Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 20

April 9, 2025

Ongoing notes: early April, 2025 : Danny Jacobs + Caleb Jordan,

NationalPoetry Month! And you are following the daily poems I’m posting via the Chaudiere Books blog, yes? And you saw that Christine is doing a reading inOttawa on April 15th? We’re reading together in Ottawa in Junesomewhere (I’ll let you know where/when that happens) and she even reads inWinnipeg at some point, also. And the updates via my own substack and the new above/ground press substack? There’s so much happening! And the above/ground press postal increase sale, naturally, is still going on (in case you missedthat). Oh, and prepare yourself for the ottawa small press fair this June.

NationalPoetry Month! And you are following the daily poems I’m posting via the Chaudiere Books blog, yes? And you saw that Christine is doing a reading inOttawa on April 15th? We’re reading together in Ottawa in Junesomewhere (I’ll let you know where/when that happens) and she even reads inWinnipeg at some point, also. And the updates via my own substack and the new above/ground press substack? There’s so much happening! And the above/ground press postal increase sale, naturally, is still going on (in case you missedthat). Oh, and prepare yourself for the ottawa small press fair this June.Fredericton NB: Produced as “No. 2 in the Entrepôt Series”is Riverview, New Brunswick writer Danny Jacob’s Dreamland: The Bishop House Fragments (Fredericton NB: emergency flash mob press, 2024), following a poetrychapbook, Sulci (The Hardscrabble Press, 2023) and the full-length Sourcebook for Our Drawings: Essays and Remnants (Gordon Hill Press, 2019) [see my review of his full-length debut here] (with anovel forthcoming this year, according to his author biography). For those unaware,the Elizabeth Bishop House is one associated with the late PulitzerPrize-winning poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), now utilized as a space foroccasional residency [Christine and I drove by once, if you might recall]. As Jacob begins:

My first night here andthe Elizabeth Bishop House has kept me awake, the house or its ghosts, thecreak and gastric inner workings, the oil furnace revving up like the gaspingof the nearly drowned. I missed them, my wife and daughter. Sarah and I areseparating so the missing is pressurized, gravitational. There is no devastatingreason for the separation other than the sad fact of their being no devastatingreason.

Which some might argue makesit more devastating.

Thereis an echo, of sorts, to this work composed during a residency to the late Robert Kroetsch’s chapbook, Lines Written in the John Snow House (Calgary AB:housepress, 2002), later included in his trade collection, The SnowbirdPoems (Edmonton AB: University of Alberta Press, 2004) [see my note on such here], composed while Kroetsch was in Calgary as part of the University ofCalgary’s Markin-Flanagan Distinguished Writers Programme. Unlike Kroetsch,Jacobs writes his as a journal of first-person fragments, observations andclarifications, working his way through the ghosts of that particular space,and of Bishop’s own writing, all through the lens of this imminent separation. Heoffers: “To write is to abandon surety.” He writes in this unknown space into,one might say, the unknown of what is to come, suggesting this work as a kindof pivot, a placelessness between where he was prior, to where he will be oncehe emerges. The uncertainty runs through this whole work, set as a foundationupon which the narrative fragments build.

I imagine Bishopwandering this house now, a vexed Crusoe brought back to her homeland, pickingat what was kept, what was bought for old-timey ambiance. She pages through thegiant family bible atop the upright piano with the clawfoot stool, presses akey on the Underwood – that familiar, mechanized resistance. She opens the reddrawstring bag in which she used to smuggle roast beef on flights from Bostonto Nova Scotia, now locked away behind a glass hutch, and asks – like Crusoeasks about his own stranded artefacts – “How can anyone wants such things?”

Rock Island IL/OK: I’m moving throughOklahoma poet Caleb Jordan’s Idylls (Rock Island IL: Stone Corpse Press,2025), a sequence set as two sequences of fourteen numbered sonnets,reminiscent, slightly, of Stephen Brockwell and Peter Norman's magnificentcollaborative essay in sonnet form, Wild Clover Honey and The Beehive, 28Sonnets on the Sonnet (Ottawa ON: The Rideau Review Press, 2004), acollection I’d love to be able to see back in print. The sonnet is, asBrockwell himself has noted, an endlessly mutable form, and wild experimentsaround the sonnet have appeared for decades, with space enough for far morethan what has already been produced.

I’mintrigued by Jordan’s sonnet-shapes, clearly feeling out the form throughoutthe entire paired sequence: “I emerge from the hollow horse corpse / into adesert in a box / and I cannot find the actual / door,” he writes, to open poem“XIII” in the first sequence, “even though / it is right there in front of me.”

Thisis a big project for what suggests itself as a debut, twenty-eight sonnets froma writer who offers little in his bio beyond the fact of his “PhD in CreativeWriting from Oklahoma State University,” and that he “spends his free time asall Oklahomas do (searching for evidence of the existence of Bigfoot and other “cryptids”).”The internet doesn’t provide much more, but there is a curious interview withJordan over at Black Stone/White Stone that provides this intriguingquote: “I do not want to be enjoyed but to be fleetingly experienced, like animmunization, and sting a day or two later.”

XIV

I am not reaching. In my mind

is a door and behind thatdoor

is a name. Thucydides?

Pantagruel? Joe? The keyto

the door is glowing blue

underneath unbreakableglass.

I claw, I curse, I dream

of opening the door andfinally

saying the name aloud.

It hurts to brush freshlycut

grass with the tenderpalm

of my hand. The shapes

on my journal movethemselves.

Unbidden, the door creaksopen. (“1”)

April 8, 2025

Allyson Paty, Jalousie

at the center of thebridge

high ridge and contour

of the land

past the banks

my father

without fail:

imagine sailing onto this

Lenape hills

1609, Henry Hudson

on the Halve Maen

vision opens

out, out

then Manhattan

the car subsumed

a knife of sky

no horizon (“In MediasRes”)

Winnerof The Berkshire Prize for Poetry, as judged by Diana Khoi Nguyen, is New York poet Allyson Paty’s full-length debut, Jalousie (North Adams MA: TupeloPress, 2025). Having been aware of the strength and clarity of her work forsome time (having produced a chapbook by her through above/ground press, after all), I’m a bit startled to be reminded that this is Paty’s debut, a collectionof moments that lean into and against each other, facing out in multipledirections. “One renders what is happening / moves to say what has been,” shewrites, to close the opening poem, “Along the Grain,” “A tenderness to walk thefault lines / and slip oneself in [.]” Paty’s lyrics are dense, precise and thoughtful,offering short moments around the present moment that accumulate and meanderwith deep and tender purpose. As judge Diana Khoi Nguyen offers, as part of hercitation:

The title of thisstunning collection refers to a window treatment which has rows of angledslats, like blinds or shutters, and Allyson Paty’s disarming lyric exemplifiesa deliciously sharp perspective which at times ranges from being seen literallythrough partially-opened slats, the world at a slant, to confronting themediations of how we tender our communications, representations of self, labor,and love. These are poems reminiscent of the cutting lines of Elaine Kahn andElisa Gabbert, but these poems are uniquely their own.

There’san element of the English-language ghazal to Paty’s lyrics, offering a leap betweenlines, between thoughts, as poems form out of what the individual points andperipherally-connected moments shape into, once you step back a bit. There’s suchcare to her lines, and a kind of casual flow, deep-set and intertextual andprecise, with ever an eye on destination, even as she focuses on each momentacross each journey. “In a patchy field / a man kneels down // pours water /from one vessel to another,” she writes, to close the poem “Decade,” “Grassestrail their fingers / an alphabet works through you // You draw a straight line[.]” Her poems are smart, and observational, wise and tender. I’m struck, aswell, by the mantra-moments of an extended sequence such as “Premise,” eachpoem, each page, each line, beginning with the same word, offering anaccumulation of seventeen pages, seventeen points, across a wide expanse:

Having returned to mydesk

Having typed weddingdance into the browser

Having encountered afield of photographs showing white people in formal

dress move over lustrousfloors

Having realized mymistake

Having added bruegel

April 7, 2025

Touch the Donkey : new interviews with J-T Kelly, Jennifer Firestone, Austin Miles + Alice Burdick,

Anticipating the release next week of the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the forty-fourth issue: J-T Kelly, Jennifer Firestone, Austin Miles and Alice Burdick.

Anticipating the release next week of the forty-fifth issue of Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal], why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the forty-fourth issue: J-T Kelly, Jennifer Firestone, Austin Miles and Alice Burdick.Interviews with contributors to the first forty-three issues (more than two hundred and seventy-four interviews to date) remain online, including: Henry Gould, Leesa Dean, Tom Jenks, Sandra Doller, Scott Inniss, John Levy, Taylor Brown, Grant Wilkins, Lori Anderson Moseman, russell carisse, Ariana Nadia Nash, Wanda Praamsma, Michael Harman, Terri Witek, Laynie Browne, Noah Berlatsky, Robyn Schelenz, Andy Weaver, Dessa Bayrock, Anselm Berrigan, Alana Solin, Michael Betancourt, Monty Reid, Heather Cadsby, R Kolewe, Samuel Amadon, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Miranda Mellis, kevin mcpherson eckhoff and Kimberley Dyck, Junie Désil, Micah Ballard, Devon Rae, Barbara Tomash, Ben Meyerson, Pam Brown, Shane Kowalski, Kathy Lou Schultz, Hilary Clark, Ted Byrne, Garrett Caples, Brenda Coultas, Sheila Murphy, Chris Turnbull and Elee Kraljii Gardiner, Stuart Ross, Leah Sandals, Tamara Best, Nathan Austin, Jade Wallace, Monica Mody, Barry McKinnon, Katie Naughton, Cecilia Stuart, Benjamin Niespodziany, Jérôme Melançon, Margo LaPierre, Sarah Pinder, Genevieve Kaplan, Maw Shein Win, Carrie Hunter, Lillian Nećakov, Nate Logan, Hugh Thomas, Emily Brandt, David Buuck, Jessi MacEachern, Sue Bracken, Melissa Eleftherion, Valerie Witte, Brandon Brown, Yoyo Comay, Stephen Brockwell, Jack Jung, Amanda Auerbach, IAN MARTIN, Paige Carabello, Emma Tilley, Dana Teen Lomax, Cat Tyc, Michael Turner, Sarah Alcaide-Escue, Colby Clair Stolson, Tom Prime, Bill Carty, Christina Vega-Westhoff, Robert Hogg, Simina Banu, MLA Chernoff, Geoffrey Olsen, Douglas Barbour, Hamish Ballantyne, JoAnna Novak, Allyson Paty, Lisa Fishman, Kate Feld, Isabel Sobral Campos, Jay MillAr, Lisa Samuels, Prathna Lor, George Bowering, natalie hanna, Jill Magi, Amelia Does, Orchid Tierney, katie o’brien, Lily Brown, Tessa Bolsover, émilie kneifel, Hasan Namir, Khashayar Mohammadi, Naomi Cohn, Tom Snarsky, Guy Birchard, Mark Cunningham, Lydia Unsworth, Zane Koss, Nicole Raziya Fong, Ben Robinson, Asher Ghaffar, Clara Daneri, Ava Hofmann, Robert R. Thurman, Alyse Knorr, Denise Newman, Shelly Harder, Franco Cortese, Dale Tracy, Biswamit Dwibedy, Emily Izsak, Aja Couchois Duncan, José Felipe Alvergue, Conyer Clayton, Roxanna Bennett, Julia Drescher, Michael Cavuto, Michael Sikkema, Bronwen Tate, Emilia Nielsen, Hailey Higdon, Trish Salah, Adam Strauss, Katy Lederer, Taryn Hubbard, Michael Boughn, David Dowker, Marie Larson, Lauren Haldeman, Kate Siklosi, robert majzels, Michael Robins, Rae Armantrout, Stephanie Strickland, Ken Hunt, Rob Manery, Ryan Eckes, Stephen Cain, Dani Spinosa, Samuel Ace, Howie Good, Rusty Morrison, Allison Cardon, Jon Boisvert, Laura Theobald, Suzanne Wise, Sean Braune, Dale Smith, Valerie Coulton, Phil Hall, Sarah MacDonell, Janet Kaplan, Kyle Flemmer, Julia Polyck-O’Neill, A.M. O’Malley, Catriona Strang, Anthony Etherin, Claire Lacey, Sacha Archer, Michael e. Casteels, Harold Abramowitz, Cindy Savett, Tessy Ward, Christine Stewart, David James Miller, Jonathan Ball, Cody-Rose Clevidence, mwpm, Andrew McEwan, Brynne Rebele-Henry, Joseph Mosconi, Douglas Barbour and Sheila Murphy, Oliver Cusimano, Sue Landers, Marthe Reed, Colin Smith, Nathaniel G. Moore, David Buuck, Kate Greenstreet, Kate Hargreaves, Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Erín Moure, Sarah Swan, Buck Downs, Kemeny Babineau, Ryan Murphy, Norma Cole, Lea Graham, kevin mcpherson eckhoff, Oana Avasilichioaei, Meredith Quartermain, Amanda Earl, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims, Stephen Collis, Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming forty-fifth issue features new writing by: Dag T. Straumsvåg, brandy ryan, Misha Solomon, D. A. Lockhart, Lea Graham, Jordan Davis + Larkin Maureen Higgins.

And of course, copies of the first forty-three issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe?

Included, as well, as part of the above/ground press annual subscription! Which you should get right now for 2025! Our thirty-second year! and the above/ground press postal increase sale, which is happening right now!

We even have our own Facebook group, and a growing (new) above/ground press substack . It’s remarkably easy.

April 6, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jane Shi

Jane Shi [photo credit: Joy Gyamfi] is apoet, writer, and organizer living on the occupied, stolen, and uncededterritories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), andsəlil̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples. Her debutpoetry collection is echolalia echolalia (Brick Books, 2024). She wants to livein a world where love is not a limited resource, land is not mined, hearts arenot filched, and bodies are not violated.

1 - How didyour first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I wrote andpublished my chapbook Leaving Chang’e on Read (Rahila’s Ghost Press,2022) and then my full-length collection echolalia echolalia (BrickBooks, 2024) during the pandemic, so the idea of poetry ‘changing my life’makes me laugh. I’m mostly stunned that people want to read my work. And I’malso surprised that no one is voraciously tearing it apart the way I sometimes imaginepeople doing in my head. Which is to say I think seeing people’s kindness andappreciation for poetry and creativity is heartening in an otherwisedisillusioning world.

For me, from ayoung age, poetry was a source of escape, coded wordplay to dissociate into andhide behind. I’m learning to lean into poetry’s relationality, sociality, andsense of responsibility more as I write more seriously and expansively.

I would say echolaliaecholalia sprouted from Leaving Chang’e on Read in an organic way.Many poems from the latter are in the former. I had a really great experience workingwith Mallory Tater and Brandi Bird at Rahila’s Ghost Press; their insights intomy poems helped me prepare for my full-length for sure.

I enjoyed thespace a full-length collection offers. The other month at my book launch, oneof my first readers, poet Beni Xiao, reminded me that my first drafts of echolaliaecholalia was significantly longer. My editor at Brick Books, Phoebe Wang,helped me cut things down. She said that she’s more of a minimalist compared tome, and that was intriguing. I have a hoarding issue that I didn’t know aboutuntil a loved one pointed it out. So, I think that shows up in my poetry. Ilearned a lot about myself through writing both the chapbook and full-length: Iguess that’s probably what changed my life the most, the internal change. Ingeneral, I feel relieved that my work is out in the world, less fearful, andmore excited to be in conversation with other poets I admire.

echolaliaecholalia goes deeperinto things, perhaps, and talks more explicitly about the exploitation of marginalizedartists, filicide of disabled children, wanting to leave this world but stayingbecause you haven’t watched that episode of Arthur yet. I enjoyed beingable to play with multitudinous forms.

I’m especiallythankful that my book was able to help raise funds for different Gazan mutualaid projects via Workshops4Gaza’s bookstore at Open Books: A Poem Emporium inSeattle. Billie of Open Books—a bookstore that is poetry-only—invited me downto sign copies and it was a wonderful experience. Every person who entered thespace was a poet, which was the coolest.

2 - How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I have beenwriting poetry for most of my life, since I was eight, so it made sense to workon poetry more seriously as a first full-length book project. When I graduatedfrom university in 2018 the first thing, I said to myself was, “I get to writepoetry!! I get to write poetry!!” I remember the exact location in my formerplace living situation where I said this, too.

I write essaysand non-fiction outside of poetry, but I felt like the things I most wanted towrite about over the last few years only poetry can handle. For example, I havewritten about the abandonment of autistic children and reshaping language in myessay “Rewriting the Autistic Mother Tongue.” But you can use line breaks andmetre and white space on the page to convey what experiencing violence from ayoung age feels like, and what that does to the imagination. For me, poetry isabout learning to be itself, so the subject matter and the form naturallygravitate towards each other.

3 - How longdoes it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write all thetime but the act of deciding that something is a project takes a bit moreintentional effort. What I learned most out of writing a first full-lengthcollection is that you don’t realize what you’re doing until you’re almostfinished, but taking a stab at things as if you do helps you along thatprocess.

I don’t takenotes unless I’m writing longer-form essays, but I copy-paste earlier draftssomewhere else, maybe the bottom of the page or in my notes app, possibly to belost forever. Sometimes reading poems in front of an audience helps me figureout what I need to work on, and I follow what I feel in my body as well. Thereare a lot of things I edit out because I didn’t enjoy how reading it made mefeel. Or I notice an audience member takes to a particular line, so I highlightthat in another draft. It feels very collaborative that way. And of course, ifyou’re not completely forgetful like I am sometimes, you acknowledge theirinsights and influence in your work. That’s probably why my acknowledgementsection is a bajillion pages long. And I’m almost afraid to look at it for fearthat I’ve forgotten to mention someone…

Mynot-note-taking tendencies is a bit frustrating because it makes it hard toreturn to drafts to figure out what I was thinking. But then it’s like, I’mcreating a palimpsest with another draft, and you can see faint outlines of theearlier one. Because between the moment you wrote the first draft and the next,your perspective has changed.

4 - Where doesa poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I’m only morerecently thinking about things in terms books. But at heart I think in terms ofa collection of images and feelings, of dreams. I want those things shaped andmade concrete and alive and sometimes that’s a poem and other times it’s abook. Other times it’s an essay or a meme or a doodle.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I really enjoythem! A few months ago I took the time to work with spoken word poet Kay Kassirer to practice performing more. I appreciated that a lot as, in part, thepandemic has limited opportunities to read in public, and I felt out ofpractice. I like telling jokes between my poems and making people laugh. Readingscan be public spiritual acts and acts calling for rebellion and change.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

I’ve talked a lotabout this with my friend shō yamagushiku. I noticed, when I was reading hisbook shima, that a lot of the collection takes place outside, whereas alot of my book takes place inside. It feels like the questions my poems areconcerned with are related to what happens behind closed doors, what getshidden in plain sight. I tend to write about the bigger, external things inessays. The mundane, household things that appear in my work make me think thatmy poems are listening for the secrets of everyday objects and what theyeavesdrop and collect along the way. So maybe, on some psychic level, my poemsare concerned with what everyday things can teach us about ourselves.

Intimacy withinterior spaces is also a gendered, disabled experience. So, animating disabledqueer interiority feels like a huge concern in my work, one that hopefullyreminds us that the revolution starts at home (as the book about intimateviolence within activist communities suggests) and that we sometimes need toteach ourselves (or reparent ourselves) how to do it.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

A few words thatcome to mind are noticing, tending, interjecting, remembering, and dreaming.Writers are assassinated for telling the truth about the state of the world.They often play the role of ringing an alarm and dousing cold water on us whenit’s needed. Writers can be dangerous to empire, or they can choose to serveit.

A few months ago,I learned from WAWOG Toronto that of all the arrests for protesting genocide inthis country, literary events have had the most proportionately speaking. So, Ithink writers around me, those I want to align myself with, are doing the workof redefining what writing ought to do. That’s seen as dangerous by the powersthat be.

If nothing else Ithink writers ought to write to free themselves or imagine a way to do so, andto consider who else they’re freeing in their work. June Jordan says itbeautifully: “Good poems can interdict a suicide, rescue a love affair, andbuild a revolution in which speaking and listening to somebody becomes thefirst and last purpose to every social encounter.”

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

I really enjoyworking with an editor. I enjoy disagreeing with someone and knowing why andknowing why something lands in a different way than I intended. Editors alsohelp you recognize the things you’re doing and how they are or aren’t alignedwith your vision.

The thing I enjoythe most (while also finding it terrifying) is to be read intimately. Forexample, earlier on in the editorial process, Phoebe pointed out the speaker inmy poems have had a hard life. I was very confused when I heard her say it: Don’tmost people have a hard life? Why would I write poetry if I had an easy one? Butthat comment prompted me to put a line about having a hard life in my poem“Catalogues of Tearing.” Others reflecting what you’re doing is crucial to thewriting process.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Wayde Comptonsays that your writing is often wiser than yourself. I think that helps me letgo of control and needing to understand what I’m doing all the time.

10 - What kindof writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I start my day bytopping up eSims. They’re electronic sim cards we’ve been sending to people inGaza since December through the Crips for eSims for Gaza project that I beganwith Alice Wong and Leah Lakshmi-Piepzna Samarasinha. I feel uneasy having awriting routine when there are multiple ongoing genocides and crises impactingpeople around the world, including locally. But I write all the time anyway.It’s just that right now, my routine looks a little different, and I pour moreof my time into these organizing projects and write towards them.

For example, inmy essay, “When the Poem is a Spreadsheet: Joining Us in #ConnectingGaza,” Iweave doing this organizing work with thinking through the role of poetry andthe role of writers in the world. Weaving disparate parts together is a poet’swork, and it’s also the work of engineers, and I found it moving to think aboutthe role of engineers and poets in tandem. I had intended to complete thisessay months earlier. But for better or for worse, I hadn’t really processedwhat we were doing fully and needed time to prepare logistics. I felt theresponsibility and inadequacy of weaving my experiences into urgent mutual aidwork of thousands of people and their families. I also, in the process, taughtmyself how to write an instruction manual and likely have way more to learn.That’s a totally different genre than poetry!

I often writelater in the day, usually at night, when things are quieter, when my brain isoveractive. I also write down my dreams first thing in the morning.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

I wouldn’t say mywriting is ever stalled but would say there are times when my heart, body,mind, and spirit aren’t aligned or speaking to one another. Or because of life,trauma, hardships, they don’t feel settled or still enough to focus on writing.

Sometimes when Iread earlier drafts, I see that I was processing lots of anger and resentmentand shame that I didn’t know I was feeling. Those drafts are still importantbecause they teach me something about what I was feeling at the time. On thecontrary to ‘writer’s block,’ I struggle with wanting to share every thought Ihave with the world; I think that’s partly because I grew up with the Internet.In a lot of ways, a writing practice is more about creating a filter for myblabbermouth-brain, scaffolding my voice with intention.

When I struggleto read, I often turn to film or music. I write Letterboxed reviews of nearlyevery film I see.

12 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Sesame oil.

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

In echolaliaecholalia, I bring in , the film Arrival, the bandsI used to listen to as a teenager (that, apparently, teenagers still listento!), Twitter polls, Matthew Wong paintings, cartoons, video games, and TikTokvideos. As Rebecca Salazar suggests in their blurb of echolalia echolalia,the poems are chronically online. The Internet is a place that my work inhabitsintimately. Existing on the Internet as a preteen in the early 2000s is aspecific experience that feels important to document.

14 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I was deeplyinfluenced by reading José Saramago growing up and likely wouldn’t have becomea more experimental poet with an eye for satire were not for reading Vladimir Nabokov and Chuck Palahniuk in those years as well. In the last few years: TheresaHak Kyung Cha’s Dictee; Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries; thewritings of Kai Cheng Thom, Cyrée Jarelle Johnson, Jody Chan, Beni Xiao, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Alice Wong, Lucia Lorenzi, bell hooks, Rita Wong,Mercedes Eng, Christina Sharpe, and Dionne Brand, etc. These days I’m alsoreading Octavia E. Butler, Wendy Trevino, June Jordan, and Rasha Abdulhadi.

15 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

So many things! Iwant to try writing short stories and speculative fiction. One day I’ll try myhand at a film.

16 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wanted to be atherapist as a younger person but realized, after working briefly in socialservices, that I couldn’t stomach the exploitative landscape of psychologicaland psychiatric institutions.

I suspect I couldhave gone into film-editing or visual arts.

17 - What madeyou write, as opposed to doing something else?

As silly as it sounds,I’m not a painter because it’s expensive to get your own studio and I’m notgreat at cleaning up a physical mess. I’m also a touch sensitive to scent. Thetech aspect of filmmaking also feels daunting in a way that opening a Word docisn’t. Writing, on its own, feels like I can do anywhere and anytime. Writingis painting with words, cinematography with language.

18 - What wasthe last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I recentlyfinished reading The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin. Reading about LeGuin talk about her opposition to the Vietnam War… this novel feels like itcould have been written today.

TokyoGodfathers is a gorgeousportrait of family and the interconnectedness of neighbours. One of the bestChristmas films.

19 - What areyou currently working on?

I’ve beenthinking about what it takes to not just observe and witness injustice butconfront power and end systems of domination. What makes it possible for peopleto fight back collectively? What problems do we inherit from our ancestors inthat work and what problems do we replicate in our attempts at liberatoryaction? How can we build towards liberatory futures? I’m working on differentways to write about that and think through those questions.

April 5, 2025

Juliana Spahr, Ars Poeticas

my review of Juliana Spahr's Ars Poeticas (Wesleyan University Press, 2025) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

my review of Juliana Spahr's Ars Poeticas (Wesleyan University Press, 2025) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

April 4, 2025

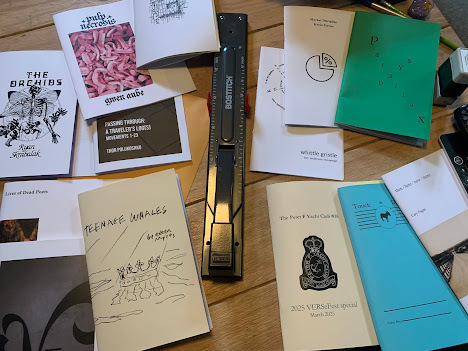

new from above/ground press: Doller, Myles, Crosby, Davies, Moseman, Polukoshko, Unsworth + The Peter F Yacht Club, VERSeFest 2025 special,

Sandra Doller, I’ll try this hour $5 ; Eileen Myles, Teenage Whales $5 ; Gregory Crosby, Parallax Days: poems ; Kevin Davies, Market Discipline $5 ; Lori Anderson Moseman, whittle gristle $5 ; Thor Polukoshko, Passing Through: A Traveler’s Log(s): Movements 1-23 $5 ; Lydia Unsworth, GAG $5 ; The Peter F Yacht Club #35: 2025 VERSeFest Special $6 ;

Sandra Doller, I’ll try this hour $5 ; Eileen Myles, Teenage Whales $5 ; Gregory Crosby, Parallax Days: poems ; Kevin Davies, Market Discipline $5 ; Lori Anderson Moseman, whittle gristle $5 ; Thor Polukoshko, Passing Through: A Traveler’s Log(s): Movements 1-23 $5 ; Lydia Unsworth, GAG $5 ; The Peter F Yacht Club #35: 2025 VERSeFest Special $6 ; published in Ottawa by above/ground press

March 2025

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $2 for postage; in US, add $3; outside North America, add $7) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). See the prior list of recent titles here, scroll down here to see a further list of various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; and you know that 2025 subscriptions (our thirty-second year!) are still available, yes? AND THE ABOVE/GROUND PRESS POSTAL INCREASE SALE CONTINUES UNTIL JULY 9, 2025! oh, and you know above/ground press has a substack now? sign up for announcements, and even new features!

With forthcoming chapbooks by: J-T Kelly, R. Kelowe, Tom Jenks, Mandy Sandhu, Jon Cone, Yaxkin Melchy (trans. by Ryan Greene, Mrityunjay Mohan, Laynie Browne, Meredith Quartermain, Nada Gordon, Andrew Brenza, Brook Houglum, Orchid Tierney, Noah Berlatsky, Terri Witek, David Phillips and probably others! (yes: others,

April 3, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Melora Wolff

Melora Wolff’s

workhas appeared in publications such as Brick,the New York Times, the Normal School Best American Fantasy, SpeculativeNonfiction, the Southern Review, and EveryFather’s Daughter: 24 Women Writers Remember Their Fathers. Her work hasreceived multiple Notable Essay of the Year citations from Best American Essays and SpecialMentions in Nonfiction in the Pushcart Prizes. She is director creativewriting at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Melora Wolff’s

workhas appeared in publications such as Brick,the New York Times, the Normal School Best American Fantasy, SpeculativeNonfiction, the Southern Review, and EveryFather’s Daughter: 24 Women Writers Remember Their Fathers. Her work hasreceived multiple Notable Essay of the Year citations from Best American Essays and SpecialMentions in Nonfiction in the Pushcart Prizes. She is director creativewriting at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My newbook Bequeath is a memoir in essays,a collection of personal pieces I’ve published over many years. So, there are variations in theessays’ styles and forms, but together, they tell a sustained story about myfamily’s past and about the vanished city of Manhattan in the 1970s, my coming-of-ageyears. The book explores family bequests of myths and artifacts that get passedalong from one generation to another. People die, leave ideas, objects, and footprintsbehind in the snow or sand, and all those ghost-prints mean something—but what?The narrator—the persona of me, at various points—uses both imagination andmemory to sort it all out. In essays, I’m always reckoning with the effects ofmemory and imagination in truth-telling. My previous short book, The Parting, published by the now shutteredShires Press, is a collection of published prose poems, a similar bookthematically, but with many more dreamscapes and fantasies. And both booksdepict moments of transformation, when realities start to morph into somethingelse, something “other.” I love how certain styles can deliver solid facts inways that feel mysterious, eccentric, even magical, so I hope that the bookshave that approach in common.

How did you come tonon-fiction first, as opposed to, say, fiction or poetry?

When Ifirst started writing seriously, I was a university sophomore enrolled inFiction workshops, led by the late poetic postmodern novelist John Hawkes. Histeaching was an intense, festive inspiration for a lot of young writers. Thanksto his mentoring, I continued as a fiction writer, and yet I also loved andwrote first-person narratives, and my short stories always leaned obviously—yearningly,really-- toward personal writing, memoirish tales. I discovered my personalessays by writing autofiction in graduate school. Now my essays—all of them factual—douse some techniques of fiction. People have told me that reading Bequeath feels like reading essays andshort stories simultaneously. I’m glad the book lives in some happy maritalspace between fiction and nonfiction. And two great poets also influenced medeeply as teachers and as writers, Agha Shahid Ali and Galway Kinnell. Mybiggest love is language, really, not genre, so I continue to write and readfiction, nonfiction, poetry, prose poems, hybrid works.

How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takesme a long time to commit myself to an idea, but when I do, work comes veryquickly. Suddenly I’ll just see a pattern or a connection that makes an essaycomplete in my mind and I usually draft a full essay in one sitting, re-writingsentences as I go. Then I work the sentences over and over obsessively, so thattakes a while!

Where does a work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

For me, writingoften begins with a sudden image or with a connection that happens in my headin a nearly audible flash. And then I have to start writing. The title essay ofBequeath, for instance, came to mesuddenly at an exhibit in El Museo del Barrio in New York while I was lookingat the artworks of Raphael Montaňez Ortiz. I saw the shape of the whole essay,for some reason. It’s an alchemy that can happen when you look at fascinating artsometimes—images beget more images. Another essay came to me entirely on a trainin the instant a certain stranger passed by me in the aisle and I drafted thewhole thing before the train arrived at the destination. Of course, some piecestake much longer, even years, like the essay “Fall of the Winter Palace,” whichwent through many versions. Gradually,work accumulates into a book with one voice.

Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

Yes, Ienjoy giving and attending readings. I like seeing everyone all out togetherfor a word concert. Story-telling, poetry—it’s all born of oral traditions, soreadings continue that history.

Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’tsit down to write with any theoretical concerns in mind, but I discoverconcerns while I write. Many of my essays explore power struggles between menand women, the legacies of expected gender roles, different forms of violenceand vulnerability. I’m always exploring the implications of truth, lies, and memoryin inherited stories. I’m interested by all those intimate, urgent questions thatkeep you up at night, especially, what’sgoing to happen next? Hidden questions that you hear in the dark are reallyuseful because it’s the intimate, unanswerable ones that make you want to keepreading and revising your own inscrutable life, learning its story a littlebetter by letting it burn on the pages, even if it hurts, which it often does.

Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential.Editors can talk you through an idea and a paragraph, they can see a biggerpicture very well and reflect it back. Goodeditors feel the rhythm and heart of a sentence and a story and a sensibility,and can help writers to feel them more completely too. Good editors know how to stir the waters for dislodgingeven deeper, clearer words. Most writers have very rude inner-editors—sometimesthey’re too harsh, or too lazy, or too noisy—and professional editors canintervene in the scuffles that sometimes break out between a writer and theirinner-editor.

What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

At thispoint—and I’m hoping to have another couple of decades to decide—three thingscome to mind. Never say ‘I told you so.’ Shake off despair. Love your ownspace.

What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

My daysbegin with coffee and a drive to my office on the college campus where I teach.I don’t keep a daily writing routine, and I admire those that do. I write when I can and keep notebooks on handall the time for ideas that come to me during the busy days. Sometimes my creativeself really wants all my attention at an impossible moment, and notes are oneway I can notice thoughts that become essays later on. For me, there’s usually atleast one long walk in the woods—preferably through snow drifts--literally, beforeI write a final draft.

When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I re-readmy favorite authors, re-read their language, some in translation, that I know thrillsme—like the prose of Polish author Bruno Schulz. Just reading a paragraph or afew sentences by Schulz in his collections Cinnamon Shops and Sanatorium Under the Sign of The Hourglass, his ecstatic flights of mythic imagination, and I knowI’m back in touch with the physical, swooning feeling of a meaningful relationshipwith language. I need to push myself to fall back in love with words. Andwalking through an art gallery, seeing thefabulous ways that visual artists speak through images can get creative energymoving again too, light some spark.

What was your lastHallowe'en costume?

I think Iwas a mouse with big furry ears. Or maybe I was a Frosted Flakes Cereal box. AndI was a child, I should add. In actuality, not in costume.

If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I hadn’tbecome a writer, I would have been a singer. I grew up in a family of musiciansand singers, and music was usually playing or being played--Broadway scores,jazz, Gilbert and Sullivan, cabaret tunes, pop and folk hits. There’s been an operasinger in my family, and a sax player, and two light opera singers, and twopianists. Someone was always in rehearsal or dashing for a show or a gig or a concertor a lesson. Growing up, I loved listening to Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone,Judy Garland, Blossom Dearie--all those fantastic female voices. Singing isemotional and physical, a full body workout in a way that writing—in myexperience—isn’t, so I hope singing is my life and career in the multi-verse.

What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

Words arenatural companions and I love them all for it.

What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve reada lot of wonderful books in the past months—The Empusium, by Olga Tokarczuk, TheThird Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, Michael Ondaatje’s new poetry volume, A Year of Last Things, Carol Mavor’s book of essays about objectsand art, Serendipity. I finally read The Invention of Morel by Alfred Bioy Casares and was amazed by its imaginative structure and pathos. I think EdwardBerger’s 2022 version of All Quiet on theWestern Front is a great film.

What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

Swim witha dolphin. Play fiddle in an Irish pub. See the stained-glass windows of NotreDame. Hug a collie puppy. Sip champagne in a Prague café. Meet Edgar Allan Poeand have a long chat with him about hypnagogic visions. Learn how to throw apot, blow glass, play the cello, speak Gaelic, sing harmony without effort,grow roses, climb an apple tree, waltz with someone who really knows how towaltz, live near a country church, see the Northern Lights from a fjord, andgrow old happily.

April 2, 2025

Imani Elizabeth Jackson, FLAG

And what of flags? Irefuse the immediate meaning. I wrestle the word down to the ground and findlife seeping up. Wild iris, march herb calamus, fabric signal, the tail of somedogs, the tail of some deer, something rippling or wagging, object for attraction,stone suitable for pavement, to lay such stones, they say it’s for allegiance,my aunt thinks skin, I’m looking to a porous and fluid border, where theboundary cracks and green pours through, herb to mouth, to quilt to stone,water tucking into the bends, all this motion fills in! to flag or hang loose,to tire, decline, to hail, raise a concern, lost steadiness, oh love, greeningearth, to mark for remembrance and return.

Thefirst full-length collection by American poet Imani Elizabeth Jackson,following the chapbooks

Context for arboreal exchanges

(Belladonna*,2023) and saltsitting (g l o s s, 2020) as well as the co-authored (asmouthfeel)

Consider the tongue

with S*an D. Henry-Smith (Paper Machine,2019), is FLAG (Brooklyn NY: Futurepoem, 2024), a striking collection ofprose lyric that writes on boundaries, borders and history, elements that reada bit more charged during the current geopolitical climate. “Sometimes thereare no words or / the words simply are not the right / ones.” she writes, aspart of the opening section. “Or sometimes the words don’t / match, or they jumble.It’s okay, it’s / alright, it’s all flow. Flow, flow, flow.”

Thefirst full-length collection by American poet Imani Elizabeth Jackson,following the chapbooks

Context for arboreal exchanges

(Belladonna*,2023) and saltsitting (g l o s s, 2020) as well as the co-authored (asmouthfeel)

Consider the tongue

with S*an D. Henry-Smith (Paper Machine,2019), is FLAG (Brooklyn NY: Futurepoem, 2024), a striking collection ofprose lyric that writes on boundaries, borders and history, elements that reada bit more charged during the current geopolitical climate. “Sometimes thereare no words or / the words simply are not the right / ones.” she writes, aspart of the opening section. “Or sometimes the words don’t / match, or they jumble.It’s okay, it’s / alright, it’s all flow. Flow, flow, flow.” Setin six sections—“Untitled,” “Land mouth,” “The Black Bettys,” “One wild blueday,” “Flag” and “Slow coups”—each section rides an unfolding, an unfurling, ofaccumulations set as individual prose blocks, allowing the music of these lyricnarratives a kind of propulsion. As she offers as part of the first section: “Itbears repeating that Toni Morrison / said all water has a perfect memory/ and is forever trying to get back / to where it was. Writers arelike / that: remembering where we were, / what valley we ranthrough, what / the banks were like, the light that / was thereand the route back to / our original place.” She writes of history,slavery and arrival, and the ongoing impacts of that history, little of whichhas been properly acknowledged by the descendants of the perpetrators. “Certainfacts stand.” Or, further on: “Some of us can be traced by how we / arrived—whichway up or down. Some / of us don’t remember. Simply can’t.”

Movingfrom American border space through “Louisiana and Mississippi,” south to Guyanaand the “Meeting of Waters in Brazil,” Jackson’s text is lively, powerful and performative;bearing an incredible weight with a music and craft that provides such aquality of light. I would suspect such a collection equally comfortable on thestage as it is on the page, and an adaptation for the theatre wouldn’t beimpossible to imagine. Composed through an array of short narrative bursts thatstring and sing together to form something greater, Jackson’s FLAG articulatesa conversation around borders and depictions, notions of country andself-description, and how often that narrative contradicts, and so often at theexpense of the very populace they claim to protect. FLAG weaves avariety of histories, music and story, providing an incredible collage-effectof fierce intensity. This is a remarkable book.

Clear Rock’s recordingambles at a slow pace, slower than Leadbelly’s,

slower than the versionof it popularized by the late-1970s band Ram

Jam, whose rendition madethem a one hit wonder. Was it slow work

Clear Rock did on thechain gang—lifting the axe, swinging the axe,

felling the trees—despitethe rush of the whip. (“The Black Bettys”)

March 31, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Allyson Paty

Allyson Paty

[photo credit: Brittany Dennison] is the author of Jalousie (TupeloPress, 2025), winner of the 2023 Berkshire Prize, and several chapbooks, mostrecently Five O’clock on the Shore (above/ground press, 2019). Her poemsappear in publications including Denver Quarterly, Fence, Poetry,The Recluse, and The Yale Review, and her nonfiction can be foundin The Baffler. A 2017 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Poetry and aparticipant in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s 2017-2018 WorkspaceProgram, Allyson Paty is co-founding editor of Singing Saw Press. She works andteaches at NYU Gallatin and with NYU's Prison Education Program.

Allyson Paty

[photo credit: Brittany Dennison] is the author of Jalousie (TupeloPress, 2025), winner of the 2023 Berkshire Prize, and several chapbooks, mostrecently Five O’clock on the Shore (above/ground press, 2019). Her poemsappear in publications including Denver Quarterly, Fence, Poetry,The Recluse, and The Yale Review, and her nonfiction can be foundin The Baffler. A 2017 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Poetry and aparticipant in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s 2017-2018 WorkspaceProgram, Allyson Paty is co-founding editor of Singing Saw Press. She works andteaches at NYU Gallatin and with NYU's Prison Education Program.1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Jalousie is my firstbook, so I’ll have to report back! My first chapbook, The Further Away,was published by artist Jonathan Rajewski, when he was running a small presscalled [sic] out of his home in Detroit, in 2012. I was just starting to thinkof publication in terms beyond the creation of a book object, that a book isnot only its contents or even its material properties but a document that marks—andmakes—relationships to other people, to particular places, and moments in time.Going to Detroit for a reading when that chapbook came out and then giving away(and occasionally selling) copies of that chapbook over the next months andyears helped me to learn that.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Evenin grade school, I liked sentences more than plots. I liked arguments andideas, but I paid closer attention to the words that made them happen. When Iwas a senior in high school, a beloved teacher, the late Marty Sternsteinoffered a course in twentieth-century American poetry. He gave us this packetof maybe fifty poems to read over the summer. I found it a few years ago, andsurprised at the variety—Baraka, Eliot, Harjo, Jeffers, Niedecker…At seventeen,I knew nothing; these were meaningless names to me. But I loved my totallyuninformed encounters with the texts. Two poems in particular I read and rereadall summer: an excerpt from Spring and All (yes, the red wheelbarrowpart) and “Susie Asado.” I picked up Williams’s selected poems and Stein’s TenderButtons sometime that fall. The attention to language I’d felt I wassneaking around for in other kinds of literature was suddenly there in thefore.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

S-l-o-w.Slower than slow. So slow I sometimes don’t know it’s happening, or I worrythat it’s not. I write regularly in that I set down language, but most of thetime it’s not toward anything. Once in a while, I’ll start to see something inmy notes—usually a tension in logic or sound—that I recognize as part of theshape of a poem. Usually some part of that language stays through to the end.But the revision process continues for a long time. There’s often not even asingle version or document I can point to as a first full draft. And I scrap alot. The poems in Jalousie were written between 2011 and 2021. Apostcard featuring cartoon snails sits above my desk, but when I see livingsnails on the move, they look to me like they’re going pretty fast.

4- Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Depends.Jalousie is truly a collection but contains two long poems. Over theyears that I writing the poems in Jalousie, I wrote a differentmanuscript that is a single project. What I’m working on now began with theform and length of a book in mind.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Bothpart and counter, and I enjoy it. Sometimes, if I have a reading coming up, Itake it as a deadline where the stakes are social embarrassment. It helps me tocast the language I’ve been keeping so close out, toward others. But I admit,it’s happened before that the reading is drawing near, and I’ll cut parts of apoem I’d felt committed to if they’re not working yet, or even change them tosomething I think will land. The lure to write what you know you can alreadywrite well is a conservative one. It’s is a concern I have about the workshopmodel in most contexts. But without the chance to share with others at aparticular time and place, I’d burrow into the mess of my notes without end.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Ihave this idea that most artists—most people—have a few fundamental questionsto follow that become the arc of their creative work, their lives. They’re soclose to me, they’re hard to articulate. One, though, has to do with therelationships between the language and the real, especially in description. Iused to teach a creative writing course on writing and the visual, and it beganwith examining the mechanics of literary images—what relationships do they haveto sight, and what extra-visual elements come into play? How about to anyparticular referents? I’m not trying to answer that question so much as towrite alongside it.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

Definitelynot one. As in, I think different writers have different roles,differently perceptible. Sometimes that has to do with what a particular pieceof writing offers others, but sometimes it has to do with how one enters anysocial space (and I would argue that any social space has—or is—a culture). Forexample, at my job, I often track how language is being used (or withheld) innon-literary contexts, like in policy memos, or at meetings, say, and thatgives me a different—I’d say, fuller—picture of what’s happening than I wouldotherwise have.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Essential,and a gift.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My undergraduate adviser, choreographer and dancer Leslie Satin, had just watcheda dance in progress and was giving me notes about a part that didn’t work. Shesaid to “fix the mistake or make it more itself,” meaning, to work the mistakeinto the piece, to follow it.

10- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’min an extended moment of transition. For a long time, I wrote every day beforework, and at least one afternoon every weekend. I still like those times, butat a certain point, I needed more sleep and the rigidity of my routine wasproducing more guilt than writing. Lately, I’ve been writing in whatevermoments I can carve into the day, and I try to set aside a longer block of timea couple times a week.

11- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Toreading, usually something I haven’t read before. And I run.

12- What fragrance reminds you of home?

InNew York’s warmer months, after the sun goes down, the sidewalks give off aparticular scent that feels to me like home. It’s different than the New YorkCity summer garbage/urine stench, but I do associate that smell withexuberance, excess life, celebration, even though I don’t like it.

13- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Absolutely!Dance and the visual arts especially. There are some ekphrastic poems in Jalousie,and one poem is a performance score, it’s one in a series I was writing for afew years, eventually published as a chapbook called Score Poems (PresentTense Pamphlets, 2016).

14- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Toomany to name, from the canonized to the to small-press writers from othergenerations to my friends. But there are a handful of books I read in mymid-to-late twenties that spoke to me differently than others I’d read before:Simone White’s Of Being Dispersed, Lucy Ives’s Orange Roses,Sawako Nakayasu’s The Ants and Texture Notes, Mei-MeiBerssenbrugge’s Hello, the Roses. I felt a kind of proximity to theseworks—not that I felt my writing was comparable; I admired these bookstremendously and still do—but like they were opening the way into my ownconcerns. Although he’s not contemporary, I had a similar feeling in thoseyears when I was reading the collected poems of George Oppen.

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Whyis this question stumping me? Maybe because I’m so attracted to dailiness andharbor such distrust of goals.

16- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Myfull-time job is as a university administrator and writing teacher, so I dohave another occupation. But it’s one I came to in figuring out how to make alife and livelihood in writing, so maybe that’s not a good answer. I’d beinterested to work in sanitation, but I’d need more physical strength and a lotof practice to drive a vehicle as big as a garbage truck.

17- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Continuingin dance meant rehearsal space, money to rent it, and time to coordinate withothers; writing was so flexible and available by contrast.

18- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book:Bob Gluck’s About Ed. Film: Hong Sang-Soo’s A Traveler’s Needs.

19- What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a manuscript that is in someways a breakup story, and in some ways an extended work of ekphrasis. At theend of a long-term romantic relationship, as I navigated the impulse to parsewhat was happening, what had happened, etc., I found affinities with questionsthat have long interested me about narrative, representation, and figuration.Some of the artworks that come up in the book are Nam Jun Paik's 1962 Zenfor Head, the 15th century Noh play Ashikari (TheReed Cutter) by Zeami Motokiyo, three 18th century still-life paintings by AnnaMaria Punz.

March 30, 2025

MC Hyland, The Dead & The Living & The Bridge

In a museum in Oslo, wefound a whole room of cloud studies. The small painted clouds transferred thelight of another time and country directly into our faces. Though O’Harathought that the clouds get enough attention as it is, it seemed as though we hadnever properly perceived their indexical charms. (“Essay on Weather”)

I’mvery pleased to see a new title by St. Paul, Minnesota-based poet, editor and publisherMC Hyland—following

THE END

(Sidebrow Books, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Neveragainland

(Lowbrow Press, 2010) [see my review of such here], as well as a handful of chapbooks (including one through above/ground press)—their full-length

The Dead & The Living & TheBridge

(Chicago IL: Meekling Press, 2025). “My language possessed byadverbs of suddenness,” she writes as part of “Essay on Weather,” “of incrementalchange.” Through seventeen extended sequences, The Dead & The Living& The Bridge exists as a suite of prose poems within the nebulous spaceof short stories by Lydia Davis and the essay-poems of poets such as Anne Carson,Benjamin Niespodziany, Lisa Robertson and Phil Hall. “Against the onrush ofhistory,” the sequence “Essay on Weather” continues, “I sought the register ofclouds, of breezes, of minute shifts in actual or perceived temperature. Againstthe dying present, I accumulated a small log of instances.” Directly citingCanadian poet Anne Carson infamous Short Talks (Brick Books, 1992), theback cover offers: “In the tradition of Montaigne’s Essais and Anne Carson’sShort Talks, MC Hyland’s poem-essays weave together the conceptual andthe material, leaving a trace of thought-in-flight.”

I’mvery pleased to see a new title by St. Paul, Minnesota-based poet, editor and publisherMC Hyland—following

THE END

(Sidebrow Books, 2019) [see my review of such here] and

Neveragainland

(Lowbrow Press, 2010) [see my review of such here], as well as a handful of chapbooks (including one through above/ground press)—their full-length

The Dead & The Living & TheBridge

(Chicago IL: Meekling Press, 2025). “My language possessed byadverbs of suddenness,” she writes as part of “Essay on Weather,” “of incrementalchange.” Through seventeen extended sequences, The Dead & The Living& The Bridge exists as a suite of prose poems within the nebulous spaceof short stories by Lydia Davis and the essay-poems of poets such as Anne Carson,Benjamin Niespodziany, Lisa Robertson and Phil Hall. “Against the onrush ofhistory,” the sequence “Essay on Weather” continues, “I sought the register ofclouds, of breezes, of minute shifts in actual or perceived temperature. Againstthe dying present, I accumulated a small log of instances.” Directly citingCanadian poet Anne Carson infamous Short Talks (Brick Books, 1992), theback cover offers: “In the tradition of Montaigne’s Essais and Anne Carson’sShort Talks, MC Hyland’s poem-essays weave together the conceptual andthe material, leaving a trace of thought-in-flight.”Withtitles such as “Essay on Paper,” “Essay on Ophelia,” “Essay on Labor and theBody (Gender I),” “Five Short Essays on Open Secrets” and “Essay on theProse Poem,” the collection holds as a single, book-length unit, offeringechoes of structure and titles to contain an absolute array of multitudes. Throughspellbinding prose, Hyland offers sentences across vibrant thinking, attemptingto connect disparate thoughts and the chasms between, as she writes, the deadand the living. “In a poem addressed to either a lost lover or an unborn child,”the four-page, four-stanza poem “Essay on the Optimism of Attachment” ends, “I wroteI didn’t want to make you the referent of my theological longings. The spaceof either love or belief: a space of absence, of silence. A dazzling cloud intowhich I lean.” Hyland holds the form of the prose poem as complex as Carson’s suiteof talks, offering the prose lyric as capable of containing entire realms ofcomplex meditation, weaving multiple threads on reading, writing and experience,and even the limitations through which one attempts to examine through writing.“Which is to say: the experience of pain cannot be reliably witnessed,” Hylandwrites, in the third part of “Five Short Essays on Open Secrets,” “at least notthrough language.” As well, there’s a shared element of Carson’s, as well as evidentthrough Phil Hall, of the poem as a means through which to discuss, through akind of collage or weaving, the very act of attempting to understand how bestto live in and experience the world. I’ve long been an admirer of Hyland’swork, but if this is an example of where their work is going, I am very excitedto see what might come next. As Hyland writes as part of “Essay on Vocation”:

Lewis Hyde writes Whenwe are in the spirit of the gift we love to feel the body open outward. Perhapsthis is the narcotic condition produced by certain of the windowless rooms. Thebody blooms into one set of relationships, while at the same time the person isfixed by larger systems into a position of contingency and debt. To step away,as I stepped unwillingly away from my old love, is both heartbreak andsurvival.