Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 22

March 19, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Monroe Lawrence

Monroe Lawrence (he/they) is a Canadianwriter. He is author of the poetry book About to Be Young and thechapbook Nice,. Winner of the Robin Blaser Prize for ExperimentalWriting and the Kim Ann Arstark Memorial Award, he has published writing in TheCapilano Review, Annulet: A Journal of Poetics, Black Sun Lit,The Brooklyn Review, Prelude, Flag + Void, and BestAmerican Experimental Writing, among other places. They hold an MFA inPoetry from Brown University and are a PhD candidate in Literary Arts at theUniversity of Denver. They were born on Vancouver Island and grew up inSquamish on Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw land.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

The process of writing that first book was very fulfilling.It was eight years ago, and I was a mere child! When it was published fiveyears later—almost by accident—I think I finally felt that I’d contributed to aconversation I cared a lot about, one I’d been listening to for years but not yetreally participated in. I think, too, that some of the art for art’s sakearmor I’d built up (you don’t need to publish, you do this for the love of thework itself, etc.) was swiftly demolished by the sheer joy of having, myself,produced one of those objects that, since I can remember, fascinated me somuch—a book. My second poetry manuscript Gravity Siren is made of thesame “material” as About to Be Young, I’d say, but twists thatmaterial into different shapes—bigger ones!

In my current fiction work, I’m interested in the distinctlanguage pressures of prose, the regimes of cliché that make fiction happen.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

Maybe acknowledging a certain pretension is due: poets justseemed smartest. They were interested in talking “about” what they were doing,about art and language and philosophy and hybridity, whereas fiction was a lotmore—in some ways—hermetic. Or a lot less academic. I don’t mind the academic. Thisis ironic because fiction actually wants to talk to regular people, whilepoetry builds a little indentured community for itself. (“Poetry is the scholar’s art” – Stevens.) The poets were more articulate at producingdiscourse about what they were up to, it seemed, so that’s one answer. And thatdid matter to me. Another answer is that poetry is an extremely portable, practicaltechnology for a person. The catharsis is reliable and swiftly delivered. I remembergrowing fascinated, though, with the rich, expansive world of experimentalpoetry, how the community self-interrogated and worked through its issues, suchas the crises of Conceptualism.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

I like sitting down and writing. I write a lot. But myprocess is . . . inefficient. Only .01% of the words I type make it into a publishablepiece of writing. I like to think this is because I set a really high standardfor myself and don’t settle for my lesser creations, but maybe I’m just stupid.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a “book” from the very beginning?

Generally, I am thinking about books from the beginning,these days. Aim high, or something . . . It’s an interesting question, though,because I have little interest in writing single, titled poems. I want to builda world, a landscape. I want a poem to feel like a droplet of microorganismswas placed on a page-slide, and the reader is observing a fascinating, like,plant that grew—but is perhaps not finished growing—up from the seed state, andeach page is a different instance of such a process.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I think the poets that matter to me are almost visualartists—sculpting text and flecks of letter, which nevertheless enregistervectors of mental sound. Reading those poems aloud can produce appreciablederivatives of the visual form, but it’s less interesting. I started out writingSLAM poetry in high school, and I think those experiences with writing designedto be heard, designed to be appreciated on first listen, led me to suspectnon-SLAM poems of being sort of ill-suited to being read aloud. Muchcontemporary poetry resembles SLAM poetry now, but I think it is still thevisual encounter that matters to me. One exception would be the talk poems ofDavid Antin.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

In fiction, I’m frequently trying to achieve conceptualpurchase on something that happened in the past. In poetry, I’m trying to builda pleasing, fondleable object out of words for a like-minded community. From amore scholarly perspective, I’m interested in what I’ve called “aesthetic pain”in poetry, poetry with language that enacts rather than merely describes shameby producing tears in the seemliness of the language. In essays on prose, I havebeen elaborating a term called “fictional pedagogy” to refer to depictions ofteaching, and I’ve been writing about speculative pedagogies. I like doing thatwork. But I rarely think of it while I’m writing poetry or fiction; they’re moreretrospective descriptions of finished thought.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

In some contexts, I would probably say that engaging withliterature and the notion of literary value is the most important thing a personcan do. Books and literary writing are tools we use to talk about practicallyall the things that really matter to, at least, me, things people rarely talkabout in other contexts. Again, in SLAM and perhaps poetry more broadly thereis this proselytizing impulse built into the role, like part of your job as awriter is to always encourage and nurture literary art, always encourage peopleto read and write, always be “on the clock” as an advocate for books and poetryand reading. I don’t mind that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

On occasion, I’ve militantly refused to share work withanyone, determining to “do it all myself” and “owe no one anything.” Hah. Butthose moments don’t last. I owe others everything. Like Philip Roth, I ideally wantmy mistakes to “ripen and burst” on their own, but sometimes I get impatientand will just confirm that a revision “is bad” with someone so I can write thenext draft.

The editors I’ve worked with professionally—Broc, Alicia—havebeen lovely and had a light touch.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

A mentor once said that the only commonality she’d everobserved between successful art practices was that the artist has to surprisethemself. Given the shortage of such commonalities between successfulpractices, in my experience, that has been really valuable to me. In fiction, onthe other hand, one often does have a goal or plan, so the trick is toaccomplish a task—kill George, build a frame narrative, get Aubrey downtown—whilehaving fun and mixing things up along the way.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

When I sustained a serious back injury four years ago, I decidedto be a little less single-minded about writing. For around a decade, though, Iwould wake up every day and work on writing all day.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I’m not sure. I am never stalled! Writing always happens.What doesn’t happen is good writing, and no amount of “inspiration” will changethat. Inspiration is not the common denominator for me. Quite often I’ll write acouple sentences distractedly on my phone on the bus and they’ll be moreinteresting than pages I spent hours on, writing that maybe felt totallymind-blowing and inspired at the time.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Moss.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

I like teaching, and draw on pedagogy in the sciences or,say, dance or studio art to inform my teaching. I’ve been interested in filmfor periods. Some of my best memories are sitting around late at night withfriends talking about music. In a way I’m obsessed with talking about prettymuch any art form.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

I like how raw and ingenious Anna Mendelssohn is. I like Tan Lin and work that distrusts the writerly. Most sentences in Proust are, for me,smarter than other writers’ entire oeuvres. The novel I recommend most is ViKhi Nao’s Fish in Exile. Incomparable in her vision and lush, sinuouslanguage, her range: Lisa Robertson. Andrea Actis’s Grey All Over was myfavourite book published in the last three years. I’ve been devouringJean-Phillipe Toussaint’s novels in French and am pretty obsessed with theAustralians, Patrick White and Gerald Murnane among others. The poet Alex Walton never publishes anymore but I spend a lot of time staring at his poems. Ilike the absolute political-verbal commitments of Verity Spott and Danny Hayward; I’m really glad they exist. I loved Avgi Saketopoulou and Ann Pellegrini’scareful use of psychoanalysis to express how gender and sexuality are neverfinished in Gender Without Identity. I reviewed late J.H. Prynnerecently here.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write my The Weather.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

Acting.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

It’s the best port in the worst storm.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Riders in the Chariot byPatrick White. The first film I’m thinking of is, I’ve watched Apichatpong’s Cemeteryof Splendor a lot. I’ve watched it maybe 5 times in different company. Itsatmosphere is this soothingly accurate blend of boredoms, desires and dreads.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Finishing a novel about Squamish and freewheeling inanother about hockey. Putting together some academic essays about findingpedagogy in literature.

March 18, 2025

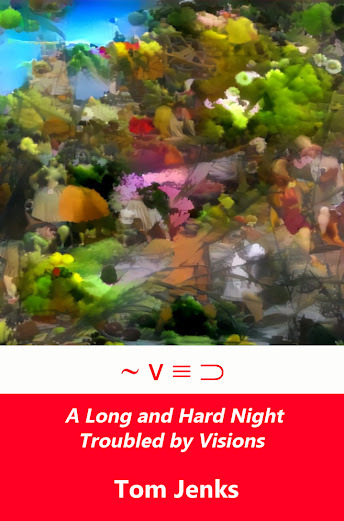

Tom Jenks, A Long and Hard Night Troubled by Visions

1984

After six days in theforest, I finally reached 1984. The tribe that lived

there welcomed me. I saton a mossy log, ate a toasted sandwich and

drank American cream sodafrom a hollow stone. Later, as the stars

wobbled above the treeline, we watched Torvill and Dean win gold at

the Sarajevo Olympics ona primitive television set installed in an

abandoned foxhole. The tribe’sleader, a tall man with an asymmetric

fringe and wearing atight silk blouse, asked me if I had been here

before. I said yes, along time ago, and my bike got stolen.

Notlong after I reviewed his rhubarb (Beir Bua Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], British poet and publisher Tom Jenks and I traded books, whichlanded me a copy of his collection of prose poems,

A Long and Hard NightTroubled by Visions

(Manchester UK: if p then q, 2018). I’m intrigued bythe pieces here, and Jenks’ work through the prose poem seem related to whatChicago Benjamin Niespodziany has been doing over the past few years; poem-cousins,perhaps, these odd short bursts of momentary capture. As the poem “MushroomForest,” for example, reads in full: “You have gathered a lot of flowers. You arebuzzing happily. Who is // watching you? Why are you angry? Where are you offto with your // snorkel?” Existing somewhere in that nether-realm betweenpoems, prose poems and prose, Jenks’ pieces each appear as a collection of sentencesassembled into prose poem structures. “He turned on the lights and saw throughus immediately.” the poem “inspector” begins, “I hadn’t read // all thosebooks. Topaz wasn’t descended from Marie Antoinette. // Carstairs’ odd socks weren’tan endearing eccentricity, but a calculated // affectation to obfuscate a deeplyuneventful personality.” This is a collection of sentences, set into poems, themselvesset into titled clusters, or sections: “SHRINKS,” “THE STRAWBERRY MOSHICOLLECTION,” “TOPAZ” and “THE DYSPHORIA SUITE.” What appear in Jenks’ pieces tobe narrative foundations are, instead, layerings of accumulation, setting oneidea or phrase or situation upon another, allowing for what the accumulationmight become or reveal. Jenks’ poems offer sly slides of prose, leaning into alyric surreal, shifting in and out of focus in really striking and unexpected ways.There is surprise behind these declarations, certainly, and it is interestinghow time moves through this collection; always an eye backwards, even whilelooking front, immediately ahead, or further afield.

Notlong after I reviewed his rhubarb (Beir Bua Press, 2021) [see my review of such here], British poet and publisher Tom Jenks and I traded books, whichlanded me a copy of his collection of prose poems,

A Long and Hard NightTroubled by Visions

(Manchester UK: if p then q, 2018). I’m intrigued bythe pieces here, and Jenks’ work through the prose poem seem related to whatChicago Benjamin Niespodziany has been doing over the past few years; poem-cousins,perhaps, these odd short bursts of momentary capture. As the poem “MushroomForest,” for example, reads in full: “You have gathered a lot of flowers. You arebuzzing happily. Who is // watching you? Why are you angry? Where are you offto with your // snorkel?” Existing somewhere in that nether-realm betweenpoems, prose poems and prose, Jenks’ pieces each appear as a collection of sentencesassembled into prose poem structures. “He turned on the lights and saw throughus immediately.” the poem “inspector” begins, “I hadn’t read // all thosebooks. Topaz wasn’t descended from Marie Antoinette. // Carstairs’ odd socks weren’tan endearing eccentricity, but a calculated // affectation to obfuscate a deeplyuneventful personality.” This is a collection of sentences, set into poems, themselvesset into titled clusters, or sections: “SHRINKS,” “THE STRAWBERRY MOSHICOLLECTION,” “TOPAZ” and “THE DYSPHORIA SUITE.” What appear in Jenks’ pieces tobe narrative foundations are, instead, layerings of accumulation, setting oneidea or phrase or situation upon another, allowing for what the accumulationmight become or reveal. Jenks’ poems offer sly slides of prose, leaning into alyric surreal, shifting in and out of focus in really striking and unexpected ways.There is surprise behind these declarations, certainly, and it is interestinghow time moves through this collection; always an eye backwards, even whilelooking front, immediately ahead, or further afield. Andbeyond all of that, a highlight has to be the poem “strikes,” near the end ofthe collection; a striking and sharp notation from the AMC television series MadMen (2007-2015). As the acknowledgements offers, the poem “documents every instanceof smoking in season 2,” and the effect is impressive. One almost wishes he’ddevoted a whole collection to such a thing (although one might garner how thatmight have worked from the focus on that second season).

1.47

Dr Stone smokes at hisdesk, in a monogrammed white coat. Bobbie

smokes in a bar, using acigarette holder. Don smokes at his desk. On

a globe behind him, the countriesof Africa are picked out in different

colours.

Bobbie smokes, taking acigarette from a gold case.

Bobbie smokes in Peggy’sapartment, talking on a yellow telephone.

Bobbie smokes, recliningon cushions. Salvatore smokes in a wicker

chair.

March 17, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dawn Web

Dawn Web, a Dalhousie Alum (BSc, focus in Neuroscience), iscompleting their degree in Creative Writing and Inter-Arts Entrepreneurship atDalhousie University. Dawn Web was born and raised in Ottawa, ON, and comesfrom a conservative mixed-race family of six. Dawn is a published author, anaward-winning dancer, a multi-instrumentalist, a successful emerginginterdisciplinary artist, a scientist, an educator, a publisher and anentrepreneur. Dawn stumbled upon writing "by accident", seekingcreative outlets for expression, regulation and connection. Dawn’s debut poetrycollection (the first of six volumes), Red Corner: a poetry anthology,within the Colours Collection. Red Corner explores themes of identity,queer and political issues, love, growth, perseverance, and navigatingintergenerational trauma aftermath. Dawn founded Vivid Illusion CreativeStudios, a Canadian inter-arts publishing house, online art store andnetworking platform for artists to host and share their creative work. Web alsohosts Plum Poetry Night (Spoken Word Series) on Tuesdays in Halifax, whichinvolves a feature artist performance, poetry open-mic, and creative writingworkshop led by Dawn themself.

How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous one?How does it feel different?

This is a tough questionto answer. I used to worry that I would never make anything as good as my poem “Flashbacks,” which is published in Fathom Creative WritingJournal “Growth”on pages 47-48 and Red Corner on pages 78-79. Maybe the content in “Flashbacks” because it was such a large obstacle I wasovercoming or because I felt unworthy and insecure. I had such a grandiosereaction from peers and strangers in response to this piece of work and thoughtmaybe that was the only thing people would like coming from me. But I guess, insome ways, my earlier work has a stronger focus on rhyme and free verse aroundsoul-sucking events because my poetry almost solely came from moments ofcoping. It has since evolved from poetic journal entries into writing practice,where I write about various topics with a breadth of beauty and engage in morepoetic form. I struggled to write poetry from a happy place; my poem “Snakes” on pages 214-215 of Red Corner uses imagery amongmetaphors to explore this theme in my attempts to navigate feelings of joy andlearn how to allow myself to feel happy.

How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I wanted to write songs, but I was rarelysatisfied with the result. As I grewolder with more literary exposure, I realized I had been writing poetry! Thewords came easily, but I could not connect the words with melody lines to findadequate pairings. Writing poetry feels natural which gives me self-confidence.Poetry is cunning — the ability to connect with someone on an abstract ideathat can mean two very different things to two individuals and yet, bring themcloser to one another. That is beautiful. I love eliciting images and thoughtsand evoking feelings in others with something that does not always have to “makesense” and still be able to deliver an important message through play.

How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to avoid editing my work as it feelsquite daunting, but the immediate transfer of literary work from pen to keyshas proven most effective in my form development and editing process (typing,printing, pen and paper, re-writing, and re-typing). I find my work comes onrather rapidly and lock-in pen to paper, typically. But ultimately, length of aproject varies drastically based on my life circumstances.

Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I have included a poemtitled “Wheredoes a poem begin”. I heard about your online journal called periodicities through Dani Spinosa, which prompted this poem surrounding my lifeexperiences. But I think to answer your question directly, it’s both!

Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I lovedoing reading, my work is meant for spoken word. Which is why I have recordedan audiobook for Red Corner, which will be released soon. However, I do notlike promoting my work, it feels icky.

Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

Well,that is a loaded question. I am trying to better understand my world throughwriting, and hope that I can bridge the gap to bring a greater understanding ofdifferent perspectives to others through my work.

What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I thinkthat is may be different for everyone in terms of their intentions. But, for meit comes back to storytelling in the oral tradition: for entertainment, forconnection, for education, or whatever else it may be.

Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

I thinkit can be difficult if you guys don’t gel. I think it is essential forcertain projects, where not so much for others. But there always been a mistakesomewhere, no matter how many eyes view it.

What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Thereis growth only outside comfort, so listen to your body especially when you don’t want to, it remembers and is trying to tell you something.Listen to what is behind the rejection, it will guide you in the rightdirection.

Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

I gothrough phases. Routines only stick around for so long until they becomemundane and you get stuck. It is important to dedicate specific time forcreating and not wait for inspiration to come to you. Some amazing pieces comefrom routine and dedication where other strike a more spontaneous leap. It isvital to have a balance.

Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

Goingout and engaging with nature and putting a timer on to start some freewriting.

Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Hmmm.Sense of smell and sense of home. I want to say, smell of the fresh salty airoff the ocean.

DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Definitely,all. I find alot of my work will come from my dreams or nightmares I have aswell.

Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Idraw inspiration from Shane Koyczan’sinterdisciplinary and mixed media delivery. Whitney Hanson’s expression of vulnerability and connection to poetics. Ilove The Lumineers for their story telling among other ballads. Saeed Jones, writes “howwe fight for our lives” in such an enchanting and poetic style. Nancy Pague’sWrite Moves was assigned as a course textbookfor a class with BeccaBabcock, and it is still a book I use as reference orguide now and then. The rhythm executed by Josie Balka intertwininga classic Dr.Seuss rhyming scheme.

Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I wouldlike to live in Spain.

If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I haveworn so so many hats. I have done so many different occupations—I’m a jack of all trades, so to speak. So, I think that Iactually did the reverse. I had to try everything else before I could landhere.

Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

My momand my professor Dr. Becca Babcock, were the first people to believe in mywriting when I felt brave enough to share. Their encouragement led me tocontinue.

Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

21things you may not know about the indian act by Bob Joseph, and Introduction toInternal Family Systems by Richard Schwartz, 101 Essays that will Change theway you think by Brianna Wiest. Movie: The Six Triple Eight

Whatare you currently working on?

You’ll just have to follow along to see. You can follow me oninstagram @dawnweb & my business @vividillusion.studio and sign-up for thestudios newsletter www.vividillusion.studio

March 16, 2025

, from the green notebook

, reading Jen Tynes, Brenda Hillman, Rob Taylor + Joy Williams,

Michiganpoet Jen Tynes posted this excerpt of Brenda Hillman’s “Dear emerging,pre-emerging & post-emerging poets,” to social media earlier today,originally published online via Too Little / Too Hard, a site for“Writers on the intersections of work, time and value”:

When you feel paralysedby the pointlessness of temporary fashion, or when dull and predictable work islauded, try new things that will surprise you as you work for the joy of theprocess, remembering that all a writer needs are four true readers & one ofthem can be a tree. Never look at your phone while walking downstairs. Do notdestroy your body by self-medicating under poetic stress. Just write new poems& read them to your community. Keep the ego in balance because the egoproject is doomed to fail. If you don’t receive the rewards you deserve from“the outside world”—and you very likely will not—try to celebrate the good workof others; hold love in your heart; work for justice for humans &non-humans & keep writing.

Keep writing, most writerly advice offers. Keepgoing. Easier said than done, we all know. I work like a maniac for acouple of years on a manuscript, six to eight months further pushing the bookonce it’s published, and a royalty cheque a year or two later that won’t evencover a single outing of weekly groceries. It isn’t that difficult to feeldiscouraged, certainly. Keep going, keep moving, keep pushing. What are wedoing, exactly? What is this for?

Tynesherself, from her chapbook Mushrooms Yearly Planner (2021): “We haveevery right / to be here muscle memorized.”

*

Awashin the beach-head of Bank Street traffic, another coffeeshop morning, OttawaSouth. I’m reading through Vancouver poet and editor Rob Taylor’s pandemic-era poetrycollection Weather (2024), his afterword to which includes this curiouscaveat:

Then, in the early daysof the COVID-19 pandemic, which had all of us searching for answers, I stumbledupon mine. Quarantined at home with my wife and two pre-school-aged children inour two-bedroom apartment, I had no choice but to venture outside to work inpeace.

Iunderstand that sentiment, especially from the viewpoint of living in an apartment,which would have provided an entirely different array of human interactionsthan where we’re at: three bedroom house, basement, fenced-in yard. Thebenefits of a particular kind of suburban lot, and the three months’ worth ofnotes across the onset of pandemic lockdown that evolved into my non-fictionhybrid, essays in the face of uncertainties (2022). We managed, if youcan call it thus, fully aware we were in a better position than some. My homeoffice, for example. In the early 1990s, when I lived with partner andpreschooler in a one-bedroom Centretown apartment, the only way I could thinkwas to leave for the coffeeshop, come evening. The stress was real.

Seekinga pandemic-era calm, where I delved into chaos. Peace is a relative term, afterall. And the possibilities of space.

“thespan it takes,” Taylor writes, “to read a poem / we can’t yet see.”

*

Aninteresting new interview with Joy Williams, conducted by Adrienne Westenfeld,lands online at Esquire, speaking to “the decades she spent contributingto Esquire, from the editors who shaped her career to the boxes ofoutraged letters about her most infamous story.” I love the detail thatWestenfeld shares of sending Williams the questions, writing in herintroduction that “Nowadays the eighty-year-old author lives in the Arizonadesert, where she communicates by typewritten correspondence. When we sent overa questionnaire to Williams, what we received in return surprised even us. Onvintage Esquire letterhead emblazoned with Hills’s name [the late RustHills, Esquire’s longtime fiction editor, who was married to Williamsfrom 1974 until his death in 2008], Williams sent back typewritten answers toour questions, all written in the blunt, lucid voice we know and love.”

Interviewssuch as these remind of how early editors in such highly visible positions canbe so essential for a writer’s career, from a young Joy Williams publishingstories in Paris Review and Esquire, to my own knowledge ofinfamous Canadian editor and broadcaster Robert Weaver (1921-2008), from histime as fiction editor of Saturday Night magazine, or his yearsbroadcasting the work of a slew of younger Canadian writers on CBC Radio. Backwhen radio held a larger cultural attention, he created a variety of shows inthe years spanning 1948 to 1985, including Anthology, that featuredearly works and appearances by Alice Munro, Mordecai Richler, Timothy Findley,George Bowering, Margaret Atwood and Leonard Cohen. Many of whom we considerCanadian canon owe their careers to the work of Robert Weaver. Will the same besaid in the future of certain editors at This magazine, Maisonneuveor The Walrus?

Inher Esquire interview, Williams responds to her time and experiencesthrough the magazine, and of being edited by Gordon Lish, his pen strikingthrough whole sentences, paragraphs. She answers: “I learned a lot. I had beengetting a little wordy.” The sent questions and her single responses don’tallow for a back-and-forth, and there are more than a couple of her responsesthat scream for the inclination of follow-up. Still, her responses show athoughtful combination of quickness, intuitive self-awareness and sharpterseness, offering only what is absolutely required. Her response to questionsix, the single, pointed: “No.”

March 15, 2025

today is my fifty-fifth birthday,

Where does the time go? Oh, I don't even ask those questions anymore.

Do you remember where I was last year?

I've been wearing my 'birthday boy' pin since Monday, given I prefer to take the whole week as 'birthday,' as you already know. My birthday always falls into March Break, so there were only rarely opportunities to acknowledge such with school pals from the farm, especially with mother's ill-health and the usual array of distance and farm work.

Where does the time go? Oh, I don't even ask those questions anymore.

Do you remember where I was last year?

I've been wearing my 'birthday boy' pin since Monday, given I prefer to take the whole week as 'birthday,' as you already know. My birthday always falls into March Break, so there were only rarely opportunities to acknowledge such with school pals from the farm, especially with mother's ill-health and the usual array of distance and farm work. When I sent this pic to my brother Darren the other morning, he responded with a face-slap emoji. It matters not! We take the whole week.

What is happening currently? Fifty-five, hm. I care not for the number, but I don't feel much different than five years ago, or twenty-five. Age might be a number, and we all imagine ourselves held at a particular age, with mine being well younger than this. It is a strange thing, certainly.

Our young ladies (Rose has been requesting lately I keep her image off the internet) have been in enough activities over the past few months--Aoife's ukulele lessons, German classes, Embers, ringette practices and games, and Rose's practices and performances through the Anglican Girls' Choir--that they both rebelled against any March Break camps or activities, preferring to simply have a few days they didn't have to do anything or go anywhere. Even still, Rose had a choir practice, and each of them had an afternoon with one of their friends. We also managed a couple of days earlier in the week at the cottage, slipping the bounds of the National Capital Region for Sainte-Adele (we did manage New Year's there, which I seem not to have posted about, as well as Thanksgiving). We went to the cottage, and I sat nearly three days with notebook, and a mound of books I never quite got through as much as I would have hoped. The snow was perfect for building, but Rose wasn't feeling up to it, so we let them lay fallow for a bit. Once they're back at school it will be back at the routine and the running around (multiple days have them either back-to-back or overlapping or simultaneous activities, so I get it).

I've been feeling underwater since November, but I can almost see the light at the end of the tunnel, he says, optimisticallly (unless that's simply me having a stroke, which isn't impossible). Next week is VERSeFest, in case you're around (I've been Artistic Director and Board President for over a year now, which I'm still confused by). I'm producing a new chapbook by American poet Eileen Myles for the event, and our schedule is packed with incredible performers. Have you gone through our list yet? The workshops by Myles and Phil Hall might have a space or two left as of today, but who knows. Things fill up fast.

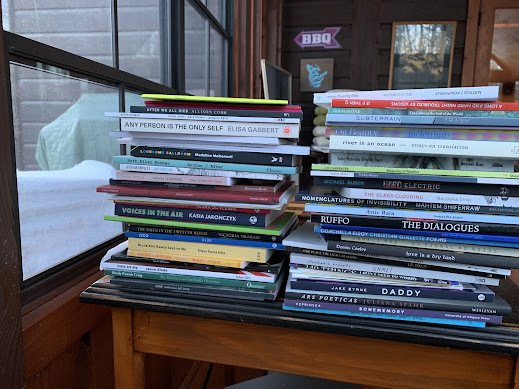

I've been feeling underwater since November, but I can almost see the light at the end of the tunnel, he says, optimisticallly (unless that's simply me having a stroke, which isn't impossible). Next week is VERSeFest, in case you're around (I've been Artistic Director and Board President for over a year now, which I'm still confused by). I'm producing a new chapbook by American poet Eileen Myles for the event, and our schedule is packed with incredible performers. Have you gone through our list yet? The workshops by Myles and Phil Hall might have a space or two left as of today, but who knows. Things fill up fast.These days, I'm hoping to be circling the ends of the manuscript for "the green notebook" (some two hundred single-spaced manuscript pages, if you can believe it), as well as "the genealogy book" (excerpts of both projects I've been posting for months now over at my substack), two different creative non-fiction/book-length essay projects I've been deep within, for well over a year now (most likely longer than that). I'm not entirely sure where I might send either of these manuscripts, but I am hoping to have something worth sending out around May or June, possibly. I already completed a further manuscript of short stories last year (see one of those stories here, which landed online this week at Leon Literary Review), a process of some seven or so years. The novel-in-progress that plays with certain of the same characters that move through both collections of short stories (begun during that first Covid summer) I've yet to complete, so once those two larger non-fiction projects are completed, I'm hoping I can more seriously work to complete the thing (should I send it to that publisher who turned down my short stories with "we can't sell short stories. let us know if you have a novel"?). It would be good to get that project finished and out, since I've so many further thoughts of what might be fun to work with, work on, etcetera, beyond that. I mean, my novel-in-progress "Don Quixote" was started in 2007, after all. I'm still adding short essays to a slowly-growing manuscript, "reading in the margins : essays on prose writers," the bulk of which I've also been posting to my enormously clever substack. I'm in the midst of at least a further four pieces at the moment.

And poems? Oh, I've been poking at poems for a while now, although far slower than I would prefer. I'm still mid-way through a manuscript of response-poems, some of which has already appeared online; as I've been describing the project:

Fair bodies of unseen prose is an homage text for, around and after American poets Laynie Browne and Rosmarie Waldrop, furthering my exploration around and through the lyric sentence and prose poem. All poem titles (which appear in italics above each brief prose poem) are taken in order from the last line or phrase of each poem in Browne’s In Garments Worn By Lindens (Tender Buttons Press, 2019), itself an homage text to Rosmarie Waldrop, with all of Browne’s titles taken from Waldrop’s Lawn of Excluded Middle (Tender Buttons Press, 1994). As my own sequence progresses, echoes of texts by both poets resound throughout, especially from Browne’s In Garments Worn By Lindens and Practice Has No Sequel (Pamenar Press, 2023), Rosmarie Waldrop’s Blindsight (New Directions, 2003) and Gap Gardening: selected poems (New Directions, 2016), and the collection Crosscut Universe: Writing on Writing from France, edited/translated by Norma Cole (Burning Deck, 2000).

In early 2023, I reviewed three recent titles by Laynie Browne, and quickly realized just how much affinity there was between her work and my own, an element of which is certainly due to our shared love of, and deep influence from, the work of Rosmarie Waldrop. Browne and I soon exchanged books, and In Garments Worn By Lindens prompted this response.

I've also been prodding at some longer, extended poems, really gearing up, it would seem, to a manuscript I'm itching to get to (I've been assembling titles and scraps for a few years now, honestly), once the non-fiction projects are completed. As well, there's a further poetry project I've been working on for about nine weeks or so, but it is too early to speak of such a thing as yet. One poem a week, responding to prompts. I'm hoping I can get to a year or more, if possible, get a book out of this thing. We shall see. Beyond that, my poetry collection

the book of sentences

(University of Calgary Press) is out in mid-October (it has a cover!), a direct follow-up (with cover design echoes) to

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press, 2022). Should I let them know I completed a third in the trilogy well over a year ago? Once we're further through the process of this current collection, I'll most likely send that one along. A trilogy of poetry titles, if you can believe it. Separately,

Snow day

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025) exists as a kind of side-project simultaneous to the gap between the book of smaller and the book of sentences, with a further manuscript of sequences simultaneous to the gap between the book of sentences and "Autobiography" (the manuscript for that second gap title is currently sitting with a Canadian press for consideration). I also have a forty-ish page essay out soon with Spuyten Duyvil as well, once I've the attention span to sit down with the final manuscript and get that to the publisher, A river runs through it: a writing diary , collaborating with Julie Carr, an essay composed around the call-and-response work we did across early Covid-lockdown, produced as the chapbook

river / estuaries

(above/ground press, 2023), and since carved up and reworked in our own individual directions. Probably April or May? The only hold-up right now is my own attention span. And then, of course, the manuscript of short short stories I've been poking away at for more than a decade, as a follow-up to

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014). Where would I even send that? I've been posting short excerpts from that manuscript over at my substack for a while as well, if such strikes your interest.

Oh, and I'm doing a reading tomorrow in Ottawa with a bunch of folk, if such strikes your fancy.

I'm considering it the launch of Snow day, so you should come out to that.

I've also been prodding at some longer, extended poems, really gearing up, it would seem, to a manuscript I'm itching to get to (I've been assembling titles and scraps for a few years now, honestly), once the non-fiction projects are completed. As well, there's a further poetry project I've been working on for about nine weeks or so, but it is too early to speak of such a thing as yet. One poem a week, responding to prompts. I'm hoping I can get to a year or more, if possible, get a book out of this thing. We shall see. Beyond that, my poetry collection

the book of sentences

(University of Calgary Press) is out in mid-October (it has a cover!), a direct follow-up (with cover design echoes) to

the book of smaller

(University of Calgary Press, 2022). Should I let them know I completed a third in the trilogy well over a year ago? Once we're further through the process of this current collection, I'll most likely send that one along. A trilogy of poetry titles, if you can believe it. Separately,

Snow day

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2025) exists as a kind of side-project simultaneous to the gap between the book of smaller and the book of sentences, with a further manuscript of sequences simultaneous to the gap between the book of sentences and "Autobiography" (the manuscript for that second gap title is currently sitting with a Canadian press for consideration). I also have a forty-ish page essay out soon with Spuyten Duyvil as well, once I've the attention span to sit down with the final manuscript and get that to the publisher, A river runs through it: a writing diary , collaborating with Julie Carr, an essay composed around the call-and-response work we did across early Covid-lockdown, produced as the chapbook

river / estuaries

(above/ground press, 2023), and since carved up and reworked in our own individual directions. Probably April or May? The only hold-up right now is my own attention span. And then, of course, the manuscript of short short stories I've been poking away at for more than a decade, as a follow-up to

The Uncertainty Principle: stories,

(Chaudiere Books, 2014). Where would I even send that? I've been posting short excerpts from that manuscript over at my substack for a while as well, if such strikes your interest.

Oh, and I'm doing a reading tomorrow in Ottawa with a bunch of folk, if such strikes your fancy.

I'm considering it the launch of Snow day, so you should come out to that.Much as last year this time, I still work to dismantle my home office, for the sake of our young ladies having their own rooms. Rose served me an eviction notice some time ago. This is all taking too long.

March 14, 2025

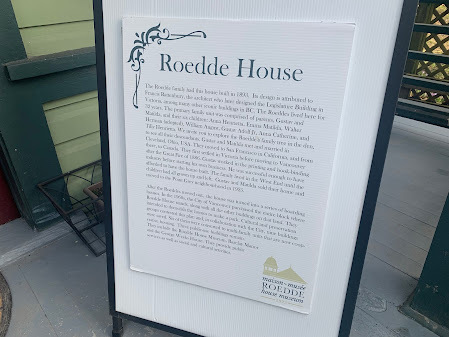

our reading brings all the poets to the yard : Vancouver, part two

[see part one here] What a stunning event in Vancouver! Christine and I read recently via Poetry in Canada at Simon Fraser University, thanks to the machinations ofStephen Collis and Isabella Wang. After my prior post, in which I was attempting to list my other Vancouver events over the past few years, Diane Tucker reminded me that I went through Vancouver in 2010 (I know I was once or twice a year from 1997 to 2006, but anything beyond that I hadn't the notes for), which would have been a Talonbooks event, most likely the one at Anza Club where I read with bill bissett and Adeena Karasick, touring around a bit with the two of them (including in Edmonton, and I think Calgary). That was a good trip. The same venue they had John Newlove read in 1999 for the chapbook I produced of his (I was fortunate enough to be in town for such), being his first time back in Vancouver reading in fourteen years (that was quite an event, on multiple levels).

[see part one here] What a stunning event in Vancouver! Christine and I read recently via Poetry in Canada at Simon Fraser University, thanks to the machinations ofStephen Collis and Isabella Wang. After my prior post, in which I was attempting to list my other Vancouver events over the past few years, Diane Tucker reminded me that I went through Vancouver in 2010 (I know I was once or twice a year from 1997 to 2006, but anything beyond that I hadn't the notes for), which would have been a Talonbooks event, most likely the one at Anza Club where I read with bill bissett and Adeena Karasick, touring around a bit with the two of them (including in Edmonton, and I think Calgary). That was a good trip. The same venue they had John Newlove read in 1999 for the chapbook I produced of his (I was fortunate enough to be in town for such), being his first time back in Vancouver reading in fourteen years (that was quite an event, on multiple levels).

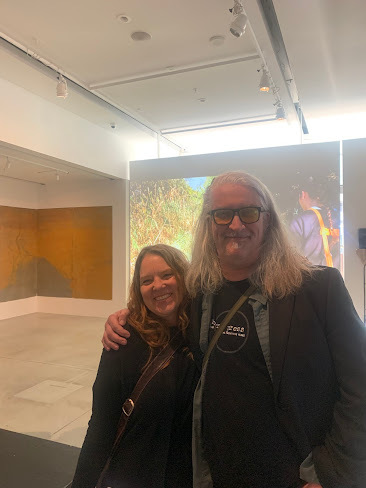

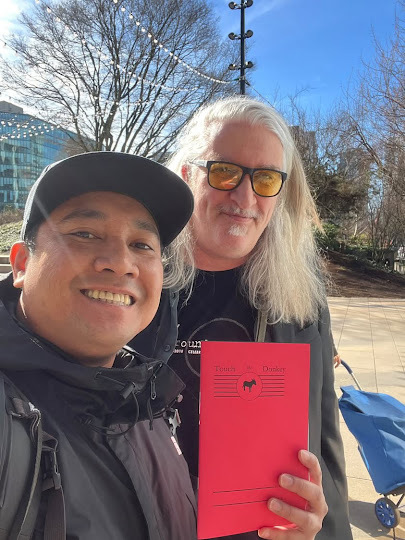

[above: rob and Geoffrey Nilson; left: rob and Mckenzie Strath] I've been enjoying the evolution of Christine reading from

Toxemia

, maybe a half dozen times or more by now, each reading more vibrant than the prior (the book really has to be read and/or heard to be believed; did you see the essay I wrote on it?). Collis referred to us as a poetry "power couple," which is hilarious and strange, and also asked anyone in the room published through above/ground press to raise their hand (at least half the crowd, which was startling, in a certain way). The event held a standing-room only crowd, packed with some of the best of what Vancouver poetry has to offer, including Scott Inniss, Rob Manery, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Christina Shah, Fred Wah and Pauline Butling, Daphne Marlatt, Catriona Strang, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Fiona Lam, Elee Kraljii Gardiner, Geoffrey Nilson, Michael Turner, Diane Tucker, Heather Haley, Peter and Meredith Quartermain, Jen Currin, Jami Macarty, Brook Houglum, Aiden Chase, Phinder Dulai, Mckenzie Strath, Rahat Kurd and plenty of others (with a handful of regrets, including Anne Stone, who it would have been lovely to see (has it really been twenty years? and twenty-six since we toured Canada together?), and Thor Polukoshko, who I will have to meet at some future visit. An incredibly warm and supportive crowd. And we even sold books! It was also exciting to meet a handful of poets I hadn't yet met in person, including at least half a dozen above/ground press authors.

[above: rob and Geoffrey Nilson; left: rob and Mckenzie Strath] I've been enjoying the evolution of Christine reading from

Toxemia

, maybe a half dozen times or more by now, each reading more vibrant than the prior (the book really has to be read and/or heard to be believed; did you see the essay I wrote on it?). Collis referred to us as a poetry "power couple," which is hilarious and strange, and also asked anyone in the room published through above/ground press to raise their hand (at least half the crowd, which was startling, in a certain way). The event held a standing-room only crowd, packed with some of the best of what Vancouver poetry has to offer, including Scott Inniss, Rob Manery, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Christina Shah, Fred Wah and Pauline Butling, Daphne Marlatt, Catriona Strang, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Fiona Lam, Elee Kraljii Gardiner, Geoffrey Nilson, Michael Turner, Diane Tucker, Heather Haley, Peter and Meredith Quartermain, Jen Currin, Jami Macarty, Brook Houglum, Aiden Chase, Phinder Dulai, Mckenzie Strath, Rahat Kurd and plenty of others (with a handful of regrets, including Anne Stone, who it would have been lovely to see (has it really been twenty years? and twenty-six since we toured Canada together?), and Thor Polukoshko, who I will have to meet at some future visit. An incredibly warm and supportive crowd. And we even sold books! It was also exciting to meet a handful of poets I hadn't yet met in person, including at least half a dozen above/ground press authors.

[above: Christine + Christina Shah and her amazing coat of many colours; left: Scott Inniss and myself, closing out the evening; an awesome reminiscent of Kevin Stebner] And for drinks, also, landing at a pub I know for certain I'd been to before, being the first place (after which reading I do not recall) I met Lisa Robertson. When was that? We got to hang with Manery, Collis, Lusk (a descendant of the Lusk who named Luskville, Quebec, I'll have you know; the location Monty Reid wrote of in The Luskville Reductions), Wang, Shah: absolutely grand. Isabella thought I was imaginary and magical! And I've honestly thought her completely the same, if we're being honest. Did you know a second full-length collection is out soonish? I have shirts I still wear older than this kid; how is her work so damned good?

[above: Christine + Christina Shah and her amazing coat of many colours; left: Scott Inniss and myself, closing out the evening; an awesome reminiscent of Kevin Stebner] And for drinks, also, landing at a pub I know for certain I'd been to before, being the first place (after which reading I do not recall) I met Lisa Robertson. When was that? We got to hang with Manery, Collis, Lusk (a descendant of the Lusk who named Luskville, Quebec, I'll have you know; the location Monty Reid wrote of in The Luskville Reductions), Wang, Shah: absolutely grand. Isabella thought I was imaginary and magical! And I've honestly thought her completely the same, if we're being honest. Did you know a second full-length collection is out soonish? I have shirts I still wear older than this kid; how is her work so damned good?

The following morning allowed a quiet few minutes at Sylvia's Bar downstairs with the books I picked up from The Paper Hound--Patrick Lane's Winter and Kevin Killian's posthumous Selected Amazon Reviews--before breakfast with Vancouver poet (and above/ground press author) Renée Sarojini Saklikar, who wasn't able to make the reading. Oh, she is delightful. And we got to hear some good stories about her growing up the daughter of a United Church minister, including in parts of Quebec, just north of Montreal.

The following morning allowed a quiet few minutes at Sylvia's Bar downstairs with the books I picked up from The Paper Hound--Patrick Lane's Winter and Kevin Killian's posthumous Selected Amazon Reviews--before breakfast with Vancouver poet (and above/ground press author) Renée Sarojini Saklikar, who wasn't able to make the reading. Oh, she is delightful. And we got to hear some good stories about her growing up the daughter of a United Church minister, including in parts of Quebec, just north of Montreal.

After breakfast, Christine retired to our room, and I headed downtown to catch a conversation with Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman and Nastaran Saremy to accompany a show there by Sniderman, and meet up with American poet Deborah Poe (another above/ground press author, although I think we're due for another chapbook soon), who was in town for same. Can you believe it has been twelve years since I've seen her, back when we first met in Ottawa? Sniderman's show, including video footage, and conversation were extremely interesting, as he spoke of walking in terms of solidarity (very different from the Vancouver Walking of Meredith Quartermain's flaneur, or the British tradition of 'walking,' as articulated through such as Mark Goodwin's Steps); as the British tradition evolved into an acknowledgement of owned, preserved space, Sniderman's project comes out of attempting to counteract erasure, acknowledging solidarity with workers, the revolution and the tensions of unmapping. His is an anti-colonialist project to restore knowledge to what had been deliberately revoked. The core gesture of the project is of the settler refugee, he said, listening to the shared land. [I am possibly mangling some of the intentions around this project, so I recommend you look up his work and see for yourself]

After breakfast, Christine retired to our room, and I headed downtown to catch a conversation with Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman and Nastaran Saremy to accompany a show there by Sniderman, and meet up with American poet Deborah Poe (another above/ground press author, although I think we're due for another chapbook soon), who was in town for same. Can you believe it has been twelve years since I've seen her, back when we first met in Ottawa? Sniderman's show, including video footage, and conversation were extremely interesting, as he spoke of walking in terms of solidarity (very different from the Vancouver Walking of Meredith Quartermain's flaneur, or the British tradition of 'walking,' as articulated through such as Mark Goodwin's Steps); as the British tradition evolved into an acknowledgement of owned, preserved space, Sniderman's project comes out of attempting to counteract erasure, acknowledging solidarity with workers, the revolution and the tensions of unmapping. His is an anti-colonialist project to restore knowledge to what had been deliberately revoked. The core gesture of the project is of the settler refugee, he said, listening to the shared land. [I am possibly mangling some of the intentions around this project, so I recommend you look up his work and see for yourself] [Deborah Poe and myself, at Audain Gallery, Simon Fraser University] Deborah Poe had to get back home, and wasn't sticking around, which was a bit disappointing. So from there, I wandered a bit; there had been a plan to meet up briefly with Clint Burnham (another above/ground press author, you know), but that got pushed until later, so I wandered, and headed over to MacLeod's Books, a perpetual favourite and a Vancouver institution (but couldn't find anything there I might have needed). For years across the late 1990s and into the 00s I visited there, picking up numerous titles to add to my reading list, although I think my requirements have shifted over to what The Paper Hound currently offers.

[Deborah Poe and myself, at Audain Gallery, Simon Fraser University] Deborah Poe had to get back home, and wasn't sticking around, which was a bit disappointing. So from there, I wandered a bit; there had been a plan to meet up briefly with Clint Burnham (another above/ground press author, you know), but that got pushed until later, so I wandered, and headed over to MacLeod's Books, a perpetual favourite and a Vancouver institution (but couldn't find anything there I might have needed). For years across the late 1990s and into the 00s I visited there, picking up numerous titles to add to my reading list, although I think my requirements have shifted over to what The Paper Hound currently offers. Hey, there are the mountains! I remember those mountains. Those! Over there!

Hey, there are the mountains! I remember those mountains. Those! Over there!

After heading back to the hotel (finally), I met up with Vancouver poet Ivan Drury and his young lad (they wandered over by bike after the lad woke from his nap), as we walked along the beach at English Bay for a bit (the view was spectacular--I'm not used to seeing so many boats, let alone the big transport ships--but there was a chill in the air), but then decided to get back into Sylvia's Pub for a drink and a bite, which the young lad quickly warmed to. He had much to say, you know. And colour. And doesn't Ivan have the kind of smile that would light up any room? He had some interesting thoughts on work poetry that I'm hoping he expands on (he's currently working on a piece for periodicities on same, which I'm very looking forward to seeing). He even gave me some chapbooks! I always appreciate that.

After heading back to the hotel (finally), I met up with Vancouver poet Ivan Drury and his young lad (they wandered over by bike after the lad woke from his nap), as we walked along the beach at English Bay for a bit (the view was spectacular--I'm not used to seeing so many boats, let alone the big transport ships--but there was a chill in the air), but then decided to get back into Sylvia's Pub for a drink and a bite, which the young lad quickly warmed to. He had much to say, you know. And colour. And doesn't Ivan have the kind of smile that would light up any room? He had some interesting thoughts on work poetry that I'm hoping he expands on (he's currently working on a piece for periodicities on same, which I'm very looking forward to seeing). He even gave me some chapbooks! I always appreciate that.Christine eventually met us downstairs as we were soon to head over to Rob Manery's house (another above/ground press author; he's reading in Ottawa this weekend!) to have dinner with Rob, his partner Robyn Laba (her day-job and her artistic practice both sound fascinating, honestly) and their teenage lad, with a brief drop-in by Burnham, which was good. Why didn't I take any pictures of that? I was probably talking too much. I always want to ask Burnham about the late, lamented 1990s newsprint publication boo magazine he was involved in (there never seemed the right moment, the rare times we've been in a room together over the past twenty years), as I was quite fond of the few issues I saw. Whatever happened to that? What was that all about? I have many questions.

And then the next morning, as our direct plane cancelled, so had to head home through Toronto instead (and landing home at least three hours later than originally planned), which got us home just in time to catch our young ladies for bedtime.

And then the next morning, as our direct plane cancelled, so had to head home through Toronto instead (and landing home at least three hours later than originally planned), which got us home just in time to catch our young ladies for bedtime.March 13, 2025

J.R. Carpenter, Measures of Weather

the coast establishes a sortof islet

within common humanrelation

the months leave theirnotches on me

the island has no need ofme

you want something tohappen

and nothing does

what happens to the coast

does not happen to thediscourse

like a cork on the waves

I remain motionless

boredom is not far frombliss:

it is bliss seen from theshores of pleasure (“Of Coast”)

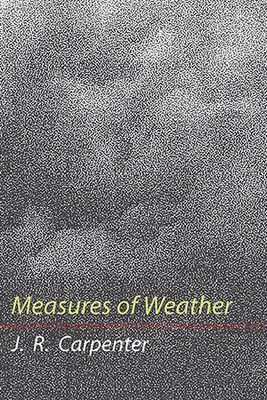

United Kingdom-based Canadian poet J.R. Carpenter’s latest is

Measures of Weather

(Swindon UK: Shearsman Books, 2025), a book that self-describes as a collection“about more than just weather. What isn’t weather? Weather here is a stand-in,for the elemental, the transitional, the ungovernable. And what does it mean tomeasure?” The collection offers a suite of sharp lyrics, each holding titlesthat echo off each other: “Of Fire,” “Of the Moon,” “Of Time,” “Of Witches,” “OfDew,” “Of Nothing.” There is something of the title-thread reminiscent of what California poet Elizabeth Robinson has been working on for a while now, such as in her

Excursive

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2023) [see my review of such here] and

On Ghosts

(Solid Objects, 2013) [see my review of such here], to Anne Carson’s infamouscollection Short Talks (London ON: Brick Books, 1992), with each Carsonprose poem in the collection titled “Short talk on _____.” The title-structureallows for a kind of ongoingness, an umbrella under which anything might happenor occur, including threads that might relate to the specifics of each title.For Carpenter, she offers a measurement beyond immediate measurement, composinga sequence of lyric meditations on physical, intellectual and even outer spaceand celestial bodies. “2 August 1786 // I want to trouble you / in absence,”the sequence “Of a New Comet” begins, “with the following / imperfect account[.]”

United Kingdom-based Canadian poet J.R. Carpenter’s latest is

Measures of Weather

(Swindon UK: Shearsman Books, 2025), a book that self-describes as a collection“about more than just weather. What isn’t weather? Weather here is a stand-in,for the elemental, the transitional, the ungovernable. And what does it mean tomeasure?” The collection offers a suite of sharp lyrics, each holding titlesthat echo off each other: “Of Fire,” “Of the Moon,” “Of Time,” “Of Witches,” “OfDew,” “Of Nothing.” There is something of the title-thread reminiscent of what California poet Elizabeth Robinson has been working on for a while now, such as in her

Excursive

(New York NY: Roof Books, 2023) [see my review of such here] and

On Ghosts

(Solid Objects, 2013) [see my review of such here], to Anne Carson’s infamouscollection Short Talks (London ON: Brick Books, 1992), with each Carsonprose poem in the collection titled “Short talk on _____.” The title-structureallows for a kind of ongoingness, an umbrella under which anything might happenor occur, including threads that might relate to the specifics of each title.For Carpenter, she offers a measurement beyond immediate measurement, composinga sequence of lyric meditations on physical, intellectual and even outer spaceand celestial bodies. “2 August 1786 // I want to trouble you / in absence,”the sequence “Of a New Comet” begins, “with the following / imperfect account[.]”Whatis it about the weather? Lisa Robertson composed The Weather (VancouverBC: New Star Books, 2001) while living in England, another Canadian poet in theUK writing her own book-length lyric examination (a book Carpenter quotes atthe opening of this collection, also). “of magnifying and multiplying glasses,”Carpenter writes, to open the sequence “Of Glass,” “I have neither studied /norpracticed [.]” There is almost a way through which Carpenter utilizes Robertson’sThe Weather as a jumping-off point, providing a work that responds, inpart, to that classic title, but stretching that measure much further. Referencingtime, weather and space, this collection is a measure of measurement itself,seeing how expansive one can explore through the smallest examination, thesmallest measure. “what is the real temperature / of bodies of a differentnature / in similar circumstances,” she writes, as part of the extended “OfDew,” “of bodies a little elevated / and similar bodies / lying on the ground// sometimes bodies / having smooth surfaces / become colder in air [.]” In pinpointlyric, Carpenter offers a remarkable scaffolding that displays the whole shape,showcasing the ease in which she can articulate her finely-tuned lines, a movementof moments across conceptual space, time and motion. Or, as the sequence “OfTime” begins:

One hand holds the exhaustion.

Working. Away. In asuburb of Rome.

Between two televisions,blaring.

Three languages. Four deadlines.

A long waiting. No trains.

Will this flight cancel?

Feathers ruffle.

The arm aches to wing.

March 12, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Anna Veprinska

Anna Veprinska is the author of

Empathy in Contemporary Poetry after Crisis

. She was a finalist in the Ralph Gustafson Poetry Contest, has been shortlisted for the Austin Clarke Prize in Literary Excellence and received an Honourable Mention from the Memory Studies Association First Book Award. She is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Calgary.

Anna Veprinska is the author of

Empathy in Contemporary Poetry after Crisis

. She was a finalist in the Ralph Gustafson Poetry Contest, has been shortlisted for the Austin Clarke Prize in Literary Excellence and received an Honourable Mention from the Memory Studies Association First Book Award. She is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Calgary.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first collection of poems, Sew with Butterflies, was the realization of a dream. I was so young when it was published, and I knew nothing about publishing, except that a publisher (Steel Bananas) had heard me give a reading and asked if I had a collection I could submit. Their belief in me at that stage meant everything. The book that emerged held, at the heart of it, that moment of humility: that my poems had spoken to another human being. It was frightening and filling and fuelling.

Bonememory , my forthcoming second collection of poems, took a long time to write – or at least to arrive at writing. Although I published two chapbooks in between, Bonememory is set to appear about 10 years after my first collection. I needed that time to grow and believe in myself as a poet, and I think Bonememory represents that growth – it holds the poems I feel most proud of.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In another interview, I’ve written about how at seven years old I asked my father for a notebook and began writing poems. I can’t explain this in any other way, except to say that poetry came to me, not I to it. I wrote it before I understood what it was – I am still trying to understand what it is.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am a slow writer. Excruciatingly slow. In conversation with my creative writing students, I’ve been championing the slow writer, the non-prolific writer, the ‘I-just-moved-a-comma-today’ writer. But I’ve also been reminding them that writing takes place off the page as much as it does on the page – I am constantly thinking about and in poetry.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I think my writing fits into both of those descriptions. Bonememory began as individual poems whose patterns I later traced and pieced into a collection, as did Sew with Butterflies. But the new project I’m working on began with an idea for a collection, which each of the poems is moving toward.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Even after all these years of reading my poetry aloud, I still get nervous before and exhausted after readings. It’s a kind of exposure (in both uncomfortable senses of vulnerability and publicity). But I do enjoy readings, especially when they allow me to connect with others in the audience; I deeply appreciate conversations after a reading. To hear how a poem landed is a gift.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In Bonememory, the questions I am working with are about how memory is held in our bones and what that means personally, familialy, intergenerationally, collectively. While I was writing many of the poems in Bonememory, I was simultaneously working on a postdoctorate project that centred around listening to Holocaust testimonies. And I was also watching and reading about horrific world events, including Russia’s invasion of my home country of Ukraine, and, here in Canada, the findings of unmarked graves at former residential schools. These violences are part of the questions, too, as are my own limits as a viewer of these violences and the potentially nefarious tentacles of empathy.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Dionne Brand described Inventory, her 2006 long poem about the socio-political crises at the turn of this century, as an “antenna of the time.” In my own writing, I am often drawn to responding to the cultural and political moments we live in (when I can stomach writing about them, and that often takes time) and to ethics. But I don’t think that needs to be the role of the writer, especially if it doesn’t feel honest for that individual writer. I think it’s dangerous to prescribe a role for any artist.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I am so often a solitary writer, but I think working with an editor is a remarkable and imperative opportunity. My editor for Bonememory at the University of Calgary Press’s Brave and Brilliant Series, Helen Hajnoczky, was wonderful – attentive, honest, thoughtful. She offered care not only to each individual poem but also to the collection as a whole. It’s a gift to receive that kind of attention – it makes the work stronger. When I published my chapbook Stone Blossom with Anstruther Press, Jim Johnstone was likewise incredible, which I knew he would be from working with him as a mentor through Arc Poetry Magazine’s Writer-in-Residence mentorship program. Jim helped select the poems that became Stone Blossom and read each with a keen and honest eye. I am deeply indebted to the editors who have made my poems stronger.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I once heard a writer say, paraphrasing Lynda Barry, that one should touch the work every day. I like the spaciousness the word “touch” allows: you can shift a dash; you can move a word from one line to another. Touching the work keeps it close to you, keeps it breathing inside of you.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

My academic work means I am constantly moving between poetry and critical prose. I am at my best when I am merging the two. But, honestly, I think what I know best is how to write poetry, and I’ve learned to pass it off as prose.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Most of the time, I don’t have a routine so much as a commitment. In the “my (small press) writing day” essay I previously wrote for you some years back, I speak of my writing day as an attempt to reach for the magic of poetry. That commitment to reach for poetry can look like dedicated writing time, but it can also look like reading or watching a sunset. There are periods when I have more of a set writing routine, and there are periods when I come to writing when it calls me. I work at not being too hard on myself during the routine-light times, but I am happiest when I am writing.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Other words. The writing of other writers reminds me what can be done with language. Also, moving away from the project – allowing the time it needs to awaken again – is part of the writing: this can look like walking, reading, listening to music, staring out a window.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of my sweetheart.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of the above. A sound can lead to a poem. Or a smell. Or a brush stroke. Or science – I recently wrote a poem about a blue whale’s heart. I am especially enamoured of light, “a certain slant of light,” as Emily Dickinson wrote.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Oh, this is a huge question, because there are so many – poets and otherwise! Paul Celan has had an enormous influence on my writing – both my approach to language and my approach to the silences around and within language. Other writers that are indispensable for me include: Emily Dickinson, Anne Carson, Toni Morrison, Ilya Kaminsky, Ocean Vuong, Dionne Brand, Wisława Szymborska, Valzhyna Mort, Zadie Smith, and Rainer Maria Rilke.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d like to write more creative nonfiction and, perhaps someday, even fiction. But mostly I feel that I love poetry too much to stray far from it for long.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A professor, which I am fortunate to be, and which allows me to write and be inspired by the writing of my students. Alternatively, a psychologist: I am interested in the inner thoughts occupying (tormenting?) people’s minds, in what’s underneath the surface. I think a psychologist and a writer have this in common.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Was it Elie Wiesel who said one should only write if they could not live without writing? That’s why I write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recently read Elizabeth Rosner’s Third Ear: Reflections on the Art and Science of Listening, which was published last year. It’s a compassionate and thoughtful nonfiction book in which Rosner beautifully threads together personal narrative with science, art, and theory. I had the pleasure of listening to it as an audiobook read by Rosner.

I’ve been watching some wonderful world cinema. I particularly love Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love. It’s visually stunning, and there is so much power in what remains unsaid in this film.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am working on a new collection of poems through a Calgary Institute for the Humanities Fellowship: the poems are about the tension between my intolerance to noise (I have auditory sensitivity) and my reliance on sound (I often rely on auditory accommodations). It’s a collection that challenges me to work with and through sound.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

March 11, 2025

my Vancouver is as boundless as the sea : Vancouver, part one,

Youprobably caught that Christine and I recently headed west to read through Poetry in Canada at Simon Fraser University, thanks to the machinations ofStephen Collis and Isabella Wang. Do you remember when we read in Vancouverthrough Lunch Poems at SFU in February 2020, mere weeks prior to the Covid-era [see my report on such here],or our reading together last fall in Calgary [see my report on such here], or our paired reading andworkshop over in St. Catharines, Ontario (wishing I'd done a report on this, but time got away from me)? I’ve been enjoying the possibilitiesof our paired readings, the counterpoint between her work and mine providing aninteresting balance, I would think. As well, we so rarely get opportunities to run around and have adventures sans children (our St. Catharines trip didn't really allow for much in the way of adventuring, heading straight in to run workshop, read and return).

Youprobably caught that Christine and I recently headed west to read through Poetry in Canada at Simon Fraser University, thanks to the machinations ofStephen Collis and Isabella Wang. Do you remember when we read in Vancouverthrough Lunch Poems at SFU in February 2020, mere weeks prior to the Covid-era [see my report on such here],or our reading together last fall in Calgary [see my report on such here], or our paired reading andworkshop over in St. Catharines, Ontario (wishing I'd done a report on this, but time got away from me)? I’ve been enjoying the possibilitiesof our paired readings, the counterpoint between her work and mine providing aninteresting balance, I would think. As well, we so rarely get opportunities to run around and have adventures sans children (our St. Catharines trip didn't really allow for much in the way of adventuring, heading straight in to run workshop, read and return).We flew out of Ottawa on a delayed flight (oh, Air Canada) and made our hotel by 10pm or so (was that Ontario time or Vancouver time? I'll admit I've lost track), staying once more at the infamous Sylvia Hotel, and possibly even the same room we'd stayed in, prior (the fifth floor, overlooking the neighbouring building's skylight, and not the actual beach along English Bay). We caught the statues first thing, morning light across the water, and even saw a trio of swimmers emerge from the water. Is this February, still? Ten degrees, which means a nearly thirty degree difference between here and home. The grass is green, and the sun, warm on the skin.

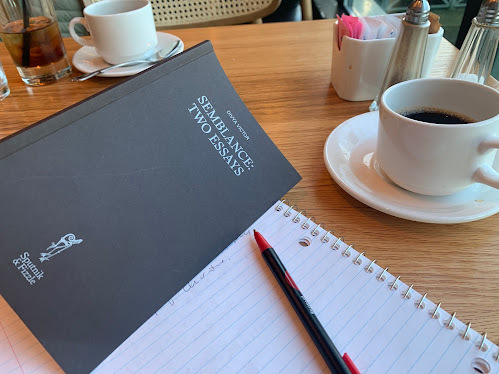

A photo by the same statues as our prior visit, then breakfast. After breakfast, I sat for a bit with coffee and a recent Divya Victor title, by Sputnik & Fizzle. And from there, we headed out to the Vancouver Art Gallery [Christine, with Jolanta Marcolla's 1975 "Kiss" in video loop behind her, as part of the exhibit

Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s

], which I'd only been attempting to visit across my last three stops in Vancouver (whether 2020, or when I read in Vancouver with Stephen Brockwell in 2017 [see my report on such here]; I can't even recall when I read in Vancouver prior to that; maybe 2004? that would be an awfully long time ago). It suggest it really might be twenty-five years since I've set foot here, perhaps.

A photo by the same statues as our prior visit, then breakfast. After breakfast, I sat for a bit with coffee and a recent Divya Victor title, by Sputnik & Fizzle. And from there, we headed out to the Vancouver Art Gallery [Christine, with Jolanta Marcolla's 1975 "Kiss" in video loop behind her, as part of the exhibit

Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s

], which I'd only been attempting to visit across my last three stops in Vancouver (whether 2020, or when I read in Vancouver with Stephen Brockwell in 2017 [see my report on such here]; I can't even recall when I read in Vancouver prior to that; maybe 2004? that would be an awfully long time ago). It suggest it really might be twenty-five years since I've set foot here, perhaps.

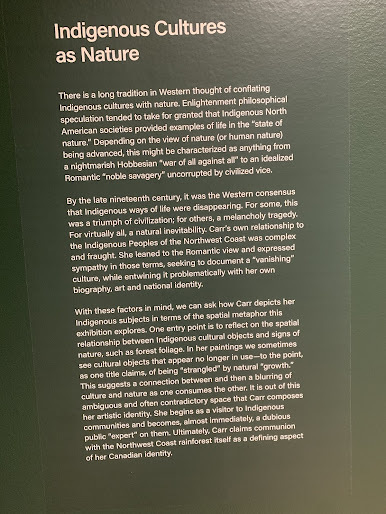

We made for the Emily Carr exhibit first, hitting the top floor and moving down, as the front desk recommended. I appreciated that various texts in the exhibit spoke directly to Carr's own misunderstandings and even appropriations of local indigenous markers, images and cultures, running wild with her own presumptions and blind-spots. It certainly made for a far more respectful understanding of Carr's work, and what Carr was responding to, actually acknowledging some of those conflicting contexts, Carr being very much a person of her time.

We made for the Emily Carr exhibit first, hitting the top floor and moving down, as the front desk recommended. I appreciated that various texts in the exhibit spoke directly to Carr's own misunderstandings and even appropriations of local indigenous markers, images and cultures, running wild with her own presumptions and blind-spots. It certainly made for a far more respectful understanding of Carr's work, and what Carr was responding to, actually acknowledging some of those conflicting contexts, Carr being very much a person of her time.