domestic iii” begins: “,society frays @ the seam /where / the legs are sewntogether . / it was not built 2 last .”

Setin seven poem-sections—“JACQUELINE TOMATENCREMESUPPE ASCHENBECHER,” “C ON ST ELL A TI O N,” “V BROKE IN BERLIN VOL. I,” “TRAUMZEIT,” “EIGHTEEN,,,NINETEEN,” “CDMXTALES” and “NINETEEN,,,TWENNY (2)”—the poems assembled offer a combination ofclipped and gestural language, shortened words and syntax and punctuationspread out into constellations. Goldsborough’s Object 7 ( ,a spirit loosely,,bundled in a frame, ) is the true promise of lyric possibility made flesh.

March 3, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kevin Holden

Kevin Holden is a poet, critic, and translator. Heis the author of seven books and chapbooks of poetry, including Solar, whichwon the Fence Modern Poets Prize, Birch, which won the Ahsahta PressAward, and Pink Noise, recently out from Nightboat Books. Histranslation of Jean Daive’s The Figure Outward is forthcoming thisspring from Black Square Editions. His work has appeared in severalanthologies, including Best American Experimental Writing (Omnidawn) andIf Bees Are Few (Minnesota). He has taught at Bard, Harvard, and Iowaand is currently a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. He is alsoan activist and cares a great deal about trees.

1 - How did yourfirst book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

Back in 2009,Cannibal Books published a chapbook of mine called Identity.I'd published two little ones before that, but this was a different experience.The publisher of Cannibal, Matthew Henriksen, deeply, passionately believed inthe poetry. There’d been validation of my work before, but this came fromanother space, an editorial one, and outside of the contexts of people I knewor of an academic program. Matt was extraordinary, and I got to know him moreat the Frank Stanford Festival he organized in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Heconvinced me that I was doing something significant. That my work was unusual.There's a lot to say about him, that time, the press’s energy and community. Forme, in short, he made me feel that my work merited being published in bookform, that that was something that needed to happen. When my first full-lengthbook, Solar, won the Fence Prize, that was something on a larger scaleof course, and the attention the book received was very meaningful to me. Butthat earlier work with Matt, on something that was “only” a chapbook, wasreally important and encouraging. As to how the more recent work compares, I’dsay it’s… stranger? It’s certainly gotten more complex. Matt was actually oneof the people who convinced me that the stranger and “harder” work was theright trajectory, that it was rarer, surprising, unique. I think Pink Noiseis definitely a further step along that path. In certain aspects it mightactually be more “accessible” than Solar, but it is likely also deeper,more dimensional, and more complex.

2 - How did you cometo poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

For me it wasalways poetry. I like novels, but poetry, once I began reading it, spoke to meand seemed right; it made sense to me in a much deeper and more immediateand natural way. I came across The Waste Land more or less byaccident when I was eleven years old. It felt true, like a world,and like magic. It harmonized with how I felt and perceived, I suppose.(Syntactically, emotionally, musically, imagistically.) It was that way onward.I also started writing poetry around that time. I've never tried writingfiction. I do write essays, and philosophy is very important to me. But thenovels I care most about are often considered to be “closest” to poetry: Woolf,Faulkner, Genet, Toomer… Poetic grammar just feels... accurate. And wherebeauty resides. I can't imagine it otherwise.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

I’d say itcomes and goes. When it’s there, it often comes fairly quickly, but then theprocess of putting it all together is slow. And there are lots of notes andscribbles, but when something feels like it’s happening as a “poem,” it’susually quick (and often close to what will be its final shape). The process ofarranging the pieces is more arduous, especially as some of the poems and sectionsare quite long.

4- Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

They begin inperceptions, feelings, or in the words themselves. I think I’m mainly an authorof pieces that combine into larger projects, but fairly early on, once thereare more pieces and different kinds, I’m trying to think of how they will cometogether and harmonize into a book.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

After allthis time, I still get nervous before readings. But I do enjoy doing them, andI think hearing the work is important. The poems’ sound is very central for me,and they are usually pretty musically dense. I certainly write hearingthem in my ear, and the poetry’s internal architectures become clearer when readaloud (especially as they often involve distortions of grammar). I often readat a somewhat fast pace, and that’s intentional; there’s an intensity and akind of heaping up of rhythm that is important for me.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I’minterested in the way in which poetry is or makes reality. I suppose, in asense, these are Modernist (or adjacent) concerns. There are things said by Vicente Huidobro and Tristan Tzara that feel very right to me. I also feel close tosomething Paul Celan said: “I try to reproduce cuttings from the spectralanalysis of things.” And to various aspects of the polyhedron that isObjectivist poetics. I don’t know if there are theoretical concerns “behind”the writing — the writing is, I’d say, just itself, emergent and organic — andI’m certainly not trying to write so as to “demonstrate” or enact some theory. Butthere are theoretical questions and apparatuses out in the world that interestme, for sure. Adorno’s aesthetic theory feels right. Wittgenstein. I’minterested in the poem and the book as their own monadic worlds, being orextending into reality. And I believe that poetic objects are like bundled upcross-sections of perception, feeling, and actuality cohering in language andsound. And they are formed. And in all this there is a kind of politics,to which, it seems, your next question speaks. So, the questions the work istrying to answer, as it were, regard the nature of this word I keep using,“reality.” And memory and desire, for example, are just as much a part of thatas grammar and physics. Lastly, queerness, in all its own kaleidoscopicentanglement, is central for me.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ideally, itis a role of truth, beauty, complexity, rigor. Perhaps to be guardians oflanguage. For a long time, I’ve felt that there is a politics of estrangementin aesthetic work, a resistance to the flattening of thought and experience thatis inflicted by commodification and capital, one that is made possible throughthe complexity and strangeness, through the distortions and reformations ofgrammar and thought, that are in poetry. This is, along various axes, a Marxistsentiment. And it also suggests something as simple as the awakening andexpansion of consciousness. I believe this. But lately, as we seem to beentering an era that is sometimes called “after truth,” I also believe thatpoetic language — in its particularities and nonconformities, but also in itsperceptions, accuracies, and recordings — is necessary for holding on to howthings really are, as weird and complex as that realness is. Among otherthings, this is to say that poetry is also a form of vigilance and witness. Ina very pragmatic, honest sense, the “there there” is slipping away in socialmedia algorithms, AI, and political misinformation. Poetic language can andshould work to resist that. Though poetry’s relation to truth is an ancienttopic that could be exfoliated forever, one thing that is accurate, howevercomplicatedly, is that it can be “extra true,” so to speak. Practically, there’sa small audience, surely, especially in the US. But that doesn’t meanthe “role of the writer” is any less real.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

I often findit helpful. It can be clarifying when it’s difficult to see the forest for thetrees.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

For poetry,“make it new”? For life, the Heart Sutra.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to translationsto essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

They’re doingquite different things, and they each involve or require, for me anyway, prettydifferent “mental states.” If I’m really in the rhythm or mood of poetry, itwould be difficult to pivot suddenly and try to write essayistic prose. So,they would come in different phases, at different times. That said, they arealso just different forms or focal points to which to turn attention, sosometimes the rotation is not as hard. All of the forms are difficult, but I’dsay that translating poetry especially can be very intense cognitive labor. Ina sense, it’s also nice, because you’re working off of something that isalready “there,” a surface, not trying to bring something into being all onyour own, as it were. Anyhow, each mode and activity can say and show differentthings and do so differently. And that multiplicity feels valuable.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

It’s a littlesporadic. When I was at Iowa, I had the open time to write every day. That wasalso part of the culture. Sit at the kitchen table, go to a café, write things.That’s the luxury and also (kind of) the responsibility. I don’t really havethe space to do that now. Hopefully there’s time and “head space” for notes,scraps of things. And then windows open where more fluid or focused work ispossible.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Nature (orthe thought of it), woods, rivers, snow. And to other art, pretty much allgenres. For a bare language engine, Modernist fiction. For something like aworld aspect ratio, “art” film like Bergman or Tarkovsky.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

That’s abeautiful question. I’ll conflate it a bit with “childhood.” I grew up in morethan one place. Succinctly: for my father, woodsmoke; for my mother,honeysuckle.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Oh,absolutely. I’d say all of those. The natural world is extremely important tome, trees and forests especially. There’s a lot of math and science in my work,especially topology and geometry. Ballet, lots of music, maybe especially electronicand minimalist, and lots of painting, particularly abstraction of the 20thCentury.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

For poetry:Paul Celan, Leslie Scalapino, Louis Zukofsky, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Emily Dickinson are some. For philosophy: Adorno, Thoreau, and Wittgenstein. And thenovelists I mention above, especially Woolf.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

In life, goto the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. In art, somehow make a film?

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Perhaps visualart curator. (Maybe of sculpture, specifically.) I’ve written on art historyand theory at points in my life, and a long time ago I almost worked at The Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. In completely different directions, maybe amath teacher or psychotherapist.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Perhaps it’sa cliché, but I honestly can’t imagine not doing it. It’s a fundamental part ofme and my perception of reality. It’s how I hold on to the world.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I will do2x2. László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below and J. H. Prynne’s Poems2016-2024; Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria and Hirokazu Kore-eda’sMonster.

20- What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a book called Firn.It’s a book of long poems/sections, and the title is a kind of snow. I alsofinished a translation of a book of Jean Daive’s that I’ve titled The FigureOutward; it’s coming out from Black Square Editions this spring.

March 2, 2025

Deborah Meadows, Bumblebees

We broke the silence.

We misread anguish asthreat, flail for oxygen as attempted assault, taken down, wounded.

Warhead accidentallyslipped to the Mediterranean Sea, then upon rescue effort, we fumbled it lower,unreachable trophy, case deterioration.

We installed temporaryart in the park from thrown out materials to disrupt continuity of hatred inthe community, to heal.

We had a crazy hunch howthings so heavy got here, disturbed bones, patterned thought, quarried firstcauses, harp recordings.

Power lines in thecity-edge plant we hacked just coming online, restoration play, just kind of electricalcharges, juice suspended.

We picketed, not toviolate the code, Nuremberg, not to bomb the open market in Guernica, Spain,not to have allies violate the principles in Palestine.

Please Respond, BreakSilence. (“Bumblebees”)

Thelatest from California poet Deborah Meadows, the author of more than a dozentitles—including

Translation – the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems

(Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] and

Neo-bedrooms

(Shearsman Books, 2021) [see my review of such here]—is

Bumblebees

(NewYork NY: Roof Books, 2024), an assemblage of declarative, expansive andsequenced prose poems. Bees, of course, are the literal ‘canaries in the coalmine’ when it comes to climate change, and poets have been engaged with bees withthis in mind for moons, with recent examples being Toronto poet Andy Weaver’s WereThe Bees (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2005) [see my review of such here],the late American poet ‘Annah Sobelman’s In the Bee Latitudes (BerkeleyCA: University of California Press, 2012) [see my review of such here] or theclimate-overt

Listening to the Bees

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions,2018), a collaborative work by scientist Mark Winston and Vancouver poet RenéeSarojini Saklikar. Constructed as a book-length suite, Meadows’ Bumblebeesis a collection on elements of natural infrastructure, “the daunting complexityof earthly existence in the climate-changing present’” (as Carla Harrymanwrites as part of her back cover blurb), from bees to mushrooms, all of which areunder global threat due to climate change. “We made terrible mistakes,” shewrites, as part of the title sequence, “got off the train at the wrong stop, /miscalculated how much our earth could take. // Maintenance of vision ismarking our minds as we convene a / forest of signs and get on.” Her poemsstretch, extend and endlessly thread, providing mitochondrial connectionsbetween pages, between poems, that hold the collection together as animpressive single unit of composition.

Thelatest from California poet Deborah Meadows, the author of more than a dozentitles—including

Translation – the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems

(Bristol UK: Shearsman Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] and

Neo-bedrooms

(Shearsman Books, 2021) [see my review of such here]—is

Bumblebees

(NewYork NY: Roof Books, 2024), an assemblage of declarative, expansive andsequenced prose poems. Bees, of course, are the literal ‘canaries in the coalmine’ when it comes to climate change, and poets have been engaged with bees withthis in mind for moons, with recent examples being Toronto poet Andy Weaver’s WereThe Bees (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2005) [see my review of such here],the late American poet ‘Annah Sobelman’s In the Bee Latitudes (BerkeleyCA: University of California Press, 2012) [see my review of such here] or theclimate-overt

Listening to the Bees

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions,2018), a collaborative work by scientist Mark Winston and Vancouver poet RenéeSarojini Saklikar. Constructed as a book-length suite, Meadows’ Bumblebeesis a collection on elements of natural infrastructure, “the daunting complexityof earthly existence in the climate-changing present’” (as Carla Harrymanwrites as part of her back cover blurb), from bees to mushrooms, all of which areunder global threat due to climate change. “We made terrible mistakes,” shewrites, as part of the title sequence, “got off the train at the wrong stop, /miscalculated how much our earth could take. // Maintenance of vision ismarking our minds as we convene a / forest of signs and get on.” Her poemsstretch, extend and endlessly thread, providing mitochondrial connectionsbetween pages, between poems, that hold the collection together as animpressive single unit of composition.Thepacing, the patter, especially across the title sequence, is quietlyperformative in a way one can hear the sentences lift from each page, writing chemicalimpact, climate emergency, stolen lives, declarations and elegance, a language ofhoping against hope even through all the worst of what is already happening. Ahighlight among highlights, it holds as the foundation for the collection as awhole, a narrative that furthers and furthers along, a conversation that allowsfor endless variation and possibility. “We didn’t need squirrels to learn howto chatter; we followed / our conscience.” she writes, “Thigh-deep we face thesea’s extent: good primates like us / groom, spell, frame retreat as TheSentinels of No Outer Point.”

March 1, 2025

new from above/ground press: Skrabalak, Braun, Fagan, Aube, Kemp, Gontarek, O'Reilly, Strang, Weaver, Burdick, the suitcase poem + Touch the Donkey #44,

: THE ORCHIDS, Ryan Skrabalak $5 ; free jazz ; Jacob Braun $5 ; then / here / now / there, Cary Fagan $5 ; pulp necrosis, Gwen Aube $5 ; Lives of Dead Poets, Penn Kemp $5 ; H IS THE LETTER OF THE DOOR, Maxwell Gontarek $5 ; TERMINALS, Nathanael O'Reilly $5 ; the suitcase poem, ed. Amanda Earl : Marie-Andrée Auclair * Gregory Betts * Jeff Blackman * Amanda Earl * Ellen Chang-Richardson * AJ Dolman * Doris Fiszer * Gwendolyn Guth * Jenna Jarvis * Chris Johnson * Tanis MacDonald * Roz Toner * MW $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #44 : with new poems by Austin Miles, J-T Kelly, Naomi Cohn, Alice Burdick, Melissa Eleftherion, Jennifer Firestone and Catriona Strang $8 ; from What If I Sang “Flower of Scotland”?, Catriona Strang $5 ; Robert Duncan at Disney World, Andy Weaver $5 ; I Am So Calm, Alice Burdick $5 ;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

published in Ottawa by above/ground pressJanuary-February 2025

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $2 for postage; in US, add $3; outside North America, add $7) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). See the prior list of recent titles here , scroll down here to see a further list of various backlist titles , or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; oh, and you know that 2025 subscriptions (our thirty-second year!) are still available, yes? AND THE ABOVE/GROUND PRESS POSTAL INCREASE SALE CONTINUES UNTIL JULY 9, 2025!

With forthcoming chapbooks by: J-T Kelly, Yaxkin Melchy (trans. by Ryan Greene), Thor Polukoshko, Mrityunjay Mohan, Laynie Browne, Sandra Doller, Gregory Crosby, Monty Reid, Nada Gordon, Lydia Unsworth, Andrew Brenza, Brook Houglum, Orchid Tierney, Lori Anderson Moseman, Noah Berlatsky, Terri Witek and David Phillips; and probably others! (yes: others,

February 28, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Aaron Boothby

AaronBoothbyis a settler poet of European ancestry from Riverside, California in thetraditional lands of the Cahuilla, Tongva, Payomkawichum,and Yuhaaviatamand people. The author of Continent (McClelland & Stewart, 2023), as well as two chapbooks, he lives inprimarily in Montréal, also called Tiohtià:keby its caretakers, the Kanien:keha’ka people.

1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst chapbook felt pretty natural to put together and I was lucky to haveKlara du Plessis and Jim Johnstone as editors. They’re both very astute andrespectful of what you’re trying to do as a poet in a way that was quiteaffirming at the time. I’m embarrassed by the rather awkward title, which I’vebeen known to mix up myself, but it did set the tone for my work in many waysbeing longer form, fluid, and disinterested in contained poems. I like thingsspilling over and around. It’s an excessive work, and if there’s a bigdifference now it’s that I’ve learned to work against my own tendency tooverwrite. I also presence myself more in the work, whereas before I activelyobscured and took distance from the speaker. There was feedback from Dionne Brand then later Canisia Lubrin, the editor of my first full-length, thathelped immensely in doing so.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’venever been a competent or fluid storyteller, like do not ask me to tell a funnystory! My humour is observational, spontaneous, and in many ways so is mypoetry (which, sadly, is not funny). I’ve never been interested in motivationsor characters or people in the way that tends to make fiction interesting.Anyway, I wasn’t drawn to it. Non-fiction would have been too easy, whichsounds absurdly presumptuous and I’m sure someone will think, “Oh sure, write agood essay then!” but what I mean is it comes too easily, and I benefit frommore resistance. Line by line, poetry makes you dig deeper, listen harder. Ialways feel like I can hide in paragraphs of prose, say any old shit andconvince myself and maybe others there’s something valuable in there. Maybethere is! When I do write essays I certainly try. But I like that in poetry youcan’t do that, not really. It’s like standing in a desert landscape, feelingwind wear down the phrases around you until necessary forms remain.. I adorethe desert, obviously.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Ispend most of my time not writing, though I spent many years writing all thetime. If I’m writing all the time I’ll feel like what I’m writing is differentbut it’s actually all the same. I need time and silence and reading to letwhatever I write next become different. I have at least three full projects I’dlike to actually finish and one I work on only when I can go outside and bewith grasses. When I actually sit down to write everything moves quickly. Itake notes and then ignore them. I used to write from fragments and stoppeddoing that. I have contradictions and un-interrogated habits. As for drafts, Irewrite a lot, sometimes drastically, and each is a different shape along theway. I’d say most of the time the core of the poem is already there and it’s amatter of getting rid of everything I’ve put in the way of it speaking.

4- Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Aphrase, a line, a sensation, maybe a kind of pleasurable irritation that doesn’tgo away. I’m not always working on a book from the beginning, but poems seem toaggregate themselves pretty quickly into architectures with their own tones andshape.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They’vecertainly been a large part of my development as a writer, since without aregular reading series like Resonance, that Klara du Plessis ran for years, I’mnot sure I’d be writing now and am completely sure I wouldn’t be writing theway I do or have made the relationships that sustain something as comparatively(to anything that makes money and even much art) marginal as poetry. I likereadings, I’ve been going to more regular series and open mics lately, just tolisten or chat with people who are often doing poetry more as hobby thanvocation. I love to be reminded that people just get together to share poemssometimes and have a community around that.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I’mfirst of all a lazy poet, which sounds unserious, when I’m actually a bitserious about being lazy. I am curious about theory and get a lot from it, butwhat I get is tangled up in my own feelings and concerns, not a grounding oftheory. I dabble, and anyone who actually adheres to anything would probablyfind it all messy and delinquent.. I really avoid any sense of having answersand don’t trust myself to have any. I’m also clear about things, like we livein ruinous landscapes populated by ghosts where we are intensely disconnectedfrom each other and desperately need to listen, and be neighbourly in a waythat goes against the whole capitalist-settler-colonialist apparatus of livingwe’re caught in. But that’s just happening, that’s not theory. Poetry is a wayto imagine otherwise and perhaps how to do that is the question.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

I’mnot sure there is one, to be honest, not in the larger culture. I think,outside of writers whose influence is directly tied to wealth, writers have amarginal influence. I’m not sure that’s bad, even if it’s materially bad forthe idea of making a living from writing. I am personally more comfortable inthe margins.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Ohabsolutely essential, it’s way too hard to see everything I’m doing, especiallysince I don’t often really know what I’m doing! I mean I do, of course, but a practicededitorial eye is always going to catch things and a good editor will havesuggestions that strengthen a poem or book immeasurably. I haven’t found itdifficult, far more often delightful, abundant.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

“Itwas always you who stopped you,” said by someone who knew me very well a longtime before I really did, and it wasn’t intended as advice. It functions asadvice because it’s accurate, I never forgot it, and it gets me to overrule myown hesitation when it comes to actually doing anything. Yes, I am an excellentprocrastinator, it’s a way of life I do not disagree with! But reminders arehelpful.

10- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Ihave something like a routine when I’m writing, which is pretty much a normalday of trying to read for a while in the morning and perhaps be outside for awhile and then write in the afternoon, and another one when editing or moreintensely rewriting, which is more like a free-for-all breakdown of routine andusually involves rather late nights where trying to get a line right evaporateshours at a time.

11- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

It’snot an interesting answer, but reading, always. The writer Sofia Samatar put itas being a “pleasure animal,” when reading and I relate, it’s entirely tangledwith thinking for me, and thinking with others is intimately tangled with anydesire I ever have to write.

12- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Woodsmoke,both from the seasonal fires familiar to living in California and the smell ofcreosote, a bush that flowers in the desert after monsoon rains, which is likeoils mixed with petrichor.

13- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

The artist Andy Goldsworthy might have as much influence on me as any poet, becauseotherwise I might think there’s no point in making anything when there’s theripples on sand in dunes or near the sea, or water flowing across stone. I don’treally differentiate between forms, a position Goldsworthy also has come tolate in his work, not differentiating between art and nature or civilizationand nature, simply recognizing that we’re always in nature, and always workingwith those elements whether we recognize them or not. I am not a scholar ofliterature, let alone poetry, but to me the origins of any poetic form existingor future are in things like birdsong, the movement of shadows, the shape ofstone, our voices and laughter when we walk through a city with each other. Themusic I like sounds a lot like these things too, and I find a lot of music bypoets mentioning music in their work. Jason Sharp, who frequently collaborates with the poet Kaie Kellough, is making music that just floors me and I always wantto write differently with.

14- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Thisis an enormous question so I’ll try to make it the shortest answer: Dionne Brand, Renee Gladman, Brandon Shimoda, John Keene, Zoe Todd, AM Kanngieser,Alice Notley

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

That’ssuch a dangerously open question! Visit Mexico City, touch the ephemeral lakethat forms in Death Valley in some very rainy winters, participate in a poetryreading in California, because somehow I’ve never done that in the place I’mfrom.

16- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Fieldgeologist or park ranger, the latter is still my backup plan. Give me a dayoutside and I’ll pick up garbage, I really don’t mind, it’s just nice to beout.

17- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Itwasn’t ever in conflict, really. I had an impulse to write and kept doing it,alongside doing other things. That’s still what I do. Mostly I do other things,even if I’m often thinking about writing in the background. I chose to pursuepublishing and participating in literature as an event, but even that wasmostly going with things as they happened. If things had gone otherwise I’dhave done something else, maybe I would have met people really into sailing, orgardening, and done those things. Sometimes these questions are as much amatter of community as anything else, and writing has led me to many people Ienjoy thinking with, talking with, making with, who do a variety of differentthings. If I had another art or profession, I think it would still be likethat.

18- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Tone, by KateZambreno and Sofia Samatar, and Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders.

19- What are you currently working on?

Abook in conversation with grasses and a mountain.